ABSTRACT

Primary data was used to analyse the views and opinions held by Pakistani-Scots in Greater Glasgow, Scotland, about whether they prefer Celtic or Rangers Football Clubs. The question is important, sociologically, due to Celtic’s Irish-Catholic-Republican sympathies and Rangers’ British-Loyalist-Unionist perspective, neither of which seems to naturally gel with the Muslim orientation of Glasgow’s Pakistanis (8.1% of the city’s population). The research method was a survey of 51 respondents, all ethnic-Pakistanis ordinarily resident in Greater Glasgow, and a total of 5 interviews. Results reveal that the majority of survey respondents prefer Celtic over Rangers and 86% would support a new Asian/Muslim club. But how it would be formed, whether all players would be Asian, and how it would be received were all hotly-debated topics.

Introduction

Celtic and Rangers are the two most successful football clubs in Scotland. Both are based in Glasgow, Scotland’s most populous city, and their encounters in the ‘Old Firm’ derby have often been marred by sectarian behaviour due to the division between Celtic’s Irish-Scot, mostly Roman Catholic, supporters (Irish nationalists) and Rangers’ Scottish-Protestant supporters (traditionally British Unionists who support the literal union of Great Britain and Northern Ireland).Footnote1 In fact, it was as late as 1989 that Rangers signed its first high-profile Catholic player, the ex-Celtic star Maurice ‘Mo’ Johnston.Footnote2

Nowadays, Glasgow’s Southside has a major Pakistani presence, especially the localities of Pollokshields and Govanhill. The Pakistanis could now be regarded as Glasgow’s third social force or demographic after native Protestant-Scots and Irish-Catholics.Footnote3 Celtic and Rangers should reach out to this local Pakistani community (8.1% of Glasgow’s population) so as to increase season-ticket and merchandise sales, as well as for the sake of attracting more Asian players, which might then feed back positively into those other areas.

The three research questions posed by this study are as follows: (1) Do Glasgow Pakistanis support Celtic or Rangers and why? (2) What are the experiences of Pakistanis with Celtic and Rangers fans? And (3): Would the Pakistani community in Glasgow support the creation of an Asian/Muslim club? We distributed a survey with the aim of gaining more information on the views and opinions held by the Pakistani community in Greater Glasgow about these research questions. We also conducted five interviews. We collected primary data in January 2019, before the massive improvement demonstrated by Rangers in the 2020/21 season, both in the Europa League and the Scottish game. In fact, Rangers won the Premiership title with a few games left to play, unbeaten, and with a record low goals-conceded tally. We thought it only fair to mention Rangers’ improvement, and suggest that if data had been collected this season, it might have revealed more support for Rangers because ‘everyone loves a winner’. But we don’t think that the main findings of this study would have changed.

This project should be viewed as a pilot study on an interesting and important topic. A major limitation of the study is the small sample size of 51 survey respondents. This was unavoidable due to time and money constraints on the project plus the fact that the sample could only include people of Pakistani heritage ordinarily resident in Greater Glasgow.

History of the Old Firm

Introduction to Celtic and Rangers

Although many non-attendees still view Old Firm games through a sectarian prism, as an acting out of outdated attitudes, living in the Glasgow bubble affects everyone like a thick fog. Few claim to be ignorant of major events and the Old Firm dominates media coverage and regular conversations. Once you choose a side, and even if you don’t, the heady atmosphere, especially on Derby days, impacts on everyone. In the white working-class areas, in particular, Rangers and Celtic shirts are worn in all seasons and on all days of the week and very often the shirt signifies more than a football club. The wearer of the shirt’s beliefs about history, religion, nationalism, ethnicity, and politics are proudly on display, and the swagger and emission of aggression are usually very obvious and meant to be obvious. The message is clear: ‘These are my beliefs, conform or step out of the way.’ As Fillis and Mackay write, about a club’s scarf, a shirt, too, is a ‘tool for communicating values’.Footnote4 For at least some of these people, they are making a statement about political or ethnic beliefs, as acted out (in their opinion) through the actions of their football team. Even mild-mannered Steven Gerrard (Rangers’ manager/ex-Liverpool) has struggled to maintain his composure and perspective, at times, as his sideline angst and press conference facial expressions make clear.

Rangers football club

Rangers Football Club, sometimes known as Glasgow Rangers, was established in 1872 and it has won more silverware than any other team in Scotland.Footnote5 Up until the northern summer of 2021, Rangers had won 55 league championships, 33 Scottish Cups, and 27 Scottish League Cups. In Europe, however, Rangers has had less success as it has only won one trophy in the form of the Cup-Winners’ Cup of 1972.Footnote6 In 2012, the company behind the club, The Rangers Football Club plc, was liquidated following an April 2010 demand by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) that Rangers pay it £27.4 million for allegedly unpaid Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) and £9.2 million for National Insurance Contributions (NICs), as well as £9.6 million from four Murray Group companies (connected to the Chairman Sir David Murray).Footnote7 In fact, the Scottish Premier League (SPL) rejected the new company receiving the old company’s share, meaning that re-admittance was blocked.Footnote8 Nine days later, the Scottish Football League (SFL) decided to allow Rangers to be admitted into the Third Division, i.e. what is now League Two.Footnote9 Finally, in 2016, the club returned to the top-tier of the Premiership after sealing a third promotion following an eventful journey.Footnote10

Celtic football club

Celtic Football and Athletic Club was established in 1887 by Brother Walfrid who was a Marist and the headmaster of the Sacred Heart School based in Glasgow’s East End.Footnote11 The club was first established as a charity to provide meals for deprived Irish immigrants who were living in the slums of the East End of Glasgow.Footnote12 Like its rivals, Celtic has acquired plenty of silverware over the years as it has won the Scottish Premiership/ First Division title 51 times as well as winning 40 Scottish Cups and 19 Scottish League Cups. However, the main highlight of success for Celtic came in 1967 when it won the European Cup Final in Lisbon with a squad whose members were all born within 30 miles of Celtic Park.Footnote13

Literature review

Immigration of Asians to Scotland

In the 1950s and 1960s, many new residents, of Pakistani origin, settled in the larger urban commercial centres, most notably Glasgow and Edinburgh.Footnote14 Maan reported that the overall number of Pakistani and Indian residents in Scotland, along with their children born in Scotland, was around 16,000 by 1970.Footnote15 As reported in the 1991 Census, the Pakistani population in Scotland (21,230) was (and is) scattered across many different Scottish regions. As at 1991, 69 percent (14,650) of the Pakistani population lived in the Strathclyde region and most in the city of Glasgow. And 15.4 percent (3,270) of the Pakistani population lived in the Lothian region, with a great number of these residing in Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital. The leaders of the Pakistani community in Edinburgh reckon that the overall number of Pakistani residents in the Lothian region had increased to around 5,500–6,500 by 2000.Footnote16

Muslim integration

Berry put forward integration as being one out of the four modes of acculturation alongside assimilation, separation, and marginalization.Footnote17 He claimed that integration is a mode whereby an individual attempts to retain her/his ‘own’ culture and the host-culture. With assimilation, a person rejects her/his primary culture and embraces the host-culture. On the other hand, with separation, an individual continues to have a connection with her/his primary culture and ignores any type of contact with the host culture. Lastly, marginalization is when a person has lost interest in retaining her/his culture and, at the same time, has little or no interest at all in, or involvement with, the host-culture. Regarding these four modes, Berry stated that a person feels less stressed and adjusts to life better when using integration to acculturate. Adversely, in marginalization, a person feels more stressed and adjusts to life poorly or sometimes not at all in the host-society. Berry also stated that assimilation and separation sit between integration and marginalization.

Many researchers have used Berry’s acculturation model to gain a better understanding of Muslim acculturation in different Western countries. For example, Saroglou and Mathijsen, when creating comparisons on how Muslim and non-Muslim immigrants in Belgium formed various identities and acculturated, found that the integration mode is in operation with respect to Belgian and European identity but not with both groups’ country of origin.Footnote18

The research about Muslim integration in the UK has produced differing findings. Although some results show that much resistance exists, other research shows that there is a desire to be integrated. However, when looking at this research, we notice that these differing results can be caused by the differences in methods and samples. The research which indicates that Muslims are willing to integrate is based on primary accounts of Muslims themselves. The information from official reports and sources, on the other hand, has been collected by non-Muslims. We now will discuss examples of both types of research.

