Abstract

Children who have partial hearing (PH) in the low frequencies and profound sensorineural hearing loss in the high frequencies can present a challenge to cochlear implant (CI) teams in terms of referral, assessment, and candidacy. Neither clinical criteria nor optimal timing for implantation has been explored in the literature. Data from both the Hearing Implant Centres of Birmingham Children's Hospital and St Thomas’ Hospital indicate that it is clinically appropriate to implant children with PH; they perform better with CIs than with hearing aids, even if their hearing is not fully preserved. We have also found that children need early access to high frequency sound in order to reach their full potential.

Introduction

Improvements in both hearing preservation surgical techniques and atraumatic electrode design have allowed children with partial hearing (PH) to be considered for cochlear implantation. In the UK, such children are likely to have profound high frequency hearing loss within current National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) audiometric guidance, and much better hearing in the low frequencies. Pre-referral, these children are often reported to be ‘doing well’ with their hearing aids. However, audiological, speech and language testing, and academic progress may indicate otherwise.

A literature review yielded very few cochlear implant (CI) studies on children with PH, and none on very young children with PH. Published studies also primarily focus on preservation of hearing (CitationSkarzynski et al., 2010; CitationBrown et al., 2010) rather than functional outcomes. There is emerging evidence that CIs provide better results compared with hearing aids in children with PH (CitationGratacap et al., 2015). These researchers also find that older children (>10 years) receiving CI do not show as much improvement as those implanted younger. Despite this, there is a reluctance to offer a CI to young children with PH, and even surgeons who are experienced in atraumatic surgical techniques for hearing preservation are cautious about simultaneous bilateral CI (Panel discussion XIV Hearing and Structure Preservation Workshop 2015).

Despite early intervention being an established principle of cochlear implantation for congenitally severe-profound deaf children, this principle is not always applied to children with congenital PH. Ascertaining ‘sufficient’ benefit from hearing aids can make early referral, assessment and counselling more challenging in this client group. In the meantime, these children do not have proper access to high frequency sounds due to limited hearing aid technology. Inadequate high frequency amplification results in sounds that lack the quality and clarity that are important for word discrimination and understanding speech in noise. This, in turn, may irreversibly affect the child's speech intelligibility and quality without early CI intervention.

Some CI centres want more evidence to implant young children with PH, but there is a lack of evidence due to this reluctance to implant. Emerging data from our two centres indicate that it is clinically appropriate to implant young children with PH; they perform better with CIs than with hearing aids, even if their hearing is not fully preserved.

Methods

A retrospective review was carried out of 28 children (35 ears) with low frequency PH, who were implanted at Birmingham Children's and St Thomas’ Hearing Implant Centres between 2008 and 2015. The age range was 13 months to 12 years, with a mean age of 6.0 years. PH was considered to be <65 dB HL at one or more frequencies between 250 and 1000 Hz. All children had hearing thresholds of >90 dB HL at 2 and 4 kHz.

Nine children were traditional electro-acoustic stimulation (EAS) candidates, according to the recommended EAS fitting range prescribed by the manufacturer. A further two children whose low frequency hearing was poorer than the recommended range, tried EAS and preferred it. The remaining 17 children all received fully electrical stimulation, however a number of the children in this third group received their CIs before the availability of the current range of processors with adaptable EAS programming capability. It is possible that more children in this third group could benefit from EAS technology.

Results

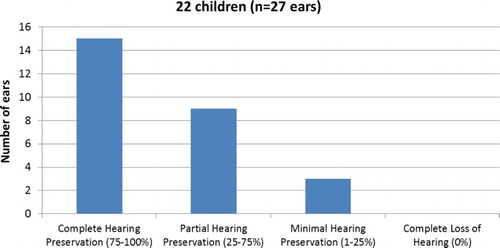

Twenty-three children received unilateral CIs, five children received simultaneous bilateral implants, and two children had staged bilateral surgery. Devices produced by Cochlear, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics were used, and more recently the devices offering EAS technology have been favoured (Cochlear CI422/CI522 and MED-EL Flex implants). Twenty-two children (27 ears) had post-operative audiograms by 6 months’ post-surgery, and the hearing preservation outcomes shown in Fig. were calculated using the method recommended by CitationSkarzynski et al. (2013).

