ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore how minority parents construct and promote cultural identities through a multicultural school event in Norway. Such events respond to the call for diverse and inclusive initiatives to facilitate learning, belonging, and cohesion in schools. Schools see these events as helping further inclusion. Prior research on the subject has criticised such events for promoting essentialist understandings of cultural identities, hence regarding them as counterproductive to the aim of promoting inclusion. This research has directed scarce attention to the participant perspective, among them minority parents. Inspired by a broad understanding of linguistic landscaping, we documented the displayed representations at the stalls. Subsequently, using the Kurdish stall as an example, we encouraged the Kurdish parents to reflect on the meaning of the representations in semi-structured interviews. The findings indicate that the Kurdish parents involved view the event as an important space for creative construction of transnational and diasporic identities, as well as an opportunity for a minority group to strive for acceptance for its cause. We end the article by reflecting on the pedagogical potential of representations in multicultural school events.

Introduction

As a direct response to increasing diverse communities, many schools in Norway have developed pedagogical practices to promote international awareness, social cohesion, and inclusion by arranging international days, weeks, or festivals in various forms. Interestingly, while dominant theory-based research has traditionally criticised pedagogical initiatives of this kind, referring to multicultural school events as counterproductive to the aim of inclusion (Hoffman Citation1996; Troyna Citation1993; Øzerk Citation2008), more recent empirical studies have presented a more nuanced picture. By telling the stories of the participants, this research describes the same events as treasured and valuable. Researchers have specifically asserted that these events promote participation, trustful relationships, and sense of belonging, indicating that multicultural school events can be creative spaces for identity construction (Lee Citation2015; Niemi and Hotulainen Citation2016).

Recognising the greater complexity in multicultural school events and the need for more in-depth studies on participant experiences, our research team set out to explore a multicultural school festival in a Norwegian primary school where minority groups, especially minority parents, appear as key stakeholders. More specifically, in this article, we report on a study of one of the prominent minority groups at the festival, the Kurds, who are typically characterised as a minority group with transnational and diasporic identity (Wahlbeck Citation1999). Using the Kurdish parents as an example, we ask how transnational and diasporic identities are being constructed during a multicultural school festival. The present study contributes to nuancing the critical research in the field, showing the complexity of the meanings parents ascribe to their representations on display.

Prior research on the subject matter

Critics primarily argue that multicultural school events are based on essentialist concepts of culture. According to these critics, rather than stimulating reflexivity, critical thinking, self-awareness, and transformative learning, such events do exactly the opposite. This is particularly true of multicultural school festivals, which Diane Hoffman (Citation1996, 565) has called ‘hallway multiculturalism’, stating that these events reveal that ‘we really do not know how to do multiculturalism in schools’. From the Norwegian context, Kamil Øzerk (Citation2008, 223) has used the term ‘festivalization’ when speaking of the same events, criticising them as promoting stereotypical images of us and them and as establishing rigid categories of what is normal and what is exotic. Obviously, from the perspective of critical theory within multicultural education research (e.g. Banks Citation1988, May and Sleeter Citation2010; Watkins and Noble Citation2019), these events become easy targets.

In a previous study on an ‘international week’ in a primary school, conducted by members of our research group, essentialist traits were found, thereby confirming the critics’ arguments. However, the study delved more deeply into the perspectives of the school leadership, the teachers, the students, and the parents, and the authors concluded that the international week was experienced as ‘a powerful social space where constructions of new identities take place’ (Dewilde, Kjørven, Skaret, and Skrefsrud Citation2017). Being well aware of the criticism from the research field, the school’s principal remained steadfast, claiming ‘the international week is a symptom of what the school is all about’ (Dewilde, Kjørven, Skaret, and Skrefsrud Citation2017), as it serves to establish ‘a common understanding of the school as a multicultural school. Students get to know each other across classes, groups, and language. Something positive is happening. It makes us uplifted and happy!’ (484). This empirical study aims to go further into what ‘is happening’, in this particular case, and to better understand the multicultural school festival as a space for identity construction.

To our knowledge, there are no studies on multicultural school events highlighting the issue of participant identity construction. If we go outside the pedagogical sphere and broaden the scope to multicultural community festivals, which have grown in popularity during the last 20 years both domestically and abroad, the research remains surprisingly limited. However, being part of what is being characterised as a global phenomenon, referred to as the ‘festivalization of culture’ (Woodward, Bennett, and Taylor Citation2014), some important studies have emerged. One important study is Michelle Duffy’s (Citation2005) ‘Performing Identity within a Multicultural Framework’, which from an Australian context brings attention to the multicultural music festival as a place for ‘cultural practice … in which fluid and complex meanings are generated’ (686). As one of the first to highlight the experiences of individuals’ identity construction, Duffy challenged the research field’s primary orientation towards the communal aspects of multicultural festivals (economic, social, and political). Other relevant examples are Insun Lee’s (Citation2015) visitor-benefit perspective from a South Korean context and McClinchey’s (Citation2017) study on performers’ emotive and sensuous experiences during two Canadian multicultural festivals. Although being outside the pedagogical sphere, these studies draw attention to the importance of studying multicultural events from the participant perspective.

