Abstract

This paper examines one of the most significant antecedents to, and influences on, the Grenada Revolution: the Black Power movement in Trinidad and Tobago. Focusing on the National Joint Action Committee and the New Beginning Movement, it examines their critiques of the Westminster model of governance, and the alternatives they offered. It considers whether these critiques gave rise to any political reforms in Trinidad, and asks whether the apparent failure of the Black Power movement to bring about radical political change testifies to the legitimacy and robustness of the Westminster model in the Trinidadian context. In so doing, it sheds light on the lesser known political dimensions of Caribbean Black Power; provides a regional perspective on the ideological currents feeding into the Grenada Revolution; and highlights the existence of Caribbean political thought and practice that looked beyond Westminster to conceive alternative forms of democracy and political participation.

The Grenada Revolution represents the most famous challenge to the Westminster system of governance in the post-independence Commonwealth Caribbean. Contesting the principles of the ‘hallowed Westminster model of government’, the revolutionaries of Grenada's New Jewel Movement (NJM) offered a systematic critique of the character of ‘bourgeois democracy upheld by the Westminster model and imposed upon colonised peoples everywhere the Union Jack was raised’. This critique focused, in particular, on the divisiveness of the two-party system in the context of underdeveloped small states, the lack of genuine political participation encouraged by the ‘5-second democracy’ of periodic general elections, and the facility with which the model could incorporate non-democratic, elitist and even authoritarian modes of rule inside its ‘form and trappings' (People's Revolutionary Government, Citation1981, pp. 83, 86, 88). In place of ‘Westminster hypocrisy’, the NJM offered a vision of ‘revolutionary democracy’ carried to fruition in the experimental political institutions (such as village, parish and workplace assemblies) implemented under the People's Revolutionary Government (PRG) between 1979 and 1983. For all its contradictions and flaws, Grenada's experiment with ‘people's participation’ remains the most radical deviation from the Westminster model ever attempted in the Commonwealth Caribbean.

The Grenadian experiment ‘demonstrated the extent to which concrete political practice [had] moved ahead of regional academic theorising’ in producing alternatives to the liberal democratic model of governance in the Anglophone Caribbean (Henry, Citation1984, p. 1). Indeed, as Henry argues, despite the critique of ‘dependent capitalist models of development’ advanced by the region's economists, very little political theorising in the region went beyond the parameters of the liberal tradition; the former offering ‘only very limited accounts of alternatives to the liberal state’ (Henry, Citation1984, p. 1). Yet the success of the Grenada Revolution in 1979 cannot be read as a triumph of praxis alone; if Eric Gairy was toppled so easily it was partly because the ideological groundwork for the revolution had already been laid. As this paper argues, critiques of the existing Westminster system, and experiments with alternative forms of political organisation, had been rehearsed in a number of spaces in the Anglophone Caribbean in the decade preceding the triumph of the Revolution in March 1979. These political currents, offering alternatives to the inherited Westminster system, fed into, and developed in tandem with the emergence of the NJM in Grenada, whose activities and ideology have been more extensively analysed in the existing scholarship.Footnote1

This paper turns to one of the most significant antecedents to, and influences on, the Grenada Revolution: the Black Power movement in neighbouring Trinidad and Tobago. It focuses, in particular, on two groups: the National Joint Action Committee (NJAC), the leading Black Power organisation on the island during the mass demonstrations of February to April 1970, and the New Beginning Movement (NBM), a small, Jamesian-inspired organisation born after the period of mass struggle had been brought to an end by the imprisonment of the Black Power leadership. As discussed below, both these groups had significant Grenadian links; both, through their intellectual output or through political action, attempted to formulate alternatives to the inherited Westminster political system. This paper examines their analyses of the existing political system and the alternatives they offered. It considers whether these critiques gave rise to any concrete political reforms in Trinidad, and asks whether the apparent failure of the Black Power movement to bring about radical political change testifies to the legitimacy and robustness of the Westminster model in the Trinidadian context. In so doing, it seeks to shed light on the lesser known political dimensions of Caribbean Black Power (often considered as ‘spontaneous' and lacking in coherent political content); to provide a broader regional perspective on the ideological currents feeding into the Grenada Revolution; and to highlight the existence of Caribbean political thought and practice that looked beyond the ‘Holy Tablets … received from upon the heights of Westminster’ (People's Revolutionary Government, Citation1981, p. 83) to conceive of alternative forms of democracy and political participation.

Westminster in Trinidad and Grenada

It is important to note that the Westminster model as it functioned in both Trinidad and Grenada suffered from many of the flaws commonly identified with its operation in post-colonial small states. In Grenada, the abuses of then Chief Minister Eric Gairy were publicly exposed as early as 1962 in a commission of enquiry that resulted in the suspension of the constitution. The ‘systematic degradation of the legislative and executive branches of the state’ under statehood (1967) and independence (1974) is well documented: Gairy's domination of cabinet and parliament, subornment and intimidation of public officers, harassment of the opposition, manipulation of elections, and ‘destructive personalism’ (Lewis, Citation1987, p. 13)Footnote2 all operated within the ‘smokescreen of legitimacy’ provided by the Westminster system, including ‘elections every five years, “Parliament” and the rest of the Westminster paraphernalia’ (People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada, Citation1981, p. 87). In Grenada, the illegitimacy of Gairy's regime gave rise to an extra-parliamentary and ultimately revolutionary opposition; a pattern prefigured in Trinidad where a new type of militant opposition emerged to contest the legitimacy of flawed Westminster rule.

In Trinidad, the democratic deficit was not as grotesque, but here too, the shortcomings of the Westminster system were a matter of public concern from the earliest years of independence, with intellectuals such as those of the New World and Tapia groups deploring the weaknesses of parliament and of the parliamentary opposition, declining rates of electoral participation, patronage, one-party-ism, and, above all, the centralisation of power in the person of the Prime Minister. For Lloyd Best, these flaws were not the result of the Caribbeanisation of the Westminster model, but were inherent to the model in the colonial context. ‘Right at the start’, Best argued, ‘a legacy of illegitimacy was handed down from colonial arrangements’:

successive transfers of responsibility, following Wood (1926) and Moyne (1946) [did not] successfully anchor legitimacy in the political community – representative parliament, adult suffrage and cabinet government in turn notwithstanding … . By the time the transfer of power was at hand in Marlborough House in 1962, legitimacy had become less a product of the constitutional or even political arrangements and more a property of ‘doctor politics’ and maximum leadership in the competing communities. (Best, Citation1995, pp. 716–717)Footnote3

By 1970, when the Black Power demonstrations erupted in Trinidad, the People's National Movement (PNM) led by Eric Williams had been in power for 14 years. While in the early years of the national movement ‘the essence of the political process was the charismatic domination of Dr Williams’, the years since 1967 were characterised by his increasing withdrawal from public visibility and contact with the grassroots constituency that formed the support base of the PNM (Sutton, Citation1983, p. 125). Williams' absence was symptomatic of a more widespread malaise in Trinidad's political culture. The ‘pitiful inability of the opposition to oppose’ (Huggins, Citation1970), the habitual bypassing of Parliament on matters of national importance, and de-facto one-party rule by the dominant PNM, all contributed to a corrosion of the authority and legitimacy of Trinidad's political institutions. The events of 1970 have thus been interpreted as a crisis of political legitimacy: the product of a long process of alienation from the conventional outlets of political participation. In this context, there emerged a ‘new type’ of opposition that was ‘articulate, radical and increasingly militant’; one ‘not located in Parliament but … increasingly influential on the street’ (Millette, Citation1995, p. 60). Among the most significant of these new opposition groups was the NJAC.

