Abstract

This study explores seven Swedish top-level women’s soccer players’ career development experiences. Data were produced through semi-structured interviews and a biographical mapping grid. The theoretical framework of ‘careership’ was employed to understand the data. The results showed homogenous career paths. Moreover, the data show that the players decided at a young age to pursue a career in soccer; experienced the transition from junior to senior level soccer as difficult because of a lack of physical preparedness; soccer over school commitments. We recommend that soccer stakeholders (e.g. federations, clubs, coaches) give the transition from junior to senior level soccer special attention to prevent intense demands that may cause dropout. We further propose that if athletes should give sport and education equal priority, the Swedish dual career concept of high school education and sport needs further reflection and adjustment.

Introduction

Soccer is the most popular sport for girls and women. The FIFA’s Women’s Football Survey of 2014 reports that around 30 million girls and women play football.Footnote1 The USA, Germany, Canada and Sweden have the largest populations of female players.Footnote2 The organization of women’s soccer is also well developed. Today, 50 European soccer associations have a women’s national team and 49 countries maintain a domestic women’s league.Footnote3 Moreover, football organizations take the development of women’s soccer, and the promotion of women’s soccer careers particularly seriously. The FIFA, for instance, aims to develop player pathways from grassroots to elite.Footnote4 The UEFA’s Women’s Football Development Programme ‘Free-Kicks’ aims to implement ‘elite youth player pathway programmes to optimise opportunities for talented players in the country’.Footnote5 While these efforts are to be applauded, and undoubtedly have positive effects, the strategies lack scientific foundations as research into girls’ and women’s career paths is limited.

In Sweden, the Swedish Football Association significantly invests in women’s soccer.Footnote6 As a result, Sweden has managed to create a soccer player environment that makes the sport most popular for girls, and which produces more professional female soccer players than in most other nations.Footnote7 This environment is supported by ‘sport schools’ specializing in soccer, which are spread throughout the country and have four academic levels: elementary (age 10–12), secondary (age 13–15), high school (age 16–18) and university (age 18+).Footnote8 The Swedish sport system conceptualizes sport schools as to assist the combination of education and (sub) high-performance sport and support athletes’ transitions into university or professional education. This system reflects the EU guidelines on dual careers, which aim for athletes to combine education and sport training.Footnote9 In 2016, 98 sport secondary schools and 68 sport high schools existed in Sweden. In 2015, 2456 adolescents were accepted to attend a sport secondary school as soccer players. Three-hundred and thirty-seven of these were girls. At the next higher level, the sport high schools accepted 2874 student-players, of which 843 were girls.Footnote10 Despite these dual career options, the dropout rate from sport is high, especially for girls between the ages of 17–20. This period follows high school graduation, which means that athletes must decide to either continue education or develop a professional player career. Research has paid this risk phase little attention, even though it particularly affects Swedish female soccer players.Footnote11

Swedish sport scientists have researched women soccer players’ career experiences. This research shows that those players that continue to play when at high school, complete high school education while developing soccer careers.Footnote12 According to Peterson, however, the majority of players do not reach the higher levels of Swedish soccer because (a) they drop out during adolescence, which is due to multiple reasons; and (b) the Swedish selection system is poorly organized and actually selects out players, rather than develops them.Footnote13 Moreover, research has shown that the dual career experience is demanding and may not provide student-athletes with a desire to continue this pathway at the tertiary education level.Footnote14 Lastly, for women players who do continue playing soccer at high school level, investing in a professional soccer career may make little sense given that this sport currently provides an economically unviable future. Certainly, the potential for economic gain is limited (i.e. a professional soccer salary is on average 1071 Euro/10 426 SEK per month).Footnote15 Undoubtedly, such poor financial prospects is one reason for the high rate by which young women playing at elite level leave soccer upon completing high school.Footnote16 Outside of Sweden, researchers have studied women’s soccer careers in relation to professionalization, gendered socialization, social support and migration. With regard to professionalization, women’s soccer has developed from a socially unaccepted sport to a well-established profitable business that contains a multi-level league organization.Footnote17 With regard to gendered socialization, Eliasson’s research on young soccer players’ experiences shows that girls and boys develop gendered behaviour.Footnote18 What this study shows particularly well is that from a young age, both girls and boys develop their performance towards an idealized male standard.

In terms of social support, Gledhill and Harwood’s retrospective study on female elite players showed that retirement from competitive soccer had occurred by the age of 18, mostly because of a lack of social support both within their training environment and from life outside of sport.Footnote19 Lastly, and in contrast to the early dropout rate, Botelho and Agergaard (Citation2011) showed that women players’ intentions to further their skill development and playing experiences influenced their desire to migrate nationally and internationally. For these players, passion and drive for a professional career was high.Footnote20

The emerging knowledge of how girls and women develop and experience soccer is important. However, a number of questions relating to girls’ and women’s career paths, career decision-making and career transitions remain unanswered. The purpose of this study is to explore highest level Swedish women soccer players’ career paths. We particularly focus on the types of paths that are taken, players’ experiences of developing these, and how structural and contextual factors such as school and selection pressures implicate career development. The following research questions guide the investigation: How do women players experience their childhood and youth soccer experiences? Do they consider a professional soccer career at this young age? How do female players experience and handle their youth years when completing secondary and high school education? And when and how do female players move to the professional level and how do they experience this development? To answer these questions, we draw on data we produced through semi-structured interviews with seven Swedish highest-level professional soccer players, who at the time of the interview were professional players in a premier league in Sweden or abroad, and selected for the Swedish senior national team.