Finally, on the specific issue of Kurdish transnationalism and diaspora, it is interesting to note the contribution of several empirical studies from the Nordic context during the last two decades, particularly associated with the works of Östen Wahlbeck (Alinia et al. Citation2014; Wahlbeck Citation2002, Citation1999). In this article, we draw theoretically from these studies. Underlining that our primary aim is to deepen our understanding of multicultural school events as potential spaces for identity construction, we assert that our study should also be relevant for the ongoing sociology- and anthropology-based discussion about Kurdish transnational and diasporic identity.

Theoretical perspectives on diaspora, transnationalism and representation

In recent years, the concepts of diaspora and transnationalism have become increasingly utilised among academics and others to understand contemporary societal changes due to growth in migration and processes of globalisation (Dufoix Citation2017; Vertovec Citation2009). As Vertovec (Citation2009, 2) has noted, it is no coincidence that the increased interest in diaspora and transnationalism parallels the growth of interest in migration and globalisation. While migration implies that many people have been forced to move from their home and cannot return for fear of persecution, globalisation has entailed an increased interdependence and interconnectedness of people and countries. The concept of diaspora, understood as groups who are dispersed from their homelands, often traumatically, therefore fits well with the transnational commitments and connections that immigrant communities attempt to maintain to their homeland and to similar immigrant communities in other countries of settlement.

However, although the concepts are related and may overlap, current understandings of diaspora and transnationalism often suffer from conflation, even with terms like minority and migration (Bhatia and Ram Citation2009, 145; Vertovec Citation2009, 128; Tölölyan Citation1996, 3). All of these terms are interlinked, but each encompasses specific processes of cultural transformation. Moreover, scholars have tended to over-use the term diaspora in order to explain a variety of research interests. As early as the mid-1990s, the editor of the academic journal Diaspora, Khachig Tölölyan (Citation1996), noted that the ‘discursive change in the three past decades has increased both the number of global diasporas and the range and diversity of the new semantic domains that the term “diaspora” inhabits’. The overuse as well as the insufficient study of the concept has lead Vertovec (Citation2009, 132) to state that the descriptive usefulness of the term has been threatened. Thus, in the following we turn to a focused discussion on how diaspora and transnationalism can be better understood, and how we will apply these terms in our study.

Diaspora derives from the two Greek words δια (dia: across) and σπείρω (speiro: to sow), namely ‘to spread across’, ‘to scatter’, or ‘to disperse’. Historically, the term may refer to different historical displacements and national catastrophes, like Babylonian captivity for the Jews, slavery for the Africans, massacres and deportation for the Armenians, and the Palestinian displacement during the formation of the state of Israel (Cohen Citation2008, 4). However, the Jewish experiences of living both voluntarily and involuntarily outside of Palestine has had significant impact on the understanding of the concept. As Vertovec (Citation2009, 130) noted, ‘the overall Jewish history of displacement has embodied the long-standing, conventional meaning of diaspora’. Hence, the contemporary use of diaspora carries a sense of dispersion of people from their homeland and is closely associated with suffering, loss, and unwilling separation. Moreover, scholars have emphasised at least three rather different ways of using the concept, which all have their root in the Jewish diasporic experience (Dufoix Citation2017; Vertovec Citation2009). First, the concept may refer to the scattering of people away from a geographical territory. Second, it relates to the community of people that lives outside of the home country. Third, it applies to the actual places where the dispersed communities are settled.

While these distinctions contribute to strengthen the term’s descriptive usefulness, Robin Cohen (Citation2008, 17) has suggested a set of features that may be helpful to clarify the concept further. He acknowledged that the history of the Jews will always be the starting point for a reflection on diaspora. However, it is also necessary to transcend the Jewish experiences. Expansion of the meaning of the term diaspora thus highlights what may be said to be common traits of identity for those communities sharing an experience of diaspora (see also Vertovec Citation2009, 133). Cohen (Citation2008, 17) established that a diaspora first involves the dispersal from an original homeland, often traumatically, to two or more foreign places. For the dispersed groups, this means that they often develop collective memories and myths about the place of origin. This includes the idealisation of location, national figures, history, and achievements. Furthermore, the groups will often strive for acceptance of their cause within the countries of settlement, based on a strong consciousness of common fate, history, and beliefs for the group. Finally, the sharing of a diasporic existence will often trigger a creativeness, particularly in tolerant host countries, giving the groups an opportunity to construct and define their historical experiences and to reinvent traditions like cultural and religious narratives, folktales, dances, songs, and food (Cohen Citation2008, 17). Experiences of diaspora will thus be constitutive for the way the group and the individuals understand themselves and the relation to others as well as to the homeland.

Cohen (Citation2008, 103) explained that ‘it is not invariably true that diasporas require homelands in a strict territorial sense, though they normally include a notion of “homeland” or a looser idea of “home” in their collective myths or aspirations’. The diasporic notion of homeland may thus be understood as an idea, referring to a real or imagined place. Thus, it is the actual dislocation and relocation in relation to an idea of a homeland that characterises the diaspora (Wahlbeck Citation2002).