NJAC: Black Power as a critique of ‘conventional politics'

The NJAC was formed on the St. Augustine campus of the University of the West Indies (UWI) in February 1969. Headed by Geddes Granger (Makandal Daaga), NJAC is most readily associated with the massive Black Power demonstrations against the Williams' government that brought thousands onto the streets of Trinidad and Tobago between 26 February 1970 and the declaration of a state of emergency on 21 April that year. The ‘February Revolution’, culminating in a threatened general strike and the mutiny of a section of the Trinidad Regiment, was the first serious challenge to the legitimacy and authority of government in the post-independence Commonwealth Caribbean.

NJAC was initially founded as a loose alliance of student and youth organisations, trade unions, and cultural groups. In the first year of its existence, it ‘shed its conservative member groups’ and evolved a more ‘unitary [organisational] structure’, with ‘several organisations giving up their individual identity to become units of NJAC’, while new units were ‘established throughout the country’ (Kambon, Citation1995, p. 217). While the majority of these were concentrated in and around Port of Spain, NJAC units were also established in locations from Point Fortin and San Fernando in the south-west to Sangre Grande in the north-east.Footnote4 At the leadership level, the close association with radical trade unions was maintained, with Winston Leonard of the Oil Workers Trade Union (OWTU) and Clive Nunez of the Transport and Industrial Workers Union represented on NJAC's Central Committee (Kambon, Citation1995, p. 217).

By its nature, NJAC was ideologically heterogeneous, embracing a non-doctrinaire ideology of Black Power that could incorporate various strands of leftism and black nationalism. Partly for this reason, NJAC was often accused of lacking in political coherence, with even erstwhile supporters contending that they ‘failed to define the goals of the struggle in precise terms’ (Riviere, Citation1972, p. 56).Footnote5 This perception has been reinforced in subsequent scholarly analyses, the more critical of which have emphasised the movement's ‘[failure] to grasp the importance of revolutionary theory’, ‘senseless marching’, and empty shouts of ‘Power! Power!’ (Brown, Citation1995, p. 558). However, NJAC's lack of a manifesto was a deliberate political choice consistent with their broader rejection of ‘conventional politics' and belief that the solution to Caribbean problems could not be imposed from above, but must develop from among ‘the people’. As Kambon explains, NJAC embraced an ‘action-oriented ideology’ in which the marches and demonstrations functioned as ‘object lessons' that not only ‘incorporated the ideology of the Black Power movement’ but ‘could [also] be seen as part of its ideological statement … [heightening] the impact of its written and verbal expression on the social consciousness' (Kambon, Citation1995, pp. 223, 228). Thus, it was through participation in political struggles that the consciousness of the people would develop and new ideas and institutions evolve from their demands. ‘Regular community education sessions’ and ideological discussions were also central to NJAC's political strategy as part of a dynamic process of raising political consciousness and developing the movement from below (Kambon, Citation1995, pp. 223–224). It is important thus to recognise the political work NJAC did outside the mass meetings and demonstrations, and to view the latter as an integral part of their political self-expression. As the economic and cultural dimensions of NJAC's conception of ‘Black Power’ have been analysed elsewhere, the discussion here will be limited to their views on the political system they opposed, and their understanding of alternative forms of political organisation outside the Westminster model.

NJAC's most extensive analysis of Trinidad's political system was outlined in Conventional Politics or Revolution? a 40-page pamphlet published in the period following the release of the incarcerated Black Power leadership in late 1970. Subtitled ‘NJAC on the Political System’, Conventional Politics or Revolution formed a companion piece to From Slavery to Slavery (‘NJAC on the Economic System’) which set out their analysis of Caribbean economic dependency and made proposals for the ‘total ownership and control’ of the region's economic resources. Elaborating on analyses previously expressed in NJAC's speeches, community meetings, and periodic publications, these pamphlets were published with the express aim of facilitating ‘the mass education of the people’ (NJAC, Citationn.d., p. 1).

The analysis developed in Conventional Politics closely echoes arguments made by Walter Rodney in his Groundings with My Brothers, as well as ideas developed by the New World and Tapia groups, and elements of conventional Marxism. Beginning with the premise that ‘political institutions function as an arm of the Economic System’, the pamphlet proposed that Caribbean political institutions were shaped by the region's insertion into a global economic system of ‘White Power’, comprising an alliance between foreign economic interests (who controlled Caribbean economic resources) and their local white allies, whose survival depended on the maintenance of the status quo. In this context, the ‘rules of politics' were ‘designed to protect White economic interests', with the institutions of the state – government, police, army, the legal system, education and the media – all pressed into the service of the economic system (NJAC, Citationn.d., pp. 2–4, 9–13).

Constitutional changes – from the expansion of the franchise to the independence settlement – did not disturb the fundamentals of White Power. Rather, ‘[the] Constitution Britain imposed … in 1962 confirmed the twin forces of the White Power structure – it in no way tampered with the System and contained sufficient checks on the Government … to prevent them tampering with local white interests’. Its beneficiaries – those who in Fanonian terms had stepped into the shoes of the departing colonisers – inherited, and were complicit in perpetuating, a ‘structure of white-oriented institutions which [were] an integral part of a total system of economic, cultural, and political oppression of Black people’. The political space eventually accorded to the black middle class was thus ‘empty of all power’. The trappings of the ‘made-in-Britain’ Westminster system, including the cabinet, the House of Representatives, and the Senate, were ‘merely the rubber stamp for the White Power structure’, with decisions made by government confined to ‘the administration of the system, not decisions which [would] affect its nature’ (NJAC, Citationn.d., pp. 2–3, 17, 23).

