ABSTRACT

Objective

To study the relationship between socioeconomic position (SEP) and adolescent substance use and explore the role of poor mental health in that relationship.

Methods

Adolescents aged 11–15 years participated in the Health Behavior in School-aged Children survey in Armenia. Robust Poisson regression and counterfactual mediation analysis were used.

Results

In a pooled analysis with 6512 adolescents, the adjusted prevalences of current smoking (prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.93, 95%CI = 1.29–2.88), weekly beer (PR = 1.46, 95%CI = 1.07–2.01), spirits (PR = 1.54, 95%CI = 1.01–2.37) or lifetime cannabis use (PR = 3.10, 95%CI = 0.91–10.59) were greater in low-SEP adolescents compared to the middle-SEP group. Poor mental health explained 25.6%-54.7% of that relationship. Similarly, high-SEP adolescents had increased risks of current smoking (PR = 1.54, 95%CI = 0.98–2.42), weekly beer (PR = 1.55, 95%CI = 1.11–2.18), spirit (PR = 1.58, 95%CI = 1.02–2.45), wine (PR = 1.33 95%CI = 1.01–1.75) intake, than middle-SEP adolescents.

Conclusions

Both low- and high-SEP adolescents in Armenia are at greater risk of substance use than the middle-income group. Poor mental health substantially contributes to substance use among low-SEP adolescents. Additional studies are needed to clarify the motives for substance use among high-SEP adolescents.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental period when future long-term health behavior patterns are established, including risk-taking behavior, such as substance use (Sawyer et al., Citation2012). Alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis are the most commonly used substances among adolescents with alarmingly high rates in Europe. The European average of the past-30-day alcohol and cigarette use in 16-year-old adolescents is 47.0% and 20.0%, respectively, while 16.0% report lifetime cannabis use (ESPAD Group, Citation2020). At the same time, substance use might have a negative impact on adolescent growth, neurocognitive functioning, emotional regulation, and brain development (Degenhardt et al., Citation2016; Subramaniam & Volkow, Citation2014). Also, it can increase the likelihood of other risky health behaviors, such as unprotected sex, fighting, and reckless driving, and may eventually cause health problems, such as heart disease, hypertension, and sleep disorders, later in life (Degenhardt et al., Citation2016; Subramaniam & Volkow, Citation2014).

Traditionally, adolescents from low-SEP families are considered to be at greater risk of substance use (Degenhardt et al., Citation2016). In addition, a recent study among a nationally representative sample of Armenian adolescents showed a strong relationship between adolescent socioeconomic position (SEP) and health (Torchyan & Bosma, Citation2020), rejecting West’s equalization hypothesis (West & Sweeting, Citation2004) that adolescence is a time of relative health equality due to increased peer influence. This suggests that risky health behaviors, such as substance use, might also be socioeconomically patterned in Armenia, with low-SEP adolescents at greater risk of substance use than middle- and high-SEP adolescents. The latter conforms to other studies reporting a higher prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among low-SEP adolescents compared to their peers from higher-income families (Andrabi et al., Citation2017; Gomes de Matos et al., Citation2017; Greene et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2016; Shackleton et al., Citation2019). For example, low SEP adolescents in Iceland had approximately 4.2, 1.7, and 2.3 times greater risk of regular smoking, heavy episodic drinking, and recent cannabis use, respectively, than high-SEP respondents (Shackleton et al., Citation2019). However, increasing concern over adolescent substance use and considerable variability in the SEP-substance use relationship between countries (Gomes de Matos et al., Citation2017; Shackleton et al., Citation2019) highlights the need for a more thorough investigation of the role of SEP considering alternative measures and context-specific mechanisms contributing to substance use among adolescents.

