ABSTRACT

This article highlights local to global linkages of ‘land grabbing’-related conflicts based on a case study of land investments in the Maji area, located in Ethiopia’s southernmost fringe territory. History of the area over the past century tells that national actors have aggravated conflicts at the local level to meet resource demand at the national and global levels. Global economic processes and actors play an indispensable role in creating demand for land. National governments and local actors work towards meeting this demand through institutional and legal interventions which ‘create’ and advertise ‘free’ land for transfer to investors. This necessitates national and local governments to deploy strategies to prevent existing and potential land users from benefiting from available resources. The risk of conflict will be heightened in situations where authoritarian development is pursued: as exclusions happen through strategies with low local legitimacy, primarily through force and, as such, invite violent counter-exclusions from the local community.

Introduction

This article aims to contribute to the understanding of local to global linkages by analysing conflict implications of land acquisitions in Ethiopia’s southernmost frontier lowlands. While the available literature recognises the global nature of the structural causes of the land rush at the close of the previous decade, studies on consequences usually focus on local dynamics,Footnote1 and ignore historical dynamics.

The global land rush mainly targeted sub-Saharan Africa, buttressed by low productivity, poor land governance and the authoritarian tendencies of regimes.Footnote2 Five African countries – Ethiopia, Ghana, Mozambique, Nigeria and Sudan – account for close to a quarter of global projects.Footnote3 Ethiopia has been among the most targeted on the African continent, leading Kachika to label Ethiopia an ‘epicentre of land grabs for food exports in Africa’.Footnote4

A closer look at where land deals occur in Ethiopia, based on transferred acreage to the Federal Land Bank, tells that Oromia regional state takes the lead with a total of 1.7 million ha of ‘unused’ land identified for investment, followed by Benishangul-Gumuz (1.4 million ha), Gambella (1.2 million ha) and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP) regional state (500,000 ha).Footnote5 If we take the total land area of the regions into account, it becomes obvious that Ethiopia’s lowland regions, particularly Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz, are the most targeted. The total areas of the four regions are as follows: Oromia (28,453,800 ha); Benishangul-Gumuz (5,069,900 ha); Gambella (2,978,300 ha); and SNNP (10,547,600 ha).Footnote6 This in effect means that Gambella and Benisganhul-Gumuz, respectively, aimed to lease about 40 and 27 per cent of their territory, while Oromia and the South are only leasing less than 6 per cent.

Scholars, civil societies and policy-makers have debated the impact of land deals and the questions over how the negative consequences can be reduced and the positives harnessed over the past decade. Particularlywhen it comes to contestations and conflict implications, available research mainly focuses on case studies and does not relate political processes at the local level with those at higher levels.Footnote7 The solutions offered by civil society organisations and international organisations mainly include improving land governance, within the framework of what the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organisation called ‘responsible governance’, and allowing the voice of the local community to be heard and included in decision-making by conducting genuine ‘free, prior, informed’ consultation, particularly with indigenous peoples.Footnote8

In this article, we aim to develop a more comprehensive understanding of conflict dynamics generated by land acquisitions which integrates all levels, drawing on the local to global framework developed in the introductory article of this special issue.Footnote9 We complement insights from the framework with what Li calls ‘analytic of assemblages’, i.e. processes which make ‘such large-scale investments thinkable, and the practices through which relevant actors (experts, investors, villagers, governments) are enrolled’.Footnote10 Land is a socially co-produced resource. Its material qualities matter but do not suffice to determine land’s quality as a resource. Land’s ‘resourceness’ is not intrinsic and could change with time, in value systems or in technology. It is through a ‘provisional assemblage of heterogeneous elements including material substances, technologies, discourses and practices’Footnote11 that land is made a resource and investible. Moreover, land’s materiality makes its ‘resourceness’ conditional on exclusion from other users.

Exclusion is an inevitable process in any land relation, and is ‘structured by power relations’. Even the poorest farmer or pastoralist uses a particular plot of land with the assumption that others will be prevented from using the same plot for that period. As such, accessing and utilising land pre-assumes a condition in which others are excluded. Following the definition of access by Ribot and Peluso, Hall et al. define exclusion as ‘the ways in which people are prevented from benefitting from things’.Footnote12 This could come in three types: (1) maintaining access to already existing users by preventing other potential users; (2) exclusion of existing users to benefit new users; and (3) preventing actors who lack access gain access to land. Of these three, this article is more interested in the second.

Exclusion could happen in four non-exclusive forms: regulation, market, force and legitimation. Regulation refers to ‘rules-formal and informal – that govern access and exclusion’ by zoning (determining boundaries, allowable uses and ownership and usufruct claims) and promoting rule backed claims. Force is ‘at the heart of regulation’ and is not the domain of formal actors only. Agro-pastoralists could use arson and ambushes to threaten existing or new users, while implicit force, intimidation and fear could be used by governments, in addition to blatant violence. Exclusions could also happen through pricing, i.e. the market. Land markets are built through regulation, force and legitimation to transfer rights to preferred clients/users of land. Legitimation functions through ‘justifications of what is or of what should be and appeals to moral values’. The aim here is to make exclusions morally acceptable (for the sake of the greater good) and to reduce resistance.Footnote13

We argue that conflicts are expressions of the low legitimacy of exclusion strategies and of the counter-exclusion resistance by the negatively affected local group. Land is not like other commodities, as it has social functions and is the basis for livelihoods and life. As such, exclusion from land will be met with counter-movements.Footnote14 As Tania Li stresses:

Land’s material emplacement means that the people on the spot usually have a say, if not through democratic processes then through the exercise of force, as they resist eviction, reoccupy disputed land and insist on their right to a patch of ground on which to build a hut, and plant some food.Footnote15

We intend to explicate such a process taking the case of the Maji area, and show the role national and international political and economic processes played. The article is based on extensive fieldwork in the area in 2017. A total of 32 informants representing various ethnic groups (10 Suri, five Dizi, one Me’enit and five ‘Amhara’) and Bureaus (five from security, two from Zone administration, three pastoral development-related actors, one from Culture and Tourism and one Tour Guide) were interviewed. When distance and insecurity prohibited face-to-face interviews, phone interviews were conducted. Furthermore, the article also benefited from a review of official documents and the first author’s extensive knowledge of the area.

This introduction is followed by five parts. The first introduces the Maji highlands and the people inhabiting it, with a focus on its incorporation into the Ethiopian Empire and cycles of conflict from the late nineteenth century to 2007. The second covers land deals and a second ‘development’ activity the Ethiopian government has been implementing in Bench–Maji Zone after 2007, i.e. villagisation. The third expounds the sociopolitical, particularly conflict, consequences of land deals at the local level. The fourth section focuses on national and global levels to understand conflict at local levels. The last section concludes the article using the analytic of assemblage and how local to global linkages play out, before giving policy recommendations.

History of centre-periphery relations and conflict in the Maji area

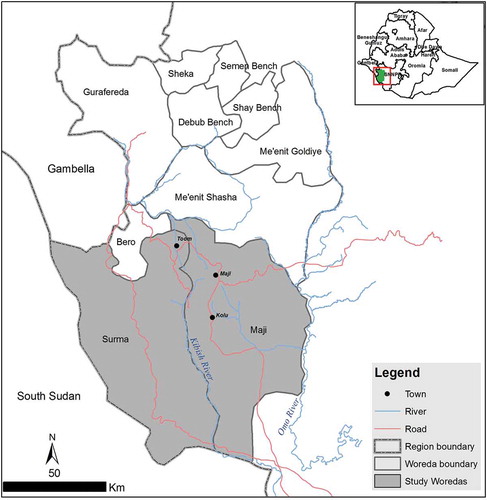

The Maji area is located at Ethiopia’s southern margin, bordering Kenya and South Sudan, encompassing the area to the west of the Omo River (see below). In terms of administrative categorisation, this area falls in Bench-Maji Zone of the SNNP region. It was incorporated into the Ethiopian state in 1897, as part of the campaign to the southernmost frontier, which brought a diverse group into the empire. The Maji area is inhabited by the Dizi, Suri and Me’enit. From the 11 Weredas (districts) of the zone, this article focuses on Maji and Bero Weredas (for the agriculturalist Dizi) and Surma Wereda (for the agro-pastoralist Suri). The Nyangatom and Toposa are encroaching into the Maji area in search of pasture and water from their borders with Surma Wereda, while the Anuak and Ethiopians from other parts of the country are migrating towards Bero attracted by the lucrative trade in gold and small arms. Although these population groups do not constitute part of the Maji area, they have direct implications for conflict dynamics in the area.