For NJAC, such systemic problems were compounded by the culture of one-man-ism that characterised the Westminster system in the Trinidadian context. While executive powers were concentrated in the person of the Prime Minister, the legislature was reduced to parroting the empty rhetorical formulations of the Westminster parliament:

Cabinet, which is the same as saying the Prime Minister, makes all the decisions it is the authority of Parliament to make. After some tiresome rhetoric in the House of Representatives, which we vote people into, and in the Senate, filled with the Prime Minister's stooges, ‘The I's have it’ from the Ruling Party's ready-made majority, and that's law. (NJAC, Citationn.d., p. 3)

In this system, ‘politics’ was reduced to ‘the art of getting into parliament’ and political participation to the act of voting once every five years. As a result, what appeared to be political apathy was in fact alienation from institutions that had little connection to people's everyday lives; ‘the reaction of our people to a whole tradition of political frustration and exclusion from control over our affairs' (NJAC, Citationn.d., pp. 1, 24).Footnote6

For NJAC, true liberation could only be achieved by a ‘total rejection’ of the existing political system, its institutions, cultural values, and systems of knowledge. In its place, they envisaged an organic process in which ‘fundamentally different political institutions' would emerge out of the conscious struggles of the people (NJAC, Citationn.d., pp. 19, 30). This process, NJAC argued, had been catalysed by the experiences of the February Revolution, during which ‘politics was taken out of Whitehall and the Red House and became the living expression of a conscious people on the corners, in the streets, and in the People's Parliaments' (NJAC in period of self-analysis, Citation1970).Footnote7 First, the events of February to April 1970 had ‘brought to the forefront of politics the grassroots element of society’, liberating the creative energies of the people ‘in the ghettoes and on the plantations’ in whom was located ‘the real capacity for the revolutionary transformation of society’ (NJAC, Citationn.d., pp. 31–32). This social base, NJAC argued, had shaped the direction of the struggle and given the revolution its tremendous emancipatory force. Second, the new politics had begun to find institutional form in the creation of People's Parliaments, ‘in which the whole meaning of the revolutionary slogan “Power to the People” came to be embodied’ (NJAC, Citationn.d., p. 33). These People's Parliaments were a distinctive feature of the 1970 struggle, symbolically transforming Williams’ ‘University of Woodford Square’ into a democratic platform in which the stage was thrown open for anyone to speak.Footnote8 In Conventional Politics, NJAC was at pains to depict the People's Parliaments as the initiative of the people; organic institutions whose ‘forms and procedures … changed according to the demands of the people as their ideological consciousness developed’. This new expression of participatory politics was reflected in new relations between leaders and the people, now framed as a ‘two-way process of communication’ in which leaders had to be responsive to the people's demands. In this, ‘the very symbols of the relation between leaders and people showed the break from the discipleship of the past’:

The manner of address was ‘Brothers and Sisters’ to symbolise the oneness of speakers and listeners. Instead of the congratulatory applause of the followers when the master spoke, there was the aggressive shout of ‘power’ with the clenched fist salute from a people who knew their destiny was in their own hands. (NJAC, Citationn.d., p. 33)

NJAC's interpretation of the People's Parliaments was contested by other leftist groups, who saw in them instead a replication of the messianic politics and empty rhetoric they claimed to reject.Footnote9 But for NJAC, the People's Parliaments were the embryonic institutions of a new model of political organisation, whose development and full potential was cut short by the state of emergency. For Kambon, reflecting some 20 years later, these were the beginning of ‘at least a symbolic process of implementation’ that sought ‘to develop an experience of participatory politics in whatever limited ways the period allowed’ (Kambon, Citation1995, p. 241). It was this process of participation that would create the necessary psychological break with the alienating politics of the past. Ultimately, what NJAC offered as an alternative to ‘conventional politics' was not so much a blueprint for new political institutions, but the psychic liberation of the ‘true self’.

New Beginning

The Black Power upheavals gave impetus to the formation of new non-conventional political groups in Trinidad and elsewhere in the region. One such group was the NBM, a small Jamesian-inspired organisation founded in late 1970 ‘on the fringes of the battered radical movement’ (Look Lai, Citation1992, p. 205). While New Beginning was a product of the mass movement of 1970, it also maintained a critical distance from it. As shown below, New Beginning criticised NJAC for their apparent failure to move from marching and protest to develop a concrete programme or theory to achieve the desired revolution. For their part, NJAC were suspicious of the intellectual and ‘sectarian’ character of the NBM and other, primarily academic, groups who had engaged to different degrees with the broader movement of 1970.

Though described as ‘ideologically tighter’ than NJAC (W. Look Lai, personal communication, July 25, 2008, St. Augustine, Trinidad), New Beginning was not monolithic in its political influences and philosophy. The Jamesian strand of the NBM was represented by co-founders Franklyn Harvey and Bukka Rennie, who had been part of the C.L.R. James Study Circle in Montreal during the critical period of student and Black Power activism centred around McGill and the Sir George Williams universities (Austin, Citation2007). Another Jamesian, Walton Look Lai, was closely associated with the OWTU, whose radical newspaper, the Vanguard, he edited on his return to Trinidad in 1969. Others came to New Beginning out of the heterodox political currents of Black Power. These included Efebo Wilkinson, jailed for six months as part of the round-up of Black Power activists in April 1970; and the writer Earl Lovelace, an active participant in Trinidad's Black Power movement, who recalls being regarded as a ‘populist’ by the Jamesians within the NBM (E. Lovelace, personal communication, July Citation28, Citation2008, Port of Spain, Trinidad).

The New Beginning Movement is examined here for two main reasons. First, their work offers a further example of how radical groups in the Caribbean sought to theorise and lay the foundations for an alternative to the Westminster model. Second, their connections to the Grenadian struggle illustrate the complex interplay of influences that helped to shape radical politics in the Caribbean in this era. One of the critical links between New Beginning and the incipient revolutionary movement in Grenada was NBM founding member Franklyn Harvey, a Grenadian credited as the major intellectual of the Movement for the Assemblies of the People (MAP), one of the constituent organisations of Grenada's NJM. As outlined below, the ideological nexus between New Beginning and the NJM helped to shape both movements. Factional disputes that subsequently developed within the NBM foreshadowed the serious ideological fractures that would later haunt the Grenada Revolution.

While New Beginning produced a significant body of publications authored by various members of the group (including extensive political analyses by Franklyn Harvey, Walton Look Lai, and Bukka Rennie),Footnote10 the analysis here will focus on the group's weekly newspaper, New Beginning. This newspaper represents the most publicly accessible articulation of the group's political philosophy, and, with its rotating editorship and unattributed editorials, comes closest to approximating the collective public position of the group. It was also in the pages of New Beginning that the group's shift in ideological position was dramatically announced.

The first issue of New Beginning was published on 5 March 1971. Its long editorial, ‘Towards the beginning’, can be read as an extended position statement of the recently established group. ‘Towards the beginning’ opens with a familiar critique of the inherited political system and the shortcomings of its ‘Afro-Saxon’ inheritors. Invoking arguments that were by now a standard feature of the discourse of the radical left, the editorial dismissed the existing political system as an ‘imposed form of government’ that bore little relation to ‘the experiences, aspirations or philosophy of the people of this country’. This critique embraced various institutions of the Westminster model, including the parliamentary system, ‘with its House of Representatives, Senate, Governor-General, and all the other dressings’; the constitution (dismissed as ‘a colonialist document’); political parties (‘another imposition’ through which privilege was conferred and patronage dispensed); and the two-party system, viewed in the Trinidadian context as ‘a living medium for the perpetuation of racial suspicion and antagonism’. The editorial thus rejected the idea that change could be achieved by constitutional reform (then being explored in Trinidad by the Wooding Commission): ‘We do not need to patch up an irrelevant and mystifying document imposed upon us by some Europeans and their Afro-Saxon imitators’ (Towards the beginning, Citation1971).

