ABSTRACT

This historical overview uses a political ecology approach to examine agricultural change over time in Northwest Cambodia. It focuses on key historical periods, actors, and processes that continue to shape power, land, and farming relations in the region, emphasizing the relevance of this history for contemporary investments in agricultural extension services and research as part of the Zero Hunger by 2030 policy agenda for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Agricultural extension projects need to engage critically with historically complex and dynamic power, land, and farming relations – not only as the basis of social relations but as central to understanding the contemporary manifestation of farmer decision making and practice. Initiatives such as the SDGs replicate long histories of externally driven power-relations that orient benefits from changed practices towards elites in urban centers or distant global actors. Efforts to realize zero hunger by 2030 are endangered by neglect for the path-dependency of power-land-farming relations, which stretch from the past into the present to structure farmer decision making and practices.

Introduction

Global initiatives like the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) assume that increasing crop yields and intensifying commercial production are central to achieving food security.Footnote1 To date, these approaches have proceeded with little consideration for the historical and social relations that constitute rural realities and situate farmer decision-making.Footnote2 The global agenda giving rise to the SDGs prioritizes market-oriented policy reforms and rural development interventions that largely obscure questions of power. This assumes that “sustainable agriculture” is apolitical and ahistorical.Footnote3 This framing privileges the entrenched economic interests of political and financial elites across multiple scales.Footnote4 It also avoids the social complexities that shape the political economy of agrarian change, thereby limiting the effectiveness of agricultural extension as the primary means of achieving change for the UN’s second SDG, which is to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.”Footnote5

The Kingdom of Cambodia launched the "National Action Plan for Zero Hunger Challenge" with an aim to eradicate hunger and malnutrition by 2025. The plan relies on strengthening and expanding public and private agricultural extension services to increase productivity and sustainability.Footnote6 This globally-oriented and state-led emphasis on agricultural extension positions farmers as the subjects of change, often taking the form of transfers of agricultural knowledge and technologies as prompts for changed farmer practices.Footnote7 Those practices, though, are shaped by social relations as farmers navigate power structures that are neither fixed nor stable, but relational and emergent over time. Those structures are produced though encounters with place, human and nonhuman entities, institutions, knowledges, and practices, all of which temporarily destabilize and constrain the exercise of power.Footnote8 If future modalities of agricultural extension are to make substantial positive contributions to farmer wellbeing, then they must recognize and negotiate such relations – including their historical path dependency – as central to supporting and empowering farmers.

In 2015, at least eighty percent of rural Cambodians relied on agricultural production as their primary source of income and food security.Footnote9 The government’s agricultural extension policies have positioned agricultural extension as central to addressing the agricultural challenges faced by farmers. The policy refers to power in terms of “empowering” farmers and extension workers; land in reference to land management and productivity; and farming primarily in terms of productivity, income, technology, and commercialization. It makes these references without considering the role of history or social relations. The policy acknowledges that farmers are facing low productivity, labor precarity, and poverty, with many rural people selling their land and migrating to find other labor opportunities.Footnote10 These problems are, however, framed as the outcome of a “lack of or limited agricultural extension services, regulations, and system; lack of human resources, funding, techniques, and technology; lack of extension materials and packaging; and limited agricultural extension methodology and means.”Footnote11 However, this reading does not consider the multiple ways in which contemporary farming realities are shaped by past and present social, material, and economic relations that extend beyond the “farmgate.”Footnote12

In contrast to the suggestion that agricultural issues can simply be resolved through the transfer of improved technologies, advice, and materials, we use a political ecology lens to attend to the shifting social relations that have influenced farmer activities over time in Cambodia. These shifts are inseparable from the complex and turbulent histories of Cambodia’s northwest region. In what follows we emphasize the evolving relations between politics and land in the context of agrarian change at multiple scales. Our analysis foregrounds a history of social relations to better understand the struggles and challenges facing Cambodian farmers today, expanding the scope of activities that can be considered within efforts to improve agricultural livelihoods and outputs.

Like many rural areas throughout Cambodia, Northwest Cambodia has experienced a boom in the production of cash crops.Footnote13 This transformation has accelerated deforestation.Footnote14 Often framed as the “last forest frontier” or a “borderland,” the region has undergone rapid agricultural expansion of annual crops, including sesame, soybean, mung bean, maize, and cassava.Footnote15 The labor of demobilized Khmer Rouge soldiers and their families, as well as migrant farmers, has enabled these agrarian transitions, being connected to broader temporal and geographical political, capital, and market relations.Footnote16 Agrarian expansion and intensified production are also turning land into a financial asset for trade and exploitation.Footnote17 This makes farmers more susceptible to market fluctuations and to rapid environmental change, exacerbating challenges predicated on debt, migration, and food insecurity.Footnote18 Together, these transformations reinforce the economic interests of a small number of powerful elites who control local capital and economies.Footnote19

To better understand these patterns of agrarian change, ecological degradation, financial insecurity, and exploitation, we examine changing relations of power, land, and farming across seven key historical periods since the Angkor Era (see ). We contend that efforts to improve agricultural extension – exhibited most prominently in the global prioritization of SDGs – must recognize and engage with the historical foundations of rural inequalities if they are to positively contribute to farmers’ lives and livelihoods. Such a perspective is presently missing.

Table 1. Key historical drivers shaping agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia.

provides an overview of the seven historical periods examined in this article, allowing the continuities and changes across periods to be seen with a historical perspective. is organized around seven key drivers: spiritualities, materialities, labor and production, political and economic power, land control, mobility/isolation, and forest/degradation. Notable continuities include Therevāda Buddhism, wats as centers of culture, the centrality of rice production, elite rule in its various forms, political intervention by foreign powers, and agricultural expansion through forest exploitation. Alongside these continuities there have been major changes to labor and land tenure regimes (including slavery, collectivization, and individual land tenure), taxation systems, and elites. While specific behaviors and thinking have evolved (i.e., divisions of labor) overarching forces and priorities have remained remarkably consistent (i.e., disempowerment of local farmers and externally-driven efforts to raise agricultural production). While there have also been major periods of war and rebuilding, including shifts in the prominence of major non-rice crops, there remain consistencies that deserve recognition in the context of contemporary efforts to influence the agricultural sector via agricultural extension.

Methodology

Drawing from the work of different scholars,Footnote20 we examine seven periods, organized by broad changes in national-scale governance structures: the Angkor era (eighth to the fourteenth century); the post-Angkor period (fourteenth to the nineteenth century); the French Protectorate era (1863 to 1953); the Kingdom of Cambodia (1953 to 1975); Democratic Kampuchea (1975 to 1979); the People’s Republic of Kampuchea and transitional period (1979 to 1993); and the contemporary Kingdom of Cambodia (see ). In each period we focus on changing power structures, shifting approaches to land, and how farming may have changed or been affected.

Our analysis also is informed by a review of articles, edited books, policy documents, and project reports from state-led agencies, multilateral and bilateral donors, non-governmental organizations, academia, farmer movements, and the private sector, replicating a methodology implemented in the global context of agricultural extension.Footnote21 Where possible we have focused on the history of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia and, if not available, limited ourselves to documents focused on Cambodia. This focus has made the analysis more manageable, although we acknowledge that our analysis is partial and predominantly shaped by English language materials, academic scholarship, and government sources.

