ABSTRACT

The African National Congress (ANC) has been an electorally dominant party in South African politics since 1994, with its vote share peaking in 2004 before falling to a low in the most recent 2019 general elections. Simultaneously, there have been much sharper declines in levels of ANC partisanship and assessments of government performance among the party’s own voters. This presents a puzzle: Why do a significant share of ANC voters continue to support a party that they do not ‘feel close’ to and do not believe is adequately managing the economy or the delivery of public goods? Based upon original qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with 111 intended ANC voters, I argue that there is a sizeable portion of ANC voters whose connection to the party is characterised by a conditional loyalty that falls short of a more thoroughgoing partisanship. The persistence of ‘thin’ loyalty alongside habitual and strategic voting for the ANC – especially among the ‘born free’ generation – has obfuscated the extent of decline in the perceived efficacy of voting and overall satisfaction with the outcomes of democratic politics.

Introduction

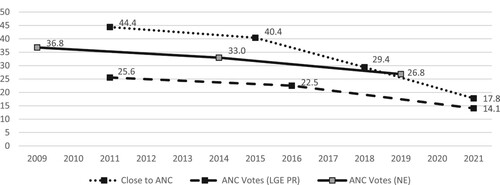

Partisanship and assessment of economic performance have long been the most prevalent explanations of voting behaviour in the broad political science literature (Downs, Citation1957; Converse, Citation1969; Fiorina, Citation1981; Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Citation2000), but these variables insufficiently account for the continued electoral support South Africans have given the African National Congress (ANC) in recent years. Although the ANC’s vote share amongst the voting age population (VAP) fell 10.0 per cent from 2009 to 2019, this shows resilience considering the sharper decline in those that ‘feel close’ to the party (see ). Among its core base of BlackFootnote1 intended ANC voters, the proportion that expressed this measure of partisanship fell 27.5 per cent between 2008 and 2018, and the share who believed that the government was managing the economy well dropped 17.7 per cent over this period (Afrobarometer, Citation2008 and Citation2018). By 2018, 24.1 per cent of intended ANC voters neither felt close to the party nor approved of their macroeconomic performance, including 36.7 per cent of those under 40 (Afrobarometer, Citation2018). Nonetheless, the ANC has maintained electoral dominance since it peaked at 69.7 per cent of the vote in 2004, securing 65.9 per cent in 2009, 62.2 per cent in 2014, and 57.5 per cent in 2019 to comfortably retain its parliamentary majority (IEC, Citationn.d.). What accounts for this ambivalence among a sizeable segment of ANC voters?

Figure 1. ANC partisanship and voting results as a percentage of voting age population, 2009–2021. Sources: Compiled from Afrobarometer Rounds (Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018, Citation2016, Citation2023), Independent Electoral Commission, International IDEA.

Based on qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with intended ANC voters, I address this puzzle by looking at how people explain their decision to vote for the ruling party. The findings suggest that existing survey instruments measuring partisanship and performance assessment do not sufficiently capture how respondents’ attitudes towards the ruling party influence their voting decisions. Many of those not displaying strong partisan identity at the time of the interview nonetheless expressed a loyalty derived from the ANC’s historical role in the liberation struggle or social pressures from their family or community. Likewise, ANC voters placed great importance on the historical delivery of service to their community rather than recent performance in the programmatic delivery of public goods. Direct experience or second-hand knowledge of the ANC’s roles in liberation and community development gave them a sense that the ANC was ‘on their side’ despite perceptions of present-day corruption and poor government performance. Even if service delivery only improved after community protests, this maintained loyalty because it could then be perceived as a party that ‘listened’ to their constituency. These insights show that, for many, voting constitutes part of a reciprocal relationship with the ANC that engenders feelings of loyalty to the party.

The qualitative analysis of voting behaviour undertaken in this article allows for differentiation between levels of political loyalty which range from partisanship to thin loyalty and residual (or habitual) voting. While these are all drivers of ANC support, they have different implications for the future of the ruling party and South Africa’s democracy. Residual loyalty and habitual voting kept the ANC afloat at the polls and lessened the trend towards abstention, but the underlying dissatisfaction makes the ANC vulnerable in the 2024 elections, especially among young people who were more likely to express a thin loyalty that was more conditional and mutable than the stronger partisan identity of older generations. The declining sense of reciprocity felt among younger generations of Black South Africans towards the ANC has weakened their sense of duty to participate in the electoral process. This has driven potential voters to opt out of electoral politics. Furthermore, the same voters are more likely to express low estimates of political efficacy resulting from corruption scandals and the seeming inevitability of South Africa’s dominant party-system. In sum, this confluence of factors presages growing numbers of non-voters in future elections.