The paper then set out its proposals for a new political order that would be ‘native, rather than metropolitan in outlook and … based on the needs, tastes, values and resources indigenous to our situation’. In a section entitled ‘East Indian Background and African Background’, the paper suggested that a new, popular form of government might draw inspiration from political systems developed in the societies from which Trinidad's major ethnic groups derived, taking elements from the Indian system of Panchayat (village councils) and the African model of ujamaa (community living) – the concept underpinning African socialism in Nyerere's Tanzania. In both cases, New Beginning emphasised the systems' basis in philosophies of community and kinship, noting also that their leaders were ‘of the people, and not above or apart from them’ (Towards the beginning, Citation1971). But it was primarily the West Indian experience and the forms of social organisation developed by its peoples in which the paper sought the ‘basis and the inspiration for the new beginning’. Citing examples of community organisation such as ‘len-han’, ‘sou-sou’, and the post-emancipation free villages, the paper invoked an indigenous tradition of self-organisation that was collective, egalitarian, decentralised, and driven from below. This emphasis on spontaneous self-organisation drew heavily on the ideas of C.L.R. James, in particular his Notes on Dialectics (1948) and Facing Reality (1958), texts which Harvey, Look Lai, and Rennie would have studied in depth.Footnote11 The conflict between such Jamesian ideas of mass organisation from below, and Marxist–Leninist ideas of revolutionary vanguardism, was one of the central ideological debates animating discussions among Caribbean radical groups in the era.

Searching for examples of self-organisation in the contemporary period, the paper then turned to Trinidad's 1970 rebellion (notably not ‘revolution’). In a section entitled ‘The New Leadership’, the paper credited NJAC with making ‘politics … a total thing’, coalescing into a national effort the ‘revolutionary work already being done … independent of national leaders’. However, in a direct critique of NJAC, the paper contrasted the ‘drama of the demonstrations, huge public meetings, and fiery oratory’ with the bottom-up mobilisation of the people, who ‘were creating new forms of organization in their own way’. Though acknowledging that NJAC's People's Parliaments were ‘intended to get the masses involved in the running of their country’, the paper argued that they had instead reproduced the leaderism and dependency complex they sought to replace:

The People's Parliament instead produced Granger, National Leader … He was the Revolution personified … Granger was ‘THE’ Messiah, and the NJAC his messianic group. (Towards the beginning, Citation1971)

Within the evolving movement, however, the people were able to develop their own forms of organisation, turning the new institutions to their own ends. Hence,

The People's Parliament initiated by NJAC in 1970 was turned upside down by the people themselves. While the NJAC leadership was talking for four and five hours in its People's Parliament, the people, particularly in the country areas, formed their own People's Parliaments where … all people present talked, discussed and debated the issues of the day. (Towards the beginning, Citation1971)

These much smaller village parliaments, where people demonstrated around local issues such as better drainage and repairs to schools, were seen as more effective realisations of the slogan ‘people's power’ than the large-scale People's Parliaments held by NJAC in Woodford Square. Alongside these developments, a series of strikes called ‘without the knowledge of’ the union leadership in April 1970 served to confirm ‘a high degree of self-organisation’ within the labour force. ‘What seems to have been emerging in 1970’, New Beginning proclaimed, ‘was the self-organisation of the people at the village or community level and at the production level’ (Towards the beginning, Citation1971) – precisely the model of political organisation the NBM endorsed.

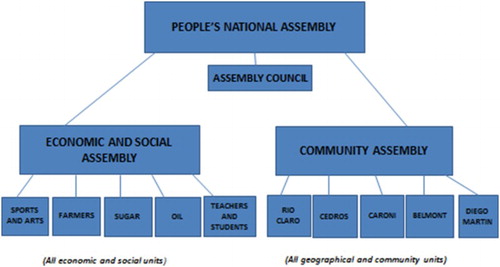

The events of 1970 thus provided evidence to support the NBM's proposals for a new form of political organisation, set out in detail in the final pages of the inaugural edition of New Beginning. The ‘revolutionary alternative’ the NBM proposed was the ‘Assemblies of the People’, a ‘total system’ of politics structured around three levels of people's assembly; local, regional, and national (see ). In this model, the Local Assembly was the most important unit of organisation. Formed around either place of residence or place of work, the Local Assembly was envisaged as ‘a small, intimate grouping of people who have similar daily experiences’ who would function as the local government of an area, ‘responsible for determining and carrying out either independently or jointly with other assemblies all community functions’. The second level, the Area or Regional Assembly, made up of a number of local assemblies, would be the ‘local government of [a] whole area’, and could ‘plan and implement plans in a more comprehensive and economical sense’. Local workplace assemblies would also have Area assemblies; thus, for example, the Area assembly for the Port of Spain bus terminal might be comprised of local assemblies of bus drivers, conductors, and mechanics, all working in the transport sector. Finally, the National Assembly, with members elected by and from the local assemblies, would function as the National Government, with a National Assembly Council appointed to ‘carry out the day to day functions of the National Assembly’. Power would not rest with the National Council, which would not have a policy-making role, but with the National Assembly, whose power ultimately derived from the Local Assembly (Towards the beginning, Citation1971).

Figure 1. New Beginning, ‘Proposed Revolutionary Form of Government’, reproduced from New Beginning, 1(4), March 24, 1971, p. 1.

The parallels with the model of People's Assemblies outlined in the NJM manifesto two years later are striking (see and discussion below). Evident too is the ideological heterogeneity of New Beginning’s inaugural issue. In this edition, invocations of ‘Black Power to the People!’ existed alongside notions of African socialism, Indian communalism, Jamesian self-organisation, and an emphasis on ‘indigenous', genuinely Caribbean, political forms. Subsequent issues continued to push these themes, reporting on the activities of local community groups who would be the ‘catalyst for the eventual birth of the local assembly’; serialising Nyerere's 1967 Arusha Declaration (framed as an alternative to the PNM's Perspectives for a New Society); warning against political office-seekers trying to ‘lead people in marches up and down the country’; and providing further explanation of the proposed Assemblies of the People (New Beginning, Citation1971, 19 March, 26 March, 1 October). But in November 1971, publication of New Beginning suddenly stopped. When it resumed in March 1972, it had undergone a significant transformation.

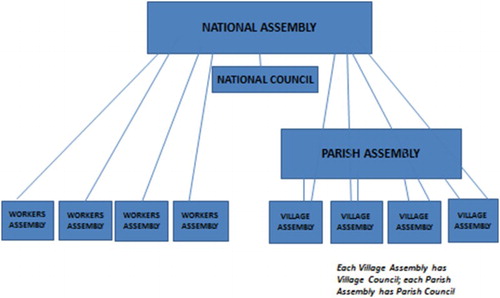

Figure 2. NJM model of People's Assemblies, constructed from NJM Manifesto (Citation1973).

