ABSTRACT

Political song, especially that which fits new words to existing melodies’ semiotic associations, has been used by Americans as an oppositional tool throughout the history of the United States. Activists employed tunes’ “virality” to disseminate political stances and these practices played a key role in the rise of the modern labor movement. This article traces that history, through a succession of contextualized examples linking nineteenth-century political song to contemporary activism.

KEYWORDS:

Until the movement is marked by the joyous, defiant, singing of revolutionary songs, it lacks one of the most distinctive marks of a popular revolutionary movement, it is the dogma of a few, and not the faith of the multitude. –James ConnollyFootnote1

Introduction

Song has been used by Americans as an oppositional tool throughout the colonial and industrial history of the United States. Politically- or economically marginalized audiences employed songs, particularly those setting new words to a familiar melody, as a means for disseminating radical or underclass political stances.Footnote2 And, these practices played a key role in the rise of the modern labor movement in the United States. This article traces that history, linking nineteenth-century political song to contemporary activism.

In the United States, the half-century between 1848 and 1898 has historically been perceived as a period of political, social, technological, and musical change. While various scholars have demonstrated that the franchise was extended in various parts of the United States in several stages prior to the presidency of Andrew Jackson, in the antebellum period political stakeholders perceived change as imminent, expanding, and either empowering or threatening.Footnote3 The upheaval ushered in during the 1820s by the further extension of the franchise, and a new visibility for frontier activism, and resultant shifts in rights and economic opportunities, led to an explosion of political art-making.

Especially ubiquitous, economical, and thus “viral” was the art of the political song: the authoring of new melodies and of contrafacta – that is, new texts to existing melodies. Contrafact technique had been a common practice in North American political song at least since “Brother Ephraim” (in the 1750s), a set of yokel-mocking verses applied to a sixteenth-century Dutch tune, whose import had been the topic of repeated poetical contestations between pro-British and pro-Continental songwriters. Its ownership was only confirmed as “Yankee Doodle” by the Continental victory at Saratoga in 1777, while the tune itself continued to see service in political contexts for the next 100 years.Footnote4

The contrafact text to an existing melody was a portable, adaptable, and resilient political tool, uniquely suited to print culture – in, for example, the medium of the broadside ballad – and also to the heard-remembered-repeated media of oral/aural processes. Particularly, in the case of subaltern and subversive communities, a song – or even the mere playing of its tune – itself becomes a tactic, covert or overt, for the assertion of political identity. In such a process, a melody like “Yankee Doodle” or “Natchez Under the Hill” a/k/a “Turkey in the Straw” acquires layer upon layer of communicative associations when each new set of words is inscribed, as in a wax tablet or palimpsest, upon the recollected connotations of the tune’s prior usages. Yet unlike the palimpsest, melodies in an aural culture become more resonant, more multi-valent as they acquire new layers of semantic association.Footnote5

Politics, and political song, changed during the Jacksonian Era. Following the War of 1812’s second and conclusive victory against the British Empire, capped by General Andrew Jackson’s belated victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, the nation reconceived what it meant to be a citizen. During the western expansion that followed the 1803 Louisiana Purchase (and imposed a horrific toll upon Indigenous peoples), ferocious debates regarding the legality of enslavement in those new territories and new state constitutions roiled public discourse and the songs that animated it.

Frontier populism in the Jacksonian era

Among other, more ephemeral social and symbolic shifts, between 1815 and 1828 and particularly in the West, land, money, and voting power were at stake, and radicals of all stripes and all constituencies saw song as a useful and economical tool for promulgating political stances.

Jackson, an iconic hero of the War of 1812 and the Battle of New Orleans, won the election of 1828 in a campaign that was notable for its mudslinging, slander, and what might legitimately be termed “fake news.”Footnote6 His extensive appointment of political allies and newcomers upended traditional East Coast power structures and brought populism’s suspicion of eastern financial elites into the White House.Footnote7 At the same time, working-class and frontier identities proved a valuable tool for carving out semiotic space, and its cultural expressions became mapped as oppositional, just as frontier hymnody violated the “rational” and “scientific” improved methods of singing promulgated in the East. There had been recurrent tension between establishment proponents of “Regular” singing – that is, sight-reading from composed harmonizations, with consistent tone and intonation – versus sectarian, rural, or frontier congregations who preferred their own improvisations, regional dialects, performance practices, and favorite repertoires.Footnote8 Jackson thus joined a roster of post-Revolutionary archetypal westerner figures, from the frontiersman Daniel Boone (1734–1820) to the archetypal keelboatman Mike Fink (c1770–c. 1823), whose mythic personae defined rebellious frontier populism and often elicited stories and songs.Footnote9

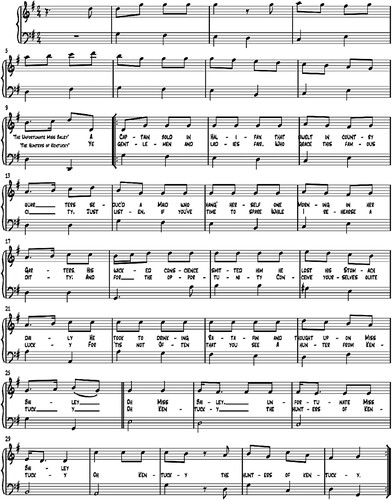

That irruptive, oppositional culture is captured in the 1815 contrafact “The Hunters of Kentucky,” which suggested that frontiersmen were “half horse and half alligator.” Published in 1821 with an attribution to Samuel Woodworth, it was sung to the tune of the ribald “The Unfortunate Miss Bailey.”Footnote10 The melody of that earlier song is traced to a traditional tune called “Ally Croker,” which had appeared in song sheets from the 1730s and was published in Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances vol. 1 (London, 1757). The “Ally Croker” melody was borrowed for a number of London ballad operas – popular theatricals that likewise tended to employ the contrafact technique of authoring new texts to known tunes – while the “Miss Bailey” lyrics, which describe a darkly comic story of seduction, suicide, and haunting, were added in 1803. Under various titles, it appeared as a dance tune in collections from the 1750s onwards, and as a song that also emigrated to Quebec and to America, being recorded in a 1771 music manuscript from the Hudson Valley in upstate New York, the area that gave rise to the Pinkster festival, and thereby to blackface minstrelsy. Hence, before it was ever borrowed for “The Hunters of Kentucky,” the melody that began as “Ally Croker” and continued as “The Unfortunate Miss Bailey” had acquired layers of comic, subversive, and violent association.

