ABSTRACT

The launch of the Premier League in 1992 represented the third great material transformation in the history of English football. The early 1990s was characterized by a national modernization programme of football stadia in Britain, which helped shape a new stadium ethos and arguably a distinctive generation of fans for elite levels of the game. This transformative moment has been widely written about by social scientists, but this paper argues that key aspects of these changes – and important continuities and residual traditional aspects of fan cultures – have been captured in the work of the photographer Stuart Roy Clarke. For more than 30 years, Clarke has photographed British football stadia, fans and service workers inside and around clubs at all levels. The paper argues that Clarke’s work evokes an immediacy, empathy and sensibility that adds to written accounts, and also exhibits ethical reflexivity typically required in academic research.

Introduction

We are rapidly closing in (in 2022) on the 30th anniversary of the founding of English football’s Premier League, ‘A Whole New Ball Game’, in the now infamous words of its original BSkyB satellite television sponsors. There is little doubt that in the past three decades this project has changed the parameters of top-level English football almost beyond recognition, and it has also impacted on the fan experience outside the elite and on football in many other parts of the world.Footnote1 Formed in 1992, the new league constituted a significant departure from established European traditions of professional sporting competition. It was the first modern sporting structure – so both its admirers and detractors claim – to have been invented by and for television. Not only did the Premier League signal the end of the historic and fraternal 92-club Football League, whose own origins lay in the formation in England of the world’s first league for football back in 1888, but it also prefaced an entirely new relationship between fans, audiences, sport and global television markets.Footnote2

Certainly, without the core financial support of ailing satellite TV companies in Europe, it seems clear that the new league would likely have lacked the necessary impetus, economic backing, and the crucial marketing traction required for a successful launch.Footnote3 Moreover, without the deal with the nascent Premier League aimed at growing its flatlining subscriptions, it is possible that satellite television itself in the early 1990s may have struggled to maintain its market position and later extend its national, and then global, impact. This initial, rather forced, reciprocity has remained at the heart of the mutual commercial success of the Premier League and satellite television companies ever since.

In this article want to try to explore the transformation of the English game wrought by this new synergy between football and global television, by examining the unique work of the photographer Stuart Roy Clarke. Clarke had already begun a personal project to record, in pictures, the diversity of British football crowds and the idiosyncratic nature of its stadia before the Hillsborough disaster occurred in 1989. But the disaster and its aftermath meant that he then took on a much more official role for the Football Trust in charting the redevelopment and modernization of British stadia. However, Clarke also maintained his focus in capturing the changing character of the British football crowd in this period of both continuity and significant social change. I contend that his work is an invaluable resource for academics seeking to understand more about what has been occurring in this respect over the past 30 years. But first I need to spend just a little time offering some wider historical context for Clarke’s work by locating this latest ‘great transformation’ within the wider history of the professional sport in England and saying something about the links, as I see them, between sport, sociology and photography.

The three great transformations

Arguably, the arrival of the Premier League in 1992 marked the third great transformative moment in the history of English football. The first had occurred near the very start, as association football in England professionalized in the late-1800s, thus finally disentangling itself from rugby football and its public-school roots, where the enthusiastic ‘hacking’ of opposing amateurs continued to define masculinity for English male social elites.Footnote4 Instead, the less brutal association game quickly spread downwards from 1870, to working people and the urban middle-classes, as the more civilized version of the ‘football fever’ swept north and across the British nation. Women who wanted to play, however, were summarily brushed aside, save for a rapid but brief development spurt during and just after the First World War, a spike which ultimately and paradoxically led to an FA ban. Women’s football in Britain would suffer a near 50-year hiatus as a result.Footnote5 Patrician industrialists and Muscular Christians founded local men’s football clubs in late-nineteenth century Britain and they hired players for their Scottish, northern and midlands strongholds on a swelling wave of Victorian civic pride and ambition. Stadiums were rapidly built as attendances grew, and local cross-class partnerships and local partisanship was duly stoked, eventually even in parts of previously rugby-playing London.Footnote6 Aided by an extensive national rail network and an increasingly centralized news media, a popular national professional sport was starting to be born.

The second great transformation in the English game arguably occurred in the early 1960s, rooted in the lifting of the parsimonious maximum wage for players, the sprouting of national youth cultures and their influence on player style and fan practices, and the growing public interest in European club competition and its limited, but novel, televised football offer. All this helped transform some elite British footballers, for the first time, from sporting working-class heroes into authentic national celebrities, sportsmen who were less contained and relatively unconstrained by the traditional habitus of the domestic game alone.Footnote7 England World Cup-winning captain, Bobby Moore, for example, became an urbane and authentic English icon, but a charming, sometimes truculent, young Irishman, Manchester United’s mercurial winger, George Best, was probably the first truly young and transgressive professional footballer of the new era of consumer culture.Footnote8 Best’s off-field persona jarred violently when pitched against the wholesome decency of his 1950s’ era Manchester United team-mate and England hero, Bobby Charlton.Footnote9 Here was the beginning of postwar mass consumption, characterized in elite British football by new lifestyle excesses and the performance of increasingly troubled youthful football masculinities, both on and off the pitch.

