ABSTRACT

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, clubs in Big Five leagues enjoyed unstoppable growth in their revenues, largely due to increases in media rights. In contrast, clubs outside the Big Five have much weaker financial capabilities and cannot rely solely on income from media rights, so they use the transfer market to increase their revenues and develop a competitive advantage. In the present study, we examined five Swiss Super League clubs’ transfer market strategies from a resource-based perspective to determine the competitive advantages they gain and the importance of transfers to their economic models. Combining data between 2015 and 2020, with semi-structured interviews, we analysed the competitive advantages these clubs developed thanks to the interaction between resources, capability, luck, and market asymmetries. Our results revealed three types of clubs and help fill a research gap, as this issue has barely been addressed in studies on the research-based view or on sports teams.

1. Introduction

According to FIFA’s Global Transfer Report 2021, the number of football player transfers around the world increased from 12,000 in 2012 to 18,068 in 2021. Similarly, the football transfer market grew in value from US$2.66 billion in 2012 to a peak of US$7.35 billion in 2019, before falling back to US$4.86 billion in 2021. This growth in the number and value of player transfers is closely linked to increases in broadcasting rights since the early 2000s, which have been particularly beneficial to Europe’s Big Five leaguesFootnote1 and UEFA’s two European competitions: the Champions League and Europa League.Footnote2 Lucrative broadcasting rights deals have been manna from heaven for Europe’s biggest clubsFootnote3 and leagues, most of which enjoyed continuous revenue growth until the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, TV rights for England’s Premier League, the world’s richest domestic football league, peaked at £1,780 million for the period 2016–2019.Footnote4

Far from the Big Five, Switzerland’s top clubs do not have the same financial resources as Europe’s heavyweights, as the Swiss Super League (henceforth referred to as the Super League) earns just €20 million from TV rights. Consequently, the mean budget of a Super Club is just €23 million, four time less than the mean budget of clubs in France’s Ligue 1 (€110 million euros, DNCG, 2020). Due to the Super League’s low profile, low match attendances (55% mean stadium fill rate between 2003 and 2020Footnote5), and lack of attractiveness, its clubs must seek alternative sources of revenue to survive financially. Indeed, according to UEFA’s 2018 European Club Footballing Landscape, TV rights account for just 9% of Super League clubs’ revenues, the third lowest percentage among the 20 European leagues with aggregate revenues of more than €120 million. In addition to sponsorship/marketing and gate receipts, each of which provides 31% of their budgets, Swiss clubs make extensive use of the transfer market both to obtain much-needed inputs to their budgetsFootnote6 and to strengthen their squads.

The influx of money into European football has boosted the transfer market, but only clubs with large budgets can afford to buy star players: 95 of the 100 most expensive transfers in football history involved Big Five clubs.Footnote7 At the same time, many clubs have begun training and selling young players as a way of generating revenue. FC Basel, for example,Footnote8 bought and sold 41 players in just 8 months in 2022.Footnote9 Because Super League clubs consider their young players, to be their greatest resource, we used the resource-based viewFootnote10 to examine the ways these clubs build a competitive advantage on the transfer market. To this end, we analysed five Super League clubs’ transfer activities between June 2015 and August 2020 and identified the characteristics of each club’s strategy. The results enabled us to draw up a three-part empirical typology of clubs based on their resources and their approaches to the transfer market. This model can be used to categorize other clubs according to their transfer market strategies. Our findings fill a gap in the literature, as no previous study has examined the interactions between resources and sustained competitive advantage in a ‘minor’ football league. Several studies have examined the very close relationship between sporting success, measured by final league position, and a club’s financial power,Footnote11 including in minor leagues such as NorwayFootnote12 and Sweden.Footnote13 These studies hypothesized that differences in revenue reflect differences in clubs’ abilities to attract talented players, as transfers involve a bidding process in which the salary offered is an important factor in persuading players to sign. Sporting results, such as final league position, are linked to a club’s ability to attract players, in other words, to the club’s resources.

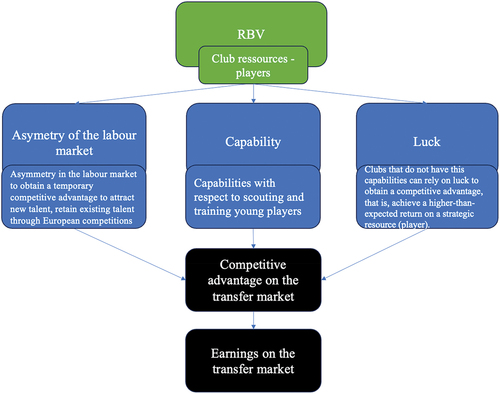

We considered possible ways in which clubs could use their resources (players) or capabilities to create a competitive advantage on the transfer market. The structure of European club football, with the top club(s) in each country’s league qualifying for European competitions can give a club a sustained or temporary competitive advantage.Footnote14 Finally, luck can be an important factor, as it can result in a club achieving a higher-than-expected return on a strategic resource (player).Footnote15

2. Literature review

Europe’s professional football clubs’ business models have changed radically since the 1980s and the liberalization of the transfer market.Footnote16 Andreff and StaudoharFootnote17 described two models of clubs’ finances. Spectators-Subsidies-Sponsors-Local (SSSL) was the preponderant model between 1960 and 1995, when the Media-Merchandising-Magnates-Market-Global (MMMMG) model emerged to address the inadequate profits associated with the SSSL model, under which clubs spent more than they earned. However, the MMMG model applies only to clubs in Europe’s biggest leagues. Clubs in more modest leagues, such as the Super League, still follow the SSSL model, although the model followed differs slightly between leagues.

Swiss clubs’ sources of revenues do not differ entirely from those in other European leagues, with the biggest difference being that Swiss clubs receive negligible sums in TV rights compared with clubs in the Big Five leagues.Footnote18 For example, the Super League’s TV rights contract for 2017–2021 was worth just €26.5 million per year, a far cry from the £1.7 billion the Premier League earned from TV rights for the period 2016–2019. This lack of substantial revenues from TV rights has led Swiss clubs to develop other income-generating strategies, notably international transfers. Thus, Swiss clubs have added another letter – T for transfers – to the SSSL model. Players, according to their performances and skills, are future financial resources for clubs, controlled by clubs through their contracts and whose internal financial value increases as their performances increase.Footnote19 Consequently, ‘resources determine success’,Footnote20 with both expenditure on salaries and revenues from TV rights correlating strongly with supporting success.Footnote21 Revenues are a driver of sporting success because clubs with larger revenues can offer higher higher salaries and thereby attract better players.Footnote22 Szymanski even maintains that the transfer system is a barrier preventing new clubs entering the dominant group (the best clubs). Nevertheless, elite clubs’ performances depend, to a certain extent, on lower-level clubs. Although the best clubs have the greatest financial capacities, they depend on smaller clubs, which act as nurseries for talent, and every club contributes, in one way or another, to identifying new talents.Footnote23

The present study focused on this final point, particularly the competitive advantage Swiss professional clubs develop on the transfer market. Competitive advantage arises from a firm’s ability to use internal resources to implement a different value-creation strategy to the strategies used by its competitors.Footnote24 A sustained competitive advantage is a competitive advantage that competitors cannot copy or imitate.Footnote25 For Swiss clubs to grow, they must be able to make a profit on the transfer market.

