ABSTRACT

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an ambitious, contentious, and world-spanning project. Using Chinese Communist Party (CCP) documents, this paper examines one of the stated purposes of the BRI: to address regional inequality between China’s east and west, focusing upon Xinjiang. Through an analysis of regional economic data, the demographics of Xinjiang and Xinjiang governing bodies, and a case study of the Chinese steel industry, this paper shows that the BRI has so far failed to check increasing regional inequality in China and that job opportunities for local communities in Xinjiang are constrained by social and political factors.

Introduction

While scholars generally agree that China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, is a major factor shaping Asia’s future, there is no agreement about what exactly the BRI is or its implications for the continent. Some scholars consider the BRI the world’s largest development project, linking over seventy countries which comprise two-thirds of the world’s population and one-third of the world’s GDP.Footnote1 China has taken on high-risk loans for projects that institutions like the World Bank have refused to finance, in a manner that promises an “open and inclusive model of sustainable international economic, political and cultural cooperation and development.”Footnote2 And yet, to many critics, the BRI is simply a new “spatial fix”—a program to shift excess capital outside of eastern China, where the elite face a realization crisis.Footnote3 However generous the terms of Chinese government loans to developing countries, the result is debt.Footnote4 Today, China’s state-affiliated banks are collectively the world’s largest creditor to the Global South. Is this a sign of China’s generosity or greed? Is the BRI a symptom of the maturation of China’s capitalist society, or a sign that China has become a new type of capitalist empire?

Among scholars and analysts there is no consensus about the nature of the state in China. Nor is there general agreement about the geopolitics of a capitalist project that promises to reorganize networks of production and consumption across Asia and the world—and, in light of the instability of the US-China relationship, these geopolitics are too dynamic to interpret easily. In addition, foreign critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tend to be sceptical of the BRI’s benefits, whereas Party supporters celebrate them. Further complicating analyses of the BRI are enormous data gaps. It is difficult to assess, for example, how returns from this world-spanning project are calculated without access to internal party documents and first-hand research. Several reviewers of this paper suggested just this, and we agree; but, for political reasons, we cannot conduct fieldwork in Xinjiang today.

In what follows we evaluate the meaning and implications of the BRI in Xinjiang using three available sources: data on regional inequality, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) documents, and data on the steel industry.

BRI within China

Within the English language literature, there has been a plethora of research investigating the international political economy of the BRI. A much smaller body of literature considers these factors within China.Footnote5 This is unfortunate, because the BRI is driven in part by domestic pressures,Footnote6 and loans granted outside China are largely driven by China’s internal political economy.Footnote7

Several hub-cities of the BRI within China comprise nodes for trade along international corridors. These include Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Xi’an, Ürümqi, and Kashgar. Xi’an is the starting point of the Silk Road economic belt which links the city with Ürümqi and a node in Kazakhstan. At the center of this “new Silk Road” is the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). Xinjiang’s rich natural resources, along with its geographical position, have made it central to transport and extractive infrastructures, linking China’s eastern industrial core with Central Asia.Footnote8 The BRI aims to restore the cross-border relations and trade that long existed between Xinjiang and other Central Asian societies and extend these links to southern Asia.Footnote9 The city of Kashgar in southern Xinjiang will become a hub between China and Pakistan; the corridor between Kashgar and Gwadar Port in Pakistan is set to become a “network of railways, highways, oil and gas pipelines, as well as communication fibre optic cables” by 2030.Footnote10

A fast-growing literature considers the BRI and trade between Xinjiang and bordering Central Asian countries.Footnote11 While scholars predict rapid economic growth in Xinjiang, concerns have been raised. Rippa notes that along the China-Pakistan economic corridor, local actors in peripheral regions tend to receive few direct benefits.Footnote12 She also has written that border openings in Xinjiang have caused an increase in regulations on and limitations around trade across it.Footnote13

Zhang et al. observed that the building of the BRI corridor has affected the viability of rural communities and caution that “ethnic minorities might be facing landlessness, joblessness, income loss, and displacement induced by land requirement.”Footnote14 Clarke has argued that China’s implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang has been contradictory, as the government’s narrative of “openness” around the BRI clashes with an intensification of state repression, surveillance, and social control.Footnote15

Deepening regional economic connections also complicate the state’s goal of national integration of Xinjiang. This tension is explicitly recognized by state officials, who seek to manage it via development and repression, mediated by security. President Xi Jinping, for instance, has stated, “We should foster the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security, and create a security environment built and shared by all.”Footnote16 And at the May 2023 China-Central Asia Summit, he emphasized the need to “uphold universal security” and “jointly implement the Global Security Initiative,” linking these to the BRI.Footnote17

The Chinese government defines Xinjiang as an integral, long-standing part of Chinese territory, and claims that anti-terrorism and de-radicalization policies are needed to ensure social stability and economic development of the region.Footnote18 However, the historical relationship between the territory known today as Xinjiang and China is complex. The Kingdom of Kara-Khoja (also known as Qocho) existed from approximately 832 CE until 1132 CE, when it became a vassal state first of the Western Liao dynasty and then the Mongol Empire before being dissolved in 1335 CE. The present territory of Xinjiang was not brought into the Chinese Empire until the Qing expansion of the 1700s. This generated numerous uprisings against the Qing and later Republican China. During the decades of political instability from the collapse of the Qing in 1911 until the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, two iterations of the Eastern Turkistan Republic existed.Footnote19 The relationship between this territory and state power has long been contested and unstable.

This complicated history of the Chinese state’s relationship with Xinjiang does not square with the CCP’s narrative that its actions in Xinjiang comprise an act of “rescue.”Footnote20 The acknowledgement that Uyghurs are the indigenous inhabitants of Xinjiang (and hence outside of ‘Chinese-ness’)Footnote21 threatens the Chinese government’s authority; hence the government labeling Uyghurs (particularly those thought to be separatists) as “terrorists” and “extremists” that threaten social stability and who must therefore be policed, if not incarcerated.Footnote22 China’s state conducts intense surveillance on Xinjiang’s ethnic minority groups.Footnote23 The rapid expansion of BRI-funded connective infrastructure in Xinjiang has been coupled with intensive investment in security, surveillance infrastructure (such as street checkpoints for mobile phone inspection) and detention centers.Footnote24 These detention centers provide low-cost labor for the production of commodities like cotton goods.Footnote25 The Chinese state has punished foreign governments (through sanctions) and multinational corporations (through loss of market access) for raising concerns about this forced labor.Footnote26 Taking all this together with Rippa and Zhang et al.’s assertion that Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities are losing out from the BRI, we have a mandate to compare how the BRI is presented in official materials with its actual social and economic effects.Footnote27

By soldering the region into new networks of commodity circulation, the BRI is certain to change the political economy of Xinjiang. But the precise nature and consequences of these changes—and the extent they reflect China’s national political-economic strategy—remain highly uncertain, as little data are publicly available, particularly in foreign languages. The contribution of this paper is to advance the literature by reviewing internal CCP documents in Chinese and information from the PRC’s National Bureau of Statistics, coupled with a case study of the steel industry in Xinjiang. We show that the BRI is fashioned to incorporate Xinjiang more fully within China’s capitalist economy.Footnote28 Despite official documentation stating that Xinjiang is a main beneficiary of the BRI, the region has received comparatively modest benefits relative to firms and politically connected groups in eastern China. Since we see no counteracting forces capable of changing this pattern, the BRI, though intended to address regional spatial inequalities, is likely to exacerbate them.

Xinjiang within the BRI

Since the reform and opening movement began in 1979, the CCP’s political legitimacy has been based upon facilitating rapid economic growth. And indeed, the Chinese economy grew extremely rapidly, particularly between 1990 and 2007. Yet during the same period, China also experienced a significant increase in income and wealth inequality.Footnote29 Class inequality is problematic for a political party that claims to advance a Communist program.