A brief history of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia

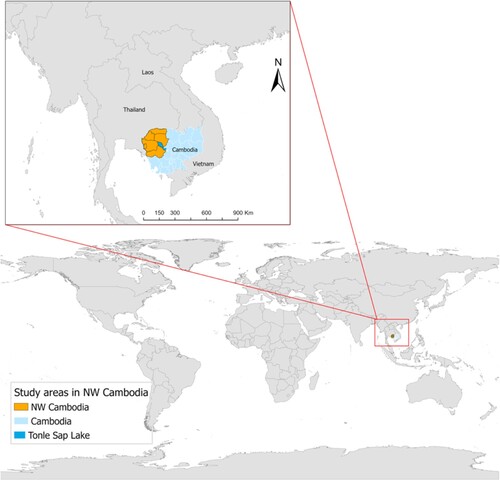

Cambodian territory is formed by lowlands and rivers that flow into the Mekong River Basin or the Tonle Sap Lake (). Monsoon flooding takes place in September and October each year, fertilizing rice plains and increasing the abundance of fish stocks.Footnote22 However, upstream hydropower dams and climate change in recent years have altered Mekong flood patterns, disrupting the seasonal supply of fish and other flood-connected resources in the floodplains.Footnote23 In response, rice farmers have increased their dry season rice production, but with uncertain long-term impacts. The highlands have a long history of smallholder farming and shifting cultivation.Footnote24 Non-swidden farming (e.g., maize, beans, cassava, fruit trees) in upland areas of Northwest Cambodia is relatively new compared to lowland areas, where paddy rice cultivation has long been practiced.Footnote25

An Indigenous rural animistic belief system known as neak ta (land and guardian spirits) has remained widespread since ancient times. Water, forest, and land spirits serve as territorial protectors (mcâs dẏk mcâs ṭī, “owners of water and land”), while other entities known as bralẏng manifest as humans, corporeal, and nonhuman entities.Footnote26 Misfortune and health issues are often associated with bralẏng.Footnote27 This Indigenous ontology has mixed with Buddhism, shaping understandings of territorial guardian spirits and deceased ancestors, who are considered inseparable from the land.Footnote28 The spirits of the dead continue to inhabit rural landscapes, at times manifesting through different interlocutors and dreams while also shaping the transfer of knowledge.Footnote29 Neak ta is at the heart of Khmer society and culture, shaping human and nonhuman interactions, including agricultural practices.Footnote30 These beliefs and practices have retained meaning and significance for many farmers throughout the seven periods discussed below and in the present.

Angkor Era

Battambang, the capital of the province of the same name, was founded in the eleventh century on the Sangker River.Footnote31 The Angkor Kingdom was an agrarian civilization that relied on social hierarchies to maintain control of the population. The King of Angkor mediated between cosmological and worldly orders while also taking attributes from land spirits.Footnote32 Social hierarchies were reinforced by royal institutions and patronage networks. The power of the king was exercised by appointees called okyas, which included five ministers and provincial and district governors.Footnote33 Both rice production and farming labor were subject to a ten percent tax. Periods of war with neighboring kingdoms located in present day Thailand and Vietnam increased demand for food reserves, which in turn required intensified modes of rice production and labor organization.Footnote34

During the thirteenth century, with the expansion of Therevāda Buddhism from Thailand to the area, the Angkor king evolved into the dhammaraja (a moral or righteous king). Rapid environmental changes during this period destroyed the complex water management system for which Angkor was famed, reducing irrigation capacity and limiting agricultural production.Footnote35

During the Angkor era, land was divided into three zones: kampong, the center of political and economic power; srok (sruk), the cultivated and domesticated world, which included srae – rice hinterlands along the Tonle Sap floodplain, shaped by complex water control and irrigation systems that enabled multiple harvests per year; and prey, forest land and remote villages, subjected to intensive resource exploitation and sometimes forced kidnappings for labor. Prey was often represented as a dangerous zone of threats, diseases, death, and outlaw practices, including spiritual power.Footnote36 Central to Khmer culture were Hindu rituals and protocols, leading to contrasts between “wild and tamed … dark haunted bushland versus inhabited open space.”Footnote37 In this context, civilization was seen as “the art of remaining outside the forest.”Footnote38 Kram, the traditional land tenure system, gave the king ownership, positioning him as the protector of land and custodian of human and spiritual peace.Footnote39 Coexisting customary and collective forms of land tenure and management were widespread. Farmers had land possession rights (paukeas) which they could claim by farming the land.Footnote40

Agricultural production during the Angkor era was predominately collectivized and took place around temples, which had access to irrigation.Footnote41 Although the distribution of labor during this period remains unclear, social hierarchical divisions positioned farmers as a lower caste.Footnote42 Slave labor was central to agrarian production, with some enslaved groups periodically moving to new areas in response to agricultural labor needs.Footnote43 This labor model supported the maintenance of networks of water reservoirs, which were central to the expansion of agricultural production across the Great Angkor region.Footnote44 Buddhist temples, known as wats, played a key role as places of encounter and spiritual protection, where ceremonies, social gatherings, and government meetings were held.Footnote45 Wats also served as gathering places for farmers to exchange information and knowledge, as well as venues where Buddhist monks likely offered training on agricultural practices and rites.Footnote46

Post-Angkor period

During the post-Angkor period (the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries), the political economy continued to be shaped by the king and the chovay srok patronage networks, but with the addition of growing foreign interests.Footnote47 Regional trade with the Kingdom of Ayutthaya enabled the expansion of Chinese maritime trade in Southeast Asia, and trade across the lower Mekong basin.Footnote48 Phnom Penh became increasingly influential as a regional center.Footnote49 The circulation of farming surpluses via trade reinforced the power of chovay srok through the rice taxation system and increased the influence of Chinese traders.Footnote50

Beginning in the Angkor period, tribal groups “collected the forest products that formed a major source of a monarch’s income and the bulk of the goods that Cambodia sent abroad.”Footnote51 However, this period was also marked by political instability due to occasional territorial invasions by Siam and other neighboring kingdoms, including Champa and Dai Nam. In the seventeenth century there were also attempts by Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and French mercenary troops and Catholic missionaries to gain control of the Mekong Delta to influence trade.Footnote52

Between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Kingdom of Siam took control of Battambang, fueling conflicts between central and northwest provinces in Kampuchea.Footnote53 In exchange for military protection, dissenting chovay srok gave the Siam king rights over forest resources and allowed the recruitment of labor for the Siam army.Footnote54 In this way, northwest Kampuchea resisted the centralization of power, a trend that continues to influence contemporary relations in Democratic Kampuchea.Footnote55

During the post-Angkor period most of the population in the northwest were farmers who relied primarily on rice production. At least 2,000 endemic varieties of rice have been identified in Kampuchea.Footnote56 However, the livelihoods of farmers and rural communities were regularly hampered by periods of environmental uncertainty, state taxes, forced labor, and warfare.Footnote57

French Protectorate (1863-1953)

The Mekong delta came under French control in 1862 when King Norodom of Kampuchea requested protection, establishing the French Protectorate.Footnote58 French colonial authorities maintained the power of the royal family as well as social hierarchies. Farmers continued to be governed by a complex web of political and religious values and power relations.Footnote59 Economic output focused on the production of rice, rubber, and timber.Footnote60 Most royal revenues were derived from Chinese operated opium farms, gambling concessions, and rice products such as wine and sugar.Footnote61

During the French Protectorate period, land was privatized, creating a distinction between paukeas (possession rights) and kamaset (ownership rights).Footnote62 The latter were used by French and urban investors to register ownership over forests and rubber concessions, with farmers’ land rights rarely recognized.Footnote63 The return of the northwest provinces by Siam during this time was followed by farmer migrations southward because of demographic pressure. Migration led to unequal distribution of land, which increased levels of insecurity and conflict.Footnote64 Land titles and transfers intensified the role of patronage networks, which led to problems with land concentration along the northwest border.

Colonial forest reserves were established and agreements between logging companies and colonial forest administration authorities regulated logging, excluding people and their livestock. This contributed to the proliferation of illegal smuggling routes involving local authorities and Thai traders.Footnote65 Farmers were required to pay their taxes in cash, which pushed farmers to sell their produce despite unfavorable conditions, increasing their debt, increasing land dispossession, and giving rise to wage labor.Footnote66 Corvée labor in lieu of taxes was widely enforced to maintain public works, including transportation networks.

