ABSTRACT

Grounded in the universal right to education, this article considers the collective findings of a selection of projects, conducted primarily by researchers from the SIRIUS Policy Network on Migrant Education arguing for a holistic approach to the educational inclusion of Newly Arrived Migrant and Refugee Students (NAMRS). The right to education demands access for all, including NAMRS, to a quality education that meets each individual’s learning needs, and supports and develops their own personal learning pathways. Moreover, a rights-based educational model should empower NAMRS to resist prescribed roles and identities, to define their own past, and to liberate their visions of their futures from any constraints associated with their migration, so they can take ownership of the development of their future selves as active citizens of local, national and the global communities. Associating inclusive education with the removal of all barriers to the attainment of this educational aim, the article details a holistic framework for educational policy and practice that first considers, and then alleviates, the impact of a diverse range of factors on NAMRS’ right to a quality education. Furthermore, the discussion explores the implications of the adoption of such a holistic model to guide educational practice, research and policy making when educating NAMRS.

Introduction

In order to highlight the urgency of the role that education has to play in the social inclusion of Newly Arrived Migrant and Refugee Students (NAMRS), many reports and research papers published in the beginning of the last decade make references to the exponential increase of the number of refugees and migrants worldwide (e.g. Human Rights Watch Citation2015; Thomas Citation2016). The same point is frequently used to explain the pressure on schools and the expectation that is being placed upon them to support the educational inclusion of NAMRS. The starting point of the discussion in this paper is different in that the need for appropriate educational responses is not seen as the response to an emergency but to the legal obligation of all European countries to secure the right of every child to education. Educational inclusion on the other hand is seen as a societal objective which does not depend solely on schools to fulfil. This is not only a reference to the significance of the contribution of non-formal education in educational and social inclusion of NAMRS (Kakos and Teklemariam Citation2021, Citation2022; Van der Graaf et al. Citation2021) but a consideration of the effects on educational inclusion of factors that may sit outside education. Expanding the well-argued position in literature about the significance of education on social inclusion, one suggestion that leads the development of the holistic model integrates findings from various studies which show that the reciprocity of this relationship and the effects of social exclusive experiences on the schools’ efforts to establish an inclusive environment for NAMRS.

Starting from an examination of education as a human right, the discussion will examine the numerous factors that exist outside education but determine the educational experiences of NAMRS. The discussion will then move on to the presentation of the suggestion for a holistic understanding of educational inclusion and an exploration of some implications for research, policy and practice.

The right to education

The right of every child to education is arguably one of the most widely recognised human rights and has been repeated in several key Declarations and international conventions (see: Article 26 of the UN General Assembly Citation1948, Article 2 of the European Convention of Human Rights 1958; Article 28 of the; UN General Assembly Citation1989). However, also recognised is the gap between the positive recognition of the right to education and the negative reality faced by many children (Lee Citation2013). Illustrative of this is the inclusion of the eradication of illiteracy in the UN’s Millennium Development Goals and more recently the Sustainable Development Goals (2015–2030) which make explicit reference to the need of governments to guarantee quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all (United Nations Development Program, SDG #4). Also recognised is the fact that NAMRS constitute a large group of children whose right to education is compromised. Indicative of this is the findings from the UNHCR report in 2019 which showed that from the 7.1 million refugee children of school age, 3.7 million – more than half – did not attend school (United Nations High Commission for Refugees Citation2019). The situation is even grimmer if we consider that access to schools does not always guarantee access to quality education which meets the learners’ needs. Yet an understanding of inclusive education which is based on education as a right and the central role of schools in fulfiling this is not meaningful without consideration of the quality in educational provision.

Seeing it from the above angle, the European Convention of Human Rights bears particular significance. This is because together with its ratification, countries have also accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of its main supervisory body, the European Court of Human Rights and with the right of all citizens to take a complaint against the State under the Convention. The Convention does not make specific reference to the right of education as an individual right, but it recognises the equality of all persons, and that educational provision should not contradict the families’ philosophical and religious convictions (Article 2). This note, apart from bearing particular significance for NAMRS and their families it is also a clear demonstration that education as described in the convention is not to be understood as standardised and uniform. It is in this recognition that education as a right can and indeed needs to be tailored to suit individuals’ needs that one can recognise one important aspect of what many authors and international organisations mean when they refer to the right to ‘quality’ education (Aguilar and Retamal Citation2009; United Nations High Commission for Refugees Citation2011; Thomas Citation2016; among others).

