ABSTRACT

By longitudinally tracing India’s top political Twitter trends for 2019, our study shows that discursive framing of political leaders is another approach to digital politics. We show that political discourse on digital platforms in India (a) revolved around personalities and (b) hashtags projected political personalities using discursive frames that allow personal subjective interpretations to emerge in resonance with an individual user’s worldview. This is interpreted as a form of political distortion enabled by digital platforms, shaping the perception of political leaders.

How do we read the narratives on social media platforms like Twitter? This is one of the central questions in studies of digital politics. The interest primarily lies in understanding how discourses are curated and whether they reflect public sentiments accurately. Various studies have examined the gap between social media content and public attitudes. The mainstreaming of polarising content is a case in point (Borah & Singh, Citation2022). Two other important topics have attracted scholarly attention. Firstly, research has identified incentive structures that attract widespread attention towards a particular topic or behaviour (see the ‘like economy’ concept developed Gerlitz and Helmond (Citation2013)). Dash et al. (Citation2022) analysed ‘influencers’ on Twitter to show their partisan engagement in return for in-kind rewards such as increased retweets and follower counts. A second area of research is automation. Neyazi (Citation2017, Citation2020) traced the rising political polarisation on social media and cited automation’s role in creating polarising discourses. These enquiries over time have suggested that discourses on social media platforms can be deceptive in the sense that what might appear trending and publicly curated could be otherwise, riding on pre-determined human or computational mechanisms. Strategies to mediate a discourse using descriptive phrases are linked to these phenomena.

The manipulation of online sentiment is an emerging phenomenon in India, a country with easy and relatively cheap access to the internet. Methodological innovations have also confirmed this by showing large-scale manipulation of Twitter trends and the creation of a controlled discourse, especially during elections (Jakesch et al., Citation2021). Karthik et al. (Citation2020) similarly speak to this point with a study of a specific campaign in the state of Tamil Nadu. Such effects of discourse mediation have also been observed in cases beyond elections, such as in the discourse on COVID-19 (N. Jain et al., Citation2021).

Twitter’s prominence was noted during the 2014 General Elections. Ahmed et al. (Citation2016, p. 1071) and Jaidka and Ahmed (Citation2015) showed that the use of Twitter in Indian elections was sophisticated: new parties used it for ‘self-promotion and media validation’ whereas established parties used it to further their offline strategies. They also showed that the winning party’s electoral success correlated with them engaging voters through Twitter (as one of the factors). Ahmed et al. (Citation2017) further argued that Twitter had a ‘levelling’ effect on electoral politics in India since it enabled fringe politicians (who otherwise received low media attention) to reach out online, interact with people, and mobilise. In fact, there was a clear shift in Modi’s campaigning strategy on Twitter between 2014 and 2019 (Tulasi et al., Citation2019). While many previous studies focus on explaining the processes that enable a mediated discourse, this study asks how is a ‘mediated discourse’ expressed and what does it imply for digital politics?

This mediation of political discussions (Jungherr, Citation2015) suggests the creation of an alternative (or imbalanced) version of politics in the digital sphere that emphasises certain sides of the debate while suppressing the others. Besides emphasis or de-emphasis, mediation may also imply creating or manufacturing discourses altogether. For instance, the spread of digital disinformation – a case in point, where discussions are deliberately initiated using false information (Hindman & Barash, Citation2018; Linvill & Warren, Citation2020; Bhatia & Arora, Citation2024). With a deliberately created false basis of discussion, the emergent discourse is bound to produce political distortion. Essentially, this type of research enquires into topics that digital politics’ participants are preoccupied with, and assumes the discussion is mediated in some way by some entity. We build upon this idea and discuss a form other than spreading disinformation or hyping tangible developments. We show that mediation also includes presenting political personalities in a discursive frame where figures are associated with distinctive but imaginary characteristics, in the sense that these characteristics do not exist in literal terms, nor express something tangible nor share a definitively understood meaning. Instead, they derive meaning and tangibility from the user’s personal interpretation of this characteristic and how they see this shared between themselves and the political figure. This feature of mediation therefore does not impose an identity upon the user, instead the figure takes the identity that the user wants them to be seen in or can relate to. Our view draws inspiration from Fitzgerald’s (Citation2013) findings on how people contextually interpret the meaning of the term ‘political’, a rather mundane word assumed to have a common universal definition.

This proposed conception of associating a personality with a certain characteristic, entity, property, or attribute ride on the centrality of imagined identities in constructing an individual’s persona within digital spaces. This persona is far from a mere reflection of a person on screen: instead, it is a deliberate and curated creation of an identity and story for the public based on selective information sharing, presentation, and interaction hoping to weave a cohesive and attractive online presence. Practically, this may imply personal branding, influencing, and showing their alignment with certain communities. Such similar actions are loaded with ‘value’ to mean that online projections have an intention behind them.Footnote1 Such projections affect how people perceive them. Shome et al. (Citation2023) presented a case to sketch the nuances of creating these perceptions. They showed that nationalism could be framed on the intersecting lines of ideology and gender using visual communication on social media. Populists on social media, for instance, are seen appealing to people’s emotion by often communicating aggressively. This is interpreted as promoting a feeling of unity and in-group cooperation within their supporters (Cervi et al., Citation2021). This act of deliberate opposition creates an impression of genuineness and unmediated exchange, appealing to followers who value straightforwardness and openness. This approach can be seen in the campaigns of a range of leaders including Modi, Farage, Wilders, and Trump (Gonawela et al., Citation2018). We posit that their association with a discursive characteristic serves a similar contextually relevant purpose and take this up in the discussion section.

We propose three related research questions, two analytical and one interpretive. One, what share do political personalities occupy within digital politics in India? Two, how are political figures projected within digital politics in India? Three, how do these projections theoretically complicate the disciplinary understanding around conducting digital politics?

By conducting a multi-level coding analysis of top Twitter hashtags for the Indian election year 2019, we show that, firstly, personalities remain the central subjects of the trending Twitter discourse compared to non-personality themes. This buttresses the arguments pertaining to growing levels of celebritisation in Indian politics (Rai, Citation2019). Leideg (Citation2016) located the reason for the emergence of personalities in: the high degree of similarity between Indian political parties and their promises, the construction of a larger-than-life public image of leaders and using such images as the pivot for staying in power as a strategy. This focus on personality helped Modi remain in power and keep a tactical distance from the party’s image and negative connotations that might have. Kanungo (Citation2023) observed that the cult of Modi, which was visible in the 2019 election campaign, was built and furthered online by technological means and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (the RSS), India’s largest volunteer-led Hindu nationalist organisation, of which the BJP is an affiliate. He also noted that a notable feature of the campaign messaging was the hyphenation of phrases which included Modi as one part of the phrase.