The musical setting is in a simple 2/4 time, and follows the common parlor-song format of a simply accompanied tune preceding repeated strophic verses, with a short instrumental introduction to set the key and provide the amateur singer a starting note. The percussive, mostly syllabic (one note per syllable) setting of the sung melody, its repetitious construction using mostly chord tones and stepwise motion, and its relatively narrow range (an octave from D-d, with one added 11th on the high e), all likewise favor the amateur or untrained singer; at the same time, all these factors and the very simplicity of the melodic construction likewise aid easy memorization. The tune is catchy and effortlessly memorable, an important attribute in a song whose political contrafact lyrics are intended to be widely sung, heard, remembered, and repeated.

Also consistent with popular song construction in many eras is the placement, and often times the repetition, of the title phrase at key points in the song; in this case, the keywords “Oh Miss Bailey” / “Oh Kentucky” appear as atypical quarter notes within the 8th-note dominated setting at the opening of the refrain, and recur in the syncopated 3rd measure of that refrain (“un-FOR-tunate Miss Bailey” / “the HUNT-ers of Kentucky”). In the latter song, they are repeated once more for good measure in the closing cadential melodic figure to form the refrain’s last two bars ().Footnote11

Activists among both Jackson’s supporters and his opponents appropriated other songs to serve as melodic vehicles for political statements; it bears repeating that the extensive use of the contrafact technique suggests perceptions of its political potency, even in the case of anonymous authorship For example, “Jackson and the Nullifiers” (1832–1833), sung to the tune of “Yankee Doodle,” marked the President’s unilateral decision to deny states’ capacity to “nullify” federal laws, and the decision’s enforcement by his threat to send US troops into South Carolina.Footnote13Those familiar with the “Yankee Doodle” tune, which itself had been the vehicle for contesting British and Colonial contrafact texts since before the American Revolution, will recognize constructions that exploit the earlier song’s melodic structure; for example, lines 1 and 2, which balance the single-syllable words “why … land is at a stand” with the polysyllabic “ … consternation.” These also set up a cadence to the V or dominant chord, whose open and unresolved nature demands a concluding response with, again, line 3’s monosyllabic words “For in the South they make a rout” answered by line 4’s polysyllabic “Nullification” on the closing cadence to the I or tonic chord.

It bears repeating – so to speak – that the refrain or chorus of a strophic song is the place in which it is most essential to place the most crucial political messaging because it is the section of the form that will receive the most repetition and is most likely to be sung and thus remembered by listeners. Verses can carry content or framing, but the refrain is the most essential element. In this case, “Jackson and the Nullifiers” carries a line 1 catchphrase “[Sing] Yankee doodle doodle doo” which is repeated in line 2 – really just to fill out the requisite number of syllables – while line 3’s single-syllable defiance (“Our foes are few, our hearts are true”) sets up line 4’s political messaging, on the resolving cadence again: “And Jackson is quite handy.”

The influence of antebellum popular song

The impact of blackface minstrelsy upon oppositional song, as both performance idiom and commerce, can hardly be exaggerated. Troupes such as the Virginia Minstrels and Christy’s Minstrels collaborated with and exploited songwriters, and thereby drove sales, while blackface melodies formed a major resource for authors of contrafacts. By the 1850s, especially through the work of Stephen Foster, popular song had also become a commercial powerhouse and a ubiquitous, shared part of the North American musical ear. The expanding market for new compositions, further accelerated by the development of lithographic techniques that brought down the cost of printing music and opulent multi-colored illustrated covers, simultaneously served the at-home musical consumer. New compositional approaches, adaptations, and bowdlerizations of blackface song were additionally mutated by the expanding cult of domestic gentility that had been one middle-class response to turbulent Jacksonian enfranchisement.

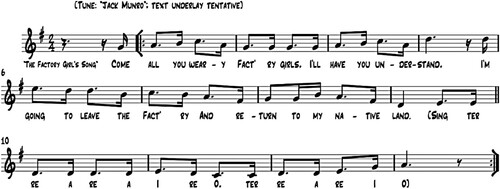

Working-class women also resisted capital’s exploitation of labor, and their experiences were captured as early as the 1830s, in broadsheets like “The Factory Girl’s Song,” which has been tentatively sourced to Canadian mill workers employed in Massachusetts textile mills. It is possibly built upon a tune used for the English song “Jack Munro,” whose earliest printing dates to Newcastle before 1825, about a woman who dresses “in man’s array” to follow her lover to the wars.Footnote15 The cross-dressed defiance of “Jack Munro” is mirrored in “The Factory Girl’s” sardonic defiance, directed to the factory or supervisor, which alternates “Come all ye” callouts to her fellow workers with a tolling, detailed list of all the dehumanizing factory-specific tasks at which she’ll “no more” toil. The narrow range of the melody (within an octave), its wave-like rise and fall, and most especially its A Dorian minor mode, with a refrain probably borrowed from a macaronic Anglo-Irish song, mirrors the sadness and also the anger of the text ().

Political songwriters continued to employ the contrafact technique into the Civil War years, both within and beyond the labor tradition, and found it especially useful in the production of pocket-sized “songsters” carried by – and sometimes sourced from–soldiers on both sides of the conflict. From sublime examples of melodic and rhetorical combination like “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” to the percussive, syllabic tune of “John Brown’s Body,” to the incongruity of “Maryland, My Maryland” sung to the tune of the Rainer Family-imported O Tannenbaum, political song worked when each subsequent appropriation and re-texting of a tune consistently troped and added resonance to the tune’s previous textual associations.Footnote17 Similarly, the Confederacy’s “Bonnie Blue Flag” could be traced back to the 1848 Irish republican song “The Harp without the Crown,” and before that in turn to the bawdy sea chanty “The Girls of Dublin Town.” In each case, the tune’s prior textual associations would link “Bonnie Blue Flag” effectively with those earlier expressions.Footnote18 Contrafact intertextuality typically failed when – as in the case of “Maryland, My Maryland” – the tune was borrowed exclusively for its memorable singability, absent pertinent textual echoes.Blackface song’s links to labor and class

W.T. Lhamon Jr, Eric Lott, William Mahar, and Dale Cockrell, among others, have argued that the Jacksonian phenomenon of blackface minstrelsy, in which young, typically working-class, white performers darkened their faces with burnt cork and performed exaggerated racist caricatures of black folkways, reflected both elements of a polyglot, Afro-Caribbean-based street performance culture, and an implicit – and sometimes overt – mockery of the expanding middle class.Footnote19 Many blackface performers claimed inspiration from the folkways of southern Black culture, but their racist and classist mockery could hardly be considered abolitionist. At the same time, their often scatological, cross-dressing, or otherwise eruptive theatrical performance behaviors also opposed them to the genteel domesticity of hymnody, amateur-oriented piano pieces, and sentimental song. Daniel Decatur Emmett’s 1840s Virginia Minstrels, the first to offer a full evening’s entertainment, catered to an immigrant and/or working-class demographic. The minstrels did not care about temperance, abolition, or women’s rights except as topics for parody, any more than did the mechanics and laborers who made up their theatrical audiences. But their techniques of contrafact, caricature, and topical allusion informed both their working-class listeners’ reception of blackface, and of post-bellum labor’s exploitation of minstrelsy’s own tropes and tunes.

