ABSTRACT

Since the end of the Cold War, the topic of military role expansion has become commonplace in the literature. Military deployments in humanitarian crises, disaster relief, border patrol, policing, counterterrorism, stability operations, and state-building played a key role in new doctrine and organisational changes. Yet, this global trend towards role expansion met a very distinct context in Brazil. Despite transitioning from an authoritarian military rule, reducing military prerogatives in government, and rethinking military roles in society, this trend reinforced an embedded idea that the armed forces have a central and all-encompassing role in the state’s political, economic, and social development. This worldview derives from a Brazilian historical process of merging security and development that rose far before the discussions on the security-development nexus in the literature by the late 2000s. That said, the aim of this article is to discuss how historical political and military practices built a security-development nexus avant la lettre, in which the military played a key role. We intend to demonstrate how Brazil placed the military as a key development actor and how this process, over time, led to consequences for civil-military relations, public policies, and democracy

Introduction

Since the end of the Cold War, the topic of military role expansion has become commonplace in the literature. Military deployments in humanitarian crises, disaster relief, border patrol, policing, counterterrorism, stability operations, and state-building played a key role in new doctrine and organisational changes.Footnote1 Several of these expanded roles were seen worldwide as posing new challenges to civil-military relations.Footnote2 Yet, this global trend towards role expansion met a very distinct context in Brazil and Latin American countries. Like many western military organisations, Brazilian society had to transition from an authoritarian military rule, reduce military prerogatives in government, and rethink military roles in society.Footnote3 Nonetheless, in Brazil, this post-Cold War military role expansion reinforced the basis of the military in politics and social life; that is, an embedded idea that the armed forces have a central and all-encompassing role in the state’s political, economic, and social development and hence the military is the most competent institution to lead a national development project. This worldview derives from a Brazilian way of merging security and development that rose far before the discussions on the topic in the literature in the early 2000s.

Since the late 19th century, groups of society believed the military was the most effective state bureaucracy to lead national development policies, as if it was an island of effectiveness and competence within a sea of corrupt and inept state bureaucracies. Notwithstanding contributions to state modernisation, this complex dynamic had the nefarious effect of producing confusion on the range and scope of the concepts of defence and security in Brazil. Consequently, this all-encompassing view of military roles produced an inward focus professionalisation and several interventions in politics, ultimately leading to an authoritarian regime from 1964 to 1985.

This idea was not contextual but rather a result of a particular historical process of military professionalisation and state-building in the country as, even nowadays, Brazilian defence organisations continue to reflect this logic. Contemporary defence documents link defence and development as two faces of a similar coin in which one cannot exist without the other.Footnote4 Several defence procurement projects – such as the nuclear submarine or the border surveillance system SISFRON – are referred to as relevant contributions to national development, public safetyFootnote5 and national industries, but not necessarily as defence projects per se.Footnote6 These elements show a process of blurring the lines between security, defence, and development that directly affects our understanding of military and other state agencies’ roles. Even foreign policy topics are seen under the scope of the Armed Forces as part of their role in national development, as discussed by other articles in this Special Issue.

Yet, contemporary discussions of a security-development nexus would only take centre stage in the international aid, peacebuilding, and security literature by the early 2000s.Footnote7 Analysts argued that there is not only one single interaction between them. In fact, security and development practices can interact with one another in several distinct ways and may lead to distinct possible nexuses between them.Footnote8 In simple terms, these relationships can occur in four different domains: (1) policy, (2) empirics, (3) theory, and (4) discourse.Footnote9 Despite recognising these distinct possible outcomes for the security-development nexus, with few exceptions,Footnote10 a great deal of the literature is still overly focused on international aid and peacebuilding to support their analysis. Yet, notwithstanding the realisation that security and development can interact in several ways, domestic historical experiences of developing countries are still underexplored. We intend to demonstrate how the nexuses between security and development can occur at the domestic level and further affect decisions on military roles, security strategies and development and foreign policies.

That said, the aim of this article is to discuss how historical political and military practices can build a security-development nexus in which the military plays a key role. Our main research questions are as follows: How have political, social, and economic practices shaped merged security and development in Brazil? How has the Brazilian security-development nexus affected contemporary patterns of civil-military relations in the country? We use a case study methodology to understand the evolution of political discourse and practices of security and development in Brazil.Footnote11 We intend to demonstrate how Brazil placed the military as a key development actor and how this process, over time, led to consequences for civil-military relations, development policies, foreign policies, and democracy. We will also offer a framework for analysing the topic in contemporary Brazil, which will be used by other articles in this Special Issue.

As for our research methods, we use Brazil as a crucial case study. This is considered a ‘case that is seen as especially likely to make a valuable contribution to causal inference’, which can ‘confirm (most-likely case) or reject (least-likely case) a prior hypothesis’.Footnote12 Brazil is framed as a case of a domestic security-development nexus that places the military as a key development actor with all-encompassing roles in society. The country was chosen since the very idea of a binomial security-development interaction was a chief element of military professionalisation, state-building and contemporary military roles.Footnote13 Our case shows an example of security-development nexus avant la lettre. We define it as a set of practices, discourses, and intellectual perspectives that liaised security and development and placed the military as a key development actor with all-encompassing roles several decades before contemporary discussions on the topic took place. Contemporary problems discussed by the literature, such as the securitisation of development or the developmentisation of security, have been taking place in the country since the 1920s and still frame security discussions on military roles and development policies in Brazil.

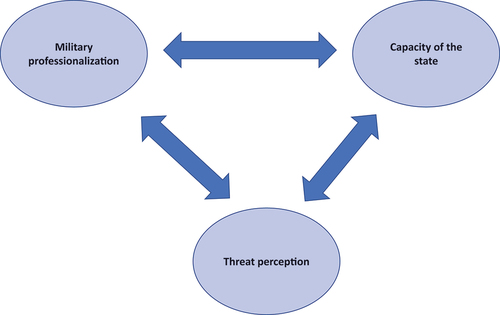

We engage with multidisciplinary literature to demonstrate how shared societal views of development and security are vital to shaping military roles and can affect democracy and public policies in several layers, such as defence and security policymaking, civilian agency capacities, and democratic controls over the military. To advance our argument, we will focus simultaneously on the four elements presented by the literature – policy, empirics, theory, and discourse – to show how intellectual and historical practices on state capacity and the role of the military were critical to liase security and development in the country. We build analytical framework composed by ideas, views, and practices on (1) state capacity, (2) the evolution of military roles, and (3) characteristic of security challenges as three key elements in shaping the security-development nexus in Brazil. Our focus lies on the historical construction of this nexus, highlighting practices on national development and security and illustrating how they continue to affect contemporary policies.

Given this background, our main argument is that Brazilian civilian, military, and societal elites have evolved to believe the state is ineffective in providing public policies and still see military engagement as legitimate in various non-security domestic roles and missions instead of developing capabilities of several other sectors—e.g. social programs, education, disaster relief, etc. This perception is generally supported by state inefficiencies and difficulties in providing public policies in several areas, by widespread disbelief in the Brazilian state and political system, and by a historical path of military professionalisation focused on domestic roles and missions. We understand that these blurred lines between military nation-building, state-building, assistance, and security roles can have three main harmful effects: (1) reduce incentives to institutionalisation and development of other state agencies; (2) reinforce trends of military intervention in politics in post-authoritarian states, and (3) distract the military from their core role: defence and contributing to a national security policy.Footnote14

Our article is divided into four main parts. First, we review the literature on the security-development nexus, present the contemporary trends for military roles, demonstrate the literature gaps, and present our alternate analytical framework. Second, we analyse the three elements of the security-development nexus in Brazil. We argue that there is a historical path that built a view of the military as a key modernising and nation-building actor in the country, resulting from a convergence of views on development and security from the military and sectors of the civilian elites with enduring social effects. Third, we discuss the contemporary consequences of this security-development nexus in Brazil. Last, we conclude by reinforcing our main argument, presenting the consequences of this process in Brazil, and showing new avenues for research.

