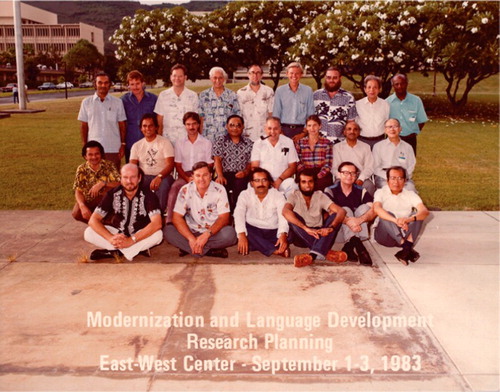

At the end of this introduction, there is a photograph. At first glance, it looks fairly unremarkable, but, as photos do with the passing of time, it has become an historical artefact. It is a group photo of participants in a research-planning meeting convened in 1983 by Björn Jernudd as a part of the project he directed at the East-West Centre, Honolulu, entitled “Modernisation and Language Development”. Included in the photo are some very eminent linguists as well as several younger academics who would become some of the most influential figures in the contemporary field of language policy and planning (LPP). In the group are, Björn Jernudd and Jiří V. Neustupný, two founding figures of language management theory (LMT), and others who went on to become leaders in linguistic and socio/applied linguistic research in South Asia and the Asia-Pacific, among them E. Annamalai, Terry Crowley, Anton Moeliono, and D. P. Pattanayak. Also in the photo are two colleagues who were to establish a collaboration that would play a major role in advancing the study of LPP, Richard (Dick) Baldauf and Robert (Bob) Kaplan, the co-founders of this journal (see ).

The 1983 research meeting provides a starting point both for the beginning and for the end of this special issue in honour of Dick's contributions to LPP as a scholarly field. It is a year that has special significance both in personal and in academic terms for Dick's closest collaborator, Bob Kaplan, as he explains in his memoire at the end of this issue. The picture also provides a fitting opening point, as it brings together some of the key scholars who contributed to the study of LPP in its early years. As can be seen, at that time Dick was still a relatively young academic and it is not difficult to imagine the influence the members of this group would have had on him. He went on to become himself an influence on a whole emerging generation of LPP and applied linguistics scholars, a population that was not restricted to the Anglophone academic world but also extended across non-English-speaking areas.

The term “LPP” encompasses various research strands that focus on the regulation and management of the forms, functions and uses of language (Nekvapil & Sherman, Citation2015). In the 1960s and 1970s, as the end of the colonial system gained momentum, theoreticians and practitioners of LPP focused primarily on planning that attempted to address the language problems of newly independent developing nations (see, e.g. Fishman, Ferguson, & Das Gupta, Citation1968; Fox, Citation1975; Rubin & Jernudd, Citation1971). Later scholars focused on the theorisation of LPP (e.g. Fishman, Citation1974; Haarmann, Citation1990; Haugen, Citation1983). The 1983 meeting and the photo that records it, mark the fact that the theoretical foundations of LPP as a broad field of enquiry including language management (LM) were being laid in the 1980s (see Jernudd & Nekvapil, Citation2012; Jernudd & Neustupný, Citation1987), although the origins of LMT can be traced back to the 1970s (see Neustupný, Citation1974, Citation1978) and the modernising mission of LPP back to the aftermath of the Second World War (see Baldauf, Citation2012; Wright, Citation2004). For more recent students of LPP, its origins and links with LM are often overlooked, a point well made in Nekvapil's contribution to this issue (see also Nekvapil, Citation2011, Citation2012).

Capturing the full extent of a person's life work is a daunting task, as I have found in my efforts to sum up Dick's body of work. I became one of his protégés, having sought him out as a PhD supervisor. Dick's supervision load was already well over quota and it is a measure of his generosity that he was willing to take me on. Like many others, I also sought his professional advice, which was always honest and direct but also good humoured, and it has influenced me greatly in the way that I work. Often, in the course of managing the ups and downs of academic life, an image of Dick has come to my mind, leading me to pause and rethink a problem or retrieve my own sense of humour.

The broad range of the papers contributed by the people contributing to this special issue serves as an indication of Dick's breadth as a scholar and the scope of his work and interests. A list of his publications since 2005 can be found in Taylor-Leech, Nguyen, Hamid, & Chua, Citation2014. Bob Kaplan also discusses his own productive collaboration with Dick in detail in the end piece of this issue. This introduction will therefore not attempt to move chronologically through his publications but rather will provide a selective overview of his contributions to the fields of LPP and Applied Linguistics.

