ABSTRACT

Football serves as a fetish for war, replaying past conflicts and sometimes setting off new ones. Deploying social identities theory and dramaturgy theory, we follow up on this assertion to explore how the historic 2022 FIFA World Cup semi-final qualification by Morocco’s senior men football team exposed historical and contemporary conflicts framing Morocco today. Celebrating greatness, Moroccan winger Sofiane Boufal dedicated the victory to Moroccans, Arab and Muslim people. The disavowal of sub-Saharan Africa and the negation of pan-African solidarity triggered social media debates which spilled into quotidian lives of Africans. Critical discourse analysis was employed to analyse purposively sampled conversations on X (formerly Twitter), relating to Boufal’s remarks. We demonstrate how Morocco’s success [re]ignited identity wars and brought into stark relief attendant ontological, philosophical and metaphysical dynamics. We advance scholarly discourses about consumption of mega global sporting events and their symbiosis with politics of belonging in the global South.

Introduction

This study explores intersections of Morocco’s nationalism, religious-ethnic wars, continental identity politics and digital football fandom during the Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup. Morocco is an African Arab country with a chequered history punctuated by ethnic, racial, religious and political conflicts. Despite ‘cultural wars’ appearing dormant, they surfaced on combustible digital platforms during Morocco’s moment of football greatness in Qatar. As observed by Dolby, identity is not a settled timeless, fixed entity but ‘a constant process of formation and change that occurs within a global or local matrix and that is both formed by and expresses structures of power’.Footnote1 There is a paucity of systematic academic examination of the intersections of mega global sporting events, politics of belonging, power, nationalism, diversity issues and digital fandom in the global South. Therefore, digital football fandom discourses provide us an important entry point to revisit and introspect Morocco’s unsettled nationhood and continental identity question. We seek to answer the question: In what ways do the discourses engendered by the Atlas Lions’ historic performance at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup reflect and refract the connections of Moroccan nationalism, Arab exceptionalism, ambivalent pan-African solidarity and digital fandom?

The concept of ‘Arab exceptionalism’ is commonly used in scholarship to refer to the notable lack of democratic governance and prevalence of authoritarianism in the Middle East and North African (MENA) region. This region is dominated by Arab and/or Muslim values and culture.Footnote2 With regards to pan-Africanism, this refers to an ideology advancing that people of African descent have common interests hence they should be united both as a continent and people.Footnote3 This movement was founded in the nineteenth century by intellectuals of African descent based in the Caribbean and North America, who saw themselves as belonging to a single negro race.Footnote4 However, pan-Africanism poses multi-dimensional challenges. For instance, critics note that at times pan-Africanism is confined to those regions of sub-Saharan Africa largely inhabited by darker-skinned people, thus excluding those lighter-skinned North Africans, most of whom speak Arabic as a first language.Footnote5

Morocco’s senior men national football team – the Atlas – Lions stunned the globe after a historic semi-final qualification at the Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup. The Atlas Lions became the first African Arab team to achieve this feat in the history of the FIFA World Cup. On their path to football ‘immortality’, the Atlas Lions eliminated global football powerhouses Spain and Portugal. Celebrating the historic win over Spain, a delighted Moroccan footballer Sofiane Boufal told the media that the victory was dedicated to Moroccans, Arab and Muslim people.Footnote6 However, following a social media backlash, Boufal issued an apology for failure to acknowledge the African solidarity to the Atlas Lions.Footnote7 Indeed, football unites, but equally divides. The failure to acknowledge the pan-African support in the triumphant discourse triggered social media debates which spilled beyond the boundaries of the football pitch into the everyday lives of Africans.

We deploy critical discourse analysis to interrogate conversations that ensued on selected microblogging site X (formerly Twitter) handles, in the aftermath of Boufal’s post-match interview after Morocco’s historic victory. We examine how Moroccan nationalism, Arab exceptionalism, ambivalent pan-African solidarity discourses manifested in digital football fandom spaces. We also examine how digital football fandom discourses revealed historical and contemporary identity politics, specifically race, ethnicity, religion and conflicts that frame a country we call Morocco today. What makes the analysis of these digital football fandom discourses compelling is how deeply sports are embedded in our daily lives, yet they are rarely subjected to scrutiny, particularly in the global South. Theoretically, we deploy an eclectic theoretical framework – fusing social identities theory and Goffman’s dramaturgy theory. Such a framework is important in analysing how the African and Arab identities were foregrounded and backgrounded on digital spaces during the period under study. We concur with the assertion that ‘identities are not only multiple and constantly shifting but also performative’.Footnote8 In the next section we briefly provide a historical context of cultural, ethnic and religious battles in Morocco.

Morocco’s dual Africa and Arab identity politics

Morocco’s dual Arab and African identity has always been a bone of contention since colonial times. National identities do not subsume all other forms of difference into themselves and are not free of the play of power, internal divisions and contradictions, cross cutting allegiances and difference.Footnote9 The North African country’s population is a patchwork of ethnic groups that through history, fortitude and twists in historical facts coalesced to form an empire that we now call Morocco. Fundamentally, Morocco is a Berber society. However, the current Moroccan identity is a fusion of Arab, African and Amazigh culture, which make Morocco one of the most diverse countries, with different languages, ethnicities and cultures.Footnote10 Ethnic groups in Morocco include the Berbers, also known as the Amazigh, which is the native identity of Morocco before the Arabs came to spread the Islam religion.Footnote11 This group constitutes approximately 40% of the population of more than 34 million.Footnote12 There are also Arabs who came as outsiders in the seventh century.Footnote13 In addition, there are also Muslims, Jews, atheists, non-religionists and Baha’is, Shias and Sunnis.Footnote14

Cultural and ethnic wars chronic in the Moroccan society are embedded in the country’s colonial experiences. Morocco is a former French colony. But colonialism in Morocco precedes French occupation.Colonial empires such as Romans, Vandals, Byzantines and the French occupied the Moroccan territory at different moments.Footnote15 Morocco was also a victim of Islamic Jihads in the Maghreb region in the eighteenth Century. The country was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate during the first half of the eighteenth century A.D.Footnote16 Thus, amongst all the colonial forces, the Islam and Arabs impacted on the Moroccan culture in significant ways.Footnote17 Despite the Arab ‘transformation’, some Amazighs across Morocco currently do not feel Arab, even though they are Muslim.Footnote18 Moreover, some Amazigh speak very little to no Arabic at all -they speak Tamazight languages.Footnote19 From this submission, it is therefore erroneous to assume that all Moroccans are Arabs. Arab and Muslim identities can be entirely independent, and not all Moroccans identify as Arabs.Footnote20

