ABSTRACT

English-medium instruction (EMI) is on the rise around the world due to globalization, internationalization and neoliberal ideologies which equate English with social capital, prestige, and success in the labour market. While many EMI policies aim to equip students with English as a ‘lingua academia’, produce ‘neoliberal subjects’ and compete in university ranking systems, such policies often overlook larger sociolinguistic, sociohistorical, and sociopolitical issues at play. This article shares findings from a collaborative autoethnography (CAE) involving the three authors as participants, who are based in three global contexts: Australia, Bangladesh, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Upon analysis of a series of dialogues amongst the authors, ‘policy distractions’ in EMI higher education were identified which resulted in the sidelining of critical issues related to native-speakerism, translingual discrimination and precarious conditions of students’ translingual practice, (lack of) choice around the medium of instruction, and the postcolonial legacy of unequal Englishes. The paper ends with suggestions for ways in which current EMI policies can be unpacked and disrupted to address larger and more pressing issues connected with complexities and intersections of social and linguistic justice.

1. Introduction: English-medium instruction and policies

English-medium instruction (EMI) is on the rise worldwide due to globalization, internationalization and neoliberal ideologies which equate English with social capital, prestige, and success in the labour market. EMI is commonly defined as, ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the majority of the population is not English’ (Macaro, Citation2018, p. 1). However, as Macaro (Citation2018) states, this definition ‘is deliberately open to challenge’ (p. 1). As Jenkins and Mauranen (Citation2019) state, one reason EMI is hard to define in a global sense is that its use varies dramatically according to local context.

In this article, we broaden Macaro’s (Citation2018) definition of EMI in two ways. Firstly, we relate the phenomenon of EMI not only to countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the majority of the population is not English, such as Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), but we also include universities in Anglophone countries, such as Australia, where, within the walls of the university, often speakers have an L1 other than English. Especially, elite universities in Britain, Australia, and North America (BANA) tend to attract a high number of international students, such as the University of Oxford and the University of St Andrews where 46% and 45% of the total student body is international, respectively (University of Oxford Facts and Figures, Citation2023; University of St Andrews Facts and Figures, Citation2023). A second way in which we broaden the definition of EMI is by recognizing that the ‘I’ for ‘instruction’ is only one part of university experiences. English language policies can also be found in the linguistic landscape or ‘educationscape’ (Krompák et al., Citation2022) of universities, via their websites as ‘virtual landscapes’ (Keleş et al., Citation2019), as well as in social spaces and faculty research culture. In this sense, a discussion of EMI policies needs to be widened to include English-medium ‘education’ (EME) rather than only ‘instruction’. As Dafouz and Smit (Citation2016) point out, multilingualism and translingualism are features of internationalized universities, making the concept of ‘English-medium education in multilingual university settings’ (EMEMUS) a more inclusive and representative term than EMI alone.

A growing body of research on EMI exists, especially since the 2000s (Macaro, Citation2018). However, many of the existing studies focus on challenges of EMI in classrooms through the eyes of students and teachers (Doiz & Lasagabaster, Citation2021; Costa & Mariotti, Citation2021; Hopkyns, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Rose, Citation2021; Shepard & Morrison, Citation2021; Sultana, Citation2014). A growing number of studies have also focused on ‘post-colonial hierarchies’ (Hornberger & Korne, Citation2017) and ‘hierarchical multilingualism’ (Mohanty, Citation2010) whereby the symbolic, social, and material power of English is investigated in EMI settings, especially in Asian contexts (Hamid & Sultana, Citation2024; Manan, Citation2021; Phyak & De Costa, Citation2021; Sah, Citation2020; Sultana, Citation2023b; Tupas & Metila, Citation2023). While teaching and learning, classroom challenges, and post-colonial hierarchies have been at the center of previous EMI studies, to the best of our knowledge, there has yet to be a study looking explicitly at EMI policies as ‘distractions’. The purpose of our study is to delve deeply into EMI policies and the aims behind them in the three global higher education contexts of Australia, Bangladesh, and the UAE. The contexts were chosen due to our access to, and experience of, these EMI settings as well as the varied dynamics they represent in terms of location, culture, and linguistic ecologies. Such contexts, in their diversity, relate to and have similarities with a variety of other EMI contexts globally, and thus contribute to mainstream EMI research. Via the relatively recent reflexive method of collaborative autoethnography (CAE) (Chang et al., Citation2013), we discuss ways in which current policies serve to distract from crucial and overlooked issues.

This article begins by defining the key concepts relevant to the study, including the politics of distraction, neoliberalism, and the methodology of CAE. After presenting key concepts in relation to existing literature, the article presents the study, and shares findings from our CAE involving a series of online dialogues between the three authors as participants, as well as ‘place’ and ‘artefacts’ also being considered participants. The article concludes by making practical suggestions for addressing issues which current EMI policies overlook due to the politics of distraction.

2. Understanding the politics of distraction

The concept of ‘distraction’ is usually defined as something that prevents someone from concentrating on something else. The politics of distraction have been explored across disciplines and have become particularly relevant in today’s era of neoliberalism, neonationalism and precarity. In an applied sense, the politics of distraction can be seen in the strategic or manipulative effort by the powerful to mislead or misdirect people in order to cover or hide more critical issues which may be harder to address. A classic example of a powerful figure who regularly uses the politics of distraction, is Donald Trump. Trump strategically and repeatedly employs ‘distraction techniques’ (Gabbatt, Citation2017) to sidetrack critical issues. He does this by choosing to highlight more trivial matters which he dresses up as ‘bright, shiny objects (BSOs)’ (Leibovich, Citation2015) through linguistic devices such as empty intensifiers and puffery (McIntosh, Citation2020). Such distraction techniques have earned Trump the nickname of ‘super spreader of distraction’ (Glasser, Citation2020), whereby discourse is catapulted away from serious and more complex issues. While extreme in the case of Trump, such distraction techniques are not uncommon amongst politicians in general, and indeed amongst decision-makers and public figures in other disciplines.

