ABSTRACT

As one of the largest social media platforms, Instagram has an essential role in shaping emerging cultural values in contemporary culture. Instagram is also home to myriad digital intimate publics—one of which centers on both tackling and celebrating daily experiences of women striving for health and wellness. This paper explores the affective practices of Instagram’s wellness culture, drawing from Arlie Hochschild’s concept of “feeling rules” and from recent scholarly work on feminist sensibilities in contemporary media. The analysis suggests that, in the #womenswellness intimate public, women are encouraged to 1) be honest about their feelings, 2) be grateful even in the face of failure, 3) be kind towards themselves, and 4) be empowered and ready to take down “diet culture.” The paper concludes that the enforcement of specific feeling rules makes recent changes in gendered cultural sensibilities visible: the emotions present in #womenswellness manifest a shift from postfeminist rhetoric of confidence and “bouncing back” towards popular feminist affective formations tied to self-love, kindness and vulnerability. Still, even if the rules of feeling in contemporary feminine culture are changing, the rigorous self-governing needed to survive as a woman in neoliberal culture remains apparent in the #womenswellness data.

Introduction

In the contemporary culture, social media has an essential role in shaping and regenerating both the fast-paced circulation of trends and more lasting phenomena based on emerging lifestyles and values. As one of the largest social media platforms (Statista Citation2021), Instagram is firmly wrapped in the fast-changing rhythms of what is most recent or contemporary at any given time. For this reason, Instagram culture is proficiently apt for studying the changing affective and discursive formations in gendered cultural spaces. This paper explores the affective aspects of wellness culture on Instagram, considering especially the discursive practices connected to feeling rules (Arlie Russell Hochschild Citation1983/2012) recycled in this digital intimate public. The aim of this analysis is to find answers to the questions of, first, what feelings are most visible in the #womenswellness public of Instagram and what emotions are celebrated or instigated in this space; and second, how these affective practices intertwine with contemporary configurations of feminism in popular media.

Instagram has an extensive field of communities and content that can be illustrated through the concept of wellness. Most things related to health, well-being, nutrition, and fitness fall under the umbrella of wellness, and thousands upon thousands of Instagram content creators urge users to “be inspired” and “get motivated:” to strive for better well-being and “the good life” (see Lauran Berlant Citation2011) in their personal lives. Instagram wellness brands, influencers, and other content creators offer health-related advice presented in a personalized manner, through visual illustrations and aspirational photos most often depicting beautiful food or beautiful bodies.

Wellness, however, is more widespread in Western culture than mere social media content of the 2010s and 2020s. Wellness as a concept was first popularized in the late 1950s. “High-level wellness” was defined as “a condition of change in which the individual moves forward, climbing toward a higher potential of functioning” (Halbert Dunn Citation1959), and a distinction was made between absence of illness (objective and passive) and wellness (active and subjective). Since 2008, the wellness industry has grown twice as fast as the global economic growth (Global Wellness Institute Citation2018), and today it encapsulates all sorts of lifestyles and practices—from detox diets to educational wellness policies in multinational companies—promoting health and self-improvement strategies while promising to boost productivity (see Daniela Blei Citation2017).

Wellness can be categorized as a preventative, holistic configuration of healthiness. The wellness lifestyle is especially preoccupied with nutrition, as what you decide to “put in your body” is often thought to directly “cause” both wellness and illness. Foodstuffs in the center of wellness culture are a diverse mixture of clean food (unprocessed food considered to be as close to its natural state as possible; Stephanie Baker and Michael Walsh Citation2018), “nutraceuticals” (foods that are “more than food” but “less than pharmaceuticals;” Istvan Télessy Citation2019), and food that simply makes one feel good and nourished. From an analytic point of view, a focus on wellness food brings together various wellness topics (e.g., nutrition, fitness, and mental health are often weaved together in keeping with the holistic ethos of wellness) as well as highlights the continuous “body projects” sustained in this sphere that focus on the deeply embodied nature of wellness culture.

Wellness shares its values with healthism, which has been characterized as an ideology grounded upon middle-class life-management aiming to eliminate risks for illness through personal choices (see Ngaire Donaghue and Anne Clemitshaw Citation2012). Despite the emergence of wellness as a twenty-first century buzzword attached to a wide range of products, services, industries, and lifestyles, there exists yet relatively little research pertaining to this field of culture and media. In cultural studies, wellness has been the focus of analysis in a few articles over the years (Braun Virginia and Carruthers Sophie Citation2020; Conor Bridget Citation2021; Islam Nazrul Citation2014; O’Neill Rachel Citation2020; Tiusanen Kaisa Citation2021). Healthism’s cornerstones—personalized self-care regimes of carefully curated food fads, fitness routines, and spiritual practices (see Cristina Hanganu-Bresch Citation2019, 7)—are the foundations of wellness culture that inhabit the feminine spaces of Instagram.