The theory we draw on to understand our data is ‘careership’, a sociological theory of career development that Hodkinson and Sparkes developed to conceptualize how young people develop and experience their educational and professional careers. The concepts of ‘routines’ and ‘turning points’ are particularly guiding. In answering our research questions, we provide insight into professional women soccer players’ career paths and their decision-making in reaction to events that they considered significant (i.e. turning points). In the following, we begin by outlining the theoretical framework we adopt to understand these career paths. This is followed by an overview of women’s soccer in Sweden and a description of the research methods. We then present and discuss our results and close the article with implications our findings have for soccer stakeholders.

Careership: a sociological theory of career development

Sporting careers have been analysed using a number of career theories. The majority of research adopts a psychological perspective and focuses on individual factors, including attitudes and the coping with life transformations.Footnote21 Sociological research, in contrast, has shown that careers develop in complex ways, mainly because social structures (e.g. gender) and local contexts (e.g. sport-specific cultures, school and sport development systems) influence career development behaviour.Footnote22 However, scholars have argued that both these theoretical frameworks are limited in integrating individual and social factors.Footnote23 In order to address this theoretical gap, Hodkinson and Sparkes propose the theory of ‘careership’.Footnote24 This theory builds on Pierre Bourdieu’s work, particularly his concept of ‘habitus’, which he defined as a ‘battery of durable, transposable but also mutable dispositions to all aspects of life’.Footnote25 These dispositions are assumed to shape individuals’ career visions.Footnote26 Hodkinson and Sparkes speak of ‘horizons for action’ to describe these perspectives. These horizons are characterized by four features: First, horizons for action can be seen as visions that guide individual conduct and decision-making. Second, as individuals’ continuously evolve, horizons develop accordingly. Third, in contrast to habitus, both contextual factors and personal dispositions and experiences impact the horizons, and thus career decision-making. Lastly, decision-making cannot be separated from a career pathway; rather, decisions are influenced by and shape the career development process. In sum, horizons develop and evolve in relation to individuals’ dispositions, backgrounds and experiences, and socio-cultural context and forces. They also change in reaction to life events that Hodkinson and Sparkes termed ‘turning points’.Footnote27 As such, these authors understand a career as to exist as part of a ‘routine’, which is maintained, interrupted or altered due to turning points that happen at different times to all individuals.Footnote28

Hodkinson and Sparkes identify five types of routines: confirmatory, contradictory, socializing, dislocating or evolutionary. The confirmatory routine endorses career decisions made at an earlier stage. It is commonly experienced in self-initiated career decisions (i.e. turning points), where individuals transform the routine based on previously made decisions for change. The contradictory routine expresses regret and dissatisfaction. Here, an individual’s experiences may undermine a decision taken earlier, commonly leading to rather transformative career decisions. The socialising routine is described as a temporary stop in order to pursue the original intended career path. The individual adapts to life experiences that do not belong to the desired career, and awaits opportunities to pursue the originally intended career path. The dislocating routine is when a person disapproves of what is required from him/her. The person does not feel that s/he belongs. Finally, the evolutionary routine defines successful movement from one career path to another.Footnote29

Within routines, turning points occur. Different types of turning points are possible: structural, forced and self-initiated. Structural turning points are foreseeable, such as educational graduation or retirement from working. In contrast, forced turning points appear suddenly and unexpected, such as an injury. Self-initiated turning points are the result of an individuals’ initiating a transformation on their own accord.

Careership has been used in sport science, including Allin and Humberstones’ study of physical educators’ performance in outdoor education.Footnote30 In this research, the two scholars found that the teachers’ career development fitted careership’s horizons, routines and turning points.Footnote31 Barker-Ruchti and colleagues drew on careership to study top-level women soccer coaches’ career paths. These scholars found that women soccer coaches did not deliberately develop coaching careers, but entered and developed their careers due to a number of turning points.Footnote32 Further, Barker-Ruchti and colleagues identified the initiating turning point, which Hodkinson and Sparkes did not include in their theory. This turning point represents events that allow individuals to envision a particular horizon (e.g. a particular profession).

Research methods

In order to study career pathways, a retrospective interview study was considered to produce relevant data. This design was influenced by the components included in careership (i.e. routines, turning points, horizons), particularly the research questions we set out to answer. Ethical principles were adhered to, which included the first author of this article informing the interviewees about the study and ethical safeguarding, the signing of consent forms, and measures to ensure the sampled soccer players’ anonymity.Footnote33

Sample and recruitment

The sample criteria for this study included female soccer players who at the time of the interview were at least 22 years old, had been playing for the Swedish premier league for at least 3 years, and had been selected for the Swedish senior national soccer team. These criteria were chosen to include adult soccer players, who had experienced, achieved and remained in the highest level of soccer and could thus describe and discuss career paths from child to an adult professional soccer player. At the time of this study, a total number of 23 players fulfilled these criteria. To recruit individuals from this population, we obtained relevant player contact details through a personal contact of the main author. Second, once contact details were received, individual players were contacted via email and provided project and project team information, presentation of the research team, ethical safeguarding, and a consent form. Seven players were contacted and all agreed to participate in the study.

provides information on the seven players’ background information.