It is well established that low SEP is a strong predictor of poor mental health among adolescents (Elgar et al., Citation2015; Reiss, Citation2013), which can be explained by the social stress theory (Aneshensel, Citation1992). According to that theory, due to a range of social, economic, and environmental conditions, socially disadvantaged people have higher stress levels and fewer coping resources, resulting in poor mental health. In addition, longitudinal studies show that poor mental health can predict tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among adolescents (Bierhoff et al., Citation2019; Danzo et al., Citation2017; Parrish et al., Citation2016; Schleider et al., Citation2019; Wilkinson et al., Citation2016). For instance, in a longitudinal study among US youth, each unit increase in the mental health problems score increased the likelihood of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use by 5.0% – 11.0% (Bierhoff et al., Citation2019). This might support motivational models of substance use (Marshall et al., Citation2020; Sher, Citation2016) that suggest that one of the primary motives for substance use might be the expectation that substance use will alleviate mental health issues or help escape from those issues. The aforementioned implies that poor mental health can potentially explain the higher rates of substance use among low-SEP adolescents.

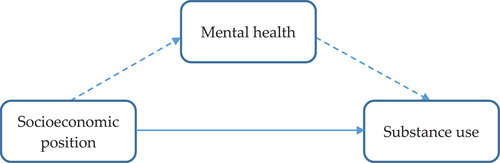

Armenia is one of the former Soviet countries struggling from a poor economic situation after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Tobacco use in Armenia is among the highest globally, with 51.5% of adult men smoking (Andreasyan et al., Citation2018). Hazardous alcohol drinking and cannabis use are prevalent as well (10.5% and 3.5%, respectively) (Global status report on alcohol and health Citation2018; World Drug Report Citation2021). However, little information is available on socioeconomic factors and potential mechanisms contributing to substance use among Armenian adolescents. Therefore, this paper aimed to study the relationship between SEP and unhealthy behaviors (tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use) in a nationally representative sample of Armenian adolescents and explore the role of poor mental health in that relationship. We hypothesize that 1) substance use rates are higher among low-SEP adolescents than among adolescents with middle and high SEP, and 2) poor mental health will partially mediate the association between low SEP and substance use ().

Materials and methods

Design and data collection

Data for this study were derived from the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey. The HBSC study is a WHO collaborative study conducted in Armenia in 2009/10 and 2013/14 years using internationally standardized protocols (Currie et al., Citation2010, Citation2014). The study was cross-sectional. The study population comprised adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 years selected using a cluster sampling technique. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to adolescents at schools. Ethical approval was gained before conducting the survey, and informed consent was obtained from all participants (Currie et al., Citation2010, Citation2014; Sargsyan et al., Citation2016). This article is based on fully anonymized secondary data available online in the HBSC Data Management Center (“The HBSC Data Management Centre”, Citation2021).

Measures

Substance use

Smoking status was assessed using the following question: “How often do you smoke tobacco at present?” Response options were “every day,” “at least once a week, but not every day,” “less than once a week,” and “I do not smoke.” Adolescents were classified into “current smokers” and “non-smokers,” respectively. This measure of adolescent tobacco use has been shown to have 90% sensitivity and 93% specificity compared to the salivary cotinine test for tobacco use (Post, Citation2005). Also, adolescents were asked about the frequency of alcohol consumption and were provided with the list of drinks: beer, spirits, wine, etc. Response options ranged from “every day,” “every week,” “every month,” “rarely,” to “never.” The answers were dichotomized into “at least weekly” and “less than weekly.” In a validation study, a single question measuring the frequency of adolescent alcohol use correlated strongly (Spearman’s Rho = 0.903) with a Timeline Follow Back Calendar, a criterion standard measure of alcohol consumption (Levy et al., Citation2021). Lifetime cannabis use was measured in 15-year-old adolescents by asking if they have ever used cannabis. Response options were: “never,” “1–2 days,” “3–5 days,” “6–9 days,” “10–19 days,” “20–29 days,” and “30 days (or more).” Answer options were combined into “≤ 1–2 days” and “> 1–2 days.” The question on lifetime cannabis use has been shown to have good internal consistency (Cohen’s k = 0.862) and test-retest reliability (Spearman’s Rho = 0.855) (Molinaro et al., Citation2012).