As contemporary wellness culture in social media is produced and consumed predominantly by women (see O’Neill Citation2020), studying wellness calls for a feminist studies perspective, as the feeling rules circulated on these sites evolve concomitantly with wider “sensibilities” of postfeminism and popular feminism. This analysis suggests that popular feminist emotional schemas are undoubtedly present in the discourses and feeling rules of Instagram’s wellness content. A tension between compliant and resistant feminism remains unresolved here, as the feeling rules in this seemingly ethical (see Akane Kanai Citation2019) digital intimate public appear, above all, ambivalent in the face of exhaustive neoliberal modes of self-governing, bodily surveillance, and structural inequalities in contemporary society.

The emotional life of contemporary feminisms in digital media

Striving for optimal well-being fits nicely with the gendered reality of both healthism and neoliberalism. According to Christina Scharff (Citation2016), the ideal neoliberal subject is often female: a (young) woman amidst continuous self-improvement or a “project of the self” to fulfil the ideal of a responsible individual preventing ill health and striving toward an acceptable size and shape of one’s body (see Chelsea Cinquegrani and David H.K. Brown Citation2018, 586). Contemporary modes of self-governing have been widely analyzed from gendered viewpoints, and especially, the negotiations between neoliberal and feminist ideas have been an influential field in feminist scholarly work (see, e.g., Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg Citation2020).

Postfeminism (Gill Rosalind Citation2007; McRobbie Angela Citation2009) and popular feminism (Sarah Banet-Weiser Citation2018) are interrelated concepts both used in investigating the ways in which current notions of femininity and feminism incorporate, revise, and possibly attack (see Gill Citation2007) the feminist ideas of previous decades. Postfeminism is often described as a “sensibility” that emphasizes choice, “being oneself,” and “pleasing oneself” as central prerogatives to an active, self-reinventing subject (ibid.). Banet-Weiser’s, Gill, and Rottenberg (Citation2020) concept of popular feminism refers to practices related to women’s rights accessible to a broad public (e.g., commodities and hashtag activism addressing, e.g., self-confidence and body positivity) that are highly visible on social media platforms.

Popular feminism distinctly differs from postfeminism’s “disavowal of feminist politics” as it “takes up the mantle of traditional feminist issues” (Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020, 20). In fact, Laura Savolainen, Justus Uitermark and John Boy note that we are currently witnessing a reinvigorated insistence on the continued relevance of feminism, especially on social media, where affordances and practices have been adopted for feminist expression (Laura Savolainen, Justus Uitermark & John D. Boy Citation2020). In #womenswellness, popular feminism circulates as a manner of expression that prioritizes some discursive, affective, and aestheticdispositions over others. The manner of displaying feminism seems inseparable from the feminist issues scrutinized, as digital media affordances reward certain styles of depiction by granting visibility to them.

Social media spaces that circulate “women’s culture” are often characterized as intimate publics (Lauren Berlant Citation2008). According to Berlant, an intimate public is a culture of circulation of texts and things that profess to express participants’ core interests, thus producing a sense of commonality and shared history with the (assumed) participants in that space (Berlant Citation2008, 5). In her research, Kanai considers feminine Tumblr spaces as digital intimate publics: as digital spaces “operating on a fantasy of fitting into a feminine generality, offering a sense of ongoing attachment through the expression of emotional likeness” (Kanai Citation2019, 5). The affective and cultural practices of the quasi-communities devoted to women’s wellness on Instagram operate via a similar logic: the intimate public provides material that encourages “enduring, resisting, overcoming, and enjoying being an x” (Berlant Citation2008, viii), the x here being a woman striving for wellness.

According to Kanai, the circulation of texts in digital spaces constructs (and builds on) a common imaginary and on common conceptual worlds (Kanai Citation2019, 62) of real and imagined others: the reader in a digital intimate public “understands that the post articulates a feeling experienced by someone else, while also putting in the work of relating to a vaguely similar feeling on a personal level.” (61–62.) Finally, Berlant’s characterizations of an intimate public as (a) elaborating themselves through commodity culture, as well as (b) being organized by fantasies of transcending the obstacles that shape the participants’ historical condition (Berlant Citation2008, 8), are fundamental aspects of the “psychic life” of the intimate public analyzed here.