Morocco’s identity problems also have peculiarities in its geographical location. The country is located at the furthest part of North Africa. Kettani argues that while some Moroccans may claim they are not African, it is impossible to be Moroccan without being African.Footnote21 Morocco is a member of the African Union, albeit in 1984 it withdrew from the union in protest after the OAU’s (now AU) recognized the Sahrawi claim to the disputed territory of Western Sahara, admitting the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as a member state.Footnote22 Morocco re-joined AU in 2017.Footnote23 Upon return, King Mohammed VI said, ‘Africa is my home, and I am coming back home’.Footnote24 The decision to exit the African union often makes Morocco’s commitment to ‘Africanism’ questionable. As a matter of fact, some Moroccans are hesitant to identify with the African identity since they conflate‘Africanness’ with ‘blackness’.Footnote25

Geographically, Morocco is also close to Europe, specifically Spain. This could explain the reason why in 1987 Morocco applied to join the European Union, albeit without success. Morocco is also a member of the Arab League. Therefore, officially they belong to both cultural spheres.Footnote26 The country is also linked to the Middle East as it shares the same mother tongue language and the same religions (Arabs are not only Muslims, there are Christian and Jewish Arabs), and approximately the same political and social challenges.Footnote27 Although it is a member of the Arab League, referring to Morocco as an Arab state ignores the country’s actual ethnic composition and ethnopolitical dynamic.Footnote28 Our study is not interested in examining whether Moroccans are Africans or Arabs. Enough debate has been proffered on the subject. We demonstrate deep imbrications of Moroccan nationalism, Arab exceptionalism, ambivalent pan-African solidarity and digital fandom. In the next section we review some of the key studies focusing on global football events, media, fandom, nationalism and social identities in Africa.

Literature review

This section reviews literature around intersections of mega football events, fandom, nationalism and social identities in Africa and the Arab world. Admittedly, while there is a significant body of literature on the interface between African football fandom and cultural identities in general, studies locating the phenomenon in the context of global mega events are few and far between. This can be attributed to the fact that the FIFA World Cup was staged once on the African continent-South Africa 2010. On the other hand, the Citation2022 Qatar World cup was the first one in the Middle East or Arab region-in which Morocco is also a member.

The Citation2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa received global media attention than any other mega sporting event.Footnote29 However, most of the studies were concerned about development implications of this World Cup in South Africa and Africa in general.Footnote30 Expectations were high that the World Cup would bring economic development and financial opportunities to South Africa and the African continent.Footnote31 There is also a strand of literature examining connections of the Citation2010 FIFA World Cup to fandom, nationalism and social identity politics in South Africa.Footnote32 Focusing on the South African case, Ndlovu-Gatsheni contends that though nationalism and patriotism became ubiquitous during the one-month long tournament, renewed xenophobic attacks at the end of the World Cup spoilt the pan-Africanist spirit that was prevailing.Footnote33 This literature provides important insights on the centrality of football in [re]imagining nations. We extend the analysis by examining Morocco, a country with a contentious dual African Arab identity.

There is also a corpus of literature highlighting that football is an arena for the manifestation of inter-cultural struggle in the reproduction of boundary demarcations on the basis of factors such as ethnicity, race or religion.Footnote34 Race and ethnic challenges are deep-rooted in African football fandom.Footnote35 These are attributed to colonial legacies.Footnote36 Foer contends that ‘football defends the virtues of old-fashioned nationalism to an extent that even globalisation has failed to erode ancient hatreds in football’s great rivalries, therefore, threatening national cohesion’.Footnote37

Some of the studies on fandom cultures in the Arab world focus on countries such as Egypt, elaborate on how football is central in challenging authoritarianism.Footnote38 There is also a growing body of scholarship on football fandom and attendant discourses such as race, ethnicity, nationalism and hooliganism in Morocco.Footnote39 Some of the studies focus on discourses in Morocco’s digital football fandom.Footnote40 Importantly, in their study, Moreau analysed Facebook and Twitter comments, regarding the controversial cancellation of the Citation2015 African Cup of Nations in Morocco and its transfer to Equatorial Guinea, after an Ebola outbreak in West Africa.Footnote41 From the analysis of the fandom comments, scholars argue that studying social media conversations relating to a mega-sporting event could provide sociologically valuable insights about topics not typically directly associated with sport or health.Footnote42 We make an important follow up on this assertion and analyse digital fandom discourses which circulated during Morocco’s moment of football greatness.

Morocco’s historic performance at the Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup has already excited academic scrutiny. Warshel’s examination of the multiple meanings of Morocco’s historic performance at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup lays important foundation for our current research.Footnote43 Warshel contends that there are errors and oversights of facts in the constructions and mediatization of the historic performance by the Atlas Lions.Footnote44 For instance, contrary to what was publicized, Turkey was the first Arab team to qualify for the quarter finals of the FIFA 2022 World Cup and not Morocco.Footnote45 In addition, Senegal is also the first African team to qualify for the quarter finals of the FIFA 2022 World Cup. Critically, Warshel avers that though predicated on the Arab identity, much of Morocco is Amazigh, and the World Cup may rather be viewed as a series of victories by Amazigh players.Footnote46 We acknowledge the importance Warshel’s study in providing critical insights on some of the issues under investigation.Footnote47 This also ensures that our study is not conducted in a scholarly vacuum. However, the study by Warshel is a conceptual critical commentary of the phenomenon.Footnote48 Our study utilizes empirical data drawn from X hashtags which trended during the period under study. Using a Discourse Historic Approach, we analyse purposively sampled X posts locating them to Moroccan nationalism, Arab exceptionalism, and ambivalent pan-African discourses. Studies employing a digital fandom entry point to examine chronic cultural and ethnic wars framing a country we call Morocco are scarce. In the next section we discuss the conceptual framework guiding the study.

Conceptual framework

We deploy an eclectic theoretical framework -fusing social identities theory and Goffman’s dramaturgy concept, to explore how the record performance by the Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 FIFA World cup exposed deep-rooted historical, contemporary political, religious and cultural battles in the Moroccan society. The concept of social identity is credited to social psychologists.Footnote49 The theory focuses on ways to which people’s self-concepts are based on their membership in social groups such as sports teams, religions, nationalities, among others. Jenkins contends that social identity should be seen not so much as a fixed possession, but as a social process, in which the individual and the social are inextricably related.Footnote50 We are more persuaded by Stuart Hall’s theorization of social identities. Hall asserts that the question of identity is being vigorously debated in social theory due to the fact that the old identities which stabilized the social world for so long are in decline, giving rise to new identities and fragmenting the modern individual as a unified subject.Footnote51

Hall also argues that ‘identities are never unified and, in late modern times, increasingly fragmented and fractured; never singular but multiply constructed across different, often intersecting and antagonistic, discourses, practices, and positions’.Footnote52 Moreover, individual selfhood is a social phenomenon, but the social world is constituted through the actions of individuals.Footnote53 As such, identity is a fluid, contingent matter – it is something we accomplish practically through our ongoing interactions and negotiations with other people. In this respect, it might be more appropriate to talk about identification rather than identity.Footnote54 Because identity shifts according to how the subject is addressed or represented, identification is not automatic, but can be won or lost.Footnote55

Critically, Hall avers that identities are always in a state of flux. In addition, identities are constructed within, not outside, discourse.Footnote56 Therefore, we need to understand them as produced in specific historical and institutional sites within specific discursive formations and practices, by specific enunciative strategies.Footnote57 Identities in the contemporary world are defined from a multiplicity of sources-from nationality, ethnicity, social class, gender or race.Footnote58 Even national identities are not things we are born with, but are formed and transformed within and in relation to representation.Footnote59 We locate the discussion around intersections of Morocco’s nationalism, religious-ethnic wars, continental identity politics and digital fandom in this framework.