Mental health

The composite score of mental health problems was calculated by summing the standardized scores of two health measures, i.e., psychosocial well-being and psychosomatic complaints, and converting into a reversed scale ranging from 1 (low) to 10 (high). Psychosocial well-being was measured with the adapted version of the Cantril Ladder (Currie et al., Citation2010, Citation2014), where the top of the ladder represented the best possible life “10,” and the bottom indicated the worst possible life “0.” This scale has been shown to be a valid measure of adolescent psychosocial well-being, especially related to self-perception, psychological well-being, moods and emotions, parent relations, and school environment dimensions (Mazur et al., Citation2018). Psychosomatic complaints score ranged from 8 to 40 by summing the frequencies (1- about every day, 2 – more than once a week, 3 – about every week, 4 – about every month, 5 – rarely or never) of eight psychological and somatic complaints that have been present for at least six months. Symptoms included headache, stomachache, backache, feeling low, irritability or bad temper, feeling nervous, difficulty in getting to sleep, and feeling dizzy. A validation study of this score reported good content validity and high test-retest reliability (interclass correlation coefficient = 0.79) (Haugland & Wold, Citation2001).

Socioeconomic position

The following question was asked to measure the family SEP: “How well off do you think your family is?” Response categories were “1 – quite well of,” “2 – very well of,” “3 – average,” “4 – not very well of,” and “5 – not at all well of.” The answer options were reclassified into “1 – high,” “2 – middle,” and “3,4,5 – low” categories, respectively. This measure of family SEP has been shown to have a high concurrent validity among adolescents (Svedberg et al., Citation2016). The Armenian translation of “well off” is interpreted in financial/material terms (Բարեկեցիկ).

Statistical analysis

Data from the HBSC 2009/10 and HBSC 2013/14 surveys were pooled to create a robust sample of adolescents reporting substance use and improve statistical power. Sample characteristics of each survey round/year can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the overall sample. The mental health problem score was log-transformed because of the substantially skewed distribution. The associations between substance use and adolescent characteristics were evaluated by Pearson’s chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between family SEP and mental health. Poisson regression analyses with robust estimates were used to calculate the prevalence ratios (PR) of substance use by mental health. A counterfactual approach to mediation analysis was used to decompose the total effect of family SEP on substance use into natural direct (NDE) and natural indirect effects (NIE) (Valeri & Vanderweele, Citation2013). The NDE shows the change in the outcome for different levels of exposure controlling for the mediator at its level when the individual is unexposed (i.e., low mental health problems). The NIE shows the change in the outcome for those who are exposed (i.e., high mental health problems) when the mediator changes from its value when the person is unexposed to the value when the person is exposed. The causal mediation analysis was performed using the SPSS macro by Valeri and VanderWeele (Mazur et al., Citation2018), modified to obtain robust standard errors for the Poisson regression parameter estimates. To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed mediation analyses for both rounds/years and each health measure separately. Also, we tested for two-way interactions between family SEP and mental health on substance use by adding product terms to the models. All models were adjusted for age, sex, and survey round/year. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

In a pooled analysis with 6512 adolescents, 2.9% of participants were current cigarette smokers, 5.9%, 3.1%, and 6.9% reported weekly consumption of beer, spirits, or wine, respectively, and 1.0% used cannabis more than 1–2 times over a lifetime (). The prevalence of substance use was significantly (P < .001) higher in boys (). Current smoking and weekly beer consumption were more common (P < .05) among fifteen-year-old adolescents. Low- and high-SEP adolescents were more likely to report substance use than their peers from middle-SEP families. In adolescents reporting substance use, the mental health problems scores were 1.18–1.32 times higher (P < .05).

Table 1. Adolescent characteristics (n = 6512 participantsa).

Table 2. Adolescent characteristics by substance use.

In multivariate analyses, adjusted for age and sex, the relationship between the family SEP (exposure) and the mental health (potential mediator), as well as the mental health and the substance use (outcome), were statistically significant (P < .05). In a linear regression analysis, mental health problems scores were 36% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.31–1.42) and 12% (95% CI = 1.08–1.17) higher in adolescents from low- and middle-SEP families, respectively, compared to the high-SEP adolescents (). In a Poisson regression analysis, each percent increase in the mental health problems score was associated with a 0.69–2.54 percentage increase (P < .05) in the risk of substance use ().

