ABSTRACT

Background

In England, drug use in young people increased significantly between 2014 and 2017. This upward trend continues despite implementation of drug use policies to reduce supply, possession and manufacture of illicit drugs. Taking the view that drug use is a learnt behaviour, the purpose of this paper is to evaluate whether social learning (SL) factors explain drug use in English adolescents across: a) nine regions b) by age (11 to 15 years) and c) by gender using the Social Structure Social Learning (SSSL) theory as a framework. This study addresses a gap in the literature on English adolescent students by identifying the strongest SL pathway to drug use (imitation, parental reinforcement, attitudes, peer association).

Methods

Cumulative mediation analyses were carried out on data from the Smoking Drinking Drug Use Survey 2016 (N = 12,051) on adolescents aged 11–15 years across England.

Results

The results show that imitation, peer association, attitudes and parental reinforcement mediate drug use at ages 12–14 and for some regions but not for gender.

Conclusion

Drug use is a socially learnt behaviour in adolescents students living in England.

Introduction

Illicit drug use is a significant public health concern in the United Kingdom that affects society on a macro and micro level (Stead, Mackintosh, Eadie, & Hastings, Citation2001). Trade in illicit drugs is a multi-billion-pound industry and it remains very attractive to drug gangs and suppliers, who are constantly shifting and adapting to the market conditions. Despite strict laws and regulations controlling possession and supply of illicit drugs (McCambridge & Strang, Citation2005; Morgan et al., Citation2010), the United Kingdom is considered to have the largest and most accessible market for legal highs such as spice, bath salts, Kitkat, Kryptonite, in the whole of Europe (UNODC, Citation2013, Citation2020).

Why focus on adolescents?

Although very few children initiate illicit drug use before 8 years of age, the risk of experimentation is steep during adolescence for each year between the age of 10 and 18 (Bennett, Citation2014; L. Johnston, Citation2010; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, Citation2010; Sloboda et al., Citation2012). 5.9% of the total UK population, equating to approximately 3.4 million, are adolescents aged between 11 and 15 years (Office for National Statistics, Citation2021). 15% of 11 to 15 year olds in England alone have used an illicit drug at least once (Health and Social Care Information Centre, H, Citation2016). This statistic is supported by European research on drug use which shows that young people in the UK not only start taking drugs at an earlier age but are more likely to have consumed illegal drugs than their peers in the rest of Europe (EMCDDA, Citation2015). In England, drug use in young people increased significantly from 15% to 24% between 2014 and 2017 (NHS Digital, Citation2017) following a period of steady decline. Similarly, hospital admission data show that illicit drug-related mental and behavioral disorders admissions increased 4% from 840 in 2015/16 to 871 in 2016/17 for adolescents under 15 years (Health and Social Care Information Centre, H, Citation2016); and that the numbers of young people aged 15 years and under presenting for treatment after consumption of illicit drugs increased by 3% from 2015/16 compared to 2016/17 (Public Health England, Citation2017). Equivocally, there has been an increase in death rates of those under 20 years in the same time period due to accidental poisoning from illicit drugs from 46 (2016) to 51 (2017) (Office for National Statistics, Citation2018). Data from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) which collects information on young people in treatment for substance use below 18 years (Public Health England, Citation2017) also show that the number of children under the age of 14 years presenting for treatment has increased by 10%. Almost half of the young people attending the treatment clinics were below the age of 16 years and females in treatment were of a lower median age (15 years) than males (16 years).

