ABSTRACT

Early termination of football careers is a challenge for elite women footballers. They quit their careers before experience, competence, and performance are fully developed, and women’s football is deprived of the opportunity to develop to the highest optimal quality. Women’s elite football is mostly semi-professional, with athletes juggling between football, work, and education. This qualitative study was conducted through semi-structured interviews with Norwegian elite women footballers (N = 7). Findings suggest the main reason for early termination is the heavy workload due to the combination of studies, work, and elite-level football, which led to exhaustion and burnout. It indicates that providing enough time to recover, fewer “to-dos” pushed into the day, and sufficient resources, hinder the harmful effects of a heavy total workload. The aim of the article is to highlight the reasons for the early termination of football careers for elite women footballers in Norway and the challenges of reaching international standards.

Introduction

Early termination of football careers among elite women footballers is one of the significant challenges for elite women’s football in Norway. Both leagues, the Top Series, and 1st Division consist of young players, with an average age of 22 years old, with only 26% of approximately 450 players being 25 years or older. The young players lack the experience and skills to perform and manage the demands at an international level in elite football, and some experience exhaustion and burnout at an early age due to the total burden in their everyday lives. The study aims to provide valuable insight into reasons for early termination of the football career among women footballers through the experiences of seven former elite women footballers who quit the sport before the age of 30, with the youngest at 22. The three themes, health-related, organizational, and cultural issues were investigated through the interviews and are the main perspectives for the study. The study brings knowledge about the hard conditions the players experienced in their everyday lives and the consequences it had. The results show that the main reason for early termination is the heavy burden of combining studies, work, and elite-level football, which led to exhaustion, poor nutrition, and inadequate sleep due to time pressure and resulted in impaired quality of life.

The research question in this study is why elite women footballers terminate their football careers early; what underlies their decision? The study is based on former footballers’ experiences as elite players in Norway. In Norway, women’s elite football is defined as the two top levels in the national series.

Football as a full-time job – a project beyond reach? The everyday life of elite women footballers

“Without dreams, without ambition – without projects, no one can make anything out of life”. (Simone de Beauvoir, Citation2000)

From its beginning in the early 20th century, women’s football has been neglected, underestimated, and at times banned. Up till today, women’s football has had a low status compared to men’s football among sponsors, media, supporters, and people in general. They still have low status, despite the enormous development that has taken place in women’s elite football worldwide these last years. Most of the leagues and clubs are semi-professional, with few of the players employed full-time. Most of the footballers at the elite level have professional contracts, but not as full-time employees. A combination of jobs, studies, and elite football makes their everyday life demanding. The requirements for being at the international elite level are high, and the available resources do not facilitate reaching their goals. The requirements for being at the international elite level are high, and the available resources do not facilitate reaching their goals. Many players end their football careers in their twenties when experience, competence, and football performance are still in development.

Women footballers have a strong dedication to their sport. They spend time, commitment, and great effort to achieve their goals, sacrificing much else in their lives to play football.Footnote1 The international reports from Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA),Footnote2 Union of European Football Associations (UEFA),Footnote3 and Fédération Internationale des Associations de Footballeurs Professionnels (FIFPro),Footnote4 tell us about grand ambitions for high achievements and dreams of a football career that can last over time and into full-time professional footballers. They have dreams, ambitions, and “a project of great dedication”Footnote5 despite their everyday struggles and efforts to achieve them. These international reports also describe the difficult conditions for women footballers at the elite level and the consequences of the tough everyday load. The Norwegian Football Association (NFF) and the interest organization for elite women’s football in Norway (TFK) have high ambitions and goals for elite football for women in Norway, but the framework conditions which women’s football must operate within may not be satisfactory enough to reach those goals. “While the growth of football is driven by external opportunities and strategic decisions of the industry unless the players have the opportunity to perform to their full potential, progress will be hindered”.Footnote6

Worldwide, the elite clubs in women`s football consist of young players, where some girls at the age of 15–16 make their debut in elite football.Footnote7 At 22, they are already considered veterans with 6–7 years of comprehensive football experience and are often the oldest on the team. Globally, this is a significant challenge for women’s elite football and the development of high-quality football skills. According to FIFAs’ benchmark report on women`s football from 2021, the average age rate in the women`s elite leagues all over the world is low. The average age in the first team was approximately 23 years in 2021, with the US at the top with 26 years and New Zealand and Nigeria with the lowest average age at 19 years.Footnote8 Similarly, the European ranking list over international football teams, also considers the average age to be low.Footnote9 In Norway, the average age of elite women footballers was 21.7 years in 2019, while today, it is 22.7 years.

Burnout is defined as “A prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job and is defined by the three dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment”.Footnote10 Freudenberger, another well-known researcher in the field defined the psychological syndrome burnout as “a state of fatigue or frustration brought about by devotion to a cause, way of life, or relationship that failed to produce the expected reward”.Footnote11 In their research, independently from each other, Freudenberger and Maslach found emotional and interpersonal stressors as indicators of burnout, where the feeling of exhaustion and fatigue were clear signs. Exhaustion is considered the most prevalent of the three aspects.Footnote12 The definition is frequently used within sports psychologyFootnote13 due to the coincidence of burnout among elite athletes. Burnout among sports athletes and coaches has had an increased interest among researchers since the 80s.Footnote14 The key symptoms in sport psychology research have included emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.Footnote15

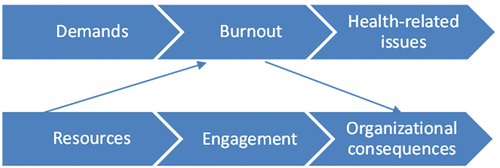

In 1986, Ronald Smith developed a cognitive-affective model of athletic burnout, showing the consequences of burnout as “decreasing performance, interpersonal difficulties, and withdrawal from activity”.Footnote16 The model describes burnout as an overload of high or conflicting demands, low social support, low autonomy, and low rewards. Chronic stress is a central factor in developing burnout,Footnote17 and stress is a natural consequence for elite women footballers who experience an overload in their daily life. Christina Maslach and Michael LeiterFootnote18 developed a Job-Demand-Resource model (JD-R) and a measure (the Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI) with six domains of environmental stressors: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values, where workload, reward, and fairness are the most relevant domains for this study. The JD-R- model is widely used to analyse working conditions in organizations and employees and is a model developed for interaction between services and professions.Footnote19 The study’s respondents corroborate that both models involve elements such as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal success.