The deep background to the launch of the Premier League around thirty years later in the neoliberal climate of late-Thatcherism – the third great transformation – was growing opposition among the more successful English football clubs to what was argued to be an increasingly outmoded policy of distributing centrally generated funds across all 92 Football League clubs.Footnote10 These top clubs were also chafing at the historic restrictions placed by the national Football Association (The FA) on the capacity of club shareholders and volunteer chairmen and directors to treat English professional clubs more like their own businesses, out of which profit might even be made.Footnote11 The parlous financial state of the sport and these new free market ideologies decreed that the English game required ‘modernisation’, including paid directors and increased shareholder dividends, as well as beginning to treat its followers more as discerning ‘customers’ rather than as committed, largely local and overwhelmingly male, working-class supporters. The trigger-point for this transformative change, however, was provided by falling attendances following a series of 1980s’stadium tragedies involving English fans, which also meant that, from 1985, English clubs were briefly ostracized from European competition.Footnote12 This chaotic and damaging period culminated in the Hillsborough Stadium disaster of 1989, which resulted in the deaths of 97 Liverpool supporters, crushed after police mismanagement of the crowd at an FA Cup semi-final fixture in Sheffield.Footnote13

The impact of the Hillsborough inquiry and a first meeting

The official inquiry report into events at Hillsborough, chaired by Lord Justice Taylor (Citation1990),Footnote14 surprised Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government by refusing to focus narrowly on the ‘facts’ of the disaster, as earlier football inquiries had done. Instead, Taylor demonstrated a much wider grasp of the weak and conflictful governance of the sport in England, and of the poor facilities offered to those who typically watched it, the sport’s active and loyal, but badly served, supporter base. He also understood that football had real cultural value, not a given, by any means, for an English High Court judge. Taylor concluded that English football urgently required improved stadia, better customer services and more coherent leadership, though dissenting voices remained, not least among those organized fan groups who sensed an early clarion call towards possible gentrification.Footnote15 Taylor’s key stadium recommendation – replacing standing terraces with seats at top British clubs – had been pressed on him by English football’s governing bodies, who wanted a completely new direction for a sport long-plagued by weak finances, cultish hyper-masculinity, overly-intensive rivalries, racism and hooliganism.

The FA in England, supported by the larger professional clubs, eagerly sought to fill the power vacuum in the immediate and inchoate aftermath of the 1989 disaster and it quickly (if rather surprisingly) sanctioned the new breakaway league. As if to confirm some fans’ fears, The FA’s own commercial advisors argued that the English game should follow a new route favoured in the leisure industry, by actively marketing the sport to consumers from higher social class backgrounds, potential recruits who would likely lack the traditional ‘psychological baggage’ of ingrained place and family ties with their chosen clubs.Footnote16 This, it was argued, promised a brighter future for a sport which had been in an extended period of crisis. Potentially at least, English football would now no longer be tied to its historic working-man fan base, but it could extend its reach into new markets. However, resources would have to be found to fund a new national stadium modernization project – Scotland and Wales were also included – a programme of improvements and new builds designed to attract these, thus far unaligned, high-spending ‘consumer’ fans. This national regeneration plan for football in Britain was likely to cost more than £500m in the first year. A levy on football betting, new satellite TV income, and increased corporate support and sponsorship, would all have a role to play here. Marketing lessons from the USA on club merchandising and fan segmentation would further have a major impact on how elite English football clubs would relate, commercially in future, to their new fan base. But another question immediately followed: how would such a dramatic set of social, cultural, architectural and economic changes to British football after a century of relative stability as the national sport, be adequately recorded and reported upon?

I first met the photographer Stuart Roy Clarke in the early 1990s, just as these extraordinary events and processes in British football were beginning to take hold. I had no idea who he was. At that first meeting, Clarke confided that he had recently graduated from art college, before moving into photo-journalism for local newspapers in his home town, Watford. But he also had a local football background; his father was a key figure in junior football in Hertfordshire, and the schoolboy Clarke had often bunked off Saturday lessons at his independent grammar school to watch a rising Watford FC compete under the leadership of the later England manager, Graham Taylor. This initiation period included a sobering, losing family visit to Wembley Stadium for the 1984 FA Cup final: Everton 2, Watford 0.

The young Stuart Clarke soon decided that often much more interesting than events on the pitch were the antics and characters present in the Watford crowd, and among the club’s rival fans. From the late-1980s he began taking his camera to games and to make his own photographic record of the menagerie of Britain’s varied clans of football supporters and the eyesore stadiums to which they seemed to be so deeply, and mysteriously, attached.Footnote17 He was already on to what was to become his Homes of Football journey, recording and reporting on stadium life from ground level and from all around Britain, on what was by then a rapidly metamorphizing fan and stadium terrain.Footnote18

In the early 1990s, I was a young sports sociologist based in Leicester. I was someone who had learned to be taut with anxieties about methodological purism and ethics in my own research; I had spent much of my early academic life studying deviant fans and then, agonizingly, trying to write coherently about the experience. Clarke, I picked up on immediately, seemed much more relaxed, somehow more at ease in his approach to mixing with, and imaging, his own football subjects. It was clear to me from the start that he was an enthusiastic and skilled fan watcher. Photographers, as researchers, invariably have to collaborate – a real and undervalued skill – because taking a photo always entails some sort of negotiated relationship between the person making the image and those being pictured.Footnote19 In those early encounters I envied Stuart Clarke, and his seemingly effortless access to the culture, his artist’s eye, and especially his jaunty, optimistic confidence, which he partly derived from his background and the privilege of being able to ‘hide’ behind his camera. Ethnographic academic research on urban, cultural and sporting matters seemed so unsure and so testing, so rigid, by comparison. And it would get worse for academics, of course, as the grim surveillance work of university ethics committees started to kick in.

Sport, photography and sociology

In 1839 the French artist and physicist, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, publicly announced a new image-making process, one which he called the Daguerreotype. The early development of photography largely coincided with the rise of organized sport in Britain as a significant new form of social activity. Sporting photographs as portraits were produced from very early on in Scotland, but later, as the technical capabilities of the medium developed, new visual possibilities opened up and photography began to explore the more explosive movement of sporting bodies in action.Footnote20 Later, too, photographic approaches to sport were used to document, expose, and critique social issues. Images of poor children playing football and cricket on slum streets of post-Second World War English cities, for example, were often used to signify both social integration and impoverished exclusion.Footnote21 Press images of the transgressive activities of British football fans would later eventually fulfil a broadly similar role in documenting some of the hedonistic pleasures of marginalization and national excess.Footnote22

Sports photography, while often condensing an event into one spectacular image or moment, is also part of an ongoing practice of understanding and evaluating the wider aesthetic or moral qualities of sports events and those who attend them. Stuart Clarke’s body of photographic work is perhaps best located in this context; as part of an established British social realist documentary photographic tradition, but also one influenced by aspects of expressionist visual media. I soon learned that Clarke was embarking on his own project to capture key features of British fan culture and to record its places and spaces of communion at a peculiarly uncertain and liminal moment in the history of the sport.

