ABSTRACT

Introduction: Appropriately managing mental disorders is a growing priority across countries in view of the impact on morbidity and mortality. This includes patients with bipolar disorders (BD). Management of BD is a concern as this is a complex disease with often misdiagnosis, which is a major issue in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs) with typically a limited number of trained personnel and resources. This needs to be addressed.

Areas covered: Medicines are the cornerstone of managing patients with Bipolar II across countries including LMICs. The choice of medicines, especially antipsychotics, is important in LMICs with high rates of diabetes and HIV. However, care is currently compromised in LMICs by issues such as the stigma, cultural beliefs, a limited number of trained professionals and high patient co-payments.

Expert opinion: Encouragingly, some LMICs have introduced guidelines for patients with BD; however, this is very variable. Strategies for the future include addressing the lack of national guidelines for patients with BD, improving resources for mental disorders including personnel, improving medicine availability and patients’ rights, and monitoring prescribing against agreed guidelines. A number of strategies have been identified to improve the treatment of patients with Bipolar II in LMICs, and will be followed up.

1. Introduction

1.1. General

The treatment of mental disorders is an increasing priority worldwide as these disorders currently account for between 10% and 13% of the global disease burden and they are also a leading cause of years lived with disability [Citation1–Citation6]. In addition, currently over 800,000 people die annually globally from suicide, which is a leading cause of death in people aged between 15 and 34 years [Citation7]. The global burden of these disorders has risen in recent years, especially among lower and middle-income countries (LMICs), as a result of demographic, environmental, unrest and socio-political changes [Citation8–Citation10]. For instance, there has been an appreciable increase in the burden of mental disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region in recent years with increasing levels of instability as well as stigma associated with mental health [Citation10–Citation12]. In Ethiopia, mental illness is now the leading non-communicable disease (NCD) in terms of its overall burden [Citation13], and in Lebanon, approximately one-quarter of the population have had at least one mental disorder with 10.5% of the population experiencing more than one disorder at some stage [Citation14]. In Nigeria, up to 20–30% of population suffer from mental disorders [Citation15,Citation16], and in South Africa, the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder is 30.3% [Citation17]. High rates of mental health disorders are also seen in Morocco [Citation18]. This burden will continue rising unless adequately addressed, increasing the urgency to identify and appropriately manage patients with mental disorders. However, there are challenges as there is currently limited government spending on mental disorders in LMICs including Africa [Citation19,Citation20]. For instance among African countries, spending on mental disorders has been less than 1% of total health-related expenditures in recent years [Citation19]. Currently, only US$0.1 per capita is being spent on mental health services by governments in the African region versus an average of US$21.7 among European countries [Citation20]. Overall, the median expenditure per capita being spent by governments on patients with mental health disorders in 2016 was only US$0.02 in low-income countries, rising to US$1.05 in lower middle-income countries and US$2.62 in higher middle-income countries [Citation20]. This though compares with US$80.24 in higher-income countries [Citation20]. In view of the lack of spending on mental health services, it is perhaps not surprising that in low-income countries there are less than 2 mental health workers per 100,000 population [Citation21], averaging just 0.9 among African countries [Citation20]. In Zimbabwe as a low-income country, just 12 psychiatrists treat a population of 14 million [Citation22]. In Ghana despite being a higher-income country than Zimbabwe, there is still a considerable gap between the number of patients with mental health disorders and available facilities to treat them [Citation23], with fewer than 20 psychiatrists throughout Ghana [Citation23,Citation24]. There are only approximately 200 psychiatrists in Nigeria serving a population of 170 million, with only 10% of the population with common but serious mental disorders receiving minimally adequate treatment [Citation25]. In Tunisia, there are currently only 3.7 mental health nurses per 100,000 of the population and 2.9 psychosocial care providers [Citation26]; however, there are ongoing initiatives to improve mental health provision among nonspecialists including primary health-care physicians to help address current deficiencies in care provision [Citation11]. Even in South Africa, only approximately 1 in 4 patients with mental disorders receive some form of treatment [Citation27]. Overall, it is estimated that more than 45% of the world’s population live in countries with less than one psychiatrist for 100,000 patients [Citation28], and more than 75% of people live in LMICs where there is limited or no access to mental health services [Citation3]. A limited number of psychiatric beds per capita among LMICs places further strain on the appropriate management of patients with mental disorders in these countries [Citation29,Citation30]. Access to effective interventions including medicines is also a concern in a number of LMICs. Patient co-payments for medicines can also be high with potentially catastrophic consequences for families if family members become ill [Citation31,Citation32]. Drug shortages can also affect treatment approaches [Citation23,Citation33,Citation34]. In addition, currently only a minority of people affected by mental disorders in LMICs receive even basic treatment worsened, as mentioned, by a lack of trained professionals to support these patients [Citation3–Citation5,Citation19,Citation35,Citation36]. As a result, there can be an over-reliance on pharmacotherapy to treat mental disorders where these are available [Citation33].

A lack of training of health-care professionals in a number of LMICs, the stigma associated with mental disorders exacerbated by preconceptions and cultural issues as well as a lack of clear referral systems and support to treat mental disorders, all negatively impact on care provision alongside concerns with access to care and appropriate treatment [Citation3,Citation4,Citation12,Citation16,Citation23,Citation37–Citation49]. There is also considerable use of traditional medicines and faith healers in a number of LMICs which may also have a negative impact on patient outcomes; however, this may not always be the case [Citation50–Citation52]. With respect to stigma, in Botswana patients with mental disorders can often be seen as untrustworthy and cognitively impaired; consequently, they can be discriminated against in their working environment [Citation53]. Domestic violence and issues of stigma are also reported among patients with mental disorders in Pakistan [Citation54] and in Tunisia, there is also still a considerable social stigma associated with severe mental illness; however, less for patients with bipolar disorders than schizophrenia [Citation12]. These barriers and threats to appropriate diagnosis and management of mental disorders need to be addressed to improve future care in LMICS [Citation8]. Adequately addressing human rights' issues in patients with mental disorders could also help in the longer term to improve the care of patients with mental health disorders [Citation7,Citation8], with ongoing activities among LMICs to address this [Citation20,Citation55–Citation58].

Consequently, multiple issues including available infrastructure as well as beliefs are currently appreciable barriers to the majority of patients with mental disorders receiving adequate care in LMICs, enhancing the chronicity of their poor mental health as well as increasing their suffering and costs [Citation2]. Progress is now being made to address a number of these issues through the WHO mGAP project [Citation23,Citation59,Citation60]. This builds on the 2009 WHO AIMS (World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems) report for LMICs [Citation35] to improve access to and the appropriate use of medicines. In addition, helping to scale up mental health services using a wide range of different professionals. The WHO also introduced the QualityRights initiative in 2013 to improve the care of patients with mental health disorders [Citation57,Citation58,Citation61,Citation62], with studies in sites such as Gujarat in India showing that the QualityRights programme can be effectively implemented in resource-limited setting to improve the quality of mental health services [Citation61]. We are also aware of the Partnership for Mental Health Development in Africa (PaM-D) to bring together diverse stakeholders to help create an infrastructure to develop mental health research capacity and science. This will be achieved through conducting innovative public health-relevant research and seeking to link research to policy development [Citation63]. In addition, the PRogramme for Improving Mental health carE (PRIME) project, which looks at the feasibility of task-sharing mental health care in LMICs to further improve the care of these patients [Citation36], as well as partnership networks in low resource settings via nonprofit organizations to improve the care of patients with mental illness [Citation64]. However, there is still room for considerable improvement among LMICs [Citation24,Citation41,Citation63,Citation65].