Reducing China’s regional inequality is a major priority for the CCP. This is reflected in two of the “Five Big Development Concepts” (wŭdà fāzhǎn lǐniàn), “coordination” and “sharing.”Footnote30 In 2000, the government announced the “Western Development Strategy” (xībù dà kāifā zhànlüè) aimed at increasing development in areas such as Xinjiang. Since 2013, this strategy has been largely subsumed into the BRI. The State Council’s Office of Information website states that the BRI is meant to bring development opportunities to the western region in particular.Footnote31

The BRI has been the central mechanism for mitigating regional inequality in recent five-year plans. According to the thirteenth such plan (2016-2020), the government “will give high priority to implementing the strategy for the large-scale development of the western region and ensure that the [BRI drives] development in this region”Footnote32 and “we will work to develop Xinjiang as the core region for the Silk Road Economic Belt.”Footnote33 Similarly, the current fourteenth plan (2021-2025) aims in part to “actively integrate regional development into the pursuit of the Belt and Road Initiative.”Footnote34 and emphasizes the need to develop areas with concentrations of ethnic minorities, noting Hotan Prefecture, Aksu Prefecture, Kashi (Kashgar) Prefecture, and Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture in southern Xinjiang in particular.

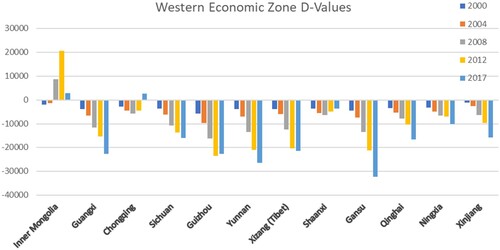

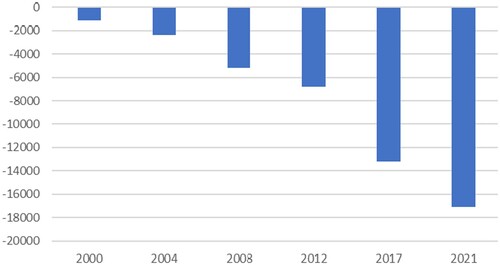

However, the BRI has not helped mitigate economic inequality between Xinjiang and eastern China. Indeed, regional economic inequality has increased ( and ).

Figure 1. D-Values of Xinjiang. D-values = (GRP per capita for a given province in a given year – the average of all provinces in China in that given year). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China.

To understand why regional inequality stubbornly persists, it is helpful to consider a particular sector or industry which is expected to contribute to growth in Xinjiang. We focus on the steel industry because steel is an essential capital good, one which is used for diverse purposes in infrastructure, construction, and consumer goods.Footnote35 Moreover, steel has held symbolic significance in China since at least the 1950s.Footnote36 In 2014, the State Council, then chaired by Premier Wen Jiabao, called the steel industry “an important fundamental industry of the national economy and an important symbol of the country’s economic and social development level and comprehensive strength.”Footnote37

Evidence from the Steel Industry

During the tumultuous 1970s, China’s political leaders came to view the task of nation-building in a literal and material sense: the construction of infrastructure and cities should be at the heart of China’s state.Footnote38 This construction orientation of the state building project later extended internationally.Footnote39 Today the Chinese government—like other industrialized capitalist states—considers steel a strategic commodity.Footnote40

Steel production increased from 28.8 million metric tons per year in 1978 to 116.6 million metric tons in 2000. Growth further accelerated after 2000 and China became a net exporter of steel in 2005. While the growth rate of the industry has slowed (in relative terms) since 2014, in 2019 China produced 996 million metric tons of crude steel—more than one-half of global crude steel production.Footnote41 In 2020, its 36 A-share iron and steel companies had a net profit of 59.817 billion RMB (US$ 8.4 billion).Footnote42

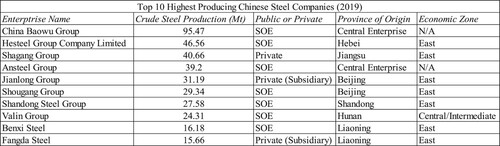

China’s Baosteel Enterprise (now China Baowu Steel Group) was created on December 23, 1978, as “the largest engineering project in China after 1949.”Footnote43 While at that time the accumulation of private capital had only just begun and individual capitalists could not form large, private steel companies, the creation of a state-owned steel enterprise (SOE) on the second day of the reform period shows the intentionality of the government to both prioritize steel-intensive infrastructure enterprises and ensure the government’s dominant hand in the industry moving forward. As seen in , the dominance of state-owned steel firms persists.

As of 2019, seven of the ten largest Chinese steel companies were state-owned enterprises; of these, two—China Baowu Steel Group and Ansteel Group—are centrally owned/national enterprises. Baowu Steel is the country’s top steel producer, with over twice the output of crude steel as the next highest producer. The Chinese government also owns substantial stakes in many of the top private steel producers, making them subject to considerable influence.Footnote44

Through the establishment of Baosteel on the second day of Deng Xiaoping’s reform, the Chinese state positioned itself as a primary beneficiary of any project that requires steel inputs. Despite the innumerable national projects that have required steel over the decades, by the 2010s Chinese steel production surpassed national demand, with a seventy-five percent utilization rate in 2012.Footnote45 This overproduction, which was due in part to generous state subsidies to steel SOEs, particularly during the 2007-2008 global economic crisis, reduced the profitability of the industry and threatened Chinese banks with loan losses.Footnote46 Rather than letting supply fall with demand as in a typical market economy, the Chinese government sought to increase external demand for steel. The BRI was one of the most important measures for increasing external demand for Chinese steel exports and therefore national economic stability.Footnote47

Since infrastructure projects require steel, the BRI contributes directly to China’s steel industry.Footnote48 Chinese materials are commonly used in all BRI infrastructure projects, stimulating a demand for China’s steel.Footnote49 Indeed, Ni et al. predicted that the Belt and Road Initiative would solve China’s steel overcapacity issue by 2020, with only an estimated thirty-two to fifty-eight million metric tons of excess steel by the end of 2020, rather than the 200 million metric tons in 2012.Footnote50 While the Coronavirus pandemic may have affected this prediction, the BRI has increased demand for steel.

As illustrates, all but one of the country’s top steel companies are wholly or partially owned by some part of the state, and all but one are based in the more prosperous eastern part of the country.Footnote51 Xinjiang has three state-owned steel enterprises, one of which (Xinjiang Bayi Iron and Steel) is a subsidiary of Baowu Steel and thus centrally owned. Xinjiang Bayi Iron and Steel was the first iron and steel plant established in Xinjiang in 1951. After General Wang Zhen announced in 1949 that Xinjiang must have its own steel plant in order for the government to build railways and encourage economic development, Shanghai’s Yihua Steelmaking Plant was moved to Xinjiang (along with its managers and skilled workers). The Ministry of Heavy Industry allocated a blast furnace, and the renamed Bayi Iron and Steel factory was officially established in 1951.Footnote52

In addition, the central government established the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Xīnjiāng shēngchǎn jiànshè, XJCC) in 1954. This organization led Xinjiang’s modernization in the following decades, including establishing large-scale industrial and mining enterprises.Footnote53 In the 1980s it was tasked by the government with combating the “Three Evil Forces” (sāngŭ shìlì) of separatism, religious extremism, and violent terrorism, along with border security and the “integration of troops and land.”Footnote54 The XJCC also ensures a permanent population of Han Chinese in Xinjiang, representing twelve percent of the population as of 2018.Footnote55

In 2007, Baowu Steel brought Bayi Iron and Steel under its banner as a subsidiary after acquiring a majority stake. In 2019, company officials announced that it would be Baowu’s industrial platform in the west, with the intention to integrate Xinjiang’s steel production capacity and take advantage of the BRI’s development opportunities.Footnote56 While Baowu’s work to integrate Xinjaing’s steel industry to create a more efficient and competitive industry chain may produce positive results for the region, it also has considerable benefits for the large centrally owned enterprise. The two other steel firms in Xinjiang are Shougang Yili Steel and Sinosteel Xinjiang. Sinosteel Xinjiang is a subsidiary of China Sinosteel Group, which Baowu Steel also owns as of 2022.