Secondly, we provide an interpretation of what these hashtags imply to target audiences, predominantly the urban English speaking aspirational middle class on the one side and global influencers and political leaders on the other side (Pal, Citation2019). By showing the presence of such exaggerated frames over a long period of time we suggest that digital communication platforms are understood as spaces where political propaganda can be fed with the expectation of moulding political perceptions of a specific target audience. Some research shows that Twitter trend lists, in fact, alter the personal agenda of the users (M. M. Zhang & Ng, Citation2023). On this basis, we argue that projecting strategic messages using hashtags is a key element of the digital electoral strategies of Indian political parties.

Literature review

The role of personality in Indian politics post-2014

Modi’s persona plays a crucial role in driving people towards the BJP. His approval ratings are very high: with a figure of 77 per cent reported in a batch of data on global leaders collected in December 2023 (Morning Consult, Citation2023). A survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) also found Modi to have attracted 27 out of every 100 votes that BJP received in 2014 and 33 in 2019 (What data tells us about Indian Politics, Citation2023). CSDS data also suggests that in the 2019 elections, close to two-thirds of the voters (62 per cent) finalised their voting decisions during or after the campaign period of the elections (Sardesai, Citation2021).

Scholarly work has also interpreted this phenomenon with various terms like ‘Modi factor’, ‘Modi wave’, ‘Brand Modi’, ‘Modi Myth’, and ‘Modi Effect’, making it into mainstream discourse (Kaur, Citation2015; Kaul, Citation2017; Shastri, Citation2019). Many have interpreted this phenomenon in terms of populism. For instance, foreign policy under the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has seen more centralising and personalising tendencies (Destradi & Plagemann, Citation2019). Martelli and Jaffrelot (Citation2023), focusing on verbal cues, show how Modi communicates mimetic identification with his persona. Non-verbal personalised elements that attract attention, like Modi’s clothing that represent him as a ‘saviour’, have also been assessed (Vittorini, Citation2022). The modulation of his speech is used to improve communication with the rural audience he addresses in public rallies (Kumar et al., Citation2021). These features around persona creation present themselves as part of a grand approach to ‘celebritise’ Indian politics, within which Modi’s celebrity figure – of a saintly strongman, is strategically created using media, technology, and popular culture (Rai, Citation2019).

This sanitised persona and symbolism (Sen, Citation2016) that represents Modi in conventional media and grassroots campaign events also finds its way onto Twitter. Kaur finds that Modi was more central to the BJP’s social media discourse than its ideology (Kaur, Citation2015). He managed to present himself as someone with a credible personality from humble origins in a range of photographs in which he interacts with ordinary voters, other leaders and celebrities (Jain & Ganesh, Citation2020). In his Twitter discourse, he presented himself as a global statesman to his international audience, contrary to his populist leanings (Martelli & Jumle, Citation2023). Pal (Citation2017) argued similarly by showing how Modi used political irony to make his populist ethic appealing and presented himself as a technocratic leader for development (Pal, Citation2019) A well-thought-out Twitter strategy – that evolved from broken phrases to well-crafted tweets and an interaction protocol built over following and interacting with other users – over the years has allowed him to ‘transcend’ his problematic past and connect better and directly with ‘his’ people (Pal, Citation2015; Pal et al., Citation2016). His communication during demonetisation was a telling example: he sidelined mainstream media and used his Twitter account and public rallies to speak to ‘his’ electorate (Rodrigues & Niemann, Citation2019). He also continuously used the platform to campaign for his policies, like the Clean India Mission (Rodrigues & Niemann, Citation2017).

In contrast, Rahul Gandhi and the Indian National Congress (INC) – prominent opposition leader and party respectively – has received different treatment. The BJP portrayed Rahul Gandhi as an incompetent person – a pappu (imbecile) – who owed his political career to his dynastic privilege (which is emphasised in another insult which labels him shehzada (prince)). Julka (Citation2023, p. 133) argues that these terms implied more than their literal meaning and, in fact, drew upon ‘notions of caste/class, gender, religion, and historical privilege in Indian society’, enabling the ruling party to further its popularity and delegitimise the opposition. This delegitimising strategy extended onto Twitter. In the context of the assembly polls in the north Indian states in 2023, Modi tweeted, ‘May they be happy with their arrogance, lies, pessimism and ignorance. But.. [four alert emojis] Beware of their divisive agenda. An old habit of 70 years can’t go away so easily [four alert emojis]. Also, such is the wisdom of the people that they have to be prepared for many more meltdowns ahead [five smiling emojis]’ (Narendra Modi [@narendramodi], Citation2023).

The significance of hashtags for research on social media

The analytical focus of this paper is on hashtags since they allow us to capture a top-level longitudinal view of a certain political phenomenon on Twitter. The emphasis is particularly on hashtags that are explicitly framed to express affiliation to a side of the debate. While this approach helps us study the projections posited by the political parties more closely, the hashtags that discuss politically potent topics but do not explicitly express a stance are beyond the scope of our analysis. At the same time, we wish to submit that though the magnitude may be different, this does not change the direction of our argument. Hashtags as ‘symbolic’ terms have gained special prominence on social media and are the subject of developing scholarly interest in Twitter and beyond (Wang et al., Citation2011; Sykora et al., Citation2020; Zhang, Citation2019). Methodologically they are often used for the discovery of relevant tweets in diverse contexts that are then analysed.Footnote2

However, hashtags are not only a means to collect certain types of content but can be ends in themselves too. Small (Citation2011, p. 873), using Canadian politics as the theme, suggests that a hashtag is ‘a keyword assigned to information that describes a tweet and aids in searching’ and is central to organising information on Twitter. Importantly, they inform users about a political topic and are used ‘as a dissemination feed’. They also serve a broader purpose: they act as cognitive tools that help make certain contextual assumptions more accessible. Hashtags, by incorporating these assumptions inside the concise structure of a tweet, allow readers to deduce the intended significance of the message, so directing them towards a certain understanding. This function is essential in a medium known for being concise and immediate, where effectively conveying meaning within a limited character count is of utmost importance (Scott, Citation2015). Furthermore, the inclusion of political hashtags in online conversations serves as a clear demonstration of the substantial influence these identifiers have on the emotional atmosphere of conversations. Studies suggest that political hashtags can intensify the display of rage, hatred, and terror in comments, therefore influencing the emotional atmosphere of the subsequent interactions. This phenomenon is remarkable, as it indicates that hashtags can serve as triggers for increased emotional involvement, potentially influencing the tone of conversations towards more negative feelings (Rho & Mazmanian, Citation2020). Moreover, employing hashtags strategically can effectively address the difficulties arising from context collapse in online communication, which occurs when several audiences come together. Hashtags assist in managing the diverse interpretations that emerge in a dynamic communication environment by clearly defining the intended scope and relevancy of a message. Effective management is crucial in directing the conversation in a way that corresponds with the speaker’s desired message, even in the presence of varying viewpoints from the audience (Bruns & Burgess, Citation2011). We build on this argument to posit that hashtags on Twitter in India also serve similar functions. Analysing the explicit subjects of the most popular daily political hashtags, the study aims to ascertain, using the case of the 2019 election year, if political Twitter content was organised and disseminated around political personalities, and if so, in what context.

