ABSTRACT

In this paper, we provide an overview of the policies that have existed in relation to Australian First Nations students’ languages, and English language and literacy learning before exploring how the politics of distraction manifests in this context. We then share our findings of an analysis of Australian language education policies for First Nations children and the media discourses which surround them. We argue that, in the context of First Nations languages and language learners, ‘language’ is conflated with either ‘literacy’ or ‘culture’ to distract from the sovereign language rights of First Nations peoples in Australia. We draw on the notion of ‘policy narrowing’ to explain this policy distraction and the ways in which it reproduces educational inequities for First Nations students in the Australian schooling system. To counter this, and the surrounding media discourses, governing educational bodies should re-centre language rights and language learner diversity in policymaking.

Introduction

Towards the end of the eighteenth century and before the British invasion of Australia, it has been estimated that there were many hundreds of traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderFootnote1 languages spoken across the nation (Dixon, Citation2019). In the last 200 hundred years, the devastating and continuing impacts of invasion have been widely felt and now only about 12 languages are spoken as a first language (NILR, Citation2020). During this time new Indigenous contact languages have emerged which include creoles such as Kriol spoken across the north of the continent, and dialects, such as Australian Aboriginal English, which is spoken by many First Nations’ peoplesFootnote2 (Dickson, Citation2019; Malcolm, Citation2018; Rodríguez Louro & Collard, Citation2021; Vaughan & Loakes, Citation2020).

With colonisation came linguistic discrimination and the imposition of both overt and more subversive mechanisms to subjugate Australian First Nations peoples, often done with the explicit intent to assimilate these peoples into western society (Ellinghaus, Citation2003). This included banning the use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages while imposing English to create and maintain colonial rule. Such inherent linguicism (Dovchin, Citation2020) in policy and practice, including within educational circles, has continued through to the present time with a consequential negative impact on this cohort. Language and literacy policy and practice in Australia are based on ‘English-only, monolingual-centric assumptions’ (Cross et al., Citation2022, p. 1). So inherent are these assumptions that Australia has no policy designating English as its official language (Hogarth, Citation2019). Additionally, ‘language’ has largely been subsumed by ‘literacy’ in educational and broader public discourse and the two have become ‘virtually synonymous’ (McIntosh et al., Citation2012, p. 461). English language literacy has become the central focus of policy and practice in Australian schools, thereby silencing the language backgrounds of many First Nations children whose linguistic repertoires remain invisible to their educators (Sellwood & Angelo, Citation2013; Steele & Wigglesworth, Citation2023).

With the sharp focus on English language literacy in Australian schooling, a national obsession with the level of Indigenous students’ literacy (henceforth ‘IndigenousFootnote3 literacy’) has consumed political and educational circles for much of the last 50 years and has intensified in the years since the implementation of national literacy and numeracy testing in 2008. Since 2008, there have been significant shifts to educational policies to focus on literacy in standardised Australian English (SAE) and substantial funding commitments to improving ‘Indigenous literacy’ with little to no consideration of the language backgrounds and cultural identities of First Nations children. In the Northern Territory, bilingual schools were disbanded and a first four hours in English policy was enforced in response to poor National Assessment Program – Literacy and NumeracyFootnote4 (NAPLAN) results for Aboriginal children. The Australian Government funded ($30 m) the implementation of Direct InstructionFootnote5 (DI), an American literacy programme developed in the 1960s, in schools with large Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in very remote parts of northern Australia; many of whom are culturally diverse and multilingual. State governments have also followed suit (e.g. in addition to federal funding, the Western Australia government has provided a considerable level of funding to the Kimberley School’s Project that follows a similar model).

Since its inception in 2008 Australia’s most significant funding programme for First Nations peoples – ‘Closing the Gap’ – has targeted the literacy skills of First Nations children, using NAPLAN as the measure of progress. Despite over a decade of funding, there has been little to no improvement in NAPLAN performance, and the target has recently been removed in favour of targeting early childhood educational outcomes. These examples represent simplistic problem-solution responses or ‘distractions’ (Farley et al., Citation2021) which are misguided in their intentions and act to further compound the ways in which First Nations children have been marginalised by the educational system.

These costly policy measures are not only acts of distraction; they actively perpetuate and entrench deficit discourses about Indigenous literacy as both politicians and the public alike take the view that investing millions of dollars has made little difference. The single-minded focus on the English language literacy skills of First Nations children in the Australian schooling system has failed to account for learners’ linguistic identities and the social, cultural, political contexts of their language practices in the context of the ongoing colonisation of Australia (Steele, Citation2020). We argue that this singular focus on literacy, at the expense of language, other diverse skills and knowledge, is a policy of distraction that acts as an instrument of colonial oppression for First Nations children in the schooling system – one that works to maintain colonial structures and perpetuate current power asymmetries in society (De Sousa Santos, Citation2021; Mignolo, Citation2021).

In recent times, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages are gaining traction in schools, after being banned in Australia and, in particular, from schooling for the most part of the last century. They are now taught as formal languages and included in other ways such as through naming practices, and in cultural events such as NAIDOCFootnote6 week. We argue such practices work in concert with the debate about ‘Indigenous literacy’ to distract from the underlying unequal mechanisms in the Australian education system and to ensure their continuation.

Politics of distraction

In this paper, we adopt Farley et al.’s (Citation2021) conception of policy distraction as a ‘persistent focus on a narrowly defined set of policies or a constrained set of potential solutions to policy problems’ (p. 168). Drawing on Giroux (Citation2013, Citation2017) and Spade (Citation2011), Farley et al. (Citation2021) argued that such policy distractions act to ‘obscure a deeper understanding of the policy context and the lived experiences of students, families, and communities’ and ‘divert attention from the root causes, complex structural forces, and historical and contextual circumstances’ (p. 168). Through the analysis of language education policies and public discourse, in our study, we focus on the way that ‘language’ is conflated with ‘literacy’ and ‘culture.’ This narrowing within policy effectively obscures the complexities of the situation which includes colonial dispossession and the ongoing structural violence and discrimination that First Nations students experience in the schooling system (Brown, Citation2018; Moodie et al., Citation2019; Vass, Citation2014; Weuffen et al., Citation2023).

