ABSTRACT

In 2017, the #MeToo movement garnered international attention when millions of people used it to share experiences of sexual violence via social media. Through an analysis of 570 tweets randomly and purposively sampled within the first 24 hours of the movement, we were interested in answering the following questions: (1) What emotions are present in #MeToo tweets?; and (2) What are the vernacular practices in the #MeToo movement, and how do they convey affect? Through applying Robert Plutchik (2000) structural model of emotion, we were able to identify a wider range of emotions evident in feminist hashtag campaigns than has previously been identified and analyse their varied functions. Furthermore, we show how the difficulty in narrating personal experiences of violence and sharing discernible emotions via this hashtag fed into four vernacular practices, which we argue stimulate affect. Thus, the article contributes to a more nuanced understanding of two often conflated concepts—emotion and affect—and their different roles within #MeToo. The article ultimately shows how a movement such as #MeToo can be highly affective, even when participants disclose very little emotion or detail.

Introduction

Confessional practices and speaking our inner truths have been important parts of Western cultures and ways of life (Chloe Taylor Citation2009). Yet, those who experienced trauma struggle to verbalize the truth because language cannot adequately capture all traumatic experiences (Leigh Gilmore Citation2001). Despite this difficulty, millions around the world have taken to social media to precisely do this (Kaitlynn Mendes, Jessica Ringrose and Jessalynn Keller Citation2019a). With increasingly diverse, often non-verbal ways of sharing one’s experience of trauma, including the use of narrative, hashtags, videos, emojis, and images, digital feminist campaigns have emerged, giving people, particularly women survivors, the opportunity to speak previously unspeakable experiences of sexual violence. By the time Alyssa Milano encouraged people to share their experiences of sexual violence in October 2017 using the hashtag “MeToo,” sexual violence had already (re)emerged as a pervasive social problem in mainstream media globally, spurred by the global anti-rape SlutWalk movement, the brutal gang rape and murder of “Nirbyaha” in India, and the numerous allegations of sexual violence in Hollywood, Bollywood, and other recognized institutions. Although #MeToo was following in the footsteps of countless other digital campaigns (e.g., Occupy, 15-M Movement, and Kony), it nevertheless captured public and mainstream attention in an unprecedented way (see Rachel Loney-Howes, Rachel Loney-Howes, et al. Citation2021).

#MeToo is a worthwhile phenomenon to investigate–not just because of the scale of participation–being used 19 million times in the first year alone (Dalvin Brown Citation2018), or the ways it has been searched by people in every country on earth (Me Too Rising Citation2018), but because of its affective pull and impact. Despite challenges inherent in sharing traumatic experiences (Leigh Gilmore Citation2001), research with #MeToo participants has shown how many people (particularly those with various privileges) felt both compelled to contribute to the hashtag or could no longer remain silent on the issue of sexual violence (see Kaitlynn Mendes and Jessica Ringrose Citation2019). Indeed, the affective turn in scholarship has drawn attention and interest to the subconscious ways in which people are “moved” to action (James Jasper Citation1997; Sara Ahmed Citation2017).

While there is a significant and growing body of research exploring #MeToo (see for a review: Anabel Quan-Haase, et al. Citation2021), the purpose of this paper is to contribute to the literature on the affective dynamics of #MeToo. Recognizing that affect is not just generated by emotional language, but by the form it takes (Kaitlynn Mendes, Jessalynn Keller and Jessica Ringrose Citation2019a), we also apply the framework of platform vernacular (Martin Gibbs, James Meese, Michael Arnold, Bjorn Nansen, and Marcus Carter Citation2015) to identify the affective communicative conventions of participating in the #MeToo movement. We pose two research questions:

What emotions are present in #MeToo tweets?

What are the vernacular practices in the #MeToo movement, and how do they convey affect?

To learn about the affective pull of #MeToo, we examine tweets posted in the first 24 h after Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet. By manually coding a sample of 570 of these tweets, we found the most common emotions expressed were sadness and trust, followed by anger, fear, and disgust. Yet the expression of emotion was often nuanced, and indeed most tweets contained no discernible emotions at all. While previous research has shown how “affective publics” (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015) are forged through public displays of emotion, our analysis shows how the difficulty of emotional expression in #MeToo is directly linked to four vernacular practices that generate affect: 1) signalling participation without sharing a personal story, 2) indirect reference to perpetrators, 3) speaking to the void, and 4) using euphemisms to indicate personal experiences. The article ultimately shows how a movement such as #MeToo can be highly affective, even when participants disclose very little emotion or detail.

Affect and emotion

Affect is an overarching concept crossing many disciplinary boundaries and time periods (Teresa Brennan Citation2004). Definitions often stress how a focus on affect discerns “the non-verbal, non-conscious dimensions of experience” as a form of “reengagement with sensation, memory, perception, attention and listening” (Lisa Blackman and Couze Venn 2010, 8). While affect and emotion are often discussed together because of their conceptual overlap, the two terms have different connotations and functions. Brian Massumi Citation2003 articulates affect as a non-conscious, non-subjective experience that is independent of meaning and intent, while emotion is a conscious, subjective, and personal experience. Similarly, for Eric Shouse Citation2005), the “abstractivity” of affect enables it to be “transmittable in ways that feelings and emotions are not,” making it a potentially powerful social force. Brian Massumi (Citation2003) captures how they are distinct yet related: emotion comprises the expression of affect in gesture and language. This makes emotion narrativizable through personal expressions of a person’s feelings and closely associated with social and cultural conventions, often embedded in language use.

While emotions are narrativizable, they are nevertheless challenging to recognize and classify. To illustrate how a person experiences emotion, Robert Plutchik (Citation2000) developed a structural model, which combines the intensity, similarity, and polarity of emotions by a three-dimensional geometric model. This model proposes eight basic emotions, each with three intensity levels, as well as emotion dyads that emerge when combining adjacent pairs of basic emotions. For example, combining anticipation and joy yields optimism. This model offers a nuanced classification of basic emotions and their interrelations and has been a useful analytical tool for researchers (Riordan Monica Citation2017).