In the case of education, Hattie (Citation2015) points out that critical issues in schools are often left unaddressed due to a host of policy distractions which focus on ‘fixing’ individual elements rather than more holistic approaches to educational reform. For example, Hattie (Citation2015) explains that there is a widely held belief that smaller class sizes improve learning. Often, to appease parents, reforms focus on reducing class sizes as a way of improving learning outcomes. However, research has shown that teachers do not necessarily change their teaching style according to the class size (Hattie, Citation2015). In this sense, the focus on reducing class sizes acts as a policy distraction for more critical and complex issues such as content and effectiveness of lessons.

Many educational policies in today’s world are influenced by neoliberalism. Neoliberalism, as a ‘predatory global phenomenon’ (Giroux, Citation2014, p. 1), can be equated to ‘economic Darwinism’ (Giroux, Citation2014, p. 1), whereby privatization, commodification, free trade, and deregulation are promoted above all else. Neoliberalism serves to privilege personal responsibility over larger social forces and tends to widen divides between the most powerful groups and least powerful groups (Sultana, Citation2023a). Neoliberal ideologies prize individualism, competition, and self-interest. In higher education, the ethos of neoliberalism can most obviously be seen in the desire for universities to compete in league tables via internationalization and profit (Barnawi, Citation2018), in a similar way to how businesses operate. As Giroux (Citation2014) points out, such a mentality leads to critical learning being replaced with ‘master test-taking, memorizing facts, and learning how not to question knowledge and authority’ (p. 6). This is paired with ‘shallow consumerism’ (Naidoo et al., Citation2011) and the politics of disengagement. In other words, neoliberal forces may work as distractors for an effective implementation of educational policies.

3. The politics of distraction in English-medium education language policies

In a similar way to general educational policies, language policies in English-medium universities extend beyond instruction and take many forms. Language policy includes language ecologies, language ideologies, and language management (Spolsky, Citation2004). Often language management involves ‘direct effort to manipulate the language situation’ (Spolsky, Citation2004, p. 8) and it is influenced by language ideologies, which are often deeply ingrained in societies and amongst stakeholders. A related concept to language policy is ‘agency’. In relation to language policy and planning (LPP), agency takes the form of strategies undertaken by actors to bring about deliberate language change in a community of speakers (Kaplan & Baldauf, Citation1997). At a top-down level, strategies involve campaigns, visions, and infrastructures and at a bottom-up level, strategies include practices of individuals that accommodate or contest top-down policies to varying degrees (Hopkyns, Citation2023). Agency is closely connected to affordances and stakeholders exercise their agency to engage with anticipated benefits and opportunities (Jiang & Zhang, Citation2019).

Neoliberal based language policies in English-medium education multilingual university settings (EMEMUS) aim to equip students with English as a ‘lingua academia’, produce ‘neoliberal subjects’ (De Costa et al., Citation2020) and climb rankings. As universities strive to achieve such goals, many policies are influenced by the need to ‘get ahead’, make money and leave a mark on the global stage. EMI tends to be collectively associated with capital and is marketed as such. The focus on EMI as capital represents a ‘bright, shiny object’ (Leibovich, Citation2015) which deflects attention away from larger and more pressing sociolinguistic, sociohistorical, and sociopolitical issues surrounding EMI. In this sense, neoliberal directed policies often sideline larger critical issues which are inherent to the phenomenon of EMI itself, such as the postcolonial legacy of unequal Englishes (De Sousa Santos, Citation2021) and the phenomenon of ‘native-speakerism’ (Holliday, Citation2018). Native-speakerism, in Holliday’s (Citation2005) words, is ‘an ideology that upholds the idea that so-called ‘native speakers’ are the best models and teachers of English because they represent a ‘Western culture’ from which spring the ideals both of English and of the methodology for teaching it’ (p. 6). This distorted view, which is common globally (Hopkyns, Citation2022), supports a ‘vested interest’ in promoting an ‘ideologically constructed brand’ which equates ‘native speakers’ with ‘quality’ which in turn brings prestige to institutions (Phillipson, Citation1992). Neocolonial and neoliberal policies connected to ‘native speaker’ hiring biases distract attention from the critical need to combat language hierarchies and the postcolonial legacy of unequal Englishes.

Furthermore, critical issues such as lack of choice and agency around medium of instruction, are also often overlooked due to EMI being viewed as an ‘unstoppable train’ which is ‘beyond the control of policymakers and educational researchers’ (Macaro, Citation2018, p. 1). Although neoliberal ideologies stress the importance of individual choice, there is a neoliberal paradox in relation to EMI policies in some contexts. For example, in the context of the UAE, there is little choice but to take degree programs in the medium of English (Hopkyns, Citation2023). Viewing students as ‘autonomous choosers’ (Peters & Marshall, Citation1996) is positioned as ‘a pivotal mechanism to improve access and educational outcomes for all’ (Naidoo et al., Citation2011, p. 1154). However, often such goals disregard the fact that the nature of choice is contextually and socially embedded (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1999). In this sense, choice and agency are not detached from social structure. Structure, or recurrent patterned arrangements, often influences or limits choices and opportunities (Barker, Citation2005). Structure, which includes policies informed by dominant ideologies and agendas, influences behaviour and at the same time individuals are capable of changing the social structures they inhabit (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966).

In EMEMUS, a further notable and critical area which is sidelined is linguistic diversity on campuses. While policies may advocate for inclusion and support diversity, hidden agendas can be found in English-dominated educationcapes and in monolingual assessments (Shohamy, Citation2006) which affect how languages are perceived, in terms of power relations, hierarchies and belonging (Sultana, CitationForthcoming). To summarize, in the creation and implementation of certain neoliberal-based English language policies, larger and more critical aspects may be ignored and undiscussed, either consciously or unconsciously.

