ABSTRACT

In this internationalised world, graduate employability in terms of intercultural communication skills needs to be taken into account in higher education. The present study aims to explore the effects of critical incident task instruction on English non-majored undergraduates’ intercultural competence. One group of students received ten weeks of instruction with one critical incident task per week and another group received standard English classes. Data were collected from the students’ pre- and post-test. The results showed a significant and strong effect of the intervention with critical incident tasks. Implications for educational practice are presented for further teaching with critical incident tasks.

Introduction

Nowadays, in the Mekong Delta and Ho Chi Minh city, the economy has been thriving and many foreign companies are establishing their businesses in these areas. This means that in several organisations, Western employers and Vietnamese employees collaborate. In order be productive at work, these Western and Vietnamese professionals need to communicate in an effective way. Vietnamese professionals need to be educated in effective communication and gain intercultural awareness during their school career, and intercultural awareness should be part of English classes for Vietnamese students, in addition to language acquisition. However, in higher education, intercultural communication has been neglected or has low priority. There are multiple reasons for the lack of focus on culture and intercultural skills training in English lessons, such as grammar-translation method dominance, teachers’ workload and a shortage of time for developing student-centred lessons, as well as poor facilities. The growing demand to integrate intercultural learning and English language learning has challenged conventional practices of teaching English in Vietnam (Nguyen Citation2013). Accordingly, shifting from traditional teaching practice to an innovative teaching practice, in order to develop students’ intercultural capacity, is one of the most important missions of English language education in Vietnam. The current research aims to develop further insights into how future graduates’ intercultural competence can be enhanced by using critical incident open-ended tasks in English language education.

Intercultural competence development in Vietnam

As socialising and communicating appropriately in a foreign language, specifically English, is a benefit for obtaining a job, it is crucial for language teachers to emphasise the role of culture instruction in language classrooms. Both employers and educators recognise that learners should be prepared for living in a multicultural world and becoming skillful negotiators in increasingly intercultural work situations (Webber Citation2005; Lies Citation2010; Tran Citation2017). In the context of Vietnam, after the implementation of Doi Moi policy (1986), the economy has rapidly changed, which also has caused a major transformation of the labour market. Though ‘work-readiness’ is gradually being taken into consideration by most related stakeholders, including employers, higher education institutions, students and their families, not much has been done to strengthen the connection between higher education institutions and enterprises to bring students up to speed regarding internationalism (Tran Citation2012). The effort to prepare students with the necessary skills and knowledge required by the contemporary labour market has been lacking due to traditional teaching and learning methods in higher education institutions, inadequate infrastructure, lack of funding and the lack of connection among universities, research institutions and industrial activities (Tran Citation2012). A study by Tran (Citation2013), looking at the skills that are the most essential for Vietnamese graduates to work effectively with employers, showed that both employers and graduates perceive soft skills encompassing collaborative work skills, communication skills, independent working skills, presentation skills, social understanding and decision making skills as the most significant attributes employers are looking for. Tran (Citation2013) also emphasised that communication skills help students to enter the job market and remain successful at work. Nguyen (Citation2013) conducted a study to examine how culture, culture learning and intercultural competence development are integrated into English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms in higher education in Vietnam. Two findings are especially noteworthy. First, the subject of culture and culture learning is either rarely touched upon or treated in courses separate from the EFL programme (Nguyen Citation2013). Second, both teachers and students identified a number of constraints that limited their opportunities and motivation to engage in teaching and learning culture (Nguyen Citation2013). Also, Nguyen, Harvey, and Grant (Citation2016) examined Vietnamese EFL teachers’ belief about the role of culture in language teaching. The findings showed that teachers mainly focused on the language knowledge and skills in their EFL classes and culture represented a minor part of their teaching. The teachers reported some noticeable reasons for the lack of culture instruction in their lessons: students’ low level of language proficiency, the demands of university examinations, time constraints versus heavy workload of language to be covered and teacher perceptions of their own limited cultural knowledge (Nguyen, Harvey, and Grant Citation2016).