To date, there has been little research that has explored how political distractions have been employed and for what purpose in the context of First Nations language learners in Australia. A void that the present study addresses. Hattie’s (Citation2015) What doesn’t work in education: The politics of distraction presents five common distractions in the field of education: appease the parents, fix the infrastructure, fix the students, fix the schools, and fix the teachers. However, this work focuses on mainstream education and fails to account for the positionality of First Nations students, and their languages within schooling’s colonial apparatus. In the current study, we focus on ‘policy narrowing’ (Farley et al., Citation2021) as an instrument of distraction, and the ways such policy narrowing renders the complexities of the situation invisible and instead represents simple problem-solution or ‘common-sense’ paradigms that perpetuate and normalise linguistic inequality. In particular, we focus on educational policy and media discourses surrounding First Nations languages to better understand how they are positioned in schools and society: what or who is included and excluded – and to what effect.

Language policy

To explore the narrowing of language education policy, we adopt a broad view of language policy (see Johnson, Citation2013) that includes examining policy as explicitly stated in English language education documentation, such as those related to teaching English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EAL/D) learners, as well as the mechanisms which shape English language education policy in practice, such as funding decisions or the implementation of NAPLAN testing. The latter are features of Piller and Cho’s (Citation2013) concept of ‘neoliberalism as language policy’ in which they argue that neoliberalism, as an economic ideology, ‘serves as a covert language policy’ (p. 23). Fundamental to neoliberalism as language policy is ‘the use of English as the language of global competitiveness’ (Piller & Cho, Citation2013, p. 24). This was the argument put forward in the establishment of Australia’s Language: The Australian Language and Literacy Policy (Dawkins, Citation1991), which heralded the current era of ‘English literacy’ as both the national focus and as the mechanism to address claims of a ‘national crisis’ (Lo Bianco, Citation2008; Lo Bianco, Citation2016, see also Clyne, Citation1997).

It is these ideological positionings, ones entrenched in policy without being explicitly stated, that act to maintain colonial structures and perpetuate inequalities. For First Nations languages and languages learners these inequalities in the Australian schooling system have been well articulated in relation to the implementation of NAPLAN (Angelo, Citation2011; Macqueen et al., Citation2018; Wigglesworth et al., Citation2011), and the structure of current funding models which often fail to accurately identify First Nations language learners (ACTA, Citation2022; Angelo, Citation2013; Dixon & Angelo, Citation2014; Lingard et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, it has been widely argued that such policies and practices reinforce the invisibility, and peripheral positioning of many First Nations language learners (see Angelo & Hudson, Citation2020; Poetsch, Citation2020; Sellwood & Angelo, Citation2013; Steele & Wigglesworth, Citation2023). Our study seeks to extend previous analyses by examining contemporary Australian educational language policy from the perspective of policy distraction.

The role of the media

The media has played a pivotal role in the narrowing of policy through both their reporting and their failure to report. From Edelman’s (Citation1988) six elements in the construction of political spectacle, two are key to the creation of distraction and the subsequent narrowing of policy. First is the manufacturing of a crisis (Anderson, Citation2007). This acts to crystallise the issue into one singular problem that a broad audience can easily understand, for example, ‘the Indigenous literacy crisis’ (see Fogarty et al., Citation2017). It also creates a sense of urgency and prompts public debate, as experts and the public alike seek to ‘solve’ the problem presented. Others have described how the notion of ‘common-sense’ is often evoked (e.g. Stack, Citation2007; Thomas, Citation2003, Citation2005). In the second element, which Edelman (Citation1988) describes as ‘the media as mediator of the political spectacle’ the media narrative is tightly controlled to ensure a narrow construction of the problem. He goes on to explain: ‘In every case a widening of the frame within which an event is viewed would change its meaning but would also create an account typically categorized as research rather than as news and often as dull rather than dramatic’ (p. 201). The implication being that the ‘complex structural forces, and historical and contextual circumstances’ (Farley et al., Citation2021, p. 168) of events reported in the media remain underexplored and without meaningful depth. Despite this lack of substance, the media’s position in contemporary society is so pervasive that the public discourses produced powerfully shape both educational policy and practice (Blackmore & Thorpe, Citation2003; Doolan & Blackmore, Citation2018; Lingard & Rawolle, Citation2004; Mockler, Citation2020; Rowe Citation2019; Waller, Citation2012).

The impact of media representations is strongly felt by Australia’s First Nations peoples and is illustrative of Farley et al.’s (Citation2021) notion that political distraction serves to perpetuate inequalities. Norman et al. (Citation2020) reported on a study by Thomas et al. (Citation2019), that examined the newsprint media coverage of Aboriginal political aspirations over 45 years and found the presence of three dominant narratives:

The study found inadequate representation of Aboriginal aspirations and standpoints in the public discourse about the events studied, that the media appear to address Aboriginal aspirations from positions where the expectation of failure resounds and that the media show an unforgiving resistance to Aboriginal aspirations. (Norman et al., Citation2020, p. 19)

There remains a dearth of studies which focus specifically on the media’s representation of First Nations languages and language learners within language education policy in the way our current study aims to do. However, studies such as that by Waller (Citation2012, p. 459) point to the negative influence of the news media, in this case suggesting it was ‘a significant factor’ in the Northern Territory (NT) education minister’s decision to replace their bilingual programme for Aboriginal languages with the ‘first four hours of English.’ A broader analysis of Australian language learners by Fillmore (Citation2023) revealed the presence of racialized language ideologies (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015) in the Australian media. A series of news headlines was presented to illustrate how language education was positioned as a valuable commodity for privileged white Australians, but as a problem for immigrants and First Nations Australians. The current study will extend this work with a focus on First Nations languages and language learners in language education policy and public discourse.

Research questions

To understand how the politics of distraction operate in language education policy and public discourse, using ‘policy narrowing’ as a theoretical concept, two research questions are addressed:

How does language education policy in Australia address language recognition and language rights for First Nations languages and language learners?

How are First Nations languages and language learners represented in the Australian media?

Method

Corpus-assisted approaches to critical discourse analysis were used to identify and then explore dominant themes (Baker, Citation2004, Citation2006; Baker et al., Citation2008). This approach involves using both quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis (Baker, Citation2004, Citation2006; Baker et al., Citation2008). Through quantitative corpus linguistics techniques such as keyword searches, word frequencies and word collocation, key language patterns can be identified for qualitative analysis using critical discourse analysis (Baker, Citation2004, Citation2006; Baker et al., Citation2008). Subsequent qualitative interpretation, using critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2010), can then identify dominant and silenced discourses in the data.

Critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2010) was used to qualitatively uncover the politics of distraction i.e. how representations of crises or policy problems act to maintain and reinforce asymmetrical power structures in society. Fairclough (Citation2010, p. 44) suggests that this often achieved through the technique of naturalisation, where one ideological representation is given ‘the status of common sense’ and consequently, ‘no longer visible as ideologies.’ Following Mignolo (Citation2011), Ahmed (Citation2021) suggests that critical discourse analysis is extended to account for the ‘coloniality of power [as] a central theme in all postcolonial nations’ (p. 140). Consequently, in our analysis, we use the approach described above to interrogate how the sovereign language rights of First Nations peoples in Australia have been positioned in language education policy and the related media discourses through the perspective of policy distraction. For this reason, we do not focus on the statistical significance of keywords, as others who use corpus driven approaches have done, but rather we use these techniques as a precursor – sifting through the data and identifying patterns relevant to our study, before conducting a critical discourse analysis.

RQ1 procedure

To examine how First Nations languages and language learners are represented in language education policy in Australia, a corpus of policy documentation was created for analysis from a thorough web search of publicly available information with a focus on government educational sectors. Non-government sectors were not included in the search because access to these documents is limited and may differ significantly according to school or area. Most policy documentation relates to First Nations EAL/D learners and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages curriculum. Policies focussing on ‘mainstream’ literacy and the study of other languages were not included. The policy documentation was categorised at three levels – international, national and state, with documentation for each state and territory in Australia included. Eighty-six policy documents were identified for analysis which were categorised into 73 items (see Appendix for the full list of policy documents).

RQ2 procedure

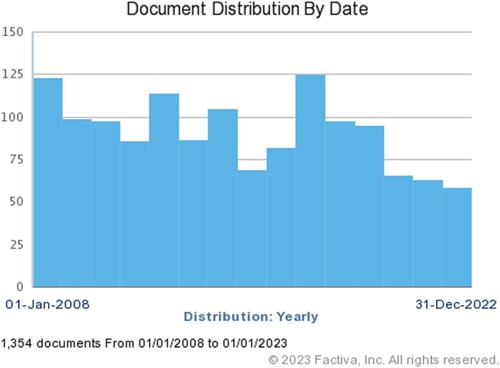

For the second research question, Factiva was used to create a corpus of news media items from 1st January 2008 to 1st January 2023. This date period was specifically selected to examine the last 15 years since the implementation of NAPLAN testing; the ‘literacy’ period. The following search terms were used: (Aboriginal OR First Nations OR Indigenous) AND (School OR Education) AND (Literacy OR Language) and results included those printed in Australia and appearing in English. The search yielded 1246 news articles (1354 including duplicates); the most common news sources were Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) news online (131 articles), The Australian (113 articles) and Northern Territory (NT) News (62 articles), with local newspapers the Centralian Advocate (34), the Courier Mail (31), the West Australian (30) and the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH) (28) producing a similar number of outputs. The search results were sorted by ‘most recent first’ to observe changes over time (see ).

Data analysis

For RQ1, an annotated bibliography was developed to provide a broad overview of the policies and to identify emerging critical insights. For RQ2, notes were used for the initial analysis. All data were added to NVIVO to enable quantitative and qualitative analyses based on these insights. Word frequency searches, word clouds and word trees were used to understand the relationships that exist within and between the range of policy documentation. Text searches were used to cross-check patterns which were identified and to analyse dominant and silenced discourses.

Findings

In this section, the findings from research questions 1 and 2 are presented.

RQ1

Our analysis of language education policy in Australia revealed that the language rights of First Nations peoples are rarely recognised with a preference for ‘softer’ language. Policy documents are highly complex and there appears to be a lack of clarity in the various policies that act to distract from language rights and understanding of learner diversity. When language rights are acknowledged, the focus is on traditional languages, whilst Indigenous contact languages remain peripheral.

Language recognition and language rights

Overall, the development of the Framework for Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Islander Languages in the Australian Curriculum in 2015 (ACARA, Citationn.d.; Appendix, item 12) and its equivalent state-based curriculum was a significant act of language recognition. However, within this, and other policy documentation, there is minimal recognition of First Nations peoples’ language rights – 11 policy documents from the 73 analysed. Language rights are recognised in the rationale of the Framework:

Aboriginal languages and Torres Strait Islander languages are fundamental to the identity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and this is recognised throughout the Framework. It is also the right of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to have access to education in and about their own languages, as enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (resolution 61/295, adopted 13 September 2007, www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf). (ACARA, Citationn.d.)

In the policy documentation, there appears to be a preference for the use of ‘softer’ language such as ‘recognition’, ‘culture’, ‘diversity’, and ‘respect’ rather than full acknowledgement of the sovereign status of First Nations peoples or their language rights. For instance, within the Framework for Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Islander Languages in the Australian Curriculum, there was only one content description related to learning about language rights (i.e. ACLFWU063 in the L1 pathway and ACLFWU191 in the LR pathway), with language rights being defined in a Glossary rather than discussed in the body of the text (ACARA, 2015, p. 9; Appendix, item 12). Language rights are not referred to in any other key national documentation or in any EAL/D documentation.

Outside of the Framework for Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Islander Languages in the Australian Curriculum (ACARA, Citationn.d.; Appendix, item 12) there were, however, several policy documents that did recognise First Nations languages and language rights. This included a description of the global activism efforts to promote mother tongue education, multilingualism, the rights of Indigenous peoples and the preservation of Indigenous languages. These were particularly evident in international policies (Appendix, items 1–4) and in Australia, the development of national action plans for the International Year of Indigenous Languages, and the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (Appendix, items 6–7). Another notable example is the newly developed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages policy of Queensland (Appendix, items 21 and 22) which forms part of that state government’s greater commitment to a Treaty (Appendix, item 20) the words ‘rights’ and ‘self-determination’ are referred to alongside various policy and legislation which uphold these rights, including references to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Despite these laudable inclusions, the word ‘sovereignty’ is not used.

Language rights are not a feature of EAL/D policies. In fact, in many jurisdictions references to legal legislation are not about language, but rather the rights of children. For example, in the Australian Curriculum, the Melbourne Declaration is mentioned alongside the Disability Discrimination Act (Appendix, item 13). The ACT’s EAL/D policy draws on the Human Rights Act 2004, the Discrimination Act 1991, the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (Appendix, item 48). Queensland does include the rights of Indigenous peoples in relation to language and education but does so by describing their obligations under Queensland’s Multicultural Recognition Act 2016 and Human Rights Act 2019. Explicit recognition of a child’s right to speak their own language is not stated and instead the focus is on a child’s language being valued or simply recognised. The Australian Council of TESOL Association (ACTA) EAL/D Elaborations of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Appendix, item 11) specifically recommends human rights be embedded in teaching and curriculum approaches.

