ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to analyse online expressions of rivalry and hate speech in relation to antisemitic and philosemitic discourse(s) in Dutch professional men’s football (soccer). We collected data from Twitter using the Twitter API and scraped Tweets relating to a match between the supposedly ‘Jewish’ club Ajax and its rival Feyenoord on 17 January 2021. A selection of the collected Tweets was analysed more in depth using narrative digital discourse analysis to interpret the Tweets. The research shows that antisemitic chants and slurs find their way towards the online domain, sometimes explicit and other times implicit. The analysis elaborates how these Tweets, while seemingly targeted towards the football rival, contribute to an exclusionary discourse in which being a ‘Jew’ is not wanted and contribute to the normalization and reproduction of antisemitism in football.

Introduction

Hate and (online) hate speech is often part of acting rites and rituals between rivalling football fan groups.Footnote1 These football rivalries are often described as opposition and competition with fan groups who support a different football club, and therefore share a different collective identity. The rivalry-related aspect of football fandom has been given growing attention, and research has shown that rivalries are unique and complex. Often, they are underpinned by social, historical and cultural factors.Footnote2 In the Netherlands professional men’s football is regularly confronted with antisemitic behaviour. Supporters chant ‘Hamas! Hamas! All Jews to the gas’Footnote3 and use ‘Jew’ as an insult or slur. This kind of behaviour is often attributed to rivalry with the Amsterdam-based club Ajax. Ajax is often casted as a ‘Jewish’ club and as such fans of rivalling teams such as FC Utrecht, Feyenoord and ADO Den Haag make antisemitic references towards Ajax to express their rivalry with the club. This kind of football-related antisemitic behaviour is reproduced in stadiums, bars, cafe’s but also onlineFootnote4 and can be understood as hate speech. In this article, we explore online expressions of rivalry and hate speech in relation to antisemitic and philosemiticFootnote5 discourse(s) in Dutch football.

Antisemitism in contemporary Dutch society is substantial, both online and offline.Footnote6 Recent research by journalists Van Gool and Van de Ven in cooperation with the Utrecht Data School, who analysed 1.3 million Tweets from 2019, shows that online antisemitism in the Netherlands is significant.Footnote7 This corresponds with observations made by CIDI (Centre for Information and Documentation Israel)Footnote8 which publishes an annual report on antisemitic incidents in the Netherlands. Recently, they have started to pay more attention towards online antisemitism and commissioned exploratory research into online antisemitism in the year 2019. This study found 1033 online expressions of online antisemitism.Footnote9 CIDI also claims that the division between antisemitism in the online and offline world is increasingly blurred; online expressions influence our offline daily lives.

Several scholars have argued that the internet and in particular social media – such as Twitter and Facebook – play an important role in many people’s daily lives.Footnote10 This applies also to football fans whose expressions of rivalry have extended from the physical world to online domains. Kholsa et al. analysed community rivalry in the football domain by examining hate content exchanged between supporters of Real Madrid CF and FC Barcelona.Footnote11 They found that rivalry between the two opposing communities often got expressed in the form of hate content on social media, especially during ‘controversial’ events such as important games. Their study looks at overt forms of hate speech using a lexicon of abusive words to detect Tweets instigating hate. They defined hate speech according to guidelines developed by Twitter and consider content that promotes violence against or directly attacks or threatens other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease as hate speech. Tsesis argues that hate speech is dangerous not only when it poses an immediate threat but also when it is systematically developed over time and has become a part of a culturally accepted dialogue.Footnote12 Studies have also shown that online hate speech can lead to hate and violence in the physical world.Footnote13 Making the detection of hate speech in online user generated content increasingly important.

In the English context, there is growing evidence of football-related online abuse.Footnote14 A recent study, for example, showed that, during the 2014/2015 season, 135.000 discriminatory posts were made on social media relating to the English Premier League.Footnote15 Kick it Out, England’s leading equality and inclusion organization in football tries to raise awareness for the growing problem of online abuse with the hashtag #stoponlineabuse. They also recently organized a social media boycott together with different English football governing bodies. During the weekend clubs across English football switched off their social media accounts to call for social media compagnies to do more to stop online abuse.Footnote16 In the Netherlands, football-related online abuse is not (yet) well researched or documented. In addition, online antisemitism has not yet been researched extensively either. While CIDI has made a first attempt, online antisemitism in the Netherlands remains inadequately documented.

With this paper, we contribute to the gap of knowledge on online football-related antisemitism in the Netherlands and online discrimination and hate speech in general. More specifically, we address how football-related antisemitic rhetoric is reproduced on Twitter. In order to understand online football-related antisemitism, we analysed Tweets posted in the weekend in which the allegedly ‘Jewish’ club Ajax and its rival Feyenoord played against each other on 17 January 2021. First, we will conceptualize social media, antisemitism and online hate. Secondly, we will explain the context in which football-related antisemitism prevails in the Netherlands and where the idea that Ajax is a ‘Jewish’ club comes from. After that we will address the rivalry between Ajax and Feyenoord and explain why this is relevant for understanding football-related antisemitism in the Netherlands. Then we reflect on the methods used. After which we will provide the analyses of Tweets posted in the weekend of Ajax-Feyenoord. Finally, we will consider the broader implications of our research and come to a conclusion.

Conceptualizing antisemitism, philosemitism and online hate

What we see in Dutch football is the reproduction of antisemitic discourse. The use and meaning of the term ‘Jew’ in Dutch football is complex. Similar to the English football context in which the derogatory term ‘Yid’ has taken on different meanings,Footnote17 ‘Jew’ has taken on different meanings in Dutch football. ‘Jew’ may refer to Ajax and Ajax fans, but it is also used amongst fans of various clubs to express rivalry towards other opposing teams or to insult the referee or the police.Footnote18 Supporters often explain their behaviour by arguing that they do not want to hurt Jewish people, but Ajax, the football ‘other’.Footnote19

While acknowledging the said intent to hurt the football ‘other’ and not Jewish people and the different meanings of ‘Jew’ in Dutch football, the question remains whether or not the behaviour of fans should be seen as antisemitism. Antisemitism is an age-old phenomenon with a complex history. It knows different forms and varies from outspoken threats to more subtle use of Jew as a negative epithet. As Seijbel et al. explain, hate or dislike of actual Jewish people is not a requirement for engaging in football-related antisemitic behaviour.Footnote20 Therefore, we have chosen to use the following definition of antisemitism as ‘Verbal or active manifestations of antagonism towards the Jewish group as such, irrespective of whether they are direct or indirect, intended or not’.Footnote21 This definition proves to be useful as it makes it possible for antisemitism to be manifested indirectly and also unintentionally.