Table 1. Sample of players included in the study.

Data production

This study adopted two research methods: semi-structured interviews and biographical mapping. Interviews were chosen in order for players to recount their career journeys as they had experienced them. The biographical mapping tool was adopted and adapted in order to gain a visual representation of the players’ career paths.Footnote34 The first author of this study conducted all interviews.

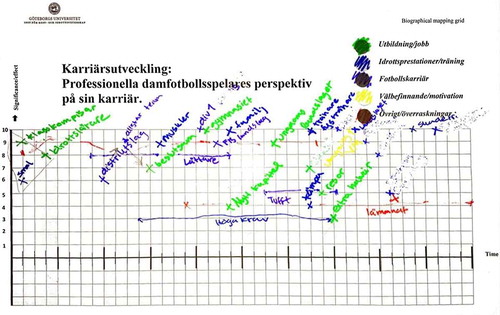

A pilot interview with an elite–level soccer player was held to test the interview procedure. The interviews began with an introduction of the interview process, ethical principles and an overview of the interview content. The questions that followed this introduction were guided by an interview schedule, which included four topical questions: (1) When you look back at your career, how would you describe it?; (2) Could you describe what made you enter soccer?; (3) How come you decided to pursue soccer to higher levels?; and (4) When did you decide to become a professional soccer player, and how come you made that decision at that point? Following this section of questions, the interviewees were asked to plot experiences on the biographical mapping tool and to grade them according to time and the effect or significance (scale 1–10; 1 = less important, 10 = very important). The grid covered five themes: education, sport performance/physical training, soccer career, motivation/well-being and surprises/unexpected events (see ). During the plotting process, a discussion between the interviewer and interviewee took place to clarify the players’ mapping of their experiences.

The interviews were held during one week of 2016 at a place convenient to the players. The duration of the interviews varied from 60 to 120 min. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and the names of all interviewees were replaced with pseudonyms.

Data analysis procedure

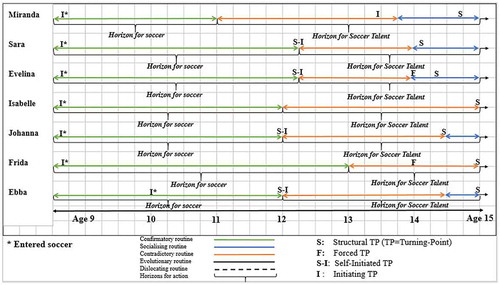

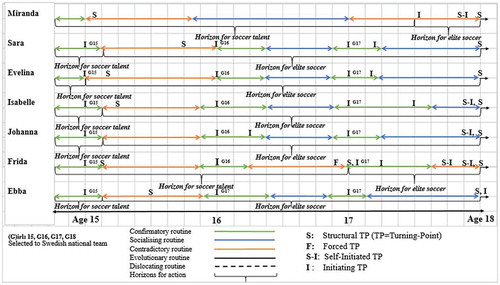

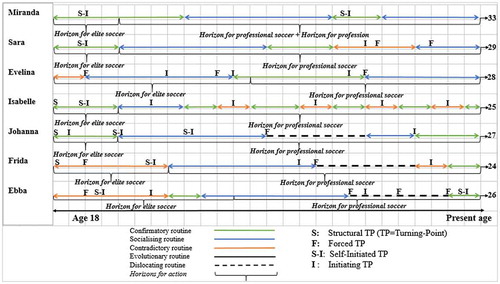

Data were analysed along a theoretical thematic analysis procedure.Footnote35 Three steps were taken, during which Hodkinson and Sparkes’ careership theory was employed as a frame of reference: First, the transcribed data were analysed thematically in order to notice routines during the players’ childhood, youth and adulthood.Footnote36 To achieve this, transcripts were carefully read several times to condense the data into routines. These routines were then reviewed to identify chronological career phases. Three phases could be identified: (a) child soccer dreams; (b) preparation for a professional soccer career; and (c) professional soccer career. Second, the biographical mapping data were analysed based on the types of routines and turning points the careership theory outlines.Footnote37 This procedure involved three steps: (1) Turning points were identified and organized according to the timeline of the grid (childhood, youth, present); (2) Turning points were related to one of the three routines identified through the thematic analysis; and (3) Turning-point patterns were identified within each career phase. Third, routines and turning points were discussed between the two authors and presented within a draft report. Fourth, the turning points and subsequent routines were related to the players’ future perspectives, which allowed the identification of ‘horizons for action’. These horizons – ‘horizon for soccer’, ‘horizon for soccer talent’, ‘horizon for elite soccer’ and ‘horizon for professional soccer’ – were attached to a routine in order to demonstrate how the players’ future perspective was affected.

