?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Switzerland is a small country of just 8.5 million people. It comprises three distinct language regions and is split into 26 cantons, each of which has a large degree of autonomy. These factors produce a splintered market for sport and clubs are based in areas that vary in terms of their local potential (demographic and economic). Furthermore, soccer clubs face intense competition from another highly popular sport – ice hockey. How clubs exploit a very heterogeneous local potential in a specific context? In this paper, we examine the relationship between a club’s local potential (market environment and stadium) and its expertise in the areas of sporting results, management and marketing. Based on our data, we outline the characteristics of the different economic and sporting models adopted by Switzerland first division soccer clubs and we derive a typology of four types of clubs. Our study’s contribution is both methodological and empirical.

Introduction

Switzerland’s elite clubs have to survive within a small domestic market (the country has a population of just 8.5 million people) and even though soccer is very popular in Switzerland, Swiss stadiums attract fewer spectators (mean attendance for 2019 was 11,300, an occupancy rate of 55.8%). Moreover, Swiss football contends with strong competition from Switzerland’s world-class ice hockey league, whose matches attract almost capacity crowds (87.5% stadium occupancy). The situation is complicated further by the fact that Switzerland has three socially and culturally distinct language regions (Germanophone, Francophone and Italophone) and a federal system of government, which means that soccer clubs are subject to different legislations, most notably in terms of taxation, depending on the canton (region) in which they are based. Finally, the Swiss soccer league imposes few regulations on its professional soccer clubs.

The Swiss Football Association has several peculiarities because its elite clubs (Super League) operate in very different demographic and economic environments. For example, FC Zurich’s home canton is almost ten times more populous than Neuchâtel Xamax’s home canton (1.54 million and 179,000 people, respectively) and FC Zurich has a much more favourable economic environment in terms of local businesses, investors and financial markets. Nevertheless, these differences are not always reflected in a club’s performance on the field. Both Neuchâtel Xamax and FC Zurich were relegated to the Challenge League (2016 and 2020, respectively) and FC Zurich won only one of its last four Super League matches against Neuchâtel Xamax (the other three matches were drawn). Thus, the uncertainty of sport enables teams with very different local potentials to coexist and remain competitive. Since 2003, there are ten teams in the Super League, which play each other four times (twice at home, twice away), giving a total of 36 matches per season. Only three teams (FC Basel, BSC Young Boys and FC Zurich) have won the Super League between 2003 and 2021.

Switzerland’s 20 Super League and Challenge League clubs represent just 12 of the country’s 26 cantons. Given the particularities of Switzerland’s soccer market – low income from television rights, intense competition from ice hockey, an already small country with three language areas and which is not part of the European Union – how have soccer clubs adapted their models to their very different local potentials in order to remain competitive both sportingly and economically? How do the clubs exploit their very different local potentials?

The present study examines the relationship between a club’s local potential (market environment and stadium) and its expertise in the areas of sporting results, management and marketing. Analysing data for the 12 clubs that played in the Super League during the last five seasons before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (2015–2019) enabled us to outline the characteristics of the different economic and sporting models adopted by these clubs. We derive a typology of four types of clubs based on their success in exploiting their local potential and on their managerial, sporting and marketing expertise: (i) hegemonic clubs, (ii) flagship clubs, (iii) clubs with an under-exploited potential, and (iv) heterogeneous small local clubs. These four categories reflect the particular environments in which the different clubs operate.

Literature review

The key concept of local potential

Even though several studies have investigated the effects of geographical location on sport, especially in the case of professional teams, the issue of soccer clubs’ local potential has rarely been investigated. Durand examined the impact of demographic factors on two contrasting ways of organizing professional sport: the American model of ‘closed’ leagues, and the European model of ‘open’ leagues.,Footnote1Footnote2 Europe’s soccer clubs have limited scope to increase their local potential because each club is historically and culturally rooted to a specific place. Hence, each club’s main aim is to maximize its sporting results within a budget that may be constrained by the size of its local market. In contrast, North American sports clubs (often referred to as franchises) are less-firmly rooted in a specific location. As a franchise’s primary objective is to maximize its profits, some franchises have made use of this freedom to move to an area with a larger and wealthier population (greater local potential).Footnote3

Durand identified four types of clients for professional clubs.Footnote4 Supporters have traditionally been the main source of revenue for clubs.Footnote5 Although their importance has decreased as revenues from television rights and partner companies have increased, supporters’ financial contributions remain the cornerstone on which professional clubs are built.Footnote6 Indeed, merchandising provides a real opportunity for clubs to monetize their ‘brand’.

Small companies and businesses are the second type of client, as advertising within and through sport has become a traditional tool for promoting companies, which purchase advertising space in and around a stadium.Footnote7 They also buy public relations opportunities and associated services. Sponsorship from national and international brands can be a major source of income for clubs, but powerful local companies are key components in clubs’ economic strategies. Such clients constitute a good regional and, in some cases, national market for clubs.

Local authorities are the third type of client. How much they invest in sport depends on the country, the sport and the level at which a club operates.Footnote8 In North America, strong local-authority support is a major factor in a franchise’s choice of home. This support can cover many key areas, including help building and maintainingfacilities (stadiums, ice rinks, etc.) and providing indirect (tax exemptions, purchase of services, etc.) and direct support. Local authorities see this support as an investment, as the presence of a professional sport club can have substantial social, economic and media impacts.

The media are the fourth source of income for professional clubs.Footnote9 Major broadcasters have become many clubs’ (and some leagues’) most important clients.Although only a small number of clubs and leagues can attract these clients, solidarity systems often ensure less prestigious clubs and leagues also benefit from this source of revenue, albeit to a lesser extent.