The #womenswellness digital intimate public enforces specific feeling rules that participants are encouraged to abide by. According to Hochschild, feeling rules are “standards used in emotional conversation to determine what is rightly owed in the currency of feeling” and, through them, “we tell what is ‘due’ in each relation, each role” (Hochschild Citation1983/2012, 27). Feeling rules relate to “emotional labor” (ibid.), which refers to being required to feel the “right feeling” for a situation or a job. As a concept, “feeling rules” especially applies to digital intimate publics because of the conformity and sameness it implies: the rules of feeling guide the practices and discursive dimensions of online wellness culture I analyze here.

Finally, theorizations on contemporary feminisms are particularly interested in what is considered to be a “psychological turn” (e.g., Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad Citation2018) in neoliberal (post)feminist culture. This turn and analyses concerning therapy culture both deal with the emergence of psychology as a deep cultural structure (Eva Illouz Citation2008) in contemporary Western societies. According to Illouz, therapeutic culture is a deeply internalized cultural schema organizing the perception of the self and others, in which “mental or emotional health is the primary commodity circulated” through specific language, rules, and boundaries (Illouz Citation2008, 170–171). A culture tuned to therapeutic pursuits puts emphasis on self-reflexivity and positions the subject as always “lacking” in some way and thus in need of (therapeutic) relief (Jean Collingsworth Citation2014).

Illouz notes that the therapeutic narrative makes emotions (e.g., guilt, shame, anger, and insecurity) into public objects to be exposed, and subjects participate in the public sphere through the construction and exposure of “private” emotions (Illouz Citation2007, 52). Confessional culture is considered as deeply gendered as well—as a culture that compels the private worlds of women into the public sphere (Anita Harris Citation2003). Feeling rules for Instagram’s wellness content extract behavioral and affective ideals from wider societal currents relating to therapy and feminism.

Data

The analysis began by combing through a large amount of Instagram’s health-related content to select a single hashtag (and thus a topic) as a “ground zero” for data gathering that represented Instagram’s scattered field of health-related content. The hashtag womenswellness was chosen on the grounds that it brought together various topics related to health and nutrition that are abundant in the spaces populated by women on this medium. Linnea Laestadius (Citation2017) notes that as Instagram’s affordances promote visual rather than textual communication, its hashtags are less likely to indicate posts as being part of a continuing text-based conversation, as on Twitter, and are more likely to indicate participation in a community or provide context for an image. The hashtag womenswellness was often used together with other popular hashtags (for example, holisticnutrition, hormonebalance, selflove, functionalnutrition, and healingyourself), which indicates that it is connected to various clusters of health and nutrition content on Instagram. It is worth mentioning that Instagram users within this quasi-community often attach multiple tags to posts, and many of the selected posts simultaneously remain part of other (albeit often very similar) publics not examined in this analysis.

The dataset comprises 300 publicly available Instagram posts obtained by tracking the hashtag womenswellness via Instagram’s Most Recent feature that exhibits all posts using #womenswellness in a reverse chronological order. While it would be impractical to scroll through these posts all the way to their “beginning” (the count of #womenswellness used in posts by March 2021 was over 223,000), the feature facilitates browsing posts that have been published in recent days or weeks. Three hundred was selected as the desired dataset size to produce a manageable sample consistent with a qualitative approach to understanding online meaning-making (see Kim Toffoletti and Holly Thorpe Citation2020). Posts were collected over a two-week period in seven separate instances (from August 6 to 20, 2020) until the total count of posts reached 305 (five posts were extracted as back-up).

These posts were not extracted indiscriminately. Instead, the sample was narrowed down by adhering the following criteria: (1) the language used in the post was English, and (2) the post included some reference to food (food ingredients, beverage, diet, nutrition, meals, or eating) in the post’s caption or image content. By focusing on food and nutrition, the data constitute a diverse constellation of wellness content grasping the embodied, affective, holistic, consumption-related, and aestheticas well as healthiest aspects of the #womenswellness discourse. Posts in the dataset discuss food or eating alongside a wide range of topics, including self-care, mindfulness, beauty, fitness, body size, and reproductive health.