These clarifications on diasporic identities lead us to the concept of transnationalism. According to Vertovec (Citation2009, 2), transnationalism refers to the increasing changes in ‘cross-border relationships, patterns of exchange, affiliations and social formations’ that characterise multicultural communities throughout Norway as well as in the rest of Europe. In this way, the concept clearly differs from diaspora the way we have elaborated it above. However, the actual ongoing communication and exchange of ideas and resources make the concept highly relevant for understanding the processes where diasporic identities are developed and formed. The concept of diaspora is therefore closely related to processes of transnational relations, social organisation, and formations of communities connected to the experiences of displacement (Wahlbeck Citation2002). Moreover, as we will show, the concept of transnationalism also highlights that a territorial place, such as Kurdistan, is not an internationally recognised sovereign country, but exists as an idea of a homeland comprising Kurdish people from four different states.

Vertovec (Citation2009, 3) stated that ‘new technologies, especially involving telecommunications, serve to connect […] networks with increasing speed and efficiency’. Thus, according to Vertovec, transnationalism portrays the evolvement of interconnections and relationships between people, beyond the boundaries of nation-states. For individuals sharing experiences of diaspora, new technologies make it possible to maintain closer and more frequent contact, connecting oneself with others and reshaping the memory of the place of origin. With reference to Arjun Appadurai and Carol Breckenridge, Vertovec (Citation2009, 6) noted that diasporas always leave a trail of collective memory, yet these memories are often fractured and must be reconstructed. Transnationalism understood as the ongoing exchanges of information, knowledge, and resources thus represents a possibility for rebuilding a common diasporic identity.

Thus, as transnationalism refers to the significance of information and communication technologies for interaction across national borders, it also includes the actual identity formation of people living their lives across international borders (Shaker Citation2018). An example is the Kurdish population with backgrounds from Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey who share a collective fragmented memory of a territory that they have a vision of reclaiming in the future. For the Kurdish diaspora, this means that transnational ties are shaped and reshaped, not only between the home and the host countries, but also between individuals from different nation states. Transnationalism thus captures the space in which cross-border social formation and identity construction operates.

Below, we present and analyse how such transnational diasporic identities are constructed in a particular educational context like a multicultural school festival. More specifically, we direct our empirical gaze towards the values and meanings that are negotiated and performed by a selection of the Kurdish participants through representations of heritage. Drawing on Blackledge, Creese, and Rachel (Citation2016, 8), we understand heritage ‘as the performance and negotiation of identity, values and sense of place’. Heritage is thus a process ‘in which social and cultural values, meanings, understandings about both the past and present are worked out, inspected, considered, rejected, embraced, or transformed’ (Blackledge, Creese, and Rachel Citation2016, 9). Accordingly, representations like food, traditional folk clothing, craft, music, and dance are imbued with history, identity, and continuity (Blackledge, Creese, and Rachel Citation2016; Hall Citation1997). Rather than being static representations of the past, they are resources from the past, bringing past into present and future (Deumert Citation2018). In our research, the study of representations allows us to explore the values and meanings expressed by the Kurdish parents. The representations are symbols or semiotic signs of values and meanings, linking the participants’ past, present, and future.

The selection of representations made by the participants is not neutral, however. Rather, the process of taking up certain resources must be understood in light of the specific diasporic situation of the Kurdish community (Blackledge, Creese, and Rachel Citation2016). Moreover, the interconnections and relationships between people in a transnational era provide a possibility for choosing, preserving, and transmitting representations as symbols of identity. We would therefore argue for a close interrelation between the concepts of diaspora, transnationalism, and representations.

The study’s design and methods

The research project is a qualitative study of a single case (Stake Citation2010), bounded in time and place, and designed to optimise the understanding of that case. We explored an international week at a primary school in Norway in a municipality with 12.5% immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrants, which is just below the national average of 13.8% (Statistics Norway Citation2017). The school aims at developing pedagogies for culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms, through efforts such as their annual international week. In another publication, we reported on the international week more in general (Dewilde et al. Citation2017). Here, we concentrate on the two-hour-long multicultural festival organised by the parent board in a sports hall connected to the school at the end of the international week (see also Basha and Kjørven Citation2018), and more specifically on the Kurdish stall. The multicultural festival is the climax of that week and attracts children and parents belonging to the school, representatives from the municipality’s school department, government officials such as the mayor, relatives and acquaintances from minority families, and even ethnic minority associations such as the county’s Kurdish association. Parents are encouraged to bring traditional dishes, dress in traditional folk clothing, and bring other artefacts from their countries of origin and engage in a dance performance with their children. Before the festival starts, the parent board sets up a stall for each nation, 40 in total, hangs up posters created by the students, and fixes up tables for food and artefacts. During the festival, participants walk from stall to stall, taste food, and mingle. The festival ends with a performance, where parents and children show their traditional folk clothing on the catwalk, play traditional music, and engage in traditional dance.

The Kurdish stall is interesting for two reasons. First, the Kurdish parents had put considerable effort in their stall compared to the participants in other stalls. In addition to serving typical dishes and dressing in traditional clothing, one of the parents, who is also the local leader of the Kurdish Cultural Society, contributed postcards, books, and self-made information sheets on Kurdish culture. In addition, other Kurds had travelled several hours to participate in the festival. Thus, the multicultural festival appeared particularly important for the Kurds. Second, as the Kurds are dispersed from their homeland and thus live in diaspora, the Kurdish parents are particularly interesting with regard to the issue of identity construction. In the event, they showed transnational commitment as they attempted to maintain their connection to their homeland in their new host country.