Departing from the above point of view and considering education as a lifelong process of personal development, the recognition of the right to quality education can be seen as the recognition of every individual in receiving appropriate support and guidance to develop and follow personal learning pathways towards educational goals that respond to their aspirations and the vision of self in the present and in the future. The reference to ‘appropriate support and guidance’ responds to individuals’ right to access support that responds to their learning preferences and empowers them to contribute meaningfully and equally in social, economic and political processes and in the sustainable prosperity of all communities that they participate in, including the global community.

A key element, therefore, of the right of access to quality education is the recognition of the learning styles, the background and the personal aspirations, identities and goals in the design and access of educational provision. Importantly, this educational provision is not of a finalised product but the skilling and empowerment of individuals to develop their own, personal educational process and the ability to contribute to an inclusive society with their ‘capacity to live together with full respect for the dignity of each individual, the common good, pluralism and diversity, non-violence and solidarity, as well as their ability to participate in social, cultural, economic and political life’ (United Nations Citation1995, 39).

Appreciating the complexity of needs and provision

The volume and depth of research makes it difficult to justify the oversimplification that is often reported on the interpretation of NAMRS’ needs, such as the misinterpretation of language needs as indicative of impaired cognitive abilities or capacity to learn (Lopes-Murphy Citation2020). Frequent are also the reports about the lack of appreciation of the risks and challenges that are associated with the design of appropriate educational provisions which often result to segregation and exacerbation of the difficulties that they try to address (Bacakova Citation2011). This is in fact a rather common issue in the interpretation of inclusive education in policy making and in practice when it associates the development of ‘inclusive’ educational programmes with the provision of ‘extra’ or ‘additional’ support. The interpretation is revealing of the adoption of a standardised model of education based on the ‘normalisation’ or ‘mainstreaming’ of the educational profiles of most students, a model which has long been recognised as disadvantaging learners from certain backgrounds and therefore effectively discriminatory (Malkova Citation1989; Powell and Tutt Citation2002; Razer, Friedman, and Warshofsky Citation2013). Moreover, and seen from such angle, the provision of ‘extra’ or ‘additional’ support is itself an exclusionary practice which disenfranchises those whose inclusion is supposed to facilitate. This is particularly the case for refugee students (Bacakova Citation2011; Koehler et al. Citation2019) whose complex ‘additional’ or ‘special’ educational needs can relate to and stem from undesirable, sudden, unplanned, often violent change in their lives and traumatic experiences.

Looking at research literature reporting on projects conducted by SIRIUS (Koehler et al. Citation2019; Sharma‐Brymer et al. Citation2019) we can recognise that there are three major types of challenges that NAMRS usually face in the new educational environments:

The interruption of educational experiences and the unpreparedness for the educational transition. Difficulties relevant to this include NAMRS’ limited knowledge and understanding of the new educational system; the difficulties in translating (linguistically and culturally) the educational profiles of NAMRS into the new educational provisions, including the lack of evidence of prior learning and academic achievements. The difficulties are further exacerbated by schools’ difficulties in supporting multilingualism and unpreparedness in embracing diversity and in supporting intercultural pedagogies.

The forced departure, the transition, the constant movement and the delays in settlement (physical, legal and emotional). Traumatic experiences before and after the departure of students and of their families and the unsuitability of reception systems in host countries, including the systems that determine the legal status of MAMRS and of their families, housing and access to social support are all challenges of this type.

Educationally exclusive practices in the host countries. These can include educational policies and practices that are based on unsystematic provision that is not monitored or evaluated; Lack of mechanisms to support transition; Practices that target students in isolation from their families and with no recognition of their background; etc.