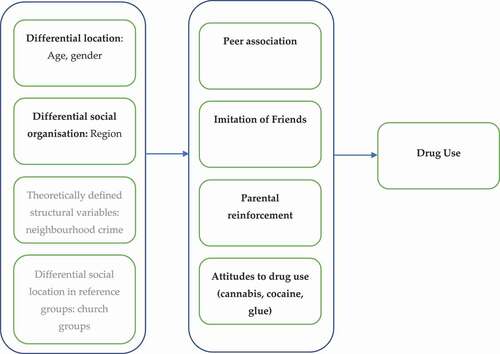

We also now know that the social environment comprises a dynamic set of interactions between the environment and the individual factors such as age and gender (Bandura & Walters, Citation1977; Griffin & Botvin, Citation2010; Sutherland & Shepherd, Citation2001a, Citation2001b; Unlu et al., Citation2014; Verrill, Citation2005; Vogel et al., Citation2015; Whitesell et al., Citation2014; Winfree & Bernat, Citation1998). These interactions form social networks of parents, children, peers, etc., which according to Baler and Volkow (Citation2011) are modulators of gene expression, cognition, emotion and brain function and development. Under this narrative, drug use in adolescents is very much interlinked with youth culture including, friends, peers and parents and should not be examined in isolation. This research applies the Social Structure Social Learning (SSSL) theory () which is an integrated conceptual theory that embodies these very interlinkages/interactions to examine drug use pathways for each age, gender and region. It builds upon an established classical theory – the social learning theory – that focuses on processes through which drug use is learnt which is empirically supported by a large body of evidence (Akers et al., Citation1979; Bandura & Walters, Citation1977; Krohn, Citation1999; Krohn et al., Citation2016; Matsueda, Citation1982; Pratt et al., Citation2010).

Aims and objectives

The following research questions were addressed in this study as follows: 1) Is there an association between social learning (parental reinforcement, imitation, peer association, attitudes) and drug use? 2) Is social structure (age, gender and region) associated with drug use in the last year? 3) Do social learning constructs (imitation, peer association, family reinforcement and attitudes to drugs) mediate the association between social structure (age, gender and region) on illicit drug use? For the purpose of this study only the first two of the Social Structure constructs, that is differential social location (age, gender) and differential social organization (region) were studied in relation to all four of the social learning variables.

Materials and methods

This research is a deductive theory testing approach delineated by core assumptions on ontology (realism), epistemology (positivism), human nature (determinism) and methodology (nomothetic). That is, the reality of harm from illicit drug use exists external to social actors that it can be prevented or reduced and can be increasingly known by accumulating more complete information (Guba, Citation1990). The study is based on a quantitative methodology involving secondary data from the most recent Smoking Drinking and Drug Use among Young People Survey (SDDS) dataset carried out in 2016 (SN: 8320). The SDSS 2016 was a cross-sectional national study based on a self-completion survey of 12,051 pupils aged between 11 and 15 years (Grade 7–11) from 177 secondary schools across England in the autumn term of 2016. Details of sampling and weighting can be obtained from UK data research.

Variables of interest

The variables used in the study have been summarized in the :

Table 1. Variables of interest.

Data analysis

In the first part of the analyses, descriptive data analyses were carried out to understand the characteristics of the English adolescents (). The socio-demographic data included: age, region, gender of the sample and drug use in the last year for the 12,051 students in the dataset. After testing for frequencies, cross tabulation was carried out to analyze the patterns and trends between the subgroups in the independent (age, gender and region) and mediator variables (peer association, peer imitation, parental reinforcement and attitudes) with drug use. Following this, a series of mediation analyses were carried out as follows: Social Learning Model (Model 1), the first step involves using binomial logistic regression to test for association between the mediator variables (differential association, differential reinforcement, imitation, and attitude) and drug use Social Structure Model (Model 2), the second step involves testing for association between the independent variables (age, gender and region) and drug use using binomial logistic regression to obtain an estimate of the association between X (Social Structure) and Y (drug use); and the final step is to test the aggregate SSSL Mediation model (Model 3) using binomial regression. Multinomial regressions were first carried out between Social Structure (SS) and Social Learning (SL) variables to test for association between X (SS) and M (SL) separately.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics.

The models

Social Learning Model – Model 1 ()

Social Structure Model – Model 2 ()

Aggregate SSSL Mediation model – Model 3 ()

Figure 4. (SSSL Model 3).

