ABSTRACT

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are the most common noncancerous tumors in women of childbearing age. This review was developed to evaluate the current role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists in the therapy of symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Areas covered

There is a great need for alternative methods for surgical treatment of uterine fibroids. Hormonal therapy remains the first-line treatment option for most patients. GnRH analogs (agonists and antagonists) modulate the pulsatile release of GnRH. This review summarizes the available literature concerning pharmacologic principles underlying the mechanism of action of GnRH and its analogs, as well as individual therapeutic applications to which these drugs have been applied.

Expert opinion

In many cases, it is possible to try to treat uterine fibroids pharmacologically. Both groups of GnRH analogs are used in therapy, agonists instead as a preparation for surgery, and antagonists as a drug for long-term use. It is essential to develop this path further and look for at least long-term-release systems or new methods of administering these drugs. It is also important from the patient’s perspective to search for possible drugs that may have an additive effect of decreasing side effects when combined with GnRH analogs.

1. Epidemiology

Uterine fibroids are the most common noncancerous tumors in women of childbearing age [Citation1]. In the United States, it is estimated that up to 80% of African American women and 70% of white women have uterine fibroids by the age of 50 [Citation2]. These lesions vary greatly in size, location, and clinical symptomatology, ranging from entirely asymptomatic to a combination of any of the following symptoms including heavy and prolonged menstrual bleeding, bulky symptoms, reproductive dysfunction, and pain related or not to their menstrual period, but this is just a part of them [Citation3].

Uterine fibroids can be managed by improving symptoms but are also influenced by the patient’s desire for future fertility, desire to retain the uterus, and the likelihood of achieving treatment goals [Citation4]. Hysterectomy is a definitive therapy for patients who have completed family planning. Hysteroscopy for submucosal fibroids, myomectomy with laparoscopy, or open abdominal incision are therapeutic options for females looking for uterine-sparing treatments because they want to get pregnant in the future. Other possibilities for treatment include targeted ultrasound surgery, uterine artery embolization [Citation5] combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, progestin-releasing intrauterine devices, tranexamic acid, and finally gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs – agonists and antagonists [Citation6].

2. GnRH axis and physiology

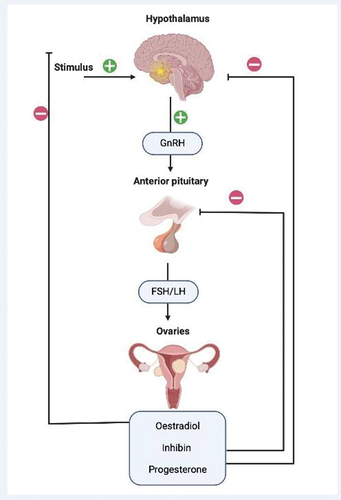

A noteworthy characteristic of uterine fibroids is their dependency on the ovarian hormones estrogen and progesterone affecting women in their reproductive years, therefore these tumors tend to shrink after menopause [Citation7]. The hypothalamus centrally regulates reproductive function through the GnRH hormone. This hormone is secreted in a pulsatile manner, which leads to the synthesis and secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) [Citation8]. Gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary gland is modulated by estradiol, inhibin, and progesterone which provide feedback for the regulation of the menstrual cycle. The pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus is essential for the maintenance of ovarian function and uterine fibroid growth [Citation6], for detailed presentation see .

3. GnRH analogs – agonists and antagonists

Many women are looking for alternative methods to any surgical treatment. They are particularly interested in pharmacotherapy, which can reduce clinical symptoms and the size of the uterine fibroid. This is due to the fact that at least some of the available drugs make it possible to permanently avoid surgery or possibly postpone it and make it carry a lower risk of complications, such as reducing bleeding [Citation9].

Complex signaling pathway alterations are crucial for uterine fibroid development. The topic of the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids focuses mainly on steroids and other hormones. Over the years, a few other medical options have been investigated for uterine fibroid treatment. These include antiestrogens, antiprogesterone, and androgen steroids [Citation10]. Antiestrogens, such as aromatase inhibitors, were ineffective in premenopausal patients. Antiprogesterones caused endometrial hyperplasia, and gestrinone, a medication with antiprogesterone and androgenic properties, led to undesirable side effects such as acne, hirsutism, and seborrhea [Citation11]. Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), specifically ulipristal acetate (UPA), gained widespread popularity and use after initial approval by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for use in uterine fibroid treatment. However, the reported severe liver impairments requiring liver transplants in some cases led to its Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejection for use in the United States [Citation12] and mandated restricted use by the EMA. Another drug – vilaprisan was also presented with severe issues in trials [Citation13]. For this reason, the search for the optimal drug was started again. It should still be reminded that according to available data short-term SPRM use treatment yielded lower uterine fibroid size reduction than GnRH agonist treatment in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids [Citation14]. Due to the termination of some studies, the complete results were unavailable, but GnRH analogs also presented more favorable than ulipristal acetate in terms of intraoperative blood loss, hemoglobin drop postoperatively, and suturing time of the first lesion [Citation15].

Our understanding of the hormone mediated pathway of uterine fibroid pathophysiology and the mechanics of the GnRH axis led to the use of GnRH analogs in the therapy [Citation16]. Analogs themselves are one of the longer known pharmacological methods for the treatment of uterine fibroids. These drugs modulate the pulsatile release of GnRH, thereby inhibiting the secretion of FSH and LH. GnRH analogs are built in very different ways, but what is essential is that they are structurally related to GnRH, e.g. in the case of goserelin and leuprorelin. At this point, there are two different groups of compounds of GnRH analogs – agonists and antagonists, and their nature of action is entirely different [Citation17,Citation18].

Although non-peptide oral GnRH antagonists were recently FDA-approved for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids, our early experience with GnRH analogs began with the agonists. These agonists were and continue to be used for treatment. The use of GnRH agonists produces menopausal-like effects, which may reduce the size and severity of symptoms associated with uterine fibroids. This effect is mainly due to changes in blood flow through the uterus [Citation19]. GnRH agonists result in an initial increase in estrogen and progesterone production. However, the continuous dosing of GnRH agonists, as opposed to the pulsatile release of GnRH from the pituitary gland, eventually leads to ovarian suppression and decreased estrogen and progesterone production [Citation20]. This ovarian suppression leads to a welcomed decrease in heavy menses and a reduction in the size and volume of fibroids. Unfortunately, the adverse effects experienced by patients, specifically climacteric symptoms of hot flushes and bone mineral density loss, make GnRH agonists unsuitable for long-term use [Citation20]. Furthermore, the almost immediate rebound in growth upon therapy cessation further limits the efficacy and use of this medication [Citation21].