Within the context of the above conditions and challenges, NAMRS are required to claim not just a space in the new social and educational environment but to negotiate new identities which are invariably located in the broad space of ‘otherness’ to a ‘mainstream’, ‘local’ or prevailing one. In the negotiation of these new identities, in the resistance to their attribution by their peers, teachers and others or in their adoption and re-interpretation lies one of the major sources of resilience but also of trauma for NAMRS. In respecting and supporting this process of negotiation and construction of new identities while at the same time detecting and serving their needs lies arguably one of the major challenges in designing programmes and interventions for their educational inclusion. In terms of the appreciation of such needs and the support that is required the major responsibility of host societies is the development of the appropriate sensitivity in detecting and then the ability to eradicate all forms of racism and discrimination. In terms of recognising and addressing the needs of NAMRS, societies can utilise relevant research in which we can recognise three types of needs:

Social (including language, development of new belongings to social groups, unfamiliarity with codes of conduct and presentation of self, poverty, etc.);

Emotional (Dealing with trauma, isolation, stress, uncertainty and vulnerability);

Educational (language and other difficulties in accessing the curriculum, understanding of new educational system and school routines, rules and regulations, adjustment to new educational methods, translation of existing educational profile to the new educational reality, etc.).

It is in the typology above that becomes clear that the purely ‘educational’ needs are neither the only nor arguably the most important that affect the educational inclusion of NAMRS. Research conducted by SIRIUS and by others has shown how vulnerable this endeavour is to factors that sit outside education and are not in control of schools. These include the long-term effects of traumas related to their journey and of their stay in reception centres and camps (Sidhu and Taylor Citation2012); current circumstances such as living conditions (Koehler et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Sharma‐Brymer et al. Citation2019), their sudden decent to poverty (Meda, Sookrajh, and Maharaj Citation2012), the uncertainly about their legal status and the negotiations with authorities (Koehler et al. Citation2018), their overall mental health (Sirin and Rogers-Sirin Citation2015) to name a few particularly significant ones. Generally, what is clear from research is that the educational inclusion of NAMRS and especially of refugee and asylum-seeking students is dependent upon the capacity of host societies and systems to cater for multiple and complex needs (Rutter and Stanton Citation2001; Rutter, Citation2001) which require coordination of agencies and provision (Arnot and Pinson Citation2005). It is for the above reason that a key and often missing element of educational inclusion, particularly of refugee and migrant students is not always resources but the implementation of appropriate methods based on the understanding of these students’ educational needs.

Educational and social inclusion

Approaching education from a Human Rights perspective could render obsolete the argumentation about the purpose of educational inclusion. However, this discussion is still meaningful to fully appreciate the expectations that societies can attribute to education for the social inclusion of NAMRS. Research has indeed already shown the strong associations between academic qualifications, employment and social inclusion, the significance of schooling experiences in socialisation and the sense of belonging (M. Kakos, Müller-Hofstede, and Ross Citation2016) but also the contribution of education in the development of particular skills that facilitate inclusion such as language learning (Kambel Citation2019) and the understanding of social rules, and systems in the host society (Koehler et al. Citation2018). Also clear is that educational engagement is significant not only for the social inclusion of the learners (pupils, college students, etc.) but also for the families that they are indirectly involved in this process by supporting pupils and students.

The role of education in the prosperity of individuals and societies cannot be underplayed. Its association with social mobility is unquestionable (Brown, Reay, and Vincent Citation2013) and so is the significance that many migrant and refugee families attribute to education of their children. In fact, NAMRS’ resilience and motivation to secure a better future allow them to overcome difficulties and achieve high when they receive appropriate support (OECD Citation2018).

Significant is also education’s contribution to social cohesion (Ajegbo, Kiwan, and Sharma Citation2007). It is in fact this goal which education is called to achieve without employing assimilative practices but with respect of everyone’s individuality, culture and identities. At the core of educational inclusion is the positive stance towards diversity and an appreciation of its inevitability since difference is the key to identity (Kakos and Cooper Citation2024).