While language and culture instruction are two inseparable domains, it is essential that culture should become a core and integrated element in language teaching in order to promote the development of language learners’ intercultural competence (Nguyen, Harvey, and Grant Citation2016). Additionally, while intercultural competence needs the development of general cultural knowledge about one’s own, as well as other cultures (Perry and Southwell Citation2011) and cognitive, affective and behavioural processes, critical incident technique or critical incident tasks (CIT) have been shown to provide learners with those attributes since Cushner (Citation1989), Aoki (Citation1992) and Tolbert and McLean (Citation1995) contended that after being trained with critical incident techniques, participants were better able to act more effectively in ambiguous situations thanks to their knowledge about cultural concepts and their problem-solving abilities. Accordingly, in the current study, critical incident tasks were adopted with the view to enhance EFL students’ intercultural competence.

Critical incident tasks

Critical incident tasks are communication situations that participants (or one participant) consider as problematic and confusing. Typically, critical incidents consist of examples of situational clashes – situations where unexpected behaviour occurs. Flanagan (Citation1954, 327) defines the critical incident technique as … ‘a set of procedures for collecting direct observations of human behaviour in such a way as to facilitate their potential usefulness in solving practical problems and developing broad psychological principles’. The purpose of the critical incident technique is to develop one’s ability to see interaction situations from the perspective of different cultures. Critical incidents can be an effective strategy to promote cross-cultural awareness since they highlight the differences and misunderstandings from a cultural perspective, and create chances for learners to think critically and analytically about these critical situations.

CIT has been used by intercultural trainers for decades (Flanagan Citation1954; Brislin Citation1986; Cushner Citation1989; Aoki Citation1992; Tolbert and McLean Citation1995; Bochner and Coulon Citation1997; McAllister et al. Citation2006; Herfst, Oudenhoven, and Timmerman Citation2008; Milner, Ostmeier, and Franke Citation2013), in different forms and using different names, such as cultural assimilator, intercultural sensitizer activity, situational judgement test and encounter exercises. Basically, critical incident techniques have three common characteristics. The first is that critical incident tasks are all hypothetical situations or vignettes ‘involving two or more well-meaning characters from different cultures which results in some kind of misunderstanding, puzzlement, or problem’ (Snow Citation2015, 287). The second shared element is that critical incident tasks contain one or more questions asking the learners to consider the cause of the problem or misunderstanding (Snow Citation2015). Lastly, if the goal of training is to change behaviour or attitudes, other approaches can be more applicable than critical incident exercises. The purpose of the critical incident technique is to raise learners’ awareness only (Tolbert and McLean Citation1995; Collins and Pieterse Citation2007; Hiller Citation2010).

CIT was initially developed by Flanagan (Citation1954). In his study, he collected 1000 pilot candidates’ reports about specific reasons for failure in learning to fly. The study demonstrated its usefulness for developing better procedures for obtaining a representative sample of factual incidents regarding pilot performance. Flanagan’s findings supported practical problem-solving measures in areas such as employee performance enhancement and scientific behavioural analysis. Thanks to the success of Flanagan’s study, the use of CIT flourished in multiple disciplines such as aviation programmes, medical and health care training, employee and expatriate training, intercultural competence development programme, etc.

Cushner (Citation1989) utilised the critical incident technique (CIT), in what he called a culture-general assimilator, to teach 28 adolescent international exchange students, representing 14 countries and hosted by Intercultural Program New Zealand for a period of one year after their arrival in the host country. The control group of 22 students received a traditional Intercultural Program New Zealand orientation. The results indicated that students who were taught with CIT were better able to identify dynamics which mediate cross-cultural interaction and adjustment, compared with other students. Key indicators were: (1) students in the experimental group demonstrated greater ability to generate and analyse misunderstanding in a personal incident, (2) they had greater control of their environment, and (3) regarding problem-solving abilities, they had a strong tendency to approach situations with more cultural-knowledge and to take more initiative in problematic situations. From the findings, the author concluded that the culture-general assimilator can initiate the introduction of important cultural concepts. It can help students become more effective communicators with people from other cultures due to the fact that they have gained a new body of knowledge, concepts, and vocabulary.