Most of the steel used in Xinjiang is produced in the east. Between the inception of the BRI in 2013 and 2019, there was no push for western steel producers (). Only two of China’s fifteen top steel producers, Baotou Steel and Liuzhou Steel, are located in the west. Founded in 1954 and 1958, respectively, they were established long before BRI.

The relative geographical competitiveness of enterprises is not the sole deciding factor when the state regulates the steel industry, particularly as the BRI has allowed local governments in central China to save loss-making SOEs with a boost in domestic financing for local infrastructure projects.Footnote57 This has been specifically true of local steelmakers, who claim the BRI has provided a “precious opportunity” to stay afloat.Footnote58

Another dimension to consider is the factional character of Chinese politics.Footnote59 Intra-provincial factions band together to compete with other groups for local power and resources, with these factions often based on native place association.Footnote60 Factions pursue policies that will provide material benefits to themselves while plausibly serving the public interest.Footnote61 The goals of these factions depend on their relative strength, with local leaders belonging to strong factions less likely to pursue policies beneficial to local development as individuals higher in the political hierarchy decide their political survival, rather than their constituents.Footnote62

While the BRI is intended to support SOEs, the interests of Xinjiang local leaders’ factions determine whether specific policies actually aid local development. However, it is notable that, of the thirteen current members of the Standing Committee of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, nine are ethnic Han; and their leader (who is also the First Secretary and First Political Commissar of the Party Committee of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps), Ma Xingrui, is a Shandong native.Footnote63 The previous leader (from 2016 to 2021), Chen Quanguo, is from Henan, and ten of the fifteen members of the committee he led were Han.Footnote64 It may be that local development in Xinjiang has not been the political priority of Xinjiang’s leaders as the BRI has taken shape. In this case, it is not surprising that native enterprises have not been given priority.

Promoting steel enterprises further west and taking advantage of existing iron deposits would be an important step in ensuring western China reaps benefits from the infrastructure project-oriented BRI. Additionally, building profitable local SOEs may ease the tax burden on rural residents, as without the profits of SOEs (or taxes paid by large private corporations), local governments will raise taxes and fees on rural farmers, known as the “peasant burden,”Footnote65 which, in the case of Xinjiang, are mostly ethnic minorities. However, the lack of western-based enterprises profiting from the BRI extends beyond resource industries; for example, the majority of construction contracts for large-scale infrastructure projects in Kashgar have been won by eastern enterprises.Footnote66 The presence of eastern and centrally-owned SOEs is also ubiquitous.

G7 Beijing-Xinjiang Expressway and SOEs

Construction of the G7 Beijing-Xinjiang Expressway provides a good example of a domestic BRI infrastructure project. The project has been called by the central government a Belt and Road Initiative “Super project.”Footnote67 It runs 2,582 kilometers and connects Beijing to Ürümqi. Construction started in 2014 and the highway opened in 2017.Footnote68 This project arguably was an opportunity for the government to boost western economic development by inviting local enterprises and workers to take part. Instead, construction was spearheaded by three central state enterprises: China State Construction, China Railway, and China Communications Construction.

The continued predominance of state-owned enterprises in Xinjiang is supported by China’s current (fourteenth) five-year plan. It calls for state-owned enterprises to be a main source of investment in Xinjiang’s economic development, including Power China, which “will actively participate in the construction, transformation, and upgrading of major projects such as the Xinjiang railway, highway, and air transportation systems.”Footnote69 Considering transportation and general infrastructure building are key factors in Xinjiang’s development model under both the BRI and the state’s Five-Year Plans, SOEs will continue to dominate the BRI in Xinjiang.Footnote70

Party members must be atheistic; this discriminates against Uyghurs that practice Islam. Uyghurs within the Party are held to exacting standards and have been harshly criticized. Yusuf Aisha, a Uyghur and former Vice Chairman of the CPPCC of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, has stated, “At present, among some Uyghur party members and cadres, there are problems such as lack of firm ideals and beliefs, weakened sense of purpose, and weak party consciousness … [Uyghur party members] play a special role in the reunification of the motherland, national unity and social stability.”Footnote71 Like all Party members, they must also demonstrate loyalty to the Party. This becomes complicated when their people are discriminated against by the government.

Like large and powerful local governments, large SOEs have more power to resist mandates by the CCP, but these SOEs ultimately end up less competitive internationally and less profitable.Footnote72 Given that SOEs are beneficiaries of BRI projects, members of minority groups that do not fall in line with Party standards are unlikely to benefit from employment or salaries that BRI projects may bring. They may even lose government positions during initiatives which are supposed to help them, as has been the case with Tibet.Footnote73

Social and Political Factors

Hu Chunhua and Tibet

The BRI was preceded by the Western Development Strategy, which targeted the Tibetan Autonomous region (TAR). One current leader of BRI implementation previously was posted in Tibet, Hu Chunhua, a member of the National Leading Group for Promoting the Construction of One Belt and One Road (guójiā tuījìn yīdài yīlù jiànshè gōngzuò lǐngdǎo xiǎozŭ), the coordinating body of the BRI within the State Council. Hu has worked in Hebei, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia over his career. In his first fourteen-year tenure in Tibet (1983-1997), he was secretary of the Communist Youth League Tibet Autonomous Region Committee and commissioner of Lizhi and Shannan districts. He returned to Tibet for five years in 2001 as a member of the Standing Committee and Secretary-General of the CCP Tibet Autonomous Region Party Committee.

During his second stint in Tibet, Hu played a role in implementing the Western Development Strategy. The projects that resulted were largely capital-intensive infrastructure projects, including a railway connecting the region to inner China via Qinghai. Finished in 2006, this line was advertised as a method to stimulate Tibet’s economy through tourism and mining. However, many native Tibetans saw it as a means to encourage migration of Han Chinese into the region.Footnote74 In this way, the Qinghai-Tibet Railway continued the tradition of attracting entrepreneurs from outside the region through the promise of economic opportunities.Footnote75

Hu Chunhua’s tenure in Tibet saw a large-scale infrastructure project that encouraged the migration of Han Chinese into Tibet, with subsidies from the central government encouraging Han migration, although they remain a small portion of the Tibetan populace,Footnote76 while native Tibetan representation in local CCP cadres sharply declined. We are not suggesting that these results reflect Hu Chunhua’s choices; a large infrastructure project would have to be approved by the Chinese central authority. Such projects also continue the “Red Engineers” legacy.Footnote77 It would be reasonable to consider if similar patterns will be repeated in the implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang.