4. Current trends in therapy

In clinical practice today, hormonal therapy remains the first-line treatment option for most patients with heavy menstrual bleeding. These hormones may be delivered in the form of oral contraceptives, progesterone-only pills, hormonal implants, intrauterine devices, and injectables [Citation22]. Oral gestagens are among the most commonly prescribed drugs for the short-term treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding in patients with uterine fibroids. Due to the fact that progesterone is involved in the pathogenesis of uterine fibroids, some researchers consider this approach ineffective, or even they might get the disease worse [Citation23]. While GnRH agonists and antagonists induce hypoestrogenic symptoms, according to reducing the size and volume of fibroids, acting as well on the gradual loss of bone mineral density and vasomotor symptoms, the implementation of hormone add-back therapy has the potential to enhance patient adherence and prolong the treatment duration but acting on the fibromas could lead to the worsening of symptoms. Employing progestogens for fibroid control can be likened to perpetually adding fuel to the fire, resulting in the futility of this treatment approach due to the implication of progesterone in the pathogenesis of this condition. On the other hand, data suggest that GnRH analogs are much more potent than gestagens (e.g. lynestrenol) because of their more intense antigonadotropic activity [Citation24].

Of these therapies, the levonorgestrel intrauterine system has an important clinical advantage owing to its minimal to no systemic effect and lack of impact on ovarian function. Interestingly, the phrase ‘it’s better to be lucky than good’ may be appropriate when considering the use of levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine system (IUS) in the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. It is important to note that this LNG primarily affects the endometrium, which is the lining of the uterus, rather than directly targeting the uterine fibroids. The LNG-IUS was introduced in 1990 and initially authorized for contraceptive purposes. However, during clinical trials, a reduction in menstrual blood loss was observed, leading to its approval for the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding of unknown cause). Fortunately, in clinical practice, similar improvements in bleeding patterns were observed in patients with structural causes of heavy periods, and many health-care providers adopted this approach [Citation25].

Most recently, the unfavorable balance of the adverse properties compared to the effectiveness of long-term GnRH agonist use has led to the development of oral non-peptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists = elagolix, relugolix, and linzagolix [Citation26]. These medications maintain therapeutic efficacy with a milder adverse effect profile than the GnRH agonists. They are also characterized by a dose-dependent effect and a quick onset of action with only partial suppression of circulating estrogens. Today, the antagonists are naturally on the rise due to very encouraging results.

5. GnRH agonists – dead or alive?

GnRH agonists work by activating GnRH receptors, which affect the secretion of gonadotropins. Examples of these agents are as follows: buserelin, deslorelin, goserelin, leuprorelin, and triptorelin. During the research, however, it turned out that the stimulating effect of lasts only at the beginning. They cause the ‘flare effect’ only initially, but quickly the opposite effect and the state of deep hypogonadism occur due to the internalization of receptors and inhibition of the pituitary-gonadal axis [Citation27]. The effect is most often maintained during subsequent doses; however, these drugs can only be used for a limited period of time, and unfortunately, as it was already mentioned most uterine fibroids regrow due to re-release of gonadotropins after discontinuation of these drugs. GnRH agonists are much more potent and have a longer half-life than human GnRH. They also slowly release themselves from its receptor [Citation28,Citation29]. Most of the adverse reactions experienced by women with GnRH agonists are related to sex steroid deficiency and include symptoms such as hot flushes, decreased libido, sexual dysfunction, vaginal atrophy, osteoporosis, and infertility. In addition, hypoestrogenism significantly contributes to bone loss. Therefore, long-term treatment with these drugs may lead to the development of osteoporosis [Citation30,Citation31]. Interestingly, some authors have found that specific analogs (e.g. buserelin) were effective in reducing uterine fibroids but have no significant effect on bone. However, they still advised that bone mass must be carefully monitored [Citation32]. Other authors published their opinion that the effect on bone-mineral density appears to be clinically unimportant for up to 6 months of treatment and is primarily reversible after the cessation of therapy [Citation33].

A significant proportion of agonists are administered using sustained-release systems. Most, such as goserelin, leuprorelin, or triptorelin, are used once a month in an indication such as uterine fibroids. When it comes to how to use goserelin, treatment usually begins in the first days of the menstrual cycle. 3.6 mg is given in one implant subcutaneously every 4 weeks for about 3–6 months before elective surgery. When used for up to 6 months, special attention should be paid, because there is a risk of reducing bone mineral saturation. In the case of triptorelin, treatment begins in the same way – in the first days of the cycle. 3.75 mg should be administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly every 4 weeks. For patients for whom surgery is planned, the treatment lasts for 3–6 months. For leuprorelin, the recommended dose is also 3.75 mg, given as a single subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. It is given once every 4 weeks for no more than 6 months. The treatment can be given before surgery to remove the fibroids. It can also be used to reduce symptoms in women who do not want invasive treatment.

However, there are also data that, for example, in the case of goserelin, such administration can also be replaced by a 3-month dosing (10.8 mg). According to an interesting study, a single, preoperative injection of goserelin acetate 10.8 mg in addition to orally administered iron was associated with improved hemoglobin levels in selected premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia due to uterine fibroids [Citation34]. For many patients, this is a much greater comfort, because it is possible to reduce some visits and, on the other hand, to improve compliance in treatment.

In the selection of agonist therapy (but also applies to the agonists described later), the time of initiation of therapy/period in the patient’s life is very important. In many cases, it is difficult or almost impossible to propose therapy with pills for several decades. A count of patients may be unwilling to undergo long-term treatment involving hormones and hormone analogs. Moreover, there is a lack of data regarding the long-term effects of agonists or antagonists on the body, especially after 10, 15, or 20 years. Consequently, it appears that the most suitable time to initiate these medications, excluding preoperative treatment, is during the perimenopausal phase. During this period, effective therapy should be provided for several months, followed by discontinuation to allow the menopausal transition to naturally manage some symptoms. For instance, menopause is expected to occur within a year after the therapy is stopped. This aspect of treatment with GnRH agonists (and antagonists) requires further assessment [Citation35].