1.2. Bipolar disorders (BD) including prevalence and burden of illness

BD is not just one disorder but several, with the age at onset typically being late adolescence into young adulthood [Citation66–Citation71]. BP-I (Bipolar I) is characterized by episodes of mania. According to DSM-5, BP-I represents a classic manic depressive disorder although neither a depressive episode nor psychosis needs to be present for diagnosis [Citation72]. However, there is ongoing controversy whether unipolar mania should be a seperate diagnosis from BD-I [Citation73]. BP-II (Bipolar II) is characterized by less severe manic symptoms, classified as hypomania, however combined with depressive episodes [Citation69,Citation70,Citation74]. Affected people often experience prolonged episodes of depression followed by periodic hypomanic episodes [Citation69,Citation75]. However, there is an ongoing debate about the definition of hypomania [Citation70] and concerns whether different rating scales for diagnosing (hypo)mania are interchangeable [Citation76]. In practice, it can be difficult to differentiate between different BD disorders and other similar conditions, exacerbated by the presence of mixed states of BD, including depressive symptoms coexisting with manic symptoms [Citation70,Citation74,Citation77–Citation81]. BD patients are typically sensitive to depressive symptoms but may not recognize their hypomanic or manic symptoms [Citation69].

The prevalence of BD has increased appreciably in recent years, with a 49.1% increase between 1990 and 2013 [Citation81–Citation83]. However, this may well be due to a greater diagnosis of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders rather than appreciably increased prevalence rates. Having said this, increasing urbanization seen in recent years also appears to increase the prevalence of psychiatric disorders including BD [Citation84–Citation87]. This is a concern with a positive relationship seen between increasing urbanization and increasing number of suicides [Citation88]. Prevalence rates for BD vary across countries with an estimated prevalence of more than 1% of the world’s population [Citation69,Citation89,Citation90] up to 5% [Citation69,Citation83,Citation91–Citation96]. In their recent review, Clemente et al. (2015) estimated that the pooled 1-year prevalence of BP-I was 0.71% (95%CI 0.56–0.86) principally among higher-income countries and 0.50% (95%CI 0.35–0.64) for BP-II [Citation83]. Among LMICs in the study by Merikangas et al. (2011), India had the lowest prevalence of BP-I (0.1%0 and BP-II (0.1%) [Citation95]. There were also low rates in Lebanon (BP-I 0.4%, BP-II 0.5%) and Romania (BP-I 0.1%, BP-II 0.3%), but higher rates seen in Brazil (BP-I 0.9%, BP-II 0.2%), Colombia (BP-I 0.7%, BP-II 0.4%) and Mexico (BP-I 0.7%, BP-II 0.1) [Citation95]. Among LMICs in Africa, in Ethiopia and Nigeria community surveys have suggested a lifetime prevalence of BD at 0.1% to 1.83% [Citation97], although these could be underestimates [Citation98]. In South Africa, an estimated 3–4% of the population have BD [Citation99]. Underestimates for the prevalence of BD persist in LMICs as this is often misdiagnosed among patients with recurrent depression, which has resulted in calls for these patients to be screened more effectively, especially to try and detect BP-II [Citation100]. In addition, late-onset BD also appears underestimated arising from for instance misleading presentations and therapeutic difficulties due to a high prevalence of somatic comorbidities in these patients as seen in Tunisia and other countries [Citation101].

BD is seen as one of the most disabling conditions worldwide [Citation96], with a global burden of 9.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2013 [Citation82]. BD is a greater burden to health-care systems than, for instance, cancer, epilepsy, and Alzheimer’s disease combined [Citation66], with a 40.9% increase in DALYs attributable to BD between 1990 and 2010 [Citation70] and 49.1% between 1990 and 2013 [Citation82]. However, BD does not have the same emotive issues as seen with patients with cancer or orphan diseases [Citation102–Citation105]. Consequently, the appropriate management of patients with BD has not typically received the same level of attention among policymakers.

The direct medical costs associated with BD can be high because of the appreciable use of medical services [Citation66,Citation67,Citation106], often exacerbated by misdiagnosis and frequent psychiatric comorbidities [Citation107]. However, there are few published studies on the costs of BD in LMICs although we are aware that there have been reviews examining the economic burden of caregiving for persons with severe mental illness in sub-Saharan Africa [Citation97,Citation108,Citation109]. The cost of medicines will be a key cost component in LMICs in line with other disease areas [Citation31]. Indirect costs for patients with BD can also be high due to its impact on patients and their families, their employers and society as a whole [Citation66,Citation70].

The effective management of BD is critical because BD is a serious often disabling condition that can be fatal [Citation68]. Extra care is also needed during occasions such as Ramadan, which was associated with higher rates of relapses among patients with BD in Morocco [Citation110]. The risk of suicide is high during the depressive episodes of BD [Citation71], with approximately 17% of patients with BP-I and 24% of patients with BP-II or higher are likely to attempt suicide during the course of their illness [Citation69,Citation70,Citation111]. This is important given an increasing rate of suicides in LMICs in recent years, with 79% of global suicides now occurring in LMICs [Citation6,Citation112,Citation113]. Between 15% and 20% attempts prove fatal [Citation114]. As a result, BD may account for a quarter of all completed suicides [Citation115]. In addition, patients with severe mental disorders have two to three times higher average mortality compared with the general population, which reduces life expectancy by 10–20 years [Citation9]. A considerable proportion of BD patients, even in clinical remission, also live with significant functional impairment as seen by high DALY rates [Citation82,Citation96,Citation116–Citation118], with often poor quality of life among patients with BD [Citation92,Citation119].

In view of this, there is an urgent need across countries to identify and effectively treat patients with BD in order to reduce morbidity and mortality rates [Citation90]. During the initial stages of BD, patient’s symptoms can be confusing and challenging to diagnose due to heterogeneous clinical presentations [Citation96]. It can be difficult to distinguish mania from other psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia. The psychosis episodes may be acute and transient, which makes misdiagnosis of BD patients common [Citation90,Citation97,Citation111]. There are also concerns about confusion of patients with BP-II with unipolar depression among health-care professionals, with an estimated 35–45% of BD patients initially misdiagnosed with unipolar depression [Citation81,Citation90,Citation96,Citation115]. As a result, delays of several years can occur between an initial diagnosis of a mental disorder and a diagnosis of BD [Citation96]. BD patients can also experience intense, rapidly shifting emotional states [Citation120], with BD patients experiencing a greater number of mood swings than others impacting on their functioning [Citation121]. Co-morbidity with other psychiatric disorders is also common making treatment complex [Citation69].

Consequently, the principal objective of this paper is to review current treatment recommendations for patients with BP-II. Subsequently, discuss potential issues and challenges among LMICs in managing patients with BP-II in view of the concerns that have been raised. These include issues with limited available services and trained personnel making differential diagnosis and appropriate management challenging [Citation90,Citation96,Citation122,Citation123]. Finally, we will discuss possible ways forward to improve the management of patients with BP-II in LMICs building on the considerable experiences of the coauthors. As a result, we will hopefully provide guidance for all key stakeholder groups on potential ways to improve the future management of patients with BD in LMICs. We are unaware of any published studies that have focused exclusively on current challenges in the management of BP-II among LMICs, which is of critical importance given the many challenges that exist in these countries.