In the 1930s, the emergence of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) led to the expansion of an anti-colonial movement across the region. In the 1940s, progressive Buddhist groups and the Khmer Issarak (Free Khmer Movement) protested colonial plundering and control.Footnote67 During World War II, Japanese forces weakened French power, resulting in Battambang falling under Thai control. In 1945 the Japanese declared a coup de force, which in the following years contributed to the end of French rule of Indochina. In 1946, the Thai government returned Battambang to France. Finally, King Norodom Sihanouk declared the independence of Cambodia in 1953.Footnote68

The Kingdom of Cambodia (1953-1975)

After King Norodom Sihanouk declared independence from France, foreign influence over the production of rice, rubber, and maize continued to expand.Footnote69 Reflecting global priorities arising from famines and concerns over population expansion,Footnote70 an agricultural extension program was established in 1957.Footnote71 An extension unit was created within the Ministry of Agriculture to increase rice, vegetable, and livestock production for export and to expand irrigation systems in the northwest. A top-down approach to extension was implemented, introducing cooperatives and a credit system while relying on radio and television campaigns to disseminate information.Footnote72

In 1955, the United States government signed a military aid agreement with Cambodia. However, in 1964 aid from the USA was rejected by King Sihanouk, who began a nationalization program.Footnote73 From 1965 to 1973, the US Air Force repeatedly bombed rural areas in Cambodia, initially targeting Viet Cong forces operating within Cambodia and later Cambodian revolutionary forces. These aerial attacks killed at least 600,000 Cambodians and left thousands of unexploded bombs across Laos and Cambodia.Footnote74

In 1967, farmer uprisings in Samlout in the northwest marked the beginning of the Cambodian Civil War, which lasted from 1967 until 1975. In this unstable context, the royal government deployed the military to take control of rice production in Battambang, collect taxes, and halt trade with communist groups.Footnote75

Colonial land and forest tenure arrangements were sustained during this period.Footnote76 While there was a halt to foreign concessions, the number of landless farmers increased from four percent to twenty percent between 1950 and 1970.Footnote77 Incentives from the royal government designed to provide access to and expansion of agricultural land facilitated the migration of families from the southwest to the northwest. The influx of labor resulted in the expansion of rice production from 1.7 to 2.5 million hectares, growing from thirty-four percent of total exports in 1957 to fifty percent in 1963.Footnote78

Extension services were interrupted during the war as domestic consumption of rice decreased. The war’s impact was amplified by high taxes and personal debt, which escalated the illegal trade of rice. Simultaneously, the government used military force to compel farmers to sell their rice to the state at below market rates.Footnote79 As in present circumstances,Footnote80 farmers relied heavily on credit to pay agricultural taxes. In response, beginning in the 1960s, farmers began mobilizing against corrupt government and military officials. As a result, the northwest region became a center for the Khmer Rouge.Footnote81

Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)

In 1975, Khmer Rouge forces took control of Phnom Penh. They forced approximately two million urban residents to relocate to rural areas.Footnote82 The Khmer Rouge leader, Pol Pot, prioritized collectivized rice productionFootnote83 and the complete abandonment of past cultural practices to enable the emergence of a new revolutionary order.Footnote84 These actions included consolidation of land and destruction of land titlesFootnote85 and the execution of all people linked to the previous government, including teachers, university officials, and the elderly.Footnote86

During this period, dissident Khmer Rouge troops in the Northwest continued the cross-border timber trade with Thai merchants.Footnote87 Alongside economic collectivization, the Khmer Rouge regime forcibly collectivized land and natural resources.Footnote88 Schools, religion, money, and private property were abolished.Footnote89 Forest concessions were terminated and access to forests was restricted.Footnote90 Landmines were used to control and limit access to agricultural lands. An estimated six million landmines were deployed around the country during and after the war.Footnote91 These explosives continue to shape contemporary land management practices and agricultural opportunities.Footnote92

All residents were organized in large collective farms. All production activities were performed by production groups, enforcing the separation of families and social networks, with some of these groups functioning as mobile brigades.Footnote93 Rice production was intensified using compost as a fertilizer, natural insecticides, and irrigation. The resulting surplus was exported, continuing the practice of producing profits for those in power. Small paddy fields were transformed into larger, uniform one hectare plots, destroying the traditional system of rice paddy cells while contributing to the loss of seed varieties.Footnote94

Importantly, the killing of farmers, particularly the elderly, resulted in a fragmentation of traditional knowledge and practices predicated on sharing, learning, and passing on ecological knowledge to younger generations.Footnote95 This loss contributed to the destruction of kinship relations, institutions, and moral norms.

The People’s Republic of Kampuchea and transitional period (1979-1993)

In 1979, a Khmer-Vietnamese military coalition took control of Phnom Penh, leading to the collapse of the Khmer Rouge government. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the northwest region was a center of Khmer Rouge resistance.Footnote96 Although the new government revoked forest use agreements signed by the Khmer Rouge with Thai military-aligned logging companies for their role in financing the insurgency, deforestation continued.Footnote97 At the national level, Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge soldier who had joined the Vietnamese forces during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War, consolidated power, eventually serving as prime minister from 1985 to 2023.

From 1979 to 1989, agricultural production in lowland areas was collective, with ten to fifteen families forming solidarity groups (Krom Samaki) that shared ownership of land. Some regions allowed private land use rights beginning in 1982, but only in 1989 was the Krom Samaki system formally replaced with private land ownership.Footnote98 Following the 1991 peace agreement between the government and the remnants of the Khmer Rouge, a new land law decreed state ownership of all land. This law granted individuals possession rights, yet in practice permitted some individuals to claim private land ownership while many farmers were unable to register their land claims.Footnote99

The World Bank and other international donors lobbied for the reintroduction of a forest concession system in the 1990s to fund post-conflict development via public-private partnerships.Footnote100 A coalition between Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and former King Sihanouk’s royalist party, the National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia (Front Uni National pour un Cambodge Indépendant, Neutre, Pacifique, et Coopératif, FUNCINPEC), enabled a forest concession system to be co-opted by political elites and used to appease potential insurgents, becoming an instrument for the accumulation of capital, land, and power.Footnote101 Patronage networks facilitated this transition, while also enabling the expansion of elite land capture; by 2001, at least thirty-nine percent of all land in Cambodia was classified as forest concessions.Footnote102 In addition, approximately five percent of the country’s territory was reserved for the military, contributing to the militarization of natural resource management.Footnote103

As people began resettling along the northwest frontier following the cessation of violence, vast areas of forest were cleared and converted to agricultural land. Many people died or were injured from landmines while clearing forest areas.Footnote104 Landmines have caused a dramatic health crisis, constrained rural mobility and farming practices, and had wide socioeconomic and environmental impacts. Clearance programs have been funded primarily by international donors and NGOs.Footnote105 By 2003 at least 64,000 individuals had lost their lives and another 25,000 had had traumatic amputations from mine blasts.Footnote106

Following the 1991 peace accord many landless individuals sought opportunities in the country’s northwest region, some returning to the villages where they had lived prior to the civil war.Footnote107 In an effort to appease former insurgents, the state offered livelihood alternatives to demobilized soldiers, which has been central to the expansion of the agrarian frontier and increased productivity.Footnote108

In 1979, the new government reactivated extension services.Footnote109 In 1980, a committee for extension development began disseminating technical agricultural knowledge to farmers in rural areas, primarily using mass media, booklets, pamphlets, and posters.Footnote110 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) worked with government agencies to support the reactivation of agricultural extension and the training of extension officers.Footnote111

The new Kingdom of Cambodia (1993-present)

A flood of international aid and investment followed the 1991 peace accord, influencing and distorting local economies as they were reoriented towards global markets.Footnote112 An emphasis on trade has continued to reinforce the political economies of former Khmer Rouge warlords and Thai military actors.Footnote113 As part of adopting a liberal economic model, the government ended subsidies for agricultural inputs such as water pumps, seeds, gasoline, fertilizer, and pesticides.Footnote114

In addition, beginning in 1998, a strategy for political and territorial reintegration, Samaharenekam, gave former Khmer Rouge soldiers positions within provincial and district administrations. Integration into government effectively ended lingering conflicts while also reinforcing the political and economic power relations of the Khmer Rouge.Footnote115 Integration also reinforced the power of lower-level Khmer Rouge representatives within newly created villages, resulting in land management that has continued to expand the agrarian frontier – a process that is pronounced across the northwest uplands.Footnote116 The 2001 Land Law helped to legitimize market-driven land acquisition.Footnote117 The Land Management and Administration Program (LMAP), a multi-donor project led by the World Bank and the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning, and Construction, supported the implementation of land reforms, strengthening institutional and legal frameworks.Footnote118 However, land ownership was only granted to people who occupied land before the law was promulgated, leaving farmers who had settled on land after 2001 without land rights.Footnote119