4. Methodological orientations

4.1. Collaborative autoethnography (CAE)

The relatively recent qualitative method of collaborative autoethnography (CAE) combines self-reflexivity, cultural interpretation, and multi-subjectivity (Chang et al., Citation2013; Dovchin et al., Citation2023) via ‘the study of two or more contrasting lived experiences of author-researchers on a shared phenomenon’ (Rose et al., Citation2020, p. 260). When conducting a CAE, researchers ‘enter into deep conversations, examine their own and the deep-seated beliefs of their interlocutors and, as a result, reconceptualize their perspectives and actions’ (Werbińska, Citation2020, p. 270). By building on each other’s stories, gaining insights from group sharing, and providing various levels of support, researchers ‘interrogate topics of interest for a common purpose’ (Chang et al., Citation2013, p. 23). As Yazan and Keleş (Citation2022) state, the process of authoethnography can be therapeutic and allow researchers to ‘practice vulnerability’ via the frame of auto (self), ethno (culture) and graphy (narration) (Keleş, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). CAE can follow different approaches along a spectrum (Keleş, Citation2022) from ‘interpretive narration’ (Ellis, Citation1999, Citation2004) which is embedded in emotional self-reflexivity and leans more heavily on evocative and heartfelt accounts, to the ‘analytical approaches’ (Anderson, Citation2006) which involve ‘narrative interpretation’ and are more akin to conventional ethnographies grounded on ethnographic data collection, analysis and interpretation (Chang et al., Citation2013). The analytical approach tends to be more widely adopted for not only personal topics but also professional ones (cf. Sultana et al., Citation2023). For our CAE, we take an analytical approach to investigate EMI policies at our universities, in three global settings, through the lens of the politics of distraction.

Previous applied linguistics studies which have employed CAE as a research method have focused on issues such as transnational academics’ sense of ‘home’ (Yazan & Keleş, Citation2022) ‘native-speakerism’ (Lowe & Kiczkowiak, Citation2016; Rose & Montakantiwong, Citation2018), teacher-training courses (Huang & Karas, Citation2020), professional identity (re)construction of L2 writing scholars (Kim & Saenkhum, Citation2019), linguistic diversity and inclusion (Hopkyns & van den Hoven, CitationForthcoming), and teacher and learner identities (Werbińska, Citation2019), to name only a few. CAEs can be face-to-face, hybrid or online. In our case, due to being in three different countries, our discussions took place on Zoom. In this sense, our collaborative autoethnography resembled Huang and Karas’s study (Citation2020) which utilized Zoom as a way of recording dialogues.

We believe that collaborative writing, based on multi-sited ethnography, moves the format of publications away from Eurocentric and colonial scholarly enterprise. We can challenge the status quo and the promotion of monologic representations of a single authoritative voice – historically dominated by middle-class white males in academia (Dovchin et al., Citation2023). We make our text dialogic and polyphonic, employing multivocality individually and collectively (Yazan & Keleş, Citation2022), by integrating our personal narratives from varied contexts to bring nascent understanding about policy distractions in EMI – which itself is a colonial enterprise (see Deumert & Makoni, Citation2023). By including multiple researcher voices as well as adopting dual roles as both researchers and participants, the power amongst us as researcher-participants is diffused through collaboration.

4.2. Our collaborative autoethnography on policy distractions in EMI higher education

The purpose of our study was to reflect upon EMI policies at our universities through the lens of the politics of distraction. This took place via a series of online synchronous conversations using the Zoom platform, which were recorded and transcribed. Our dialogues were divided into three parts based on a set of three guiding questions, as seen in . The guiding questions were designed to address the key research question below:

RQ: From the perspective of three university teachers, how do the politics of distraction interact with EMI policies in the higher education contexts of Australia, Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates?

Table 1. Guiding questions and date of the Zoom dialogues.

4.3. Participants in our CAE: researchers, place, and artefacts

As sociolinguists we had a mutual interest in researching social questions revolving around language policies in our universities. However, we differed in terms of background, life experiences and professional contexts, amongst other factors. Such differences allowed us to approach the guided questions from varied positions. Our dialogues encouraged richer interpretations through interaction and questioning (Sawyer & Norris, Citation2013). In addition, the dialogues featured artefacts to enhance our investigation. For example, we shared photographs of signage and classrooms from our universities to demonstrate our points (Huang & Karas, Citation2020; Sawyer & Norris, Citation2013). Although the Zoom discussions took place in May 2023 during a relatively short and concentrated period, we reflected upon the much longer time periods we had been at our respective research contexts. Each Zoom call lasted between 30 and 40 minutes, and data included our written notes prior to the meetings, our conversations (based on written notes) and artefacts we shared with each other (e.g. signage from our universities’ linguistic landscapes). Considering our roles as researchers-participants, in the following section, we provide brief summaries of how we began working together, our positions as academics and the sociolinguistic background to our university contexts.

4.4. Researcher roles and sociolinguistic contexts

Sender (R2) and Shaila (R3) first met in Australia as PhD students as they had the same supervisor, Alastair Pennycook. Sarah (R1) then met Sender (R2) and Shaila (R3) for the first time at the 24th Sociolinguistics Symposium in Ghent, Belgium in the summer of 2022.

Sarah (R1) is from the UK. She is also a citizen of Canada. She considers herself a ‘transnational mobile academic’ (Van den Hoven & Hopkyns, Citation2023) as she has lived and worked in higher education in many global contexts including Japan, Canada, and the UAE over the last 20 years. She moved to the UAE in 2012 and was an assistant professor at a government university in Abu Dhabi until summer 2023, when she moved to her current university in the UK. EMI is dominant in UAE higher education, regardless of the type of university (international branch campuses, private universities, and state universities). At Sarah’s university, almost all students are Emirati nationals with Arabic as their L1 and English as their L2. Students have a range of linguistic backgrounds depending on their schooling and family histories, amongst other factors. Faculty at the university are from a range of different countries, reflecting the wider demographics of the UAE. Until relatively recently, Sarah’s university had a foundation program where students worked toward achieving a band of IELTS 5.5 to progress to the EMI university colleges. As EMI has grown in UAE schools, the foundation programs were deemed unnecessary and plans to phase them out began in 2017, with only in-sessional support to remain (Pennington, Citation2017). Almost all the courses in UAE universities are taught via EMI, except certain programs like Islamic Studies or Shar’ia Law.