It cannot be said absolutely that each of the drugs of this group works the same. For example, leuprorelin induces pituitary down regulation more rapidly than buserelin. There are also differences in how they cause symptoms, e.g. hypoestrogenic symptoms such as hot flashes were more severe in cases treated with leuprorelin than in those treated with buserelin [Citation36]. On the other hand, when we check available studies we can find that e.g. goserelin and leuprolide administered before hysterectomy for uterine fibroids have similar perioperative outcomes [Citation37]. Such features are not a disadvantage, but in our opinion an advantage, because a good clinician will be able to better individualize potential treatment and have more opportunities to achieve the effect he needs for his patient.

There are also fascinating data that the use of GnRH agonists can have a good effect on the reduction of growth factors and cytokines that cause the growth of uterine fibroids. As found in the very recent study, the use of goserelin therapy reduces serum levels of inflammatory cytokines and improves symptoms [Citation38]. Authors of this study proposed that serum levels of inflammatory cytokines might be considered as predictive biomarkers for uterine fibroid progression and therapeutic response during goserelin therapy which seems to be an interesting proposition, especially in a disease that can only be monitored through clinical examination and the patient’s history [Citation38]. Nevertheless, in some cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound examination could be needed. In this regard, an exciting growth factor seems to be, in particular, the tumor necrosis factor alpha [Citation39].

Of course, these are not all issues related to GnRH agonists and their clinical use. It can be summarized that it is known in the case of agonists that they are effective drugs, although not without disadvantages, in particular those related to hypoestrogenism. The problem may be pretty old research on these drugs. Over many years, the circle of interest of doctors has changed [Citation4]. As there was a time when SPRMs were very commonly used, now it seems oral GnRH antagonists are slowly becoming the therapy of primary choice. However, there is a group of doctors faithful to these drugs, and it seems that for many patients, they can lead to positive effects. Moreover, these drugs are very good and helpful in individualizing therapy.

At this point, the issue of side effects associated with the use of GnRH analogs should also be discussed. In gynecology, various methods of supportive therapy are used to avoid the side effects of these drugs. Keep in mind that this type of therapy is not detrimental to successful treatment with GnRH agonists, but it is effective in preventing bone mineral loss and reduces the adverse effects of hypoestrogenism [Citation40,Citation41].

6. GnRH antagonists – early years and reproductive medicine

The first long-term clinical studies were carried out with third-generation GnRH antagonists – ganirelix and cetrorelix. They were initially developed as an alternative for GnRH agonists to prevent premature ovulation in patients undergoing ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures. GnRH antagonists offer a number of advantages when compared with agonists – there is no need to start with the antagonist in the early follicular phase. The inhibition of gonadotropin release is quick and constant without a ‘flare-up’ effect, as they competitively block pituitary GnRH receptors [Citation42,Citation43]. Furthermore, the restoration of pituitary function after antagonist treatment is brisk in contrast to agonists, which creates an opportunity to trigger oocyte maturation with GnRH agonist instead of hCG, thus allowing to avoid ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) [Citation43–46] [Citation47]. The effectiveness and safety of GnRH antagonist protocols in comparison with long agonist protocol were assessed in several randomized trials. In a meta-analysis by Ludwig et al., which included studies comparing GnRH antagonists with agonists, it was demonstrated that there was a significant reduction in the number of oocytes in a GnRH antagonist-treated patients compared with an agonist group [Citation48]. The pregnancy rate was lower in individuals receiving ganirelix compared with the long agonist protocol, but no significant difference between cetrorelix and agonist groups was noted. Interestingly, the OHSS incidence was lower for cetrorelix, but not for ganirelix [Citation43,Citation48,Citation49]. There was no difference in pregnancy rates in cryopreservation cycles for freeze-thawed embryos for various doses of ganirelix applied in fresh cycles [Citation49]. Furthermore, there was no difference in pregnancy rate for frozen-thawed oocytes retrieved in cetrorelix cycles when compared with long protocol cycles [Citation50,Citation51]. These results lead to a conclusion that GnRH antagonists might alter endometrial receptivity, but they do not make a major impact on the oocytes and embryos [Citation46,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52]. To support this, in a meta-analysis by Kolibianakis et al., it was demonstrated that there was no significant difference between live birth rates in individuals treated with GnRH agonists or GnRH antagonists [Citation53].

Ganirelix is administered in multiple-dose protocols in subcutaneous injections [Citation42]. It is absorbed rapidly and extensively, has an excellent bioavailability, and leads to dose-dependent decline in serum LH and estradiol levels [Citation54,Citation55]. When compared with standard long protocol, ganirelix allows for shorter duration of the treatment and lower total amount of administered gonadotropins. As the number of retrieved oocytes is lower for antagonist protocol, the number of good-quality embryos remains similar in both agonist and antagonist groups. The ongoing pregnancy rates tend to be lower in the antagonist group [Citation56,Citation57] [Citation58]. The number of adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes seems to be similar for both agonist and antagonist protocols [Citation59].

Multiple- and single-dose protocols are available for cetrorelix, and both of them were shown to be at least as efficient as the long GnRH agonist protocol for pituitary suppression [Citation42]. Notably, the use of cetrorelix in IVF procedures results in very much similar live birth rates, a shorter time of treatment, as well as decreased total gonadotropin demand and lower incidence of OHSS, compared with long agonist regimens [Citation47].

7. Old GnRH antagonists efficacy in uterine fibroid therapy

The influence of the cited studies on researchers’ quest for developing a non-peptide form and the utilization of antagonist potency in the treatment of uterine fibroids remains uncertain. However, an exploration of the historical utilization of such antagonists in this context is undoubtedly warranted. It is already established that uterine fibroids contain receptors for estrogen, progesterone, as well as specific binding sites for GnRH [Citation60,Citation61]. The quick decrease in estrogen levels, which might be associated with a rapid diminishment in fibroid size, is in favor of GnRH antagonists over GnRH agonists [Citation62]. This supports adequate preparation for the surgery in terms of a fibroid shrinkage within only 2–3 weeks in comparison to GnRH agonists (where at least 4–8 weeks of therapy are required) along with diminishment or avoidance of side effects such as hot flushes or bone density loss or quick recovery from these adverse effects if they are already met [Citation62–65] [Citation66].

