Abstract

Every day thousands of family photographs get abandoned in second hand bookshops, at flea markets, and internet auctions, losing their past and having their stories erased. Conversely, the same images get found, reappropriated, and assigned with new meanings. It is this process of giving the found photograph a new lease of life that I explore in this article. As I argue here, photographs continue to act as potent narrative tools even if we no longer have access to their subjects or producers. Not only do I show how anonymous photographs can be read and interpreted but also how they function as material objects that are collected, loved, treasured, and inevitably integrated into the lives of their new adopted families. I show, in particular, how both the content and the materiality of photographs makes them carriers of family history and private memory, as well as intersecting with other categories such as class and identity.

In my home there was just one family album. It began with a colour studio photograph from my christening. My proud mother is holding me in her arms, wrapped in a white baby shawl. Standing on her left is my father, gently touching my sister’s shoulder with the tips of his fingers. They are all dressed in their Sunday best. My mother, in a cream-coloured dress, is wearing her gold engagement ring. To this day she only puts it on very special occasions. My father, dressed in a grey summer suit and a striped tie, sports Wałęsa-style sideburns, popular amongst Polish men at the time. But it is my sister, then nearly four years old, who is the star of the picture, dressed in a pair of elegant light blue dungarees, white blouse and a trinket necklace. It is the summer of 1981, several months before martial law is declared in Poland, and everyone looks proud and happy. This is the first photograph of the whole family together.

I always think of this image when I look through the piles of vernacular photographs at flea markets. I think of the stories behind it. I think of my parents’ working class lives that remain invisible to strangers, not only because their elegant attire blurs class affiliations and because formal photography, more generally, is about enhancing reality, but also because the context in which this image was taken and the lives of those in it are known to a narrow group of family members. What remains invisible to a random spectator is the fact that my mother’s engagement ring was given to her only after the wedding, replacing a cheaper temporary one with which my father had proposed. My sister’s dungarees are hand-me-downs like most of the clothes we wore throughout our childhoods. My father’s grey suit, the dated flared trousers in particular, will serve him for the decade to come, constituting a source of continual embarrassment to us children. These stories of financial hardship, early mornings, night shifts, and strong work ethic, while deeply hidden from the gaze of the accidental onlooker, are intrinsic to each and every single photograph in our family album. Inevitably, the narratives behind this image will disappear once those in it are gone. What will remain is the materiality of the picture, its creased corners, stains on the back, and fold marks, as well as the content—the photographic conventions, the sartorial trends of the time, and the rites of passage associated with kin. This is the case with all family photographs.

Every day thousands of vernacular images such as this are abandoned in second hand bookshops, at flea markets, and internet auctions, losing their past and having their stories erased. Conversely, the same images get found, reappropriated, and assigned with new meanings. It is this process of giving the found photograph a new lease of life that I explore in this article, interweaving personal narrative with a scholarly exploration of materiality. As I argue below, photographs continue to act as potent narrative tools even if we no longer have access to their subjects or producers. Not only do I show how anonymous photographs can be read and interpreted but also how they function as material objects that are collected, loved, treasured, and inevitably integrated into the lives of their adopted families.

My research builds on a large body of scholarship which explores the affective dimension of possessions, and sees them as crucial in defining and maintaining our identities (Russell W. Belk Citation1988; Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton Citation1981; Helga Dittmar Citation1992; Rachel Hurdley Citation2006; Melanie Wallendorf and Eric J. Arnould Citation1988). As I demonstrate below, personal belongings go beyond mere economic value. Scholars have shown that we bond with objects the same way we bond with people, and like with people, we also share a history with our belongings (see Susan S. Kleine and Stacey M. Baker Citation2004; Susan E. Schulz, Robert E. Kleine, III, and Jerome B. Kernan Citation1989). As their biographies intersect with our own biographies, things help us narrate our life stories (Russell W. Belk Citation1990; Susan Schultz Kleine, Robert E. Kleine, III and Chris T. Allen Citation1995). Objects also contribute to the creation of distinct home cultures, constituting evocative tokens of the past and bringing comfort to their owners (Daniel Miller Citation2008; Kate Pahl Citation2012).

My approach is, of course, qualitative rather than quantitative and by no means do I argue that practices discussed in this paper hold true for all found photographs. In fact, there is a myriad of ways in which such images are managed at both private and collective levels, being used to decorate people’s homes, exchanged as gifts, utilized in public commemoration, museum work, and art practices. What interests me here is how objects that are traditionally of no interest to scholars can be incorporated into academic enquiry and how putting oneself in the narrative, as I am in this paper, enables the scholar to present a more complete version of the story she is writing. Whilst embracing a first-person narrative, I am hoping to show how the intellectual pursuit can be enriched by evidence that is often seen as unreliable and compromising (i.e., the author’s personal experience). I propose that moving away from the dispassionate—and largely invisible—author and disclosing one’s own affective attachment to the subject, can significantly enhance the way we examine material culture. Such approach is particularly apposite to the study of family photographs.