On 31 March 1972, New Beginning resumed publication with an editorial entitled ‘Why our paper has not been out’. The editorial opens with reference to the state of emergency called on 19 October 1971. This was the second state of emergency in 18 months (the first running from April to November 1970), and under its auspices, once again, figures associated with radical labour and Black Power were arrested and jailed. During this period, the Williams government passed a number of bills that effectively enshrined many of the emergency powers in the statute book, including the Sedition Act, Summary Offences Act, and other legislation affecting freedom of assembly. New Beginning’s editorial invokes the atmosphere of repression in which their organisation operated during this period, citing the detention and questioning of one of their newspaper sellers, police visits to their offices and distribution outlets, and constant surveillance of their headquarters. The account also captures a sense of the divisions emerging between leftist groups in the period, referring to rumours spread by ‘supposed revolutionary groups’ that New Beginning was either a communist front organisation or sponsored by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); and pointedly observing that while New Beginning was removed from the shelves of one store, Moko and Tapia were deemed to be OK (Why our paper has not been out, Citation1972).

This gives some indication of the atmosphere in which the ‘new perspective’ evolved by the NBM was formed. As the editorial states, during the NBM's weekly political classes, ‘heavy self-criticisms on our whole ideological position … began to emerge’. In sessions re-examining their work of the previous six months, ‘our organization itself was seriously and at times “violently” criticised by the members themselves and by the individuals who were invited to participate’; consequently, publication of New Beginning was delayed until their new ideological position ‘was completely hammered out and accepted by those concerned’ (Why our paper has not been out, Citation1972).

The ‘New Perspective’ as it was outlined in the March 1972 issue now embraced a more orthodox Marxist analysis. Politics was described as ‘the administration of economics'; ‘a superstructure placed on top of the economic system’. ‘To talk about a new political form without understanding this', was thus to make ‘a grave mistake’. From this basis, the paper went on to explain the formation of social classes (‘according to the relations of the economic system’), the nature of class relations, and the development of class consciousness among the oppressed. Applying a Marxist analysis to the conditions of the Caribbean, the paper proposed that the three critical classes to emerge in the West Indian context were the working class (‘born on the sugar plantation’), the peasant or small farmer class, and the unemployed class:

These are the people who have become conscious of themselves as oppressed classes … and who are by their very positions and nature potentially revolutionary … Any movement that is serious about change must be made up of people from these three classes, especially the working class. (Our New Perspective, Citation1972)

Though the analysis clearly prioritised the working class, significant attention was paid to the unemployed, who, though lacking ‘discipline’ and ‘organization’, were viewed as ‘one of the most politically conscious sections of the population’. Notably, the unemployed were credited as the major force that had ‘initiated and almost completely carried’ the 1970 rebellion; ‘[that] tells us something about the consciousness of the unemployed and at the same time gives us one of the reasons for [the movement's] failure’ (Our New Perspective, Citation1972).

The conclusions drawn from this analysis marked a shift in New Beginning's political strategy. While ‘the objective, the Assemblies of the People, remained the same’, the strategy now explicitly emphasised ‘first … the workers, then the peasants, then the unemployed’ (Our New Perspective, Citation1972; Why our paper has not been out, Citation1972). This new direction was reflected in subsequent issues of New Beginning, which began to include a regular feature on ‘The History of the Working Class’, a ‘World’ section reporting on workers’ actions around the globe, and a new section called ‘On the Job’, covering workers’ issues in Trinidad. This included examples of workers’ disputes with management and the formation of workers’ committees outside the trade unions (the latter viewed as ‘no different [than] management and the state’) (On the Job, Citation1972). By mid-1975, the strapline of New Beginning was ‘workers’ occupation is a stepping stone to workers’ control’; and its proclaimed goal, workers’ control of the means of production. Notwithstanding these orthodoxies, the paper did not hold to official Soviet communism; it was mass organisations of self-organised workers, not a communist party, who would build the new state from below.

This shift towards an explicitly Marxist analysis parallels developments within leftist organisations elsewhere in the region at the same time (see Meeks, Citation1993). Intriguingly, former NBM member Brinsley Samaroo attributes New Beginning's leftwards shift to the Grenadians in the organisation, including none other than future PRG leader Bernard Coard. As Samaroo recalls, at a time when the members of the NJM were facing increasing repression in Grenada, Trinidad, and especially the university campus, provided a safe space for Grenadian activists to discuss developments in their country and to plan. Bernard Coard (who was to join the NJM on his return to Grenada in 1976) was Visiting Lecturer at the Institute of International Relations at UWI's St. Augustine campus between 1972 and 1974, and was an active (if not regular) participant in New Beginning at this time. According to Samaroo, Coard became fed up with the ‘softness’ of the NBM, and in this period of ideological debate a number of the less radical members were ‘shunted aside’. In the ideological discussions that took place within the NBM, and, more broadly, around developments in Grenada, ‘most of the Trinidadian academics were sidelined’; those that remained were the more ‘doctrinaire’ Marxists, among them the ‘Grenadian hard-liners’ (B. Samaroo, personal communication, August 6, 2008, St. Augustine, Trinidad). This story clearly illustrates the ideological nexus that existed between Trinidad and Grenada, and the lines of mutual influence that can be drawn between political movements on each island. But in the intensity and factionalism of these debates, it is also possible to see a rehearsal of some of the ideological divisions that would later prove so fatal to the Grenada Revolution.

From Black Power to Doc power?

To what extent then did the Black Power challenge in Trinidad give rise to concrete political reforms? While there is no doubt that the pressures exerted by the mass Black Power movement accelerated a process of economic and social reform, the events of 1970 did not usher in a political revolution in Trinidad (Ryan, Citation1995). Indeed, in the short term, Williams' response to the events of 1970 resulted in the diminution of Trinidadian democracy and a reduction of the space in which radical groups such as NJAC and the NBM could operate.

In May 1970, with the Black Power leadership incarcerated and the state of emergency still in force, Williams announced a programme of ‘national reconstruction’ in which he promised ‘a drastic reconstruction of the Government and its administrative arm’ (Williams, Citation1970, p. 5). However, the measures enacted only reinforced the problem of ‘one-man-ism’ his critics condemned. Reform of the executive amounted to a cabinet reshuffle in which Williams expelled the most controversial and ‘whitest members of the cabinet’ (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970a),Footnote12 replacing these with party loyalists ‘elevated … from the relative obscurity of middle-ranking positions in the party hierarchy or civil service’ (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970b). The reshuffle satisfied neither the opposition nor elements within the PNM executive who had pushed for more radical action, including fresh elections for the entire cabinet.Footnote13 Surrounding himself with ‘more of the same yes-man PNM types’ (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970c), Williams consolidated his position within cabinet and exacerbated the tendency for decision-making to rest at the top. This tendency was reinforced by Williams' scathing assessment of his government colleagues whom he dismissed as ‘no damn good … second-rate men’ (Memorandum of Conversation, Krishna Narinesingh, Citation1970); on another occasion noting that ‘all his Ministers were completely useless and that went for practically the whole of the civil service … That is why he had to take all the decisions and could not trust any of his colleagues to do so’ (British High Commission Port of Spain to FCO, Citation1972).