Women’s highest-level football players’ career paths

We present the results according to the four horizons we identified. Within each of these sections, we describe the routines and turning points the players recounted. Representative quotes, which we have translated from Swedish to English, are included throughout. Three figures are included and referred in order to visually clarify the players’ career paths. Where we mention a particular horizon, turning point or routine, a reference that aids identification on the included grids is provided in brackets.

Horizon for soccer

This career phase refers to the players’ entrance into soccer, and how their career paths developed along their compulsory education from age 9 to age 15. All players described their childhood as a memorable time. They described being introduced to soccer in school through playing during breaks. Family members, friends or teachers then introduced them to clubs. The players’ fun experiences of soccer developed a strong passion for the sport and created their first ‘horizon for action’, ‘horizon for soccer’. The routine that followed, which consisted of school, spare-time and playing within a club community, can be understood as a confirmatory routine, during which their decisions to enter soccer were reinforced.

The decision to enter a club can be seen as an initiating turning-point, an event Barker-Ruchti and colleagues found to have shaped women’s soccer coaches’ entrance into coaching.Footnote38 The initiating turning-point means neither a self-initiated nor a forced turning-point, but a combination as it was made possible with the help of others. What is interesting is that none of the seven players were selected through talent identification and promotion programmes. This raises significant questions about the utility of such selection procedures.Footnote39 In Sweden, Peterson is particularly critical of this country’s selection system, arguing that players are being selected out, rather than developed.Footnote40 According to this research, players reach the highest level of soccer despite selection procedures, not thanks to the system.Footnote41

At the age of 11 to 12, the players entered a contradictory routine. A contradictory routine means that an individual’s experiences are in some way not suitable any longer.Footnote42 This routine began as the players increasingly felt that their current teams no longer fit their soccer ambitions. The players suggested that they lacked challenges at their local club and in response, sought soccer environments that would satisfy their ambitions.Footnote43 Johanna recounted:

I thought soccer was fun and I wanted a challenge. I transferred to another club when I was about 12, and it was about then that I both knew and made the decision to pursue soccer. It was at that time many started dropping out so …

As the players entered secondary (soccer) schools and moved to higher level clubs (Swedish divisions 1 and 2) or premier league teams, they were faced with increased educational, training and commuting demands (this latter point applied to three of the seven players). The interviewees described how they perceived this situation as stressful, but reinforced their horizon for soccer talent.

Horizon for soccer talent

In response to the difficulties in combining school and high-level soccer, the players progressively focused less on achieving in school. Ebba and Frida, for instance, described how studying felt as to contradict their soccer ambitions. Ebba said:

… I felt that in secondary school, I put too much time in good grades in order to get into high school. But I believe I would have been accepted without straight As and Bs in everything … I became tired of school … I didn’t have that much energy …

I fought for good grades which was actually no use doing. I could have saved energy for high school instead so I focused on managing school after that, and that was it.

At age 15, upon achieving a club transfer and acceptance into a soccer high school, the players’ decisions to focus on elite soccer was confirmed and a horizon for high-level soccer shaped their career vision. However, the age of 15–16 was described as a forced turning point phase because of the difficulties athletes experienced in balancing and differentiating training demands, performance outcomes, and their personal and educational lives.Footnote45 For the players of this study, this forced turning point also included increasingly more pressure due to selection procedures. Evelina elaborated:

The first year in high school went okay, but when I signed for a club in premier league and played for the national team as well, I started to miss out some stuff in school. But, it was a soccer program so it was okay anyway to miss due to training camps. You could see that clearly on my grades though.

When I was about 15, I was selected for the national team and a premier league U-team. It was a stressful time and I remember I lost control a bit there and almost suffered a physical and mental burn-out. I was not able to combine all trainings I had to attend and in the end, it became too stressful. I remember my parents noticed and commented on this, even though I was not aware of this at the time.

In addition to their perception of deficient fitness, the players were introduced to an environment where only a selected group of players were given game time.Footnote47 In order to achieve game time, the players felt that they must reach the expected levels of fitness, which gave them the determination to invest in their fitness, and thus in their horizons for elite soccer.

Horizon for elite soccer

At the age of 16 to 17, all players stated that they continued to prioritize soccer over education. Athlete development literature outlines the years from 16 and over as an investment phase, during which athletes must increasingly focus on sport and train extensively.Footnote48 For the participants of this study, this was true as their focus and commitment increased further from the previous routine. Johanna described how the time spent training and competing barely allowed her to focus on school, which her deteriorating school grades began to reflect. This is a common behaviour regarding elite athletes.Footnote49 Carless and Douglas describe this behaviour with the concept of ‘performance narrative’, which refers to behaviours that prioritize sport over other areas of life (e.g. education).Footnote50 Johanna and five other players described this behaviour as they spoke of how their horizons for elite soccer dominated their lives. Johanna said:

… I missed a lot in school … you could see that on my grades. It did not bother me, as long as I passed, I felt okay. I found out at my graduation though that I failed one subject and had to read that later.