Similar results were found in seven other studies conducted by Mitchell and Foa (Citation1969), Chemers (Citation1969), Worchel and Mitchell (Citation1970), O’brien, Fiedler, and Hewett (Citation1971), Aoki (Citation1992), Herfst, Oudenhoven, and Timmerman (Citation2008) and Nakagawa (Citation2014). Congruent with Cushner’ findings, the participants in those studies also obtained isomorphic attributions. Isomorphic attributions mean that people from different cultures formulate analogous interpretations to given behaviours. These attributions indicate individuals’ ability to communicate effectively in intercultural contexts, have greater control of their environment, be more active and more likely to take initiative in problem-solving situations.

Albert (Citation1986) identified a possible weakness of the critical incident technique: learners might not recognise the importance of social factors and contexts when a simple critical episode is used; thus, it may be crucial to make these factors explicit, as not all learners are sufficiently intuitive to grasp the issues contained in the incident. For example, one incident details a long conversation between a Chinese employee with his Western mentor or manager about the Chinese employee’s hesitance to raise his voice or participate in company meetings. Throughout the conversation, many argumentative statements between these two characters are presented. If students are not informed beforehand about culturally and socially relevant factors such as face saving expectations in public places among the Chinese, or the participative leadership style of many Western companies’ culture, they would not be able to understand why the characters in the scenario act in a certain way. Due to this, Albert (Citation1986) noted that CIT should be combined with other approaches in order to maximise the effectiveness of learning.

In the above-mentioned studies, critical incident tasks can be classified into two major categories: tasks with close-ended questions (cultural assimilator, intercultural sensitizer activity and situational judgement test) and tasks with open-ended questions (encounter exercises). Tasks with close-ended questions are constructed from a hypothetical scenario with multiple choice exercises, including a list of possible explanations for the situation and an answer key that discusses the merits of each possible explanation (Snow Citation2015; Richard et al. Citation2016). Tasks with open-ended questions requires learners to generate possible explanations of the situation for themselves. The open-ended format requires more of students’ engagement in the discussion to work out the answers than the close-ended ones do, and might therefore be better suited to be incorporated in English as Foreign Language classes (Snow Citation2015). Open ended tasks also provide good speaking and expository writing practice.

In the current study, we decided to adopt the critical incident technique to enhance the English non-majors’ intercultural competence. We decided to choose the critical incident open-ended task instead of the close-ended one.

In order to achieve our goal, we aimed to answer the following research question:

Do critical incident open-ended tasks enhance English non-majored undergraduates’ awareness of intercultural communication?

Method

Design

A pretest-posttest control group design was used to examine the effects of critical incident tasks on students’ awareness of intercultural communication. Both the intervention group and the control group were instructed using the same instructional course designed for English non-majors with their majors in the technical domain. The course textbook was adapted from the English course book titled ‘Outcomes Intermediate: Real English for the Real World, 1st Edition’ by Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley (Citation2011). The intervention utilised 10 critical incident tasks (10 workplace scenarios) (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for an example) added to the course instruction. Students in the experimental condition and control condition completed the pre- and post-test ().

Table 1. Research design.

Participants

Participants were 322 second-year English non-majors in 6 classes of Technical Engineering (131 females). The participants were all 19 years old. The students’ classes were randomly divided into an experimental (4 groups with 234 students) or control (2 groups with 88 students) condition. All students were required to take an entrance university examination and an English placement test in their first year. Moreover, they followed two courses of General English for English non-majors in their first year and they all passed the final tests of those courses. All the participants were from the Mekong Delta regions in Vietnam.

Procedures

The course took place in 10 weeks, with 2 meetings of 4 hours each week. For the treatment condition, students received one critical incident task in one meeting per week. The other meeting was used for regular education or textbook instruction and students’ practice of 4 English skills for the TOEIC test. In the control condition (CC), the students only received the regular course instruction with the textbook and practice of 4 English skills for TOEIC test of four hours each week. The students in the control group received more English-skill assignments than the experimental group. In , we summarise the procedures of the treatment condition.

Table 2. Course procedures for the treatment condition.