With regards to the research about Muslims looking to integrate, it is clear that Muslims do not dismiss this idea, but the way in which they look at it can be complex. From the perspective of Muslim Arabs in the UK, Nagel and Staeheli studied the procedures associated with integration and segregation.Footnote19 They came to the conclusion that this group views interaction with the host-society as essential but, rather than looking at integration as ‘social cohesion’, they view it to as a discourse between diverse-but-equal communities occupying the same geographic space. Similarly, Maxwell discovered that Muslims in Britain identify themselves as being British, and what it means to be British, in the same way as other groups.Footnote20 Furthermore, discrimination was a factor in the creation of their identities above all other socio-economic factors. Maxwell also claimed that despite most of the Muslims living in segregated neighbourhoods, they would still consider themselves as being part of the British community, on the whole, due to their integrated networks

By contrast, research involving the use of national statistics data and research conducted by non-Muslims produces different results. Bisin et al. produced results which indicated in their opinion that despite the amount of time spent living in the UK; the Muslim immigrants did not forgo their religious identity.Footnote21 Bisin et al. came to the conclusion that the system by which Muslims integrate in the UK is in contrast to the general approach of UK policy regarding immigration, i.e. economic attainment and geographic homogenization. Therefore, by holding on to their religious identity, Muslim immigrants allegedly show more resistance to cultural-integration. But, for Joppke, the alienation perceived by Muslim immigrants in the UK is due to weaknesses in the government’s integration-policy.Footnote22 Vedder et al. complement this view by implying that failure to settle-in well is due to perceived discrimination.Footnote23 However, with their mixtures of ethnic and national identities, Muslims have been relatively successful in adapting to the British way-of-life.

There is clearly a need for additional research to be carried out, particularly on how Scottish Muslims integrate into society as there is a lack of research available on this topic. This study attempts to contribute to this research agenda, from the sociology of sport angle, by studying Pakistanis’ perceptions of Celtic and Rangers Football Clubs. We find that some reveal a preference for one of these clubs, in particular, whilst nearly all would support an Asian/Muslim club. This last-mentioned preference should not be viewed, simplistically, as its proponents being ‘less integrated’ than people supporting either Celtic or Rangers, given that football is a sport invented in Britain and integral to the British way-of-life. Both approaches represent alternative strategies for integration. Clearly, it would be unjust, in the specific Glasgow context, to deny Muslims their own club to support when Glasgow’s Catholics and Protestants have enjoyed, for over 120 years, a club made just for them, Using Marx’s theory of alienation, James and Walsh explain how the fans of Australian-based European ‘ethnic’ clubs, such as Melbourne Croatia and South Melbourne Hellas, feel alienated from football’s regulatory body due to the fact that ethnic clubs are unwelcome in Australia’s A-League (and cannot progress past the second-tier leagues).Footnote24

A limitation of the Berry model is that almost any approach to life can be called integration, given that assimilation, marginalization, and separation are all extreme positions.

Formulation of Muslim identity

Researchers have focused on the different patterns and elements of religious-identity formation among young Muslim immigrants. For example, Chaudhury and Miller explored the way in which young American Muslims, of Bangladeshi background, formed religious identities and argued that the population appeared to be comprised of two main groups.Footnote25 The first group was called ‘internal seekers’. These are the young Muslims who look into their faith to find answers. The second group was called ‘external seekers’. Here, the group look to other faiths beyond Islam to find answers. Other factors which contributed to their formations of identity were also revealed in this study. Praying five times a day; effective communication with family and friends; regular involvement in Muslim associations; and focusing on current religious practices to gain future rewards in life are such factors.

Similarly, Peek argued for a three-stage formation of religious identity among the young Muslim immigrants.Footnote26 He claimed that religion as an identity-marker was ascribed, chosen, and declared. The first stage informs us that Muslim children are mainly ascribed their religious identity. Next, following religious exploration, the child wilfully chooses to pursue that religion. Lastly, declared religious identity is based on an identity created after the 9/11 attacks in order to retain Muslim identity in the face of discrimination. The role of mosques in forming identity must also be taken into consideration and the way in which social control is managed through the teaching of the Al-Qur’an and Islamic principles.Footnote27

Forming identity may well be a stressful experience for first- and second-generation Muslim immigrants. In a study by Ostberg, young Norwegian-Muslims, from Pakistani backgrounds, needed to take part in identity negotiation during childhood and adulthood.Footnote28 He discusses the questions that are involved in this negotiation like ‘Who am I? What significance does being Muslim and Norwegian have? Which boundaries are negotiable and which are unimaginable to traverse?’ These negotiations are ongoing with parents and children, amongst siblings, and within peer groups.Footnote29

Research in the UK has shown that the trends on formation of identity are mixed. The feeling amongst Muslims living in Scotland of having a national and religious identity was studied by Hopkins.Footnote30 His research concentrated on two key aspects: being Muslim and being Scottish. Hopkins asserts that although there are pre-existing links to ethnic-culture, the Muslims favoured their Scottish identity as opposed to their British or ethnic one. He states that the primary reasons for this were that these Muslims were born-and-bred in Scotland, they have been educated here, and they speak with a Scottish accent. Hopkins also claims that their Scottishness has a connection with sports, especially football, and the England-versus-Scotland rivalry. However, another source finds that 93% of British-born Muslims identified their national-identity as British.Footnote31 Scottish identity may be viewed as preferable to British identity, whereas English identity might not be viewed in the same way.

The impact of culture and community involvement on young Pakistani individuals was analysed by Din.Footnote32 This author discovered that second-generation Pakistanis were in favour of having a British identity rather than a religious or ethnic one. Hyphenated identities, such as British-Asian, Scottish-Asian, and Pakistani-Scot, were revealed to be most common. The young individuals in Din’s research felt more connected and better adapted to the British way-of-life due to their language-skills, periods-of-stay, and employment. This ‘Britishness’ is represented by these second-generation Pakistanis’ appearances, the ways in which they socialized, and the ways they entertained themselves.Footnote33 The findings of this study have been corroborated by Ghuman, Kabir, Mir, and Modood.Footnote34

Ansari informs us that many young Muslims in Britain are seeking answers relating to where they belong, i.e. whether they are part of the Islamic community and/or the British one.Footnote35 He then states that they are improving their understandings of belonging in relation to nationality, ethnicity, and religion, and they are settling for the new approach of ‘being Muslim in Britain’. However, Jacobson argues that young British-Pakistani Muslims consider religious identity as being more essential compared to ethnic-identity due to the universality of religion.Footnote36 In addition, he claims that Muslims view nationalism as taboo, according to Islam, so express their devotion and feelings of belonging to a ‘Muslim Ummah’ (worldwide Muslim community). This was only partially confirmed by Saeed et al. who found that Scottish Muslims, when given the option, choose hyphenated identities.Footnote37 But, when they have to choose one option, they choose their Muslim identity as opposed to other identities.

Sectarianism and racism

The relationship (if any) between sectarianism and racism is complex. There are various different interpretations of the term ‘sectarianism’ in Glasgow and the rest of the West of Scotland. A narrow definition would see it as referring only to dislike and hostility between Protestants and Catholics. A wider definition, and this would be the normal understanding in the West of Scotland, regardless of how technically correct it might be, is that negative or hostile attitudes or actions directed towards Irish people and Irish republicanism, on the one hand, or the Union Jack, the Royal Family, and the British State, on the other, are sectarian. The reason is because of the historical link existing between Irish immigrants and Catholicism and, similarly, between British identification and Protestantism. This perspective ignores the presence in Scotland of both indigenous Scottish Catholics (let alone Polish Catholics) and Irish Protestants (of whom Jock Stein was one). Even more extreme is the idea that it is sectarian merely to adopt symbols or to have pride in an ethnic or religious heritage. Old Firm scholar Bill Murray even narrowed his definition of sectarianism in the revised edition of his book, in response to criticism.Footnote38 Originally, Murray seemed to proclaim that setting up a football club by and for Irish-Catholics was a sectarian action.Footnote39 Later, he argued, quite reasonably, that having no particular interest in Irish issues or culture is neither sectarian nor racist.Footnote40 By contrast, Gerry Finn saw sectarianism, in the historic concrete form it has adopted in Glasgow, and defined broadly, as being a type of racism, since the Irish were presented discursively as an inferior category of human beings and despised as a consequence.Footnote41 ‘Category’ here, for Finn, implies ‘race’ and racism, although the Irish and Protestant-Scots are both white peoples. Finn’s two fine contributions to The International Journal of the History of Sport in 1991 were echoed, in a whole-of-society context, by various contributors to Tom Devine’s 2000 book Scotland’s Shame?Footnote42 There were some who thought that the question-mark was far too kind!