There must be a significant path of association from X to M and then from M to Y (Model 2) for mediation to be considered between X and Y by M (Model 3). Therefore, multinomial (attitude and imitation) and ordinal (peer association and parental reinforcement) regressions were first carried out between the SS and SL variables to test for association between X and M before running model 3.

Results

Reported next are the results of the mediation analyses.

Model 1: social structure model

The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (13) = 438.3 p < .001 and the model explained 8% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variation in drug use in the last year and correctly classified 84% of the cases (). The model fit, Wald X2 statistic shows a significant contribution by region (X2 =30.2, p < .001), age (X2 = 375.7 p < .001) but not by gender (X2 = .88, NS (p < .349)). Increasing age was associated with an increased likelihood of drug use in the last year. More specifically, 11 year old adolescents were 81% less likely to have used drugs in the last year than their 15 year old counterparts. Adolescents in the London were 103% were more likely to have used drugs in the last year as were those living in North West (44%), East of England (30%) and South East (45%) than those living in the South West of the country. Gender is not significantly associated with drug use in this model.

Table 3. Social Structure Model.

Model 2: social learning model

The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (11) = 1626.60 p < .001 and the model explained 59% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in drug use and correctly classified 92% of the cases (). The model fit Wald X2 statistic show that attitudes to cannabis (X2 = 189.63 df = 2), p < .001), cocaine (X2 = 7.34 df(2), p < .05) and glue use (X2 = 19.58 df(2), p < .001), peer association (X2 = 81.30 df(2) p≤<.001), family reinforcement (X2 = 418.43 df(2), p < .001) and imitation (X2 = 57.09 df(1), p < .001), contributed significantly to the model. All social learning measures were significantly associated with drug use.

Table 4. Social Learning Model.

The peer association variable has the strongest influence on drug use compared to any of the other social learning variables. Adolescents who perceived that most or all of their peers own age were taking drugs were themselves 14 times more likely to have taken drugs in the last year compared to adolescents who perceived that none of their peers took drugs. Consistent with previous research and the correlation matrix results above, drug use is highly correlated with peer association (Akers, Citation2011), more than any other social learning variable.

Adolescents with a positive attitude to cannabis use were 9.8 times more likely to have used drugs in the last year compared to those with a negative attitude. Furthermore, those who had ambivalent attitudes to cocaine had lower odds of drug use in the last year. Comparatively, those with positive attitudes to glue who had twice the odds of having used drugs in the last year. This data indicates that the acceptability of cannabis is the greatest followed by glue and cocaine.

Those who reported having taken drugs for the first time because of imitating friends, had 8.5 times the odds of drug use in the last year. Adolescents who reported strong parental disapproval (stop me from taking drugs) and disapproval (persuade me not to take drugs) were 93% less likely to have used drugs in the last year (OR = .07).

Model 3: aggregate social structure social learning model

The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (24) = 2283.37, p < .001. The social learning model explained 42% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in drug use and correctly classified 89% of the cases (). The results indicate that the while the aggregate model is an improvement on the SS model (Model 1), it is not better than the SL model (Model 2).

Table 5. Cumulative Social Structure Social Learning Model.

As expected, the odds of drug use became insignificant for all social structural variables once the social learning variables were introduced except for 11 year old adolescents. 11 year old adolescents are now 50% (compared to previously being only 20%) more likely to have used drugs in the last year after the introduction of social learning variables compared to 15 year old adolescents.

Similarly, the odds of drug use in the North West, East of England, London and South East regions became insignificant after the introduction of social learning variables. Drug use by adolescents in the having the perception that peers were using drugs mediated drug use in the North West (both categories) and London (half or less). Drug use was also mediated in the North West by positive attitudes to glue use. As there were no associations between East England and South East with social learning variables, mediation cannot be claimed.

Gender as with the remaining other regions remained insignificant after the introduction of social learning variables.

Discussion

The conceptual underpinning in this study is the SSSL, which posits that an adolescent’s age, gender or the location in which they live in affects their chances of learning drug use through four social learning processes which are imitation, peer association, parental reinforcement and attitudes to drugs.