To make our analysis more robust, we bring social identity theory into conversation with Goffman’s concept of dramaturgy.Footnote60 Goffman provides what he calls a ‘dramaturgical’ account of social interaction as a kind of theatrical performance.Footnote61 The term ‘performance’ refers to all the activities of an individual which occur during a period marked by his/her continuous presence before a particular set of observers and which has some influence on the observers.Footnote62 Critically, individuals seek to create impressions on others that will enable them to achieve their goals, and they may join or collude with others to create collaborative performances in doing so.Footnote63 According to Goffman, performances take place at two levels- font stage and back stage.Footnote64 The back stage is the place where culture is more freely expressed, where feelings are more openly shared, and that these expressions are more limited to trusted individuals.Footnote65 The back stage connects to the private realm, where the audience is absent and the ‘performer can relax, he can drop his front, forgo speaking his lines, and step out of character’.Footnote66 However, when ‘on stage’, individuals tend to conform to standardized definitions of the situation and of their individual role within it, playing out a kind of ritual.Footnote67

Buckingham asserts that by suggesting that back-stage behaviour is closer to the truth of the individual’s real identity, Goffman overlooks the fact that all social interaction is a kind of performance.Footnote68 In the digital age where participation is characterized by pseudonymity, individuals are equally free to share their honest opinion on a topic.Footnote69 We examine identities as lived and as performed rather than just taken for granted. This is critical because not only are identities multiple and constantly shifting but identity is also performative.Footnote70 We treat performances and articulations of Arab and African cultural identities as an important reflection of a diversity of topical discourses that shape what ordinary Moroccans and Africans in general talk about and do not talk about, what they aspire to and what they fear, love and hate. In analysing the performance of social identities, we pay particular attention to the politics of backgrounding and foregrounding Morocco’s Africa and Arab identity on social media platforms during the FIFA 2022 World cup in Qatar.

Methodology

Our study deploys a qualitative interpretive research approach. The qualitative approach involves taking people’s subjective experiences seriously as the essence of what is real for them, making sense of the people’s experiences by interacting with them and carefully listening to what they say.Footnote71 We qualitatively examine intersections of digital football fandom, historical, contemporary political, religious and cultural battles in the Moroccan society during the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup. We analyse how the digital fandom discourses triggered by Morocco’s unprecedented success feeds and shapes other broader discourses such as Arab exceptionalism, pan African solidarity and Moroccan nationalism.

Discussions around Morocco’s continental identity politics dominated several social media platforms such as X, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, among others. However, for feasibility purposes, we confined our analysis to posts mined from purposively sampled Xhashtags. We employed virtual ethnography as the principal method for data collection. Virtual ethnography is a method that examines online interactions. We deployed non-participant observers on the X sites under study, relying on extant material. Salmons argues that extant material is created independently of any intervention, influence or prompts by the researcher.Footnote72 During the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup, a number of X hashtags such as #WorldCup2022, #FifaWorldCup, #Qatar2022, #Football and #FootballUnites trended. These hashtags were popular among fans, media and players who wanted to celebrate the event and share their opinions and emotions. We identified hashtags with high traffic during the period under study. We focused on hashtags namely: #AtlasLions, #GoMorocco and #AFRICA.We monitored conversations that ensued on these respective hashtags. We used API to mine the tweets and created our own archive. A purposive sample was then drawn from this population. We are aware of the ethical implications of data on social media sites. However, we only focused on data which was already in the public domain. We also removed meta-data from the X posts as a way of anonymizing them.

The sampled posts were subjected to Critical Discourse Analysis. In essence, we deployed the Discourse Historical Approach (DHA). The discourse-historical approach (DHA) belongs in the broadly defined field of critical discourse studies (CDS), or also critical discourse analysis (CDA).Footnote73 This approach is is a flexible and productive variety of CDS that always opts for a problem-oriented perspective.Footnote74 This approach is interdisciplinary and historical. We also ‘mine history’ in the analysis of the intersections of Moroccan nationalism, pan-African solidarity and Arab exceptionalism discourses. The texts are located and interpreted in the context of Morocco’s historical political, social and cultural struggles. We examined ideological underpinnings of purposively sampled X posts.

The Discourse-Historical Approach does not just look at the historical dimension of discourses, but is ‘more extensively – concerned with the aspects such as discourse and discrimination (such as racism, ethnicism, nationalism, xenophobia, Islamo- phobia)’.Footnote75 This approach has been used before to examine identity politics, migration, racism and discrimination, as well as on the relationships between discourse and politics.Footnote76 Discourse historic approach is also used in ‘analyzing discourse in the mainstream media and new social media’.Footnote77 This makes the approach more suitable for our analysis. Wodak argues that this approach emphasizes the need for ethnographic approaches in order to get insights into the phenomenon.Footnote78 Our approach is compatible with this assertion since we rely on virtual ethnography. Below we present findings using a thematic approach.

Findings

Morocco belongs to the amazigh not Arabs: ‘roots and routes dilemma’

Analyzed X posts reflect and refract the manifestation of dissensus over what constitutes the Moroccan national identity. The fragility of the Moroccan identity and attendant racial, religious and ethnic discourses were exposed during the country’s finest hour at the global football extravaganza in Qatar. A significant number of posts unproblematically foreground and framed the Moroccan identity as synonymous with Arab and Islam identity. However, such attempts were openly countered in some of the fandom posts which, hence turning the Moroccan identity into a site of struggle. Critically, posts by presumably members of the Amazigh ethnic group foregrounded the Amazigh identity whilst backgrounding the Arab identity. The comments emphasized that Morocco is not an Arab but Berber or Amazigh society. Questions of indigeneity also ran under the surface as Moroccan netizens competed to appropriate and bask in the reflected glory occasioned by the Atlas Lions’ finest performance at the Citation2022 FIFA World cup. The image () demonstrates our point.

To buttress their point, some of presumed members of the Amazigh society suggested that not only Morocco belongs to indigenous Africans, but other African countries in the Maghreb region as well. demonstrates our observation.

Figure 2. Stressing that countries in the Maghreb region belong to native Africans, and not Arabs.