Of the four experimental groups, two were instructed by one instructor, who is one of the authors and has been engaged in teaching English as a foreign language for 7 years. The other two groups were instructed by the other instructor, who is also an English teacher and has had experience in teaching English as a foreign language for 10 years. The two student groups in the control condition were instructed by two other teachers, one teacher for each group. These two instructors were also English teachers. The first one was involved in instructing English as a foreign language for 15 years and the other for 8 years.

Treatment condition

Students in the experimental condition were given a critical incident task treatment. In the first three weeks, lessons contained five parts: 1) an initiating activity, 2) introduction of the critical incident task, 3) discussion of the critical incident task in pairs, 4) performing the critical incident task individually and 5) wrap-up.

– In the initiating activity, cultural differences between Western and Eastern culture in the workplace were introduced through supplementary cultural materials, including the cultural notes in the form of texts or pictures or cultural video clips. The purpose of this initiating activity was to help the learners grasp the major cultural points that would emerge in the critical incident task afterwards.

– Subsequently, the critical incident task was introduced and explained. During the first three lessons, a model or instructions of the task was provided so that the students could master the aims and significant points in performing the task.

– Next, the students discussed the incidents in pairs. In all tasks, the students were asked to summarise the scenario of the incidents and work out the problematic issues of those incidents seen from the perspective of effective intercultural communication. We let the students discuss the incidents in pairs as we aimed to facilitate effective social skills among the students, which is a stimulus for their awareness of intercultural communication (Rebecca Citation1997; Theodore Citation1999; Marjan and Seyed Citation2012). Additionally, considering the fact that the complicated structure of the critical incident tasks and their follow-up questions require critical and higher-order thinking skills from learners to arrive at an appropriate answer, the function of working out the problems in pairs can ease the process of figuring out the answer.

– During the following step, the students were requested to give their answers individually on an answer sheet. The sheet aimed to capture the students’ final product, as they perceived it, which means that we expected to see how they extracted the information they obtained from their peer discussion and demonstrated this knowledge from their own perspective. We decided to give freedom to the learners’ choice of language for answering the questions given their limited level of English competence, which was elementary, and might prevent them from giving the best response to the task.

– Finally, there was a wrap-up phase in which teachers summarised and asked questions about what the learners had just studied.

In the last seven weeks, lessons had only four parts, leaving out the introduction of the task as students had become accustomed to the task.

12 critical incident tasks (including pretest and posttest) from several Intercultural Booklets (see Supplementary Appendix 2) designed as training guides for Intercultural Education Program were utilised for the intervention program. There was one task (task 8) written by the researcher on the basis of a real story in a foreign subsidiary in Vietnam. These tasks were selected for three reasons. First, these critical incident themes were congruent with the cultural issues arising from earlier studies, which are the main authentic concerns of professionals currently working in foreign subsidiaries and joint-ventures in Vietnam. Second, these incidents were purposely designed for undergraduate students taking their first course in intercultural communication (James Citation2015) and for professional training within multicultural corporations in an effort to improve their workers’ relations, equalise opportunities and enhance workplace experiences for their increasingly multicultural labour force (Norquest College Citation2015). The intended trainees who work with these critical incidents resembled the participants of this study, since we worked with undergraduate students who were taking their first course in intercultural communication and planned to work with foreign professionals after graduation. Finally, these critical incidents give an in-depth look into two contrasting cultural ideologies, Eastern and Western culture. These two distinctive cultures were juxtaposed to awaken learners’ awareness of dissimilarities, arouse their curiosity, openness and empathy for Western culture.

Control condition

The two student groups in the control condition were instructed by two teachers, one teacher for each group. These two instructors were also English teachers. The first one had been involved in instructing English as a foreign language for 15 years and the other for 8 years. The students in the control condition (CC) only received the standard course instruction – using a textbook for four hours each week. The students in the control group received more English-skill assignments than the experimental group.