Dick was a graduate in the humanities and his early academic training was in educational psychology. He moved into the field of language studies when he arrived in Australia in the mid-1970s, where he initially worked in TESOL education. Coming from an education background, the links between language teaching/learning and applied linguistics were always going to be of interest to him. In various publications, he attempted to outline the core as well as the sub-activities of the Applied Linguistics field and to trace its history in Australia (see Baldauf & Kaplan, Citation2010; Gitsaki & Baldauf, Citation2012). He gained first-hand involvement in Australian LPP as a result of his appointment as research manager for Language Australia, the National Languages and Literacy Institute of Australia, a position which opened up for him a vista of language and literacy policy development by Federal and State governments (for overviews, see Lo Bianco, Citation1990, Citation2000; Moore, Citation1996).

Dick's career spanned the years when LPP was coming into its own as an academic discipline. In several publications, he surveyed the evolution of the field, identifying and defining the strands within it (see, e.g. Baldauf, Citation2005, Citation2012). Dick's and Bob's grounding in educational and applied linguistics made it inevitable that they would start from practice. Their co-authored publication “Language Planning: From Practice to Theory”, (Kaplan & Baldauf, Citation1997) illustrates this approach. The book sets out to demystify the field, establishing key concepts and definitions for LPP, describing their central elements of practice and providing illustrative examples through a series of case studies. While the debate on the relationship between LPP and their definitions – and indeed what actually constitutes policy – continues (see Cassels Johnson, Citation2013), the volume by Kaplan and Baldauf stands as a foundational contribution to the field and an essential reference for both novice and experienced scholars.

Dick is also widely recognised as one of the founding editors of the “Language Planning and Policy” journal and book series, working with several co-editors but most consistently with Bob Kaplan. The studies in this collection describe and analyse LPP development in some 27 states in Asia and the Asia-Pacific, Africa, Europe and Latin America and are written by authors who have all in some way been directly engaged in the language planning contexts. The volumes cover various polities in each region, in each explaining the linguistic situation in relation to its historical, political and educational context, examining the drivers of LPP activity and discussing the roles and influences of the media, religion and non-indigenous languages.

By the late 1990s, the limitations of the so-called classical language planning approach had become clear. Dick's later publications would acknowledge that, with hindsight, the association of language planning with modernisation, democratisation and westernised notions of progress was simplistic and overoptimistic (see, e.g. Baldauf, Citation2012). Influenced by critical and postcolonial theory, the analysis of LPP began to take on a more politicised tone (see Ricento, Citation2000 for a synopsis of historical perspectives, and Ricento, Citation2006 for an overview of LPP research methods). Greater emphasis began to be placed on LPP in its socio-economic and ecological contexts (see, e.g. Baldauf, Citation2005; Hornberger & Cassels Johnson, Citation2007; Hornberger & Hult, Citation2008; Mühlhäusler, Citation1996, Citation2000). Dick had already been taking an interest in the ecology of languages since the 1980s, publishing with Björn Jernudd on the ecological impacts of the dominance of English in scientific academic publishing (Baldauf & Jernudd, Citation1983, Citation1986, Citation1987). Dick also tipped his hat to the work of Francophone scholars of aménagement linguistique (Baldauf, Citation2006, p. 152), who themselves took an ecological view (see, e.g. Calvet, Citation1999; McConnell, Citation2005).

Recognising that LPP endeavours were not restricted only to governmental actions in newly independent nations, scholars began increasingly to engage with issues of power and politics, diverse identities, the language rights of minorities, the place and status of heritage languages, the impacts of LPP on local language ecologies, and in particular with the effects of English as a language of wider communication on diverse language systems around the world, and with the consequences of a shift to dominant and former colonial languages (for an overview of literature on LPP and the ecology of language, see Hult, Citation2010). The ideological dimensions of LPP became a focus of attention as scholars recognised that language policy is one mechanism by which elite groups establish and sustain their hegemony and by which governments maintain social control (see, e.g. Luke, McHoul, & Mey, Citation1990; Pennycook, Citation1998; Tollefson, Citation1991, Citation2006).

