1. Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated reactions to inhaled allergens in the nasal mucosa, resulting in nasal itching, rhinorrhea, sneezing, and obstruction. As one of the most common chronic conditions globally, AR affects up to 50% of the population worldwide [Citation1]. Due to the potential effects of air pollution and climate change, the incidence of AR has shown a remarkable increasing trend [Citation2,Citation3]. AR often co-occurs with asthma and conjunctivitis and causes a major burden on quality of life especially in individuals with severe AR and a greater frequency of symptoms [Citation4,Citation5], exerting an underestimated effect on their work productivity [Citation6].

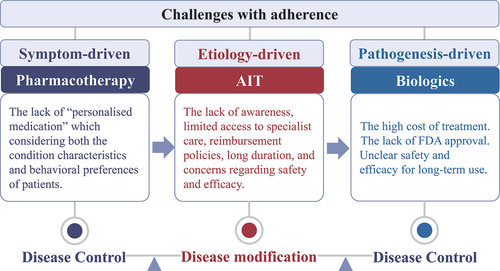

Clinical practice guidelines for AR developed over the past two decades have considerably improved the care of patients with AR. The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma [ARIA] initiative was established in 1999 [Citation7] and underwent multiple revisions; the latest guidelines were released in 2020 [Citation8]. AR management includes allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy, allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), and patient education. Among these, the challenges of adherence to pharmacotherapy and the impact on care pathways are highly concerning.

2. Symptom control driven pharmacotherapy

The aim of pharmacotherapy for patients with AR is to control the disease. Oral or intranasal H1-antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids (INCS), and leukotriene receptor antagonists, either alone or in combination, are recommended conditionally [Citation9]. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy significantly affects the management of AR. However, it has also recently been revealed that guidelines recommending standard therapies are not sufficiently followed because they do not satisfy patients’ needs and likely are not a reflection of reality [Citation8]. In this respect, increasing evidence suggests that adherence to treatment is low in patients with AR. An early study investigating patients with AR in UK general practice reported that only 27% of patients regularly used standard medications involving both oral antihistamines and INCS [Citation10]. A recent survey conducted in 13 metropolitan cities in China reported that 37.7% of patients with AR seldom accepted the regular medication described by the ARIA recommendations, and 46.6% started to use the prescribed medicine only when the symptoms had already presented [Citation11]. Recently, the MASK Study, which assessed the adherence to treatment in patients with AR using the Allergy Diary App in the real‐life context, reported that only 11.3% of patients with AR fully adhered to their medication prescriptions and the relative time intervals (medication possession ratio ≥ 70% and proportion of days covered ≤ 1.25) [Citation12].

Indeed, non-adherence to medications is a major obstacle to the effective delivery of healthcare globally. Coincidentally, ‘patient education’ is an important component of AR management systems recommended by the guidelines. Medication adherence is defined as the active, cooperative, and voluntary participation of the patient according to recommendations from a healthcare provider. This multifactorial behavior involves three critical steps: initiation, implementation, and discontinuation [Citation13]. There is a severe disconnection between physicians’ prescriptions and patients’ treatment behaviors in some cases. Doctors typically prescribe according to guidelines without considering the actual efficacy of the medication or the allergen exposure status toward the patient. In contrast, most patients with AR use their medications on demand or self-medicate, but do not follow prescriptions especially when their symptoms are not controlled [Citation14,Citation15]. Therefore, it has been proposed that the selection of pharmacotherapy for patients with AR should not only consider the compatibility between the mechanism of action, efficacy, and speed at which the treatment works, and the characteristics of a patient’s condition (prominent symptoms, symptom severity, multimorbidity, effect on sleep and work productivity, and historic response to treatment), but also patients’ preferences and self-management strategies [Citation8]. In this respect, many current studies revolve around fulfilling the unmet need of ‘personalised medication’ which can also be achieved through adaptive trial design in the future. In fact, the GRADE approach has already taken these issues into consideration when developing clinical practice guidelines. The GRADE approach is a grading system that rates the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations in guidelines, which emphasizes the need for guidelines to grade the quality of available evidence, weigh the pros and cons of interventions, and for clinicians to explicitly consider patients’ values and preferences in their decision making [Citation16–18]. Moreover, next-generation guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of AR have been developed using both existing GRADE-based guidelines for the disease and real-world evidence (REW) in terms of observational research with real-world data to inform clinical practice [Citation8]. ARIA has evolved care pathways suited to real-life using mobile technology [Citation8].

