ABSTRACT

Introduction

Gout is an inflammatory disease triggered by deposition of urate crystals secondary to longstanding hyperuricemia, and its management implies both the treatment of flares and management of hyperuricemia. Dotinurad is a selective urate reabsorption inhibitor (SURI), potently inhibits urate transporter 1 in the apical surface of renal proximal tubular cells, and has been approved for the treatment of gout and hyperuricemia in Japan.

Areas covered

This overview of dotinurad covers nonclinical and clinical pharmacology studies in special populations and its efficacy and safety in Japanese hyperuricemic patients with and without gout.

Expert opinion

Dotinurad, as an SURI, is expected to inhibit urate reabsorption more effectively than conventional urate-lowering agents. It is noninferior to benzbromarone or febuxostat in reducing serum urate levels in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout. Its efficacy is not attenuated in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment or with hepatic impairment. At a maintenance dose of 2 or 4 mg once daily, most patients achieved the target serum urate level of ≤6 mg/dL in a long-term study. No findings that raised safety concerns, including liver injury, were identified. Dotinurad is expected to be a new therapeutic option in hyperuricemic patients with and without gout.

1. Introduction

The number of patients with gout is increasing to exceed 1 million in Japan in the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions conducted in 2016 [Citation1], and the prevalence of hyperuricemia, a common pathogenic factor in the development of gout, is similar in Japan and worldwide in a recent real-world study [Citation2]. Hyperuricemia, defined as serum urate levels of >7.0 mg/dL, affects approximately 30% of adult males in Japan with a considerable number of patients requiring treatment [Citation3,Citation4]. Persistent hyperuricemia can lead to urate crystal deposition, which in turn cause gouty arthritis [Citation5,Citation6]. In addition to monosodium urate crystal-mediated renal damage [Citation7,Citation8], it has also been reported that hyperuricemia in the absence of uric acid crystal deposition may contribute to the development of chronic kidney disease [Citation9–13]. The disease types have been conventionally classified into overproduction, reduced excretion, and mixed types. It has become clear that patients with reduced extra-renal excretion are among those who have been classified in the overproduction group [Citation14]. Therefore, the Japanese guidelines for the management of hyperuricemia and gout (third edition) classify hyperuricemia into the renal overload (overproduction and extra-renal underexcretion), renal underexcretion, and mixed types [Citation15].

The target of serum urate levels for the management of hyperuricemia is ≤6.0 mg/dL in consideration of the solubility of urate crystals [Citation15]. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors, including allopurinol, febuxostat, and topiroxostat, and uricosuric agents, including benzbromarone, probenecid, and bucolome, are used to lower serum urate levels [Citation16]. However, many patients fail to reach the target serum urate levels [Citation2]. Furthermore, allopurinol is associated with several adverse drug reactions (ADRs), including gastrointestinal effects, rash, and Stevens–Johnson’s syndrome, and the dosage is generally reduced in patients with renal impairment [Citation17]. The interpretation on the safety of febuxostat in the CARES study [Citation18] should be limited because of the high number of withdrawals and the high incidence of CV events in these patients after discontinuation. On the other hand, the CV risk of febuxostat was similar to that of allopurinol in the FAST and several other studies [Citation19]. Benzbromarone, which causes serious hepatic injury [Citation20], is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and has a potential for drug–drug interactions because it is a potent inhibitor of CYP2C9 with an inhibitory constant (Ki) of 19 nmol/L in vitro [Citation21]. Therefore, safer drugs with adequate urate-lowering effects need to be developed.

Dotinurad (Box 1), a selective urate reabsorption inhibitor (SURI), potently inhibits urate transporter 1 (URAT1) but minimally inhibits ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2), organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1), and OAT3 [Citation22]. The clinical studies discussed below demonstrated a sufficient efficacy without serious safety concerns in patients with hyperuricemia with or without gout. Consequently, dotinurad has been approved for the management of gout and hyperuricemia in Japan.

