ABSTRACT

‘Founders’ is an intermittent series of short, critical appreciations of scholars, researchers and others whose work and ideas, mainly in Britain, have made particularly sweeping, influential and foundational contributions to the development of historically- and archaeologically-informed landscape studies. This latest addition to the series concerns Christopher Taylor, whose death on 28th May 2021 was noted in the Landscapes editorial in issue 21.2.

An Introduction (Graham Fairclough)

Christopher Taylor died on 28th May 2021. As our former editor Paul Stamper wrote in issue 16:2, when introducing the most recent entry, concerning Oliver Rackham, in this occasional series, the Founders column has often been devoted to people whose impact and death was some years, in one case a century, in the past. Paul and I made an exception for Oliver Rackham, as Paul and his then co-editor David Austin had for Collin Bowen, whose Founders appreciation was written by Chris Taylor at the time of Bowen’s death (issue 11-1, ‘Citation2010’, 84-94). Thus it is with no apology at all that Landscapes offers this joint appreciation of Christopher Taylor’s life and achievements and his influence on the practice of landscape archaeology and landscape history in Britain, if not indeed much further afield. ()

Figure 1. Chris Taylor in the 1960s, surveying at Eggardon, Dorset (Photograph reproduced by permission of the Taylor family).

Taken in its full breadth, his work was a worthy successor—and a necessary corrective—to W.G. Hoskins’ historical approach to the making of the English landscape (Hoskins Citation1955, Citation1988). It was equally a complement to the work of Maurice Beresford, the founder of medieval settlement studies in England (Aston et al. Citation2006), and co-founder and co-director with the archaeologist John Hurst in 1950 of the highly influential long-running Wharram Percy project. Chris’s work stands also squarely in the tradition of historians such as the historical geographer Clifford Darby, and of Herbert Finberg, who Chris once characterised as a member along with Hoskins and Beresford of the Triumvirate that brought ‘a landscape dimension to local history’ (Aston et al. Citation2006, 100), just as Chris himself a little later brought a landscape dimension to archaeology.

To look back only to those that Chris followed, however, risks forgetting all those he worked with, inspired and taught. In a lengthy review article in this journal on the Wharram Percy final publication Chris himself drew attention to the difference between

‘ … what landscape history was, and what it has become over the last 50 years of the twentieth century, from Hoskins’s rather simplistic romanticism in the Making of the English Landscape to the complex, multi-disciplinary professional approach it is today … .. the huge leap from trying to understand single sites to unravelling entire landscapes.’ (Taylor Citation2013, 197)

Such support for others’ work was typical of Chris, and the editors of many other journals, county as well as national, could say the same. Indeed, as the following pages will begin to make clear, throughout his career he was a constant buttress and inspiration to a whole range of organisations, more than we could cover in this short paper, in which we focus on his academic and field work. One measure of his wide influence is that in the years immediately after his official retirement in 1993, no less than three different Festschriften, collections of papers in his honour, were published, each from different ‘communities’, and this alone testifies to the breadth of this influence (Everson and Williamson Citation1998; Pattison et al. Citation1999; Darvill and Barker Citation1997). We have settled for three voices in this collection, and therefore only on three dimensions of Chris’s life, but as all three contributions make clear, each of those dimensions interlocks with others that we have been obliged to leave out.

Formal obituaries of Chris are available in the Guardian and Times newspapers, but by way of introduction a brief dry summary of dates will be set out here to sketch the broad framework of his ‘official’ career. In 1960 he joined the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (hereafter RCHM)Footnote1 and stayed until early ‘retirement’ in 1991. From 1960 to 1984 he contributed to and saw to publication—with extraordinary speed, unusual success and great productivity—RCHM Inventories for West and North East Cambridgeshire (and Peterborough New Town and Stamford), and six volumes on Northamptonshire. Thereafter his various posts took him away from direct field work but gave him the opportunity to guide and shape RCHM philosophies and activity into new and ever more productive directions until his early ‘retirement’ in 1993 (and even afterwards). Throughout all that, however, and extending into very recent years, came a steady stream of academic papers (many, as the list of references at the end of this article demonstrates, written in partnership with others) and—in the earlier years—influential books. A bibliography up to 1998 was published in Everson and Williamson Citation1998, and an updated one has been compiled for Landscape History (Oosthuizen Citation2021). In addition, Chris also devoted himself to adult education and the professional mentoring of younger colleagues, thus infusing a landscape sense into more than one generation of landscape historians and archaeologists,

If memory serves me well, it was from one of Chris’s early books, the 1974 Fieldwork in Medieval Archaeology, that I taught myself how (more or less) to do a plane table survey when no other means seemed to be available, and long before EDMs; that it roughly worked is down to Chris’s explanation in the book, not to my field skills (Taylor Citation1974a, 45-46). It was in the final chapter of that book, incidentally, that Chris coined the term ‘Total Archaeology’ to promote landscape-based, multi-period and interdisciplinary approaches to understating the past, a reasonable summary of the thrust of his work over many decades, and one of many reasons why we add him to our Founders series (Taylor Citation1974a, 150-51).

Although Chris retired from public employment when he left the RCHM in 1993, his research continued to bear fruit for many years more, and his final publication appeared only in 2019. In that paper indeed his institutional affiliation is given as ‘Independent researcher; formerly Head of Archaeological Survey, RCHME’. Arguably, as readers between the lines of Paul Everson’s account below will see, Chris had always been an independent researcher, even within RCHM, always at the forefront, always breaking new ground, always independent.