A definition of racism which includes ‘sectarianism’ must be confusing to those who practice racist behaviour in the presence of what they perceive as people of other ‘races’.Footnote43 Then there are others who claim that, whilst the treatment of Rangers’ black champion, Mark Walters, at Celtic Park and Heart of Midlothian’s Tynecastle Stadium, was disgraceful racism, the hostility exhibited during Old Firm games, and towards Celtic and Hibernian manager, Neil Lennon, is merely sectarian banter. For some commentators, on the Protestant-Unionist side of the divide, the clubs in the Catholic Irish-Scots community are held ‘responsible’ for introducing ‘ethnicity, politics and religion’ into Scottish football.Footnote44 As a result, Murray pointed the blame at Edinburgh’s Hibernian and Celtic for introducing ‘sectarianism’ into Scottish football.Footnote45 In relation to Glasgow, he argued that Celtic’s rampant success, mixed with its strong Irish-Catholic worldview, led to Protestant fans, implied by Murray to be the ‘mainstream’, as if this were a normative category in itself, leaving their ‘wee’ clubs and unifying their forces under the overtly Protestant-Unionist banner of Rangers. Finn argued that Murray depended upon the common Scottish myth of ‘minority responsibility’ or ‘culpability’.Footnote46 When the concept is applied to football, the logic says that there was ‘no problem here’ in Scottish football until it was initiated by the minority Irish-Scots community.Footnote47 Racism took on its more ‘contemporary form’ when fans and media mocked a proposed Indian-Scot takeover of Glasgow’s third club, Partick Thistle FC, in the mid-1990s.Footnote48

The Palestine issue and the Palestine connection

Ilan Pappé points out the present-day contradiction in relation to Palestine, which seems to block even the prospect of forward movement on the issue.Footnote49 There has been a major change in global opinion in favour of the Palestinians in the context where political and economic elites in the West continue to support the Jewish state.Footnote50 The elephant in the room is always the history of the Israeli state seen as a direct response to the Holocaust. Israel’s policies are permitted to be criticized, but not the regime or its ideology. As such, Muslims globally feel powerless and frustrated. They are looking for someone to identify with them as well as, of course hoping for a change in the situation on the ground.

A 1984 article by Edward Said, entitled ‘Permission to Narrate’, called for an alternative narrative on the Palestine/Israel issue, from the perspective of the Palestinians, which challenged hegemonic terms and discourses.Footnote51 Controversially, he claimed that even other Arabs do not want to acknowledge a narrative of the Palestinian people living in other Arab countries: Palestine is fine for them, not the Palestinians.Footnote52 Israel too claims that Palestinians are not a real people group with an identifiable history or land.Footnote53 New narrative terms could include ‘decolonization’, ‘regime change’, and even ‘one-state solution’ (a secular, multicultural state such as Indonesia, Turkey or Singapore).Footnote54 The two-state solution, seen almost as a religious tenet by the Peace Orthodoxy, should also be challenged because it will end up as inequality heaped up upon inequality. Seemingly harmless, taken-for-granted expressions such as ‘a land for two people’, ‘the peace process’, ‘violence on both sides’, ‘negotiations’, and ‘two-state solution’ must be subjected to critical heat and light. The racist nature of the Israeli state and the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine are two historical issues now overdetermined by ideological forces and intransigent attitudes, which work to reproduce the status quo.Footnote55

Whilst many would see it as utopian socialist and unrealistic, Pappé never gives up in arguing for a one-state solution.Footnote56 This may well represent critical thought in sections of the academy, but it is unlikely to receive much traction amongst the US-Israeli establishments or even on the ground amongst (especially) the Israelis. It seems to be a bridge too far. It could happen in South Africa because, as Noam Chomsky claims, the white authorities knew that they were dependent on a black working-class to keep the economy functioning.Footnote57

Some Palestine/Israel history, again according to Pappé, is presented next.Footnote58 First, he presents three myths and three truths. The myths are as follows: the conflict is one ‘fought between two national movements’; the conflict only began in 1967 after the annexation by Israel of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip; and the West Bank and Gaza Strip, by nature and history, are more intrinsically ‘Palestinian’ than the rest of Palestine.Footnote59 The three truths are as follows: the conflict is a struggle between a settler-colonialist movement and a native indigenous population that has its beginnings in the late nineteenth century; from the settler-colonialist perspective, the conflict involves a relentless drive to take as much land as possible and leave in it as few Palestinians as possible; and the aim of the Zionist campaign is to create ‘a European kind of democracy’ but it has to be a ‘Jewish democracy’.Footnote60 The ‘inevitable result’ of these ideologies and tendencies was a ‘vast ethnic cleansing operation’ that commenced before the British vacated the country in February 1948 and ended only in early 1949.Footnote61 This was a consequence of acting out the Zionist ideology, and by the serious problem for the Zionists that Jewish settlers were only one-third of the population in 1948. In 1948–49, Palestinians were forcibly exiled from their land, except for the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. According to Pappé, the West Bank became the ‘biggest ever human mega-prison witnessed in modern times’.Footnote62 It was an outdoor prison. Israel made three key decisions, around June 1967, writes Pappé: not to ethnically cleanse the population as the army might not have the will or mentality to achieve this; exclude the West Bank and the Gaza Strip from any future peace talk deals; and to not grant full citizenship to the occupied population. As Pappé concludes: ‘There can be no benign or enlightened version for a policy meant to keep people in citizenless status for a long period of time’.Footnote63 Two versions of the mega-prison were given: the open-air one, and, if that was not accepted, a maximum security one. There is no ‘other Zionism’ or ‘other Israel’ than a ‘colonialist movement’ and ‘apartheid racist state’.Footnote64 By contrast, Chomsky sees similarities with apartheid South Africa, but also important differences – the Israelis perceive that they do not need the Palestinians even as a labour-force.

Open discrimination, based on ethnicity and religion, even inside the Green Line, where 20.7% of the population is Palestinian,Footnote65 leads to disenchantment and alienation amongst Glasgow’s Muslim youth who identify with the sufferings of Muslims worldwide. Celtic fans’ gestures of support for PalestineFootnote66 take on major significance, and some see parallels with the Irish-Catholic people’s historic struggles for reunification in Ireland and equality in Scotland.Footnote67 The Roman Catholic dimension adds an extra touch of relevance and potency to these comparisons as religious discrimination features in both contexts. By contrast, Rangers are already behind the eight-ball since their support for the British state and military would be seen as unattractive components of their values from a Pakistani/Muslim standpoint.

Tariq Ramadan provided his assessment of the Palestine/Israel situation as at the turn of the millennium.Footnote68 The world witnessed the putting back up against the wall of Yasser Arafat, Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), by the West, his new powerlessness, his new remoteness from his people and the cause, and his use by the Western powers as a puppet figure who would accede to the peace process because he had sided with the wrong ally. The ‘consolidation’ of the ‘peace process’ discouraged Muslims globally because they could see at the same time the situation on the ground deteriorating rapidly. The Zionists controlled the discourse, and the very choice and meaning of words. In its very support for the British State and the British Army, Rangers had lost the war for the hearts and minds of Glasgow’s Muslims. Celtic’s Green Brigade ultras then saw an opportunity.