Taken together, the close relationship between affect and emotion makes disentangling affect from emotion difficult. In the present study, we therefore examine emotions as personal expressions of recognized, structured, and formed affects that manifest in narratives on Twitter. Because the “abstractivity” of affect makes it difficult to fully grasp its unfixed components, we investigate vernacular practices to further understand how affect unfolds beyond emotion.

Digital feminist engagement with affect and emotion

Influenced by the affective turn in recent scholarship, feminist scholars have engaged with affect and emotion in feminist politics, including affect enabling transformative ways of knowing (Carolyn Pedwell Citation2012; Clare Hemmings Citation2012), the role of affect and emotion in oppression (Sara Ahmed Citation2014), and how the two create solidarity in feminist resistance (Ahmed Citation2014; Clare Hemmings Citation2012; Lauren Berlant Citation2008). For Ahmed (Citation2014), publicly shared emotions contribute to moving and holding people in place and play a crucial role in “shaping the ‘surface’ of individual and collective bodies” (1).

Scholars have also shifted their attention toward understanding the role of affect in popular digital feminist movements such as #BeenRapedNeverReported, #WhyIStayed, #SafetyTipsForLadies. Studies on digital feminist activism suggest that affect plays an important role in mobilizing and motivating participation (Mendes et al. Citation2019a; Kaitlynn Mendes, Jessica Ringrose and Jessalynn Keller Citation2019b; Kristi McDuffie and Melissa Ames Citation2021), connecting participants of digital campaigns (Tetyana Lokot Citation2018; Jasmine R Linabary, Danielle J. Corple and Cheryl Cooky Citation2020; Kim Toffoletti and Holly Thorpe Citation2020) and in-person protests (McDuffie et al. Citation2021). Together, this research suggests that affect is both a means to create solidarity and community, as well as a force toward mobilization. Yet, affect can also function as a counterforce that causes disengagement (Linabary et al. Citation2020). In their study of tweets linked to #WhyIStayed, the affective dimension led to participants needing to “take a break of Twitter” because of feelings of distraught. And emotions like anger also constitute negative social reactions to the backlash resulting from the campaigns (Kimberly T. Schneider and Carpenter 2019).

Some research has looked at emotion and affect within a single study (Jessica McLean, Sophia Maalsen and Sarah Prebble Citation2019). For example, in McLean et al.’s (Citation2019) case study of the Australian feminist campaign Destroy the Joint (DTJ), the authors found that affect is expressed in “likes” on Facebook or “hearts” on Twitter, whereas emotion is shown in posts and tweets. The study concludes that “affect underpins the mundane ‘liking’ that keeps activity churning along in DTJ” (756). They also describe how varied emotions in DTJ, ranging from anger, hope, sadness, grief, wry humour, to bitter disappointment, coalesce and disappear, emerge and dissolve is helpful in facilitating feminist interventions. Given the different ways that affect and emotion are conceptualized across studies, it is rarely examined how they are conveyed and circulated together in digital feminist activism. Thus, looking at both in a single study is an important new direction.

Similarly, emotions in #MeToo can be both mobilizing and limiting. Kimberly T. Schneider and J. Carpenter Nathan’s (Citation2019) study found that emotional expressions, such as gratitude to those who disclosed stories, and anger and sadness in reading about other’s incidents, are observed in both positive and negative social reactions to disclosures. Studies also found that anger, as a palpable emotion, did not simply motivate speaking up, but rather anger expressed in different ranges and intensities elevated some voices while marginalizing others (Emily Emily Winderman Citation2019), adding complexity to the role of emotion in #MeToo.

Affect and emotion were often difficult to disentangle in #MeToo, where discernable emotions, such as anger and sadness (Emily Winderman Citation2019; Schneider et al. Citation2019), and the more abstract affects, including mutual support and encouragement of speaking up (Rosemary Clark-Parsons Citation2019), are often embedded in narratives of the traumatic experiences of sexual violence. As affect and emotion are evident in #MeToo, how they are conveyed together with the affordances of social media is not yet fully understood. Following our attention to affective dimension of the #MeToo movement, we are interested in exploring not just the emotions present but the “form and texture” (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015, 9), which may cultivate affective solidarities within the early stage of #MeToo, a time in which the norms or vernacular practices of collective sharing are emerging.

Platform vernaculars on sexual violence

Scholars have paid close attention to how experiences of sexual violence are narrated–with the understanding that narrations shape the way people understand their assault (see Stacey L. Young and Katheryn C. McGuire Citation2003). While research has historically focused on a range of spaces in which disclosures occur, including in court, the media, autobiographical accounts, and interviews (see Irina Anderson and Kathy Doherty Citation2007; Leigh Gilmore Citation2001; Tami Spry, Citation1995; A. Wood Linda and Heather Rennie Citation1994), there has more recently been increased attention to disclosure of sexual violence in digital narratives (Kaitlynn Mendes, Katia Belisário and Jessica Ringrose Citation2019c). Scholars have begun to theorize the narrative forms that circulate online and their entanglements with technological, cultural, and material factors (Mendes et al. Citation2019a), drawing on the concept of the “platform vernacular” (Martin Gibbs, James Meese, Michael Arnold, Bjorn Nansen, and Carter, Citation2015). According to Gibbs et al. (Citation2015), each social media platform develops its own combination of styles, practices, grammars, and logic, which shape dominant conventions of how narrations unfold.

Platform vernacular is a useful concept for understanding how group communication and practices emerges on social media whilst acknowledging that digital platforms are governed by social norms, conventions, practices, and technological constraints (Katie Warfield Citation2016). We are also drawn to platform vernacular because it negates technological determinism and instead demonstrates how social practices emerge within social media platforms and their technological affordances as well as the dynamics of specific campaigns, such as #MeToo.

Previous research has suggested that affect and emotion are part of what drives feminist activism on social media, and that social media affordances have given rise to vernacular practices which are instrumental in expressing affect and emotion. This paper is driven by our curiosity on how these dynamics apply to the #MeToo movement on Twitter.