3. Disease modification therapy

Compared to the effect of pharmacotherapy on symptom relief, AIT is currently the only curative intervention that can potentially modify the immune system of individuals with AR, thus affecting the natural course of allergic diseases [Citation19]. More than 100 years have passed since AIT use was first reported in patients with hay fever by Noon in 1911 [Citation20]. Subsequently, clinical practice of AIT has shown remarkable progress, and its long-term effects, efficacy in reducing symptoms, and safety have been investigated and confirmed in numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses. Moreover, AIT has recently been proposed to play a key role in preventing comorbidities of allergic diseases [Citation21]. Currently, two routinely applied methods of AIT are sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) and subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), and it has been shown that SCIT has a higher adherence rate than SLIT [Citation22,Citation23], which because of SCIT requires scheduled visits to the hospital for injections under the supervision of a healthcare professional, whereas SLIT relies on self-administration of regular usage. But the overall adherence rate for AIT is not high [Citation22] and is estimated as less than 10% worldwide in patients with AR or asthma because of a lack of awareness, limited access to specialist care, reimbursement policies, long duration, and concerns regarding safety and efficacy. Safer and more effective AIT strategies are continuously being developed through new allergen preparations, adjuvants, and alternative routes of administration. Better selection of responders based on an endotype-driven strategy to increase efficacy was also addressed.

4. Pathogenesis-oriented biologics

Evidence-based guidelines have improved the knowledge of AR, but many patients remain inadequately controlled. Among the patients who had received the standard-of-care (SoC), only 32.7% felt that their symptoms were completely controlled [Citation11]. Thus, a medication with a different mode of action from the current SoC is expected to be more effective and easier for patients to follow and may spare patients with uncontrolled AR from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. A targeted pathogenesis-driven, rather than symptom-driven therapeutic concept is key to the success of new treatment options. Type 2 inflammation is a key factor in the pathogenesis of AR, thus biologics that directly target fundamental type 2 inflammation may shed new light on providing an effective and well-tolerated treatment. Several placebo‐controlled studies and meta-analyses have shown that the application of omalizumab (an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody) can improve nasal and ocular symptoms and quality of life (QoL), and reduce the need for rescue medications in patients with both seasonal AR (SAR) and perennial AR (PAR) [Citation24–27]. In addition, dupilumab (an anti-IL4 biological agent) was only reported to be effective in improving AR-associated nasal symptoms and QoL in a pivotal phase 2b study through post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of patients with asthma and comorbid PAR [Citation28]. Recently, stapokibart (an anti-IL4 biological agent), was shown to significantly reduce daily reflective total nasal symptoms in a subgroup of patients with SAR with a blood eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells·μL−1 in pollen phase [Citation29]. Besides, mainly considering reduce adverse events, biologics was also used as supplementary treatments in combination with AIT. SCIT with add-on dupilumab for hay fever patients was reported to significantly reduced the epinephrine rescue treatment rate [Citation30]. Omalizumab pretreatment was also exhibited to reduce acute reactions after rush immunotherapy for SAR [Citation31]. In treating refractory AR for which optimal pharmacological treatment has failed, biologics that target the AR endotype at the pathogenesis level are promising. Current limitations in the widespread use of biologics for the treatment of AR are related to the high cost of treatment and the lack of FDA approval [Citation4]. Moreover, the safety and efficacy of long-term use must still be evaluated. In the future, more patients with uncontrolled AR will benefit from biologics through more cost-effective design strategies and targets in patients with AR.

5. Expert opinion

The GRADE-based guideline integrating RWE studies in the management of AR are the main evaluation of the recommendations proposed by the latest ARIA. Maintenance treatment for AR is generally based on the regular application of pharmacotherapy which exhibits relatively low adherence. As an effective approach for reducing symptoms and potentially modifying the underlying course of allergy, AIT remains underused owing to a lack of awareness, high cost, long duration, safety concerns, and the heterogeneity of effectiveness. Biologics targeting type 2 inflammation-driven AR are promising options for treating uncontrolled AR that has failed optimal pharmacological treatment. In the future, it is necessary to fully consider the phenotypic and endotypic characteristics and behavioral preferences of the patients and develop comprehensive care pathways that combine pharmacotherapy, AIT, and biologics that are appropriate for daily life, realizing the dual goals of disease control and modification ().