Towards a holistic understanding of educational inclusion

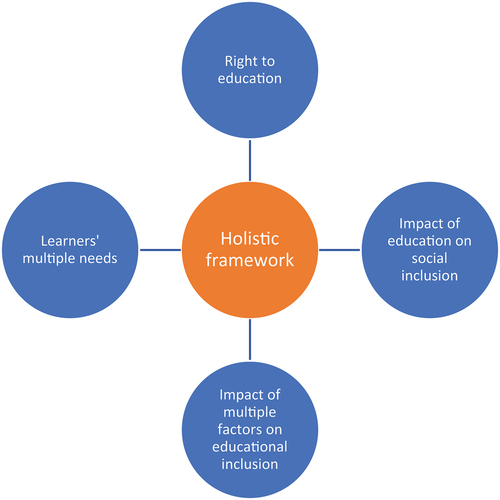

Bringing together the key elements of the discussion above we can recognise that in developing a framework for social inclusion of NAMRS we need to consider at least four key dimensions: (1) The right to education and the view of education as a right; (2) the appreciation of the complexity and multiplicity of the needs that affect the educational inclusion of NAMRS; (3) the significance of the impact of conditions outside education in their educational experiences; and (4) the significance of education in their social inclusion, together with the significance that NAMRS and their families often attribute to education as a route to inclusion and personal prosperity.

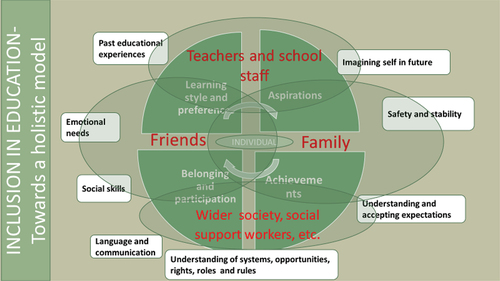

The diagram above illustrates these four dimensions of the framework, but it does not portray the complexity of the interplay of all the elements that exist within them. Revisiting the discussion in this paper and reflecting on findings and suggestions from past and ongoing SIRIUS projects (f.i. Kakos & Teklemariam, Citation2022; Armalys, Rodriguez Sanchez, and van der Graaf Citation2022; Kambel Citation2019; Van der Graaf et al. Citation2021), and especially the analysis on the in-depth qualitative studies conducted by SIRIUS on educational inclusion of refugee students (Koehler et al. Citation2018) and migrant students’ family engagement in education (Koehler et al. Citation2019), we can recognise that within these dimensions there is an array of needs that require addressing and circumstances that should be taken into consideration to complete this framework. These include:

The lack of (and the need for) consideration of students’ already acquired educational experiences. The often sudden departure of NAMRS from their home countries and the often abrupt interruption of their education due to conflicts, unrest and prosecution, in combination with the difficulties in establishing connections between the new schools and their schools in the home country (or, in some cases the lack of relevant efforts) results in a re-start of schooling for the majority of NAMRS. This exacerbates the transition to new educational systems, especially for those students who have completed primary school before leaving their home countries.

Emotional needs. These are related to traumatic experiences, feelings of isolation, extreme vulnerability, and uncertainty and the impact of these on their mental health.

Need for development of social skills that respond to new codes of conduct in school and in society. The demonstration of politeness and courtesy is significant for successful social interactions and are dependent on the swift learning of a myriad of elements of the new code of conduct that NAMRS may come across for the first time when they arrive in their new country.

Language and communication. This does not include only the use of the new vocabulary but the translation of experiences, narrations, systems and knowledge that need to be reinterpreted to facilitate communication. The learning and adoption of new linguistic rules such as the use of singular or plural are also part of this set of needs.

Understanding of systems, opportunities, rights, roles and school rules. NAMRS are required to familiarise with the new educational system, the opportunities, rights and responsibilities of all actors in school life, including the role of parents and level of their expected engagement in school life.

Understanding and accepting expectations in terms of academic work and engagement in school life.

Safety and stability: Need for consideration of the home situation, family stability and safety. This includes the consideration of NAMRS’ legal status, the effect of home visits and interviews by authorities, and the stress related to the process of asylum-seeking applications.

Imagining the self in the future: One key impact of life interruption and transition relates to the ability of NAMRS’ to re-imagine themselves in the future (Dunkel Citation2000). All other difficulties and needs are also related to this since the ability to build a positive image of self in the future is dependent upon the sense of stability, the empowerment to own and control current life situations and the preparedness to investment in the future. All these require what can be considered as a sense of emotional ‘arrival’ which is frequently achieved much later than the physical one and is dependent on the array of factors, conditions and fulfilment of needs described above.

The above take place in the overlapping area of four interlinked and interacting spaces, which are occupied by:

The teachers and other school staff.

The social cycle of peers and friends in and outside the school.

The family.