2. Methodology

A number of reviews and guidelines have been published in this area, including burden of illness studies and studies of attitudes toward antipsychotic treatment [Citation43,Citation66–Citation69,Citation78,Citation82,Citation90,Citation96,Citation97,Citation107,Citation124–Citation126]. Consequently, we did not undertake a formal systematic review. We have based this overview and suggested activities on pertinent publications known to the coauthors as well as their extensive experiences across countries as there are only a limited number of publications on BD and its management in LMICs, with most publications including guidelines coming from high-income countries. This is a concern given the considerable challenges that patients with BD face in LMICs with access to appropriate care including medicines. The coauthors have considerable knowledge of activities in their own countries to try and address current challenges and we have used this information to contextualize potential ways forward. This builds on current activities by the WHO and others. The countries specifically chosen to provide additional insight into current challenges and potential ways forward in LMICs reflect a range of continents, incomes, diversities, and support systems. These are principally lower- and upper-middle-income countries since the challenges experienced in these countries will be enhanced in low-income countries. However, this is not always the case, e.g. Ethiopia, which is a low-income country, has developed a comprehensive strategy in recent years to improve the care of patients with mental health disorders in line with the WHO mGAP initiative [Citation13,Citation127]. We are also aware that for instance, it is currently easier to monitor lithium levels in patients with BD in Kenya, which is a low middle-income country compared with Botswana, which is an upper-middle-income country.

We have used such approaches before to stimulate debate in priority disease areas to provide future guidance [Citation128–Citation137]. The 2018 World Bank classification has been used to categorize countries into LMICs or upper-income countries [Citation138] wherever pertinent.

3. Current management and challenges with treating patients with BD especially BP-II

We will first discuss current management approaches for patients with BD including current controversies, which are typically based on publications involving high-income countries given the paucity of publications from LMICs, before specifically discussing the situation in LMICs. Finally, we will debate current challenges and the ways forward (under Expert Opinion) to provide future guidance for LMICs seeking to improve their care of patients with BD.

3.1. Current management approaches for patients with BD especially BD-II

The management of BD, especially BP-II, includes both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in the acute phases of mania (or hypomania), in depressive episodes, as well as for long-term therapy to prevent recurrences [Citation69–Citation71,Citation125,Citation139]. Given the difficulties, several screening instruments have been developed to aid diagnosis; however, concerns have been raised with their sensitivity, especially in community settings [Citation69,Citation140]. Typically, detailed questioning of patients is needed to enhance the diagnosis of BD and in particular the different types [Citation67,Citation69].

Pharmacological interventions are seen as the cornerstone for managing acute mania or for those who suffer a manic episode while on long-term treatment [Citation70,Citation90,Citation125,Citation139]. Lithium was the first treatment used for the management of acute mania [Citation69,Citation96,Citation141,Citation142]. Because of the side-effects and the risk of mania after acute withdrawal associated with lithium, other therapies have since been approved and prescribed including carbamazepine, valproate, and lamotrigine [Citation67,Citation69–Citation71,Citation141,Citation143]. Valproate has largely replaced lithium in a number of countries due to concerns with adequately monitoring blood levels [Citation67,Citation70,Citation143] although lithium is still prescribed and included in clinical practice guidelines where possible as it has greater anti-suicidal and other effects compared with other mood stabilizers [Citation90,Citation125,Citation142,Citation143]. Similar treatments are used for hypomania [Citation69]. Typically, mood stabilizers such as lithium and valproate can be combined with an antipsychotic such as quetiapine, aripiprazole, risperidone or olanzapine as a more effective treatment of mania, especially for patients with more severe mania [Citation67,Citation69,Citation71,Citation81,Citation96,Citation144].

The choice of antipsychotic is particularly important in sub-Saharan Africa. This region has high and growing rates of obesity and diabetes. For instance in Nigeria, 62% and 49% of adults are currently overweight or obese, respectively, [Citation145] and over 50% of the population in South Africa is currently overweight or obese [Citation146]. In Botswana, 6% of adults currently have diabetes with prevalence rates rising with increasing rates of obesity [Citation147], with similar rates seen in Namibia [Citation148]. Overall, the prevalence of diabetes is growing across Africa, with an estimated 16 million adults currently having diabetes [Citation149]. This is likely to grow to 41 million by 2045 with increasing urbanization and changing lifestyles [Citation150–Citation152]. Consequently, any treatment prescribed to overweight or diabetic patients with BD must include lifestyle changes tailored to the specific population [Citation9]. In addition, prescribers must be cognizant of the weight gain potential with antipsychotic medicines such as olanzapine versus for instance risperidone and quetiapine (moderate weight gain potential) and aripiprazole (low weight gain potential) [Citation153]. Co-morbidities are a particular issue in patients with BD as adherence to therapies is already a concern [Citation125,Citation139]. This will be a particular issue in patients with both mental disorders and HIV necessitating additional psychosocial support [Citation9,Citation53,Citation154,Citation155], with high rates of HIV seen in sub-Saharan Africa [Citation154]. There are also concerns that some treatments for HIV may also result in mental disorders warranting greater care [Citation155] with these patients again needing to be carefully managed. This is unlike the situation in high-income countries.

Acute bipolar depressive episodes are usually managed in ambulatory care unless there is an imminent risk of suicide [Citation67]. Typically, antipsychotics such as quetiapine are used to treat bipolar depression.

However, to date, there are only a limited number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antipsychotics for bipolar depression. These include lurasidone, olanzapine (combined with fluoxetine) and quetiapine [Citation69,Citation71,Citation90,Citation125], although cariprazine has recently been approved by the FDA for BD depression [Citation156]. Generally, lower starting doses and slower titration are needed when treating depression compared with mania because patients with depression are more sensitive and less tolerant to treatment [Citation69]. Given the limited number of approved medicines, off-label use of olanzapine monotherapy or in combination with lithium is common [Citation69]. There is currently controversy surrounding the prescribing of anticonvulsants for depressive episodes as well as the prescribing of antidepressants during acute bipolar depression and maintenance [Citation69,Citation71,Citation81,Citation96]. However, others have suggested that lamotrigine can be prescribed as first-line treatment for bipolar depression [Citation71]. The risks of using antidepressants include increased mood cycling and possibly rapid cycling [Citation67,Citation115,Citation157,Citation158]. This is a concern given the perceived overuse of antidepressants among BD patients in LMICs [Citation96]. However, co-prescribing an antidepressant with an antimanic medication such as lithium, valproate, or quetiapine, may reduce the risk of switching to mania or hypomania [Citation67,Citation125]. In addition, there may be less cycling with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) than other antidepressants [Citation70]. Electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) has also been shown to be effective in BP-II patients with resistant depression [Citation69,Citation90,Citation125].

With typically 50% cases of recurring within 12 months, preventative strategies are usually prescribed to reduce these following acute episodes [Citation69,Citation70,Citation96]. In BP-II patients, though controversial, this typically includes a mood stabilizer such as lithium or valproate combined with an antipsychotic such as quetiapine or possibly an antidepressant [Citation67,Citation69,Citation96]. However, antidepressants should be avoided in patients with poor outcomes to such treatments or in patients with recurrent mixed symptoms [Citation67,Citation157,Citation159]. Generally, patient attitudes toward antipsychotics for maintenance are positive, which is encouraging [Citation126].