Box 1. Drug summary box

2. Mechanism of action

2.1. Transporter inhibition studies

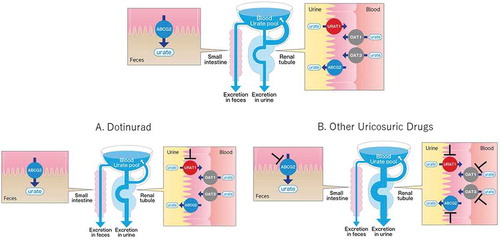

Dotinurad, benzbromarone, lesinurad, and probenecid inhibited URAT1 with IC50 values of 0.0372, 0.190, 30.0, and 165 μmol/L, respectively [Citation22]. The inhibitory effects of dotinurad on other urate transporters, including ABCG2, OAT1, and OAT3, were modest, with IC50 values of 4.16, 4.08, and 1.32 μmol/L, respectively, indicating higher selectivity for URAT1 than other existing uricosuric agents (). Dotinurad is unlikely to affect ABCG2 and OAT1/3 at clinical exposure levels and is therefore expected to inhibit urate reabsorption in the kidney without affecting urate excretion from the intestine.

Table 1. IC50 ratios for ABCG2 and OAT1/3 relative to URAT1 of dotinurad and commercially available uricosuric agents

2.2. Pharmacodynamic effects in Cebus monkeys

Dotinurad lowered plasma urate levels in a dose-dependent manner after a single oral administration, and the 0–4-h fractional excretion of urate (FEUA) increased by 180% at a dose of 30 mg/kg compared with the control (P < 0.01) in Cebus monkeys [Citation22]. The amounts of urinary urate excretion 0–8 h after administration showed a dose-dependent increasing trend, with 13.7 mg in the control group and 16.2, 22.8, and 25.3 mg in the 1, 5, and 30 mg/kg groups, respectively. These results indicate that dotinurad reduces plasma urate levels by increasing the urinary urate excretion. In contrast, benzbromarone (30 mg/kg) had a modest effect on plasma urate levels despite an increasing trend of urinary urate excretion with 19.4 mg, indicating that dotinurad effectively decreased plasma urate levels at low doses in Cebus monkeys.

2.3. Pharmacological features

As shown in a schematic diagram produced on the basis of these results (), SURIs, such as dotinurad, effectively reduce the urate pool by inhibiting only the urate reabsorption in the kidney, whereas other uricosuric drugs modestly reduce the urate pool because of their inhibitory effects on urate secretion transporters. To reduce serum urate levels as those after SURIs, nonselective inhibitors need to inhibit URAT1 more markedly at higher doses for an extensive excretion of urate, which poses a risk of increased incidence of urinary calculi [Citation23].

Figure 1. Comparison of the potency of selective urate reabsorption inhibitors and other uricosuric drugs. (upper) The usual state of urate handling. (A) SURI selectively inhibits URAT1, leading to a potent reduction of the urate pool. (B) Other uricosuric drugs inhibit URAT1 and ABCG2 and/or OAT1/3. Arrow width indicates the amount of urate

3. Effects in special populations

3.1. Effects in young and older populations

The pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters and pharmacodynamics (PD) of dotinurad were evaluated in older (≥65 years) and young (20–35 years) males and females after a single oral dose (1 mg) [Citation24]. Changes in dotinurad plasma concentrations were similar across the groups (Tmax, 2.00–2.83 h; T1/2, 9.28–10.92 h; ). This suggests that dotinurad PK profiles are suitable for once-daily oral administration in older and young males and females.

Table 2. PK parameters of dotinurad in plasma and urine

3.2. Effects in subjects with mild to moderate renal impairment

The PK, PD, and safety of dotinurad were evaluated in subjects with renal impairment after a single oral dose (1 mg) in an open-label, single-dose clinical pharmacology study [Citation25]. There was no significant difference in dotinurad PK profiles in subjects with mild (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2) or moderate (eGFR, 30 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) renal impairment and in those with normal (eGFR, ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) renal function. The maximum reduction rate in serum urate levels and the FE ratio (FE0–24/FE−24–0) were significantly lower in subjects with moderate renal impairment than in those with normal renal function, whereas other PD parameters were similar between these groups. No notable adverse events (AEs) or ADRs were observed in this study. These findings suggest that no dose adjustment is necessary when dotinurad is administered to patients with mild to moderate renal impairment.