Social learning model

Imitation of friends and peer association

Having the perception that most or all peers take drugs was the strongest social learning variables associated with drug use. Perceiving that most or all peers were taking drugs was associated 14 times with the odds of drug use in the last year and perception of having less than half of peers taking drugs was associated with only 3.5 times the risk of taking drugs. Adolescents who reported imitation were 8.5 times likely to have used drugs in the last year compared to those who did not imitate their friends. The findings corroborate the findings of Young and Weerman (Citation2013; Young, Rebellon, Barnes, & Weerman, Citation2014) that overestimating peer use has the strongest effect of delinquency and this is particularly true of adolescents who value social approval. Researchers employing the SSSL framework have also found perception of peer drug use to be the most robust and consistent predictor of drug use and when pitted against imitation, this construct performs much better (Cooper & Klein, Citation2018; Duncan et al., Citation2014; Giannotta et al., Citation2014; Holland-Davis, Citation2006; Hwang & Akers, Citation2006; Solakoglu & Yuksek, Citation2020). Imitation on the other hand, having previously been one of the weaker social learning pathways in previous studies using the SSSL framework (Hwang & Akers, Citation2006; Kim, Citation2010; Lanza-Kaduce & Capece, Citation2003; Lee, Akers, & Borg, Citation2004) was found to be a strong social learning pathway in this study. This could be because the studies measured imitation indirectly in that they measured imitation through observation of role models taking drugs and stopped short of asking about the respondent’s own drug use as a result of observing drug use (Cooper & Klein, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2013).

Attitudes to cannabis, cocaine and glue

This is the first study to have tested the effects of attitudes to three different types of drugs separately in an SSSL framework. Not only is cocaine the most difficult to get hold of comparatively but it is thought of as “hard drug” by users which implies that it is addictive, needs to be injected and is taken for dramatic/profound effects; cannabis is regarded as being in the “soft drug” category and is a suppressant/ depressant which means it has the opposite effect to cocaine (Fothergill et al., Citation2009; Palamar, Citation2014; Schaefer et al., Citation2015; Seddon, Citation2008). Class A drugs such as cocaine according to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 are the most harmful of the three possible drug classes; this class also carries the most severe penalties for possession, supply and production. Cannabis is a class B drug and carries less severe penalties than class A drugs. Glue on the other hand is not a scheduled or illegal substance, is known to give users a high upon inhalation and is the easiest to access of all the three.

In this study, positive attitudes to cannabis had a stronger association to drug use than positive attitudes to glue. The association between positive attitudes to cocaine and drug use was insignificant. The most important point to note here is that having a positive attitude toward and being ambivalent to trying both cannabis and glue were risk factors for drug use, that is, they increased the odds of taking drugs compared to having a negative attitude. 6.3% of the respondents reported that they did not know if it was acceptable to try cocaine, 14.1% did not know if it was acceptable to try glue and 8.1% did not know if it was acceptable to try cannabis.

Parental reinforcement

The results showed that both measures of parental disapproval: “strong parental disapproval” and “disapproval” had significant associations with drug use. 2.3% of adolescents reported strong parental disapproval and drug use in the last year compared to 0.4% who reported less authoritative parental disapproval and drug use. However, 14% of adolescents who reported that their parents would neither disapprove nor approve of their drug use had taken drugs in the last year. Corroborating the first set of findings from the descriptive analyses, is research showing that high levels of authoritarian parenting control and restrictions (Becoña et al., Citation2013; Calafat, García, Juan, Becoña, & Fernández-Hermida, Citation2014) tend to exacerbate adolescent substance.

Social structure (SS), SSSL models

Although the descriptive data analysis revealed that more boys than girls had used drugs in the last year (albeit the difference was only 0.3%), the association with drug use was not significant as evident in the crosstabulation, correlation matrix and model 1 regression analysis. That is there was no difference between males and females for drug use.