Materials and methods

Data set

To learn about the affective pull of #MeToo, we selected a publicly available dataset of tweets generated on October 162,017, the day after Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet (CBS News Citation2017). We chose this data set because we wanted to prioritize “spontaneous” tweets that were likely to be emotionally and affectively charged. By focusing on tweets that had been written only within hours of Milano’s, we aimed to capture responses to #MeToo that expressed intensities that may “not yet been cognitively processed as feelings, emotions, or thought” (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015, 22–23). Furthermore, the focus on emotion meant that personal stories and reactions would be more valuable to our analysis than, for example, tweets from news outlets, which became more prominent later as the movement spread. We expected that a data set sourced soon after the emergence of the hashtag would contain a high share of personal responses and a low share of analytic and mediated content about the movement (e.g., news articles) as well as fewer attempts to “co-opt” the hashtag, i.e., using a trending hashtag to draw attention to unrelated content (Mendes et al. Citation2019a).

Sample

The data set was accessed from the data-sharing website data.world (Hamdan Azhar Citation2017) and contained 28,561 tweets. To learn about affect and emotion, we reduced the data set to a manageable size that allowed for manual coding and close reading (Dhiraj Murthy Citation2017). We employed a combination of purposive and random sampling techniques to obtain a diverse set of tweets rather than a representative set Dhiraj Murthy Citation2017. First, we selected the 50 tweets that showed the most engagement, meaning that they had the highest numbers of retweets and likes. Next, we selected a random sample of 1,479 tweets in the data set that contained at least one emoji–or a “graphical symbol used to represent faces or objects” (Thomas Daniel and Alecka Camp Citation2020, 208). We deliberately included tweets with emojis based on scholarship showing their main purpose is to convey emotion and affect (see A. Riordan Monica Citation2017). Finally, we drew a random sample of 400 tweets from the remaining data set. By oversampling tweets with high engagement and emojis, we aimed for a high number of tweets with affective and emotional expressions. For ethical purposes, we reviewed all tweets during the coding process (in August 2020) to check if users had made them private or deleted them and excluded all tweets that were no longer available (Muira McCammon Citation2020). We also excluded duplicate tweets from our final sample. To compensate for the loss of data, we added another 313 tweets, of which 82 (26%) were no longer accessible, for a final sample of 570 tweets.

Data analysis

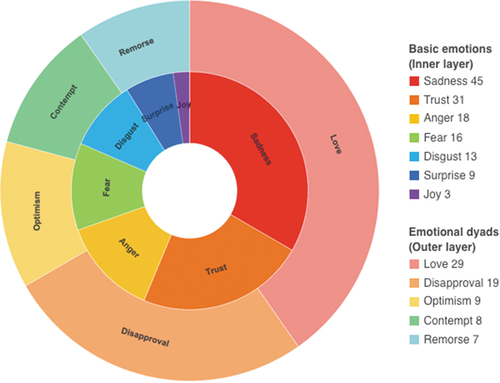

To analyze the Twitter corpus, we developed a code frame that incorporates the two main dimensions of our analysis: the emotive dimension and the vernacular practices utilized in conveying affective meaning. To measure emotion, we applied Robert Plutchik’s (Citation2000) structural model of emotion, including eight basic emotions (anger, disgust, sadness, surprise, fear, acceptance, joy, and anticipation) with three intensity levels for each emotion. The model also proposes emotional dyads where adjacent emotions combine into new emotions; for example, anger and disgust combine into contempt. We coded for the eight basic emotions, their levels of intensity, and the dyads based on the basic emotions (aggressiveness, optimism, love, submission, awe, disappointment, remorse, and contempt). To capture how Twitter users expressed affect based on the platform’s affordances, we coded whether and how often the tweets had been retweeted and “liked.” We also recorded if, how many and what @-mentions, hashtags, and emojis the tweet contained, if it shared a hyperlink, an image, or included an expressive use of punctuation (e.g., “!!!”).

Ethical considerations

Doing research on Twitter data poses real ethical considerations. First, informed consent is nearly impossible to achieve with large Twitter data sets (Libby Bishop Citation2017). Twitter users must accept the site’s terms of service, which state that data may be used by third parties, including scholars (Social Data Science Lab Citation2016); however, their acceptance does not mean that they are necessarily aware of this requirement or agree to it. Furthermore, although Twitter users share their tweets on a forum that is public, research shows that it often feels private to users (danah Boyd and Kate Crawford Citation2012). To protect our respondents’ privacy, we do not quote longer passages nor include usernames, thereby making it impossible to identify participants through a search (Social Data Science Lab Citation2016). We also removed tweets from the sample that were no longer available at the time of analysis.

Results

Emotions in the #MeToo movement

When applying Plutchik’s model, we found that a third of tweets (181) included an emotional dimension. Within these 181 tweets, we coded 208 different types of basic and dyad emotions. The majority (86%) of these tweets expressed one type of emotion, 14% expressed two, and only one tweet had three types. Despite Twitter’s character limit of 140 at the time of data collection, the presence of emotion in a third of the tweets corroborates past findings on how users employ text combined with emojis, acronyms, shortenings, and many other symbols to express a wide range of emotions (Arnout B. Boot, Arnout B. Boot, et al. Citation2019). Yet, many users only expressed one emotion, most likely a result of the system’s character constraint.

Basic emotions in #MeToo

By far, the most expressed emotion was sadness, with 45 occurrences (). The tweets mostly expressed sadness about the scale of sexual violence and how it has affected so many people, often women. Sadness was also expressed about the secrecy and shame that surrounds the experiences and the lack of action on the part of institutions and society at large to combat sexual violence. Trust was present in 31 tweets and was mostly expressed as believing survivors’ testimonies, including of survivors who had decided not to share any details. This is an important and surprising finding, given research showing how those who disclose trauma are often disbelieved (Leigh Gilmore Citation2001) or blamed (Anderson et al. Citation2007). This made trust a strong emotion in the corpus, as it extended the affective solidarity of the #MeToo movement to all survivors, suggesting that this is a safe space, even for those who found participating difficult.