The state banned logging in 2002, ended the forest concession system, and replaced it with an economic land concession (ELC) system.Footnote120 As part of this process, over two million hectares of land were leased to private companies for seventy years.Footnote121 Social land concessions (SLC) were used to redistribute land to landless farmers.Footnote122 In response to escalating conflicts between concession holders and individual smallholders, many of whom had been forcibly evicted and dispossessed of their land, the state implemented a new ELC policy in 2012. This enabled the fast-tracking of land titles in areas that overlapped with Economic Land Concessions (ECL) but went much beyond as it also targeted areas identified as ex-forest concessions, protected areas, and production forests.Footnote123 The process was interrupted in 2013 after national elections.Footnote124 The result has been the concentration of thirty percent of all arable land in the hands of one percent of Cambodians.Footnote125 Importantly, communities have mobilized against this ELC, protesting and submitting petitions while also facing intimidation and violence.Footnote126

Although specific land control practices are diverse, the redistribution of land has exacerbated the divide between farmers and political elites, which in the northwest has been influenced by former Khmer Rouge soldiers turned warlords.Footnote127 In some instances, former Khmer Rouge leaders have become members of government. This highlights some of the complexities of land struggles and contradictions between different forms of land control and state formation processes, often negotiated individually between elites and households at the intersection of former Khmer Rouge power structures and the neoliberal state.

Accelerated deforestation in the region has followed the diversification and expansion of cash crops such as maize, cassava, and fruit trees. These processes have increased migration from rice-growing provinces and from refugee camps.Footnote128 Complex and changing land relations have shaped migration patterns, reflecting the need to access livelihood opportunities and secure land, as well as people’s desires to live in proximity to family and social networks.Footnote129 Local elites, including village chiefs, have acted as intermediaries between farmers and foreign industrial groups, working as vendors of agricultural inputs and in the commodification and trading of agricultural products.Footnote130

In 1994 the government created the Council for Agricultural and Rural Development (CARD) and the Credit Committee for Rural Development (CCRD) to facilitate policy development and coordination between ministries. In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry was replaced by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) in 1996. In this new institutional context, agriculture is governed by four national institutions:Footnote131 the MAFF, the Ministry of Rural Development (MRD), the Ministry of Environment (MOE), and the Secretary of State of Women’s Affairs (SSWA). Since the 1990s, multiple projects have been implemented to improve infrastructure and agricultural production. These projects have been funded by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and a wide range of other aid agencies.

Central to the modernization of the Cambodian agricultural sector has been an orientation towards international markets. Agricultural extension programs have been positioned as the means for achieving national aims, including developing and expanding extension systems; improving management, including planning and evaluation systems; building capacity at all levels within extension systems; developing and improving information communication technologies and strategies; developing provincial and district information systems; and supporting the development of farmer organizations.Footnote132

Interventions have remained largely crop-oriented, focused on pest management, variety improvement, and integrated nutrient management. However, in practice, few farmers have had access to these services. An estimated one percent of farmers had access to extension services in 2007, with ten percent being women; in 2013, just twenty-seven percent of households were able to access extension services.Footnote133 Government efforts in agricultural extension have largely focused on increased rice production for export.Footnote134 Despite this state focus on rice production, farmers have diversified their activities, seeking access to market opportunities for crops such as maize, cassava, cashews, rambutan, durian, and mangos. However, farmers continue to experience structural and institutional constraints linked to land tenure, market failures, the prevalence of an informal sector, and a limited transport infrastructure.Footnote135

Current national policy emphasizes diversification of agricultural production as a means to achieve the SDGs. This effort endorses the transformation from “family-owned cultivation to manageable agro-commercial production,” as emphasized by the Cassava National Policy 2020-2025.Footnote136 The plan envisions increased market-driven agricultural production, enabled by the availability of microcredit.Footnote137 This trajectory in the context of weak government regulations, the uncertainties and economic toll of the global COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote138 and climate changeFootnote139 are likely to accelerate land loss, debt-driven migration, and food insecurity amongst smallholder families.Footnote140

Discussion

Our review highlights the value of adding historical context to contemporary agricultural debates and exploring the path-dependent structures that situate contemporary power, land, and farming relations. Our political position foregrounds the rights and struggles of smallholder farmers in order to contribute to more sustainable and equitable agriculture livelihoods. contextualizes seven key drivers of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia, assembled from the literature to reflect the complex forces that have shaped farmer livelihoods. The table is an effort to guide perspectives on long-standing processes (spiritualities, debt and taxes, patronage networks, and migration) as well as more recent changes (increased cash crops, land privatization, and individualized labor). The table also highlights the destructive period of Khmer Rouge rule and the breakdown of social relations and knowledge that, like water and land spirits (mcâs dẏk mcâs ṭī), haunt contemporary efforts to increase productivity and livelihood development. That the sustainable development goals aimed at combating hunger, food insecurity, and poor nutrition remain central suggests that recent changes have been insufficient to grapple with longer term processes, such as financial precarity associated with taxes and debt, ongoing patterns of elite land concentration, and the exploitation of rural laborers.Footnote141 Our analysis also suggests that institutions that have demonstrated longevity, such as Buddhist temple communities, continue to be integral to rural life and may provide a resource for collaboratively reimagining ways of supporting rural farmers to realize a good life.Footnote142 In the following sections we discuss these historic trends as they relate to power, land, and farming below.

Power

The prevalence and relevance of patronage networks in shaping power, land, and farming is central to the history of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia. Complex histories of war, environmental change, and Indigenous and Buddhist ontologies have been at the heart of human and nonhuman relations in Cambodia.Footnote143 These hierarchical, patron-client relations have historically benefitted the monarchy and provincial authorities as part of efforts to enforce the power of political elites across multiple scales.Footnote144 Importantly, these relations have not been static, but have been shaped by foreign actors, development agencies, private investors, and farmer uprisings – often leading to war and violence. This history establishes a path dependency that is co-productive of what is presently possible.Footnote145 A consistent theme, evident with regards to farmers’ experiences, is the assertion of external power, which controls and profits from agricultural production and trade.Footnote146

For example, the emphasis on rice production during the Angkor period reflected a need to feed the military that enforced the power of the monarchy and chovay srok. The requirement for peasants to produce surplus rice organized agricultural practices as a way of fulfilling external interests and maintaining control of that very system of production. This model of production-consumption was, during the post-Angkor period, connected with regional and international trade, which benefited elite interests. This pattern was retained by French colonial authorities, who facilitated the extraction of agricultural resources to maintain dependency relations. These relations were also central to strengthening anti-communist efforts in Southeast Asia, including the interests of the United States. Perhaps most surprisingly, the Khmer Rouge, despite their agrarian collectivization language, consolidated land for large-scale production, in service yet again to foreign markets. This pattern was covertly maintained by disenchanted Khmer Rouge warlords through illicit border trade and was later entrenched in the peace accords as a way of yoking former revolutionaries into government. During the more recent neoliberal turn, this pattern of elite capture of agricultural production has been a key structural challenge facing agricultural extension efforts to improve farmer livelihood development, as exemplified in the current policy for the promotion of paddy production and export.Footnote147 In this light, from the perspective of smallholder farmers in Northwest Cambodia, initiatives such as the SDGs replicate long histories of externally driven power relations that orient benefits from changed practices towards elites in urban centers or distant global actors, with an assumed but tenuous link between productivity and improved wellbeing.Footnote148 SDG advocates would benefit from recognizing and accepting these historical similarities to understand local interpretations of sustainability proposals, policies, and programs.Footnote149

Land

The complex entanglement between land, social relations, and agricultural transitions in Northwest Cambodia is tied to patterns of migration to, through, and from the region.Footnote150 While past migration patterns were predominantly shaped by war, conflicts, and settlement programs, recent migration trends have been more complex. For example, multiple modes of in-migration, including ex-Khmer Rouge resettlement, refugee repatriation, and voluntary in-migration by farming households from surrounding districts and beyond, have followed the expansion of agricultural land through deforestation. According to the 2008 Census, approximately sixty-eight percent of the population in four frontier districts in Pailin and Battambang were recent migrants.Footnote151 At the same time, out-migration driven by debt, dispossession, and the cumulative effects of environmental shocks has become a dominant feature.Footnote152 Out-migration of individual family members for wage employment – whether cyclical or more permanent – carries important implications for the age and sex composition of the left-behind agricultural workforce, smallholder farmers’ investment decisions, and everyday social relations.Footnote153