Data and methods

Data collection and analysis for this paper proceeded in five parts. First, the authors gathered relevant Twitter hashtags (#) for India from Twitter’s trend list. The study collated the daily top five hashtags between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019 based on the longest trending time of all hashtags that appeared each day. These amounted to 1815 hashtags.Footnote3 The classification of hashtags as trending or not is based on Twitter’s own algorithm and the authors do not have any influence over it. Fifty-five hashtags written in non-English scripts were excluded, which is a limitation of this study. The final dataset constitutes 1760 hashtags (97 per cent) of all the trending hashtags. The excluded data does not affect the findings in the way of its direction but may marginally under or overestimate the magnitude.

Second, these hashtags were qualitatively coded into seven categories based on Marchetti and Ceccobelli's (Citation2016) classification: ‘Entertainment’, ‘Pointless babble’, ‘News story’, ‘Sports’, ‘Domestic politics’ [India], ‘International politics’, ‘Technology’, ‘Geolocation’, ‘Religion’, ‘Recurring events’.Footnote4 We refer to these as ‘themes’ in the text because this categorisation effectively captures the diverse nature of digital communication, offering insights into both everyday social interactions and major societal trends, thereby providing an analytical framework to purposively analyse the data. We note later in the paper that we do not agree with the substantive significance of all of these categories, such as pointless babble, and regard them differently compared to Marchetti and Ceccobelli (Citation2016). Each hashtag was only classified into one category based on its explicitly expressed meaning. If a hashtag qualified into multiple categories, its contextual meaning was used to place it between the two (or more). For instance, this overlap often occurred in the case of ‘Domestic politics’ and ‘Religion’ since religion is and has often been the basis of many political movements in India. A contextual reading, therefore, allowed for a hashtag to be placed in either of the two, depending on which category a hashtag appeared relatively closer to.

Third, 586 hashtags were classified as ‘Domestic politics’. These were re-classified into further sub-categories, namely: ‘BJP’, ‘Advantaging BJP’, ‘Disadvantaging BJP’, ‘Opposition’, ‘Advantaging opposition’, ‘Disadvantaging opposition’, ‘Neutral’, ‘Social justice and empowerment’, ‘Crimes’, ‘Religious politics’, ‘Elections’.Footnote5 We refer to these as ‘subthemes’ in the text. The authors tailored these categories to the Indian domestic political landscape. For instance, while creating subthemes in support and against primary political contenders is a common practice, we also created categories like ‘Religious politics’ to account for references to religious, caste and cultural sentiments, ‘Social justice and empowerment’ to account for the prominence of caste and affirmative action, and ‘Crimes’ to account for issues like corruption or muscular political rivalry. The BJP here refers to the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling party in India, whereas the ‘Opposition’ refers to the broader understanding of opposition in a democratic setup, such as opposition parties, non-pliant media, activists, journalists, and so on. The principles of classification here remained the same as above, including resolving overlaps and single sub-category classification.

Fourth, tweets (and associated information like username, engagement metrics, time stamp, IDs, and URL) associated with ‘Domestic politics’ hashtags were collected using the Twitter Application Programming Interface for academic research. Tweets for a particular hashtag were tracked from ±12 hours of its trending time. This data was re-arranged to ascertain the total number of tweets each user made for each hashtag tracked under ‘Domestic politics’.

Fifth, the sub-themes relevant to party politics ‘BJP’, ‘Advantaging BJP’, ‘Disadvantaging BJP’, ‘Opposition’, ‘Advantaging opposition’, and ‘Disadvantaging opposition’ were grouped into secondary sub-themes as ‘Narendra Modi’, ‘Rahul Gandhi’, ‘Gandhi Family’, ‘Congress leadership’, ‘BJP leadership’, ‘Hindutva leadership’, ‘Regional personalities’, ‘Other personalities’ and ‘non-personalities’.Footnote6 These categories were curated to explore the share of attention paid to political figures. The two co-authors independently coded all variables for each hashtag. On average, the co-authors recorded a 95 percent coding agreement. Disagreements were mutually resolved. Following other reported findings, this study assumes that the top shortlisted political hashtags are in some way or the other a product of discourse mediation strategies. We assume that hashtags are deliberately used to curate political projections. This, however, may not hold true in all instances, and therein lies the study’s limitation.

Empirical analysis

Twitter in India

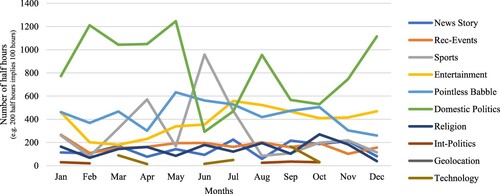

Twitter in India saw different trends emerge over the year. While some themes like Domestic politics and Entertainment occupied a spot on the trending chart throughout the year, other themes like International politics and Technology only occupied a spot sometimes. Domestic politics emerged as the most trending theme, with a 33 per cent share of the total hashtags count and a 34 per cent share of total trending time. Next on the list was pointless babble, with 19 per cent of hashtag share and 18 per cent share of trending time.Footnote7 These trends are presented in above. The horizontal axis indicates the months, and the vertical axis shows the number of half-hours. Different colours indicate the different themes and how long they occupied the trending chart across different months of 2019. Entertainment, Pointless Babble, and Sports emerged as consistent non-political themes on the trending list.

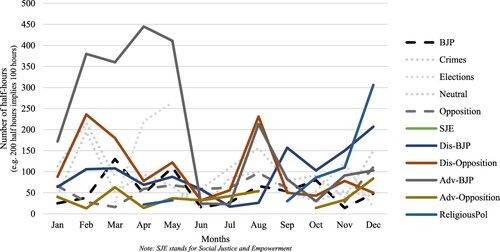

shows the sub-categories (or subthemes) that trended within Domestic politics. The horizontal axis represents the months, and the vertical axis represents the number of half hours. Different colours for the lines represent the different subthemes.