Figure 1 Hearing preservation outcomes calculated using the method recommended by CitationSkarzynski et al. (2013). Fifty-six percentage of ears had complete preservation of hearing, 33% had partial preservation, 11% had minimal perseveration, and 0% had complete loss of hearing

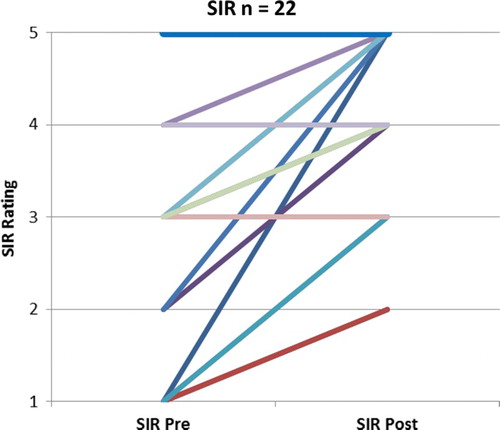

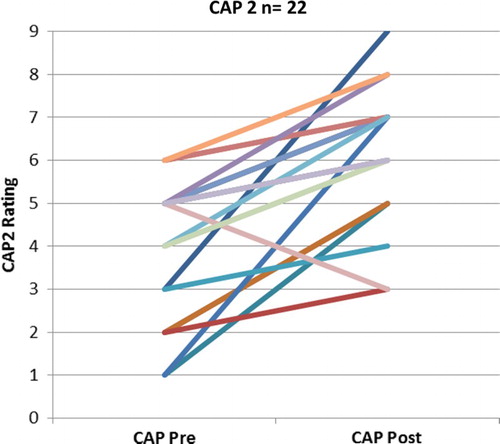

All children were rated pre and post-implant using the Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP 2) and Speech Intelligibility Rating (SIR) scales (Figs. and ). Six children were not included: five children with less than 6 months’ implant use, and one non-user who was lost to follow up.

Figure 2 CAP2 scores pre versus post-implant. The post-implant scores are the most recent rating taken and ranges from 6 months to 7 years post-implant. A low score represents poorer performance. Category 1, the lowest pre-implant score in our cohort, means that the child is aware of environmental sounds only. Category 9, the highest possible score, means that the child is able to use the telephone with an unknown speaker in an unpredictable context

Figure 3 SIR scores pre versus post-implant. The post-implant scores are the most recent rating taken and ranges from 6 months to 7 years post-implant. A low score represents poorer performance. Category 1 means the child has no intelligible speech or recognizable words, but they may be capable of verbalization. Category 5 means the child's connected speech is intelligible with little or no concentration on the part of the listener. The child is understood easily in interaction with an adult

The post-implant scores for both CAP2 and SIR show an upward trend over time (from 6 months through to 7 years CI use). All CAP2 scores improved with the exception of one older child whose post-implant rating was taken after a period of non-use. All SIR scores remained stable or improved post-implant. It should be noted that three of the four cases where the SIR remained stable were already at level 5. Limited or no improvements in speech intelligibility were observed with older children.

Discussion

A literature review yielded very few CI studies on children with PH, and none on very young children with PH. This current paper has the youngest mean age of children with PH in the literature. Whilst current literature mainly focuses on rates of hearing preservation in children with PH, all children in our group perform better with their CI than with their hearing aids, regardless of the level of their hearing preservation. Not only do children with PH benefit from implantation, but in the same way that early implantation for ‘traditional’ CI candidates yield better outcomes, children with PH benefit from early implantation. The only study in the literature which looked at ages of implantation in children with PH (CitationGratacap et al., 2015) came to the same conclusion as we did, that is, young children with PH make better improvements post-implantation than older children. Indeed, we found that limited or no improvements in speech intelligibility are observed with older children. Unfortunately, late referrals, prolonged assessments, and indecision about cochlear implantation can often lead to delayed implantation of children with PH. CI centres may face many challenges and barriers before timely implantation can occur.

Referrer-based challenges

Referrers can be unaware of changing indications for CI, and may still think that any PH will be irreversibly damaged. Expectations for children may be too low; children may be reported as ‘doing well’ with hearing aids because they are compared to other severe-to-profound hearing impaired children, but they may not be reaching their true potential. Children should not be left to ‘fail’ before they are referred because the referral may then be too late to positively impact language acquisition and speech clarity.