There is no denying that images discussed here are unlikely subjects of scholarly research. They are cast-offs. Their biography has been disrupted, their trajectory left undocumented. Their survival has been fortuitous, their preservation—incidental. They have never undergone the process of institutionalization, unlike some material that is normally of interest to historians (primarily because of its role as the debris of war and genocide). Such material is often sanitized, catalogued, captioned, and turned into museum artefacts destined for public consumption. Our photographs are, in contrast, expendable to history.

The term “found/orphan photograph” encapsulates many of the meanings above. Derived from film studies, archive preservation in particular, “orphan film” signifies “neglected, lost, damaged, hidden, excised, rare, unique, odd, experimental, ephemeral, and utilitarian productions” (Dan Streible Citation2009, x). In art practices, “found footage” describes “film material acquired literally ‘by chance’; material found either in an attic or somewhere in the street, in a garbage can or at a flea market” as well as forgotten sources that are discovered in museum archives (Japp Guldemond Citation2012). More generally, “an orphan is now considered any film abandoned by its owner or creator,” including footage that has been left to decay and disintegrate (Emily Cohen Citation2004, 722). By the same token, the main characteristics of “orphan photographs” is that “we no longer have access to their owners or producers, the subjects featured in them, or the families of those who witnessed or might authenticate their circumstances” (Tina Campt Citation2012, 87).

While the term “orphan film” is rapidly gaining currency, mostly due to the growing “orphanista movement” initiated by film preservationists, the idea of and cultural practices associated with “found/orphan photography” remain largely under-researched. In fact, it is primarily private collectors and found photography enthusiasts who continue to stimulate interest in this phenomenon. A documentary film by Lorca Shepperd and Cabot Philbrick, Other People’s Pictures (Citation2004), sheds light on the collectors’ motivations and shows an intricate link between collecting anonymous photos and the hobbyists’ personal family stories. Other bottom-up projects, such as the Flickr’s Museum of Found Photographs, which boasts an archive of more than 83,000 images, attest to the collective fascination with orphan pictures. This comes as no surprise since, as Susan Sontag put it, “A photograph is both a pseudo-presence and a token of absence. Like a fire in a room, photographs—especially those of people, of distant landscapes and faraway cities, of the vanished past—are incitements to reverie” (Citation1977, 14). Orphan images, in particular, become conduits of memory, whereby their mysterious pasts inspire storytelling and, inevitably, a radical reinterpretation.

The rebelling orphan

We seldom throw away photographs, even if their sentimental value has expired. Instead, we stash them in remote corners of the attic, hide them in rarely opened drawers or bury in boxes shoved onto the highest shelves of the wardrobe. Carol Mavor argues that the photograph is like a body; we cannot discard or destroy it: “to tear or to cut the photograph is a violent, frighteningly passionate, hysterical action, which leaves behind indexical wounds, irreparable scars” (Citation1997, 119). According to Adam Drazin and David Frohlich, “photographs demand of us that they be treated right”—treated with care and attention, like you treat a human being (Citation2007, 51). Unlike utilitarian objects, images have a higher moral standing; they are objects of affect that are imbued with meaning and inscribed with memories. When sorting through belongings of a deceased family member, we handle photographs with special care, while disposing of clothes, kitchen utensils, furniture, bed sheets, and decorative items. Even if such images have no sentimental value to us, it is hard to let go of them. After all, they are often seen as the sacrosanct territory of someone else’s personal history. Inheriting other people’s photographs instils a sense of responsibility in us. We want to offer these once-treasured possessions a chance at a second life.

This is typically how unwanted pictures end up at flea markets and second-hand bookshops. We see these repositories of used objects as elite storage spaces that offer a temporary refuge to orphaned images. Yet, in the process, the photographs are deprived of their status as the object of affection. Forced into an unsympathetic archive which is governed by the gaze of strangers, orphan works have often been read as being subjected to patriarchal agency and compelled to compete for the attention of potential owners with other discarded objects. Writing about abandoned films, Emily Cohen shows that for many in the film community the “archive has been transformed into an orphanage of innocent dying children betrayed by their patriarch: A landscape threatened by its own degradable nature […]” (Cohen Citation2004, 727). Tina Campt argues that such an interpretation of the archive strengthens the perception of orphan works as passive and helpless objects waiting to be saved from the dustbin of culture. She shows that found photographs are more complex than this:

What is unsettling about this narrative is what it leaves out—namely, the potentially disruptive capacities of the unruly, orphaned child. A propensity for tantrums, rebellion, and refusal to play the ascribed docile role of adopted and redeemed model child. This narrative leaves out an inclination, will or desire for fugitivity, that is, the orphan’s capacity to reveal to us—the memory, history, or heritage we think we know—but that which we neither want to see nor necessarily recognize when it is shown to us. It is a history and a heritage that is neither directly accessible nor apprehendable through its showing, screening, or display. (Campt Citation2012, 90)

Campt argues thus that such objects have agency of their own. This agency or “fugitivity” defies the passivity we often ascribe to found objects in general and images in particular, and shows that things, like humans, have their own distinct social lives. As I argue below, the orphan’s fugitivity is frequently written on its body. The materiality of the photograph provides us with helpful clues about the orphan’s happy past, encouraging us to move beyond the content-based approach and discover the ways in which the docile child rebels against the traditional roles that are forced upon it.