One significant trend is evident here. We observe that subthemes advantaging BJP are disproportionately higher than any other subtheme. This is particularly the case for the months leading up to the national elections in April-May 2019. The subtheme that ranks second during the months leading up to the election are those that disadvantage the opposition. Subthemes that contradict the narrative, in other words those that advantage the opposition or disadvantage the BJP, are substantially low, both in the share of number of hashtags (15.6 per cent of the domestic politics hashtags) and share of trending time (only 15.7 per cent of the domestic politics hashtags). This concurs with the findings of McGregor et al. (Citation2017), who show that the volume of Twitter discourse was a function of competitiveness and money spent. The BJP has distinct advantages here, as revealed in an Election Commission of India audit report, the party spent about 30 per cent (approx. INR four billion) of its expenditures on advertisements, of which 18 per cent was given over toelectronic media advertisements in 2020 (Arvind Gunasekar [@arvindgunasekar], Citation2023; Times of India, Citation2021). Notably, the BJP spent a total sum of 270 billion Rupees in the 2019 elections according to a report by Centre for Media Studies, India. Additionally, the BJP’s IT Cell directly and vicariously manages thousands of groups to disseminate information and influence the public sphere which amplifies BJP’s outreach (Schakel et al., Citation2019, p. 344).

Trends around personalities

This paper examines the prevalence and depiction of personality figures in the context of growing literature on Indian politics and national populism. This literature emphasises the re-emergence of personality politics since 2014 in which parties are losing influence to their leaders. Different concepts such as ‘celebratisation’ or ‘centralisation’ have also been used to draw attention to Modi’s central role in creating an electoral pull towards the BJP (or what is referred to as ‘Brand Modi’ in popular commentary). It is also argued similarly that the Indian National Congress suffers from its inability to project a strong personality as party leader. The distribution of political hashtags across personalities and non-personality sub-themes is an apt way to assess the centrality of political figures in political discourse.

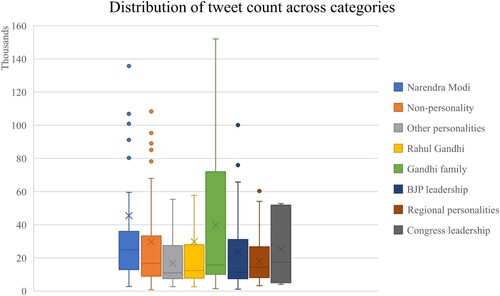

below provides a percentage distribution of hashtags across the eight categories above. The table shows that, firstly, the digital discourse on party politics centres around personalities. Overall, only 33.6 per cent of analysed hashtags were related to non-personality themes; the rest were all about individuals. Secondly, ‘Modi’ enjoys discursive popularity both in subthemes that disadvantage the BJP (35.7 per cent) or advantage the BJP (61.5 per cent). This implies hashtags in support of the current dispensation rally around those that portray Modi as the central subject. In parallel, this remains true even in discourses against the dispensation where ‘Modi’ shortly falls behind the ‘non-personality’ subcategory.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of personality figures.

How are personalities projected?

In discourses that advantage the BJP, Modi is often referred to in an electoral context calling for his re-election. In the descending order of tweets mentioning each hashtag, six out of the top ten referred to his re-election.Footnote8 Personalisation of politics and leader-anchored political parties are not new phenomena in India despite its parliamentary framework. Communication technology and social media by design reinforces such a paradigm. Twitter for instance, is not a passive reflector of public opinion but it is a space that can be used to distort public perceptions. The narrative on leading personalities are shaped by discursive frames. In this context, we elaborate here on the ‘chowkidar campaign’ as a revealing case study. A few hashtags from the study’s list feature this campaign (including#ChowkidarPhirSe and #iTrustChowkidar). The term ‘chowkidar’ (gatekeeper or watchman), which the prime minister adopted, was defined very broadly. Taken literally, referring to the prime minister as a gatekeeper seems misplaced. The humble occupation of gatekeeping is inconsistent with aspirational narratives of Indian society that Modi has championed. It is a low-skill job with minimal pay (Times of India, Citation2021). In taking on the title, Modi has destabilised conventional meanings, it is left for everyone to define the term for themselves. Everyone was invited to take on the metaphorical identity, to become a gatekeeper themselves, and they defined what it meant seeing it reflected in the leader. This frame of thought opens a discussion of how silhouettes of ‘aspirational ideals’, ‘embodiment’, ‘credibility’, and ‘promises of prosperity’ are crafted and projected in online space. These are also reflected in other hashtags associating Modi with different characteristics.

The BJP social media strategy, as highlighted in the works of Pal (Citation2019) and Ravish Kumar (Citation2019), is not merely about reaching audiences but also about shaping and sometimes manipulating public perception. Pal (Citation2019) notes that Modi’s use of Twitter and other social media platforms should be viewed as an artifact of a specific moment in history. The emphasis on technology-driven notions of development presents an aspirational frame that resonates with the media and a broad-based middle class. While his study concerns the tweets pertaining to Modi’s alignment with technocratic governing, which in turn is seen as part of his political rebranding and a means for the middle-class to find secular justifications for supporting him, we elaborate on the chowkidar (gatekeeper / guardian) campaign in the same context.

This campaign was launched against the backdrop of the allegations of corruption surrounding the government procurement of the Dassault Rafale fighter jet. The allegations were based on a few investigative media stories and amplified by opposition parties in the lead up to the 2019 elections. The opposition mocked the prime minister, who had earlier called himself the nation’s chowkidar, using the slogan ‘chowkidar chor hai’ (the gatekeeper is a thief). Placed in this context, the old chowkidar campaign was re-designed and re-launched to project Modi as the chief-guardian of national interests in the run up to national elections in 2019. In March 2019, Modi tweeted ‘Your Chowkidar is standing firm & serving the nation … ’ (Narendra Modi [@narendramodi], Citation2019). It was mobilised especially on social media to forge a collective identity around the leader pivoting on the theme of anti-corruption and societal vigilance. The chowkidar theme did not develop spontaneously among Twitter users, instead an early phase of the ‘#MainBhiChowkidar’ campaign saw about 1900 BJP leaders, including Modi himself, adding ‘chowkidar’ as prefix or suffix to their Twitter handles. Symbolically they adopted the role of defenders against corruption, societal evils, and ‘dirt’ at their individual levels. The campaign quickly gained momentum, turning into a popular movement where supporters displayed their allegiance and support, echoing this identifier in their social media handles and tweeting with these hashtags. Of many nudges, one was to take a pledge ‘I am proud to join #MainBhiChowkidar movement. As a citizen who loves India, I shall do my best to defeat corruption, dirt, poverty & terrorism and help create a New India which is strong, secure & prosperous’ (Business Standard, Citation2019).