Isolation is key to understanding farmers and land in Northwest Cambodia. For example, in the pre-Angkor period, prey lands were considered to be areas of danger and potential harm, encircling rural villages and limiting farmers’ opportunities to forge connections. During the colonial period, authorities controlled trade networks and limited people’s mobility. In the Khmer Rouge period, control over mobility was even stricter, including a forced mass exodus of urban residents into rural regions. In the present period, debt is driving new forms of isolation and mobility, as farmers lose their land or are left searching for wage labor opportunities to pay or flee their debts.Footnote154 Farmers’ isolation stands in contrast to the large-scale development and upgrading of provincial and national road networks in Northwest Cambodia during the last decade.Footnote155

Land is central to these agrarian transitions and to patronage networks that are sustained by the political economy of agrarian production.Footnote156 It is in this context that agricultural extension has been promoted as a means of achieving the SDGs. With a state focus on diversifying agricultural production, crops such as cassava and fruit trees are being promoted, along with new materializations of patron-client relations. Transformations have been facilitated by loans and more efficient technologies to increase crop yields. However, as farmers struggle in response to environmental and financial uncertainty, many are migrating and/or working extended hours, thereby becoming more socially isolated and reliant on distant markets to sustain their livelihoods.Footnote157 In the context of sustainable development, isolation affects the nature of farmers’ market opportunities. The SDGs assume that farmers benefit from higher competition and will receive optimal returns on their activities, typically as a result of competition between actors and market connections. However, farmers in Northwest Cambodia experience extreme price variability at harvest because of market failures rooted in monopolistic relations grounded in production that is oriented towards external objectives and priorities.Footnote158 These historically rooted social relations, which at once isolate farmers and force families to find additional sources of income, are pivotal issues to address in a reimagined program of agricultural production that would contribute to sustainable development and the SDGs.

Farming

Historically, agriculture and food production have been utilized to control rural populations.Footnote159 Food production has been used to feed the militaries that kept people in check during the pre- and post-Angkor periods. Similarly, food production was used to fuel the colonial protectorate, which was a way of keeping royal and military power satiated. Most starkly, agriculture was the basis of Khmer Rouge control. Throughout Cambodia’s history, agricultural production has served the interests of external actors while simultaneously reducing farmers’ agency and autonomy.

Agricultural production in Northwest Cambodia continues to be a means of control, now also shaping the exodus of rural populations to maintain the flows of labor needed for development activities in urban centers.Footnote160 Seen in its historical context, agricultural production not only feeds urban populations and generates export revenue, it maintains patronage networks and keeps rural populations in check. The history of Northwest Cambodian agrarian change reveals a continuous commitment to external interests, often at the expense of farmers’ livelihoods and wellbeing. The monarchy, chovay srok, Phnom Penh rulers, French colonialists, the US government, the Khmer Rouge, contemporary microfinance institutions, international elites, foreign hedge funds, international aid agencies and donors, and the nascent SDG consortium have framed Cambodian farmers as a means for achieving externally determined objectives. Evident throughout is a presumption of power resulting in a disregard for the lives and lived experiences of farmers.Footnote161

At present, the government continues to encourage agriculture production for export, equating surplus production with increased farmers’ wellbeing.Footnote162 This approach gives little consideration to the uneven and unjust distribution of benefits and the socio-environmental impacts of industrial agriculture.Footnote163 Farmers see very little of the profits from these activities, with agricultural extension primarily oriented towards national aims.

Future directions

Our review suggests that the SDGs, and SDG 2 specifically (to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture”Footnote164), fit comfortably within a history of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia. The similarities are striking and somewhat disconcerting. In this context, agricultural extension can be understood as the pointy end of a long-term, consistent orientation towards increased production, which has coalesced around the modernization of Cambodian agricultural production, now framed through the UN’s Strategic Development Goals. But like the historical periods reviewed above, extension-driven SDG2 activities privilege external objectives divorced from the daily lives of Cambodia’s farmers. Proposing solutions that are detached from the local context and the complex social, political, and economic dynamics that shape farmer decision-making produces unrealistic imaginaries of agrarian contexts. Engaging with these complex social and political relations is much more difficult than providing agricultural advice and equipment, but it is crucial if farmers in Northwest Cambodia are to emerge from patterns of intergenerational struggle and exploitation to tackle historically-rooted inequalities. Our review shows that while the traditional focus of agricultural extension in growing improved quantities of quality crops may be desirable,Footnote165 its impact on smallholders will be constrained until historically uneven power relations are mitigated through farmer-oriented reforms.

If governments and intergovernmental institutions like the FAO are to make progress on the Sustainable Development Goals and address trade-offs (e.g. SDG 2 on zero hunger and SDG 10 on reduced inequalities), more than improved seeds, equipment, and knowledge are needed. Our analysis suggests that there has to be a willingness to engage with more difficult social and political issues, including historic patterns of exploitation that situate and suppress rural development. Our review of agrarian change in Northwest Cambodia highlights the value of critically engaging with the history of farming and rural realities to work with farmers and authorities in developing agricultural extension interventions that do not exacerbate conflict and precarity.Footnote166 For instance, migration no longer serves merely as a means to diversify the risks of farming; it has become a preferred route and strategy for households to attain income, food security, and social mobility, including to compensate for low agricultural returns.Footnote167

For agricultural initiatives to foster real benefits for farmers, the international community must prioritize the lived experiences of farmers to understand and transform the political economies of agricultural production, opening spaces for farmers to decide and negotiate what they consider constitutes a good life.Footnote168 Such programs will require moving beyond top-down technocratic approaches and an overreliance on short-term donor funding for market-based solutions. An integrated approach to farming that blurs the lines between agricultural extension and rural development is needed, one that is committed to working with farmers within their social networks. It is pivotal to nurture transdisciplinary pathways and alliancesFootnote169 between farmers and key actors within government, the public and private sector, donors, civil society organizations, and research institutions in order to foster collective action and open space for agrarian reform. Central to such an objective are approaches that recognize – and where needed refuse – historical path dependency, accepting that efforts to alter the power, land, and farming structures that shape farmer decision making in the present must include simultaneous appreciation for the past.

Acknowledgments

The research team acknowledges and thanks all participants in the research, especially Cambodian farmers who generously provide their time and insights. Brian Cook thanks Wageningen University Communication and Innovation Studies (CIS) and Sociology of Development and Change (SDC) groups for hosting his research leave while working on this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Brian R. Cook

Brian R. Cook is an associate professor at the University of Melbourne. A human geographer, Brian is interested in socio-environmental controversies, especially in the context of public participation in the context of risk.

Paula Satizábal

Paula Satizábal is a postdoctoral researcher at Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity at the University of Oldenburg. A human geographer, Paula is interested in the political ecology of marine governance.

Van Touch

Van Touch is a cropping system researcher based at the University of Melbourne. His professional experiences are around implementing agronomic on-farm research, experimenting crop simulation modelling, analyzing climate change projections, analyzing agricultural market value chains, and coordinating several agricultural research and development projects.

Andrew McGregor

Andrew McGregor is an associate professor at the Macquarie School of Social Sciences. Andrew is a human geographer who studies human-environment interactions in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Jean-Christophe Diepart

Jean-Christophe Diepart is a geo-agronomist based at the School for Field Studies, Cambodia. JC has worked in Cambodia since 2002. He has been involved in various research projects looking at agrarian changes in lowland and upland regions of Cambodia and in the Mekong region as a whole.

Ariane Utomo

Ariane Utomo is a social demographer, working primarily on marriage and family change in Indonesia. Her research examines how the dynamics of demographic and social change relate to attitudes about gender roles; school to work transitions; women’s employment; marriage, fertility and family patterns; and the nature of inequalities and social stratification.

Nicholas Harrigan

Nicholas Harrigan is a senior lecturer in Quantitative Sociology at Macquarie University. His major areas of research include social networks, particularly networks of conflict; low wage migrant workers in Australia and Asia; and participatory approaches to social research.

