ABSTRACT

Postfeminist media culture celebrates female bodies as a source of identity and power and calls for women to engage in work on the physical and psychological self. This paper offers a critical analysis of marketing by Flat Tummy Co., a company that sells appetite suppressant products to women with the promise of achieving slim ideals. We collated 270 photos and 98 slogans from Flat Tummy Co.’s Instagram account. Our analysis identified three interpretive repertoires: be fit even though you’re lazy; be thin even though you binge; be empowered even though you’re weak. These repertoires set up an impossible dilemma between ideals and “reality”. Flat Tummy Co. claim to resolve this dilemma by offering products that tell women there is no need for work on the body and self. We conceptualise this rhetoric as Erasure of Labour, where socially desirable goals are ostensibly achieved without associated work. Whilst Erasure of Labour solutions are presented as freeing and simple, we argue they are a potentially harmful illusion. Our critical analysis will equip consumers and feminist activists with a means to evaluate and resist these seductive marketing messages. We conclude by encouraging researchers to look for Erasure of Labour rhetoric in other domains.

Introduction

Flat Tummy Co. (FTC) is a company that sells “nutritional” products, in the form of teas, shakes and lollipops, that are marketed to women as being able to reduce hunger and bloating. It was founded in Australia in 2013 (Make it Tasmania Citation2017) and sold to Canada’s Synergy CHC Corp for 10 USD m in 2015 (Julia Wong Citation2019). Their target market is women who are interested in beauty and are active on social media. Their marketing is specifically focussed on Instagram where they have a following of over 1.7 million users. Instagram is an online platform where companies, celebrities and the general population can interact directly, thus ostensibly merging “intimacy, access and authenticity with promotion and branding” (Anne Jerslev and Mette Mortensen Citation2016, 249). FTC exploit this channel by paying celebrities and so-called “Instagram influencers” (generally semi-professional models) to endorse their products (Wong Citation2019). Millennials (people born between 1981 and 1996) respond particularly well to personalised targeting about body image (Rieke Sara, Deborah Fowler, Hyo Chang and Natalia Velikova Citation2016). By focussing their marketing on Instagram FTC are using a tool that can be considered “the heartbeat of marketing to millennials” (Kelly Ehlers Citation2017, 1) , , , , , , .

Table 1. A summary of the premises and conclusions of each of the three repertoires.

FTC marketing has been criticised by the general public and media commentators. When the company put up a promotional billboard in Times Square, New York, suggesting that their products could suppress women’s appetites, an online petition to have it removed, on the grounds that it promoted harmful messages about weight loss, was signed by over one hundred thousand people (Tess Holliday Citation2018). A vocal critic of FTC and their approach to weight loss is Jameela Jamil, a British former model and presenter turned actress, who has taken on the role of celebrity feminist (Hannah Hamad and Anthea Taylor Citation2015). In 2018 she directed a critical spotlight toward FTC, using her Twitter account (https:twitter.com/jameelajamil) to illuminate the underlying messages directed at women. Her tweets were subsequently reported and discussed in mainstream media (e.g. Frances Ryan Citation2018). The example below exemplifies her concerns about the impact of FTC and the wider beauty industry on women’s self-worth.

The way this industry sells fear to (only) women about the inevitable effects of time and gravity, and a slowing metabolism, makes me feel sick. The corrective beauty industry is booming at an all-time high, because they have ensured our self-worth is at an all-time low. (Jameela Jamil Citation2019)

Public critiques such as this are an important channel for challenging the objectification of women and the ways in which oppressive body ideals are marketed. Our paper furthers this agenda by offering an in-depth discursive analysis of the messages FTC promotes to women regarding ideal bodies and subjectivities. To offer theoretically informed scrutiny, we situate our analysis of FTC’s promotional messages within the contemporary postfeminist, neoliberal media landscape. Our argument is that the interpretive repertoires deployed by FTC diverge from previously seen discourses which demand work on the self (Ana Elias, Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff Citation2017; Sarah Riley, Adirenne Evans and Martine Robson Citation2019) by promising the “Erasure of Labour”.

Literature review

A growing base of research evidences how advertising directed at women reflects postfeminist tropes (Rosalind Gill Citation2007; Angela McRobbie Citation2009). These issues will now be examined in more detail with attention paid to the tensions and contradictions that abound.

Femininity as a bodily property

A key element of postfeminism is the preoccupation with surveillance of the body. The body is seen both as a source of power, and as a window to the individual’s interior life (Gill Citation2007, Citation2008). According to Gill (Citation2008, 43), “empowerment is tied to possession of a slim and alluring young body, whose power is the ability to attract male attention and sometimes female envy”. In other words, value is derived from the possession of bodies or body parts that are used, consumed or sexually desired by others (Sarah Riley, Adrienne Evans, Sinikka Elliott, Carla Rice and Jeanne Marecek Citation2017).