Drawing on the work of earlier academics (e.g. Cooper, Citation1989; Haugen, Citation1983) and in parallel with other contemporaries (notably Hornberger, Citation1994, Citation2006), Dick worked on sketching out a framework for classifying the goals of LPP (see 1997, 2005, 2006). It is barely necessary here to reiterate Dick's framework of goals, which suggests that LPP can be explicit or overt, implicit or covert, and may be one of four types:

Status planning – about society.

Corpus planning – about language.

Acquisition or language-in-education planning – about learning/teaching.

Prestige planning – about image.

Each of these four types can be realised through an emphasis on form – that is, on basic language and policy decisions and their implementation, or through an emphasis on cultivation – that is, on the functional extension of language development and use (Baldauf, Citation2006, pp. 149–152). Kaplan and Baldauf (Citation1997, p. 52) suggested that language planners set out to achieve such goals at three broad levels, the macro, the meso and the micro. But they were careful to point out that, however useful frameworks may be for mapping the discipline, LPP goals are not independent of each other. They may occur as a range of different types, some of which may be in conflict and may result in unintended outcomes. Dick characterised these sorts of outcomes as “unplanned” LPP (Baldauf, Citation1994).

The shift in the focus of LPP studies towards a more critical view, Dick argued, required a rethinking of the notion of agency – a term that enquires into “who has the power to influence change in micro LPP situations” (Baldauf, Citation2005, p. 147). Meso and micro-level LPP studies focus on the language planning efforts of local agents and the contexts in which they operate. Numerous studies have used the macro-meso-micro levels model to examine LPP processes in various contexts, as the papers in this and other journals concerned with LPP attest (for a few examples, see Baldauf, Citation2006; Liddicoat & Baldauf, Citation2008).

Liddicoat and Taylor-Leech (Citation2014, p. 234), making reference to micro-LPP processes in education, identify four broad ways in which local agents work: (i) by locally implementing macro-level policy; (ii) by contesting, appropriating or resisting macro-level policy; (iii) by making efforts to address local needs in the absence of macro-level policy; and (iv) by taking initiatives that open up new opportunities for developing multilingualism. These four strategy types can easily be applied to other spheres of micro-LPP activity. However, again, the macro and the micro levels should not be regarded as mutually exclusive. Dick recognised the problems inherent in the macro–micro distinction (Baldauf, Citation2005, Citation2006) and was very aware that the interactions between the personal, the local, the regional and the national are subtle and fluid, often overlapping and politically complex (see, also Hult, Citation2010; Hult & Pietikäinen, Citation2014). The ways in which both individual (micro-level) and community (meso-level) language behaviour relates to societal (macro-level) LPP remain a topic of ongoing interest in LPP research (Hult, Citation2010, p. 7), and is taken up by Skerrett in this issue.

Currently, the pendulum seems to be swinging back towards the macro level as scholarly attention is being paid to the effects of globalisation, mass migration, and neo-liberalism on LPP at various levels. Of interest for many researchers is the emergence of powerful global actors and supranational agencies, and the ways in which they have the capacity to exert influence on language policy development in various parts of the world. This is the thematic focus of a second forthcoming publication in celebration of Dick's work edited by another of his collaborators, Catherine Chua Siew Kheng, entitled “Issues in Language Planning and Policy: From Global to Local” (to be published in June, 2016 by De Gruyter Open). Contemporary sociolinguists and applied linguists as well as LPP researchers have explored the specific ways in which globalised ideological discourses shape local language debates, LPP processes, and feed into social and pedagogic practices. In addition, recent developments in critical sociolinguistics have brought the notions of time, space and scale into play in the analysis of LPP and its locally circulating discourses (see, e.g. Hult, Citation2010, Citation2015; King, Citation2013).

In 2007, in cooperation with Shouhui Zhou, Dick made a foray into Chinese corpus planning with the publication of “Planning Chinese Characters – Reaction, Evolution or Revolution?” (Zhou & Baldauf, Citation2007). The volume evaluates the efforts of three twentieth-century movements to modernise the Chinese writing system in the People's Republic of China (PRC), especially noting the challenges that digital, electronic technology has posed for Chinese script development. Echoes going back to 1983 reverberate as, in addition to the research meeting mentioned earlier in this introduction, Dick had been invited by Björn Jernudd to take part in another meeting immediately following, which brought together scholars from mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore, the USA and elsewhere to discuss the modernisation of the Chinese language (see Kaplan, this issue; also http://languagemanagement.ff.cuni.cz/en/system/files/documents/EWC%20.pdf).