Thus, against the working-class performances, repertoires, and prints of the Virginia Minstrels, and the rowdy frontier actors, singers, dancers, and dockworkers who were their source and audience, might be juxtaposed the appeal to aspiration of the Hutchinson Family Singers, founded in Milford, New Hampshire in 1839, who took their musical cues from imported folkloric groups like the Rainer Family’s “Tyrolese Minstrels,” who toured the United States from the 1820s onward. The Hutchinsons’ appeal was calibrated toward gentility; notably sentiment, patriotism, the celebration of rural (especially New England) life, and gentility’s particular approach to socially progressive issues including abolition, women’s rights, and temperance. “The sound of the Hutchinsons,” as Scott Gac puts it, “was an antiminstrelsy that hushed critics who feared the immorality of entertainment, challenged the European bias of their listeners, and attracted throngs of fans with uplifting reform messages built around familiar tunes.”Footnote20

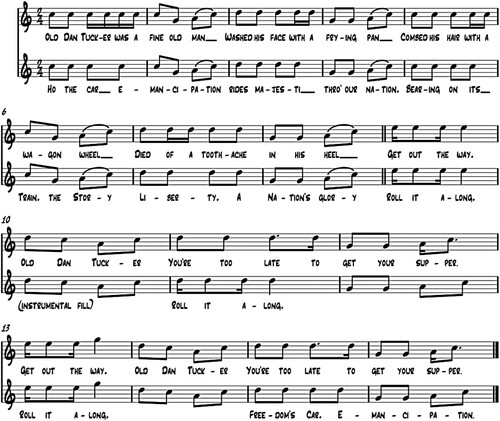

The Hutchinsons’ poetics did not much admit to the challenges to industrial workers, and their idyllic world view barely acknowledged the reality of nineteenth-century immigrant life. Nevertheless, despite their appeal to gentility, the Hutchinsons’ songs on abolition would find them banned at intervals below the Mason-Dixon Line, particularly when they sang Brother Jesse’s notorious contrafact “Get Off the Track” (1844), based on the infectious minstrel tune “Old Dan Tucker.”Footnote21

The subtlety and sophistication of the contrafact technique can be recognized here in both textual and musical terms. Leaving aside the immense popularity of “Old Dan Tucker” itself on the minstrel stage, its insistent and percussive repeated title phrase, and its resultant melodic familiarity for a target audience, the original text’s rambunctious, tall tales-derived metaphor echoes underneath the kinetic energy of Jesse Hutchinson’s new lyrics. Tucker’s tall-tale exploits, his noisy and interruptive billy goat and hound dog, his drunken mishaps and rowdy dancing with “the gal that he loved best,” are quite a distance from Hutchinson’s “majestic Car Emancipation,” “waving of Free Banners,” and shouted “hosannas,” but there is no mistaking the militance of each character’s assault upon an opposing status, whether gentility (for Tucker) or slavery (for the Hutchinsons). The intertextuality continues: the new setting meticulously retains the most distinctive and hooky melodic moment: one can imagine an abolitionist audience roaring out Roll it along! with only a little less fervor than the Bowery Theater “mechanics” audience might shout Get out the way! in chorus ().

In the context of this essay, it is thus most useful to think of the Hutchinsons’ appeal, like that of the Swedish Nightingale Jenny Lind (1820–1887), a soprano whose explosive 1850s media fame was orchestrated by P.T. Barnum, as reflecting a pastorally-infused middle-class gentility that valued progressive justice in the abstract and on the concert stage but was unprepared for the rough-and-tumble of labor songs in the street.Footnote22 We will see this dichotomy recurring in the post-bellum tension between rural populism and urban progressivism, and between working-class union and labor organizing songs versus middle-class evangelism.

Post-bellum labor song

Union and labor advocacy in the post-Civil War period took many forms, with organizers seeking to limit hazards, restrict the use of child workers, and create some modicum of a safety social net. Philadelphia carpenters had struck as early as 1791 for a work day no longer than ten hours, and in 1864 Chicago organizers promulgated an eight-hour work day. An anonymous 1865 contrafact to the tune of “God Save the Queen” / “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” began:

Ye noble sons of toil,

Who ne’er from work recoil.

Take up the lay;

Loud let the anthem’s roar.

Resume from shore to shore,

Till time shall be no more,

Eight hours a day.Footnote23

Productions of radical song, and particularly the use of contrafacts on populist and working-class topics, accelerated in the era between the 1866 Reconstruction Acts, which established military governorships in the former Confederacy, and the withdrawal of federal troops from southern states after 1877. At the same time, an ugly strain of protectionist, racist, and nativist thinking appears in agrarian unions like the Farmers’ Alliance. The Knights of Labor, for example, founded in the 1870s as a secretive alliance of miners, steelworkers, and railroad personnel, and influenced – as had been the first Ku Klux Klan – by the immigrant traditions of rural rebels such as the Rebecca Rioters and Molly Maguires, excluded foreigners from their ranks, along with bankers, lawyers, and land speculators. Similarly, when the completion of the first transcontinental railway lines meant that cheap labor from Chinese workers was no longer an economic necessity, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first major law restricting immigration to the United States, followed, and was enthusiastically supported by the protectionist Knights of Labor.Footnote24