This article begins by discussing the concepts of partisanship and loyalty and noting the qualitative differences in levels of loyalty among those who may have the same voting behaviour, before explaining the methodology used to gather data. Data gathered from in-depth interviews with ANC voters are then utilised to delineate partisanship (strong loyalty), strategic support based upon the incumbents' advantages in the delivery of public goods (conditional or ‘thin’ loyalty) and a habitual support among those who have become more critical of the ANC (residual loyalty). After describing the differences between these levels of loyalty, the conclusion discusses the implications of this for politics in South Africa and other post-liberation contexts.

Degrees of party loyalty

Partisanship has long been conceptualised as a primary determinant of voting behaviour because it provides informational short cuts giving voters easier decisions come election day. It was seen as a persistent psychological attachment predominantly formed during early years of political socialisation which was strongly influenced by politically active parents (Downs, Citation1957; Converse, Citation1969). While Dalton (Citation1984) argued that partisanship had decreased in advanced industrial democracies due to greater education and media access, it has subsequently become apparent that party identity is still a salient factor which links social, economic, or ideological groups to specific political parties (Gerber & Green, Citation1998; Groenendyk, Citation2013). In contrast with studies which collapse the concepts of partisanship and loyalty into ‘partisan loyalty’ (Mummolo et al., Citation2021), this article makes a distinction between the two concepts based on inductive reasoning derived from the qualitative data presented. While some scholars working within Hirschman’s (Citation1970) framework of exit, voice, and loyalty have operationalised loyalty as the behaviour of not switching one’s vote (Dassonneville et al., Citation2015), it is more usefully seen as a psychological variable that influences individual decisions about whether to exit or exercise voice. The degree of loyalty depends on an individual’s identification with the object of loyalty and the material and psychological investment they have made (Dowding et al., Citation2000, p. 477). Applied to party politics, individuals with greater historical attachment or personal investment (in terms of clientelist relationships and shared identities) will face higher ‘costs’ if they decide to abstain or change allegiances. Such loyalty makes voters more likely to silently continue their support or voice their discontent while still voting for their chosen party. This conceptualisation of loyalty helps to explain how voting decisions are conditioned by historically rooted and ongoing relationships between political parties and their supporters. Rather than seeing loyalty as a discrete category, this allows us to look at how differing levels of loyalty to a political organisation may impact voting decisions, ranging from a strong partisanship to ‘thin loyalty’ or residual loyalty.

In quantitative work on South African partisanship, researchers rely on survey questions that ask if respondents ‘feel close’ to a particular party (Gordon et al., Citation2018; Schulz-Herzenberg, Citation2019a). While this may reasonably approximate partisanship at the time of the survey, it does not necessarily capture the more contextual attachments that may bind ‘loyal’ voters during elections. Indeed, one of the above studies acknowledges that ‘these questions are considered an effective method of measuring political partisanship because they make no direct reference to long-term loyalties and, thus, make it easier for the respondent to express attachment’ (Gordon et al., Citation2018, p. 167). However, to the extent that long-term loyalties affect voting behaviour it makes sense to treat them differently in qualitative research, especially considering the contextual components of loyalty. While strong versions of loyalty such as partisanship are more likely to be expressed throughout the election cycles and elicit participation in party structures, thinner loyalties may only drive political behaviour at election time.

Research design

To draw conclusions about the determinants of voting behaviour I conducted semi-structured interviews in seven electoral wards in Black residential areas in the municipalities of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni, eThekwini and Rustenburg between 2017 and 2018, a period between elections which saw an accelerated decline in ANC electoral support and partisanship as more of the ‘born free’ generation entered the electorate (see also and ).

Table 1. Political differences among generations of Black South Africans, 2022.

This yielded 111 research participants who intended to vote for the ANC in the next elections, including 36 women and 75 men.Footnote2 The overall research design aimed to understand the reproduction of ANC loyalty among Black voters in the geographic and demographic context where it was ‘least likely’ due to greater challenges from opposition parties and voter apathy. Research sites focused on peri-urban areas which represent a large proportion of the ANC’s Black voter base but are less likely to vote for the ANC than their rural counterparts. In terms of age distribution, 34 interviewees were born between 1942 and 1975, 43 were born between 1976 and 1993, and 34 were ‘born free’ from 1994 to 2000. As such, this sample is skewed towards the younger ANC supporters who are of greater theoretical interest because of the ‘youth bulge’ which has greater potential to affect future election outcomes with their sheer numbers, and greater propensity to abstain or vote for opposition parties (Schulz-Herzenberg, Citation2019b; Paret & Runciman, Citation2023). Those who came of age after 1994 and vote for the ANC are therefore key to understanding the reproduction of party loyalty moving forward, especially among the ‘born free’ generation that has no experience of the apartheid government.