Around this time of settling into elite soccer, all players were offered higher level club contracts (, I). These offers followed a number of selection try-outs. The players again felt that accepting the higher level club offers was natural, however, this time, their acceptance also meant that they had to leave an appreciated school environment, close classmates and family. Thus, although the routine that followed was confirmatory, it was also socializing as the players had to adapt to new contexts and form new athletic goals (, Blue line age 16–17). Their quick and unproblematic adjustment to the new contexts, however, suggests that the players were able to draw on their previous transfer experiences to settle into the new elite environment. Isabelle said:

I knew it was going to be tough in order to get a start position since I was young. Of course, it was hard to leave friends and family behind, but I knew what I wanted for my soccer and in order to accomplish this the decision was obvious to make.

Horizon for professional soccer career

Upon becoming professional footballers, the players’ career pathways took on rather different directions (, age 18). The three players that could sustain their lives through their soccer salaries (Isabelle, Johanna and Sara), could finally focus on soccer only and thus experienced a confirmatory routine (, Green line, age 18). Sara elaborated on her life as a professional soccer player after school:

Well, regarding my career beside soccer I am almost embarrassed since it really does not exist. Although, I was very happy and relieved to graduate. I decided to only focus on soccer which I did and it felt great.

Actually, I think it is terrifying to even consider what is coming up after my soccer so I try not to think about it.

Johanna and Miranda were the only two players that applied for university education upon leaving high school. Miranda’s educational choice included transferring to another club (, S-I and S). She was able to study alongside her soccer career, which she still does today:

I actually didn’t know that it even existed (education program) but he (family member) gave me the tip to apply there and I thought that he might have seen something in me that made him think I should apply … When I started and understood what it was, I felt it was right from the start and it was great. It is a very important part of my life that I started studying there immediately after high school.

I started at a [professional] program, but it was tricky to combine with the soccer. It felt like it was something that I could do, but it was so much practice within the education and it did not work out with my soccer and I chose soccer.

Everything struck me quite fast, and I had just got the idea of quitting soccer as the club started to give me more game time. So I stayed for a year and then signed for a club in another country.

I was away for almost a year because of my knee injury. Even though my rehab progressed I missed the European Championship which was the worst thing ever.

The training benefitted my fitness and it is sad that I had not thought of that at a younger age. The training at the gym both during and between injuries was effective and I took it very seriously in order to remain healthy.

The four horizons point to four specific career phases that the players experienced in rather similar ways. In the following, we would like to take a broader perspective to consider this homogeneity because it contradicts existing literature that outlines how soccer players develop elite careers in myriad complex ways.Footnote54

Broader considerations

We offer the following considerations: First, the structural turning points the players experienced reflect Sweden’s school transitions from primary, upper secondary and high school and the Swedish Football Federation’s soccer stages (G15–G19). Certainly, Swedish children uniformly move through the education stages and many Swedish soccer players go through the age-specific career stages set by the Swedish Football Federation. With respect to our sample, both education and soccer turning points can be seen to have shaped the horizons of soccer we identified through this research. These horizons uniformly became more soccer focused as the players grew older and moved through the national soccer stages. The horizons, however, did not only increase in intensity because the Swedish school and sport system provided suitable development structures. The horizons for soccer also intensified as they conflicted with education. This mainly occurred because the players struggled to manage the increasing school and soccer demands. As this occurred, and the players’ horizons for soccer became increasingly more meaningful, they chose to prioritize sport over education. Upon leaving school, the players had not developed a dual career vision and thus did not continue their education. A number of scholars have demonstrated how athletes adopt a performance orientation to create ‘performance narratives’.Footnote55 Within sport, this narrative is accepted (and even expected). However, research also points to the problems athletes may face if they only develop an athletic identity and are unable to move into non-sporting working contexts.Footnote56 In Sweden, the lack of professional development outside of sport conflicts with this country’s sport/school system intending to create dual careers.

Second, the identified forced turning points relating to injuries reflect the increasing intensity of training and competition level. Ample research outlines how with increased training and competition, especially during teenage years, the risk for injuries increases significantly.Footnote57 For the players of our sample, this was the case. As they entered a sport secondary school, their training schedule increased and they felt physically ill-prepared for this intensity. However, it is also possible to say that the players experienced difficulties because the clubs and schools did not provide adequate fitness progression. As their horizon for soccer was already developed and in order to cope with the convoluted school and training schedule, they were prepared to put in extra training hours to reach the required physical fitness level. As outlined above, this extra focus on soccer further supported their horizon for soccer and reduced their focus on education. However, these experiences suggest that the transition from lower level school and soccer to a dual career soccer/school situation must be considered carefully so that injuries can be prevented and a dual career vision maintained.