In addition, ideally, maintenance treatment should be aligned with the type of BD, which includes addressing predominantly depressive symptoms in patients with BP-II [Citation69]. For instance, a patient with BP-II may have a better response to an anticonvulsant such as lamotrigine as well as potentially olanzapine or quetiapine, and are more likely to be co-prescribed an antidepressant [Citation67,Citation69,Citation125,Citation160]. Approaches to improve current poor medication adherence rates include potential electronic monitoring of patients [Citation161]. This is important since, in their recent review, Jaracz et al. found in Poland that 61% of BD patients were prescribed two medicines, including mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and lamotrigine, with 22% prescribed three or more medicines [Citation162]. The most common combination was a mood stabilizer with an atypical antipsychotic (48%). Greater polypharmacy was seen in BP-I versus BP-II patients [Citation162], with polypharmacy known to affect adherence rates in practice [Citation163–Citation165].

Medication assessment tools are also being developed to appraise prescribers’ adherence to evidence-based guidelines for BD, with such approaches likely to improve care across countries [Citation166]. Adherence to guidelines has been seen as a better indicator of the quality of prescribing in ambulatory care compared with current WHO/INRUD metrics, including the number of medicines prescribed [Citation167].

3.2. Current management of BD across LMICs

As mentioned, there is generally a paucity of papers describing prevalence rates and management of patients with BD in LMICs.

A recent paper by Samalin et al. reviewing the management of BD in six LMICs documented a higher prevalence of BD-I (72.2%) than BD-II (25.7%) [Citation96]. Overall, 67.2% of BD patients were prescribed antipsychotics at initial diagnosis, with 51.1% prescribed first-generation antipsychotics and 51.6% second-generation antipsychotics. There were concerns with the overuse of antidepressants with 44.4% of patients prescribed an antidepressant at initial diagnosis, principally SSRIs (67.2%), with 29.7% prescribed mood stabilizers at initial diagnosis [Citation96]. This changed for long-term maintenance with 87.5% receiving mood stabilizers, mainly anticonvulsants (84.3%) and antipsychotics (83.4%), which were mainly second-generation (79.6%) – more in BP-II than BP-I patients (91.8% vs. 75.9%, respectively). Overall, 36.1% of patients were prescribed antidepressants, mainly SSRIs, principally in BP-II versus BP-I patients (58.1% vs. 27.8%) [Citation96]. The time from initial diagnosis of a mental health disorder to diagnosis of BP-II was a median of 2.2 years [Citation96].

depicts the current management of BD across a wide range of LMICs with special emphasis on BP-II acknowledging concerns with the current paucity of data as well as current controversies [Citation168]. emphasizes that the management of BD is variable across LMICs; however, pharmacotherapy is seen as the cornerstone of care in all documented countries. In addition, some LMICs have introduced standard treatment guidelines for patients with BD whilst others have not.

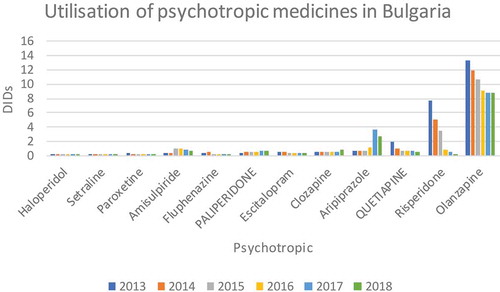

Figure 1. Utilization of psychotropic medicines in Bulgaria in recent years (source: (https://www.nhif.bg/page/218)).

NB: DID = DDDs/1000 inhabitants/day.

Table 1. Current treatment approaches to the management of patients with BD, especially BD-II among LMICs.

3.3. Challenges to the appropriate management of patients with BD-II especially in LMICs

There are several important challenges to the appropriate management of patients with BD-II in LMICs. These include concerns with an accurate diagnosis as well as the availability of trained professionals and appropriate pharmacotherapies. and Box 1 discuss a number of these issues among selected target LMICs before discussing potential ways forward (Section 5).

Table 2. Key challenges facing LMICs in the management of patients with BD-II especially lower middle-income countries.

There are a number of common challenges to the management of patients with BD-II in LMICs building on comments in the Introduction and . In addition to concerns with stigma, common challenges include the use of traditional medicines and faith healers as well as cultural issues associated with the management of patients with mental disorders [Citation16,Citation40,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49]. Common challenges and themes can be divided into infrastructure and financial issues as well as treatment issues (Box 1). These will be explored further along with other key issues in Expert Opinion (Section 5).

At the very least, LMICs need to ensure the following medicines need to be made routinely available for patients with BP-II in line with the 2019 WHO Essential Medicine List [Citation227]:

carbamazepine Tablet (scored): 100 mg; 200 mg.

lithium carbonate – solid oral dosage form: 300 mg.

valproic acid (sodium valproate) Tablet (enteric-coated): 200 mg; 500 mg (sodium valproate).

Valproic acid (or potentially carbamazepine) is particularly important where there are lack of facilities to monitor lithium blood levels. In addition, second-generation anti-psychotics such as aripiprazole and quetiapine are becoming cheaper to help address issues of weight gain.

4. Conclusion

There are a range of activities and actions that LMICs might consider in the future to address existing barriers and challenges to the management of patients with BP-II. These include improving access to services and treatment including medicines, with potentially mobile clinics and improved training helping [Citation11,Citation228]. Addressing these challenges represents a unique opportunity to address the broader issue of increasing access to treatments and care for patients with mental disorders generally. This includes addressing the current lack of attention to mental disorders, which remains a central barrier to care not only in LMICs but also in several high-income countries.

The Gulbenkian Mental Health Platform, an initiative of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, identified a number of simple, evidence-based actions that policy-makers, public health professionals and prescribers, especially in LMICs, should undertake to improve access to, and appropriate use of, medicines for mental disorders including BD. They include: (Citation1) developing an evidence-based medicine selection process; (Citation2) promoting information and education activities for health-care professionals and users on the selection process; (Citation3) regulating psychotropic medicine availability; (Citation4) implementing a reliable health and supply chain system; (Citation5) ensuring the quality of psychotropic medicines including generics; (Citation6) developing a community-based system of mental health care; (Citation7) developing policies on the affordability of medicines; (Citation8) developing pricing policies and fostering a sustainable financing system; (Citation9) adopting evidence-based guidelines; (Citation10) monitoring the use of psychotropic medicines; and (Citation11) promoting training initiatives for health-care professionals on the critical appraisal of scientific evidence and appropriate use of psychotropic medicines. This is in addition to adequately addressing human rights' issues in patients with mental disorders where these currently exist in LMICs including implementing the QualityRights program building on current successes [Citation61].

In conclusion, LMICs should be encouraged to address mental disorders in the context of their overall health needs and national programs. Appropriate access to psychotropic medicines offers the chance of transformative improvement in health along with other measures as well as the opportunity for re-engagement in society for people with mental illnesses. By working at all levels of the health system, it may be possible to offer this essential component of mental health care to all who can benefit, building on current examples in LMICs.

5. Expert opinion

Potential strategies to overcome barriers and existing problems to the management of BP-II in LMICs start with recognition of the limited resources currently being spent on mental disorders in a number of these countries compared with current spending on infectious diseases and other NCDs. In addition, recognizing the human rights of patients with mental disorders and addressing issues with the stigma that patients with mental health disorders currently experience [Citation8,Citation35,Citation61]. The lack of focus on mental disorders in some LMICs may be because of an increasing focus on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in recent years due to high inappropriate use of antibiotics and its associated consequences on morbidity, mortality, and costs [Citation229–Citation236]. HIV/AIDs and its management have also been a particular focus, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, diverting attention away from mental disorders. In addition, there has also been an increasing focus on other NCDs such as hypertension and diabetes in recent years [Citation150,Citation237–Citation240], again diverting attention and resources away from mental health disorders.