A few words are in order about the rising popularity of Hamas, the governing Palestinian organization in the Gaza Strip since 2007.Footnote69 The success is due to the propagation of Islamic values and practices, built upon a grassroots approach focused on individual piety and charity. It was able to grow support because the more secular organizations such as the PLO faction Fatah were seen as more corrupt, and the secular ideologies were seen as failing to produce effective self-governance. The Hamas leaders were seen as being in tune with the Islamic core values existing in the region. Hamas had the view that, in turning the population from sin, moral character could develop on an individual level, and resistance to outward aggression would be strengthened by having a stronger moral core. The discourse moved away from secular human rights notions towards the Islamic character of the community (and this may have distressed Edward Said had he lived to see Hamas win an election). Since Fatah was governing authority in the West Bank, post-the Oslo Accords, and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, the performances and characters of both governing authorities can be compared. The new-found energy and religious convictions of Hamas supporters has empowered Muslims globally to find solutions to the Palestine Question, and not to accept questionable solutions brokered from the outside which fail to fully take into account Muslim identities and values. According to Turner, the peace process of 1993–2000 ‘only delivered peace to one side’.Footnote70

Materials and method

Survey/questionnaire and interviews

Our survey had fifteen (15) questions; and the Qualtrics link was distributed to the respondents through social media in the hope of snowball sampling (as defined below). The survey included a few open-ended questions, which were written in order to obtain detailed answers from the respondents. Dillman claims that three types of data variables can be gathered by questionnaires: opinion, behaviour, and attributes.Footnote71

We used the convenience method of sampling for the survey. Convenience sampling involves ‘selecting haphazardly those cases that are easiest to obtain for your sample’.Footnote72 According to Saunders et al., bias can influence features in a convenience sample due to the ease of bringing together the chosen participants. Most of our sample members were university students, which created a tendency towards homogeneity of views and interests. However, as our institution has many older students, there was a reasonably diverse set of ages; and the sample had a near equal number of men and women.

We used snowball sampling only for the survey (in conjunction with convenience sampling). The researchers knew all five interviewees personally. Snowball sampling is generally used when it is difficult to find members of the chosen population.Footnote73 A good example would be individuals who claim unemployment benefits but are actually employed. With this technique: (1) contact has to be made with one or two cases in the population; (2) ask these cases to find more cases; (3) ask these new cases to find more new cases (and so on); and (4) stop if no new cases are put forward or if the sample is large, yet manageable. With snowball samling, the issue of bias is significant as respondents are likely to find other possible respondents who are like themselves, leading to a relatively homogeneous sample.Footnote74 However, for a population that is difficult to find, snowball sampling may be the only practical alternative.Footnote75

We used semi-structured interviews for the gathering of the interview data. All five interviews were conducted by the first-author, face-to-face. They lasted from ten to fifteen minutes. For Kahn and Connell, ‘[a]n interview is a purposeful discussion between two or more people.’Footnote76 Interviews allow the researcher to collect additional data, both reasonable and reliable, which will aid in answering the researcher’s research questions. This is supported by Kvale who claims that ‘an interview is literally an inter view, an interchange of views between two or more people [conversing] on a topic of mutual interest’.Footnote77

The interview answers were recorded in a notebook, in shorthand form, by the researcher. These were reviewed in the evening immediately following each interview so that uncertainties and omissions could be followed up on and major themes identified. Tape-recording was not used because all five interviewees stated that they did not agree to be tape-recorded.

Ethical considerations

Our University Ethics Committee granted approval for both the survey and the interviews. We gave an information sheet to the participants of both the interviews and the surveys, which stated the reasons for the research as well as the aim of the researchers. In addition, we informed each participant about the confidentiality of the interviews and surveys; and advised them that they were free to exit the research process at any time. We use participant numbers, rather than real names, throughout this article to ensure anonymity.

Results

Survey and interview demographics

In this section, we present the results from the survey and semi-structured interviews. Every one of our 51 survey respondents self-identified as Muslim (see ). The majority of respondents (37 people or 73%) were in the 18–25-year-old age bracket. Every respondent lived, at least during the current semester, in the Greater Glasgow area, which includes the localities of Airdrie, Barrhead, Clydebank, Coatbridge, Johnstone, Milngavie, Motherwell, Paisley, and Renfrew. There was a little confusion here as one respondent put ‘Lanarkshire’ while another put ‘Hamilton’. In fact, Hamilton is a town within the local council area of South Lanarkshire. (A council area called Lanarkshire does not exist.) East Renfrewshire, nominated by 4 respondents, is also a council area and not a locality. However, the vast majority of respondents identified a Greater Glasgow locality. Most popular by far were three neighbouring localities on Glasgow’s Southside, not far from the city-centre: Pollokshields (20 people, 39%), Govanhill (5 people or 10%), and Shawlands (4 people or 8%). These three localities, located in a small region just south of the River Clyde and the M8/M74 Motorway, are generally regarded, taken together, as the cultural heartland of Glasgow’s Pakistani community. Govanhill is more ethnically-mixed than Pollokshields with a major Eastern European presence existing alongside the Pakistani presence. Battlefield, Dumbreck, Rutherglen, Toryglen, and possibly Burnside, are also identifiably Southside localities.

Table 1. Survey demographics.

provides demographic information for our five interviewees.

Table 2. Interviewee demographics.

Table 3. Support for either Rangers or Celtic.

Analysis of results

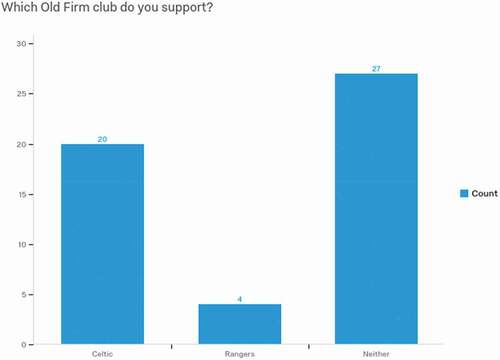

shows that 20 (39%) of the respondents supported Celtic and only 4 (8%) supported Rangers. In addition, 27 people (53%) supported neither club. Some respondents provided a reason as to why they supported Celtic or Rangers. These reasons are outlined in .

Table 4. Reasons for supporting celtic or rangers.

If we look at the Chi-squared test, we see that the differences in responses are statistically significant at the 1% level (chi-square = 16.353, sig. = 0.000) (). We can reasonably reject any concern that the result we report here is purely a chance outcome.

As suggests, Celtic was the most popular choice as it was selected by 20 respondents. This is no surprise considering the support that it showed for Palestine and the donations that the club’s fans made to nominated Palestinian charities. However, 6 of the respondents did not provide a reason as to why they supported either Celtic or Rangers.

Celtic and Rangers should also identify the fans as customers in order to attract more fans to the Scottish Premiership. As with the perennial dilemma faced by Australian soccer,Footnote78 both the Old Firm clubs should expand their consumer-market by bringing in football fans from all cultural backgrounds.

The on-field success of Celtic may also be a factor behind Pakistanis supporting the club, even if people are only subconsciously aware that this is why they are attracted to the club. Some respondents chose Celtic as other people followed them as well. This suggests that these respondents are not specifically aware of the club’s success influencing them. Everyone loves to support a winning team and they want to be happy most nights after games rather than depressed. The data was collected in January 2019 before Rangers’ massive improvement in the 2020/21 season when they won the title with a number of games to spare.

The respondents who supported Celtic since childhood, as well as those who labelled the club as the best team in Scotland, may follow the club regularly. Based on the model of Hunt et al.,Footnote79 these fans can be categorized as local or devoted fans while the fans that followed other people in choosing Celtic may be termed temporary fans.Footnote80 One respondent supported Rangers as the club was associated with Sir Alex Ferguson in the past. This type of fan is also a local or devoted fan. No respondent to the survey appeared to obviously belong to either the fanatical or dysfunctional category of fans.

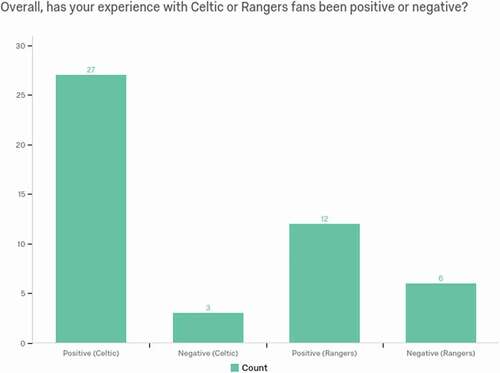

This chart illustrates that 27 (53%) and 12 (24%) of the respondents in the survey have had a positive experience with Celtic and Rangers’ fans respectively. On the other hand, 3 (6%) of the respondents have had a negative experience with Celtic fans and 6 (12%) have had a negative experience with Rangers’ fans. (Only one option could be selected.)

shows that the differences in responses here are statistically significant at better than the 1% level (chi-square = 28.500, sig. = 0000). We coded the responses as: positive-Rangers = 0, negative-Celtic = 1, negative-Rangers – 2 and positive-Celtic = 3. We labelled the responses this way based on the argument that a negative experience of a team’s fans is less likely to lead to supporting a (i.e. any) team than a positive experience. Many of the respondents supported neither team and these people were more likely to have had negative experiences overall (because favourable experiences usually occur within the confines of the stadium).