The research within job-related contexts is comparable to elite sports where the athletes put a great effort and much time into training and competitions. Some elite athletes have their sport as a full-time job with restitution and rest as part of it, but women footballers face challenging demands to perform at the highest level without facilitation to meet the requirements in elite football. It may result in decreased performance and interpersonal difficulties as consequences. The overload of stressors and demands is not sustainable over time.Footnote20 Being exhausted negatively affects how much and well athletes can perform, and being in this state may affect their development, motivation, and interpersonal relationships. The only way to improve their daily life was to quit their sports. The low average age in elite women’s football indicates that many footballers have had to withdraw from the situation that burned them out or was about to do so – a “healthy worker effect”.Footnote21

The expectations and demands of elite footballers and an elite league do not coincide with the framework conditions the women footballers and their clubs have at their disposal.Footnote22 This, along with the long and extensive battle for the facilitation of women footballers for clubs and interest organizations as long as women’s football has existed,Footnote23 indicates that women’s football has not been considered a serious sport.Footnote24 This has a direct negative impact on the allocation of resources and facilities and such attitudes may also negatively impact the players’ emotional state and interpersonal relationships and influence the women footballers’ mental health. Recently the Norwegian broadcast (NRK) did a survey that showed a considerable difference in funding allocation between young football talents, girls, and boys.Footnote25 Even though the league’s strengths in Norway are talent development, there is a lack of equality with significant consequences for girls’ development as football players. It sets the tone for their opportunities for an elite-level football career, and the differences continue into elite football. Multiple stress-related factors, such as lower resources and a poorer economy, may have a negative effect and can contribute to burnout.Footnote26 The lack of respect, facilitation, and the lack of being taken seriously as football players are a strain that women footballers must endure.

Football is male-dominated, on and off the pitch, and has been so since the beginning of modern football in England in the mid-19th century. Women’s football has never been recognized, and culture, attitudes, prejudice, and values from a male-dominated sport have made it a longitudinal work to be so. Still, today this is a battle for women’s football, even if there is enormous growth and positive development.Footnote27 Increased demands for quality and high performance are not in line with the conditions that football players must relate to. The player’s dedication to football makes them accept the conditions and the poor framework they must perform their sport within.Footnote28 Because there are no options. Research within football has, over many years, been conducted on men’s football, e.g. in the field of physiology, injury, and medicine. A bibliometric exercise shows that “ … articles addressing females are lagging research addressing males”, 919 articles out of 5924.Footnote29 The knowledge of men’s football has been transferred to the development of physical training programs for teams and individuals in women’s football. Lack of specific knowledge about women’s physiological and psychological conditions may have caused significant errors in developing women footballers’ performance. Furthermore, research on the early termination of football careers is lacking too, but some studies have investigated this empirically.Footnote30 Although, when you look at the findings in these studies, you do get a clear picture of why women end their football careers early and earlier than men.

FIFA and UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) have each developed strategies for women’s football, both at the grassroots and elite level. The first strategy for women’s football ever done by FIFA, was in 2018, and UEFA followed in 2019 with “Time for action”. Both strategies highlight the enormous growth of girls’ and women’s football and pave the way for a bright future for the sport through their strategies. National football organizations are following up and in Norway “Elite football women” ([Topp Fotball kvinner] TFK) has initiated a strategy process for 2023–2028. These international reports, also with interviews of young players worldwide and the respondents in this study, tell us about grand ambitions for high achievements and dreams of a football career that can last over time and into a full-time professional footballer at the elite level, like elite men footballers. Many also dream of an international career. This study investigates the reasons for early terminated football careers for elite women footballers and the inhibitors that caused it despite their efforts, dreams, ambitions, and “a project of great dedication”.

Design

Institutional and researcher’s context

This study was conducted within the research project Female Football Research Centre (FFRC) at UiT, the Arctic University of Norway. The researcher has been a volunteer in women’s elite football for several years as a member of boards and support groups. Education and experience as a teacher in sports and as an athlete at an elite level give a depth of understanding about the challenges an elite athlete has. The experience provides immediate nourishment, understanding, and insight into the conditions and demands of women’s elite football. This subjective position is vital for the researcher to be aware of throughout the work. It is a first-person approach to a problematic “hard-to-reach” fieldFootnote31 and a high degree of awareness of one’s subjective position is necessary.

Methods

The semi-structured interviews were audio and visual recorded and transcribed verbatim. The seven respondents were marked with codes from W1-W7.

The choice of quotes underlines the core message of this article and support the interpretation of what is hidden deep within the text.

An interview guide was developed with open-ended questions to uncover and achieve in-depth knowledge of the respondent’s opinions, thoughts, and experiences about inhibitors for women’s elite football and reasons for early termination. Also, how they had experienced organizational facilitation – or lack of it, and football culture as inhibitors for them as footballers. A key question for the study was: Why did you quit football?