In addition to antisemitism, philosemitism is a relevant term in this study as some Ajax fans have adopted ‘Jew’ or ‘Super Jew’ as a self-referent or badge of honour.Footnote22 Philosemitism can be understood as sincere sympathy for Jews but also as a mirror of antisemitism. Jews are appreciated or even glorified, instead of despised, envied or hated for the mere fact of them being Jewish.Footnote23 In that sense, philosemitism is often regarded as negative. Like antisemitism, it can serve certain goals, political or otherwise, that have nothing to do with Jews or Jewishness. Ajax supporters calling themselves ‘Super Jews’ or tattooing a David star on their body can be seen as a form of philosemitism. Football-related antisemitism (or philosemitism) is not always seen as ‘real’ antisemitism, as it is often regarded as football ‘banter’ and attributed to the rivalry with the allegedly ‘Jewish’ club Ajax.Footnote24 In the approach we take, however, football-related antisemitism is considered ‘real’ in the sense that it is an exclusionary discourse. While antisemitic banter may be unintentional or not directed towards the Jewish community, it is serious in its consequences as Jewish fans are hesitant to visit football grounds.Footnote25 In addition, this kind of behaviour and the reproduction of antisemitic rhetoric both on- and offline can lead to the normalization of (symbolic) exclusion of Jews.

In this study, we look at the reproduction of football-related antisemitism specifically on social media. Social media platforms, such as Twitter, make it possible for us to interact with like-minded people, find support and share information, but, on the other hand, it also facilitates anti-social behaviour such as online harassment, cyber-bullying and hate speech.Footnote26 By critically investigating the extent to which online message boards and social media have added a new element to fan racism in sport, Cleland claims that online user experiences of racism, both subtle and overt, mirror the physical world in which racism systemically manifests in societies.Footnote27 Online expressions of hate reflect offline experiences of oppression, disadvantage and prejudice.Footnote28 Khosla et al. argue that with more people sharing content on social media daily, the amount of hate speech is steadily increasing.Footnote29 In order to combat online hate, social networking sites, such as Twitter, have put forth hateful conduct policies to tackle these issues. Twitter has developed their hateful conduct policy in order to combat abuse motivated by hatred, prejudice and intolerance. Users can report misbehaviour, and Twitter may decide to delete Tweets that instigate hate and ban users that have a record of violations (Twitter, sd).

In this study, we view Twitter as a frontstage that people perceive as backstage, following Kilvington’s work on online hate speech.Footnote30 Kilvington uses Goffman’s front- and backstage model in order to understand the factors that motivate online hate speech. He argues that communication via new media, such as Twitter, blurred the boundaries between front- and backstages. Frontstages are traditionally known as a public space where people perform for the ‘public’, where backstages are private spaces in which people express themselves more freely. Goffman’s theory of human interaction and behaviour was exclusively based on the analytic interpretation of face-to-face situations where people are physically present. Goffman’s metaphor of the front- and backstage suggests that people present different versions of themselves through guiding and controlling impressions in public (frontage) and private (backstage) spaces. Kilvington has altered the model in such a way that it is better applicable to the online domain. While social media platforms are overtly frontstage spaces in which people perform for others, the nature of the so-called online disinhibition effect means that it can feel like a backstage environment in which people are more prone to express prejudice.Footnote31 With this online disinhibition effect, Kilvington and Suler mean the lack of restrain people feel when communicating online in comparison to in-person communication.Footnote32 Online disinhibition can be expressed in various online interpersonal behaviours, either positive or negative. It usually means that people experience less behavioural boundaries and inhibitions while in cyberspace. As such, it is argued by Kilvington that all virtual communication, whether posted in a virtual frontstage (Twitter feed) or a virtual backstage (Twitter DM) is created within a space thatgenerates backstage feelings such as privacy and security.Footnote33

Contextualization: football-related antisemitism in the Netherlands and the rivalry between Ajax and Feyenoord

Contemporary football-related antisemitism in the Netherlands is mostly targeted against Ajax. The club’s Jewish image stems from before the Second World War.Footnote34 Due to the stadium’s geographical location in the East of the city – where many Jews lived – the club had a relatively high Jewish supporter base.Footnote35 Today, Ajax does not have a substantial Jewish fan base, but fans, players and others involved with the club are all ‘othered’ as ‘Jewish’ by some of their opponents.

According to Spaaij,Footnote36 the rivalry between Ajax and other Dutch football clubs is central to understanding contemporary antisemitic discourse in Dutch football. Schots explains how Feyenoord-Ajax – or ‘De Klassieker’ – is more than just a football match.Footnote37 It is a battle between the two largest cities of the Netherlands, the capital against a big harbour city. According to Schots, the rivalry between Ajax and Feyenoord stands for a battle between, respectively, working people and the cultural elite and between roughness and sophistication.Footnote38 Both clubs have been one of the most successful in their respective cities since the 1920s, but Ajax and Feyenoord have not always been major rivals. Until approximately the 1960s, they both had more important in-city rivalries.Footnote39 The rivalry and hostility between Ajax and Feyenoord increased during the 1970s. Due to the rise of hooliganism and violence between the two supporter groups, public and official concern over the two rivalling supporter groups grew. This concern also related to antisemitic abuse during matches between the two clubs.Footnote40 After social disorder and confrontation between the two rival fan groups surrounding a game between Ajax and Feyenoord in the Amsterdam Arena in 2009, Rotterdam’s mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb and former mayor of Amsterdam Job Cohen decided that games between the two rivalling teams would be played without support from the away team. This measure applies till date.