However, we are now seeing LMICs develop or start to develop national action plans and prescribing guidance to improve the health of their patients with mental disorders in their country, building on the WHO mhGAP initiative, the QualityRights initiative as well as the PaM-D initiative in sub-Saharan Africa ( and ) [Citation59,Citation61–Citation63,Citation241,Citation242]. This will continue as more knowledge about the burden of mental disorders is developed and discussed. Such activities are essential to raise the profile of mental health including those patients with BP-II as well as discussions about the appropriate management within countries, building on the success of the WHO in raising the profile of AMR and NCDs such as hypertension and diabetes. In addition, counteracting the activities of pharmaceutical companies and others raising the focus on for instance cancer, which is reflected by governments in high-income countries paying very high prices for new cancer medicines with often limited health gain resulting in reduced funding for other disease areas [Citation102,Citation104,Citation243,Citation244].

Other activities to address current challenges can be further divided into infrastructure and/or funding issues as well as management issues building on .

Box 1. Common challenges in the management of BD-II among LMICs

5.1. Infrastructure/funding issues

We are already seeing in countries such as Zambia () that resources are now being spent to train more health-care professionals and deploy them in the community to improve the availability of trained personnel in ambulatory care. There have also been considerable activities in countries such as Ethiopia and Tunisia to improve the care of patients with mental health disorders ( and ). Consequently, this should improve diagnosis and subsequent management of patients with mental disorders including those with BP-II, and can serve as exemplars to other countries. Hopefully, the situation will also change in South Africa providing guidance to others to improve care in the community ( and ).

The lack of training of health-care professionals, especially in ambulatory care, can be addressed through opportunities for continual professional development in universities, building on the experiences in Tunisia and Zambia. However, such activities need to be attractive for professionals or else available courses may become redundant through lack of interest (). This would not be in the best interest of any key stakeholder group including patients with BD-II.

There also needs to be urgent discussions in LMICs to seek ways to retain trained health-care professionals rather than having them leave for higher-income countries to boost their wages once trained. Increases in the number of psychiatric beds as well as provision of community facilities devoted to mental health are also needed. These can be part of ongoing national action plans surrounding mental health.

5.2. Management issues

Management issues can be divided into educational issues, including local guideline development, as well as addressing medicine availability and co-payment issues alongside improving the infrastructure for identifying and treating patients with BP-II.

One of the first activities within countries is to produce nationally agreed guidelines to improve the management of patients with BP-II including differential diagnosis. This is important especially with most guidance and practices in the management of BD based on the USA. This can build on existing activities within countries such as India, Namibia, Nigeria and South Africa ( and ) as well as guidance from the WHO and others. Once developed, the guidance and the philosophy behind it can be included in the educational curriculums of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists as well as form part of any continual professional development program.

Developing national context-specific STGs is also seen as important to improve the management of patients with BD, especially those with BP-II, within countries given current controversies surrounding the use of antidepressants in these patients and potential confusion of BP-II with unipolar depression. National guidelines can be based on international, regional or other national guidelines from LMICs and subsequently adapted to the local situation. It is critical that key government as well as physician and pharmacist stakeholders within a country are involved in their development and/or refinement to enhance adherence to any guidelines produced. The local context is particularly important in LMICs with their often high prevalence rates of HIV as well as cardiovascular diseases including diabetes compared with developed countries where international guidelines are typically produced. We have seen there is greater adherence to guidelines in ambulatory care if health-care professionals know and trust those developing the guidelines [Citation245–Citation247]. As mentioned, consideration of local multiple co-morbidities is important in LMICs when developing and recommending treatment approaches as well as in addressing key issues surrounding adherence.

Concerns with adherence to prescribed medicines are also a growing issue when managing patients with BD, including BP-II in LMICs. Educational and other strategies are needed to improve rates. Such activities can build on ongoing research among LMICs, including sub-Saharan African countries, on ways to improve adherence to medicines in patients with other NCDs [Citation240,Citation248–Citation251].

Once national STGs have been produced, prescribing in both ambulatory care and among hospitalized patients should be monitored to improve subsequent care. This recommendation is based on the findings in India and Zambia following their audits versus Pakistan ().

The unpredictable availability of medicines to treat patients with BP-II can be improved through improved supply chain management as seen by recent initiatives in South Africa [Citation252]. Issues of high co-payments where these exist can potentially be addressed by encouraging greater use of generic medicines where available, although there can be issues of quality, as well as seeking access schemes or donors where possible building on the experiences in Kenya [Citation240,Citation253–Citation256]. The long-term goal is universal access to healthcare, building on recent examples in Southern Africa [Citation252].

Finally, governments and others should seek to introduce educational campaigns among patients, including those with BD, to dispel current myths surrounding mental disorders and its management. These can build on programs instigated in countries to reduce patient pressures on physicians and pharmacists to prescribe and dispense antibiotics for essentially viral and self-limiting infections [Citation257,Citation258].

Article Highlights

There are challenges to appropriately manage patients with mental disorders in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to limited government spending and a limited number of trained personnel compared with high-income countries.

The prevalence of bipolar disease (BD) has increased appreciably in recent years and is now one of the most disabling diseases worldwide.

The management of BD disease is challenging as it can be difficult to differentiate between the different BD states and between unipolar depresssion and Bipolar II (BP-II), and there can be appreciable delays in diagnosis especially in LMICs.

The management of BP-II includes both pharmacological (lithium, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and antidepressants) and non-pharmacological approaches; however, there is currently variable availability of standard treatment guidelines in LMICs to guide patient care and the prescribing of lithium will depend on available monitoring facilities.

The choice of antipsychotic is particularly important in sub-Saharan Africa with high rates of overweight, obesity and Type 2 diabetes, with care also needed in patients with HIV and BD as some treatments for HIV can increase mental disorders.

This box summarizes key points contained in the article.

Declaration of interest

Marianne Van-De-Lisle is employed by NHS Lothian, Ruaraidh Hill advises the UK National Health Service while Amos Massele and Philip Opondo advise the Botswanan Ministry of Health. Israel Sefah is employed by the Ghana Health Service while Kristina Garuoliene is employed by the Lithuanian Ministry of Health. Additionally, Tanveer Ahmed Khan and Shahzad Hussain are employed by the National Institute of Health, Pakistan while James Mwanza advises the Zambian Ministry of Health. Furthermore, Corrado Barbui is an advisor to the World Health Organization. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–178.

- Patel V. Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2007;81-82:81–96.

- WHO. World Health Organization, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Improving access to and appropriate use of medicines for mental disorders. Geneva. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254794/1/9789241511421-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Bruckner TA, Scheffler RM, Shen G, et al. The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(3):184–194.

- Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(2):119–124.

- Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, et al. Global priorities for addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. In: Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, et al., editors. Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: disease control priorities. 3rd ed. Vol. 4. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank (c) 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2016;1–28.

- WHO quality rights: service standards and quality in mental health care. [cited 2019 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/quality_rights/infosheet_hrs_day.pdf?ua=1

- Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553–1598.

- WHO. Management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275718/9789241550383-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Charara R, Forouzanfar M, Naghavi M, et al. the burden of mental disorders in the eastern mediterranean region, 1990–2013. PloS One. 2017;12(1):e0169575.