The security-development nexus and contemporary military roles: a literature review

The realisation that ‘there is no security without development and no development without security’Footnote15 has only quite recently reached the centre stage of both the security and the development communities. Until the early 1990s, literature on economics – from different approaches – featured security as a subordinate or independent concept and vice-versa. From the outset of liberal economic thought to the Cold War,Footnote16 these two concepts evolved in parallel.Footnote17 Until quite recently, they were seen as independent factors in which only economic development could bring peace and ending violence. Nonetheless, different from the expected outcome, the history of Western states would show a paradoxical situation in which domestic peace would also bring total insecurity on a global scale.Footnote18

An important moment for this conceptual relation happened immediately after World War II when the geopolitical predicament and the fear of the spread of communism started to frame the interactions between the two concepts. Underdevelopment became a securitised concept as it was told to potentially foster communist insurgencies and unbalance the bipolar relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, especially in Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia.Footnote19 On the one hand, from the security side, development was seen as a security problem through the lens of the East-West conflict. On the other hand, the economic development thought considered security as a derivative or subordinate good—that is, insecurity was a development pathology as security was a precondition to development.Footnote20 The economic literature’s guns-versus-butter trade-off captures this idea of seeing security as a subordinate concept or a phenomenon separated from development. The concept refers to states having limited resources and, consequently, having to choose between investing in the military or socioeconomic development.Footnote21 As a result, the road towards economic development was seen as the solution to insecurity, a view that supported the post-war Bretton Woods institutions.Footnote22

The post-Cold War era would reframe how academics, governments, and international organisations dealt with the interaction between these two concepts. The change was one paradigm. Both the objects of security and development conceptions were moved from the state level to the individual level. Security, for instance, started to consider ‘the people living within them’, and the main consequence was the spread of humanitarian interventions and the internationalisation of the human rights agenda worldwide.Footnote23 The main driver of change was the rise of the human security concept, first presented in the UNDP 1994 Human Development Report. The new idea introduced concerns about freedom from fear at the individual level to the policy arena.Footnote24

These changes in the views of security also affected the view of military roles and missions worldwide and impacted changes in the armed forces of various countries.Footnote25 Militaries were expected to prepare to operate in complex environments with multiple state, non-state actors, and humanitarian actors and, in some cases, deliver non-traditional assistance to local populations. This was due to the change from the strictly defence-related and territorial-defence views that dominated the military agenda to a post-Cold War security environment and the exponential growth in peacekeeping operations worldwide.Footnote26 This was highly influenced by the United Nations, the U.S., NATO, and the European Union deployments in Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Within the U.S., for instance, it reinforced an ongoing trend of operations other than war and non-warfighting missions.Footnote27 As a result, military training and deployment would encompass a variety of distinct missions, such as peacekeeping operations, warfighting, disaster relief, internal security etc.Footnote28 Additionally, four elements played a key role in this role expansion: (1) the reduction of end geopolitical concerns with security assistance after the Cold War; (2) the widespread view that aid was not enough to prevent humanitarian tragedies, as seen in Rwanda; (3) the drastic reduction of interstate conflict in policymakers’ agendas immediately after the Cold War; and (4) criminal organisations and crime going beyond state borders and becoming transnational in nature.Footnote29

Together these conceptual and contextual shifts in the post-Cold War era would directly affect the policy community engaged in international aid. From the policy demands, donors, humanitarian organisations, international organisations, and local communities started to rethink the relationship between security and development. The international development community aimed to provide broader support than just economic aid or security assistance, a change that gave birth to an all-encompassing approach for post-conflict states.Footnote30 The new approach tried to reframe discussions on conflict resolution, which, at the time, were excessively focused on security or development approaches. The idea of a security-development nexus aimed to rethink the policy and scholarly agenda of post-conflict reconstruction, including essential insights from conceptual and political developments from the last few decades.Footnote31 Eventually, the concept supported essential changes in development policies from international organisations and donor countries’ policy circles as a more comprehensive and integrated approach took centre stage in the political arena.

The new approach also inspired several critiques. One of them refers to the excessive focus on security from development agencies and the growing concern of providing development from security forces, a problem referred to as the securitisation of development or developmentalisation of security. In other words, critiques focused on how this integrated and holistic approach could lead to an enlargement of development agencies and military organisations’ missions while dealing with complex problems. The main concern was, on the one hand, that strategic and security objectives were hijacking the goal to reduce social inequalities; and, on the other hand, that militaries were engaged in missions that they were not fit for. For instance, during the U.S. War on Terror, several countries were offered aid through the Department of Defence, and most of the development assistance was channelled through the military. Similarly, the British Aid Strategy in 2010 presented the main objective of increasing aid in areas of interest for the UK national security – intrinsically relating the international development strategy to that of national security.Footnote32

Humanitarian studies also criticised this phenomenon of blurring the lines between military and aid agencies and the use of development policies to achieve military goals in conflict. According to them, unclear borders between security and humanitarian actors could ultimately undermine the trust of local agents in humanitarian policies and negatively affect the principle of neutrality, impartiality, independence, and humanity.Footnote33 Last, orthodox critics would focus on the effectiveness of the strategy. Many authors criticised the approach of developing strategies that merged security and development and questioned their relevance in achieving their goals. In their view, these strategies tended to be ineffective as they were based on contested concepts.Footnote34 Within this orthodox critique, some also argued that the security-development nexus strategy depoliticised foreign policy planning and decision-making with negative effects on donor countries’ policy ambitions. In other words, the nexus represented an independent liberal declaratory ambition to support change in non-Western states and a means to avoid traditional foreign policymaking responsibilities.Footnote35

Despite some important scholarly contributions to the evolution of the concepts of security and development,Footnote36 most studies are focused on the donor’s perspective and on the international arena. There are still few pieces that discuss the domestic dimensions from a non-donor perspective.Footnote37 Although some authors highlight the importance of spatial, temporal, and geographical location as key to understanding the differences in historical trajectories of security and development in different countries,Footnote38 the historical relationship between security and development actors is still underdeveloped in the literature.

Yet, the idea of the historical evolution of development and security practices affecting national policies in developing states is not new. Studies within the security studies literatureFootnote39 have already recognised this problem long before discussing the security-development nexus. They stressed that the capacities of the state and the evolution of military professionalisation in some countries could affect their views of security and vice-versa.Footnote40 In general, they posited that the security predicament in developing states was intertwined with the process of state-building. Within this perspective, security is directly related to ‘vulnerabilities’, both internal and external, that threaten to, or have the potential to bring down or significantly weaken state structures, both territorial and institutional, and regimes’.Footnote41 These studies also related the difficulties of state-building to regional interstate dynamics and the historical process of military development.Footnote42

In other words, some elements were considered key to understanding these dynamics in developing states – such as (1) the historical process of how militaries develop their doctrines and capabilities (centralised, decentralised, offensive, defensive doctrines); (2) the military focus developed over time (internally or externally oriented); (3) relations with ancillary state and security institutions (recruitment, education, claims on economic resources etc); (4) and how society develops its concepts of security. Other authors pointed out the role of internal legitimacy and reinforced the role of policy capacity to understand the evolution of national security in developing states.Footnote43 They would reinforce the chief role of the ‘software side’ of security management, defined as the political context, policy capacity, how threats and vulnerabilities are assessed, resources allocated, and policies implemented. In other words, one should understand (1) how legitimate the security agency’s actions are; (2) how integrated into society the process of determining national interests; and (3) how capable the state is of implementing and generating policies.