Conclusion

The aims of this study were to examine how women soccer players develop and experience careers. We focused on how seven women experienced childhood and youth soccer, if they considered a professional career at this early age, and how structural and contextual factors such as school and training demands implicate career development. In employing the theory ‘careership’, the results of this study show that the players enjoyed childhood soccer participation and developed meaningful horizons for soccer during this time. This horizon allowed them to see a soccer future and strategically develop their soccer career paths. As the players were selected into higher level teams, their early horizon for soccer was confirmed with a horizon for soccer talent. This horizon coincided with entering a soccer secondary school. The combination of high-level soccer and increased educational demands, however, was experienced as problematic because it created a convoluted schedule. The players did not question this loading, but felt that they were physically ill-prepared for the demands. In response, they increased their training by going to fitness gyms, and reduced their focus on education. This intensified their horizon for soccer, but also resulted in a number of injuries. Thus, despite their dual career situation, the players did not develop equally in soccer and education, but rather, prioritized soccer over education.

Our results suggest that the Swedish dual career concept and practice may not have the desired effect of athletes equally developing their education and sport. We recommend that sport organizations and sport schools carefully consider the demands they place on their student athletes and the potential consequences for both their health and educational achievements, and outlook this may have.

We propose that the use of the theory of careership has been useful to understand how early career experiences set career paths, and how structural and contextual factors confirm, but also complicate underlying career horizons. The four horizons of soccer we identified provided a generative way to understand how the girls and later young women understood soccer and the meaning this had for themselves and their careers. Lastly, careership was further useful in identifying a variety of turning points and to understand how these implicate career development (i.e. career routines). We hope that others will also employ this theory to extend knowledge on sport career development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We send our gratitude to the participants of this study, and other contributors from the SWEDISH FOOTBALL FEDERATION, and the Football Federation of Gothenburg. We also thank the two reviewers for their positive feedback.

Notes

1. FIFA, Women’s Football Today, 1–220.

2. FIFA, “Big Count”, 13.

3. UEFA, Women’s Football Association, 3–11.

4. FIFA, Women’s Football.

5. UEFA, Women’s Football Development, 4.

6. FIFA, Women’s Football.

7. Ibid., 61.

8. Sankala, Fotboll i grundskolan.

9. EU Guidelines of Dual Careers; Stambulova et al., “Dual Career Experiences,” 4–14.

10. Mika Sankala, Responsible for Sport Schools at Swedish Sport Association, 26 April 2016.

11. Swedish Sports Confederation, Idrotten i siffror 2014, 1–13.

12. Stambulova et al., “Dual Career Experiences”, 4–14; Stambulova et al., “Career Development and Transitions”, 395–412; Stambulova and Ryba, Athletes’ Careers Across Cultures; Stambulova and Alfermann, “Career Development and Transition”, 292–308.

13. Peterson, “Talangutveckling eller talangavveckling,” 15–38.

14. Stambulova et al., “Dual Career Experiences,” 4–14.

15. SvFF, Analys av damallsvenska klubbarnas ekonomi, 4.

16. Swedish Sports Confederation, Idrotten i siffror 2016, 6; Stambulova et al., “Dual Career Experiences,” 4–14.

17. Billing, Franzén and Peterson, “Paradoxes of Football Professionalization,” 82–99.

18. Eliasson, “Gendered Socialisation in Football,” 820–33. For similar results, see Themen, “Female Football Players in England.”

19. Gledhill and Harwood, “Career Development in Soccer,” 65–77.

20. Botelho and Agergaard, “International Football Migration,” 806–19.

21. Coupland, “Embodied Career Choice,” 111–21; Schlossberg, “Model of Human Adaptation,” 2–18; Stambulova et al., “Career Development and Transitions,” 395–412; Stambulova and Ryba, Athletes’ Careers Across Cultures; Stambulova and Alfermann, “Career Development and Transition,” 292–308.

22. Cunningham et al., “Social Cognitive Career Theory,” 122–38; Coupland, “Embodied Career Choice,” 111–21.

23. Hodkinson and Sparkes, “Careership,” 29–44; Ramirez et al., “Physical Activity Behaviour,” 303–10.

24. Hodkinson and Sparkes, “Careership,” 29–44.

25. Ibid., 33.

26. Ibid., 38.

27. Ibid., 29–44.

28. Ibid., 29–44.

29. Ibid., 40–41.

30. Barker-Ruchti and colleagues, 117–31; Allin and Humberstone, “Careership in Outdoor Education,” 135–53.

31. Allin and Humberstone, “Careership in Outdoor Education,” 135–53.

32. Barker-Ruchti and colleagues, 117–31.

33. Swedish Research Council Document.

34. Thiel et al., “German Young Olympic Athletes,” 1–10.

35. Thomas, “Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data,” 237–46.

36. Braun and Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis,” 77–101.

37. Henry, “Analysis of Decision-Making,” 293–316.

38. Barker-Ruchti and colleagues, 117–31.

39. Güllich, “Selection, in German Football,” 530–37.

40. Peterson, Talangutveckling eller talangavveckling, 131–2.

41. Ibid., 99–101.

42. Hodkinson and Sparkes, “Careership,” 38.

43. Debois et al., “Lifespan Perspective on Transitions,” 660–8.

44. EU guidelines of Dual careers, 1–40; Mika Sankala, Responsible for Sport Schools at Swedish Sport Association, 26 April 2016.