The materiality of friendship

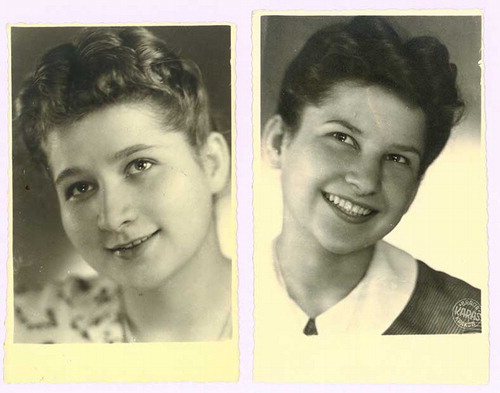

My interest in found photographs began with these two images (). Nearly six years ago, I visited a flea market in Kraków’s old town in the hope of finding photographs for a new project. At that stage I did not know what the project would be about. Similarly, having no prior experience of collecting old photographs, I was not exactly sure what to look for. Yet, my fascination with anonymous vernacular images was already very strong at that time. I was interested in formal photographs that, on the surface, revealed nothing about themselves and the subjects featured in them, and therefore posed a greater challenge to those who attempted to interpret them. Having always been wary of Julia Hirsch’s claim that “Formal photographs stand against emotion” and that “They permit us to look at the family, not into it […],” I constantly asked myself about the possibility of an alternative reading that would allow us to gain some sort of access into the subjects’ lives (Citation1981, 97). In truth, I never believed that the formal convention could deprive the photograph of emotion. I continued to wonder about other ways of looking at such images that would go beyond the traditional content-based approach.

As I was chatting to the salesman about his rapidly expanding collection of anonymous black and white images, I casually leafed through a cheap plastic photo album in which he kept the pictures. Placed one next to another, the two images immediately attracted my attention. I became fascinated with how they complemented each other, being at once so similar and so different. To this day I think of them as one, almost indistinguishable in what they tell me about themselves, at both material and content levels. At first glance, not much can be said about the two images or the subjects featured in them. Initially, I was not even entirely sure if the headshots were of the same person or of two different people. It might have been that the genetic traits inscribed into the smiles of the subjects, the way they tilted their heads and looked slightly upwards or how they wore their hair, left me blind to the apparent differences in their facial features. When I look at these images today I see nothing but difference, intrinsic to the shape of face, eyes, lips, teeth, and eyebrows. At the time I saw them as one. Yet, I could not help but think about the undefined link between these two pictures, a connection that went beyond the mere physical characteristics of the subjects.

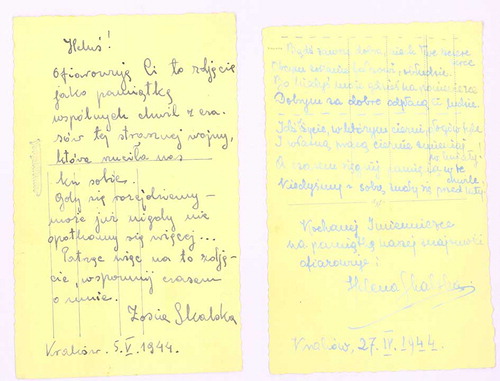

It was only when I looked at the affectionate inscriptions on the back of the images that the link became clear (). The two photographs came from the same home and their subjects, Helena and Zosia Skalska, were sisters. But it was not the family home of the Skalski sisters that the images were banished from. In fact, there was a third actor hidden behind the scenes. She was absent from both photographs, at least as far as the content was concerned, but her presence was all-pervading. Her name was Helena, like one of the subjects, and she was a close friend of the Skalskis. The messages on the back were addressed to her. The wider context in which the exchange of images took place will always remain unclear but it can be presupposed that the pictures were given to her by the two sisters as a memento of their brief war-time friendship, one that was possibly coming to an end due to circumstances that were beyond the control of those involved. The two photos were given to Helena in the space of one week and the dates on the back of each photograph read 27 April and 5 May 1944, respectively.