One of Dick's last major contributions was as guest editor of the section on LPP in Volume II of Hinkel's (Citation2011) edited “Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning”, first published in 2005 with a section on LPP which Dick also guest edited (see Hinkel, Citation2005). The section contains six chapters which survey the state of the field. Apart from this work, questions of agency and language power in LPP remained an area of interest for Dick in the remaining years of his life. Dick recognised that many instances of medium-of-instruction policy have been driven by forces of globalisation and internationalisation, and he saw that this was now a major issue for language-in-education planners. In what was to be one of his final papers, he wrote: “The current trends of globalisation and internationalisation also have their localisation counterparts and the tensions between these raise issues of concern for all of us in the field” (Baldauf, Citation2012, p. 241).

The title of this special issue echoes that of Kaplan and Baldauf's seminal 1997 text “Language Planning: From Practice to Theory”. Like that volume, the present collection of papers reflects the fact that the field has tended not to be theory-driven but “rather responsive to real-world interdisciplinary solutions of immediate practical problems” (Kaplan & Baldauf, Citation1997, p. xi). For many academics, the appeal of LPP as a field of study lies in its grounding in real-world language problems in contemporary situations, offering opportunities for on-the-ground research that links language policy-making, practice and performance to theory but also deals with symbolic and substantive policy discourses, and connects to questions of power, ideology and identity.

In 2012, Dick predicted several directions in which future LPP studies might go. These directions included practices at the different levels of language planning; covert language planning, or the failure to make LPP explicit, that is, failing even to address certain language issues at all (in other words, neglecting policy entirely), as well as the identification of the key actors in LPP and the analysis of their roles; and the growing international trend towards the compulsory teaching of early foreign and second languages, especially the teaching of English and its use as a medium of instruction in contexts where it is a non-native or a second language (Baldauf, Citation2012).

The articles in this collection take up these issues and move from practice to theory as they engage with some of the important language problems of contemporary times across the world, and analyse how different actors and stakeholders engage with them. The extensive references to Baldauf's work made by the contributing authors are not only made out of respect to Dick, but they also demonstrate his importance to the entire field of LPP. These contributions deal respectively with:

the relationship between LPP and LM, as well as Dick's interest in that relationship (a macro-level view);

the role of language academies in corpus planning in China (macro level);

LPP and the market for English in Bangladesh (macro level);

the effects of globalised discourses on institutional LPP in a Swedish university setting (meso/micro level);

actor engagement in English for Academic Purposes programmes in Australian universities (micro level);

local teachers assuming agency as they respond to national language-in-education policy reform in the remote highlands of Vietnam (micro level); and

macro-level policy and micro-level language use in the former Soviet state of Estonia (macro-meso-micro).

The following overview of these papers reflects the range of Dick's interests and shows the route map his work has provided for current and future scholars, many of whom are already taking his work in new and exciting directions.

In an article that sketches the historical roots of LPP theory, Jiří Nekvapil, a leading proponent of LMT, builds on Dick's (2012) differentiation between four main approaches in the theorisation of LPP (the classical approach, the LM approach, the domain approach and the critical approach) and usefully highlights the main features of LMT as a branch of LPP. The paper is particularly interesting because it not only shows the convergence between the two approaches, but also how they have diverged. It also demonstrates how Dick was influenced by LMT and his longstanding interest in LM.

Shouhui Zhou and Guowen Shang take forward Zhou's work with Dick on the modernisation of Chinese characters as they examine the Chinese language modernisation movement in the twentieth century (see also Zhao, Citation2010; Zhao & Baldauf, Citation2011). The paper focuses on the interactions between LPP agencies in the light of the historical legacies and current sociopolitical conditions in the PRC (see also Zhou, Citation2011). The authors suggest that the challenges presented by digital and web-based technology necessitate much wider acceptance of character reform than ever before and call for planning approaches based on consensus (i.e. from the bottom up) rather than on dictate (i.e. from the top down). Another contribution of the paper is that it shows how language academies can take diverse forms. Such academies are not necessarily only comprised of purist elites that seek to preserve language from change, but they may also function to democratise the language and broaden access to literacy.