The collection of the material for this article was inspired by linguistic landscaping (LL) in an ethnographic tradition. Traditionally, LL studies have focused on linguistic signs such as posters, sales texts in shop windows and signposts. Over the last three decades, a broader perspective with roots in interdisciplinary work in semiotics (see, e.g. Barthes Citation1985) has emerged, now also including other semiotic modes such as images, artefacts, poems, maps, and signage (Shohamy and Waksman Citation2009). Jan Blommaert (Citation2013) has emphasised that LL holds both a descriptive and an analytical potential. In descriptive terms, LL goes beyond people’s social behaviour as it considers the physical spaces in which these people dwell and leave their mark. Analytically, these physical spaces are perceived as social, cultural, and political spaces. As Blommaert (Citation2013, 3, italics in original) stated, ‘a space […] is never no-man’s land, but always somebody’s space; a historical space, therefore full of codes, expectations, norms and traditions; a space of power controlled by, as well as controlling, people’. LL thus becomes a diagnostic tool of social, cultural, and political structures inscribed in the semiotic space under scrutiny. In this article, we consider the investigation of the semiotic landscape in a multicultural festival to be fruitful to exploring transnational diasporic representations of identity. That is, we view participation in a multicultural festival as a social action in which Kurdish participants exercise identity construction and agency in engaging in representing their homeland.

In terms of data, as part of a larger fieldwork, the team observed approximately three hours, that is, the multicultural festival as well as a half an hour before and after. We wrote field notes, took pictures of semiotic signs, and video recorded the stage performances. In addition, we had many field conversations with participants during the event and conducted semi-structured interviews with two representatives of the Kurdish stall about the event and the signs six weeks later. One of them was a Kurdish mother, whom we call Nazdar, who had a special responsibility for the Kurdish stall this year. The other was the leader of the Kurdish Cultural Society for the county, whom we call Ara. The school’s bilingual Kurdish assistant helped us establish contact with both representatives prior to the fieldwork and acted as a translator and cultural broker (see, e.g. Duran Citation2019) between Nazdar and us when necessary. During the interviews, we asked general questions about their role in the multicultural festival, before asking them to comment on a selection of pictures and video recordings of the stage performances. A Kurdish research colleague transcribed both interviews and translated them into English with annotations when necessary. For this article, we draw on the pictures related to the Kurdish stall (25 in total), mainly capturing signs of culture, language, religion, and nations as well as of the stall as a whole, and on the video recording from the performance. Equally important are our field notes and transcripts from the interviews with the Kurdish representatives.

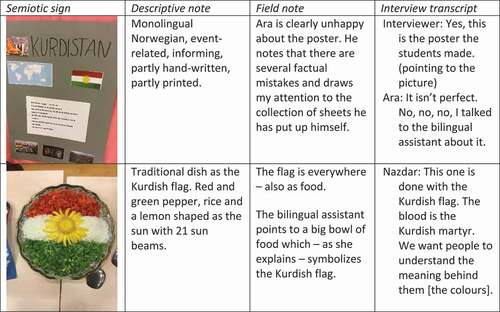

Data analysis took place in two stages. In the first phase, we made an overview of the representations (semiotic signs) specifically connected to the Kurdish stall based on our visual data (Blommaert Citation2013, 50–62). In the second phase, we added layers of complexity to the signs by drawing on field notes and interview transcripts. We created a Word document with four columns. In the first column, we pasted a picture of a cultural, linguistic, religious, and/or national sign. We used the second column for our own notes, the third for field notes, and the fourth for conversations and transcripts from the interview with the Kurdish parents. Here are two examples ():

Our analyses were guided by abduction (Alvesson and Kaj Citation2017), which meant that we continuously oscillated between our data and theoretical concepts. Each member of the team did a first analysis which was then presented and jointly discussed by the team. Guided by our theoretical framework, we identified two core themes with regard to the Kurds’ identity construction. These core themes were inward identity construction consolidating the Kurdish diasporic community and outward identity construction when striving for acceptance of the greater cause: the struggle for a homeland and an independent state. We will further elaborate and discuss these core themes below.

Fieldwork designs are open and responsive to the contingency of the context, which makes research ethics a continual concern (Copland and Creese Citation2015; Fangen Citation2010). The project has been approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Ethnic, political and religious affiliations are generally regarded as sensitive information, and thus also in this study. Both key participants were informed about the aims of the study prior to the data collection and signed forms of consent, including permission to interview and observe them, as well as take pictures of cultural artefacts during the festival. This consent was orally renewed during data collection. The Kurds participating in the dance performance gave their oral consent through the bilingual Kurdish assistant to be video recorded. In order to secure confidentiality, we asked both key participants to choose pseudonyms for publication, and we have chosen not to describe the locality of the school in detail.

Doing research that involves the production of knowledge about Kurds and Kurdistan, the question of independent critical research became particularly important to the study. As the Kurdish conflict is highly politicised and conditioned by practices of nation-building, we were aware of the fact that Kurdish nationalists may underplay the ethnic heterogeneity of Kurdistan and that researchers run the risk of being spokesmen of Kurdish nationalism. In our study, however, we believe to have accounted for this risk by continuously discussing issues of independence and critical distance when collecting and interpreting the data. Moreover, the primary focus of the study has been descriptive, that is to describe the construction of transnational diasporic identities at a school festival, using the Kurdish participants as an example. This implies that questions of whether Kurdistan should be recognised as an independent entity lies beyond the scope of this article.