The study has an open, bottom-up approachFootnote32 where the respondents talk about their own experiences from their football careers as elite footballers. It uncovers phenomena from the unique and special to the general and typical.Footnote33 The subjective perspective of the researcher can impact the interpretation of data in a qualitative study like this one. However, using a thematic analysis (TA) process helps to minimize the influence of the researcher’s subjective views by providing a systematic and rigorous method for coding and organizing data. It is an incremental process where each step influences and shapes a new and broader understanding through several interpretation steps from the respondents via researchers to readers. The process progresses from specific details to a comprehensive understanding without asserting complete accuracy.Footnote34 Qualitative research often emphasizes the closeness to the research field to get a deeper understanding of the context. Quantitative data are deductive and have a closed approach, while qualitative data often has an inductive hermeneutic approach to capture the many layers an interview may reveal.Footnote35

Participants

Seven former elite women footballers from Norway were interviewed in this qualitative study. All of them started with football at 6–7 years old, and they all quit elite football at the period of 22–30 years of age.

Procedure

The respondents were recruited through an interest organization for athletes, NISO (the Norwegian Athletes Central Organization [Norske Idrettsutøveres Sentralorganisasjon]), which sent an invitation letter from FFRC to former elite women footballers and invited them to respond to the research invitation. It included information about the study, their rights, and the possibility to withdraw at any time before, during, or after the interview. Four of the respondents contacted the researcher and made an appointment for a video interview over Microsoft Teams using a video chat device. The three others took contact after a snowball effect from the first four. The research project was approved by the Norwegian Centre of research data (NSD). The interviews were conducted through video interviews over Microsoft Teams and lasted between 1 and 1,5 hours. The sample size of 5 to 10 participants, as suggested by Jacobsen (Citation2013), was considered adequate for in-depth analysis and sufficient to describe the phenomenon under investigation. Elite football in Norway is defined as the two top levels.

Analysis

The thematic analysis (TA) method is commonly used in qualitative research, including in sports research. According to Braun and Clarke,Footnote36 TA is a foundational method for qualitative analysis and allows for flexibility in the research process. In their 2019 article, they named the concept ’reflexive thematic analysis’, emphasizing the importance of the researcher’s own reflection and interpretation in the analysis process.Footnote37 It allows researchers an active approach through their own reflection and interpretation during the analysis process and the knowledge production process and contributes to achieve the deeper meaning and experience that comes to expression. It gives room for the informants’ broader stories through their experiences by discovering the implied meaning in the participants’ experiences.

In this study, the researcher chose to use Clarke and Braun’s Thematic Analysis due to its flexibility. The six-step process allows for a journey of “thinking, reflecting, learning”,Footnote38 and emphasizes the researcher’s reflexivity, theoretical engagement, and creative scholarship.Footnote39 The process gives the “researchers … an active role in the knowledge production process through … a reflexive engagement with theory, data, and interpretation”.Footnote40 The researcher followed the six-step process, (1) familiarizing oneself with the data, (2) generating codes, (3) constructing themes, (4) reviewing potential themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. It incorporates reflexiveness and theoretical engagement in the discussion and literature review, which allowed for deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences.

Familiarizing with the data: The researcher transcribed the interviews and read through them multiple times. This step was just to get to know the data, and the process created a close familiarity and a deep understanding of each interviewee’s perspective.

Generating codes: The researcher conducted a process by selecting all relevant text and divide it into sequences. The next step was to systematically divide the data into concise codes using mind maps and colours. The coding process was guided by the research questions. This process was repeated several times to ensure a correct coding of the data.

Constructing themes: The coded data were sorted into potential themes reflecting a pattern of shared meanings guided by the research questions that formed the core concept of the study.

Reviewing potential themes: The next step was to ensure the sorted data answered the research questions and then merge into fewer themes relevant to the research questions and the core message of this study.

Defining and naming themes: With the themes defined, it was necessary to look for potential subthemes. The researcher defined three main themes: a) health-related issues, b) organizational issues, and c) cultural issues. The process shows several subthemes, which were named guided by the main themes and the core concept of this study: The reasons why women footballers terminate their football career at an early age.

Producing the report: In this last section, the data, the quotes, and the analysis were put into a larger context and transformed into more generic principles in relation to the literature. Even though there are few informants in this study, their experience may be well known for many women footballers around the world.

An interview guide was developed with open-ended questions to uncover and achieve in-depth knowledge of the respondent’s opinions, thoughts, and experiences about inhibitors for women’s elite football and reasons for early termination. Also, how they had experienced organizational facilitation – or lack of it, and football culture as inhibitors for them as footballers. A key question for the study was: Why did you quit football? The seven respondents are marked with codes from W1-W7.

Results

An important entry to understand the complexity of reasons for early termination of football careers for women footballers were the three themes revealed by the analyses process: health-related issues e.g. exhaustion and burnout, organizational issues e.g. resources and facilitation, and culturally related issues e.g. attitudes, prejudice, and lack of equality. The study’s participants reported that not having football as a full-time job negatively impacted their performance in training and matches, and that the heavy workload was the primary reason for early termination. “It ended with an exhausting feeling. I went tired to practice. I got tired at training. And I got into a bad circle. It couldn’t be that way” (W1).

Health-related issues

All respondents reported experiencing burnout to varying degrees. The constant demands of training, work, and school became too much after years of this daily routine, with one participant suffering long-term health consequences from the strain. The high demands of studies, work, and elite football resulted in lasting health damage that negatively impacted their overall well-being. Several participants reported feeling depressed and experiencing low moods. Some felt depression after retiring from football but eventually found relief in a less demanding lifestyle. Other factors, such as lack of motivation and malnutrition, also had an impact on their mental and physical health, hindering their performance, growth, and drive.

Quotes:

W5: You… (she laughs a little), believe it or not, I collapsed. The total package became too much, so I have struggled with ME and chronic fatigue. So, I fainted; out of nowhere, when I was at work, I fell to the ground and never really got back again. So, like that (snapping her fingers), I went from being an elite athlete to becoming in need of care. I have worked my way back nicely, and I’m doing fine, but I’m not working full-time. I thought I was good at juggling studies, work, and football, but I was going to pay for it later.

W1: “I lay on the couch for a whole year after quitting football”.