Sources of revenue and economic models

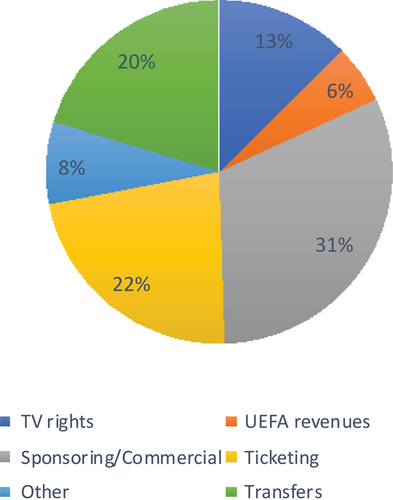

Andreff and Staudohar used a detailed analysis of professional soccer clubs’ financial resources to identify two types of financial model used by clubs.Footnote10 The Spectators-Subsidies-Sponsors-Local (SSSL) model, which predominated from 1960 to 1995, and the Media-Merchandising-Magnates-Market-Global (MMMMG), which arose among clubs which felt that the SSSL model did not provide sufficient profit and which were spending more and therefore needed more resources. The MMMMG only concerns clubs in Europe’s biggest leagues. Clubs in more modest leagues, such asSwitzerland’s Super League, still follow the SSSL.Footnote11 The SSSL model is not however a truly accurate picture of how Swiss clubs function, as they no longer receive direct public subsidies (only indirect subsidies in some case with the help of the construction and functioning for a stadium) and rely on other sources of revenue. shows the sources of Swiss clubs’ revenues. Although these sources are similar to those of clubs in other European leagues,Footnote12 there are a number of disparities, most notably with respect to television rights. Swiss clubs obtain a substantial proportion of their revenues from ‘other’ sources and from ‘patrons’, whose contributions are an extremely important part of many clubs’ finances. The present analysis of Swiss clubs’ economic models takes into account all these sources of revenue, which are examined in the light of each club’s local potential.

Regulation of professional sport

Although the present study focuses on the impact of local potential on clubs’ economic models, the regulations imposed by Switzerland’s soccer authorities also shape these models. Our study falls within the domain of the theory of regulation, a concept Frison-Roche defined as ‘a set of techniques for organizing or maintaining economic balances in sectors that do not have, for the moment or due to their nature, the strength and resources to produce themselves’.Footnote13

By its nature, the professional sport sector is subject to economic unbalances and has therefore become subject to regulation.North America’s professional leagues are all ‘closed’ leagues, with no system for promotion or relegation. Closed leagues must be regulated if they are to operate successfully.Footnote14 Organizing the championship is a league’s main role, but it also regulates the labour market (player transfers, contracts, salary capsFootnote15), and redistributes revenues (box-office receipts and television rights) between franchises.Footnote16 Because it is essential for a league to maintain its championship’s competitive balance, wealthier franchises help support franchises with poorer local potential.Footnote17 The primary objective for both the league and its franchises is to maximize profits, so the league may authorize a franchise to move to another city if it considers the franchise’s current local potential to be too small.Footnote18

The situation in European soccer is very different. Each league sets its own regulations. All of Europe’s leagues are ‘open’, as they incorporate a system of promotion and relegation. Consequently, a club’s financial performance depends on its sporting performance. There are no salary caps, limits on transfers, or regulated redistribution of revenues, whether via charities or to develop football. However, there are differences between countries, and leagues try to impose certain rules on their championships.

Theoretical framework

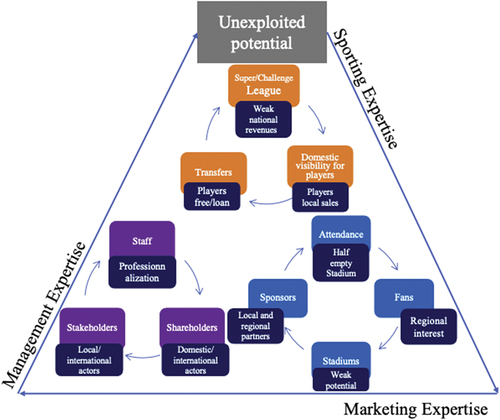

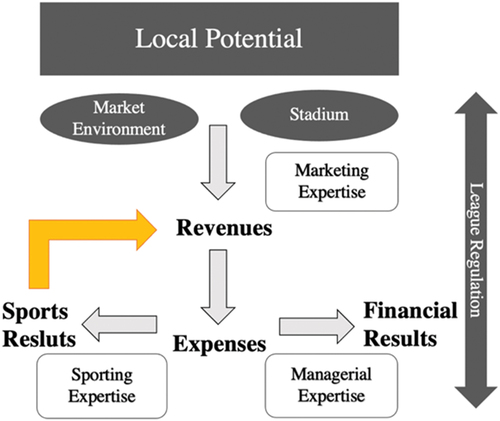

Durand et al.’s () model includes other types of expertise in addition to the different types of client for professional clubs. Analyses of local potential (which depends on the market environment and a club’s stadium) must also take into account the competitive environment, as professional sports clubs face competition from other spectator sports and other leisure activities. Consequently, local markets are split between different sports and different teams within a single sport. Competing in such markets requires three types of expertise:

Figure 2. Local potential/professional clubs’ expertise (adapted from Durand, Ravenel, and Bayle, Citation2005).

Commercial expertise (I) is required to transform local potentialinto revenue, which can then be used for production.

Managerial expertise (II) is required tokeep expenditure within estimated and strategic limits. Doing so will determine a club’s financial results.

Sporting expertise (III) is required to ensure expenditure is productive. Sporting results impact a club’s revenues. Winning matches boosts ticket sales.

The need for these three types of expertise suggests that sporting and/or financial results will not correlate perfectly with local potential and that human expertise can compensate, to a certain extent, for local factors. Although a well-managed club with a powerful commercial network and solid commercial expertise can make up for poor local potential, clubs with similar levels of expertise but based in rich cities are likely to obtain better results.

The SFL regulates Swiss professional football. Most importantly, it sets the legal, infrastructure, sporting, administrative, financial, and safety requirements a club must meet in order to obtain a licence to compete in the championship. These regulations do not place any limits on a club’s expenditure or on players’ salaries. The ten clubs that comprise Switzerland’s Super League are free to choose their own organizational structure and legal form, although the first team must be registered as a limited company. However, the bodies most Swiss clubs set up to manage aspects such as their stadium or events may be given other legal forms. Thus, Swiss clubs enjoy a large degree of organizational and operational freedom. On the other side of the coin, they receive very little support from the SFL. Because the SFL imposes few sporting or economic restrictions on clubs, there is a strong correlation between a club’s budget and its sporting results (15 of the last 17 league titles have gone to the club with the largest budget).

Methodology and data

Our analysis takes into account both exogeneous factors, such as a club's local potential, measured in terms of its market environment and its stadium, and endogenous factors, measured via a club’s marketing, managerial and sporting expertise.