Table 3. Linear regression coefficients (95% confidence interval) of mental health problemsa by family SEP, adjusted for age, sex, and survey round/year.

Table 4. Poisson regression coefficients (95% confidence interval) of substance use by mental health problemsa, adjusted for age, sex, family SEP and survey round/year.

The mediation analysis was performed without exposure-mediator interaction since no statistically significant interactions (P > .05) were observed between family SEP and mental health on substance use. The middle family SEP was taken as a reference category to have positive log-level estimates, considering the lowest prevalences of substance use in the middle-SEP group. In our models, the adjusted prevalences of current smoking (PR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.29–2.88), weekly beer (PR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.07–2.01), weekly spirits consumption (PR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.01–2.37) or lifetime cannabis use (PR = 3.10, 95% CI = 0.91–10.59) were higher in low-SEP adolescents compared to their peers from middle-SEP families. High levels of mental health problems explained 25.6% – 54.7% of that relationship [calculated as log(NIE)/log(total effect)]. The association between low family-SEP and weekly wine consumption was not statistically significant but had the same direction. The natural indirect effects were statistically significant (P < .05) in all models ().

Table 5. Prevalence ratios (95% confidence interval) of substance use by family SEP (adjusted for age, sex, survey round/year) and percentage mediated/suppressed by high/low mental health problemsa.

Similarly, high-SEP adolescents had an increased risk of reporting current smoking (PR = 1.54, 95% CI = 0.98–2.42), weekly beer (PR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.11–2.18), spirit (PR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.02–2.45), or wine (PR = 1.33 95% CI = 1.01–1.75) intake, than middle-SEP adolescents. The mediation analysis showed that high-SEP adolescents’ low mental health problems suppressed the SEP-substance use relationship, and the natural direct effects were 18.0–31.3% stronger than the total effects [calculated as 1 – log(total effect)/log(NDE)]. Despite the similar pattern, no statistically significant association was found between high family-SEP and lifetime cannabis use more than 1–2 times ().

The association patterns persisted in a sensitivity analysis with each survey round/year and health measure separately (Supplementary tables S1-S5). The findings were consistent with those from the primary analysis that both low- and high-SEP adolescents are at increased risk of substance use compared to those from middle-SEP families and that high mental health problems partially mediate that relationship in low-SEP adolescents, whereas low mental health problems suppress it in the high-SEP group.

Discussion

Using the data from the HBSC 2009/10 and HBSC 2013/14 surveys, our study investigated the relationship between SEP and substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis) and evaluated the mediating role of poor mental health in the relationship between low SEP and substance use in a nationally representative sample of Armenian adolescents.

In our study, the risk of substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis) was substantially higher among low- and high-SEP adolescents compared to the middle-income group. Although we did not expect high levels of substance use in high-SEP respondents, a recent cross-national study among adolescents showed that substance use might vary largely between countries, proposing that contextual factors strongly influence adolescents’ substance use behavior (Shackleton et al., Citation2019). Remarkably, their results showed that high-SEP adolescents might be at increased risk of substance use in Eastern European countries (Shackleton et al., Citation2019). Further scrutiny of the factors affecting youth substance use might help to prevent this unhealthy behavior.

Our results show that a substantial proportion of the excess risk of substance use was associated with high mental health problems among low-SEP adolescents. Moreover, high-SEP adolescents seemed to be protected by low levels of mental health problems; controlling for mental health substantially increased the risk of substance use among high-SEP adolescents. Our findings are in agreement with the social stress theory, which suggests that low-SEP might lead to poor mental health (Aneshensel, Citation1992), and theories of adolescent substance use that negative affective states, including anxiety and depression, can increase the likelihood of substance use among adolescents (Petraitis et al., Citation1995). The motivational models for substance use suggest that one of the primary motives for substance use might be the expectation that substance use can help to relieve or escape mental health issues (Sher, Citation2016). Lower levels of self-efficacy in resisting peer pressure among low-SEP adolescents might also increase the risk of substance use (Erci, Citation2021; Hasking et al., Citation2011; Minnix et al., Citation2011; Petraitis et al., Citation1995; Sher, Citation2016).