Q: How did you experience the pressure physically and mentally with your studies, work, and football?

W2: Extremely demanding! Before you were done with one thing, you were in the planning phase of the next thing. And, of course, this harmed my recovery; I didn’t get enough rest. I got up, went to school, went straight to football practice, came home, and had to study in the evening, and that’s how the days went by. That’s what happened every day. I studied, worked, and played football, and that’s maybe where it started to get more demanding than I could manage.

W3: “You could call it depression without me knowing the definition of depression, but I was way down. Little things were very heavy”.

W7: I was very tired for quite a while, but at the same time, after I quit, it removed a lot of the stress I had in my everyday life. Just not having to stress from work, eating a slice of bread on the subway on the way to training, made you get a little more peace of mind in everyday life; it became a relief.

W2: “I lost my confidence, and then my motivation. I got bored – after finally achieving my goal to join the national A-team at 27 years old, I was tired, exhausted, and quit the following year”.

Organizational issues

Finances/Funding

All participants faced financial difficulties during their time as elite footballers. They received little or no salary or benefits from their clubs and had to rely on financial support from their parents, living at home, or student loans. The governing body for women’s elite football, TFK, had limited funds for distribution due to a lack of support from the business community, leaving clubs to mostly self-fund. All participants had to take on additional jobs alongside football and studies to make ends meet, a common experience for women footballers globally. They felt that women’s football was perceived as a hobby and received nothing in return beyond the enjoyment of playing. As a result, they were forced to choose between a football career with limited income or pursuing another career that offered financial security.

Quotes:

W2: “I never had the opportunity to just concentrate on football; it was like having two full-time jobs all the way. I felt like it stopped my progression because I had to work 100 percent paid work outside of football”.

W6: ’ If football had been my job and what I was going to concentrate on, I would have played football longer because that would have been my job while covering my livelihood. I would have had enough finances then, and I would have developed more as a footballer’.

W5: “You’ve got to have another job in addition to football; you’re going to get burned out; you can’t get it going around financially”.

“Professionalism is required as a player, but you don’t get paid back”.

W4: “It was the economy that made me quit, that’s what made me unable to continue. Because I had to have a full-time job while playing football, and at the same time I also studied, and I got exhausted”.

Education

All participants attempted to balance their elite football careers with education. However, their workplace and universities did not make it easy for them to do so, making it challenging and often impossible to reconcile both. To manage their daily responsibilities, the participants in this study selected educational programs that were less demanding and more compatible with their football commitments, dropped classes with heavy practice schedules, and avoided more challenging educational programs. The decision between elite football and education became a struggle for the participants, and in most cases, they had to choose education over football. In some exceptional cases, the football career was given priority, as was the case with Hanne (22), who had to choose between becoming a nurse or playing in the Citation2018 Women’s World Cup for Norway in France. Her university did not accommodate her schedule, leading to excessive absenteeism from mandatory work requirements. She chose football and had to abandon her education.

Quotes:

W3: “I omitted all education that had practice, really everything that was demanding to make football life work”.

W6: “There was no facilitation on my courses, and I had to take the internship at the same time as the other students, even if it came at the same time as an important match”.

W2: “I chose the least demanding education, not the one I was most interested in, because I wanted to play as much football as possible and train as much as possible”.

Resources

Participants faced significant challenges due to limited access to resources, impacting their development as elite footballers. There was a scarcity of experienced coaches and support staff, inadequate equipment, and inadequate uniform conditions. Male elite footballers were given priority, receiving personal physiotherapy, while women elite footballers only had access to physiotherapy at clinics when injured. Participants felt that they didn’t receive enough support and resources from the NFF. Furthermore, the men’s clubs received significantly more funding than the women’s clubs, despite the women’s national team having a better international performance record than the men’s national team. The demands of elite football were high, but the resources and support available for women’s elite football did not meet these requirements. The participants called for more investment in women’s elite football to meet the high standards of national and international elite-level football.

Quotes:

W7 during the period she was injured: “Male footballers had good resources around them in club teams. We had a physiotherapist at the club, but he was partly on several teams and had also another job; he could not work with me daily”.

W4: As long as we have to train in the afternoon after a full working day, and in addition, have to share the track with age-specific teams, then there will be a big difference between men and women in elite football.

W5: “I think we’re going to see good footballers in the future give up because of poor frames and low resources”.

W6: No, I don’t feel that NFF has endorsed much. They provide support from time to time, but when I look at the distribution between the men’s and women’s teams and how much the men’s teams receive in bonuses by moving on to international championships, there is a large bias when it comes to allocating funds.

W2: “It’s common sense that the money needs to be managed so that all clubs can build up to certain professionalism. I think it will make us feel like they’re investing more in us. It will benefit the entire product”.

Cultural issues – attitudes, prejudice, and equality

The participants faced negative attitudes and prejudices from various sources, including the “football community”, fans, and the public. They encountered statements such as “it’s not real football, it’s not women” from within and outside football clubs and encountered derogatory messages on t-shirts and posters about women’s football. The participants felt that women’s football was seen as inferior and lower-ranked than lower-level boys’ football. Lack of support and commitment from the federation was an added burden for the participants, who only continued playing because of their love for the sport and the support of their teammates. They also felt a lack of belief in them, potential business partners was discouraged from investing in women’s football, claiming it was not a good product to sell. They reported a lack of equality throughout their football careers, pointing out the significant differences in access to finances and resources between men’s and women’s elite football. They faced old-fashioned attitudes from male coaches during coaching education, with one respondent being reprimanded for taking up too much space.

Quotes:

W7: Yes, he (the coach/supervisor) thought I was too engaged and took up too much space, that I had to let these other three boys get more space, and because I am a woman, I must not take up that much space. The commitment I had was too much, somehow.

W5: “There is an attitude in football. There is something primal about it, a culture that put women aside”.