Katharine McKinnon

Katharine McKinnon is the Director of the Centre for Sustainable Communities at the University of Canberra, and Chair of the Board of Directors of the Community Economies Institute. She is a human geographer with extensive field experience in participatory action research in a range of Asia-Pacific contexts.

Pao Srean

Pao Srean is Dean of the Faculty of Agriculture and Food Processing at the National University of Battambang, Cambodia. His research has focused on upland and lowland cropping systems in Northwest Cambodia.

Thong Anh Tran

Thong Anh Tran is a human ecologist based at the University of Melbourne. Thong has extensive experience in Mainland Southeast Asia. He researches climate-development dynamics in the Mekong region, with a particular focus on transboundary environmental governance, agrarian transformation, livelihood resilience, and climate change adaptation.

Andrea Babon

Andrea Babon is an environmental social scientist with almost twenty years’ experience working at the interface between research, policy, and practice. Her research focuses on environmental policy and governance through a political ecology lens, examining power relations and equity implications of global environmental governance.

Notes

1 Blesh et al. Citation2019; Tomlinson 2013.

2 Allahyari et al. Citation2019; Fraser et al. Citation2016.

3 Kumi et al. Citation2014; Leach et al. Citation2020.

4 Blesh et al. Citation2019; Hope Citation2020; Leach et al. Citation2020.

5 United Nations Citation2018.

6 CARD Citation2016.

7 Cook et al. Citation2021.

8 Li Citation1999; Ahlborg and Nightingale Citation2018.

9 MAFF Citation2015.

10 Bylander, Citation2014, Citation2015.

11 MAFF Citation2015, 1.

12 See Hope Citation2020.

13 Kem Citation2017; Mahanty and Milne Citation2016.

14 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

15 Mahanty and Milne Citation2016; Kong et al. Citation2019; Milne Citation2015.

16 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; McMichael Citation2008; Milne and Mahanty Citation2015a.

17 Diepart and Sem Citation2016; Green Citation2019; Li Citation2014; LICADHO and STT Citation2019.

18 Gyorvary and Lamb Citation2021; Montgomery et al. Citation2017; Touch et al. Citation2016; Green Citation2019.

19 Diepart and Sem Citation2016; Gyorvary and Lamb Citation2021.

170 Please remove the grey shading of all cells in this table. I have deleted the explanation in the caption. It is too vague and does not add significantly to the paper.

20 Chandler, 2018; Corfield, Citation2009; Diepart and Dupuis, Citation2014; Kong, Citation2019; Slocomb, Citation2010; Sothirak et al., Citation2012.

21 Cook et al. Citation2021.

22 Vickery Citation1989; Pillot Citation2007.

23 Pokhrel et al. Citation2018; Sneddon and Fox Citation2012.

24 Cramb et al. Citation2020.

25 Montgomery et al. Citation2017.

26 Gyallay-Pap Citation1989; Work Citation2017, 4.

27 Work Citation2017.

28 Baek Citation2010.

29 Beban and Work Citation2014; Work Citation2017.

30 Gyallay-Pap Citation1989; Baek Citation2010.

31 Han and Lim Citation2019.

32 Gyallay-Pap Citation1989; Work Citation2017.

33 Chandler 1998.

34 Mak Citation2001.

35 Buckley et al. Citation2010.

36 See Arensen Citation2012; Chandler 1998; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014, 450.

37 Scott, Citation2009, 112.

38 Chandler, Citation2008, 125.

39 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; Greve Citation1993.

40 Diepart Citation2015.

41 Hall Citation2011.

42 Chandler 1998.

43 Klassen et al. Citation2021.

44 Pottier Citation2000.

45 Arensen Citation2012.

46 Gyallay-Pap Citation1989.

47 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

48 Vickery Citation1977.

49 Rungswasdisab Citation1995.

50 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; Mak Citation2001; Rungswasdisab Citation1995.

51 Chandler Citation2008, 121.

52 Hall Citation2018.

53 Chandler 1998.

54 Rungswasdisab Citation1995.

55 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; Rungswasdisab Citation1995.

56 Cramb et al. Citation2020; Helmers Citation1997.

57 Cramb et al. Citation2020.

58 Chandler 1998.

59 Vickery Citation2010.

60 Chandler 1998; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

61 Chandler 1998; Cooke Citation2007.

62 Diepart Citation2015, 8; Guillou Citation2006.

63 Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

64 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

65 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

66 Cooke Citation2007; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

67 Chandler 1998; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

68 Chandler 1998; Citation1986.

69 Chandler 1998; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

70 Boserup, Citation2014.

71 Ke and Babu Citation2018.

72 Heng et al. Citation2023; McNamara 2016; Ke and Babu Citation2018.

73 Vickery Citation1989.

74 Kiljunen Citation1984; Owen and Kiernan Citation2006; Vickery Citation1989).

75 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

76 Ibid.

77 Kiernan, Citation1996.

78 Vickery Citation1989, 43.

79 Vickery Citation1989, 43.

80 Bateman Citation2018; Green Citation2022b; Green Citation2023.

81 Diepart and Dupuis 2104.

82 Vickery Citation1989.

83 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

84 Chandler, 2018; Clayton, Citation1998; Lunn, Citation2004.

85 Clayton, Citation1998; Lunn, Citation2004

86 Clayton, Citation1998; Kiernan, Citation2003; Raffin, Citation2012.

87 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

88 Yang Saing Citation1999, 20.

89 Chandler 1998; Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

90 Tyner Citation2008.

91 Matthew and Rutherford Citation2003; Merrouche Citation2011.

92 Williams and Dunn Citation2003.

93 Raffin, Citation2012.

94 Himel Citation2007.

95 Zucker Citation2008.

96 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

97 Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

98 Yang Saing Citation1999, 20.

99 Biddulph 2014a; Diepart Citation2015.

100 Le Billon Citation2002; Barney Citation2010.

101 Global Witness Citation2007; Jacobsen and Stuart-Fox Citation2013; Vickery Citation2007.

102 Diepart Citation2015, 12; Le Billon Citation2002; Jacobsen and Stuart-Fox Citation2013.

103 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

104 Matthew and Rutherford Citation2003, 48. Indeed, access to arable land has been limited with an estimate of at least twenty-five percent of potential agricultural land still littered with landmines and unexploded ordinance.

105 Merrouche Citation2011.

106 Rodrigues Citation2023.

107 Diepart Citation2015.

108 Biddulph 2014a.

109 Yang Saing Citation1999.

110 Heng et al. Citation2023.

111 Ke and Babu Citation2018; Soeun Citation2012.

112 Ear Citation2012.

113 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

114 Yang Saing Citation1999, 19.

115 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

116 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; Mahanty Citation2019; Mahanty and Milne Citation2016.

117 CCHR Citation2013, 11.

118 Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

119 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015

120 Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015

121 Milne and Mahanty 2015b; Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

122 Grimsditch and Henderson Citation2009.

123 Diepart Citation2015.

124 Müller Citation2013; Scurrah and Hirsch Citation2015.

125 Neef et al. Citation2013, 1086. As an example, the Pheapimex Co., Ltd. ELC, established in 2000, controls 315,928 hectares of land in the provinces of Pursat and Kampong Chhnan, impacting the lives and livelihoods of over 100,000 people in 111 villages (Bandler and Focus on Global South Citation2018,14).

126 See Bandler and Focus on Global South Citation2018; Guttal 2014; Lamb et al. Citation2019.

127 Biddulph 2014b; Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

128 Pilgrim et al. Citation2012.

129 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014.

130 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014, 456.