The sexualised representation of the body is evidenced in marketing and advertising through the easily recognizable figure of the “midriff” (Gill Citation2008, Citation2009).

Gill describes images of half-naked, conventionally attractive models with their slim, toned tummies exposed to the viewer. This is invariably combined with a “Porno Chic” aesthetic (Brian McNair Citation2002) which evokes sexual arousal: arched backs, exposed cleavage and simulated orgasms. Thus, the midriff becomes an undeniable site of erotic interest and a signifier of hyper-(hetero)sexualised femininity.

The necessity for labour on the body

On the one hand, postfeminist media culture celebrates the female body as a source of identity and power, yet simultaneously constructs it as a pathological composite of problems (McRobbie Citation2009). Thus, women are called upon to focus their attention on the body and work to enhance it, manage it and solve its inherent flaws. As Gill (Citation2008) elucidates, “each part of the body must be suitably toned, conditioned, waxed, moisturized, scented and attired” until the postfeminist “ideal” body (exemplified through a slim, flat midriff) is obtained. Women’s flawed bodies are always on the brink of failing unless a continuous programme of maintenance work, or “aesthetic labour” is enacted (Elias, Gill and Scharff Citation2017; Gill Citation2009). Sometimes that work is constructed as fun. For example, Michelle Lazar (Citation2017) examines cosmetic advertising where aesthetic labour is recontextualised as playful practice. At other times, work is constructed as difficult but rewarding. For example, Sarah Riley and Adrienne Evans (Citation2018) analysed women’s blogs about exercise and identified how the achievement of a slim, toned body was said to require hard fought physical and psychological work.

Hence, we see neoliberal discourses about transformational makeovers: aspirational practices whereby body projects can be remodelled and reinvented as something better. Neoliberalism calls upon consumers to become entrepreneurs of the self (Michel Foucault Citation2008, 226), cultivating newer and better versions of themselves. In this way women are expected to conform to even narrower ideals of female attractiveness.

Neoliberal consumption as solution

In answer to this call to work, neoliberal consumerism is invariably trumpeted as the solution. By consuming products, work on the body can be enacted (Nicola Brown, Christine Campbell, Craig Owen and Atefeh Omrani Citation2020). Consumption is positioned as central to production of postfeminist identity (McRobbie Citation2009; Riley, Evans and Robson Citation2019). The making of femininity is understood as a body practice that is fundamentally consumer oriented, conveniently aligning with the “Capitalist need to sell an ever-expanding roster of commodities in a globalized economy” (Josee Johnston and Judith Taylor Citation2008, 943). Women are told that purchasing products is the solution to the host of problems with which the female body is beset. By solving those problems, or at least staving off their effects for a period, the body is ostensibly improved, and empowerment becomes one step closer. Feminist activism is limited to choosing which product to buy. Consumption becomes the primary “expression of female bodily autonomy and choice” (Kim Toffoletti and Holly Thorpe Citation2018, 302).

Dieting versus consumption

In light of the postfeminist focus on the body and consumption as the road to empowerment, food is a fundamental site of tension. As Julie Guthman and Melanie DuPuis (Citation2006, 443) state, “we buy and eat to be good subjects”, but this is at odds with dieting messages to enact control and restrict consumption of food (Susan Bordo Citation1993). In a market-oriented culture, which celebrates consumer choice as an expression of freedom and empowerment, the good citizen cannot also be characterised by restraint. But how can the modern woman satisfy imperatives both to eat and to not eat? It is an impossible dilemma (Lin Bailey, Christine Griffin and Avi Shankar Citation2015).

One possible solution is to follow both imperatives by deliberately and overtly switching between them at sanctioned points. There have been suggestions that the ideal feminine, neoliberal subject is someone who knows how to control her body but, when hard work is done, knows when to indulge. This indulgence is permitted under the protective umbrella of “deservingness” (Guthman and DuPuis Citation2006). This framing does give women some breathing room, but the tension is still present, with only time limited periods of reprieve.

One concept that has attempted to reconcile the two imperatives of calorific restriction and hedonistic consumption is what Kate Cairns and Josee Johnston (Citation2015) refer to as the “Do-Diet”. In their analysis of interviews and focus groups with women, alongside health-focused food writing, they observe how this tension has been resolved through a process of reframing. Instead of diets being expressed in terms of restriction, dieting is articulated as “healthy eating”, consisting of a series of positive consumption choices. They term this the “Do-Diet” (as opposed to the “Don’t-Diet”). The Do-Diet offers a “win-win” solution whereby consumers can both exercise restraint in terms of ingesting calories and simultaneously satisfy consumptive imperatives. Still, the spectre of restriction is present, inherent in the choice of foods that are open to women: they must still be “healthy” (however that is defined). Once again, women are trapped in the liminal space between decrees to exhibit both restraint and unbridled consumption.