For most social science researchers at that time, the suggestion that visual media typically construct, select and possibly manipulate representations, or interpretations, of reality – and that ‘the camera always lies’ – was pretty much taken as a given. Words and description, if properly managed, could do a much more faithful job. Nevertheless – and perhaps a little naively – I concluded that Stuart Clarke’s photographs of a British football culture on the very cusp of its third great transformative change seemed to say much more that was, in some importance senses, ‘true’ about the sport and its people than my own words, often painfully eked out and vigorously contained, coughed up within a limiting, jargon infested, academic sociological frame, ever could. It is also a truism, of course, that, notwithstanding their subjectivity, photographs can show characteristic attributes of people, objects and events that can elude even the most skilful writer.Footnote23 Even with hindsight and decades of experience of research, I think I am still broadly convinced by aspects of this view, even though, particularly in the era of digital malfeasance and social media tomfoolery, our expectations of photography’s evidentiary capacity probably remain far too high.Footnote24

If sport and photography has had a lengthy, and sometimes fruitful, history, then relations between photography and sociology have typically fared rather less well. As Douglas Harper (Citation1988) famously pointed out, it may be that forms of visual sociology have traditionally been discredited by social science academics, perhaps because everyone can (and does) take photographs.Footnote25 As part of its professional ethos, it seems that sociological methods must be seen to be both mysterious and difficult, particularly compared, for example, to the work of lay researchers, journalists and other documenters. Photographs, by contrast, could be produced by ‘amateurs’ almost without effort, so how can they possibly be useful as an effective sociological tool? Sociologists have typically, too, underplayed the capacity of the photographic image to pack useful information into an efficient and reliable format, one which allows the collating and recording of the sort of visual data desirable or necessary for mapping out narrative ethnographic studies. The way photographs can communicate in the manner of art also opens up entirely new possibilities for phenomenological sociology.Footnote26 However, it took some time for sociologists to recognize – as anthropologists had – that visual research methods could be used to uncover the implicit knowledge contained in everyday practices, by focusing the lens intensely on the ordinary and banal elements of people’s lives.Footnote27 Moreover, using photographs could also offer social science researchers the opportunity to reflect more adequately on what they had encountered in their fieldwork, as well as on their own relationship to the field.Footnote28 Sociology, it was clear to Harper and others, needed to change its attitude to using visual tools.

Back in the early 1990s, when Clarke and I first met, such interdisciplinary revisionism was still very much on the academic drawing board, though my first book, on England fans abroad, already contained illustrative photographic images, mainly culled from press sources.Footnote29 Stuart Clarke, for his part, was particularly enthusiastic about the way music and football were beginning to synergize in Britain in the early 1990s. Football-supporting Brit-pop bands were about to flower, and the sport was slowly reconstituting and recovering its cultural confidence – and generating overt support from ‘cool’ musicians, post-Hillsborough, with the launch of the glossy new Premier League. The writer Nick Hornby had also recently produced Fever Pitch, a compelling and intelligent autobiographical account of masculinity and relationship challenges in the life of a middle-class Arsenal football supporter.Footnote30 English football was recuperating, but it was also changing at last, breathing different air by opening itself up to wider socio-cultural influences.Footnote31

I soon discovered that Stuart Clarke already regularly took photographs of crowds at Glastonbury and other music festivals, and that he immediately recognized the links between the theatricality and jouissance of music enthusiasts and revellers and the collective, often ecstatic, performance of fandom among typical football followers. The full-colour, large scale photographs of fans and of aspects of British football stadia he brought for me to examine at that first encounter were like no images of the sport, its people, and its architecture, that I (or, I would argue, anyone else) had yet seen. Except for art museums and art catalogues, it is hard to identify any other field of visual culture in which the images are praised as often for their pictorial qualities and their aesthetic pleasures as in sports.Footnote32 But Clarke was no simple representational photographer or nostalgist, an easy route to take at a time of rapid change in any valued cultural field. In my estimate, his photographs were both evocative and respectful; they demonstrated an immediacy, an authenticity and an intimate closeness to the culture. Very little in them seemed to be planned or staged. Clarke worked then – as he still works today – in film; he seldom uses filters or photographic tricks, and he generally takes one shot only.