The results of the cumulative analysis show that drug use was mediated by social learning variables for all ages except for age 11 where drug use appears to be moderated, for some regions but not for gender.

Conclusions

The first part of the paper was able to demonstrate an association between a) social learning (parental reinforcement, imitation, peer association, attitudes) and drug use b) social structure (age, gender and region) and drug use and to an extent c) that imitation, peer association, family reinforcement and attitudes to drugs mediate the association between age (12–14), some regions (but not gender) and illicit drug use.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the SDDS 2016 survey is based on self-report measures and on self-incriminating behaviors that can generate methodological response bias and inaccurate reporting (Delaney-Black et al., Citation2010; Percy et al., Citation2005; Williams & Nowatzki, Citation2005). Second, this study employs secondary data analysis which means that the data is situational and not collected for the intents and purposes of this study (M. P. Johnston, Citation2017); however, the dataset was of considerable breadth and also contained factors known to be associated with drug use in young people (Koziol & Arthur, Citation2012). Third, the results pertaining to the region London should be interpreted with caution due to the low response rate. Finally, what these analyses do not show are the specific social learning mediators or pathways to drug use for each of the social structural factors (age, gender and region).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akers, R. L. (2011). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Transaction Publishers.

- Akers, R. L., Krohn, M. D., Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Radosevich, M. (1979). Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 636–655. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094592

- Baler, R. D., & Volkow, N. D. (2011). Addiction as a systems failure: Focus on adolescence and smoking. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.008

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory(Vol. 1). Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs.

- Becoña, E., Calafat, A., Fernández-Hermida, J. R., Juan, M., Sumnall, H., Mendes, F., & Gabrhelík, R. (2013). Parental permissiveness, control, and affect and drug use among adolescents. Psicothema, 25(3), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.294

- Bennett, T. H. (2014). Differences in the age-drug use curve among students and non-students in the UK. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(3), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12100

- Calafat, A., García, F., Juan, M., Becoña, E., & Fernández-Hermida, J. R. (2014). Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 138, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.705

- Cooper, D. T., & Klein, J. L. (2018). Examining college students’ differential deviance: A partial test of social structure-social learning theory. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(5), 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1443868

- Delaney-Black, V., Chiodo, L. M., Hannigan, J. H., Greenwald, M. K., Janisse, J., Patterson, G., … Sokol, R. J. (2010). Just say “I don’t”: Lack of concordance between teen report and biological measures of drug use. Pediatrics, 126(5), 887–893. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3059

- Duncan, D. T., Palamar, J. J., & Williams, J. H. (2014). Perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling, peer illicit drug disapproval and illicit drug use among U.S. high school seniors. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, And Policy, 9(1), 35-35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-35

- EMCDDA. (2015). European Drug Report 2015: Trends and Developments.

- Fothergill, K. E., Ensminger, M. E., Green, K. M., Robertson, J. A., & Hee Soon, J. (2009). Pathways to adult marijuana and cocaine use: A prospective study of African Americans from age 6 to 42. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/20617620

- Giannotta, F., Vigna-Taglianti, F., Rosaria Galanti, M., Scatigna, M., & Faggiano, F. (2014). Short-term mediating factors of a school-based intervention to prevent youth substance use in Europe. The Journal Of Adolescent Health: Official Publication Of The Society For Adolescent Medicine, 54(5), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.009

- Griffin, K. W., & Botvin, G. J. (2010). Evidence-based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(3), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.005

- Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. Sage Publications.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre, H. (2016). Hospital episode statistics. HES.