Demographics

The lack of representation of ethnic Tibetans in decision-making positions in the TAR during the implementation of the Great Western Development is also reflected in the BRI. Across Central Asia, multilateral decision-making, inclusive of local governments, has been largely absent in BRI projects,Footnote78 likely reflecting its implementation within China. Those in charge of implementing the BRI within Xinjiang are members of the Standing Committee of the Party Committee of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, of whom the majority are Han Chinese.Footnote79

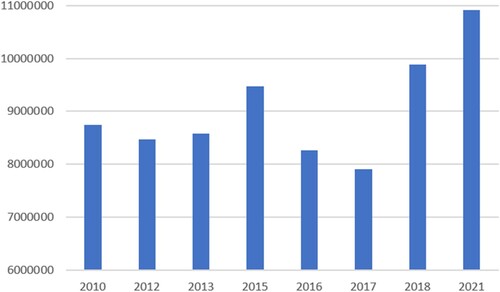

According to the 2021 National Census, the Uyghur population in Xinjiang increased by 1.62 million between 2010 to 2021, from 11,624,257 to 13,247,257 (fourteen percent).Footnote80 During this period the Han population increased by 2.17 million, to 10,920,098 (a 19.9 percent increase).Footnote81 Of the Han increase, 1.95 million came from in-migration from other provinces. This follows the trend in the TAR, where a large development initiative resulted in an increase of in-migration of Han Chinese seeking economic opportunities.Footnote82

shows that the Han Chinese population trended upward during the BRI’s implementation. ∼90% of this increase in Han Chinese population is caused by inter-regional migration. This suggests that many jobs and opportunities generated by the BRI in Xinjiang flow to non-local Han Chinese. Additionally, employment given to Uyghurs in construction or manufacturing jobsFootnote83 may be the result of forced labor from relocated detainees from “re-education” camps.Footnote84 While it cannot be said with certainty that the majority of Han migrants come to Xinjiang for employment that falls within the scope of the BRI, the influx of Han Chinese into Xinjiang coincides with the development of the BRI as well as the mass surveillance and incarceration of Xinjiang natives.

Conclusion

The Government of China would like to reduce regional inequality and seeks to use the BRI to do so in Xinjing. Yet three elements suggest that, at least to this point, the BRI has failed to check regional inequality. First is the increasing gap in per-capita GRP (gross regional product) between Xinjiang and the average per-capita GRP of Chinese provinces.Footnote85 Second is the continued dominance of eastern SOE firms in the steel industry specifically and BRI projects generally. Third is an increase in non-local Han Chinese migrants and a relative lack of BRI-related job opportunities for Xinjiang natives.

Geopolitics is likely a factor limiting the effectiveness of the BRI in reducing regional inequality. As state-building in Xinjiang is one of the central motivators of the BRI, a focus on security has contributed to economic inefficiencies.Footnote86 Those who were already integrated into formal systems were able to take advantage of large-scale development projects; those who were not—particularly Uyghurs—experienced loss of space, land, and resources, contributing to their economic exclusion.Footnote87

However, this may underestimate the economic benefits of the BRI, such as opening new markets to Chinese industries (including steel) and allowing them to continue operating at a surplus.Footnote88 It is possible that Xinjiang may see more benefits from the BRI in the future and even begin to close the gap between it and China’s eastern provinces. However, to date, the evidence shows that regional inequality has increased.

Our analysis lends credence to the interpretation of the BRI as a spatial fix. A spatial fix is meant to address the overaccumulation of capital at the economic center (in this case, China’s industrial production zone in the eastern region) via geographical expansion and opening new markets. As David Harvey notes, transportation innovation is a key feature of a spatial fix, required to facilitate geographical expansion (and soak up surplus investment capital).Footnote89 The core of the BRI is formed by transportation and infrastructure projects (e.g., the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the G7 Beijing-Xinjiang Expressway “super project”). While infrastructure may facilitate development, Xinjiang has not seen gains in regional equality since the onset of construction of these transportation corridors. The economies of eastern provinces have continued to grow faster than those of the western region; inter-provincial SOEs and Han Chinese migrants have found opportunities in these areas where local residents have not. While official Party literature states the BRI is an even-growth initiative, the results of its implementation show the hallmarks of a spatial fix.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Padraig Carmody, Will Jones, Seung-Ook Lee, Morgan Liu, Max Woodworth, Emily Yeh, and our anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Justine Franklin

Justine Franklin has an MA from the Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics Department and the East Asian Studies Center at Ohio State University, where she studied China and political economy.

Joel Wainwright

Joel Wainwright is a Professor of Geography at Ohio State University, where he studies political economy, environmental change, and social theory. He is the author of Decolonizing Development: Colonial Power and the Maya (Wiley, 2008), Geopiracy: Oaxaca, Militant Empiricism, and Geographical Thought (Palgrave Pilot, 2012) and, with Geoff Mann, Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of our Planetary Future (Verso, 2020).

Notes

1 World Bank Citation2018.

2 Dunford and Liu Citation2019, 145.

3 Cf. Carmody and Wainwright Citation2022; Carmody et al. Citation2022; Zhang Citation2017. Harvey (Citation2001) defines a spatial fix as capitalism’s strategy to resolve a crisis of overaccumulation (where a surplus of capital leads to devaluation and unprofitability) by geographical expansion and restructuring. His earlier work (Harvey Citation1981) identifies colonialism as a spatial fix through the lens of Hegel and von Thünen, but the underlying theory is derived from Marx and Luxemburg.

4 Cf. Carmody et al. Citation2022; Zeeshan et al. Citation2021; van Twillert Citation2023. Since the BRI is principally comprised of infrastructure projects, the inability to repay debt can lead to China owning or otherwise controlling critical infrastructure in other countries. A much-disputed case is Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port: for a review of the literature, see Kamburawala and Abeyrathne (Citation2022).

5 The literature in Chinese is more balanced, but tilts toward empirical, pro-BRI studies.

6 Carmody and Wainwright Citation2022; Ghulam Citation2022; Garcia and Guerreiro Citation2024.

7 Zhang et al. Citation2018; Clarke Citation2020; van Twillert and Halleck Vega Citation2023; Mostafanezhad et al. Citation2023.

8 Rippa and Carson Citation2023.

9 Rippa Citation2020.

10 Hayes Citation2020.

11 Cf. Clarke Citation2018; Caskey and Murtazashvili Citation2022; Ghulam Citation2022; Wang Citation2023.

12 Rippa Citation2020.

13 Rippa Citation2019. She describes how Pakistani traders in Xinjiang face increased scrutiny, their businesses regularly visited by local police.

14 Zhang et al. Citation2018.

15 Clarke Citation2018.

16 Xi Citation2017.

17 CGTN Citation2023. Central Asian countries defer to China on the matter of Xinjiang: Primiano Citation2023.

18 The State Council Information Office 2019. This is not limited to Xinjiang. As Hung (Citation2023) notes, “In official policy speeches, ‘security’ has become the most frequently uttered word, eclipsing ‘economy.’”

19 See Starr 2005 and Friedrichs Citation2017 for a history of the Tarim Basin (now known as Xinjiang) area and Sino-Uyghur relations.

20 Byler Citation2022.

21 The majority of Uyghurs identify as Turkic Muslims.

22 Ibid.

23 Leibold Citation2020; Byler Citation2022.

24 Rippa and Carson Citation2023.

25 Byler, 2023.

26 Schaefer and Hauge Citation2023.

27 Rippa Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2018.

28 Karl 2020; Andreas Citation2009; Li 2009 for China as a capitalist economy; O'Brien and Primiano Citation2020 on Xinjiang in BRI. Additionally, Branko Milanovic in his 2019 book Capitalism, Alone defines China’s economic system as “Political Capitalism,” where a highly technocratic political elite must ensure high economic growth rates to maintain legitimacy while grappling with a discretionary system that allows members to seek personal gain which causes inequality-increasing corruption.

29 Xie & Zhou Citation2014. The Gini coefficient increased from 32.5 in 1993 to 46.5 in 2016. See Chen Citation2020.

30 These five concepts are innovation (创新), coordination (协调), greenness (绿色), openness (开放), and sharing (共享).

31 Qi Citation2015.

32 Compilation and Translation Bureau Citation2016.

33 Compilation and Translation Bureau Citation2016.

34 The People’s Government of Fujian Province Citation2021.

35 Wu Citation2000.

36 Wu Citation2000. And as one reviewer, Dr. Robert Shepherd, acutely noted, the [Steel] Production and Conservation Corps was a sort of forerunner to the BRI in Xinjiang.