That final paper published in 2019, mentioned below by Paul Everson, concerned medieval temporary camps (Taylor Citation2019). In it Chris built on an archival find—an accounting entry of 1284 in the king’s books of ‘Necessary Things’—that had been noticed many decades earlier (and given to Chris in 1973) by his near namesake Arnold Taylor. The story of that paper thus brought about a nice fusion of the two strands of the British tradition of public research on history, archaeology and landscape: the RCHM to which Chris devoted so much of his life, and the Ancient Monuments Division of the Office of Works in which Arnold Taylor worked and eventually led from 1935 to 1972. Such a fusion in some ways symbolises Chris’s interdisciplinary approach to the study and understanding of landscape, the continual bringing together of separate strands. I came across the paper by chance in the spring of 2021. I had been looking at similar transcripts from the late thirteenth century bureaucracy of the royal household, trying to create a biography for a man called William de Felton (a personal lockdown and part-retirement project built on guilt over long unfinished research from the 1980s), and I recognised the style of the transcript, the name of the young man in charge of the diggers for the camp (James de Stafford, a close colleague of Felton), and its subject matter (Felton had a similar task in Gascony, assisting to build a temporary place in the Aragonese border, in that case for two kings and their courts to meet). Aha, I thought, I must contact Chris and chat with him, seek his advice; but three weeks later came news of his death, and once again, something had been left too late.

Chris Taylor, RCHM and the art of Field Survey (Paul Everson)

Chris Taylor worked for a single employer for the whole of his career: the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHM). That was from September 1960 to near the end of 1993, when he took early retirement. For much of that time, he was one of the few individuals from the English Commission known to the wider archaeological world, because he was active in learned societies, contributed interestingly to conferences, wrote prolifically, and (for example) took his part as one of the founding committee of the fledgling Institute of Field Archaeologists—the discipline’s professional body. Precisely because Chris went outside RCHM to connect with the broader development of topics, it might seem easier to detail how he did not affect the methods and approaches of RCHM than how he did. Nevertheless, his influence was profound.

Although surveyed plans of earthworks and cropmarks were the bread-and-butter of RCHM activity, Chris was far from obsessive about the process of their creation. Desmond Bonney had introduced him, as a summer survey assistant at Salisbury at the end of the 1950s, to the satisfaction and stimulation of archaeological fieldwork and the recording of earthworks using in particular the (very English) tradition of ‘hachures’. He taught him to look for insight or understanding from the process of documenting ‘humps and bumps’, which could thereby be both intellectually stimulating and academically important … and fun. Chris would say that the peerless Collin Bowen subsequently challenged and refined his observational and deductive skills (Taylor Citation2010). Indeed, he enjoyed the practical process in the field of making a survey diagram develop into a scaled, two-dimensional depiction of earthworks; but he was no mere surveyor: pragmatic, rather, about the mechanics of survey and not finicky about detail for its own sake. Historically, RCHM hachured field diagrams were undertaken to produce illustrations in published inventory volumes. They could look subtle and stylish in print, as when drawn up by the best of the RCHM’s draftsmen, like many of the hillforts in the Dorset volumes (RCHM Citation1952; Citation1970-1975a), or utilitarian, like the run-of-the-mill drawings published in the Northamptonshire inventories (RCHM Citation1975b / 1979; RCHME Citation1981/ 1982). The latter were no doubt a record—sometimes of earthworks that were subsequently destroyed - but for Chris they were principally a means to an end, which was some level of understanding of what the field remains represented and why they took the particular form they did.

Thus, in Fieldwork in Medieval Archaeology—one of his most influential works - he set out half-a-dozen practical ways of doing an earthwork survey, not recommending or condemning any one, but rather encouraging the reader just to get on and do it by any means available (Taylor Citation1974a). That, too, was also the tenor of his teaching field-survey on the famous courses with Tony Brown at Knuston Hall in Northamptonshire. To illustrate Chris’s priorities from personal experience, when I took the initiative to begin surveying in Lincolnshire in the mid-1970s using non-specialist labour on a contemporary Job Creation Scheme—nominally on behalf of RCHM—Chris’s response was ‘why not give it a try?’ but ‘no, I have no equipment I can lend you or time to offer training’. And when I made 1:1000 our working scale rather the RCHM’s traditional 1:1250, he appreciated that the thinking was purely practical: namely that if we mislaid the scale ruler in the field, we could go to a local shop and buy a standard 30-centimetre ruler and carry on. What he wanted to hear was not the scale of the survey but what did we make of the resulting diagram! Typically, his several visits to the successive schemes I ran were crucial to their success: both because such an eminent practitioner was bothered to visit (and clearly enjoyed himself in doing so) and because he was looking for outcomes beyond mere surveyed plans (). His inquisitive approach both established expectations and confirmed the value and purpose of the process.

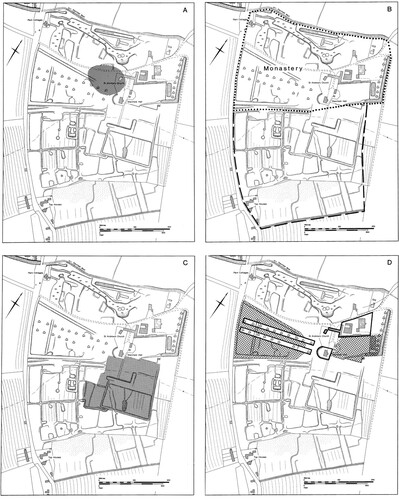

Figure 2. Stainfield Priory, Lincolnshire. Chris visited supportively in the late 1970s when the site was surveyed through a Job Creation scheme. While insisting that there had to be separate monument accounts in the published text, he sanctioned attempting to portray a changing landscape graphically. The result was this simple monochrome interpretation sequence attempted, innovatively for RCHM, to unpick complex earthworks (Everson et al. Citation1991, Fig. 24): (A) presumed location of pre-twelfth century village; (B) site of twelfth century monastery and relocated village; (C) area of early seventeenth century gardens; (D) area of early eighteenth-century gardens and park. (RCHME / Historic England).