Overall, within policy instead of words like ‘language rights,’ ‘sovereignty’ or ‘self-determination,’ there is a strong preference for ‘softer’ language such as ‘recognition,’ ‘culture,’ ‘diversity,’ and ‘respect’ that fail to assert the sovereign status of First Nations peoples and their language rights. This is an act of policy distraction that denies the language rights of First Nations peoples.

Policy complexity

Our analysis revealed a high degree of complexity presented in the policy. Additionally, extensive knowledge is seemingly required to make sense of the relationships between the various documents and how they fit together. An illustrative example is the diagram provided by the Department of Education, Victoria which has been created to support teachers to navigate the EAL resources provided (Appendix, item 45). This one-page document contains 41 hyperlinks to other resources to support teachers with their EAL teaching; an exceptionally large number of documents to navigate and make sense of. This is further complicated by the terminology it contains. It is based on three identified policies; however, these are not called policies, and, in fact, the first listed policy is referred to as ‘guidance.’ This mire of terminology appears to be a common practice across the different jurisdictions with various terms being used interchangeably including: policies, procedures, frameworks, guidance, guidelines, advice, agreements, partnerships, statements, strategies, action plans, and models. It is unclear whether the intention is to capture the situational complexity and the nuances of educational policy in these differing descriptions, or whether it is the enforceability (or lack thereof) that leads to a high degree of variation both in policy and terminology. Regardless of intent, the consequences are significant. This level of policy complexity acts as a distractor because it makes it easier to revert to simplistic and narrow notions of English ‘literacy’ rather than becoming lost disentangling policies that are often not even referred to as ‘policies,’ as will be described further in the discussion.

The peripheral positioning of Indigenous contact languages

Across Australia, beginning in the early 2000s, there was a significant shift in terminology from English as a Second Language (ESL) to English as an Additional Language (EAL) to English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EAL/D), which is represented in policy and curriculum documentation. This change occurred as an admirable attempt to recognise and alert teachers to the English language learning needs of speakers of other dialects such as Aboriginal English speakers. In some states, specific policies and resources have been developed with these learners in mind, for example, the Tracks to Two-Way Learning (Appendix, item 65) and the Koori English teacher guidance package (Appendix, item 40). Others have aimed to improve the identification of such learners in the classroom, such as the Identifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander EAL/D students document (Appendix, item 28). Through cross-jurisdictional efforts the Capability Framework: Teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander EAL/D learners (Appendix, item 17) was developed to provide guidance for teachers. Despite these important collective achievements, scholars have found that in most parts of Australia, the language learning needs of speakers of Indigenous contact languages remain under-recognised and these languages stigmatised in relation to traditional languages (McIntosh et al., Citation2012; Menzies, Citation2021; Sellwood & Angelo, Citation2013; Steele & Wigglesworth, Citation2023).

Whilst some jurisdictions appear to embrace the full spectrum of First Nations peoples’ language backgrounds, there are several states which remain simply focused on EAL rather than EAL/D and do not have specific resources for First Nations EAL/D learners. For some states, First Nations EAL/D learners are represented in the First Nations education section, and for others, they are represented in the EAL/D section. The intersectionality inherent to First Nations EAL/D learners is at times at odds with the compartmentalisation of Education Departments. For this reason, First Nations education policies have also been included in the policy search. Current policy throughout Australia focuses on the promotion and preservation of traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, which whilst crucially important, further highlights the marginal positions that contact languages hold in society and education systems. As previously mentioned, there were few states that have resources explicitly designed for this group of learners, despite research suggesting that their language learning needs differ in some very significant ways (Siegel, Citation2010; Steele, Citation2020). Again, such policy positions act to distract from, obscure, or deny, the diverse, multifaceted and holistic identities of First Nations peoples in the education system. These perceptions are mirrored in the representations portrayed in the media, as described next.

RQ2

Our analysis of news media items showed that Indigenous literacy was mostly represented as being ‘in crisis.’ However, the use of deficit terminology has reduced over time. First Nations languages featured more highly in the news and were represented in more diverse ways. However, the connection between language and culture was a dominant theme. Language rights are only minimally addressed and are limited to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages.

Literacy

Across the news media items, there were 1932 references to ‘literacy,’ however, since 2014 when literacy reporting peaked, this number has been steadily decreasing. Reporting frequently centred on Indigenous Literacy Day, NAPLAN results, approaches to teaching literacy (predominantly phonics or ‘back-to-basics’), and books/reading (including authors or author visits) generally. Of these, Indigenous Literacy Day and books/reading tended to be reported positively, whereas NAPLAN results and Indigenous literacy were not. For the latter, Indigenous literacy, or 'illiteracy', was represented as a ‘crisis’ using deficit terminology, including descriptions of the failure of education systems and the students themselves, as well as portrayals of funding being problematic. These perspectives were most dominant in 2012 and the years prior, although even until the present time they have continued to be represented in the media as shown thematically in the series of news headlines below:

Indigenous education, and particularly literacy or 'illiteracy' is often represented as a crisis:

‘Dire state of [I]ndigenous literacy’ (McIlwain, 10th August 2012, Illawarra Mercury)

‘Indigenous Education: Expert warns of crisis’ (The Advertiser, 17th September 2011)

‘Urgent action needed to boost [I]ndigenous education results’ (The Canberra Times, 15th May 2009)

‘Call for plan to tackle illiteracy’ (Ferrari, 24th December 2008, ABC News).

Reporting points to the failure of First Nations students, their teachers and the education systems:

‘Educators fail to lift [I]ndigenous literacy’ (ABC News, 8th August 2012)

‘One in three [I]ndigenous kids fail test’ (Ferrari, 23th December 2008, The Australian)

‘Aboriginal children fail basic school tests’ (Arup, 20th December 2008, The Age).

Headlines focus on the ‘gap’ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students:

‘Indigenous high school results widen the gap’ (Taylor, 11th October 2022, The Australian)

‘Indigenous gap won’t be closed this century’ (Baker, 8th April 2019, The SMH)

‘Federal failures cited as hopes fade of closing education gap’ (Robinson, 27th June 2012, The Australian)

‘Lack of basic literacy a major barrier to closing the gap’ (Western Times, 7th May 2009).