The municipalities chosen include the three largest Black populations and the wards selected exhibit significant ethnolinguistic variation, ranging from IsiZulu speakers in eThekweni to Setswana residents and Xhosa migrant workers in the mining regions of Rustenburg, a large population of Sepedi-speaking migrants from Limpopo Province in Ekurhuleni, and a blend of South Africa’s languages in Johannesburg. Research sites within each municipality contained a mixture of formal and informal housing and are considered working class areas struggling with high unemployment rates and service delivery issues typical of the living circumstances of the majority of Black South Africans. Research participants were selected from every third or fourth house while walking through the selected neighbourhoods, and group interviews were conducted in locations where willing participants were gathered. These informal focus groups added depth to the data by capturing debates between respondents who had different viewpoints, reducing researcher effects and providing insight into how politics are discussed within social groups (Stanley, Citation2016).

Historical memory and ANC partisanship

Loyalty comes from emotional investment in a particular organisation over time, leading us to strongly ‘identify with something to the extent that it is tied to our personal history’ (Dowding et al., Citation2000, p. 477). Such loyalty to the ANC is understandable, given the centrality of the party in the decades-long liberation struggle and subsequent transition to democracy. Across the research sites where community interviews were conducted, ANC voters cited the party’s liberation credentials and the legacy of Nelson Mandela as being important reasons to vote for the party. They saw the former ANC President as symbolic of an ANC that was demonstrably improving the lives of Black people.

Most older voters expressed loyalty to the ANC because of the positive changes they had witnessed in their lives, and Nelson Mandela was frequently mentioned as an important symbol that represented the ANC’s role in the liberation struggle. The improvements in social status, freedoms and opportunities they experienced in their daily lives solidified a strong loyalty that led one 72-year-old female interviewee to state ‘I will vote for the ANC, we will die with it’. For Black people who lived under apartheid, the end of legal oppression and discrimination was a seminal change in their lives which was inextricably linked to the party that came to power in the first democratic elections in 1994:

To me, after the ANC took over the government, it’s not the same as before. Before it was very tough, and then we could see that time. We saw many things happening, like those days things were hectic, I had to carry my ID, we used to call them reference book, I had to carry it in the pocket.

For others, including one 62-year-old man, the material improvements provided by the ANC government were more important than the party’s role in the liberation struggle:

The main reason I’ve supported ANC is because of the changes they have brought. Because of Mandela we have houses even though they’re not here, but in some areas we have seen changes, in schools, electricity. Every time there’s vote, an election, I’m going to vote ANC.

There’s no party which I do wish to vote for, just for ANC, ANC, ANC, but it’s not inside my heart … You see now, the person who was quite responsible is Nelson Mandela. That was the only president who was not doing things for his own [benefit]. Now, people they go for posts for which they want money, not because they’re willing to help people. They don’t want to help the people.

In each of the areas where I conducted interviews, respondents told me that the ANC paid special attention to mobilising this constituency for electoral support. In addition to providing free transport to the polls, local ANC branches distributed blankets or food parcels to elderly people in their community. In Inanda and Ntuzuma this appeared to be a regular practice, with interviewees mentioning that every December the ANC would hand out food baskets as part of a ‘Granny’s Christmas’ gift. For the most part, these forms of clientelism were viewed benignly since they were directed towards a deserving segment of the community, with some voters seeing it as evidence that the ANC was providing more than other political parties. This use of resources by the ANC facilitates a strong turnout among the older generations of Black South Africans who exhibit a strong partisan attachment to the party of liberation. They were able to readily compare their experiences as adults living under apartheid with the governance of the ANC led by President Mandela and those who succeeded him, deriving a sense of connectedness with the ruling party which contributed to its electoral dominance.