Figure 1. Bench-Maji Zone of SNNP (the study area) in Ethiopia.

Source: Zeleke Kebebew, for the authors.

The Dizi number about 53,410 according to the latest population projections from 2013. They speak an Omotic language and live off farming in Maji town and Bero Weredas. Maji town is also settled by a diverse group of non-indigenous ethnic groups who migrated from other parts of the country, collectively called ‘Amhara’. Haberland called Maji an ‘Amhara town’.Footnote16 The agriculturalist Dizi are surrounded by agro-pastoralist Nilo-Saharan (Surmic) language-speaking groups, the Suri (numbering about 28,329) and Me’enit (numbering about 152,520).Footnote17 These groups have similar groups across the river in South Omo Zone: while the Suri speak a similar language to the Mursi, the Me’enit speak the same language as the Bodi. The Suri border South Sudan to the west, and face the expansionist pressures from the Toposa (in South Sudan) and their allies, the Nyangatome, in South Omo Zone. The Me’enit inhabit two Weredas: some subsisting as agriculturalists in the mid-altitude zones of Me’enit Goldiya Wereda, while most live as agro-pastoralists in the lowlands of both Me’enit Goldiya and Me’enit Shasha Weredas.

The mode of incorporation of, and state–society relations in, the Maji area followed the characteristic state expansion in Ethiopia, which centred on the northern highlands as core areas, and expanded to conquer highlands and lowlands in the south, west and east. This was followed by cultural denigration, plunder and a changing, but simultaneously persistent, mode of centre-periphery relations.Footnote18 There were significant differences between the highland and lowland frontiers when it came to land alienation and extraction from the newly conquered territories however.

At the level of discourse, successive governments viewed both the highland and lowland peripheries as frontier terra nullius zones. These were taken as areas empty of civilised people and efficient production relations, but full of resources; thus justifying invigoration by the ‘civilising’ hands of the state.Footnote19 The production system, i.e. ox-plough farming of cereals, and land governance mechanisms mastered by the expanding group could only be applied in the highlands. Thus, central governments viewed only the highlands as a resource. Thus, the state had a weaker presence in the lowland peripheries dictated by ecological hindrances, the difficulty of controlling and taxing a mobile population and the lack of a suitable technology.Footnote20

The imperial (until 1974) and military (1974–1991) governments attempted to control, integrate and extract from the highland parts, particularly the Maji highlands, rather than the vast surrounding lowlands. The mode of administrative integration of, and economic extraction from, these highlands was comparable to the practice in other parts of the then newly incorporated highlands. The centre’s construction of the highland frontier as a resource enticed a forceful dispossession of existing land users. Land alienation and distribution to representatives and functionaries of the state was the norm, converting the local community into serfs.Footnote21 Given the social and political structure of the time, the imperial government mainly relied on force to exclude the conquered groups, leaving little room for regulation, the market or legitimation.

From these highlands, imperial administrators launched plunder campaigns to surrounding lowlands. Thus, the lowland periphery was left largely untouched for most of the first century after incorporation. In the lowlands of the Maji area, the ruling elite valued wildlife products (mainly ivory) and slaves, not the land per se.Footnote22 Low interest in land meant that new land users and new forms of exclusion did not occur in the lowlands. Rather regional dynamics of forceful northward territorial drift of agro-pastoralists, including groups from southern Sudan, to mid-altitude areas was pervasive. In the lowlands of the Maji area, representatives of the state were not directly involved in land access and exclusion dynamics, and consequent conflicts, until the end of the 1990s.Footnote23

Resource conflicts are necessarily fought over something which is already produced/under production and has a certain cultural or economic value. By going through phases of conflicts with links to national and global levels, in what follows, we will elucidate the evolution of changes in the nature of resource conflicts and links with national and global discourse and economic processes between the late nineteenth century and 2007 in the Maji area. To be sure, conflict is a common feature of the area, particularly pastoral conflicts caused by contestations over scarce and erratic pasture and water resources and the northward territorial drift of pastoral populations across the century.Footnote24 These are largely ‘local’ conflicts, with little direct link to the world beyond, for example through trade in small arms, inability/unwillingness to protect the international border and commercialisation of cattle raids in more recent years.Footnote25 Our concern is not with such conflicts, but rather with conflicts which had direct linkages to the Ethiopian state or its representatives and, through the state, to global actors and processes.

A review of the available literature suggests that in the earliest periods following the incorporation of the Maji area, resource conflicts were mainly over ivory and slaves (1890s–1937). This was followed by a relatively peaceful period when the area was given Maed Bet (crown land) status, signifying the sole ownership of the Emperor and sourcing of agricultural products, including cattle and honey, to the royal palace.Footnote26 Although the Gabar system of expropriation and slavery were banned as early as 1935, both at the time of Maed Bet (1935–1937) and that of the Italian occupation (1937–1941) Maji and its inhabitants suffered from continued exploitative and violent resource extraction.Footnote27

Both ivory and slaves attained a ‘commodity’ status before Maji’s incorporation, and there was a demand for them at national and international levels.Footnote28 According to British colonial reports,Footnote29 Ethiopian authorities spotted the potential and started extracting ivory from the Maji area in 1902 (and dominated the local political economy until 1923) after capturing a caravan of Swahili-speaking traders with ivory there. Soon after, the area became a centre for ivory traders and hunters, linked through a pact made possible by the exchange of ivory for rifles and powered by slave labour for transportation to Jimma and Addis Ababa.Footnote30

Ivory was not a new commodity for Ethiopia’s rulers. Ethiopian Emperors had been giving ivory, with other expensive gifts, to senior officials and friendly emperors for millennia. It was also historically extracted from the lowland frontier surrounding the highland core.Footnote31 Therefore, following the state’s expansion the imperial government only overlaid an already functioning mode of extraction to a new territory, in our case the Maji lowlands, leading to conflict generation there. With a decline in the remaining elephant population, and with the consequent dwindling of the attractiveness of the ivory trade, imperial administrators focused on slave raiding and trade. This later came to characterise the Maji area’s political economy.Footnote32

Before engaging in the act, the slave raider and trader first reduced the individual from the status of a human being into a commodity through a social process.Footnote33 Frankde Halper’s letter narrates the depressing merger between the twentieth century tax system and the then slave trade in the following manner:

If Maji gabars fell behind in their payments […] they or their children might be sold as slaves, and there was a constant drain, especially of children, from the mountain [Maji]. The frequent changes of governors bore hardly on the population. [For example] when Getachew’s [Maji’s Governor] soldiers left Maji in 1933 they took over 1,000 Maji natives with them. The population of the mountain therefore fell sharply, until, of the large population inhabiting the area earlier in the century, only a few thousand remained.Footnote34

As the slave trade from Maji was gaining momentum and reached its peak, the acceptance, morality and legality of trade and ownership of slaves both domestically and at global levels was declining. In Ethiopia, Emperor Tewodros (1855–1868) was the first to outlaw slavery and the slave trade, but Emperor Menilik (1889–1913) was more effective in actually reducing it. The establishment of the League of Nations and Ethiopia’s membership – actually the bad publicity of colonial powers, particularly Italy, to depict Ethiopia as ‘uncivilised’ thus not meeting the requirement of joining the League as well as justifying its colonial ambitions – conspired against this mode of extraction. Establishment of a British Consulate in Maji in 1920 had a similar influence.Footnote35

This ‘global influence’ in the immediate period only succeeded in delinking the slave raiding and trade from the global slave trade. Slavery and utilisation of slave labour continued within Ethiopia, leading Fernyhough to argue that ‘before 1935 slavery was an integral part of the Ethiopian social structure’, with Maji being a ‘center of slave trade’, according to Salvadori.Footnote36 The slave trade was central in causing what is called the ‘Tishana Revolt’.Footnote37 The first revolt started in 1911, and the second in 1922. In both cases, the Tishana (Suri) revolted against major slave raiding campaigns to restock slave populations in central parts of the country (the second following decimation by an influenza epidemic in 1919–1920). Simultaneously, the Suri engaged in raiding farther removed groups to exchange them for guns. The guns would later be used in the resistance against their own enslavement. Unpacking the ‘Tishana Revolt’ in 1929, Hodson stated:

The Abyssinians by carrying off the [Tishana] women and children have made the Tishana their mortal enemies […] slave traders are ever welcome in the country as they purchase captives from the Tishana. Captive slaves were exchanged for guns so that the Tishana could resist their rulers more effectively. In order to obtain the slaves the Tishana raided less well-armed peoples far and wide within Maji and out on to the Boma plateau.Footnote38

Pressure from global actors played a role in instigating Emperor Haile Selassie (regent 1916–1930, Emperor 1930–1974) to give Maji the privileged position of crown land. As Salvadori stressed, the ‘emperor [was] deeply embarrassed by the situation in Maji, [and] decided to turn it into a model province. To this end, he declared it madbet, crown land, directly under his control’.Footnote39 This designation came in 1937, only two years before Italy’s five-year occupation of Ethiopia.