This centralisation of power was reflected in the reorganisation of various government ministries which saw Williams take personal responsibility for several key portfolios, including the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Development, the Ministry for Tobago Affairs and the new Ministry of National Security, which replaced Home Affairs. Embracing the Defence Force, Police Service, Coast Guard, Prisons and Immigration, the Ministry established a new National Security Council, chaired by Williams and comprising the Commissioner of Police, the Commander of the Defence Force and the Head of Special Branch. In the light of the Regiment mutiny, Williams was clearly seeking to re-establish control over the security forces, embracing the various services under his direct authority. As Trinidad's Governor-General observed, with three key ministries and ‘a long finger extended into the fourth’ (External Affairs),

The Prime Minister is running everything in the country. All decisions are being made by him and he is not listening to anyone. (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970c; American Embassy Port of Spain, Citation1970)

For some contemporary observers, these developments confirmed the view that Trinidad's political system was ‘in fact, if not in principle … closer to the Republican presidential type than to the nominal Westminster cabinet model’; or, in other terms, a ‘pussonal monarchy’ in which Williams wielded more personal control over government than any other Commonwealth Prime Minister (Espinet and Farmer cited in Parris, Citation1983, p. 172).

Such views were further cemented by the 1971 elections in which the PNM won all 36 seats in parliament, effectively confirming one-party rule. The PNM's victory was undermined by the boycott of the elections by the main opposition parties, and by a record low turn-out: a mere 34 per cent compared to 83 per cent in 1961 and 66 per cent in 1966. Reflecting increasing disenchantment with the alternatives offered by either the PNM or the fragmented opposition, the low turn-out certainly gave credence to NJAC's claims that ‘the people’ had rejected conventional politics. In the absence of an official parliamentary opposition, Williams appointed a plethora of committees and commissions which, as Parris has argued, provided a ‘mechanism for processing conflict’ (Parris, Citation1983, p. 172) while exacerbating the tendency to bypass parliament as a forum for national debate. With the ruling party enjoying unrestrained legislative powers, the result of the 1971 elections was to confirm the dominance of the PNM but to weaken the legitimacy of the government and indeed to weaken Trinidadian democracy.

As noted earlier, Williams continued to make use of emergency measures after the 1970 crisis, calling another state of emergency on 19 October 1971 in response to trouble in the labour movement. Under the emergency, many Black Power and militant labour leaders were detained, including George Weekes and Winston Leonard of the OWTU, and Makandal Daaga, Khafra Kambon and Winston Suite of NJAC. In this period too, restrictive legislative measures including the Sedition Act, Industrial Relations Act, and Summary Offences Act passed into the statute books with barely a whimper of the protest that had met the defeated Public Order Bill in 1970. These measures reduced the space in which Trinidad's non-conventional opposition groups could operate. Although NJAC sought to regroup after the release of its leadership from prison in late 1970, it was no longer able to attract the mass support it had at the height of the Black Power movement when thousands joined the almost daily demonstrations. Continued state harassment, and a refusal to engage with ‘conventional politics' diminished the threat NJAC posed to the dominant ruling party, which in fact saw a surge in membership after April 1970,Footnote14 just as numbers at NJAC rallies drastically dwindled.Footnote15

As scholars such as Parris (Citation1983) and Ryan (Citation2009) have argued, subsequent constitutional reforms in Trinidad did little to trouble the waters. Indeed the Republican Constitution, which came into effect on 1 August 1976, increased the powers of the Prime Minister, who could now, for example, have a ‘wholly selected cabinet [while] more bills could be introduced into the wholly selected Senate’ (Parris, Citation1983, p. 178). In summary, in the years following the Black Power upheavals, ‘the PNM political elite survived and reasserted itself with a vengeance’ (Ryan, Citation1995, p. 703). Williams himself remained in power until his death in 1981; the PNM until their first electoral defeat in 1986. Arguably then, it was not the legitimacy of the Westminster model that ensured Williams' survival; but rather that system's distortions. In the wake of 1970, the symptoms of Westminster executive dominance, legislative weakness, one-man-ism, one-party-ism, and winner takes all, only increased.

From Black Power to Grenada

If the Black Power movement was ultimately defeated by ‘conventional politics' in Trinidad, it nevertheless had a catalysing effect on radical politics elsewhere in the region (see Quinn, Citation2014a). In Grenada, Black Power consciousness filtered in from a number of directions, inspired by the 1968 Rodney riots in Jamaica, the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the USA, and black mobilisation in the UK. Trinidad's Black Power movement had an immediate impact on its closest neighbour, not least because several Grenadians living in Trinidad were directly involved with the movement, while others in Grenada were in contact with members of NJAC (S. Strachan, personal communication, June Citation17, Citation2014, London). In May 1970, a demonstration was held in St. George's in solidarity with the Trinidadian movement and the Grenadians in its ranks who had been detained for their part in the protests. Among the organisers of the demonstration was Maurice Bishop, recently returned from his legal studies in the UK and ‘effervescing with practical ideas about how to help the failed revolutionaries in Trinidad’ (O'Shaughnessy, Citation1984, p. 44). Among the Grenadian detainees was UWI lecturer Patrick Emmanuel, later a ‘regular fixture’ in the PRG (S. Strachan, personal communication, June Citation17, Citation2014, London), who was deported from Trinidad following his release from detention in August 1970.Footnote16 The following September, a further demonstration was organised by Bishop's National Action Front (NAF) to protest the imprisonment of Frederick Kennedy, a Grenadian student detained in Montreal as a result of the Sir George Williams University protests. These demonstrations – both involving leading figures of the future NJM – were early salvos in a popular struggle against Gairy that would gain momentum in Grenada as the 1970s progressed.

As PRG stalwart Selwyn Strachan recalls, ‘So influential was the Black Power movement in the Caribbean that it was felt necessary to get an organisation or organisations going in our territory to reflect [those] developments' (S. Strachan, personal communication, June Citation17, Citation2014, London). Many of the emergent oppositional groups in Grenada were fundamentally influenced by Black Power ideology, including the Organisation for Black Unity, NAF, Cribou, and Forum, the latter formed by Bishop after attending the November 1970 Rat Island meeting of Caribbean leftists that was a direct product of Trinidad's Black Power upheavals. These Black Power currents flowed directly into the formative organisations of the NJM, including MACE (Movement for the Advancement of Community Effort) and its successor, MAP, which merged with JEWEL to form the NJM in March 1973. Crucially, these groups were able to learn from the failures of the Black Power movement in Trinidad, whose defeat they had witnessed at close quarters. As David Lewis argues, ‘it was the failure of these [Caribbean Black Power] movements to make any inroad into the existing power structure which forced the need to overcome their ideological and organizational weaknesses' (Lewis, Citation1984, p. 62).