Sender (R2) has a Mongolian heritage. She moved to Australia from Mongolia in early 2000s to pursue her postgraduate degrees. After gaining her Masters’ and PhD from an Australian university, she started working as a researcher and lecturer at public universities in Japan and Australia. Currently, she is a Professor at a public university in Australia and an Australian Research Council Fellow. She teaches several applied linguistic related courses, which consist of a large cohort of both international and local students. She also supervises postgraduate students who seek MA and PhD degrees in applied linguistics. In Sender’s university, international students are required to score 6.5 in IELTS to meet the entrance requirements and to be accepted for their degree programs. All the courses in Australian universities are run through EMI. Australia is considered an EMI context in a broad sense, as over 8 million international students are enrolled in its universities, which contributed over 25.5 billion dollars to the economy in 2022 (Universities Australia, Citation2023). Most of this population were / are English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners.

Shaila (R3) is from Bangladesh. She teaches at a public university in Dhaka, which is the oldest university in the country and secures a prestigious position in society because of its presumed high level of education and competitive admission test. As a Professor of Applied Linguistics in the department of English language, Shaila teaches BA in ESOL and MA in TESOL programs, and supervises MA, MPhil, and PhD students at her university’s Institute of Modern Languages. English is an important academia lingua franca in higher education in Bangladesh. However, its role, function, and significance differ based on the nature and demographic location of universities. In Shaila’s university, all the courses in the department are expected to be taught in English. However, because of the nationalistic discourses existing in the public sector, students’ lack of comprehension of the course content, and teachers’ awareness of the role of L1 in learning and as a pedagogical resource, teachers seem to switch to Bangla when and if necessary. However, classroom materials, coursebooks, assignments, research papers, student-teacher correspondence, student and teacher research and exam papers are written in English. Even though teachers have flexibility of using Bangla in the classroom, the dominant language in the educational space of the department is English. However, the private higher education has distinctly different linguascape. In the name of internationalization and for the prevalence of neoliberal and capitalist ethos, English is given highest priority for all kinds of academic and administrative purposes. English is also the medium of instruction too. Shaila has strong engagement with private higher education in different capacities. For example, she is now the Director of BRAC Institute of Languages, BRAC University - one of the top-most private universities in Bangladesh.

4.5. Data analysis

For our data analysis, we downloaded our Zoom video files and Zoom transcriptions and we manually checked transcriptions for accuracy via collaborated meetings. We followed Chang et al.’s (Citation2013) recommendation for analysis of analytical CAEs which involved thematic data analysis. The analysis centered around three clusters of activity: (1) reviewing data; (2) segmenting, categorizing, and regrouping data; (3) finding themes and reconnecting with the data. Firstly, reviewing took place at the macro and micro level. Macro reviewing involved gaining a holistic sense of the whole data via noting down recurring topics, details, patterns, and relationships (Chang et al., Citation2013). At the micro level, we reviewed data within segments, divided by data types (written reflections which we prepared before the Zoom calls, the Zoom conversations themselves, and artefacts / images shared). True to the CAE methodological approach, ‘artefacts’ were also viewed as participants in that they spoke to and represented the social reality of our contexts. In our micro level analysis, we also looked at each researcher’s case separately to then compare and contrast geographical contexts and realities. Secondly, after gaining initial codes from the review process, we looked for micro-codes by segmenting data. As Chang et al. (Citation2013) explain, coded data becomes ‘mobile’ decontextualized fragments that can be taken out of context and grouped with other fragments. Thirdly, once categories were established, there was a need to merge multiple categories. The reduction of topical categories resulted in the formation of key themes. We discussed the meaning of themes or ‘significant strands’ together and decided on our section headings for the writing up of our study.

5. Findings – a dialogic investigation of EMI policy distraction in three global contexts

To address our research question on how the politics of distraction interact with EMI policies in the higher education contexts of Australia, Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates, we identified key themes, or significant strands, in each of the three dialogues, as seen in the following sections.

5.1. Dialogue 1: goals behind EMI in three global contexts

In our first Zoom discussion we discussed our first guiding question ‘What are the goals behind EMI policies in the contexts of three global universities located in Australia, Bangladesh, and the UAE?’ A significant strand of this conversation related to neoliberal and (neo)colonial policy distractions, as can be seen in Extract 1. Shaila began by discussing the context of Bangladesh and the colonial ideologies and divisions which continue via EMI.

Extract 1: EMI carrying the spirit of both colonialism and neoliberalism

Dialogue 1 continued with Sarah discussing tensions and divisions arising from varying school backgrounds in the case of the UAE. On a related note, Sender discussed the prestige of standardized English over translingual practice in the Australian context (Extract 2).

Extract 2: the prestige of standardized English over translingual practice

A third significant strand identified in Dialogue 1 relates to a gap between ‘policy talk’ and ‘policy walk’ regarding linguistic diversity and inclusion (Extract 3).

Extract 3: gap between ‘policy talk’ and ‘policy walk’ in relation to linguistic diversity and inclusion

5.2. Dialogue 2: policy distractions and critical issues overlooked

In Dialogue 2, we addressed our second guiding question ‘What are the main policy distractions in the three universities?’. The first significant strand of this dialogue was the lack of choice over medium of instruction (Extract 4).

Extract 4: lack of choice over medium of instruction (MOI)

A second significant strand to emerge from Dialogue 2 was the hiring of ‘native speaker’ teachers and US and UK-centric material used in EMI classrooms, as seen in Extract 5.