Eighteen tweets were coded for anger, which was expressed both in text and via emojis. We expand past research that has documented anger in digital feminist research by highlighting how it was often targeted: at perpetrators and their manipulative tactics; at rape myths that perpetuated and circulated falsehoods; at public figures or celebrities who were not held accountable for their words or actions; and at the online misogyny that digital feminist movements had to deal with. Fear, present in 16 tweets, came from survivor experiences that were traumatic and the potential repercussions resulting from having shared their survivor stories online. Disgust, coded in 13 tweets, was expressed as a direct reaction to the stories survivors shared of sexual violence and harassment through #MeToo. Disgust was also expressed in relation to misogynistic behaviours prevalent in society, such as catcalling, unwanted sexual attention, and inappropriate comments. Nine tweets were coded as surprise, coded here as a negative emotion, and expressed because of the scale of sexual violence as documented through survivor tweets. Joy and anticipation were present in 3 and 1 tweets, respectively, as would be expected considering the nature of #MeToo.

We also examined the intensity of each of the eight basic emotions, rating each on a scale from 1 = least intense to 3 = most intense. The intensity of emotions was not directly associated with their occurrence in the corpus. Sadness (1.9), which was the most common emotion, did not have the greatest intensity. We found that trust (2.2) and surprise (2.4) showed the strongest emotional intensity, corresponding to admiration and amazement directed at sexual violence survivors who had shared their stories online and affirming affective solidarity. Another emotion with high intensity was disgust (2.0), indicating a sense of loathing towards sexual violence perpetrators. The nuances of emotional expression in #MeToo can be observed through the intensity of emotions conveyed.

Emotional dyads

To further examine the nuances in emotions expressed in #MeToo, we looked at emotional dyads. Emotional dyads were present in 70 tweets, with love (29 tweets) being the most frequent, followed by disapproval (19 tweets), optimism (9 tweets), contempt (8 tweets), and remorse (7 tweets). Users expressed love toward survivors, often using the heart emoji. The heart emoji served as a strong symbol of affective solidarity and allowed users to reach out to others and provide emotional support. Also, love which combines the basic emotions of trust and joy, serves to further validate survivors’ stories. Disapproval targeted larger societal norms that protect perpetrators, with one tweet directly calling out specific harmful beliefs by using hashtags such as #boyswillbeboys and #Ididnotmeanto. In this case, hashtags served to identify larger problems in society that needed to be addressed.

In the next section, we use the concept of vernacular practice to show how, through common grammars and conventions, #MeToo became an “affective public” (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015). We show how four “grammars of speech” emerge as affective and powerful conventions that propelled #MeToo to a global phenomenon.

Vernacular practices in the #MeToo movement

Signalling participation without disclosing personal experience

As one might expect, given that Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet called for women to write “me too” if they had been sexually harassed or assaulted, the disclosure of personal experience of sexual assault was the most common theme in our data (32% of the tweets). However, tweets with the #MeToo hashtag had a much broader scope. Most notably, we found that many users expressed support of and solidarity with sexual assault survivors, raised awareness of sexual violence, challenged rape culture, demanded justice and social change, and called for more participants to join. These tweets conveyed affect through various features, rhetorical devices, and strategies including, but also going beyond the use of emotion.

Many tweets expressed support for survivors of sexual violence by stating that they stood with victims, “had their backs,” and believed them. Although we could not code emotion in many of these tweets, an affective sense of solidarity never-the-less underpinned these. In some cases, users further strengthened these affective intensities through Twitter’s affordances, including the use of emojis, particularly heart emojis, which, when duplicated in a row, signalled the intensity of their support. The notion of “believing survivors” was also strongly represented in the tweets, challenging gendered stereotypes, which assume that women lie about sexual assault (Diana L. Payne, Kimberly A. Lonsway and Louise F. Fitzgerald Citation1999) and creating a safe space for survivors. Many Twitter users also expressed support for survivors who did not disclose their experiences on social media, with tweets emphasizing that survivors had no obligation to share and didn’t “owe” their stories to anyone. Such tweets generated a sense that, although #MeToo was a safe space for survivors, no one would be pressured to come forward unless ready. Here, sad face emojis were sometimes used to reinforce feelings or a sense of sadness.

One common form of participation was to criticize the broad phenomenon of “rape culture.” Widely theorized amongst feminist scholars, rape culture is a set of cultural beliefs that encourages male sexual aggression and condones sexual violence against women as natural (Emilie Buchwald, Pamela. R. Fletcher and Martha Roth Citation1993). These tweets highlighted the normalization of sexual aggression against women and challenged the notion that survivors are to blame for their experiences. Interestingly, although rape culture was often critiqued, most of these tweets were coded as being without any discernible emotion. Many were simply matter of fact about the prevalence or rape culture and the need to dismantle it. Although many of these lacked an identifiable emotion, they were nevertheless still powerful, affective, and moving, evidenced through likes and retweets.

Numerous tweets also included calls for justice and social change, with users demanding for systemic gendered violence to stop. Several called out politicians, particularly Donald Trump and Betsy DeVos, whom they considered complicit in perpetuating patriarchal notions of sexual violence. Such tweets were often accompanied by multiple exclamation marks and use of rhetorical questions, which signalled emotions such as anger. Finally, many users called for more participation in the #MeToo hashtag by encouraging survivors to speak out and “spread the message”–suggesting an almost evangelical tone. Altogether, most tweets did not involve personal disclosures about experiencing violence. Instead, they contributed to #MeToo as an affective public by expressing support, encouraging survivors, and challenging the culture that protects perpetrators. And it is significant that this affective public was created not simply through the use of emotive language (although this was at times evident), but through the “grammars” of #MeToo, including statements of solidarity, belief in survivors’ accounts, and acknowledgment of a broader rape culture, which is so often denied.