2.1. Resource theory

As BarneyFootnote26 noted, much of the research conducted in the field of strategic management since the 1960s has been structured round a single organizational framework,Footnote27 according to which firms develop sustained competitive advantages by implementing strategies that exploit their internal strengths and enable them to respond to opportunities in their environment while neutralizing external threats and avoiding internal weaknesses. Until the 1990s, most research on sources of sustained competitive advantages focused either on isolating a firm’s opportunities and threats,Footnote28 or determining how firms choose strategies that match their strengths and weaknesses to opportunities and threats.Footnote29 BarneyFootnote30 built on this research to develop the VRIN model according to which a firm will obtain a sustained competitive advantage from a resource only if the resource fulfils four conditions:

V = It must be valuable, that is, it must enable a firm to exploit opportunities and/or neutralize threats.

R: It must be rare among a firm’s current and potential competitors. The rarer a resource, the more strategic it is.Footnote31

I: It must be imperfectly imitable, so competitors cannot design and/or implement equivalent strategies.

N: It must be non-substitutable, in that ‘there must be no strategically equivalent resources that are themselves either not rare or imitable’.Footnote32

Hence, a resource will give a sustained competitive advantage only if it is rare. If two or more firms possess strategic resources of similar value, these resources will not necessarily allow them to develop a competitive advantage, but they will prevent them being at a disadvantage.Footnote33 To develop a competitive advantage, a football club must be better at selecting resources (players). In other words, it must be better than its competitors (mainly other Swiss clubs and clubs in other countries) at consistently predicting the future value of resources.Footnote34 Indeed, football clubs operate in an intensely competitive environment with large numbers of clubs competing in the now-global market for playing talent.Footnote35 Firms with greater resource-selection capabilities use these capabilities to differentiate between winning resources and losing resources, so they can invest in the former and avoid the latter.Footnote36

2.2. Capability or luck? Ways of developing a sustained competitive advantage

A capability is a special type of resource whose goal is to improve the productivity of a firm’s other resources. Capabilities are firm-specific, non-transferable, and integrated into the organization, so they ‘cannot easily be bought; they must be built’.Footnote37 In contrast to other types of resources, capabilities are integral parts of a firm’s organization and processes, so they are difficult to transfer from one firm to another without also transferring the firm or a reasonably autonomous subunit of the firm.Footnote38 Teece et al. summarized this characteristic as follows: ‘That which is distinctive cannot be bought and sold short of buying the firm itself, or one or more of its subunits’.Footnote39 In addition, a firm’s capabilities will generate economic benefits only if the firm can acquire resources whose productivity will be improved by its capabilities.Footnote40 The capability to improve its resources’ (players) productivity enables some football clubs to make a profit on the transfer market and generate revenues from player transfers.

Clubs that do not have this capability can rely on luck to obtain a competitive advantage. That is, achieve a higher-than-expected return on a strategic resource (player). A return that is higher than expected is, by definition, the result of luck, rather than the club’s ability to accurately predict a player’s future value.Footnote41 The better a club’s ability to predict a player’s future return, the less chance there is that luck will play a role in obtaining a higher-than-normal return.Footnote42 Luck can also play a role when a club does not have precise expectations concerning a strategic resource’s final value.Footnote43 Although BarneyFootnote44 suggested that Ricardian rent could result from ‘good fortune’ on the strategic factors market, dynamic capabilities theory refutes the idea that luck can be a source of Schumpeterian rent.Footnote45 In other words, clubs without the necessary capabilities may obtain a ‘windfall’ on the transfer market thanks to luck, but they will obtain a sustained competitive advantage only if they are able to repeat these windfalls.Footnote46

Based on this observation, our aim was to determine the extent to which Super League clubs have developed their capabilities with respect to scouting and training young players. Players trained ‘in-house’ are a club’s main resource, not only in terms of the transfer market, but also because resources developed internally can improve team identification and thereby promote team learning and performance.Footnote47 Although all football clubs have these resources, we wanted to determine how clubs in a minor league such as the Super League turn them into a competitive advantage via the transfer market. To this end, we assessed whether each club has the scouting and training capabilities needed to set itself apart from its competitors and develop a competitive advantage on the transfer market. We also took into account the impact of luck in the case of clubs that do not have these capabilities.

2.3. Asymmetry of the labour market

Some firms are able to profit from asymmetry in the labour market to obtain a temporary competitive advantage because this asymmetry enables them to attract new talent, retain existing talent at lower cost, and motivate employees.Footnote48 For example, winning promotion to a higher division or qualifying for a European competition gives clubs an advantage on the strategic factors market that they can use for ‘attracting, retaining, and motivating employees with valuable human capital at an economic discount relative to competitors’.Footnote49 However, qualifying for European competitions provides only a temporary advantage unless qualification occurs repeatedly.Footnote50 To access these strategic segments, players must show their productivity (skill). As Coff and Kryscynski noted, the non-financial dimensions of satisfaction are important to employees and can lead them to stay with a firm even if they could earn a higher salary elsewhere. Consequently, qualifying for European competitions can provide a sustained competitive advantage by motivating players to stay with the club so they can demonstrate their skill on the European stage.

3. Methodology and data collection

In line with the model shown below (), we first focused on clubs’ resources (players) and then examined the competitive advantages clubs can develop by drawing on market asymmetry (qualifying for European competitions), their scouting capabilities, and luck.

We used the Transfermarkt website to compile data on Super League clubs’ player transfers (sales and purchases) between June 2015 and August 2020. Although there are 12 teams in the Super League, we restricted our analyses to just five clubs that reflect the diversity of financial resources and local potential (size of the local population) within the league.Footnote51 To ensure continuity within our dataset, we also chose clubs that played in the Super League for at least four of the five seasons covered by our study period. The five clubs in our sample were FC Basel, BSC Young Boys, FC Luzern, FC Thun, and FC Sion. We determined the revenue each club obtained from transfers during each of the five seasons in our study period by subtracting the amount it spent on players from the amount it earned from selling players. We then compared this revenue with the club’s budget for the season to determine the proportion of its total revenue it obtained from player transfers. Although transfers can include loans, incorporating players from a club’s academy, and signing players without a contract (free agents), we included only players bought and sold (see for the number of players).

Table 1. Transfers negotiated by super league clubs between 2015 and 2020.

Because the proportion of total revenue obtained from player transfers depends on a club’s transfer market strategy and its competitive advantages, we next analysed these aspects for each of the five clubs. Our main objective was to understand how clubs choose and apply their transfer strategies and the extent to which they focus on training young players. We collected information on these subjects via semi-structured interviews (mean length = 30 minutes) with the clubs’ sporting directors and scouting directors, following an interview guide covering six key points: 1. Overall recruitment and transfer vision (specific strategy/preferred channels); 2. Decision-making when buying/selling; 3. Importance of young players to the club; 4. Professionalization of coaching staff; 5. Partnerships – clubs/agents; and 6. Transfer budget and whether the club qualifies for European competitions.