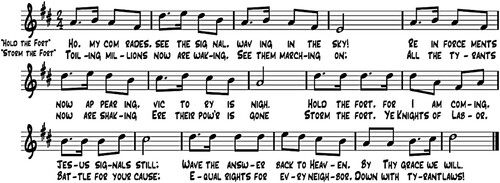

Even so, despite the nativism, racism, and rural skepticism of the Knights, song remained a crucial and artful political weapon for them. Alfred Green’s 1877 “Workman’s Hymn” (a/k/a “Hold the Fort”) was set to the gospel tune “Rock of Ages,” whose original text by the Reverend August Toplady had appeared in The Gospel Magazine in 1775, and which may have been inspired by a sermon quoted in a hymnal collated by Charles Wesley in the 1740s. “Rock of Ages” was thus the recipient of several generations’ worth of gospel connotation. The original melody, which is attributed to Thomas Hastings (1784–1872) and was borrowed by the American Lowell Mason (1792–1872), emphasizes the march-like short phrases of each line, using a simple four-note rhythmic motif whose appearance at various transpositions (on “Ho, my Comrades,” “see the signal,” “waving in the [sky]”) makes it easy to learn and to remember. The refrain, whose chant-like opening of “Hold the fort” begins on the tonic scale degree and is thus readily located by amateur singers, outlines the tonic (D) and subdominant (G) chords, to an unresolved open cadence on “ … Jesus signals still.” This in turn sets up the resumption of the march forward on “Wave the answer / Back to heaven,” and a uniquely modified retrograde version of the rhythmic motive, which rises, on “by Thy grace, we will,” to the closing cadence.

Toplady’s melody would be borrowed again, specifically because of its evangelical associations, for “Storm the Fort, Ye Knights of Labor” (1884) by Philip P. Bliss, which was published in Labor Songs Dedicated to the Knights of Labor ().Footnote25

Toplady’s “Ho, my comrades” becomes “Toiling millions,” and those millions are not just “seeing a signal waving” but are now waking and marching. His sympathetic and optimistic “reinforcements” are countered by “all the tyrants,” and the response to those tyrants’ tottering power is not to “hold” the fort but to storm it. For the gospel reformers, evangelical belief would bring relief in the next world (“Jesus signals still; / Wave the answer back to heaven”); for the populists of the Knights of Labor, it was a this-world battle for a specific political goal: e.g., “down with tyrant laws.”

This counterpoint – between working-class, often immigrant labor organizers and authors on one side, and sentimental song and pious hymnody, often native-born, on the other – was further exacerbated by the frequency with which evangelicals group like the Salvation Army supported capital, and solicited ongoing charitable donations, in capital’s ongoing opposition to labor organizing. By the late 1870s, middle-class gentility was so deeply invested in the status quo that labor songsters mined gospel hymnody, particularly the “Sankey” tunes associated with the 1875 Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs, precisely in order to parody and attack that evangelical impulse.

An additional factor shaping and accelerating the use of contrafact song in post-Civil War labor was the strong influence of immigrant organizers, particularly from Scandinavia and southeastern Europe. Activists had been part of many waves of immigration that followed the 1848 revolutions, many finding it safer to depart Europe altogether in favor of America, and this continued in the social upheavals that followed German unification (c1866–1871), the annexation of Polish-speaking lands, and the pogroms against Jewish shtetls in Ukraine and Russia. Immigrant refugees brought both political skills and radical singing traditions, and these shaped labor discourse.

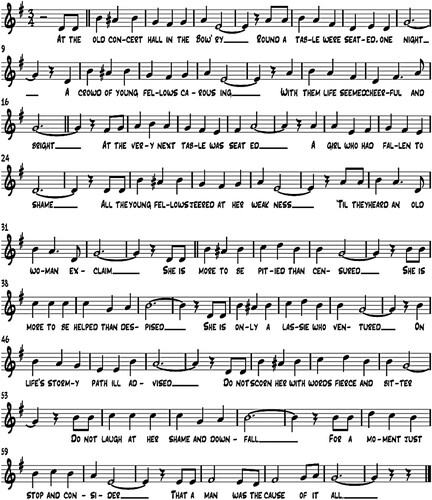

Minoritized women and immigrant activists continued their wars-through-song even later, into the new twentieth century. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, in which 146 garment workers barricaded in a New York piecework factory died from fire or falling, would prove a watershed moment in the history of labor disasters brought about by corporate greed, and in the horrible specifics – burning, still living bodies leaping from tenth-floor windows – that lent themselves to muckraking investigations, editorial excoriation, and the pursuit of labor reform. A song-based judgement came in “Dos lid fun nokh dem fayer” by Charles Simon, who specified that his Yiddish contrafact should be sung to the tune of William B. Gray’s hit “pathetic” song “She is More to be Pitied than Censured” (1898). Though the collision of saccharine tune and original text with the stark horror of the Fire may seem incongruous, there is sophisticated intertextuality here: by emphasizing the youth and innocence of those killed, Simon draws the preventable sadness of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory tragedy in bold relief, and taps into the savage critique of male abusers implicit in Gray’s original closing line “That a man was the cause of it all” ():Footnote26

Capitalists, when unable to entirely shut out organizers, often sought to thwart consolidated action by drawing divisions between workers’ groups: they feared union consolidation across trades and ranks above all else. Recognizing this, some labor song collections themselves explicitly pursued this kind of common cause: the 1887 Anti-Poverty Land and Labor Songs, published by George-McGlinn, is subtitled:

A Choice Collection of One Hundred and Thirty Popular, New and Original Compositions, with Radical Words … all designed for Land and Labor Lectures, Anti-Poverty Societies, George-McGlynn New Cross Crusade Meetings, Knights of Labor Assemblies, Trade Union Associations, and all Orders or Lodes intended to improve the Physical, Moral, Social and Spiritual Condition of Mankind.Footnote28

Labor and imperialism in the gilded age

Between Reconstruction and the turn of the century, the vast expanse of industrial wealth on one side and the significant increase in immigration on the other brought both new class tensions and new labor stances into the songwriting mix. In this Gilded Age, the lines between middle-class “reformers,” who were largely supporters of the status quo and often sought to “uplift” the urban poor via education and evangelism, and labor activists, many of them experienced in or inspired by European socialist and anarchist traditions, were drawn more fiercely, and song deployed more savagely. The post-bellum era saw the rise of mass religious revivals as public and spectacular events, whose sung soundtrack was supplied by gospel songwriters such as Ira D. Sankey (1840–1908), the Civil War songwriter George F. Root (1820–1895), and Fanny Crosby (1820–1915). These songs’ associations with evangelical Christianity and sentimental gentility, their wide distribution, and their singability made them both memorable and popular.