Extract 5: focus on hiring of ‘English native speakers’ and US / UK-centric materials

A third significant strand to emerge from Dialogue 2 is the focus on standardized or ‘bookish’ English, which in turn affected ways of learning through a reliance on memorizing and accuracy without meaning and creativeness, as seen in Extract 6.

Figure 4. Monolingual ‘SPEAK ENGLISH ONLY’ campus sign (Dobinson & Mercieca, Citation2020).

Extract 6: preference for standardized or ‘bookish English’

5.3. Dialogue 3: the need for policy disruptions to address overlooked issues

In the final Zoom discussion, we discussed the third guiding question ‘How can policy makers address critical issues which have been overlooked in current EMI policies?’. Significant strands of Dialogue 3 included valuing, including, and making linguistic diversity visible as well as promoting translingual socialization (Extract 7).

Extract 7: valuing linguistic diversity and promoting translingual socialization

6. Discussion and conclusion

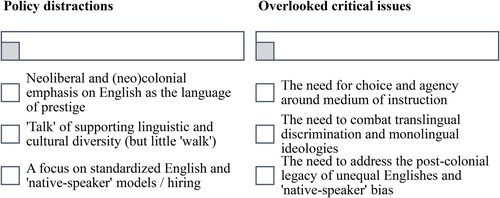

From the findings section of this article (Extracts 1–7), three main policy distractions emerged across the dialogues, which resulted in more critical issues being sidelined ().

6.1. Greater agency over medium of instruction to combat neoliberal and (neo)colonial emphasis on the dominance of English

Firstly, a neoliberal and colonial emphasis on English monolingualism, due to the symbolic prestige of English, acted as a policy distraction across the three contexts, to varying degrees. This policy distraction diverted attention away from the importance of choice and agency around medium of instruction. For example, in Dialogue 1, Shaila stated that English-medium programs at her Bangladeshi university represented ‘a hydra-like creature’ in that they carried the spirit of both (neo)colonialism and neoliberalism. Kramsch (Citation2019) makes a similar point when pointing out how language education is in the crossfire between colonialism and globalization. Shaila went on to state that EMI in these programs served to ‘reinstate the language of the British colonizer with new vigour’, which had the effect of sharpening binaries between those who speak English well and those who do not. Because the English-speaking elite hold the power, despite official mandates to treat English as a foreign language, English continues to hold an ‘uncanny prestige’ and continues to be used as a medium of instruction in many cases (Roshid & Sultana, Citation2023). Similar situations have been found in other Asian contexts such as in Pakistan (Manan, Citation2021) and Nepal (Sah, Citation2020), where EMI is strongly attached to neoliberalism and prestige.

Across the dialogues, it was recognized that the social background of students greatly affects access to English and in turn university experiences. By teachers placing ‘bookish English’ expectations on students due to their own neoliberal monolingual ideologies, students often struggle and resort to memorizing large sections of text. In this sense, classroom practices resemble the ‘banking concept of education’, which, according to Freire (Citation1970) is an ‘instrument of dehumanisation’ (p. 36). This is a critical issue because literacy and critical awareness are prerequisites for academic learning, meaningful participation in society, lifelong learning, individual and collective wellbeing, and over-all sustainable development. As Phyak and De Costa (Citation2021) argue, neoliberal ideologies objectify languages as a commodity and colonial mentalities in English-medium education lead to discrimination against indigenous epistemologies and bodies of knowledge. In Dialogue 2, Sarah’s comments aligned with this point when drawing attention to the lack of choice in the UAE in relation to taking degree programs in a language other than English (Hopkyns, Citation2023). For students whose schooling was mainly in their L1, English can act as a gatekeeper and negatively affect ways of learning and academic experiences. To summarize, with a neoliberal and colonial induced focus on the prestige of English, the larger issues of (lack of) choice and agency over medium of instruction have been overlooked by stakeholders and policy makers alike.

6.2. Less ‘talk’ and more ‘walk’ to combat linguistic discrimination and monolingual ideologies

Secondly, a gap between policy ‘talk’ and policy ‘action’ was identified. In the context of Australia, Sender stated that advocacy for diversity tends to be part of corporate rebranding (also see Dobinson & Mercieca, Citation2020). While universities talk in general terms about globally opening up and widening participation, there is little action in this regard concerning EMI policies. This led Sender to state that there is ‘more talk than walk’ when it comes to of supporting linguistic and cultural diversity. Not only lack of action, but also ‘hidden agendas’ (Shohamy, Citation2006) related to ‘appropriate’ language use are often found in EMEMUS. For example, images of Sarah’s UAE university and Sender’s Australian university educationscapes and classrooms demonstrated language purity ideologies such as the use of ‘appropriate academic and professional language’ and ‘English only’ (Dovchin et al., Citation2018). The dominance of English in classrooms, assessments and educationscapes meant a lack of belonging for languages other than English, whether it be students’ L1 or heritage languages (Steele et al., Citation2022), as found in other global EMI contexts such as Japan (Nakagawa & Kouritzin, Citation2021) and Nepal (Phyak, Citation2021). The importance of action over merely paying lip service to diversity and inclusion was also stressed by Phyak (Citation2021) when underlining the importance of activism in English-medium education.