We also obtained information from the Swiss football league, newspaper articles, and interviews with experts and players. This information enabled us to determine whether a club had obtained a competitive advantage from its transfer-market activities. We began by putting the data in chronological order so we could identify common models and themes, focusing on a club’s training policy and the sporting and commercial reasons underlying its transfer-market activity. We also collected data on each club’s capabilities in terms of scouting for players.

4. Results

shows the amounts each club spent buying players and the amounts it earned from selling players during the five seasons from 2015/16 to 2019/20.

4.1. Transfers completed by Super League clubs between 2015 and 2020

Of the five clubs in our sample, FC Basel had the highest net income from player transfers.Footnote52 It was also the club that spent the most on players and earned the most from selling players. BSC Young Boys was in second place, just ahead of FC Sion, whose net income and sales and purchase figures were close to the means for the five clubs. FC Luzern and FC Thun had the lowest net incomes from player transfers, but they had the highest net incomes as a percentage of sales. Swiss clubs’ relatively low revenues and limited financial power mean they are unable to buy star players, so they must look for alternative sources of players (e.g. loans, free transfers) to strengthen their squads. Training centres are another important resource, as they are a source of young players who can be integrated into the club’s first team or sold to obtain revenue from transfer fees. The amounts Swiss clubs earn from selling players have increased steadily over the years and are consistently higher than the amounts they spend on buying players.

Given the importance of transfers to Swiss clubs’ business models, all five clubs try to uncover (rare) resources and obtain the greatest benefit from the resources in their possession. Thanks to their success in national competitions and regular qualifications for European competitions, Switzerland’s leading clubs (FC Basel and Young Boys) have no difficulty attracting either the country’s best young players or players from abroad. Qualifying for Europe also allows them to showcase their players. The substantial revenues they earn from player transfers allow them to invest in finding and developing new rare resources. An alternative, notably for clubs with fewer financial resources, is to develop the managerial and scouting capabilities to uncover rare resources at low cost. Szymanski,Footnote53 who studied English football during the 1970s and 1980s, identified factors other than financial power that impact sporting performance. These factors were a club’s management (Liverpool) and having an especially talented coach (Nottingham Forest). These two factors have been identified in Norway’s championship.Footnote54 Finally, all clubs may benefit from luck, even if they don’t have specific capabilities or enjoy the market asymmetry provided by playing in European competitions.

4.2. Types of clubs

We categorized the five clubs according to their performances on the transfer market between 2015 and 2020. Results revealed three types of clubs, each with distinctive capabilities and resources. A club’s position in the typology also depended on its ability to benefit from market asymmetries and on the percentage contribution of transfer revenues to its total budget.

4.2.1. Type 1: Asymmetry of the labour market and one capability – FC Basel/BSC Young Boys

FC Basel, which won the Super League eight times between 2010 and 2017, has used its domination of Swiss football to make some lucrative sales. Its numerous participations in European competitions allowed the club to showcase its players’ skills beyond Switzerland’s borders. This competitive advantage has helped FC Basel to stand out from its Swiss competitors and become Switzerland’s flagship football club.Footnote55 It has used this leading position to implement a transfer market strategy centred round recruiting young talents between the ages of 17 and 23 and using local players as far as possible, only resorting to international transfers (buying players) when there is no internal alternative and when the international player is clearly a high-level prospect with the potential to improve and later play in one of the Big Five European leagues.Footnote56

Like FC Basel, Young Boys (Champion three times between 2018 and 2020) has gained a competitive advantage by qualifying for the Champions League (2018/19) and Europa League (2019/20) group phases, which enabled the club to make some very profitable sales: It’s clear the European cup plays a role in our budget, and it’s very important. One, for the money you get from qualifying, the receipts, and, two, for the visibility, the international matches. And it’s sometimes that which makes the difference. Sporting directors from big clubs come to watch these matches, they’re kind of reference matches … the opposing team might confirm a transfer. That can make the difference.Footnote57

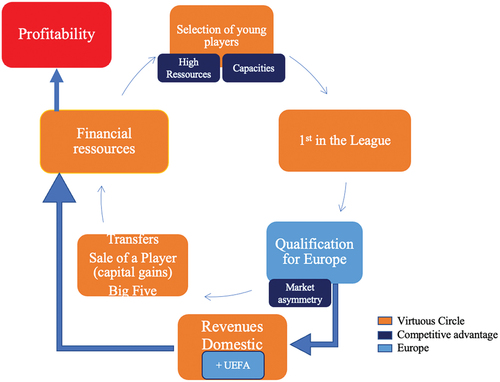

Both clubs benefit greatly from the sustained competitive advantage provided by qualifying for European competitions, which brings in additional direct income and makes their players more attractive. ‘Outside the Big Five, there’s a great imbalance between revenues generated at home and the sums earned from UEFA, especially for taking part in the Champions League’.Footnote58 Indeed, Swiss clubs that qualify for the Champions League group phase earn almost €15 million from the competition. Young Boys’ recent league titles and subsequent qualification for European competitions have allowed it to more than double its budget from €31 million to €82 million, so it now has the resources to buy both Swiss and foreign players like FC Basel. Hence, winning the Swiss championship and qualifying for Europe have triggered a virtuous circle for both clubs: Domestic success leads to opportunities to showcase players across Europe and thereby obtain more resources the club can invest to ensure its continued success. This virtuous circle is in line with the previously noted correlation between a club’s financial strength and its league position. Clubs in this situation may invest their extra resources in improving the club’s structure, buying new players (who are attracted by the clubs’ success), and developing its training capabilities with the aim of producing skilled young players (resources) to incorporate in the first team or to sell at a profit.

In the first instance, European competitions allowed both clubs to show off their players’ skills and thereby increase their value on the transfer market. For example, qualifying for the Champions League round of 16 increased the market value of FC Basel’s star striker B. Embolo from €4 million in December 2014 to €8 million in April 2015, and playing in the Champions League group phase in 2016/2017 allowed the club to sell M. Akanji for over €21 million (bought €5 million). Similarly, after playing in the Champions League group phase in 2018/2019 BSC Young Boys sold K. Mbabu for €9.2 million (bought for €120,000) and D. Sow for €14 million, 14 times his market value when he arrived at the club in 2017.Footnote59 The mean value of the players sold by Young Boys has increased from €1.6 million to almost €6.2 million since its recent qualifications for European competitions. During our study period, FC Basel earned an average of €28.5 million per season by selling an average of 4.6 players. This sum represents one-third of the club’s annual budget of €87 million. It spent an average of €10 million per season (11.5% of its budget) buying an average of 5.2 players.

Revenue from selling players is also a major component of Young Boys’ business model. Young Boys earned an average of €13.6 million per season by selling an average of 2.8 players. Thus, player sales provided 21% of the club’s €56 million mean budget. The club spent an average of €6 million per season (12% of its budget) buying an average of 3.8 players. shows the importance of European competitions for these two clubs. Even when these clubs did not win the Swiss championship, their past European performances and the visibility provided by these competitions enabled them to make excellent sales.