Ultimately these studies highlight those views on state power and its general capacity to implement policies should take centre stage in understanding how security policies are formed and how they affect/are affected by other policies. These elements are important to understanding the Brazilian view of a security-development nexus. Most Latin American states do not represent failed states but weak ones.Footnote44 In other words, several of them have a functioning bureaucracy and, in some areas, very effective ones. Nonetheless, these states tend to have an overall limited state power in its four main dimensions: (1) territorial, (2) economic, (3) infrastructural, and (4) legitimacy.Footnote45

Liaising security and development: a framework for analysis

In the case of Brazil, a historical path led to a long perception of the lack of effectiveness of the state bureaucracy or a view of these governmental elites as patrimonial. In other words, a state poisoned by clientelism, personalism, corruption,Footnote46 and the difficult distinction between the public and private spheres.Footnote47 Thus, worldviews of internal fragility, the inaptitude, and patrimonial views of the civilian politicians, and of a state captured by oligarchic interests or corrupt politicians inspired military intervention in national policies/politics and developed a shared view of the military organisation as a key modernising actor. As a result, throughout the 20th century, Brazil created a particular version of the security-development nexus intertwining national security, foreign policy, defence, industrialisation, and development policies.Footnote48 Overcoming the condition of underdevelopment, strengthening the state, and achieving economic development became key elements of national security and defence according to the Brazilian economic, military, and political thought.Footnote49 This nexus enlarged military roles and affected/were affected by views on military professionalisation. That is, instead of an externally oriented military force, Brazil professionalised its army with an inward focus.Footnote50

Some authors explain this military engagement in society and politics because of the modernisation of military organisations that placed rather complex and European-style bureaucracies in pre-industrial societies.Footnote51 Others point out that this view was developed before the European missions as the military in Brazil was conceived as a modernising actor for society and the state in rather agrarian and oligarchic societies – and not necessarily as a warfighting bureaucracy. This was due to the armed forces having state-like institutions far before other state bureaucracies; hence these distinct rates of modernisation between the state and the armed forces would explain a far-reaching military engagement in society and politics.Footnote52

Regardless of the interpretation, views on the reduced state capacity – defined as the strength of the state to extract resources, implement public policies, build infrastructure, and control violence, law, and order in territoryFootnote53—facilitated military engagement in several sectors of the state and society. The military would be involved in infrastructure, science and technology, communications, transport, building bureaucracies, and even representing the state in far-reaching areas or in the international arena. Ideas of low state capacity to provide policies and inaptitude of civilian politicians were used to justify elite support for military expanded roles. Consequently, the key factor for building this nexus in Brazil was not necessarily the actual capacity of the state but, rather differently, how civilian/military elites perceived both state power in relation to that of the military and the military contribution to enhancing the capacity of the state.Footnote54

The low-state-to-state security threat the country faced throughout the 20th century was also a relevant factor in shaping the security-development nexus. Brazil’s last conflict in South America was the Paraguay War between 1864 and 1870 and the Acre war in 1903. The country also contributed to World War I and to World War II,Footnote55 with a large contribution of 25,000 troops to the latter.Footnote56 Yet, this has not been enough to shape society’s perception of the need for an outward-focused military. Nonetheless, the growing domestic and transnational security challenge, such as the growing urban violence, would reinforce the already in place inward-focused military role.Footnote57 Like several other Latin American countries, the main threat perception of the Brazilian society comes from state weakness, public safety, transnational organised crime, and insecurity in megacities, but not necessarily from traditional interstate war.

In contemporary Brazil, this trend was worsened by the rise of strong transnational organised criminal organisations, fragile and not transparent police forces, and local powers’ incapacity to deal with the problem. As a result, civilian governments have pressured and pushed for the deployment of the military to deal with security problems.Footnote58 Yet, despite this social pressure, several authors discuss there is a security gap that demands neither military nor police-like forces, but intermediate capabilities from both as challenges are below the military level and beyond the police capability,Footnote59 and, to truly face these complex problems large national security management capabilities should be developed.Footnote60 Once again, even in the contemporary era, the discourse of state capacity plays a central role.

That said, we believe that the interaction between the need for socio-economic development, low levels of state capacity in several dimensions, internally focused military professionalisation, and the low-intensity state-to-state threat perception paved the way to a specific form of security-development nexus in which the military was seen as a legitimate national development actor. Hence, we believe that to understand the evolution of a security-development nexus in Brazil properly, one needs to understand the relationships among discourses, ideas, and practices on (1) the capacity of the state, (2) military professionalisation, and (3) society’s threat perception, as presented in . The articles in this Special Issue will analyse distinct dynamics from this interaction in Brazilian society, military, diplomacy, and other areas.

The historical formation of a security-development nexus in Brazil

The Brazilian version of a security-development nexus started to take shape in the early 20th century in the newly established Republic.Footnote61 From 1822 to 1889, imperial Brazil had already built a general sense of statehood that, differently from Spanish Latin America, achieved territorial unity, effectively repressed separatist rebellions, and started to create a national identity.Footnote62 Dissident elites would come to criticise the regime for political instability, corruption, electoral fraud, clientelism, economic problems, incipient industrialisation, and oligarchic structure.Footnote63 As a result, they believed that the military was the most qualified organisation to lead the development process in Brazil.Footnote64 Three events were key to shaping this idea: (1) the legacy of the positivist ideas on young officers at the end of the Empire; (2) the process of military professionalisation resulting from the German and French missions and the end of World War I; (3) the consolidation of a military conservative modernisation project for the country between the 1910s and 1930s; and (4) legislative changes over the 1930s and the civil-military alliance during the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship from 1937–1945.

In the Praia Vermelha Military School, the main Army Academy, which functioned from 1874 to 1904, young officers grew to develop strong scientific, meritocratic, and republican views that challenged the current hegemony of Bachelor of Law in the Brazilian elite. This post-Paraguay War generation of officers was directly influenced by positivist ideas spread by the military thinker and instructor at the Military School, Benjamin Constant Botelho Magalhães.Footnote65 These positivist youngsters came to be known as doutores or bacharéis for their scientific education. They represented the opposition to the veterans of the Paraguay War, known as tarimbeiros, who were more focused on military training and did not agree with the new scientific teaching methods.Footnote66 The young officers did not see the school as only a military school but as an institution that attempted to rival civilian academies by studying mathematics and other sciences.Footnote67 They believed they had a role in modernising society and the positivist ideas were a way to surpass a society based on privilege, backwardness, and the past.Footnote68

Therefore, the doutores supported the rising idea that the military could and should lead a national development project. They had a Republican project for Brazil and would be instrumental in the coup against the Empire in 1889 and the first military governments of Marshall Deodoro da Fonseca (1889–1891) and Marshall Floriano Peixoto (1891–1894). However, the military, political, economic, and social difficulties of the first republican governments would make them lose political space. Over time, the original youngster’s project was unsuccessful in changing the military values of the Army or national politics as oligarchies from São Paulo, and Minas Gerais took centre stage in the new regime. Additionally, their military ineffectiveness during the Amazon and the Acre campaignsFootnote69 and engagement in Army and national politicsFootnote70 would lead the Praia Vermelha Military School to be shut down in 1904 by the civilian government of the São Paulo politician Rodrigues Alves. Yet, despite these difficulties, the young doutores’ movement was instrumental to the rising idea that ‘an enlightened military group was able to save the Nation, in its name’.Footnote71 This vision would become prominent and grow stronger in the following decades. Some political elites would argue that the military ‘should be given not only the political mission of modernisation but also that of organising society into a military structure’.Footnote72 This idea would become stronger as military modernisation efforts took place in the 1910s and the 1920s.