A significant strand across the dialogues related to monolingual ideologies and lack of acceptance for translingual practice, which resulted in translingual discrimination (Dovchin, Citation2022) and precarious conditions for students’ translingual practice in EMI contexts (Dovchin et al., Citation2024; Hopkyns & Sultana, Citation2024). The effects of linguistic hierarchies on campuses include a perception of ‘languagelessness’ and covert racializing discourses leading certain speakers to feel stigmatized and unable to use any language legitimately. In Dialogue 3, suggestions for ways to disrupt policies connected to translingual discrimination were discussed such as applying Southern Theory (De Sousa Santos, Citation2021). Southern Theory turns a critical lens on universalism and the dominance of Western models by identifying alternative knowledge production and overlooked issues (Takayama et al., Citation2016). As part of a broader de-privileging movement, Southern Theory works toward the de-privileging of English (Fang & Dovchin, Citation2022). In the context of Bangladesh, Shaila stressed the importance of increasing learners’ critical awareness and sense of respect for their heritage language and identity. Shaila suggested that this could be achieved by teachers encouraging students to write bilingual stories, conduct interviews in their mother tongue and present it in English in classes (Sultana, Citation2023b). Thus, the language classroom itself would become a site of ‘translingual socialization’ and the activities would create opportunities for developing translingual competences (Canagarajah, Citation2013, p. 184). Academic research and discourses in applied linguistics have also suggested the acceptance, sustenance and nurturing of translingual practices in formal domains for the decolonization and de-eliticization of English (De Costa et al., Citation2020; Hopkyns, Citation2023; Hopkyns & Sultana, Citation2024; Selvi et al., Citation2023; Tankosić et al., Citation2021).

6.3. Addressing the post-colonial legacy of unequal Englishes and ‘native speaker’ bias

Thirdly, the focus on standardized English and ‘native speaker’ models stood in opposition to combating the post-colonial legacy of unequal Englishes and ‘native speaker’ biases. In the context of the UAE, Sarah reflected on the prevalence of Anglophone teachers and teachers who gained their postgraduate degrees from Anglophone countries as well as the use of UK-centric and USA-centric textbooks. Such policies relate to neoliberal and (neo)colonial notions of ‘native speakers’ representing ‘quality’ (Phillipson, Citation1992) and being used as a marketing tool (Hopkyns, Citation2022). In Dialogue 3, suggestions for ways to disrupt current policy distractions included placing more emphasis on the hiring of bilingual Arabic-English faculty, in the case of the UAE, as well as adapting materials to suit the local context. Valuing world Englishes and glocal materials (Selvi et al., Citation2023) is a step in right direction to dismantle the postcolonial legacy of unequal Englishes. For stakeholders to embrace such policy changes, critical awareness about geopolitical inequalities and concerns about race, class, poverty, colonialism, or indigeneity should be brought to the fore. Consequently, southern scholarship could serve to disrupt the intellectual supremacy given to the knowledge developed in the Global North (Hamid et al., Citation2024; Phyak & De Costa, Citation2021; Sultana, 2022). To do this, academics and researchers in the fields of SLA, testing and evaluation, teaching materials, and teaching pedagogy must be encouraged to conduct research concerning translingual practices and bring about changes to their disciplines based on empirical evidence. To conclude, we call for further research discussions on the politics of distraction in EMEMUS globally, with the aim of critically unpacking current policy distractions and achieving greater social and linguistic justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Hopkyns

Sarah Hopkyns is a lecturer at the University of St Andrews, UK. She has previously worked in the UAE, Canada, and Japan. Her research interests include language and identity, language policy, translingual practice, linguistic ethnography, linguistic landscapes, and English–medium instruction (EMI). She has published widely on these areas.

Sender Dovchin

Sender Dovchin is Professor of Applied Linguistics and Senior Principal Research Fellow at the School of Education, Curtin University, Australia. She was identified as the ‘Top Researcher in the Field of Language & Linguistics' in The Australian's 2022 Research Magazine, and one of the Top 250 Researchers in Australia in 2022.

Shaila Sultana

Shaila Sultana is a Professor and the Director of the BRAC Institute of Languages, BRAC University, Bangladesh. She is also a Professor (on leave) at the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. She has been the most cited author in Linguistics and Literature from the University of Dhaka and Bangladesh since 2021, according to the AD Scientific Index.

References

- Anderson, L. (2006). Analytical autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449

- Barker, C. (2005). Cultural studies: Theory and practice. Sage.

- Barnawi, O. (2018). Neoliberalism and English language education policies in the Arabian Gulf. Routledge.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K. A. C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge.

- Costa, F., & Mariotti, C. (2021). Strategies to enhance comprehension in EMI lectures: Examples from the Italian context. In D. Lasagabaster, & A. Doiz (Eds.), Language use in English-medium instruction at university (pp. 80–125). Routledge.

- Dafouz, E., & Smit, U. (2016). Toward a dynamic conceptual framework for English-medium education in multilingual university settings. Applied Linguistics, 37(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu034

- Datta, S. (2020, August 24th). Indian in blood and colour but English in taste. Bol Magazine. https://bolmagazine.wordpress.com/2020/08/24/indian-in-blood-and-colour-but-english-in-taste/

- De Costa, P. I., Park, J. S., & Wee, L. (2020). Why linguistic entrepreneurship? Multilingua, 40(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0037

- De Sousa Santos, S. B. (2021). Postcolonialism, decoloniality, and epistemologies of the south. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Literature.

- Deumert, A., & Makoni, S. (2023). Introduction: From Southern theory to decolonizing sociolinguistics. In A. Deumert, & S. Makoni (Eds.), From Southern theory to decolonizing sociolinguistics (pp. 1–17). Multilingual Matters.

- Dobinson, T., & Mercieca, P. (2020). Seeing things as they are, not just as we are: Investigating linguistic racism on an Australian university campus. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(7), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1724074

- Doiz, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2021). Analysing EMI teachers’ and students’ talk about language and language use. In D. Lasagabaster, & A. Doiz (Eds.), Language use in English-medium instruction at university (pp. 34–55). Routledge.

- Dovchin, S. (2022). Translingual discrimination. Cambridge University Press.

- Dovchin, S., Gong, Q., Dobinson, T., & McAlinden, M. (Eds.). (2023). Linguistic Diversity and Discrimination: Autoethnographies from Women in Academia. Routledge.

- Dovchin, S., Oliver, R., & Li, W. (2024). Translingual practices: Playfulness and precariousness. Cambridge University Press.