This campaign’s effect in many ways resonates with the symbolism of distributing masks depicting Modi’s face to supporters who were asked to wear them while attending campaign rallies. Ghassem-Fachandi (Citation2019) interpreted it to be a symbolic delegation and projection of support to the leader, empowering the leader to speak and act on behalf of the populace. The idea of chowkidar – a common identifier, like the mask – was similarly to empower the individual and commend them for doing their ‘best’ to ‘defeat corruption, dirt, poverty & terrorism’ and vice-versa to extend their consent to the leader to act on their behalf to meet the same objective. On Facebook, this was replicated seamlessly, with users adding a ‘frame’ with the chowkidar slogan to their profile pictures like wearing a digital mask. The chowkidar campaign’s success can be attributed to the party’s sophisticated use of social media tools to amplify its message of Modi embodying the aspirations of a new India. It projected an image of Modi as someone who personally cared about each users’ contribution to the campaign. An automatic reply software was developed to reply to users on Twitter with a personalised message from Modi – a digital commendation – thanking them for their support (Dasgupta & Ravi Nair, Citation2022). This way on Twitter, the campaign managed to reach users even beyond their usual list of followers (CitationPanda and Pal n.d.). This projection fed directly into the middle class desire for a progressive, technologically advanced, and corruption-free India, importantly, elevating ordinary individuals into positions of power, as digital activists, to participate in a national drive beside the strong prime minister himself (#ModiMeinHaiDum (ModiHasTheBravado), #56InchRocks) each of them with the capability to defeat those who held back national progress. Similarly, hashtags like #MiddleClassWithModi have also made it to the top charts.

This idea recurs among hashtags where the prime minister is symbolically projected in a large-than-life manner. Take #DeskKeDilMeiModi (ModiIsInTheNation’sHeart) or #DeshKiPasandModi (Nation’sFavouriteModi) or #DeshKiShaanModi (Nation’sPrideModi) that sought to present him as the one who resides in the nation’s heart. It is representative of his admiration and acceptance within the populace that hold him dearly, without whom the nation is incomplete. Similar projections have emerged in the past too, such as in in early 2000s when Modi was celebrated as the Hindu Hriday Samrat (king of Hindu hearts).

In the discourse that disadvantages the BJP, Modi, in specific contexts, is referred to with overtones of being an outsider, especially during his visits or campaigns in south Indian states (#GoBackModi, #GoBackSadistModi). These tweets frame Modi as an outsider in the progressive milieu of south India. Campbell-Smith and Bradshaw (Citation2019) found traces of crude automation around this hashtag in 2019, indicating it may not fully reflect public opinion (although the same applies to those hashtags that ‘welcomed’ his visit). In other words, the campaigns trended owing to the concerted activity of a few dominant tweeters on both sides, albeit the size of the critical mass was higher with the #GoBackModi hashtag in comparison to the #TNWelcomesModi, which was heavily manipulated by bot activity.Footnote9

Extending the centrality of personalities, ‘Rahul Gandhi’ occupies a one-fifth share and one-fourth share in subthemes that disadvantage the opposition and advantage the opposition, respectively. The ‘Gandhi family’ personalities further occupy 16.7 per cent of hashtags in discourse favouring the opposition. The share of Rahul Gandhi, the Gandhi family, and regional opposition representatives surpasses non-personality themes in the discourse in favour of the opposition. In discourse that advantaged the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi is referred to six times with different contexts (#RahulForBehtarBharat (RahulForBetterIndia), #VanakkamRahulGandhi (HelloRahulGandhi), #IStandWithRahulGandhi, #RahulTharangam (RahulWave), #IAmRahulGandhi, and #ThankYouRahulGandhi). The share in such a theme is divided between Rahul Gandhi and other representatives, like the Gandhi family and Regional representatives.

In the discourse that disadvantages the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi, in specific contexts, is similarly placed in an ‘outsider’ light (#GoBackRahul, #GoBackPappu). Ridicule is commonly used as a strategy in line with the approach of delegitimising the opposition (#PappuDiwas (PappuDay), #RahulGandhiPagalHai (RahulGandhiIsMad), #RahulKaBaapChorHai (Rahul’sFatherIsAThief), #FattuPappu (CowardPappu), #RahulKaJijaChorHai (Rahul’sBrotherInLawIsAThief), #RahulStopTheTantrum).

These observations remain the same in subthemes where the hashtags do not convey an advantage/disadvantage connotation. In the case of the ‘BJP’, the focus remains on Modi, the BJP leadership and BJP’s regional personalities and in the case of the ‘opposition’, on Rahul Gandhi, the Gandhi family, the INC leadership, and regional personalities of the broader opposition. Overall representation of non-personality themes drops in both cases. Regional personalities include leaders relevant to the politics of New Delhi, West Bengal, south India, Maharashtra, Punjab and the Hindi heartland.

The popularity of personalities compared to non-personality themes is also confirmed by the number of tweets each gathered, as shown in below.Footnote10 The median of tweets gathered by Modi across categories surpasses that of non-personality topics. Similarly, the median for the Gandhi family and Congress leadership is comparable to non-personality topics. In other words, the Twitter discourse made the ‘presidentialisation’ of Indian politics common-sensical.

Discussion

What explains the trending cycle?

The trending patterns are likely a result of the thematic relevance of topics. We observe that the least popular themes trended inconsistently because their relevance to the Indian Twitter users may be tied to events unfolding over time rather than there being a pre-existing interest in them. For instance, Technology themes likely trended as a reaction to the launch of new electronic gadgets or software a few times a year. Similarly, the inconsistent trending of International politics themes, reflects unique yet influential events like Brexit, UK elections or bilateral meetings between India and other nations’ representatives.

Entertainment and Sports trended both due to a high frequency of events (such as the release of new films or songs or sports tournaments) and there also being a persistent interest within the Indian population towards the two themes. Pointless babble emerged as the only strong theme that trended due to a prior interest among Indian Twitter users. The theme persisted, not as a reaction to an external unfolding event, but because it allowed the populace a space for self-expression. For instance, weekly recurring trends such as #MondayMotivation allowed for the creation of digital spaces of empathy and compassion for those struggling to gather motivation to return to work after a weekend.

The consistent dominance of Domestic politics on Twitter speaks to the platform’s relevance to political messaging in India. Indian elections were held in seven phases between April and May 2019 (Sridharan, Citation2020). This explains the strong trending pattern of Domestic politics until May 2019, mainly seaking to the upcoming elections and other electorally relevant issues. The trend declined after the results were declared towards to the end of May 2019 and then gradually picked up in the later months.

What does mediating discourse in discursive frames imply?