In 1913, a group of military officers would go for instruction in Germany to learn more about the German military organisation. Once they returned, some of them also would be placed in the Realengo Military School – the successor of the Praia Vermelha Military School – to teach these new ideas.Footnote73 They also founded the journal A Defesa Nacional to publicise technical ideas about military reform and political views on their national development project.Footnote74 Prominent intellectuals in the country, such as Olavo Bilac and Rui Barbosa, would write in the journal and promote the idea of the citizen-soldier. That is, they would argue that the military should be allowed to vote and defend the idea of a compulsory conscription system claiming that every citizen should take part in defence of the nation.Footnote75

The process of professionalisation gained more momentum after World War I. In 1918, the Brazilian Army hired a French mission to modernise their structures and implement a new doctrine. As a consequence, the organisation reformed the Army General Staff, between 1918 and 1919 created new disciplinary rules and controls to avoid hierarchical problems and created compulsory military service in 1923.Footnote76 The old National Guard, an ancillary force supported by the regional and local elites, was also extinguished in 1922. This modernisation reinforced the idea of expanded military roles that should go beyond civic action and nation-building towards a civilising mission.Footnote77 That is, more than protecting the state, the military developed the idea that they had a role to bring modernity and civilise the agrarian Brazilian society, a vision that led to several strands of political thought within the Army. Ultimately, there were disagreements and revolts within the force as well as important political interventions over the 20th century () until one unifying military project became hegemonical within the Army and the state. It is important to mention that, after the two first presidents of the Brazilian Republic, both Mariscal and not elected, two military were elected president of the country: Hermes da Fonseca, from 1910–1914, and Eurico Gaspar Dutra from 1946 to 1951.

Table 1. Army revolts and political movements in BrazilFootnote78.

Despite the existence of opposing viewsFootnote79 within the military,Footnote80 the modernisation process paved the way for the construction of a unifying corporative ideology of intervention in policy/politics: a military-led conservative and centralising national development project. The idea behind this view was that national security and defence should rely on a strong government capable of leading an industrialisation process and national development. Only a strong and centralised state with a national project could promote industrialisation, autonomous technological development, and economic development and turn Brazil into a truly sovereign country.Footnote81

A key proponent of this project was General Goés Monteiro, a right-wing and anti-liberal officer who was instrumental in the victory of the dissident oligarchies in the 1930 movement and the 1932 civil war. He also took centre stage in establishing the Estado Novo, the civilian dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas in 1937.Footnote82 Goés Monteiro’s worldview was one of conservative modernisation and opposition to liberal politics, summarised in four main points: (1) the state is the predominant factor in political life; (2) the state should centralise and build a national policy; (3) to develop and train elites to direct the state; (4) the armed forces were the most prepared, nationalist, and organised eliteFootnote83 within the country.Footnote84 At the time, this perspective represented a victory of a right-wing and conservative vision of the political role of the Army in society and national life in the following years, but disputes within the Army would still remain.Footnote85

Politically, this approach would be gradually implemented because of a convergence of views between Goés Monteiro’s military group in the government and the new modernising ambitions of the civilian leader Getúlio Vargas. The process would start in 1930 as a presidential succession crisis took place. The traditional oligarchic groups, represented by São Paulo and Minas Gerais elites, had won the election against Getúlio Vargas – which represented an alliance of dissident oligarchies from other states. Several claims of illegality and irregularity led the armed forces to intervene, remove the president elect Julio Prestes from power, and establish a provisory government under the opposition leader Getúlio Vargas. The new provisional president, the military, dissident oligarchies, and some economic elites were united in claiming a centralised and strong government.Footnote86 Consequently, to avoid ceding power to regional oligarchies, the Vargas administration (1930–1945) incentivised the transformation of the armed forces into a political actor and used it against the oligarchs.Footnote87

Hence, this modernising civil-military pact that slowly took shape to actively start in 1937, under the Getúlio Vargas’ Estado Novo dictatorship. In general terms, the practices and concepts posited that national security relied on an industrialising project led by the state.Footnote88 To continue receiving support from the military, Vargas allowed important changes in legislation that would subvert the idea of civilian control.Footnote89 A few of these changes were: (1) the decision that all industries should provide information to the Ministry of War about their capabilities and development; (2) the new Constitution and creation of the National Security Council in 1934; (3) the National Security Law in 1935; (4) the creation of the National Security Court. As a result, military role in politics and national development grew substantially. From a simple need to inform the military about the development of certain industries in 1931, ‘the military acquired stake-holding and decision-making power over not only military budgets, training, and the armament but also over industrial development’Footnote90 by 1945.Footnote91 Thus, this moment was key to grant the military a key role in the Brazil’s development policy.

Yet, the Brazilian security-development nexus was not only built by the growing perception of a military modernising role. In fact, convergence amongst intellectuals, economists, and military elites towards a national modernising project were also crucial.Footnote92 Economic thinking from the 1950s and 1960s also played a key role. The Vargas era socioeconomic approach to modernising and industrialising the state, was supported by rising strands of Brazilian economic and development thought. In the 1950s, for instance, several intellectuals built upon the industrialising experience to sharpen a strategy capable of overcoming underdevelopment. Important academics, such as Celso Furtado, Helio Jaguaribe, Nelson Werneck Sodré, Roberto Campos,Footnote93 were instrumental in creating the national developmentalism ideology.Footnote94 This worldview focused on the transformation of Brazilian society focusing on state-led economic planning, developing specific economic sectors, industrialisation, and attracting resources to finance development.Footnote95 Though there were different strands of developmentalism approaches,Footnote96 the strategy of import substitution, protectionism, developing domestic markets, and searching for foreign capitals was shared among them.Footnote97

Therefore, although these developmentalist intellectuals did not share the authoritarian nature of Goés Monteiro’s project, they did share the same diagnostic: Brazil had key state fragilities that should be tacked with a new state-led development strategy to induce social, economic, and science-technology change. Consequently, different governments during Brazil short liberal democracy experience, between 1945 to 1964,Footnote98 would focus on modernisation and benefit from military contributions to it. For example, between 1950 and 1964, military officers were directly involved in the development of key national industries and Research & Development (R&D) institutions. A few examples are the National Council for Scientific and Technologic Development (CNPq) created by Admiral Alvaro Alberto Neto in 1950;Footnote99 the Institute of Aeronautic Technology (ITA) in 1950;Footnote100 the Military Institute of Engineering (IME), in 1959;Footnote101 and even the creation of the national oil company Petrobrás, in 1952, had the support of nationalist military officers.Footnote102

In this period, the conservative military wing also tried to build its own project. After the experience of fighting a totalitarian regime in World War II with the Força Expedicionária Brasileira, pressures inside Brazil grew to end the Estado Novo dictatorship. Thus, the same military group that supported Vargas and gained several prerogatives during his government ended up ousting him in 1945. Nonetheless, the former president and dictator still had large popular support for his several labour and social reforms. From 1945 onwards, officers who visited the United States decided to create a new institution mirroring the country’s National War College. However, instead of training high-rank military officers, the new institution was conceived as ‘a governmental military think tank where the conservative and authoritarian sectors of Brazilian society re-elaborated their modernisation project to suit the change of regime’.Footnote103 As a result, the new Escola Superior de Guerra (ESG) would develop the National Security Doctrine, a key document for the military authoritarian regime of 1964 to 1985. This doctrine also liaised security and development; highlighted the need for modernisation; reinforced the key role of the military as a modernising actor; and posited the need to overcome parochial interests in the Brazilian government.Footnote104 Nonetheless, it also had direct influences from the U.S. interests in the hemisphere and hence had strong ideological anti-communist traits to defend Western-Christian values against Marxism.Footnote105