Despite Hall arguing that social identities are more about routes that roots, it is evident that netizens sympathetic to the Amazigh group deployed an essentialist approach to identity.Footnote79 Contrary to the modernist approach which views identity as a fluid process of becoming, the essentialist perspective views identities as static and frozen in time and space.Footnote80 This explains why some members of the Amazigh group played the ‘roots’ card in order to substantiate their claim that Morocco belongs to indigenous Africans. The above post refers to Morocco’s colonial experiences, specifically the Islamic Jihads which conquered the Maghreb region in the eighteenth century. The foregrounding of the Amazigh identity in the analysed X posts and marginalization of the Arab identity can also be attributed to unhealed historical and contemporary wounds in the Moroccan society. The Amazigh often claim a history of discrimination and other forms of exploitation in an Arab dominated Moroccan society.Footnote81 The transformation of the indigenous Amazigh Moroccan identity into Arab identity was a result of brutal colonial conquests. below further buttresses our point.

The post above reflects on the politics of ‘othering’ prevalent in the Moroccan society in the post-independence epoch.Footnote82 The desire to be identified independently from the Arab identity is signified by the expression that we speak our own language (Tamazight). Language is a key marker of culture and identity.Footnote83 As reflected in the image above, some Moroccans do not feel Arab, even though they are Muslim.Binaries of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ are evident. Moreover, the image above insinuates that the Amazigh population are victims of symbolic forms of exploitation and oppression orchestrated by their Arab counterparts. National identity is also often symbolically grounded on the idea of a pure, original people or ‘folk’.Footnote84 However, in the realities of national development, it is rarely this primordial folk who persist or exercise power.Footnote85

Some of the comments demonstrate that some members of the Amazigh ethnic group were not amused by Arab identity tag or brand inscribed on the Atlas Lions. Some of the comments therefore expressed that the Atlas Lions team was largely constituted by Amazigh and not Arab players. It was claimed that these players could not speak Arabic since they grew up in Europe. As observed by BBC News, to counter and delegitimize attempts by pan-Arabists or Islamists seeking to hijack the Moroccan triumph for their own use, presumed Amazigh members circulated pictures of the Atlas Lions emblazoned with Amazigh symbols.Footnote86 Language and ethnic ‘roots’ became key markers for excluding and downplaying the contribution of Morocco’s Arab community. The Moroccan identity has historically been predicated on the combination of Arab ethnic identity and Darija Arabic linguistic identity, but a sizable percentage are ethnic Amazigh, not Arab.Footnote87

‘Moroccans are blatant racists, not Africans’

Despite spirited efforts by some of the members of the Amazigh community to claim that Morocco belongs to indigenous Africans, X discourses by presumably Africans from the sub-Saharan region currently residing in and outside Morocco countered such claims. The comments expressed that that Moroccans and all North Africans are on the African continent due to geographical and historical fate. However, but this cannot qualify them as Africans in the strictest sense, especially from a pan-African discourse. Below we demonstrate this point :

Figure 4. North Africans are in Africa due to geographical fate, but they are not Africans.

Some of the comments framed Moroccans as whites, rather than Africans. Despite the Amazigh considering themselves as Africans, posts by members, presumably from the sub-Saharan Africa generally attempted to exclude all Moroccans from the imagined African family of nations on the basis of light skins. below captures our point.

We argue that sentiments captured in the above post are not accidental but rather reflect how deeply football is embedded in our daily lives. Van Dijk contends that racism is perpetuated in subtle, symbolic, and discursive ways, that is, through everyday talk and texts.Footnote88 Racism is a common cancer stalking football across the globe and Morocco’s unprecedented success at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup allowed us to view how African football fandom are intertwined with this vice. We also noted that even though other African teams had been eliminated from the tournament with Morocco being the only remaining team in Qatar, some articulated that Morocco could not be given pan-African solidarity. Such comments intimated that the Atlas Lions were not representing the African continent but Qatar and the Middle East region. A significant number of comments rallied Africans to support the French team rather than the Atlas Lions. confirms our observation.

The endorsement of the French team as African ambassadors in Qatar is demonstrated in below.

The rationale to mobilize pan-African solidarity for the French team is attributed to the fact that a significant number of members of the French team had African footprints compared to the Moroccan team. Such players include Kylian Mbappe, Paul Pogba, N’Golo Kante, among others. Hall asserts that the question identity never went away, and the Moroccan case is no exception.Footnote89 We contend that some of the expressions by members of the Moroccan society illuminate on their chimerical pan-African dream.

Although football fandom is often characterized by bantering which may not be grounded in facts, we observed that some of the issues raised in the posts are tied to Morocco’s political history. The mining of historical twists and turns became strategic weapons in an attempt to delegitimize Morocco’s African continental identity. For instance, some of the posts reminded the world that Morocco once applied to join the European union, albeit without success. below testifies our observation.

Some of the comments accused Morocco of being a blatant racist country which discriminates black Africans from the sub-Saharan region. The politics of inclusion and exclusion became evident in some of the posts. and demonstrate our point.

Morocco is a country with an ethnically and racially diverse population. However, the country is yet to come to terms with its own black population and the impact of centuries of the trans-Sahara slave trade.Footnote90 Critically, ‘anti-black racism is pronounced, widespread, and largely denied by non-Blacks despite Morocco’s participation in the trans-Saharan slave trade for 13 centuries, and the socio-economic marginalization of the country’s Black minority up to present times’.Footnote91 Digital football fandom provides us an opportunity to view injustices and inequities prevalent in the Moroccan society. Jean-Pierre Bodjoko also asserts that whether native or not, the everyday reality for a black person in the Maghreb is to be an object of disdain and discrimination.Footnote92 This enquiry allows us to view how colonial cultures of toxic racism are perpetuated, and how nationalism, ethnicism, and anti-black racism are fostered and normalized in quotidian ways, including sport.

We also observed that despite frantic efforts to deny Moroccans the African identity, some articulated that Moroccans are Africans.In some of the analysed posts, it was expressed that Morocco’s African identity precedes the Arab identity. This is demonstrated in .

We argue that pan-Africanism and nativism philosophies contributed to the observed racist cultures in digital football fandom during Morocco’s period of football greatness. In fact, the politics of foregrounding and backgrounding Africa and Arab identities reflects on the failure of pan-Africanism to unite Africans. Appiah argues that pan-Africanism and nationalism can be sources of racism and exclusion which ultimately degenerates to ‘nativism’.Footnote93 This is because pan-Africanism is confined to those regions of sub-Saharan Africa largely inhabited by darker-skinned people, thus excluding those lighter-skinned North Africans, most of whom speak Arabic as a first language.Footnote94 Interestingly, some Moroccans do not want to be called Africans since they associate Africanness with blackness.Footnote95 The racist nuances in pan-Africanism be traced to the founding ‘fathers of Pan- Africanism and African nationalism, Alexander Crummell and Du Bois.Footnote96 The African Union has equally failed to create a coherent African identity across its member states.