The reporting of funding for First Nations literacy programmes was represented in a range of ways from a ‘waste’ to a gift rather than a right, or as having strings attached to it:

‘Extra cash to aid Indigenous learners’ (Urban, 6th August 2021, The Australian)

‘“Indigenous-specific” programs are a $300 m waste’ (Hughes & Hughes, 27th June 2012, The Australian)

‘Government gives $30m for Indigenous students’ (ABC News, 9th September 2011)

‘$2.3b has a trade-offFootnote7’ (Moss, 30th December 2008, Centralian Advocate)

‘Govt pledges $2.3b to fight Indigenous illiteracy, Julia Gillard talks education standards’ (Crawford, 29th December 2008, ABC News).

There were occasionally attempts to reveal the complexities; however, concurrently, they maintained simplistic problem-solutions paradigms:

‘Literacy solutions not black and white’ (Ferrari & Owens, 9th August 2012, The Australian).

‘Back-to-basics’ literacy approaches commonly associated with rote learning and phonics for literacy learning (not EAL/D learning), such as Direct Instruction, featured highly:

‘Back-to-basics teaching helping youngsters read’ (Editorial, 30th October 2022, The Australian)

‘“Old-style” boost for remote students’ (Karvelas, 15th December 2012, The Australian).

Positive reporting of ‘literacy’ tends to focus on personal stories which display passion, inspiration, and hope:

‘Kiara shares her passion for literacy’ (Forbes Advocate, 6th August 2019)

‘Jess a hit spreading the word on literacy’ (Vivian, 9th June 2019, NT News)

‘Jack helps inspire kids leading light in literacy’ (Habib, 14th August 2012, Inner West Courier).

In the corpus for this study, the word ‘disadvantage’ was referenced 192 times, ‘fail*’ 116 times, and ‘gap’ 535 times with reference to Indigenous literacy. One marked difference in reporting in recent years is characterised by a greater use of term ‘First Nations,’ a significant focus on First Nations languages in education and a slow but gradual increase in positive reporting. For example, using the word stem ‘inspir*’ revealed 120 instances, with 72 of these references occurring from 2018 onwards. However, the word ‘pride’ only received 78 mentions and such usage has remained fairly consistent over time.

Language

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages have featured regularly in news media coverage over the period of analysis, and despite ‘literacy’ receiving greater levels of funding and policy attention over time (as described above), language has consistently received more attention. Since 2018 the number of references to language has notably increased. ‘Language’ was referenced 3776 times over the period with 1463 of those references occurring in the most recent 300 articles from the corpus. Language is represented in a wide variety of ways in the media, as shown thematically in the series of news headlines below. Broadly, language is portrayed as representative of culture. However, as with the reporting of literacy, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages are represented as being in a state of crisis, which is reflected in the use of life, death, and war metaphors, alongside calls to action. At times, languages are represented as a solution, one that brings hope and pride, but at other times, languages are represented as a ‘barrier to learning.’ Within news media coverage there has been a shift towards traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, and rarely are Indigenous contact languages represented.

The relationship between language and culture is often represented through death metaphors:

‘Class language limit “death of our culture”: Aboriginal school head’ (ABC News, 16th November 2008)

‘Language death has been likened to the death of a culture’ a quote from ‘Which way? The future of bilingual education’ (ABC News, 2nd December 2008)

‘Mind your language, culture under threat’ (Skelton & Topsfield, 6th December 2008, The Age).

Language lessons are often represented as culture or cultural lessons:

‘Indigenous culture classes rope children into a great education’ (Gooley, 19th October 2021, The SMH)

‘Indigenous lesson push’ (Herald Sun, 8th April 2022).

Language and culture is celebrated and associated with hopes and dreams, identity and pride:

‘Kids learn to hold their tongue with pride’ (Macarthur Chronicle, 29th July 2008)

‘Healing and pride through preschool kids learning language and culture’ (ABC News, 11th June 2022)

‘Language of success’ (Le May, 22nd November 2022, The West Australian)

‘Children celebrate Aboriginal culture by singing in Gamilaraay’ (Shumak, 19th June 2018, The Inverell Times)

‘Language forging unity’ (Barrett, 17th June 2021, The Australian).

Life, death, and war metaphors are prevalent in reporting:

‘Course to save language’ (Centralian Advocate, 13th March 2012)

‘Linguists fear Indigenous language extinction’ (ABC News, 1st March 2009)

‘Kaurna kids: How Jack Buckskin brought a dead language to SA classrooms’ (Walter, 28th May 2022, The Advertiser)

‘Keeping Language Alive’ (Burke, 17th November 2020, NT News)

‘Women on front line of language preservation’ (Liston, 8th April 2009, The Australian).

Use of the word ‘lostFootnote8’ distracts from the colonial intentionality behind the dispossession of First Nations languages:

‘Aboriginal communities throughout the rest of the country are attempting to recover their lost languages’ a quote from ‘Which way? The future of bilingual education’ (ABC News, 2nd December 2008)

‘Passionate revival of a lost language’ (Walter, 28th May 2022, The Advertiser).

Language is also presented as a barrier:

‘Language barriers: The door to learning Australian [I]ndigenous dialectsFootnote9 is slowly opening’ (Canna, 16th February 2012, Townsville Bulletin)

‘Breaking down language barriers boosts confidence’ (Chilcott, 6th October 2011, The Courier-Mail).

There are many calls to action and advocacy for the role of language in learning:

‘Speaking up for local talk’ (Sunday Times (Perth), 17th May 2009)

‘First language teaching essential for Indigenous education’ (Fitzgerald, 9th November 2018, Katherine Times)

‘Teaching in children’s first language boosts learning’ (Fillmore, 25th August 2019, The SMH).

Commentary recognises the significant social change and policy shifts occurring in Australia:

‘Indigenous language replaces state school foreign language studies’ (ABC News, 8th June 2022)

‘Teach us Australian languages’ (Jenkins, 8th April 2022, Geelong Advertiser)

‘Labor announces $14 m plan to expand Indigenous language education’ (Matthews, 31st March 2022, Katherine Times)

‘Schools dump French, Italian for Indigenous languages’ (Harris, 31st July 2020, The Daily Telegraph)

‘Exciting to see language taken seriously’ (The Gladstone Observer, 13th February 2018).