- Spagnolo J, Champagne C, Leduc N, et al. A program to further integrate mental health into primary care: lessons learned from a pilot trial in Tunisia. Jn Global Health Reports. 2019; 3 03–e2019022. [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.joghr.org/Abstract/joghr-03-e2019022

- Ouali U, Jomli R, Nefzi R, et al. Social stigma in severe mental illness in Tunisia: clinical and socio-demographic correlates. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41:S577.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. NATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH STRATEGY 2012/13-2015/16. [cited 2019 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/ETHIOPIA-NATIONAL-MENTAL-HEALTH-STRATEGY-2012-1.pdf

- Republic of Lebanon – Ministry of Public Health. Mental health and substance use – prevention, promotion, and treatment. situation analysis and strategy for lebanon 2015–2020. 2015. [cited 2019 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/MH%20strategy%20LEBANON%20ENG.pdf

- Suleiman DE. Mental health disorders in Nigeria: a highly neglected disease. Ann Nigerian Med. 2016;10:47–48.

- Onyemelukwe C. Stigma and mental health in Nigeria: some suggestions for law reform. J Law Policy Glob. 2016;55:63‑8.

- Herman AA, Stein DJ, Seedat S, et al. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. South Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):339–344.

- El Masaiti A. One out of two people is mentally ill: gruesome reality of mental health care in Morocco. 2017. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2017/07/224718/mentally-ill-mental-health-care-morocco/

- Hendler R, Kidia K, Machando D, et al. “We are not really marketing mental health”: mental health advocacy in Zimbabwe. PloS One. 2016;11(9):e0161860.

- World Health Organization. Mental health atlas. Geneva; 2017. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272735/9789241514019-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Hanna F, Barbui C, Dua T, et al. Global mental health: how are we doing? World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):367–368.

- Ridgwell H. Science and health. Zimbabwe tackles mental health with ‘friendship benches; 2017 [cited 2019 Oct 8].. Available from: https://www.voanews.com/a/zimbabwe-friendship-bench-mental-health-treatment/3661639.html

- MENTAL HEALTH CARE IN GHANA. Chapter 3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. providing sustainable mental and neurological health care in Ghana and Kenya: workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [cited 2019 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/read/21793/chapter/4.

- Roberts M, Asare JB, Mogan C, et al. The mental health system in Ghana; 2013. [cited 2019 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/innovation/research/The-Mental-Health-System-in-Ghana-Report.pdf

- Gureje O, Abdulmalik J, Kola L, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care in Nigeria: report of a demonstration project using the mental health gap action programme intervention guide. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):242.

- Spagnolo J, Champagne F, Leduc N, et al. Mental health knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy among primary care physicians working in the Greater Tunis area of Tunisia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018;12(1):63.

- Seedat S, Williams DR, Herman AA, et al. Mental health service use among South Africans for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. South Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):346–352.

- WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme. mhGAP intervention guide; 2016. [cited 2019 Apr 6]. Available from: file:///C:/Users/mail/Downloads/9789241549790-eng.pdf.

- WHO. Mental health atlas 2011 - department of mental health and substance abuse, WHO. [cited 2019 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles/en/#G

- Addisu F, Wondafrash M, Chemali Z, et al. Length of stay of psychiatric admissions in a general hospital in Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9:13.

- Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):240–249.

- Ofori-Asenso R, Agyeman AA. Irrational use of medicines – a summary of key concepts. Pharmacy. 2016;4:35.

- Oppong S, Kretchy IA, Imbeah EP, et al. Managing mental illness in Ghana: the state of commonly prescribed psychotropic medicines. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10:28.

- Acosta A, Vanegas EP, Rovira J, et al. Medicine shortages: gaps between countries and global perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:763.

- WHO-AIMS. Mental health systems in selected low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis; 2009. [cited 2019 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/who_aims_report_final.pdf

- Mendenhall E, De Silva MJ, Hanlon C, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:33–42.

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Jama. 2004;291(21):2581–2590.

- Ahmad I, Khalily MT, Hallahan B. Reasons associated with treatment non-adherence in schizophrenia in a Pakistan cohort. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;30:39–43.

- Ezenduka C, Ubochi VN, Ogbonna BO. The utilization pattern and costs analysis of psychotropic drugs at a neuropsychiatric hospital in Nigeria. Br J Pharm Res. 2014;4(3):325–337.

- Read UM, Doku VCK. Mental health research in Ghana: a literature review. Ghana Med J. 2012;46(2 Suppl):29–38.

- Roberts M, Mogan C, Asare JB. An overview of Ghana’s mental health system: results from an assessment using the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8:16.

- Naqvi HA, Sabzwari S, Hussain S, et al. General practitioners’ awareness and management of common psychiatric disorders: a community-based survey from Karachi, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(5):446–453.

- Armiyau AY. A review of stigma and mental illness in Nigeria. J Clin Case Rep. 2015;5:488.

- Kajawu L Traditional versus contemporary medicine: mental illness in Zimbabwe; 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 10]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/traditional-versus-contemporary-medicine-mental-illness-in-zimbabwe-82764

- Murthy SR. Lessons from the Erwadi tragedy for mental health care in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43(4):362–366.

- Kapungwe A, Cooper S, Mwanza J, et al. Mental illness – stigma and discrimination in Zambia. Afr J Psychiatry. 2010;13(3):192–203.

- Jombo HE, Idung AU. Stigmatising attitudes towards persons with mental illness among university students in Uyo, South-South Nigeria. IInt J Health Sci Res. 2018;8(4):24–31.

- Chadda RK. Caring for the family caregivers of persons with mental illness. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56(3):221–227.

- Kohrt BA, Rasmussen A, Kaiser BN, et al. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):365–406.

- Mahomoodally MF. Traditional medicines in Africa: an appraisal of ten potent African medicinal plants. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:14.

- Nortje G, Oladeji B, Gureje O, et al. Effectiveness of traditional healers in treating mental disorders: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):154–170.

- James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, et al. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e000895.

- Becker TD, Ho-Foster AR, Poku OB, et al. “It’s when the trees blossom”: explanatory beliefs, stigma, and mental illness in the context of HIV in Botswana. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(11):1566–1580.

- Mahmood S, Hussain S, Ur Rehman T, et al. Trends in the prescribing of antipsychotic medicines in Pakistan: implications for the future. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):51–61.

- Centre for Mental health Law and Policy. Quality rights Gujarat; 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://cmhlp.org/stories-of-changes/quality-rights-gujarat/

- Rekhis M. Rights of people with mental disorders: realities and perceptions; 2015. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/quality_rights/QR_Tunisia.pdf?ua=1

- Parwiz K Implementation of WHO quality rights assessment in Kabul mental health hospital. [cited 2019 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/quality_rights/QR_Afghanistan.pdf?ua=1

- Who quality rights in mental health– Ghana, fact sheet. [cited 2019 Oct 9]. Available from: http://qualityrightsgh.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/FACT-SHEET.pdf

- WHO and mhGAP. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) – version 2.0. [cited 2019 Mar 3]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250239/1/9789241549790-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Keynejad RC, Dua T, Barbui C, et al. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: a systematic review of evidence from low and middle-income countries. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(1):30–34.

- Pathare S, Funk M, Drew Bold N, et al. Systematic evaluation of the QualityRights programme in public mental health facilities in Gujarat, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;1–8.

- Funk M, Drew N. WHO QualityRights: transforming mental health services. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):826–827.

- Gureje O, Seedat S, Kola L, et al. Partnership for mental health development in Sub-Saharan Africa (PaM-D): a collaborative initiative for research and capacity building. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;28(4):389–396.