Table 2. European competitions and their importance to clubs’ financial and sporting performance.

Second, qualifying for European competitions has enabled these clubs to develop both their scouting capabilities and their training programmes for young players. In this area, FC Basel has the largest recruitment department with no fewer than eight scouts, who ‘cover all of Swiss football as well as foreign markets’. The club has close partnerships with other clubs in the Basel region and with CASLA football club in Argentina: ‘Our partnership with CASLA gives us a foot in the South American market, especially Uruguay and Argentina, and allows us to attract very young players who would otherwise fall through the net’. In addition, the club ‘has informal partnerships with other major European clubs’.Footnote60 FC Basel’s ability to cover all of Switzerland and its international partnerships give it advantages over its Swiss competitors in terms of uncovering strategic resources. Nevertheless, 7 of the 23 players FC Basel sold between 2015 and 2020 had come through the club’s training centre (total value of €52 million).

Once again, Young Boys is slightly behind FC Basel, especially in the number of scouts it employs: It’s too expensive to have people to do that full time, so I’m full time and I’ve got two or three people at 20, 30, 40%. The budget for this remains limited. Swiss clubs are also highly restricted in terms of expenditure. Our biggest transfer is perhaps 2 million.Footnote61

FC Basel has allocated more resources than any other Swiss club to its training centre, which provides professional training (specialist coaches, mental coaches, physical trainers) to players from a very young age (U12). The club’s success in domestic competitions also gives it a competitive advantage by enabling it to retain its best players and attract young players from other Swiss clubs (e.g. M. Akanji, bought from second division clubs for less than €1 million). With a wider field of operations and total coverage of Swiss football, the club can acquire valuable, rare, and inimitable resources that give it both sporting and financial advantages. Like FC Basel, Young Boys first turns to young players from its training centre: ‘If we’re looking for a player, we always start by looking at our youngsters … If we don’t have [the player we need], we look abroad for a player with the profile we’re after’.Footnote62 The club’s main source of players is its local area (Bern and Fribourg cantons), where it has deep roots and informal partnerships with the region’s other clubs. Four of the thirteen players Young Boys transferred for a fee between 2015 and 2020 were trained at the club.

4.2.2. Type 2: Luck – FC Sion

Having played in European competitions just once – the Europa League group stage in 2015/2016 — FC Sion has not been able to use market asymmetry to gain a notable competitive advantage. Nor does it have strong internal capabilities with respect to talent spotting. Consequently, it has had to find a different way to make a profit on the transfer market. As noted above, organizations can rely on luck to obtain a higher-than-expected transfer fee for a player. This is the case for FC Sion, whose transfer strategy is centred round developing internal resources, that is young players recruited mostly from the surrounding canton: The goal is to have young players that we have trained and, if possible, to bring in promising young players from abroad to play for us and who we can later sell … Sion is a club that takes on a lot of youngsters we can train and sell.Footnote63 During our study period, FC Sion sold an average of 2.4 players per season, earning €9 million, which is almost half the club’s budget of €18.5 million. During the same period, the club spent an average of €3.3 million (18% of its budget) per season on new players, buying an average of 2.2 players.

With its sporting director as its only scout, FC Sion has very limited transfer-market capabilities. Although the club still manages to buy players, it is aware that this is ‘something we must develop’. When it comes to investing in new players, the club currently relies on agents presenting players to the club’s president ‘who makes the final decision and who can sniff out a good player’.Footnote64 FC Sion also has expertise in training young players, largely thanks to its experience in elite football, even if its training facilities are not of the same quality as those of Switzerland’s other leading clubs. According to the club’s president, the club needs ‘to invest 30 million to have a training centre worthy of the name’.Footnote65 Nevertheless, 5 of the 12 players the club sold between 2015 and 2020 had come through its training centre. Thus, even though it lacks a sustained competitive advantage from qualifying regularly for European competitions and has limited transfer-market capabilities, FC Sion manages to achieve very positive results in terms of sales (see ). Its main resource in this respect is the pool of players available in its home canton, where FC Sion is the leading club and therefore attractive to the area’s young hopefuls.

4.2.3. Type 3: Local expertise based on stability – FC Thun and FC Luzern

Between 2015 and 2020, FC Thun and FC Luzern obtained approximately 12% of their budgets from selling players. FC Thun, whose mean budget was €11.5 million, earned an average of €1.3 million per season by selling an average of six players, while spending just €95,000 per season buying an average of 0.8 players. FC Luzern, whose mean budget was €21.3 million, earned an average of €2.7 million per season by selling an average of eight players and spent €620,000 per season buying an average of 1.4 players.

FC Thun and FC Luzern have similar transfer market strategies, based mostly on training young players. At FC Thun: ‘Training our own players so we can bring them through to the first team is our main objective … but we also recruit young players that we can train and sell. That’s our basic strategy’.Footnote66 At FC Luzern: ‘Every year we bring up four or five players from our youth squad to the first team. That’s definitely our main objective: To have a healthy foundation in our youth squad so we can work with and properly prepare players’.Footnote67 Thus, both clubs focus on developing their main resource (young players) through their training centres, as the following quotes show. At FC Thun: ‘What we want is to have a player we recruited from a lower division who we can sell on at a profit, or to have players who move up a level with us and that we can sell’.Footnote68 Similarly for FC Luzern: ‘We tend to invest and to bring quite young players into the team, with the aim of one day making a profit on a future transfer. There are financial advantages to training youngsters and bringing them up to a higher level’.Footnote69

The two clubs also have similar capabilities with respect to transfers. Both clubs have a sporting director plus either a part-time employee (20% of full time, FC Thun) or a full-time employee (FC Luzern). In addition, both clubs have informal partnerships within Switzerland. FC Thun has a basic collaboration with Young Boys because we are so close to Bern and because they currently have a sporting director who thinks like us … we work together when it comes to the next generation, and there are players who come out of the U18s to us.Footnote70 FC Luzern has informal partnerships with clubs in Switzerland’s second division. However, despite their desire to sell players from their training centres, only two of the eight players FC Luzern sold were trained by the club, and none of the six players FC Thun sold had come through its training centre. This difference reflects the number of players from its training centre each club brought into its first team. FC Luzern fielded 19 players from its training centre between 2016 (the year in which the Swiss Football League set up its ‘Promoting the Next Generation’ training concept) and 2020, and these players made a total of 304 appearances. FC Thun, on the other hand, fielded only 10 players from its training centre, and these players made a total of just 159 appearances.Footnote71 The lower figures for FC Thun are mostly due to the club being relegated to the second division for the 2019–2020 season, which made it more difficult for it to give young players a chance: ‘Basically, either you play to win the league, or you fight to avoid relegation. It’s very difficult to include young players in your first team in this context’. Footnote72

5. Discussion

5.1. Resources and capabilities

The present study examined the hypothesis that football clubs’ transfer market strategies depend on resources developed internally, competitive advantages obtained through market asymmetries, and a club’s capabilities. Results supported the hypothesis that clubs create value by combining resources developed internally with resources acquired through the market.