Data

We collected data, primarily for 2019 but also covering the last five years of the Swiss soccer championship, from the SFL, press articles, interviews with experts and other sources. Although each Swiss Super League club is a combination of limited companies (e.g. for its first team), non-profit associations (e.g. for its training centre) and limited liability companies (e.g. for its restaurants and stadium), we considered each club to be a whole. The data collected allowed us to draw up a typology of the 12 clubs that played in the Super League between 2014 and 2019. The Super League contains only ten teams but the promotion/relegation system results in the league’s composition changing every season. Consequently, two predominantly Challenge League teams – Grasshopper CZ and Lausanne-Sport – played in the Super League for two of the five seasons covered by our analysis (2015 to 2019 for Grasshopper CZ and 2015 to 2017 for Lausanne-Sport). Lausanne-Sport again won promotion to the Super League for the 2020–2021 season. Moreover, these two famous Swiss clubs have similar financial resources and infrastructures to the top Super League clubs.

Data processing

We used the data to attribute a performance rating, ranging from 1 (lowest rating) to 5 (highest rating) in increments of 0.1, to each club. We then normalized these ratings by applying the following formula:

Normalizing the results enabled us to compare ratings established on a common basis, to quantify our results and to apply an identical mathematical formula throughout the study. We chose this method, as it is more objective than a purely empirical approach.

Exogenousfactors

Market environment

A club’s market environment depends on its geographical location. This factor is very important in Switzerland, whose cantons enjoy a large degree of autonomy in the fields of politics, health, sport, taxation and education. Consequently, there are substantial differences between the localities that host the Super League’s clubs. We used four measures to assess a club's market environment:

The host conurbation’sFootnote19 population. Zurich, which is home to FC Zurich and Grasshopper CZ, is the largest conurbation; Neuchâtel, Sion and Thunare the smallest conurbations.Footnote20

The host canton’s per capita GDP,Footnote21 which provides a measure of the canton’s economic health and therefore of the population’s ability to consume a club’s products and, most notably, to attend games in the club’s stadium.

The fiscal advantages each canton provides for professional soccer clubs and the amount of tax a Super League player would expect to pay in the host canton.Footnote22

Possible competition for the club within its home canton. For this factor, we considered all professional football and ice hockey (or, in some cases, semi-professional) teams that competed in their sport’s top two divisions in 2019. Not only can other sports capture spectators’ attention, the existence of several top-level teams may lead potential sponsors to choose certain clubs to the detriment of others. Ice hockey is soccer’s main competitor and many cantons have top-level teams. For example, the Bern canton’s two soccer teams, FC Thun and Young Boys, face competition from each other and from four professional ice hockey teams (Langnau, SC Berne, HC Bienne, HC Langenthal). Basel-Stadt is the only canton with no competitors for its Super League club (FC Basel).

Stadiums

We used two indicators to rate the clubs’ stadiums: capacity and degree of ownership. FC Basel (36,000 spectators) and BSC Young Boys (32,000 spectators) have much larger stadiums than the other clubs (mean capacity 19,870 spectators), but these capacities are adapted to each club’s needs, its location and its local situation. In terms of stadium ownership, viewed from a market perspective, it is economically and managerially advantageous for a club to own every aspect of its stadium, as doing so enables it to fully exploit the stadium’s commercial potential. Hence, we measured a club’s stadium ownership by rating three factors: financing, property, operations.Footnote23

BSC Young Boys, FC St. Gallen, FC Thun, FC Luzern and FC Basel own their stadiums. Four of these stadiums break even or are profitable (1 unknown). Owning its stadium allows a club to tap into potentially lucrative sources of revenue, such as staging concerts or letting out space to shops and restaurants. These five clubs’ stadiums are privately owned. FC Servette’s stadium (Geneva)is the only cross-ownership property; all the other stadiums in our sample belong to the club’s host city. Using a publicly owned stadium may not be a disadvantage for a club, especially if it does not pay to use the stadium for home matches, as is the case for Neuchâtel Xamax. However, most clubs that use a local authority financed stadium have to pay rent and do not control the stadium’s other uses. As a result, they are unable to exploit its potential to provide non-sporting revenues. We examined stadium use in the marketing expertise section below.

Local potential

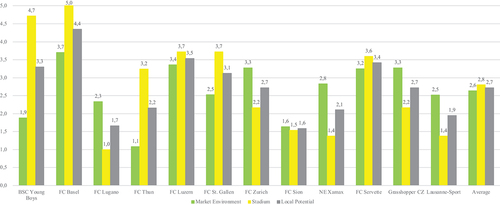

We obtained local potential scores by calculating the mean of the normalized market environment and stadium ratings for each club () . The club with the greatest local potential was FC Basel, which has no direct local competitors, and which has attracted numerous sponsors and investors from among the city’s extensive business community.BSC Young Boys, FC St. Gallen and FC Luzern have good local potential, whereas Sion, Lausanne-Sport and FC Lugano have the poorest local potential as shown in .

Table 1. Exogeneous variables.

Endogenous factors

Managerial expertise

Because a club’s management is of prime importance, we took into account the longevity and stability of each club’s shareholders, the number of shareholders, and the way in which each club is managed and structured. That is, we examined the degree to which a club has professionalized. To this end, for each club (considered as a whole) we counted the number of commercial and administrative staff (equivalent full-time posts) and the number of sporting staff (training, first team). FC Basel had the largest staff; according to the club’s accounts for 2019, it spent half of its turnover on salaries (including players). BSC Young Boys seems to be following the same path as FC Basel, as it has used some of the additional revenues generated by its recent league titles and qualification for European competitions to expand its staff. What is more, these two clubs are strongly rooted in their communities, meaning they have many local board members who are familiar with the life of the club and the area. At the other end of the spectrum lie Neuchâtel Xamax, FCLugano and Lausanne, which have very small structures, employ only a few staff and have a single person at their head. Staffing levels at the other clubs were similar to the mean.

Sporting expertise

We used three indicators of sporting expertise, assessed over the five seasons from 2014 to 2019. The first indicator was sporting performance, measured via a club’s mean position in the league table. Weighting this league position with respect to the club’s budget provided a measure of the club’s sporting efficacy. The second indicator was transfer performance, which we assessed by counting the number of players a club had sold to the Big Five clubs.The third indicator was training performance, measured by counting the number of players who came through the club’s youth training programme to join the first team.