These anti-communist ideas and the worldview of conservative modernisation ultimately supported to the civil-military coup in 1964 and the 21 years of military regime. Several of the military governments used the slogan of security and development as key to their approach to politics. As a result, if before the military had kept the prerogatives on security and defence from the Estado Novo dictatorship, during the new military regime, there was ‘an extraordinary degree of legally sanctioned prerogatives and bureaucratic autonomy found neither in other democracies nor in the other bureaucratic-authoritarian regimes’.Footnote106 A key element of these policies was a strong internally-oriented intelligence service named the Serviço Nacional de Informações (SNI), the central intelligence service. Under this national security state, the SNI had representatives in every ministry and in key governmental agencies and built a large intelligence structure focused on monitoring its citizens.Footnote107

Similarly, important Brazilian geopolitical thinkers also highlighted how development was a key element of national security and placed the problem of national integration and civilising distant areas,Footnote108 and regions like the Amazon were key to their view.Footnote109 The application of the ESG and a few geopolitical principles to the military government led to important infrastructure and science and technology projects. The military regime’s nationalist and technocratic view of development reinforced the role of the state in every sector of the Brazilian economy and created key infrastructures and projects, such as telecommunications, energy, ethanol fuels, new state companies etc.Footnote110 A key example was the creation of the national aviation company Embraer, in 1969, a leading company in the sector and, to this date, one of the only of its kind in Latin America.Footnote111 Yet, the same model led to massive debt, and the authoritarian nature of the regime, political persecutions, and lack of liberties would lead the regime to end in 1985.

To sum up, between the 1910s and 1980s, Brazil intertwined the concepts of security and development based on the diagnosis that the Brazilian state and society was underdeveloped and lacked state capacity, that Brazil needed a large process of industrialisation, state modernisation; Brazil needed to develop autonomous capacities in science and technology; and the military were key modernising actors. Ideas on national security were intertwined with state modernisation and economic development. National elites came to believe that without industrial, societal, and technological development, the country would not achieve a condition of national security. This process was accompanied by a growing view of the military role in society and social life. The armed forces were not seen only as a supporting actor in development but rather as the key and most competent actor to do so. The main consequence was also a growing interference of the military in politics that ultimately led to the military interventions during the 20th century. Hence, differently from the contemporary view on the security-development nexus, the Brazilian security-development nexus posited a centralised and state-centric strategy to induce a specific form of economic development – industrialisation and establishing research and development capabilities. This strategy was under a conservative notion of national security in which social life should be scrutinised under military principles and values – in other words, ‘national security’ was ‘state development’.Footnote112

Contemporary effects of the Brazilian security-development nexus

Over time, a few elements of this idea would change. Yet, the foundations of this worldview would remain. That is, Brazilian society, elites, and institutions are still influenced by the ideas that the military has a key role in national development, the state lacks the capacity to provide public policies effectively, and Brazil is ruled by corrupt elites with parochial interests. These ideas are indeed affected by the difficulties the country still faces, such as corruption scandals, rising crime levels, and recurrent economic crisis. Additionally, the worldview of an intricate relation between defence, security, and industrial and economic development is also a strong element affecting Brazilian national defence strategies. In contemporary Brazil, this idea of a security-development nexus still exists, albeit with a different format. Since the 1988 Constitution, ‘the term national security practically disappeared’ and was substituted by the idea of defence.Footnote113 The security-development nexus changed to a defence-development nexus. This interaction is present in contemporary Brazil in two distinct forms: (1) the idea that investments in defence contribute to economic development and (2) a trait of enlarging military roles in other national policies.

Brazilian defence policies and strategies illustrate this worldview. The 2008 and 2012 National Defence Strategies posit that the national defence strategy and the national development strategy are inseparable’.Footnote114 Similarly, the 2016 and 2020 National Defence Strategies reinforce this idea and posit ‘defence depends on the country’s existing capabilities’ and ‘contributes to maintaining and improving its resources’.Footnote115 In all of them, there is an embedded view that investing in the idea of a defence industrial base would contribute to national development, generating resources and income, and reducing unemployment. Defence procurement projects, for instance, such as the Border Monitoring System (SISFRON) and the Nuclear Submarine (PROSUB), are justified to society in terms of their contribution to national development.

Although several countries use the resource, jobs, and industrial policy as a justification for complex procurement policies and technological investments, the Brazilian case has additional problems. As we have presented so far, Brazil has developed over time a view of the military as a key development actor. This would not be a problem if the country placed effective civilian controls and clearly defined missions for the military after the authoritarian military regime. Nonetheless, Brazilian ‘did not tackle several military prerogatives, did not properly civilianised structures in intelligence and defence, or even presented effective political direction’ for the military.Footnote116 Under a low interstate threat environment and absence of incentives to engage on defence policy, weak political controls over the military, and a widespread belief of the military as a key development actor, the view of procurement projects as industrial development projects can reinforce confusion on the concepts of defence, security, and development.

The second case is represented by enlarging military missions to reinforce non-traditional military missions per se – such as public safety or border security—, nation-building, and civic-actions.Footnote117 The current engagement of the Brazilian military in public safety is a problem identified by several scholars.Footnote118 Most of them agree that civilians have been pushing the military to engage in public safety and fighting organised crime. The main reasons are due to problems such as police corruption, growing strength of criminal organisations, and lack of capacity of other state agencies.

Yet, this civilian push is not restricted to security issues. Legislative changes have also taken place in the mission of support to national development. In Brazil, this concept has been framed as ‘cooperating with national development and civil defence’.Footnote119 From 2004 onwards, this mission was even expanded by civilian politicians to ‘participate in institutional campaigns of public or social interest’ and ‘to cooperate with public organisations and occasionally with private companies to execute engineering activities’.Footnote120 Hence, the military is constantly demanded to activities such as: building roads and other national infrastructure when demanded; to contribute to the fight against epidemics; support to education of indigenous populations and areas of difficult access; distributing water in draught-affected areas; to contribute to other social policies when demanded.Footnote121

Although the military can have important contributions to the state,Footnote122 the problem of engaging them in public safety or recurrent support to development missions lies on developing a cycle of over-reliance on the military to provide complex policies.Footnote123 In contemporary Brazil, there are several examples of public policies that have been militarised – as in led by the military or with great military influence – without a proper development of other civilian agencies. Differently from the period 1910–1985, now there are cases of militarisation of social and other policies without necessary securitisation or military tutelage. That is, there is a civilian push for military engagement in several policy areas without the exceptional discourseFootnote124 that securitisationFootnote125 entices. Although it may depend on the policy design, overall, it can have a negative effect on democratic institutions and de-incentivise the construction of effective civilian agencies and cause ‘democratic deficits’.Footnote126 Some authors have defined the nefarious effect of this overreliance on military capabilities. Studies show that repeatedly using the military in public policies drove Brazil to a worldview of ‘mythologisation of military capabilities; that is that the military is, ‘by nature, more reliable than civilians in dealing with public affairs’, as defined by Carvalho and Grimaldi.Footnote127 According to this perspective, a mythological view of military capabilities can pose a major risk because ‘as the military begins to take on the role of what are civilian activities, it will inevitably suffer from the same disbelief that civilian powers are victims of’.Footnote128

Additionally, overreliance on non-traditional military missions can also divert efforts from military training and deployment on territorial defence. Some argue that inter-agency roles focused on nation-building missions have a negative effect when applied to Brazilian reality: it can reinforce groups within the armed forces that see themselves as the guardians of the Republic and reinforce a historical trend of intervention in politics.Footnote129 There are several examples of this problem. In 2004, civilian politicians gave to the military the mission to distribute water in draught-affected areas in the Northeast Brazil as a temporary mission, the infamous Operação Carro Pipa. Despite being a temporary mission, now, almost 20 years later the army continues to be the responsible for this activity.Footnote130 Other examples are the military reliance on fighting deforestation and Amazon fires, the Operação Verde Brasil; the fight against the pandemic of COVID-19; the military involvement in public safety; the management of the refugee crisis in the border with Venezuela.Footnote131 In all these cases, Brazil does have other agencies capable of supporting these activities but their vulnerabilities – or views about their lack of capabilities – reinforce ideas of more military engagement.