Not identifying perpetrators

Naming perpetrators of sexual violence on social media platforms is not a new practice and is believed to help victims gain a sense of justice over their experience (Anastasia Powell Citation2015; Bianca Fileborn Citation2016). Although some #MeToo scholars have found that providing information about the perpetrator is often a prioritized component in disclosures (Katherine W. Bogen, Katherine W. Bogen, et al. Citation2019), our dataset showed that naming and shaming was notable in its absence. Instead, we did not find any Twitter users naming perpetrators by naming, tagging, or @-mentioning them in disclosures of sexual harassment or assault. As such, not (directly) identifying perpetrators was a common vernacular practice in our sample, wherein a sense of shame or fear of reprisals are observed, from dropping hints while hiding details about the perpetrator.

Although users did not name perpetrators, some disclosures included hints about the perpetrator, including their gender, age, race, occupation, and sometimes their relationship to the survivor. For instance, some hints, such as “ex-boyfriend” and “grandfather,” targeted an individual who was close to the survivor and may be recognized by other readers in their Twitter network. But more often, disclosures provided vague hints, making it virtually impossible to identify perpetrators. Some disclosures also provided relationships between the survivor and perpetrator, such as classmate, neighbour, colleague, or stranger. There were also posts mentioning the occupation and title of the perpetrator, such as professor, teacher, and priest, indicating their background or professional status–particularly those in positions of trust. These hints allow users to project a feeling of “vague belonging” through identifying the sameness of experiences of victimization while reducing the cost of disclosure that could be hard to manage offline (Lauren Berlant Citation2008). These hints used in disclosures of traumatic experiences often do not contain emotional words, but the practice of “hinting” or refraining from naming could be read as affective, which is usually associated with the specific relationship between survivors and perpetrators, such as the fear of disclosing misconduct by perpetrators at the higher level of an unequal power relationship, the self-denial, guilt, and a shattering of beliefs after experiencing sexual assault conducted by someone who are thought to be trusted, as well as the sadness as a common residual affect of experiencing sexual assault. We also noticed that the gender pronoun “he” was often the most common hint provided and was often capitalized. For example, one user wrote that the incident does not define themselves as a victim; instead, “it defines who HE is.” Although not conveying explicit emotions, the capitalized form contributes to adding “affective intensities” by generating a sense of healing and resilience to the affect palette of the narrative (Jessica Ringrose and Emma Renold Citation2014).

Altogether, the absence of clear information about perpetrators in our dataset suggests that, for many survivors, they are not making use of Twitter as a place to seek formal justice through public “naming and shaming” (Anastasia Powell Citation2015). Rather, survivors’ disclosure on Twitter appears more like seeking validation of their experiences of victimization while collaboratively evidencing the prevalence and magnitude of sexual violence. Through providing various hints in their testimonies, survivors collaboratively delineated a blurry profile of the perpetrator, but one that could easily resonate with and become “sticky” to readers (Ahmed Citation2004; Inger-Lise Kalviknes Bore, Anne Graefer and Allaina Kilby Citation2018), enabling public acknowledgement for what happened and generating cascading disclosures of others.

Speaking to the void

#MeToo is part of what is often referred to as hashtag activism, which “happens when large numbers of postings appear on social media under a common hashtagged word, phrase or sentence with a social or political claim” (Guobin Yang Citation2016, 13). The advantage of hashtag activism for #MeToo is that it allows survivors to join a movement without having to direct their story to any one person. We found that survivors recounted experiences in general terms without having a specific audience in mind. As such, in speaking to the void, #MeToo participants were addressing no one, and everyone. At times, tweets felt like introspections, which acknowledged how they “finally understood” the scale of the problem; felt “scared” by the sheer volume of testimonies, or no longer felt alone. In many cases, these intimate disclosures emulate previous practices of writing diaries to document, vent, share and reflect experiences of sexual violence without the risk of being judged or isolated (Gilmore 2011). This practice translates into the digital space when through #MeToo, rather than targeting a specific audience, their testimony sits in a semi-private space–with no real knowledge–and perhaps both hope and dread of who will see it. The space is private and intimate because of the sheer volume of tweets linked to #MeToo, as well as through the careful disclosure practices. At the same time, the disclosure is public, as tweets weave together in creating a powerful testimony that collectively, and affectively, expresses the scale of the problem and the need to raise awareness and change.

Use of euphemisms

As previous scholars have demonstrated (Mendes et al. Citation2019a), a common vernacular practice amongst feminist hashtags that call out sexual violence was the ways euphemisms–rather than direct and precise language–are used to articulate experiences of sexual violence. Therefore, instead of using words such as “rape,” “abuse” or “assault” to describe personal experiences, readers were left to “‘read into’ the meaning of these experiences” (Mendes et al. Citation2019a, 1302) via the narratives, hashtags, emojis, ellipses, and other cues such as exclamation marks or capitalised letters. Within this dataset, some referred to their experience of violence using relatively neutral language such as “it,” or “my story.” But in most cases, more affectively charged words such as “abused,” “victimized,” “molested,” or “assaulted” were used–terms which indicate violence, but which do not go into detailed “incident accounts” (Keith V. Bletzer and Mary P. Koss Citation2004) of specific sexual acts. When looking at the ways affect was imbued within the vernacular practice of using euphemisms, it became evident the ways many used their tweet not only to allude to their abuse but the impact it had on them. Several such tweets contained statements such as “I’ll never forget,” “it feels so shitty,” or “I always think it was my fault,” which convey feelings of sadness, regret, blame, and self-loathing. In several cases, sad face or heartbreak emojis were used to increase “the intensity of affect” (A. Riordan Monica Citation2017, 552), guiding readers to interpret their experience as harrowing, harmful, and painful. A handful of tweets were more hopeful, using heart emojis to indicate healing, recovery, and a shift from victim to survivor.

Indeed, out of all the vernacular practices identified, euphemistic tweets were the ones in which emotions–notably sadness–were most palpable. This was achieved by making use of the various features of Twitter.