I am a Celtic fan who stays close to the Rangers’ stadium but that hasn’t been an issue for me as I don’t go around shouting ‘I am a Celtic fan’ as I know there would be some fans who would be quite aggressive. I think Rangers’ fans are more aggressive than Celtic fans (Participant 1).

I have always been a Celtic fan as I grew up in a family that has been supporting Celtic since day one. Most of my friends I grew up with supported Celtic so I followed suit and pledged my support too. After some Celtic games, the Rangers’ fans would express their loss in a bad way and I would get into fights with them (Participant 2).

Table 5. Experiences with Celtic and Rangers fans.

In addition, two survey respondents stated their opinion about Celtic fans:

Celtic showed support for Palestine which indicates that the fans have high moral and ethical standards (Participant 59, male, 18-25).

The Celtic fans are more hospitable and their views are purposeful towards the Muslim community (Participant 55, male, 18-25).

The support that was shown for Palestine in 2016 and 2021 are examples of how ‘hospitable’ the Celtic fans are towards Muslims. McKenna reported in August 2016 about the waving of Palestine flags by 100 Celtic fans at the team’s Champions League game against Israel’s Hapoel Be’er Sheva.Footnote81 To cite McKenna:

So around 100 Celtic fans in a crowd of 60,000 waved Palestinian flags at the game in a show of solidarity with the Palestinians. They knew the game would be beamed live around the world and they simply wanted to communicate to an oppressed people that, in a small corner of Glasgow, they were not forgotten. The Israeli players were treated respectfully throughout, as was Celtic’s midfielder and Israeli international player Nir Bitton, who was given a standing ovation when he left the field.

The Celtic fans raised money for two relief charities operating in the West Bank. The aim was to raise £75,000, which would allow any fine for political protests to be paid, as well as give an amount to the two charities. As at 28 August 2016, the donation tally had exceeded everyone’s expectations and was above £200,000. The suffering of the Palestinian people was similar to the treatment the poor Irish immigrants received when they first arrived in the East End of Glasgow. This support by Celtic fans demonstrated that Palestine was not alone. In May 2021, Celtic FC gave fans access to the stadium, amidst the Covid-19 lockdown, to express support for departing captain Scott Brown. Instead, some fans used it to display Palestinian flags due to increased tensions in Israel-Palestine.Footnote82 The club condemned the move.

Based on the interview data and survey responses, it appears likely that Rangers’ fans are not as accepting of Pakistanis as compared to Celtic fans. One survey respondent stated:

Lot of racism attached to Rangers. Game wise also [this probably refers to racism occurring on match days] (Participant 34, female, 18-25).

This statement is consistent with the racist abuse Mark Walters received not just from opposition fans but from his own supporters. Walters was subjected to a barrage of racist abuse during his time in Scotland but the incident at Hearts is probably the worst case of racism to have taken place in Scottish football and British sports overall.

According to one interviewee, racism still exists among Rangers’ supporters.

I am a Celtic fan. I have not had any positive or negative experiences with either Celtic or Rangers. However, I am aware of the treatment which Muslim/British-Pakistanis have received, as a result of being a Rangers supporter and being an Asian person. My friends, who are also Asian, have received racial abuse from Rangers fans, while attending a Rangers game, as a Rangers fan /supporter.

Alleged acts of racism from players, coaches, and fans has been one key factor that has halted the progression of Asians into British professional leagues.Footnote83

To promote development of Asian players in Scottish football, Celtic and Rangers should reach out to the Asian community:

Researcher: How should Celtic and Rangers reach out to the Asian community?

Participant 1: I think they should start having tournaments for younger children between the ages of 5-15. This would only be for Asian people. Then, onwards, they can get scouted from respective clubs and have trials and gain progression to the first team.

Researcher: How should Celtic and Rangers reach out to the Asian community?

Participant 3: Celtic and Rangers should aim to scout more Asian talent within Scotland. This can be done by scouting young Asian footballers who play for their local football team, e.g. an Asian playing for Under-15’s team for St. Mirren. After scouting, players can then be invited for a trial at either Celtic/ Rangers.

Additionally, Celtic and Rangers should market to the Asians more as they rarely get marketed to specifically. There is an assumption that more Asians in the teams would attract more Asian fans. However, despite the East End of London having a sizable Asian population, few Asians go along on match days to support the local team West Ham United.Footnote84

Few respondents in our sample attended Scottish Premiership games regularly (see ) – some attended more than others, but most did not attend.

Table 6. Number of Scottish Premiership games per year.

Based on ethnography research, with Hibernian fans, Fillis and MackayFootnote85 put forward a matrix of supporter behaviour as follows, drawing in part upon Giulianotti’s earlier schemaFootnote86: (1) committed supporters – who invest time and money into active and passionate support, and are seen as leaders among the supporters; (2) social devotees – who enjoy the social atmosphere of the match-day experience and may drop away if friends depart the scene; (3) fans – who follow the team but with less intensity than the committed supporters; and (4) casual followers – who maintain some interest in the team, and attend sometimes but more frequently keep up with scores online. Our respondents appear to be spread across the four caregories, with the non-regular-attendees being either fans or casual followers. Those who don’t support Celtic or Rangers may be fans or casual followers of English clubs.

It might be asked how fans who do not attend games (or attend only rarely) could have had positive or negative experiences with other fans. The reason would be that, because these clubs are so important to Glasgow everyday life and society, fans experienced ridicule or even racism from other fans at schools, in shops or restaurants, or even on the street. It would be wrong to label non-attendees as non-football fans as there are a variety of reasons behind non-attendance including work, study, and family commitments and the cost of season tickets. The Pakistani community in Glasgow is heavily engaged in the small-business sector, with people often working long hours in shops, cafes, and restaurants. Hence their ability to attend games may be limited, as would travel to away matches.

The creation of an Asian/Muslim club

Results reveal that 44 respondents out of 51 (86%) supported the ‘creation of an Asian/Muslim club in the Scottish Premiership’ (our wording) while only 6 (12%) disagreed.

reveals that the difference between Yes and No responses is statistically significant at better than the 1% level, suggesting very strongly that these results are not due to chance (chi-square = 28.880, sig. = 0.000).

Table 7. Support for the creation of an Asian/Muslim club.

Why did we put the question in this way when a new club going straight into the Premiership would be an extremely unlikely event and could only happen after a vote of all of Scotland’s 42 league clubs, as happened when clubs voted to relegate Hearts, Partick Thistle, and Stranraer after the lockdown-curtailed 2019/20 season?Footnote87 We formatted the question this way so as to avoid a situation where respondents expressed disinterest in a new club because the new club was in the lower leagues of the pyramid. We were asking a hypothetical in other words. We wanted to know whether the respondents would support an Asian/Muslim club if it was playing in the Premiership. In hindsight, we should have worded the question in this way rather in the way stated above. But the result probably would have been the same.

Each participant in the interview also supported the creation of an Asian/Muslim club but some admitted that the existence of such a club would be unlikely:

Researcher: Would you support the creation of an Asian/Muslim club in the SPL?

Participant 1: Yes, definitely but I do not think this would happen under SPFL regulations. They would say this team is only going to be looking for South Asian players and [thus] is not ethnically diverse.

Participant 3 Yes, this would be great for the Asian community as it allows for Muslim/Asian talent to be displayed, as there are currently no British-born Asian players in the first team for Scotland, and for Scottish teams (SPL).

Participant 5: Yes I would – I feel this is a good idea to engage the Asian community and encourage their participation. However, I feel this is a big change to implement and will not come around easily.

Participant 4: Yes, but alongside Asian players, there should be non-Asian as well - maybe an equal ratio of Asian and non-Asian players.