The wider society as this is represented in interaction in and outside the neighbourhood, the media, authorities and representatives of social structures and support agencies such as the social and health workers, NGOs supporting NAMRS, etc.

Within the overlapping area of the above, NAMRS need to negotiate a cyclical process which leads to the reconstruction of their educational profile as this is defined by their learning preferences and styles (Cassidy Citation2010), the re-emergence of existing and the development of new educational and education-related aspirations, their academic and education-related achievements and their belonging and participation in education and school life.

The diagram below is an illustration of this complex model which integrates all the above circumstances, needs, and processes and argues for a holistic understanding of NAMRS’ educational inclusion.

Implementing a holistic understanding of educational inclusion of NAMRS – implications

As it has been discussed in the beginning of this paper, the starting point and key assumption justifying the adoption of a holistic understanding of the educational inclusion of NAMRS is the consideration of education as a human right and the access to quality education an entitlement of every individual regardless of their characteristics. This is a recognition of the obligation of every state to educational provision that is tailored to these characteristics and responds to individuals’ needs. From such point of view, the model responds also to the calls for a holistic understanding of the learner which considers the interdependence of their academic needs with those associated with their emotional, cognitive, cultural and social experiences and profiles (Nielsen Citation2006).

Studies have already shown that even partial adoption of a holistic approach or incomplete attempts to develop and implement provision on such basis often lead to particularly effective practices (Arnot and Pinson Citation2005). In this last section, the paper will focus on a more systematic exploration of the implications of the adoption of such models in order to draw a complete map of the implementation of relevant practices.

Implications for curriculum development and teaching practice

Building suitable provision for NAMRS requires the recognition of the right to cultural identity and of the significance of culture in the formation of interests and knowledge preferences of all learners. Cultural, religious and linguistic identities, together with individuals’ connection with the past with nations of origin and ancestries, are connected to their need to learn about and participate in cultural practices that relate to their existing sense of belonging. Moreover, intercultural education and the respect to diversity are better manifested through participation in intercultural experiences which can (and should) be fostered in education. A holistic understanding of educational inclusion requires recognition of the above and the provision of opportunities for relevant experiences. It also requires from practitioners the adaptation of their practices so that these respond to the cultural needs of all learners and the move from the ‘delivery’ of a national curriculum to the co-construction with all learners of a suitable, individualised interpretation of it, or, to put it differently, to the development of an individualised curriculum. Appropriately trained staff could facilitate the development of suitable educational spaces for such interpretation or curriculum ‘translation’ (Fritzsche and Kakos Citation2021).

Language

Language is a key component of cultural identity and it is also a key challenge for the educational inclusion of NAMS. In line with the observations about the significance of cultural identity and its relevance to the holistic model of inclusion, linguistic diversity should not only be tolerated but fostered and reinforced in formal and non-formal education (Kambel Citation2019). The use of home language and its significance to the development of a sense of belonging and meaningful participation has been shown clearly in research and translanguaging is a key component for educational inclusion of NAMRS (Kakos Citation2022). The development of inclusive practices, on the other hand, cannot be restricted to language support and linguistic translations. Language should have a prominent position in interventions that are based on holistic approaches, but it cannot be the sole and exclusive focus of inclusive programmes, neither should language proficiency be a requirement for curriculum access.

The school

The simple way to describe the implications of the adoption of a holistic model in educational inclusion is to suggest that the school should not be considered as the only item in the educational inclusion picture, but as a central piece of the educational inclusion jigsaw. Other key components of this jigsaw are non-formal education actors, especially those who have experience and expertise in supporting the development of cultural identities and in assisting NAMRS in social networking. Numerous NGOs in European countries have such experience, but they often struggle to collaborate and coordinate actions with schools (Van der Graaf et al. Citation2021). Policy making and school management should be able to recognise the areas of expertise of such organisations and seek their contribution. They should also recognise the significance of the interactions of their students with other agencies and the impact that these have on their sense of belonging in the wider society and on their educational engagement. An example of this is the often-unsettling experience of students’ and their families’ interactions with authorities assessing their legal status and processing asylum seeking applications. Schools should be prepared to offer appropriate, informed support which exceeds the remit of their academic responsibilities and considers the stress that NAMRS experience, possible trauma, the past and ongoing uncertainty that they experience and the impact of the above on their mental health. Schools should be supported to be in position to coordinate multiagency support and lead multidisciplinary teams of professionals to provide the multifaceted support that NAMRS may need.