Discussion

This study adds to the growing research on digital feminism and hashtag activism by highlighting the role of affect and emotion in #MeToo. Through applying Robert Plutchik’s (Citation2000) structural model of emotion, we were able to identify a wider range of emotions evident in feminist hashtag campaigns than has previously been identified, such as love and trust. Our analysis, which incorporated emotional dyads, also showed how emotions expressed were more nuanced than previous scholars had identified. Given previous scholarship which highlighted the importance of emotion in generating affect (Ahmed Citation2014; Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015), we were surprised that only 32% of our sample contained discernible emotions. As we argued above, this absence of emotional expression in most of the tweets might stem from Twitter’s character limit; it might also reflect the difficulty of putting traumatic experiences into writing (Cathy Cathy Caruth Citation1995; A. Riordan Monica Citation2017). Our finding that sadness, trust, anger, fear, and disgust dominate the tweets is consistent with previous research that revealed a negative tone in digital feminist campaigns (Mendes et al. Citation2019a; Schneider et al. Citation2019), although it also indicates that negative emotions are multifaceted, directed at different targets, and can serve as a conduit for solidarity, validation of other’s experiences, and shared healing. Robert Plutchik’s (Citation2000) structural model of emotional expression proved valuable because its emotional dyads added important nuance to our analysis. Mostly the dyads love and disapproval frequently appeared in our corpus, highlighting the complex emotional experiences of #MeToo users that models focused on basic emotions only are unable to capture.

Perhaps most importantly, we concluded that affect in #MeToo can travel through means other than the explicit linguistic expression of emotions, with the scale of mediated responses highlighting the power of affect in moving people towards participating in the hashtag. Drawing on Gibbs et al.’s (Citation2015) notion of platform vernaculars, we argued that #MeToo spawned an “affective public” (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015) through the emergence of four “grammars.” We identified that #MeToo users lent affective solidarity to survivors through expressions of support, validation of their accounts, and acknowledgment of the systematic nature of sexual violence. Those who spoke of events in their own lives tended to do so in euphemisms and in ways that centred their experiences, their relationships with perpetrators, and their processing of what had happened. Rather than being accusatory or “naming and shaming” an assailant, these accounts were often introspective and reminiscent of diary writing which, amplified through the scale of the movement and Twitter’s publicness, forms a powerful testimony that is both affective and political. As previously highlighted, the practice of diary writing for processing sexual violence is long-established (Gilmore 2011). To complement the growing research on feminist blogging about sexual violence (Mendes et al. Citation2019a), it is worth investigating further how social media like Twitter are conducive to diary writing practices, how they shape them, and how they enable personal accounts to appear as part of pervasive social phenomena. As Hester Baer Citation2016 has argued: “By emphasizing the way individual stories of oppression, when compiled under one hashtag, demonstrate collective experiences of structural inequality, hashtag feminism highlights the interplay of the individual and the collective” (29).

Our findings stress that affect evolves beyond emotion in #MeToo. Although some researchers have used the concepts interchangeably, we found that affect and emotion had different functions in our data. Verbalized emotions in #MeToo could be read as conscious articulations of outrage and markers of solidarity with sexual assault survivors. Affect–being an abstract and unformed “intensity” and thus harder to capture verbally–mainly appeared to move people to participate, lending further support to previous research that highlights the role of affect in mobilizing and driving participation (Mendes et al. Citation2019a). There were several ways in which users of the #MeToo hashtag expressed something in their tweets even when that something was often highly unspecific or when explicit comments on lived experiences and perpetrators remained absent. This observation resonates with the study by McLean et al. (Citation2019), which found that emotion appeared in tweets and posts, whereas affect seemed to mainly drive activity. We conclude that the abstract character of affect was instrumental in driving participation of the hashtag and thus formed an affective public on Twitter (Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015).

Applying the framework of platform vernacular was fruitful for identifying a range of practices that express emotion and affect without words. Participants made full use of the possibilities of Twitter to convey affect within the dominant “grammar” of #MeToo by showing emotions not just through words but also through for example emojis, ellipses, punctuation, capitalization, and bolding. Our findings suggest that there is value in studying the role of social media affordances in expressing shared affect that connects users in affective publics.

While optimistic that our data sheds light on how affect travels in and through Twitter, we are aware of the study’s limitations. This includes the fact the tweets are only in English and are likely to present a North American and European bias. Our data set may also overrepresent affective responses because data were collected in the first 24 hours after #MeToo went viral. Because of our research questions, we intentionally focused on this time frame to capture the unique reactions, emotions, and affect that characterized the early hours of #MeToo. Yet, it is worth asking if and how these responses changed over time as social media users processed the events. As Zizi Papacharissi (Citation2015) suggests, affective publics leave distinct digital “footprints” (312), with each public showing unique communication patterns and developments. The digital footprint of #MeToo as an affective public remains to be traced in future research over time and across social media services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charlotte Nau

Charlotte Na is a doctoral student in Media Studies at the Faculty of Information and Media Studies at Western University. Her research concentrates on social media-based activism and feminism. Charlotte Nau received an M.A. in Communication from the University of Memphis, U.S., and holds a Magister Artium in Mass Communication from Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany. Her past research concentrates on gender in political communication. Her research appears in New Media and Society, the Journal of Language and Social Psychology, and the Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict.

Jinman Zhang

Jinman Zhan is a doctoral student in Media Studies at Western University, Canada. Her research interests centre on the intersections of affect, emotion, and digital feminist activism. Jinman Zhang obtained an M.A. in Digital Humanities from the University of Alberta, Canada, and an M.A. in Journalism from Communication University in China.