The administration of ganirelix in the treatment of uterine fibroids has not been established in clinical practice so far, however some attempts to implement this GnRH antagonist have been made. In preclinical studies, application of ganirelix to fibroid cells leads to apoptosis and diminished expression of the nuclear factor responsible for tumor growth, leading to the conclusion that local therapy may cause fibroid shrinkage [Citation67]. Furthermore, in a study by Flierman et al., the treatment of uterine fibroids with ganirelix resulted in a considerable reduction in its volume by 25–40% within only 3 weeks [Citation63].

Similar to ganirelix, cetrorelix is not an established in clinical practice drug for fibroid treatment, but a few investigations are showing that it may be potentially valuable. In a study by Felberbaum et al. in patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids treated with cetrorelix, a mean decrease in fibroid volume after 14 days of therapy was 31.3% assessed by transvaginal sonography [Citation66]. Fibroid cells are assumed to proliferate under estradiol stimulation, and for that reason impairment of gonadotropin release with GnRH antagonist might lead to fibroid shrinkage. Fibroid volume reduction with cetrorelix is dose dependent and proved to be most sufficient when accompanied by low estradiol plasma levels [Citation62]. Furthermore, the presence of receptors for GnRH in fibroid tissue has been confirmed [Citation67,Citation68]. Cetrorelix might exert its actions on uterine fibroid by inducing apoptosis in its cells [Citation62,Citation69]. Another possible mechanism of reduction of lesion size by cetrorelix might be their susceptibility to epidermal growth factor (EGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and impairment of the growth factors function when treated with the GnRH antagonists [Citation60,Citation70]. The GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate was demonstrated to act directly on fibroid cells [Citation71]. The direct impact on leiomyoma extracellular matrix (ECM) expression was demonstrated in one study [Citation71], however there are still insufficient evidence in regard to the influence of GhRH analogs on fibroid ECM.

These studies provide evidence supporting the potential suitability of GnRH antagonists as a therapeutic option for select patients. The aforementioned studies have demonstrated a marked efficacy of GnRH antagonists, particularly in reducing the volume and size of uterine fibroids, as well as alleviating associated symptoms. As our understanding of fibroids remains incomplete and ongoing drug development efforts are underway, it is conceivable that subcutaneous antagonists could be combined with other medications in the treatment of uterine fibroids, as potential synergistic effects may be discovered by future research endeavors.

8. New oral GnRH antagonists – new era in uterine fibroid therapy

The oral GnRH antagonists are a new option in the treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding associated with uterine fibroid (AUB-L). The FDA has recently approved two drugs: elagolix and relugolix [Citation72].

8.1. Elagolix

Elagolix is a novel, orally bioavailable, competitive non-peptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist [Citation73]. Elagolix is the most studied drug of its class in benign gynecological disease treatment. It has been approved by the FDA firstly for use in endometriosis in July 2018, and then in May 2020 for the treatment of uterine fibroids [Citation74,Citation75]. Its effectiveness in uterine fibroids has been confirmed in many clinical trials and meta-analyses [Citation76–81] [Citation82]. The clinical pharmacology of elagolix was extensively evaluated. Its pharmacokinetics are stable and not affected by any demographic differences, like for example race, nutrition, and geographical related differences [Citation83,Citation84]. It was approved for the treatment of heavy bleeding associated with uterine fibroids at a dose of 300 mg twice daily in combination with add-back therapy (estradiol (E2) 1 mg/norethindrone acetate (NETA) 0.5 mg [E2/NETA] once daily) [Citation85]. An add-back therapy is confirmed not to have clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interactions [Citation86]. It can be administered for up to 24 months, but there are several reports concerning the safety of a prolonged use [Citation72,Citation85]. There are also currently some interesting ongoing clinical trials in this area: concerning the long-term safety of the elagolix in uterine fibroids (NCT03271489), evaluating pregnancy outcomes in females treated with elagolix (NCT04464187) and comparing myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, and elagolix in the treatment of AUB-L. The results will be for sure of a great clinical value.

8.2. Relugolix

Relugolix has been approved by the FDA for use in uterine fibroids on May 2021 as a first once-daily treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids [Citation87]. It is administered orally and can be administered for up to 24 months, although a recent study has confirmed its safety during an administration prolonged to 52 weeks [Citation72,Citation88]. A conducted clinical trial confirmed its non-inferiority to monthly leuprorelin injections [Citation89]. The relugolix combination therapy (relugolix, estradiol, and norethindrone acetate) was confirmed to result in a significant reduction in menstrual bleeding with simultaneous bone mineral density preservation [Citation82,Citation90] [Citation91,Citation92]. The recommended dose is one tablet daily containing 40 mg relugolix, 1 mg estradiol (estradiol hemihydrate) 0.5 mg norethindrone acetate. The first tablet should be taken within 5 days of the start of menstruation. Its safety, toleration, and the life-quality improvement were confirmed in several studies [Citation82,Citation89,Citation90,Citation93] [Citation94,Citation95]. Moreover, some reports are claiming it improves uterine fibroid-associated pain [Citation93,Citation96]. Also, an attempt to use relugolix in the preoperative period before the hysterectomy showed similar results to the leuprorelin injection and a reduction in uterine volume [Citation97]. There are two ongoing clinical trials concerning this drug: evaluating the safety and contraceptive efficacy of relugolix in women who are at risk of pregnancy (NCT04756037) and comparing the use of relugolix following the myomectomy (which should delay the need for re-intervention after uterine sparing surgery) versus the routine standard of care (NCT05538689).

8.3. Linzagolix

It is a novel GnRH receptor antagonist, which was tried to be used in endometriosis, adenomyosis, and uterine fibroids. The drug is now awaiting FDA approval as the one and only GnRH receptor antagonist with flexible dosing options [Citation98]. It has a promising efficiency, safety, and toleration profile [Citation90,Citation99,Citation100]. The emphasis is on the need for a hormonal add-back therapy, especially at higher doses, to minimize the hypoestrogenic side effects [Citation99,Citation101]. However, a dose of 100 mg provides a unique option for the chronic treatment of women who cannot or do not want to take a hormonal add-back therapy.