The crown land status exemplifies the highest form of exclusion, and as such reduced competition between different national and regional actors. With the effective abolition of the gabar system and slavery in the 1940s, a period of relatively fewer conflicts in which national and global actors were directly involved ensued. This continued into the first decade of Derg’s rule (1974–1991), as the Land Reform and Cultural Revolution had little resonance and impact on cultural, sociopolitical and economic dynamics in the area,Footnote40 except in the highlands. This was to change in the mid-1980s due to the strain caused by the intensifying drought and famine which had a devastating impact on the local (pastoral) economy.Footnote41

Following the extensive destocking of herds caused by the drought, conflict over restocking attempts became rife.Footnote42 This revamped the local political economy. The Suri engaged in a ‘gold rush’ as a response to the post-famine economy. The associated criminality and violence continue to hold a dominant position in local conflict dynamics, facilitated by greater access to guns from the civil war in South Sudan.Footnote43

When it comes to conflicts which have a direct relation to national and global level actors, the above discussion shows that the mode of centre-periphery relations is key. Since the era of incorporation of the Maji area both the imperial and Derg regimes extended a politico-economic order aimed at exploiting and plundering local resources. Cultural denigration persisted with the attempt to impose the ‘high’ state culture.Footnote44 The integration of Maji into national and global capitalist relations makes economic engagement in the areas violent and extractive. This mode of relations has not changed over the past century, while the extracted goods have changed.

Land acquisitions, villagisation and conflict in the Maji area (2007–2016)

Over the past decade, the Ethiopian government has been implementing ‘muscular high modernist’ development activities, encapsulated in the Growth and Transformation Plans (the first for 2010/11–2014/15; and the second 2015/16–2019/20), including in the lowlands.Footnote45 This falls within the broader plan of building an Ethiopian developmental state, which in the lowlands is expressed through the aggressive leasing of land to foreign, diaspora and domestic investors. Land acquisitions in Ethiopia’s lowlands are accompanied by a villagisation scheme, with a veiled objective of making the process of alienating land more acceptable and the lowlanders more easily controllable by the state.Footnote46

Similarly, the Ethiopian government’s authoritarian developmentalism is expressed in the Maji lowlands through land leasing and villagisation. The government’s ‘cultural hegemonism’ is advanced as a top-down process, with no genuine consultation and with complete disregard for the rights of local groups.Footnote47 The local elite are too powerless to resist or absorb the shock coming from above, and mainly work to meet ‘development targets’ set at the centre (be it in terms of land area leased or number of households joining new villages) to avoid demotion/firing at ‘Gem gema’ (critical appraisal) sessions.Footnote48 In this section, we address the extent of land deals, villagisation and conflict associated with these ‘development’ activities in the Maji area since 2007.

The Maji area has experienced an abrupt increase in the number of deals and total land area transferred to investors since the late 2000s. The Zone’s Investment Office registered a total of 65 land deals since 1997–1998: of these the greatest majority (54) occurred after 2007. While coffee and spices are the most preferred crops by investors, all 23 firms that intended to grow cereals got the contract after 2007. Moreover, the average land area transferred after 2007 is much larger than the previous decade, with many upwards of a thousand hectares and the highest being 10,000 ha.Footnote49 Additionally, the federal government made two land transfers in this period: 30,000 ha for a Malaysian company intending to grow palm trees and 25,000 ha for sugarcane plantation to be established by the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation (ESC). This trend follows the global land rush enticed leasing of land generally witnessed at the national level.Footnote50

Taking the global land rush as an opportunity offered by the conjectures of the time, the Ethiopian government promoted land investments.Footnote51 Activities of the ESC to expand plantations and establish new sugar mills were initiated to take advantage of a 25-year high in sugar prices at global markets. However, this does not mean that the Ethiopian government only responded to global demands. Rather, the government translated this global condition to national and local realities, i.e. aggressive developmentalism after 2005 and the perceived existence of unused land in the lowlands. Moreover, the ambitions were not solely economic: the government’s political project of extending power and authority to these lowlands is also at the centre of the land leasing project.Footnote52 This mode of ‘development’ was essentially a cultural exercise favouring ‘cultural hegemonism’ and contributing to the erosion of local cultures.Footnote53

This necessitated federal and regional governments to construct (mainly) Ethiopia’s lowlands, initially at the discursive level, as ‘vacant’, ‘unused’ or ‘marginally used’. Later on, the federal government designed and deployed a set of institutional and legal frameworks – which particularly favoured firms intending to export the greatest part of their harvestFootnote54 – to transform the discourse into actual land transfers.

A crucial phase here was the identification of ‘vacant’ land using satellite technology. The regions delegated their constitutional land administration powers over the ‘vacant’ lands to the federal government, a measure which lacks constitutionality. The federal government established the Agricultural Investment Support Directorate (AISD), which was later re-branded the Ethiopian Agricultural Investment Land Administration Agency (EAILAA), within the Ministry of Agriculture. This Directorate/Agency was entrusted with the responsibility of administering the identified ‘vacant’ land and transferring the same to foreign and large domestic firms (investing on 5,000 ha or more).Footnote55 Accordingly, the federal government leased 30,000 ha of land in Bench-Maji Zone, on the border of Surma and Maji Weredas in late 2010, to Koka plantation. This firm is the only foreign-owned agricultural investment in the Zone and proposed to grow palm trees and entered a contract for 35 years. However, the project was abandoned in 2014, when it became the centre of violent conflict.Footnote56

The SNNP regional government commenced implementation of a villagisation scheme in the 2011–2012 fiscal year. Through this scheme, the regional government aimed to settle the pastoral and agro-pastoral population in five agro-pastoral Wereda of the Zone – the Suri and the Me’enit, not the Dizi – in what is claimed to be a ‘voluntary’ and ‘water-centred’ process. The primary stated aim of the scheme is to ensure the food security of agro-pastoralists and improve their access to social services, such as education, health, veterinary service, water and the like. This apparent good intention is however marred by the scheme’s links with land alienations. As a result, villagisation is criticised for ‘displacing’ land users to make way for commercial agricultural investments. Members of the local community also resisted implementation of the scheme, leading sometimes to enforcement by the military and police.Footnote57

Such ‘development’ schemes, the government believes, will promote social welfare by creating jobs, improving infrastructure and the delivery of social services, enabling technology transfer, and eventually contributing to a reduction in incidences of conflict.Footnote58 The late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi articulated this vision in his speech at the 13th National Pastoralists’ Day celebrations on 25 January 2011 in Jinka, South Omo. He stressed that development projects in the lower Omo Valley will ‘improve’, ‘stabilise’ and ‘secure’ pastoralists’ life.Footnote59 Similarly, a former top executive of the Zone stated:

Development plans of the Ethiopian government in Maji and Surma Weredas, as elsewhere in the country, aim to bring rapid development. In [Bench-Maji] Zone we permitted the Malaysian Koka Company to invest on the area between Maji and Surma Weredas with the aim of ending perennial conflict between Suri and Dizi. We thought that the investment could bring alternative job opportunities both for Suri and Dizi on one hand and a venue for incubating peace and development through out-grower schemes and formal employment.