Similarly, when the new technologies of electronic distance measuring equipment and then GPS arrived (Ainsworth and Thomason Citation2003; Bedford et al Citation2011), Chris supported their purchase and deployment in RCHM. But - importantly - his enthusiasm for the innovations lay in the underpinning they provided for accurately-located survey of extensive and remote moorland landscapes, or large parkland areas, or awkward coastal or intertidal locations, of the sort that were completely inaccessible to the RCHM he had joined, rather than in direct survey of earthworks. By that time, he could see machine-based surveys increasingly being done outside RCHM which neither observed and recorded stratigraphic relationships within the earthworks nor were accompanied by any descriptive and analytical text. And so, rather unexpectedly, he became influential in perpetuating the best of RCHM traditions through his example and commitment through the 1980s and 1990s: old archaeological virtues, that were explained to a wider audience in his own and related publications (Taylor Citation1974a; Bowden Citation1999; Citation2002; Ainsworth et al. Citation2007).

What Chris most sought for himself from field survey, and hoped for from others, however, was insight and understanding. Wherever he was and whatever he was looking at, he wanted to know how and why things were as they were. He sought explanation and narrative: ‘give me the story’. The sort of collecting and categorising of sites that might have seemed to be RCHM’s established purpose was not an adequate end for him. Such pigeon-holing of discrete monuments did not accord with his experience of the English landscape, which he came to see as interconnected, dynamic, with a deep time-frame, and full of change. Hence his willingness to refresh Hoskins’s The Making of the English Landscape, when perhaps not otherwise comfortable to be identified simply with that English romantic tradition (Hoskins Citation1988; Taylor Citation2005; Johnson Citation2007, 34-69). To some extent, he adapted the conventions of RCHM inventories and their published sectional prefaces in order to accommodate what he thought important. His full entry for the early garden layouts at Boughton House in Northamptonshire III was, famously, ‘longer than the Commission’s account of Maiden Castle’ (RCHM 1979, 156-62). But his main strategy personally, especially when given his head in Northamptonshire, was to work briskly and efficiently at the process of inventorying (as he had done previously in fulfilling commitments to West Cambridgeshire, Peterborough New Town, and North-East Cambridgeshire) and thereby to see the breadth of the evidence-base from which thematic insights could be distilled. From his energy and sense of what mattered came an exceptional flood of publications alongside but outwith those formally published by the Commission.

The scrapping of any inventory programme that followed Peter Fowler’s appointment as Secretary in 1979, and an influx of additional staff from the former Ordnance Survey Archaeology Division, gave Chris (now ‘Head of Field Survey’) resources to re-deploy. At last, the establishment of local offices around England enabled RCHM, under his guidance, to deliver new, more complex objectives in all parts of the country. He relished the opportunities now available to investigate and make better-known new categories of monument, such as post-medieval formal gardens and industrial remains of all sorts (RCHM Citation1984), especially when that served initiatives to evaluate and designate such monuments (e.g. Everson Citation1997; Cocroft Citation2000). He was also proud of the move—enabled by the advent of digital word-processing—routinely to produce and make available RCHM site reports as grey literature output. He promoted staff publications in county and national journals, targeting outlets, engineering openings and developing staff confidence. He registered with pleasure survey in new geographical locations, undertaken on new monument types, and resultant outreach to related disciplines (Everson Citation1989, Citation1995). He fought for publication of thematic work that he thought worthwhile in its innovative approach (e.g. Everson et al. Citation1991; Welfare and Swan Citation1995). In short, through the later 1980s and early 1990s Chris oversaw a period when RCHM’s archaeological activity developed a new purpose, that was active nationally and integrated into conservation and management need in the public service, and used its capacity to be pioneering in what it tackled. These were developments much in the Taylor image: engaged, helpful, focused in doing and making a genuine difference. Though, almost inevitably, he found work programmes prone to institutional inertia compared with what he had achieved in his own time in the field, he gave full support to those who tried to ‘get things done’. The qualities of that time are reflected in two Festschriften produced within RCHM—one for Norman Quinnell and another for Chris himself—and in the statement of practice published as Unravelling the Landscape and dedicated to Charles Thomas (Bowden et al. Citation1989; Pattison et al. Citation1999; Bowden Citation1999).