Recording sporting change

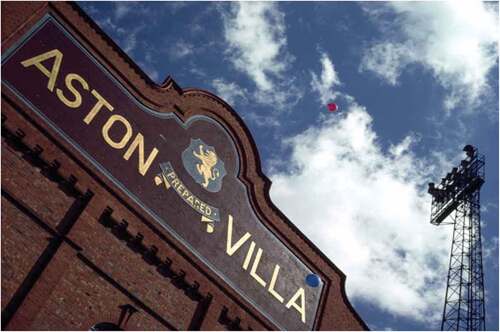

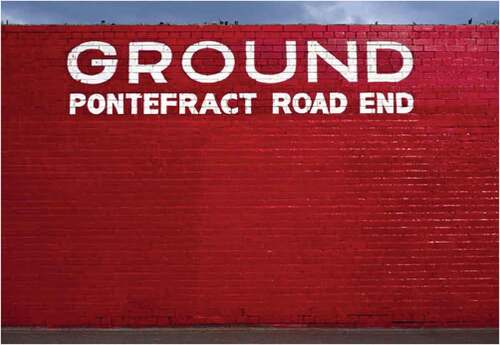

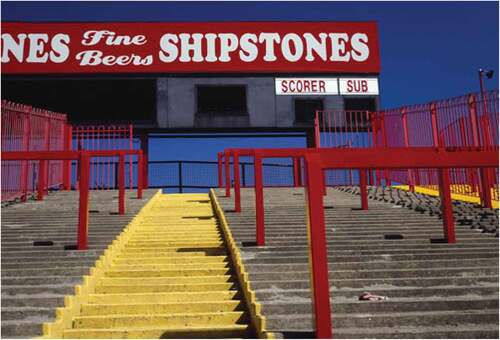

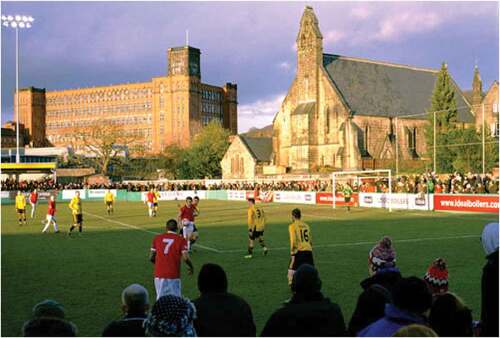

As a result of our first meeting, I helped to get Stuart Clarke a connection with the Football Trust, the public body then charged with distributing small public grants for the post-Hillsborough national stadium modernization programme in the UK. This proved to be a profoundly important confluence of interests. As a result of that link-up, he secured the commission to chart the outcome of this significant round of public spending, including the transformation of the national stock of elite British football stadia. His turned out to be an inspired appointment, especially for a sport that had so routinely undervalued or disregarded its own history. Few major British football clubs at that time kept records or housed even amateur historians; none had convincing museums – times have changed. Certainly, very few clubs were likely, faithfully, to record their own immediate past at this critical juncture or to chart, through photography or other means, the road to this challenging new future. Clarke was carefully recording the iconography and architecture of historic British football stadia before their potential destruction; he was on hand to report on the demolition of some of British football’s most historic twentieth century edifices (See ).

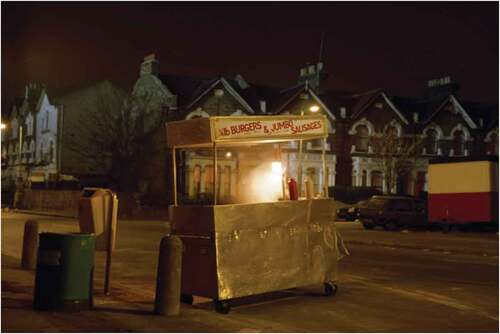

He, specifically, had developed an eye for featuring what might seem to outsiders to be rather unlovely architectural features of the kind which often define historic local sporting spaces: sagging stadium storage sheds; shabby but distinctive ticket offices; grisly food outlets; stretches of weed-infested terracing. But he was also skilled at capturing the abstract beauty of vivid newly-painted stadium walls and stairwells. In short, these were the buildings, passageways and spaces that fans and non-fans alike might only see in passing or regard as barely functional eyesores, some of them awaiting likely (and probably deserved) demolition. Stuart Clarke’s photographs somehow revealed their wider place-located socio-cultural valued and historic significance, as if they should be preserved at all costs, perhaps even listed as national monuments. He was becoming the national visual record keeper of the sport, its homes and its people, at a critical moment of convulsive change (See ).

Clarke’s evolving body of photographic work, especially as it began to cover the story of less-considered lower league football clubs and places in Britain, complements rather well recently published accounts of football ‘groundhoppers’, those typically older male fans in Britain and elsewhere who avidly ‘collect’ lower league or non-league grounds by visiting – usually only once – these distinctive and often poorly-appointed, but satisfyingly obscure and welcoming, football locations.

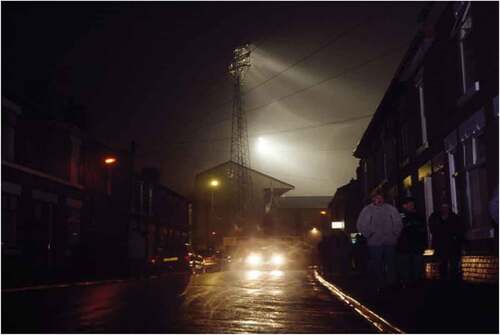

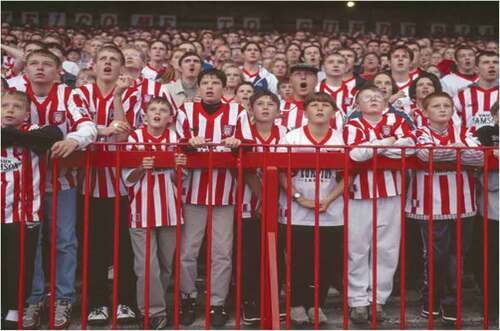

Groundhopping can offer native lessons in sporting history and culture, insights on male sporting companionship, shared experiences often for fathers and sons (and occasionally mothers and daughters), and a more ‘traditional’ experience of a football watching encounter, one that can often spark new connectivities beyond place ties, and which also evokes significant familial memories.Footnote33 Attending lower-level matches among small crowds allows groundhoppers greater opportunities for sociality because rival supporters can often mingle together. Security is less intrusive as supporters can typically stand and walk around the ground to take up preferred positions, thus contributing to the reclaiming of a sense of personal and collective identity through mutuality and sporting ties.Footnote34 Clarke’s photographs of lower league fans often captured their defiant idiosyncratic localism. Building out from his initial contract with the Football Trust, over the next 30 years Stuart Clarke went on to develop a remarkably evocative and extensive portfolio of photographs of fans and places, often captured at lesser outposts. Clarke’s images of British football culture and venues in a period of change in the early 1990s are routinely poignant, frequently humorous, and typically respectful of place and his human subjects. As well as places and fans, there are also studies here of mainly lower-level ‘hidden’ club employees and service workers. Unlike many sociologists or other academics, his interest as a chronicler of a sport in transformative change was not in the occupational lifestyles of the players, or even in the spectacular youth sub-cultures of the stadium. Some of his best work was often completed outside or around the main event and was made up of pictures of ‘ordinary’ individuals, or small groups of fans, typically men, women and children who were making something socially significant out of belonging, tradition and place ties through their sport (See ).