In developing ideas about achieving and transforming state power, the NJM drew on other currents of thought, including variants of Marxism as well as other home-grown attempts to theorise alternatives to the degraded Westminster system they opposed. As shown above, there were clear ideological sympathies between the NJM and New Beginning in Trinidad, whose ideas were nourished from the same ideological well-spring. One of the critical links here was Franklyn Harvey, who brought to the MAP ideas he had been developing from his days as a student disciple of C.L.R. James in Canada through to his extensive work with the NBM in Trinidad. These manifold influences were reflected in the NJM manifesto of 1973, a document drafted in the main by Bishop and Coard and drawing heavily on Harvey's ideas. Notably the manifesto was actually produced in Trinidad, where Bernard Coard was then based. There Coard collated the final draft, using his contacts on the island to assist in the production; some 10,000 copies were shipped from Trinidad to Grenada in the latter part of 1973 (S. Strachan, personal communication, June Citation17, Citation2014, London).

The ideological sympathies between New Beginning and the NJM are clearly evident in 1973 NJM manifesto, whose model of ‘People's Assemblies' closely echoes New Beginning's proposed ‘Assemblies of the People’ (see and ).Footnote17 Offered as a ‘new form of government that will involve all the people all the time’, the NJM's model was based on a system of Village, Parish, and Workers Assemblies, whose members would be represented in the National Assembly, the seat of national government.Footnote18 Like the NBM, the NJM stressed that power would be ‘rooted in the villages and at our places of work’, and that ‘at any time, the village can fire and replace its Council, its representative on the Parish Assembly, or its representative on the National Assembly’; ‘Together, the people of the villages and workers can throw out the whole National Assembly and put in a new one’. However the NJM's manifesto differed from the NBM's 1971 proposals in positing that the Assemblies would come into being after a transitional government had come into power. In contrast to the emphasis on self-organisation that underscores New Beginning's earlier analysis, in the NJM manifesto it is the government that ‘will have the task of starting, promoting, encouraging and generally bringing into being these Assemblies' (Manifesto of the New Jewel Movement, Citation1973). This vanguardist position was solidified by 1974 when, partly in response to increasing state repression, the NJM ‘began to reorganize itself along Marxist-Leninist lines' (Austin, Citation2010, p. 179). The tensions between the various political currents within the NJM and subsequent PRG have been exhaustively analysed elsewhere; suffice to say that the Grenada Revolution witnessed both the most extensive experiment in ‘people's participation’ to have been effected in the Commonwealth Caribbean, and the worst excesses of the cadre mentality.

While NJAC had proposed a dichotomy between ‘conventional politics' and ‘revolution’, the reality for Caribbean radical organisations was more complex. The NJM's manifesto of 1973 contained both ‘revolutionary’ proposals for people's assemblies, collective leadership, and the end of political parties; and ‘conventional’ elements in keeping with the Westminster ideal type, promising for example to restore the independence and neutrality of the civil service, and to maintain the existing system of appointments to the High Court and Court of Appeal. Prior to taking power, the NJM operated simultaneously as a revolutionary vanguard party, and as a member of the official parliamentary opposition, entering ‘conventional politics' as the dominant force in the People's Alliance in the elections of 1976. It was when these conventional avenues of opposition were deemed to be no longer viable that the revolution of March 1979 was launched.

Elsewhere in the region, some radical groups chose to enter conventional politics, forming political parties and contesting elections within the Westminster system. On the whole, this met with limited success (as evidenced for example in the electoral fates of the People's Progressive Movement in Barbados, the United Black Association for Development in Belize, or the Working People's Alliance in Guyana) (Quinn, Citation2014b, p. 34). In Trinidad, the short-lived United Labour Front (ULF) was more successful, winning 10 seats in the 1976 elections to the PNM's 24. Bringing together key figures from Trinidad's Black Power and radical labour movements, (including Raffique Shah, the young leader of 1970 Regiment mutiny), the ULF experimented with the concept of collective leadership, suggesting that some who entered ‘conventional politics' nevertheless tried to modify and democratise its forms. Finally, in a reversal of its 1970 position, NJAC announced it would contest the general elections in Trinidad in 1981. Their renewed calls for a system of ‘people's participation’ did not translate into votes; NJAC won no seats in either the 1981 elections or the local elections of 1983.

While the non-conventional opposition has not fared well within the Caribbean Westminster system – failing to overcome the entrenched divides of two-party politics, or to compete with the patronage the established parties could offer – its contribution has been to call into question the very foundations and legitimacy of that system itself. Long before academic studies picked up on the theme, groups such as Tapia, NJAC, New Beginning, and the NJM highlighted the distortions in the Westminster system as it had been implanted in the Caribbean, questioning its applicability to the conditions of post-colonial small states. If their visions of ‘revolutionary democracy’ have not been achieved, the questions they raised – fundamentally, how to achieve a more inclusionary, participatory and meaningful democracy – have far from exhausted their validity in the Caribbean today.

Funding

This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) [AH/J00488X/1].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. On the Grenada Revolution, see D. Lewis (Citation1984), G. Lewis (Citation1987), Heine (Citation1990) and Meeks (Citation1993).

2. See also Brizan (Citation1984, pp. 329–346).

3. Best was a leading intellectual in the New World group and subsequently Tapia which he formed in 1969. While these more academic groups laid some of the intellectual foundations for the critique taken onto the streets by NJAC in Citation1970, they were in turn influenced by the mass Black Power movement.

4. For a list of areas in which NJAC were represented, see Daaga (Citation1995, p. 192).

5. Riviere, a lecturer at the St. Augustine campus at the time of the protests, was incarcerated in 1970 under the state of emergency.

6. This analysis was later closely echoed in Grenada, where the NJM famously denounced ‘5-second democracy’, the confinement of politics to a special class of ‘politicians’, and the resultant alienation of the people from the institutions of ‘representative’ democracy.

7. In Trinidad, Whitehall housed the Office of the Prime Minister; the Red House was the seat of Parliament and the Senate.

8. Though the mass meetings in Woodford Square garnered most attention, smaller People's Parliaments were held throughout the island. NJAC continued to convene People's Parliaments long after the mass phase of the movement came to an end.

9. See, for example, Riviere (Citation1972). Riviere stated that the People's Parliaments

did not constitute a forum for discussing problems and finding solutions … [but instead] deteriorated into a platform where NJAC leading spokesmen raised the subject of … oppression to the status of a religion, urged blindly on by shouts of Power! Power to the People! (p. 56)

10. See, for example, Harvey (Citation1974), Look Lai (Citation1974), and Rennie (Citation1974).

11. For an analysis of the Jamesian influence on Harvey's views on self-organisation and vanguardism, see Austin (Citation2010).

12. Those removed included Minister of Home Affairs, Gerard Montano, who was ‘especially disliked by Black Power elements in the country’, and John O'Halloran, Minister of Industry, Commerce and Petroleum, damaged by his reputation for ‘graft and personal immorality’ (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970a).