- Holland-Davis, L. (2006). Putting behavior in context: A test of the social structure-social learning model [Ph.D., University of Florida]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: Social Sciences. Ann Arbor. http://search.proquest.com/docview/920010611?accountid=11979http://onesearch.lancs.ac.uk/openurl/44LAN/44LAN_services_page??url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&genre=dissertations+%26+theses&sid=ProQ:ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+A%26I&atitle=&title=Putting+behavior+in+context%3A+A+test+of+the+social+structure-social+learning+model&=&date=2006-01-01&volume=&issue=&spage=äHolland-Davis%2C+Lisa&isbn=9781267146458&jtitle=&btitle=&rft_id=info:eric/&rft_id=info:doi/

- Hwang, S., & Akers, R. L. (2006). Parental and peer influences on adolescent drug use in Korea. Asian Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-006-9009-5

- Johnston, L. (2010). Monitoring the future: National results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. DIANE Publishing.

- Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2009: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50 (NIH Publication No. 10-7585). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED514367.pdf

- Johnston, M. P. (2017). Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 3(3), 619–626.

- Kim, E. (2010). A comparative test of the social structure and social learning model of substance use among South Korean adolescents [Ph.D., University of Florida]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: Health & Medicine; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: Social Sciences. Ann Arbor. http://search.proquest.com/docview/860591303?accountid=11979http://onesearch.lancs.ac.uk/openurl/44LAN/44LAN_services_page??url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&genre=dissertations+%26+theses&sid=ProQ:ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+A%26I&atitle=&title=A+comparative+test+of+the+Social+Structure+and+Social+Learning+model+of+substance+use+among+South+Korean+adolescents&=&date=2010-01-01&volume=&issue=&spage=äKim%2C+Eunyoung&isbn=9781124513379&jtitle=&btitle=&rft_id=info:eric/&rft_id=info:doi/

- Kim, E., Akers, R. L., & Yun, M. (2013). A cross-cultural test of social structure and social learning: Alcohol use among South Korean adolescents. Deviant Behavior, 34(11), 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2013.782787

- Koziol, N., & Arthur, A. (2012). An introduction to secondary data analysis. http://r2ed.unl.edu/presentations/2011/RMS/120911_Koziol/120911_Koziol.pdf

- Krohn, M. D. (1999). Social learning theory: The continuing development of a perspective. Theoretical Criminology, 3(4), 462–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480699003004006

- Krohn, M. D., Loughran, T. A., Thornberry, T. P., Jang, D. W., Freeman-Gallant, A., & Castro, E. D. (2016). Explaining adolescent drug use in adjacent generations testing the generality of theoretical explanations. Journal of Drug Issues, 46(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042616659758

- Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Capece, M. (2003). Social structure-social learning (SSSL) and binge drinking: A specific test of an integrated general theory. In R. L. Akers, & G. F. Jensen (Eds.), Social learning theory and the explanation of crime: Aguide for the new century. Advances in criminological theory (Vol. 11, 1st ed., pp. 179–196). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315129594

- Lee, G., Akers, R. L., & Borg, M. J. (2004). Social learning and structural factors in adolescent substance use. Western Criminology Review, 5(1), 17–34. https://www.westerncriminology.org/documents/WCR/v05n1/article_pdfs/lee.pdf

- Matsueda, R. L. (1982). Testing control theory and differential association: A causal modeling approach. American Sociological Review, 47(4), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095194

- McCambridge, J., & Strang, J. (2005). Age of first use and ongoing patterns of legal and illegal drug use in a sample of young Londoners. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(3), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-200049333

- Morgan, C. J. A., Muetzelfeldt, L., Muetzelfeldt, M., Nutt, D. J., & Curran, H. V. (2010). Harms associated with psychoactive substances: Findings of the UK National Drug Survey. Journal Of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 24(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109106915

- NHS Digital. (2017). Hospital admitted patient care activity, 2016-17. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/2016-17

- Office for National Statistics. (2018). Deaths related to drug poisoning, England and Wales. Author. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2018registrations

- Office for National Statistics. (2021). Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid2020, National and subnational mid-year population estimates for the UK and its constituent countries by administrative area, age and sex. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/latest#age-structure-of-the-uk-population

- Palamar, J. J. (2014). Predictors of disapproval toward “hard drug” use among high school seniors in the US. Prev SciPrevention Science, 15(5), 725–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0436-0