Having Asian and non-Asian players at an ‘Asian club’ would increase inclusivity and maybe improve the team on-the-field. Starting a new club would pose enormous challenges as the new club would need to work its way up through the extant pyramid structure, through successive promotions, and this is not an easy thing to achieve. (Although the achievements of Cove Rangers and Ross County in this regard should be noted, it did take Ross County 18 years to move from the Highland League to the Premiership. By contrast, Cove gained back-to-back promotions from the Highland League to League One in 2018–20.) Another option is to buy-out and relocate a League One, League Two or Lowland League club, with the governing body’s permission, as happened when Airdrieonians was liquidated in 2002 and bought over Clydebank, relocating it to Airdrie and changing its name and colours.

Summary of results

Do Glasgow Pakistanis support Celtic or Rangers and why?

The opinions of the survey participants regarding the two ‘Old Firm’ clubs were mixed. 20 (39%) of the respondents supported Celtic and only 4 (8%) supported Rangers (out of 51). Some respondents gave a reason as to why they chose to support either club. One Rangers supporter stated the club’s ties with Sir Alex Ferguson as the reason for supporting the club. On the other hand, the respondents who chose Celtic provided similar reasons. Four respondents stated that the solidarity with Palestine among Celtic fans was the reason they supported Celtic. Four other respondents claimed that they have been following the club since childhood and an additional four chose to follow Celtic as the people around them follow the club. Racism experienced at Rangers was another reason proffered by respondents.

What are the experiences of Pakistanis with Celtic and Rangers fans?

Most of the survey and interview participants had a positive experience with Celtic fans and only a few had a negative experience. Although there were also more positive than negative experiences with Rangers’ fans, the ratio of positive-to-negative was much lower than for Celtic fans (see ). Rangers have been associated with racism in the past as revealed in the treatment of Mark Walters and the sectarian abuse of Kilmarnock manager Steve Clarke.

Would the Pakistani community in Glasgow support the creation of an Asian/Muslim club?

Although 86% of study participants supported the creation of an Asian/Muslim club, the process of making such a transition will be difficult and unlikely due to the expenses involved and the potential disputes that may arise with local residents. Likewise, taking over a lower-league club might provoke some backlash from the existing fan-base (although the Airdrieonians’ takeover of Clydebank does offer some sort of precedent).

Limitations

A review of the research process reveals certain limitations. For example, ‘Scottish’ identity should have been given as an option, in both hybridized (i.e. ‘Pakistani-Scot’) and unadorned forms, in the survey. A question about the type of school the Pakistani-origin person in Glasgow went to, or goes to, should also have been included in the survey as anecdotal evidence suggests that Pakistani-Scots are more likely to support Rangers if they go to a state-school (i.e. non-Catholic school). Furthermore, the respondents should have been given the option to choose two or more options, instead of one, for the question about the positive and negative experiences with Celtic and Rangers fans.

Future research

Because of the small sample-size, this is only a pilot-study, but it does suggest future research possibilities. Firstly, the study should be reproduced with a larger sample. And, since most of our respondents support English Premier League clubs, further research should be done on whether Asians in England support their local team or a different team. For example, do Birmingham Asians support Aston Villa, Birmingham City or a faraway club like Manchester United? It would also be interesting to follow up someone’s suggestion that Glasgow’s Sikhs mostly support Rangers. Lastly, the study could be replicated in relation to support for the two Edinburgh clubs and the two Dundee clubs, although obtaining reasonable sample-sizes might be difficult. Heather Andrews has done some interesting preliminary work about why fans support Dundee United, but ethnicity does not feature in her research project.Footnote88

Recommendations

The conundrum is how to get Glaswegians of Pakistani descent that are football fans to attend more Scottish games. As Celtic was supported by 39% of survey participants, the club should make an attempt to promote itself in Asian countries where football’s popularity is increasing. It should also to work sign more Asian players, as should Rangers. At one time, Motherwell tried to sign a star young goalkeeper from India, Dheeraj Singh, but visa complications saw the deal break down. Having more Asian players playing for Scottish Premiership clubs may encourage both more local Asian support and more support from the subcontinent.

Disclosure statement

We declare that we have no relevant conflict of interests, financial or otherwise.

Notes

1. May, ‘The Relationship between Football and Literature’; Murray, The Old Firm in the New Age, 167–89; Watson, ‘Criminalizing Songs and Symbols in Scottish Football’.

2. Giulianotti and Gerrard, ‘Cruel Britannia?’ 28.

3. Anthony May studies the ethnic and national identities of the characters in Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting, most of whom are Hibernian fans. He finds that most adopt a Scottish nationalism, which notes its own Irish roots but moves beyond them as reflecting the willed and actual integration of much of the Edinburgh-born population. By contrast, Celtic fans from Glasgow are perceived to be ‘plastic Paddies’ who view everything in terms of ‘sectarianism’ (see our later discussion in the main text on this topic). Antipathy towards the Union and Unionist-Loyalists is a common feature of these Hibs fans and those earlier generations of Irish-Scots who saw themselves as predominantly Irish. Therefore, they can both be treated as part of the same social force or demographic, which is opposed to Unionism and the British State. May, ‘The Relationship between Football and Literature’.

4. Fillis and Mackay, ‘Moving Beyond Fan Typologies’, 351.

5. G. Richardson, ‘Behind the Convenient Myth of Sporting Integrity’, 135.

6. Kowalski, ‘Cry for us, Argentina’, 74–5.

7. McLeish, ‘HMRC Miss the Target’, 127–8; G. Richardson, ‘Behind the Convenient Myth of Sporting Integrity’, 138.

8. Graham, ‘Taking on the Establishment, 85-6.

9. Ibid, 87.

10. A. Richardson, ‘Rangers Promoted’.

11. Giulianotti and Gerrard, ‘Cruel Britannia?’ 24.

12. Donnelly et al., ‘Take-over and Turnaround at Celtic’.

13. Kowalski, ‘Cry for us, Argentina’, 74.

14. Wardak, Social Control and Deviance.

15. Maan, The New Scots, 168.

16. Wardak, Social Control and Deviance.

17. Berry, ‘Immigration, Acculturation and Adaptation’.

18. Saroglou and Mathijsen, ‘Religion, Multiple Identities and Acculturation’.

19. Nagel and Staeheli, ‘Integration’.

20. Maxwell, ‘Muslims, South Asians and the British Mainstream’.

21. Bisin et al., ‘The Specific Patterns’.

22. Joppke, ‘Limits of Integration Policy’.

23. Vedder et al., ‘The Acculturation’.

24. James and Walsh, ‘The Expropriation’.

25. Chaudhury and Miller, ‘Religious Identity Formation’.

26. Peek, ‘Becoming Muslim’.

27. Wardak, ‘The Mosque and Social Control’.

28. Ostberg, ‘Norwegian-Pakistani Adolescents’.

29. Ibid.

30. Hopkins, ‘Blue Squares’.

31. Office of National Statistics, ‘Country of Birth’.

32. Din, The New British.

33. Modood, Multiculturalism.

34. Ghuman, Asian Adolescents; Kabir, Young British Muslims; Mir, ‘The “Other” within the “Same”’; Modood, Multiculturalism.

35. Ansari, Muslims in Britain, 197.

36. Jacobson, ‘Religion and Ethnicity’.

37. Saeed et al., ‘New Ethnic and National Questions’.

38. Murray, The Old Firm (first edition), The Old Firm (revised edition).

39. The first (1984) edition of Murray’s book says that Hibernian FC (based in Leith in Edinburgh) was the first ‘sectarian’ team in Scotland. Murray, The Old Firm (first edition), 19. By contrast, the revised edition of 2000 says that Hibernian was the first ‘prominent all-Catholic’ team. Murray, The Old Firm (revised edition), 12.

40. Murray, Bhoys, Bears and Bigotry, 184.

41. Finn, ‘Racism I’, ‘Racism II’, ‘Sporting Symbols’, ‘Faith, Hope and Bigotry’, ‘Scottish Myopia’.

42. Devine (ed.), Scotland’s Shame?

43. Dimeo and Finn, ‘Racism, National Identity and Scottish Football’, 34.

44. Ibid, 33, 34.

45. Ibid, 34; Finn, ‘Racism I’, 79–80, 82; Murray, The Old Firm (first edition), 19.

46. Finn, ‘Racism I’, 92, ‘Racism II’, 372; Dimeo and Finn, ‘Racism, National Identity and Scottish Football’, 34.

47. Dimeo and Finn, ‘Racism, National Identity and Scottish Football’; 35, cited in Kelly, ‘“Sectarianism” and Scottish football’, 430–1.