Within Dutch football antisemitic rhetoric it is used to signify collective identity and express club rivalry, especially towards Ajax due to the club’s alleged Jewishness. This kind of behaviour is not confined to the most fanatic fans or to people within hooligan subcultures. Many Dutch football supporters find that philosemitic and antisemitic chants and symbols are part of the football experience.Footnote41 Supporters often explain their behaviour by arguing that they do not want to hurt Jewish people, but the football ‘other’.Footnote42 Even though supporters narrate that they are ‘just’ making a reference towards Ajax when using ‘Jew’, antisemitic rhetoric goes beyond the rivalry between Ajax and other clubs. Antisemitic rhetoric has become a part of the vernacular culture of fans. ‘Jew’ or ‘nose’ (a link to the stereotype that Jews supposedly have a big nose) is an expression of rivalry, as well as a swear word or an insult. For example, on social media such as Twitter and Instagram, the hashtag #KNJB, meaning Royal Dutch Jew Organization, is used in order to express displeasure towards the Royal Dutch football Organization (KNVB). The ‘logic’ that being a Jew is offensive stems from a hegemonic discourse of othering regarding ‘Jews’ in the Netherlands (and beyond) which is then used by particular fan groups to express the rivalry between Ajax and other clubs. This is strengthened by some supporter’s perception that Ajax, their rival, is a ‘Jewish’ club.Footnote43

Due to the antagonism between Feyenoord and Ajax, practices and narratives that evolve around performances of rivalries and loyalties become significant. Our study asks how rivalries and loyalties are performed in the online sphere (Twitter) in relation to Ajax supposed ‘Jewishness’. We do not focus on the rivalry between Ajax and Feyenoord as such, but how it is expressed online in relation to antisemitism.

Methods

In this section, we provide information on our methods. Given that we have analysed Twitter messages, we will, first, provide some more details about Twitter and our specific sample, followed by information on our data collection and data analysis.

Twitter is a social-networking and microblogging service. It encourages users to answer the simple question: ‘what’s happening?’ in short Twitter messages of a maximum of 280 characters that are referred to as Tweets. We consider these Tweets as computer mediated discourse or digital discourse meaning communication produced when humans interact with each other via networked and mobile computers or other digital communication devices. Examples are email, chats, blogs and social media such as Twitter.Footnote44 For our study, we selected the weekend in which ‘De Klassieker’ was played to scrape Twitter data to explore rhetoric which fuels (or challenges) antisemitism among Dutch football fans on Twitter. While Ajax – Feyenoord has been played without support from the away team for over ten years, this year fans of the home team have not been welcome either due to the COVID-19 rules in the Netherlands. As no fans were allowed inside the stadiums, we assume that people tweeting about the match were watching it simultaneously on television or online.

We collected data from Twitter using the Twitter API.Footnote45 Twitter’s standard search API returns a collection of Tweets matching a specified query. In our case, we scraped messages that used the following hashtags: #feyenoord, #ajax, #klassieker, #ajafey, #020fey and #aja010 (020 and 010 are the area codes of Amsterdam and Rotterdam) on the 16th or 17th of January 2021, Tweets posted prior, during and after the game. This scrape left us with over 12.000 Tweets, many of which had nothing to do with the football match. In this sense, you can think of Tweets from users or bots that make use of trending hashtags to promote their message or merchandise, but also Tweets about player transfers or a demonstration in Amsterdam in the same weekend. As the aim of this article is to analyse expressions of rivalry of fans in relation to antisemitic and philosemitic discourse, Tweets that had nothing to do with the match were deleted from the dataset. Tweets in languages other than Dutch have been removed as well because it appeared that most of those were not about the actual football rivalry, but also because we used Dutch words such as ‘Jood’ (Jew) or ‘neus’ (nose) during the coding process to select the Tweets that referred to Ajax’s supposed Jewishness. Tweets that combined Dutch with another language – for example, English or German – were kept in the dataset as it is common for Dutch speakers to use English words in their daily talk on football as well as in online communication. After the data was cleaned, the dataset consists of 10,529 Tweets.

Different discourse(s) can be analysed with this dataset, however in this paper we focus on the narratives and expression(s) of rivalry in relation to Ajax supposedly ‘Jewishness’. Therefore, we made a selection of Tweets that made reference to Ajax’s supposed Jewishness. First, we coded the Tweets that made reference towards Ajax supposed ‘Jewishness’ in overt ways by, for example, using words such as ‘Jood’ (Jew) or ‘neus’ (Nose). Secondly, Tweets with a more indirect reference towards the supposed Jewishness of Ajax were coded. These Tweets would not necessarily be recognizable as drawing on the image of Ajax being a ‘Jewish’ club outside of the football context and seemed ‘innocent’ at first sight but had, for example, a video or image attached that referred to Ajax’s supposed ‘Jewishness’. This left us with 111Tweets that made a reference towards Ajax’s perceived Jewishness and these were analysed more in depth. All messages are anonymized in order to safeguard people’s anonymity. Tweets are also translated from Dutch to English, both for readability of the paper but also to ensure that Tweets are not easily traced back towards individual users.

We have used narrative digital discourse analysis to interpret the Tweets. Digital discourse analysis focuses on language and language use and makes use of discourse analyses as a method to analyse digitized messages. Critical discourse analysis assumes that power is transmitted and practiced through discourse. During the analysis, we focus not only on describing the text, but also why and how it is produced and what possible ideological goals the text might serve.Footnote46 Texts and thus Tweets reflect and encode values and ideologies related to the larger world. This means that discourse(s) produced in online and offline settings interact and influence each other. Understanding language and how people communicate is always related to the contextual knowledge of the person analysing language. ‘Intuitive’ interpretations only work when we have knowledge of the context in which the text is produced.Footnote47 Thus, in order to understand the narratives adopted by people who are tweeting about the game between Ajax and Feyenoord, we interpreted the Tweets within the wider context of Dutch football, where Ajax is a supposedly ‘Jewish’ club and within the wider discourse of antisemitism in Dutch society in general and Dutch football in particular. In addition, the first author of this paper also watched the game between Ajax and Feyenoord in order to understand Tweets that potentially expressed dislike with players, the referee etcetera and to put the Tweets in the context of that particular game.

Results: expressing rivalry on twitter

The majority of the Tweets we found were not of antisemitic nature, they consisted of information about players, squads, complained about the performance of players and the referee, praised players, expressed rivalry with the football ‘other’ drawing on different narratives than Ajax’s supposed Jewishness etcetera. A percentage of 1.05 of the Tweets that we found drew on or made a reference towards Ajax’s supposed Jewishness. As said, this means 111 Tweets in absolute numbers including both Tweets that make overt references towards Ajax's perceived Jewishness as well as Tweets with a more indirect reference.