‘Scoring goals beyond the football pitch: the Palestinian and Muslim cause’

Empirical data also demonstrates intersections of digital football fandom, political activism, resistance and Islam religion during the period under study. As argued by Ncube, digital media platforms present unprecedented opportunities to diverse fans to participate in heteroglossic carnivals of power that pit ‘ordinary’ people against other ‘ordinary’ people, and ordinary people against the elite.Footnote97 We observed that some of the fans presumably from the Arab and Islam community appropriated and deployed Morocco’s success to advance the Palestinian cause, and condemn continued Israeli occupation of the former. demonstrates our observation.

The above image trended in most hashtags analysed during the period. Salience was made that Morocco’s victory belonged to Palestine. Football occupies an important, complex, and controversial place in the cultural, religious, political, economic and entertainment lives of millions of the continent’s powerful and powerless, and rich and poor.Footnote98 Critically, in football, goals are scored beyond the pitch, but in political and economic formations as well.Footnote99 Our analysis shows that some sections of the Moroccan and perhaps African society condemned the waving of the Palestine flag. and demonstrates our point.

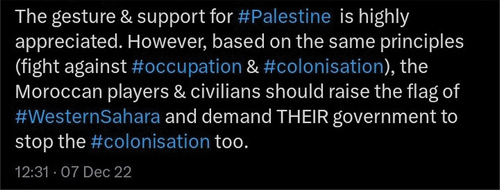

We also established that some of the comments, presumably from sub-Saharan African fans expressed that Africans could not sympathize with Palestine more than the Sahrawi Republic. This is because the African country has been suffering Moroccan occupation since 1975. and below exemplify our point.

Figure 16. Questioning the rationale behind Africans supporting Palestine ahead of Sahrawi Republic.

In 1984 Morocco withdrew from the union in protest after the OAU’s (now AU) recognized the Sahrawi claim to the disputed territory of Western Sahara.Footnote100 Such discourses found their way into digital fandom spaces during the Citation2022 FIFA World cup. There was a clear contest between pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism discourses. Armstrong and Giulianotti assert that ‘the game [football] provides a ready background for the expression of deeper social and cultural antagonisms that were existent anywhere on earth’.Footnote101

Morocco’s victory at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup was also read as symbolic redemption and relief moment for Muslims. We observed a spirited effort, presumably from Muslim sections to conflate Moroccan football triumph with Islam. From an Islam perspective, Morocco’s victory was symbolically victory for Islam. below supports our point.

Indisputably, Islam religion became a key talking point in a significant number of the posts analyzed. Identity politics entails a call for the recognition of aspects of identity that have previously been denied, marginalized, or stigmatized.Footnote102 Hall argues that ‘identities can function as points of identification and attachment only because of their capacity to exclude, to leave out, to render “outside”, abjected’.Footnote103 However, we observed that attempts to conflate Moroccan success with Islam religion were questioned in a voluminous number of posts. Critically, some expressed that reducing the Moroccan success to a victory for Arabism and Islam is an insult to various components of the Moroccan society. In other words, such definitions excluded some members of the Moroccan population. For example, confirms our observation:

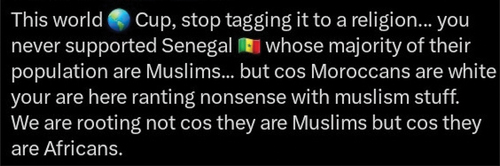

Some of the posts questioned the recurrence of Muslim discourses yet when teams such as Senegal played there was no mention of Islam. illustrates our observation.

Football is more than a game. There is a substantial body of literature exploring the intricate relationship between sport and religion, albeit with a huge bias towards American sports and culture.Footnote104 Religion continues to be a powerful social force in many people’s lives and at many sporting events, including football.Footnote105 Critically, the sacralization perspective contends that all sports are religious in their origins and are therefore essentially religious activities in disguise.Footnote106 From the Moroccan case, it is clear that digital terraces allowed for the performance and visualization of diverse religious performances, rituals, myths, and contestations in Morocco and beyond. Critically, from a dramaturgy perspective we contend that what transpired on the X sphere during Morocco’s escapade at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup is not a mere event but performance connected to quotidian discourses.

Discussion and conclusion

Morocco has a complex history characterized by rooted ethnic, racial, religious and internal conflicts. Digital fandom affords us an entry point to revisit and explore Morocco’s complex African Arab identity. Moreau and Roy contend that studies using social media lens are increasingly favoured in fandom studies.Footnote107 This is because the corpus of social media content related to sport is particularly rich, with online platforms not merely providing channels for propaganda or marketing, but also allowing freewheeling exchange of ideas and debates.Footnote108 Despite ‘cultural wars’ appearing hidden, they manifested on social media platforms in the aftermath of a historic performance by the Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup. The ghosts of European colonialism and Islamic Jihads which conquered the Maghreb region in the eighteenth century, remain imbricated with Morocco’s quotidian discourses.

We agree with the assertion that the question of identity never went away.Footnote109 Sport in general and football in particular is a microcosm of society.Footnote110 Moreover, sport like all social and cultural phenomena, is deeply implicated with power and identity discourses. Fletcher argues that researching sport is not, and should not be restricted to sport but should be seen as opening up wider avenues of enquiry into everyday life.Footnote111 Football fandom is one of the key sites where ordinary people express and experience nationalism.Footnote112 The Atlas Lions’ success at the Citation2022 FIFA World Cup allowed us to view historical and contemporary political, economic and cultural power relationships and conflicts that shape and structure the Moroccan nation.

Social media platforms became key collision points where discussions around Morocco’s national identity, pan-African solidarity and pan-Arabism discourses converged. Seleti asserts that ‘the media whatever form, shape, size or colour participate in identity politics’.Footnote113 The main source of contention in the analysed digital fandom conversations was Boufal’s submission that the Atlas Lions’ historic victory over Spain was for Morocco, Muslim and Arab nations. The exclusion of sub-Saharan Africa and the negation of pan-African solidarity in the triumphant discourse triggered social media debates which spilled beyond the boundaries of the football pitch into the quotidian lives of Africans. Critically, Boufal’s remarks [re]ignited ethnic, racial and religious identity wars, and brought into stark relief attendant ontological, philosophical and metaphysical dynamics. Questions such as ‘Who is an African?’ ‘What is Africa anyway?’ and ‘Are Moroccans Africans? characterized the discourses spawned by this controversy. Most of the posts suggested that Boufal’s sentiments were deliberate and aptly reflected on Moroccans’ perspective to Africanness. Hall asserts that every identity is an act of exclusion and power.Footnote114 Some Moroccans do not consider themselves as Africans, since they associate Africanness with blackness.Footnote115 We argue that such challenges reflect on the inadequacies of pan-Africanism to unite Africa as earlier discussed.