A mediated discourse around discursive frames feeds into constructing the digital aura of the political figure. Of the 125 Modi-centric hashtags, the study interpreted 53 of them to be discursively framed. Like chowkidar, the use of ‘56inch’ (#56InchRocks) makes the pointFootnote11: it refers to Modi’s chest size – figurately, not literally. It suggests the frame of strength, muscularity, and bravado. To what ends are these features invoked is for the user to interpret for themselves. Thus the leader instead represents a multiplicity of individual interpretations. Many such day-to-day phrases such as ‘New India’, ‘Vikas’ (development), have been spun away from their common understanding into open ended constructs, invoked to mean different things in different contexts.Footnote12 For instance, against the backdrop of nationalist ideology, does ‘New India’ refer to a state that is for inclusive development or otherwise? This feature of mediations takes a discussion beyond the normative realm of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ (when a figure is associated with their political position), ‘success’ or ‘failure’ (a figure’s association with a policy decision), or ‘appropriate’ or ‘inappropriate’ (in relation to a political statement). It instead revolves around subjective interpretations and emotive aspects that do not necessarily fall in the categories of either/or. While the discourse continues to be represented by a sanitised keyword (or hashtag), its literal or common meaning loses any semblance of coherence or definitiveness.

Conclusion, and future research trajectories

Studies suggest that Twitter, by design, is personality-driven and incentivises discussions that revolve around personality traits rather than substantive policy deliberations (Ott, Citation2017; Uysal & Schroeder, Citation2019). These features tend to hold in India’s political Twitter world, where politicians have a more significant following than their party handles (Pal & Panda, Citation2019). BJP activists were more likely to run Modi-centric campaigns themselves; while the INC activists were less likely to take up leader-centric campaigns (Rajadesingan et al., Citation2020). Some scholarship points to how delegitimising the other bloc is reflected on Twitter due to systemic features of the platform (Ott, Citation2017). Gonawela et al. (Citation2020), showed that leaders of both the ruling party and the opposition, used Twitter to attack each other. They noted, ‘Across the board, negative language was retweeted significantly more by followers of all three [two from BJP, one from Congress] politicians, especially as we look at the popularity of insults’ (Gonawela et al., Citation2020, p. 2885).

We emphasise two findings from this analysis. First, we observe that personalities, especially Modi, emerge as central to the digital discourse at the level of country-wide trending hashtags as against non-personality centric themes. This feeds into the current state of affairs of the re-emergence of personalisation in India politics and reflects the trend towards a presidential-style political system, emphasising the leader’s role in politics relegating their party and institutional affiliations to the periphery. Second, we show that the themes which discuss personalities sustain throughout the year and occupy a notable share of trending time. Many different granular studies around a thematic set of political hashtags show the use of automation or coordination to mediate digital discourses, placing social media platforms like Twitter at the centre of political entities’ digital engagement strategies. This strategic approach is not limited only to logistics but also has a semantic aspect, shaping (though not defining) meaning-making among the electorate, as was the case in the #MainBhiChowkidar campaign. In other words, it is plausible to argue that many hashtags on the list, which either endorse or oppose a specific political stance, may have been intentionally designed to influence political discussions by highlighting or downplaying particular aspects of relevant political narratives.

We present two ideas for the future studies to further explore. Firstly, that emphasising personalities (say Modi or Rahul), their discursive traits (say ‘chowkidar’ or ‘pappu’ respectively) and driving a strategically crafted open-ended fantasy-like political meaning-making discourse around them is a relatively underexplored form of political distortion within Indian digital politics that deserves special attention. These high-profile discursive interventions go beyond the commonly researched techniques of political distortion, such as political disinformation. Research on the latter topic investigates the presence and effect of deliberate misinterpretation of facts on political opinion. However, fantasy-constructions or personifications do not fit existing categories since they fall outside the bracket of right or wrong, accurate or inaccurate. We therefore identity this phenomenon to be a distinct facet of Indian digital politics that frames a discourse into a bottom-less discussion wherein such traits can be (re)inventions which in turn add to the imagined constructions of the leader among the electorate. Secondly, given that these discursive constructions are constantly projected over a significant period, digital platforms are viewed and used as active channels to feed propaganda that moulds public perceptions. While our research discussed social media in an election year, research during non-election years would enrich the literature.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vedant Jumle for his research assistance. We would also like to sincerely thank the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback, which considerably enriched the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data is available for inspection at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ATGGJR

.Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Moore et al. (Citation2017) for a discussion of the ‘value’ and ‘performative’ dimensions of persona.

2 For examples of research on hashtags see Lai et al. (Citation2015) that used #mariagepourtous to collect tweets around political reform, and Jumle and Vignesh Karthik (Citation2021) which used #YemenCantWait to collect tweets on the humanitarian disaster in Yemen.

3 Ideally, the dataset should consist of 1825 hashtags. However, the hashtags for 2 January and 3 February were lost during the data collection process. We consider this to be a minor (0.5%) data collection error.

4 See Appendix Table 1 for a description of the categories.

5 See Appendix Table 2 for a description of the subcategories.

6 See Appendix Table 3 for a description of the sub-themes.

7 A complete list of hashtags, distributions and categorisations is available upon request.

8 These are/include: #ModiSarkar2 (ModiGovt2), #ChowkidarPhirSe (GatekeeperAgain), #ModiHiAayega (ModiWillOnlyCome), #KashiBoleNaMoNaMo (KashiSaysNaMoNaMo), #IndiaWantsModiAgain, #ModiAaRahaHai (ModiIsComing)).

10 ‘Hindutva Leadership’ is dropped owing to the relatively low amount of data.

11 More examples: #ModiNiti, #ModiLaoDeshBanao, #ModiJahanVikasWahan, #DeshKeDilMeiModi, #CoolestPM.

12 For further analysis of Modi’s discourse on development see Muraleedharan (Citation2023).

References

- Ahmed, S., Cho, J., & Jaidka, K. (2017). Leveling the playing field: The use of Twitter by politicians during the 2014 Indian general election campaign. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1377–1386.

- Ahmed, S., Jaidka, K., & Cho, J. (2016). The 2014 Indian elections on Twitter A comparison of campaign strategies of political parties. Telematics and Informatics, 33(4), 1071–1087.

- Arvind Gunasekar [@arvindgunasekar]. (2023). Bank balance of two major national parties as of March 2023: BJP – 3,596 Crore Congress – 162 crore https://T.Co/p4aPjkbFrF. Twitter. https://twitter.com/arvindgunasekar/status/1695697726946820480.

- Bhatia, K. V., & Arora, P. (2024). Discursive toolkits of anti-Muslim disinformation on Twitter. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 29(1), 253–272.

- Borah, A., & Singh, S. R. (2022). Investigating political polarization in India through the lens of Twitter. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 12(1), 97.