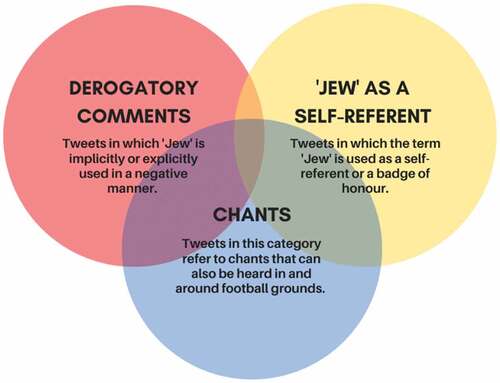

In this section, we will describe the main discourses and terminologies relating to Ajax’s supposed Jewishness that football fans draw on when tweeting about the Ajax-Feyenoord match. As shown in . we grouped the Tweets that referred to a similar phenomenon, resulting in three main themes: 1) derogatory comments, 2) ‘Jew’ as self-referent and 3) chants. Within the first theme, we grouped together all, coded derogatory referencing of Ajax fans, the players or the KNVB as, for example, smouzen or ‘noses’. And Tweets within this category can often be labelled as hate speech. Within the second theme, Jew is used as a self-referent or a badge of honour. Philosemitic Tweets fall within this category. Within the third set of Tweets, Tweeters draw or make a reference towards antisemitic – or philosemitic – chants that can usually also be heard in and around Dutch stadiums. Within this theme we grouped Tweets that consisted (parts) of antisemitic or philosemitic chants or video’s in which such chants we audible. Because chanting is a different form of expressing oneself then using ‘Jew’ as a badge of honour or using ‘Jew’ as an insult, we have made chants a separate theme. Some tweets fit within multiple themes and therefore they partly overlap. For example, a Tweet can both draw on a chant and be considered as coded derogatory referencing. Sixty-four tweets are grouped within the theme ‘derogatory’, 55 tweets within the group ‘chants’ and 24 in the group ‘Jew as self-referent’. After presenting the three overlapping themes we will interpret our findings and place them in a wider societal and academic perspective.

Derogatory comments

The most elementary form of rhetorical discrimination is that of identifying persons or groups of persons linguistically by naming them derogatorily.Footnote48 Terms like the Dutch ‘Jood’ or ‘Smous’ are sufficient to perform racist or ethnicist slurs on their own as they connotatively convey disparaging, insulting meanings without any other attributive qualification. As explained, this ‘logic’ that being a Jew is offensive stems from a hegemonic discourse of othering regarding ‘Jews’ in the Netherlands (and beyond) which is then used by particular fan groups to express the rivalry between Ajax and other clubs. An example of a Tweet in which this elementary form of rhetorical discrimination is expressed is Stink ‘smouzen’. With your shabby team. #ajafey.Footnote49 Smous is an offensive term in Dutch for people of Jewish ethnicity or people that adhere to the Jewish religion. It is mainly used as a swear word. In this Twitter message, the term does not seem to be used to deliberately insult or discriminate against Jews per se. Rather, it is targeted at Ajax and its supporters.

Another example of coded derogatory referencing is the use of ‘nose’ as a referent for Ajax supporters or players, which is common practice among Feyenoord supporters.

It makes me sick. Playing way better than the #Noses and then we forget to score. What a worthless team is 020. #ajafey.Footnote50

The person tweeting, assumably a Feyenoord supporter, links the term ‘nose’ (#Neuzen) to Jew as has been ‘custom’ outside of football for centuries.Footnote51 Other Twitter users make this link with noses, Jewishness and Ajax by using a nose emoji to refer to Ajax. The use of noses is a reference to supposed Jewishness. Nose(s) is commonly used as a ‘synonym’ for Ajaxcied (Ajax players, fans, etc.) and a reference to the stereotype that Jews supposedly have a big nose. This supporter also uses the area code, 020 instead of writing Ajax. The supporter states that 020 is a worthless team. The area code of Amsterdam is often used by Feyenoord supporters when talking about Ajax, as they dislike or even refuse saying the name ‘Ajax’. The Tweet implies that Feyenoord, not 020 or ‘neuzen’, played better but ‘forgot’ to score. The above Tweets are antisemitic in a less obvious way, compared to Tweets that are more overtly antisemitic such as the following:

Grab them by the throats those kk Jews. Come annn!!! #ajafeyFootnote52

This is an example of a Tweet in which ‘Jew’ is used in an overtly negative manner, as a racist or ethnicist slur. In addition, ‘kk’, which stands cancer (in Dutch kanker), is used as an expletive attributive. In Dutch, swearing often involves the use of diseases. Cancer or other diseases are used as a strong expletive or as an adjective or adverb to make the insult ‘stronger’. While people familiar with the context in which this was tweeted, might understand that this Tweeter assumably does not intent to promote violence against actual Jewish people, people unfamiliar with the context will directly recognize or interpret it the tweet as instigating hate and violence towards Jews. According to the guidelines put forth by Twitter, the tweet can also be considered as hate speech. As explained before, Twitter considers content that promotes violence against or directly attacks or threatens other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease as hate speech (Twitter, sd).

It is however not only Ajax who receive antisemitic abuse, the Royal Dutch Football Organization (KNVB) is also targeted. The KNVB is sometimes called Jew association in order to express displeasure towards the organization. After a goal by Jorgensen (a Feyenoord player) was disapproved due to offside a fan outed displeasure towards the KNVB by tweeting: KnJB Jew Association #ajaFEY.Footnote53 In this Tweet, ‘KnJb’ stands for ‘Koninklijke Nederlandse Jodenbond’ (Royal Dutch Jew Association). This is a form of coded derogatory referencing of the football association. As we have explained, the ‘logic’ that being a Jew is offensive is strengthened by some supporter’s perception that Ajax, their rival, is a ‘Jewish’ club.Footnote54 This Tweet also shows how antisemetic rhetoric has become a part of the vernacular culture of fans and has moved beyond the rivarly between Ajax and other clubs. Studies have shown that supporters often explain that they are ‘just’ talking about Ajax, when using the term ‘Jew’ in a football context.Footnote55 This seems, however, not always the case as examplified in the above Tweet.