Parent/carer-based challenges

Due to the lack of knowledge on hearing preservation techniques, the focus is more on what a child has to lose, rather than on what child has to gain. Parents may also underestimate the child's hearing difficulties because they respond to sound and are developing spoken language. The implication of high frequency loss on language acquisition, academic success and speech clarity may not be fully understood. The use of frequency transposition aids will show good detection, but the more important discrimination resolution will be compromised. Unless audiology departments routinely administer speech recognition testing, this may be missed. As the child progresses through school, language becomes more abstract. Any delay and gaps in language will only make these abstract ideas more difficult for children to understand. Parents might not see the gaps in speech and language until educational attainment or peer interaction becomes an issue.

CI team-based challenges

The confidence to determine whether children would benefit from CI when they are already ‘doing well’ with hearing aids can be difficult. To begin with, children with PH must be given a full assessment by an experienced multidisciplinary team. The Hearing Implant Centres at St Thomas’ Hospital and Birmingham Children's Hospital find that with this group of children, it is important to determine how each child is functioning in their best aided condition in noise, and with each ear individually in quiet. It is important to monitor progress over a specified period of time, and to determine whether the predicted amount of progress is being made. It could be helpful to determine a child's non-verbal cognition, and see if it is commensurate with their speech and language development. Engaging with local teams and education also provides valuable insight into a child's social, emotional and educational achievement.

Once a decision has been made to implant, then the team must decide what is clinically most appropriate: bimodal stimulation (unilateral CI), simultaneous bilateral implantation, or staged bilateral surgery. If the decision is unilateral, then implanting the poorer functioning ear and leaving the better ear for hearing aid amplification is contrary to traditional practice.

The length of electrode array also needs to be considered. In our centres, full insertion is the primary objective; the option of full electrical stimulation is essential for the child's future hearing needs. A Cone Beam scan could be considered to measure length of the cochlear duct and then opt for an array which will give full insertion of all electrodes.

Challenges for UK teams

Teams may feel constrained by the fact that children with PH are not traditional candidates, and may question whether they fall within NICE guidance because they perform well on speech tests in quiet. However, speech discrimination tests for NICE candidacy are only recommended for adults; for children, the focus is speech and language development. Additionally, surgeons who are inexperienced in hearing preservation techniques may lack the confidence to proceed with surgical intervention. Teams may want to wait for more paediatric evidence before recommending intervention, but waiting for categorical evidence may deny many children the ability to hear well enough to reach their potential.

Conclusion

All children in our group have preserved hearing and perform better with their CI than with their hearing aids, regardless of the level of preservation. All but one post-implant CAP2 outcome demonstrates improvements. SIR scores also show improvements for younger children, however our older children's speech intelligibility do not consistently improve post-implant. Our clinical observations suggest the benefits of early implantation apply to partial deafness in the same way as traditional candidates. Children with PH need early access to high frequency sound for discrimination (not just detection) and a multidisciplinary CI team is well placed to undertake assessment of these children's hearing and linguistic potential. However, not only is more professional education required to encourage early referrals from local teams, but more published research is also required to quantify improvements in functional hearing, speech and language, educational attainment, and quality of life following implantation. This will, in turn, increase professional confidence within CI teams and help families make informed decisions in a timely manner.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval None.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown, R.F., Hullar, T.E., Cadieux, J.H., Chole, R.A. 2010. Residual hearing preservation after pediatric cochlear implantation. Otology & Neurotology, 31(8): 1221–1226. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f0c649

- Gratacap, M., Thierry, B., Rouillon, I., Marlin, S., Garabedian, N., Loundon, N. 2015. Pediatric cochlear implantation in residual hearing candidates. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 124(6): 443–51. doi: 10.1177/0003489414566121

- Skarzynski, H., Lorens, A., Piotrowska, A., Skarzynski, P.H. 2010. Hearing preservation in partial deafness treatment. Medical Science Monitor, 16(11): CR555–562.

- Skarzynski, H., Van De Heyning, P., Agrawal, S., Arauz, S.L., Atlas, M., Baumgartner, W., et al. 2013. Towards a consensus on a hearing preservation classification system. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 133 (Suppl. 564): 3–13. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2013.869059