131 Yang Saing Citation1999, 15.

132 Soeun Citation2012, 1.

133 Leapheng Citation2018.

134 RGC Citation2010.

135 ADB Citation2012.

136 RGC, Citation2020.

137 See Green and Estes 2018; Green Citation2023 for discussion of debt implications.

138 Brickell et al. Citation2020.

139 Frewer Citation2021; Marcaida III et al. Citation2021; Sok et al. Citation2021; Touch et al. Citation2020.

140 Bylander Citation2014, Citation2015; Pilgrim et al. Citation2012.

141 Green Citation2022; Mahanty Citation2019.

142 McKinnon, Healy, and Dombroski Citation2019.

143 Beban and Work Citation2014; Work Citation2017.

144 Chandler 1998; Diepart Citation2015.

145 Pente et al. Citation2015.

146 Mahanty and Milne Citation2016.

147 Green Citation2021.

148 Ghosh et al., Citation2022.

149 Touch et al. Citation2023.

150 Bylander, Citation2015.

151 Kong et al. Citation2019.

152 Bylander Citation2015; Kong et al. Citation2019; Pilgrim et al. Citation2012; Diepart and Ngin Citation2020.

153 Bylander Citation2015; Zimmer and Knodel Citation2013.

154 Green Citation2022a; Green and Bylander Citation2021; Natarajan et al. Citation2021.

155 See Kong et al Citation2019.

156 Diepart and Dupuis Citation2014; McMichael Citation2008; Nam Citation2020.

157 See Bylander Citation2015; Mahanty and Milne Citation2016; Gyorvary and Lamb Citation2021; Green and Estes Citation2019; Green Citation2023.

158 Newby Citation2018.

159 Bartlett, Citation2008.

160 Bateman et al. Citation2019.

161 Frewer Citation2021.

162 Ghosh et al., Citation2022.

163 Lichtfouse 2009; Mahanty and Milne Citation2016.

164 United Nations Citation2018.

165 Ghosh et al., Citation2022.

166 Peluso 2012, 86.

167 Bylander Citation2014; Citation2015.

168 McKinnon et al. Citation2019; Dombroski et al. 2019.

169 See Anderson and Leach Citation2019.

References

- Agricultural Development Bank. 2012. Rural Development for Cambodia key Issues and Constraints. Philippines: Agricultural Development Bank.

- Ahlborg, H. and Nightingale, A.J. 2018. “Theorizing Power in Political Ecology: The Where of Power in Resource Governance Projects.” Journal of Political Ecology 25: 381–401.

- Allahyari, M.S., Sadeghzadeh, M., and Branch, R. 2019. “Agricultural Extension Systems Toward SDGs 2030: Zero Hunger.” In W.L. Filho (editor), Zero Hunger, 1–11. Cham: Springer.

- Anderson, M., and Leach, M. 2019. Transforming Food Systems: The Potential of Engaged Political Economy. IDS Bulletin 50 (2). Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

- Arensern, L.J. 2012. “Displacement, Diminishment, and Ongoing Presence. The State of Local Cosmologies in Northwest Cambodia in the Aftermath of War.” Asian Ethnology 71 (2): 159–178.

- Baek, D.S. 2010. Neak ta Spirits: Belief and Practices in Cambodian Folk Religion. Deerfield, Illinois: Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

- Bandler, K. and Focus on Global South 2018. Pheapimex Land Conflict. Case Study Report. Accessed December 18, 2023: https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Cambodia-PPM-Report-A4.pdf.

- Barney, K. 2010. “Large Acquisitions on Forest Lands: Focus on Cambodia.” Unpublished report. Accessed December 18, 2023: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352371705_Large_Acquisition_of_Rights_on_Forest_Lands_Focus_on_Lao_PDR.

- Bartlett, A. 2008. “No More Adoption Rates! Looking For Empowerment in Agricultural Development Programs.” Development in Practice 18 (4-5): 524–538.

- Bateman, M. 2018. “Cambodia: The Next Domino to Fall?” In Milford Bateman, Stephanie Blankenburg, and Richard Kozul-Wright (editors), The Rise and Fall of Global Microcredit: Development, Debt and Disillusion. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Bateman, M., Natarajan, N., Brikell, K., and Parsons, L. 2019. “Descending Into Debt in Cambodia. Window on Asia.” Made in China. Accessed December 18, 2023: https://madeinchinajournal.com/2019/04/18/descending-into-debt-in-cambodia%ef%bb%bf%ef%bb%bf/.

- Beban, A., and C. Work. 2014. “The Spirits are Crying: Dispossessing Land and Possessing Bodies in Rural Cambodia.” Antipode 46 (3): 593–610.

- Bennett, C. 2018. “Karma After Democratic Kampuchea: Justice Outside the Khmer Rouge Tribunal.” Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal 12 (3): 68–82.

- Bernstein, H. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Biddulph, R., 2014. Cambodia’s Land Management and Administration Project. WIDER Working Paper 2014/086. New York: World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Biddulph, R. 2014. “Can Elite Corruption be a Legitimate Machiavellian Tool in an Unruly World? The Case of Post-conflict Cambodia.” Third World Quarterly 35 (5): 872–887.

- Blesh, J., Hoey, L., Jones, A.D., Friedmann, H., and Perfecto, I. 2019. “Development Pathways Toward ‘Zero Hunger’.” World Development 118 (C): 1–14.

- Boserup, E. 2014. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. London: Routledge.

- Brickell, K., Picchioni, F., Natarajan, N., Guermond, V., Parsons, L., Zanello, G., and Bateman, M. 2020. “Compounding Crises of Social Reproduction: Microfinance, Over-Indebtedness and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” World Development 136.

- Briggs, L. P. 1946. “The Treaty of March 23, 1907 Between France and Siam and the Return of Battambang and Angkor to Cambodia.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 5 (4): 439–454.

- Buckley B, Anchukaitis K, Penny D, Fletcher R, Cook E, et al. 2010. “Climate as a Contributing Factor in the Demise of Angkor, Cambodia.” PNAS 107: 6748–6752.

- Bylander, M. 2014. “Borrowing Across Borders: Migration and Microcredit in Rural Cambodia.” Development and Change 45 (2): 284–307.

- Bylander, M. 2015. “Depending on the Sky: Environmental Distress, Migration, and Coping in Rural Cambodia.” International Migration 53 (5): 135–147.

- Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR). 2013. Cambodia: Land in Conflict – An Overview of the Land Situation. Phnom Penh: CCHR.

- Chandler, D. 1986. “The Kingdom of Kampuchea, March-October 1945: Japanese-Sponsored Independence in Cambodia in World War II.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 17 (1): 80–93.

- Chandler, D. 2008. A History of Cambodia (fourth edition). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Clayton, T. 1998. “Building the New Cambodia: Educational Destruction and Construction Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979.” History of Education Quarterly 38 (1): 1-16.

- Cook, B.R., Satizábal, P. and Curnow, J. 2021. “Humanizing Agricultural Extension: A Review.” World Development 140.

- Cooke, N. 2007. “King Norodom’s Revenue Farming System in Later-Nineteenth Century Cambodia and his Chinese Revenue Farmers (1860–1891).” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 1: 30–55.

- Corfield, J. 2009. The History of Cambodia. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Council for Agricultural and Rural Development (CARD), Government of Cambodia. 2016. National Action Plan for the Zero Hunger Challenge in Cambodia (NAP/ZHC 2016-2025). Phnom Penh: Council for Agricultural and Rural Development.

- Cramb R., Sareth C., and Vuthy T. 2020. “The Commercialization of Rice Farming in Cambodia.” In R. Cramb (editor), White Gold: The Commercialization of Rice Farming in the Lower Mekong Basin. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 2012. On Intersectionality: The Essential Writings of Kimberle Crenshaw. New York: New Press.

- Deth, S.U. 2009. “The People’s Republic of Kampuchea 1979-1989: A Draconian Savior?” MA Thesis, Center for International Studies, Ohio University.

- Diepart, J.C. 2015. “The Fragmentation of Land Tenure Systems in Cambodia: Peasants and the Formalization of Land Rights.” Country Profile No.6: Cambodia. Paris: Technical Committee on Land Tenure and Development, Agence Francaise Development.

- Diepart, J.C., and Sem. T. 2016. “Fragmented Territories: Incomplete Enclosures and Agrarian Change on the Agricultural Frontier of Samlout District, North-west Cambodia.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (1): 156–177.

- Diepart, J.C., and Dupuis, D. 2014. “The Peasants in Turmoil: Khmer Rouge, State Formation, and the Control of Land in Northwest Cambodia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41(4): 445–468.

- Diepart, J. C., and Ngin, C. 2020. “Internal Migration in Cambodia.” Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia: A Cross-National Comparison. New York: Springer, 137-162.

- Dombroski, K., Healy, S., and McKinnon, K. 2018. “Care-full Community Economies.” In Christine Bauhardt and Wendy Harcourt (editors), Feminist Political Ecology and the Economics of Care, 99-115. London: Routledge.