Youth partisanship and the intergenerational transmission of loyalty

While the loyalty among older Black South Africans is not surprising, some of their younger counterparts who only reached voting age after 1994 also mentioned historical reasons for supporting the ANC even though they had less direct experience with the apartheid regime. They were cognisant of the gains that had been made since 1994 and saw that as a compelling reason to vote for the ANC. A 23-year-old man in Inanda explained the reasons why he cast his first ballot for the ANC in 2016:

You know what, I chose ANC because ANC used to say to our grandpas – cause they fight for us, for freedom. I’m not going with racists [DA], ne? So in this political time we can see ANC helps us because now we can able to talk to [white] people just like you. We don’t even say ‘your skin, my skin’, but now we take other people friendly, we talk, we do everything. So that’s why I vote for ANC because I can say it’s helped us.

I supported ANC because most people they can go wherever they like. You can enter any toilet that you want. But, during apartheid most of us, the Black people, they are not supposed to get inside the white people’s toilets you see, so that is why I voted it.

The loyalty of young people towards the ANC was driven not only by an impersonal knowledge of the history of the liberation movement, but by familial connections with those who participated in the freedom struggle. For instance, a 31-year-old man in Soweto explained

the main reason we’re supporting ANC is because ANC has been a long time. Even our grand grand mother, grand grand father have been busy supporting ANC. Even if the ANC sometimes is doing something we don’t like, we’re still going to support them.

The historical achievements of the ANC were more important than recent performance or the expectation of future social or economic gains in the minds of these young Black South Africans. This is not blind loyalty but informed by a political subjectivity that prioritises a long view of history in determining what is politically ‘good’ when making decisions within a moral economy of elections (Cheeseman et al., Citation2021). Familial ties with the ANC elicited a high degree of loyalty to the party, making it unthinkable for young black South Africans to be ‘disloyal’ to the party because it would challenge their self-understanding in relation to their family members. A 29-year-old man in Inanda exemplified this kind of loyalty:

Yeah you have to go for ANC, this is compulsory, to us over here in Inanda it’s compulsory to go for the ANC, because of history. Now they’re taking advantage of that [through corruption] … I will be voting for ANC, because now, know why? Not just because they do much better, but because my uncles died for that, it’s still stuff that touches me. When I walk in the dining room there, the sitting area, I see their pictures of the ANC, and they just want[ed] to see for us to get the freedom … .So now I can’t just turn my back.

Gerber et al. (Citation2003) have argued that prior voting behaviour is a better predictor of future voting behaviour than partisan identity, suggesting that habit formation is a powerful factor influencing voting decisions. There is good reason to believe that these early experiences of youth voting for the ANC help to engender a strong sense of partisanship and loyalty that influences future voting decisions. As one 22-year-old man explained:

Firstly, when I was voting I just voted, for ANC. And then the second time I saw a lot of improvements then I see that ANC is for people, that’s why I’m voting for ANC. From now on I won’t change. I won’t. Even if they are just doing what they are doing I won’t change. They say, once an ANC member you will be an ANC member until you die, if you really really love ANC.

Conditional loyalty and the delivery of public goods

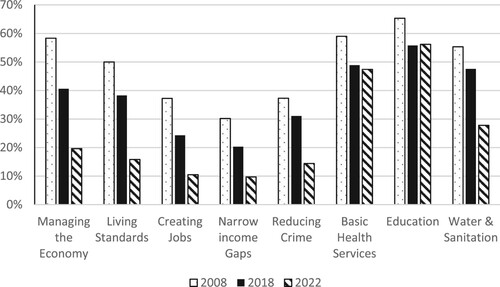

In contrast to the affective dimensions of partisanship discussed above, many strands of literature argue that voters make their electoral decisions based upon retrospective evaluations of incumbent performance (particularly in terms of the economy) and punishing or rewarding them accordingly (Fiorina, Citation1981; Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Citation2000). In the African context, Bratton et al. (Citation2012, p. 47) argue that voters primarily vote for parties they believe will further their future economic interests, basing this decision on ‘rational assessment of actual government performance at macroeconomic policy management’. Indeed, studies of dominant parties in Southern Africa and beyond have highlighted their control over bureaucratic institutions as an important factor in allowing them to strengthen their position, because of the control (and credit) it gives them in public goods delivery (de Jager & du Toit, Citation2013). These accounts suggest that, from a position of incumbency, parties such as the ANC have the advantage of being able to point to their experience in government managing the economy and delivering services to the population. Looking at subjective evaluations of government performance in South Africa, there is a strong correlation between positive assessments of government handling of economic management and the provision of public goods and voting for the ANC (). However, approval ratings among intended ANC voters for delivery of these public goods is relatively low and fell significantly from 2008 to 2018 before collapsing in the 2022 survey. This change in the attitudes of voters indicates that an increasing portion of ANC voters have become less satisfied with government delivery of public goods but continue to support the party at the ballot box.