Data collection

The pretest and posttest were structured using the same format as the 10 critical incident tasks associated with the intervention. Participants completed the pretest at the beginning of the course and the posttest one week after the final critical incident task used in the experimental condition. Data were gathered via students’ answer sheets. In the answer sheet there were task instructions and a critical incident related to a workplace scenario in the form of texts or conversations among characters, as well as a table with 4 questions. The students were asked to read the scenario in 5 minutes, discuss the scenario and then work on solutions to the problem in pairs for 20 minutes. Afterwards, they wrote down their answers to the 4 questions at the table individually. The 4 questions were formulated in line with 4 indicators: (1) students’ understanding of the scenario (scenario understanding); (2) students’ understanding of the miscommunicated points in the scenario (miscommunication understanding); (3) students’ awareness of effective communication in Western culture (awareness communication Western); (4) students’ awareness of effective communication in Vietnamese or Eastern culture (awareness communication Eastern). They were constructed with ascending difficulty, ranging from basic analytical to higher critical thinking (the pre-test and post-test are included in Supplementary Appendix 3).

The students’ answers were rated using a rubric, based on the Intercultural Knowledge and Competence Value Rubric for grading (Association of American Colleges and Universities Citation2013), Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (Bennett Citation1993) and Deardorff’s intercultural framework (Deardorff Citation2006). We decided to integrate this rubric to our grading criteria because this rubric offers a ‘systematic’ way to measure learners’ capacity to determine their own ‘cultural patterns’, make comparisons with others and ‘adapt empathetically and flexibly to unfamiliar ways of being’ (Association of American Colleges and Universities Citation2013).

Students’ answers in the pre-test and post-test were rated using a 10-point grading scale with 5 levels (see Supplementary Appendix 4). For each of the four questions, 2.5 points could be earned, in which level 1 (0.5 point) was the lowest and level 5 (2.5 points) was the highest. The students’ answers were graded by the first instructor of the experimental group, one of the authors of this article. In order to ensure the reliability of the grading procedure, the two instructors of the experimental groups rated the posttest of one experimental group (N = 56) with a satisfactory correlation (r = 0.692).

Data analysis

In order to examine the effect of the series of critical incident tasks on learners’ awareness of intercultural communication, we performed a multivariate analysis of covariance with the condition (critical incident task or standard education) as the independent variable, the four indicators of awareness of intercultural communication at the posttest as dependent variables, the pretest scores on the same indicators as covariates.

Results

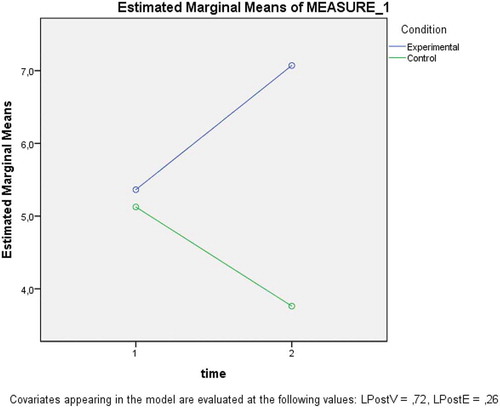

In , we present the descriptive statistics for both conditions. We found a multivariate effect for condition (Wilks’ λ = .444; df = 4,224; p < .001; ɳ2 = .556), which showed a significant difference between both conditions on the posttest scores on students’ awareness of intercultural communication. Students from the experimental condition generally showed significant higher scores on the posttest on awareness of intercultural communication than the students from the control condition (see ).

Table 3. Means and standard deviations of pretest and posttest.

The test of between-subjects effects with 4 indicators as dependent variables showed a significant difference of 4 indicators in the posttest results between the experimental and control condition. The largest difference was found in awareness communication Western (F(175.983); p < .000; ɳ2 = 0.437) and awareness communication Eastern (F(183.384); p < .000; ɳ2 = 0.447). A smaller but still significant effect was found in scenario understanding (F(67.750); p < .000; ɳ2 = 0.230) and miscommunication understanding (F(129.011); p < .000; ɳ2 = 0.362).

Discussion

Students following the critical incident task procedure demonstrated stronger development of their awareness of intercultural communication compared to the students in the control condition. Accordingly, we can conclude that teaching through critical incident open-ended tasks, with student pair work, could generally enhance students’ intercultural competence in terms of awareness of intercultural communication.