The first message, written by Helena Skalska, is a short rhymed poem in which she expresses the hope that the addressee will always follow the path of righteousness, bravely overcoming obstacles in front of her. Here life is envisioned as a path full of difficulties (thorns and spines) that can only bloom into flowers by hard work. There is also a reference to a distant point in time when the recipient will look back at the image and remember the friendship the two once shared. Just like the picture follows certain visual rules, also the poem represents a specific literary convention. The genre, which could be provisionally described as a “keepsake poem” is a type of coming-of-age poem that was commonly used in Poland until as late as the 1990s. Written on the back of images or in personal memory books, called pamiętniki, poems like this were meant to act as a reminder of the past when their authors and addressees reached adulthood and parted ways. Such poetry was the domain of teenagers, young girls in particular, who looked forward to maturity, whilst being acutely aware that friendships inevitably come to an end. This is also the idea behind the inscription by Zosia Skalska, even though it is more personal in tone:

Heluś, may this photo serve as a memento of our shared time during this awful war which brought us together. When we part our ways, we might not see each other again… Remember me sometimes when you look at this picture. Zosia Skalska.Footnote1

The writing on the back attests to an important social role of photographs as objects of exchange. Thus, it is possible that there were two other photographs, both of Helena, the addressee of the messages, included in this exchange. To me it is this gesture of gift-giving and, even more so, of gift-keeping, implicit to the two photographs, that makes these found images escape the constraints of orphanage. As Elizabeth Edwards put it, “photographs express a desire for memory and the act of keeping a photograph is, like other souvenirs, an act of faith in the future” (Citation2009, 332). Yet in stark contrast to orphan photos discussed by Tina Campt in her compelling book on the images of African diaspora in Europe, there is nothing in the pictures of the two sisters that would defy their status of orphans. In fact, in the case of Campt’s images, the fugitivity is neatly embedded in their content, it emerges

in scenes of intimate gatherings on the couch or at the pub—scenes that signify and stage friendship through the physical intimacy they display through arms clasped on shoulders, heads resting on shoulders, heads touching other heads, friends huddling together shoulder to shoulder. (Campt Citation2012, 95)

The journey of the two images from Helena’s home to the flea market in Kraków’s old town is nonetheless marked by the owner’s death. It is this death that made the images stray from the familial path that was originally destined for them. After Helena’s death and the discarding of these objects, the writing on the back becomes the only written record which helps us read these photographs. And yet, its fragmented nature, the gaps and the omissions, inherent to the dedication, create a situation of a “suspended conversation,” to use Martha Langford’s phrase. After all, family images, albums in particular, act as aide–mémoire, which trigger storytelling. Once deprived of their owners and rightful storytellers, the ritual of oral–photographic performance gets suspended, memories dispersed and forgotten. This is particularly visible in the museum setting wherein family albums often become divested of their foundational narratives (Martha Langford Citation2001, 5).

I want to take Langford’s argument a step further. My argument here is that the writing on the back is a way of continuing that conversation in the absence of the three women (as well as continuing the acts of storytelling that this photograph had once inspired). After all, it is Helena’s death that brought the images to my home, supplementing my private collection of similar photographs that had been given to me in my teens by close female friends with whom I subsequently lost touch. Thus, although Helena’s death triggered the expulsion of the two objects from her home, I cannot help but see her passing as a chance for “diversion,” to use Arjun Appadurai’s term. Appadurai sees diversion as a practice of drifting away from the habitual settings in which objects circulate. Diversion may encompass a variety of contexts but it invariably enriches the objects that take part in it:

The enhancement of value through the diversion of commodities from their customary circuits underlies the plunder of enemy valuables in warfare, the purchase and display of “primitive” utilitarian objects, the framing of “found” objects, the making of collections of any sort. In all these examples, diversions of things combine the aesthetic impulse, the entrepreneurial link, and the touch of the morally shocking. (Arjun Appadurai Citation1986, 28)

This is what happened to Helena’s photographs. Over the years they returned to the old path of domesticity, finding refuge in my home and becoming my faithful companions. The two images have been with me for more than five years now. They have been with me as I moved from one country to another, leaving behind friends, exchanging digital photos of the happy times we had had together, and making new friendships. I carried Helena’s pictures in a paper envelope that the photo seller gave to me on that summer day in Kraków. Once in a while, I would take the images out of the envelope to reread the writing on the back and to look at the subjects’ faces. Over time, I have developed a strong attachment to these objects and my collecting has become a special type of “passionate consuming,” to use Russell W. Belk’s phrase (Citation1995, 66). Quickly enough, the pictures became home to me, signifying both the homeland I left behind in my early twenties, and providing permanence in my vagrant existence of a junior academic.