Anabel Quan-Haase

Dr. Anabel Quan-Haaseis a Full Professor of Sociology and Information and Media Studies at Western University and Rogers Chair in Studies in Journalism and New Information Technology. Her work focuses on social change, social media, and social networks. She is the coeditor of the Handbook of Social Media Research Methods (Sage, 2017), coauthor of Real-Life Sociology (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed, 2020), author of Technology and Society (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2020), and coeditor of the Handbook of Computational Social Science (Routledge, 2021). Dr. Quan-Haase is past chair of the Communication, Information Technology, and Media Sociology section of the American Sociological Association and past president of the Canadian Association for Information Science. Through her policy work she has cooperated with the Benton Foundation, Partnership for Progress on the Digital Divide, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and Canada’s Digital Policy Forum. Dr. Quan-Haase is also a frequent expert commentator and resource for mass media outlets including The Globe and Mail, CBC, Vice, CTV, Global News, Financial Post, The Huffington Post, and many others.

Kaitlynn Mendes

Dr. Kaitlynn Mendes is Associate Professor of Sociology at Western University, Canada. Her work sits at the intersections of media, sociology, education and cultural studies, and she has written widely around representations of feminism in the media, and feminists’ use of social media to challenge rape culture. Interested in the everyday experiences of using digital technologies to speak about feminist issues, she has written about the #MeToo movement and other relevant feminist campaigns. She is author of over 50 publications, including the award winning SlutWalk: Feminism, activism and media (Palgrave, 2015); Feminism in the News (Palgrave, 2011); and Digital Feminist Activism: Girls and Women Fight Back Against Rape Culture (Oxford University Press, 2019). More recently, she has been investigating sexual violence in school settings, and mobilizing her research findings to create impactful resources for schools, parents, and young people.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press.

- Anderson, Irina, and Kathy Doherty. 2007. Accounting for Rape: Psychology, Feminism and Discourse Analysis in the Study of Sexual Violence. New York: Routledge.

- Azhar, Hamdan 2017. “Tweets with Emojis—#MeToo” (Dataset).” data.world. Accessed 1 June 2020. https://data.world/hamdan/tweets-with-emojis-metoo-2017-10-16

- Baer, Hester. 2016. “Redoing Feminism: Digital Activism, Body Politics, and Neoliberalism.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1080/14680777.2015.1093070.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2008. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bishop, Libby. 2017. Big Data and Data Sharing: Ethical Issues. UK Data Service. https://ukdataservice.ac.uk/media/604711/big-data-and-data-sharing_ethical-issues.pdf

- Bletzer, Keith V., and Mary P. Koss. 2004. “Narrative Constructions of Sexual Violence as Told by Female Rape Survivors in Three Populations of the Southwestern United States: Scripts of Coercion, Scripts of Consent.” Medical Anthropology 23 (2): 113–156. doi:10.1080/01459740490448911.

- Bogen, Katherine W., Kaitlyn K. Bleiweiss, Nykia R. Leach, and Lindsay M. Orchowski. 2019. “#metoo: Disclosure and Response to Sexual Victimization on Twitter.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence. advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0886260519851211.

- Boot, Arnout B., Erik Tjong Kim Sang, Katinka Dijkstra, and Rolf A. Zwaan. 2019. “How Character Limit Affects Language Usage in Tweets.” Palgrave Commun 5 (76): 1–13. doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0280-3.

- Bore, Inger-Lise Kalviknes, Anne Graefer, and Allaina Kilby. 2018. “This Pussy Grabs Back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest.” Open Cultural Studies 1 (1): 529–540. doi:10.1515/culture-2017-0050.

- Boyd, danah, and Kate Crawford. 2012. “Critical Questions for Big Data.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 662–679. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

- Brennan, Teresa. 2004. The Transmission of Affect. Ithica, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Brown, Dalvin 2018. “19 Million Tweets Later: A Look at #metoo A Year after the Hashtag Wen Viral.” USA Today, October 13. Accessed 12 May 2021. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/10/13/metoo-impact-hashtag-made-online/1633570002/

- Buchwald, Emilie, Pamela. R. Fletcher, and Martha Roth. 1993. Transforming a Rape Culture. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

- Caruth, Cathy. 1995. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- CBS News. 2017. “More than 12m ‘Me Too’ Facebook Posts, Comments, Reactions in 24 Hours.” CBS News, October 17. Accessed 20 November 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/metoo-more-than-12-million-facebook-posts-comments-reactions-24-hours/

- Clark-Parsons, Rosemary. 2019. “‘I SEE YOU, I BELIEVE YOU, I STAND WITH YOU’: #metoo and the Performance of Networked Feminist Visibility.” Feminist Media Studies 19 (8): 1063–1078. doi:10.1080/14680777.2019.1628797. advance online publication.

- Daniel, Thomas, and Alecka Camp. 2020. “Emojis Affect Processing Fluency on Social Media.” Psychology of Popular Media 9 (2): 208–213. doi:10.1037/ppm0000219.

- Fileborn, Bianca. 2016. Reclaiming the Night Time Economy: Unwanted Sexual Attention in Pubs and Clubs. New York: Springer.

- Gibbs, Martin, Meese, James, Arnold, Michael, Nansen, Bjorn, and Carter, Marcus. 2015. ”#Funeral and Instagram: death, social media, and platform vernacular.” Information, Communication & Society 18(3): 255–268

- Gilmore, Leigh. 2001. The Limits of Autobiography: Trauma and Testimony. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hemmings, Clare. 2012. “Affective Solidarity: Feminist Reflexivity and Political Transformation.” Feminist Theory 13 (2): 147–161. doi:10.1177/1464700112442643.

- Jasper, James. 1997. The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography and Creativity in Social Movements. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press

- Linabary, Jasmine R, Danielle J. Corple, and Cheryl Cooky. 2020. “Feminist Activism in Digital Space: Postfeminist Contradictions in #whyistayed.” New Media & Society 22 (10): 1827–1848. doi:10.1177/1461444819884635.

- Lokot, Tetyana. 2018. “#iamnotafraidtosayit: Stories of Sexual Violence as Everyday Political Speech on Facebook.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (6): 802–817. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1430161.

- Loney-Howes, Rachel, Kaitlynn Mendes, Diana Fernández Romero, Bianca Fileborn, and Sonia Núñez Puente. 2021. “Digital Footprints of #metoo.”Feminist Media Studies 1–18. advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14680777.2021.1886142.