We found significant differences regarding critical incident open-ended tasks on students’ awareness of intercultural communication between the experimental and control group among the four indicators: (1) understanding of the scenario, (2) understanding of the miscommunicated points in the scenario, (3) awareness of effective communication in Western culture and (4) awareness of effective communication in Eastern culture in order to suggest solutions to the problems of the characters. The differences were stronger for awareness communication Western and awareness communication Eastern than scenario understanding and miscommunication understanding. Those results are predictable since the four indicators representing four questions were designed using an ascending level of difficulty, in which number 1 is the easiest, number 2 being in the middle and 3 and 4 as the most difficult ones. We noticed that the trained students and untrained ones differed in terms of logical development of intercultural competence. Their development went from curiosity and discovery (scenario understanding), next observation, analysis, evaluation and interpretation (miscommunication understanding), then adaptability, flexibility and empathy to finally, effective and appropriate communication (awareness communication Western and awareness communication Eastern). Students in the experimental condition were found to be able to use the knowledge they gained from training to explain and better provide suggestions pertaining to cross-cultural misunderstandings, compared to students from the control condition. Replicating other studies’ results (Flanagan Citation1954; Cushner Citation1989; Aoki Citation1992; McAllister et al. Citation2006; Nakagawa Citation2014, etc.), the findings highlight that the critical incident technique is a useful tool for cross-cultural training in EFL classes, particularly for introducing important cultural concepts that direct further cross-cultural training.

Implications

Using the critical incident with open-ended tasks is promising for providing cross-cultural teaching as part of EFL classrooms. We also identify the following implications. First, teaching general cultural knowledge might not suffice for learners’ preparation to engage in an intercultural context (Tolbert and McLean Citation1995). Learners need essential skills to succeed in their professional environment and the critical incident approach might offer those necessary skills in order to function in international workplace settings. Additionally, although the main goal of the current study is to enhance future graduates’ intercultural awareness, we believe that the critical incident technique is also useful for future expatriate manager training, because in an intercultural context, awareness of intercultural communication among all parties is needed. Second, critical incident tasks might be effective when they are combined with other ways of teaching. In our study, the instructors performed the initiating task through texts, pictures or video clips. Third, in order to optimise the training, we viewed pair work or group work as a good option. Learners collaborated and discussed a lot to comprehend what was happening in the scenario and even for the explications and resolutions to the problems. Fourth, due to time limitations and the workload of combining the course book and the use of critical incident tasks, some of the extra English language assignments were eliminated in the experimental group. We suggest that in future studies, more time is needed for the course, so that instructors are not pressured to finish two tasks simultaneously and learners can have more room to fully develop both language and intercultural competences. Finally, we also suggest that CIT might be effective when a series of tasks are used, which means that working with the tasks should happen every week so that students see such activities as being integrated into their overall learning.

Limitations

Two instructors of the experimental groups discovered that the students became a little bored when they performed the same task using the same format every week. Some students remained motivated until the end of the course but others lost interest when they performed the same task every week. Therefore, we suggest that in future research critical incident tasks be used every week; nevertheless, role play or other forms of cross-cultural training can be utilised in conjunction with CIT in order to optimise student learning.

Conclusions

Integrating culture instruction into language lessons as a preparation for students’ intercultural encounters should be more prominent in higher education. Critical incident tasks can provide a basic foundation that can serve many needs, including stimulating cross-cultural learning. We hope that this successful implementation of critical incident tasks will give a boost to the growing trend of intercultural competence teaching in the region.

Supplementary Appendices 1-4

Download MS Word (37.9 KB)Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Fellowship Programmes (Nuffic). We would like to thank the students and the teachers for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tran Thien Quynh Tran

Tran Thien Quynh Tran obtained a Bachelor’s Degree in English Linguistics at Can Tho University, Vietnam. After her graduation, she worked as a lecturer and academic assistant at Vietnamese American Training College in Can Tho city from 2005 to 2007. Thereafter, she left and obtained another job, working as an English lecturer at Can Tho University of Technology. In 2011, she earned her Master Degree in Principles and Methods in English Language Education at Can Tho University, Vietnam. She earned her Phd from Leiden University, the Netherlands in 2018 with the doctoral degree titled ‘Cultural differences in Vietnam: Differences in work-related values between Western and Vietnamese culture and cultural awareness at higher education’.