The observation that women are frequently faced with impossible dilemmas is not a new proposition. Femininity has been understood in the postfeminist literature as “a profoundly contradictory and dilemmatic space which appears almost impossible for girls or young women to inhabit” (Christine Griffin, Isabelle Szmigin, Andrew Bengry-Howell, Chris Hackley and Willm Mistral Citation2012, 184). Unsurmountable contradictions, inconsistent logic and opposing demands characterise postfeminist media messages (Bailey, Griffin and Shankar Citation2015; Griffin et al. Citation2012). These spaces require balancing acts and paradoxical performances from women (Cairns and Johnston Citation2015; Bailey, Griffin and Shankar Citation2015).

Therefore, the question that drives this paper is, “how does FTC solve the impossible dilemma of the simultaneous call to both consume and to restrict consumption?” In our analysis we argue they do this through a process we conceptualise as the “Erasure of Labour”.

Method

Data collection

We collected data from the FTC Instagram account in the form of photographs or slogan posts and their associated comments.

We collected all photographs and their comments posted over 4 months, from January 7 2018 to April 30 2018, resulting in a data set of 270 photos. We also collected all slogans and their comments posted from January 8 2018 to November 22 2018, resulting in a data set of 98 slogans. The window for data collection was longer for slogans because they were posted less frequently.

Data analysis

We analysed the whole data set in two stages. Initially the second author conducted a social constructionist informed thematic analysis of the data (Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke Citation2006). This consisted of reading, re-reading and coding the entire data set. These initial codes were collated in order to establish an outline of potential themes which responded to the research question. The research team then worked collectively, discussing the themes and undertaking a more in-depth analysis, informed by postfeminist and neoliberal theory, negotiating different interpretations until we arrived at consensus. We then interrogated potential “interpretative repertoires” underpinning FTC’s marketing rhetoric. An interpretative repertoire can be defined as a “recognisable routine of arguments, descriptions and evaluations, distinguished by familiar clichés, common places, tropes and characterizations of actors and situations” (Nigel Edley and Margaret Wetherell Citation2001, 443). Finally, we identified relevant exemplars from across the images, slogans and comments that most clearly illustrated the central tenants of each interpretative repertoire.

Analysis

We identified three distinct but related interpretive repertoires. The first “be fit even though you’re lazy”, the second “be thin even though you binge”, the third “be empowered even though you’re weak”. These repertoires are based on two premises that set up an impossible dilemma: “you must attain an ideal” and, “the reality is you cannot attain the ideal”. This dilemma is then solved by offering the logical conclusion: “consume our product”.

The consistent rhetoric from each repertoire is “don’t try, you will fail”, which leads logically and inexorably to FTC products that promise to make difficult, nay impossible, work unnecessary. It also reifies the neoliberal approach to the body by generating insecurity and then providing an individualised product as a solution (Brown et al. Citation2020).

Be fit even though you’re lazy

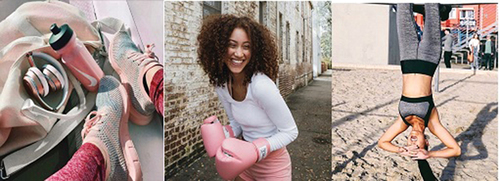

The call to be fit is frequently illustrated with images of gym paraphernalia and women exercising. Running shoes, weights, women holding yoga poses or wearing boxing gloves: reminders to do literal work on the body are ubiquitous. This fitness imperative has been identified extensively by postfeminist researchers (Pirkko Markula Citation1995; Riley and Evans Citation2018; Toffoletti and Thorpe Citation2018).

Postfeminist and neoliberal discourses about the body locate it as a site of work, as something that needs cultivating and regulating (Chris Shilling Citation2012). There is a call for discipline of the female body in the pursuit of perfection (Margaret Carlisle Duncan Citation1994), where it is the individual’s responsibility to engage in improving activity (Paul Crawshaw Citation2007). This is clearly conveyed through images posted by FTC’s Instagram account, where audiences are enjoined to exercise. They display an abundance of flesh, and are presented as sexualised objects, required to maintain a hyper-sexualised feminine appearance even when engaging in physical work.

The message conveyed through these images is in complete contrast to the written messages with which women are presented.

Slogan set 1: examples of slogans telling audiences they are lazy

Real talk. Stairs are so much prettier when you’re looking at them, and not running up and down them.

Too bad we can’t get abs by laughing at our own jokes. We’d totally have a six pack by now.

Unless you fell on the treadmill, no one cares about your workout.

These slogans undermine any nascent drive to engage in work on the body. They tell women that their default state is one of laziness. This is a risky message for a company to state explicitly because they run the risk of angering or alienating their customers. To negate this, FTC employ humour to allow them to say the unsayable: namely that their customers are inherently lazy. Humour gives FTC a response to potential criticism, in that they can hide behind a defence of “we’re just joking”. This strategy is reinforced through the use of “we”, wherein they position themselves as suffering from the same weakness as their audience.