Figure 2. Black ANC voters who believe the government is handling public goods ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ well. Source: Afrobarometer (Citation2008, Citation2018, Citation2023).

Many ANC voters expressed a ‘thin’ loyalty conditional on the continued distribution of public goods to their communities by the ruling party. The distribution of social welfare grants in South Africa is one ANC’s major accomplishments in office, reaching millions of South Africans every month. These benefits were mentioned by some interviewees as a reason to turn out and vote for the ANC in accordance with recent analysis (Seekings, Citation2019, pp. 20–21; Patel et al., Citation2019, p. 6). This was evident among some of the young women who managed by using child support grants distributed by the state. For example, two women aged 22 and 35 independently said they voted for the ANC because they credited the party with providing this grant alongside free education for their children. In addition, a 21-year-old woman explained that she was afraid to vote for another party for fear of losing this critical part of her livelihood. Their loyalty was directed towards the ANC because they thought it was the only party that had done anything substantial to improve their lives, but it was conditional on the continued receipt of these government benefits.

For most men and women interviewed, social grants were seen as only one facet of government delivery, as expressed by a 30-year-old woman:

I am happy with the current political party. It has delivered what they have promised, as they have built us RDP houses and I am happy. I love Zuma as I have a grant and my conditions have changed for the better.

ANC has managed to change this area because this area was, it was worse than this. We didn’t have tar roads. Everything was mixed up, we didn’t even have electricity … So ANC, although many people [have issues with them], ANC made changes in this area. They have done the most – electricity, whatever – they have done almost everything here because it used to be a disaster here.

Incumbency and relations of reciprocity

Despite the support that many ANC voters expressed for opposition parties like the DA and EFF, there was a clear differentiation made between a ruling party that has shown itself willing and capable of making incremental improvements to living conditions of poor and Black South Africans, and opposition parties which have not concretely demonstrated a commitment to local development. Since opposition parties were not seen as viable or trustworthy proponents of local development, the ANC continued to dominate the preferences of young voters, as one 21-year-old woman made clear:

According to me it is the best political party because most of the things that have happened are all about ANC. Even the electricity, the tar road is all about ANC so I would just go with ANC because I see developments because of the ANC. So I think the other political parties they’re just benefiting, they just want to benefit.

There’s streetlights there, that’s ANC, and now they’re doing a major project on the [water] pipe, you see? Even though there’s corruption in this thing with the RDP houses, some of the people they’re already living in those houses there, they’re slowly reaching out. There’s something, there’s difference … I don’t know what time it will take, at least they’re doing something to take the initiative.

Even though these improvements in service delivery frequently come after protests, the councillor and the ANC are seen as the only interface through which progress can be made. As the only party offering solutions, dissatisfied residents would rather repair their relationship with the ruling party than abandon them. A 36-year-old woman in the informal settlement of Mmadihlokoa explained why she was willing to give the ruling party another chance: ‘They have come to the community, they have spoken to the community, they apologised and they promised that they would listen to the community’.

The idea that the government must be pushed to make improvements was common among interviewees, including those that intended to abstain or vote for opposition parties. So even though Protea South has been a hotbed of protests over service delivery, ANC support has remained strong and their support among registered voters grew from 46.3 per cent to 51.5 per cent between 2014 and 2019 in one of the rare wards where turnout increased. A 29-year-old man who had participated in the protests there explained why he voted for the ANC: ‘I think so far they’ve given us improvement, because they listen to what we are crying for and they’ve given us that’. For ANC voters, protesting while voting for the ruling party makes sense because they are both ways in which communities can engage with the party that oversees the distribution of state resources. As one 18-year-old man in Winnie Mandela who intended to cast his first ballot for the ANC reasoned: ‘If we want to be responded we have to take legal actions like strikes, that’s when they realise that we are serious about what we want. So we have to force them in order to deliver our services’. Even though his family was still waiting for an RDP house, he explained that he would vote for the ANC because it had extended electricity to the community. This attitude helps to explain Booysen’s (Citation2011) observation that protesting communities still largely vote for the ANC.Footnote3 If improvements are made after protests it is seen as evidence that the ANC and its representatives are ‘listening’ and responding to the needs of the community members. In this way, cycles of protest and service delivery extension in informal settlements such as Protea South and Winnie Mandela may help form relationships of reciprocity with the ANC that produce a ‘thin’ loyalty among voters.