45. Ryba, Ronkainen and Selänne, “Elite Career as Context,” 47–55.

46. Güllich and Eimrich, “Considering Long-term Sustainability,” S383–97.

47. Hornig, Aust and Güllich, “Development of Top-level Football,” 96–205.

48. Hornig, Aust and Güllich, “Development of Top-Level Football,” 96–205.

49. Ryba, Ronkainen and Selänne, “Elite career as context,” 47–55.

50. Carless and Douglass, “Narratives and Career Transition,” 51–66.

51. Hodkinson and Sparkes, “Careership,” 29–44.

52. Stambulova et al., “Searching for Optimal Balance,” 4–14.

53. Ibid., 111–21.

54. Güllich and Eimrich, “Considering Long-Term Sustainability,” S383–97.

55. Douglas and Carless, “Performance, Discovery and Narratives,” 14–27; EU Guidelines of Dual Careers, 1–40.

56. Park, Lavallee and Tod, “Athletes’ career transitions,” 22–53.

57. Brümann and Schneider, “Sport injuries,” 597–605.

References

- Allin, L., and B. Humberstone. “Exploring Careership in Outdoor Education and the Lives of Women Outdoor Educators.” Sport, Education and Society 11, no. 2 (2006): 135–153.10.1080/13573320600640678

- Barker-Ruchti, N., E.-C. Lindgren, A. Hofmann, S. Sinning, and C. Shelton. “Tracing the Career Paths of Top-Level Women Football Coaches: Turning Points to Understand and Develop Sport Coaching Careers”. Sports Coaching Review 2(3) (2015): 117–131.

- Billing, P., M. Franzén, and T. Peterson. “Paradoxes of Football Professionalization in Sweden: A Club Approach.” Soccer & Society 5, no. 1 (2004): 82–99.10.1080/14660970512331391014

- Botelho, V. L., and S. Agergaard. “Moving for the Love of the Game? International Migration of Female Footballers into Scandinavian Countries.” Soccer & Society 12, no. 6 (2011): 806.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101.10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brühmann, B., and S. Schneider. “Risk Groups for Sports Injuries among Adolescents – Representative German National Data.” Child: Care, Health and Development 37, no. 4 (2011): 597–605.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. “We Haven’t Got a Seat on the Bus for You’ or ‘All the Seats Are Mine: Narratives and Career Transition in Professional Golf.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 1, no. 1 (2014): 51–66.

- Coupland, C. “Entry and Exit as Embodied Career Choice in Professional Sport.” Journal of Vocational Behaviour 90 (2015): 111–121.10.1016/j.jvb.2015.08.003

- Cunningham, G. B. J. Bruening, M. L. Sartore, M. Sagas, and J. S. Fink. “The Application of Social Cognitive Career Theory to Sport and Leisure Career Choices.” Journal of Career Development 32, no. 2 (2005): 122–138.10.1177/0894845305279164

- Debois, N., A. Ledon, C. Argiolas, and E. Rosnet. “A Lifespan Perspective on Transitions during a Top Sports Career: A Case of an Elite Female Fencer.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 13, no. 5 (2012): 660–668.10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.010

- Douglas, K., and D. Carless. “Performance, Discovery, and Relational Narratives among Women Professional Tournament Golfers.” Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal 15, no. 2 (2006): 14–27.10.1123/wspaj.15.2.14

- Eliasson, I. “Gendered Socialization among Girls and Boys in Children’s Football Teams in Sweden.” Soccer & Society 12, no. 6 (2011): 820.10.1080/14660970.2011.609682

- EU. 2012. “EU Guidelines on Dual Careers of Athletes.” Accessed April 25, 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/documents/dual-career-guidelines-final_en.pdf

- FIFA. 2014. “Women’s Football Survey.” Accessed September 13, 2016. http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/footballdevelopment/women/02/52/26/49/womensfootballsurvey2014_e_english.pdf

- FIFA. “FIFA Magazine: Big Count 2007.” Accessed March 14, 2016. http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/fifafacts/bcoffsurv/emaga_9384_10704.pdf

- FIFA. “Women’s Football.” Accessed March 23, 2016. http://www.fifa.com/womens-football/mission.html

- FIFA. “Women’s Football Today.” Accessed September 13, 2016. http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/afdeveloping/women/93/77/21/factsheets.pdf

- Gledhill, A., and C. Harwood. “A Holistic Perspective on Career Development in UK Female Soccer Players: A Negative Case Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 21 (2015): 65–77.10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003

- Güllich, A. “Selection, De-Selection and Progression in German Football Talent Promotion.” European Journal of Sport Science 14, no. 6 (2014): 530–537.10.1080/17461391.2013.858371

- Güllich, A., and E. Emrich. “Considering Long-Term Sustainability in the Development of World Class Success.” European Journal of Sport Science 14, no. sup1 (2014): S383–S397.10.1080/17461391.2012.706320

- Hartmann-Tews, I., and G. Pfister. Sport and Women Social Issues in International Perspective. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Hemgren, L.-E., and U. Forsberg. “Svenska Fotbollsförbundets Elitläger.” Accessed May 7, 2016. http://fogis.se/barn-ungdom/elitlager/