- Percy, A., McAlister, S., Higgins, K., McCrystal, P., & Thornton, M. (2005). Response consistency in young adolescents’ drug use self-reports: A recanting rate analysis. Addiction, 100(2), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00943.x

- Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Sellers, C. S., Thomas Winfree, L., Jr, Madensen, T. D., Daigle, L. E., Fearn, N. E., & Gau, J. M. (2010). The empirical status of social learning theory: A meta‐analysis. Justice Quarterly, 27(6), 765–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820903379610

- Public Health England. (2017). Young people’s statistics from the national drug treatment monitoring system (NDTMS). Author. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/762446/YPStatisticsFromNDTMS2017to2018.pdf

- Schaefer, B. P., Vito, A. G., Marcum, C. D., Higgins, G. E., & Ricketts, M. L. (2015). Heroin use among adolescents: A multi-theoretical examination. Deviant Behavior, 36(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2014.910066

- Seddon, T. (2008). Youth, heroin, crack: A review of recent British trends. Health Education, 108(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280810867105

- Sloboda, Z., Glantz, M. D., & Tarter, R. E. (2012). Revisiting the concepts of risk and protective factors for understanding the etiology and development of substance use and substance use disorders: Implications for prevention [Article]. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(8/9), 944–962. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.663280

- Solakoglu, O., & Yuksek, D. A. (2020). Delinquency among Turkish adolescents: Testing Akers’ social structure and social learning theory. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 64(5), 539–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X19897400

- Stead, M., Mackintosh, A. M., Eadie, D., & Hastings, G. (2001). Preventing. adolescent drug use: The development, design and implementation of the first year of ‘NE Choices’. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy,8,151–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630010019325

- Sutherland, I., & Shepherd, J. P. (2001a). The prevalence of alcohol, cigarette and illicit drug use in a stratified sample of English adolescents. Addiction, 96(4), 637–640. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96463712.x

- Sutherland, I., & Shepherd, J. P. (2001b). Social dimensions of adolescent substance use. Addiction, 96(3), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634458.x

- Unlu, A., Sahin, I., & Wan, T. T. H. (2014). Three dimensions of youth social capital and their impacts on substance use. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(4), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2013.786934

- UNODC. (2013). World drug report. UNODC. /content/book/d30739c2-en. http://dx.doi.org/10.18356/d30739c2-en

- UNODC. (2020). Word Drug Report (Cross cutting issues: evolvin trends and new challenges Issue. https://wdr.unodc.org/wdr2020/field/WDR20_BOOKLET_4.pdf

- Verrill, S. W. (2005). Social structure and social learning in delinquency: A test of Akers’ social structure-social learning model (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of South Florida, Tampa.

- Vogel, M., Rees, C. E., McCuddy, T., & Carson, D. C. (2015, May). The highs that bind: School context, social status and marijuana use [Article]. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 44(5), 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0254-8

- Whitesell, N. R., Asdigian, N. L., Kaufman, C. E., Big Crow, C., Shangreau, C., Keane, E. M., Mousseau, A. C., & Mitchell, C. M. (2014, March). Trajectories of substance use among young American Indian adolescents: Patterns and predictors. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 43(3), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0026-2

- Williams, R. J., & Nowatzki, N. (2005). Validity of adolescent self-report of substance use. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-200049327

- Winfree, L. T., Jr, & Bernat, F. P. (1998). Social learning, self-control, and substance abuse by eighth grade students: A tale of two cities. Journal of Drug Issues, 28(2), 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204269802800213

- Young, J. T., Rebellon, C. J., Barnes, J. C., & Weerman, F. M. (2014). Unpacking the black box of peer similarity in deviance: Understanding the mechanisms linking personal behavior, peer behavior, and perceptions. Criminology, 52(1), 60–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12029

- Young, J. T., & Weerman, F. M. (2013). Delinquency as a consequence of misperception: Overestimation of friends' delinquent behaviour and mechanisms of social influence. Social Problems, 60(3), 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2013.60.3.334