Nevertheless, the work that these publications describe and illustrate generally had neither the broad sweep nor purpose nor sense of context that is the hall-mark of Chris’s own output. They were capable reports of work done, but often lacked narrative or articulation of their impact on received understandings. Significantly, Chris termed himself a landscape historian rather than a landscape archaeologist (still less a field surveyor). He saw what he did—rooted though it was the detailed study of humps-and-bumps (and absorbing at that level)—as part of a larger shared enterprise of cultural history to which he aspired to contribute. Few of us—his peers and would-be imitators - even recognised, let alone had the ability to implement, that aspiration. Institutionally, the RCHM could not then do it, in any of its guises. Chris’s final publication, about medieval temporary camps in west Wales, speaks to this aspiration (Taylor Citation2019). It was brought to fruition in Landscape History, by courtesy of his old friend Della Hooke, long after he had declared himself no longer capable of new research and was perhaps less technically finished than he would once have delivered. Nevertheless, it connected medieval documentation with the landscape and with well-known Roman-period earthworks at Tomen y Mur in a thought-provoking way. The stimulus had come from the great Arnold Taylor fifty years before as a question about some scraps of thirteenth-century royal documentation; in the end, Chris could not leave such an interesting narrative unpublished or such a key cultural question undebated. That sense of the inquisitive mind’s responsibility to history was such a powerful impulse in the man that, perhaps, he could never have embedded it in the methodology of a mere state institution like RCHM. He could only exemplify it to individuals both within and outside the institution.

Christopher Taylor and the Invention of an Archaeology of Gardens (Paul Stamper)

Chris’s signal contribution to the study of—let’s call it garden archaeology, although his approach was always far more catholic than this suggests—is well known. All treatments of the subject acknowledge this. An especially full critical appreciation of his work in this field was published in one of the three Festschriften with which Chris was presented (Everson and Williamson Citation1998). In the brief overview which follows, I have taken a chronological approach, following Chris’s career as, by happenstance as much as design, he discovered, and then pursued, the physical remains of designed landscapes. It is based in part on a number of conversations I had with Chris where he discussed his career, and his and the RCHM’s working methods, especially as it related to Northamptonshire.

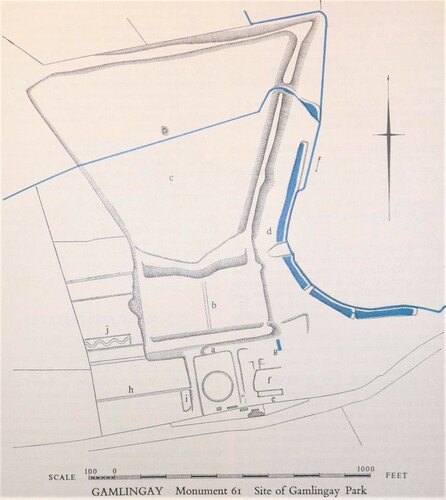

In October 1960 Chris was posted by the RCHM—unwillingly, as he thought he was to be sent to survey Dorset - to start work on what was eventually published as West Cambridgeshire (1968). This was the genesis of all Chris’s later work on garden history and archaeology. As he and Ron Butler (d.2012) surveyed and classified 63 medieval moated sites, it was realised that seven were not medieval moats at all, but post-medieval gardens. And a further six had been adapted to form gardens at a late stage in their history. The discovery of what were, in effect, abandoned gardens, together with the discovery of the remarkable earthworks of the house, gardens, lake and ponds created by Sir George Downing at Gamlingay in 1712–13 () can now be seen as the beginning of the ever-increasing number of such sites that soon appeared and continued to be discovered. As much as anything this marked the beginnings of analytical field archaeology on gardens that was to have such remarkable repercussions in later years (RCHM Citation1968, lxiii, 110-12).

Figure 3 The RCHM plot of house and garden remains of Sir George Downing’s gardens at Gamlingay Park, one of Chris’s earliest garden surveys, published in RCHM West Cambridgeshire (1968), 111. The house (a) extended around three sides of a courtyard with ‘a circular feature’. Northward were terraces (b), and beyond a trapezoidal lake (c). The site was also illustrated with an air photo (Plate 3). (RCHME / Historic England).

In late 1961, Chris moved to Whiteparish (Wiltshire) to start work on the RCHM Dorset volumes, which occupied him for the next five years (). Again, garden earthworks—Eastbury an important example - were discovered and plotted, and later featured in his Dorset in the Making of the English Landscape series, in effect an overview of his discoveries and new thinking on landscapes developed over that period (Taylor Citation1970, 142-5). Chris once observed in conversation with me: ‘Rash and immature it may be, but it covers most of the really important questions about the origins of the English Landscape and I think that it is one of the two publications that I am most proud of.’

His career took an unexpected turn in 1966 through the decision to designate Peterborough as a New Town. Moving to Whittlesford (Cambridgeshire), and based at the Cambridge office, a year was spent on a rapid survey of the designated area. Then it was back to work on North-East Cambridgeshire (Citation1972), which was followed up by Chris’s second volume in the Making of the English Landscape series, Cambridgeshire (Taylor Citation1973, for gardens see especially 153-4, 162-9). In the area covered by North-East Cambridgeshire there were few garden remains, but by then Chris (always hugely busy in adult education alongside his work for the Commission) had teamed up with Tony Brown from Leicester University’s Department of Adult Education, running weekend courses at Knuston Hall (Northamptonshire). It was these which led to what remains one of the most influential publication on garden earthworks, their survey of the unfinished gardens of c.1600, with canals and prospect mounds, linking Sir Thomas Tresham’s house at Lyveden (Northamptonshire) with its extraordinary valley-top garden lodge, the New Build (Brown and Taylor Citation1973) ().

Figure 4. Lyveden, Northants. Sir Thomas Tresham’s great water gardens were never finished, and the west arm of the moat was left undug. This view looks along the south arm of the moat towards the prospect or ‘snail’ mound at its corner. (Photo: Paul Stamper.)