It is complex to address antisemitic behaviour in Dutch football because fans often use the fact that Ajax supporters call themselves ‘Jews’ as the reason why they use ‘Jew’ in a derogatory manner. In such a situation, supporters of both sides blame the ‘other’ team for the occurrence of antisemitism. Verhoeven and Wagenaar have called this complex situation a ‘vicious circle’.Footnote56 An example of this ‘excuse’ is given in the following Tweet:

Don’t cry about being called ‘Cancer Jews’ if you call yourself ‘Jews’ and the opponent ‘harbour slaves’, ‘spareribs eater’ and “cunt cockroaches.” Grow a pair. #ajafey.Footnote57

Antisemitism, however, can also manifest unintentional and indirect (Arkel, Citation2009). Intentional and unintentional or unconscious forms of antisemitism can be regarded as actions that are exclusionary in their consequences.

In addition, the fan who tweeted the above Tweet also argues that since Ajax supporters call Feyenoord supporters cockroaches or harbour slaves,Footnote58 they should not complain about being called Jews in a derogatory manner. These kinds of references can also be seen as derogatory commenting towards Feyenoord supporters, however, that is not the focus of our study.

‘Jew’ as self-referent

On the other side of the ‘vicious circle’Footnote59 we have Ajax fans who have adopted ‘Jew’ or ‘Super-Jew’ as a badge of honour. Within this theme, Tweets use ‘Jew’ as a self-referent or badge of honour are grouped. As we have explained, both antisemitic rhetoric and philosemitic rhetoric are used to signify collective identity and express club rivalry.

They will never win from the Jews! Never from the Jews! They will never win from the Jews #ajafey.Footnote60

This Tweet is most likely sent by an Ajax fan to cheer on Ajax. In the football context, the phrase ‘they (Feyenoord) will never win from the Jews’ means that Feyenoord will never win from Ajax. This fan uses the term ‘Jew’ as a badge of honour, which can be seen as philosemitic. Within Dutch football, philosemitism should be seen as the mirror of antisemitism. In the collective imaginary of supporters from different Dutch professional football clubs, the term ‘Jew’ is detached from its meaning. When Ajax supporters use ‘Jew’ or ‘Super Jew’ as a self-referent this has little to do with Judaism or Jewish culture.

The following Tweet entails the use of ‘nose’ as self-referent by an Ajax supporter, but not necessarily in a positive manner.

This fan states that Onana – Ajax’s goalkeeper – was the man of the match and that they are very relieved that the game is over. Ajax won the game by 1–0, but especially the last half of the game Feyenoord had many chances to score and Ajax did not play so well. This fan is not using ‘Jew’ as a badge of honour but still draws on Ajax’s image as a ‘Jews’ club by stating to be a relieved ‘nose’. These Ajax fans link the term ‘nose’ to Jew, just like we have seen Feyenoord fans doing. Like fans of other clubs, this fan uses nose as a synonym for Ajaxcied (Ajax players, fans, etc.) and a reference to the stereotype that Jews supposedly have a big nose.

As mentioned previously, Ajax supporters use to carry Israeli flags to the stadium. Among the Tweets, we found about the match we also found Tweets that linked to videos of supporters inside the stadium waving Israeli flags.

Can you hear the #F-side sing #WZAWZDB #Roadto35 #ZWNVDJ #HZMKK #AJAX #AJAfey [link to movie]Footnote62

Also, one of the hashtags in this Tweet, namely #ZWNVDJ, refers to Ajax’s Jewish image. It stands for ‘zewinnen nooit van de Joden’ which translates to ‘they will never win from the Jews’, a slogan we have already discussed.

Another example of philosemitism is the following Tweet:

This is an example of a Tweet that fits within two themes. It is part of an anti-Feyenoord chant sung by Ajax fans inside stadiums, but it also uses the term ‘Jew’ as a badge of honour. In this sense, philosemitism seems related to signifying club identity. An in-group is created while drawing on Ajax’s supposed Jewishness. Ajax supporters use ‘Jew’ or Super-Jew as a self-referent and a badge of honour. Over the years, philosemitism has become an important source of identity for Ajax fans.Footnote64 Within this moral frame of reference, antisemitism and philosemitism are two sides of the same coin. Both function as central themes in defining the boundaries between us and them. After all, we have Feyenoord fans on the other side who create an out-group using similar terminology and rhetoric.

Chants

In stadia, chants play an important role in the formation and reinforcement of the earlier mentioned collective identities. Clark demonstrated the importance of chanting and how fans use chants to establish and reinforce the internal-external dialectic between ‘us’ and ‘them’.Footnote65 Communities of fans use chants to identify who they are, but also who they are not. Their songs and chants express the affiliation and commitment towards a specific team.Footnote66 During the 1970s, supporters of clubs such as Feyenoord sang chants such as ‘Ajax is a Jew’s club’, focussing on the popular image of Ajax being a ‘Jewish’ club.Footnote67 During the 1980s earlier songs and chants were replaced with chants such as ‘Ajax Jews, the first football deaths’, ‘We go Jew hunting’ and ‘Ajax to the gas chamber’. It is also then that the conflict between Palestine and Israel entered Dutch football stadiums as Feyenoord supporters started carrying Palestinian flags and Ajax supporters’ flags of Israel.Footnote68 Feyenoord supporters added certain slogans and banners seen at anti-Israel demonstrations during the 1980s to their repertoire.Footnote69 The now commonly used chant ‘Hamas! Hamas! All Jews to the gas’ was first heard during the mid-1990s at Feyenoord and FC Utrecht stands.Footnote70

Within our set of Tweets, we have found that different football chants that draw on Ajax’s perceived Jewishness find their way from the stadium towards the online domain.