Schools should also make systematic efforts to connect with local and international communities. More than educational institutions, schools need to operate also as community centres that understand and respond to the needs of the communities by offering their premises for community events and by developing programmes that facilitate the social inclusion of adults, especially of NAMRS parents. Such programmes could inform parents about the educational system in the host country and about systems of social support, facilitate social networking, support language learning, offer translation services, etc.

Teacher education

All the above should be reflected in teacher education programmes, which should prioritise the development of knowledge and skills for differentiated teaching, support the understanding of schools as a piece of the educational jigsaw, prepare teachers for multiagent collaboration and, most importantly, ground all this training in a solid understanding of the role of the teacher in the view of education as a human right. Teachers need to be prepared to allow students to voice their opinions, work in collaboration with them to tailor the curriculum and pedagogies to suit their educational needs and engage parents and agents outside education in the education of NAMRS.

Implications for policy making

A holistic approach to educational inclusion requires an appropriate policy framework which facilitates the implementation of the above implications on practice. Educational policies need to reflect the recognition that access to quality education is a right of every student and should encourage schools to play a key role in providing this. Such appropriate policy framework could be one that secures immediate access to schools of all NAMRS upon arrival in a country, regardless of their legal status, movement, language skills or age. It should also be accompanied with appropriate guidance to schools and the resources to train all teaching staff in methods that give appropriate consideration to the complex set of needs of NAMRS so that they can access an inclusive education. Schools should be encouraged to seek collaboration with organisations from non-formal education and agencies that can support NAMRS in areas that schools do not have expertise or are unable to access. States should also facilitate the coordination of polices from different policy sectors which affect the lives of NAMRS and their engagement in education. Importantly, appropriate policies should offer the methods and tools for schools to allow students and their parents to inform educational practice and the student-centred evaluation of the effectiveness of such practices.

Implications for research

Researchers and other professionals engaged in evaluation of educational programmes that are presented or considered as holistic could use this model in their evaluation by juxtaposing it to the methods and focus of these programmes. Moreover, researchers examining the inclusion of NAMRS in education should include the exploration of students’ voice in their studies and should use it as a guide in the examination of the impact of experiences inside and outside school on their education. Researchers should also carefully consider the role of students in their research and apply student-centred research designs in their studies. Importantly, researchers need to consider their own role as authority figures and the power relations in their interactions with NAMRS, as well as the impact that this can have on students (Halilovich Citation2013; Hynes Citation2003).

Conclusion

Appreciating the complexity of the needs of NAMRS and the interdependence between educational inclusion and the sense of belonging in wider society are two first steps towards the recognition for the need for the development of a holistic approach to educational inclusion. Identifying good practices in educational inclusion is another way to appreciate the strength of holistic approaches (Arnot and Pinson Citation2005; Koehler, Palaiologou, and Brussino Citation2022). The scope of this paper is not to engage in a detailed analysis of such practices but to offer a structured and complete theoretical suggestion for the conceptualisation of holistic approaches which could guide educational research and most importantly, educational policy and practice. A starting point for the construction of the framework and underlying assumption in the discussion about the implications of its adoption is the recognition of education as a human right to which every individual is entitled. Without claiming that the mere recognition of this entitlement is sufficient for the mobilisation of policy systems to take effect and for educational settings to implement the necessary changes, the paper supports that rights-based, whole-school and multidisciplinary approaches to educational inclusion of NAMRS are conditions for comprehensive understanding of the challenges to inclusion and for the development of appropriate interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michalis Kakos

Dr. Michalis Kakos is an Associate Professor in the Carnegie School of Education in Leeds Beckett University, UK, a Visiting Professor at The University of Education, Freiburg, Germany and the founding director of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in in Citizenship, Education and Society (CIRCES). Michalis’ research interests include citizenship education, the role of the school in supporting the social inclusion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds and the educational inclusion of refugee and migrant students.

References

- Aguilar, P., and G. Retamal. 2009. “Protective Environments and Quality Education in Humanitarian Contexts.” International Journal of Education Development 29 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.02.002.