Habitual and strategic voting

The ANC voters described above displayed a loyalty to the party based on its role in the liberation struggle and the extension of public services in the post-apartheid era, giving them faith the party would eventually satisfy the needs of its Black constituency. However, for a significant number of younger ANC voters their support was more habitual and ambivalent. A 35-year-old regular ANC voter explained: ‘Normally I voted for ANC, not because it’s something special just because I don’t want to be different from other people. So I just have to go with what other people are doing’. He said ‘I’ve already voted three times and I haven’t seen anything’, leading him to ultimately show uncertainty about how he would vote in the next election. This social pressure from older generations was commonly cited as a motivation to vote for the ANC, as a 36-year-old man explained: ‘When you are born here in the township, you grew up your whole family supporting ANC. You don’t have other alternatives’. This led to a habitual support for the ANC which a 26-year-old man likened to ‘when you grow up going to church, you grow up going with your parents, [but] you don’t know the reason why you’re going to church, it’s just like that’. For this segment of young people, the ANC still evoked some loyalty, but it was evidently weaker than those quoted earlier in this chapter who exhibited either thick or thin loyalties. Their attachment to the ANC had been eroded by corruption scandals and a belief that the party had regressed in recent years. This residual loyalty was made clear when I spoke with an 18-year-old who had not yet had the opportunity to vote in an election:

It is the political party I’m used to, I would vote for. But technically it would be just for the work of voting, not because I’d be expecting any change or anything, just for the sake of voting, practicing my right since it was fought for by blood and tears … The ANC of today is not like the ANC of back in the day.

The loyalty of young ANC voters interviewed for this study was clearly challenged by perceptions that the government was not doing enough to improve the living conditions of those living with inadequate housing, jobs, and service delivery. Despite these criticisms of the ANC, such voters intended to support them in the next election, but their attitudes suggest that the ANC’s hold on the ‘hearts and minds’ of many voters is tenuous, and that the appetite for democracy is declining as people become frustrated with the perceived lack of efficacy in voting. These critical assessments of ANC voters do not bode well for future electoral turnout, as younger voters become disillusioned and older voters play a diminished role in promoting the importance of voting in their communities. In 2018, almost half of intended Black ANC voters said they were ‘not at all’ or ‘not very’ satisfied with how democracy works in South Africa, and slightly more were ‘willing’ or ‘very willing’ to give up regular elections for housing and jobs (Afrobarometer, Citation2018). These attitudes were apparent in several interviews with younger ANC voters who did not see positive outcomes coming from politics:

I vote ANC because if I don’t vote ANC it’s the EFF comes into power, they are going to be sabotaged by the ANC members in parliaments. They cannot do what they supposed to and then come next election they will fail us. It’s better to support the ruling party. (38-year-old man)

What I see at the TV and on the media, and in parliament is that everyone is fighting. Everyone needs a chair to rule, some they promise but they don’t keep their promises … Eish, I am so confused now, because yes, I have voted before but now things are not the same like before. We used to vote before, but things are not the same as before. (31-year-old man)

The perceptions of the inefficacy of electoral politics expressed above led young people to strategically support the ruling party because they felt that their votes would be ‘wasted’ if they supported an opposition party. A 27-year-old male resident of Mpumalanga laid out the dilemma:

How are [opposition parties] going to help us, because they don’t have money. Only ANC’s ruling. They can talk, but end of the day ANC has power because they have money … If you’re voting for another party you’re wasting your vote – they’re not going to win, because ANC’s dominating.

Conclusions

This article examined the most prominent reasons South Africans expressed during interviews explaining why they voted for the ANC. On an individual level, voting is a complex decision influenced by a myriad of psychological, evaluative, and strategic considerations, but patterns in the qualitative data emerged which point towards the centrality of loyalty in preventing ‘exit’ from the ANC orbit. There was a ‘thick’ loyalty among those who will continue to vote for the ANC even though they have grievances with the party’s delivery of services or corruption of party leaders. For younger generations, there is familial and social pressure in these communities that the ANC is part of them, so it is their duty to turn out and support them during elections. This is synonymous with the political science concept of partisanship as an enduring attachment to a political party that is unlikely to change throughout one’s life cycle (Muirhead Citation2013, p. 253). It represents a commitment to the organisation exemplified by a 28-year-old man I spoke with in Umlazi:

I’d find it quite difficult to vote for another party, I’ll vote for ANC. I mean with ANC we came a long way so we cannot now, just because of some mistakes of individuals, then move away from the party. You better fix what you have, because if you keep moving form one party to another party then it’s just a no-moving train.