Restructuring a collective memory

In this part of the study, we focus on the constructions of parents’ identity at the multicultural school festival. More specifically, we identify how the Kurds at the festival contributed to the creation of a collective memory which took form as an inward and outward construction of identity among the participants. As emphasised in the elaboration on diasporic identities, experiences of exile, dispersion, and loss are often a resource for mobilisation. According to Cohen (Citation2008, 17), the tension between national, transnational, and ethnic identities often makes the diasporic identity a creative one. To recognise the ‘positive virtues of retaining a diasporic identity’ (Cohen Citation2008, 7) will thus be to draw attention to how the Kurdish diaspora mobilises a collective identity by restoring fragmented memories.

In the further analysis, we explore how this collection and displaying of fragments relate to the reconstruction of a collective memory. As we will show, this mobilisation of Kurdish identity is not restricted to the consolidation of the Kurdish community in the host country or to co-ethnic Kurds in other countries. The restoration of a collective memory is also important for the participants striving for acceptance for their cause in the wider society. In this way, the construction of identity at the multicultural school festival is both an inward and an outward process.

Inward identity construction – consolidating the Kurdish diasporic community

From the outset, the festival’s many stalls where minority parents were present appeared retrospective in its approach, that is, the semiotic signs chosen by the participants pointed to history, traditions, and customs. The primary aim thus seemed to be to confirm long-established national and ethnic customs through event-related signs such as traditional dishes, traditional clothing, flags, and handicrafts. To illustrate, when Nazdar spoke of dolma, a stuffed vegetable dish highly appreciated among Kurds, she said: ‘We inherited it from our forefathers’. Shortly afterwards, however, she linked dolma to the present, continuing: ‘If you don’t have this food, you are not counted as Kurds, totally! You know we hear this very often’. Obviously, dolma is not just any food, nor does it represent just an exotic, historic curiosity with fixed meanings of content, as suggested by critics of multicultural school festivals (Hoffman Citation1996; Øzerk Citation2008). One should note that dolma is not an exclusive Kurdish dish but is a well-known part of the Middle Eastern cuisine. Viewed as a visual and a sensual sign, dolma selects everyone who has knowledge of the Middle Eastern cuisine (see Blommaert Citation2013). The interviews, however, highlighted that dolma has a clear demarcation; between Kurds and those ‘not counted as Kurds’. For the Kurdish parents at the festival, dolma seems to perfectly serve a consolidating role for Kurds in the diaspora, as a manifestation of the link between the historic home in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, or Syria, and the homeland idea of transnational Kurdistan.

The traditional folk clothing with matching accessories (jewellery in particular) played a similar role at the festival. Even more so than with dolma, the folk clothing appeared as visible representations of the Kurds’ transnational origin. Nazdar explained: ‘Well, there are differences, different styles. Like, for instance, this one is mine [pointing at a picture]. It is from Kurdistan [i.e. Northern Iraq]. That one is from Iran. Kurdish people in Iran use that style. The other style is from Kurdistan Turkey’. Again, a clear demarcation was made, as Nazdar continued: ‘People who are with me never ask [about my origin], in any Kurdish occasions. They are clever, and they know where others come from’. More precisely, a demarcation is made between those who ‘know’ and those who do not ‘know’, the latter later spoken of as ‘strangers’ or more specifically as ‘Arabic’, as ‘someone [i.e., a non-Kurd] from Iran or Turkey’. As objects evoking national and ethnic consciousness (Cohen Citation2008, 17), the folk clothing appeared as particular powerful signs for consolidating the Kurdish diasporic community, and thus ‘as affordances that have a cultural, social and political dimension’ (Blommaert Citation2013, 43). As a semiotic sign, traditional clothing also selects other participants than the Kurds, especially when in co-occurrence with other Kurdish signs such as dolma and the Kurdish flag, which we will address. Collectively, these signs demarcate what it means to be Kurdish.

Throughout the festival, the most visible and prominent representation was the Kurdish flag. The flag was everywhere, used to decorate food and handicrafts (see ), to cover one of the main walls of the stall, to illustrate information posters made by students and, not least, to serve as the centrepiece artefact for the Kurds performing on stage. Thus, appearing in various creative forms, the flag functioned as a representation that consolidated a collective memory (see Cohen Citation2008; Vertovec Citation2009), a memory which in particular emphasised the Kurds’ many historic and present sacrifices, ‘the blood of the martyrs’, as Nazdar put it when pointing at the red colour of the flag.

Giving the nature of the flag as a symbol, it has an obvious outward side. Being aware of the formal status of Kurdistan, the flag appears as the foremost symbol of their struggle for a homeland and an independent state. According to Cohen, an important feature of diasporic identity is the effort made to gain acceptance for their cause (Cohen Citation2008, 17). As we will see in the following, this is certainly true for the Kurds at the multicultural festival.

Outward identity construction – striving for acceptance for their cause

In preparation for the multicultural school festival, a group of grade 5–7 students in the school had made a large poster in Norwegian with facts and pictures for each stall. With regard to the poster portraying Kurdistan, the students had glued a sheet of paper with six facts on Kurdistan in the middle. In addition, they included a world map indicating Kurdistan, the Kurdish flag, and four pictures symbolising the capital Hawler, people in traditional folk clothing, Kurdish New Year, and a landscape, respectively (see ). This poster may be found to portray Kurdistan and Kurdish culture as bounded and stable entities, in line with the critique of the research literature (Hoffman Citation1996; Øzerk Citation2008). However, the choices will never be neutral, but rather embedded in larger societal discourses. Ara was unhappy with the poster, something he voiced to one of the members of the research team.