Over the past few years, I have given a lot of thought to these two images. I have been thinking about the urban (upper)-middle-class lives of the Skalski sisters that enabled them to engage in an exchange of gifts at a time of scarcity and depleted resources. I have been wondering about the daily lives of the two photographers who worked as normal despite the war raging around them. Finally, I have been thinking of Kraków’s Jewish ghetto which had been liquidated only a year before the photographs were exchanged. Aware of this wider context, I sometimes looked for signs of carnage and destruction. Yet, there is nothing about the photographs, be it in their content or on their bodies, that speaks of the hardships of war. The subjects are smiling, projecting an image of safety and happiness. The corners of the images are not creased, the ink is not smudged, and the writing on the back is well preserved. These are happy images that had survived the war unscathed. Helena had survived the war with them. It was her who enabled the images to maintain their role as tokens of memory and objects of affection. Also I chose to assign that role to them. Today, the two images remind me of the places I have loved and lived in for the past few years, the places I will always feel nostalgic for; the wooden mantelpieces and Ikea bookcases on which I kept these photographs, and brown Amazon boxes in which I moved them from country to country. To me these two images are exemplary rebels. They escape the constraints of the orphanage. Their healthy bodies show no sign of neglect or decay. Their mobility and “diversions” testify to an extraordinary ability to adapt. As I think of the “social life” of these objects, I also reflect on my own personal and professional trajectory, which has been defined by a constant intertwining of migration, on one hand, and a strong sense of rootedness on the other. The way in which I read and adopt these found photographs has been and always will be inextricably linked to my own biography.

The materiality of love

My parents’ wedding photograph is one of my favourite images in our family album. When I first went to study abroad, I took this photograph with me as a reminder of home. Following a move to another country after my PhD, I had returned the picture to my parents and have not revisited it ever since. Yet, having thought about and looked at it so often during my time as a doctoral student, I was convinced I remembered it perfectly. It was only when I began to write this article and tried to recreate the photo in my mind that I realised how incomplete my memory of that wedding picture was. I was not able to reconstruct the poses, the glances, or the touches. Were they both seated or only one of them? Were they leaning familiarly towards each other or standing apart? Were they looking into each other’s eyes or facing the camera? I knew the possible variations that the convention of a wedding photo allowed but could not picture the specific details.

What I remembered was my mother’s wedding dress. This is not surprising since she has kept it to this day and I have tried it on many times, both as a child and as an adult woman. I also remembered her white chunky-heeled shoes typical of the late 1960s and early 1970s’ fashion. The shoes are, in fact, the first thing I think of when I try to evoke the image in my mind. I had always doubted they were made of leather, even though, as I found out later, leather had not been a rare material in socialist economies and it had been commonly used by the light industry in footwear production. Even if this had not been the case, the policy of consumerism, funded by Western credits and aimed at appeasing the society that was growing increasingly disenchanted with the regime, would have allowed for the citizens of 1970s Poland to have easier access to such products. What is more, given a relative equality of wages between the various social classes, this consumerist privilege would not have been restricted to the middle class.

Nonetheless, my reading of this photograph replicated contemporary perceptions of class. I imagined that a pair of white leather shoes would still have been considered unnecessary indulgence. Having always struggled for money, my parents could do with very little, in particular where clothes, furniture, and other material possessions were concerned. To some extent, my reading of this image reflected what had been so aptly put by bell hooks:

The poor are expected to live with less and are socialized to accept less (badly made clothing, products, food, etc.), whereas the well-off are socialized to believe it is both a right and a necessity for us to have more, to have exactly what we want when we want it. (bell hooks Citation2000, 48)

I called my mother to ask about the shoes. She remembered them perfectly, the shape of the heel, the decorative pattern on the toe box, and the white strap that closed at the ankle. But she had no recollection of what they were made. This is not important, she told me, you cannot tell whether it is leather by looking at the picture anyway. This is when I realised that the wedding photograph is not about reflecting reality but about projecting it. It is not about the present but about the future, not about the contemporaries but about posterity. Her wedding gown, shoes, and accessories were meant to channel wealth, opulence, and, by association, an upper-middle-class sensibility. In that respect all wedding photographs, and to some extent formal photography in general, strive to both conceal and rewrite class affiliations, enabling the subjects to perform their desired class identity.

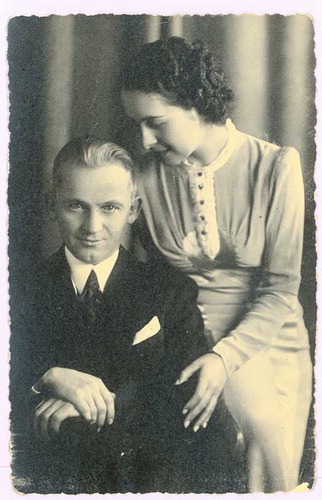

This is precisely how I read the image of newlyweds from the village of Jasienica (). While this is not a typical wedding picture, it can be presupposed that it was taken to memorialize a union between the two subjects, Asia and Jędruś. Shared with a close friend or a relative, named Władzio, on the “threshold of [their] new life together,” to cite the writing on the back, the image points to the ways in which “photographs have always been handed on, shown around and communicated to others” (Katharina Lobinger Citation2016, 4). In that sense, the cultural practices attached to this photograph do not differ that much from what we saw in the case of the Skalski sisters—also this image was a gift. It is the class background of the subjects that sets them apart. On the surface, little can be said about Asia and Jędruś. Like my parents’ wedding picture, also this photograph projects an image of upper-middle-class prosperity. The subjects wear elegant clothes, their hair is styled, and they both look well groomed. This illusion, created with the assistance of a professional photographer, is meant to project the couple’s “best social selves.” Writing about wedding photography, Charles Lewis rightly points out that