37 钢铁产业是国民经济的重要基础产业,是国家经济和社会发展水平、综合实力的重要标志 ; the Central Government of the People’s Republic of China Citation2014.

38 Andreas Citation2009.

39 On the international, territorial character of BRI, cf. Akhter 2018, Lee et al. 2018.

40 Bluhm et al. Citation2018.

41 Worldsteel 2020.

42 Zhao and Ren Citation2021. “A-shares” are those of mainland China-based companies that trade on the two Chinese stock exchanges, the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE).

43 Dong et al. Citation2019. Baosteel Enterprise merged with another SOE, Wuhan Iron and Steel, in 2016 to form China Baowu Steel Group.

44 Price et al. Citation2007.

45 Zhang Citation2012; cf. Ni et al Citation2021.

46 The banking sector is heavily influences by the state, where loans in the formal banking system largely serve public enterprises rather than private companies (Tsai Citation2015).

47 Ni et al. Citation2021.

48 Constructsteel Citation2022.

49 Jamali et al. 2023

50 Ni et al. Citation2021.

51 Valin Group, the one non-eastern steel enterprise, is based in Hunan, in central China. None of China’s top ten steel producers are based in or associated with western China.

52 Metallurgical Information Equipment Network Citation2023.

53 The State Council Information Office 2014.

54 Tiemengguan 2022.

55 Bao Citation2018. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corp still exists, with Xi Jinping emphasizing its role in maintaining stability in the region to ensure the success of the BRI.

56 Chen et al. Citation2022.

57 Lauridsen posits that BRI infrastructure initiatives allow for the internationalization of relevant state-owned enterprises along with the expansion of economic interests: Lauridsen Citation2020.

58 Ye Citation2019.

59 Nathan Citation1973; Dittmer and Wu Citation1995; Hillman Citation2010; Ho Citation2012; Fang et al. Citation2019.

60 Hillman Citation2010. As one reviewer noted: since “different factions in the CCP are linked to control of different industries, … part of the BRI process is about allocating contracts to SOEs in the context of this factional reality.” We thank the reviewer for emphasizing this point.

61 Dittmer and Wu 1995

62 Fang et al. Citation2019.

63 The State Council of the People’s Republic of China Citation2021.

64 The People’s Government of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China Citation2021; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2017. It is reported that under Ma Xingrui’s leadership suppression of Uyghurs has eased in comparison to when Chen Quanguo was in charge, although Ma has continued his predecessor’s “anti-terrorism” policies. There is speculation that Chen Quanguo was removed due to criticism from the international community, but no Party censure has occurred (See Kumakura 2023).

65 Hillman Citation2010.

66 Steenberg and Rippa Citation2019.

67 The Central Government of the People’s Republic of China, 2017.

68 Ma 2021.

69 Dan 2021.

70 Xilong 2019; Dan 2021. SOE employees do not necessarily need to be party members, but all managerial and executive positions in SOEs are held by party members (see Wang Citation2022).

71 Xinjiang Morning News Citation2017.

72 Van Aken and Lewis Citation2015.

73 Fischer Citation2005.

74 Hoh Citation2005. Simultaneous to the construction of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway was a sharp reduction in Tibetan representation in public employment, from seventy percent in 2002 to just below fifty percent in 2003 (Fischer Citation2005). Critics claim that the Chinese government uses the immigration of Han Chinese into ethnic regions to assert control in places like Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. Cf. Tsering Citation2017.

75 Barnett Citation1998.

76 Fischer Citation2021. Between the 2010-2020, the Han Chinese population in Tibet rose 6.1% compared to Tibetan’s 1.9%, but Han Chinese still only represent 12% of the population. On migration to Tibet, see Yeh (Citation2019).

77 On red engineers, see Andreas Citation2009. For instance, in addition to leadership within BRI governing bodies, Peng and Callais (2021) show that the party secretary of XUAR between 2016-2021 (and party secretary of Tibet 2011-2015), Chen Quanguo (陈全国)—Henan native, Han Chinese, Wuhan University of Technology alum with a major in management science and engineering (Xinhua News Agency 2017)—enacted policies meant to increase both income and social coercion, but only managed to accomplish the latter.

78 Yu Citation2023.

79 Gao Citation2023; Xinhua News Citation2023. One of the current deputy secretaries, Erken Tuniyaz, is Uyghur, as is the vice-chairman of the People’s Government of the Autonomous Region, Yusu Fujiang Maimeti.

80 The Statistics Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region lists this as a 16.2 percent increase; however, calculating the increase with the population numbers shows a fourteen percent increase.

81 Statistics Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Citation2021.

82 Fischer Citation2021.

83 One of the core development ideals of the Silk Road Economic Belt in the Urumqi International Land Port is “gathering goods, building [industrial] parks, and gathering industries” (集货、建园、聚产业). See Xinjiang Daily Citation2023. While it cannot be said every manufacturer in Xinjiang is part of the BRI, even in government documents what constitutes a BRI project and which companies participate in the BRI is vague at best.

84 Hoshur Citation2020; Niyaz Citation2024.

85 While regional inequality has increased, Xinjiang’s GRP roughly doubled between 2012 and 2022.

86 Clarke Citation2020.

87 Roberts Citation2018; Steenberg and Rippa Citation2019.

88 Lai Citation2021.

89 Harvey Citation2001.

References

- Akhter, Majed. 2018. “Geopolitics of the Belt and Road: Space, State, and Capital in China and Pakistan.” In Logistical Asia: The Labour of Making a World Region, 221–241. London: Springer.

- Andreas, Joel. 2009. Rise of the Red Engineers: The Cultural Revolution and the Origins of China’s New Class. Stanford University.

- Baidu Encyclopedia. 八一钢铁 [Bayi Steel]. Accessed April 29, 2024: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%85%AB%E4%B8%80%E9%92%A2%E9%93%81/6856111.

- Bao, Yajun. 2018. “The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps: an Insider’s Perspective.” Blavatnik School of Government, February 2. Accessed January11, 2024: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/blog/xinjiang-production-and-construction-corps-insiders-perspective.

- Barnett, Robert. 1998. “The Tibetans.” Info-Buddhism.com. Accessed June 8, 2021: https://info-buddhism.com/the_tibetans_robert_barnett.html.

- Bluhm, Richard, Axel Dreher, Andreas Fuchs, Bradley Parks, Austin Strange, and Michael Tierney. 2018. “Connective Financing: Chinese Infrastructure Projects and the Diffusion of Economic Activity in Developing Countries.” AidData Working Paper #103. Accessed September 28, 2023: https://www.aiddata.org/publications/connective-financing-chinese-infrastructure-projects-and-the-diffusion-of-economic-activity-in-developing-countries.

- Byler, Darren. 2022. Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Byler, Darren. 2023. “The Camp Fix: Infrastructural Power and the “Re-education Labour Regime” in Turkic Muslim Industrial Parks in North-west China.” The China Quarterly 255: 628–643. doi: 10.1017/S0305741022001618

- Carmody, Pádraig, Ian Taylor, and Tim Zajontz. 2022. “China’s spatial fix and ‘debt diplomacy’ in Africa: Constraining belt or road to economic transformation?” Canadian Journal of African Studies 56 (1): 57-77.

- Carmody, Pádraig, and Joel Wainwright. 2022. “Contradiction and restructuring in the Belt and Road Initiative: Reflections on China’s pause in the ‘Go world’.” Third World Quarterly 43 (12): 2830-2851. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2022.2110058

- Caskey, W. Gregory, and Ilia Murtazashvili. 2022. “The predatory state and coercive assimilation: The case of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.” Public Choice 191 (1-2): 217-235. doi: 10.1007/s11127-022-00963-9

- CGTN. 2023. “Highlights of Xi Jinping's keynote address at China-Central Asia Summit.” CGTN, May 19. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2023-05-19/Xi-delivers-keynote-address-at-China-Central-Asia-Summit-1jVs79VdHLG/index.html.