M. Obaidul Hamid's paper takes a discourse ideological perspective and shows how the failure to address broader social concerns can undermine macro-level LPP initiatives. Drawing on Bourdieu's concepts of the linguistic market and linguistic capital, the paper highlights the problem of differential proficiency outcomes for actors affiliated with different education markets in Bangladesh a situation that works against universal access to the linguistic and social capital afforded by English. Hamid argues that, while macro-level policy discourses have been driven by aspirations for equality in introducing English for all, it is actually market forces that determine who attains linguistic competence and whose competence is likely to be transformed into linguistic capital.

Francis Hult and Marie Källkvist consider the language policies of three Swedish universities as instances of LPP in local contexts. While the coexistence of Swedish and English is encouraged throughout higher education and in other areas of Swedish society, there is some tension between the uses of Swedish and English in academic domains, particularly when it comes to the medium of instruction and to research publishing – a challenge shared by other Scandinavian higher education institutions. The authors focus on the Nordic ideal of parallel language use, which seeks to strike a balance between the use of English and the desire to forestall the loss of Swedish domains. The authors consider how the concept of parallel language use is increasingly being employed by the universities as a language planning construct and they evaluate how successfully it is being applied to meet the needs of the universities’ constituents. They further consider the potential of the concept to influence LPP at a national level.

Also taking higher education as a context for study, Ben Fenton-Smith and Laura Gurney look at the roles of actors and agents in several academic language programmes in Australian universities. With the increasing internationalisation of the tertiary student body not only in Australia but around the world, academic LPP is taking on increasing importance. The authors’ interviews with academic programme planners indicate a consistent lack of coherent university-wide language policy-making, a situation that constrains effective programme development and delivery. They call for decision-making bodies to be representative of all stakeholders involved in context-sensitive programme design and implementation.

Hoa Nguyen and Thuy Bui explore the agentive role of teachers in implementing top-down policy in Vietnam. In the context of national reforms which aim to see all school leavers with a minimum level of English proficiency by the year 2020, they report on interviews with non-native English teachers about how they meet the challenges of teaching English to ethnic minority students in rural and remote areas. Nguyen and Bui apply Fullan's (Citation1993) theory on change agency, to understand how the teachers engage with policy in their everyday pedagogical practices. The study highlights the need for policy-makers to take into account the critical role played by teachers in implementing successful reform.

Delaney Skerrett's paper shows how individual (micro-level) language choices are negotiated within their socio-historical (macro-level) context. Skerrett's study examines how official language policy and the discourses around language use in Estonia translate into real-world local language practices. Such practices, he argues, allow a holistic understanding of how the macro, meso and micro-levels interact. This multilayered approach, he argues, provides a way of arriving at an informed understanding of why people use language in particular ways in multilingual contexts.

Last, but by no means least, Bob Kaplan closes this issue with an account of his personal and professional relationship with Dick. Theirs is a model of how the bonds of friendship go across international borders and how meaningful and committed academic collaboration not only provides fertile ground for the exchange of ideas but also produces high-quality research.

For me, the privilege of editing this special issue has been to show how all academic achievement is truly made on the shoulders of others. Those of us who are motivated to carry on Dick's work and academic legacy would do well to do so in this same spirit of amicable collaboration.

Figure 1. A photo from a collection of Björn Jernudd. Research-planning meeting convened in 1983 by Björn Jernudd as a part of the project he directed at the East West Centre, Honolulu on Modernisation and Language Development. Back row from left: Francis Mangubhai, Terry Crowley, Richard B. Baldauf, John DeFrancis, Paul Brennan, Björn Jernudd, John Lynch, Hoang Tue, E. Annamalai. Mid row from left: Patrick Hohepa (kneeling), Robert Underwood, David Cressy, Anton Moeliono, Robert B. Kaplan, Bobbie Nelson, D. P. Pattanayak, Zhou Youguang. Front row from left: Robert Gibson, Gregory Trifonovitch, Monsur Musa, Jayadeva Uyangoda, Jiří V. Neustupný, Bonifacio P. Sibayan. Not present: Donald M. Topping, John Kwock-Ping Tse and Jyotirindra Dasgupta.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Robert B. Kaplan, Jiří Nekvapil and Björn Jernudd for their helpful feedback on this paper and for the interesting snippets of information that helped me to write it. Any mistakes or inaccuracies remain my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Kerry Taylor-Leech is an Applied Linguist in the School of Languages and Linguistics at Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. Her research focuses mainly on language-in-education policy and planning in multilingual settings and the relationship between language, policy and identity, particularly in the context of migration and settlement.

References

- Baldauf J. R. B., & Jernudd, B. H. (1983) Language of publication as a variable in scientific communication. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 6(1), 97–108.