W6: “It’s such a gender issue and an old-fashioned view. It doesn’t exactly help the development”.

W4: “It’s not exactly going fast (about NFF’s working process with developing women’s football). But it’s possibly naïve to think that it shou; it’s’s generational almost, so yes, it’s almost like we must have a generational change”.

W5: “I experienced harassment from the surroundings. ‘Oh yes, you’re a footballer, yes’, said in a very ironic tone. There is a lot of prejudice about being a women footballer, and I felt like I had to defend it”.

Q: If you were to stand on the podium at the NFF’s yearly football conference with a statement for women’s football, what would it be?

W4: Equal pay for equal work!

Discussion

Elite women footballers are fighting a battle on several fronts; health with a lack of restitution and rest, organizational where there are inadequate resources and funding, and a biased culture against women’s football. Their effort of balancing double and triple activities, which in themselves can be considered full-time jobs, becomes a burden too heavy over time. In comparison to full-time employed men elite footballers, these women start their day early, often after a short night’s sleep, with a morning training session. They then proceed to work or school, return to the field for another training session, and finally head home for a meal. In their free time, they either continue their studies or work additional jobs to support themselves. Coping with dual and triple career topics requires dedication and commitment from women footballers beyond the load people usually need to cope with. It becomes an overload, resulting in exhaustion and burnout. It may have serious consequences, such as prolonged adverse effects with chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors.Footnote41 The total amount of strain and decreasing performance are in the interviews described as reasons for the withdrawal from football. The respondents experienced less development and lower effectiveness at training and matches, which threatened their goals and ambitions for a football career and their identity as elite footballers. A spin-off effect was lower self-esteem, lower self-confidence, and declining motivation.Footnote42 It is an extensive and complex pressure that women footballers experience over time. Exhaustion is a critical factor for quitting football early and earlier than any of the respondents wanted. It is the core element in the definition of burnout.Footnote43 The fact that some of the respondents used a year or more to overcome exhaustion indicates the high demands these women are facing during their football careers. Based on the Job-Demand-Resource model (JD-R),Footnote44 an expanded version of Maslach’s (2001) hypothesis, and a model developed for interaction between services and professions,Footnote45 a model for exhaustion and burnout among elite women footballers may be as follow in :

The demands the elite women footballers face correlate with Demerouti’s references of “ … job demands as physicals, social or organizational aspects of the job that require sustainable and mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs”.Footnote46 Women footballers experience an “overabundance of requirement … as well as minimal assets offered … ”.Footnote47 Large demands do not correspond to the available resources and facilitation in elite women’s football.Footnote48 The requirements are very high and result in physiological and psychological costs for women footballers.

Findings indicate that the shortage of resources and support has a detrimental effect on the growth of these women footballers.Footnote49 A recent survey conducted by Norwegian BroadcastingFootnote50 revealed a significant disparity in funding allocated to the development of young male and female talent. On average, there is one coach per seventeen girls and one coach for every seven boys. Similarly, elite women’s football has fewer coaches and support teams compared to elite men’s football,Footnote51 which hinders individual and team development and performance. picture is seen in elite football, where there are fewer coaches and support teams in elite women’s football compared with elite men’s football.Footnote52 The lack of coaches on the training field directly impacts the quality of women’s elite football.

There are significant challenges with the facilitation of education as well. Elite football players (and other elite athletes) have a tough time managing both, and in the end, they must choose between the two.Footnote53 The respondents in this study chose less demanding academic programs without too many internships. They all reported that they would have chosen education while playing football to secure their future after a football career, regardless of the extra load. They meant that it would be possible to pursue both simultaneously if education was facilitated to make it easier for athletes to manage both.

Throughout the history of women’s football, they have had limited access to resources compared to men’s football. This disparity affects all aspects of the sport, including finances, coaching, support staff, and facilities, such as fewer playing fields and inadequate changing rooms. The lower budget for women’s elite football has resulted in limited access to crucial resources that could enhance the performance of female football players (according to information from NFF and TFK in 2022). Efforts by NFF and TFK to address this issue include economic support, but the limited budget in women’s football still restricts professionalize elite women’s football. Women elite footballers have been side-lined and discriminated related to elite men footballers, but also to lower-level of men’s football.

Elite women’s football is growing more commercialized, but they are far from the level of elite men’s football. By looking at the vast financial sums in men’s elite football internationally, it is a timely question whether women’s football should seek to reach that level, ethically and morally. However, the unequal distribution of funds between women’s and men’s football will continue to perpetuate the disparities. At the same time, expectation for the quality and performance for elite women’s football are rising both nationally and internationally. An increased funding within women’s football is essential for reaching equality between women’s and men’s elite football. Significant efforts must be made in the areas of finances, resources, and facilitation to meet the growing demands of women’s football.

Cultural factors such as attitudes, equality, and prejudice, significantly impact the conditions of elite women’s football performance, and it is mostly men carrying out these cultural aspects. All respondents experienced male dominance in football during their years as players, and later when pursuing the role of a coach. In addition to facing economic challenges, limited resources, and subpar equipment and training facilities, negative attitudes and traditional values are major hindrances in their daily football experience. Although progress are made, male dominance remains a persistent challenge in women’s football.Footnote54 Moreover, it seems to be accepted and considered normal, unlike in other fields such as education where gender differentiation is not tolerated.Footnote55 This acceptance aligns with Beauvoir’s notions in her book “Le deuxième sexe” about women as the second gender.Footnote56 She claims that women are reduced to “the absolute other”, controlled by the first sex, men. He is the positive part of the two poles, and women are the negative pole. The woman appears negative to the extent that any decision is attributed to her as a limitation.Footnote57 Over thousands of years, a historical perception is built up where the past defines the present. If we look at the word woman/female, women are defined as the other sex by adding an initial before the word man/male. Beauvoir claims that “humanity is male, the man does not define the woman in herself but seen in relation to him”.Footnote58 Women’s football is not viewed as its own sport, but rather as inferior to men’s football. The understanding of women’s football as less worthy than men’s football, enduring derogatory and sometimes very hurtful comments about women footballers”. In society, the term football player is automatically as associated with men, while women footballers must use the word ‘woman’ before ‘footballer’ to be recognized.Footnote59 It refers to the third type of mismatch in MBI (the Maslach Burnout Inventory), and the lack of rewards for the work people do.Footnote60In Smith’s conceptual model,Footnote61 low rewards and low social support are central factors for burnout. Traditional gender roles are reproduced in sports organizations,Footnote62 and male privilege and dominance are still the dominant factors despite the positive developments taking place in sports organizations today.Footnote63 The attitudes of football leaders” are essential for women footballers to achieve their goals and ambitions.Footnote64 Women footballers do not receive the same recognition and rewards as male footballers, from a young age to adulthood. The unequal allocation of resources between men and women’s football only further contributes to the premature end of many female footballers’ careers.