We also found that the prevalence of substance use in high-SEP respondents was substantially higher than in the middle-SEP group. The mediation analysis showed that the risk of using beer, spirits, and wine among high-SEP adolescents could have been even higher than in the low-SEP group if they were not protected by good mental health. Similar findings have been reported in the US, where adolescents from affluent families reported high substance use (Luthar & Sexton, Citation2004). The authors hypothesized that achievement pressure and lack of parental supervision might explain their findings. In our study, the achievement pressure is less likely to be the primary cause of substance use since high-SEP adolescents reported good mental health, suggesting other common motives for substance use, such as socializing and bonding with others or pleasure-seeking and excitement (Hoffmann, Citation2021; Sher, Citation2016). The post-Soviet sub-culture of “golden youth” (privileged children of wealthy businessmen and bureaucrats) who have been implicated in exhibiting high fun-seeking and irresponsible behavior (Schimpfössl, Citation2018) might play a role in it. Permissive parenting style in high-SEP families directed toward becoming an independent individual can potentially result in lower levels of parental monitoring and indirectly contribute (as mentioned above) toward substance-using behavior among their offspring (Berge et al., Citation2016; Francese, Citation2018). Further studies should explore substance use motives and parenting styles in Armenian adolescents from high-SEP families.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used self-reported data, which is susceptible to bias. For example, students might have provided socially desirable responses, such as underreporting substance use or overreporting their family SEP, which could have affected the strength of the SEP-substance use relationship and the proportion of that relationship explained by poor mental health. However, since the proportion of our study population living in low-SEP families (29.3%) is similar to the official poverty statistics in Armenia (approximately 30.0%) (Social Snapshot and Poverty in Armenia, Citation2017), the possible overestimation of the high-SEP category and underestimation of the low-SEP category would have minimal impact on our results. Second, due to the relatively small sample size, we had to merge the lower three categories of family SEP, potentially underestimating the proportion of the SEP-substance use relationship explained by mental health problems. Third, this study is cross-sectional, and inferring the temporal precedence/causality is difficult. However, in a clinical trial evaluating depression treatment among US youth, substance use did not influence the depression outcome. In contrast, depression severity negatively affected substance use reduction, suggesting temporal precedence of depression over substance use (McKowen et al., Citation2013). Fourth, since the Armenian translation of “well off” that was used to measure the family SEP in our study is interpreted in financial/material terms (Բարեկեցիկ), we did not use the 4-item family affluence scale (the early HBSC version) available in our dataset (Sargsyan et al., Citation2016), which has been shown to have weak discriminatory properties, especially among midrange groups (Svedberg et al., Citation2016). Fifth, although the Cantril scale is a valid measure of psychosocial well-being (Mazur et al., Citation2018), some adolescents could have interpreted it in financial/material terms. Sixth, psychosomatic complaints have a potential disadvantage; somatic symptoms, such as headache, stomachache, backache, and feeling dizzy, can have biological causes and not necessarily psychosomatic. Nevertheless, the findings were very similar between the two different mental health measures that we used. Finally, the findings related to cannabis use were not always statistically significant because of its low prevalence, but the coefficients pointed in the same direction.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings indicate that both low- and high-SEP adolescents in Armenia are at greater risk of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use compared to their peers from middle-income families. We also found that poor mental health substantially contributes to substance use among low-SEP adolescents, which might help in tailoring effective prevention programs in Armenia. Additional studies are needed to better understand the factors affecting substance use among high-SEP adolescents, considering the possible role of poor parental monitoring and motives for substance use, such as socializing and bonding with others or pleasure-seeking and excitement. Our findings warrant further research on the complex relationship between SEP and adolescent substance use, which might be sensitive to the socio-cultural context and depend on differences between countries and changes in time.