And who does not jump!! #DeKlassieker #Ajax #Amsterdam #WijZijnAjax #JohanCruijffArenaFootnote71

The above message is most likely sent by an Ajax fan, as ‘#WijZijnAjax’ translates to ‘#WeAreAjax’. The supporter references the commonly heard chant: ‘and who does not jump is not a Jew’. Ajax fans sing it in a way that if you do not jump, you are not a ‘Jew’ and as such, you do not belong to the in-group. Feyenoord fans – or supporters from other rival teams – on the other hand, sing: ‘and who does not jump is a Jew’. In this version, you are a ‘Jew’ if you keep standing and as such, you will not belong to the in-group. This chant is another example of antisemitic and philosemetic rhetoric being used to signify collective identity and express club rivalry. The same chant is also shared on Twitter by Feyenoord fans: In the meantime at #Feyenoord … . [link to movie]Footnote72

The above Tweet originally includes a link to a movie in which you can see Feyenoord supporters cheering on their team during the final training before the game between Ajax and Feyenoord is played. In this movie, you see supporters with lots of pyro singing different Feyenoord chants among which is the ‘who does not jump is a Jew’ chant. Traditionally Feyenoord supporters visit the final training before de klassieker is played to cheer on their team. They also did so this year, and the video was made during that gathering and later shared online. The Tweet with the video has been retweeted by both Feyenoord fans praising the action and people condemning it. This fan retweets a video in which you can hear supporters present at the training sing ‘Jews are going to die ole ole’ with the caption: If Pyro would be the indicator … #classic[link to movie].Footnote73 This fan suggests that when support and pyro would determine who would win, Feyenoord would be the winner. Others are less positive about the behaviour displayed by fans, however not because of antisemitic references, but because the gathering was not ‘corona-proof’. A Twitter user seems to suggest that the chanting fans should not receive medical treatment in case they catch Corona: Use GPS to see who does not get an ICU bed .#ajafey[link to movie].Footnote74 This Tweet and other similar reactions to the chants audible in the different videos that were shared suggest that this kind of behaviour and the reproduction of antisemitic rhetoric leads to the normalization of the (symbolic) exclusion of Jews in the Dutch football context.

That Feyenoord is not playing Ajax but the ‘Jews’ in the perception of some tweeters is also exemplified by the use of the #jodfey, a modification of the hashtag #ajafey which is commonly used to reference the game. In the hashtag, jod is short for Joden instead of aja being short for Ajax as you can see in the following Tweet:

The above Twitter message is interesting not only because of the alteration of the hashtag but also because of the reference it makes to an anti-Ajax chant. This layer of meaning is likely not obvious to people unfamiliar with the Dutch football context as ‘Do you also hate that club from … ’ seems relatively innocent and ‘normal’ in the context of a football rivalry. However, this sentence is also the start of a chant which heavily draws on the image of Ajax being a Jewish club. It is an alteration of the chorus of ‘N ons geluk a song by Frans Bauer. Feyenoord fans change the chorus to: ‘Do you also hate that club from Amsterdam? Kick them on their noses, yes as hard as you can because life is short. All Jews to the gas!’ Within the altered chorus the dislike for Ajax is clearly expressed. The club from Amsterdam should be kicked on their noses. The use of noses is a reference to their supposed Jewishness. While the stereotype of the Jewish big nose is centuries old, the association of Jews with gas stems from twentieth century Nazi Germany and was taken over in countries from which Jews were deported to the gas chambers, such as the Netherlands.Footnote76 After the liberation of the Netherlands, ‘they have forgotten to gas you’ immediately emerged as an antisemitic stereotype from the post-Holocaust era in which the Jew is perceived as someone who ‘should be gassed’. The identification of Jews and gas also found its way in (existing) ‘Jewish’ jokes and eventually also into football.

Conclusion

This study shows how football fans draw upon various discourses relating to Ajax’s supposed Jewishness to construct the ‘other’ and express rivalry and self-identification. The relational antagonism between Feyenoord and Ajax is crucial in understanding how the rivalry between the two clubs is expressed, both in online and offline settings. One of the main findings is that antisemitic discourse is pertinent in Dutch football and is expressed similarly in online and offline worlds. While in offline settings such as the stadiums or football bars and café’s chants play a more prominent role in the expression of rivalry, more implicit references towards these chants are also found in online supporter generated content such as Tweets. We have seen that chants and slurs find their way towards the online domain, sometimes explicit and other times implicit. In that sense, online spaces can be seen as a mirror for physical spaces and these Tweets contribute to the normalization and reproduction of football-related antisemitism both in online and offline spaces. These Tweets, while seemingly targeted towards the football other contribute to an exclusionary discourse in which being a ‘Jew’ is not wanted.

As explained, in this study we view Twitter as a frontstage that people perceive as backstage following Kilvington’s work on online hate speech.Footnote77 While social media platforms are overtly frontstage spaces in which people perform for others, the nature of the so-called online disinhibition effect means that it can feel like a backstage environment in which people are more prone to express prejudice.Footnote78 Communication via Twitter – or other new media – has blurred the boundaries between front- and backtags leaving some fans to tweet in a derogatory manner. This can be an explanation for the manifestation of football-related antisemitism in online spaces. Football-related antisemitic behaviour such as certain chants and using the term ‘Jew’ in a derogatory manner that is ‘usually’ only heard in and around football grounds is potentially viewed by everybody who has access to the internet.

We found 111 Tweets that drew on Ajax's perceived Jewishness. We have Tweets that referred to a similar phenomenon, resulting in three main themes. The first theme consists of coded derogatory referencing of Ajax fans or players as, for example, smouzen or ‘noses’. The second set of Tweets Jew was used as a self-referent or ‘badge of honour’. The third group of Tweets draws or makes a reference towards antisemitic – or philosemetic – chants that can be heard inside and around the stadiums. This group consists of Tweets which are parts of (antisemitic) chants, but also tweets that condemn antisemitic chanting. The themes sometimes overlap and as such a tweet can draw on different discourses. For example, a Tweet can both draw on a chant as well as be considered as coded derogatory referencing. We found Twitter messages that are overtly antisemitic as well as messages that made implicit references towards Ajax’s perceived Jewishness. The rules and regulations put forward by Twitter are not enough for detecting and banning less overt forms of football-related antisemitism. While some Tweets might not be understood as drawing on Ajax’s perceived Jewishness for people unfamiliar with the Dutch football context, they should still be perceived as reproducing antisemitic behaviour.

We have also explained how some of the narratives found in football-related antisemitism are linked to antisemitism within wider Dutch society. Fans, for example, link the term ‘nose’ with Jew which also happens outside of the football context. Fans use ‘nose’ and ‘Jew’ interchangeably as a ‘synonym’ for Ajaxcied. Some fans also use the nose emoji in their Tweets. Whereas the stereotype of the Jewish big nose is centuries old, the association of Jews with gas stems from twentieth century Nazi Germany and was taken over in countries from which Jews were deported to the gas chambers, among which is the Netherlands.Footnote79 Soon after liberation of the Netherlands, the slogan ‘they have forgotten to gas you’ emerged as an antisemitic stereotype from the post-Holocaust era in which the Jew is perceived as someone who ‘should be gassed’.Footnote80 This identification of Jews and gas has eventually also found its way into football.