In spite of the challenges, the respondents in the study found ways to manage their daily responsibilities and pursue their athletic goals by living frugally, maximizing their time, and balancing their commitments to training, work, and education. Despite the demands on their time and energy, they remained dedicated to their sport, but in the end had to prioritize their health and financial stability.

Summary remarks

This study may contribute to a better understanding of the serious consequences for the elite women footballers caused by the overload they have combining their daily dual and often triple career activities. Earlier research are done on burnout among elite athletes and specifically coaches, but this study present a specific focus on women footballers and the conditions they must endure to perform their sport. The reasons for the early termination of the football career for women footballers are several, e.g. economic, which is understandable since there is a small amount of funding for women’s football in Norway. This has a direct impact on organizational factors such as resources and facilitation. Another not-so-understandable reason in 2023 is the cultural issue with attitudes, prejudices, and discrimination against women’s football and women footballers. This is a problem rooted in history and traditional patriarchal thinking of what and for whom the sport of football is meant, and a problem not unique to Norway.

The last year’s enormous growth of women’s elite football has led to increased attention from spectators, media, sponsors, and business partners, signalling a new era for the sport. Increased funding for women’s football creates opportunities for facilitation to support development by meeting the demands in national and international elite football. An important question to ask in a further investigation is if this is enough to prevent early termination due to exhaustion and burnout. This study shows that a reduction of the daily heavy burden with dual and triple career will be necessary for reaching the goals and ambitions for each women footballer, and women’s elite football in Norway. It requires full-time employed women footballers to create equal opportunities for women footballers and promote professionalism in the sport.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the Tromsø Research Foundation and UiT, the Arctic University of Norway. Thanks to these institutions, research has been made possible. Thanks to colleagues at RKBU, UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, Monica Martinussen, and Lene-Mari Potulski Rasmussen for their reading and comments and their contribution to their version of the JD-R model.

Disclosure statement

The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the article and the views expressed.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [LW]. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Culvin, “Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England”.

2. FIFA, Women’s Football Member Associations Survey Report 2019.

3. UEFA, UEFA Strategy for Women’s Football on Track to meet Ambitious Targets.

4. FIFPro, Raising Our Game – Women’s Football Report.

5. Beauvoir, Det Annet Kjønn [Le deuxième sexe], 7.

6. FIFPro, Raising Our Game – Women’s Football Report.

7. FIFA, FIFA Benchmarking Report Women’s Football.

8. Ibid.

9. Portas Consulting, Top Football Women – Toppserien Benchmarking Report. Understanding How Toppserien Compares to Leading European Women’s Football Leagues.

10. Maslach and Leiter, “Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and its Implications for Psychiatry”, 103.

11. Freudenberger, Burnout: How to Beat the High Cost of Success, 103.

12. Maslach, “Understanding Burnout: Definitional Issues in Analyzing a Complex Phenomenon”.

13. Smith, “Towards a Cognitive-Affective of Athletic Burnout”, 36.

14. Groenewal et al., “Burnout and Motivation in Sport”., Goodger et al. 2007; Gustafsson et al., “Conceptual Confusion and Potential Advances in Athlete Burnout Research”; Chen et al., “Relation of Perfectionism with Athletes” Burnout: Further Examination’; Hassmén et al., “Coach Burnout in Relation to Perfectionistic Cognitions and Self-Presentation”; Lundkvist, “Side Effects of Being Tired: Burnout Among Swedish Sport Coaches” (PhD diss., Umeå University, 2015); Lundkvist et al., “The Prevalence of Emotional Exhaustion in Professional and Semiprofessional Coaches”.

15. Schaffran et al., “Burnout in Sport Coaches: A Review of Correlates, Measurement and Intervention”.

16. Smith, “Towards a Cognitive-Affective of Athletic Burnout”, 40.

17. Freudenberger, “The Staff Burn-Out Syndrome in Alternative Institutions”; Smith, “Towards a Cognitive-Affective of Athletic Burnout”.

18. Leiter and Maslach, The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress.

19. Martinussen et al., “Interaction Between Services and Professions”.

20. Smith, “Towards a Cognitive-Affective of Athletic Burnout”.

21. Hassmén et al., “Coach Burnout in Relation to Perfectionistic Cognitions and Self-Presentation”.

22. Culvin, “Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England”.

23. The FA, The Football Association: The History of Women’s Football in England; Culvin, “Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England”.

24. The FA, The Football Association: The History of Women’s Football in England.

25. Lie and Rognerud, “Får tre ganger så mye støtte av norsk fotball [Gets Three Times as Much Support from Norwegian Football]”.