It was in part his friendship with Tony Brown which led Chris to suggest to the Commission that Northamptonshire should be his next project, the rural county to be treated in four volumes—a parish a week initially single-handedly but for a month each year aided by students from Knuston Hall. Even for Chris the pace was unrelenting, or in his words ‘completely knackering.’ The first Northamptonshire volume came out in 1975, the fourth in 1982. A fifth, multi-author, volume on Northampton and its churches came out in (RCHM(E) Citation1985).

These discoveries, made at the time when better protection for historic gardens was being urged, ensured not only that early sites represented solely by earthworks made it into the embryonic Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest (established in 1983) but also that the survival of field remains became an important criterion in the consideration of potential sites for future registration. In a few instances, the importance of the individual site was further recognised by it being scheduled as an Ancient Monument, thereby giving robust protection.

Chris was always a prolific author, and alongside his Commission volumes produced a series of important and wide-ranging articles and books, including Fieldwork in Medieval Archaeology (1974) which included a short section (pp. 135-7) on an ‘important type of earthwork remains, which has only recently been recognised as extremely common … abandoned formal gardens of the sixteenth, seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.’ Examples were drawn from the counties where he had worked, and illustrated with an air photograph of the spectacular terraced gardens (The Falls) at Harrington (Northamptonshire). Never afraid to be firm in his professional opinions (as opposed to his site interpretations, where he always acknowledged he might well be ‘wrong again’), he noted that most work on historic gardens had until then been done by historians, using existing gardens around great houses and documentary sources. ‘A much better history of garden design’ he argued ‘could be written by field archaeologists carrying out detailed examination of the hundreds of gardens of all periods, which still exist buried in woodland or on waste ground.’ (pp.135-6) That said, Chris always made sure that he knew who built them and enlarged them, who their owners married and the origin of the wealth that lay behind their creation. And buildings always came into the mix too.

Northamptonshire (I declare an interest as a native) must be among the richest counties for garden earthworks, a product of a large number of middling-to-great estates (‘a county of squires and spires’ as the old saying goes), and sticky clay soils which on the one hand encouraged the modelling of terraces and the like, and on the other dissuaded later improvers from levelling them. Many of the Northamptonshire sites Chris worked on appeared as examples in his small but hugely influential (which it remains forty years on) Shire book, The Archaeology of Gardens (Citation1983a). Highlights include Wakerley, Boughton and Holdenby, where the gardens were created between 1579 and 1587 by Sir Christopher Hatton, and are (according to Chris) perhaps the best preserved of all sixteenth-century gardens in Britain.

Promotion in the Commission ended official active fieldwork, but important discoveries still came as he travelled the country visiting regional offices and colleagues, further expanding the scope of ‘garden archaeology’, and notably establishing that high status medieval sites, too, could be set off by designed landscapes. Having been alerted to this possibility by a trip with Paul Everson to the medieval Bishop of Lincoln’s palace at Stow (Lincolnshire), a chance visit to a snowbound Bodiam Castle (East Sussex) led to the identification of what has become one of the most frequently cited (if contested: e.g. Platt Citation2007; Johnson Citation2017) examples of a medieval designed landscape. Here a great house had been carefully sited—or so Chis and his colleagues proposed - within ponds and its moat which the main approach wound through, presenting visitors with an ever-changing view (or ‘experience’) of the castle (Taylor et al. Citation1990). Looking around, Chris soon found other examples, for instance at Somersham (Cambridgeshire), a medieval residence of the bishops of Ely, which were joined by more encountered by chance or design while on holidays across England. Meanwhile, prompted by these early publications, Commission colleagues and others added dozens more examples from around the country.

Chris was a great believer in publishing summaries and overviews, making sense of and contextualising site-specific studies and especially pointing out what remained unknown. For garden archaeology he authored four overviews of one kind or another (Taylor Citation1983a; Citation1991; Citation1998a; Citation1998b), while his work provided much of the intellectual underpinning as well as data for later and more ambitious volumes by younger scholars such as Robert Liddiard (Citation2005) and Oliver Creighton (Citation2009).

Villages and Farms: Christopher Taylor and the Study of Rural Settlement (Tom Williamson)

It is hard to write objectively about an individual who has had such an immense influence on one’s own intellectual development. And it is even harder to address only one aspect of their work. But Christopher Taylor’s contribution to our understanding of settlement history has been particularly important, even if in some ways its originality is now insufficiently acknowledged. As so often with intellectual pioneers, their significance becomes less noticed as their insights become the next generation’s orthodoxies. Easily forgotten, in particular, is the novelty of Chris’s underlying approach: an awareness that archaeology, and in particular non-invasive but systematic surveys, could greatly amplify the information inherent in the forms and patterns of the landscape itself—the layout of boundaries, roads and other features which for W.G. Hoskins had constituted ‘our richest historical record’. Chris, we might say, brought a new and more rigorously archaeological approach to landscape history just as, in the 1970s and 80s, Oliver Rackham provided it with a new ecological dimension.