Human geographers use the concept of topophilia – the love of place – to describe places and spaces that have a, sometimes irrational, but deep emotional meaning to humans.Footnote35 Football fans in Britain, in particular, seem to have especially strong emotional ties to the material environment – to their ground. In a period of uncertainty brought about by the threat of feelings of ‘placelessness’, and the ontological insecurity inherent in globalization and the decline of local industries as reliable place anchors and sources of dignity, many traditional football grounds and football clubs in Britain were becoming increasingly important sites in so-called ‘left behind’ towns and cities. Many grounds have considerable historical and architectural merit, others less so. But they are all venues for collective expressions of meaningful localism and belonging, especially perhaps for working-class men.Footnote36 In the pre-Premier League era, when most British football clubs were locally owned and maintained on shoestring budgets – many still are today – fans often paid in public bouts of fundraising for the building of new terraces and stands at their clubs, which they rightly learned to call their own.Footnote37 For Clarke:

Most football fans have a central message: no matter how shambolic you might think our ground is, we really LOVE this place. Most football grounds were not set up to be especially beautiful palaces, but they were always a safe space for locals. A spiritual place. A place of pilgrimage. An altar, of sorts …. A stadium is a kind of sacred gathering ground, a destination, an Oz at the end of the rainbow. Just as Glastonbury has come to signify much more than an ancient religious centre, a football ground is active and earthquakes of the human spirit regularly happen there.Footnote38

As a result of this emotional and material investment, the regulars at British football grounds grew to really appreciate – even to love – the incongruities and quirks of their surroundings which were both stable and familiar, and often probably attractive only to them. Traditionally, too, British football fans had long learned to accept stadium defects and discomforts – hazardous stairwells, uncovered terraces, terrible toilets, impossibly crowded food outlets – as expressions of necessary fan devotion and suffering, a strangely comforting reminder of the narcissistic nature of local distinctions, and a distorted message about why sport and place ties really matter. It was certainly seemed easier to suffer stadium deprivation than willingly embrace change. In fact, in accepting the status quo and in opposing potential new directions, these conservative fans probably colluded in underplaying the growing risk of their masculinist football spaces that had been left to decay through years of lack of investment and a proper duty of care, perhaps offering the backcloth to the 1980s’ stadium disasters.Footnote39

However, accepting that major change was probably inevitable also raised difficult questions for fans in England in the Premier League era about increasing television and corporate influence at elite levels, and notions of lost heritage and breached trust lower down the club pecking order. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that many of today’s football supporters have a deep respect for the history and tradition of the British version of the sport, including maintaining its links to local communities. But fans also seem to approve, in general terms, of facility improvement and new services, whilst harbouring, at the same time, contradictory perceptions that ‘football is not what it used to be’ or that, ‘It is losing its roots and its appeal.’Footnote40 Despite these complex dialectics, such fans continue to actively support their local clubs, the neoliberal litmus test for any successful sporting business. So, is this simple nostalgia? The game’s authorities may tend towards complacency here, given the bourgeoning Premier League attendances and English football’s lucrative worldwide consumption, but this may also ignore the obvious (and growing) tensions that exist between global commerce and local connectivity.

The football stadium as ‘home’

As important parts of our visual culture, impressive new football stadia or established historic ones are, for football fans and even casual observers, places that establish a certain hegemonic status as one of the local ‘sights to be seen’. This was also true in the Victorian era. Note how football fans, travelling on trains today through unfamiliar locations, often strain for a passing sight of a floodlight pylon or a stadium building. It is these places that emerge as destinations for football tourists, pilgrimages for groundhoppers and others, spaces where romantic photographs of the landscape constitute the ritual by which the place is consecrated.Footnote41 In the Premier League era, a new generation of museums at club stadia now commodifies the past for a sport that has only recently discovered that its history actually matters to people and, more importantly perhaps, that it sells. But, above all else, for many people a British football stadium, at any level, is literally our home ground. It is a place where the collective and uniformity can still trump rising individualism, where generational memories are created and reside, and where memorials to the imagination of lost worshippers can best be respected (See ). Supporter flags inside stadia, or personalized ‘fan walls’ with the names of subscribers outside, can commemorate the lives of committed fans, still present or now gone. The stadium is also a space where deep feelings are overtly and regularly on show at a time when most developed Western societies feel overly-controlled; a place for expressions of wild abandon and occasional abuse, and a site where grizzled working men can still hug total strangers, and even cry.

A football stadium, Clarke seems to assert through his own work, is a kind of therapy centre for working people; a place for solidarity, excitement and intimacy. Sunderland FC’s Roker Park opened its gates at lunchtimes on non-matchdays to allow local workers a stress-free moment in the stands, surveying the empty ‘field of dreams’ while enjoying their food and a bout of quiet contemplation. ‘You are close to the public,’ French shaman and footballer Eric Cantona commented in the early 1990s, comparing English football grounds with the more emotionally and physically detached venues abroad. ‘It is warmer. There is room for love.’ Stuart Clarke very obviously identifies and celebrates the significance of the local football stadium in the lives of many British people, even at the very moment of change. He argues through his work that it has a unique, organic role in sewing together the detailed tapestry of the national game – indeed, a vision of Britain itself (See ). But he also notes the attractions of stadium spaces to foreign enthusiasts, visitors who come to Britain primarily, it can so often seem, in search of meaningful place identity, ludic history, and a reliable version of sporting authenticity. Here, an overseas’ visitor’s intrigue and respect can turn the sporting place into a sacred space, one consecrated by certain tourist rituals, a space that generates its own sense of order and security.Footnote42 As Clarke himself puts it:

What distinguishes this country is that there are SO MANY clubs and identities, cheek by jowl with the next. We value them all as part of the national football story …. A dozen Norwegians arrive at Grimsby Town’s Blundell Park from across the North Sea and they are soon taking selfies against the plain old terraced houses neighbouring the ground. Not everything is perfectly arranged in the national football grid, of course, it’s all a bit higgledy-piggledy. It’s like a mad jigsaw – where is the plan? There may not have been one. Football just sort of happened in this way; it took root around the nation. The locals in Cleethorpes feel honoured, of course, that visiting Norwegians want to photograph their old houses – they even sweep the front step. Footnote43