- Baldauf, R. B. (1994). ‘Unplanned’ language policy and planning. In W. Grabe (Ed.), Annual Review of Applied Linguistics: Language Policy and Planning 14 (pp. 82–89). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Baldauf, R. B. (2005). Language planning and policy research: An overview. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 957–970). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Baldauf, R. B. (2006) Rearticulating the case for micro language planning in a language ecology context. Current Issues in Language Planning, 7(2), 147–170. doi:10.2167/cilp092.0

- Baldauf, R. B. (2012). Introduction – Language planning: Where have we been? Where might we be going? Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 12(2), 233–248. doi:10.1590/S1984-63982012000200002

- Baldauf, R. B., & Jernudd, B. H. (1986). Aspects of language use in cross-cultural psychology. Australian Journal of Psychology, 32, 381–392. doi: 10.1080/00049538608259024

- Baldauf, R. B., & Jernudd, B. H. (1987). Academic communication in a foreign language: The example of Scandinavian psychology. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 98–117.

- Baldauf, R. B., & Kaplan, R. B. (2010). Australian Applied Linguistics in relation to international trends. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 2, 04.1–04.31. doi:10:2104/aral1004

- Calvet, L.-J. (1999). Pour une écologie des langues du monde [An Ecology of Languages of the World]. Paris: Plon.

- Cassels Johnson, D. (2013). Language policy. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan.

- Cooper, R. L. (1989) Language planning and social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fishman, J. A. (1974). Language planning and language planning research: The state of the Art. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Advances in language planning (pp. 15–33). The Hague: Mouton.

- Fishman, J. A., Ferguson, C. A., & Das Gupta, J. (Eds.). (1968). Language problems of developing nations. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Fox, M. J. (1975). Language and development: A retrospective survey of Ford Foundation language projects, 1952-1974. (2 vols.). New York, NY: The Ford Foundation.

- Fullan, M. (1993). Changing forces: Probing the depth of educational reform. London: Palmer Press.

- Gitsaki, C., & Baldauf, R. B. Jr. (Eds.). (2012). The future of Applied Linguistics – Local and global perspectives: An introduction. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

- Haarmann, H. (1990). Language planning in the light of a general theory of language: A methodological framework. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 86, 103–126. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1990.86.103

- Haugen, E. (1983). The implementation of corpus planning: Theory and practice. In J. Cobarrubias, & J. A. Fishman (Eds.), Progress in language planning: International perspectives (pp. 269–289). Berlin: Mouton.

- Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (2005). Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hinkel, E. (Ed.) (2011). Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, Vol. II. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hornberger, N. H. (1994). Literacy and language planning. Language and Education, 8 (1–2), 75–86. doi:10.1080/09500789409541380

- Hornberger, N. H. (2006). Frameworks and models in language policy and planning. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An introduction to language policy: Theory and method. (pp. 24–41). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Hornberger, N. H., & Cassels Johnson, D. (2007). Slicing the onion ethnographically: Layers and spaces in multilingual education policy and practice. TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 509–532. doi:10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00083.x

- Hornberger, N. H., & Hult, F. M. (2008). Ecological language education policy. In B. Spolsky, & F. M. Hult (Eds.), The handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 280–296). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Hult, F. (2010). Analysis of language policy discourses across the scales of space and time. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 202, 7–24. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2010.011

- Hult, F. M. (2015). Making policy connections across scales using nexus analysis. In F. M. Hult, & D. Cassels Johnson (Eds.), Research methods in language policy and planning: A practical guide (pp. 217–231). Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

- Hult, F. M., & Pietikäinen, S. (2014). Shaping discourses of multilingualism through a language ideological debate: The case of Swedish in Finland. Journal of Language and Politics, 13(1), 1–20. doi:10.1075/jlp.13.1.01hu

- Jernudd, B., & Neustupný, J. V. (1987). Language planning: For whom? In L. Laforge (Ed.), Proceedings of the international colloquium on language planning (pp. 69–84). Québec: Les Presses de L'Université Laval.