In his many books—most notably, perhaps, Village and Farmstead (1983b) and Fieldwork in Medieval Archaeology (1974a)—and in a string of important articles, Chris shifted our perspectives on the history of settlement in England in many important ways, but I will here note only a few. First and foremost he championed, from the early 1970s, the idea that later prehistoric and Roman settlement had been far more extensive than was then generally accepted. Aerial archaeology and, in particular, fieldwalking surveys, many by ‘amateurs’ rather than professionals, had led to what he termed a ‘quantitative revolution’ in the numbers of known pre-medieval settlements (Taylor Citation1972a, Citation1975). This in turn indicated that areas characterised by the upstanding remains of prehistoric and Roman fields and farms, rather than necessarily representing the ‘core’ areas of early settlement, were in reality ‘zones of preservation’ which had simply escaped the destructive effects of medieval and post-medieval cultivation (Taylor Citation1972a). Settlement, in the Iron Age and Roman periods especially, could be found almost everywhere, even on the heaviest clays. Such ideas are now so widely accepted that it is hard to think of them as once having been ‘revolutionary’, but they were. Chris was fully aware that this recognition of time depth had implications extending beyond settlement per se, to issues of organisational and territorial continuity, and although these were only examined cautiously by him (Brown and Taylor Citation1978, Taylor Citation1982a) they opened up lines of exploration which were subsequently explored by others, some proving to be fruitful avenues of research but others meandering dead ends.

From the early 1970s Chris addressed the question of how the dense settlement pattern of the Roman period was related to the villages, farms and hamlets of the Middle Ages. While acknowledging that the fifth and sixth centuries saw a major retreat of settlement from marginal land, he emphasised aspects of continuity. He repeatedly argued, drawing again on a range of archaeological fieldwork, that nucleated villages had not been introduced by Germanic settlers in the fifth and sixth centuries. The early Anglo-Saxon period had instead been characterised by a more scattered pattern not unlike the dispersed farms and villas of the Roman period. Villages had emerged later, in some cases as late as the twelfth century (Taylor Citation1974b, Citation1977, Citation1978a, Citation1983b, 125-50).

His discussions of village origins perhaps epitomise the new archaeological perspective that he brought to settlement studies. Hoskins and others of his generation, grounded in the approaches of economic history and geography, had emphasised how the origins of rural settlements could be ‘read’ from their forms, either extant today or recorded on early maps (). Chris did not reject this approach but he nuanced it in a number of important ways. Morphological analysis needed, wherever possible, to be combined with archaeological survey—fieldwalking and the analysis of earthworks—for often this revealed marked differences between village plans as they were today, and as they had been in the High Middle Ages. This in turn ensured that in interpreting settlement morphology his emphasis was on elucidating development over time, rather than on the recovery of fossilised original form. Different patterns of historical development could lead to very similar morphological forms, thereby casting doubt on the kinds of classificatory schemes which might, for example, see ‘green villages’ as a single settlement type: some ‘village greens’, for instance, might have been deliberately created to serve as market places (Taylor Citation1982b). But by combining morphological and archaeological approaches important light could be thrown on the history of settlements, highlighting phases of expansion and reorganisation, including the infilling of formerly open spaces and acts of deliberate planning. For this writer, the most important insight was the idea that many villages had ‘polyfocal’ origins—they emerged through the expansion, and fusion, of neighbouring farms or hamlets—something which he first suggested in 1977 but elaborated, in a variety of ways, over the following decade (Taylor Citation1977, Citation1983b, 131-33).

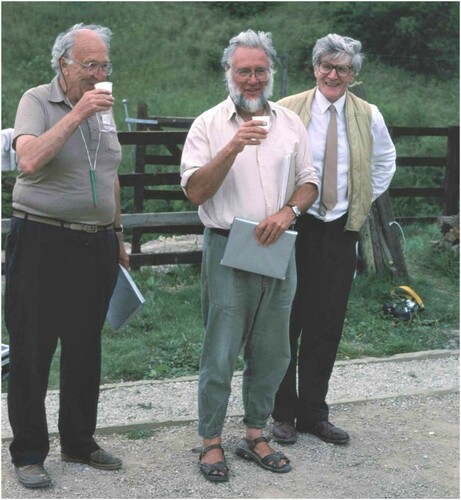

Figure 5. Chris Taylor (on right) with John Hurst (centre) and Maurice Beresford (left) at Wharram Percy July 1989 (Wharram Research Project).

Yet as the title of Village and Farmstead indicates, Chis was not only interested in nucleated settlements, but also in dispersed ones. He revolutionised our approach to moated sites, suggesting that moats were more fashion statement than defensive feature (Taylor Citation1972b, Citation1978b); and he contributed in a wide variety of ways to our more general understanding of isolated farms and hamlets. Of particular importance was his observation that some of these places were significantly older than was usually assumed, with pre-Conquest rather than twelfth- or thirteenth-century origins. In many if not most cases the first appearance of a place in the documentary record provided a poor guide to its actual origins (Taylor Citation1973, 77-90, Citation1983b, 180-3).

Change in settlement forms did not cease with the end of the Middle Ages, and another of Chris’s key contributions was to emphasise the importance of post-medieval developments. A fifth of Village and Farmstead is in fact devoted to the modern landscape—not only to such matters as emparking in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but also to the effects of railways, suburbanisation and the enforced depopulation of villages in twentieth-century military training areas. Like all true students of the landscape Chris was a generalist, interested in all chronological periods. Post-medieval settlement changes, even twentieth-century developments, were both interesting in their own right and needed to be understood if earlier phases of settlement history were not to be misinterpreted. For as he often observed, many features of settlements (as of the landscape more generally) which we might assume to be of medieval origins are in reality of post-medieval date—and no less interesting for that. In his approach to settlement as to landscapes more generally, Chris was suspicious of broad generalisations and over-arching theoretical models. Exceptions often did not prove the rule: they highlighted its shortcomings. He enjoyed undermining simple schemes of regional classification, noting for example the presence of areas of dispersed settlement deep within the ‘village belt’ of the ‘champion’ Midlands (Brown and Taylor Citation1989; Taylor Citation1995). Human agency, even individual decisions, counted for more than environmental determinants in shaping morphologies and distributions; villages might be planned at the whim of powerful early medieval landowners, just as they were cleared away by their late medieval descendants. Coherent patterns could emerge from the interplay of chance and fashion, and the spatial configurations of broad settlement regions, even that of the ‘champion’ itself, were potentially the consequence of essentially random and accidental factors (Taylor Citation2002). On these latter matters, it should perhaps be said, he and I parted intellectual company, but not on more fundamental issues of approach.