The results regarding the efficacy of new-generation oral GnRH-antagonists, such as elagolix, relugolix, and linzagolix, are promising and offer potential prospect for the future therapy of uterine fibroids. However, these antagonists must be combined with hormonal add-back therapy to minimize the resultant hypoestrogenic side effects such as bone loss [Citation99].

Here we should cite a very recent systematic review from 2022 by Niaz et al. The authors of this review found that among oral GnRH antagonists, relugolix, elagolix, and linzagolix were first of all safe in patients with uterine fibroids. These drugs, alone and in combination with add-back, showed significantly better efficacy than placebo in improving bleeding, pain, volume of lesions, and quality of life in premenopausal patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids. However, authors still believe that more data from double-blind, clinical trials are needed to confirm these results and see long-term benefits [Citation90].

9. Conclusions

In many cases, it is possible and even necessary to try to treat uterine fibroids pharmacologically. Currently, we have better and better drugs that have a proven effect on uterine fibroids – among them, GnRH analogs – agonists and antagonists – come to the fore. Both groups of drugs are used in therapy, agonists instead as a preparation for surgery, and antagonists as a drug for long-term use. In the vast majority of patients, such treatment may result in the disappearance or reduction of symptoms or may facilitate surgery.

It is essential to develop this path further and look for at least long-term-release systems or new methods of administering these drugs. It is also important from the patient’s perspective to search for possible drugs that may have an additive effect of decreasing side effects when combined with GnRH analogs.

10. Expert opinion

The data shows that as of today, antagonists are becoming a viable option for the pharmacological treatment of uterine fibroids, which is good in our opinion – these drugs are effective, they are relatively safe, and with the use of add-back, they do not cause the patient’s discomfort during their use [Citation90]. What is very important, according to recent reports, is that there is also a form of the oral antagonist itself, which can be used without add-back, which also extends the offer of oral treatment for patients who cannot take e.g. estrogens. In this case, linzagolix seems to be a unique option. We are waiting for new research and other drugs that could also possibly be used in therapy without the need for add-back [Citation101].

Nowadays, we have an easily accessible route for intracavitary drug delivery, e.g. LNG-IUS. This system is a safe, effective, and acceptable form of contraception used by over millions of women worldwide. It also has a variety of benefits including treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis, and endometrial hyperplasia. It is true that this system is quite effective in stopping bleeding in the case of benign uterine diseases [Citation102] but due to the role of gestagens in the induction of the appearance and growth of uterine fibroids, it is not a system that can always be used and will help in myoma-related bleeding [Citation23].

With the lack of local treatments for the management of uterine fibroids, and all the various side effects associated with GnRH analogs systemic administration, it is surprising that formulations for local administration of these agents are still not available. We do not know when other forms, such as antagonist inserts or patches, will be available, but we know for sure that work is being carried out in this direction and a breakthrough has been made relatively recently in the case of ganirelix. In a recently published study an organotypic fibroid culture model was used to assess the activity of ganirelix. The authors obtained a ganirelix-sustained-release platform based on poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres. This form of local release of ganirelix induced cell death in cell culture. These extraordinary results suggest that local treatment with ganirelix microspheres can potentially shrink fibroids and thereby relieve patients' symptoms or delay risky surgery. In addition, this form of therapy would also avoid the adverse effects observed in patients receiving GnRH analogs systemically [Citation103]. That is why we believe that this is some sort of therapeutic methods for the future.

What other ideas could there be for the future related to analogs, how else can their effectiveness in the treatment of uterine fibroids be improved? At this point, the subject of drug synergisms should be introduced at least briefly – this is a situation where the use of two drugs has a cumulative effect. This effect has been used for many years in the case of, for example, hypertension. In the case of uterine fibroids, there are not many reports on synergies and there is still quite a bit of research on this topic. A rather interesting case of synergism discovered recently in the case of fibroids is the use of ulipristal acetate together with vitamin D – in the work of Ali et al. targeted cell cultures have shown that these two agents used together have a much stronger effect [Citation104]. In addition, similar observations were obtained on individual cases of patients [Citation105]. Further research prevented the withdrawal of this drug. However, this does not change the fact that the very use of synergism in the treatment of uterine fibroids has a future. The only question is what drugs can have such an effect and where to expect additivity. Of course, this should be done sequentially. We should begin with cell cultures then we should move on to animal models. Subsequently, a properly constructed trial (with a control group and blinding) should be conducted to determine the exact effect of a simultaneous administration of these agents, e.g. GnRH analog (agonist or antagonist) with an additional compound.

We might use some different agents exhibiting an antifibrosis effect, such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), for which a lot of data have recently been published recently [Citation106,Citation107]. In a controlled study by Porcaro et al., women with symptomatic uterine fibroids were treated with vitamin D together with EGCG and vitamin B6 for 4 months. The study found that total fibroid volume decreased by much higher than in controls where fibroids continued to grow. The authors concluded that such a combination might be a new form of non-hormonal treatment for women with uterine fibroid. Further studies in this regard, published in 2021 and 2022, also had very positive conclusions, and of course, complete data on such treatment are still to be explored. Other synergistic possibilities might be, e.g. widely used cabergoline (used for hyperprolactinemia), which also has a proven antifibrotic effect, found in randomized trials [Citation108]. An exciting place to conduct research is the effect of analogs on the reduction of the concentration of inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, which may affect the biological processes of fibroids and the symptoms associated with them [Citation108]. An example is, for example, goserelin, which, according to recently published data, significantly reduces the concentration of such factors [Citation38]. It is possible, for example, to combine analogs with drugs from the group of anti-inflammatory drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, to reduce some of the symptoms dependent on them, at the moment there is no answer to this, but it seems worth investigating [Citation39].

A particular type of synergism is the use of GnRH analogs for other therapies, e.g. using physical methods. This is no longer a fully pharmacological effect in itself, but a combined physico-pharmacological effect, but it is still worth considering in terms of increasing the effectiveness of treatment. Such an example may be, for example, the use of thermoablation, where the use of GnRH agonist therapy before MRI – guided focused ultrasound improves the thermoablative treatment effect [Citation109]. As we know, the treatment of fibroids should be comprehensive, and the optimal choice of a treatment method should fit a patient’s specific life situation or expectancies. These days great importance is attached to the development of minimally invasive procedures, including minimally invasive radiological procedures [Citation110]. This also shows a very important place for treatment with GnRH analogs, if it is already known that agonists work in this regard, then perhaps it is time for research on antagonists.