This authoritarian vision towards development however faced fierce contestation from academics and the local community. In most of the lowlands, these projects were implemented within a context of violent conflict, and oftentimes became part of the problem, rather than the solution as intended.Footnote60 As will be shown below, the conflicts are not continuations or an intensification of existing types of conflict. Starting with a summary of conflict incidents in the study area, we will focus on one particularly severe conflict event below.

The period of pursuing authoritarian development overlapped with increasing insecurity and high conflict incidence in the Maji area. Between April 2011 and March 2016, the Zone’s Security Administration Office recorded 179 violent conflict incidents, mainly between the Suri and their neighbours.Footnote61 These conflicts claimed the lives of a total of 113 individuals. An additional 31 were wounded and 1,210 cattle raided. While this can be explained by the perennial nature of conflicts in the area – due to northward territorial drift of agro-pastoral groups, gold panning, cattle rustling and competition for pasture and water – land deals and villagisation have also emerged as major conflict causes. What is more interesting is that in the period under discussion, the number of lives lost is highest in relation to one conflict incidence in February 2012 which is related to the Koka plantation.

It all started with the killing of three Dizi officers on 10 February 2012 by the Suri. The officers, who were from Tum area administration, Maji Wereda, were attempting to demarcate the boundary with the neighbouring Surma Wereda. The following day was a Saturday, a market day in Maji, which Suri from surrounding faraway places attend too. Unaware of the incident, the Suri came as usual to trade. Dizi traders and townspeople learnt about the killings of the three officers, particularly Mr Daniel Bahiru, a highly valued Dizi Wereda administrator, in the afternoon. Afterwards, the Dizi avenged the loss of their kinsfolk by killing the Suri they could lay their hands on, those attending the market on Saturday 11 February 2012. At least 23 Suri were killed with stones, machetes and knives. This is a conservativeFootnote62 number recorded by the government, but others report a much higher figure of 35 to 50. This shows that a single incident led to close to 15 per cent of the 113 lives lost in the 179 conflict incidents officially recorded between 2011 and 2016. Furthermore, this incident led to a vicious cycle of revenge killings on both sides and deep insecurity, leading to the Suri being banned from attending the Maji market. In the following sections, we provide details on these conflicts and how conflict over ‘land grabbing’ at the local level relates to national and global processes.

Conflict over ‘land grabbing’: a local perspective

The severity of the above-stated events and the persistence of insecurity afterwards, make an investigation into the causes a worthy endeavour. We start by summarising the major findings of the only two works which extensively dealt with this incident. The Oakland Institute summarised the event in the following manner:

First, three Dizi policemen were killed by Suri who resisted the Dizi policemen’s attempts to mark their land for the sefara (the Amharic term for settlement) program. The land marking was intended to enable the expansion of the Koka plantation. […] In an act of retaliation just a few days later, Dizi killed 30–50 Suri men and women with machetes and stones in a Saturday market in the town of Maji […]Footnote63

A few months later, Wagstaff came up with the following analysis:

On 11 February 2012, there was a killing of ca. 35–50 Suri people, including women and children in the Maji town market place, with machetes, clubs and stones perpetrated by local Dizi and townspeople. […] This appalling case of mass killing appeared to have been a 'revenge' for the killing of three Dizi woreda officials from Maji, including a popular Dizi man, Shalu, on 10 February by Suri in a skirmish near the Koka plantation. This team of officials who had been demarcating with GPS the border of the plantation between the Dizi and Surma woreda near the locations of Goltang and Banka, and marking homes and trees with white paint.Footnote64

What is common in the findings of both, and all our informants, is the centrality of the expansion of the Koka plantation in causing the conflict. While the Oakland Institute adds that the land demarcation was for villagisation too, one Dizi key informant added that the motive behind the demarcation was the subsequent intention of biodiversity conservation in the dense forest of Banga.Footnote65 As such, both the Oakland Institute and Wagstaff, and all informants, insist that the demarcation of the boundary between a Kebele (lowest administrative unit) inhabited by the Dizi and another inhabited by the Suri is at the centre of the violence. One key informant gave a more detailed account of what happened:

The conflict originated in Tum area of Banga Kebele. The conflict was caused by the boundary demarcation. People working for Tum administration office went there and begun painting on rocks and trees, claiming the area belongs to the Dizi. In due course, they met with [Suri] herding boys; then the boys shouted 'Our enemies are here!' This swiftly brought Suri adults to the scene. The Suri adults asked the people [doing the demarcation]’ Why did you come here?'' The officials replied 'We are here in peace' The Suri men further probed 'You people did not come into this area before. So why today?' This led to disagreement, and gunfire after sometime in which one of the [Dizi] officers from Tum got shot and the others fled. This incident was on Friday [10 February 2012], and unfortunately uninformed Suri from Kibish, Oudumunt and Dishu were on their way to Maji to attend the Maji market on Saturday. As usual, the Suri traded until 4:00 PM, but when the news of the Banga incident reached the Dizi and they started killing Suri in Maji with rocks, machetes, and clubs. The death of many Suri people in Maji market caused the subsequent chaos in the area.Footnote66

The contestation over the Banga boundary is not new. The Suri have de facto control over the area, although it is a de jure Dizi territory. The area which was transferred to the Malaysian company used to be a Suri grazing land, while tax now is allegedly being collected by Maji Wereda, and thus paid to the Dizi. Furthermore, while Dizi men were given employment opportunities in the Koka plantation, as drivers mainly, the Suri did not get such opportunities. Thus, from the perspective of the Suri, there are two points of concern: (1) as they inhabit the land, following constitutional provisions which aim to match ethnicity with administrative borders, the territory should be theirs; (2) it then follows that benefits accruing from the investment, in the form of taxes, jobs and others, should reach them, not the Dizi. The Suri view the witnessed reversal as authorisation of the Dizi’s legal ownership of the contested territory, as indicated in the following quote:

Dizi live in Suri areas and the Suri also live in Dizi areas. In such a context, the Malaysian company came to the scene and escalated the tension between these two groups. When the Malaysian company began operations, majority of the inhabitants of the land [Koka area] were Suri yet the company pays tax for Maji Wereda [which belongs to Dizi]. The complaint raised by the Suri is 'we deserve the tax not the Dizi', which the Dizi counter by saying 'Koka belongs to us in administrative structure and political map', hence 'we [Dizi] deserve the tax not the Suri'.Footnote67

What is more interesting is that, in reality, taxes were not paid, although allocation of tax revenue was at the centre of the conflict. Firms investing in commercial agriculture get a range of support schemes, including tax holidays, thus the Malaysian company was not legally required to pay taxes for the period it operated in the area. Rather, security officials of the Zone attribute the contestation over tax revenue as only a scapegoat for the more illicit political agenda of local political elite.Footnote68

This territorial contestation between adjacent administrative units should be seen within the broader context of the spin-offs created by Ethiopia’s ethno-linguistic federalisation. The federal project aims to match ethno-linguistic and administrative boundaries.Footnote69 In this structure, administrative boundaries serve a much higher purpose, give a sense of finality and indicate exclusive ownership of (resources in) a given territory. This is despite the historical trend of constant negotiation on resource utilisation and access, especially in pastoralist settings. This led to a more exclusive politics of resource governance, and contributed to escalation of tension and conflict.Footnote70 Similarly, the Suri, following the constitutional basis of self-administration, are contesting the de jure ownership of the area by the Dizi. In addition to losing the potential benefits accruing from the investment to the Dizi, the clearing of vegetation and diversion of the Koka River to the plantation has negatively impacted the Suri, triggering their resistance.Footnote71 Although somewhat watered down, the Development Assistance Group confirms the takeover of seasonally used land from Suri pastoralists by the plantation and explained the ‘episodes of violence against plantation workers’ as an expression of related grievance.Footnote72

The above dynamics attest to the continuation of the historical centre-periphery relations marred by hierarchical power and cultural relations and the funnelling of wealth and resources to the centre. The Suri are in effect violently resisting national politico-economic projects and ‘civilisational offensives’, to use Wagstaff’s words.Footnote73 The authoritarian, top-down and dispossessive actions of the federal, regional and Wereda governments are countered by the Suri, as the latter seek to maintain access to particular resources and territories. In the next section, we show the local to global linkages in causing ‘land grabbing’-related conflicts by going beyond the national to show linkages with the global and also presenting details on how national actors are deploying state power to take land from the agro-pastoral groups in the process of availing it to actors they deem more efficient.