- Chai, C.H. Joseph. 1996. “Divergent development and regional income gap in China.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 26 (1): 46-58. doi: 10.1080/00472339680000041

- Chen, Ruo-lan. 2020. “Trends in Economic Inequality and Its Impact on Chinese Nationalism.” Journal Of Contemporary China 29 (121): 75-91. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1621531

- Chen, Xilong. 2019. “一带一路”背景下新疆经济发展现状与机遇探究.” [Research on the current situation and opportunities of Xinjiang's economic development under the background of “One Belt and One Road”.] China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-0968.2019.10.001.

- Chen, Yuqian, Zhuo Chen, Linhai Jia, Bing Lü, Jiajun Liu, Lin Lü. 2022. “金色八钢的边陲使命” [The Border Mission of Golden Bayi Steel]. China Metallurgical News, January 17. Accessed January 10, 2024: http://www.csteelnews.com/xwzx/djbd/202201/t20220117_58751.html.

- Clarke, Michael. 2018. “The Belt and Road Initiative: Exploring Beijing’s Motivations and Challenges for its New Silk Road.” Strategic Analysis 42 (2): 84-102. doi: 10.1080/09700161.2018.1439326

- Clarke, Michael. 2020. “Beijing’s Pivot West: The Convergence of Innenpolitik and Aussenpolitik on China’s ‘Belt and Road’?” Journal Of Contemporary China 29 (123): 336-353. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1645485

- Compilation and Translation Bureau. 2016. “The 13th Five-Year-Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China.” National Development and Reform Commission. Accessed August 15, 2023: https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202105/P020210527785800103339.pdf.

- Constructsteel. 2022. “Steel is the backbone of vital infrastructure.” Constructsteel. Accessed August 7, 2022: https://constructsteel.org/projects/why-steel-in-infrastructure/.

- Dittmer, Lowell. and Wu, Yu-Shan. 1995. “The Modernization of Factionalism in Chinese Politics.” World Politics 47 (4): 467-494. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100015185

- Dong, Hongbaio, Yang Liu, Lijun Wang, Xinchuang Li, Zhiling Tian, Yinxin Huang, and Chris McDonald. 2019. “Roadmap of China steel industry in the past 70 years.” Ironmaking & Steelmaking 46 (10): 922–927. doi: 10.1080/03019233.2019.1692888

- Dreher, Axel, Andreas Fuchs, Bradley Parks, Austin M. Strange, and Michael J. Tierney. 2018. “Apples and Dragon Fruits: The Determinants of Aid and Other Forms of State Financing from China to Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 62: 182–194. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqx052

- Dunford, Michael, and Weidong Liu. 2019. “Chinese perspectives on the Belt and Road Initiative.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 12 (1): 145-167.

- Fang, Hanming, Linke Hou, Mingxing Liu, Lixin Colin Xu, and Pengfei Zhang. 2019. “Factions, local accountability, and long-term development: Theory and evidence.” Accessed January 17, 2024: http://www.nber.org/papers/w25901.

- Fischer, Andrew. 2005. State Growth and Social Exclusion in Tibet: Challenges of Recent Economic Growth. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press.

- Fischer, Andrew. 2021. “Han Chinese population shares in Tibet: Early insights from the 2020 census of China”. N-IUSSP, September 20. Accessed May 31, 2024: https://www.niussp.org/migration-and-foreigners/han-chinese-population-shares-in-tibet-early-insights-from-the-2020-census-of-china/.

- Friedrichs, Jörg. 2017. “Sino-Muslim Relations: The Han, the Hui, and the Uyghurs.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 37 (1): 55-79. doi: 10.1080/13602004.2017.1294373

- Gao, Yuyang. 2023. “总统来华出席重要活动后,专程到新疆与马兴瑞再次会面” [“After the president came to China to attend important events, he made a special trip to Xinjiang to meet with Ma Xingrui again.”] Beijing Youth Newspaper and Political Information, October 20. Accessed May 1, 2024: https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20231020A0AWQE00.

- Garcia, Zenel, and Phillip Guerreiro. 2024. “What American policymakers misunderstand about the Belt and Road Initiative.” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 54 (2): 7-19.

- Gerstel, Dylan. 2018. “It’s a (Debt) Trap! Managing China-IMF Cooperation Across the Belt and Road.” New Perspectives in Foreign Policy 16: 11-16.

- Ghulam, Ali. 2022. “Domestic Factors Behind China’s Megaprojects.” Critical Sociology 49 (2): 351-358.

- Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2014. “国务院总理温家宝4月20日主持召开国务院常务会议,审议并原则通过《钢铁产业发展政策》” [Premier Wen Jiabao chaired an executive meeting of the State Council on April 20 to review and adopt in principle the “Steel Industry Development Policy”], April 20. Accessed January 15, 2024: https://www.gov.cn/gjjg/2005-08/16/content_23749.htm.

- Harvey, David. 1981. “The spatial fix: Hegel, Von Thunen, and Marx.” Antipode 13 (3): 1-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1981.tb00312.x

- Harvey, David. 2001. “Globalization and the ‘spatial fix’.” Geographische revue: Zeitschrift für Literatur und Diskussion 3 (2): 23-30.

- Hayes, Anna. 2020. “Interwoven ‘Destinies’: The significance of Xinjiang to the China dream, the belt and road initiative, and the Xi Jinping Legacy.” Journal of Contemporary China 29 (121): 31-45. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1621528

- Hielscher, Lisa. 2019. “China’s Overseas Investment Insurance – Sinosure.” Belt and Road Initiative, May 26. Accessed January 15, 2020: https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/tag/sinosure/.

- Hillman, Ben. 2010. “Factions and spoils: Examining political behavior within the local state in China.” The China Journal 64: 1-18. doi: 10.1086/tcj.64.20749244

- Ho, Wing-Chung. 2012. “The rise of the bureaucratic bourgeoisie and factional politics of China.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 42 (3): 514-521. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2012.687635

- Hoh, Erling. 2005. “Train heads for Tibet, carrying fears of change.” SFGate, February 24. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Train-heads-for-Tibet-carrying-fears-of-change-2727764.php.

- Hoshur, Shohret. 2020. “Majority of 19,000 People to be Placed in Jobs are Xinjiang Camp Detainees.” Radio Free Asia, August 20. Accessed June 1, 2024: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/jobs-08202020170719.html.

- Hung, Ho-Fung. 2023. “Zombie Economy.” New Left Review, August 4. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/zombie-economy.

- Iron and Steel Academy. 2024. “中国565家钢铁企业名单大全!” [A complete list of 565 steel companies in China!]. Micro-channel public platform, January 5.

- Jamali, B. Ahmed, Stephen Westcott, and Abhishek Verma. 2023. “Belt and Road Initiative: The Intertwining of China’s Foreign Policy and Economic Nationalism.” East Asia 1: 25-40. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-023-09415-7.

- Jiang, Dan. 2021. “助力新疆经济发展央企勾勒“十四五”投资蓝图” [Helping central enterprises in Xinjiang’s economic development outline the “14th Five-Year Plan” investment blueprint]. Securities Times, September 11. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1710531963187139184&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Kamburawala, Tharindu Udayanga, and Dilmini Hasintha Abeyrathne. 2022. “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Sri Lanka: A Review of Literature.” KDU Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2): 56-65. doi: 10.4038/kjms.v4i2.51

- Kamakura, Jun. 2023. “What Is Behind the Recent Changes in the Political Elites of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region?” Institute of Developing Economies. Accessed April 30, 2024: https://www.ide.go.jp/English/ResearchColumns/Columns/2023/kumakura_jun.html.