Always with a paternalistic eye for the quirky and humorously absurd in the game’s audiences – those early fixtures spent at Watford FC were an inspiration, where a string-vested ‘Man with a Bag’ paced the home terraces, yelling and perpetually threatening to leave – Stuart Clarke curates visions of British football’s barely hidden, gentle madness: young kids peering over or round walls for a sight of the play; supporter dogs apparently avidly watching matches (See ); a man seemingly paid to hold back time, with a stick on a stadium clock as kick-off approaches; older supporters habitually leaning against friendly pylons or stanchions, or else armed in anticipation of excitement with tiny parcels, party poppers or ‘borrowed’ toilet rolls; freezing children decked out in garish replica kits caught up in a thunderstorm waiting for buses home; ranks of fans strangely and intensely becalmed, or else in advanced moments of agony or ecstasy; supporters almost literally seeing the future unfold as a new stadium evolves on the near horizon. As a cultural performance grounded in pictorial reproduction, Clarke’s photographic ritual, in this context, knowingly and carefully employs the bodies of fans as resources and marketplaces for the production of social meaning.Footnote44

Gender identities, British football and social change

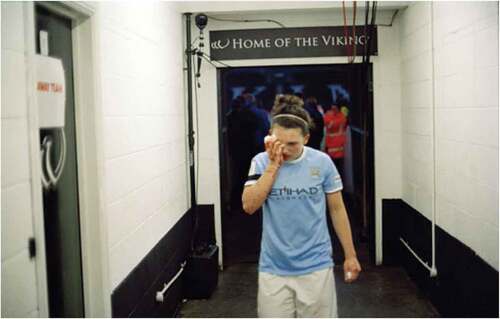

In some of his more recent football photographs, Clarke seems to be responding, albeit implicitly, to concern that in recording the loss of a specifically British version of postwar football culture he is at risk at the same time of appearing to give primacy to an outmoded and excluding version of white, classed hegemonic masculinity as the game is changing. I understand the charge, but think it is a little unfair. Despite British football’s overwhelmingly white, male fan base in the early 1990s, Clarke’s later work actually features a wide range of football people, women as well as men (See ). In fact, I would argue that Clarke has always been keen to elucidate in his photographs a critique of British football’s dominant patriarchy, by pointing out that in the back spaces and on the margins of the sport, it was mainly poorly paid women who were (and are) undertaking the hidden service work, while male players and directors (and sometimes fans) hogged the front stage and the television screens (See ). Gendered inequalities persist of course: in 2017 only two Premier League clubs (out of 20) offered their caretakers, cleaners and catering staff (mainly women) even a living wage, when the combined turnover of the elite clubs was some £3.6 billion.

This highly visible inversion of the traditional football hierarchies – the role of workers and fans highlighted and represented over those of directors and players – is central I would argue to the ethos of Clarke’s football project and it has been so, right from the start. However, recording the intensive, traditional and class-based masculinity of the culture, a feature which is at the historic heart of the intimate connections he draws between the factory, religion and the game in Britain, may also seem, on occasions, to carry with it an unconscious gender and ethnicity bias (See ). In his more recent work, Clarke manages to do more to centre the changing demographics of the twenty-first century British football stadium, as the culture of the sport has been opened up to new forms of diversity and new challenges to British football’s long-established dominant working-class male order. As a result, women feature more routinely in his recent photographs as active and committed fans and players today, key figures in the evolving new versions of the professional sport in Britain in the twenty-first century.

Clarke has also, more recently, been profiling the developing women and girls’ football in England, even as the elite women’s game there has only, belatedly, professionalized.Footnote45 Despite recent exposure in major international tournaments, top women’s players in England remain low earners and highly accessible elite athletes, competitors who display their world class talents mainly off the television screen, often in minor stadia and on muddied fields in front of audiences numbered in hundreds, rather than the tens of thousands who routinely attend the cossetted men’s game (See ). Nevertheless, we may yet, as some academics claim, be in a new era for women’s sport in Britain, one which urgently requires football to develop its own memories and visual narratives, images that can eventually challenge what are increasingly irrelevant media comparisons with men’s football.Footnote46

Conclusion

Stuart Clarke’s work, I would argue, is a major and important exercise in sporting social documentation, capturing a key phase in the late-modern development of the British game. But he is also a commercial photographer which means, of course, that he publicly displays his photographs online, in forums and exhibitions, and he sells them, often without the explicit consent of the individuals photographed. This is an important issue in sports photography because Internet technology today allows for the effortless reproduction and distribution of images, potentially rendering the subject powerless over the communication of their own image; what should be private can swiftly become public, and on a global scale.Footnote47 This is something which would certainly be regarded as ethically dubious for academics and others.Footnote48

Clarke claims that no fan, or any other human subject, has ever protested about featuring in his projects – and that he would withdraw their image if they ever did. In fact, and as might be expected given the media vortex in which we all now live, the opposite is more usually the case. Fans and others do sometimes excitedly self-identify at his public exhibitions and Clarke recently began a ‘Where are they now?’ search for some of his 1990s’ subjects on Twitter – and with some success. Indeed, the National Football Museum in Manchester in 2021 showed a video loop of interviews of Clarke’s fans today, reflecting enthusiastically about their presence in his photographs that may have been taken by him over 30 years before. I would only add here that the necessary ethical reflexivity typically required in academic research, in terms of awareness and sensitivity and a high degree of honesty and truthfulness in dealings with others is, I would say, always apparent in Clarke’s negotiations, interactions with, and representations of, his own subjects, despite these important, wider ethical concerns. The fact that he is not employed as a salaried sports photographer or journalist by any agency or news outlet also means, I think, that he avoids that unfairly stereotypical depiction of such professionals as egotistical, socially ignorant, overly aggressive, and highly competitive.Footnote49

In my view, Clarke’s artist’s eye, his sensibility, and his knowledge and enthusiasm for the game and its people at all levels, perpetuates – intensifies even – as he ages. Now in his sixties, he still travels most weekends to football locations all over Britain and at all levels, convinced he has not yet documented the complete story. Indeed, and following on from the insight of Juha Suonpää,Footnote50 one could legitimately argue that Clarke’s 30-year ethnographic photography project on British football is a process in which he acts, simultaneously, as photographer, researcher and tourist. I would also contest that Clarke’s work provides an indispensable visual record of late-modern British football and its people at the very moment the sport has been undergoing seismic change. He has a restless and highly informed gaze, searching for continuities in the culture, of course, but also for something different, something new, insights that he can play back to inform football enthusiasts and researchers alike, about how and why we imbibe and play, write about, and live our lives through the prism of, the world’s most popular team sport.