Article highlights

Avoiding surgery in some cases is possible.

In many cases, pharmacological treatment of uterine fibroids could be enough.

GnRH analogs seem to be the one of the most effective in uterine fibroid treatment.

It is essential to search for possible therapies that could decrease side effects when combined with GnRH analogs.

Declaration of interest

O. S. Madueke-Laveaux declares doing consulting work with Myovant Sciences outside of the current work. A. Al-Hendy declares receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Bayer, Myovant, Novartis, ObsEva, and Pfizer, outside of the current work.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, et al. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy. 2017;124(10):1501–1512. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14640

- Giuliani E, As-Sanie S, Marsh EE. Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149(1):3–9. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13102

- Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino WH, et al. Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1):16043. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.43

- Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(6):665–686. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw023

- Ciebiera M, Łoziński T. The role of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound in fertility-sparing treatment of uterine fibroids-current perspectives. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1034. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1034

- Ortmann O, Weiss JM, Diedrich K. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH agonists: mechanisms of action. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;5:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(11)60210-1

- Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, et al. Comprehensive review of uterine fibroids: developmental origin, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(4):678–719. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnab039

- Marques P, Skorupskaite K, Rozario KS, et al. Physiology of GnRH and gonadotropin secretion. [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc; 2000: Endotext; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279070/ .

- Farris M, Bastianelli C, Rosato E, et al. Uterine fibroids: an update on current and emerging medical treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:157–178. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S147318

- Coutinho EM, Boulanger GA, Goncalves MT. Regression of uterine leiomyomas after treatment with gestrinone, an antiestrogen, antiprogesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155(4):761–767. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(86)80016-3

- Vollenhoven BJ, Lawrence AS, Healy DL. Uterine fibroids: A clinical review. British J Obstet And Cynaecology. 1990;97(4):285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb01804.x

- Stulberg DM. Ulipristal acetate works for fibroids, but its approval in the United States is threatened by safety concerns with long-term use. Evidence-Based Practice; 2020.

- Ciebiera M, Vitale SG, Ferrero S, et al. Vilaprisan, a new selective progesterone receptor modulator in uterine fibroid pharmacotherapy-will it really be a breakthrough? Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(3):300–309. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200127092208

- Lee MJ, Yun BS, Seong SJ, et al. Uterine fibroid shrinkage after short-term use of selective progesterone receptor modulator or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(1):69. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.1.69

- de Milliano I, Huirne JAF, Thurkow AL, et al. Ulipristal acetate vs gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists prior to laparoscopic myomectomy (MYOMEX trial): Short-term results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(1):89–98. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13713

- Madueke-Laveaux OS, Ciebiera M, Al-Hendy A, GnRH analogs for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. F&S Reports, 2022.

- Golan A. GnRH analogues in the treatment of uterine fibroids. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(Suppl 3):33–41. doi:10.1093/humrep/11.suppl_3.33

- Lewis TD, Malik M, Britten J, et al. A comprehensive review of the Pharmacologic management of uterine leiomyoma. Bio Med Res Int. 2018;2018:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2018/2414609

- Moroni RM, Martins WP, Ferriani RA, et al. Add-back therapy with GnRH analogues for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(3):Cd010854. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010854.pub2

- Schally AV, Comaru-Schally AM. Mode of action of LHRH analogs. 6th ed. Hamilton, ON: Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine; 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK12517/

- Sinai Talaulikar V, Belli AM, Manyonda I. GnRH agonists: do they have a place in the modern management of fibroid disease? J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(5):506–510. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0206-0

- Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011

- Donnez J. Uterine fibroids and progestogen treatment: lack of evidence of its efficacy: a review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3948. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123948

- Regidor PA, Regidor M, Schmidt M, et al. Prospective randomized study comparing the GnRH-agonist leuprorelin acetate and the gestagen lynestrenol in the treatment of severe endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2001;15(3):202–209. doi: 10.1080/gye.15.3.202.209

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kubba A, Caetano C, et al. Thirty years of mirena: a story of innovation and change in women’s healthcare. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(4):614–618. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14110

- Evangelisti G, Barra F, Perrone U, et al. Comparing the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic qualities of current and future therapies for uterine fibroids. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2022;18(7–8):441–457. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2022.2113381

- Ortmann O, Weiss JM, Diedrich K. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH agonists: mechanisms of action. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;5(Suppl 1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(11)60210-1

- Hodgson R, Bhave Chittawar P, Farquhar C. GnRH agonists for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(10). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012846

- Palomba S, Falbo A, Russo T, et al. GnRH analogs for the treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Gynecol Surg. 2005;2(1):7–13. doi: 10.1007/s10397-004-0078-0

- Magon N. Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists: expanding vistas. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2011;15(4):261–267. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85575

- Wang P-H, Lee WL, Cheng MH, et al. Use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist to manage perimenopausal women with symptomatic uterine myomas. Taiwanese J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2009;48(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60273-4

- Bianchi G, Costantini S, Anserini P, et al. Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on uterine fibroids and bone density. Maturitas. 1989;11(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(89)90209-0

- Miller RM, Frank RA. Zoladex (goserelin) in the treatment of benign gynaecological disorders: an overview of safety and efficacy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(Suppl 7):37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13539.x

- Muneyyirci-Delale O, Richard-Davis G, Morris T, et al. Goserelin acetate 10.8 mg plus iron versus iron monotherapy prior to surgery in premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia due to uterine leiomyomas: results from a phase III, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2007;29(8):1682–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.024

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Baglioni A, et al. Intranasal buserelin versus surgery in the treatment of uterine leiomyomata: long-term follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;38(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90207-2

- Takeuchi H, Kobori H, Kikuchi I, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing endocrinological and clinical effects of two types of GnRH agonists in cases of uterine leiomyomas or endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000;26(5):325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2000.tb01334.x

- Lim SS, Sockalingam JK, Tan PC. Goserelin versus leuprolide before hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101(2):178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.10.020

- Mohammed NH, Al-Taie A, Albasry Z. Evaluation of goserelin effectiveness based on assessment of inflammatory cytokines and symptoms in uterine leiomyoma. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(3):931–937. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01030-3

- Ciebiera M, Włodarczyk M, Zgliczyńska M, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor α in the biology of uterine fibroids and the related symptoms. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3869. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123869

- Schriock ED. GnRH agonists. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1989;32(3):550–563. doi:10.1097/00003081-198909000-00019

- Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Clinical a pnd Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. LiverTox, 2012.