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bousquet PJ, Leynaert B, Neukirch F, et al. Geographical distribution of atopic rhinitis in the European community respiratory health survey I. Allergy. 2008;63(10):1301–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01824.x

- Pacheco SE, Guidos-Fogelbach G, Annesi-Maesano I, et al. Climate change and global issues in allergy and immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(6):1366–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.10.011

- D’Amato G, Chong-Neto HJ, Monge Ortega OP, et al. The effects of climate change on respiratory allergy and asthma induced by pollen and mold allergens. Allergy. 2020;75(9):2219–2228. doi: 10.1111/all.14476

- Wise SK, Damask C, Roland LT, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: allergic rhinitis - 2023. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023;13(4):293–859. doi: 10.1002/alr.23090

- Colás C, Brosa M, Antón E, et al. Estimate of the total costs of allergic rhinitis in specialized care based on real-world data: the FERIN study. Allergy. 2017;72(6):959–966. doi: 10.1111/all.13099

- Vandenplas O, Vinnikov D, Blanc PD, et al. Impact of rhinitis on work productivity: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1274–1286.e1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.09.002

- Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891

- Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Togias A, et al. Next-generation allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):70–80. e73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.049

- Brożek JL, Bousquet J, Agache I, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines-2016 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):950–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.050

- White P, Smith H, Baker N, et al. Symptom control in patients with hay fever in UK general practice: how well are we doing and is there a need for allergen immunotherapy? Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(3):266–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00237.x

- Zheng M, Wang X, Wang M, et al. Clinical characteristics of allergic rhinitis patients in 13 metropolitan cities of China. Allergy. 2021;76(2):577–581. doi: 10.1111/all.14561

- Menditto E, Costa E, Midão L, et al. Adherence to treatment in allergic rhinitis using mobile technology. The mask study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(4):442–460. doi: 10.1111/cea.13333

- Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x

- Bousquet J, Arnavielhe S, Bedbrook A, et al. MASK 2017: ARIA digitally-enabled, integrated, person-centred care for rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity using real-world-evidence. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13601-018-0227-6

- Bousquet J, Anto JM, Annesi-Maesano I, et al. POLLAR: impact of air POLLution on asthma and rhinitis; a European institute of innovation and technology health (EIT Health) project. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13601-018-0221-z

- Brozek JL, Akl EA, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines. Part 1 of 3. An overview of the GRADE approach and grading quality of evidence about interventions. Allergy. 2009;64(5):669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01973.x

- Brozek JL, Akl EA, Jaeschke R, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: part 2 of 3. The GRADE approach to grading quality of evidence about diagnostic tests and strategies. Allergy. 2009;64(8):1109–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02083.x

- Brozek JL, Akl EA, Compalati E, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines part 3 of 3. The GRADE approach to developing recommendations. Allergy. 2011;66(5):588–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02530.x

- Akkoc T, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Update in the mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotheraphy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3(1):11–20. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.1.11

- Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against Hay Fever. Lancet. 1911;177(4580):1572–1573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)78276-6

- Halken S, Larenas-Linnemann D, Roberts G, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: prevention of allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28(8):728–745. doi: 10.1111/pai.12807

- Pfaar O, Richter H, Sager A, et al. Persistence in allergen immunotherapy: a longitudinal, prescription data-based real-world analysis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2023;13(5):e12245. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12245

- Kiel MA, Röder E, Gerth van Wijk R, et al. Real-life compliance and persistence among users of subcutaneous and sublingual allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):353–60. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.013

- Casale TB, Condemi J, LaForce C, et al. Effect of omalizumab on symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(23):2956–2967. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2956

- Chervinsky P, Casale T, Townley R, et al. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in the treatment of adults and adolescents with perennial allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(2):160–167. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62171-0

- Zhang Y, Xi L, Gao Y, et al. Omalizumab is effective in the preseasonal treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12(1):e12094. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12094

- Okubo K, Okano M, Sato N, et al. Add-on omalizumab for inadequately controlled severe pollinosis despite standard-of-care: a randomized study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(9):3130–3140.e3132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.068

- Weinstein SF, Katial R, Jayawardena S, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in perennial allergic rhinitis and comorbid asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):171–177.e171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.051

- Zhang Y, Yan B, Zhu Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of stapokibart (CM310) in uncontrolled seasonal allergic rhinitis (MERAK): an investigator-initiated, placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Feb 6;69:102467. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102467

- Corren J, Saini SS, Gagnon R, et al. Short-term subcutaneous allergy immunotherapy and dupilumab are well tolerated in allergic rhinitis: a randomized trial. J Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:1045–1063. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S318892

- Casale TB, Busse WW, Kline JN, et al. Omalizumab pretreatment decreases acute reactions after rush immunotherapy for ragweed-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(1):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.09.036