For one day, couples become wealthy nobles―they are at the very center of an opulent and grand existence, no matter how mass produced it may actually be. Couples and their families, regardless of economic status, enter the realm of the upper class. (Charles Lewis Citation1997, 173)

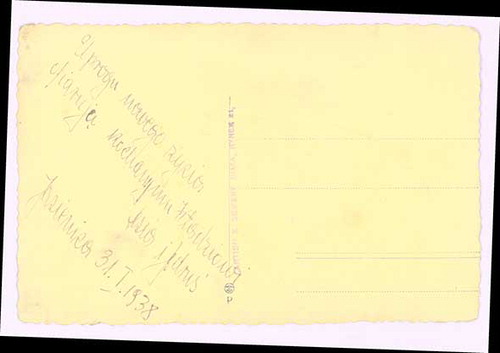

Whilst the content of the Jasienica photograph emulates the world of the wealthy, the writing on the back reveals the subjects’ actual class background, constituting a reality check for the viewer. It was indeed the message to Władzio, the recipient of the image, that initially drew me to this photograph (). The back of the picture shows that photographs have, what Geoffrey Batchen describes as, “volume, opacity, tactility, and a physical presence in the world” (Citation2001, 60). In other words, when faced with the writing on the back we are reminded that someone held the image in their hands, wrote the message and gave it to another person. This is also how we come to question what the content of the photograph tells us.

When I first saw the picture, I could not help but wonder about the use of language, more specifically the two words: kochanymu and ofiarują. I knew immediately that these could have never appeared in an image of the urban upper-middle-class elite. The former (typical for rural Polish dialects) is a dialectical form of the standard adjective form kochanemu, the latter is an erroneous form of the verb ofiarować. But these linguistic features are not the only indicators of the subjects’ rural origins. It is reiterated in the name of the village which appears at the bottom of the hand-written message. The place, “Jasienica,” could be any of several villages in Poland, making the couple’s exact geographical location both vague and commonplace.

The discrepancy between the front and the back of the image makes this object a fascinating example of the workings of portrait photography and, particularly, its ability to (temporarily) rewrite class affiliations. The front—the content—tells only one part of the story, it conveys the longing for financial and social mobility, while the back—the writing—reminds us of the couple’s inability to transgress these rigid boundaries. As such, this photograph acts not only as an object solemnizing and immortalizing the rite, an important function of wedding photographs pinpointed by Pierre Bourdieu, but also as an expression of social aspirations and class yearning (Citation1990, 20). Interestingly, these are constructed with the assistance of the photographer whose livelihood depends on the ability to depict the image of a loving, prosperous, and happy couple.

The image is also representative of wider cultural practices assigned to photography in the village community, namely its role as an integral part of “circuit of gifts and counter-gifts which the wedding has set in motion” (Bourdieu Citation1990, 20). Indeed, like in many other cultures, wedding pictures were presented to guests as a visual affirmation of the publicly-proclaimed martial bond and a way of thanking them for participating in the ceremony. The recipients were chosen carefully from the circle of closest family, including parents, godparents, and siblings. This was dictated primarily by economic concerns, after all, village weddings were large enterprises often lasting several days and attracting several hundred guests. However, this particular photograph clearly comes from the civil ceremony, as indicated by the bride’s outfit. Traditionally, civil ceremonies took place just several hours before the church wedding, and bride and groom would have had a change of clothes, moving from low-key elegance to royal-like glamour. Thus it could be presupposed that Władzio was more likely a friend, rather than a family member, who attended the civil ceremony, and was given the image as a memory of the event.

Like the photographs of the Skalskis, this picture also has a date on it. The image was given to Władzio on 31 January 1938, less than two years before the start of World War II. Thus, this photograph preceded the cycle of violence set in motion by Nazi genocidal policies and home-bred anti-Semitic sentiment. It preceded the extermination of three million Polish Jews and the subsequent ethnic homogenization of the population engineered by the newly-installed communist regime. At the same time, the material dimension of this picture, specifically the stamp of the photographic studio bearing a name of a Polish-Jewish owner, speaks to the thriving of Jewish entrepreneurship in pre-war Poland in general and the importance of Jewish photographers in developing the trade in Eastern Europe, in particular. Yet, like in the case of the two images of the Skalski sisters, there is nothing in the picture from Jasienica that would suggest the rupture brought about by the Holocaust. Like the other two images, also this one is well preserved and was, for years, a treasured token of friendship. It is only the studio stamp that remains a haunting reminder that, most likely, the picture outlived its producer.