Supplements.docx

Download MS Word (39.6 KB)Acknowledgments

HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with WHO/EURO. The International Coordinator of the 2009-10 and 2013/14 surveys was Prof. Candace Currie, and the Data Bank Manager was Prof. Oddrun Samdal. The 2009/10 and 2013/14 surveys were conducted by Principal Investigators in 41 and 42 countries/states, respectively. For details, see http://www.hbsc.org.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the HBSC Data Management Centre at https://www.uib.no/en/hbscdata/113290/open-access

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2022.2084787

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrabi, N., Khoddam, R., & Leventhal, A. M. (2017). Socioeconomic disparities in adolescent substance use: Role of enjoyable alternative substance-free activities. Social Science & Medicine, 176, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.032

- Andreasyan, D., Bazarchyan, A., Torosyan, A., & Sargsyan, S. (2018). Prevalence of tobacco smoking in Armenia, STEPs survey [journal article]. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 16(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/94872

- Aneshensel, C. S. (1992). Social stress - theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.000311

- Berge, J., Sundell, K., Ojehagen, A., & Hakansson, A. (2016). Role of parenting styles in adolescent substance use: Results from a Swedish longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(1), e008979. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008979

- Bierhoff, J., Haardorfer, R., Windle, M., & Berg, C. J. (2019). Psychological risk factors for alcohol, cannabis, and various tobacco use among young adults: A longitudinal analysis. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(8), 1365–1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1581220

- Currie, C., Grieber, R., Inchley, J., Theunissen, A., Molcho, M., Samdal, O., & Dür, W. (2010). Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2009/10 Survey. http://www.hbsc.org/

- Currie, C., Inchley, J., Molcho, M., Lenzi, M., Veselska, Z., & Wild, F. (2014). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory items for the 2013/14 Survey http://www.hbsc.org/

- Danzo, S., Connell, A. M., & Stormshak, E. A. (2017). Associations between alcohol-use and depression symptoms in adolescence: Examining gender differences and pathways over time. Journal of Adolescence, 56(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.01.007

- Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G., Hall, W. D., & Lynskey, M. (2016). The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00508-8

- Elgar, F. J., Pfortner, T. K., Moor, I., De Clercq, B., Stevens, G. W., & Currie, C. (2015). Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002-2010: A time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the health behaviour in school-aged children study. The Lancet, 385(9982), 2088–2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61460-4

- Erci, B. (2021). Effectiveness of gender and drug avoidance self-efficacy on beliefs and attitudes substance use in adolescence. Journal of Substance Use, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2021.1953166

- ESPAD Group. (2020). ESPAD report 2019: Results from the European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs. EMCDDA Joint Publications, Publications Office of the European Union.

- Francese, J. (2018). Parenting styles in relation to socioeconomic status, education, and generation. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639

- Gomes de Matos, E., Kraus, L., Hannemann, T. V., Soellner, R., & Piontek, D. (2017). Cross-cultural variation in the association between family’s socioeconomic status and adolescent alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(6), 797–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12569

- Greene, B., Seepaul, A., Htet, K., & Erblich, J. (2021). Psychological distress, obsessive-compulsive thoughts about drinking, and alcohol consumption in young adult drinkers. Journal of Substance Use 27 (3) , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2021.1941346

- Hasking, P., Lyvers, M., Carlopio, C., & Raber, A. (2011). The relationship between coping strategies, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and drinking behaviour. Addictive Behaviors, 36(5), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.014

- Haugland, S., & Wold, B. (2001). Subjective health complaints in adolescence–reliability and validity of survey methods. Journal of Adolescence, 24(5), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0393

- The HBSC Data Management Centre. (2021). https://www.uib.no/en/hbscdata/113290/open-access

- Hoffmann, J. P. (2021). Sensation seeking and adolescent e-cigarette use. Journal of Substance Use, 26(5), 542–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1856209

- Levy, S., Wisk, L. E., Chadi, N., Lunstead, J., Shrier, L. A., & Weitzman, E. R. (2021). Validation of a single question for the assessment of past three-month alcohol consumption among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109026