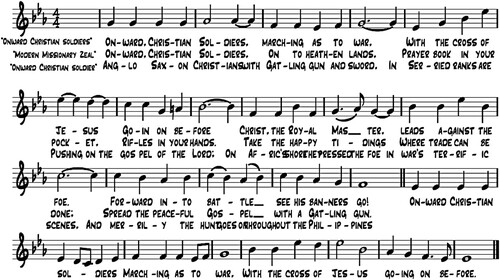

Sabine Baring-Gould’s text “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” published in 1871 to music composed by Arthur Sullivan (of operetta fame), is an exemplar of the type. Its ubiquity and its associations made it a prime target for labor songwriters’ parodic skills. For example, the Journal of the Knights of Labor, reorganized from the earlier Journal of United Labor (1880–1889, Marblehead Massachusetts), published “Modern Missionary Zeal” in 1893 ():

Figure 6. “Onward Christian Soldiers” / “Modern Missionary Zeal” / “Onward Christian Soldier.” Author’s transcription.

Sullivan’s tune sets Baring-Gould’s four-square hymn-style melody in syllabic fashion. Its melodic shape and formal structure are slightly more sophisticated – indeed, to use period locution, “scientific” – in keeping with Sullivan’s more expansive and ambitious compositional skills. The title line is sung at the opening of both verse and refrain, rendering it that much more memorable, but the melody also employs an internal secondary dominant, with the rising A-natural on “going on be-fore” pivoting us momentarily to the dominant key of Bb major, which is tonicized by the F-F-Bb-F (on “Christ, the Royal Master”) in the next measure. And there is further “scientific” sophistication – and text-painting – in the extension of the recurring c-Bb-A-Bb motif on “forward into / battle / See his banners go,” which in turn sets up the chantlike “Onward Christian Soldiers,” this time on the amateur-friendly tonic Eb.

Onward, Christian soldiers! On to heathen lands

Prayer book In your pockets, Rifles in your hands.

Take the happy tidings Where trade can be done;

Spread the peaceful Gospel With a Gatling gun.

Tell the wretched natives Sinful are their hearts.

Turn their heathen temples Into spirit marts.

And If to your preaching They will not succumb,

Substitute for sermons Adulterated rum.

…

If, spite all your teaching. Trouble still they give;

If, spite rum and measles. Some of them still live;

Then with purpose moral, Spread false tales about,

Instigate a quarrel And let them fight it out.Footnote29

1891s Alliance and Labor Songster illustrates the awareness on the part of activists that there was vast, if untapped and not yet organized, power in cross-trade and rural-urban alliances.Footnote30 Farmers might have different priorities than industrial workers and skilled craftspeople might wish to separate their goals from those of unskilled laborers, but the wisest organizers recognized that more concerted action, crossing boundaries and finding common cause, represented the greatest aggregate power – and it was for precisely this reason that capital sought to stifle the chance for the “One Big Union” (of “all workers”) about which the Industrial Workers of the World would preach in the next decade. For example, Number One in the Songster’s first section is an “Opening Song,” to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne.” Its chorus reads:

For Justice is our cornerstone,

And Truth our sword and shield:

Fraternity our battle-cry

The world our battlefield.

One more we meet to clasp / In friendships hallowed grasp / The hands of men! …

Our country, great and grand, / Is known in every land / As Freedom’s home …

Our cause, it is of Thee! / Sweet Cause of Liberty / Of Thee we sing …

Most radical of all is Thomas Nicol’s contrafact, whose ferocity deserves more extensive replication:

My country, ‘tis of thee, / Once land of liberty, / Of thee I sing

Land of the Millionaire; / Farmers with pockets bare; / Caused by the cursed snare– / The Money Ring

My native country, thee, / Thou wert so pure and free, / Long, long ago.

Yet still I love they rills, / But hate thy usury mills, / That fill the bankers’ tills / Till they overflow.

So when my country, thee, / Which should be noble, free, / I’ll love thee still;

I’ll love thy Greenback men / Who strive with tongue and pen, / For liberty again, / With right good will.

And then my country, thee, / Thou wilt again be free; / And Freedom’s tower.

Stand by your fireside then, / And show that you are men, / Who they can’t fool again, / And crush their power.

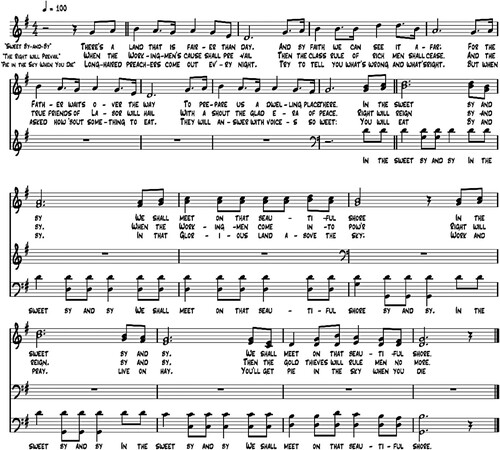

Figure 7. “Sweet By-and-By” / “The Right will Prevail” / “Pie in the Sky When You Die.” Author’s transcription.

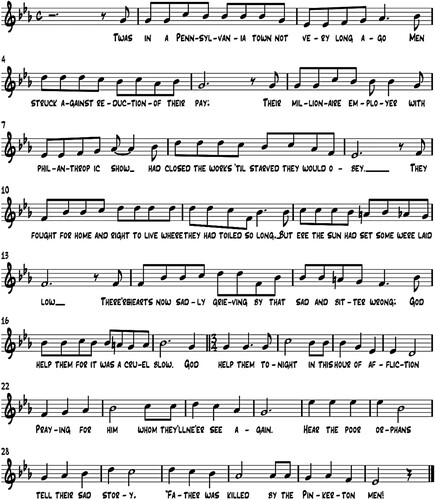

Gilded Age labor songs’ more radically confrontational imagery and language echo the radical, even extra-legal rhetoric of the period. For example, the role of the hated “company gun thugs,” most notoriously Allan Pinkerton’s detectives who quelled the 1892 Homestead Strike, is commemorated in “Father Was Killed by the Pinkerton Men,” which was published in Chicago by William W. Delaney, to a tune called “Weep Some More My Lady” by Sigmund Spaeth ().Footnote31

Delaney’s song represents a particularly striking juxtaposition of the appropriation of the text language associated with a sentimental song, contrasted to the starkness of the event delineated, and is included here partly because of this notable atypicality. Though the melody is unidentified, its form is striking for two reasons; first, because its shape, range, and internal organization suggest a more skillful singer and exploit the implied “scientific” secondary document (on “They fought for home and right to live”) that we have previously seen from Arthur Sullivan, and second, because of the unusual shift from 4/4 time in the verse to 3/4 in the refrain. This sort of metric shift was not uncommon in some more “elevated” types of commercial parlor song, but it is rare to find in a song borrowed for or addressing labor topics, as it does not lend itself so readily to unison singing or learning by ear. That refrain may reflect the vast expansion of Tin Pan Alley songs composed in 3/4 time in this decade, whose popularity and secular topics, and the physical intimacy of the dance associated with it, led to references to “the lascivious waltz.”Footnote32

Populism reached a kind of apotheosis with the 1892 convention of the People’s Party, more commonly known as the Populists, which was held in Omaha in July; there, central planks of the platform were a guaranteed federal loans system, a national program for crop storage, and the elimination of private banks, three core tenets which reveal the Party’s agrarian bias. See, for example, “The Workingman’s Hymn,” to the tune of “Sweet Bye-and-Bye,” above, and “Looking Backward,” to the tune of “Shall We Gather at the River?”Footnote33Looking backward o’er the record the Republicans have made,

Can we still support their party with these before us laid?