- Ajegbo, K., D. Kiwan, and S. Sharma. 2007. Curriculum Report: Citizenship and Diversity. (London, DfES).

- Armalys, T., P. M. Rodriguez Sanchez, and L. van der Graaf 2022. Towards Inclusive Digital Education for Migrant Children (SIRIUS WATCH 2021). SIRIUS Policy Network on Migrant Education. (Accessed May 24, 2022). https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Sirius-watch-202114.pdf.

- Arnot, M., and H. Pinson. 2005. The Education of Asylum Seeker and Refugee Children: A Study of LEA and School Values, Policies and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University, Faculty of Education. (Accessed May 24, 2022).https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/people/staff/arnot/AsylumReportFinal.pdf.

- Bacakova, M. 2011. “Developing Inclusive Educational Practices for Refugee Children in the Czech Republic.” Intercultural Education 22 (2): 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2011.567073.

- Brown, P., D. Reay, and C. Vincent. 2013. “Education and Social Mobility.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (5–6): 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.826414.

- Cassidy, S. 2010. “Learning Styles: An Overview of Theories, Models, and Measures.” Educational Psychology 24 (4): 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000228834.

- Dunkel, C. 2000. “Possible Selves As a Mechanism for Identity Exploration.” Journal of Adolescence 23 (5): 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0340.

- Fritzsche, B., and M. Kakos. 2021. “Multilingual Teaching Assistants in the UK: Translators in the Field of Inclusive Education.” In International Handbook on Inclusion: Global, National and Local Perspectives on Inclusive Education, edited by A. Köpfer, J. Powell, and R. Zahnd, 453–469. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Halilovich, H. 2013. “Ethical Approaches in Research with Refugees and Asylum Seekers Using Participatory Action Research.” In Values and Vulnerabilities. The Ethics of Research with Refugees and Asylum Seekers, edited by Block, K. Riggs, E., and Haslam N., 127–150. Australia: Australian Academic Press.

- Human Rights Watch. 2015. Turkey: 400,000 Syrian Children Not in School. (Accessed May 24, 2022).www.hrw.org/news/2015/11/08/turkey-400000-syrian-children-not-school.

- Hynes, T. 2003. The Issue of ‘Trust’ or ‘Mistrust’ in Research with Refugees: Choices, Caveats and Considerations for Researchers. UNHCR Series New Issues in Refugee Research, Working paper 128. Retried from: https://www.unhcr.org/en-lk/3fcb5cee1.pdf. (Accessed May 25, 2022).

- Kakos, M. 2022. “A Third Space for Inclusion: Multilingual Teaching Assistants Reporting on the Use of Their Marginal Position, Translation and Translanguaging to Construct Inclusive Environments.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 1–16. Online First. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2022.2073060.

- Kakos, M. and P. Cooper. 2024 Identity as difference: On distinctiveness, cool and inclusion. In Nurturing the wellbeing of students in difficulty, edited by C. Cefai, The Legacy of Paul Cooper: Peter Lang Publications.

- Kakos, M., C. Müller-Hofstede, and A. Ross. 2016. “Introduction.” In Beyond Us versus Them: Citizenship Education with Hard to Reach Learners in Europe, edited by Kakos, M., Muller-Hofstede, C., and Ross, A., 7–29. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung.

- Kakos, M., and K. Teklemariam. 2021. National Round Tables 2020 Comparative Report. SIRIUS Policy Network on Migrant Education. Retrieved From: (Accessed May 24, 2022). https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Sirius-2.0-year-3-NRTs-Comparative-Report.pdf.

- Kakos, M. and K. Teklemariam. 2022. Roundtables 2021: International Comparative Report on European Roundtables on Educational Inclusion of Newly Arrived Migrant Students (NAMs). SIRIUS – Policy Network on Migrant Education. https://bib.ibe.edu.pl/images/NationalRoundTables2021.pdf.

- Kambel, E. R. 2019. Using Bilingual Materials to Improve Migrant Students’ Parental Involvement: Synthesis Report. Rutu Foundation. https://avior.risbo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Synthesis-Report-Avior-Case-Studies-Parental-Involvement-Final_def2.pdf.