These last two indicators show the prime importance of training forSwiss clubs, from both sporting and economic points of view. Again, the two clubs with the highest sporting expertise scores were FC Basel and BSC Young Boys. FC Basel has a lot of experience in this area and a highly effective training programme that enables the club to bring through young players and sell them to Europe’s biggest leagues. BSC Young Boys also tries to highlight its young talent and to showcase its players in European competitions. FC St. Gallen, FC Zurich and FC Luzern have also made good use of their longevity in the Super League to launch locally trained players. The two clubs at the bottom of the sporting expertise rankings, Neuchâtel Xamax and FC Lugano, are those with the league’s smallest budgets. Both clubs recruit players who are at the end of their contracts or available on free transfers in order to strengthen their squads without spending large sums. Consequently, there is little focus on scouting for or training young players capable of joining the first team.

Marketing expertise

Marketing expertise describes all the actions a club takes to make the best commercial use of its local potential, that is, to raise awareness of the club and keep it alive. For the purposes of our analyses, we divided marketing expertise into three areas: stadium use, social networks and sponsorship. We measured three aspects of stadium use: diversification (i.e. naming, shopping centre, VIP lounge, concerts, conference centre, media centre, exhibitions, restaurant, stadium tours, other), stadium occupancy on match days and mean match attendance for the seasons the club played in the Super League between 2014 and 2019.Footnote24 Because it is not worthwhile for a ‘small’ club with a small local population to have a large stadium (higher cost, more maintenance, etc.), and because the mean occupancy rate for Super League matches is around 52%,Footnote25 it seemed appropriate to take into account mean occupancy rates, as well as match attendance, in order to have a measure of stadium usage with respect to stadium capacity. The second aspect of commercial expertise was a club’s social media presence, which we measured via the number of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram followers each club had on 31 December 2019. Finally, we assessed the number of sponsors each club had and the contribution these sponsors made to each club’s budget for 2019.

With the , results showed () that having a multipurpose stadium with a wide range of facilities and uses was a major advantage. Hence, the clubs in this situation – FC Basel, BSC Young Boys, FC Zurich, Grasshopper CZ, FC St. Gallen, FC Luzern and FC Thun – had a significant advantage over the clubs which had older, less flexible stadiums. In terms of social networks, FC Basel had a substantial lead over the other clubs, largely thanks to its popularity in Switzerland, generated by its long-standing domination of the Super League (11 league titles since 2004) and regular appearances in the Champions League and Europa League. This success has enabled FC Basel to attract several international sponsors. BSC Young Boys also has a few foreign partners, but most of its sponsors are local companies.

Table 2. Endogenous variables.

Summary

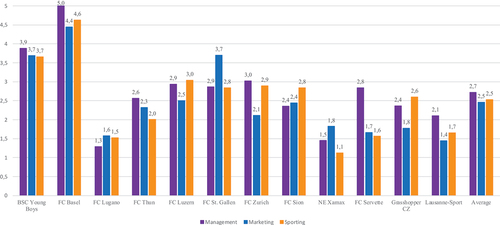

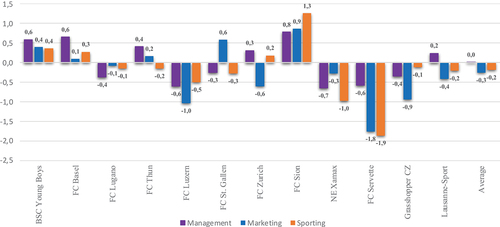

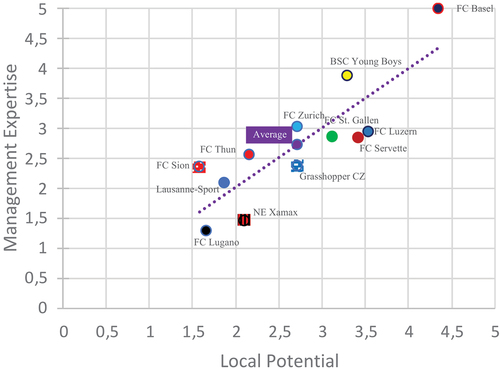

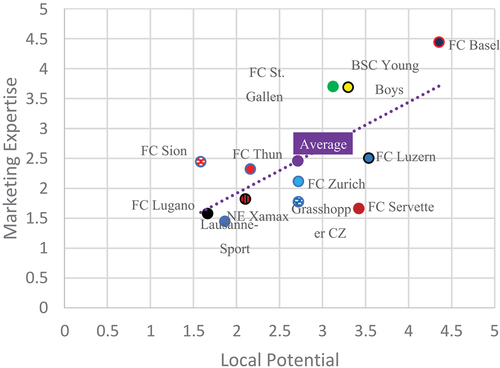

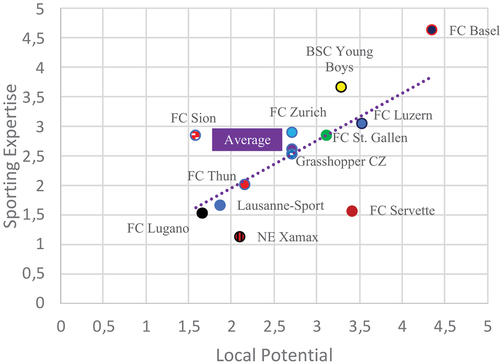

The results described above show major differences in the clubs’ abilities to exploit their local potential and in their expertise (). FC Basel and BSC Young Boys have similar profiles and, alongside FC Sion, exploit every aspect of their local potential. Conversely, FC Lugano and Neuchâtel Xamax have been much less successful in exploiting their local potential. , compare the clubs’ local potential and managerial, sporting and marketing expertise. Clubs above the diagonal line have a level of expertise above their local potential, whereas clubs below the line do not fulfil their local potential.

Results: a typology of super league soccer clubs

The indicators described in the previous section allowed us to divide the clubs into four categories () based on their success in exploiting their local potential and on their managerial, sporting and marketing expertise.