Conflict over ‘land grabbing’: a local to global perspective

Using the empirical detail given in the previous section, below we explicate local to global linkages in ‘land grabbing’-related conflicts, focusing on the process of assembling land as a resource and the deployed strategies of exclusion (and attendant counter-exclusion strategies). provides a summary of the interaction between major actors and processes at local, national and global levels.

Figure 2. Summary of the interaction of key processes and actors at different levels.

Source: The authors.

It took a long time for the Ethiopian government to construct the vast lowlands as resources worthy of investment. Successive governments had an interest in doing so, and that interest was intensified over the past decade and a half due to the heightened need for resource mobilisation and extraction to meet the dictates of authoritarian developmentalism. In the early 2000s, at the start of the developmental state project, the federal government recognised that massive investment on infrastructures and service delivery was necessary for the lowlands to be an investible resource.Footnote74 Otherwise, potential investments will be hindered by prohibitively high costs considering that the Maji area is far from the country’s political and economic centres and poorly serviced.

The abrupt spike in the global demand for agricultural land changed the economic and political calculus. It suddenly increased the apparent profitability of investments in commercial agriculture in remote parts of the world, simultaneously attracting investors to speculate on land value as well. This ‘tricked’ investors into taking higher risks and developing countries into entering a race to attract more agricultural foreign direct investment. Without this crucial role of the global land rush, it would be difficult to fully understand the ‘land grabbing’ dynamics in Ethiopia and in the Maji area in particular. Thus, the argument here is that this global situation created by the fuel and food price crises contributed to encouraging the Ethiopian government to create land as an investible resource.

Global actors could only search for land in a ‘ready-to-be-grabbed’ status, in the process triggering governments in developing countries to create land as an investible resource. In our case, the construction of the Maji area as ‘vacant’ and ‘ready for investment’ is mainly the doing of the federal government. There were no major attempts to resolve the structural barriers to agricultural investment in the study area – such as improving road and other physical infrastructure, reducing conflict incidence, improving labour availability, putting in place irrigation facilities and the like – before advertisements of land for invigoration. Before agencies of the federal government advertised available ‘free’ land for potential, primarily foreign, investors, technological and institutional interventions were made to make the parcels easily visible and create the impression of readiness for investment. The grandest simplification was the use of satellite imagery to identify and map ‘free land’ and put the same in a federal (and regional) Land Bank. The investor then simply has to claim from the bank and invest. Although this process is mainly meant to attract foreign investment in the sector, the response was higher from domestic urban/business elite, often investing on much smaller scales.Footnote75

Situating the investments within the scope of its developmental state-building ambitions, the federal government went beyond its constitutional powers to administer land with little resistance from the regions or local governments. It is through such top-down, centrist and sometimes unconstitutional political impositions that the investments were made possible, and the investments in turn enabled the extension of the state’s power and authority to deeper parts of the Maji frontier. State power is mainly deployed to exclude existing and potential users, and is open for appropriation and redeployment by local officials, for contestations and counter-actions too. Global actors play a limited role in the politics of exclusion; it is the domain of national and local actors mainly. In Maji, as can be seen from the major conflict episode detailed in the previous section, ‘land grabbing’ resulted in violent conflict when local people resisted the various modes of exclusion. In what follows we highlight the main strategies adopted by the (federal/local) government to exclude the Suri. Counter-exclusion acts of the Suri led to tension and a cycle of violence.

The four dominant ‘powers of exclusion’ Hall et al. – i.e. regulation, force, the market and legitimation – are in play in our case too. Different levels of government advanced three forms of exclusion through regulation in the study area. Firstly, the regional and federal governments aimed to sedentarise the Suri, thereby aiming to regulate the Suri’s access to land, in addition to the stated objective of improving service delivery. The government’s intention was to turn agro-pastoralists into farmers, and have them rely on particular plots of land, which would later be titled and certified. In this process, the government is simultaneously excluding the Suri from accessing and utilising resources on the land transferred to the Koka plantation.

A second form of regulation is related to the nature of federal structure Ethiopia adopted. In effect, the Maji area could be conceived as a composite of ethno-territories for the different indigenous groups there, as Ethiopia’s federal experiment matches ethnic identity to territory. That is why the Suri contest the claims of the Dizi to the Banga forest (painting of trees and stones being a form of inscribing where Dizi ethno-territory ends, and as such excluding the Suri) and Koka plantation areas (be it in the form of to which Wereda land lease fees should be paid or who should benefit from the job opportunities created). Exclusion, or inclusion, in this case is mainly contingent on one’s ethnic identity. This however contradicts seasonal pastoral mobility as well as the longer-term northward drift of pastoral communities in the broader area, and aims to fix exclusionary ethno-territories. Although the contested land is a traditional Dizi territory, the Suri have de facto control now. Regulation through the promotion/maintenance of ethno-territories then favours the Suri if the de facto order is formalised, while the Dizi favour formalisation of the de jure order.

Third, the very process of identifying and advertising land for investment is putting such plots outside the realm of local land users, and under the ambit of government regulation. The contract investors enter with the government and their readiness to pay appropriate fees and taxes mean that the particular land they are leasing is under the regulatory authority of the government, not customary Suri/Dizi institutions. As such, both villagisation and leasing of land entrench state authority to govern land (and people), both with respect to investors and the local community and, more importantly, keep the local community away from land leased to investors.

Regulation with respect to land deals overlaps with the use of market forces to exclude both the Suri and the Dizi. The state is not interested in the subsistence economy of the local communities, rather the state’s interest is on the potential jobs created, revenue and foreign currency to be generated, and skills/technology to be transferred through the promotion of land deals. After all, these are the necessary components of the developmental state thinking. As such, accumulation through ‘land grabbing’ is realised by political interventions in the name of market-building, in the process inevitably dispossessing the local communities.

The above-stated strategies of exclusion are encompassed within and make up a part of the Ethiopian government’s broader, national-level legitimatising discourses and projects of ethnic federalism and developmentalism. These grand projects therefore serve exclusion through legitimation. The government presents ethnic federalism to mainly be about self-determination and self-governance of ethnic communities. Mistreatment and eviction of individuals and groups in the ‘wrong’ ethno-territory is as old as Ethiopia’s federalisation though. In effect, the dedication of territories to particular ethnic groups could only happen at the expense of others. Similarly, federal and regional governments framed land deals and villagisation under the rubric of development and service delivery, the end result being improvement in life conditions. These are framed as making a key contribution to reducing inequality between the centre and the lowland periphery, and at the same time as utilising the land and water resources of the area for the local and national good. This discourse and practice however is not accepted by members of the local community, particularly the Suri. The low legitimacy of the deployed exclusionary strategies adopted by the government meant that attempts to make the land leasing and villagisation projects benign and to make the local community acquiesce to the exclusion and dispossessions were unsuccessful.

This invites the use of force (or the threat of it) by the government as well as counter-claims and push-backs from the local community, i.e. counter-exclusion strategies. Government use of force – be it intimidation, use of blatant or subtle coercive power – in the name of development is not new in Ethiopia’s lowlands. The government pushed its extraction and sedentarisation ambitions mainly through force. Given the nature of the Ethiopian state, the very deployment of ‘an estimated 2000-strong contingent of police and Ethiopian army personnel in March 2014, complete with machine gun-mounted pick-up trucks’ will not be construed as being there to ‘protect Suri’.Footnote76 Rather, at the very least, the deployment is meant to intimidate and, if needed, for quick action against possible resistance. The memory of state violence against the Suri is alive, including the killing of ‘a few hundred’,Footnote77 in October 1993, following conflict with the Dizi, and later with government soldiers. A more subtle coercive strategy came in the guise of incentivising joining the new villages by distributing 25kg of maize every month. By linking food aid to joining the villages, the government is simultaneously creating a ‘free land’. In effect, what we see is the re-deployment of the government’s aggressive authoritarian developmental model in the Maji area to pursue ‘development’. ‘Development’ here is not mainly meant to improve the welfare of the Suri; rather, it is meant to increase the national economy. This ‘development’ comes at the expense of the Suri and other groups on the ground, and with total disregard for local resource access and utilisation dynamics, rights and cultures of concerned ethnic groups and before genuine consultation.Footnote78

The Suri do not have a menu of counter-exclusion strategies to choose from. They mainly resist forceful dispossessions and encroachments into their cultural space by employing force. Abbink also stated that the Suri resorted ‘to excessive force when they saw their political and cultural space being invaded by enemy groups and state agents’.Footnote79 Thus, the escalation of conflict is the result of the dominance of force as an exclusion and counter-exclusion strategy. The Suri are responding to the inherently authoritarian and violent nature of the ‘development’ advanced by the Ethiopian government.