3.3. Effects in subjects with mild to severe hepatic impairment

In an open-label, single-dose study, the PK, PD, and safety of dotinurad were evaluated in subjects with hepatic impairment and normal hepatic function after a single oral dose (4 mg) [Citation26]. Although the geometric mean ratio of the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) was lower in the moderate and severe hepatic impairment groups, only the moderate hepatic impairment group had a lower Cmax than the normal hepatic function group following adjustment for body weight, and no meaningful differences in other PK parameters were observed between the groups. Changes in serum urate levels after dotinurad administration were similar in all groups, and no remarkable safety concerns were raised in any group. There were no clinically meaningful effects of hepatic impairment on the PK, PD, or safety of dotinurad. These findings indicate that dotinurad can be administered to patients with hepatic impairment without dose adjustment.

4. Phase 2 and 3 clinical studies

4.1. Late phase 2 study

In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, phase 2 study, 200 hyperuricemic patients with or without gout were assigned to 5 groups: placebo and 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg dotinurad [Citation27]. The mean percentage change in serum urate levels from the baseline to the final visit in the placebo, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg dotinurad groups was −2.83%, 21.81%, 33.77%, 42.66%, and 61.09%, respectively (). The percentage of patients achieving serum urate levels ≤6.0 mg/dL at the final visit was 0%, 23.1%, 65.9%, 74.4%, and 100%, respectively (). AEs were observed in 20 (51.3%), 24 (60.0%), 21 (50.0%), 20 (51.3%), and 13 (32.5%) patients in the placebo, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg dotinurad groups, respectively. ADR incidences were comparable among the groups and did not increase with dose escalation.

Figure 2. Changes in serum urate levels from baseline to week 12. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. Adopted from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation27] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer nature

![Figure 2. Changes in serum urate levels from baseline to week 12. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. Adopted from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation27] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer nature](/cms/asset/73a4e257-f693-4d36-9fb8-289294abf0dc/ieop_a_1918102_f0002_b.gif)

Figure 3. Percentage of patients with serum urate levels of ≤6 mg/dL at the final visit. Reproduced from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation27] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer Nature. The length of the error bars represents a 95% confidence interval for the mean of the achievement percentage. Dose response was significant at P < 0.001 (Cochran–Armitage test). *P < 0.001 versus the placebo group; †P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 0.5 mg group; ‡P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 1 mg group; §P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 2 mg group; χ2 test

![Figure 3. Percentage of patients with serum urate levels of ≤6 mg/dL at the final visit. Reproduced from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation27] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer Nature. The length of the error bars represents a 95% confidence interval for the mean of the achievement percentage. Dose response was significant at P < 0.001 (Cochran–Armitage test). *P < 0.001 versus the placebo group; †P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 0.5 mg group; ‡P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 1 mg group; §P < 0.001 versus the dotinurad 2 mg group; χ2 test](/cms/asset/e9d3b556-5222-4b8b-aae3-800e4f48c803/ieop_a_1918102_f0003_oc.jpg)

4.2. Phase 3 study of dotinurad compared with benzbromarone

In a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, dose escalation, phase 3 study, 201 Japanese hyperuricemic patients with or without gout received either dotinurad (initially 0.5 mg for the first 2 weeks, 1 mg for the subsequent 4 weeks, and 2 mg from week 6 to week 14) or benzbromarone (25 mg for the first 2 weeks and 50 mg from week 2 to week 14) [Citation28]. The primary endpoint, the percentage change in serum urate levels from the baseline to the final visit, was 45.9% and 43.8% in the dotinurad and benzbromarone groups, respectively. Noninferiority of dotinurad to benzbromarone in lowering serum urate levels was verified with the predefined noninferiority margin (95% CI: −1.27% to 5.37%). The percentages of patients that achieved serum urate levels ≤6.0 mg/dL in the dotinurad and benzbromarone groups were 86.2% (88/102 patients) and 83.6% (82/98 patients), respectively, at the final visit, showing no significant differences (P= 0.693; Fisher’s exact test).

The incidence of AEs and ADRs was similar in the 2 groups. The incidence of gouty arthritis was 7.8% and 5.1% in the dotinurad and benzbromarone groups, respectively; the severity of all events of gouty arthritis was mild or moderate.

4.3. Phase 3 study of dotinurad compared with febuxostat

In a randomized, double-blind, forced-titration study, 203 hyperuricemic patients with or without gout received either dotinurad or febuxostat initially at 0.5 and 10 mg once daily, followed by dose titration to 2 and 40 mg once daily, respectively, over 14 weeks [Citation29]. The mean percentage change in serum urate levels from baseline to the final visit, the primary endpoint, was 41.8% and 44.0% in the dotinurad and febuxostat groups, respectively. The mean difference in the rate of decrease in the serum urate level between the 2 groups was −2.17% (two-sided 95% CI: −5.26% to 0.92%), demonstrating the noninferiority of dotinurad to febuxostat. The percentage of patients achieving serum urate levels ≤6.0 mg/dL at the final visit was similar between the 2 groups.