- Koehler, C., S. Bauer, K. Lotter, F. Maier, B. Ivanova, M. Darmody, Y. Seidler, et al. 2019. Qualitative Study on Migrant Parent Empowerment. European Forum for Migration Studies. (Accessed May 20, 2022)https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ALFIRK-Qualitative-Study-on-Migrant-Empowerment.pdf.

- Koehler, C., M. Kakos, V. Sharma-Brymer, J. Schneider, T. Tudjman, A. Van den Heerik, S. R. S, et al. 2018. Multi-Country Partnership to Enhance the Education of Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Youth in Europe. PERAE (Comparative Report). (Accessed May 10, 2022). http://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PERAE_Comparative-Report-1.pdf.

- Koehler, C., N. Palaiologou, and O. Brussino 2022. Holistic Refugee and Newcomer Education in Europe: Mapping, Upscaling and Institutionalising Promising Practices from Germany, Greece and the Netherlands. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 264, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ea58c54-en.

- Lee, S. 2013. “Education As a Human Right in the 21st Century.” Democracy & Education 1 (21): 1–9.

- Lopes-Murphy, S. A. 2020. “Contention Between English as a Second Language and Special Education Services for Emergent Bilinguals with Disabilities.” Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning 13 (1): 43–56. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2020.13.1.3.

- Malkova, Z. A. 1989. “The Quality of Mass Education.” Prospects Quarterly Review of Education 19 (1): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02195856.

- Meda, L., R. Sookrajh, and B. Maharaj. 2012. “Refugee Children in South Africa: Access and Challenges to Achieving Universal Primary Education.” African Education Review 9 (1): S152–S168. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2012.755287.

- Nielsen, T. W. 2006. “Towards a Pedagogy of Imagination: A Phenomenological Case Study of Holistic Education.” Ethnography and Education 1 (2): 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457820600715455.

- OECD. 2018. The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: Factors That Shape Well-Being, OECD Reviews of Migrant Education. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en.

- Powell, S., and R. Tutt. 2002. “When Inclusion Becomes Exclusion.” Education 30 (2): 43–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270285200221.

- Razer, M., V. J. Friedman, and B. Warshofsky. 2013. “Schools as Agents of Social Exclusion and Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (11): 1152–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.742145.

- Rutter, J. 2001. Supporting Refugee Children in 21st Century Britain: A Compendium of Essential Information. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

- Rutter, J., and R. Stanton. 2001. “Refugee children’s Education and the Education Finance System.” Multicultural Teaching 19 (3): 33–39.

- Sharma‐Brymer, V., M. Kakos, C. Koehler, J. Schneider, T. Tudjman, A. Van den Heerik, S. Ravn, et al. 2019. Challenges and Opportunities in Education for Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Youth in Europe: A Handbook of Good Practices and Effective Policies. Stockholm: Fryshuset, SIRIUS.

- Sidhu, R., and S. Taylor. 2012. “Supporting Refugee Students in Schools: What Constitutes Inclusive Education?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 16 (1): 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903560085.

- Sirin, S. R., and L. Rogers-Sirin. 2015. The Educational and Mental Health Needs of Syrian Refugee Children. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute.

- Thomas, R. L. 2016. “The Right to Quality Education for Refugee Children Through Social Inclusion.” Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 1 (4): 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-016-0022-z.

- UN General Assembly. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (Accessed May 22, 2022).http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml.

- UN General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. (Accessed May 22, 2022). http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm.

- United Nations. (1995). The Copenhagen Declaration and Programme of Action: World Summit for Social Development. (Accessed May 22, 2022). www.un.org/esa/socdev/wssd/text-version/agreements/poach4.htm.

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees 2011. UNHCR Resettlement Handbook. (Accessed May 22, 2022). www.unhcr.org/46f7c0ee2.pdf.

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees 2019. Stepping Up: Refugee Education in Crisis. (Accessed May 22, 2022). https://www.unhcr.org/steppingup.

- Van der Graaf, L., J. Didika, C. Nada, and H. Siarova 2021. Taking Stock of SIRIUS Clear Agenda and New Developments in Migrant Education (SIRIUS WATCH 2020). SIRIUS Policy Network on Migrant Education. (Accessed May 24, 2022). https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SIRIUS-Watch-2020.pdf.