Even in aspects that should be seen purely under a professional military dimension, such as the participation of troops in Peacekeeping operations under the UN flag, the Brazilian military ‘exported’ this understanding of the security-defence-development nexus. From 2004 to 2017, Brazil led the military side and had the biggest contingent of troops in the United Nations Mission for the Stabilisation of Haiti (MINUSTAH). The narrative constructed all over these years was that Brazilian troops were providing security and, at the same time, promoting the development of the Caribbean nation, promoting engineering works that would support the infrastructure of the country. Ultimately, there was a discourse of a Brazilian way of peacekeeping based on the idea that the Brazilian military had experience with development practices, which would be exporting their domestic practices. Nonetheless, as studies show, the Brazilian Army did not export best practices but rather imported a ‘robust turn’ of peacekeeping operations to search for operational leeway in domestic public safety operations.Footnote132

Most recently, this also led to a growing military involvement in politics. Over the post-1985 Republic, Brazil reinforced military roles in public safety and other eras whilst not providing effective civilian controls or security and defence management.Footnote133 Hence, since 2013, Brazil has seen a growing delegation of civilian posts to active-duty and reserve military personnel, reaching its peak between 2019 and 2022 under the government of retired Army captain Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2022).Footnote134 Between 2016 and 2020, there was a growth of 108 per cent of military personnel in civilian roles and an even larger growth of 186 per cent between 2013 and 2021.Footnote135 The unprecedented number of military officers in political roles and in control of public policies led some to define it as a ‘stealth military intervention’; that is, a kind of military contestation, separate from both the existing typology of coups or erosion of democratic institution, in which the military slowly take control of key areas of government and society under the civilian elites agreement.Footnote136

Conclusions: the military as a modernising and nation-building actor?

The Brazilian narrative of the intricate relationship between security, defence, and development has had overarching effects on the state and society and still affects several security and non-security institutions. Since the early 20th century, civilian and military elites built a core security-development nexus to support bureaucratisation and state modernisation; produce cutting-edge science and technology industry; advance conservative approaches to national development; and enhance the military role in society and politics – ultimately, leading to two authoritarian regimes: 1937–1945 and 1964–1985. Our case shows what we define as a security-development nexus avant la lettre; that is, an example of merging the two concepts before discussions on the topic rose with enduring consequences. The Brazilian security-development nexus avant la lettre postulated that national development was the main national challenge, and all national institutions should work to induce it. Based on conservative notions of security and national development, this nexus was the background for state-led industrialisation policies and security policies and began to take shape at a time when the Brazilian state lacked public policy capacity, an effective bureaucracy, and state power was captured by regional oligarchies. Consequently, civilian and military elites developed a positive view of the growing military involvement in state affairs and non-security-related public policies as the armed forces were an important political ally or opponent to politicians.

Even after democratisation in 1985, despite changes in the character of the narrative, the underlying ideas of this policy, theoretical, empirical, and discursive security-development nexus continued to shape security and defence policies in the form of enlarging military missions – support of national development, civil defence, and public security – and to justify investments in large defence projects, such as the nuclear submarine or the border monitoring system. Regarding the first one, lack of clarity of what is defence, security, and development can lead to armed forces that are not fit for the country security needs. That is, security and defence projects are not thought in terms of force design but rather in terms of economic benefits and other potential externalities. As for the second form, the military is currently deployed in support to national development missions, e.g. distributing water in draught-affected areas (Operação Carro Pipa); reducing fires in the Amazon Rainforest (Operação Verde Brasil); support to health policy in the fight against COVID-19; and offering logistic and military assistance to foster the migration influx from Venezuela (Operação Acolhida); or getting involved in issues of foreign policy such as Brazil’s activities in the Antarctica continent or policies towards the South Atlantic region.

As we have argued previously, the evolution of the security-development nexus must consider the dynamics of military professionalisation, capacities of the state (or state-building processes), and the threat environment. That said, several countries have enlarged military roles in the post-Cold War era. However, doing that in a country with that has intertwined security and development in the form that Brazil did can set dangerous precedents. On the long term, these phenomena can contribute to blurring the lines between civilian and military capabilities, reduce incentives for investments in civilian state capacities, and militarise other public policies. Thus, further research on the domestic experiences of the security-development nexus in other countries can contribute to a clearer understanding of the dynamics of this relationship, moving beyond the traditional literature of international donors.

The articles in this special issue will address many of the issues raised in this text and will explore specific points where this security/defence-development nexus can be seen in contemporary Brazil. The discussions, despite focused on Brazil as a case study, can be explored in the context of other countries and regions in the world, particularly in the Latin America realm, where Armed Forces have been also historically involved in projects of state building.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vinicius Mariano de Carvalho

Vinicius Mariano de Carvalho is a Reader of Brazilian and Latin American Studies at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London and Vice-Dean International of the School of Social Sciences and Public Policy. He received his PhD from the University of Passau, Germany.

Raphael C. Lima

Raphael C. Lima is a PhD Candidate in War Studies at King's College London. He holds an MSc. in International Relations from the Interinstitutional Graduate Programme San Tiago Dantas (São Paulo State University, Campinas State University, and PUC-SP) and a BA in International Relations from São Paulo State University.

Notes

1. Edmunds, ‘What Are Armed Forces For?’; Edmunds and Malešič, Defence Transformation in Europe.

2. Pion-Berlin, Military Missions in Democratic Latin America; Harig, Jenne, and Ruffa, ‘Operational Experiences, Military Role Conceptions, and Their Influence on Civil-Military Relations’.

3. O’Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead, Transitions from Authoritarian Rule; Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics.

4. Brasil, ‘Estratégia Nacional de Defesa’; Brasil, ‘PND END’; Brasil, ‘Política Nacional de Defesa/Estratégia Nacional de Defesa’.

5. The term public safety refers to ‘comprising police and law enforcement measures.

judicial tools, intelligence, border and transportation security, and critical infrastructure and civil protection measures’. See: Anagnostakis, EU-US Cooperation on Internal Security, 6.

6. Alsina Junior, Ensaios de Grande Estratégia Brasileira; Lima, Silva, and Rudzit, ‘No Power Vacuum’, 2 January 2021.

7. Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’; Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus; Jensen, ‘The Security and Development Nexus in Cape Town’; Hettne, ‘Development and Security’; Spear and Williams, Security and Development in Global Politics; Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’; Brown and Grävingholt, ‘Security, Development and the Securitization of Foreign Aid’; Carbonnier, ‘Humanitarian and Development Aid in the Context of Stabilization’; Jagger, ‘Blurring the Lines?’

8. Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’, 21; Spear and Williams, Security and Development in Global Politics, 314.

9. Hettne, ‘Development and Security’, 34.

10. Hettne, ‘Development and Security’; Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’; Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’; Duffield, ‘The Liberal Way of Development and the Development – Security Impasse’.

11. Levy, ‘Case Studies’, 12; Brady and Collier, Rethinking Social Inquiry, 323; Eckstein, ‘Case Study and Theory in Political Science’, 143.

12. Brady and Collier, Rethinking Social Inquiry, 323.

13. Rouquié, The Military and the State in Latin America; Centeno, Blood and Debt; Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil; McCann, Soldiers of the Pátria; D’Araújo, Militares, democracia e desenvolvimento; Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics; Stepan, The Military in Politics; Harig and Ruffa, ‘Knocking on the Barracks’ Door’.

14. For more on the contributing to national security policy mission, see: Lima, Silva, and Rudzit, ‘No Power Vacuum’, 2 January 2021.

15. The former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, said this phrase in a seminal discourse in 2005 United Nations, ‘Kofi Annan’s Statement to the General Assembly’.

16. For a complete conceptual history of the nexus between security and development, see: Hettne (2010).

17. Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’, 379–82; Hettne, ‘Development and Security’, 36–42; Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus, 15–16.

18. Krause, ‘War, Violence, and the State’; Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’, 381.

19. Hettne, ‘Development and Security’, 41.

20. Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’, 381–82.

21. Krause, 382.

22. Ibid.

23. Hettne, ‘Development and Security’, 44–45; Duffield, ‘The Liberal Way of Development and the Development – Security Impasse’, 63–64; Buzan and Hansen, The Evolution of International Security Studies, 204; Rothschild, ‘What Is Security?’ 66–67.

24. Buzan and Hansen, The Evolution of International Security Studies; Reveron and Mahoney-Norris, Human and National Security; United Nations, ‘Human Development Report 1994’.

25. Farrell, Terry, and Frans, A Transformation Gap?; Sloan, Military Transformation and Modern Warfare; Edmunds and Malešič, Defence Transformation in Europe.

26. Bellamy and Williams, ‘Trends in Peacekeeping Operations, 1947–2013’.

27. Kagan, Finding the Target, 166–68; Reveron, Exporting Security, 32.

28. Edmunds, ‘What Are Armed Forces For?’; Jenne and Martínez, ‘Domestic Military Missions in Latin America’; Pion-Berlin, Military Missions in Democratic Latin America.

29. Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’, 383.

30. Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus, 5.

31. Ball, ‘Reforming Security Sector Governance’; Bellamy, ‘Security Sector Reform’; DCAF – Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance, Sourcebook on Security Sector Reform: Collection of Papers; Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus; Krause, ‘Critical Perspectives on Human Security’; Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’.

32. Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus, 15–16.

33. Brown and Grävingholt, ‘Security, Development and the Securitization of Foreign Aid’; Carbonnier, ‘Humanitarian and Development Aid in the Context of Stabilization’; Jagger, ‘Blurring the Lines?’

34. Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’; Tschirgi, Lund, and Mancini, Security and Development; Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus, 18.

35. Chandler, ‘The Security – Development Nexus and the Rise of “Anti-Foreign Policy”’.

36. Hettne, ‘Development and Security’; Krause, ‘Violence, Insecurity, and Crime in Development Thought’; Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’; Spear and Williams, Security and Development in Global Politics; Duffield, ‘The Liberal Way of Development and the Development – Security Impasse’; Jesperson, Rethinking the Security-Development Nexus; Tschirgi, Lund, and Mancini, ‘The Security – Develop- Ment Nexus’.

37. Jensen, ‘The Security and Development Nexus in Cape Town’; Nilsson, ‘Building Peace Amidst Violence’.

38. Stern and Öjendal, ‘Mapping the Security – Development Nexus’, 17.

39. These studies were named security studies on the third world or on developing states. Most studies came out in the early 1980s and 1990s.

40. Ayoob, The Third World Security Predicment; Krause, ‘Insecurity and State Formation in the Global Military Order’; Wendt and Barnett, ‘Dependent State Formation and Third World Militarization’; Azar and Moon, ‘Legitimacy, Integration, and Policy Capacity: The “Software” Side of Third World National Security’.

41. Ayoob, The Third World Security Predicment, 130.

42. Krause, ‘Insecurity and State Formation in the Global Military Order’, 329–30.

43. Azar and Moon, ‘Legitimacy, Integration, and Policy Capacity: The “Software” Side of Third World National Security’, 78–79.

44. Williams, ‘The Crisis of Governance’, 10.

45. Centeno and Ferraro, ‘Republics of the Possible: State Building in Latin America and Spain’, 6–13.

46. Pereira (2016) sees the term as a rather disputed one. The author discusses how views of the Brazilian state as patrimonial shaped Brazil’s academics and political debate. According to him, this view evolved from Max Weber’s and Raymondo Faoro’s work and became a pejorative term to refer to the capacity of the state and became a rather contradictory term in the scholarship. According to him, these discussions obscure two points of the historical evolution in Brazil: (1) the development of a rational-legal state and (2) the development of capitalism.

47. Pereira, ‘Is the Brazilian State “Patrimonial”?’

48. Lima, Worlding Brazil; McCann, ‘Origins of the “New Professionalism” of the Brazilian Military’, 1979; Rouquié, The Military and the State in Latin America; Sigmund, ‘Approaches to the Study of the Military in Latin America’; Stepan, The Military in Politics.

49. Kacowicz and Mares, ‘Security Studies and Security in Latin America’; Ioris and Ioris, ‘Assessing Development and the Idea of Development in the 1950s in Brazil’; Bielschowsky, Pensamento econômico brasileiro, 1995; Pion-Berlin, ‘Latin American National Security Doctrines’; Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics; Lima, Worlding Brazil; Vigevani and Ramanzini Júnior, ‘Brazilian Thought and Regional Integration’; Garcia, ‘O Pensamento Dos Militares Em Política Internacional (1961–1989)’.

50. McCann, ‘Origins of the “New Professionalism” of the Brazilian Military’, 1979; Stepan, ‘The New Professionalism of Internal Warfare and Military Role Expansion’.

51. Wendt and Barnett, ‘Dependent State Formation and Third World Militarization’; Nunn, Yesterday’s Soldiers.

52. Castro, ‘The Army as a Modernising Actor in Brazil’; Rouquié, The Military and the State in Latin America, 53.

53. Mann, ‘The Autonomous Power of the State’; Mann, ‘Infrastructural Power Revisited’; Centeno, ‘El Estado En América Latina’; Centeno and Ferraro, State and Nation Making in Latin America and Spain.

54. Similar to this political view, there was also a strand of studies that reinforced the positive role the military could have in development of nations Bienen, The Military and Modernization; Johnson, The Military and Society in Latin America. They were, however, affected by the several military coups in Latin America in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. For more on the evolution of these studies, see: Sigmund, ‘Approaches to the Study of the Military in Latin America’.

55. De Carvalho and Ferraz, ‘Brazil at War: An Unexpected, but Necessary, Ally’.

56. Despite the efforts to create a professional outward-focused army, veterans from WWII were quickly demobilised and inward focus professionalism was more prevalent over the 20th century.

57. Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas, ‘Attention Deficits’.

58. Harig, ‘Militarisation by Popular Demand?’; Harig; Flores-Macías and Zarkin, ‘The Militarization of Law Enforcement’; Diamint, ‘A New Militarism in Latin America’; Passos, ‘Fighting Crime and Maintaining Order’.

59. Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas, ‘Latin America’s Growing Security Gap’; Pion-Berlin, ‘Neither Military Nor Police’.