From the analysed data, we cannot avoid asking a provocative question: Do Moroccans exist? This is because analysed X fandom posts illuminate on the fragility of Morocco’s national identity. Seleti argues that defining a national identity is not a common-sense activity.Footnote116 Some rejected the idea of predicating the Moroccan identity on Arab and Islam cultural identities, preferring the ‘indigenous’ Amazigh ethnic identity. The question of roots and routes in social identities was brought to the fore.Footnote117 There was also a deliberate tendency to foreground the Amazigh and African identity, whilst backgrounding the Arab identity. Nativism came into play. By nativism, this refers to an ‘extreme’ narrow version of African nationalism conceptualizing African identities as frozen in time and space.Footnote118This form of nationalism is an aspiration towards ‘originary’ African ethnicities or identities.Footnote119National identities are contextual and are also informed and shaped by political and economic temperatures prevalent at a given moment.Footnote120 We observed that for Moroccans to survive, or to get what they want and desire, they slip and slide in and out of Arab and African identities. Such slip-and-slide identities are formed on the go, improvised to suit a variety of contexts. Depending with circumstances, Moroccans background or foreground the African and Arab identity. This confirms the assertion that identities are performances.Footnote121 This event is also a wakeup call for us to reflect and introspect on the feasibility of assigning ‘rigid’ national identities on certain countries. Modern nations are all cultural hybrids.Footnote122 Moreover, ‘the notion that identity has to do with people that look the same, feel the same, call themselves the same is nonsense’.Footnote123

Cultural identity battles rampant in the Moroccan society were also evident when some expressed that the Atlas Lions’ was more ideologically and politically symbolic. Those who subscribed to this perspective framed the team as an embodiment of Islam and pan-Arabism. This discourse is in sync with earlier observations that from the time Qatar was awarded the right to host the Citation2022 World Cup, its media framed the event as a ‘Victory for Islam and pan-Arabism’.Footnote124 Different versions of Moroccan, African and Arab nationalisms manifested and contested on digital fandom spaces during the period under examination. Racism, ethnicity and religious cultural differences became rampant. Digital media fandom spaces became conduits for hate speech and intolerance. From the Moroccan case, it is plausible to assert that it is very difficult to anchor a national identity around race, religion or ethnicity. This is because ‘we increasingly face a racism which avoids being recognised as such because it is able to line up “race” with nationhood, patriotism and nationalism’.Footnote125

To an extent, the victory of the Atlas Lions afforded footballers and fans with opportunities for activism. Traditionally, activism has been reserved for ‘activists’, but in the information, age dominated by the powerful presence of social media, ordinary citizens making use of mobile media and technological platforms consider themselves activists too.Footnote126 Digital fandom became crucial sites for the expression of individual and collective politics, power, difference, and resistance. Both footballers and fans were involved in impression management, which is about ‘successfully staging a character’.Footnote127 Moreover, Goffman contends that we create impressions through sign vehicles, which include both our spoken language and our body language.Footnote128 For example, some of the analysed posts commended Moroccan footballers for waving a Palestinian flag during their celebrations. This gesture was in solidarity with their Palestinian Arab mates who are battling Israel occupation of their territory. However, the discourse was countered by some Moroccans who disassociated from pan-Arabism and Islam discourses. Critically, some of the posts expressed that Morocco should equally evacuate Western Sahara territory. The African Union which is a key driver of pan-Africanism has tried to persuade Morocco to vacate from Western Sahara territory without success. There is also need for rethinking our identities in contemporary times beyond imagined traditional ethnicities and races. An identity based on race or skin colour becomes even more unacceptable today, when the mixes created by displacements and marriages between people of different races or cultures transform or disrupt sociological, ethnographic and identity realities.Footnote129

Overall, this study has demonstrated the entanglement of digital football fandom, social identities, politics and nationalism in Africa. Foer argues that ‘football defends the virtues of old-fashioned nationalism to an extent that even globalisation has failed to erode ancient hatreds in football’s great rivalries, thus threatening national cohesion’.Footnote130 Colonial cultures of toxic racism and religious discrimination played out and were perpetuated on social media platforms during Morroco’s historic performance at the Citation2022 World Cup. Our study confirms the assertion that football is far more than just a game. Beyond Morocco’s continental identity crisis, the study has also illuminated on Morocco’s historical and contemporary internal ethnic, religious and cultural problems. During a period of celebrating Morocco’s finest hour in the sporting world, the country’s unresolved identity question became a subject of debate on social media platforms. Critically, we demonstrate the connectedness of football fandom to ideological, cultural, ethnic, racial and social boundaries. We advance scholarly discourses about the consumption of mega global sporting events in the digital age and their symbiosis with the politics of belonging and nationalism in the global South.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Dolby, ‘Popular Culture and Public Space in Africa’, 13.

2. Stark, ‘Arab Exceptionalism? Tunisia’s Islamist Movement’.

3. Kuryla, ‘Pan-Africanism’.

4. Appiah, Pan-Africanism’.

5. Ibid.

6. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh? Morocco’s identity crisis’.

7. Ibid.

8. Mhiripiri and Tomaselli, ‘Language ambiguities, cultural tourism and the #Khomani’, 286.

9. Hall, ‘Introduction: who needs Identity’.

10. Afouaiz, ‘Morocco between the African and Arab identity’.

11. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh?’.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Kettani, ‘Assigning a rigid National Identity’.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’; Mohamed, ‘Morocco rejoins the African Union after 33 years’.

23. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’.

24. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh? Morocco’s identity crisis’.

25. Afouaiz, ‘Morocco between the African and Arab identity’; Kettani, ‘Assigning a rigid National Identity’.

26. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh?’.

27. Afouaiz, ‘Morocco between the African and Arab identity’.

28. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’.

29. Pannenborg, Football in Africa; Cottle, ‘Scoring an Own Goal?’; Haferburg, ‘South Africa under FIFA’s reign’; Mhiripiri and Mhiripiri, ‘Imploding or Perpetuating African myths through reporting South Africa 2010 World Cup Stories on Economic Opportunity’.

30. Haferburg, ‘South Africa under FIFA’s reign’.

31. Alegi, African Soccerscapes; Bond and Cottle, ‘Economic Promises and Pitfalls of South Africa’s World Cup’.

32. Cottle, ‘Scoring an Own Goal?’; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The World Cup, Vuvuzelas, Flag-Waving Patriots and the Burden of Building South Africa’.

33. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, ‘The World Cup, Vuvuzelas, Flag-Waving Patriots and the Burden of Building South Africa’.

34. Ben-Porat, ‘“Biladi, Biladi”’; Brown, Crabbe and Mellor, ‘Introduction’.

35. Alegi, African Soccerscapes; Bond and Cottle, ‘Economic Promises and Pitfalls of South Africa’s World Cup’; Fletcher, ‘These Whites Never Come to Our Game, What Do They Know about Our Soccer?’.

36. Alegi, African Soccerscapes; Bond and Cottle, ‘Economic Promises and Pitfalls of South Africa’s World Cup’; Nauright, Sport, Cultures and Identities in South Africa.