In the follow-up interview, Ara repeated that ‘it [the poster] wasn’t perfect’, adding that he had confronted the bilingual Kurdish assistant who had explained that it was the students’ work. The poster stated that Kurdistan was situated in northern Iraq, ‘which isn’t true’, according to Ara. He also disagreed with what was written about the Kurdish language, indicating that it was more complicated than consisting of three dialects, and he argued that kulicha is not a cake but a kind of bread. He concluded, ‘I’ve talked to them about it’. Nazdar first asserted that the poster was ‘perfect’ before nuancing:

… but if you focus on the picture, you’ll find this is the part of Kurdistan that we came from, the mountain area, and I’m sure that they will make better and bigger things next year. […] but if they told me before I could at least show better things, […] like waterfalls in Kurdistan.

For people living in diaspora, collecting memories and myths from the homeland is important, often idealising locations, national figures, history, and achievements (Cohen Citation2008; Vertovec Citation2009). It is clear that it was important to Nazdar and Ara which fragments of the collective memory of Kurdistan were chosen for the multicultural school festival. Nazdar’s wish to have a picture of waterfalls rather than the mountain area also illustrates that the landscape serves as an important point of cultural reference, envisioning an ideal, romantic image of what constitutes their identity. Ara had not been aware that the students would make a poster. Instead, he had displayed nine sheets of paper in plastic sleeves on one of the stall’s walls. Each paper had information on Kurdistan printed in Norwegian. During the interview, he explained that he used the sheets in the annual Newroz (Kurdish New Years) celebration at a local museum. Even though the sheets were event-related signs, the plastic sleeves and the fact that they were printed gave them certain permanence. Their function was to recruit participants to the stand and inform them about Kurdistan, that is, about the food, language, religion, flag, map, and core values. The use of the Norwegian language gave them a wide semiotic scope, potentially targeting and including a broad audience, since Norwegian was the spoken lingua franca (common language) among the highly diverse participants of the event. Blommaert (Citation2013, 47) argued that signs in an event raise questions about agency. We will claim that through Ara’s additional information sheets, the Kurdish community was able to mobilise a strong collective, agentive identity (see Cohen Citation2008).

In addition to the sheets, Ara had brought postcards with pictures accompanied by a bilingual caption in Kurdish (Sorani) and English and two hardcover children’s books in Kurdish. Whereas Kurdish first and foremost targets a single audience, English again illustrates the wider semiotic scope, thus emphasising the outward identity construction. The books were translations of the Norwegian children’s classics Karius og Baktus (Karius and Baktus) and Folk og Røvere i Kardemommeby (When the Robbers Came to Cardamom Town) by Thorbjørn Egner. Arguably, the usage of the Kurdish language would target a small audience (i.e., only Kurdish speakers). However, these books were well-known stories translated from Norwegian, which gave the books legitimacy to a larger audience. In terms of stratification between languages, Norwegian was the unchallenged leading language in the event, but the books connected the Kurdish and Norwegian languages, giving Kurdish more prominence and permanence in the event. We see the use of the translated children’s books as a creative act of reaching out to Norwegian society while striving for acceptance (Cohen Citation2008, 167).

The Kurdish community’s striving for acceptance and sympathy for their cause was visible not only in the signs in the stall, but also in their practices during the event. Before the festival ended, Ara asked the parent in charge of the stage performance if he could make a speech. He got the permission and in our field notes, we recorded:

Ara and the mayor are in deep conversation before entering the stage. Ara starts by saying that the municipality is diverse and colourful, and so is the school. The multicultural festival is organized every year, and multicultural parents contribute with food, dance songs, and cultural materials. Multiculturalism is an enrichment for the municipality and for the school. Ara ends by saying: “I wish to say something about the fight against IS. Kurdish military forces called Peshmerga fight hard against IS [Islamic State]. Thanks to Peshmerga who stopped the power expansion of IS. Peshmerga fight for the security of the world community, for safety, democracy and freedom.” When Ara has finished talking, the mayor addresses the audience saying that the school does great work with regard to multicultural education. People clap, and not much later participants start taking down the stalls and leave the hall.

As the field notes illustrate, Ara used the opportunity to praise the municipality and the school for their work and multicultural profile, again connecting to the host country. However, he also praised Kurdish military forces for battling against IS and contributing to the security, safety, democracy, and freedom of the world community. Linking the municipality and the school to the Kurdish forces was not only a powerful statement which equated the work of municipality, the school and Peshmerga, but also a political statement and an idealisation of Peshmerga’s achievements as a resistance movement (see Cohen Citation2008, 17). As Blommaert (Citation2013, 3) argues, ‘physical space […] offers, enables, triggers, invites, prescribes, proscribes, polices or enforces certain patterns of social behaviour’. It is thus possible to interpret Ara’s strong political content in his public speech as an expression of the social space. Moreover, we see a link between the appreciation of and fight for democracy and freedom in the speech and political content present in the semiotic event-related signs in the stall, as explored in the previous section.