Concluding remarks

This article aims to contribute to the understanding of local to global linkages by analysing conflict implications of land acquisitions. The article is based on a case study in the Maji area, located in the southernmost frontier area in Ethiopia, where (pastoral) the conflict has been among the defining features. Historically, extraction interests of the Ethiopian government evolved in response to the national and global situation from ivory to slaves, and with that the nature of conflicts evolved as well. The central role of global processes is restricted to the process of creating or diminishing the demand of certain commodities – in our case to increase in demand for arable land.

The global land rush and the consequent state action following the historical trend resulted in a tense security environment and the incidence of a higher number of violent conflicts in the Maji area. The global land rush created a suitable economic and political environment for the construction of land as an investible resource in the remotest parts of developing countries. However, global actors and processes could only reach the local through national (and sub-national) actors. In Ethiopia’s case, global actors met an enthusiastic national actor eager to extract from the lowland frontier through the already strongly held view that the lowland periphery is a resource frontier which needs to be valorised through state and private sector engagement. To this effect, the government assembled land as a resource worthy of investment. By doing this, the Ethiopian government is not only serving (foreign/domestic) agri-business interests. Rather, a long-standing process of extending state power and authority to the lowland frontier is enabled in the same process of promoting land investments and villagisation.

The assemblage of land as a resource, and investment on land, given its material conditions, is inevitably enabled by the exclusion of existing and potential users. Regulation and market forces, broadly under the nationally legitimate framings of ethno-linguistic federalism and developmentalism, were used as strategies of exclusion. As these exclusion strategies have low legitimacy, force dominated the menu of exclusion and counter-exclusion strategies. Thus, conflict was a logical outcome. In the final analysis, conflicts related to ‘land grabbing’ are not about land per se, but about the level of acceptability of exclusions. National actors have more say on the dominant nature of exclusions, while local government actors could also appropriate, adapt and redeploy the same in the name of advancing local (ethnic) interests.

While the strategies of exclusion and the legitimacy these have at the local level are contingent on political and economic dynamics at national and local levels, the reactions from below are determined mainly by the degree of political distance and peripherality of the local level vis-à-vis the political and economic centre. Moreover, strategies of exclusion are overlaid on extant political processes and dynamics, particularly claims to specific territories and coveted resources advanced on the basis of ethnicity. The superimposition of the strategies of exclusion over pre-existing territorial dynamics (i.e. ethnic federalism in the case of Ethiopia) has triggered/exacerbated conflicts related to ‘land grabbing’. Thus, local resource conflicts generated and/or exacerbated by ‘land grabbing’ are linked to the national level, as the government is the main actor in the exclusion of locals, and to the global level as it plays a crucial role in increasing the value of land, creating a land rush and making land an investible resource.

The policy implications of this study emanate from the recognition that exclusion of pre-existing land users – a necessary component in making land an investible resource – is at the centre of conflict generation/aggravation due to ‘land grabbing’. As such, actions to promote land investments should recognise the inevitability of exclusions and that different groups are affected in different ways and to different degrees. Thus the focus should be on making the strategies of exclusion less painful (or more legitimate), which contributes to dampening the risk of conflict.

This will be beneficial to the new land user as well as the local community. Otherwise, the pushback and (violent) resistance from the local community might get to the point of deterring the smooth functioning of investments. Therefore, it is in the interest of national and international actors, including investors, to recognise that conflict is a very likely outcome of their actions, and to conduct the various discursive and institutional interventions in a conflict-sensitive manner. As conflicts mainly relate to exclusions, the onus of having a conflict-sensitive approach mainly rests on national and sub-national actors, not the global.

When it comes to the timing, stressing that benefits will trickle down to the local community, through the execution of corporate social responsibilities and good practice, at a later point will make the costs of exclusion high and conflict more likely. The implication is that land administrators and investors should pay close attention to the costs of the exclusion of the local community and compensate for that before the actual alienation of the land, rather than postponing it to after the profits from the land investments come. Paying attention to the political nature of exclusions, to the social co-construction of land as a resource and to negotiating with the local community to reduce the costs will help prevent conflicts and enable firms to operate in a less hostile local environment. This, in effect, implies that the Ethiopian government should drop the practice of authoritarian developmentalism in the peripheral lowlands, and duly consider the rights, preferences and priorities of its citizens. The recent changes in political discourse, after the coming to power of the new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, gives some reason to be hopeful that the government will not be impervious to such policy recommendations. However, his most recent (on 29 July 2018) indication of the need for ‘more work on irrigated agriculture in the lowlands’Footnote80 warn us to be cautious and suspect that the government might continue to be impervious to such calls.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers and editors of the special issue for commenting on earlier drafts of this article. We thank Zeleke Kebebew for preparing the study area’s administrative map (Figure 1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tagel Wondimu

Tagel Wondimu Shanko is a lecturer at the Department of Civics and Ethical Studies, Mizan Tepi University. He used to lecture at the College of Social Science and Humanities of Wollo University.

Fana Gebresenbet

Fana Gebresenbet is an assistant professor at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University and a research fellow at the Centre for Gender and Africa Studies, University of the Free State. His research interests include politics of development, political economy, pastoralism and pastoral conflicts in the Horn of Africa

Notes

1. Mihyo, ‘Introduction’; Kalinda, ‘Acquisition of Lands’; Muluberhan, ‘Unintended Consequences’.

2. Mihyo, ‘Introduction’.

3. Deininger and Byerlee, ‘Rising Global Interest’; Mihyo, ‘Introduction’.

4. Kachika, ‘Land Grabbing in Africa’.

5. Dessalegn, Land to Investors; Dessalegn, ‘Large-Scale Land Investments Revisited’.

6. Ethiovisit, ‘Southern Nations’.

7. Buffavand, ‘The Land Does Not’; Muluberhan, ‘Unintended Consequences’; Tsegaye, ‘Listening to Their Silence?’.

8. FAO, ‘Voluntary Guidelines’; Vermeulen and Cotula, ‘Over the Heads’.

9. Schilling et al., ‘Introduction’.

10. Li, ‘What is Land?’, 590.

11. Ibid., 589.

12. Hall et al., Powers of Exclusion.

13. This paragraph heavily relies on the first chapter Hall et al., Powers of Exclusion. For the direct quotes in this paragraph see pages 4, 7 and 7–8.

14. Ibid., 9.

15. Li, ‘What is Land?’, 600.

16. Haberland, ‘An Amharic Manuscript’.

17. Federal Demographic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency, ‘Population Projection’.

18. Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’; Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Markakis, Ethiopia.

19. Bridge, ‘Resource Triumphalism’; Bach, ‘New “Centres” and New’; Markakis, Ethiopia: The Last Two; Puddu, ‘State Building, Rural Development’.

20. Markakis, Ethiopia.

21. Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’; Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Markakis, Ethiopia.

22. Abbink, ‘Changing Patterns’; Fernyhough, Serfs, Slaves and Shifta; Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’; Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Markakis, Ethiopia; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

23. Markakis, Ethiopia, 134.

24. Abbink, ‘Changing Patterns’; Abbink, ‘Conflicts and Social Changes’; Tornay, ‘More Changes ’.

25. Abbink, ‘Famine, Gold and Guns’; Gebre, ‘The Nyagatom Circle’.

26. Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’.

27. Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

28. Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued; Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’.

29. Cited in Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

30. Fernyhough, Serfs, Slaves and Shifta; Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’; Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

31. Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands.

32. Garretson, ‘Maji and the Ethiopian’; Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

33. Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography’.