26. Maslach et al., “Job Burnout”.; Freudenberger Citation1976; Gustafsson et al. (Citation2016).

27. The FA, The Football Association: The History of Women’s Football in England.

28. Culvin, “Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England”.

29. Kirkendall and Krustrup, “Studying Professional and Recreational Female Footballers: A Bibliometric Exercise”, 12.

30. Brandt-Hansen and Ottesen, “Caught between Passion for the Game and the Need for Education: a Study of Elite-level Female Football Players in Denmark”; Bjerksæter and Lagestad, “Staying in or Dropping Out of Elite Women’s Football – Factors of Importance”.

31. Culvin, “Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England”.

32. Maslach et al., “Job Burnout”.

33. Jacobsen, Hvordan gjøre undersøkelser? Innføring i samfunnsvitenskapelig metode [How to Do Surveys? Introduction to the Social Science Method], 171.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Braun and Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology”; Braun and Clarke, “What can ‘Thematic Analysis’ Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers?”; Braun and Clarke, “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis”.

37. Braun and Clarke, “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis”.

38. Ibid.

39. Braun and Clarke, “One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?”.

40. Bjørndal et al., “Stress-coping Strategies amongst Newly Qualified Primary and Lower Secondary School Teachers with a Master’s Degree in Norway”.

41. Maslach et al., “Job Burnout”.

42. Freudenberger, “The Staff Burn-Out Syndrome in Alternative Institutions”.

43. Ibid., 399; Maslach, Burnout: The Cost of Caring.

44. Demerouti et al., “The Job Demands – Resources Model of Burnout”.

45. Martinussen et al., Interaction Between Services and Professions.

46. Demerouti et al., “The Job Demands – Resources Model of Burnout”, 501.

47. Ibid.

48. Bjerksæter and Lagestad, “Staying in or Dropping Out of Elite Women’s Football – Factors of Importance”.

49. Ibid.

50. Lie and Rognerud, Får tre ganger så mye støtte av norsk fotball [Gets Three Times as Much Support from Norwegian Football].

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid.

53. Brandt-Hansen and Ottesen, “Caught between Passion for the Game and the Need for Education: a Study of Elite-level Female Football Players in Denmark”.

54. The FA, The Football Association: The History of Women’s Football in England.

55. Lie and Rognerud, Får tre ganger så mye støtte av norsk fotball [Gets Three Times as Much Support from Norwegian Football].

56. Beauvoir, Det annet kjønn [Le deuxième sexe].

57. Ibid., 35.

58. Ibid., 36.

59. Kaelberer, “Gender Trouble on the German Soccer Field: Can the Growth of Women’s Soccer Challenge Hegemonic Masculinity?”.

60. Maslach, Burnout, The Cost of Caring.

61. Smith, “Towards a Cognitive-Affective of Athletic Burnout”., 40.

62. Cunningham and Sagas, “Gender and Sex Diversity in Sport Organizations: Introduction to a Special Issue”.

63. Kaelberer, “Gender Trouble on the German Soccer Field: Can the Growth of Women’s Soccer Challenge Hegemonic Masculinity?”.

64. Hellesøy, “God ledelse – Vaksinasjon mot utbrenning [Good Management – Vaccination against Burnout]”.

Bibliography

- Archer, A., and M. Prange, ‘“Equal Play, Equal Pay”: Moral Grounds for Equal Pay in Football’, Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 46, no. 3 (2019): 416–436. doi:10.1080/00948705.2019.1622125.

- Beauvoir, S., Det Annet Kjønn [Le deuxième sexe]. (Oslo: Pax forlag, 2000).

- Bjerksæter, I.A.H., and P.A. Lagestad, ‘Staying in or Dropping Out of Elite Women’s Football–Factors of Importance’, Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4, (2022): 1–11. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.856538.

- Brandt-Hansen, M., and L.S. Ottesen, ‘Caught Between Passion for the Game and the Need for Education: A Study of Elite–Level Female Football Players in Denmark’, Soccer and Society 20, no. 3 (2019): 494–511. doi:10.1080/14660970.2017.1331161.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke, ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke, ‘What Can “Thematic Analysis” Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers?’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9, no. 1 (2014): 1–2. doi:10.3402/qhw.v9.26152.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke, ‘Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis’, Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11, no. 4 (2019): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Chen, L.H., Y.H. Kee, M.Y. Chen, and Y.M. Tsai, ‘“Relation of Perfectionism with Athletes” Burnout: Further Examination’, Perceptual and Motor Skills 106, no. 3 (2008): 811–820. doi:10.2466/pms.106.3.811-820.

- Consulting, P. Elite Football Women – Elitepserien Benchmarking Report. Understanding How Elitepserien Compares to Leading European Women’s Football Leagues (London: Portas Consulting, 2021).

- Culvin, A., ‘Football as Work: The Lived Realities of Professional Women Footballers in England’, Managing Sport and Leisure (2021): 1–14. doi:10.1080/23750472.2021.1959384

- Cunningham, G., and M. Sagas, ‘Gender and Sex Diversity in Sport Organizations: Introduction to a Special Issue’, Sex Roles 58, no. 1–2 (2008): 3–9. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9360-8.

- Demerouti, E., W. Nachreiner, and F. Schaufeli, ‘The Job Demands–Resources Model of Burnout’, The Journal of Applied Psychology 86, no. 3 (2001): 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

- FIFA. Women’s Football Member Associations Survey Report 2019 (Zürich: FIFA, Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 2019).

- FIFA. FIFA Benchmarking Report Women’s Football (Zürich: FIFA, Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 2021). https://www.fifa.com/news/bareman-fifa-benchmarking-report-will-help-us-grow-the-women-s-game.

- FIFPro. Raising Our Game - Women’s Football Report (Hoofddorp: International Federation of Professional Footballers, 2020). https://fifpro.org/media/1n4mp3ht/fifpro-womens-report_eng-lowres.pdf.

- Freudenberger, H.J., ‘The Staff Burn–Out Syndrome in Alternative Institutions’, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 12, no. 1 (1975): 73–82. doi:10.1037/h0086411.