- Howles CM. The place of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists in reproductive medicine. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;4(Suppl 3):64–71. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(12)60120-5

- Dal Prato L, Borini A. Use of antagonists in ovarian stimulation protocols. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10(3):330–338. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61792-0

- Maggi R, Cariboni AM, Marelli MM, et al. GnRH and GnRH receptors in the pathophysiology of the human female reproductive system. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(3):358–381. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv059

- Engmann L, DiLuigi A, Schmidt D, et al. The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist to induce oocyte maturation after cotreatment with GnRH antagonist in high-risk patients undergoing in vitro fertilization prevents the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a prospective randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.002

- Olivennes F. The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist in ovarian stimulation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(1):12–22. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000197520.53682.32

- Tur-Kaspa I, Ezcurra D. GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix, for pituitary suppression in modern, patient-friendly assisted reproductive technology. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5(10):1323–1336. doi: 10.1517/17425250903279969

- Ludwig M, Katalinic A, Diedrich K. Use of GnRH antagonists in ovarian stimulation for assisted reproductive technologies compared to the long protocol. Meta-Analysis Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;265(4):175–182. doi: 10.1007/s00404-001-0267-2

- Al-Inany HG, Youssef MA, Aboulghar M, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;5:Cd001750.

- Seelig AS, Al-Hasani S, Katalinic A, et al. Comparison of cryopreservation outcome with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists in the collecting cycle. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(3):472–475. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)03008-4

- Nikolettos N, Al-Hasani S, Felberbaum R, et al. Comparison of cryopreservation outcome with human pronuclear stage oocytes obtained by the GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix, and GnRH agonists. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;93(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00294-8

- Vlahos NF, Bankowski BJ, Zacur HA, et al. An oocyte donation protocol using the GnRH antagonist ganirelix acetate, does not compromise embryo quality and is associated with high pregnancy rates. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;272(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-005-0726-2

- Kolibianakis EM, Collins J, Tarlatzis BC, et al. Among patients treated for IVF with gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues, is the probability of live birth dependent on the type of analogue used? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):651–671. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml038

- Gillies PS, Faulds D, Barman BJA, et al. Ganirelix. Ganirelix Drugs. 2000;59(1):107–111. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059010-00007

- Oberyé JJ, Mannaerts BM, Kleijn HJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of ganirelix (Antagon/Orgalutran). Part I. Absolute bioavailability of 0.25 mg of ganirelix after a single subcutaneous injection in healthy female volunteers. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(6):1001–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00413-6

- Borm G, Mannaerts B. Treatment with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist ganirelix in women undergoing ovarian stimulation with recombinant follicle stimulating hormone is effective, safe and convenient: results of a controlled, randomized, multicentre trial. The Eur Orgalutran Study Group Hum Reprod. 2000;15(7):1490–1498. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.7.1490

- European and Middle East Orgalutran Study Group. Comparable clinical outcome using the GnRH antagonist ganirelix or a long protocol of the GnRH agonist triptorelin for the prevention of premature LH surges in women undergoing ovarian stimulation. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(4):644–651. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.4.644

- Fluker M, Grifo J, Leader A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ganirelix acetate versus leuprolide acetate in women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01638-1

- Olivennes F, Mannaerts B, Struijs M, et al. Perinatal outcome of pregnancy after GnRH antagonist (ganirelix) treatment during ovarian stimulation for conventional IVF or ICSI: a preliminary report. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(8):1588–1591. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1588

- Rein MS, Friedman AJ, Stuart JM, et al. Fibroid and myometrial steroid receptors in women treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(6):1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)53578-X

- Wiznitzer A, Marbach M, Hazum E, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone specific binding sites in uterine leiomyomata. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;152(3):1326–1331. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(88)80430-3

- Engel JB, Audebert A, Frydman R, et al. Presurgical short term treatment of uterine fibroids with different doses of cetrorelix acetate: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134(2):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.018

- Flierman PA, Oberyé JJ, van der Hulst VP, et al. Rapid reduction of leiomyoma volume during treatment with the GnRH antagonist ganirelix. BJOG. 2005;112(5):638–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00504.x

- Matta WH, Shaw RW, Hesp R, et al. Hypogonadism induced by luteinising hormone releasing hormone agonist analogues: effects on bone density in premenopausal women. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294(6586):1523–1524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6586.1523

- Coddington CC, Collins RL, Shawker TH, et al. Long-acting gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone analog used to treat uteri. Fertil Steril. 1986;45(5):624–629. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49332-5

- Felberbaum RE, Germer U, Ludwig M, et al. Treatment of uterine fibroids with a slow-release formulation of the gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist cetrorelix. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1660–1668. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1660

- Chegini N, Rong H, Dou Q, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH receptor gene expression in human myometrium and leiomyomata and the direct action of GnRH analogs on myometrial smooth muscle cells and interaction with ovarian steroids in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3215–3221. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.9.3215

- Parker JD, Malik M, Catherino WH. Human myometrium and leiomyomas express gonadotropin-releasing hormone 2 and gonadotropin-releasing hormone 2 receptor. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.098

- Kwon JY, Park KH, Park YN, et al. Effect of cetrorelix acetate on apoptosis and apoptosis regulatory factors in cultured uterine leiomyoma cells. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1526–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.06.022

- Sadow TF, Rubin RT. Effects of hypothalamic peptides on the aging brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(4):293–314. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(92)90036-7

- Chegini N, Ma C, Tang XM, et al. Effects of GnRH analogues, ‘add-back’ steroid therapy, antiestrogen and antiprogestins on leiomyoma and myometrial smooth muscle cell growth and transforming growth factor-beta expression. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8(12):1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.12.1071

- Wright D, Kim JW, Lindsay H, et al. A review of GnRH antagonists as treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding-leiomyoma (AUB-L) and their influence on the readiness of service members. Mil Med; 2022.Mar 28:usac078. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usac078. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35348746.