Contrary to the articulated political content of the speech, Ara emphasised during the interview that the multicultural festival was not a place for politics and conflict: ‘[It is] important to put it [politics and conflict] on the shelf and be together and show your culture, integration and inclusion. […] And forget the past with different nations at war. Solidarity’. When we asked about his relationship to people from Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria in the event, he replied, ‘We shouldn’t talk about why with that person from Iran. […]. That’s forbidden at school that day. I don’t want to talk to about it with him, and hurt him, because he’s a refugee just like me’. An important aspect of diaspora to Cohen (Cohen Citation2008, 7) is mobilisation of a collective identity in terms of a solidarity with co-ethnic members in other countries. Here, however, we see how Ara built solidarity with co-refugees in similar diaspora situations, what can be framed as a cosmopolitan consciousness. The restoration of a collective memory also seemed to include a global solidarity with other participants at the festival with experiences of displacement and transnational existence.

In summary, the displayed and performed cultural artefacts were inward-oriented, as means that in different creative ways linked the historic home of Kurds to the present diasporic experience and the idea of homeland Kurdistan. In terms of outward identity construction, an analysis of the representations shows that the representatives of the Kurdish community appeared to be self-confident and able to mobilise a collective identity. The festival was used to inform participants about Kurdish culture, but also about their battle for an independent state and values such as solidarity and democracy. They sought further legitimacy by connecting semiotic signs and values to multicultural work done in the municipality and in school. Thus, it becomes more comprehensible why the Kurdish participants spoke so warmly and enthusiastically about the festival, stating that it was ‘very important’ and ‘something big for everybody’ as well as representing ‘a great day for all Kurds’. Obviously, for these parents, the festival represented an important opportunity to express Kurdish identity.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we set out to explore how a multicultural school festival becomes a space for transnational and diasporic identity construction, using Kurdish parents as an example. As noted earlier, previous research on multicultural school events has been theory-driven and sceptical. Our empirical study nuances this criticism. For the Kurdish parents involved, the festival appeared as a creative space that at times even challenged the perceived and unwritten code of not promoting political content, thus reflecting a strong sense of agency.

With regard to the construction of diasporic identities, the sense of loss created by the traumatic experiences of being forced from their homeland formed a strong connection between the participants. First, it created a commitment to reconstruct a collective memory of fragmented traditions and pass it along to future generations. For the parents, it was important to create a sense of belonging to the Kurdish group using representations of collected heritage. Second, experiences of loss led the participants to strive for a wider acceptance of the Kurdish struggle for a homeland and an independent state, which in the study took form as an outward-oriented appearance. Although the participants were clear that the school event was a non-political arena, the festival provided a space for the participants to reach out to the Norwegian society and to relate the Kurdish political struggle for independence to a solidarity with other refugees living with similar experiences. While construction of inward identity accommodated the Kurdish participants to life in exile, outward identity mobilised global sympathy for the dream of ending it (Gabaccia Citation2003). Hence, we will claim that the present study displays a complexity of identity constructions at the multicultural school event, which prior research largely has overlooked.

In order to promote such events as arenas for international awareness, social cohesion and inclusion, schools need to be aware of and address the complex content and functions that multicultural events may hold. As a matter of encouraging the polyphony of participant voices controversial issues should not be silenced. As we have seen in this study, being Kurdish at the multicultural school festival was for one of the parents also about presenting a political message, striving for acceptance for a cause. For schools to acknowledge this part of outward identity construction may contribute to evoking the invigorating, imaginative, and empowering sides of a multicultural event, hence addressing the criticism of such events as superficial, harmonising and apolitical (Hoffman Citation1996; Øzerk Citation2008). As critics of such events have argued, focusing on the presentation and acquisition of lexical information about different cultures may easily lead to essentialist conceptions and strengthen stereotypes and prejudices. Based on the premise of allowing the participants to attend with different voices and different ways of representing their nations of origin, there is a pedagogical potential for school in encouraging participants to explore the complexity of meaning of the displayed representations, as also the broad semiotic analysis of our article has shown. We argue that this could challenge conventional ways of understanding nations, cultures, and people in diaspora.

Finally, parents are central actors in these events. Future research should further examine multicultural events from the perspectives of children and young people who are a core target group and who may hold different views than their parents. Important issues to explore would be how they construct identities and learn at the events, and how they reflect on culture, language, religion, and nation as matters of identity construction and learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joke Dewilde

Joke Dewilde is an Associate professor of multilingualism in education at the University of Oslo and Adjunct Associate professor of Education at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her recent work is on bilingual teachers, literacy and identity, and multicultural events.

Ole Kolbjørn Kjørven

Ole Kolbjørn Kjørven is an Associate professor in Religious Education at the Faculty of Education at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses on religious and multicultural education.

Thor-André Skrefsrud

Thor-André Skrefsrud is Professor of Education at the Faculty of Education at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. His research interests include multicultural education and educational philosophy.

References

- Alinia, M., Ö. R. Wahlbeck, B. Eliassi, and K. Khayati. 2014. “The Kurdish Diaspora: Nordic and Transnational Ties, Home, and Politics of Belonging.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 4 (2): 53–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2014-0007.

- Alvesson, M., and S. Kaj. 2017. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London, UK: Sage.