- Jernudd, B., & Nekvapil, J. (2012). History of the field: A sketch. In B. Spolsky (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of language policy (pp. 16–36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B. (1997). Language planning from practice to theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- King, K. (2013). Timescales, continuities and language-in-education policy in the Global South. In J. Arthur Shoba, & F. Chimbutane (Eds.), Bilingual education and language policy in the Global South (pp. 146–154). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Liddicoat, A. J., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (2008). Language planning in local contexts: Agents, contexts and interactions. In A. J. Liddicoat, & R. B. Baldauf (Eds.), Language planning and policy: Language planning in local contexts (pp. 3–17). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Liddicoat, A. J., & Taylor-Leech, K. (2014). Micro-language planning for multilingual education: Agency in local contexts. Current Issues in Language Planning, 15(3), 237–244. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2014.915454

- Lo Bianco, J. (1990). Making language policy: Australia's experience. In R. B. Baldauf Jr., & A. Luke (Eds.), Language planning and education in Australasia and the Pacific (pp. 47–79). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2000). Making languages an object of public policy. Agenda, 7(1), 47–46. TESOL Quarterly 46 (2), 230–257. doi:10.1002/tesq.19

- Luke, A., McHoul, A. W., & Mey, J. L. (1990). On the limits of language planning: Class, state and power. In R. B. Baldauf, Jr., & A. Luke (Eds.), Language planning and education in Australasia and the South Pacific (pp. 25–44). Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

- McConnell, G. D. (2005). Language shift and balance in a globalizing world: An ecological-analytical approach. Plenary address presented the 2nd Symposium on Language Policy: Language Policy in Mexico and Latin America, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, 10–12 August.

- Moore, H. (1996). Language policies as virtual realities: Two Australian examples. TESOL Quarterly, 30(1), 473–449. doi:10.2307/3587694

- Mühlhäusler, P. (1996). Linguistic ecology. Language change and linguistic imperialism in the Pacific region. London: Routledge.

- Mühlhäusler, P. (2000). Language planning and language ecology. Current Issues in Language Planning, 1(3), 306–367. doi: 10.1080/14664200008668011

- Nekvapil, J. (2011). The history and theory of language planning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. II, pp. 871–887). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nekvapil, J. (2012). From language planning to language management: J. V Neustupný’s heritage. Media komyunikeshon kenkyu / Media and Communication Studies, 63, 5–21.

- Nekvapil, J., & Sherman, T. (2015). An introduction: Language management theory in language policy and planning. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 232, 1–12. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2014-0039

- Neustupný, J. V. (1974). Basic types of treatment of language problems. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Advances in language planning (pp. 37–48). The Hague: Mouton.

- Neustupný, J. V. (1978). Outline of a theory of language problems. In J. V. Neustupný (Ed.), Post-structural approaches to language: Language theory in a Japanese context (pp. 243–257). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Pennycook, A. (1998) English and the discourses of colonialism. London: Routledge.

- Ricento, T. (2000). Historical and theoretical perspectives in language policy and planning. In T. Ricento (Ed.), Ideology, politics and language policies: Focus on English (pp. 9–24). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Ricento, T. (Ed.). (2006). An Introduction to language policy: Theory and method. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Rubin, J., & Jernudd, B. H. (Eds.). (1971). Can language be planned? Sociolinguistic theory and practice for developing nations (pp. xii–xxiv). Honolulu: East-West Center.

- Taylor-Leech, K., Nguyen, H., Hamid, M. O., & Chua, C. (2014) Tribute to Richard (Dick) Birge Baldauf Jr. (1943–2014): A distinguished scholar and an inspiring mentor. Current Issues in Language Planning, 15(3), 343–351. doi:10.1080/14664208.2014.940688

- Tollefson, J. W. (1991). Planning language, planning inequality. London: Longman.

- Tollefson, J. W. (2006). Critical theory in language policy. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An introduction to language policy: Theory and method (pp. 42–59). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Wright, S. (2004). Language policy and planning: From nationalism to globalisation. Basingstoke, Hamps: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zhao, S. H. (2010). Flows of technology: Mandarin in cyberspace. In V. Vaish (Ed.), Globalization of language and culture in Asia (pp. 141–162). New York, NY: Continuum Books.

- Zhao, S. H., & Baldauf, R. B. Jr (2011). Simplifying Chinese characters: Not a simple matter. In J. A. Fishman, & O. Garcia (Eds.), Language and ethnic-identity (Vol. II). (pp. 168–179). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zhou, S. H. (2011). Actors in language planning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. II, pp. 905–923). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Zhou, S. H. & Baldauf, R. B. (2007). Planning Chinese characters: Evolution, revolution and reaction. Dordrecht: Springer.