Discussion

From a decolonial perspective (Ahmed, Citation2021; Mignolo, Citation2011, Citation2021), the sovereign language rights of First Nations peoples are not centred either in policy or the reporting of news. Instead, as suggested by Farley et al. (Citation2021), there is a ‘persistent focus on a narrowly defined set of policies or a constrained set of potential solutions to policy problems’ (p. 168). In our analysis, we found educational equality is defined not by equal language rights, but rather by success in SAE literacy, as narrowly measured by NAPLAN. This is reflected in the description of ‘Indigenous literacy’ as being in crisis. Both this crisis, and its proposed solutions, reflect the ‘English-only, monolingual-centric assumptions’ (Cross et al., Citation2022, p. 1) that are central to Australia’s colonial education systems and structures. Yet, this position is rarely connected to the other dominant crisis, the preservation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages through school programmes. Without reference to the role schools have played in the creation of this problem, they are celebrated for ‘saving’ First Nations languages. The ‘fight’ for Indigenous literacy and the preservation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages distracts from how the current system created and maintains the same problems it seeks to address. In this discussion, we focus on how language education policies and news media coverage obscure the language rights and linguistic diversity of First Nations peoples to reproduce educational inequities in the Australian schooling system.

Language rights

Policy and media have largely failed to articulate the sovereign language rights of First Nations peoples in Australia, despite international pressure to do so. Language rights are minimally represented in curriculum documentation for learning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, and not mentioned at all in relation to English, and especially with regard to EAL/D learners. Importantly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages have been included in Australian schooling, but not in a way that challenges the dominance of SAE in the education system. Several examples of this were revealed in the media reporting. Language in the media, like schools, was broadly represented synonymously as culture, rather than a right. In their reporting of language, life, death and war metaphors acted to disguise colonial intentionality (particularly through the euphemism that languages were ‘lost’). In doing so, the media has been able to ‘divert attention from the root causes, complex structural forces, and historical and contextual circumstances’ (Farley et al., Citation2021, p. 168). At the same time words such as ‘pride,’ ‘healing’ and ‘unity’ suggest that current approaches to teaching First Nations languages are sufficient as a ‘solution’ to the ‘problem.’ Alternative positions were met with a sharp rebuke from the media, as well as those responsible for educational systems and policy.

In 2021, First Nations academic, Melitta Hogarth questioned the use of subject name ‘English’ in schools. She put forward that for many First Nations peoples, English is ‘the language of the oppressor’ and learning it represents an ‘act of assimilation’. Instead, she suggested renaming the subject English to ‘Language Arts’ or ‘Languages, Literacy and Communications’. However, it was met with outrage, and appeals to ‘common sense.’ Previous Federal Education Minister Alan Tudge labelled the suggestion as ‘nonsense’ and news article headlines reinforced this perspective:

‘Fury over push for the school subject ‘English’ to be renamed to avoid offending Indigenous Australians – but plan is labelled ‘political correctness gone mad’ (Mcphee, 14th August 2021, Daily Mail)

‘Day Common Sense Died’ (Bennett, 14th August 2021, Courier Mail).

Another example from 2012 highlights the struggle for language rights and how such claims are summarily dismissed. NT News reported that Professor Jane Simpson ‘told a House of Representatives committee that [I]ndigenous children had a right to be taught in their home language’ alongside the message that ‘there was an urgent need for specifically trained English as an additional language where Aboriginal children did not have English as their first language’ (NT News, 11th February 2012). The main point was that children had a right to be taught in their home languages, but instead, the headline read: ‘English classes call’. These examples effectively illustrate the ways in which language as culture is celebrated, whilst language as a right is actively resisted. In this resistance, appeals to ‘common sense’ are frequently used to dismiss any claims, and complexities are generally overlooked (Stack, Citation2007; Thomas, Citation2003, Citation2005). Instead, narrow conceptions of the ‘problem’ are produced to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages only occupy marginal positions in the curriculum and in schooling, hence not presenting a challenge to the status quo. In this way, linguistic and educational inequalities are maintained.

Language learner diversity

Although many are, not all First Nations children are language learners. For those First Nations children who are language learners, a diverse range of language backgrounds and language learning situations are represented. However, this diversity is rarely captured. Our policy analysis highlighted the challenges educators face in responding to language learner diversity in the classroom. In some cases, the compartmentalisation of EAL/D learning, language learning and First Nations education made policy navigation difficult. In others, it was the complexity of the policy documentation represented in a myriad of unclear synonyms that made policy difficult to decipher. These synonyms were not only unclear, but weak in terms of mandating a clear position in relation to EAL/D learners, their rights, and provisions. Under such obfuscation, intentional or otherwise, the relationship between language learning (and the diversity of language learning) and NAPLAN performance is subsumed to the crisis of ‘Indigenous literacy.’

‘Indigenous literacy’ as represented in the media, does not account for the EAL/D language learning needs of many First Nations children. Instead ‘literacy’ is represented as a ‘problem’ for all First Nations peoples. Additionally, literacy is narrowly measured by NAPLAN testing. Consequently, a narrow suite of ‘solutions’ have been offered, largely in the form of ‘back-to-basics’ literacy approaches (rather than EAL/D language learning approaches). At times, education policy has reinforced, rather than corrected, this position. NAPLAN results are reported for Indigenous students, and EAL/D learners, but are not disaggregated to represent Indigenous EAL/D learners. This absence of the ability to present alternative narratives through data limits the possibilities for fair representation and powerfully shapes public discourses, i.e. that poor literacy is related to Indigeneity rather than EAL/D status (Dixon & Angelo, Citation2014; Lingard et al., Citation2012). In these ways, policy and news media operate in concert to fuel deficit discourses surrounding First Nations peoples and, in doing so, further compound the ways in which First Nations children have been marginalised by the educational system.

Lastly, speakers of Indigenous contact languages and their languages continue to hold peripheral positions in education systems and society more broadly. Indigenous contact languages are rarely represented in media coverage whilst in policy and practice, speakers of Indigenous contact languages are not always recognised as EAL/D learners nor are sufficient resources available to support teachers to meet their language learning needs in the classroom (Sellwood & Angelo, Citation2013; Steele & Wigglesworth, Citation2023).