- Dovchin, S., Pennycook, A., & Sultana, S. (2018). Language, culture and the periphery. In Popular culture, voice and linguistic diversity: Young adults on-and offline (pp. 1–26). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61955-2_1

- Ellis, C. (1999). Heartfelt autoethnography. Qualitative Health Research, 9(5), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129122153

- Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. altaMira.

- Fang, F., & Dovchin, S. (2022). Reflection and reform of applied linguistics from the Global South: Power and inequality in English users from the Global South. Applied Linguistics Review, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0072

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

- Gabbatt, A. (2017, March 21). No, over there! Our case-by-case guide to the Trump distraction technique. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/mar/21/donald-trump-distraction-technique-media

- Giroux, H. A. (2014). Neoliberalism’s war on higher education. Haymarket Books.

- Glasser, S. B. (2020, May 21). Trump is a superspreader of distraction. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-trumps-washington/trump-is-a-superspreader-of-distraction

- Hamid, O., & Sultana, S. (2024). English as a medium of instruction in Bangladesh. In K. Bolton, W. Both, & B. Li (Eds.), Handbook of English-medium instruction in higher education (pp. 352–364). Routledge.

- Hattie, J. (2015). What doesn’t work in education: The politics of distraction. Pearson.

- Holliday, A. R. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

- Holliday, A. R. (2018). Native-speakerism. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–7). Wiley.

- Hopkyns, S. (2020a). The impact of global English on cultural identities in the United Arab Emirates: Wanted not welcome. Routledge.

- Hopkyns, S. (2020b). Dancing between English and Arabic: Complexities in Emirati cultural identities. In N. Randolph, A. F. Selvi, & B. Yazan (Eds.), The complexity of identity and interaction in language education (pp. 249–265). Multilingual Matters.

- Hopkyns, S. (2022). A global conversation on native-speakerism: Toward promoting diversity in English language teaching. In K. Hemmy, & C. Balasubramanian (Eds.), World Englishes, global classrooms (pp. 17–34). Springer.

- Hopkyns, S. (2023). English-medium instruction in the United Arab Emirates: The importance of choice and agency. In M. Wyatt, & G. E. Gamal (Eds.), English medium instruction on the Arabian Peninsula (pp. 70–85). Routledge.

- Hopkyns, S., & Sultana, S. (2024). The political underbelly of translingual practice in English-medium higher education. In S. Dovchin, R. Oliver, & W. Li (Eds.), Translingual practices: Playfulness and precariousness (pp. 197–218). Cambridge University Press.

- Hopkyns, S., & van den Hoven, M. (Forthcoming). Researching language and communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: A linguistic duo-ethnography (LDE). In J. M. Ryan, V. Visanich, & G. Brändle (Eds.), Transformations in Social Science Research Methods during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Routledge.

- Hornberger, N. H., & Korne, H. D. (2017). Ethnographic monitoring and critical collaborative analysis for social change. In M. Martin-Jones, & D. Martin (Eds.), Researching multilingualism: Critical and ethnographic perspectives (pp. 247–258). Routledge.

- Huang, P., & Karas, M. (2020). Artefacts as “co-participants” in duoethnography. TESOL Canada Journal, 37(3), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v37i3.1344

- Jenkins, J., & Mauranen, A. (2019). Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus. Routledge.

- Jiang, A. L., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Chinese students’ perceptions of English learning affordances and their agency in an English-medium instruction classroom context. Language and Education, 33(4), 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2019.1578789

- Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B. J. (1997). Language planning: From practice to theory. Multilingual Matters.

- Keleş, U. (2022a). Autoethnography as a recent methodology in applied linguistics: A methodological review. The Qualitative Report, 27(2), 448–474. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5131

- Keleş, U. (2022b). Writing a “good” autoethnography in qualitative educational research: A modest proposal. The Qualitative Report, 27(9), 2026–2046. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5662

- Keleş, U., & Yazan, B. (2023). Representation of cultures and communities in a global ELT textbook: A diachronic content analysis. Language Teaching Research, 27(5), 1325–1346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820976922

- Keleş, U., Yazan, B., & Giles, A. (2019). Turkish-English bilingual content in the virtual linguistic landscape of a university in Turkey: Exclusive de facto language policies. International Multilingual Research Journal, 14(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2019.1611341

- Kim, S. H., & Saenkhum, T. (2019). Professional identity (re)construction of L2 writing scholars. L2 Journal, 11(2), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.5070/L211242088

- Kramsch, C. (2019). Between globalization and decolonization: Foreign languages in the crossfire. In D. Macedo (Ed.), Decolonizing foreign language education (pp. 50–72). Routledge.

- Krompák, E., Fernández-Mallat, V., & Meyer, S. (2022). The symbolic value of educationscapes – Expanding the intersection between linguistic landscape and education. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 1–27). Multilingual Matters.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Basic.

- Leibovich, M. (2015, September 1). The politics of distraction. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/06/magazine/the-politics-of-distraction.html

- Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2013). How languages are learned. Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press.

- Lowe, R. J., & Kiczkowiak, M. (2016). Native-speakerism and the complexity of personal experience: A duoethnographic study. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1264171

- Macaro, E. (2018). English medium instruction. Oxford University Press.

- Manan, S. A. (2021). English is like a credit card’: The workings of neoliberal governmentality in English learning in Pakistan. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1931251

- McIntosh, J. (2020). Introduction: The Trump era as a linguistic emergency. In J. McIntosh, & N. Mendoza-Denton (Eds.), Language in the Trump era: Scandals and emergencies (pp. 1–43). Cambridge University Press.