- Henry, J. “Return or Relocate? An Inductive Analysis of Decision-Making in a Disaster.” Disasters 37, no. 2 (2013): 293–316.10.1111/disa.2013.37.issue-2

- Hodkinson, P., and A. C. Sparkes. “Careership: A Sociological Theory of Career Decision Making.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 18, no. 1 (1997): 29–44.10.1080/0142569970180102

- Hornig, M., F. Aust, and A. Güllich. “Practice and Play in the Development of German Top-Level Professional Football Players.” European Journal of Sport Science 16, no. 1 (2016): 96–105.10.1080/17461391.2014.982204

- Park, S., D. Lavallee, and D. Tod. “Athletes’ Career Transition out of Sport: A Systematic Review.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 6, no. 1 (2013): 22–53.10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053

- Peterson, T. Talangutveckling Eller Talangavveckling?. Holmbergs, Malmö: SISU idrottsböcker, 2011.

- Ramirez, E., P. Hodges Kulinna, and D. Cothran. “Constructs of Physical Activity Behaviour in Children: The Usefulness of Social Cognitive Theory.” Psychology of Sport & Exercise 13, no. 3 (2012): 303–310.10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.11.007

- Ryba, T. V., N. J. Ronkainen, and H. Selänne “Elite Athletic Career as a Context for Life Design.” Journal of Vocational Behaviour 88 (2015): 47–55.

- Sankala, M. “Fotboll I Grundskolan.” Accessed 19 April, 2016. http://fogis.se/fotboll-i-skolan/fotboll-i-grundskolan/

- Schlossberg, N. K. “A Model for Analyzing Human Adaptation to Transition.” SAGE Social Science Collections 9, no. 2 (1981): 2–18.

- Schostak, J. Interviewing and Representation in Qualitative Research. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2006.

- Stambulova, N. 2016. “‘Athletes’ Transitions in Sport and Life from: Routledge International Handbook of Sport Psychology Routledge.” Accessed June 22, 2017. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315777054.ch50

- Stambulova, N. B., and D. Alfermann. “Putting Culture into Context: Cultural and Cross‐Cultural Perspectives in Career Development and Transition Research and Practice.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 7, no. 3 (2009): 292–308.10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671911

- Stambulova, N. B., and T. V. Ryba, eds. Athletes’ Careers across Cultures. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Stambulova, N., D. Alfermann, T. Statler, and J. Côté. “ISSP Position Stand: Career Development and Transitions of Athletes.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 7, no. 4 (2009): 395–412.10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671916

- Stambulova, N. B., C. Engstrom, A. Franck, L. Linnér, and K. Lindahl. “Searching for an Optimal Balance: Dual Career Experiences of Swedish Adolescent Athletes.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 21 (2015): 4–14.10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.009

- Swedish Football Federation. “Analys Av Damallsvenska Klubbars Ekonomi 2016.” Accessed June 24, 2017. http://d01.fogis.se/svenskfotboll.se/ImageVault/Images/id_155646/scope_0/ImageVaultHandler.aspx170614160510-uq

- Swedish Research Coundcil. “Forskningsetiska Principer Inom Humanistisk-Samhällsvetenskaplig Forskning.” Accessed July 6, 2017. http://www.codex.vr.se/texts/HSFR.pdf

- Swedish Sport Confederation. “Idrotten I Siffror 2014.” Accessed December 13, 2016. http://www.rf.se/ImageVaultFiles/id_63562/cf_394/RF_i_siffror_2014.PDF

- Swedish Sport Confederation. “Idrotten I Siffror, 2016.” Accessed June 25, 2017. http://www.rf.se/globalassets/riksidrottsforbundet/dokument/statistik/idrotten_i_siffror_rf_2016.pdf

- Themen, K. “Female Football Players in England: Examining the Emergence of Third-Space Narratives.” Soccer & Society 17, no. 4 (2016): 433–449.10.1080/14660970.2014.919273

- Thiel, A., K. Diehl, K. E. Giel, A. Schnell, A. M. Schubring, J. Mayer, S. Zipfel, and S. Schneider. “The German Young Olympic Athletes’ Lifestyle and Health Management Study (GOAL Study): Design of a Mixed-Method Study.” BMC Public Health 11, no. 1 (2011): 400–410.

- Thomas, D. R. “A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data.” American Journal of Evaluation 27, no. 2 (2006): 237–246.10.1177/1098214005283748

- UEFA. “Women’s Football across the National Associations 2014–2015.” Accessed March 2, 2016. http://www.uefa.com/MultimediaFiles/Download/Women/General/02/03/27/84/2032784_DOWNLOAD.pdf

- UEFA. “Women’s Football across the National Associations 2015–2016.” Accessed March 20, 2016. http://www.uefa.org/MultimediaFiles/Download/OfficialDocument/uefaorg/Women’sfootball/02/30/93/30/2309330_DOWNLOAD.pdf

- UEFA. “Women’s Football Development Programme & Free-Kicks.” Accessed September 19, 2016. http://www.uefa.org/MultimediaFiles/Download/Women/General/02/26/30/64/2263064_DOWNLOAD.pdf