13. For insights into divisions within the party, see Memorandum of Conversation: Issa Nicholls, Trinidadian Industrialist and R. B. Edward, Deputy Chief of Mission (Citation1970).

14. On the increase in PNM membership in this period, see Ryan (Citation2009, p. 411).

15. As one American embassy official observed, while a march called by NJAC on 12 December 1970 – the first since the end of the emergency – attracted between 100 and 400 demonstrators, a PNM youth rally on the same day was reportedly attended by about 5000 (American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State, Citation1970d). NJAC continued to hold small People's Parliaments throughout the country.

16. While the Grenadian government sent representatives to deal with their imprisoned nationals, the Attorney General privately admitted that ‘his visit to Trinidad was a political exercise and that the Grenada government did not really want to be landed with Emmanuel’ (Port of Spain to St Lucia Telno. Citation8, Citation1970).

17. There are clear areas of overlap with New Beginning publications in both the details and the language of the NJM manifesto. Cf. New Beginning's 31 March 1972 issue and the Manifesto of the NJM, 1973.

18. The Village Assembly would, like the NBM's Local Assembly, comprise all adult members of the locality, and would elect a small village council to implement its decisions. The Parish Assembly (like the Area assemblies envisaged by the NBM) would be comprised of ‘representatives from throughout the parish’, with each village assembly sending two delegates; Parish Councils would implement the decisions of the Parish Assembly. Workers Assemblies, ‘organised along similar lines to Village Assemblies’, would be ‘entitled to representation in the National Assembly’, and were envisaged as a counter to corrupt trade unionism. The National Assembly would be made up of ‘representatives chosen from each Village and Workers assembly, one each’, and would elect a Council to put its decisions in practice; members of the Council would work on Committees which would head up government departments (Manifesto of the New Jewel Movement, Citation1973).

References

- American Embassy Port of Spain. (1970, June 11). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State. (1970a, May 11). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State. (1970b, May 15). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State. (1970c, June 10). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- American Embassy Port of Spain to Secretary of State. (1970d, December 14). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- Austin, D. (2007). All roads led to Montreal: Black Power, the Caribbean, and the black radical tradition in Canada. Journal of African American History, 92(4), 516–539.

- Austin, D. (2010). Vanguards and masses: Global lessons from the Grenada revolution. In A. Choudry & D. Kapoor (Eds.), Learning from the ground up: Global perspectives on social movements and knowledge production (pp. 173–189). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Best, L. (1995). 1970 and 1990: Recurring crises of political legitimacy. In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 709–720). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- British High Commission Port of Spain to Foreign and Commonwealth Office. (1972, December 1). The National Archives, London.

- Brizan, G. (1984). Grenada, Island of conflict. London: Zed Books.

- Brown, D. (1995). The coup that failed: The Jamesian connection. In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 543–578). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- Daaga, M. (1995). The making of “seventy”. In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 179–199). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- Harvey, F. (1974). Rise and fall of party politics in Trinidad. Trinidad: New Beginning Movement.

- Heine, J. (Ed.) (1990). A revolution aborted: The lessons of Grenada. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Henry, P. (1984, May 30–June 2). Grenada and the theory of peripheral transformation. Prepared for the Ninth Annual Conference of the Caribbean Studies Association, St. Kitts.

- Huggins, G. (1970, April 22). The real cause. Express (Trinidad).

- Kambon, K. (1995). Black Power in Trinidad and Tobago: February 26 – April 21, 1970. In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 215–242). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- Lewis, D. (1984). Reform and revolution in Grenada, 1950–1981. Havana: Casa de las Américas.

- Lewis, G. (1987). Grenada: The jewel despoiled. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Look Lai, W. (1974). The present stage of the Trinidad revolution. Trinidad: New Beginning Movement.

- Look Lai, W. (1992). C.L.R. James and Trinidadian nationalism. In P. Henry and P. Buhle (Eds.), C.L.R. James’s Caribbean (pp. 174–209). London: Macmillan Caribbean.

- Manifesto of the New Jewel Movement. (1973). Retrieved from http://www.thegrenadarevolutiononline.com/manifesto.html

- Meeks, B. (1993). Caribbean revolutions and revolutionary theory. London: Macmillan Caribbean.

- Memorandum of Conversation: Issa Nicholls, Trinidadian Industrialist and R. B. Edward, Deputy Chief of Mission. (1970, March 18). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- Memorandum of Conversation, Krishna Narinesingh, Solicitor and John Sullivan, ECON Officer, US Embassy. (1970, June 10). Reg.59, Subject-Numeric Files 1970–1973 (Trinidad), The National Archives (NARA), Maryland.

- Memorandum of Conversation with Sir Solomon Hochoy, Governor General. (1970, June 11). Box 2630.

- Millette, J. (1995). Towards the Black Power revolt of 1970. In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 59–95). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- New Beginning (Trinidad) 5 March 1971–31 March 1972.

- National Joint Action Committee. (n.d.). Conventional politics or revolution? Belmont: Printed by The Vanguard for Education and Research Department.

- NJAC in Period of Self Analysis. (1970, October 22). Express (Trinidad).

- On the Job. (1972, May 19). New Beginning.

- O'Shaughnessy, H. (1984). Grenada: Revolution, invasion and aftermath. London: Sphere Books.

- Our New Perspective. (1972, March 31). New Beginning.

- Parris, C. (1983). Personalization of power in an elected government: Eric Williams and Trinidad and Tobago, 1973–1981. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, 25(2), 171–191. doi: 10.2307/165517

- People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada. (1981). In M. Hodge & C. Searle (Eds.), Is Freedom we making: The new democracy in Grenada (pp. 83–91). St George's: Government Information Service.

- Port of Spain to St Lucia Telno. 8. (1970, June 8). The National Archives, London.

- Quinn, K. (Ed.). (2014a). Black Power in the Caribbean. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Quinn, K. (2014b). Black Power in Caribbean context. In K. Quinn (Ed.), Black Power in the Caribbean (pp. 25–50). Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Rennie, B. (1974). Marxism-Leninism, socialist revolution and revolutionary organisation in the Caribbean. Trinidad: New Beginning Movement.

- Riviere, W. (1972). Black Power, NJAC and the 1970 confrontation in the Caribbean: An historical interpretation. St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- Ryan, S. (1995). 1970, revolution or rebellion? In S. Ryan & T. Stewart (Eds.), The Black Power revolution 1970: A retrospective (pp. 691–708). St. Augustine: University of the West Indies.

- Ryan, S. (2009). Eric Williams: The Myth and the man. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press.

- Sutton, P. (1983). Black Power in Trinidad and Tobago: The ‘Crisis’ of 1970. The Journal of Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 21(2), 115–132.

- Towards the beginning. (1971, March 5). New Beginning.

- Why our paper has not been out. (1972, March 31). New Beginning.

- Williams, E. (1970, May 3). Nationwide broadcast delivered by Dr. the Right Honourable Eric Williams. Trinidad and Tobago: Government Printery.