Wilfried Admiraal

Wilfried Admiraal is a Full Professor Educational Sciences and director of ICLON Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching. He graduated in Social Psychology and in 1994 he defended his PhD-thesis on teachers’ coping strategies with stressful classroom events. He is chair of the research program Student engagement and achievement in open online higher education of the Centre for Education and Learning of the strategic alliance of the universities of Delft, Leiden and Rotterdam.

Nadira Saab

Nadira Saab is an Associate Professor at ICLON Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching. She graduated in Developmental and Educational Psychology and received her PhD from the University of Amsterdam in 2005. Her PhD thesis was focused on collaboration in experiential learning environments. She works at ICLON as a teacher educator and a researcher. Her research focuses on the impact of powerful and innovative learning methods on learning processes, such as collaborative learning, computer assisted learning and assessment and motivation. She studies these questions in children, adolescents and young adults. At the moment she supervises 8 PhD students.

References

- Albert, R. D. 1986. “Conceptual Framework for the Development and Evaluation of Cross-cultural Orientation Programs.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10: 197–213. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(86)90006-4.

- Aoki, J. 1992. “Effects of the Culture Assimilator on Cross-cultural Understanding and Attitude of College Students.” JALT Journal 14 (2): 107–125. https://jalt-publications.org/files/pdf-article/jj-14.2-art1.pdf

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. 2013. “Intercultural Knowledge and Competence Value Rubric.” https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/intercultural-knowledge

- Bennett, M. J. 1993. “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In Education for the Intercultural Experience, edited by R. M. Paige, 21–71. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

- Bochner, F., and L. Coulon. 1997. “A Culture Assimilator to Train Australian Hospitality Industry Workers Serving Japanese Tourists.” The Journal of Tourism Studies 8 (2): 8–17. https://www.jcu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/122368/jcudev_012640.pdf

- Brislin, R. W. 1986. “A Culture General Assimilator: Preparation for Various Types of Sojourns.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10: 215–234. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(86)90007-6.

- Chemers, M. 1969. “Cross-cultural Training as a Means for Improving Situational Favorableness.” Human Relations 22: 531–546. doi:10.1177/001872676902200604.

- Collins, M. N., and A. L. Pieterse. 2007. “Critical Incident Analysis Based Training: An Approach for Developing Active Racial/cultural Awareness.” Journal of Counseling and Development 85: 14–22. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00439.x.

- Cushner, K. 1989. “Assessing the Impact of a Culture-general Assimilator.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 13: 125–146. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(89)90002-3.

- Deardorff, D. K. 2006. “Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization.” Journal of Studies in International Education 10: 241–261. doi:10.1177/1028315306287002.

- Dellar, H., and A. Walkley. 2011. Outcomes: Elementary. Heinle-Cengage Publisher.

- Flanagan, J. 1954. “The Critical Incident Technique.” Psychological Bulletin 51 (4): 1–33. https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/cit-article.pdf

- Herfst, S. L., J. P. Oudenhoven, and M. E. Timmerman. 2008. “Intercultural Effectiveness Training in Three Western Immigrant Countries: A Cross-cultural Evaluation of Critical Incidents.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 32: 67–80. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.10.001.

- Hiller, G. G. 2010. “Innovative Methods for Promoting and Assessing Intercultural Competence in Higher Education.” Proceedings of Intercultural Competence Conference 1: 144–168. http://cercll.arizona.edu/ICConference2/malgesini.pdf

- James, W. N. 2015. Intercultural Communication: A Contextual Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Lies, S. 2010. “Assessing Intercultural Competence: A Framework for Systematic Test Development in Foreign Language Education and Beyond.” Intercultural Education 15 (1): 73–89. doi:10.1080/1467598042000190004.