- Liu, Y., Lintonen, T., Tynjälä, J., Villberg, J., Välimaa, R., Ojala, K., & Kannas, L. (2016). Socioeconomic differences in the use of alcohol and drunkenness in adolescents: Trends in the health behaviour in school-aged children study in Finland 1990–2014. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816684118

- Luthar, S. S., & Sexton, C. C. (2004). The high price of affluence. Adv Child Dev Behav, 32, 125–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2407(04)80006-5

- Marshall, N., Mushquash, A. R., Mushquash, C. J., Mazmanian, D., & McGrath, D. S. (2020). Marijuana use in undergraduate students: The short-term relationship between motives and frequency of use. Journal of Substance Use, 25(3), 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2019.1683906

- Mazur, J., Szkultecka-Debek, M., Dzielska, A., Drozd, M., & Malkowska-Szkutnik, A. (2018). What does the Cantril ladder measure in adolescence? Archives of Medical Science, 14(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.60718

- McKowen, J. W., Tompson, M. C., Brown, T. A., & Asarnow, J. R. (2013). Longitudinal associations between depression and problematic substance use in the youth partners in care study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(5), 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.759226

- Minnix, J. A., Blalock, J. A., Marani, S., Prokhorov, A. V., & Cinciripini, P. M. (2011). Self-efficacy mediates the effect of depression on smoking susceptibility in adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13(8), 699–705. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr061

- Molinaro, S., Siciliano, V., Curzio, O., Denoth, F., & Mariani, F. (2012). Concordance and consistency of answers to the self-delivered ESPAD questionnaire on use of psychoactive substances. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(2), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1353

- Parrish, K. H., Atherton, O. E., Quintana, A., Conger, R. D., & Robins, R. W. (2016). Reciprocal relations between internalizing symptoms and frequency of alcohol use: Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000138

- Petraitis, J., Flay, B. R., & Miller, T. Q. (1995). Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67

- Post, A. (2005). Validity of self reports in a cohort of Swedish adolescent smokers and smokeless tobacco (snus) users. Tobacco Control, 14(2), 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2004.008789

- Reiss, F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

- Sargsyan, S., Melkumova, M., Movsesyan, Y., & Babloyan, A. (2016). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children of Armenia 2013/14 National Study Results.

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. J., ***, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Schimpfössl, E. (2018). Rich Russians: From oligarchs to bourgeoisie. Oxford University Press.

- Schleider, J. L., Ye, F., Wang, F., Hipwell, A. E., Chung, T., & Sartor, C. E. (2019). Longitudinal reciprocal associations between anxiety, depression, and alcohol use in adolescent girls. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13913

- Shackleton, N., Milne, B. J., & Jerrim, J. (2019). Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent substance use: Evidence from twenty-four European countries. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(6), 1044–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1549080

- Sher, K. J. (2016). The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199381678.001.0001

- Social Snapshot and Poverty in Armenia, 2017. Statistical committee of the Republic of Armenia. Retrieved 05.10.2019 from https://www.armstat.am/en/?nid=82&id=1988

- Subramaniam, G. A., & Volkow, N. D. (2014). Substance misuse among adolescents: To screen or not to screen? JAMA Pediatrics, 168(9), 798–799. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.958

- Svedberg, P., Nygren, J. M., Staland-Nyman, C., & Nyholm, M. (2016). The validity of socioeconomic status measures among adolescents based on self-reported information about parents occupations, FAS and perceived SES; implication for health related quality of life studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0148-9

- Torchyan, A. A., & Bosma, H. (2020). Socioeconomic inequalities in health among Armenian adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114055

- Valeri, L., & Vanderweele, T. J. (2013). Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological Methods, 18(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031034

- West, P., & Sweeting, H. (2004). Evidence on equalisation in health in youth from the West of Scotland. Social Science & Medicine, 59(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.004

- Wilkinson, A. L., Halpern, C. T., & Herring, A. H. (2016). Directions of the relationship between substance use and depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 60, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.036

- World Drug Report. 2021. United nations office on drugs and crime. Retrieved 09.03.2022 from https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr2021.html