- Freudenberger, H.J., Burnout: How to Beat the High Cost of Success. (New York: Bantam Books, 1980).

- Groenewal, P.H., D. Putrino, and M.R. Norman, ‘Burnout and Motivation in Sport’, Psychiatric Clinics of North America 44, no. 3 (2021): 359–372. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2021.04.008.

- Gustafsson, H., E. Lundkvist, L. Podlog, and C. Lundqvist, ‘Conceptual Confusion and Potential Advances in Athlete Burnout Research’, Perceptual and Motor Skills 123, no. 3 (2016): 784–791. doi:10.1177/0031512516665900.

- Harrison, G.E., E. Vickers, D. Fletcher, and G. Taylor, ‘Elite Female Soccer Players’ Dual Career Plans and the Demands They Encounter’, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 34, no. 1 (2022): 133–154. doi:10.1080/10413200.2020.1716871.

- Hassmén, P., E. Lundkvist, G.L. Flett, P.L. Hewitt, and H. Gustafsson, ‘Coach Burnout in Relation to Perfectionistic Cognitions and Self-Presentation’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23 (2020): 8812. doi:10.3390/ijerph17238812.

- Hellesøy, O.H. God Ledelse – Vaksinasjon Mot Utbrenning [Good Management – Vaccination Against Burnout]’, in Utbrent: Krevende Jobber – Gode Liv [Burned Out: Demanding Jobs - Good Lives]. 2002. ed. Roness, A. and S.B. Matthiesen Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 320–343.

- Hjelseth, A., and J. Hovden, ‘Negotiating the Status of Women’s Football in Norway: An Analysis of Online Supporter Discourses’, European Journal for Sport and Society 11, no. 3 (2014): 253–277. doi:10.1080/16138171.2014.11687944.

- Jacobsen, D.I. Hvordan gjøre undersøkelser? Innføring i samfunnsvitenskapelig metode [How to do Surveys? Introduction to the Social Science Method] 2nd ed. (Kristiansand: Høyskoleforlaget, 2013).

- Johannesen, B.J. ‘Landslags-Leine Ga Opp å Bli Sykepleier: Det Kom Mange Tårer [National Team-Leine Gave Up Becoming a Nurse: There Were Many Tears]’, Verdens Gang, VG. November 1, 2018.

- Kaelberer, M., ‘Gender Trouble on the German Soccer Field: Can the Growth of Women’s Soccer Challenge Hegemonic Masculinity?’, Journal of Gender Studies 28, no. 3 (2019): 342–352. doi:10.1080/09589236.2018.1469973.

- Kirkendall, D.T., and P. Krustrup, ‘Studying Professional and Recreational Female Footballers: A Bibliometric Exercise’, Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 1, no. S1 (2022): 12–26. doi:10.1111/sms.1401.

- Leiter, M., and C. Maslach, The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Wiley Company, 1997).

- Lie, S., and A. Rognerud. ‘Får tre ganger så mye støtte av norsk fotball [Gets Three Times as Much Support from Norwegian Football]’. NRK Norwegian Broadcasting. May 31, 2022. https://www.nrk.no/sport/xl/isak-_15_-far-tre-ganger-sa-mye-stotte-av-norsk-fotball-som-helle-_15_-1.15979680 (Accessed June 30, 2022).

- Lundkvist, E. ‘Side Effects of Being Tired: Burnout Among Swedish Sport Coaches’ PhD diss., Umeå University. 2015. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:780599/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Lundkvist, E., H. Gustafsson, D. Madigan, S. Hjälm, and A. Kalén, ‘The Prevalence of Emotional Exhaustion in Professional and Semiprofessional Coaches’, Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology (2022): 1–14. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2021-0039.

- Magnussen, J., and J. Baardsen. ‘OBOS Ville Sponse Kvinnefotballen Med Millioner - Hørte Aldri Noe Fra NFF [OBOS Wanted to Sponsor Women’s Football with Millions – Never Heard Anything from the NFF]’, Verdens Gang, VG. November 16, 2017.

- Martinussen, M., F. Adolfsen, and S. Kaiser. ‘“Interaction Between Services and Professions”, in Familiens Hus: Organisering, Samhandling Og Faglige Perspektiver [The Family House: Organization’. In Interaction, and Professional Perspectives], in ed. M. Martinussen, M. Bellika, and F. Adolfsen, 48–67. Tromsø: UiT, the Arctic University of Norway, RKBU Nord, 2019.

- Maslach, C. ‘Understanding Burnout: Definitional Issues in Analyzing a Complex Phenomenon’. In Job Stress and Burnout, in ed. W.S. Paine, 29–40. London: Sage Publication, 1982.

- Maslach, C., Burnout: The Cost of Caring. (Cambridge: Malor Book, 2003).

- Maslach, C., and M.P. Leiter, ‘Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and Its Implications for Psychiatry’, World Psychiatry 15, no. 2 (2016): 103–111. doi:10.1002/wps.20311.

- Maslach, C., W.B. Schaufeli, and M.P. Leiter, ‘Job Burnout’, Annual Review of Psychology 52, no. 1 (2001): 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Schaffran, P., S. Altfeld, and M. Kellmann, ‘Burnout in Sport Coaches: A Review of Correlates, Measurement and Intervention’, Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Sportmedizin 67, no. 5 (2016): 121–125. doi:10.5960/dzsm.2016.232.

- Smith, R.E., ‘Towards a Cognitive–Affective of Athletic Burnout’, Sport Psychology 8, no. 1 (1986): 36–50. doi:10.1123/jsp.8.1.36.

- The, F.A. ‘The Football Association: The History of Women’s Football in England.’ 2022. https://www.thefa.com/womens-girls-football/history.

- UEFA. UEFA Strategy for Women’s Football on Track to Meet Ambitious Targets. (Nyon: UEFA, Union of European Football Associations, 2019).