Hegemonics: FC basel, BSC young boys

FC Baseland BSC Young Boys are unarguably Switzerland’s biggest soccer clubs. FC Basel used its domination of the Swiss championship in the early 2000s, (with eight consecutive league titles, 2010–2017) to build both its reputation and a solid sporting and economic structure. BSC Young Boys have followed in Basel’s footsteps, winning the league title for the last four years (2018–2021). The financial and exposure benefits of qualifying for European competitions allowed FC Basel to pull ahead of the field both financially and on the pitch. Unsurprisingly, therefore, it has the highest levels of managerial, sporting and marketing expertise. Although BSC Young Boys has not reached the same level as Basel, it used its runner-up position (the club achieved seven top-three league positions between 2010 and 2017) to build a model (based on FC Basel’s model?) that resulted in the club winning the league between 2018 and 2021 and qualifying forEuropean competitions. Both clubs successfully exploit their very favourable local potential. Their excellent performances in the Super League attract good crowds, resulting in the highest stadium occupancy rates in the league (72% for FC Basel, 65% for BSC Young Boys). These high stadium attendances allow the clubs to exploit related sources of income, such as VIP boxes and catering. Of the two clubs, FC Basel has the greater local potential, as it has few competitors within the canton, it monopolizes the area’s sporting attention, which makes it easier for it to attract general local support. In contrast, BSC Young Boys has to compete for attention.

Both clubs are far ahead of the others in terms of their marketing expertise; which they have used to fully exploit their large, club-owned stadiums, by providing stadium tours, staging concerts and hosting exhibitions. They have also used their high profiles to build large social media followings.

They are the Swiss clubs that sold the most players to Big Five clubs between 2014 and 2019 (12 players for FC Basel, 7 players for BSC Young Boys). In addition to being good ‘salespeople’, they stand out for the quality of their training programmes and for their ability to bring through young players, who are regularly given the opportunities to play for the first team, even though the club is vying to win the Super League.

Over the years, FC Basel has developed a well-defined management structure. The club is rooted in the local community and is run by a combination of local figures and former players. At the beginning of the 2000s, the club’s patron and president, Gisela ‘Gigi’ Oeri, invested heavily in the club, thereby helping to give it a stable structure (thanks largely to its domination in Switzerland and its participation in European competitions) with several shareholders. In 2017, a single shareholder acquired more than 80% of the shares in FCB Holding (which owns the stadium and 75% of the club, but he was replaced as the majority shareholder in 2021 by a former player, who gained control of 91.96% the company’s shares).Footnote26 BSC Young Boys is not far behind Basel. The club and its stadium are owned by its longstanding patrons, the Rihs brothers, via their company Sport und Event Holding AG, but Andy (who died in 2018) and Hans-Uelhi Rihs gradually ‘bequeathed’ the running of the club to the members of its board.

Flagships: FC Luzern, FC St. Gallen, FC Sion, FC Thun

All four clubs are regulars in the Super League. FC Luzern and FC St. Gallen have above-average local potential, while FC Sion and FC Thun are below average. The local competition is much more difficult for FC Thun, which has to face strong sporting competition. Except for FC Sion, which has an old, repeatedly renovated stadium with a capacity of 14,200 and a 63% occupancy rate, all these clubs play in a new, recently built stadium. FC Luzern (17,000 seats and 61% occupancy rate), FC St. Gallen (19,568 seats and 65% occupancy rate), FC Thun (10,000 seats and 59% occupancy rate).

These four clubs are purely local and depend on their regional supporters, who are very present. These clubs are the flagships of an entire canton, or even of a locality like FC Thun. The latter is located in the canton of Bern, where the Young Boys play, but the club is very much rooted in its region of the Oberland, ‘Berner Oberland’, which appears on the club’s crest. The other three teams also have strong local support and few competitors. This allows it to be the leading club in the canton. Of all the clubs, FC St. Gallen has the most commercial partners (279), far ahead of the other clubs.

These clubs are also close in terms of sporting expertise, with FC Luzern, FC St. Gallen and FC Sion tending to integrate their young players into the professional team and succeeding in selling players in Switzerland but also in other leagues. FC Thun has weaker results because it integrates less of its young talent (between 2014 and 2019, 10 against 17 for Luzern, 13 for Sion and 21 for St. Gallen) into the professional team. In terms of transfers, the policy is based on local transfers with a few players leaving for European leagues (Austria, Netherlands, Belgium …) and very few of their players joining the big five. The average ranking of these teams in the Super League has been between 4th and 8th place over the last five seasons.

The marketing expertise is to the advantage of FC St. Gallen (3.7), which makes the best use of its stadium and has the best occupancy rate in the league as well as the most commercial partners. The three other teams are very close, FC Sion (2.4), FC Luzern (2.5), and FC Thun (2.3).

As far as the presidency and governance are concerned, all four clubs can rely on a stable and long-term management. FC Sion has had a president for many years who has remained faithful to the position. The boards of FC St. Gallen, FC Luzern and FC Thun (including a representative of the Chinese Pacific Media Group, a new investor and shareholder of the club in 2019) are composed of local personalities.

Under-exploited potential: FC Servette, Lausanne-Sport, FC Zurich, Grasshopper Club

In their recent history, sporting instability has reigned for these teams. They have all been in the Challenge League (2nd division) before moving up to the Super League – in 2019 for Servette, in 2020 for Lausanne-Sport, a relegation in 2019 and a promotion in 2021 for Grasshopper and a relegation in 2016 and a rise in 2017 for FC Zurich. In their recent history, Lausanne-Sport were bought by English investor Ineos in 2017, the 1890 Foundation (led by the Rolex Group) took over FC Servette in 2015 and Grasshoppers are being bought by a Chinese conglomerate in 2020.

Their local potential is relatively similar, but they differ in a few respects. Firstly, these teams play in a locality with a very high potential, as the agglomerations of these large cities are among the most populated in Switzerland. Zurich leads the way with almost 1.38 million inhabitants, Geneva with almost 600,000 and Lausanne with almost 425,000. These large cities are made up of numerous sports teams, which means that each of these four clubs has to face increased competition on its own soil. Lausanne-Sport has two notable competitors (HC Lausanne, Stade Lausane-Ouchy), while the Zurich clubs face strong competition from hockey (HC Winterthur and Zurich Lions) as well as being direct competitors. FC Servette has only one competitor (HC Genève Servette) and plays in a stadium with a capacity of 30,000 spectators (occupancy rate of 24%). Lausanne-Sport, which inaugurated its new 12,000-seat La Tuilière stadium, hopes to increase from 35%to 50%. As for the Zurich clubs, they play in the same stadium (23,605 seats) with different occupancy rates, 26% for the Grasshoppers and 41% for FC Zurich.