Crucially, the novel message is that women are expected to obey the exercise imperative whilst accepting the impossibility of working on the body. Moreover, the impossibility of doing work on the body is dismissive of women’s agency, positioning them as lacking the necessary motivation and discipline. We will see that this lack of regard for women’s abilities underlies all three interpretive repertoires. This sets the scene for the resolution provided by FTC products which claim to negate the necessity for work.

Be thin even though you binge

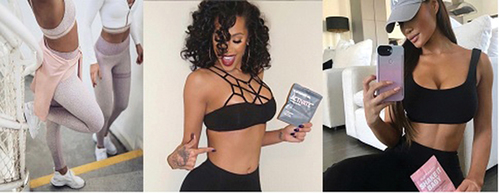

Images endorsed by FTC call for women to be thin. Although there are many women with large, shapely buttocks and breasts, tummies were slender and flat.

These images are embodiments of the sexualized postfeminist bodily ideal. This echoes Gill’s (Citation2008, Citation2009) analysis of midriff advertising as consisting of young, conventionally attractive, hyper-sexualised and hyper-feminised women, depicted knowingly and deliberately flaunting their presumed sexual power. This is evident in the FTC images, through pouting lips, arched backs, sultry looks and exposed half-naked bodies.

Strikingly, whilst presented as sporty, they are completely devoid of toned muscles. Muscles imply strength and power and are typically associated with men and masculinity and are thus problematic for women (Chris Shilling and Tanya Bunsell Citation2009). This analysis is exemplified by Pirkko Markula (Citation1995) who identifies a contradictory media ideal specific to fitness industries where women are required to be “firm but shapely, fit but sexy, strong but thin”.

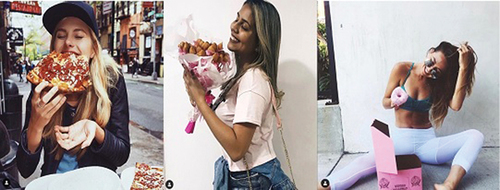

This unspoken call to “be thin” is undermined by pictures and text that give the opposite message, namely consume junk food and drink alcohol. Pictures show women sent into raptures of delight by the promise and consumption of food. Pizzas are crammed into smiling mouths; bouquets of fried chicken are gazed at with love; and donuts viewed with delight.

The imperative to consume calories through junk food and alcohol is also conveyed through slogans, where consumption of food and alcohol is portrayed as something fun and necessary. Again, we see the use of humour and the first person plural “we” to make the unsayable (high calorie consumption), sayable.

Slogan set 2: examples of slogans calling for audiences to consume calories

Our goal weight? Whatever we weigh now plus a burrito.

A banana is 105 calories. A glass of prosecco is 80. Choose wisely, babes.

We make wine disappear. What’s your superpower?

Once again, we see audiences presented with an impossible dilemma (Bailey, Griffin and Shankar Citation2015) to emulate the visual portrayals of thinness and to consume high calorie food and drink. In fact, they are urged to consume calories in their most excessive, hedonistic form. Yet, unlike other discourses about body management that require women to control their calorie intake, either by switching between consumption and restriction, or by only consuming “healthy” food (Cairns and Johnston Citation2015; Guthman and DuPuis Citation2006), FlatTummy Co. resolve this dilemma. They tell women that they can be thin and consume high calorie junk food and alcohol as long as they also consume the company’s products. This brings us to the final interpretive repertoire which specifically addresses self-control, something that has been bubbling under the imagery and slogans about fitness and thinness.

Be empowered even though you’re weak

In this final interpretative repertoire we see the most explicit undermining of women’s agency. In the previously discussed repertoires, being fit and thin are the ideals, but laziness and bingeing are positioned as inevitable because women are inherently weak and lacking in self-control.

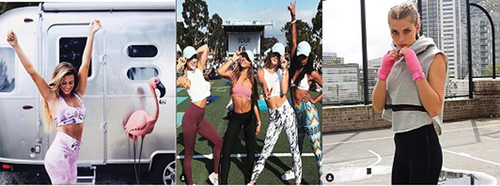

Images and slogans invoke tropes of power and emancipation. Women are depicted as confident and exhilarated, jumping into the air; or aggressive, confronting the camera with a direct, focussed stare.

Slogans are used to support this call to power. And here we see vocabulary which has words like “kill” and “savage”.

Slogan set 3: examples of slogans calling for audiences to be empowered

Yep, you freaking killed it.

She’s killing it.

Be savage, not average.

Interestingly, slogan metaphors are particularly aggressive, rather than assertive, where everything is a battle. Lazar Citation2006 noted the use of warfare metaphors in her analysis of “power femininity” in Singaporean advertising to women. In both Lazar’s paper and our own analysis, aggression is constructed as equivalent to power.

At the same time, slogans tell women the battle to be empowered is unwinnable. The viewer is told that they, and the writers, are lacking in self-control and cannot be held responsible for their actions and emotions.