The public nature of Instagram makes it fitting for cultural analysis. Instagram is one of the most popular platforms for self-presentation online and, as other online spaces, it encourages and discourages certain forms of social exchange, identity presentation, and affective display (Baker and Walsh Citation2018). The affordances of social media platforms play a role in how digital publics are formed. Many of Instagram’s key characteristics have to do with the interplay between intimacy and marketing: The dominance of commercial displays on Instagram has resulted in a shift from “networked intimacy” towards a “networked public” wherein users are not only sharing content for groups of friends, but instead publishing content in the persona of a public figure for an imagined, unseen audience (Tama Leaver, Tim Highfield, and Crystal Abidin Citation2020). Further, Instagram content appears to be both highly scripted and “authentic” as significant effort goes into emphasizing authenticity through content design (see e.g., Josie Reade Citation2021). The intimate public of #womenswellness weaves these aspects together in a manner typical for Instagram: through advertising and selling commodities and services while heavily utilizing realness and emotional connectivity.

Marketing and influencing are important in relation to #womenswellness content and the “agenda” of a typical poster, as a significant share of the dataset’s posts try to influence potential consumers to buy something specific (vitamin supplements, health coaching services, or feminine products, for example) or something in general (healthy vegetables or plastic-free kitchen utensils).

However, despite displaying varying motivations such as selling services, displaying one’s identity or connecting with a network of like-minded women, what binds these posts under a unified theme is the aspirational nature of #womenswellness content, as all forms of interaction and display within this public revolve around some kind of self-betterment.

Ethical considerations relating to user-generated data and republishing images shared on social media are an ongoing challenge (Toffoletti and Thorpe Citation2020). In the case of #womenswellness content, the public and especially the commercial nature of these posts has influenced how rigorously user privacy has been pursued (see Leanne Townsend and Claire Wallace Citation2016 on expectation of privacy and on vulnerability online). However, as a way of ensuring ethical procedure, user identifiers have been excluded from cited data excerpts, and screenshots containing visual material have been altered to conceal identifiers in an effort to lessen the likelihood of used material being traced back to a specific account.

Analyzing the affective-discursive media

Despite academic differences in the understandings of emotion, affect, and materiality and the adequacy of the discourse-centrality of previous poststructuralist scholarly work (e.g., Margaret Wetherell Citation2012), what is widely accepted in the study of affect is that affect is emotion in the midst of some sort of in-between-ness (Melissa Seigworth and gregory Gregg Citation2010). According to Lauren Berlant (Citation2011, 16), affect has the potential to “move across persons and worlds, play out in lived time, and energize attachments,” whereas Megan Boler and Elizabeth Davis (Citation2018) suggest that affect is emotion “on the move.” Additionally, feelings are social: they arise and are negotiated in an inter-subjective moment (Wetherell Citation2012). Hence, cultural studies’ approaches to emotion understand affects as deeply embedded in the public sphere (Anna Berg et al. Citation2019).

Finally, affect is structured, positioning us in relationships of control, attachment, or commonality in relation to others (Kanai Citation2019, 13), and this structure is often what makes affect powerful (Wetherell Citation2012, 19): even though affect is often described as dynamic and mobile, it displays strong pushes for pattern, as particular kinds of emotional subjects are repetitively materialized, and “affective machines” emerge in social life (ibid., 13, 14). For the purposes of this study, I use the terms affect, feeling, and emotion interchangeably (similarly to Kanai Citation2019; Sara Ahmed Citation2004; Wetherell Citation2012), as their subtle differences are of minor consequence in the analysis of feeling rules on social media.

This analysis utilizes both Wetherell’s notion of affective practice (Wetherell Citation2012) and Hochschild’s concept of feeling rules (Hochschild Citation1983/2012), which is used here both as a theoretical concept and a methodological device. The concept of affective practice focuses on the emotional as it appears in social life, and it tries to follow what participants do by avoiding too-rigid or “neat” figurations of emotional categories (Wetherell Citation2012). As in Hochschild’s notion of feeling rules, affective practice emphasizes that feelings are not “inside” us as private emotions, but rather, feeling is a communicative practice that determines the rules and limits of sociability. Affective-discursive practice (Wetherell Citation2012) relies on repeating and solidifying specific affective responses and feeling rules to specific circumstances. According to Kanai (Citation2019, 14), conceptualizing affect as entangled within discursive meaning offers a pragmatic approach to analyzing textual artefacts that are created within digital social spaces.