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011). The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. In Proceedings of the 6th European consortium for political research (ECPR) general conference 2011 (pp. 1–9). The European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR).

- Business Standard. (2019). Modi Launches ‘Main Bhi Chowkidar’ Campaign. https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/modi-launches-main-bhi-chowkidar-campaign-119031600194_1.html.

- Campbell-Smith, U., & Bradshaw, S. (2019). Global cyber troops country profile: India. Oxford Internet Institute.

- Cervi, L., García, F., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). Populism, Twitter, and COVID-19: Narrative, fantasies, and desires. Social Sciences, 10(8), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080294

- Dasgupta, P. G. T., & Ravi Nair, A. (2022). How top meta executive Shivnath Thukral Has links with a firm that works for Modi and BJP. Newslaundry. https://www.newslaundry.com/2022/05/02/how-top-meta-executive-shivnath-thukral-has-links-with-a-firm-that-works-for-modi-and-bjp.

- Dash, S., Mishra, D., Shekhawat, G., & Pal, J. (2022). Divided we rule: Influencer polarization on Twitter during political crises in India. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 16 (pp. 135–46).

- Destradi, S., & Plagemann, J. (2019). Populism and international relations: (Un)predictability, personalisation, and the reinforcement of existing trends in world politics. Review of International Studies, 45(5), 711–730.

- Fitzgerald, J. (2013). What does ‘political’ mean to you? Political Behavior, 35(3), 453–479. doi:10.1007/s11109-012-9212-2

- Gerlitz, C., & Helmond, A. (2013). The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society, 15, 1348–1365.

- Ghassem-Fachandi, P. (2019). Reflections in the crowd delegation, verisimilitude, and the Modi mask. In A. P. Chatterji, T. B. Hansen, & C. Jaffrelot (Eds.), Majoritarian state: How Hindu nationalism is changing India (pp. 83–98). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190078171.003.0005

- Gonawela, A., Ahmad, D., Kumar, R., Chandrasekaran, R., Thawani, U. (2020). The Anointed Son, The Hired Gun, and the Chai Wala: Enemies and Insults in Politicians’ Tweets in the Run-Up to the 2019 Indian General Elections. Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2878–87).

- Gonawela, A., Pal, J., Thawani, U., van der Vlugt, E., Out, W., Chandra, P. (2018). Speaking their mind: Populist style and antagonistic messaging in the tweets of Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, Nigel Farage, and Geert Wilders. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 27, 293–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-018-9316-2

- Hindman, M., & Barash, V. (2018). Disinformation, “fake news”, and influence campaigns on Twitter. Knight Foundation.

- Jaidka, K., & Ahmed, S. (2015). The 2014 Indian general election on Twitter: An analysis of changing political traditions. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, ICTD ‘15, New York, NY, USA (pp. 1–5). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2737856.2737889.

- Jain, N., Malviya, P., Singh, P., & Mukherjee, S. (2021). Twitter mediated sociopolitical communication during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in India. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.784907.

- Jain, V., & Ganesh, B. E. (2020). Understanding the magic of credibility for political leaders: A case of India and Narendra Modi. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1–2), 15–33.

- Jakesch, M., Garimella, K., Eckles, D., & Naaman, M. (2021). Trend alert: A cross-platform organization manipulated Twitter trends in the Indian general election. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2), 379.

- Julka, A. (2023). Rahul Gandhi as ‘Prince’ and Pappu: The Hindu right’s politics of ridicule. In O. Feldman (Ed.), Political debasement: Incivility, contempt, and humiliation in parliamentary and public discourse, the language of politics (pp. 133–147). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0467-9_7

- Jumle, V., & Vignesh Karthik, K. R. (2021). Why must we talk about Yemen’s humanitarian crisis? NewsClick. https://www.newsclick.in/why-we-talk-yemen-humanitarian-crisis.

- Jungherr, A. (2015). Twitter as political communication space: Publics, prominent users, and politicians. In A. Jungherr (Ed.), Analyzing political communication with digital trace data: The role of Twitter messages in social science research, contributions to political science (pp. 69–106). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20319-5_4

- Kanungo, P. (2023). The rise of the NaMo cult and what lies ahead for ‘New India.’ https://thewire.in/politics/narendra-modi-cult-bjp-election-victory.

- Karthik, V., Jumle, V., & Karunanithi, J. (2020). BJP’s Twitter experiments and tamil resilience. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(44). https://www.epw.in/journal/2020/44/commentary/bjps-twitter-experiments-and-tamil-resilience.html.

- Kaul, N. (2017). Rise of the political right in India: Hindutva-development mix, Modi myth, and dualities. Journal of Labor and Society, 20(4), 523–548.

- Kaur, R. (2015). Good times, brought to you by brand Modi. Television & New Media, 16(4), 323–330.

- Kumar, R., (2019). Bad News. Reforming India: The Nation Today. New Delhi: Penguin Random House India.

- Kumar, A., Shrotriya, S., & Chandra, M. (2021). Role of temporal amplitude modulation in Indian political scenario: Narendra Modi vs. Rahul Gandhi. In 2021 5th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Networks (ISCON) (pp. 1–5). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9702318

- Lai, M., Bosco, C., Patti, V., & Virone, D. (2015). Debate on political reforms in Twitter: A hashtag-driven analysis of political polarization. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) (pp. 1–9). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7344884.

- Leidig, E. (2016). “What Does Modi's Personal Popularity Tell Us about India's Political Landscape?” South Asia@LSE. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2016/02/08/what-does-modis-personal-popularity-tell-us-about-indias-political-landscape/ (December 7, 2023).

- Linvill, D. L., & Warren, P. L. (2020). Troll factories: Manufacturing specialized disinformation on Twitter. Political Communication, 37(4), 447–467.

- Marchetti, R., & Ceccobelli, D. (2016). Twitter and television in a hybrid media system. Journalism Practice, 10(5), 626–644.

- Martelli, J.-T., & Jaffrelot, C. (2023). Do populist leaders mimic the language of ordinary citizens? Evidence from India. Political Psychology, 44(5), 1141–1160.

- Martelli, J.-T., & Jumle, V. (2023). Populism à La Carte: The paradoxical political communication of Narendra Modi on Twitter. Global Policy, 14(5), 899–911.

- McGregor, S. C., Mourão, R. R., & Molyneux, L. (2017). Twitter as a tool for and object of political and electoral activity: Considering electoral context and variance among actors. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(2), 154–167.

- Moore, C., Barbour, K., & Lee, K. (2017). Five dimensions of online persona. Persona Studies, 3(1), 1–12. doi:10.21153/ps2017vol3no1art658

- Morning Consult. (2023). Global leader approval rating tracker. Morning Consult Pro. https://pro.morningconsult.com/trackers/global-leader-approval.