- Mohanty, A. K. (2010). Languages, inequality and marginalization: Implications of the double divide in Indian multilingualism. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2010(205), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2010.042

- Naidoo, R., Shankar, A., & Veer, E. (2011). The consumerist turn in higher education: Policy aspirations and outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(11-12), 1142–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2011.609135

- Nakagawa, S., & Kouritzin, S. (2021). Identities of resignation: Threats to neoliberal linguistic and educational practices. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 20(5), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1957679

- Pennington, R. (2017, July 22). Pre-university year for Emiratis won’t be phased out yet, officials say. The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/education/pre-university-year-for-emiratis-won-t-be-phased-out-yet-officials-say-1.613147

- Peters, M., & Marshall, J. (1996). Individualism and community: Education and social policy in the postmodern condition. Falmer Press.

- Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford University Press.

- Phyak, P. (2021). Subverting the erasure: Decolonial efforts, indigenous language education and language policy in Nepal. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 20(5), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1957682

- Phyak, P., & De Costa, P. I. (2021). Decolonial struggles in indigenous language education in neoliberal times: Identities, ideologies, and activism. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 20(5), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1957683

- Risager, K. (2018). Representations of the world in language textbooks. Multilingual Matters.

- Rose, H. (2021). Students’ language-related challenges of studying through English: What EMI teachers can do. In D. Lasagabaster, & A. Doiz (Eds.), Language use in English-medium instruction at university (pp. 145–166). Routledge.

- Rose, H., McKinley, J., & Briggs Baffoe-Djan, J. (2020). Data collection research methods in applied linguistics. Bloomsbury.

- Rose, H., & Montakantiwong, A. (2018). A tale of two teachers: A duoethnography of the realistic and idealistic successes and failures of teaching English as an international language. RELC Journal, 49(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217746206

- Roshid, M. M., & Sultana, S. (2023). Desire and marketizing English version of education as a commodity in the linguistic market in Bangladesh. The Qualitative Report, 28(3), 906–928.

- Sah, P. K. (2020). English medium instruction in South Asian’s multilingual schools: Unpacking the dynamics of ideological orientations, policy/practices, and democratic questions. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1718591

- Sawyer, R. D., & Norris, J. (2013). Duoethnography. Oxford University Press.

- Selvi, A. F., Galloway, N., & Rose, H. (2023). Teaching English as an international. Cambridge University Press.

- Shepard, C., & Morrison, B. (2021). Challenges of English-medium higher education: The first-year experience in Hong Kong revisited a decade later. In D. Lasagabaster, & A. Doiz (Eds.), Language use in English-medium instruction at university (pp. 167–192). Routledge.

- Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Routledge.

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Steele, C., Dovchin, S., & Oliver, R. (2022). ‘Stop measuring black kids with a white stick’: Translanguaging for classroom assessment. RELC Journal, 53(2), 400–415.

- Sultana, S. (Forthcoming). A fractured dream of the decolonization and deeliticization of English within EMI programs in South Asia. In S. Mirhosseini, & P. De Costa (Eds.), Critical English medium instruction. Cambridge University Press.

- Sultana, S. (2014). English as a medium of instruction in Bangladesh's higher education: Empowering or disadvantaging students? Asian EFL Journal, 16(1), 11–52.

- Sultana, S. (2023a). EMI in the neoliberal private higher education of Bangladesh: Fragmented learning opportunities. In P. Saha, & G. F. Fang (Eds.), English-medium instruction in multilingual universities: Politics, policies, and pedagogies in Asia. Routledge.

- Sultana, S. (2023b). English as a medium of instruction in the multilingual ecology of South Asia: Historical development, shifting paradigms, and transformative practices. In R. A. Giri, A. Padwad, & M. M. N. Kabir (Eds.), English as a medium of instruction in South Asia: Issues in equity and social justice (pp. 31–56). Routledge.

- Sultana, S., Singh, P., & Dovchin, U. (2023). Feminist reflection on academic life trajectories: The constant ‘becoming’. In S. Dovchin, Q. Gong, T. Dobinson, & M. McAlinden (Eds.), Linguistic diversity and discrimination: Autoethnographies from women in academia (pp. 109–125). Routledge Sociolinguistic Studies Series.

- Takayama, K., Heimans, S., Amazan, R., & Maniam, V. (2016). Doing Southern theory: Toward alternative knowledges and knowledge practices in/for education. Post Directions in Education, 5(1), 1–25.

- Tankosić, A., Dryden, S., & Dovchin, S. (2021). The link between linguistic subordination and linguistic inferiority complexes: English as a second language migrants in Australia. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(6), 1782–1798.

- Tupas, R., & Metila, R. (2023). Language, class, and coloniality in medium of instruction projects in the Philippines. In P. K. Sah, & F. Fang (Eds.), Policies, politics, and ideologies of English medium instruction in Asian universities: Unsettling critical edges (pp. 155–166). Routledge.

- Universities Australia. (2023, 28 February). https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/media-item/international-education-adds-29-billion-to-the-economy/#:~:text = Education%20added%20over%20%2429%20billion,adding%20a%20further%20%243.5%20billion

- University of Oxford facts and figures. (2023). https://www.ox.ac.uk/about/facts-and-figures

- University of St Andrews facts and figures. (2023). https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/about/facts/

- Van den Hoven, M., & Hopkyns, S. (2023). From binaries to plurality: Emirati college students’ perspectives on the plurilingual identities of English users and expatriate teachers. In D. Coelho, & T. Steinhagen (Eds.), Plurilingual pedagogy in the Arabian Peninsula: Transforming and empowering students and teachers (pp. 77–94). Routledge.

- Werbińska, D. (2019). English teacher candidates’ constructions of third spaces in a reflection-enhancing duoethnographic project. Polilog Studia Neofilologiczne, 9, 5–20.

- Werbińska, D. (2020). Duothnography in applied linguistics qualitative research. Neofilolog, 54(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.14746/n.2020.54.2.5

- Yazan, B., & Keleş, U. (2022). A snippet of an ongoing narrative: A non-linear, fragmented, and unorthodox autoethnographic conversation. Applied Linguistics Inquiry, 1(1), 7–17. https://ali.birjand.ac.ir/article_2265_07bec49a2ee30fad6480221b33e7c09a.pdf