Above all, Christopher Taylor displayed a relentless urge to revisit and revise, born of the belief that all historical truths are provisional. His extraordinary reassessments of the history of the Cambridge village of Whittlesford should be required reading for all students of the English landscape (Taylor Citation1989). No single individual has contributed so much to the study of English rural settlement (as of so many other subjects), or communicated their ideas in so clear and accessible a way, to so wide an audience.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Everson

Paul Everson is currently an Honorary Lecturer at the University of Keele. He an archaeologist and landscape historian who worked for many years in the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments of England.

Paul Stamper

Paul Stamper currently a Visiting Research Fellow at the Centre for English Local History at the University of Leicester and director of the historic environment consultancy PSH, has worked on many aspects of the post-Roman English landscape with the Victoria County History and Historic England.

Tom Williamson

Tom Williamson is Professor of Landscape History at the University of East Anglia and has written widely on landscape archaeology, environmental history and the history of landscape design.

Graham Fairclough

Graham Fairclough has been co-Editor of Landscapes since 2012.

Notes

1 RCHM, established in 1908, became RCHM(E) c1980, and subsequently RCHME; but, for the sake of clarity, such niceties of nomenclature are ignored here in favour of RCHM throughout, the form in use when Chris joined the organisation in 1960. RCHM was amalgamated with English Heritage in 1998 (Sargent Citation2001).

References

- Ainsworth, S., Bowden, M., McOmish, D. and Pearson, T. 2007. Understanding the Archaeology of Landscapes: A Guide to Good Recording Practice (Swindon: English Heritage); available on-line at Historic England.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/.

- Ainsworth, S. and Thomason, B. 2003. Where on Earth are We? The global positioning system (GPS) in archaeological field survey, English Heritage; revised edition available on-line at HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/

- Aston, M., Bond, J., Chartres, J., Dyer, C., Roberts, B., Slater, T., Stamper, P., Taylor, C. and Austin, D. 2006. Founders: Maurice Beresford. Landscapes 7 (2), 90–104.

- Bedford, J., Pearson, T. and Thomason, B. 2011. Traversing the Past: the total station theodolite in archaeological landscape survey, English Heritage; available on-line at HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/

- Bowden, M. ed. 1999. Unravelling the Landscape: an inquisitive approach to archaeology, Stroud: Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England /Tempus.

- Bowden, M. 2002. With Alidade and Tape: graphical and plane table survey of archaeological earthworks, Swindon: English Heritage; revised edition available on-line as Graphical and Plane Table Survey of Archaeological Earthworks: Good Practice Guidance at HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/

- Bowden, M., Mackay, D. and Topping, P. eds. 1989. From Cornwall to Caithness (Papers presented to Norman V. Quinnell), BAR British Series 209 (Oxford).

- Brown, A. E. and Taylor, C. C. 1973. The Gardens at Lyveden, Northamptonshire. Archaeological Journal 129, 154–60.

- Brown, A.E. and Taylor, C. 1978. Settlement and land use in Northamptonshire: a comparison between the Iron age and the middle ages. In Lowland iron age communities in Europe, eds. B. Cunliffe and R. T. Rowley, 77–89. Oxford: BAR Publications.

- Brown, A. E. and Taylor, C. 1989. The origins of dispersed settlements: some results from Bedfordshire. Landscape History 11, 61–81.

- Cocroft, W. 2000. Dangerous Energy: the archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, English Heritage.

- Creighton, O. 2009. Designs Upon the Land: elite landscapes of the middle ages, Boydell.

- Darvill, T. and Barker, K. eds 1997. Making English landscapes, changing perspectives, based on lectures given at a symposium held at Bournemouth in 1995 in honour of Christopher taylor, Oxbow.

- Everson, P. 1989. The Gardens of Campden house, chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. Garden History 17 (2), 109–21.

- Everson, P. 1995. The Munstead Wood Survey 1991: the methodology for recording historic gardens by the royal commission on the historical monuments of England. In: Gertrude Jekyll: essays on the life of a working amateur, eds. M. Tooley and P. Arnander, Michaelmas Books, 71–82.

- Everson, P. 1997. Formal garden earthworks, English Heritage Single Monument Class Description, English Heritage.

- Everson, P. and Williamson, T., eds. 1998. The archaeology of landscape, Manchester University Press.

- Everson, P. and Williamson, T. 1998. Gardens and designed landscapes. In: The archaeology of landscape, eds. P. Everson and T. Williamson, Manchester University Press, 139–65.

- Everson, P., Taylor, C. and Dunn, C. J. 1991. Change and Continuity: rural settlement in North-West Lincolnshire, Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England: HMSO.

- Hoskins, W. G. 1955. The making of the English landscape, Hodder and Stoughton

- Hoskins, W.G. 1988. The making of the English landscape, new edition, with introduction and commentary by C. Taylor, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Johnson, M. 2007. Ideas of landscape, Blackwell.

- Johnson, M. ed 2017. Lived Experience in the Later Middle Ages: studies of Bodiam and other elite landscapes in South-eastern England, The Highfield Press.