The incidence of ADRs was comparable between the 2 groups. The incidence of gouty arthritis was 3.0% and 5.9% in the dotinurad and febuxostat groups, respectively; all these events were mild or moderate in severity. No urinary calculi were observed in either group.

4.4. Phase 3 long-term administration study

In an open-label study, 330 hyperuricemic patients with or without gout received dotinurad for up to 34 or 58 weeks; the initial dose was 0.5 mg once daily for 2 weeks, followed by 1 mg once daily for 4 weeks, and a maintenance dose of 2 or 4 mg once daily for 28 or 52 weeks [Citation30]. The serum urate level gradually decreased according to the dose-escalation scheme from baseline to week 10 and was maintained stably until week 34 or 58 ().

Figure 4. Changes in serum urate levels from baseline to week 58 during daily oral administration of dotinurad. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. *P < 0.05. Adopted from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation30] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer nature

![Figure 4. Changes in serum urate levels from baseline to week 58 during daily oral administration of dotinurad. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. *P < 0.05. Adopted from Hosoya T, et al. [Citation30] under the terms of the creative commons attribution license with permission of Springer nature](/cms/asset/3708c0d3-8c9a-4f2b-b212-e4eabcaadd66/ieop_a_1918102_f0004_b.gif)

The rate of achieving serum urate levels ≤6.0 mg/dL was retained after long-term administration. Of the 43 patients who failed to achieve serum urate levels ≤6.0 mg/dL on the maintenance dose of 2 mg, 41 patients whose dose was increased to 4 mg achieved the target serum urate level, indicating that the increased dose enhanced the serum urate-lowering effect. Percentage changes in serum urate levels from baseline to weeks 34 and 58 were similar in patients with normal renal function and in those with mild and moderate renal impairment at baseline (). A small but significant increase in eGFR from baseline to the final visit was observed in patients receiving 2 mg, which may warrant a future study of long-term dotinurad administration on the possible reduction of renal impairment.

Table 3. Percentage changes in serum urate levels at weeks 34 and 58 in patients in different renal function categories

The incidence of ADRs was 21.8%, including one serious ADR (gastric cancer stage I). The incidence of gouty arthritis was 13.0% during the entire treatment period and ≤1.0% from week 34 to week 58. This suggests that long-term administration of dotinurad may suppress acute inflammation in gouty arthritis. The incidence of urinary calculi was 1.5%; however, none were considered serious or required treatment.

5. Pharmacokinetic features

5.1. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibitory potential (in vitro)

Dotinurad inhibited CYP2C9 with a Ki of 10.4 μmol/L but not other major CYP isoforms (CYP1A2, 2A6, 2B6, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4) at up to 100 μmol/L in human liver microsomes [Citation31]. Calculation of the R-value, based on the Guidelines on drug interaction for drug development and appropriate provision of information, suggests a low potential risk of drug–drug interactions via CYP inhibition [Citation32].

5.2. Drug–drug interaction study of dotinurad and oxaprozin

Glucuronide and sulfate conjugates are the major metabolites of dotinurad that are excreted in urine [Citation24–26]. Because nonclinical studies suggested potential effects of oxaprozin, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, on the plasma protein binding and glucuronidation of dotinurad, the PK and safety of a single dose of 4 mg dotinurad were evaluated in 12 healthy adult males with and without 600 mg oxaprozin in an open-label, two-period, add-on study [Citation33]. Compared with dotinurad alone, coadministration with oxaprozin was associated with a 34.3% decrease in the urinary excretion rate of the glucuronide conjugates and a 16.5% increase in the AUC0–inf of dotinurad; however, these effects were within the standard range specified in the guidelines for drug–drug interactions [Citation32]. No safety concerns were raised after coadministration with oxaprozin.