Strengthening its team with external resources (i.e. by acquiring new players) gives a club both more choice for selecting complementary resources and the ability to increase its overall level of resources by acquiring specific competencies.Footnote73 Indeed, the clubs in our sample with the greatest financial resources (largest budgets) were able to buy more talented players and thereby frequently won the Super League and qualified for European competitions. However, our results support Agdebesan’s hypothesis that existing internal resources must be complemented by external resources bought on the market, first to obtain missing resources and then to uncover a rare resource (and subsequently make a profit by reselling it).Footnote74 Hence, there is a clear compromise between developing resources internally and buying external resources when possible.Footnote75

Recent studies on the importance of combining resources developed internally with those acquired externally show that organizations that rely excessively on internal resources may do so because of financial constraints.Footnote76 In the case of football, clubs with limited financial resources and no sustained competitive advantage cannot buy star players and must therefore train their own players. The importance of being able to do so is highlighted by the strong correlation between a club’s sporting success, measured by its league position, and its financial strength, measured by its expenditure on players’ salaries, which explained up to 92% of the variance in Premier League clubs’ final league positions over the last 20 years.Footnote77 Studies of Norwegian and Swedish football clubs have found similar correlations.Footnote78,Footnote79

Nevertheless, our analysis shows that if clubs with few financial resources wish to make a profit on the transfer market and obtain VRIN resources, they must invest in developing players internally and in finding players with the potential to improve. Developing resources internally and deploying them effectively is also a way for clubs to build good teams.Footnote80

Players are a club’s main asset. Although possessing strategic resources (players) gives clubs a sustained competitive advantage,Footnote81 these resources are rare and take time to create/find. In fact, certain clubs’ (FC Basel, BSC Young Boys) capabilities in acquiring strategic resources give them a competitive advantage over other clubs. Secondly, skill in selecting resources is extremely important because it allows a club to assess more accurately than its competitors the value of resources present on the market.Footnote82 Consequently, clubs with the greatest market coverage and the greatest resource-selection capabilities have a sustained competitive advantage. A manager’s ability to understand resources and use them to create value is itself a resource.Footnote83

Empirically, we attempted to show how clubs approach the transfer market and how they build their strategies. The results of our resource-based study support the hypothesis that organizations (clubs) create value by combining resources developed internally with complementary resources acquired on the market.Footnote84 The resource-based view explains differences in performance in terms of differences in resources within a given industry.Footnote85 However, it raises the question of how firms use resources to create value and thereby obtain a competitive advantage that may allow them to improve their performance.Footnote86 That said, the interaction between resources, capabilities, luck, and obtaining a competitive advantage thanks to market asymmetries has almost never been investigated from a resource-based perspective.Footnote87

5.2. Do clubs’ strategies vary according to the competitive advantages gained?

The present empirical study showed that sporting and economic considerations are often compatible, as actions and events that improve sporting performance often improve financial performance and vice versa. In other words, there is a causal relationship between the two variables in that good sporting performances lead to financial rewards.Footnote88

Super League clubs’ main sources of income are matchday revenues and sponsorship (combined with public relations). Each club also receives a share of the Super League’s TV rights and marketing revenues, with only a relatively small difference between the sums paid to the league champion (€4 million) and the bottom-placed club (€2 million). Consequently, income from player transfers is an important part of all Super League clubs’ economic models. All the teams in the league have adopted a transfer-market strategy based on training young players in the hope of selling them at a profit, but there are differences between clubs in how they implement this strategy.

FC Basel has used its long-standing dominance of Swiss football to create a virtuous circle that enables it to win the championship, or at least qualify for a European competition, nearly every year. Its status as Switzerland’s leading club has allowed it to establish itself as a launch pad for players wishing to join a major European club. Year after year, Basel has developed its capabilities while achieving long-term success in developing its strategic resources (players). BSC Young Boys’ recent success has allowed it to create a similar virtuous circle. Its excellent performances in the Super League, crowned by four consecutive league titles between 2018 and 2021, have resulted in the club regularly qualifying for European competitions and led to some highly profitable sales to bigger European clubs. Hence, both clubs have used their appearances in Europe to develop a temporary competitive advantage, especially in financial terms, through the income received from competing in European competitions and through the opportunity to showcase their players during European matches as shown in below.

Figure 2. The virtuous circle for clubs that compete regularly in European competitions (adapted from Baroncelli and Lago, Citation2006).

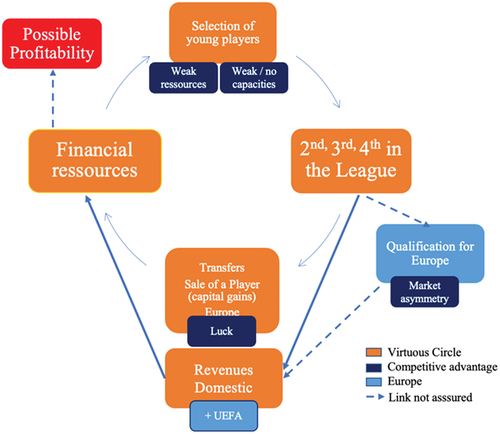

Due to their small budgets, the other Super League clubs have very limited capabilities on the transfer market. Moreover, their activities are restricted to local or low-cost resources (e.g. players from lower divisions), as they do not have the financial and human resources needed to attract, invest in, or scout for strategic resources outside their local areas. Most of these clubs have just one person – their sporting director – to scout for new players.

Clubs that occasionally qualify for a European competition earn larger sums from player transfers, and these sums account for a larger percentage of their total budgets. However, these rare European appearances do not allow them to create similar virtuous circles to those created by FC Basel and Young Boys, and the beneficial effects of market asymmetry are short lived. For example, clubs receive a share of the revenues redistributed by UEFA only during the season they play in a European competition. Nevertheless, luck may enable these clubs to sign lucrative transfer deals, as anyone can be lucky in the market, regardless of their resources, capabilities, or competitive advantage.

Clubs that never qualify for European competitions have very small budgets and therefore follow a strategy of recruiting young players locally and training them so they can play in the first team or be sold to supplement the club’s income. This strategy produces the virtuous circle shown in . Such clubs can change type at any time should they obtain a temporary competitive advantage by qualifying for a European competition or by developing the capability to acquire strategic resources from a wider range of sources. Luck, in the form of making an unexpected capital gain or a higher-than-expected transfer fee, can also enable these clubs to change type.

Figure 3. The virtuous circle for clubs that compete occasionally in European competitions (adapted from Baroncelli and Lago, Citation2006).

From a managerial point of view, these virtuous circles show that all Super League clubs have adopted a transfer strategy based on training young players recruited in Switzerland, often within a club’s local area. In fact, Super League clubs always prioritize local players over foreign players, both when looking for youngsters they can train and when recruiting seasoned players for their first teams. This strategy is in line with the Swiss football federation’s policy of ‘protecting’ Swiss players with the aim of improving the national side and developing Swiss football in general. For example, a federation rule limits the number of non-locally trained players a Super League club can include in its squad. Originally set at 17, the restriction was tightened to 13 non-locally trained players at the beginning of the 2023–2024 season, thereby increasing the need for clubs to uncover and train talented local players. One way they do this is by developing informal relationships with their competitors.