Slogan set 4: examples of slogans telling audiences they’re weak

Accidently got a side of fries, instead of a salad … again.

Self control goes out of the window, when buying snacks for a road trip.

We have ABS … absolutely no self-control.

The writers tell audiences that they are weak and have no self-control. In a neoliberal, postfeminist context, where women are called upon to exercise self-discipline and manage their bodies and selves, this is an unsayable proposition. The only way to communicate this is by shrouding it in humour and jokes and a “we’re all in this together” cliché. It is acceptable to belittle the reader because the writer is belittling themselves at the same time.

Erasing the labour

Having presented women with three impossible dilemmas: be fit even though you’re lazy; be thin even though you binge; be empowered even though you’re weak, what are women to do? In answer, for the first time, women are told they do not have to work on their bodies, they do not have to exercise, diet or be empowered. In other words, the contradiction or dilemma disappears because FTC products erase the labour required to achieve the ideal. This is epitomised in images where junk food is shown side by side with a FTC product.

The dilemma is particularly addressed in the comments accompanying slogans and images. While the images and slogans present the contrasting ideals and “realities”, FTC comments on their own posts with whispers of an easy resolution. Comments explicitly reinforce the idea that being lazy, bingeing and being weak are no longer problems because FTC products provide a solution.

Slogan set 5: examples of comments that provide a solution

Craving something sweet? We’ve got just what you need to satisfy your cravings without getting off track.

Usually we’d be reaching out for something sweet right now. But since we’ve got our Flat Tummy shakes on subscription we’ve been keeping our cravings in check.

The reassuring message women are given is that work, restraint and control are unnecessary. Unbridled consumption is acceptable, even expected, as long as they consume FTC products.

Discussion

In Gill’s (Citation2008, 44) analysis of midriff adverts she identified “The cost, the labour, the discipline, the shame, the violence, the pain and the anxiety associated with disciplining the female body to approximate to current standards of female beauty”. Alternatively, FTC does not paint over the labour associated with feminine beauty ideals, rather they erase the need for labour. And where Cairns and Johnston (Citation2015) identified a tension at the heart of neoliberal consumer culture between embodying discipline through dietary control and expressing freedom through consumer choice, FTC says there is no tension because there is no need to embody discipline or control, in other words, labour is not necessary. This concept of Erasure of Labour is a new contribution to the literature.

Erasure of Labour can be seen in each of the three repertoires we identified, two focussing on the physical self (food and exercise), and one on the psychological self (feeling empowered). What follows is a contextualisation and exploration of the concept of Erasure of Labour.

In the first repertoire “be fit even though you’re lazy”, images depict active women surrounded by gym equipment. Thus, FTC remind women of the work they are expected to do. This conflicts with the slogans that explicitly tell women not to exercise because it is too hard. This offers a radical contrast to research by Riley and Evans (Citation2018) that documents women being exhorted to engage in extensive amounts of exercise and work on the physical self. Our paper has, for the first time, observed an alternative message, namely that women do not need to do exercise—the labour imperative is erased.

The second repertoire “be thin even though you binge” contrasts thin bodies with binge eating and drinking. The ideal body is promoted through photographs of slim, flat midriffs and sexualised flesh. This contrasts with photos of women gorging on junk food, and messages reminding women how desirable fast food and binge drinking are. Here we see a manifestation of the neoliberal imperative to consume which sits uneasily with the necessity to limit calorie consumption. Cairns and Johnston (Citation2015) suggest this tension can be resolved with their concept of the “Do-Diet”, where food consumption is encouraged, as long as it is the “correct” type of food. In contrast, the junk food and alcohol valorised by FTC does not fit within the boundaries of “correct” foods. FTC steam roller through the intricate requirements of dieting by claiming the labour inherent in managing calorie consumption is unnecessary.

The logic of this rhetoric is cemented by the third repertoire: “be empowered even though you’re weak”. Images of powerful women are paired with jokey messages about the impossibility of self-control. FTC tells their customers they are psychologically flawed, but it softens this bleak message by couching it in humour and including themselves in the category. This sits in stark contrast to the body positivity movement that ostensibly releases women from aspiring to a physical ideal, but instead replaces it with a new psychical ideal namely, to be positive and confident (Rosalind Gill and Ana Elias Citation2014). FTC does not require their audience to either labour to attain the thin ideal (as in neoliberal messages), or to labour to be content with not being an ideal shape (as in body positive messages). Instead, they offer a solution requiring no labour at all: simply to buy their products.