Conclusion

In the context of First Nations languages and language learners, we have argued ‘language’ is conflated with either ‘literacy’ or ‘culture’ to distract from the sovereign language rights of First Nations peoples in Australia. Drawing on Farley et al.’s (Citation2021) conception of ‘policy narrowing,’ it is clear that the singular focus on literacy as measured by NAPLAN testing ignores language learner diversity and, in doing so, acts as an instrument of colonial oppression for First Nations children in the schooling system. Likewise, media representation of language as a culture, narrow conceptions of language and euphemistic expressions are used to divert attention from language rights and acts of colonial violence. To counter this policy distraction and the surrounding discourses, we call on governing educational bodies to re-centre language rights and language learner diversity in policymaking. We hope that will also bring about change in the way media represents First Nations languages, literacy and learning.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge we live and work on unceded Whadjuk Noongar Boodja (Country) and pay our respects to Whadjuk Noongar peoples, past and present. We would like to extend our respects to all First Nations peoples across Australia and beyond. We acknowledge the sophisticated knowledge that First Nations peoples hold, that are eloquently expressed through their languages, and we work towards ensuring education systems embrace these knowledge and languages. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable feedback. Any errors are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carly Steele

Carly Steele, Dr, is a non-Indigenous Lecturer and early career researcher in the School of Education at Curtin University. She completed her PhD at the University of Melbourne in 2021 exploring the role of language awareness and the use of contrastive analysis for teaching standardised Australian English as an additional language and/or dialect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in primary school classrooms. Her current research focuses on how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, particularly new varieties, are positioned in schools, as well as culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and assessment practices.

Rhonda Oliver

Rhonda Oliver, Professor, has researched extensively and is widely published in the areas of second language and dialect acquisition, and task-based language learning, especially in relation to child and adolescent language learners in schools and universities. She is not Indigenous, however, for over a decade a considerable body of her work has involved studies within Australian Aboriginal education settings.

Notes

1 In this paper, we use terms such ‘First Nations’ and ‘Indigenous’ with reference to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their languages. We do so respectfully recognising that not all terms are equally accepted by all people. We have at times used these terms interchangeably to promote the readability of this paper, and at other times, our language choice reflects the source information.

2 Note: we use the plural form ‘peoples’ as this minority subset within the nation’s population is not homogenous, but rather made up of many diverse groups.

3 The term ‘Indigenous’ has been used here to reflect the media discourses around Indigenous literacy, which are also captured in the terminology of ‘Indigenous Literacy day’ (https://www.indigenousliteracyfoundation.org.au/ild).

4 The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) is a test administered to all students in years 3, 5, 7 and 9 for the purpose of benchmarking literacy and numeracy achievement standards nationally.

5 DI is a remedial literacy programme designed in the US for student with learning difficulties. It is not a language learning programme.

6 The acronym NAIDOC originally derives from ‘National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee’ and was initially a day of protest. It is now a week of celebrations held across Australia from the first week of July each year (https://www.naidoc.org.au/).

7 The ‘trade-off’ is the implementation of English-only teaching for the first four hours of school.

8 We would like to acknowledge the intellectual contribution of Max Lenoy for bringing this point to our attention.

9 The author is using the term ‘dialects’ incorrectly here and is referring to a language.

References

- Ahmed, Y. (2021). Political discourse analysis: A decolonial approach. Critical Discourse Studies, 18(1), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1755707

- Anderson, G. L. (2007). Media’s impact on educational policies and practices: Political spectacle and social control. Peabody Journal of Education, 82(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560709336538

- Angelo, D. (2011). NAPLAN implementation: Implications for classroom learning and teaching, with recommendations for improvement. TESOL in Context, 23(1 & 2), 53–73.

- Angelo, D. (2013). Identification and assessment contexts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners of standard Australian English: Challenges for the language testing community. Papers in Language Testing and Assessment, 2(2), 67–102.

- Angelo, D., & Hudson, C. (2020). From the periphery to the centre: Securing the place at the heart of the TESOL field for First Nations learners of English as an additional language/dialect. TESOL in Context, 29(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.21153/tesol2020vol29no1art1421

- Australian Council of TESOL Associations (ACTA). (2022). National roadmap for English as an additional language of dialect education in schools, directions for COVID-19 recovery and program reform.

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (n.d.). Framework for Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Islander Languages. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/languages/framework-for-aboriginal-languages-and-torres-strait-islander-languages/.

- Baker, P. (2004). Querying keywords: Questions of difference, frequency, and sense in keywords analysis. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(4), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424204269894

- Baker, P. (2006). Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum.

- Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., Khosravinik, M., Krzyżanowski, M., McEnery, T., & Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), 273–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508088962

- Blackmore, J., & Thorpe, S. (2003). Media/ting change: The print media's role in mediating education policy in a period of radical reform in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Education Policy, 18(6), 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093032000145854

- Brown, L. (2018). Indigenous young people, disadvantage and the violence of settler colonial education policy and curriculum. Journal of Sociology, 55(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783318794295

- Clyne, M. (1997). Language policy in Australia—Achievements, disappointments, prospects. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.1997.9963442

- Cross, R., D’warte, J., & Slaughter, Y. (2022). Plurilingualism and language and literacy education. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 45(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00023-1

- Dawkins, J. (1991). Australia’s language: The Australian language and literacy policy. Australian Government.

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DoITRDC), Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) & Australian National University (ANU). (2020). National Indigenous languages report (NILR). Australian Government. https://www.arts.gov.au/what-wedo/indigenous-arts-and-languages/national-indigenous-languages-report

- De Sousa Santos, S. B. (2021). Postcolonialism, decoloniality, and epistemologies of the south. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature.

- Dickson, G. (2019). Aboriginal English(es). In L. Willoughby & H. Manns (Eds.), Australian English reimagined (pp. 134–154). Routledge.

- Dixon, R. M. (2019). Australia’s original languages: An introduction. Allen and Unwin.

- Dixon, S., & Angelo, D. (2014). Dodgy data, language invisibility and the implications for social inclusion. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 37(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.37.3.02dix

- Doolan, J., & Blackmore, J. (2018). Principals’ talking back to mediatised education policies regarding school performance. Journal of Education Policy, 33(6), 818–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1386803

- Dovchin, S. (2020). Introduction to special issue: Linguistic racism. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(7), 773–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1778630

- Edelman, M. (1988). Constructing the political spectacle. University of Chicago Press.

- Ellinghaus, K. (2003). Absorbing the ‘Aboriginal problem’: Controlling interracial marriage in Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Aboriginal History, 27, 183–207.

- Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Farley, A. N., Leonardi, B., & Donnor, J. K. (2021). Perpetuating inequalities: The role of political distraction in education policy. Educational Policy, 35(2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904820987992

- Fforde, C., Bamblett, L., Lovett, R., Gorringe, S., & Fogarty, B. (2013). Discourse, deficit and identity: Aboriginality, the race paradigm and the language of representation in contemporary Australia. Media International Australia, 149(1), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1314900117

- Fillmore, N. (2023, November 21). Visibilising raciolinguistic ideologies in Australian media coverage of childhood multilingualism and language education. Applied Linguistics Association of Australia Conference, University of Wollongong, Wollongong.

- Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

- Fogarty, W., Riddle, S., Lovell, M., & Wilson, B. (2017). Indigenous education and literacy policy in Australia: Bringing learning back to the debate. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 47(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2017.18

- Giroux, H. A. (2013). The new extremism: Politics of distraction in the age of austerity. Philosophers for Change. http://philosophersforchange.org

- Giroux, H. A. (2017). America’s education deficit and the war on youth: Reform beyond electoral politics. Monthly Review Press.

- Hattie, J. (2015). What doesn’t work in education: The politics of distraction. Pearson.

- Hogarth, M. (2019). Y is Standard Oostralin English da Onlii meens of Kommunikashun: Kountaring White Man Privileg in da Kurrikulum. English in Australia, 54(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.224527

- Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language policy. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137316202

- Lingard, B., Creagh, S., & Vass, G. (2012). Education policy as numbers: Data categories and two Australian cases of misrecognition. Journal of Education Policy, 27(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.605476

- Lingard, B., & Rawolle, S. (2004). Mediatizing educational policy: The journalistic field, science policy, and cross-field effects. Journal of Education Policy, 19(3), 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093042000207665

- Lo Bianco, J. (2008). Language policy and education in Australia. In S. May & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (2nd ed., pp. 343–353). Springer.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2016). Multicultural education in the Australian context: An historical overview. In J. L. Bianco & A. Bal (Eds.), Learning from difference: Comparative accounts of multicultural education (Multilingual Education 16, pp. 15–33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26880-4_2

- Macqueen, S., Knoch, U., Wigglesworth, G., Nordlinger, R., Singer, R., McNamara, T., & Brickle, R. (2018). The impact of national standardized literacy and numeracy testing on children and teaching staff in remote Australian Indigenous communities. Language Testing, 36(2), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532218775758

- Malcolm, I. G. (2018). Australian Aboriginal English: Change and continuity in an adopted language. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501503368

- McCallum, K., & Waller, L. (2022). Un-braiding deficit discourse in Indigenous education news 2008–2018: Performance, attendance and mobility. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1817115

- McIntosh, S., O’Hanlon, R., & Angelo, D. (2012). The (in)visibility of “language” within Australian educational documentation: Differentiating language from literacy and exploring particular ramifications for a group of “hidden” ESL/D learners. In C. Gitaski & R. B. Baldauf Jr (Eds.), Future directions in applied linguistics: Local and global perspectives (pp. 447–468). Cambridge Scholars.

- Menzies, I. (2021). Language is connection: The attitudes of education staff in Kununurra, Western Australia towards Indigenous languages and multilingualism [Master thesis]. University of Oxford.

- Mignolo, W. (2011). The darker side of western modernity: Global futures decolonial options. Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2021). The politics of decolonial investigations. Duke University Press.

- Mockler, N. (2020). Discourses of teacher quality in the Australian print media 2014–2017: A corpus-assisted analysis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(6), 854–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1553849

- Moodie, N., Maxwell, J., & Rudolph, S. (2019). The impact of racism on the schooling experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: A systematic review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00312-8

- Norman, H., Krayem, M., Bain, C., & Apolonio, T. (2020). Are Aboriginal people a threat to the modern nation? A study of newsprint coverage of a racial discrimination complaint. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 18–35. https://doi.org/10.3316/agispt.20200624032173

- Piller, I., & Cho, J. (2013). Neoliberalism as language policy. Language in Society, 42(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404512000887

- Poetsch, S. (2020). Unrecognised language teaching: Teaching Australian curriculum content in remote Aboriginal community schools. TESOL in Context, 29(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.21153/tesol2020vol29no1art1423

- Rodríguez Louro, C., & Collard, G. (2021). Australian Aboriginal English: Linguistic and sociolinguistic perspectives. Language and Linguistics Compass, 15(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12415

- Rowe, E. (2019). Reading Islamophobia in education policy through a lens of critical race theory: A study of the ‘funding freeze’ for private Islamic schools in Australia. Whiteness and Education, 5(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/23793406.2019.1689159

- Sellwood, J., & Angelo, D. (2013). Everywhere and nowhere: Invisibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contact languages in education and Indigenous language contexts. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 34(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.36.3.02sel

- Siegel, J. (2010). Second Dialect Acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

- Spade, D. (2011). Law as tactics. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 21(2), 40–71.

- Stack, M. (2007). Constructing ‘common sense’ policies for schools: The role of journalists. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(3), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701373649

- Steele, C. (2020). Teaching standard Australian English as a second dialect to Australian Indigenous children in primary school classrooms [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Melbourne.

- Steele, C., & Wigglesworth, G. (2023). Recognising the SAE language learning needs of Indigenous primary school students who speak contact languages. Language and Education, 37(3), 346–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.2020811

- Thomas, A., Jakubowicz, A., & Norman, H. (2019). Does the media fail Aboriginal political aspirations? 45 years of news media reporting of key political moments. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Thomas, S. (2003). “The trouble with our schools”: A media construction of public discourses on Queensland schools. Discourse, 24(1), 19–33.

- Thomas, S. (2005). Education policy in the media: Public discourses on education. Post Pressed.

- Vass, G. (2014). Putting critical race theory to work in Australian education research: ‘We are with the garden hose here’. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0160-1

- Vaughan, J., & Loakes, D. (2020). Language contact and Australian languages. In R. Hickey (Ed.), Handbook of language contact (pp. 717–740). Wiley.

- Waller, L. J. (2012). Bilingual education and the language of news. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 32(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2012.744267

- Weuffen, S., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., & Thompson, K. (2023). Sovereign and pseudo-hosts: The politics of hospitality for negotiating culturally nourishing schools. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00599-0

- Wigglesworth, G., Simpson, J., & Loakes, D. (2011). NAPLAN language assessments for Indigenous children in remote communities: Issues and problems. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 34(3), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.34.3.04wig