- Muraleedharan, S. (2023). Narendra Modi’s ‘Gujarat model’: Re-moulding development in the service of religious nationalism. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 61(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2023.2203997

- Narendra Modi [@narendramodi]. (2019). Your Chowkidar is standing firm & serving the nation. But, I am not alone. Everyone who is fighting corruption, Dirt, social evils is a Chowkidar. Everyone working hard for the progress of India is a Chowkidar. Today, Every Indian is saying-#MainBhiChowkidar. Twitter. https://twitter.com/narendramodi/status/1106759555315314689.

- Narendra Modi [@narendramodi]. (2023). May they be happy with their arrogance, lies, pessimism and ignorance. But.. ⚠ ⚠ ⚠ ⚠ beware of their divisive agenda. An old habit of 70 years can’t go away so easily. ⚠ ⚠ ⚠ ⚠ also, such is the wisdom of the people that they have to be prepared for many more meltdowns … . Twitter. https://twitter.com/narendramodi/status/1731902708951773546.

- Neyazi, T. (2017). Social media and political polarization in India. Seminar, 699, 31–35.

- Neyazi, T. (2020). Digital propaganda, political bots and polarized politics in India. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(1), 39–57.

- Ott, B. L. (2017). The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(1), 59–68.

- Pal, J. (2015). Banalities turned viral: Narendra Modi and the political tweet. Television & New Media, 16(4), 378–387.

- Pal, J. (2017). Mediatized populisms| Innuendo as Outreach: @narendramodi and the use of political irony on Twitter. International Journal of Communication, 11(0), 22.

- Pal, J. (2019). The making of a technocrat: Social media and Narendra Modi. In A. Punathambekar & S Mohan (Eds.), Global digital cultures: Perspectives from South Asia, global digital cultures: Perspectives from South Asia (pp. 163–183). University of Michigan Press.

- Pal, J., Chandra, P., & Vinod Vydiswaran, V. G. (2016). Twitter and the rebranding of Narendra Modi. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(8), 52–60.

- Pal, J., & Panda, A. (2019). Twitter in the 2019 Indian general elections: Trends of use across states and parties. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(51), 1–17.

- Panda, A., & Pal, J. Chor or Chowkidar: Who Won the ‘Chowkidar’ Battle on Twitter during the 2019 Indian Elections. Propaganda Analysis Project. https://propaganda.qcri.org/bias-misinformation-workshop-socinfo19/paper13_final_Chor_or_Chowkidar__who_won_the__chowkidar__battle_on_Twitter_during_the_2019_Indian_elections_final.pdf

- Rai, S. (2019). ‘May the force be with you’: Narendra Modi and the celebritization of Indian politics. Communication, Culture and Critique, 12(3), 323–339.

- Rajadesingan, A., Panda, A., & Pal, J. (2020). Leader or party? Personalization in Twitter political campaigns during the 2019 Indian elections. In International Conference on Social Media and Society, SMSociety’20, New York, NY, USA (pp. 174–83). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400827.

- Rho, E. H. R., & Mazmanian, M. (2020). Political hashtags & the lost art of democratic discourse. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13).

- Rodrigues, U., & Niemann, M. (2017). Social media as a platform for incessant political communication: A case study of Modi’s ‘Clean India’ Campaign. International Journal of Communication, 11(0), 23.

- Rodrigues, U., & Niemann, M. (2019). Political communication Modi style: A case study of the demonetisation campaign on Twitter. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 15, 361–379.

- Sardesai, S. (2021). Explained: Over 2 decades, growing proportion of voters who decide choice late. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-over-2-decades-growing-proportion-of-voters-who-decide-choice-late-7613855/.

- Schakel, A. H., Sharma, C. K., & Swenden, W. (2019). India after the 2014 general elections: BJP dominance and the crisis of the third party system. Regional & Federal Studies, 29(3), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2019.1614921

- Scott, K. (2015). The pragmatics of hashtags: Inference and conversational style on Twitter. Journal of Pragmatics, 81, 8–20.

- Sen, R. (2016). Narendra Modi’s makeover and the politics of symbolism. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 9(2), 98–111.

- Shastri, S. (2019). The Modi factor in the 2019 Lok Sabha election: How critical was it to the BJP victory? Studies in Indian Politics, 7(2), 206–218.

- Shome, D., Neyazi, T. A., & Ting Ng, S. W. (2023). Personalization of politics through visuals: Interplay of identity, ideology, and gender in the 2021 West Bengal assembly election campaign. Media, Culture & Society, 777–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437231214189

- Small, T. A. (2011). “What the hashtag?” information. Communication & Society, 14(6), 872–895.

- Sridharan, E. (2020). India in 2019. Asian Survey, 60(1), 165–176.

- Sykora, M., Elayan, S., & Jackson, T. W. (2020). A qualitative analysis of sarcasm, irony and related #hashtags on Twitter. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 2053951720972735.

- Times of India. (2021). How BJP earned its crores & what did it spend them on. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/how-bjp-earned-its-crores-what-did-it-spend-them-on/articleshow/85221555.cms.

- Tulasi, A., Gupta, K., Gurjar, O., Buggana, S., Mehan, P., Buduru, A., & Kumaraguru, P. (2019). Catching up with trends: The changing landscape of political discussions on Twitter in 2014 and 2019. http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.07144.

- Uysal, N., & Schroeder, J. (2019). Turkey’s Twitter public diplomacy: Towards a ‘new’ cult of personality. Public Relations Review, 45(5), 101837.

- Vittorini, S. (2022). Modi à La Mode: Narendra Modi’s fashion and the performance of populist leadership. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 60(3), 276–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2022.2066383

- Wang, X., Wei, F., Liu, X., Zhou, M., & Zhang, M. (2011). Topic sentiment analysis in Twitter: A graph-based hashtag sentiment classification approach. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Glasgow Scotland, UK (pp. 1031–40). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2063576.2063726.

- What Data Tells Us about Indian Politics. (2023). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LeESphnaa3M.

- Zhang, M. M., & Ng, Y. M. M. (2023). #TrendingNow: How Twitter trends impact social and personal agendas? International Journal of Communication, 17, 20.

- Zhang, Y. (2019). Language in our time: An empirical analysis of hashtags. In The World Wide Web Conference, WWW ‘19, New York, NY, USA (pp. 2378–89). Association for Computing Machinery.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Categories based upon Marchetti and Ceccobelli (2016).

Appendix 2. Subcategories within subcategories that concern political parties.

Appendix 3. Subcategories within subcategories that concern political parties.