- Liddiard, R. 2005. Castles in Context: power, symbolism and landscape, 1066-1500, Windgather Press.

- Oosthuizen, S. 2021. Christopher Charles Taylor 7 November 1935–28 May 2021. Landscape History 42 (2), 5–23.

- Pattison, P., Field, D. and Ainsworth, S. eds 1999. Patterns of the Past. Essays in landscape archaeology for Christopher Taylor, Oxbow Books.

- Platt, C. 2007. Revisionism in Castle Studies: a caution. Medieval Archaeology 51, 83–102.

- RCHM 1952. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 1, West, HMSO: London.

- RCHM. 1968. West Cambridgeshire: an inventory by the royal commission on historical monuments, HMSO.

- RCHM 1970-1975a. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volumes 2, 3, 4 and 5, HMSO: London.

- RCHM. 1972. North-East Cambridgeshire: an inventory by the royal commission on historical monuments, HMSO.

- RCHM 1975b / 1979. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volumes 1 and 2 Archaeological Sites, HMSO: London.

- RCHME 1981 / 1982. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volumes 3 and 4, Archaeological Sites, HMSO: London.

- RCHM(E) 1984. Surveys of Industrial Landscapes: Clee Hill, Shropshire and Cockfield Fell, County Durham. In RCHME annual review 1983-4: outline history of past 75 years, and current work, RCHM(E), 18–21. Swindon.

- RCHM(E) 1985. An inventory of archaeological sites and Churches in Northampton, HMSO.

- Sargent, A. 2001. RCHME 1908-1998 - a history of the royal commission on the historical monuments of England. Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 45, 57–80.

- Taylor, C. 1970. Dorset, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Taylor, C. 1972a. The study of settlement patterns in pre-Saxon england. In: Man, settlement and urbanism, eds. P. J. Ucko, R. Tringham and G.W. Dimbleby, Duckworth, 109–13.

- Taylor, C. 1972b. Medieval moats in Cambridgeshire. In: Archaeology and the Landscape: Essays in honour of L.V. Grinsell, ed. P.J. Fowler, John Baker, 237–49.

- Taylor, C. 1973. The Cambridgeshire landscape, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Taylor, C. 1974a. Fieldwork in medieval archaeology, Batsford.

- Taylor, C. 1974b. The Anglo-Saxon countryside. In: R.T. Rowley, ed. Anglo-Saxon settlement and landscape, British Archaeological Reports 6. BAR, 5–16.

- Taylor, C. 1975. Roman settlements in the Nene valley: the impact of recent archaeological work. In: Recent work in rural archaeology, ed. P. J. Fowler, Moonraker Press, 109–20.

- Taylor, C. 1977. Polyfocal settlement and the English village. Medieval Archaeology 21 (1977), 189–93.

- Taylor, C. 1978a. Aspects of village mobility in medieval and later times. In The effects of man on the landscape: the lowland zone, eds. S. Limbrey and J. G. Evans, CBA Research Report 21, London: Council for British Archaeology, 126–34.

- Taylor, C. 1978b. Moated Sites: their definition, form and classification. In: Medieval moated sites, ed. F. A. Aberg, Council for British Archaeology, 5–13.

- Taylor, C. 1982a. The nature of Romano-British settlement studies – what are the boundaries? In The Romano-British countryside: studies in rural settlement and economy, ed. D. Miles, British Archaeological Reports 103, 1–15. Oxford: BAR Publications.

- Taylor, C. 1982b. Medieval market grants and village morphology. Landscape History 4, 21–8.

- Taylor, C. 1983a. The archaeology of gardens, Shire Books.

- Taylor, C. 1983b. Village and farmstead: a history of rural settlement in england. George Philip.

- Taylor, C. 1989. Whittlesford: the study of a river-edge village. In: The rural settlements of medieval england, eds. M.A. Aston, D. Austin and C. Dyer, Oxbow Books, 231–46.

- Taylor, C. 1991. Garden archaeology: an introduction. In Garden archaeology, ed. A.E. Brown, CBA Research Report 78, 1–5. London: Council for British Archaeology.

- Taylor, C. 1995. Dispersed settlement in nucleated areas. Landscape History 17, 27–34.

- Taylor, C. 1998a. Parks and Gardens of Britain: a landscape history from the air, Edinburgh University Press.

- Taylor, C. 1998b. From recording to recognition. In There by Design: field archaeology in parks and gardens, ed. P. Pattison, British Archaeological Reports (British Series) 267, 1-6. London: Council for British Archaeology.

- Taylor, C. 2000. Medieval ornamental landscapes. Landscapes 1 (1), 38–55.

- Taylor, C. 2002. Nucleated Settlement: a view from the frontier. Landscape History 24, 53–71.

- Taylor, C. 2005. The Making of the English Landscape and Beyond: inspiration and dissemination. LandscapeS 6, 96–104.

- Taylor, C. 2010. Founders: Collin Bowen. Landscapes 11 (1), 84–94.

- Taylor, C. 2013. Wharram Percy 2013: the final whistle? Landscapes 14 (2), 194–8.

- Taylor, C. 2019. The history and archaeology of temporary medieval camps: a possible example in Wales. Landscape History 40 (2), 41–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01433768.2020.1676041.

- Taylor, C., Everson, P. and Wilson-North, R. 1990. Bodiam Castle, sussex. Medieval Archaeology 34, 155–7.

- Welfare, H. and Swan, V. 1995. Roman camps in England: the field archaeology, HMSO.