37. Foer, ‘How Soccer Explains the World’, 5.

38. Close, Cairo’s Ultras.

39. Elkhatir, Chakit and Ahami, ‘Factors influencing violent behaviour in football stadiums in Kenitra city (Morocco)’.

40. Moreau, Roy, Wilson and Dualt, ‘“Life is more important than football”’.

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid.

43. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Tajfel, ‘Differentiation between Social Groups’; Tajfel, and Turner, ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’.

50. Richard Jenkins points to the long history of debates about identity in his Social Identity.

51. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

52. Ibid., 4.

53. Buckingham, ‘Introducing Identity’.

54. Ibid.; Hall, Representation.

55. Hall, ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’.

56. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

57. Ibid.

58. Ibid.

59. Ibid.

60. Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

61. Ibid.

62. Ibid, 13.

63. Ibid.

64. Ibid.

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid., 115.

67. Ibid.; Williams, ‘Appraising Goffman’.

68. Buckingham, ‘Introducing Identity’.

69. Chibuwe, Mpofu, and Bhowa, ‘Naming the Ghost’.

70. Mhiripiri and Tomaselli, ‘Language ambiguities, cultural tourism and the #Khomani’, 286.

71. Ruddock, Understanding Audiences.

72. Salmons, Doing Qualitative Research Online.

73. Reisigl, and Wodak, Discourse and discrimination; Wodak, ‘Critical Discourse Analysis, Discourse-Historical Approach’.

74. Reisigl, ‘The Discourse-Historical Approach’.

75. Ibid., 47.

76. Wodak, and van Dijk, Racism at the top; Wodak, The discourse of politics in action.

77. Reisigl, ‘The Discourse-Historical Approach’.

78. Wodak, ‘Critical Discourse Analysis, Discourse-Historical Approach’.

79. Hall, Representation.

80. Ibid.

81. King, ‘Ending Denial’.

82. Hall, Representation.

83. Ibid.

84. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

85. Ibid.

86. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh?’.

87. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’.

88. Van Dijk, Communicating Racism.

89. Hall, ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’.

90. King, ‘Ending Denial’.

91. Ibid., 1.

92. Jean-Pierre Bodjoko, ‘Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb’.

93. Appiah, In my father’s house.

94. Appiah, ‘Pan-Africanism’.

95. Kettani, ‘Assigning a rigid National Identity’.

96. Appiah, In my father’s house.

97. Ncube, ‘The Beautiful Game?’.

98. Pannenborg, Football in Africa.

99. Ibid.

100. Warshel, ‘So-called firsts scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the Citation2022 World Cup football games’.

101. Armstrongand and Giulianotti, Fear and Loathing in World Football, 1.

102. Buckingham, ‘Introducing Identity’.

103. Hall, ‘Introduction’, 5.

104. Bain-Selbo, Game Day and God; Forney, The Holy Trinity of American Sports.

105. Forney, The Holy Trinity of American Sports; Scholes and Sassower, Religion and Sports in American Culture.

106. Scholes and Sassower, Religion and Sports in American Culture.

107. Moreau, Roy, Wilson and Dualt, ‘“Life is more important than football”’.

108. Halpern and Gibbs, ‘Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation?’.

109. Hall, ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’.

110. Messner, ‘Sports and Male Domination’; Giulianotti, Football.

111. Fletcher, ‘These Whites Never Come to Our Game, What Do They Know about Our Soccer?’.

112. Zenenga, ‘Visualizing Politics in African Sport’; Ncube, ‘“Highlander Ithimu Yezwe Lonke!”’.

113. Seleti, ‘Transition to Democracy and the production of a New National identity in Mozambique’, 47.

114. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

115. Kettani, ‘Assigning a rigid National Identity?’.

116. Seleti, ‘Transition to Democracy and the production of a New National identity in Mozambique’.

117. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

118. Appiah, In my father’s house.

119. Ncube, ‘Intersections of nativism and football fandom in Zimbabwean online spaces’.

120. Appiah, In my father’s house.

121. Mhiripiri and Tomaselli, ‘Language ambiguities, cultural tourism and the #Khomani’.

122. Hall, ‘Introduction’.

123. Hall, ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’, 49.

124. BBC News, ‘African, Arab or Amazigh?’.

125. Gilroy, ‘Against Race’, 87.

126. Hara, ‘Internet use for political mobilization’.

127. Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, 203.

128. Ibid.

129. Jean-Pierre Bodjoko, ‘Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb’.

130. Foer, How Soccer Explains the World, 5.

Bibliography

- Afouaiz, S. ‘Morocco Between the African and Arab Identity’. 2015. https://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/ffd-blog/sana-afouaiz/morocco-between-the-african-and-arab-identity.

- Alegi, P. African Soccerscapes. How a Continent Changed the World’s Game. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

- Appiah, K.A. In My father’s House: In the Philosophy of Culture. London: Methuen, 1992.

- Appiah, K.A. ‘Pan-Africanism’. in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge, 1998. https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/pan-africanism/v-1.

- Armstrong, G., and R. Giulianotti, eds. Fear and Loathing in World Football. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

- Bain-Selbo, E. Game Day and God: Football, Faith, and Politics in the American South. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009.

- BBC News. ‘African, Arab or Amazigh? Morocco’s Identity Crisis’. 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-64022940.

- Ben-Porat, A. ‘“Biladi, Biladi”: Ethnic and nationalistic Conflict in the Soccer stadium in Israel’. Soccer & Society 2, no. 1 (2001): 19–38. doi:10.1080/714004827.

- Bond, P., and E. Cottle. ‘Economic Promises and Pitfalls of South Africa’s World Cup’. in South Africa’s World Cup. A Legacy for Whom?, ed. E. Cottle, 39–71. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2011.

- Brown, A., T. Crabbe, and G. Mellor. ‘Introduction: Football and Community – Practical And theoretical Considerations’. Soccer & Society 9, no. 3 (2008): 303–312. doi:10.1080/14660970802008934.

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Buckingham, D. ‘Introducing Identity’. in Youth, Identity, and Digital Media, ed. David Buckingham, John D. The, and Catherine T. MacArthur, Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, 1–24. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

- Chibuwe, A., P. Mpofu, and K. Bhowa. ‘Naming the Ghost: Self-Naming, Pseudonyms, and Identities of Phantoms on Zimbabwean Twitter’. Social Media + Society 7, no. 3 (2021): 1–12. doi:10.1177/20563051211035694.

- Close, R. Cairo’s Ultras: Resistance and Revolution in Egypt’s Football Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2021.

- Cottle, E. ‘Scoring an Own Goal? The Construction Workers’ 2010 World Cup Strike’. in South Africa’s World Cup. A Legacy for Whom?, ed. E. Cottle, 101–115. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2011.

- Dolby, N. ‘Popular Culture and Public Space in Africa: The Possibilities of Cultural Citizneship’. African Studies Review 49, no. 3 (2006): 31–47. doi:10.1353/arw.2007.0024.

- Elkhatir, A., M. Chakit, and A.O.T. Ahami. ‘Factors Influencing Violent Behavior in Football Stadiums in Kenitra City (Morocco)’. Central European Management Journal 31, no. 2 (2023): 795–801.