From a macroeconomic point of view, there is a division of implicit and informal roles in which some clubs (e.g. FC Luzern, FC Thun) can be categorized as training clubs that primarily try to sell their players to other Swiss clubs that play in Europe and have greater financial resources (e.g. FC Basel, Young Boys). This trade enables richer clubs to strengthen their squads with locally trained players while redistributing some of their European earnings to other Swiss clubs. Playing in Europe also provides the richer clubs with opportunities to showcase their players and then sell them to Europe’s bigger clubs. Finally, other clubs adopt a more opportunistic outlook and sell players when they receive suitable offers.

Although clubs have no formal obligations regarding transfer practices, they have spontaneously formed loose partnerships within the Super League that benefit all the clubs in terms of resources, training, and finances. Indeed, the only way for smaller clubs to benefit from the revenues the larger clubs earn from competing in European competitions is for the smaller clubs to sell their best players to the larger clubs. Although the Swiss Football League redistributes funds to clubs that field local players, the amounts are much smaller than the sums UEFA redistributes to clubs that play in its European competitions. In line with the Swiss league’s action, one way in which UEFA could help Europe’s smaller clubs would be to redistribute revenues to clubs that field locally trained players and to the club that trained the player, even if that club did not qualify to play in a European competition.

6. Conclusion, limitations and future research perspectives

6.1. Contribution

The present study addressed a gap in the literature by examining how Swiss football clubs use their resources and capabilities to develop competitive advantage. Its main contribution is to identify situations in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, that is, when the interaction between resources and value-creating capabilities creates a competitive advantage for sports clubs.

The extent to which clubs can develop such an advantage depends on their resources, their capabilities, and their ability to benefit from market asymmetries. It would be interesting to conduct similar studies in other leagues to determine whether our findings also apply to richer clubs. Despite our study’s limits, its results confirm that qualifying for European competitions over several seasons gives clubs a competitive advantage they can use to extend their capability for selecting VRIN resources (players) and thereby create a virtuous circle based on showcasing these resources in European competitions and selling them for a profit. The interactions between resources and capabilities not only determine a team’s performance; they also result in complementary valuable resources being available on the market. However, some clubs do not have sufficient financial resources to invest in the market.

Our results highlight three important points. First, to make a profit on the transfer market, clubs must obtain and develop high-quality resources. Even if a club is not successful on the pitch, a good player will attract attention, at least locally, and increase in value. Second, clubs with better resource-selection capabilities and the ability to cover the whole market can develop a sustained competitive advantage that allows them to uncover rare resources. Third, to be able to invest in the first two points, clubs must create a virtuous circle centred round domestic success and competing in Europe. Clubs that do not have sufficient resources and capabilities can, in some cases, rely on luck and their manager’s expertise to recruit rare resources and make capital gains on their resale. Finally, the only resources some clubs can use to seek a sustained advantage over other clubs are players trained ‘in-house’, as their ability to seek VRIN resources is restricted to their local area.

From a managerial point of view, the objective of clubs who use domestic success and participation in European competitions to create a virtuous circle is to remain in this circle. Thus, their managers’ and decision-makers’ main role is to continue finding rare resources, so they can replace the players they sell with new players of at least similar quality and make other sales in the future. This is why a club’s scouting capability is so important and requires investment. Even if a club lacks VRIN resources for one or two seasons, its managers can look for rare resources elsewhere to make up for this internal lack. In contrast to leading clubs, other clubs must focus on their training centres and rely on their managers’ expertise and experience to create value from players available internally and thereby improve the team’s performance.Footnote89

To compensate for the huge differences between leading clubs and other clubs, the league could encourage them to enter more formal partnerships aimed at facilitating exchanges of resources. For example, inter-club loans would give young players opportunities to hone their skills in a different environment. The league could also introduce financial bonuses (in addition to the training fees provided by UEFA) for Swiss clubs that train players who are later sold by other Swiss clubs.

6.2. Limits and perspectives

Our study has several limits. First, we based our analyses on just five clubs, so care must be taken when generalizing our results. Second, although we adopted the Resource-Based View, our analyses of clubs’ transactions did not consider players as assets for their club. In other words, we calculated the profit each club made from player transfers by simply subtracting the amount it spent buying players from the amount it earned from selling players. These calculations did not include depreciation due to the length of players’ contracts or costs relating to training and salaries, which must be deducted to determine the effective profit made on each sale. Nor did we include transactions relating to player loans, which sometimes involve fees. Finally, we used the raw sale prices listed in official documents without deducting any commissions paid to agents or third parties involved in the transfer. Future studies could address these limitations by considering players as assets and including costs and depreciation to determine the actual profits clubs make from player transfers each season.

NonBigFive football clubs’ strategies for generating transfer revenues_The case of Switzerland’s Super League_Commentsandresponse.docx

Download MS Word (524 B)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2024.2374254

Notes

1. England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

2. UEFA redistributed €2.04 billion to clubs that played in the Champions League during the 2019–2020 season. This sum was approximately €450 million in 2003–2004.

3. Deloitte Football Money League 2010–2020.

4. Football Benchmark, (14 December 2023), TV rights: Behind the premier league’s latest deal, https://www.footballbenchmark.com/library/tv_rights_behind_the_premier_league_latest_deal (accessed December 2023).

5. Swiss Football League.

6. Terrien et al., ‘The win/profit maximization debate: Strategic adaptation as the answer?’

7. Goal.com, (2 September 2023), The 100 most expensive football transfers of all time, https://www.goal.com/en/news/100-most-expensive-football-transfers-all-time/ikr3oojohla51fh9adq3qkwpu (accessed December 2023).

8. LeMatin.ch, (29 August 2023), Le projet trading du FC Bâle plus que jamais d’actualité, https://www.lematin.ch/story/football-le-projet-trading-du-fc-bale-plus-que-jamais-dactualite-451200883206, (accessed December 2023).

9. Watson.ch, (22 February 2022), Rêveur, Degen dirige le FC Bâle comme s’il jouait à la Playstation, https://www.watson.ch/fr/sport/analyse/945550547-david-degen-dirige-le-fc-bale-comme-sur-la-playstation, (accessed December 2023).

10. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

11. Szymanski and Kuypers, ‘Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football’.

12. Kringstad and Olsen, ‘Can sporting success in Norwegian football be predicted from budgeted revenues?’.

13. Madsen et al, ‘Wage expenditures and sporting success: An analysis of Norwegian and Swedish football 2010–2013’.

14. Terrien et al., ‘The win/profit maximization debate: Strategic adaptation as the answer?’.

15. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

16. Drut and Raballand, ‘Football européen et régulation : une question de gouvernance des instances dirigeantes’.

17. Andreff and Staudhar ‘The Evolving European Model of Professional Sports Finance’.

18. Storm and Solberg, ‘European club capitalism and FIFA redistribution models: An analysis of development patterns in globalized football’.