First, they ‘except’ on greenbacks, causing gold to take a rise;

But T. Stevens saw the danger – tears went streaming in his eyes.

Chorus:

We will vote for the labor party,

A good and reliable party.

Vote to support the laboring party,

That gives justice to all.

Then they passed the national bank act, giving wealthy men the chance

To loan you money congress should do, and charge you high interest in advance.

Next, they contracted our money, and passed on act in ‘66,

Which burned up the national greenbacks on which the people paid no tax …

The Battle Hymn of Labor

[to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”]

Ye have offered bribes and share of spoils to rulers of our land;

Ye have subsidized our teachers and sown lies on every hand.

But the suf’ring people rising now, come forth at God’s command,

For God still marches on.Footnote34

By the end of the decade, civil and labor rights were in full retreat in the face of capital’s muscle and the federal government’s complicity. The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, in which African-American Homer Plessy intentionally violated Louisiana’s segregation laws by boarding and refusing to leave a whites-only train car, was the basis for the Supreme Court’s ruling that “separate but equal” facilities for whites and Blacks did not violate the U.S. Constitution – and it paved the way for sixty years of discrimination in the workplace, in social life, and especially in public education. In the same year, Filipino nationalists led by Emilio Aguinaldo embarked on a revolutionary uprising against Spanish rule in those islands, which brought Aguinaldo’s nationalists into an alliance with the U.S. government after the (probably staged) sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor in April 1898.

The “muscular Christianity” of “Onward Christian Soldiers” would return in a December 1899 publication from the American Anti-Imperialist League in response to the American annexation of the Philippines.Footnote35 Authored by William Lloyd Garrison Jr, the son of the famed abolitionist, its text references both the Filipino resistance and analogous British culpability in their treatment of Boer detainees in South Africa in the same year.

“Onward Christian Soldier”

--William Lloyd Garrison Junior

The Anglo-Saxon Christians, with gatling gun and sword,

In serried ranks are pushing on the gospel of the Lord;

On Afric’s shore they pressed the foe in war’s terrific scenes,

And merrily the hunt goes on throughout the Philippines.

What though the Boers are Christians: the Filipinos, too!

It is a Christian act to shoot a fellow creature through;

The bombs with dynamite surcharged their deadly missiles fling,

And gaily on their fatal work the dum-dum bullets saying.

The dead and mangled bodies, the wounded and the sick,

Are multiplied on every hand, on every field are thick

“Oh gracious Lord,” the prayer goes up, “to us give victory swift!

The chaplains on opposing sides the same petition lift … ”Footnote36

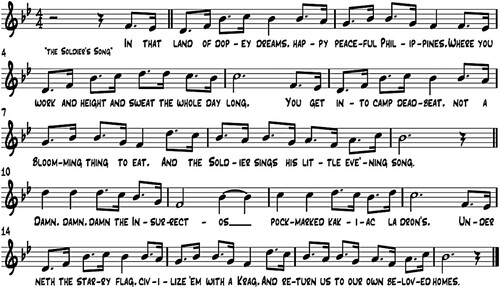

In that land of dopey dreams, happy, peaceful Philippines,

Where you work and height and sweat the whole day long,

You get into camp deadbeat, not a blooming thing to eat,

And the Soldier sings his little evening song.

Chorus:

Damn, damn, damn the Insurrectos, pock-marked kakiac ladron’s,

Underneath the starry flag, civilize ‘em with a Krag,

And return us to our own beloved homes.

…

Underneath the nipa thatch, where the lousy lepers scratch

Only refuge after hiking all day long;

When I lay me down to sleep, slimy lizards o’er me creep,

Then you hear the soldiers sing this evening song.

Fellow workers. … This is the Continental Congress of the working-class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working-class from the slave bondage of capitalism. … The aims and objects of this organization shall be to put the working-class in possession of the economic power, the means of life, in control of the machinery of production and distribution, without regard to the capitalist masters.Footnote37

It is the first strike I ever saw that sang. I shall not forget the curious lift, the strange sudden fire of the mingled nationalities at the strike meetings when they broke into the universal language of song. And not only at the meetings did they sing, but in the soup houses and in the streets … They have a whole book of songs [the legendary “Little Red Songbook,” or more formally Songs to Fan the Flames of Revolution, a collection of contrafact texts which went through many editions] fitted to familiar tunes – ’The Eight Hour Song,’ ‘The Banner of Labor,’ ‘Workers, Shall the Masters Rule Us?’ But the favorite of all was the ‘Internationale.’Footnote38

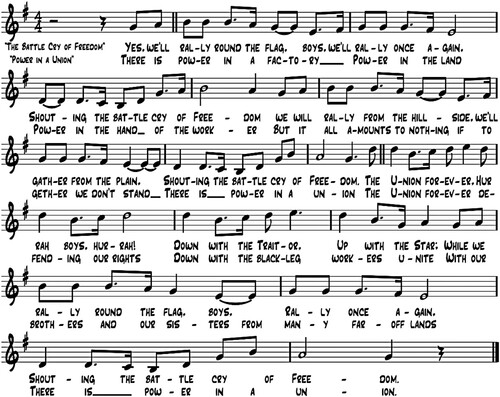

Song was and is power, especially for those to whom power is otherwise denied because it is portable, mutable, memorable, economical, accessible, and difficult to contain. That power rings again, as recently as the wave of union formation and organizing that followed the “Great Resignation” of the COVID-19 crisis.Footnote39 At a Starbucks in Buffalo, New York for example, on October 12th, 2022, English folk/punk singer Billy Bragg sang his own version of “There is Power in a Union,” a title authored by immigrant Wobbly Joe Hill the tune of George F. Root’s “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” prior to Hill’s execution by firing squad, on falsified charges of murder, in November 1915. In the classic contrafact tradition, Bragg’s new twenty-first-century lyrics update the tune’s 175-year history of layered radical connotation ():Footnote40