- Marjan, L., and M. G. Seyed. 2012. “Benefits of Collaborative Learning.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 31: 486–490. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.091.

- McAllister, L., G. Whiteford, B. Hill, N. Thomas, and M. Fitzgerald. 2006. “Reflection in Intercultural Learning: Examining the International Experience through a Critical Incident Approach.” Reflective Practice 7 (3): 367–381. doi:10.1080/14623940600837624.

- Milner, J., E. Ostmeier, and R. Franke. 2013. “Critical Incidents in Cross-cultural Coaching: The View from German Coaches.” International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring 11 (2): 19–32. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1402&context=gsbpapers

- Mitchell, T., and U. Foa. 1969. “Diffusion of the Effect of Cultural Training of the Leader in the Structure of Heterocultural Task Groups.” Australian Journal of Psychology 1: 31–43. doi:10.1080/00049536908255767.

- Nakagawa, N. 2014. Analyzing learning effect of using intercultural communication training methodology in foreign language class. The Theory of Distribution Science University. Human, Society, Nature. ISSN: 13465538.

- Nguyen, L., S. Harvey, and L. Grant. 2016. “What Teachers Say about Addressing Culture in Their EFL Teaching Practices: The Vietnamese Context.” Intercultural Education 27 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1080/14675986.2016.1144921.

- Nguyen, T. L. 2013. “Integrating culture into Vietnamese university EFL teaching: a critical ethnographic study.” Unpublished Ph.D thesis, Auckland University of Technology.

- Norquest College. 2015. Critical Incidents for Intercultural Communication in the Workplace: Scene-by-Scene Breakdowns. Edmonton: Centre for Innovation and Development.

- O’brien, G., F. Fiedler, and T. Hewett. 1971. “The Effects of Programmed Culture Training upon the Performance of Volunteer Medical Teams in Central America.” Human Relations 24: 304–315.

- Perry, L. B., and L. Southwell. 2011. “Developing Intercultural Understanding and Skills: Models and Approaches.” Intercultural Education 22 (6): 453–466. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.644948.

- Rebecca, L. O. 1997. “Cooperative Learning, Collaborative Learning, and Interaction: Three Communicative Strands in the Language Classroom.” The Modern Language Journal 81 (4): 443–456. doi:10.2307/328888.

- Richard, L. G., W. Leah, K. A. Brigitte, R. Joseph, and L. L. Ou (2016). “Assessing Intercultural Competence in Higher Education: Existing Research and Future Direction”. EST Research Report Series, 16–25. ISSN: 2330-8516.

- Snow, D. 2015. “English Teaching, Intercultural Competence, and Critical Incident Exercises.” Language and Intercultural Communication 15 (2): 285–299. doi:10.1080/14708477.2014.980746.

- Theodore, P. 1999. “The Motivational Benefits of Cooperative Learning.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 78: 59–65. doi:10.1002/tl.7806.

- Tolbert, A. S., and G. N. McLean. 1995. “Venezuelan Culture Assimilator for Training United States Professionals Conducting Business in Venezuela.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 19 (1): 111–125. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(94)00027-U.

- Tran, L. H. N. 2017. “Developing Employability Skills via Extra-curricular Activities in Vietnamese Universities: Student Engagement and Inhibitors of Their Engagement.” Journal of Education and Work 30: 854–867. doi:10.1080/13639080.2017.1349880.

- Tran, T. T. 2012. “Vietnamese Higher Education and the Issue of Enhancing Graduate Employability.” Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 3 (1): 2–16. doi:10.21153/jtlge2012vol3no1art554.

- Tran, T. T. 2013. “Limitation on the Development of Skills in Higher Education in Vietnam.” Higher Education 65: 631–644. doi:10.1007/s10734-012-9567-7.

- Webber, R. 2005. “Integrating Work-based and Academic Learning in International and Cross-cultural Settings.” Journal of Education and Work 18 (4): 473–487. doi:10.1080/13639080500327899.

- Worchel, S., and T. Mitchell. 1970. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Thai and Greek Cultural Assimilators. Seattle: University of Washington, Organizational Research Group.