In the sporting expertise Zurich clubs are much more consistent. FC Zurich has integrated 22 players from its academy, compared with 18 for Grasshoppers, 14 for Servette and 11 for Lausanne-Sport. Although their figures are lower, training is an important element for the clubs from Lake Geneva, which both have the label awarded by the Swiss Football Association. In terms of the sale of players in the big five (2014–2019), FC Zurich sold 3 players compared to 5 for Grasshopper Club.

The marketing expertise also reflects the fact that these clubs are lagging behind other Swiss clubs in this area, particularly with regard to their stadiums, which is one of the main tools of the professional clubs’ business model. The fact that the latter belong to the cities concerned does not allow this club to fully exploit this tool for additional activities and to draw the benefits from it (concerts, exhibition …).

In terms of administrative management, Lausanne has a very small structure with about ten employees (excluding sportsmen). The club is in transition, following its takeover, but also following its rise to the Super League. FC Servetteis already established in the Super League and already has a professional managerial base in terms of sport, but also within its management with the Foundation 1890. The number of employees (sport section included) is relatively similar, with FC Zurich having the most (92), followed by Grasshoppers (74), FC Servette (72) and Lausanne-Sport (46).

Although these clubs have a favourable economic national base with an advantageous geographical location and population, they fail to exploit their local potential. Comparing the expertise to their local potential, FC Zurich and Lausanne-Sport have positive results in terms of management and marketing, but negative results in terms of sport. FC Servette and Grasshopper Club Zurich scored negatively on all three assessments compared to their potential.

Heterogenous small local clubs: Neuchâtel Xamax, FC Lugano

Neuchâtel Xamax and FC Lugano have the least favourable local potential. Neuchâtel Xamax is slightly better situated than FC Lugano, which has several local competitors (HC Lugano,FC Chiasso, etc.) and an old stadium with limited capacity (6,390 spectators, 59% occupancy). Neuchâtel Xamax’s stadium is new and larger (12,000, 52% occupancy), but it is owned by the city, so the club only obtains revenue from the stadium on match days.

The two clubs are similar in terms of the three types of expertise. Neuchâtel Xamax has the weakest sporting expertise and its frequent descents into the second division have created a high degree of sporting and economic instability. This makes it difficult for the club to build up expertise in training and transferring players. FC Lugano also has a low level of sporting expertise. The club has been in the Super League only since 2015 and lacks the experience to compete with the league’s longer-standing clubs. However, it achieved a very creditable third place finish in 2019 and therefore qualified for the Europa League, which brought in valuable additional revenues. In fact, these two clubs have the smallest budgets in the Super League and rely on financial support from their respective presidents: ‘in Switzerland, a[club] president must be able to put in 4 million a year from his own pocket’.Footnote27

Neuchâtel Xamax achieved a higher marketing expertise score than FC Lugano, largely because it has a new stadium (FC Lugano is planning to build a new stadium) and this highlights the fact that Xamax is the canton’s only professional first division club (in any sport), which is not the case for FC Lugano, and thereby enables Xamax to make better use of its local potential. Neither club has a high profile outside its surrounding area, so they are unable to attract outside support.

The two clubs obtained very similar management expertise scores. In both cases, it is the club’s owner who ensures the club’s sporting and financial ‘survival’ amongst the elite. Both clubs are owned by one person and have far fewer employees than the other Super League clubs, with smaller squads and only a dozen administrative staff.These two clubs can also be placed in another category. Indeed, we can also consider Neuchâtel Xamax as a flagship club and FC Lugano as a club that does not fully exploit its potential.

Discussion

In this section we discuss the local potential and business models of Swiss clubs according to their typology and their expertise with a model. At the same time, we consider the league regulation and its effects. We will then conclude with the limits and perspectives of our study.

Local potential and changes to the clubs’ economic models

All clubs try to exploit their local potential in order to remain competitive, as a major asset, a multifunctional stadium that also integrates urban facilities.It is also difficult to imagine any development of the revenues from TV rights. Indeed, the geographical and cultural layout of Switzerland forces TV channels to have three studios in three languages (tree times mor costs). These low revenues increase the importance of ticketing, sponsorship and transfer revenues, which allow clubs to make up the deficit (not to mention the help of patronage).

However, building new stadiums and diversifying their offers could enable some clubs to develop new sources of revenue from marketing and sponsorship (if they own their stadium). They could also focus more on transfers and adopt a model centred round buying and selling players. A club’s performances in the Super League provide an initial idea of its earnings, although the biggest step up in terms of increasing revenues is to qualify for European competitions. For example, playing in European competitions, especially the Champions League, has enabled BSC Young Boys to increase its budget fromCHF40 million to almost CHF80 million. Clubs who remain in the Super League every season without achieving a European qualifying place tend to have very stable budgets. In contrast, relegation to theChallenge League can greatly reduce a club’s budget. This was the case for Grasshopper CZ, whose budget fell from CHF22 million to CHF14 million following the club’s relegation in 2018.Footnote28

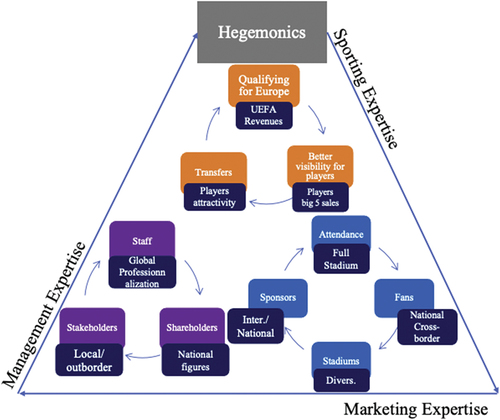

The hegemonics cycle

The hegemonic clubs succeeded on a sporting level. Their results have enabled them to establish themselves permanently in the Super League, but above all to participate in European competitions. This has a direct positive impact on their finances and it helped to put the spotlight on their players to sell them later on.At the same time, it allows them to fill their stadiums, to reach a larger number of fans (outside their canton), while having built, beforehand, their own stadium which allows them to make other extra-sporting profits.On a managerial level, it also creates a buzz and different local figures are interested in the club. As a result, the shareholders have diversified, the investment has increased, and the employee base has broadened. Coupled with this, are a large demographic base and a thriving economy, which help to keep the circle going as shown in .