- Acharya B, Maru D, Schwarz R, et al. Partnerships in mental healthcare service delivery in low-resource settings: developing an innovative network in rural Nepal. Global Health. 2017;13(1):2.

- Nartey AK, Badu E, Agyei-Baffour P, et al. The predictors of treatment pathways to mental health services among consumers in Ghana. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(2):300–310.

- Jin H, McCrone P. Cost-of-illness studies for bipolar disorder: systematic review of international studies. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(4):341–353.

- Bobo WV, Diagnosis T. Management of bipolar I and II disorders: clinical practice update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(10):1532–1551.

- Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S3–11.

- Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, et al. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18008.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Bipolar Disorder: the NICE Guideline on the Assessment and Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults, Children and Young People in Primary and Secondary Care. NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence); 2014.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170.

- Severus E, Bauer M. Diagnosing bipolar disorders in DSM-5. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2013;1:14.

- Angst J, Rossler W, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Differences between unipolar mania and bipolar-I disorder: evidence from nine epidemiological studies. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):437–448.

- Angst J, Gamma A, Bowden CL, et al. Evidence-based definitions of bipolar-I and bipolar-II disorders among 5,635 patients with major depressive episodes in the bridge study: validity and comorbidity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263(8):663–673.

- Vinberg M, Mikkelsen RL, Kirkegaard T, et al. Differences in clinical presentation between bipolar I and II disorders in the early stages of bipolar disorder: a naturalistic study. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:521–527.

- Chrobak AA, Siwek M, Dudek D, et al. Content overlap analysis of 64 (hypo)mania symptoms among seven common rating scales. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27(3):e1737.

- Verdolini N, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Murru A, et al. Mixed states in bipolar and major depressive disorders: systematic review and quality appraisal of guidelines. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(3):196–222.

- Angst J, Merikangas KR, Cui L, et al. Bipolar spectrum in major depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(8):741–748.

- Parker G, Fletcher K. Differentiating bipolar I and II disorders and the likely contribution of DSM-5 classification to their cleavage. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:57–64.

- Betzler F, Stover LA, Sterzer P, et al. Mixed states in bipolar disorder - changes in DSM-5 and current treatment recommendations. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21(4):244–258.

- Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, et al. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1561–1572.

- Ferrari AJ, Stockings E, Khoo JP, et al. The prevalence and burden of bipolar disorder: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(5):440–450.

- Clemente AS, Diniz BS, Nicolato R, et al. Bipolar disorder prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2015;37(2):155–161.

- Vassos E, Agerbo E, Mors O, et al. Urban-rural differences in incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(5):435–440.

- Carta MG, Moro MF, Piras M, et al. Megacities, migration and an evolutionary approach to bipolar disorder: a study of Sardinian immigrants in Latin America. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2019.

- Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, et al. Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(8):121–127.

- Heinz A, Deserno L, Reininghaus U. Urbanicity, social adversity and psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):187–197.

- Khazaei S, Armanmehr V, Nematollahi S, et al. Suicide rate in relation to the human development index and other health related factors: a global ecological study from 91 countries. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7(2):131–134.

- Dell’Osso B, Grancini B, Vismara M, et al. Age at onset in patients with bipolar I and II disorder: a comparison of large sample studies. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:57–63.

- Shah N, Grover S, Rao GP. Clinical practice guidelines for management of bipolar disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(Suppl 1):S51–s66.

- Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 bipolar I disorder: results from the National epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions – III. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:310–317.

- Azale G, Araya T, Melaku E. More than half of bipolar patients attending Emanuel mental specialized hospital has poor quality of life, Emanuel mental specialized hospital, Ethiopia: facility-based cross-sectional study design. J Psychiatry. 2018;21:454.

- Hirschfeld RM. Screening for bipolar disorder. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(7 Suppl):S164–9.

- Kronfol Z, Zakaria Khalil M, Kumar P, et al. Bipolar disorders in the Arab world: a critical review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1345:59–66.

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–251.

- Samalin L, Vieta E, Okasha TA, et al. Management of bipolar disorder in the intercontinental region: an international, multicenter, non-interventional, cross-sectional study in real-life conditions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25920.

- Esan O, Esan A. Epidemiology and burden of bipolar disorder in Africa: a systematic review of data from Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(1):93–100.

- Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–493.

- The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG). 3-4% of South Africans have bipolar disorder. [cited 2019 Sept 8]. Available from: http://www.sadag.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=47:3-4-of-south-africans-have-bipolar-disorder&catid=57&Itemid=149

- Bouchra O, Maria S, Abderazak O. Screening of the unrecognised bipolar disorders among outpatients with recurrent depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study in psychiatric hospital in Morocco. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:247.

- Derbel C, Feki R, Ben Nasr S, et al. The late-onset bipolar disorder: a comparative study. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41S:S106–S169 (EW0024).

- Haycox A. Why cancer? PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(7):625–627.

- Simoens S, Picavet E, Dooms M, et al. Cost-effectiveness assessment of orphan drugs: a scientific and political conundrum. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(1):1–3.

- Cohen D. Cancer drugs: high price, uncertain value. BMJ. 2017;359:j4543.

- Luzzatto L, Hyry HI, Schieppati A, et al. Outrageous prices of orphan drugs: a call for collaboration. Lancet. 2018;392(10149):791–794.

- Williams MD, Shah ND, Wagie AE, et al. Direct costs of bipolar disorder versus other chronic conditions: an employer-based health plan analysis. Psychiatric Serv. 2011;62(9):1073–1078.

- Kleine-Budde K, Touil E, Moock J, et al. Cost of illness for bipolar disorder: a systematic review of the economic burden. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(4):337–353.

- Addo R, Agyemang SA, Tozan Y, et al. Economic burden of caregiving for persons with severe mental illness in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PloS One. 2018;13(8):e0199830.

- Sharma P, Das SK, Deshpande SN. An estimate of the monthly cost of two major mental disorders in an Indian metropolis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48(3):143–148.

- Eddahby S, Kadri N, Moussaoui D. Fasting during Ramadan is associated with a higher recurrence rate in patients with bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):97.

- Fajutrao L, Locklear J, Priaulx J, et al. A systematic review of the evidence of the burden of bipolar disorder in Europe. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2009;5:3.

- Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality from mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in the global burden of disease study 2010. In: Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, et al., editors. Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: disease control priorities. 3rd ed. Vol. 4. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank (c) 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2016;41–66.

- WHO. Suicide - key facts; 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- Schaffer A, Isometsa ET, Tondo L, et al. International society for bipolar disorders task force on suicide: meta-analyses and meta-regression of correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):1–16.

- Outhoff K. Bipolar disorder: an update. S Afr Family Pract. 2017;59(4):6–10.

- Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Tabares-Seisdedos R, et al. Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: an extensive review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(5):285–297.

- Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G. Health care utilization and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(6):398–405.

- Kebede D, Fekadu A, Shibre KT, et al. The 11-year functional outcome of bipolar and major depressive disorders in Butajira, Ethiopia. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2019;32:68–76.

- Marrag I, Hajji K, Hadj Ammar M, et al. [Bipolar disorder and quality of life: a cross-sectional study including 104 Tunisian patients]. L’Encephale. 2015;41(4):355–361.

- O’Donnell LA, Ellis AJ, Van de Loo MM, et al. Mood instability as a predictor of clinical and functional outcomes in adolescents with bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;236:199–206.

- Faurholt-Jepsen M, Frost M, Busk J, et al. Differences in mood instability in patients with bipolar disorder type I and II: a smartphone-based study. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):5.