The initial analysis of wellness content on Instagram relied on an open-coding process in which all elements of the #womenswellness posts (images, captions, contextual information, and comments) were considered for further analysis. This process provided a general feel for the dataset and aimed at identifying central patterns across the material, looking to see how these tendencies (affective intensities, aestheticpractices, tropes) intersected with previous research into social media and affect.

Next, the data were more purposefully coded by creating an emotion-bound vocabulary (see Ahmed Citation2004) in a data-driven manner (i.e., creating a vocabulary within this specific dataset). This was done in order to map the affective dynamics at play. Instagram posts were coded depending on the emotion words they contained (e.g., individual words like anxiety, beloved, confidence, disconnection, exhausted, and gratitude; phrases such as feeling out of control and learn to love yourself; and idioms such as be present in the moment and protect your boundaries). The phrases were then cross-categorized in thematical groups depending on their affective-discursive tone. These thematical groups (named self; relationship; emotional competence; restrictive feeling; untamed emotions; endurance; evolving; getting there; and in a good place) functioned as a structuring technique in ascertaining what kind of relationships between subjectivity and emotion were at play in #womenswellness data.

The final in-depth analysis aimed at recognizing distinct feeling rules (i.e., affective-discursive constellations of what emotion is encouraged or rejected in any given context), how these feeling rules relate to each other, and how they interconnect with wider cultural tendencies. These “bodies” of affective-discursive practice are introduced in the sections that follow.

Feeling honest

The #womenswellness intimate public both enables and requires sharing, as maintaining a digital affective space is founded upon open divulgement of feelings. Feeling is the essential fuel that enables these publics to operate, and in #womenswellness data, the content creators lead the way into this affective atmosphere: they themselves practice sharing and confessing so that others can ease into this mindset as well. Content creators open up a space for openness by stating, for example, that they “have a little confession to make,” or that they are “not gonna lie.” There exists a wide variety of what exactly can be confessed: content creators confess, for example, gaining weight, not caring about gaining weight, caring too much about gaining weight, or not exercising self-care, and readers are urged to confess (to themselves) that they hate their bodies, that they are not “doing the work,” or that they are not listening to their bodies well enough.

Here, sharing is a powerful tool for establishing and guarding feeling rules, as confession and the repenting that often follows strengthens the hold a particular practice has over a community. Honesty, especially, is an effective device for sociability, as confessing some less-than-ideal traits caters to relatability. A content creator emphasizing rest and recovery encourages readers to abide by an explicit affective rule:

BE HONEST. How many hours of sleep do you get a night?Footnote1

With the value put on honesty, negative emotions are being unmasked, as being honest about positive feelings can hardly be considered authentic in the same sense as sharing feelings of anger, despair, sadness or, most often, failure, like these two content creators (a wellness coach and a fashion stylist) confess in their posts:

I had let the busyness of life stop me from looking after myself the way I wanted.I wasn’t exercising as much as I wanted or used to.I wasn’t eating as well as I wanted or used to.

I’ve been struggling during quarantine too. […]I’ve gained a few pounds. […]I’m not gonna lie: my mind tells me to get in high gear to diet and go back to my past weight. But I can’t fight myself anymore. I’m tired.

The failures shared in #womenswellness are commonly associated with situations where a desired self-improvement does not align with the realities of life and thus leads to feelings of inadequacy. As well as being honest about poor lifestyle choices and relapses, an important part of this confessional behavior is being honest about feelings. Often the hardest thing to “admit” is not feeling good about yourself, or not loving yourself enough, as in this excerpt from a poster wearing a “self-love” shirt in her photo:

See those words on my shirt? I strive to grow into unconditional self love every day, which is something that I have struggled with a lot of my life, especially through my anxiety and depression journey. ![]()

Disappointment with oneself is directed both at one’s ability to do the right things and to feel the right feelings, be happy enough, be grateful enough, and be merciful enough to oneself. These tendencies seem happily mixed together, and disappointment is often attested to both failing to live well and failing to feel the right feelings:

I know what it’s like to feel NO motivation to work out ![]() […]

[…]

Once again you beat yourself up telling yourself, I’ll never have that confidence in my own body ![]() […]

[…]

And on days where I didn’t feel motivated I’d blame MYSELF. ![]()

Ugh [name] you just can’t STAY motivated, you’re FAILING ![]()