19. Morrow, ‘Scottish Football: It’s a Funny Old Business’.

20. Hall et al., ‘Testing causality between team performance and payroll: The cases of Major League Baseball and English soccer’.

21. Stenheim et al., ‘Broadcasting revenues and sporting success in European football: Evidence from the Big Five leagues’.

22. Kringstad and Olsen, ‘Can sporting success in Norwegian football be predicted from budgeted revenues?’.

23. Prinz and Weimar, ‘The golden generation: The personnel economics of youth recruitment in European professional soccer’.

24. Bar-Eli, ‘Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage: On the strategic similarities between Maccabi Tel Aviv BC and FC Bayern München’.

25. Ibid.

26. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

27. Andrews, The Concept of Corporate Strategy.

28. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.

29. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

30. Ibid.

31. Desreumaux and Warnier, VII. Jay B. Barney – La Resource-Based Theory et les sources de l’avantage concurrentiel soutenable.

32. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

33. Desreumaux and Warnier, VII. Jay B. Barney – La Resource-Based Theory et les sources de l’avantage concurrentiel soutenable.

34. Makadok, ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’.

35. Szymanski, ‘Entry into exit: insolvency in English professional football’.

36. Makadok, ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’.

37. Teece et al., ‘Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management’.

38. Makadok, ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’.

39. Teece et al., ‘Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management’.

40. Makadok, ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’.

41. Barney, ‘Organizational Culture: Can It Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage?’.

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid.

44. Barney, ‘Organizational Culture: Can It Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage?’.

45. Makadok, ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’.

46. Ibid.

47. Van Der Vegt and Bunderson, ‘Learning and Performance in Multidisciplinary Teams: The Importance of Collective Team Identification’.

48. Molloy and Barney, ‘Who Captures the Value Created with Human Capital? A Market-Based View’.

49. Barney et al., ‘Invited Editorial: Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human Capital – Based Competitive Advantages’.

50. Terrien, Orchestration des ressources et efficience des entreprises de spectacle sportif.

51. Mustafi and Bayle, ‘Local potential and strategic models in a small market outside the Big Five: The case of Switzerland’s Super League’.

52. Transfer fees in euros – Transfermarkt. We applied the mean euro-Swiss franc exchange rate between 2015 and 2020 (1 euro = 1.1 CHF) to convert Swiss clubs’ budgets from Swiss francs into euros.

53. Szymanski, ‘The economics of footballing success’.

54. Kringstad and Olsen, ‘Can sporting success in Norwegian football be predicted from budgeted revenues?’.

55. FC Basel earned 58,000 of the 127,000 ranking points UEFA accorded to Swiss clubs between 2015 and 2020, and it was ranked Europe’s 25th best club between 2012 and 2022.

56. FC Basel, interview.

57. BSC Young Boys, interview.

58. Menary, ‘One rule for one: The impact of Champions League prize money and Financial Fair Play at the bottom of the European club game’.

59. Market values and transfer fees obtained from Transfermarkt.com.

60. FC Basel, interview.

61. BSC Young Boys, interview.

62. Ibid.

63. FC Sion, interview.

64. Ibid.

65. LeTemps.ch, (23 January 2023), Christian Constantin pose sur la table un projet à 150 millions pour sauver le FC Sion, https://www.letemps.ch/suisse/valais/christian-constantin-pose-table-un-projet-150-millions-sauver-fc-sion (accessed January 2023).

66. FC Thun, interview.

67. FC Luzern, interview.

68. FC Thun, interview.

69. FC Luzern, interview.

70. FC Thun, interview.

71. Swiss Football League report, 2020.

72. Rts.ch, (14 October 2020), Super League: les joueurs formés au club n’ont jamais autant joué, https://www.rts.ch/sport/football/11640267-super-league-les-joueurs-formes-au-club-nont-jamais-autant-joue.html (accessed January 2023).

73. Lechner and Vidar Gudmundsson, ‘Superior value creation in sports teams: Resources and managerial experience’.

74. Adegbesan, ‘On the origins of competitive advantage: Strategic factor markets and heterogeneous resource complementarity’.

75. Lechner and Vidar Gudmundsson, ‘Superior value creation in sports teams: Resources and managerial experience’.

76. Adegbesan, ‘On the origins of competitive advantage: Strategic factor markets and heterogeneous resource complementarity’.

77. Szymanski and Kuypers, ‘Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football’.

78. Madsen et al, ‘Wage expenditures and sporting success: An analysis of Norwegian and Swedish football 2010–2013’.

79. Kringstad and Olsen, ‘Can sporting success in Norwegian football be predicted from budgeted revenues?’.

80. Lechner and Vidar Gudmundsson, ‘Superior value creation in sports teams: Resources and managerial experience’.

81. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’.

82. Desreumaux and Warnier, VII. Jay B. Barney – La Resource-Based Theory et les sources de l’avantage concurrentiel soutenable.

83. Holcomb et al., ‘Making the most of what you have: Managerial ability as a source of resource value creation’.

84. Lechner and Vidar Gudmundsson, ‘Superior value creation in sports teams: Resources and managerial experience’.

85. Peteraf and Barney, ‘Unraveling the resource-based tangle’.

86. Barney, ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’; Newbert, ‘Empirical Research on the Resource-Based View of the Firm: An Assessment and Suggestions for Future Research’; Wernerfelt, ‘A Resource-Based View of the Firm’.

87. Newbert, ‘Empirical Research on the Resource-Based View of the Firm: An Assessment and Suggestions for Future Research’.

88. Carlsson-Wall et al., ‘Performance measurement systems and the enactment of different institutional logics: Insights from a football organization’.

89. Lechner and Vidar Gudmundsson, ‘Superior value creation in sports teams: Resources and managerial experience’.

Bibliography

- Adegbesan, J.A. ‘On the Origins of Competitive Advantage: Strategic Factor Markets and Heterogeneous Resource Complementarity’. Academy of Management Review 34, no. 3 (2009): 463–475. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.40632465

- Andreff, W. ‘‘Le modèle économique du football européen’, in Pôle Sud’. Pôle Sud n° 47, no. 2 (2017): 41–59. doi:10.3917/psud.047.0041

- Andreff, W., and P. Staudohar. ‘The Evolving European Model of Professional Sports Finance’. Journal of Sports Economics 1, no. 3 (2000): 257–276. doi:10.1177/152700250000100304

- Andrews, K.R. ‘The Concept of Corporate Strategy’, in The Concept of Corporate Strategy, ed. McKiernan Peter (Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin, 1996), 18–46.