60. Lima, Silva, and Rudzit, ‘No Power Vacuum’, 2 January 2021.

61. Brazil had three Republican periods: (1) the First Republic, from 1889 to 1930; (2) the Second Republic or the Liberal Democratic era, from 1945 to 1964; (3) the New Republic, from 1985 onwards.

62. The Brazilian imperial period had several rebellions. See: Dantas, ‘Popular Revolts in the Empire of Brazil’; Dantas, ‘Of Rebellions and Seditions: Popular Protest, Citizenship and State Building in 19th Century Brazil’.

63. Lima, ‘Legislating Security’, 279–270.

64. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 61.

65. A military man who led the positivist movement in Brazil and played a major role in the spread of republican views in society.

66. McCann, ‘Origins of the “New Professionalism” of the Brazilian Military’, 1979, 508–9.

67. Castro, ‘The Army as a Modernising Actor in Brazil’, 58–59.

68. Castro, ‘The Army as a Modernising Actor in Brazil’.

69. McCann, ‘Origins of the “New Professionalism” of the Brazilian Military’, 1979, 508–9; Pedraja, Wars of Latin America, 1899–1941, 51–61.

70. These officers supported internal revolts in the school and were key to the Vaccination Revolt, in 1904 Rio de Janeiro. Hence, closing the school was a means to stop their political engagement Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil; Castro, ‘The Army as a Modernising Actor in Brazil’.

71. Castro, ‘The Army as a Modernising Actor in Brazil’, 68–69.

72. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 60.

73. This process is referred to as the indigenous mission since the officers returned from Germany would teach their ideas to a new generation of officers.

74. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 60–64; Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 27–28.

75. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 60.

76. Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 29.

77. Nunn, ‘Foreign Influences on the South American Military: Professionalization and Politicization’, 16.

78. For the sake of the analysis, we considered only the Army political interventions. According to Carvalho (2005, 52), the Navy interventions were less politically significant than those from the Army. The author argues that the Navy’s organisational characteristics were responsible for this difference. That is, the Navy had an aristocratic recruitment process and a professional training that made it less susceptible to political interference. As for the Air Force, it was only created in 1941 and thus did not have a similar level of institutionalisation or organisational cohesion as did the other two services.

79. Stepan (1971, 19–20) argues that the military is not immune to social, regional, and local political influences and should not be considered a unitary organisation. Similarly, Carvalho (2005, 40–43) develops three categories of the Brazilian military ideology of intervention in politics. According to him, there was (1) the citizen-soldier or the ideal of a Republican reformist intervention; (2) the professional soldier or the ideal of non-intervention in politics; (3) the corporative soldier or the ideal of moderating interventions. The corporative soldier view, later led by General Goés Monteiro, was the hegemonical one from the 1930s to 1964.

80. McCann, ‘Origins of the “New Professionalism” of the Brazilian Military’, 1979; Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 40–43; Stepan, The Military in Politics, 19–20.

81. D’Araújo, Militares, democracia e desenvolvimento, 54–55.

82. Lima, ‘Legislating Security’, 269–71; D’Araújo, Militares, democracia e desenvolvimento, 55–56; Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 103.

83. This view was present in his infamous book, A Revolução de 1930 e a finalidade política do Exército. In the book, he argues that there should not be politics within the Army but a politics of the Army, one that should encompass all levels of the national life Góes Monteiro, A Revolução de 30 [i.e. treinta].

84. Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 108.

85. Between 1945 and 1964, there were distinct factions within the military. A branch of nationalist military officers did not necessarily identify with the right-wing conservative movement led by Goés Monteiro. Nonetheless, after the 1964 coup, a purge and effort to homogenise the military eliminated alternative views on the role of the military in political life. For more, see Carvalho (2005), Stepan (1971), and McCann (1979).

86. Lima, ‘Legislating Security’, 270.

87. Carvalho, Forças armadas e política no Brasil, 102.

88. D’Araújo, Militares, democracia e desenvolvimento, 56.

89. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 67; Lima, ‘Legislating Security’, 268.

90. According to Laura Lima (2015, 71), ‘even though national security had only been in public use since 1934, within a year there were no doubts about its political meaning: authoritarianism, censorship, surveillance and the submission of civilians to military principles of organisation and order’.

91. Lima, ‘Legislating Security’, 274–75.

92. Bielschowsky, Pensamento econômico brasileiro, 1995; Fonsenca, ‘Desenvolvimentismo: A Construção Do Conceito’; Bastos, ‘A Economia Política Do Novo-Desenvolvimentismo e Do Social Desenvolvimentismo’.

93. Celso Furtado was a veteran of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, serving in the campaign in Italy as Lieutenant; and Nelson Werneck Sodré was a career officer in the Brazilian Army from 1924 to 1961.

94. The school of thought influenced by the ideas of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), proposed by Raúl Prebisch. The author highlighted the growing gap between the economic structures of developed and developing nations.

95. Bielschowsky, Pensamento econômico brasileiro, 1995, 7.

96. For more, see: Bresser-Pereira, The Political Construction of Brazil; Bielschowsky, Pensamento econômico brasileiro, 1995; Bastos, ‘A Economia Política Do Novo-Desenvolvimentismo e Do Social Desenvolvimentismo’.

97. Fiori, ‘O Nó Cego Do Desenvolvimentismo Brasileiro’, 126–27; Bresser-Pereira, The Political Construction of Brazil, 118–19; Bielschowsky, Pensamento econômico brasileiro, 1995; Fonsenca, ‘Desenvolvimentismo: A Construção Do Conceito’.

98. During the period, there was only one democratically elected government was led by a military officer. Eurico Gaspar Dutra, president from 1945 to 1950, Vargas’ former Minister of War, was elected with support of your former political ally. Between 1950 and 1964, all governments were led by civilians.

99. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

100. Instituto Tecnológico da Aeronáutica.

101. Instituto Militar de Engenharia.

102. Forjaz, ‘Cientistas e militares no desenvolvimento do CNPq (1950–1985)’; D’Araújo, Militares, democracia e desenvolvimento; Rocha, ‘Militares e Política no Brasil’.

103. Lima, Worlding Brazil, 78–79.

104. Lima, 79–82.

105. Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics; Oliveira, Democracia e defesa nacional; Fernandes, ‘A reformulação da Doutrina de Segurança Nacional pela Escola Superior de Guerra no Brasil’; Pion-Berlin, ‘Latin American National Security Doctrines’.

106. Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics, 25.

107. Stepan, 25–26.

108. Barros, ‘O pensamento geopolítico de Travassos, Golbery e Meira Mattos para a Amazônia’; Buscovich, ‘Pensamento Geopolítico Brasileiro’; Miyamoto, ‘Brasil, Geopolítica e o Sistema Mundial’.

109. A few of the key military geopolitical thinkers in Brazil were Marshall Mario Travassos, General Golbery do Couto e Silva, General Carlos de Meira Mattos.

110. Rocha, ‘Militares e Política no Brasil’, 32–35.

111. Forjaz, ‘As origens da Embraer’.

112. Lima, Worlding Brazil.

113. Lima, Silva, and Rudzit, ‘No Power Vacuum’, 2 January 2021, 90.

114. Brasil, ‘Estratégia Nacional de Defesa’; Brasil, ‘PND END’.

115. Brasil, ‘Política Nacional de Defesa/Estratégia Nacional de Defesa’; Brasil, ‘Minuta da Política Nacional de Defesa Estratégia Nacional de Defesa’.

116. Lima, Silva, and Rudzit, ‘No Power Vacuum’, 2 January 2021, 99.