- Massumi, Brian. 2003. “Navigating Movements: An Interview with Brian Massumi.” In Hope: New Philosophies for Change, edited by Mary Zournazi, 210–242. New York: Routledge.

- McCammon, Muira. 2020. “Tweeted, Deleted.”New Media & Society 146144482093403. advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1461444820934034.

- McDuffie, Kristi, and Melissa Ames. 2021. “Archiving Affect and Activism: Hashtag Feminism and Structures of Feeling in Women’s March Tweets.” First Monday 26 (2). doi:10.5210/fm.v26i2.10317.

- McLean, Jessica, Sophia Maalsen, and Sarah Prebble. 2019. “A Feminist Perspective on Digital Geographies: Activism, Affect and Emotion, and Gendered Human-Technology Relations in Australia.” Gender, Place & Culture 26 (5): 740–761. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555146.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessalynn Keller, and Jessica Ringrose. 2019a. “Digitized Narratives of Sexual Violence: Making Sexual Violence Felt and Known through Digital Disclosures.” New Media & Society 21 (6): 1290–1310. doi:10.1177/1461444818820069.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, and Jessica Ringrose. 2019. “Digital Feminist Activism: #metoo and the Everyday Experiences of Challenging Rape Culture.” In #metoo and the Politics of Social Change, edited by Bianca Fileborn and Rachel Loney‐Howes, 37–51. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessica Ringrose, and Jessalynn Keller. 2019a. “#metoo and the Promise and Pitfalls of Challenging Rape Culture through Digital Activism.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 25 (2): 236–246. doi:10.1177/1350506818765318.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessica Ringrose, and Jessalynn Keller. 2019b. Digital Feminist Activism: Girls and Women Fight Back against Rape Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Katia Belisário, and Jessica Ringrose. 2019c. “Digitised Narratives of Rape: Disclosing Sexual Violence through Pain Memes.” In Rape Narratives in Motion, edited by Ulrika Andersson, Monika Edgren, Lena Karlsson, and Gabriella Nilsson, 171–197. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Murthy, Dhiraj. 2017. “The Ontology of Tweets: Mixed Methods Approaches to the Study of Twitter.” In Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan‐Haase, 559–572. London: Sage.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Payne, Diana L., Kimberly A. Lonsway, and Louise F. Fitzgerald. 1999. “Rape Myth Acceptance: Exploration of Its Structure and Its Measurement Using the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale.” Journal of Research in Personality 33 (1): 27–68. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238.

- Pedwell, Carolyn. 2012. “Economies of Empathy: Obama, Neoliberalism and Social Justice.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30 (2): 280–297. doi:10.1068/d22710.

- Plutchik, Robert. 2000. Emotions in the Practice of Psychotherapy: Clinical Implications of Affect Theories. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Powell, Anastasia. 2015. “Seeking Rape Justice: Formal and Informal Responses to Sexual Violence through Technosocial Counter-Publics.” Theoretical Criminology 19 (4): 571–588. doi:10.1177/1362480615576271.

- Quan-Haase, Anabel, Kaitlynn Mendes, Ho Dennis, Olivia Lake, Charlotte Nau, and Darryl Pieber. 2021. “Mapping #metoo: A Synthesis Review of Digital Feminist Research across Social Media Platforms.” New Media & Society 23 (6): 1700–1720. doi:10.1177/1461444820984457. advance online publication.

- Ringrose, Jessica, and Emma Renold. 2014. “F**K Rape!” Mapping Affective Intensities in a Feminist Research Assemblage.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (6): 772–780. doi:10.1177/1077800414530261.

- Riordan Monica, A. 2017. “Emojis as Tools for Emotion Work: Communicating Affect in Text Messages.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 36 (5): 549–567. doi:10.1177/0261927X17704238.

- Schneider, Kimberly T., and J. Carpenter Nathan. 2019. “Sharing #metoo on Twitter: Incidents, Coping Responses, and Social Reactions.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 39 (1): 87–100. doi:10.1108/EDI-09-2018-0161.

- Shouse, Eric. 2005. “Feeling, Emotion, Affect.” M/C Journal 8 (6). doi:10.5204/mcj.2443.

- Social Data Science Lab. 2016. “Lab Online Guide to Social Media Research Ethics.” http://socialdatalab.net/ethics-resources

- Spry, Tami. 1995. ”In the absence of word and body: hegemonic implications of ”victim” and ”survivor” in women's narratives of sexual violence.” Women and Language 18(2): 27–48

- Taylor, Chloe. 2009. The Culture of Confession from Augustine to Foucault. New York: Routledge.

- Toffoletti, Kim, and Holly Thorpe. 2020. “Bodies, Gender, and Digital Affect in Fitspiration Media.” Feminist Media Studies. advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1713841.

- Too Rising, Me. 2018. “A Visualization of the Movement.” Accessed 12 May 2020. https://metoorising.withgoogle.com/

- Twitter. 2020. “About Public and Protected Tweets.” https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/public-and-protected-tweets

- Warfield, Katie 2016. “Reblogging Someone’s Selfie Is Seen as a Really Nice Thing to Do”. Paper presented at the Association of Internet Researchers Conference, Berlin, October 5-8.

- Winderman, Emily. 2019. “Anger’s Volumes: Rhetorics of Amplification and Aggregation in #metoo.” Women’s Studies in Communication 42 (3): 327–346. doi:10.1080/07491409.2019.1632234.

- Wood Linda, A., and Heather Rennie. 1994. “Formulating Rape: The Discursive Construction of Victims and Villains.” Discourse & Society 5 (1): 125–148. doi:10.1177/0957926594005001006.

- Yang, Guobin. 2016. “Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #blacklivesmatter.” Media and Communication 4 (4): 13–17. doi:10.17645/mac.v4i4.692.

- Young, Stacey L., and Katheryn C. McGuire. 2003. ”Talking about sexual violence.” Women and Language 26 (2): 40–52