There's power in a factory, power in the land

Power in the hand of the worker

But it all amounts to nothing if together we don't stand

There is power in a union

Now the lessons of the past were all learned with workers’ blood

Mistakes of the bosses we must pay for

From the cities and the farmlands to trenches full of mud

War has always been the bosses’ way, sir

[Chorus]

The union forever defending our rights

Down with the blackleg, the workers unite

With our brothers and our sisters from many far-off lands

There is power in a union

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christopher J. Smith

Christopher J. Smith is Professor and Chair of Musicology, and director of the Vernacular Music Center (www.vernacularmusiccenter.org) at the Texas Tech University School of Music. In addition to an active career as performer, conductor, and arranger, he has also authored The Creolization of American Culture: William Sidney Mount and the Roots of Blackface Minstrelsy (Illinois, 2013) and Dancing Revolution: Bodies, Space, and Sound in American Cultural History (Illinois, 2019); his next monograph is Situational Genius: The Practice of the American Bandleaders (Illinois, forthcoming).

Notes

1 Connolly, Selected Writings, 48.

2 For the purposes of this essay, I take “radical” as a stance regarding group action that disobeys existing laws and statutes. Both “conservative” and “progressive” positions may yield such action; “radical,” in my usage, therefore connotes a rhetoric that expresses willingness to violate existing laws and statutes. So, for example, both the paramilitary “Sons of Liberty” (c. 1765–1784) in the American Revolution, conventionally understood as “progressive” and literally revolutionary, may be described as “radical,” but so also may be the paramilitary First Ku Klux Klan (c. 1865–1871), conventionally mapped as “conservative.” In both cases, each group’s rhetoric expressed willingness to operate outside the rule of law, and thus qualifies as “radical,” under my definition. As regards “underclass,” I take methodological and critical frameworks from the historians E.P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Peter Linebaugh, and Marcus Rediker.

3 See, for example, Ratcliffe “The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828”; Gronningsater, “Expressly Recognized.” On the perception of imminent change during this period see, among others, Conlin, “The Dangerous Isms. I am indebted to Billy Coleman for these citations.

4 See, for example, Alexander, “Yankee Doodle Rides into Town,” in To Stretch Our Ears; Goodman, “Transatlantic Contrafacta,” 392–419.

5 Disclaimer: Parallel to these usages is the very rich and complex tradition of slavery-era Black song, especially the early spirituals and work songs that sometimes encoded resistance. Though a comprehensive analysis of this latter repertoire is beyond the scope of the current article, it must be acknowledged that the tradition of Black sung resistance, including spirituals, hollers, gospel songs, Civil Rights songs, and so forth, is rich and complex.?

6 Jackson’s parentage, marriage, slaveholder status, harshness as a military commander and governor, and actions in various campaigns against Native Americans were all the targets of pamphlet attacks. See, among others, Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics,” 890–918; Watson, Liberty and Power, chapter 3.

7 Most tangibly, by dissolving the Second Bank of the United States in 1832.

8 Church fathers had long inveighed against this kind of defiant musical apostasy. See Ford (ed.), Diary of Cotton Mather, 2:693.

9 On Jackson as an archetype, the foundational text is Ward, Andrew Jackson.

10 Sung in New Orleans in 1833 by Noah M. Ludlow; “The Unfortunate Miss Bailey.”

11 As Steven Tyler of the American rock band Aersomith once said, “If you want to write a hit single, start by repeating the title.”

12 The hunters of Kentucky. Online Text. https://www.loc.gov/item/amss.sb20165a/. Accessed 1.8.2024.

13 Jackson and the nullifiers. Library of Congress, https://goo.gl/xVTerL Accessed 1.8.2024.

14 “Jackson and the nullifiers” (1833). https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:277529/.

15 “Jack Munro.” Roud 268; Bodleian 9061. http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/roud/268. See also https://studylib.net/doc/8199023/lowell-factory-girl---fund-for-labor-culture-and-history Accessed 2.15.2023.

16 Anonymous broadside tentatively dated 1830s, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1445159 Stecher & Brislin, “Jack Monroe.”

17 See, for example, Davis, Maryland, My Maryland.

18 On the difficulty of legally parsing the multiple meanings of songs like “Maryland, My Maryland” and “Bonnie Blue Flag” during the American Civil War see Coleman, “Confederate Music,” 95–7.

19 See, for example, Lhamon, Raising Cain; Lott. Love & Theft; Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask; Cockrell, Demons of Disorder; Smith, Creolization.

20 Gac, Singing for Freedom. See also Runzo, Theatricals of Day, and Roberts, Blackface Nation.

21 Though beyond the scope of this article, the association of the locomotive with technological advance, modernization, internal immigration, and the industrial/urban north meant that trains continued to be a central metaphor in, particularly, southern Black folklore and song.

22 See, for example, Stroman, “The Etude Magazine,” 21ff.

23 Quoted in Crawford, An Introduction to America's Music, 224.

24 As Yingze Huo has pointed out, working-class and nativist resentment of Chinese guest workers plays out in a significant body of contrafacts based upon borrowed minstrel tunes. See Huo, “Strange Affinities,” 50–2.

25 N.a., Labor Songs.

26 http://www.yiddishpennysongs.com/2015/05/dos-lid-fun-nokh-dem-fayer-fun-di.html Accessed 2.15.2023.

27 Peppler, Yiddish Songs. Thanks to Jane Peppler for her musical detective work in collecting and publishing these songs.

28 Cited and reproduced in Crawford, 450.

29 Quoted in Foner, 152.

30 The Alliance And Labor Songster. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735061820746/viewer#page/6/mode/2up

31 1892 Homestead Strike (https://aflcio.org/about/history/labor-history-events/1892-homestead-strike) Accessed February15, 2023. See Pilon, The Monopolists. I am indebted to Billy Coleman for this citation.

32 See for example: “At the trial the court brought out the fact that Pennell and Burdick's wife found their heaven in the lascivious Waltz at their Buffalo dancing club. The faithless woman on the witness-stand was compelled to make profession of criminal degradation. She admitted that Pennell's love-letter stated the fact, that he found ‘paradise within her arms‘.” Quoted in Everitt and Francis, Immorality of Modern Dances.

33 The Alliance and Labor Songster, 29. https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/209603/page/13 Accessed January 31, 2023.