- Krpec, Oldrich, and Carol Wise. 2022. “Grand Development Strategy or Simply Grandiose? China's Diffusion of Its Belt & Road Initiative into Central Europe.” New Political Economy 27 (6): 972-988. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2021.1961218

- Lauridsen, S. Laurids. 2020. “Drivers of China’s Regional Infrastructure Diplomacy: The Case of the Sino-Thai Railway Project.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (3): 380-406. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1603318

- Lai, Hongyi. 2021. “The Rationale and Effects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Reducing Vulnerabilities in Domestic Political Economy.” Journal of Contemporary China 30 (128): 330-347. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2020.1790896

- Lardy, Nicholas. 2016. “The Changing Role of the Private Sector in China.” Reserve Bank of Australia. Accessed April 29, 2024: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/confs/2016/lardy.html.

- Lee, Seung-Ook, Joel Wainwright, and Jim Glassman. 2018. “Geopolitical Economy and the Production of Territory: The Case of US–China Geopolitical-Economic Competition in Asia.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50 (2): 416–436. doi: 10.1177/0308518X17701727

- Leibold, James. 2020. “Surveillance in China’s Xinjiang region: Ethnic sorting, coercion, and inducement.” Journal of Contemporary China 29 (121): 46-60. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1621529

- Liu, Yiran. 2020. “People’s will or the central government’s plan? The shape of contemporary Chinese local governance.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 20 (2): 226-242. doi: 10.1080/24761028.2020.1744290

- Marais, Hannah, and Jean-Pierre Labuschagne. 2019. “China’s Role in African Infrastructure and Capital Projects.” Deloitte, March 22. Accessed August 18, 2022: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/china-investment-africa-infrastructure-development.html.

- Meng, Jingwei, 2021. “北京市第七次全国人口普查主要数据情况” [Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census of Beijing]. The People’s Government of Beijing Municipality, May 19. Accessed May 2, 2023: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/shuju/sjjd/202105/t20210519_2392877.html.

- Metallurgical Information Equipment Network, 2023. “八一钢铁厂——新疆第一座钢铁厂” [Bayi Iron and Steel Plant — the first steel plant in Xinjiang]. Micro-channel public platform, July 31. Accessed January 10, 2024: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA3Mjk1OTM1NA==&mid=2655060415&idx=4&sn=54a91aee6d7b57e17807b4ee455b4770&chksm=84a3f5aab3d47cbcf4891ccfbbeb6e00d586baf44aa135119d7eb6be19f6cbb70acc9afaa210&scene=27.

- Mlambo, Courage, 2022. “China in Africa: An Examination of the Impact of China’s Loans on Growth in Selected African States.” Economies 10 (7): 154. doi: 10.3390/economies10070154

- Mostafanezhad, Mary, Robert A. Farnan, and Shona Loong. 2023. “Sovereign anxiety in Myanmar: An emotional geopolitics of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 48 (1): 132-148. doi: 10.1111/tran.12571

- Nathan, J. Andrew. 1973. “A Factionalism Model for CCP Politics.” The China Quarterly 53 (January-March): 34-66. doi: 10.1017/S0305741000500022

- National Development and Reform Commission, Government of China. 2019. “国家发展改革委一带一路建设促进中心组织召开共建“一带一路”系列座谈会.” [The Belt and Road Construction Promotion Centre of the National Development and Reform Commission organized a series of symposiums on the joint construction of the Belt and Road], January 24. Accessed June 25, 2021: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-01/24/content_5360859.htm.

- National Development and Reform Commission, Government of China. 2020. “国家发展改革委一带一路建设促进中心.” [Belt and Road Construction Promotion Centre of National Development and Reform Commission], May 21. Accessed June 25, 2021: http://dzsws.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/mingdan/202005/20200502967154.shtml.

- National Development and Reform Commission, Government of China, Department of Personnel. 2021. 国家发展和改革委员会一带一路建设促进中心2021年公开招聘公告 [National Development and Reform Commission Belt and Road Construction Promotion Centre 2021 Open Recruitment Announcement]. Accessed June 20, 2021: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/ztzl/2021ndrczp/sydwzp/202104/t20210413_1272174.html?code=&state=123.

- Neuwirth, J. Rostam. 2019. “China and the “culture and trade” debate: A holistic approach.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 25 (5): 629-647. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2019.1626846

- Ni, Zhongxin, Xing Lu, and Wenjun Xue. 2021. “Does the belt and road initiative resolve the steel overcapacity in China? Evidence from a dynamic model averaging approach.” Empirical Economics 61: 279–307. doi: 10.1007/s00181-020-01861-z

- Niyaz, Kurban. 2024. “China says 456,000 Uyghurs newly hired this year in Xinjiang.” Radio Free Asia, January 2. Accessed June 1, 2024: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/uyghur-workforce-01022024154040.html.

- O’Brien, David, and Christopher Primiano. 2020. “Opportunities and risks along the New Silk Road: perspectives and perceptions on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.” In International Flows in the Belt and Road Initiative Context: Business, People, History and Geography, edited by David O'Brien, Faith Ka Shun Chan, and Hing Kai Chan, 127–145. London: Springer.

- Peng, Linan, and Justin T. Callais. 2023. “The authoritarian trade-off: A synthetic control analysis of development and social coercion in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.” Contemporary Economic Policy 41: 370–387. doi: 10.1111/coep.12597

- Price, H. Alan, Timothy C. Brightbill, Christopher B. Weld, and D. Scott Nance. 2007. “Government Ownership and Control of China’s “Private” Steel Producers.” Wiley Rein LLC, October 31. Accessed October 1, 2023: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=806b748a-5820-4607-9ffe-fb3ab9adb09f.

- Primiano, B. Christopher. 2023. “The dragon in central Asia: Is China’s increased economic involvement resulting in security gains?” Asian Security 19 (3): 228-248. doi: 10.1080/14799855.2023.2246390

- Punyaratabandhu, Piratorn, and Jiranuwat Swaspitchayaskun. 2018. “The Political Economy of China–Thailand Development Under the One Belt One Road Initiative: Challenges and Opportunities.” The Chinese Economy 51: 333-341. doi: 10.1080/10971475.2018.1457326

- Qi, Wei. 2015. “目光向西——中国的“一带一路”战略.” [Eyes Westward - China's “Belt and Road” Strategy.] State Council Office of Information, March 17. Accessed August 18, 2021: http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/wh/slxy/31200/Document/1396605/1396605.htm.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2023. “Infrastructure Development in Xinjiang.” Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. Accessed June 14, 2024: https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-729.

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2020. “Mapping the margins of China’s global ambitions: economic corridors, Silk Roads, and the end of proximity in the borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 55-76. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2020.1717363

- Rippa, Alessandro. 2019. “Cross-Border Trade and “the Market” between Xinjiang (China) and Pakistan.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (2): 254-271. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2018.1540721

- Roberts, R. Sean. 2018. “The biopolitics of China’s “war on terror” and the exclusion of the Uyghurs.” Critical Asian Studies 50 (2): 232-258. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2018.1454111

- Schaefer, Sonja, and Jostein Hauge. 2023. “The muddled governance of state-imposed forced labour: multinational corporations, states, and cotton from China and Uzbekistan.” New Political Economy 28 (5): 799-817. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2023.2184470

- Schweller, Randall. 2014. “China’s Aspirations and the Clash of Nationalisms in East Asia: A Neoclassical Realist Examination.” International Journal of Korean Unification Studies 23 (2): 1-40.

- Singh, Ajit. 2021. “The myth of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ and realities of Chinese development finance.” Third World Quarterly 42 (2): 239-253. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2020.1807318

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2021. “马兴瑞同志简历” [Resume of Comrade Ma Xingrui]. Accessed April 30, 2024: https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2022-10/23/content_5721026.htm.