- Bar-Eli, M., Y. Galily, and A. Israeli. ‘Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage: On the Strategic Similarities Between Maccabi Tel Aviv BC and FC Bayern München’. European Journal for Sport and Society 5, no. 1 (2008): 73–94. doi:10.1080/16138171.2008.11687810

- Barney, J. ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’. Journal of Management 17, no. 1 (1991): 99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barney, J.B. ‘Organizational Culture: Can it Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage?’ The Academy of Management Review 11, no. 3 (1986): 656–665. doi:10.2307/258317

- Barney, J.B., D.J. Ketchen, M. Wright, J.B. Barney, D.J. Ketchen, and M. Wright. ‘The Future of Resource-Based Theory’. Journal of Management 37, no. 5 (2011): 1299–1315. doi:10.1177/0149206310391805

- Barney, J.B., D.J. Ketchen, M. Wright, N.J. Foss, J.B. Barney, D.J. Ketchen, and M. Wright. ‘Invited Editorial: Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human Capital–Based Competitive Advantages’. Journal of Management 37, no. 5 (2011): 1413–1428. doi:10.1177/0149206310397772

- Baroncelli, A., and U. Lago. ‘Italian Football’. Journal of Sports Economics 7, no. 1 (2006): 13–28. doi:10.1177/1527002505282863

- Carlsson-Wall, M., K. Kraus, and M. Messner. ‘Performance Measurement Systems and the Enactment of Different Institutional Logics: Insights from a Football Organization’. Management Accounting Research 32 (2016): 45–61. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2016.01.006

- Desreumaux, A., and V. Warnier, ‘V.I.I. Jay, B. Barney. La Resource-Based Theory et les sources de l’avantage concurrentiel soutenable’, in Les grands auteurs en stratégie. (Caen: EMS Editions, 2020). doi:10.3917/ems.loili.2020.01.0118

- Drut, B., and G. Raballand. ‘Football européen et régulation : une question de gouvernance des instances dirigeantes’. Géoéconomie n° 54, no. 3 (2010): 39–52. doi:10.3917/geoec.054.0039

- Hall, S., S. Szymanski, and A. Zimbalist. ‘Testing Causality Between Team Performance and Payroll the Cases of Major League Baseball and English Soccer’. Journal of Sports Economics 3, no. 2 (2002): 149–168. doi:10.1177/152700250200300204

- Holcomb, T.R., R.M. Holmes Jr., and B.L. Connelly. ‘Making the Most of What You Have: : Managerial Ability As a Source of Resource Value Creation’. Strategic Management Journal 30, no. 5 (2009): 457–485. doi:10.1002/smj.747

- Kringstad, M., and T.-E. Olsen. ‘Can Sporting Success in Norwegian Football Be Predicted from Budgeted Revenues?’ European Sport Management Quarterly 16, no. 1 (2016): 20–37. doi:10.1080/16184742.2015.1061032

- Lechner, C., and S. Vidar Gudmundsson. ‘Superior Value Creation in Sports Teams: Resources and Managerial Experience’. M@n@gement 15, no. 3 (2012): 284–312. doi:10.3917/mana.153.0284

- Madsen, D.Ø., T. Stenheim, S. Boas Hansen, A. Zagheri, B.O. Grønseth, and V. Girginov. ‘Wage Expenditures and Sporting Success: An Analysis of Norwegian and Swedish Football 2010–2013’. Cogent Social Sciences 4, no. 1 (2018): 1457423. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1457423

- Makadok, R. ‘Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation’. Strategic Management Journal 22, no. 5 (2001): 387–401. doi:10.1002/smj.158

- Menary, S. ‘One Rule for One: The Impact of Champions League Prize Money and Financial Fair Play at the Bottom of the European Club Game’. Soccer & Society 17, no. 5 (2015): 666–679. doi:10.1080/14660970.2015.1103073

- Molloy, J., and J. Barney. ‘Who Captures the Value Created with Human Capital? A Market-Based View’. Academy of Management Perspectives 29, no. 3 (2015): 309–325. doi:10.5465/amp.2014.0152

- Morrow, S. ‘Scottish Football: It’s a Funny Old Business’. Critical Social Policy 7, no. 1 (2006): 622–642. doi:10.1177/1527002505282867

- Mustafi, Z., and E. Bayle. ‘Local Potential and Strategic Models in a Small Market Outside the Big Five: The Case of Switzerland’s Super League’’. Soccer & Society 24, no. 6 (2022): 757–777. doi:10.1080/14660970.2022.2126131

- Neri, A., M. Negri, E. Cagno, V. Kumar, and J.A. Garza-Reyes. ‘What Digital-Enabled Dynamic Capabilities Support the Circular Economy? A Multiple Case Study Approach’. Business Strategy and the Environment 32, no. 7 (2023): 5083–5101. doi:10.1002/bse.3409

- Newbert, S. ‘Empirical Research on the Resource-Based View of the Firm: An Assessment and Suggestions for Future Research’. Strategic Management Journal 28, no. 2 (2007): 121–146. doi:10.1002/smj.573

- Peteraf, M.A., and J.B. Barney. ‘Unraveling the Resource-Based tangle’, in Managerial and Decision Economics’. Managerial and Decision Economics 24, no. 4 (2003): 309–323. doi:10.1002/mde.1126

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. (New-York: Free Press, 1985).

- Prinz, J., and D. Weimar. “The Golden Generation: The Personnel Economics of Youth Recruitment in European Professional Soccer’”, in Personnel Economics in Sport, ed. Neil LOngley (Edward Elgar, 2018), 47–72. doi:10.4337/9781786430915

- Stenheim, T., A.G. Henriksen, C.M. Stensager, B.O. Grønseth, and D.Ø. Madsen. ‘Broadcasting Revenues and Sporting Success in European Football: Evidence from the Big Five Leagues’. The Journal of Applied Business and Economics 22, no. 4 (2020): 74–88. doi:10.33423/jabe.v22i4.2909

- Storm, R., and H. Solberg. ‘European Club Capitalism and FIFA Redistribution Models: An Analysis of Development Patterns in Globalized Football’. Sport in Society 21, no. 11 (2018): 1850–1865. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1424136

- Szyamnski, S., and T. Kuypers. ‘Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football’. Journal of Sports Economics 2, no. 4 (2001): 379–381. doi:10.1177/152700250100200406

- Szymanski, S. ‘The Economics of Footballing Success’. Economic Review 10, no. 4 (1993): 14–18.

- Szymanski, S. ‘Entry into Exit: Insolvency in English Professional Football’. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 64, no. 4 (2017): 419–444. doi:10.1111/sjpe.12134

- Teece, D.J., G. Pisano, and A. Shuen. ‘Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management’. Strategic Management Journal 18, no. 7 (1997): 509–533. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509:AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Terrien, M. ‘Orchestration des ressources et efficience des entreprises de spectacle sportif’. Journal of Applied Crystallography 49, no. Pt 3 (2016): 806–813. doi:10.1107/S1600576716004635

- Terrien, M., N. Scelles, S. Morrow, L. Maltese, and C. Durand. ‘The Win/Profit Maximization Debate: Strategic Adaptation As the answer?’, in Sport’. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 7, no. 2 (2017): 121–140. doi:10.1108/SBM-10-2016-0064

- Van Der Vegt, G.S., and J.S. Bunderson. ‘Learning and Performance in Multidisciplinary Teams: The Importance of Collective Team Identification’. Academy of Management Journal 48, no. 3 (2005): 532–547. doi:10.5465/amj.2005.17407918

- Wernerfelt, B. ‘A Resource-Based View of the Firm’. Strategic Management Journal 5, no. 2 (1984): 171–180. doi:10.1002/smj.4250050207