48. Dimeo and Finn, ‘Racism, National Identity and Scottish Football’, 35.

49. Pappé, ‘The Old and New Conversations’, 11.

50. Pappé, ‘A Brief History of Israel’s Incremental Genocide’, 152–3.

51. Said, ‘Permission to Narrate’.

52. Ibid, 32–3.

53. Ibid, 31.

54. Pappé, ‘The Old and New Conversations’, 15.

55. Ibid, 20.

56. Chomsky and Pappé, ‘The Future’, 108–14.

57. Chomsky and Pappé, ‘The Past’, 76.

58. Pappé, ‘The Futility and Immorality of Partition in Palestine’.

59. Ibid, 167.

60. Ibid, 168.

61. Ibid, 169.

62. Ibid, 171.

63. Ibid, 174.

64. Ibid, 178.

65. Pappé, ‘The Old and New Conversations’, 24. Regarding the 20.7% figure, Mustafa and Agbaria, ‘Islamic Jurisprudence of Minorities’, 191.

66. AFP, ‘Scotland’s Celtic Soccer Team’; McKenna, ‘Why Celtic Fans Flew the Flag’.

67. Farrell and James. ‘Does Identity and Integration?’.

68. Ramadan, Islam, the West and the Challenges of Modernity, 282–6.

69. Dunning, ‘Islam and Resistance’.

70. Turner, ‘Fanning the Flames’, 507.

71. Dillman, Mail and Internet Surveys.

72. Saunders et al., Research Methods.

73. Ibid.

74. Lee, Doing Research.

75. Saunders et al., Research Methods.

76. Kahn and Connell, The Dynamics of Interviewing.

77. Kvale, InterViews, 14.

78. Gorman, The Death & Life; James and Walsh, ‘The Expropriation’.

79. Hunt et al., ‘A Conceptual Approach’.

80. Beech and Chadwick, The Business of Sports Management.

81. McKenna, ‘Why Celtic Fans Flew the Flag’.

82. AFP, ‘Scotland’s Celtic Soccer Team’.

83. Bains and Patel, Asians Can’t Play Football.

84. Fawbert, ‘Wot, no Asians?’.

85. Fillis and Mackay, ‘Moving Beyond Fan Typologies’.

86. Giulianotti; Football; Walsh and Giulianotti, ‘This Sporting Mammon’.

87. As McLeod and his co-authors explain, ‘Professional football in Scotland is administered by the Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL). The SPFL is a membership association consisting of 42 clubs competing across four leagues’. McLeod et al., ‘Board Roles in Scottish Football’, 42.

88. Andrews, ‘Football and Family’.

Bibliography

- AFP. ‘Scotland’s Celtic Soccer Team Removes Palestinian Flags Displayed by Fans’. The Times of Israel, May 12 2021. https://www.timesofisrael.com/scotlands-celtic-soccer-team-removes-palestinian-flags-displayed-by-fans/ (accessed May 14, 2021).

- Andrews, H. ‘Football and Family: The Influence of Family on Team Support among Dundee United Fans’. Ethnographic Encounters 4, no. 1 (2013): 4–12.

- Ansari, H. Muslims in Britain. London: Minority Rights Group International, 2002.

- Bains, J., and R. Patel. Asians Can’t Play Football. Solihull: ASDAL, 1996.

- Beech, J., and S. Chadwick. The Business of Sports Management. Edinburgh: Pearson, 2004.

- Berry, J.W. ‘Immigration, Acculturation and Adaptation’. Applied Psychology 46, no. 1 (1997): 5–34.

- Bisin, A., E. Patacchini, T. Verdier, and Y. Zenou. ‘The Specific Patterns of Muslim Immigrants’ Integration in the UK’. Vox-EU, September 9 (2007). http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/556 (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Chaudhury, S.R., and L. Miller. ‘Religious Identity Formation among Bangladeshi American Muslim Adolescents’. Journal of Adolescent Research 23, no. 4 (2008): 383–410. doi:10.1177/0743558407309277.

- Chomsky, N., and I. Pappé. ‘The Future’. in On Palestine, ed. F. Barat, 99–118. London and Chicago: Penguin/Haymarket, 2015a.

- Chomsky, N., and I. Pappé. ‘The Past’. in On Palestine, ed. F. Barat, 49–76. London and Chicago: Penguin/Haymarket, 2015b.

- Devine, T.M., ed. Scotland’s Shame? Bigotry and Sectarianism in Modern Scotland. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2000.

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2007.

- Dimeo, P., and G.P.T. Finn. ‘Racism, National Identity and Scottish Football’. in ‘Race’, Sport and British Society, ed. B. Carrington and I. McDonald, 29–48. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Din, I. The New British: The Impact of Culture and Community on Young Pakistanis. Hampshire: Ashgate, 2006.

- Donnelly, T., M. Donnelly, and T. Donnelly. ‘Take-over and Turnaround at Celtic: The McCann Years 1994-1999’. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 4, no. 1 (2008): 49–61. doi:10.1504/IJSMM.2008.017658.

- Dunning, T. ‘Islam and Resistance: Hamas, Ideology and Islamic Values in Palestine’. Critical Studies on Terrorism 8, no. 2 (2015): 284–305. doi:10.1080/17539153.2015.1042304.

- Farrell, C., and K. James. ‘Does Identity and Integration Cause Muslims to Choose to Support Celtic Football Club?’. Journal of Physical Fitness, Medicine & Treatment in Sports 6, no. 5 (2020): 1–6.

- Fawbert, J. ‘‘“wot, No Asians?”: West Ham United Fandom, the Cockney Diaspora and the “New” East Enders’. in Race, Ethnicity and Football: Persisting Debates and Emergent Issues, ed. D. Burdsey, 175–190. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Fillis, I., and C. Mackay. ‘Moving beyond Fan Typologies: The Impact of Social Integration on Team Loyalty in Football’. Journal of Marketing Management 30, no. 3–4 (2014): 334–363. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.813575.

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Racism, Religion and Social Prejudice: Irish Catholic Clubs, Soccer and Scottish Society - I the Historical Roots of Prejudice’. The International Journal of the History of Sport 8, no. 1 (1991a): 72–95. doi:10.1080/09523369108713746.

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Racism, Religion and Social Prejudice: Irish Catholic Clubs, Soccer and Scottish Society - II Social Identities and Conspiracy Theories’. The International Journal of the History of Sport 8, no. 3 (1991b): 370–397. doi:10.1080/09523369108713768.

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Sporting Symbols, Sporting Identities: Soccer & Inter-Group Conflict in Scotland and Northern Ireland’. In Scotland and Ulster, ed. I.S. Wood, 33-55. Edinburgh: Mercat, 1994a.

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Faith, Hope and Bigotry: Case-Studies in Anti-Catholic Prejudice in Scottish Soccer and Society’. In Scottish Sport in the Making of the Nation: Ninety Minute Patriots? ed. G. Jarvie and G. Walker, Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1994b.

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Scotland, Soccer, Society: Global Perspectives, Parochial Myopia’ (Paper presented to the ‘Crossing Boundaries’ North American Society for Sports Sociology Annual Conference, Toronto, Canada, 1997).

- Finn, G.P.T. ‘Scottish Myopia and Global Prejudices’. Culture, Sport, Society 2 2 (1999): 54–99. doi:10.1080/14610989908721847.

- Ghuman, S. Asian Adolescents in the West. Leicester: British Psychological Society, 1999.

- Giulianotti, R. Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999.

- Giulianotti, R., and M. Gerrard. ‘Cruel Britannia? Glasgow Rangers, Scotland and “Hot” Football Rivalries’. in Fear and Loathing in World Football, ed. G. Armstrong and R. Giulianotti, 23–33. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

- Gorman, J. The Death & Life of Australian Soccer. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2017.

- Graham, C. (2013). Taking on the establishment: Rangers and the Scottish football authorities. In W.S. Franklin, J. D. C. Gow, C. Graham, & A. McKillop (Eds.), Follow we will: The fall and rise of Rangers (pp. 80-93). Edinburgh: Luath Press.