- Lamb YN. Elagolix: First Global approval. Drugs. 2018;78(14):1501–1508. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0977-4

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). Elagolix. Elagolix, 2019. [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525496/

- Lamb YN. Correction to: elagolix: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78(17):1855–1855. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-1014-3

- Archer DF, Stewart EA, Jain RI, et al. Elagolix for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids: results from a phase 2a proof-of-concept study. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(1):152–160.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.006

- Carr BR, Stewart EA, Archer DF, et al. Elagolix alone or with add-back therapy in women with heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1252–1264. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002933

- Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):328–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904351

- Simon JA, Al-Hendy A, Archer DF, et al. Elagolix treatment for up to 12 months in women with heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine leiomyomas. Obstet & Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1313–1326. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003869

- Al-Hendy A, Bradley L, Owens CD, et al. Predictors of response for elagolix with add-back therapy in women with heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(1):.e72.1–.e72.50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.032

- Stewart EA, Archer DF, Owens CD, et al. Reduction of heavy menstrual bleeding in women not designated as responders to elagolix plus add back therapy for uterine fibroids. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2022;31(5):698–705. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2021.0152

- Telek SB, Gurbuz Z, Kalafat E, et al. Oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists in the treatment of uterine myomas: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of efficacy parameters and adverse effects. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(5):613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.12.011

- Beck D, Winzenborg I, Liu M, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of elagolix in combination with Low-dose estradiol/norethindrone acetate in women with uterine fibroids. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2022;61(4):577–587. doi: 10.1007/s40262-021-01096-w

- Shebley M, Polepally AR, Nader A, et al. Clinical Pharmacology of elagolix: an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone Receptor antagonist for endometriosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2020;59(3):297–309. doi: 10.1007/s40262-019-00840-7

- Beck D, Winzenborg I, Gao W, et al. Interdisciplinary model-informed drug development for extending duration of elagolix treatment in patients with uterine fibroids. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(12):5257–5268. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15440

- Nader A, Mostafa NM, Ali F, et al. Drug-drug interaction studies of elagolix with oral and transdermal low-dose hormonal add-back therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(1):133–143. doi: 10.1007/s40262-020-00921-y

- Rocca ML, Palumbo AR, Lico D, et al. Relugolix for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(14):1667–1674. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1787988

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, 3rd. et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(6):920–930. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004988

- Osuga Y, Enya K, Kudou K, et al. Oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist relugolix compared with leuprorelin injections for uterine leiomyomas: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):423–433. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003141

- Niaz R, Saeed M, Khan H, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral GnRh antagonists in patients with uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44(12):1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2022.10.012

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Treatment of uterine fibroid symptoms with relugolix combination therapy. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):630–642. 3rd. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008283

- Syed YY. Relugolix/Estradiol/Norethisterone (norethindrone) acetate: A review in symptomatic uterine fibroids. Drugs. 2022;82(15):1549–1556. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01790-4

- Osuga Y, Enya K, Kudou K, et al. Relugolix, a novel oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, in the treatment of pain symptoms associated with uterine fibroids: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study in Japanese women. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(5):922–9 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.013

- Hoshiai H, Seki Y, Kusumoto T, et al. Relugolix for oral treatment of uterine leiomyomas: a dose-finding, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Women's Health. 2021;21(1):375. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01475-2

- Stewart EA, Lukes AS, Venturella R, et al. Relugolix combination therapy for uterine leiomyoma–associated pain in the LIBERTY randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(6):1070–1081. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004787

- Stewart EA, Lukes AS, Venturella R, et al. Relugolix combination therapy for uterine leiomyoma-associated pain in the LIBERTY randomized trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(6):1070–1081. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004787

- Takeda A. Short-term administration of oral relugolix before single-port laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy for symptomatic uterine myomas: a retrospective comparative study with leuprorelin injection. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022;48(7):1921–1929. doi:10.1111/jog.15269

- Keam SJ. Linzagolix: First approval. Drugs. 2022;82(12):1317–1325. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01753-9

- Ali M, Raslan M, Ciebiera M, et al. Current approaches to overcome the side effects of GnRH analogs in the treatment of patients with uterine fibroids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022;21(4):477–486. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.1989409

- Rovelli RJ, Cieri-Hutcherson NE, Hutcherson TC Systematic review of oral pharmacotherapeutic options for the management of uterine fibroids. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;62(3):674–682.e5. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2022.02.004

- Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):896–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01475-1

- Beatty MN. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: Safety, efficacy and patient acceptability. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5(3):561–574. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S5624

- Salas A, García-García P, Díaz-Rodríguez P, et al. New local ganirelix sustained release therapy for uterine leiomyoma. Evaluation in a preclinical organ model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113909. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113909

- Ali M, Laknaur A, Shaheen SM, et al. Vitamin D synergizes the antiproliferative, apoptotic, antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects of ulipristal acetate against human uterine fibroids. Fertil Sterility. 2017;108(3):e66. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.208

- Ciebiera M, Męczekalski B, Łukaszuk K, et al. Potential synergism between ulipristal acetate and vitamin D3 in uterine fibroid pharmacotherapy - 2 case studies. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(6):473–477. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1550062

- Porcaro G, Santamaria A, Giordano D, et al. Vitamin D plus epigallocatechin gallate: a novel promising approach for uterine myomas. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(6):3344–3351. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20702

- Miriello D, Galanti F, Cignini P, et al. Uterine fibroids treatment: do we have new valid alternative? Experiencing the combination of vitamin D plus epigallocatechin gallate in childbearing age affected women. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(7):2843–2851. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202104_25537

- Vahdat M, Kashanian M, Ghaziani N, et al. Evaluation of the effects of cabergoline (Dostinex) on women with symptomatic myomatous uterus: a randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;206:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.08.013

- Smart OC, Hindley JT, Regan L, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and magnetic-resonance-guided ultrasound surgery for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000222381.94325.4f

- Łoziński T, Filipowska J, Gurynowicz G, et al. The effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound guided by magnetic resonance therapy on obstetrical outcomes in patients with uterine fibroids – experiences from the main Polish center and a review of current data. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):581–589. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2019.1616117