Having discussed the three repertoires evidenced in our data, we now move to abstracting the features that were apparent across all of them, namely: ideals, reality and solution. Erasure of Labour has three components: first to promote an ideal, second, to dismiss the possibility of achieving the ideal, and finally to offer a product as the way to resolve the tension between the two. The three ideals featured in the three repertoires were: “be thin”, “be fit” and “be empowered”. These three pillars of ideal femininity are so obviously located in twenty-first century, Western, postfeminist culture, and exemplify well-trodden requirements for the self-enhancement drive of physical and psychological labour (Elias and Gill Citation2017; McRobbie Citation2009; Riley and Evans Citation2019). For example, there have been long standing discussions about the “tyranny of thinness”, requirements to discipline the body through exercise, and the more recent imperative for psychological empowerment, often connected to body positivity discourses (Bordo Citation1993; Carlisle Duncan Citation1994; Gill and Elias Citation2014). FTC tells women to aspire to, rather than question, these ideals.

Women might assume that to achieve these ideals they need to undertake aesthetic, physical and psychological labour. And indeed, this exhortation to do work on the self epitomises the neoliberal construction of humans as consumers who must constantly strive to improve (Derek Hook Citation2004). However, women are simultaneously presented with the supposed “reality” that they are lazy, greedy and psychologically weak. The labour, discipline and restraint necessary to attain these postfeminist ideals is positioned as unachievable. This is the second component of Erasure of Labour. These messages are denigrating to women, designed to undermine women’s felt sense of autonomy and agency, and thus set up the conditions for dependency on the company’s products.

It is the intermediate “reality” step which distinguishes FTC’s marketing from that of other weight loss products and general advertising. Traditional advertising takes a “product-solution” approach (Gill Citation2009). Thus, in the case of weight loss products, we see a foregrounding of ideals and a promise that the product will enable attainment of those ideals. More sophisticated advertising campaigns might ostensibly pretend to disrupt the model and challenge the legitimacy of those ideals. An example of this within the weight loss arena are campaigns which fall under the “Love Your Body” umbrella. An example of this is the 2013 Special K campaign which invited women to “rethink what defines” them (Emma Luck Citation2016). But FTC does something very different. Love your body discourses exhort women to “be empowered” or “Awaken [their] incredible” (Gill and Elias Citation2014), FTC say that women do not have the ability to be empowered and incredible. Their reality is that women are fat, lazy and weak.

The pervasive use of humour to couch these messages is an indicator of just how offensive they are, it makes the unsayable sayable. FTC’s use of humour encourages women to admit to their weaknesses and flaws, partly by adopting a friendly “we’re in it together” position. But ultimately, underneath the humour is a belittling message.

Women are left with an impossible dilemma, how to achieve ideals whilst faced with the “reality” that they are personally incapable. Women find themselves stranded in a contradictory space with no viable exit. Enter FTC, with their solution. This third component of Erasure of Labour resolves the impossible dilemma between postfeminist ideals and the supposed “reality” of the inaccessibility of those ideals.

Our initial research question asked how to reconcile the impossible dilemma thrown up by the case of dieting. In other words, how women could be encouraged to be good consumers, but also to restrict consumption. In addition, through the analysis of FTC. images and slogans, we identified a more interesting dilemma between postfeminist ideals and supposed reality. Both dilemmas (consumption vs restriction and ideals vs reality) are resolved by FTC. products. Here we see neoliberal consumption offered as a solution to women’s problems. Women are said to gain power through the purchase of products (Brown et al. Citation2020), ostensibly leading to a “win-win” for women and for neoliberalism.

Through offering their products, FTC tells women there is no work to do: the labour associated with diet, exercise and psychological empowerment is disappeared, in the way of a magic trick. This illusion is what we refer to when we talk about the concept of Erasure of Labour. Erasure of Labour is the process by which tiring and difficult work on the body and the self vanishes, leaving no necessity for effort. In the case of FTC, the difficult steps required to minimise the distance between a current state and an ideal state are removed through the talismanic properties of their weight loss products. Erasure of Labour messages are presented as freeing and simple. These seemingly beautiful and elegant solutions promise the achievement of socially desirable goals without the associated work. However, this magic trick, like all tricks, is an illusion.

FTC, begrudging acknowledges the illusion, tucked away in the fine print on the “Flat Tummy Tips” page of their website. There they say, “Be real, if you want a flat tummy, you’re going to need to do at least a little exercise.” And later, on the same page, “Eat less. Let’s be honest, most of us could be eating smaller portions and avoiding that post food coma.” This roll back from extolling the effects of their products is evidenced by research on nutritional effects that concludes that supplements in their products have either not been tested, or tested and found not to have any weight loss effects (apart from one, senna, a natural laxative, which is potentially dangerous) (Wong Citation2019; Heidi Michels Blanck, Mary Serdula, Cathleen Gillespie, Deborah Galuska, Patricia Sharpe, Joan Conway, Laura Kettel Khan and Barbara Ainsworth Citation2007).

Erasure of Labour is a new and pernicious framing of a way to achieve ideals. Some published literature has analysed the downplaying of labour for example, solutions offered to men for how to achieve masculine ideals, such as “Five Minute Abs”. Here, the labour imperative is minimised but not completely erased (Paul Crawshaw Citation2007). Significantly, these quick fix messages are not presented simultaneously with encouragement to be lazy, to binge and abdicate discipline. We see Erasure of Labour messages as both more seductive and more dishonest. We feel it is important for critical feminist scholars and activists to reveal these illusions for what they are, thus equipping consumers with the means to evaluate them.