- Hopkins, P. ‘Blue Squares, Proper Muslims and Transnational Networks: Narratives of National and Religious Identities Amongst Young Muslim Men Living in Scotland’. Ethnicities 7, no. 1 (2007): 61–81. doi:10.1177/1468796807073917.

- Hunt, K.D., T. Bristol, and R.E. Bashaw. ‘A Conceptual Approach to Classifying Sports Fans’. Journal of Services Marketing 13, no. 6 (1999): 439–452. doi:10.1108/08876049910298720.

- Jacobson, J. ‘Religion and Ethnicity: Dual and Alternative Sources of Identity among Young British Pakistanis’. Ethnic and Racial Studies 20, no. 2 (1997): 238–256. doi:10.1080/01419870.1997.9993960.

- James, K., and R. Walsh. ‘The Expropriation of Goodwill and Migrant Labour in the Transition to Australian Football’s A-League’. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 18, no. 5 (2018): 430–452. doi:10.1504/IJSMM.2018.094349.

- Joppke, C. ‘Limits of Integration Policy: Britain and Her Muslims’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35, no. 3 (2009): 453–472. doi:10.1080/13691830802704616.

- Kabir, A.N. Young British Muslims: Identity, Culture, Politics and the Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010.

- Kahn, R.L., and C.F. Connell. The Dynamics of Interviewing: Theory, Technique, and Cases. New York: Wiley, 1957.

- Kelly, J. ‘“Sectarianism” and Scottish Football: Critical Reflections on Dominant Discourse and Press Commentary’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46, no. 4 (2010): 418–435. doi:10.1177/1012690210383787.

- Kowalski, R. ‘“Cry for Us, Argentina”: Sport and National Identity in Late Twentieth-century Scotland’’. In Sport and National Identity in the Post-war World, ed. A. Smith and D. Porter, 69–87. Abingdon: Routledge, 2004.

- Kvale, S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

- Lee, R.M. Doing Research on Sensitive Topic. London: Sage, 1993.

- Maan, B. The New Scots: The Story of Asians in Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1992.

- Maxwell, R. ‘Muslims, South Asians and the British Mainstream: A National Identity Crisis’. West European Politics 29, no. 4 (2006): 736–756. doi:10.1080/01402380600842312.

- May, A. ‘The Relationship between Football and Literature in the Novels of Irvine Welsh’. Soccer & Society 19, no. 7 (2018): 924–943.

- McKenna, K. ‘Why Celtic Fans Flew the Flag for Palestine’. Guardian, August 28 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/27/why-celtic-fans-flew-flag-for-palestine (accessed February 28, 2019).

- McLeish, W. ‘HMRC Miss the Target’. in Born under a Union Flag: Rangers, Britain & Scottish Independence, ed. A. Bissett and A. McKillop, 125–136. Edinburgh: Luath, 2014.

- McLeod, J., D. Shilbury, and L. Ferkins. ‘Board Roles in Scottish Football: An Integrative Stewardship-Resource Dependency Theory’. European Sport Management Quarterly 21, no. 1 (2021): 39–57. doi:10.1080/16184742.2019.1699141.

- Mergulhao, M. ‘Motherwell Apply for Dheeraj’s Work Permit’. Times of India, May 30 2018. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/goa/motherwell-apply-for-dheerajs-work-permit/articleshow/64375569.cms (accessed May 1, 2021).

- Mir, S. ‘“The Other within the Same”: Some Aspects of Scottish-Pakistani Identity in Suburban Glasgow’’. In Geographies of Muslim Identities: Diaspora, Gender and Belonging, ed. C. Aitchinson, P. Hopkins, and M. Kwan, 57–77. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

- Modood, T. Multiculturalism: A Civic Idea. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2007.

- Murray, B. The Old Firm: Sectarianism, Sport and Society in Scotland. first. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1984.

- Murray, B. The Old Firm in the New Age: Celtic and Rangers since the Souness Revolution. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1998a.

- Murray, B. Bhoys, Bears and Bigotry: The Old Firm in the New Age. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1998b.

- Murray, B. The Old Firm: Sectarianism, Sport and Society in Scotland. revised. Edinburgh: John Donald, 2000.

- Mustafa, M., and A.K. Agbaria. ‘Islamic Jurisprudence of Minorities (Fiqh al-Aqalliyyat): The Case of the Palestinian Muslim Minority in Israel’. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 36, no. 2 (2016): 184–201. doi:10.1080/13602004.2016.1180889.

- Nagel, C.R., and L.A. Staeheli. ‘Integration and the Negotiation of “Here” and “There”: The Case of Britain Arab Activists’. Social and Cultural Geography 9, no. 4 (2008): 415–430. doi:10.1080/14649360802069019.

- Office for National Statistics. ‘Country of Birth and National Identity (Continued)’. 2001 Census: Religion in the UK, 2004 Edition - ONS, 7. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004.

- Ostberg, S. ‘Norwegian-Pakistani Adolescents: Negotiating Religion, Gender, Ethnicity and Social Boundaries’. Young 11, no. 2 (2003): 161–181. doi:10.1177/1103308803011002004.

- Pappé, I. ‘A Brief History of Israel’s Incremental Genocide’. in On Palestine, ed. F. Barat, 147–154. London and Chicago: Penguin/Haymarket, 2015a.

- Pappé, I. ‘The Old and New Conversations’. in On Palestine, ed. F. Barat, 9–46. London and Chicago: Penguin/Haymarket, 2015b.

- Pappé, I. ‘The Futility and Immorality of Partition in Palestine’. In On Palestine, ed. F. Barat, 167–179. London and Chicago: Penguin/Haymarket, 2015c.

- Peek, L. ‘Becoming Muslim: The Development of a Religious Identity’. Sociology of Religion 66, no. 3 (2005): 215–242. doi:10.2307/4153097.

- Ramadan, T. Islam, the West and the Challenges of Modernity. Leicester: The Islamic Foundation, 2001.

- Richardson, A. ‘Rangers Promoted: We Look at Their Journey Back to Premiership’. Sky Sports, April 15 2016. https://www.skysports.com/football/news/11788/10225953/we-take-a-look-at-rangers-journey-back-to-the-premiership (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Richardson, G. ‘Behind the Convenient Myth of Sporting Integrity’. in Follow We Will: The Fall and Rise of Rangers, ed. W.S. Franklin, J.D.C. Gow, C. Graham, and A. McKillop, 130–141. Edinburgh: Luath, 2013.

- Saeed, A., N. Blain, and D. Forbes. ‘New Ethnic and National Questions in Scotland: Post-British Identities among Glasgow Pakistani Teenagers’. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22, no. 5 (1999): 821–844. doi:10.1080/014198799329279.

- Said, E. ‘Permission to Narrate’. Journal of Palestine Studies 13, no. 3 (1984): 27–48. doi:10.2307/2536688.

- Saroglou, V., and F. Mathijsen. ‘Religion, Multiple Identities, and Acculturation: A Study of Muslim Immigrants in Belgium’. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 29, no. 1 (2007): 177–198. doi:10.1163/008467207X188757.

- Saunders, M., P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill. Research Methods for Business Students. 5th. Edinburgh: Pearson Education, 2009.

- Turner, M. ‘Fanning the Flames or a Troubling Truth? the Politics of Comparison in the Israel-Palestine Conflict’. Civil Wars 21, no. 4 (2019): 489–513. doi:10.1080/13698249.2019.1642612.

- Vedder, P., D.L. Sam, and K. Liebkind. ‘The Acculturation and Adaptation of Turkish Adolescents in North-Western Europe’. Applied Development Science 11, no. 3 (2007): 126–136. doi:10.1080/10888690701454617.

- Walsh, A.J., and R. Giulianotti. ‘This Sporting Mammon: A Normative Analysis of the Commodification of Sport’. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 5, no. 2–3 (2001): 39–50.

- Wardak, A. Social Control and Deviance: A South Asian Community in Scotland. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000.

- Wardak, A. ‘The Mosque and Social Control in Edinburgh’s Muslim Community’. Culture and Religion 3, no. 2 (2002): 201–219. doi:10.1080/01438300208567192.

- Watson, S. ‘Criminalizing Songs and Symbols in Scottish Football: How Anti-sectarian Legislation Has Created a New “Sectarian” Divide in Scotland’. Soccer & Society 19, no. 2 (2018): 169–184. doi:10.1080/14660970.2015.1133413.