- Doss, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A. and Theis, S. 2018. “Women in Agriculture: Four Myths.” Global Food Security 16: 69–74.

- Ear, Sophal. 2012. Aid Dependence in Cambodia: How Foreign Assistance Undermines Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fraser, E., Legwegoh, A., Krishna, K.C., CoDyre, M., Dias, G., Hazen, S., Johnson, R., Martin, R., Ohberg, L., Sethuratnam, S. and Sneyd, L., 2016. “Biotechnology or Organic? Extensive or Intensive? Global or Local? A Critical Review of Potential Pathways to Resolve the Global Food Crisis.” Trends in Food Science and Technology 48: 78-87.

- Frewer, T. 2021. “Reconfiguring Vulnerability: Climate Change Adaptation in the Cambodian Highlands.” Critical Asian Studies 53 (4): 476-498.

- Ghosh, R., Otto, I., and Rommel, J. 2022. “Editorial: Food Security, Agricultural Productivity, and the Environment: Economic, Sustainability, and Policy Perspectives.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 10: 916272.

- Global Witness. 2007. Cambodia’s Family Trees Illegal Logging and the Stripping of Public Assets by Cambodia’s Elite. Washington: Global Witness.

- Gottesman, E. 2003. Cambodia After the Khmer Rouge. Inside the Politics of Nation Building. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Press.

- Green, W.N. 2019. “From Rice Fields to Financial Assets: Valuing Land for Microfinance in Cambodia.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (4): 749–762.

- Green, N. 2021. “Placing Cambodia’s Agrarian Transition in an Emerging Chinese Food Regime.” Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (6): 1249-1292.

- Green, W.N. 2022a. “Financial Landscapes of Agrarian Change in Cambodia. Geoforum 137: 185-193.

- Green, W. N. 2022b. “Financing Agrarian Change: Geographies of Credit and Debt in the Global South.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (3): 849-869.

- Green, W. N. 2022. “Duplicitous Debtscapes: Unveiling Social Impact Investment for Microfinance.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 55 (3): 583-601.

- Green, W.N. 2023. “Financial Inclusion or Subordination? The Monetary Politics of Debt in Cambodia.” Antipode 55: 1172-1192.

- Green, W.N. and Bylander, M. 2021. “The Exclusionary Power of Microfinance: Over-indebtedness and Land Dispossession in Cambodia.” Sociology of Development 7 (2): 202–229.

- Green, W.N., and Estes, J. 2019. “Precarious Debt: Microfinance Subjects and Intergenerational Dependency in Cambodia.” Antipode 51(1): 129–147.

- Greve, H.S. 1993. Land Tenure and Property Rights in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia.

- Grimsditch, M. and Henderson, N. 2009. Untitled: Tenure Insecurity and Inequality in the Cambodian Land Sector. Bridges Across Borders Southeast Asia, Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions, Jesuit Refugee Service. Accessed December 18, 2023: https://equitablecambodia.org/website/data/dw/untitled.pdf.

- Guillou, Anne. 2006. “The Question of Land in Cambodia: Perceptions, Access, and Use since Decollectivization.” In Agriculture in Southeast Asia: An Update, edited by Marie Dufumier. Paris: EDISUD.

- Gyallay-Pap, P. 1989. “Reclaiming a Shattered Past: Education for the Displaced Khmer in Thailand.” Journal of Refugee Studies 2 (2): 257–275.

- Gyorvary, S., and Lamb, V. 2021. “From Sapphires to Cassava.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 20 (4): 431–449.

- Hall, K.R. 2011. “The Temple-based Mainland Political Economies of Angkor Cambodia and Pagan Burma ca. 889–1300.” In Kenneth Hall (editor), A history of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Hall, D. 2011. “Land Grabs, Land Control, and Southeast Asian Crop Booms.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38: 837–857.

- Hall K.R. 2018. “The Coming of the West: European Cambodian Marketplace Connectivity, 1500–1800.” In Tim Smith (editor), Cambodia and the West, 1500-2000. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Han, S. S., and Lim, Y. 2019. “Battambang City, Cambodia: From a Small Colonial Settlement to an Emerging Regional Centre.” Cities 87: 205-220.

- Helmers, K. 1997. “Rice in the Cambodian Economy: Past and Present.” In H. J. Nesbitt (editor), Rice Production in Cambodia, 1–14. Manila: International Rice Research Institute.

- Heng, K., Hamid, M. O., and Khan, A. 2023. “Research Engagement of Academics in the Global South: The Case of Cambodian Academics.” Globalization, Societies, and Education 21 (3): 322-337.

- Heuveline, P. 1998 “'Between One and Three Million': Towards the Demographic Reconstruction of a Decade of Cambodian History (1970–1979).” Population Studies 52:1: 49-65.

- Himel, J. 2007. “Khmer Rouge Irrigation Development in Cambodia.” Searching for the Truth First Quarter 42–49. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia.

- Hope, J. 2020. “The Anti-politics of Sustainable Development: Environmental Critique from Assemblage Thinking in Bolivia.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46 (1): 208–222.

- Jacobsen, T. and Stuart-Fox, M., 2013. Power and Political Culture in Cambodia. National University of Singapore: Asia Research Institute (ARI).

- Ke, S.O. and Babu, S.C. 2018. Agricultural Extension in Cambodia: An Assessment and Options for Reform. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01706. DOI: 10.2499/1024320659.

- Kem, S. 2017. “Commercialization of Smallholder Agriculture in Cambodia: Impact of the Cassava Boom on Rural Livelihoods and Agrarian Change.” Dissertation, School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland.

- Kiernan, Ben. 1996. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kiernan, Ben. 2003. “The Demography of Genocide in Southeast Asia: The Death Tolls in Cambodia, 1975-79, and East Timor, 1975-80.” Critical Asian Studies 35 (4): 585-597.

- Kiljunen, K. 1984. Kampuchea: Decade of Genocide. Report of a Finish Inquiry Commission. London: Zed Books.

- Klassen, S., Ortman, S.G., Lobo, J. et al. 2021. “Provisioning an Early City: Spatial Equilibrium in the Agricultural Economy at Angkor, Cambodia.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (1) 1-32.

- Kong, R. 2019. Landscapes and Livelihoods Changes in the North-western Uplands of Cambodia: Opportunities for Building Resilient Farming Systems. Montpellier, France: SupAgro.

- Kong, R. Diepart, J.C. Castella, J.C. Lestrelin, G. Tivet, F. Belmain, and E. Bégué. 2019. “Understanding the Drivers of Deforestation and Agricultural Transformations in the Northwestern Uplands of Cambodia.” Applied Geography 102: 84–98

- Kumi E, A. Arhin, and T. Yeboah. 2014. “Can Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals Survive Neoliberalism? A Critical Examination of the Sustainable Development–Neoliberalism Nexus in Developing Countries Environment.” Development and Sustainability 16: 539–554.

- Lamb, V., L. Schoenberger, C. Middleton, and B. Un. 2019. “Gendered Eviction, Protest and Recovery: a Feminist Political Ecology Engagement With Land Grabbing in Rural Cambodia.” In Clara Mi Young Park and Ben White (editors), Gender and Generation in Southeast Asian Agrarian Transformations. London: Routledge, 113-132.

- Leach, M., N. Nisbett, L. Cabral, J. Harris, N. Hossain, and J. Thompson 2020. “Food Politics and Development.” World Development 134: 105024.

- Leapheng, P. 2018. The Important Role of Cambodian Women in the Agriculture Sector. Phnom Penh: Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia (PIC).

- Le Billon, P. 2000. “The Political Ecology of Transition in Cambodia 1989-1999: War, Peace and Forest Exploitation.” Development and Change 31: 785–805.

- Le Billon, P. 2002. “Logging in Muddy Waters: The Politics of Forest Exploitation in Cambodia.” Critical Asian Studies 34 (4): 563–586.

- Li, T.M. 1999. “Compromising Power: Development, Culture, and Rule in Indonesia.” Cultural Anthropology 14 (3): 295–322.

- Li, T.M. 2014. “What is Land? Assembling a Resource for Global Investment.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (4): 589–602.