- Banks, J. A. 1988. Multiethnic Education: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Barthes, R. 1985. “Rhetoric of the Image.” In The Responsibility of Forms, edited by R. Barthes, 32–51. London, UK: Fontana Press.

- Basha, S., and O. K. Kjørven. 2018. “Mangfold I praksis. En studie av en flerkulturell festival i skolen [Diversity in Practice. A Study of a Multicultural Festival in School].” In Å være lærer I en mangfoldig skole. Kulturelt og religiøst mangfold, profesjonsverdier og verdigrunnlag [To Be a Teacher in a Diverse School. Cultural and Religious Diversity, Professional Values and Ethical Foundation], edited by E. Schjetne and T.-A. Skrefsrud, 102–112. Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Bhatia, S., and A. Ram. 2009. “Theorizing Identity in Transnational and Diaspora Cultures: A Critical Approach to Acculturation.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33 (2): 140–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.009.

- Blackledge, A., A. Creese, and H. Rachel. 2016. “Protean Heritage, Everyday Superdiversity.” Working Papers in Translanguaging and Translation (WP 13).

- Blommaert, J. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes. Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Cohen, R. 2008. Global Diasporas. London, UK: Routledge.

- Copland, F., and A. Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Deumert, A. 2018. “The Multivocality of Heritage – Moments, Encounters and Mobilities.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Superdiversity: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, edited by A. Creese and A. Blackledge, 149–164. London, UK: Routledge.

- Dewilde, J., O. K. Kjørven, A. Skaret, and T.-A. Skrefsrud. 2017. “International Week in a Norwegian School: A Qualitative Study of the Participant Perspective.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 62(3): 474–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306800

- Duffy, M. 2005. “Performing Identity within a Multicultural Framework.” Social & Cultural Geography 6 (5): 677–692. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360500258153.

- Dufoix, S. 2017. The Dispersion: The History of the Word Diaspora. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

- Duran, C. S. 2019. “‘I Have Many Things to Tell You, but I Don’t Know English’”: Linguistic Challenges and Language Brokering.” In Critical Reflections on Research Methods: Power and Equity in Complex Multilingual Contexts, edited by D. S. Warriner and M. Bigelow, 13–30. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Fangen, K. 2010. Deltagende Observasjon [Participant Observation]. Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

- Gabaccia, D. R. 2003. Italy’s Many Diasporas. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hall, S. 1997. The Work of Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Hoffman, D. M. 1996. “Culture and Self in Multicultural Education: Reflections on Discourse, Text, and Practice.” American Educational Research Journal 33 (3): 545–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312033003545.

- Lee, I. S. 2015. “Understanding Motivations and Benefits of Attending a Multicultural Festival.” Tourism Analysis 20 (2): 201–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.3727/108354215X14265319207470.

- May, S., and C. E. Sleeter, eds. 2010. Critical Multiculturalism: Theory and Praxis. New York, NY: Routledge.

- McClinchey, K. A. 2017. “Social Sustainability and a Sense of Place: Harnessing the Emotional and Sensuous Experiences of Urban Multicultural Leisure Festivals.” Leisure/Loisir 41 (3): 391–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2017.1366278.

- Niemi, P.-M., and R. Hotulainen. 2016. “Enhancing Students’ Sense of Belonging through School Celebrations: A Study in Finnish Lower-secondary Schools.” International Journal of Research Studies in Education 5 (2): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2015.1197.

- Øzerk, K. 2008. “Interkulturell Danning i en Flerkulturell Skole: Dens Vilkår, Forutsetninger og Funksjoner [Intercultural Bildung in a Multicultural School: Its Conditions, Requirements and Functions].” In Fag Og Danning: Mellom Individ Og Fellesskap [Subject and Buildung: Between Individual and Community], edited by P. Arneberg and L. G. Briseid, 209–228. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Shaker, S. F. 2018. “A Study of Transnational Communication among Iranian Migrant Women in Australia.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (3): 293–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1283078.

- Shohamy, E., and S. Waksman. 2009. “Linguistic Landscape as an Ecological Arena: Modalities, Meanings, Negotiations, Education.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by E. Shohamy and D. Gorter, 313–331. London, UK: Routledge.

- Stake, R. E. 2010. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Statistics Norway. 2017. “Immigrants and Norwegian-born to Immigrant Parents.” https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef

- Tölölyan, K. 1996. “Rethinking Diaspora(s): Stateless Power in the Transnational Moment.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 5 (1): 3–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dsp.1996.0000.

- Troyna, B. 1993. Racism and Education: Research Perspectives, Modern Educational Thought. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Vertovec, S. 2009. Transnationalism, Key Ideas. London, UK: Routledge.

- Wahlbeck, Ö. R. 1999. Kurdish Diasporas: A Comparative Study of Kurdish Refugee Communities. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Wahlbeck, Ö. R. 2002. “The Concept of Diaspora as an Analytical Tool in the Study of Refugee Communities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28 (2): 221–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830220124305.

- Watkins, M., and G. Noble. 2019. “Lazy Multiculturalism: Cultural Essentialism and the Persistence of the Multicultural Day in Australian Schools.” Ethnography and Education 14 (3): 295–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2019.1581821.

- Woodward, I., A. Bennett, and J. Taylor. 2014. The Festivalization of Culture. Surrey, England: Ashgate.