6. Safety

6.1. Risk assessment of drug-induced liver injury in nonclinical studies

The risk of drug-induced liver injury was evaluated using the previously reported procedures for hepatocellular injury, cholestasis, activation of the apoptotic pathway, covalent binding, inhibition of mitochondria functions, and stimulation of immune response [Citation34]. In 13-, 26-, and 39-week oral dose toxicity studies of dotinurad in rats and monkeys, hepatocellular injury, cholestasis, or apoptosis was not observed at exposure levels up to 264 to 781 times the clinical exposure (). In the in vitro studies, covalent binding of 14C-dotinurad to human hepatocytes indicates that dotinurad is classified in the safe zone based on the zone classification system in consideration of the maximum clinical dose (4 mg) [Citation35], the effects of dotinurad on mitochondrial respiration and mitochondrial enzyme complexes were much smaller than those of benzbromarone, and the stimulation of immune response as measured by IL-8 production from THP-1 cells was observed with dotinurad at 30 μmol/L (51 times the clinical exposure). The findings in these studies suggest a much lower risk of drug-induced liver injury of dotinurad [Citation36].

Table 4. Effects of dotinurad and benzbromarone on the liver

6.2. Liver-related ADRs in clinical studies

shows the incidence of liver-related ADRs from pooled data in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout in double-blind studies, including phase 2 studies [Citation27,Citation37] and benzbromarone- and febuxostat-controlled phase 3 studies [Citation28,Citation29]. The incidence of liver-related ADRs tended to be lower in the dotinurad group than in the control groups.

Table 5. Incidence of liver-related adverse drug reactions in the pooled data from double-blind studies in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout

6.3. Others in clinical studies

There were no other particular safety concerns regarding the incidence, type, and severity of AEs associated with dotinurad.

7. Conclusions

Dotinurad, an SURI, was noninferior to benzbromarone or febuxostat in reducing serum urate levels in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout in a once-daily treatment, and its effects were similar in patients with severe hepatic impairment and in those with moderate renal impairment. In late phase 2 and long-term administration studies, most patients receiving a maintenance dose of dotinurad (2 or 4 mg) achieved the target serum urate level of ≤6 mg/dL.

8. Expert opinion

Urate-lowing therapy is indispensable in the treatment of hyperuricemia and gout; however, available treatment options are limited. Commercially available uricosuric agents, such as benzbromarone and probenecid, inhibit not only URAT1 but also other urate secretion transporters. This suggests that the selective inhibition of URAT1 would lower serum urate levels more effectively than the nonselective inhibition of urate transporters (). Dotinurad is a novel SURI that potently and selectively inhibits URAT1 but only weakly inhibits other transporters involved in urate excretion, including ABCG2 and OAT1/3. In a monkey study, the plasma urate levels were reduced to a greater extent at lower doses than benzbromarone [Citation22]. A higher efficacy was achieved with a smaller increase of urate excretion in urine than that with benzbromarone, which should be considered characteristic of SURIs.

In healthy adult male subjects, plasma dotinurad concentrations increased linearly in a dose-dependent manner after oral administration. The PK parameters, including Cmax and T1/2, were appropriate to support the once-daily dosing. The serum urate-lowering effect, PK parameters, and safety of dotinurad were similar in older and young subjects [Citation24]. Dotinurad is not metabolized via hepatic CYP enzymes and is mainly excreted as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates; therefore, the excretion of dotinurad is unlikely to be affected by an impairment in liver function [Citation31]. Hepatic impairment and mild to moderate renal impairment had no clinically relevant effects on the PK or safety of dotinurad without attenuating the efficacy of dotinurad [Citation25,Citation26]. Therefore, dotinurad can be administered without any dosage adjustment in these special populations.

In phase 3 studies involving hyperuricemic patients with or without gout, dotinurad was noninferior to benzbromarone and febuxostat in lowering serum urate levels [Citation28,Citation29].

In a long-term phase 3 study, the serum urate level gradually decreased according to the dose-escalation scheme from baseline and remained low throughout the treatment period of 58 weeks. Most patients receiving a maintenance dose achieved the target serum urate levels of ≤6 mg/dL [Citation30]. The Japanese management guidelines state that the frequency of gouty arthritis is decreased by maintaining a serum urate level of ≤6.0 mg/dL [Citation15]. In the long-term study, the incidence of gouty arthritis tended to be lower from week 34, which suggests that the long-term use of dotinurad may suppress acute inflammation in gouty arthritis. In patients with gout and moderate CKD (eGFR ≥30), dotinurad can be administered without dose adjustment and may effectively lower serum uric acid levels. Although patients with gouty attack should not be treated with a urate-lowering drug, dotinurad administration can be continued if acute gouty arthritis develops during dotinurad administration. Dotinurad can also be administered to patients with chronic tophaceous gout if arthritis is not developing. Since the number of patients is limited, it is necessary to collect evidence from a wide range of patients in clinical practice.