Limitations and future research

This paper focussed solely on FTC’s use of Instagram as a marketing tool rather than the other media at their disposal, for example their own website or billboards. We expect that we would see a similar underlying approach. We would be interested to see why FTC chose to use these repertoires and the technique of Erasure of Labour. It could be that they identified their target audience on Instagram to be particularly receptive to this message, or that they believe it is particularly appropriate within the wider current cultural context. Our analysis was conducted at the local level, further research would need to be conducted on their marketing intentions to answer this question.

It was not in the scope of this paper to look at the way these messages are received by audiences, but it would be of interest to see if women have detected these Erasure of Labour messages. We are interested in how women inhabit the contradictions and negotiate the impossible dilemma of resolving ideals and reality. It would be interesting to examine whether influencer posts and user comments reify FTC’s techniques, in other words if there is a cyclical reinforcement, or whether the users are more passive recipients.

Conceptually, we encourage researchers to look for Erasure of Labour messages in other domains. This is the first time this phenomenon has been identified in media and it would be strengthened as a concept by replications in other fields. We wonder if this denial of labour imperative might be present in areas such as breast enhancement, penis extension and liposuction surgery. We also wonder if the concept could be broadened out from work on the body and self, to work more generally, for example in pyramid selling schemes. When looking for parallel cases we would expect to see companies to proceed through the three steps: first, promoting an ideal; second, telling their audiences that they cannot attain that ideal through ordinary work; and finally, offering an effortless solution through consumption of their product.

As well as offering this conceptual lens to researchers, we also seek to support and inform the work of feminist activists. This academic analysis should prove useful in the quest to resist seductive marketing messages by pulling the curtain back on their illusory nature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bailey, Lin, Christine Griffin, and Avi Shankar. 2015. “‘Not a Good Look’: Impossible Dilemmas for Young Women Negotiating the Culture of Intoxication in the United Kingdom.” Substance Use & Misuse 50 (6): 747–758. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.978643.

- Blanck, Heidi Michels, Mary Serdula, Cathleen Gillespie, Deborah Galuska, Patricia Sharpe, Joan Conway, Laura Kettel Khan, and Barbara Ainsworth. 2007. “Use of Non-prescription Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss is Common among Americans.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 107 (3): 441–447. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009.

- Bordo, Susan. 1993. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. London: University of California Press.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brown, Nicola, Christine Campbell, Craig Owen, and Atefeh Omrani. 2020. “How Do Girls’ Magazines Talk about Breasts?” Feminism & Psychology 30 (2): 206–222. doi:10.1177/0959353519900203.

- Cairns, Kate, and Josee Johnston. 2015. “Choosing Health: Embodied Neoliberalism, Postfeminism, and the ‘Do-diet’.” Theory and Society 44 (2): 153–175. doi:10.1007/s11186-015-9242-y.

- Crawshaw, Paul. 2007. “Governing the Healthy Male Citizen: Men, Masculinity and Popular Health in Men’s Health Magazine.” Social Science & Medicine 65 (8): 1606–1618. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.026.

- Duncan, Margaret Carlisle. 1994. “The Politics of Women’s Body Images and Practices: Foucault, the Panopticon, and Shape Magazine.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 18 (1): 48–65. doi:10.1177/019372394018001004.

- Edley, Nigel, and Margaret Wetherell. 2001. “Jekyll and Hyde: Men’s Constructions of Feminism and Feminists.” Feminism & Psychology 11 (4): 439–457. doi:10.1177/0959353501011004002.

- Ehlers, Kelly. 2017 “May We Have Your Attention: Marketing to Millennials.” Forbes. Accessed 2 March 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/yec/2017/06/27/may-we-have-your-attention-marketing-to-millennials/?sh=77a3b0f01d2f

- Elias, Ana, Rosalind Gill, and Christina Scharff, eds. 2017. Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism. London: Palgrave MacMillian.

- Foucault, Michel. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. London: Springer.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166. doi:10.1177/1367549407075898.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2008. “Empowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary Advertising.” Feminism & Psychology 18 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1177/0959353507084950.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2009. “Supersexualize Me! Advertising, (Post)feminism and ‘The Midriffs’.” In Mainstreaming Sex: The Sexualisation of Culture, edited by F. Attwood, R. Brunt, and R. Cere, 93–109. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Ana Elias. 2014. “‘Awaken Your Incredible’: Love Your Body Discourses and Postfeminist Contradictions.” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 10 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1386/macp.10.2.179_1.

- Griffin, Christine, Isabelle Szmigin, Andrew Bengry-Howell, Chris Hackley, and Willm Mistral. 2012. “Inhabiting the Contradictions: Hypersexual Femininity and the Culture of Intoxication among Young Women in the UK.” Feminism & Psychology 23 (2): 184–206. doi:10.1177/0959353512468860.