- Fairclough, N. Analyzing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Fletcher, M. ‘These Whites Never Come to Our Game, What Do They Know about Our Soccer? Soccer Fandom, Race and the Rainbow Nation in South Africa’. Doctoral diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012.

- Foer, F. How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalisation. New York: Haper Collins, 2004.

- Forney, C.A. The Holy Trinity of American Sports: Civil Religion in Football, Baseball and Basketball. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007.

- Gilroy, P. Against Race: Imagining Political Culture Beyond the Color Line. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Giulianotti, R. Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999.

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books, 1959.

- Haferburg, C. ‘South Africa Under Fifa’s Reign: The World Cup’s Contribution to Urban Development’. Development Southern Africa 28, no. 3 (2011): 333–348. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2011.595992.

- Hall, S. ‘Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities’. in Culture, Globalization and the World System, ed. A. D. King, 41–68. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991.

- Hall, S. ‘Introduction: Who Needs “Identity”?’. in Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by S. Hall and P. du Gay, 1–17. London: Sage Publications, 1996.

- Hall, S. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage Publications, 1997.

- Halpern, D., and J. Gibbs. ‘Social Media As a Catalyst for Online Deliberation? Exploring the Affordances of Facebook and YouTube for Political Expression’. Computers in Human Behavior 29, no. 3 (2013): 1159–1168. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.008.

- Hara, N. ‘Internet Use for Political Mobilization: Voices of the Participants’. First Monday 13, no. 7 (2008). doi:10.5210/fm.v13i7.2123.

- Jean-Pierre Bodjoko, S.J. ‘Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb: Identity Crisis, Racism, conflict’. 2023. https://www.laciviltacattolica.com/sub-saharan-africa-and-the-maghreb/.

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Kettani, R. ‘Assigning a Rigid National Identity-Is Morocco Arab or African?’. 2022. https://www.thegazelle.org/issue/237/arab-and-african-morocco.

- King, S.J. ‘Ending Denial: Anti-Black Racism in Morocco.’ Arab Reform Initiative (2020). https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/ending-denial-anti-black-racism-in-morocco/.

- Kuryla, P. ‘Pan-Africanism’. Encyclopedia Britannica. July 11, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pan-Africanism (accessed August 19, 2023).

- Mbembe, A. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Messner, M. ‘Sports and Male Domination: The Female Athlete As Contested Ideological Terrain’. in Women, Sport, and Culture, ed. S. Birrell and C. L. Cole, 65–80. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1994.

- Mhiripiri, J.T., and N.A. Mhiripiri. ‘Imploding or Perpetuating African Myths Through Reporting South Africa 2010 World Cup Stories on Economic Opportunity’. in African Football, Identity Politics and Global Media Narratives, ed. T. Chari and NA Mhiripiri, 180–204. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014.

- Mhiripiri, N.A., and K. Tomaselli. ‘Language Ambiguities, Cultural Tourism and the #khomani’. in KulturullesErbe und Tourismus: Rituale, Traditionen, Inszenierungen, ed. K. Luger and K. Wohler, 285–296. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag, 2010.

- Mohamed, H.A. ‘Morocco Rejoins the African Union After 33 years’. 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/1/31/morocco-rejoins-the-african-union-after-33-years.

- Moreau, N., M. Roy, A. Wilson, and L. Dualt. ‘“Life Is More Important Than football”: Comparative Analysis of Tweets and Facebook Comments Regarding the Cancellation of the 2015 African Cup of Nations in Morocco’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 56, no. 2 (2021): 252–275. doi:10.1177/1012690219899610.

- Nauright, J. Sport, Cultures and Identities in South Africa. London: Leicester University press, 1997.

- Ncube, L. ‘The Beautiful Game? Football, Power, Identities and Development in Zimbabwe’. Doctoral thesis. South Africa: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, 2014.

- Ncube, L. ‘“Highlander Ithimu Yezwe Lonke!”: Intersections of Highlanders FC Fandom and Ndebele Ethnic Nationalism in Zimbabwe’. Sport in Society 21, no. 9 (2018): 1364–1381. doi:10.1080/17430437.2017.1388788.

- Ncube, L. ‘Intersections of Nativism and Football Fandom in Zimbabwean Online Spaces’. Sport in Society 26, no. 1 (2023): 88–103. doi:10.1080/17430437.2021.1973433.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. ‘The World Cup, Vuvuzelas, Flag-Waving Patriots and the Burden of Building South Africa’. Third World Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2011): 279–293. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.560469.

- Pannenborg, A. Football in Africa: Observations About Political, Financial, Cultural and Religious Influences. Amsterdam: NCDO Publications series Sport and Development, 2010.

- Reisigl, M. ‘The Discourse-Historical Approach’. in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies, ed. John Flowerdew and F. Richardson John, 44–59. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Reisigl, M., and R. Wodak. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Anti- Semitism. London: Routldge, 2001.

- Ruddock, A. Understanding Audiences: Theory and Method. London: Sage, 2001.

- Salmons, J.E. Doing Qualitative Research Online. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2016.

- Scholes, J., and R. Sassower. Religion and Sports in American Culture. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Seleti, Y. ‘Transition to Democracy and the Production of a New National Identity inMozambique’. Critical Arts: A Journal of Media Studies 11, no. 1–2 (1997): 46–62. doi:10.1080/02560049785310061.

- Stark, A. ‘Arab Exceptionalism? Tunisia’s Islamist Movement’. E-International Relations. 2011. https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/6735.

- Tajfel, H., ed. Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. ‘An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict’. in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel, 33–37. Monterey, California: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co, 1979.

- Van Dijk, T.A. Communicating Racism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1987.

- Warshel, Y. ‘So-Called Firsts Scored by the Moroccan “Muslim, Arab, African, Post-colonial” and Amazigh Atlas Lions at the 2022 World Cup Football Games’. The Journal of North African Studies 28, no. 2 (2023): 219–229. doi:10.1080/13629387.2023.2172783.

- Williams, S. ‘Appraising Goffman’. The British Journal of Sociology 37, no. 3 (1986): 348–369. doi:10.2307/590645.

- Wodak, R. The Discourse of Politics in Action: Politics As Usual. 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2011.

- Wodak, R. ‘Critical Discourse Analysis, Discourse-Historical Approach’. in The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction, ed. K. Tracy, C. Ilie, and T. Sandel, 1–14. Chichester: John Willey & Sons, 2015.

- Wodak, R., and T.A. van Dijk, eds. Racism at the Top: Parliamentary Discourses on Ethnic Issues in Six European States. Klagenfurt-Celovec: Drava, 2000.

- Zenenga, P. ‘Visualizing Politics in African Sport: Political and Cultural Constructions in Zimbabwean Soccer’. Soccer & Society 13, no. 2 (2012): 250–263. doi:10.1080/14660970.2012.640505.