The incidence of ADRs, including gouty arthritis, was similar in patients receiving dotinurad and in those receiving benzbromarone or febuxostat [Citation28,Citation29]. No ADRs related to hepatic impairment or hepatic parameters were noted in the dotinurad groups. Furthermore, eGFR was unaffected by dotinurad in a long-term phase 3 study, and ADRs of renal calculi, found in 1.5% of patients, were not considered serious or required treatment [Citation30]. These indicate no safety concerns associated with the long-term use of dotinurad [Citation30].

In conclusion, these results suggest that dotinurad is a new therapeutic option in hyperuricemic patients with and without gout. SURIs might play a substantial role in urate-lowering therapy for gout, given that a non-negligible number of patients are unable to achieve the target serum urate level with conventional urate-lowering therapy.

Article Highlights

A novel urate-lowering agent has been approved for the treatment of hyperuricemia and gout.

Dotinurad is a selective urate reabsorption inhibitor (SURI). It potently and selectively inhibits urate transporter 1 (URAT1), a transporter responsible for the reabsorption of urate from the renal tubules, but only weakly inhibit other transporters involved in urate excretion, including ABCG2 and OAT1/3.

Dotinurad was noninferior to the existing urate-lowering drugs, benzbromarone and febuxostat, in lowering serum urate levels.

The serum urate-lowering effect of dotinurad is not attenuated in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment.

The serum urate-lowering effect of dotinurad is similar in patients with mild to severe hepatic impairment and in those with normal hepatic function.

The urate-lowering effect of dotinurad is retained after its long-term administration, and most patients receiving a maintenance dose of 2 or 4 mg once daily achieved target serum urate levels of ≤6 mg/dL in the treatment guidelines.

Dotinurad is expected to be a novel therapeutic option in hyperuricemic patients with and without gout.

Declaration of interest

T Hosoya has received consultant fees and/or speakers’ honoraria from Fuji Yakuhin Co., Ltd., the manufacturer of dotinurad, and/or Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. T Ishikawa and T Taniguchi are employees of Fuji Yakuhin Co., Ltd. T Takahashi is an employee of Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive survey of living conditions. 2016.

- Koto R, Nakajima A, Horiuchi H, et al. Real-world treatment of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricemia: a cross-sectional study of Japanese health insurance claims data. Mod Rheumatol. 2021;31(1):261–269.

- Hakoda M. Recent trends in hyperuricemia and gout in Japan. Japan Med Assoc J. 2012;55(4):319–323.

- Tomita M, Yokota K, Mizuno S. Significance of uric acid measurement in health checks and comprehensive medical examinations. Hyperuricemia and Gout. 2010;18:67–71.

- Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the normative aging study. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):421–426.

- Lin KC, Lin HY, Chou P. The interaction between uric acid level and other risk factors on the development of gout among asymptomatic hyperuricemic men in a prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1501–1505.

- Sellmayr M, Hernandez Petzsche MR, Ma Q, et al. Only hyperuricemia with crystalluria, but not asymptomatic hyperuricemia, drives progression of chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(12):2773–2792.

- Preitner F, Laverriere-Loss A, Metref S, et al. Urate-induced acute renal failure and chronic inflammation in liver-specific Glut9 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(5):F786–795.

- Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, et al. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):642–650.

- Obermayr RP, Temml C, Gutjahr G, et al. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(12):2407–2413.

- Hisatome I, Li P, Miake J, et al. Uric acid as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease japanese guideline on the management of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia . Circ J. 2021;85(2):130–138.

- Yin W, Zhou QL, OuYang SX, et al. Uric acid regulates NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway and further induces vascular endothelial cells injury in early CKD through ROS activation and K+ efflux. BMC Nephrol. 2019 Aug 14;20(1):319. PMID: 31412804; PMCID: PMC6694569.

- Waheed YA, Yang F, Sun D. The role of asymptomatic hyperuricemia in the progression of chronic kidney disease CKD and cardiovascular diseases CVD. Korean J Intern Med. 2020 Oct 6. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2020.340. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33045808.