- Guthman, Julie, and Melanie DuPuis. 2006. “Embodying Neoliberalism: Economy, Culture, and the Politics of Fat.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (3): 427–448. doi:10.1068/d3904.

- Hamad, Hannah, and Anthea Taylor. 2015. “Introduction: Feminism and Contemporary Celebrity Culture.” Celebrity Studies 6 (1): 124–127. doi:10.1080/19392397.2015.1005382.

- Holliday, Tess. 2018. “Remove Flat Tummy Ads From Times Square.” Change.org [ Petition]. Accessed 3 March 2020. https://www.change.org/p/flat-tummy-co-remove-flat-tummy-ads-from-times-square

- Hook, Derek. 2004. “Governmentality and Technologies of Subjectivity.” In Introduction to Critical Psychology, edited by Derek Hook, 239–271. Lansdowne: UCT Press.

- Jamil, Jameela. 2019. “Twitter Post.” January 19. https://twitter.com/jameelajamil

- Jerslev, Anne, and Mette Mortensen. 2016. “What is the Self in the Celebrity Selfie? Celebrification, Phatic Communication and Performativity.” Celebrity Studies 7 (2): 249–263. doi:10.1080/19392397.2015.1095644.

- Johnston, Josee, and Judith Taylor. 2008. “Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33 (4): 941–966. doi:10.1086/528849.

- Lazar, Michelle. 2006. “‘Discover the Power of Femininity!’ Analyzing Global ‘Power Femininity’ in Local Advertising.” Feminist Media Studies 6 (4): 505–517. doi:10.1080/14680770600990002.

- Lazar, Michelle. 2017. “‘Seriously Girly Fun!’: Recontextualising Aesthetic Labour as Fun and Play in Cosmetics Advertising.” In Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism, edited by Ana Elias, Rosalind Gill, and Christina Scharff, 51–66. London: Palgrave MacMillian.

- Luck, Emma. 2016. “Commodity Feminism and Its Body: The Appropriation and Capitalization of Body Positivity through Advertising.” Liberated Arts: A Journal for Undergraduate Research 2 (1): 1–9.

- Make it Tasmania. 2017. “Founded Ventures: Harnessing Global Influencers from the Hobart CBD.” [Blog]. https://www.makeittasmania.com.au/business/founded-ventures-harnessing-global-influencers-hobart-cbd/

- Markula, Pirkko. 1995. “Firm but Shapely, Fit but Sexy, Strong but Thin: The Postmodern Aerobicizing Female Bodies.” Sociology of Sport Journal 12 (4): 424–453. doi:10.1123/ssj.12.4.424.

- McNair, Brian. 2002. Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratisation of Desire. London: Routledge.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage.

- Riley, Sarah, Adirenne Evans, and Martine Robson. 2019. Postfeminism and Health: Critical Psychology and Media Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Riley, Sarah, and Adrienne Evans. 2018. “Lean Light Fit and Tight: Fitblr Blogs and the Postfeminist Transformation Imperative.” In New Sporting Femininities in Digital, Physical and Sporting Cultures, edited by Kim Toffoletti, Jessica Francombe-Webb, and Holly Thorpe, 207–229. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Riley, Sarah, Adrienne Evans, Sinikka Elliott, Carla Rice, and Jeanne Marecek. 2017. “A Critical Review of Postfeminist Sensibility.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 11 (12): e12367. doi:10.1111/spc3.12367.

- Ryan, Frances. 2018. “Jameela Jamil Is Right – The Kardashians are Double Agents for the Patriarchy”. The Guardian, September 3. Accessed 3 March 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/sep/03/jameela-jamil-is-right-the-kardashians-are-double-agents-for-the-patriarchy

- Sara, Rieke, Deborah Fowler, Hyo Chang, and Natalia Velikova. 2016. “Exploration of Factors Influencing Body Image Satisfaction and Purchase Intent: Millennial Females.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20 (2): 208–229. doi:10.1108/JFMM-12-2015-0094.

- Shilling, Chris. 2012. The Body and Social Theory. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Shilling, Chris, and Tanya Bunsell. 2009. “The` Female Bodybuilder as a Gender Outlaw.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 1 (2): 141–159. doi:10.1080/19398440902909009.

- Toffoletti, Kim, and Holly Thorpe. 2018. “The Athletic Labour of Femininity: The Branding and Consumption of Global Celebrity Sportswomen on Instagram.” Journal of Consumer Culture 18 (2): 298–316. doi:10.1177/1469540517747068.

- Wong, Julia. 2019. “How Flat Tummy Co Gamed Instagram to Sell Women the Unattainable Ideal.” The Guardian, August 29. Accessed 3 March 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/aug/29/flat-tummy-instagram-women-appetite-suppressant-lollipops