- Malhi GS, Outhred T, Morris G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208(5):219–225.

- Reddy YJ, Jhanwar V, Nagpal R, et al. Prescribing practices of Indian psychiatrists in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(5):458–469.

- Sahoo S, Grover S, Malhotra R, et al. Internalized stigma experienced by patients with first-episode depression: a study from a tertiary care center. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;34:21–29.

- Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British association for psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495–553.

- Sajatovic M, DiBiasi F, Legacy SN. Attitudes toward antipsychotic treatment among patients with bipolar disorders and their clinicians: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2285–2296.

- Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health, WHO. mhGAP in Ethiopia: proof of ConCEPt 2013. [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/mhGap%20in%20Ethiopia-%20Proof%20of%20Concept.pdf

- Haque M, McKimm J, Godman B, et al. Initiatives to reduce postoperative surgical site infections of the head and neck cancer surgery with a special emphasis on developing countries. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19(1):81–92.

- Godman B, Wettermark B, van Woerkom M, et al. Multiple policies to enhance prescribing efficiency for established medicines in Europe with a particular focus on demand-side measures: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:106.

- Godman B, Malmstrom RE, Diogene E, et al. Are new models needed to optimize the utilization of new medicines to sustain healthcare systems? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8(1):77–94.

- Godman B, Bucsics A, Vella Bonanno P, et al. Barriers for access to new medicines: searching for the balance between rising costs and limited budgets. Front Public Health. 2018;6:328.

- Godman B, Malmstrom RE, Diogene E, et al. Dabigatran – a continuing exemplar case history demonstrating the need for comprehensive models to optimize the utilization of new drugs. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:109.

- Ermisch M, Bucsics A, Vella Bonanno P, et al. Payers’ views of the changes arising through the possible adoption of adaptive pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:305.

- Campbell SM, Godman B, Diogene E, et al. Quality indicators as a tool in improving the introduction of new medicines. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(2):146–157.

- Godman B, Shrank W, Andersen M, et al. Policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in europe: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:141.

- Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, et al. Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: an overview. PloS One. 2017;12(12):e0190147.

- Bochenek T, Abilova V, Alkan A, et al. Systemic measures and legislative and organizational frameworks aimed at preventing or mitigating drug shortages in 28 European and Western Asian Countries. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:942.

- World Bank. World bank country and lending groups – country classifications; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 3]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- Ibrahim AW, Pindar SK, Yerima MM, et al. Medication-related factors of non adherence among patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: outcome of a cross-sectional survey in Maiduguri, North-eastern Nigeria. J Neurosci Behav Health. 2015;7(5):31–39.

- Dodd S, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. Reliability of the mood disorder questionnaire: comparison with the structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV-TR in a population sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(6):526–530.

- Gitlin M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):27.

- Malhi GS, Gessler D, Outhred T. The use of lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder: recommendations from clinical practice guidelines. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:266–280.

- Rybakowski JK. Challenging the negative perception of lithium and optimizing its long-term administration. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:349.

- Grande I, Vieta E. Pharmacotherapy of acute mania: monotherapy or combination therapy with mood stabilizers and antipsychotics? CNS Drugs. 2015;29(3):221–227.

- Commodore-Mensah Y, Samuel LJ, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, et al. Hypertension and overweight/obesity in Ghanaians and Nigerians living in West Africa and industrialized countries: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2014;32(3):464–472.

- Cois A, Day C. Obesity trends and risk factors in the South African adult population. BMC Obes. 2015;2:42.

- World Health Organization – Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. Botswana; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/bwa_en.pdf?ua=1

- Adekanmbi VT, Uthman OA, Erqou S, et al. Epidemiology of prediabetes and diabetes in Namibia, Africa: A multilevel analysis. J Diabetes. 2019;11(2):161–172.

- WHO. World Health Organisation, diabetes fact sheet July 2016. [cited 2019 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/

- IDF diabetes atlas 8th edition 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/resources/2017-atlas.html

- Ofori-Asenso R, Agyeman AA, Laar A, et al. Overweight and obesity epidemic in Ghana – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1239.

- Werfalli M, Engel ME, Musekiwa A, et al. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes among older people in Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):72–84.

- Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, et al. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2231–2241.

- Wang H, Wolock TM, Carter A, et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980-2015: the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(8):e361–87.

- Gaida R, Truter I, Grobler C, et al. A review of trials investigating efavirenz-induced neuropsychiatric side effects and the implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14(4):377–388.

- Boxler D. Psychiatric times. FDA approves vraylar (Cariprazine) for bipolar depression; 2019. [cited 2019 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/bipolar-disorder/fda-approves-vraylar-cariprazine-bipolar-depression

- Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1249–1262.

- Fela-Thomas AL, Olotu OS, Esan O. Risk of manic switch with antidepressants use in patients with bipolar disorder in a Nigerian neuropsychiatric hospital. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2018;24:1215.

- Valenti M, Pacchiarotti I, Bonnin CM, et al. Risk factors for antidepressant-related switch to mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):e271–6.

- Peters EM, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Melancholic symptoms in bipolar II depression and responsiveness to lamotrigine in an exploratory pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38(5):509–512.

- Faurholt-Jepsen M. Electronic monitoring in bipolar disorder. Dan Med J. 2018;65:3.

- Jaracz J, Rudnicka ET, Bierejszyk M, et al. The pattern of pharmacological treatment of bipolar patients discharged from psychiatric units in Poland. Pharmacol Rep. 2018;70(4):694–698.

- Patton DE, Hughes CM, Cadogan CA, et al. Theory-based interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults prescribed polypharmacy: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(2):97–113.

- Carmona-Huerta J, Castiello-de Obeso S, Ramirez-Palomino J, et al. Polypharmacy in a hospitalized psychiatric population: risk estimation and damage quantification. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):78.

- Ulley J, Harrop D, Ali A, et al. Deprescribing interventions and their impact on medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):15.

- Al-Taweel DM, Alsuwaidan M. A medication assessment tool to evaluate prescribers’ adherence to evidence-based guidelines in bipolar disorder. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(4):897–905.

- Niaz Q, Godman B, Massele A, et al. Validity of World Health Organisation prescribing indicators in Namibia’s primary healthcare: findings and implications. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(5):338–345.

- Fekadu A, Hanlon C, Thornicroft G, et al. Care for bipolar disorder in LMICs needs evidence from local settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):772–773.

- Republic of Ghana. Ministry of Health (GNDP) Standard Treatment Guidelines. 7th ed; 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.dropbox.com/s/p1218b0s2tv60fs/STG%20GHANA%202017.pdf?dl=0

- Trivedi JK, Sareen H, Yadav VS, et al. Prescription pattern of mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder at a tertiary health care centre in north India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(2):131–134.

- Onyeama M, Agomoh A, Jombo E. Bipolar disorder in Enugu, South East Nigeria: demographic and diagnostic characteristics of patients. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22(Suppl 1):S152–7.

- Ashara HH. Mania and hypomania bipolar disorder. Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative (MANI); 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.mentallyaware.org/mania-and-hypomania-in-bipolar-disorder/

- Obiora N. What is bipolar disorder, how to recognise it and treatment options. Pulse; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.pulse.ng/lifestyle/beauty-health/metal-health-awareness-what-is-bipolar-disorder-how-to-recognise-it-and-treatment/94lvnsk

- Jombo HE, Idung AU. Medication related factors of adherence and attitude to medication among outpatients with bipolar disorder in Uyo, South-South Nigeria. Int Neuropsychiatr Dis J. 2017;1–10.