Flagships cycle

Although the flagships can count on a whole region to support them, they are unable to reach a sporting milestone. Indeed, they can only count on the local championship and the results in the cup. This is a far cry from the income or visibility that European cups can generate. With local visibility, the stadium is not fully filled, the fans are only domestic, and the stadium is not fully exploited.At the same time, as the interest is local, the shareholders and stakeholders are only in the region. Longevity at the highest level allows these clubs to have a professional staff ().

The unexploited potential cycle

Although these clubs enjoy a densely populated region and a prosperous economic base, it is undeniably their sporting results that penalize them in various ways. The rise and fall between the Super League and the Challenge does not allow them to find stability in both sporting and economic terms.The visibility of their players is reduced on a local level, the winds are lower and the purchases very irregular due to the lack of income in particular. Their stadium, which they do not own, is half empty. Sponsors and fans are local and adapt to their team’s results. At the same time, they have very strong competition with the hockey clubs in the region.

However, these clubs are located in strategic regions (Zurich and Geneva being considered, along with Basel, as the three peaks of the Swiss economy) which do not escape foreign investors who see an opportunity through these clubs.Because of their history and past success, they still have legitimacy with local actors, shareholders, and stakeholders ().

Small heterogenous cycle

These small clubs, because of their structure and budget, also had very different sporting results. As a result, revenues are very low and activity on the transfer market is very limited.The stadium does not belong to them and with so few spectators it is difficult to develop extra sporting activities. Their lower budget forces them to find new sponsors and attract more fans who are only local.On the managerial level, the sole owner is content to exchange with local actors and the lack of means does not allow the clubs to expand its staff ().

Towards greater regulation from Swiss soccer’s governing bodies?

Swiss soccer’s governing bodies are aware that producing a more balanced championship would prevent a single club dominating the league (as FC Basel did for over a decade) and reduce the likelihood of other clubs facing financial difficulties. One way of achieving this goal is to regulate the championship more tightly. In England, for example, the third and fourth divisions (League One and League Two) recently introduceda North American style salary cap, partly in response to the difficulties caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.29 A salary cap could create a more-level playing field for Swiss clubs by enabling financially weaker clubs to keep their best players, rather than selling them to the league’s best teams. This would allow clubs to adopt a longer-term perspective and improve the quality of their teams. Currently, FC Basel and BSC Young Boys use their economic strength to attract the best Swiss players, thereby strengthening their squads at the expense of their competitors.

The Super League could also decide to share television rights equitably between all ten clubs, rather than apportioning 50% of these rights according to a club’s league position. This measure would help close the gap between the budgets of Switzerland’s largest clubs, for whom the country’s relatively modest television rights represent a small proportion of their income, and the smaller clubs, which are much more reliant on television rights

Although these two measures could, on paper, reduce imbalances within the league, there is no guarantee they would have the desired impact. For example, there is no guarantee that improving the smaller clubs’ economic health will result in them performing better on the pitch.Swiss clubs are already struggling to compete against Europe’s top teams and their recent poor results have led UEFA to relegate Switzerland from 12th place (in 2018) to 17th place (in 2019) in its rankings. Reducing the number of teams (previously 5) that can potentially qualify for the European cups (to 4 now).

The question of the championship formula also deserves to be discussed. Although we are analysing 12 clubs, the Super League has only 10 clubs per season. As a result, clubs with strong local potential, such as the two Zurich clubs, have been relegated in recent years. Or this season (2021) FC Thun and Neuchâtel Xamax find themselves in the second division, with stadiums and facilities worthy of Super League clubs.The fact that these clubs are not in the Super League raises the question of whether clubs with a much better infrastructure and local potential than second division clubs should not have more room in the Super League.

Limitations and perspectives

The present study has several limitations, most notably due to the difficulty of obtaining accurate financial data on numerous points. Although the clubs publish financial reports, or even accounts, they do not always provide precise and detailed information. Moreover, owners seldom declare how much financial support they give to their clubs and the groups that own many of Switzerland’s professional soccer clubs rarely publish full accounts. It is also difficult to compare clubs, as most split the various aspects of their operations (stadium, first team, training programme) into separate companies. Similarly, it is difficult to obtain details either of the financial packages clubs put together to build or renovate their stadiums or of the deals and contracts they sign with various agencies and sub-contractors (creation of property companies, organization of events, co-ownership agreements, purchase of the stadium).

Social responsibility is becoming an ever-more important part of professional sport clubs’ activities. As such, it would be interesting for future studies to include this fourth type of expertise in order to determine its impacts (social, economic, environmental) on the local community and under the criteria of legitimacy.

In addition, with the arrival of the COVID-19, clubs have been heavily impacted financially. This study does not take this into account, but it would be interesting to understand the effects more precisely and over the long term.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Durand et al., ‘The strategic and political consequences of using demographic criteria for the organization of European leagues’.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Quirk and Fort, Pay dirt.

5. Andreff and Staudohar, ‘The Evolving European Model of Professional Sports Finance’.

6. Copeland et al., ‘Understanding the Sport Sponsorship Process from a Corporate Perspective’.

7. Durand and Bayle, ‘Public Assistance in Spectator Sport’.

8. See note 4 above.

9. See note 5 above.

10. Andreff, ‘Le modèle économique du football européen’.

11. UEFA, The European Club Footballing Landscape, Club Licencing Benchmarking Report, Financial Year 2018.

12. Frison-Roche, ‘La victoire du citoyen-client’.

13. See note 9 above.

14. Hunt and Lewis, ‘Dominance, recontracting, and the reserve clause’.

15. Kesenne and Szymanski, ‘Competitive Balance and Gate Revenue Sharing in Team Sports’.

16. Quirk and Fort, Pay dirt; Szymanski, ‘The Economic Design of Sporting Contests’.

17. In 1960 Minneapolis Lakers moved to Los Angeles to become Los Angeles Lakers.

18. The Federal Office of Statistics defines a conurbation as a group of municipalities with a total population of more than 20,000 people. Most conurbations consist of a central core and an outer ring, whose extent is defined according to the density of commuter flows.