Even though we believe this study on online football-related antisemitic – and philosemitic – rhetoric contributes significantly to understanding the reproduction of football-related antisemitism, further research could involve the scope in which this behaviour is reproduced. As we wanted to gain in-depth insight into the reproduction of antisemitic discourse in online football-related content, we have only looked at Tweets sent in one weekend as a case study. Future studies could extend the scope of the research to gain insight into the extent of the problem of online football-related antisemitism and hate speech in general. In addition, this kind of behaviour is reproduced not only by Feyenoord fans but also by fans of different clubs. Future studies could, for example, make a comparison between (online) antisemitic behaviour among different fan-groups in the Netherlands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Khosla et al., ‘Understanding Community Rivalry on Social Media’.

2. Benkwitz and Molnar, ‘Interpreting and exploring football fan rivalries’.

3. All quotes and chants are translated from Dutch to English by the authors.

4. Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football’.

5. Philosemitism is an interest in appreciation, admiration or respect for Jewish people, Jewish history and culture particularly on the part of the gentile – those who are not Jewish themselves. In Dutch football Ajax supporters call themselves super Jews and, in the past, they carried Israeli flags to the stadium, this behaviour can be seen as philosemitic.

6. CIDI. Monitor antisemitische incidenten 2019; Van Gool and van de Ven, ‘Onderzoek Online antisemitisme Via sociale media’.

7. Van Gool and van de Ven, ‘Onderzoek Online antisemitisme Via sociale media’.

8. In Dutch: Centrum voor informatie en documentatie Israël.

9. CIDI. Monitor antisemitische incidenten 2020.

10. van Dijck and Poell. ‘Understanding Social Media Logic’; Farrington, Hall, Kilvington, and Price, Sport, Racism and Social Media.

11. Khosla et al., ‘Understanding Community Rivalry on Social Media’.

12. Tsesis, Destructive messages.

13. Guiora and Park, ‘Hate Speech on Social Media’.

14. Kick It Out, ‘Kick It Out’s annual reporting summary for the 2019/20 season’; Kilvington and Price, ‘From backstage to frontstage Exploring football and the growing problem of online abuse’.

15. Bennett and Jönsson, ‘Klick it out’.

16. Kick It Out, ‘Kick It Out’s annual reporting summary for the 2019/20 season’.

17. Poulton and Durell, ‘Uses and meanings of “Yid” in English football fandom’.

18. Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football’.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Arkel, The Drawing on the Mark of Cain, 77.

22. Gans, ‘The “Jew” in Football’.

23. Gans, ‘Over gaskamers, joodse nazi’s en neuzen’.

24. Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football’.

25. Ibid.

26. Khosla et al., ‘Understanding Community Rivalry on Social Media’.

27. Cleland, ‘Racism, football fans, and online message boards’.

28. Farrington, Hall, Kilvington, and Price, Sport, Racism and Social Media.

29. Khosla et al., ‘Understanding Community Rivalry on Social Media’.

30. Kilvington, ‘The virtual stages of hate’.

31. Ibid.; Kilvington and Price, ‘From backstage to frontstage’.

32. Kilvington, ‘The virtual stages of hate’; and Suler, ‘The online disinhibition effect’.

33. Kilvington, ‘The virtual stages of hate’.

34. Gans, ‘The “Jew” in Football’.

35. Kuper, Ajax, the Dutch, the War.

36. Spaaij, Understanding football hooliganism.

37. Schots, Feyenoord – Ajax Gezworen vijanden.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.

40. Spaaij, Understanding football hooliganism.

41. Ibid.; Van Wonderen and Wagenaar, Antisemitisme onder jongeren in Nederland Oorzaken en triggerfactoren.

42. Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football: From punishment to education’.

43. Ibid.

44. Herring and Androutsopoulos, ‘Computer-Mediated Discourse 2.0’.

45. API is an acronym for Application Programming Interface. API’s are software intermediaries that allow for different application to talk to each other.

46. Machin and Mayr, How To Do Critical Discourse Analysis.

47. Lucy and Simon, Research Methods for History.

48. Reisigl and Wodak, Discourse and discrimination.

49. Tweet, 17 January 2021.

50. Ibid.

51. Gans, ‘Over gaskamers, joodse nazi’s en neuzen’.

52. Tweet, 17 January 2021.

53. Ibid.

54. Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football’.

55. Van Wonderen and Wagenaar, Antisemitisme onder jongeren in Nederland Oorzaken en triggerfactoren; Seijbel et al., ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football’.

56. Van Wonderen and Wagenaar, Antisemitisme onder jongeren in Nederland Oorzaken en triggerfactoren.

57. Tweet, 16 January 2021.

58. It is not entirely clear why Feyenoord supporters are called cockroaches. Several stories circulate, one of which is that cockroaches are difficult to eradicate just like Feyenoord fans. Feyenoord supporters are sometimes called harbour slaves, because of the idea that many of the club’s supporters work in Rotterdam’s harbour.

59. Van Wonderen and Wagenaar, Antisemitisme onder jongeren in Nederland Oorzaken en triggerfactoren.

60. Tweet, 17 January 2021.

61. Ibid.

62. Ibid.

63. Ibid.

64. Spaaij, Hooligans, Fans en Fanatisme een internationale vergelijking van club – en supoortersculturen.

65. Clark, ‘“I’m Scunthorpe ’til I die”’.

66. Merkel, ‘Milestones in the development of football fandom in Germany’.

67. Spaaij, Understanding football hooliganism.

68. Gans, ‘The “Jew” in Football’; Spaaij, Understanding football hooliganism.

69. Gans, E. ‘Over gaskamers, joodse nazi’s en neuzen’.

70. Ibid.

71. Tweet, 16 January 2021.

72. Ibid.

73. Ibid.

74. Ibid.

75. Tweet, 17 January 2021.

76. Gans, E. ‘Over gaskamers, joodse nazi’s en neuzen’.

77. Kilvington, D. ‘The virtual stages of hate’.

78. Ibid.

79. Gans, E. ‘Over gaskamers, joodse nazi’s en neuzen’.

80. Ibid.

Bibliography

- Arkel, D.V. The Drawing on the Mark of Cain. A Socio-historical Analysis of the Growth of Anti-Jewish Stereotypes. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009.