However, the conceptualisation of loyalty confirmed in this paper is nuanced and recognises the possibilities for it to vary in strength over time and across individuals. It is also consistent with other accounts of decision making that point towards a moral economy where politicians are judged by their abilities to deliver benefits to the population in a manner which is deemed to be ‘virtuous’(Cheeseman et al., Citation2021). The ‘thin’ loyalty identified among young people in this article is characterised by strategic and affective considerations regarding the ANC’s role in improving their material living conditions. They have been primed from a young age to support the party, but their voting behaviour is conditional on feeling that the government has upheld a reciprocal relationship between the ruling party and working-class Black communities. The ANC has a distinct incumbent advantage in this respect because it is seen as the only party that has concretely delivered social grants and local development projects in the past. Even when the level of development is seen to be insufficient, many remain loyal to the party because, as a 39-year-old woman stated, ‘it used to do good things’ and retains some moral legitimacy in the eyes of voters.

Since 2019, perceptions of service delivery have been impacted by electricity ‘load-shedding’, and the ANC government has faced additional criticism for perceived unfairness in the distribution of Covid-19 relief assistance (Galvin et al., Citation2023; Mpako & Ndoma, Citation2023). While this has sharply accelerated the downward trend in government approval ratings and partisanship (see ), this is likely to have a muted effect on ANC fortunes in the 2024 elections due to persisting thin loyalty towards the ruling party. Additionally, lingering uncertainty about the viability of opposition parties among habitual or strategic ANC supporters will more likely drive these potential swing voters to abstention rather than shifting votes to competing parties (Schulz-Herzenberg & Mattes, Citation2023).

In politically polarised countries voters are reluctant to support a party unlikely to win a majority, and thus far South Africa has followed a cross-national pattern where ruling parties maintain electoral support because voters are wary of the consequences of defection to alternative parties (Carothers & O’Donahue, Citation2019, p. 5; Svolik, Citation2019). The dominant ruling parties in Namibia, Mozambique, and Botswana are likely to benefit from incumbency and a ‘liberation dividend’ when they hold their respective national elections in 2024 (Paret & Runciman, Citation2023). However, the thinning of loyalty will increase the possibility of swing voters moving from ruling to opposition parties if the latter are able to demonstrate viability in the minds of voters. For example, Namibia’s ruling party’s loss of power in key municipalities in the 2020 local elections may give opposition parties enough credibility to sway young people possessing ‘thin’ or ‘residual’ loyalties. The South African case suggests that liberation parties may be more vulnerable than their current electoral successes indicate, because they are propped up by weaker forms of loyalty which are increasingly fragile among younger generations. Rather than a slow transition to competitive multi-party elections, these electoral contexts could soon see a tipping point which brings about unexpectedly rapid changes in voting behaviour as generational changes manifest themselves in the electorate.

Ethics statement

Verbal consent was given by all participants and research was approved by the Social Sciences, Humanities, and Education Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto (#32775).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor Andrew Wyatt and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable input, as well as Charles Larratt-Smith and Luke Melchiorre for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Black’ is the racial category used in contemporary survey data to refer to people of African descent. While such categories should not be reified, they speak to the real-world geographic, economic, and political divisions and inequalities in post-apartheid South Africa.

2 While this sample may be less representative of the views of female ANC voters, the themes of voting behaviour discussed in this paper are relatively consistent across gender lines and quotations from women are included to illustrate each of the different kinds of loyalty.

3 Although Runciman, Bekker, and Maggott’s (Citation2019, p. 13) exit-poll study showed protesters were less likely to vote for the ANC than non-protestors, they still found that the ANC received more support among them than any other party.

References

- Afrobarometer Data. (2008). South Africa, Round 4. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Afrobarometer Data. (2011). South Africa, Round 5. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Afrobarometer Data. (2016). South Africa, Round 6. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Afrobarometer Data. (2018). South Africa, Round 7. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Afrobarometer Data. (2023). South Africa, Round 8. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Booysen, S. (2011). The African National Congress and the regeneration of political power. Wits University Press.

- Bratton, M., Bhavani, R., & Chen, T. (2012). Voting intentions in Africa: Ethnic, economic or partisan? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 50(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2012.642121

- Carothers, T., & O’Donahue, A. (2019). Introduction. In T. Carothers & A. O’Donahue (Eds.), Democracies divided: The global challenge of political polarization, 1–14. Brookings Institution Press.