34. Quoted in Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued, 365.

35. Fernyhough, Serfs, Slaves and Shifta; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued.

36. Fernyhough, Serfs, Slaves and Shifta, 161; Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued, 20.

37. Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’; Tishana is a collective Amharic name for natives living north of Maji. Hawkins cited in Salvadori identified them as the ‘Suru Tribe’, and the core group of the Tishana seems to have been Suri speaking. In contemporary times, Salvadori concludes ‘the people call themselves Me’en’ (Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued, 442).

38. Quoted in Garretson, ‘Vicious Cycles’, 212.

39. Salvadori, Slaves and Ivory Continued, 385.

40. Abbink, ‘Local Leadership and State’.

41. Abbink, ‘Famine, Gold and Guns’.

42. Abbink, ‘Famine, Gold and Guns’; Abbink, ‘Ethnic Conflict’; Abbink, ‘Violence and the Crises’.

43. Abbink, ‘Ethnic Conflict’; Abbink, ‘Famine, Gold and Guns’; Abbink, ‘Local Leadership and State’. The incidence report of the Bench-Maji Zone for the period between 2011 and 2016 also tells of a similar trend of gold being a conflict good.

44. Abbink, ‘Paradoxes of Power’.

45. Mosley and Watson, ‘Frontier Transformations’. While ‘high modernism’ indicates reliance on science and technology exclusively to order society and nature, ‘muscular high modernism’ merges the belief in science and technology with the use of coercive force. The latter is necessary to mainly push members of the local community into the ‘expert’ designed ‘simple, ordered, legible’ social and economic life.

46. Fana, ‘The Political Economy’.

47. For details on this see Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’.

48. Abbink, ‘Land to Foreigners’.

49. Unpublished data, Zone Investment Commission, October 2017. The number of deals are distributed across the period in the following manner: four before 2000; five between 2001 and 2006 (only one in 2006); seven in 2007; eight in 2008; six in 2009; two in 2011; one in 2012; seven in 2013; five in 2014; 14 in 2015; four in 2016, and the remaining two are not dated.

50. Dessalegn, Land to Investors; Dessalegn, ‘Large-Scale Land Investments Revisited’; Fana, ‘The Political Economy’.

51. Addis Raey, Unveiling the Rubbish Rhetoric.

52. Fana, ‘The Political Economy’.

53. Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’.

54. Dessalegn, Land to Investors; Dessalegn, ‘Large-Scale Land Investments Revisited’.

55. Dessalegn, Land to Investors; Dessalegn, ‘Large-Scale Land Investments Revisited’; Fana, ‘The Political Economy’; Ojot, ‘Large-Scale Land Acquisitions’.

56. Zone officials argue that the company left due to its own internal capacity weaknesses, not insecurity (Interview (first author) with Mr Abebe (pseudo-name), former Zone and regional senior administrator, member of the committee which followed on progress of the investment, Mizan-Aman, 7 May 2017. Others (Interview (first author) with Mr. Bayna (pseudo-name), a Dizi official, Maji Wereda administration, Mizan-Aman, 7 September 2017; Oakland Institute and Wagstaff) argue the reverse. In Ethiopia, the capacity and experience of foreign firms is checked more rigorously than domestic firms, according to Fana, and it is unlikely that capacity is the main issue leading the firm to abandon its interest. Oakland Institute, ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict’; Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’; Fana, ‘The Political Economy’.

57. See also Fana, ‘The Political Economy’; Human Rights Watch, ‘Forced Displacement and Villagization’; Oakland Institute, ‘Understanding Land Investment Deals’.

58. Bench-Maji Zone Pastoral Affairs Department, ‘Report on Activities’; Bach, ‘New “Centres” and New’; Interview (first author) with Mr Abebe (pseudo-name), former Zone and regional senior administrator, member of the committee which followed on progress of the investment, Mizan-Aman, 7 May 2017.

59. Meles, ‘Speech at the 13th’.

60. On Maji, see Oakland Institute, ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict’; Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’. On Gambella, see Human Rights Watch, ‘Forced Displacement and Villagization’; Oakland Institute, ‘Understanding Land Investment Deals’. On South Omo, see Human Rights Watch, ‘What Will Happen’; Buffavand, ‘The Land Does Not’.

61. Unpublished data, Security Administration Office, Bench-Maji Zone.

62. Oakland Institute, ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict’; Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’.

63. Oakland Institute, ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict’, 8.

64. Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’, 24. Our informants insist that it was Mr Daniel who the popular leader who was killed, not Mr. Sahlu, and that the officers did not use GPS.

65. Interview (first author) with Mr Kayzu (pseudo-name), resident of Tum area, among the very few educated Dizi and has been a civil servant since 1975, Mizan-Aman, 3 May 2017.

66. Interview (first author) with Mr Baruchagi (pseudo-name), a Chai Suri resident of Banga area, Mizan-Aman, 10 January 2017.

67. Interview (first author) with Mr Janchu (pseudo-name), expert at Zonal Security Administration Office, Mizan-Aman, 15 January 2017.

68. Interview (first author) with Commander Kebede Debebe, expert in Zone’s Civil Service Office, and used to work for the Zone’s Security Administration Office and for the Zonal Police, Mizan-Aman, 15 January 2017 and 7 May 2017.

69. Asnake, ‘Ethnic Decentralization’; Hagmann and Alemmaya, ‘Pastoral Conflicts and State-Building’.

70. Dereje, Playing Different Games.

71. Oakland Institute, ‘Omo: Local Tribes’.

72. Teklemariam and Tekeste, ‘DAG Recommendations’.

73. Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’.

74. FDRE, Rural Development Policies.

75. Unpublished data, Zone Investment Commission, October 2017.

76. Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’, 28.

77. Abbink, ‘Paradoxes of Power’, 166.

78. For further details on this see Oakland Institute, ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict’; Wagstaff, ‘Development, Cultural Hegemonism’.

79. Abbink, ‘Paradoxes of Power’, 170.

80. FBC, ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed’.

References

- Abbink, J., 1993. ‘Ethnic Conflict in the “Tribal Zones”: The Dizi and the Suri in South-Western Ethiopia’. Journal of Modern African Studies 31(4), 675–682.

- Abbink, J., 1993. ‘Famine, Gold and Guns: The Suri of Southwestern Ethiopia, 1985–91’. Disasters 17(3), 218–225.

- Abbink, J., 1994. ‘Changing Patterns of the “Ethnic” Violence: Peasant–Pastoralist Confrontation in Southwestern Ethiopia and Its Implication for a Theory of Violence’. Sociologus 44(1), 66–78.

- Abbink, J., 2000. ‘Violence and the Crises of Conciliation: Suri, Dizi and the State in South-West Ethiopia’. Africa 70(4), 527–550.

- Abbink, J., 2002. ‘Paradoxes of Power and Culture in an Old Periphery: Surma 1974–1998’. In Remapping Ethiopia: Socialism and After, eds. W. James, D.L. Donham, E. Kurimoto and A. Triulzi. James Currey, Oxford, 155–172.

- Abbink, J., 2005. ‘Local Leadership and State Governance in Soutwestern Ethiopia: From Charisma to Bureaucracy’. In Traditionand Politics in Africa: Indigenous Political Structures in Africa, ed. O. Vaughan. Africa World Press, Trenton, NJ, 177–207.

- Abbink, J., 2009. ‘Conflicts and Social Changes on the South-West Ethiopian Frontier: An Analysis of the Suri Society’. Journal of Eastern African Studies 3(1), 21–41.

- Abbink, J., 2011. ‘“Land to Foreigners”: Economic, Legal, and Socio-Cultural Aspects of New Land Acquisition Schemes in Ethiopia’. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 29(4), 513–535.

- Addis Raey, 2011. Unveiling the Rubbish Rhetoric of Land Grabbing. Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), Addis Ababa.

- Asnake, K., 2014. ‘Ethnic Decentralization and the Challenges of Inclusive Governance in Multiethnic Cities: The Case of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia’. Regional & Federal Studies 24(5), 589–605.

- Bach, J., 2009. ‘New “Centres” and New “Peripheries” in Post-1991 Ethiopia?’. Paper presented at ECAS-AEGIS, Leipzig, Germany. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.549.7419&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Bench-Maji Zone Pastoral Affairs Department, 2016. ‘Report on Activities of the 2015/16 Fiscal Year’. Unpublished, Mizan Aman, Bench-Maji Zone.

