1. Introduction

As the obese population increases worldwide, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the most common form of liver disease, with a reported global prevalence of 25.2% [Citation1]. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a more severe form of NAFLD. The precise natural history of NAFLD/NASH remains uncertain. However, NASH is rapidly becoming the leading cause of end-stage liver disorders or liver transplants and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). As a result, it poses critical health issues from both a medical and a socioeconomic global viewpoint.

There are many conditions that can cause NAFLD, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, lipotoxicity, genetic mutation, ethnic differences, and underlying disease. All of these and their complications compound the many uncertainties in the management of NAFLD/NASH.

2. NAFLD/NASH and drug treatment

Lifestyle interventions, such as caloric restriction and exercise therapy, are playing central roles in the treatments of NAFLD/NASH [Citation2]. However, lifestyle improvements can be difficult to achieve and maintain, emphasizing the dire need for pharmacotherapy. Yet, to date, no pharmacotherapy has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for NAFLD and NASH [Citation2,Citation3]. NAFLD/NASH is a reflection of adipose tissue dysfunction, insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, and is concomitant with risk factors of metabolic syndrome [Citation1,Citation4]. The prevalence of comorbidities associated with NAFLD has been reported to be 51%, 23%, 69%, 39%, and 43% for obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, respectively [Citation1]. It is theoretically possible that specific treatments could have distinctive effects on NAFLD/NASH and its associated comorbidities. The current recommendation is to apply drug treatment in accordance with each factor of the metabolic syndrome associated with NAFLD/NASH () [Citation5].

3. Alcoholic steatohepatitis and nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and NASH, two different diseases, are often contrasted because these diseases present similar imaging and histology findings. Currently, the diagnoses of NAFLD exclude excessive alcohol consumption and other chronic liver diseases. However, since fatty liver caused by nutritional metabolic disorders can coexist with other chronic liver diseases, a new disease concept, “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) “, was proposed in 2020 in a consensus statement among many hepatologists [Citation6].

4. Should treatment of NAFLD Improve fibrosis or steatosis?

In the report investigating the prognosis of NAFLD cases, fibrosis in liver tissue was found to be the only histologic factor associated with long-term survival [Citation7]. In contrast, the clinical significance of assessing the severity of hepatic steatosis remains unclear. Recently, a study that followed more than 4,000 patients who had undergone the measurement of the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), a vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE)-based measurement for quantifying hepatic steatosis via ultrasound attenuation in the liver, showed that neither the presence nor the severity of hepatic steatosis related liver-related events predicted the occurrence of cancer, or cardiovascular events in the short term [Citation8]. Therefore, longitudinal cohort studies are needed to assess these clinical implications for improving fatty liver.

5. Proper liver fibrosis monitoring

Among the patients with NAFLD, the most important subjects for drug treatment are as follows: (1) those with advanced hepatic fibrosis and the highest hazard of progression to cirrhosis, (2) those with cirrhosis, and (3) those with recurrent NASH after liver transplants. The prevention of liver-related events due to the progression of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is particularly important.

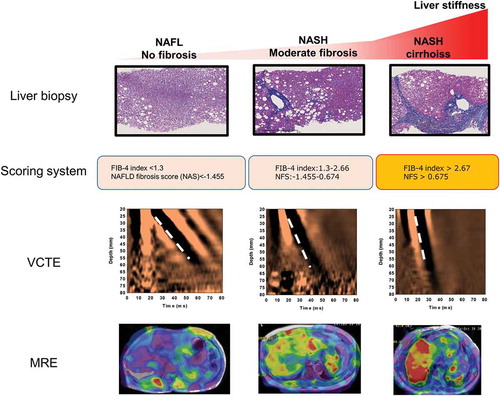

Today, a histopathological assessment is used as the accepted standard method for the diagnosis of NASH and for staging hepatic fibrosis in NALFD patients. Nevertheless, due to its high cost and high weight as a healthcare resource, invasive liver biopsies are poorly suited as repetitive diagnosis and evaluation methods. Currently, the United States FDA Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) place biomarkers into different categories. There is considerable interest in the development of noninvasive biomarkers for (1) the diagnosis of NASH, (2) the fibrosis stage, and (3) the effects of treatments of NASH. Thus, there is a need for the further development and clinical application of fibrosis markers, scoring systems, and elastography that can accurately assess liver fibrosis over time. Serum markers of hepatic fibrosis, such as the type IV collagen 7s domain and Wisteria floribunda agglutinin-positive Mac-2-binding protein (WFA+ -M2BP), not generally used in United States and Europe, and plasma collagen type III (Pro-C3), have been utilized extensively for the estimation of fibrosis of the liver in NAFLD patients. Furthermore, there are numerous scoring systems consisting of combinations of clinical and routine laboratory parameters. Among them, the FIB-4 index and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) are established for predicting advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD based on current international guidelines [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5]. However, further data and regulatory qualifications are needed to establish their usefulness as a longitudinal assessment. Ultrasound-based and MR-based elastography techniques are expected to become optimal examinations in the follow-up of NAFLD patients, creating their own position as liver evaluation methods, instead of being used only as alternatives to liver biopsies ().

6. Genetic polymorphisms and treatment responsiveness

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) of Hispanic, African American, and European American individuals published in 2008 [Citation9] revealed that the genetic variation rs738409 (I148M) in PNPLA3 influences NAFLD. Since that report, many studies have shown that the variant of PNPLA3 rs738409 (148 M) is related to hepatic steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and even HCC in both NAFLD and alcoholic fatty liver patients. The frequency of the PNPLA3 (148 M) variant ranged from 17% in African Americans and 23% in European Americans to 49% among the Hispanic in the study [Citation9]. PNPLA3 is a protein that is not yet fully understood, however, it plays a broad role in metabolic liver diseases from hepatic steatosis to cirrhosis and HCC. Variants with other Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), such as TM6SF2, MBOAT7, and GCKR, have been shown to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of NAFLD as well [Citation10]. As genetic factors are better understood, novel preventive and therapeutic strategies are expected to be developed for precise pharmaceutical approaches for NASH in the near future.