In his most recent published work, Clarke combines the written word with imagery as a means of exploring, with the current author, British football’s heritage and its contemporary condition in a series of recorded conversations, using his and other’s photographs as a guide.Footnote51 Stuart Roy Clarke, as he did when we first met in Leicester almost thirty years ago at a very different moment in British football’s history, still manages to persuade one that he can find that revealing image, that photograph, and that he can capture the moment which documents the prevailing narrative better than a mere scribe can. Generally speaking, I think he makes a pretty compelling case.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Willliams, ‘Game changer’.

2. Boyle and Haynes, Football in the New Media Age.

3. Williams, ‘The local and the global in British football’.

4. Curry and Dunning, ‘The problem with revisionism’.

5. Jean Williams, ‘An equality too far’.

6. Korr, ‘West Ham United Football Club and the beginnings of professional football in East London’.

7. Critcher, ‘Putting on the Style’.

8. Bairner, ‘In balance with this life, this death’.

9. Mellor, ‘The genesis of Manchester United as a national and international super club’.

10. Williams, ‘Protect me from what I want’.

11. Historically, football in England has had two main organizations governing the sport: The Football Association, representing the traditions of the public schools and amateurism, which today manages the disciplinary side of the sport, local football and the England national team; and the Football League, and later also the Premier League, which deal primarily with the interests of the professional clubs. The FA has traditionally sought to limit the commercial activities of the professional clubs and the ambitions of owners to profit from their involvement. Their influence in this respect has waned considerably in recent years, and the values and perspectives of these groups have routinely collided in search of an approach which can be said to be, ‘for the good of the game.’

12. Williams and Gould, ‘After Heysel’.

13. The Hillsborough disaster was followed by a 23-year campaign by the families of those people who lost loved ones for the ‘truth’ to be told about the causes of the disaster and for ‘justice’ for those who had lost their lives. Unusually, an expert panel was eventually appointed by a Labour government, in 2009, and it reported in 2012, exonerating fans and highlighting the mistakes on the day made by the host club and the South Yorkshire police which contributed to the terrible loss of life.

14. Taylor, The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster.

15. Brick, ‘Taking offence’.

16. The FA, Blueprint for Football. FA permission was required to allow the Premier League to be formed. This was a moment when the key organizations in the English game jostled for power. The FA, was approached by a caucus of larger clubs. Believing that by sanctioning a breakaway professional league it could safeguard its own position and achieve greater support from the elite English clubs for the England national team, The FA sided with this new commercial project. It was a crucial miscalculation: the Premier League today is effectively run by its member club chairmen. The FA hired the Henley Centre for Forecasting to outline, in its Blueprint, the new marketing route the FA Premier League should take. The rest, as they say, is history.

17. Bale, ‘The changing face of football’.

18. Clarke, The Homes of Football.

19. Rose, ‘On the relation between “visual research methods » and contemporary visual culture’.

20. O’Mahony, ‘The art and artifice of early sports photography’.

21. O’Mahony, ‘Through a glass darkly’.

22. Williams et al, Hooligans Abroad.

23. Prosser and Schwartz, Photographs within the sociological research process’.

24. Winston, ‘The camera never lies.’

25. Harper, ‘Visual sociology’.

26. Ibid.

27. Rose, ‘On the relation between “visual research methods » and contemporary visual culture’.

28. Emmel and Clark, ‘Learning to use visual methodologies in our research’.

29. Williams et al, Hooligans Abroad.

30. Hornby, Fever Pitch.

31. Millward, The Global Football League.

32. Stauff, ‘The assertive image’, 62.

33. Connell, ‘Groundhopping’.

34. Williams and Caulfield, ‘Why do I want to go and watch that?’

35. Bale, ‘The changing face of football’.

36. Mainwaring and Clark, ’We’re shit and we know we are’.

37. Inglis, The Football Grounds of Great Britain.

38. Clarke, The Homes of Football, 26.

39. Johnes, ‘Heads in the sand’.

40. Welford ‘A healthy future?’

41. Suonpää, ‘Blessed be the photograph’, 79.

42. Ibid., 80.

43. Clarke, The Homes of Football, 27–8.

44. Suonpää, ‘Blessed be the photograph’, 84.

45. Dunn and Welford, Football and the FA Women’s Super League.

46. Petty and Pope, ‘A new age for media coverage of women’s sport?’

47. Keats and Keats-Osborne, ‘Overexposed’, 645.

48. Pink, Doing Visual Ethnography.

49. Oates and Pauly, ‘Sports journalism as moral and ethical discourse’.

50. Suonpää, ‘Blessed be the photograph’.

51. Clarke, The Game.

Bibliography

- Bairner, A. ‘In Balance with This Life, This Death: Mourning George Best.’ International Review of Modern Sociology 32 (2006): 293.

- Bale, J. ‘The Changing Face of Football: Stadium and Communities.’ Soccer& Society 1, no. 1 (2000): 91–101. doi:10.1080/14660970008721251.

- Boyle, R., and R. Haynes. Football in the New Media Age. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Brick, C. ‘Taking Offence: Modern Moralities and the Perception of the Football Fan.’ Soccer & Society 1, no. 1 (2000): 158–172. doi:10.1080/14660970008721256.

- Citizens UK ‘Premier League Clubs in Living Wage Shame despite £3.6bn Turnover.’ 2017. https://www.citizensuk.org/premier_league_clubs_in_league_of_shame

- Clarke, S. The Homes of Football. London: Little, Brown, 1999.