- Benkwitz, A., and G. Molnar. ‘Interpreting and Exploring Football Fan Rivalries: An Overview’. Soccer and Society 13, no. 4 (2012): 479–494.

- Bennett, H., and A. Jönsson. ‘Klick It Out: Tackling Online Discrimination in Football’. In Sport and Discrimination, ed. D. Kilvington and J. Price, 203–214. London: Routledge, 2017.

- CIDI. Monitor Antisemitische Incidenten 2019. Den Haag: Stichting Centrum Informatie en Documentatie Israel, 2020.

- CIDI. Monitor Antisemitische Incidenten 2020. Den Haag: CIDI, 2021.

- Clark, T. ‘“I’m Scunthorpe ’Til I Die”: Constructing and (Re)negotiating Identity through the Terrace Chant’. Soccer and Society 7, no. 4 (2006): 494–507. doi:10.1080/14660970600905786.

- Cleland, J. ‘Racism, Football Fans, and Online Message Boards: How Social Media Has Added a New Dimension to Racist Discourse in English Football’. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 38, no. 5 (2014): 415–431. doi:10.1177/0193723513499922.

- Farrington, N., L. Hall, D. Kilvington, and J. Price. Sport, Racism and Social Media. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Gans, E. ‘Over Gaskamers, Joodse Nazi’s En Neuzen’. Monitor Racisme and Extremisme, NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies 9 (2010): 129–152.

- Gans, E. ‘The “Jew” in Football: To Kick around or to Embrace’. In The Holocaust, Israel and the ‘Jew’: Histories of Antisemitism in Postwar Dutch Society, ed. R. E. Evelien Gans, 287–314. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

- Guiora, A., and E. Park. ‘Hate Speech on Social Media’. Philosophia 45, no. 3 (2017): 957–971. doi:10.1007/s11406-017-9858-4.

- Herring, S., and J. Androutsopoulos. ‘Computer-Mediated Discourse 2.0’. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, ed. D. Tannen, H. Hamilton, and D. Shiffrin, 127-151. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

- It Out, K. April 24, 2021. ‘English Football Announces Social Media Boycott’. https://www.kickitout.org/News/english-football-announces-social-media-boycott

- It Out, K. 2020. ‘Kick It Out’s Annual Reporting Summary for the 2019/20 Season’.

- Khosla, S., S. Arora, A. Nandy, A. Saxena, and N. Anandhavelu. ‘Understanding Community Rivalry on Social Media: A Case Study of Two Footballing Giants’. Joint Proceedings of the ACM IUI 2019 Workshops. Los Angeles, 2019.

- Kilvington, D., and J. Price. ‘From Backstage to Frontstage: Exploring Football and the Growing Problem of Online Abuse’. In Digital Football Cultures Fandom, Identities and Resistance, ed. S. Lawrence and G. Crawford, 69–85. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Kilvington, D. ‘The Virtual Stages of Hate: Using Goffman’s Work to Conceptualise the Motivations for Online Hate’. Media, Culture and Society 43, no. 2 (2020): 256–272. doi:10.1177/0163443720972318.

- Kuper, S. Ajax, the Dutch, the War: European Football during the Second World War. London: Orion, 2003.

- Lucy, F., and G. Simon. Research Methods for History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. How To Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE, 2012.

- Merkel, U. ‘Milestones in the Development of Football Fandom in Germany: Global Impacts on Local Contests’. Soccer and Society 8, no. 2–3 (2007): 221–239. doi:10.1080/14660970701224426.

- Müller, F., L. van Zoonen, and L. de Roode. ‘Accidental Racists: Experiences and Contradictions of Racism in Local Amsterdam Soccer Fan Culture’. Soccer and Society 2, no. 3 (2007): 335–350. doi:10.1080/14660970701224608.

- Poulton, E., and O. Durell. ‘Uses and Meanings of “Yid” in English Football Fandom: A Case Study of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 51, no. 6 (2016): 715–734. doi:10.1177/1012690214554844.

- Reisigl, M., and R. Wodak. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Antisemitism. London, New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Schots, M. Feyenoord - Ajax Gezworen Vijanden. Utrecht, Amsterdam, Antwerpen: De Arbeiderspers, 2013.

- Seijbel, J., J. van Sterkenburg, G. Oonk, J. Verhoeven, and W. Wagenaar. ‘Antisemitism in Dutch Football: From Punishment to Education’. In Antisemitism in World Football, ed. E. Poulton, London: Routledge, forthcoming.

- Spaaij, R. Understanding Football Hooliganism: A Comparison of Six Western European Football Clubs. Amsterdam: Vossiuspers, 2007.

- Spaaij, R. Hooligans, Fans En Fanatisme Een Internationale Vergelijking van Club- En Supoortersculturen. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008.

- Suler, J. ‘The Online Disinhibition Effect’. Cyber Psychology and Behavior 7, no. 3 (2004): 321–326. doi:10.1089/1094931041291295.

- Tsesis, A. Destructive Messages: How Hate Speech Paves the Way for Harmful Social Movements. New York: NYU Press, 2002.

- Twitter. (n.d.). ‘Hateful Conduct Policy’. https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy (Accessed May, 2021).

- Van Dijck, J., and T. Poell. ‘Understanding Social Media Logic’. Media and Communication 1, no. 1 (2013): 2–14. doi:10.17645/mac.v1i1.70.

- Van Gool, R., and C. van de Ven. ‘Onderzoek Online Antisemitisme via Sociale Media: Elke 83 Seconden’. May 2020. De Groene Amsterdammer. https://www.groene.nl/artikel/via-sociale-media-elke-83-seconden (Accessed March, 2021).

- Van Soldt, W. ‘De Mazzel’ En Andere Zaken: De Verspreiding van de Mesopotamische Cultuur Na 1500 V. Chr. Leiden: Universiteit Leiden, 2004.

- Van Wonderen, R., and W. Wagenaar. Antisemitisme onder Jongeren in Nederland Oorzaken En Triggerfactoren. Utrecht: Verwey-Jonker Instituut, 2015.

- Verhoeven, J., and W. Wagenaar. ‘Appealing to a Common Identity.’ In Discrimination in Football: Antisemitism and Beyond, Brunssen, P., Schüler-Springorum, S., 141-151. London, New York: Routledge , 2021.