Nonetheless, the photographer, or rather the aesthetic choices made by him, are still discernible in the image. Most notably, we can see these at the level of composition and the convention used here which are distinct from what one would normally anticipate from the wedding picture. According to Charles Lewis, wedding photographs tend to reinforce the patriarchal worldview and gender stereotyping. These are depicted through the poses, the glances and the positioning of the subjects in relation to one another. In the process, the wedding image becomes a display of female submissiveness and of male dominance whereby the women are often depicted “as a prized possession” (Lewis Citation1997, 180). At first glance, this does not seem to be the case here. On the surface, the woman’s pose assigns her a more active role. After all, she is standing taller than the seated male figure. But her embrace is a protective one, replicating the stereotypical idea of women as mothers and guardians of the hearth. The gaze of the two figures strengthens this normative display of gender roles. The woman’s eyes are fixed firmly on her partner, they are turned inwards, shying away from the spectator. It is her who is responsible for conveying a sense of intimacy between the two. The husband’s gaze, on the other hand, is directed outwards towards the photographer and towards us. As such, the two figures and their positioning towards each other and towards the spectator replicate the traditional gender binaries of private and public, emotion and reason, passive and active. In this image, the man is the one who faces and takes on the outside world, the woman is the one who supports him in his daily struggles.

This brings us to the theme of love, actual or staged, which this image is meant to exude, and to the eradication of love that might come with the death of the subjects and their families. According to Roland Barthes all family photographs become voiceless orphans that are no longer able to testify to the closeness and kinship that brought them to life:

What is it that will be done away with, along with this photograph which yellows, fades, and will some day be thrown out, if not by me—too superstitious for that—at least when I die? Not only “life” […] but also […] love. In front of the only photograph in which I find my father and mother together, this couple who I know loved each other, I realize: it is love-as-treasure which is going to disappear forever; for once I am gone, no one will any longer be able to testify to this: nothing will remain but an indifferent Nature. (Roland Barthes Citation1981, 94)

Despite Barthes’s fear that what once was will become forgotten and erased, the photograph of the couple from Jasienica tells a completely different story. It attests to the importance of the photographic convention and of the exchange of images in the process of preserving the love and affection that the two had once shared. As Annette Kuhn has argued, “family photographs have considerable cultural significance, both as repositories of memory and as occasions for performance of memory” (Citation2002, 284). This is not only true of the photographs we feel emotionally attached to but also of the images of strangers that we as collectors acquire, appropriate as our own, reinvent, and retell in sync with our own experiences and biographies. Not only do such photographs trigger the narratives of familial love, or lack thereof, but also make us think about what might be concealed from the view. These concealed narratives differ from picture to picture, and from spectator to spectator, often constituting a combination of what can be discerned from the image and its materiality, and the personal stories that each and every spectator brings into the photograph.

This is precisely the case with the image from Jasienica and the way in which I, as an individual, have narrated it, making it part of my own life story. To me this image will always be inextricably connected to the history of my own family, bringing to the surface those narratives that, for much of my adulthood, were left unarticulated. As I have been scrutinizing this photograph over the past few years, I have been frequently thinking about my working class background, and my constant straddling between the two worlds that I have inhabited: the world of my working class parents and the world of academia. I have often felt that the photograph from Jasienica, particularly the discord between what the front and the back are saying, is representative of my own biography. As my own attempts at adopting this found image show, the appropriation, domestication, and consumption of such objects speaks to a wider relationship between material culture and personhood, and more generally, to the process of constructing “home cultures” which are often invented, narrated, and sustained through things.

Conclusion

Found photographs constitute powerful objects of “passionate consuming.” As we acquire and adopt these discarded and unwanted items, we learn to read the cues inscribed into the content and the materiality of the pictures, and see them as physical objects that are entangled in a web of social relations. Developing their own distinct social lives, abandoned photographs tend to migrate from their customary domestic settings, frequently turning into objects of merchandise. As they get found and reappropriated, they are once more adopted into the familial context. The collectors, photography enthusiasts, and “orphanistas” endow the images with affect and transform them into objects of tender regard, which questions the stereotypical role of “orphans” that is often enforced upon them. To me, the found photos have been important props in reflecting on the family images that I have known since childhood and that I have learnt to treasure as I get older. Reading these objects concomitantly with the family pictures enabled me to dig deeper into the history of my family, and explore my personal and professional trajectory, including the experiences of migration and class mobility. Over the years, these found photographs have accompanied me in my travels, constituting a reminder of home and homeland, and contributing to the creation of my own distinct “home culture.” The profoundly embodied and intimate ways in which I have been experiencing and thinking about these images point to an important role of found objects as conduits of memory and objects of affect. Consequently, how we deal with and speak about such anonymous photographs tells us more about our own past than about the past they are the referents of. In the end, adopting the found image becomes a projection of our own fantasies of home, family, and rootedness, which go beyond the material object in question and attest to our search for identity and personhood.