- Clarke, S., (with John Williams). The Game. Liverpool: Bluecoat Press, 2019.

- Connell, J. ‘Groundhopping: Nostalgia, Emotion and the Small Places of Football.’ Leisure Studies 36, no. 4 (2017): 553–564. doi:10.1080/02614367.2016.1216578.

- Critcher, C. ‘Putting on the Style: Aspects of Recent English Football.’ In British Football and Social Change. Ed. J. Williams and S. Wagg. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1991: 67–84.

- Curry, G., and E. Dunning. ‘The Problem with Revisionism: How New Data on the Origins of Modern Football Have Led to Hasty Conclusions.’ Soccer & Society 14, no. 4 (2013): 429–455. doi:10.1080/14660970.2012.753537.

- Dunn, C., and J. Welford. Football and the FA Women’s Super League. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Emmel, N., and A. Clark. ‘Learning to Use Visual Methodologies in Our Research: A Dialogue between Two Researchers.’ FQS: Forum Qualitative Social Research 12 (2011). http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1508/3147

- Harper, D. ‘Visual Sociology: Expanding Sociological Vision.’ The American Sociologist 19, no. 1 (1988): 54–57. doi:10.1007/BF02692374.

- Hornby, N. Fever Pitch. London: Victor Gollancz, 1992.

- Inglis, S. The Football Grounds of Great Britain. London: Collins Willow, 1991.

- Johnes, M. ‘Heads in the Sand: Football, Politics and Crowd Disasters in Twentieth Century Britain.’ Soccer & Society 5, no. 2 (2004): 134–151. doi:10.1080/1466097042000235173.

- Keats, P., and W. Keats-Osborne. ‘Overexposed: Capturing a Secret Side of Sports Photography.’ International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48, no. 6 (2013): 643–657. doi:10.1177/1012690212448001.

- Korr, C. ‘West Ham United Football Club and the Beginnings of Professional Football in East London 1895-1914.’ Journal of Contemporary History 13, no. 2 (1978): 211–232. doi:10.1177/002200947801300203.

- Mainwaring, E., and T. Clark. ‘We’re Shit and We Know We Are: Identity, Place and Ontological Security in Lower League Football in England.’ Soccer& Society 13, no. 1 (2012): 107–123. doi:10.1080/14660970.2012.627173.

- Mellor, G. ‘The Genesis of Manchester United as a National and International Super Club, 1958-68.’ Soccer & Society 1, no. 2 (2000): 151–166. doi:10.1080/14660970008721269.

- Millward, P. The Global Football League. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- O’Mahony, M. ‘Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Photography and the Visual Representation of Sport.’ Historical Social Research 43 (2018): 25–38.

- O’Mahony, M. ‘The Art and Artifice of Early Sports Photography.’ Sport in Society 22, no. 5 (2019): 785–802. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1431382.

- Oates, T., and J. Pauly. ‘Sports Journalism as Moral and Ethical Discourse.’ Journal of Mass Media Ethics 22, no. 4 (2007): 332–347. doi:10.1080/08900520701583628.

- Petty, K., and S. Pope. ‘A New Age for Media Coverage of Women’s Sport? An Analysis of English Media Coverage of the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup.’ Sociology 53, no. 3 (2019): 486–502. doi:10.1177/0038038518797505.

- Pink, S. Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media, and Representation in Research. 2nd ed. London: Sage, 2007.

- Prosser, J., and D. Schwartz. ‘Photographs within the Sociological Research Process.’ in Image-based Research, ed. J. Prosser, 115–130. London: Falmer Press, 1998.

- Rose, G. ‘On the Relation between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture.’ The Sociological Review 62, no. 1 (2014): 24–46. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

- Sounpaas, J. ‘Blessed Be the Photograph.’ Photographies 1, no. 1 (2008): 67–86. doi:10.1080/17540760701786964.

- Stauff, M. ‘The Assertive Image: Referentiality and Reflexivity in Sports Photography.’ Historical Social Research 43 (2018): 53–71.

- Taylor, P. The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster: 15 April 1989, Final Report. Cm. 962. London: HMSO, 1990.

- The, F.A. The FA Blueprint for the Future of Football. London: The FA, 1991.

- Welford, J., B. García, and B. Smith. ‘A Healthy Future? Supporters’ Perceptions of the Current State of English Football.’ Soccer & Society 16, no. 2–3 (2015): 322–334. doi:10.1080/14660970.2014.961380.

- Williams, J. ‘The Local and the Global in British Football and the Rise of BSkyB.’ Sociology of Sport Journal 11, no. 4 (1994): 376–393. doi:10.1123/ssj.11.4.376.

- Williams, J. ‘Protect Me from What I Want: Football Fandom, Celebrity Cultures and ‘New’ Football in England.’ Soccer & Society 7, no. 1 (2006a): 96–114. doi:10.1080/14660970500355637.

- Williams, J. ‘Game Changer: The English Premier League, Big Money and World Football.’ in The English Premier League: A Socio-Cultural Analysis, ed. R. Elliott, 163–184. London and New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Williams, J., and P. Caulfield. ‘‘Why Do I Want to Go and Watch That?’ English Non-league Football Fans in the Premier League Era.’ Sport in Society 23, no. 5 (2020): 901–919. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1591374.

- Williams, J., E. Dunning, and P. Murphy. Hooligans Abroad. London and New York: Routledge, 1984.

- Williams, J., and D. Gould. ‘After Heysel: How Italy Lost the Football “Peace.’ Soccer & Society 12, no. 5 (2011): 586–601. doi:10.1080/14660970.2011.599580.

- Williams, J. ‘An Equality Too Far? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives of Gender Inequality in British and International Football.’ Historical Social Research 31 (2006b): 151–169.

- Winston, B. ‘The Camera Never Lies: The Partiality of Photographic Evidence.’ in Image-based Research, ed. J. Prosser, 60–68. London: Falmer Press, 1998.