- Bridge, G., 2001. ‘Resource Triumphalism: Postindustrial Narratives of Primary Commodity Production’. Environment and Planning 33(12), 2149–2173.

- Buffavand, L., 2016. ‘“The Land Does Not Like Them”: Contesting Dispossession in Cosmological Terms in Mela, South-West Ethiopia’. Journal of Eastern African Studies 10(3), 476–493.

- Deininger, K. and D. Byerlee, 2011. ‘Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits?’. World Bank, Washington, DC. Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DEC/Resources/Rising-Global-Interest-in-Farmland.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Dereje, F., 2011. Playing Different Games: The Paradox of Anywaa and Nuer Identification Strategies in the Gambella Region, Ethiopia. Berghan Books, New York.

- Dessalegn, R., 2011. Land to Investors: Large-Scale Land Transfers in Ethiopia. FSS Policy Debates Series, no. 1. Forum for Social Studies, June.

- Dessalegn, R., 2014. ‘Large-Scale Land Investments Revisited’. In Reflections on Development in Ethiopia: New Trends, Sustainability and Challenges, eds. R. Dessalegn, A. Meheret, K. Asnake and B. Habermann. Forum for Social Studies, Addis Ababa, 219–246.

- Ethiovisit, ‘Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR)’. SCRIBD. Available at: http://www.ethiovisit.com/southern-nations-nationalities-and-people-%28snnpr%29/74/http://www.ethiovisit.com/southern-nations-nationalities-and-people-%28snnpr%29/74/ [Accessed 25 December 2017].

- Fana Broadcasting Corporation (FBC), 2018. ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed urged Ethiopians living in America to actively participate in national issues’. Trans. Authors. Available at: https://fanabc.com/ [Accessed 2 August 2018].

- Fana, G., 2016. ‘The Political Economy of Land Investments: Dispossession, Resistance and Trritory-Making in Gambella, Western Ethiopia’. PhD diss., University of Leipzig and Addis Ababa University.

- FDRE, 2001. Rural Development Policies, Strategies and Options. Ministry of Information, Addis Ababa.

- Federal Demographic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency, 2013. ‘Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014–2017’. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/343869975/Population-Projection-At-Wereda-Level-from-2014-2017-pdf [Accessed 25 December 2017].

- Fernyhough, D., 2010. Serfs, Slaves and Shifta: Modes of Production and Resistance in Pre-Revolutionary Ethiopia. Shama Books, Addis Ababa.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012. ‘Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security’. Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i2801e/i2801e.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Garretson, P., 1980. ‘Maji and the Ethiopian Domination the Southeastern Sudan’. In Working Papers on Society and History in Imperial Ethiopia: The Southern Periphery from the 1880s to 1974, eds. D. Donham and W. James. African Studies Centre, Cambridge, 89–122.

- Garretson, P., 2002. ‘Vicious Cycles: Ivory, Slaves and Arms on the New Majifrontier’. In The Southern Marches of Imperial Ethiopia: Essays in History and Anthropology, eds. D. Donham and W. James. James Currey/Ohio University Press/Addis Ababa University Press, Oxford/Ohio/Addis Ababa, 196–217.

- Gebre, Y., 2014. ‘The Nyagatom Circle of Trust: Criteria for Ethnic Inclusion and Exclusion’. In Creating and Crossing Boundaries in Ethiopia: The Dynamics of Social Categorization and Differentiations, ed. E. Susanne. LIT, Muenster, 49–71.

- Haberland, E., 1983. ‘An Amharic Manuscript on the Mythical History of AdiKyaz (Dizi, South-West Ethiopia)’. Africa Spectrum 46(2), 240–257.

- Hagmann, T. and M. Alemmaya, 2008. ‘Pastoral Conflicts and State-Building in the Ethiopian Lowlands’. Africa Spectrum 43(1), 19–37.

- Hall, D., P. Hirsch and T.M. Li, 2011. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press, Hawaii.

- Human Rights Watch, 2012. ‘Forced Displacement and Villagization in Ethiopia's Gambella Region’. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/01/16/waiting-here-death [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Human Rights Watch, 2012. ‘What Will Happen if Hunger Comes? Abuses Against the Indigenous Peoples of Ethiopia's Lower Omo Valley’. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/06/18/what-will-happen-if-hunger-comes-0 [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Kachika, T., 2010. ‘Land Grabbing in Africa: A Review of the Impacts and Possible Policy Responses’. Available at: http://www.oxfamblogs.org/eastafrica/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Land-Grabbing-in-Africa.-Final.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Kalinda, T., 2014. ‘Acquisition of Lands for Expansion of Sugar Production: Effects on the Livelihoods of the Magobbo Smallholder Farmers in Zambia’s Mazabuka District’. In International Land Deals in Eastern and Southern Africa, ed. P. Mihyo. OSSREA, Addis Ababa, 211–244.

- Kopytoff, I., 1986. ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process’. In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. A. Appadurai. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 64–91.

- Li, T.M., 2014. ‘What is Land? Assembling a Resource for Global Investment’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39(4), 589–602.

- Markakis, J., 2011. Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers. James Currey, Woodbridge.

- Meles, Z., 2011. ‘Speech at the 13th Annual Pastoralist Day of Ethiopia. Jinka, South Omo, Ethiopia’. Available at: http://www.mursi.org/pdf/Meles%20Jinka%20speech.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Mihyo, P., 2014. ‘Introduction: The Pros and Cons of International Land Deals in Eastern and Southern Africa’. In International Land Deals in Eastern and Southern Africa, ed. P. Mihyo. OSSREA, Addis Ababa, V–IX.

- Mosley, J. and E.E. Watson, 2016. ‘Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia’. Journal of Eastern African Studies 10(3), 452–475.

- Muluberhan, B., 2015. ‘Unintended Consequences: The Ecological Repercussions of Land Grabbing in Sub-Saharan Africa’. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 57(2), 4–21.

- Oakland Institute, 2011. ‘Understanding Land Investment Deals in Africa, Country Report: Ethiopia’. Available at: http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/OI_Ethiopa_Land_Investment_report.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Oakland Institute, 2013. ‘Omo: Local Tribes Under Threat: A Field Report from Omo Valley, Ethiopia’. Available at: https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/omo-local-tribes-under-threat [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Oakland Institute, 2014. ‘Engineering Ethnic Conflict the Toll of Ethiopia’s Plantation Development on the Suri People’. Available at: https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/engineering-ethnic-conflict [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Ojot, M.O., 2013. ‘Large-Scale Land Acquisitions and Minorities/Indigenous Peoples' Rights under Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia: A Case Study of Gambella Regional State’. PhD diss., University of Bradford.

- Pankhurst, R., 1997. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea Press, Lawrenceville, NJ.

- Puddu, L., 2016. ‘State Building, Rural Development, and the Making of a Frontier Regime in Northeastern Ethiopia, C. 1944–75’. The Journal of African History 57(1), 93–113.

- Salvadori, C., 2010. Slaves and Ivory Continued: Letters of RCR Whalley British Consul, Maji S.W. Ethiopia 1930–1935. Shama Books, Addis Ababa.

- Schilling, J., N. Engwicht and C. Saulich, 2018. ‘Introduction: A Local to Global Perspective on Resource Governance and Conflict’. Conflict, Security & Development, this issue.

- Teklemariam, S. and A. Tekeste, 2015. ‘DAG Recommentaions following South Omo and Bench-Maji Mission, DAG/OU/5/2015’. Development Assistance Group Ethiopia. Available at: http://dagethiopia.org/new/images/DAG_DOCS/South_Omo_Bench_Maji__signed.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2017].

- Tornay, S., 1993. ‘More Changes in the Fringes of the State? The Growing Power of Nyagantom, a Border People of the Lower Omo Valley Ethiopia (1970–1992)’. In Conflicts in the Horn of Africa and Ecological Consequences of Warfare, ed. T. Tvedi. Uppsala University Press, Uppsala, 143–163.

- Tsegaye, M., 2015. ‘Listening to Their Silence? The Political Reaction of Affected Communities to Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: Insights from Ethiopia’. Journal of Peasant Studies 42(3–4), 517–539.