- Cheeseman, N., Lynch, G., & Willis, J. (2021). The moral economy of elections in Africa: Democracy, voting and virtue. Cambridge University Press.

- Converse, P. (1969). Of time and partisan stability. Comparative Political Studies, 2(2), 139–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041406900200201

- Dalton, R. (1984). Cognitive mobilization and partisan dealignment in advanced industrial democracies. The Journal of Politics, 46(1), 264–284. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130444

- Dassonneville, R., Blais, A., & Dejaeghere, Y. (2015). Staying with the party, switching or exiting? A comparative analysis of determinants of party switching and abstaining. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 25(3), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2015.1016528

- de Jager, N., & du Toit, P. (Eds). (2013). Friend or foe? Dominant party systems in Southern Africa: Insights from the developing world. UCT Press.

- Dowding, K., John, P., Mergoupis, T., & van Vugt, M. (2000). Exit, voice and loyalty: Analytic and empirical developments. European Journal of Political Research, 37, 469–495.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 65(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/257897

- Ferree, K. (2010). Framing the race in South Africa: The political origins of racial census elections. Cambridge University Press.

- Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press.

- Galvin, M., Kim, A. W., Bosire, E., Ndaba, N., Cele, L., Swana, S., Kwinda, Z., Tsai, A. C., & Moolla, A. (2023). Community Perceptions and Experiences of the South African Government's Response to the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Social and Health Sciences, 18 pages. https://doi.org/10.25159/2957-3645/12601.

- Gerber, A., & Green, D. (1998). Rational learning and partisan attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 794–816. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991730

- Gerber, A., Green, D., & Shachar, R. (2003). Voting may be habit-forming: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 47(3), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00038

- Gordon, S., Struwig, J., & Roberts, B. (2018). The hot, the cold and the lukewarm: Exploring the depth and determinants of public closeness to the African National Congress. Politikon, 45(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2017.1357913

- Groenendyk, E. W. (2013). Competing motives in the partisan mind: How loyalty and responsiveness shape party identification and democracy. Oxford University Press.

- Hirschman, A. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

- Independent Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC). (n.d.). Election results. https://www.elections.org.za.

- International IDEA. “Voter Turnout Database.” https://www.idea.int.

- Lewis-Beck, M., & Paldam, M. (2000). Economic voting: An introduction. Electoral Studies, 19(2-3), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(99)00042-6

- Mpako, A., & Ndoma, S. (2023). South Africans praise government’s COVID-19 response but express concern over corruption, find pandemic assistance lacking. Afrobarometer Dispatch, 752.

- Muirhead, R. (2013). The case for party loyalty. Nomos, 54, 229–256. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24220179

- Mummolo, J., Peterson, E., & Westwood, S. (2021). The limits of partisan loyalty. Political Behavior, 43(3), 949–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09576-3

- Paret, M., & Runciman, C. (2023). Voting decisions and racialized fluidity in South Africa’s metropolitan municipalities. African Affairs, 122(487), 269–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adad010

- Patel, S., & Bryer, R. (2019). Monitoring the influence of socio-economic rights implementation on voter preferences in the run-up to the 2019 national general elections. Centre for Social Development in Africa, University of Johannesburg.

- Runciman, C., Bekker, M., & Maggott, T. (2019). Voting preferences of protesters and non-protesters in three South African elections (2014–2019): Revisiting the ‘ballot and the brick’. Politikon, 46(4), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2019.1682763

- Schulz-Herzenberg, C. (2019a). The decline of partisan voting and the rise in electoral uncertainty in South Africa’s 2019 general elections. Politikon, 46(4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2019.1686235

- Schulz-Herzenberg, C. (2019b). The New electoral power brokers: Macro and micro level effects of ‘born-free’ South Africans on voter turnout. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 57(3), 363–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2019.1621537

- Schulz-Herzenberg, C., & Mattes, R. (2023). It takes two to toyi-toyi: One party dominance and opposition party failure in South Africa’s 2019 national election. Democratization, 30(7), 1313–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2228710

- Seekings, J. (2019). Social grants and voting in South Africa. CSSR Working Paper, 436.

- Stanley, L. (2016). Using focus groups in political science and international relations. Politics, 36(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395715624120

- StatsSA. (2022). Census 2022 statistical release. https://census.statssa.gov.za.

- Svolik, M. (2019). Polarization versus democracy. Journal of Democracy, 30(3), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0039