34 Quoted in Luectefeld, “Petitioning in Boots,” 179.

35 “Muscular Christianity” as a moral aesthetic emerged in Victorian-era England and is particularly associated with the 1857 schoolboy novel Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hughes (1822–96) in the UK and with Theodore Roosevelt in the USA. It was particularly attractive to Anglo-Saxon Protestant activists who were suspicious of foreign creeds and immigrant identities.

36 James, “Cotton, Rum, and Reason,” 44–5.

37 Haywood, Autobiography, 181.

38 Baker, The American Magazine, quoted in Brenner, Day, and Ness, The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History, 109.

39 Lindsey Jacobson. Robert B. Reich, who served as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton Administration, likened it to a “general strike.” “The ‘Great Resignation’ is a reaction to ‘brutal’ U.S. capitalism: Robert Reich.”

40 Bragg. “There is a Power in a Union.”

Bibliography

- 1892 Homestead Strike. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://aflcio.org/about/history/labor-history-events/1892-homestead-strike.

- Alexander, J. Heywood., ed. “Yankee Doodle Rides into Town.” In To Stretch Our Ears: A Documentary History of America’s Music, 49–52. New York: Norton, 2002.

- Alliance and Labor Songster: A Collection of Labor and Comic Songs, for the use of Alliances, Grange Debating Clubs and Political Gatherings. Alliance Songster. Songs for the toiler. Winfield, KS: H&L Vincent.

- “Anonymous Broadside Tentatively Dated 1830s.” Accessed January 7, 2024. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1445159.

- Basch, Norma. “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the Election of 1828.” Journal of American History 80, no. 3 (1993): 890–918. doi:10.2307/2080408.

- Bragg, Billy. “There is a Power in a Union. YouTube Video. October 12, 2022. https://youtu.be/JgPP1hG4CUY.

- Brenner, Aaron, Benjamin Day, and Immanuel Ness, The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Cockrell, Dale. Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and their World. Cambridge: Cambridge, 1997.

- Coleman, Billy. “Confederate Music and the Politics of Treason and Disloyalty in the American Civil War.” Journal of Southern History 86, no. 1 (2020): 75–116. doi:10.1353/soh.2020.0002.

- Conlin, Michael F. “The Dangerous Isms and the Fanatical Ists: Antebellum Conservatives in the South and the North Confront the Modernity Conspiracy.” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 2 (2014): 205–233. doi:10.1353/cwe.2014.0045.

- Connolly, James. James Connolly: Selected Writings. London: Pluto Press, 1988.

- Crawford, Richard. An Introduction to America's Music, 224.

- Davis, James A. Maryland, My Maryland: Music and Patriotism in the American Civil War. Lincoln. NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

- Edwards, Owen Dudley, and Bernard Ransom. eds., James Connolly: Selected Political Writings. New York: Grove Press, 1971.

- Gac, Scott. Singing for Freedom: The Hutchinson Family Singers and the Nineteenth-Century Culture of Reform. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Goodman, Glenda. “Transatlantic Contrafacta, Musical Formats, and the Creation of Political Culture in Revolutionary America.” Journal of the Society for American Music 11, no. 4 (2017): 392–419. doi:10.1017/S1752196317000359.

- Gronningsater, Sarah L. H. “Expressly Recognized by our Election Laws.” W&MQ, 2018.

- Haywood, William. The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929.

- Huo, Yingze. “Strange Affinities: The Figure of Chineseness in Black-Themed Cultural Productions, 1850–1930”. PhD diss., Musicology, Texas Tech 2021, 50–52.

- Jack Munro. Roud 268; Bodleian 9061. Printed at Durham by T. Hoggett between 1816–43. Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Library. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/roud/268.

- Jackson and the nullifiers. Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, at 257 Hudson-street, and 138 Division-street. 1832. 1832. Library of Congress, https://goo.gl/xVTerL.

- Jackson and the nullifiers. Harris Broadsides. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:277529/, 1833.

- James, Joshua Nicholas. “Cotton, Rum, and Reason: Anti-Imperialist Poetry from 19th Century U.S. Newspapers and Post-Colonial Discourse.” Master's thesis, East Carolina University.

- Labor Songs Dedicated to the Knights of Labor. Chicago: J.D. Tallmadge, 1886.

- Lhamon, W. T. Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop. Cambridge: Harvard, 2000.

- Lott, Eric. Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Cambridge: Oxford, 2013.

- Luectefeld, Sean. “Petitioning in Boots: Motivation & Mobilization in the Rhetoric of Coxey’s Army, 1894”. PhD diss., University of Maryland College Park, 2017, 179.

- Mahar, William J. Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. Champaign: Illinois, 1999.

- Mather, Cotton. Diary of Cotton Mather. Edited by Dr. W.C. Ford. Boston: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1911–1912, 2:693.

- N.a. Immorality of Modern Dances [Everitt and Francis Co. etc., New York, monographic, 1904]. Pdf. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/item/04014356/.

- N.a. The Alliance and Labor Songster. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/209603/page/13.

- Peppler, Jane. Yiddish Songs of the Gaslight Era: A Sampling of Sheet Music for Broadsides Sold by Peddlers on the Lower East Side. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. http://www.yiddishpennysongs.com/2015/05/dos-lid-fun-nokh-dem-fayer-fun-di.html.

- Pilon, Mary. The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015.

- Ratcliffe, Donald. “The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828,” JER.

- Reich, Robert. “The ‘Great Resignation’ is a reaction to ‘brutal’ U.S. capitalism: Robert Reich.” CSNBC February 4 2022. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/04/robert-reich-great-resignation-general-strike-health-care-childcare.html.

- Roberts, Brian. Blackface Nation: Race, Reform, and Identify in American Popular Music, 1812–1925. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- Runzo, Sandra. Theatricals of Day: Emily Dickinson and Nineteenth-Century American Popular Culture. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019.

- Smith, Christopher J. The Creolization of American Culture: William Sidney Mount and the Roots of Blackface Minstrelsy. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

- Stecher & Brislin. “Jack Monroe.” YouTube video. 03.14.2019. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://youtu.be/KTz0lbmhXt0.

- Stroman, Elissa. “The Etude Magazine and The Archetyping of American Musical Women, 1886–1926,”. Master’s Thesis, Texas Tech University, 2010, 21ff.

- The Hunters of Kentucky. Andrews, Printer, 38 Chatham Street, N. Y. Monographic. Online Text. https://www.loc.gov/item/amss.sb20165a/.

- Ward, John William. Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age. New York: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Watson, Harry. Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America. New York: Hill & Wang, 1990.

- Watson, Harry L. Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.