- State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2017. “三央企打造“超级工程”—G7京新高速公路全线通车.” [Three central enterprises create a “super project” - the G7 Beijing-Xinjiang Expressway is fully opened to traffic.] July 16. Accessed May 22, 2023: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-07/16/content_5210889.htm.

- Statistics Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. 2021. “新疆维吾尔自治区第七次全国人口普查主要数据.” [Main data of the seventh national census of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.] Statistics Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, June 15. Accessed May 2, 2023: http://sthjt.xinjiang.gov.cn/xjepd/xwzxzhxx/202106/1a19a164fc884e9f9cf176430ee92e40.shtml.

- Steenburg, Rune, and Alessandro Rippa. 2019. “Development for all? State schemes, security, and marginalization in Kashgar, Xinjiang.” Critical Asian Studies 51 (2): 274-295. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2019.1575758

- People’s Government of Fujian Province. 2021. “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China,” August 9. Accessed August 15, 2023: https://www.fujian.gov.cn/english/news/202108/t20210809_5665713.htm#C4.

- People’s Government of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. 2021. “中国共产党新疆维吾尔自治区第十届委员会常务委员会委员” [Member of the Standing Committee of the 10th Committee of the Communist Party of China Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region]. Tianshan, October 26. Accessed January 16, 2024: https://www.xinjiang.gov.cn/xinjiang/xjyw/202110/619ae6d0e201476eb2a5a444666c5643.shtml?eqid=c33ffb28000d43100000000364869ce2.

- Tiemenguan Online. 2022. “非凡十年·师市巡礼丨石榴花开兵地间” [Extraordinary Ten Years·Visiting the Division and City丨Pomegranate Flowers Blooming on the Military Ground], September 9. Accessed January 10, 2024: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzAwNzAwMzgyNQ==&mid=2649890650&idx=3&sn=46323b3df05809ebb610ce334c9aa49e&chksm=83027484b475fd926ee364b045616121d704f7bddd6d75f19c99482d45516fb227d2d5fed0b9&scene=27.

- Tsai, S. Kellee. 2015. “The Political Economy of State Capitalism and Shadow Banking in China.” Issues & Studies 51 (1): 55-97.

- Tsering, Dolma. 2017. “Contesting Sovereignty: Tibet-China Conflict, Revisiting Dawa Norbu’s Work on China’s Tibet Policy.” Tibet Journal 42 (2): 17-25.

- Van Aken, Tucker, and Orion A. Lewis. 2015. “The Political Economy of Noncompliance in China: the case of industrial energy policy.” Journal of Contemporary China 24 (95): 798-822. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2015.1013374

- Van Twillert, Nienke, and Solmaria Halleck Vega. 2023. “Risk or opportunity? The Belt and Road Initiative and the role of debt in the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64 (3): 365-377. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2021.2012816

- Wang, Hongmiao. 2022. “中国国企改革过程中公司治理特征、挑战与对策.” [Characteristics, Challenges and Countermeasures of Corporate Governance in the Reform of Chinese State-owned Enterprises.] Economic Aspect 6. DOI: 10.16528/j.cnki.22-1054/f.202206052.

- Wang, Bin. 2023. “Social Infrastructure Development Aid for Xinjiang and Lessons for CPEC: A Case Study of Shanghai-Kashgar Paired Assistance Program.” In The Political Economy of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Singapore: Springer Nature, 219-251.

- World Steel Association. 2020. “Global crude steel output increases by 3.4% in 2019,” January 27. Accessed July 10, 2022: https://worldsteel.org/media-centre/press-releases/2020/global-crude-steel-output-increases-by-3-4-in-2019/.

- World Steel Association. 2022. “Steel in buildings and infrastructure.” Accessed July 10, 2022: https://worldsteel.org/steel-topics/steel-markets/buildings-and-infrastructure/.

- World Bank. 2018. “Belt and Road Initiative,” March 29. Accessed March 5, 2019: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative.

- Wu, Yanrui. (2000). “The Chinese steel industry: Recent developments and prospects.” Resources Policy 26 (3): 171-178. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4207(00)00026-X

- Xi, Jinping. 2017. Important Speeches at the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Xie, Yu, and Xiang Zhou. (2014). “Income inequality in today’s China.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (19): 6928-6933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403158111

- Xinjiang Morning News. 2017. “维吾尔族党员干部在落实总目标中要切实做到讲政治守纪律.” [Party members and cadres of the Uyghur ethnic group must earnestly pay attention to politics and observe discipline in the implementation of the general goal.] Sina News, June 6. Accessed June 7, 2021: https://news.sina.cn/gn/2017-06-06/detail-ifyfuvpm7555569.d.html.

- Xinhua News, 2017. “陈全国同志简历.” [Resume of Comrade Chen Quanguo]. Xinhua News Agency, October 25. Accessed December 4, 2023: https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2017-10/25/content_5234440.htm.

- Xinhua News, 2023. “共建“一带一路”·权威访谈丨扎实推进“一带一路”核心区高质量发展取得新进展新成效——专访新疆维吾尔自治区党委常委、人民政府副主席玉苏甫江·麦麦提” [“Jointly Building the “Belt and Road”·Authoritative Interview | Solidly promoting the high-quality development of the core areas of the “Belt and Road” and achieving new progress and new results—Exclusive interview with Yusu Fujiang Maimeti, Member of the Standing Committee of the Party Committee of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and Vice Chairman of the People’s Government”] Belt and Road Portal, October 4. Accessed May 1, 2024: https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0HNTH0I6.html.

- Xinjiang Daily, 2023. “大道如砥征程阔——新疆推进“一带一路”核心区建设述评” [“The road is long and the journey is long: A review of Xinjiang's promotion of the construction of the core area of the “Belt and Road"”] The People’s Government of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, September 07. Accessed June 1, 2024: https://www.xinjiang.gov.cn/xinjiang/xjyw/202309/45c3e29ace3949b3a9e0949182588fe5.shtml.

- Ye, Min. 2019. “Fragmentation and Mobilization: Domestic Politics of the Belt and Road in China”. Journal of Contemporary China 28 (119): 696-711. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1580428

- Yeh, Emily. 2019. Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Yu, Hong. 2023. “Is the Belt and Road Initiative 2.0 in the Making? The Case of Central Asia.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53 (3): 535-547. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2022.2122858

- Zhang, Qiao. 2012. “钢铁行业需要砍掉落后产能” [“The steel industry needs to cut outdated production capacity”]. China Radio Network, November 30. Accessed June 12, 2024: http://finance.cnr.cn/jysk/201211/t20121130_511456128.shtml.

- Zhang, Ruilian, Guoqing Shi, Yuanni Wang, Si Zhao, Shafiq Ahmad, Xiaochen Zhang, and Qucheng Deng. 2018. “Social impact assessment of investment activities in the China–Pakistan economic corridor.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 36 (4): 331-347. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2018.1465227

- Zhang, Xin. 2017. “Chinese Capitalism and the Maritime Silk Road: A World-Systems Perspective.” Geopolitics 22 (2): 310–331. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1289371

- Zhao, Ziqiang, and Shibi Ren. 2021. “36家钢铁公司一季度净利润同比增长243.77% 机构称板块估值存在较大向上修复空间!” [The net profits of 36 steel companies in the first quarter increased by 243.77% year-on-year. The agency said that there is considerable room for upward restoration in sector valuations!] Sina Finance, May 14. Accessed October 2, 2023: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1699734730828285736&wfr=spider&for = pc.

- Zeeshan, Afsheen, Shafei Moiz Hali, and Nauman Al Talib. 2021. “Comparative Analysis of Debt Trap and Shared Economic Growth Perspectives for Belt Road Initiative.” Ilkogretim Online 20 (6): 209-219.