Notes on contributor

Ewa Stańczyk is Lecturer in European Studies at the University of Amsterdam. She holds a PhD in Polish Studies from the University of Manchester (2010). Her research focuses on collective memory and national identity in East/Central Europe, as well as the uses of photography in the cultural constructions of past. She is currently completing a book on children in World War II and working on a new project on found/orphan photographs after the Holocaust. Email: [email protected]

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank John Paul Newman and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Your suggestions, praise, and encouragement were very much appreciated and gratefully received. Thank you.

Notes

1. All translations from Polish are mine.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 3–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511819582

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Noonday Press, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

- Batchen, Geoffrey. 2001. Each Wild Idea. Writing, Photography, History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Belk, Russell W. 1995. Collecting in a Consumer Society. London: Routledge.

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. “Possessions and the Extended Self.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2): 139–168.10.1086/jcr.1988.15.issue-2

- Belk, Russell W. 1990. “The Role of Possessions in Constructing and Maintaining a Sense of past.” In Advances in Consumer Research. 17 vols., edited by Marvin E. Goldberg, Gerald Gorn, and Richard W. Pollay, 669–676. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Campt, Tina. 2012. Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe. Durham: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822394457

- Cohen, Emily. 2004. “The Orphanista Manifesto: Orphan Films and the Politics of Reproduction.” American Anthropologist 106 (4): 719–731.10.1525/aa.2004.106.issue-4

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi, and Eugene Rochberg-Halton. 1981. The Meaning of Things: Domestic Objects and the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139167611

- Dittmar, Helga. 1992. The Social Psychology of Material Possessions. New York: St. Martin’s.

- Drazin, Adam, and David Frohlich. 2007. “Good Intentions: Remembering through Framing Photographs in English Homes.” Ethnos 72 (1): 51–76.10.1080/00141840701219536

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2009. “Photographs as Objects of Memory.” In The Object Reader, edited by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, 331–342. London: Routledge.

- Guldemond, Japp. 2012. “Found Footage: Cinema Exposed.” In Found Footage. Cinema Exposed, edited by Marente Bloemheuvel, Giovanna Fossati, and Jaap Guldemond, 9–16. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press and EYE Film Institute Netherlands.

- Hirsch, Julia. 1981. Family Photographs: Content, Meaning, and Effect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- hooks, bell. 2000. Where We Stand: Class Matters. New York: Routledge.

- Hurdley, Rachel. 2006. “Dismantling Mantelpieces: Narrating Identities and Materializing Culture in the Home.” Sociology 40 (4): 717–717.10.1177/0038038506065157

- Kleine, Susan S., and Stacey M. Baker. 2004. “An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment.” Academy of Marketing Science Review 1: 1–26.

- Kuhn, Annette. 2002. Family Secrets. Acts of Memory and Imagination. London: Verso.

- Lewis, Charles. 1997. “Hegemony in the Ideal: Wedding Photography, Consumerism, and Patriarchy.” Women’s Studies in Communication 20 (2): 167–188.10.1080/07491409.1997.10162409

- Lobinger, Katharina. 2016. “Photographs as Things—Photographs of Things. a Texto-Material Perspective on Photo-Sharing Practices.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (4): 475–488.10.1080/1369118X.2015.1077262

- Langford, Martha. 2001. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Mavor, Carol. 1997. “Collecting Loss.” Cultural Studies 11 (1): 111–137.10.1080/09502389700490071

- Miller, Daniel. 2008. The Comfort of Things. Cambridge: Polity.

- Other People’s Pictures. 2004. Film. Directed by Lorca Shepperd and Cabot Philbrick. USA.

- Pahl, Kate. 2012. “Every Object Tells a Story. Intergenerational Stories and Objects in the Homes of Pakistani Heritage Families in South Yorkshire, UK.” Home Cultures 9 (3): 303–328.

- Schulz, Susan E., Robert E. Kleine, III, and Jerome B. Kernan. 1989. “‘These Are a Few of My Favorite Things’: Toward an Explication of Attachment as a Consumer Behaviour Construct.” In Advances in Consumer Research. 16 vols., edited by Thomas Srull, 359–366. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Schultz Kleine, Susan, Robert E. Kleine, III, and Chris T. Allen. 1995. “How is a Possession ‘Me’ or ‘Not-Me’? Characterizing Types and an Antecedent of Material Possession Attachment.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (3): 327–343.10.1086/jcr.1995.22.issue-3

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Streible, Dan. 2009. “The State of Orphan Films: Editor’s Introduction.” The Moving Image 9 (1): vi–xix.

- Wallendorf, Melanie, and Eric J. Arnould. 1988. “‘My Favorite Things’: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry into Object Attachment, Possessiveness, and Social Linkage.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (4): 531–547.10.1086/jcr.1988.14.issue-4