- Ichida K, Matsuo H, Takada T, et al. Decreased extra-renal urate excretion is a common cause of hyperuricemia. Nat Commun. 2012;3(1):764.

- Hisatome I, Ichida K, Mineo I, et al. Japanese society of gout and uric & nucleic acids 2019 guidelines for management of hyperuricemia and gout 3rd edition. Gout and Uric & Nucleic Acids; 2020:44(Supplement):1–40.

- Otani N, Ouchi M, Kudo H, et al. Recent approaches to gout drug discovery: an update. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2020;15(8):943–954.

- Shahid H, Singh JA. Investigational drugs for hyperuricemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24(8):1013–1030.

- White WB, Saag KG, Becker MA, et al. Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1200–1210.

- Mackenzie IS, Ford I, Nuki G, et al. Long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (FAST): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1745–1757.

- Van Der Klauw MM, Houtman PM, Stricker BH, et al. Hepatic injury caused by benzbromarone. J Hepatol. 1994;20(3):376–379.

- Locuson CW II, Wahlstrom JL, Rock DA, et al. A new class of CYP2C9 inhibitors: probing 2C9 specificity with high-affinity benzbromarone derivatives. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(7):967–971.

- Taniguchi T, Ashizawa N, Matsumoto K, et al., Pharmacological evaluation of dotinurad, a selective urate reabsorption inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(1):162–170.

- Viljoen A, Chaudhry R, Bycroft J. Renal stones. Ann Clin Biochem. 2019;56(1):15–27.

- Nakatani H, Fushimi M, Sasaki T, et al. Clinical pharmacological study of dotinurad administered to male and female elderly or young subjects. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1):8–16.

- Fukase H, Okui D, Sasaki T, et al., Effects of mild and moderate renal dysfunction on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of dotinurad: a novel selective urate reabsorption inhibitor. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1):17–24.

- Kumagai Y, Sakaki M, Furihata K, et al., Dotinurad: a clinical pharmacokinetic study of a novel, selective urate reabsorption inhibitor in subjects with hepatic impairment. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 25–35.

- Hosoya T, Sano T, Sasaki T, et al., Clinical efficacy and safety of dotinurad, a novel selective urate reabsorption inhibitor, in Japanese hyperuricemic patients with or without gout: randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, confirmatory phase 2 study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 53–61.

- Hosoya T, Sano T, Sasaki T, et al., Dotinurad versus benzbromarone in Japanese hyperuricemic patient with or without gout: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 62–70.

- Hosoya T, Furuno K, Kanda S. A non-inferiority study of the novel selective urate reabsorption inhibitor dotinurad versus febuxostat in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1):71–79.

- Hosoya T, Fushimi M, Okui D, et al., Open-label study of long-term administration of dotinurad in Japanese hyperuricemic patients with or without gout. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 80–91.

- Omura K, Miyata K, Kobashi S, et al. Ideal pharmacokinetic profile of dotinurad as a selective urate reabsorption inhibitor. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2020;35(3):313–320.

- Pharmaceutical safety and environmental health bureau, ministry of health, labour and welfare, Japan. Notification No. 0723-4, 2018, Guideline on drug interaction for drug development and appropriate provision of information. pp. 21–23. [ cited 2021 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000228122.pdf [issued 2019 Feb 8]

- Furihata K, Nagasawa K, Hagino A, et al., A drug-drug interaction study of a novel, selective urate reabsorption inhibitor dotinurad and the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug oxaprozin in healthy adult males. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 36–43.

- Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):474–485.

- Nakayama S, Atsumi R, Takakusa H, et al. A zone classification system for risk assessment of idiosyncratic drug toxicity using daily dose and covalent binding. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(9):1970–1977.

- Yamada M, Miyamoto K, Matsumoto K, et al. Nonclinical investigation of dotinurad on the risk of liver toxicity. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2020;48(2):157–164.

- Hosoya T, Sano T, Sasaki T, et al., Clinical efficacy and safety of dotinurad, a novel selective urate reabsorption inhibitor, in Japanese hyperuricemic patients with or without gout: an exploratory, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group early phase 2 study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(Suppl1): 44–52.

- Taniguchi T, Ashizawa N. Pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy of dotinurad (URECE® tablets), a novel hypouricemic agent. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2020;155(6):426–434.