19. Federal Office of Statistics: Permanent and non-permanent resident population according to nationality, gender and canton.

20. Because the canton of Bern, home toFC Thun and Young Boys, is divided into several regions, we considered the per capita GDP of Bern centre (Young Boys) and Thun separately.

21. We determined which of the cantons was the most fiscally advantageous for soccer players by comparing the amount of tax a player (single, no children) who earned the mean wage for a Super League player (CHF170,000 per annum, exc. bonuses) would pay in each canton.

22. Legend: Public; Mixed; Private.

23. Because some of clubs were promoted/relegated from one season to the next, we extended our measures of stadium occupancy/match attendance over five seasons in order to have data for all 12 clubs.

24. Rate for teams that played in the Super League from 2014 to 2019.

25. RTS.ch, 12 May 2021, Super League: David Degen devient propriétaire du FC Basel, https://www.rts.ch/sport/football/12191658-super-league-david-degen-devient-proprietaire-du-fc-bale.html (accessed May 2021).

26. Nemeth, Sedrik, L’Illustré.ch, 29.04.2021. Christian Constantin: ‘Je pense que je vais en prendre pour dix ans’, visited May 2021.

27. GCZ.CH, 6 June 2019, Grasshopper Club Zurich in fresh alignment, https://www.gcz.ch/en/news/news/article/grasshopper-club-zurich-in-fresh-alignment/ (accessed June 2019).

28. The Professional Footballers’ Association contested the caps as being ‘unlawful and unenforceable.’ In February 2021, an independent arbitration panel required the leagues to withdraw the caps.

Bibliography

- Andreff, W, ‘New Perspectives in Sports Economics: A European View’. International Association of Sports Economists, Working Papers (2006).

- Andreff, W., ‘Équilibre compétitif et contrainte budgétaire dans une ligue de sport professionnel’. Revue économique 60, no. 3 (2009): 591–633. doi:10.3917/reco.603.0591.

- Andreff, W., ‘Le modèle économique du football européen’. Pôle Sud (2017): 41-59.

- Andreff, W., and N. Scelles, ‘Le modèle économique d’un club professionnel de football en France’, in Marketing du Football, ed. N.C.E.M. Desbordes. (Economica, 2015), pp. 84-100.

- Andreff, W., and P. Staudohar, ‘The Evolving European Model of Professional Sports Finance’. Journal of Sports Economics 1, no. 3 (2000): 257–276. doi:10.1177/152700250000100304.

- Bayle, E., M. Lang, and O. Moret, ‘How Professional Sports Clubs Exploit a Heterogeneous Local Potential: The Case of Swiss Professional Ice Hockey’. Sport in Society 23, no. 5 (2019): 810–831. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1571044.

- Copeland, R., W.M. Frisby, and R. McCarville, ‘Understanding the Sport Sponsorship Process from a Corporate Perspective’. Journal of Sport Management 10, no. 1 (1996): 32–48. doi:10.1123/jsm.10.1.32.

- Dermit-Richard, N., ‘Football Professionnel En Europe: Un Modèle Original de Régulation Financière Sectorielle’. Management & Avenir 57, no. 7 (2012): 79–95. doi:10.3917/mav.057.0079.

- Dietl, H., R. Fort, and M. Lang, ‘International Sports League Comparisons’. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Management, edited by L. Robinson, P. Chelladurai, G. Bodet, and P. Downward, 388–404. New York, NY: Routledge. (2011).

- Durand, C., and E. Bayle, ‘Public Assistance in Spectator Sport: A Comparison between Europe and the United States’. European Journal of Sport Science 2, no. 2 (2002): 1–19. doi:10.1080/17461390200072206.

- Durand, C., L. Ravenel, and E. Bayle, ‘The Strategic and Political Consequences of Using Demographic Criteria for the Organization of European Leagues’. European Journal of SPORT Science - EUR J SPORT SCI 5, no. 4 (2005): 167–180. doi:10.1080/17461390500344321.

- Frison-Roche, M.-A., ‘La Victoire Du Citoyen-Client’. Sociétal 30 (2000): 49–54.

- Garcia-del-Barrio, P., and S. Szymanski, ‘Goal! Profit Maximization versus Win Maximization in Soccer’. Review of Industrial Organization 34, no. 1 (2009): 45–68. doi:10.1007/s11151-009-9203-6.

- Hassan, D., and S. Hamil, ‘Models of Football Governance and Management in International Sport’. Soccer & Society 11, no. 4 (2010): 343–353. doi:10.1080/14660971003780115.

- Hautbois, C., and C. Durand, ‘Host Territories of Professional Football Clubs. How to Reconcile, for Public Managers, Sporting Brand and Territorial Brand? Les Territoires Et Leurs Clubs Sportifs Professionnels: Comment Concilier, Pour le Décideur Public, Marque Sportive Et Marque Territoriale ?’. Politiques et Management public 32, no. 4 (2016): 347-366.

- Hunt, J.W., and K.A. Lewis, ‘Dominance, Recontracting, and the Reserve Clause: Major League Baseball’. The American Economic Review 66, no. 5 (1976): 936–43.

- Kesenne, S., ‘Revenue Sharing and Competitive Balance in Professional Team Sports’. Journal of Sports Economics 1, no. 1 (2000): 56–65. doi:10.1177/152700250000100105.

- Kesenne, S., and S. Szymanski, ‘Competitive Balance and Gate Revenue Sharing in Team Sports’. Journal of Industrial Economics 52, no. 1 (2004):165-177.

- Quin, G., P. Vonnard, and B. Jerome, ‘Le Football Suisse’. Des Pionniers Aux Professionnels (2016), 129p.

- Quirk, J.P., and R.D. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1992).

- Szymanski, S., ‘The Economic Design of Sporting Contests’. Journal of Economic Literature 41, no. 4 (2003): 1137–1187. doi:10.1257/jel.41.4.1137.

- Vrooman, J., ‘A General Theory of Professional Sports Leagues’. Southern Economic Journal 61, no. 4 (1995): 971. doi:10.2307/1060735.

- Vrooman, J., ‘The Economics of American Sports Leagues’. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 47, no. 4 (2000): 364–398. doi:10.1111/1467-9485.00169.