7. Diabetes and the treatment of NAFLD/NASH

In a real-world study in four European countries, DM was reported to be the strongest contributor of cirrhosis and liver cancer in patients with NAFLD or NASH, as well as increasing the risk of developing cirrhosis and HCC by about twofold [Citation11]. In the United States, 18.2 million people are estimated to have NAFLD with type 2 DM, and of those, 6.4 million, 35%, have NASH. One current study in the United States estimates that 65,000 liver transplants, 1,370,000 cardiovascular-related deaths, and 812,000 liver-related deaths will occur over the next 20 years [Citation12]. Treatment of type 2 diabetes in these patients could likely reduce these anticipated clinical and economic burdens.

Currently, pioglitazone is the only anti-diabetic medicine recommended in the treatment guidelines for NASH [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5]. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and sodium-glucose co-transporte-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are being investigated actively as candidates for pharmacotherapy [Citation13]. As metformin has no effect on improving liver tissue in NASH, it is not recommended in the guidelines [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5]. However, metformin has been reported to have a protective effect on carcinogenesis. The continued use of metformin after the cirrhosis diagnosis has been reported to prolong the survival of these patients. Nevertheless, the long-term effects of metformin need further investigation. In their 2019 Standard of Medical Care guideline, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended that, ‘patients with T2DM and elevated liver enzyme aminotransferase (ALT) or fatty liver on ultrasound should be evaluated for the presence of NASH and liver fibrosis.’

8. NAFLD treatment for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

The question of whether NAFLD is associated with CVD directly or indirectly remains unclear, since the link between NAFLD and CVD is complex [Citation14]. One reason why CVD is a more common cause of death in NAFLD patients than liver disease itself is that the time it takes for metabolic syndrome induced hepatic steatosis to lead to cirrhosis may be longer than that for metabolic syndrome induced CVD to lead to myocardial infarction or stroke.

Metabolic syndrome plays a central and important role in causing insulin resistance leading to hepatic steatosis and, in some patients, raising CVD risk. Given that some anti-diabetic drugs, for example, pioglitazone, GLP-1RAs, and SGLT2 inhibitors, reduce CVD, the leading cause of death in NAFLD/NASH patients, future studies should explore their roles in simultaneously improving both type 2 DM and the hepatic histological feature of NAFLD/NASH while reducing cardiometabolic risk [Citation13]. Furthermore, although the effect of statins on liver tissue is unknown, it is necessary to investigate whether statins can improve prognosis through their preventive effect on atherosclerosis in NAFLD patients.

9. Expert opinion

As no effective drug treatment for NAFLD/NASH has been established, the number of people afflicted with this disease is expected to increase worldwide, particularly due to the increase in obese individuals, as well as through advances in diagnostic methods. In the last three decades, along with growing obesity and DM, NAFLD has been the only liver disease with greater prevalence [Citation15]. The development of drugs for its treatment can be divided broadly into two approaches: one to divert and utilize existing drugs approved for other diseases or tested in clinical trials and shown to have a basic safety profile (known as drug repositioning or drug repurposing); the other to initiate research and development on new drugs that can affect NASH/NAFLD. Several drugs for its treatment are in phase III trials, but are still a long way from approval. According to the updated consensus, the pathogenesis of NASH is complicated and a ‘multiple hits’ hypothesis has been proposed. Correspondingly, the pharmacotherapeutic strategies might have more than one target. In any case, an ideal treatment for NASH should be one that improves not only liver disease, but also one that reduces the risk of CVD and the development of diabetes and cancers.

Declaration of interest

M Yoneda has received research funding from Kowa Co. Ltd. Meanwhile, A Nakajima has received honoraria from Astellas Pharma Inc., EA Pharma., Merck Sharp and Dohme K.K., Kowa Co. Ltd., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. and Mylan. He has also received research funding from Kowa Co. Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Biofermin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Mylan. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zm Y, Ab K, Abdelatif D, et al., Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1): 73–84.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL–EASD–EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388–1402.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Je L, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357.

- Mendez-Sanchez N, Vc C-R, Ol R-P, et al. New aspects of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):2034.

- Watanabe S, Hashimoto E, Ikejima K, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(4):364–377.

- Eslam M, Pn N, Sk S, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–209.

- Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al., Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long–term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2): 389–97.e10.

- Liu K, Vw W, Lau K, et al. Prognostic value of controlled attenuation parameter by transient elastography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(12):1812–1823.

- Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, et al., Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12): 1461–1465.

- Eslam M, George J. Genetic contributions to NAFLD: leveraging shared genetics to uncover systems biology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(1):40–52.

- Alexander M, Ak L, Van Der Lei J, et al. Risks and clinical predictors of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma diagnose in adults with diagnosed NAFLD: real-world study of 18 million patients in four European cohorts. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):95.

- Younossi ZM, Tampi RP, Racila A, et al. Economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.S. U.S. Diabetes Care 2020;43(2):283–289.

- Cusi K. A diabetologist’s perspective of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): knowledge gaps and future directions. Liver Int. 2020;40(Suppl S1):82–88.

- Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Mantovani A. Hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis and NASH: cause or consequence? J Hepatol. 2018;68(2):335–352.

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Younossi Y, et al. Epidemiology of chronic liver diseases in the USA in the past three decades. Gut. 2020;69(3):564–568.