Studies on postfeminism, popular feminism, and the culture of confidence (e.g., Banet-Weiser Citation2018; Gill Citation2007; Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad Citation2015) emphasize how contemporary positive attention economies have no room for negativity: in these environments, negative affect is rebuffed, and positivity is established as the preferred emotional tone. However, (Rachel Berryman and Kavka Citation2018, 87, 90) analysis on crying vlogs on YouTube indicates that affective flows on social media are becoming qualitatively variable, and that negative affect as well can generate authenticity and thus desirable attention in social media (see also Mari Lehto (Citation2020) on mommy bloggers displaying negative feelings in order to combat the exhausting realities of contemporary parenting). Negative affect is both emancipated and policed in #womenswellness content, as certain emotions are simultaneously strongly encouraged (e.g., it is okay to feel sad) and their validity is questioned (your feelings are not authentic but “rooted in fear,” for example) resulting in an emotional atmosphere marked by ambivalence.

Many previously shunned emotions are emphasized in #womenswellness due to their authentic value. For example, shame is a particularly powerful authentic affect in this space, and thus performed and conjured up in situations where none is present, and feeling shame or guilt is assumed for the therapeutic script to create a stronger emotional echo, as in this post where a dietitian attempts to decipher how her potential future clients might be feeling:

✔ Are you sacrificing emotional/mental health because of how you eat? (feeling isolated, depressed, obsessed about food, etc.)

✔ Are you truly able to enjoy food without guilt/shame?

Confessing shame taps into the symbolic capital connected with vulnerability in the contemporary ethical media space. According to Anu Koivunen, Katariina Kyrölä, and Ingrid Ryberg (Citation2019), especially after #metoo, vulnerability and suffering injury have become paradoxically equated with power and as something that counts as shared experience in intimate publics. Being vulnerable becomes a mode of agency, and victimization is perceived as “productive” and thus suitable for the digital attention economy (ibid.). Vulnerability is useful in this discourse in creating a shared experience and an honest affective space, and as something that can be molded into resilience. For example, this Instagram dietitian reminisces on how life-altering realizations—some foods “whack your hormones out of balance”—often stem from hitting rock bottom:

You may not know this, but I used to be one of those people who couldn’t function without caffeine. […]

I started performing poorly, was unable to focus on taking care of my family and my mood was suffering.

I felt helpless, like I had no control over my life …

In their analysis of the contemporary cult(ure) of confidence directed at women and girls, Gill and Orgad (Citation2015) posit that revealing shame or insecurity is crucial, as the point is to “deal with” these feelings with the help of confidence technologies. In the wellness intimate public of Instagram, however, this would be an over-simplification, as shame or failure is often not dealt with in any decisive manner, and they almost seem to create an impasse in which feeling bad is rendered, if not desirable, at least valid and normal. As Toffoletti and Thorpe (Citation2020) argue, accepting and encouraging public expressions of vulnerability enables “a collective ownership of feelings of inadequacy” in environments where women are subject to bodily judgement. Affective authenticity is more important than appearing confident, which seems to indicate a shift in what kind of affective registers are generally legitimated in these spaces.

Feeling grateful

Many of the preferred affective practices of #womenswellness rely on high levels of emotional competence that require making oneself feel certain feelings, suppressing unwanted feelings, and “psyching oneself up” via different strategies of self-persuasion. According to Illouz (Citation2007), emotional competence is not unlike cultural competence, and is hence translatable to social capital in many situations. This is especially true in feminine and middle-class spaces, and the #womenswellness digital intimate public is indeed both. In tandem with the demand to share, the intimate public leans on myriad feeling rules that are designed to help cope in contemporary society as a woman. These affective strategies work through building up resilience: surviving, day in and day out, with the help of appropriate mental and emotional techniques.

Emotional labor is constant in #womenswellness, as the reality—of both oneself and one’s surroundings—is always lacking yet always moldable too. Emotional labor is the work that matters, since telling oneself to feel a certain way seems to be all that is required to succeed. However, on top of psyching oneself up, the actual work—losing weight, working out—needs to be done as well, which begs the question of whether resilience training is helpful at all or if it is just labor on top of labor. What is achieved via affective labor is maintaining the intimate public, since its existence requires emotional work to be put in continuously.

Resilience can be considered a necessary quality to survive in neoliberal societies defined by anxiety and uncertainty (see Gill and Orgad Citation2018). Resilience is part of the affective-discursive machine of digital gendered spaces, where sharing failures is countered with coping mechanisms to either fix that failure or to learn to accept it. Resilience training is also perceived as being feminist, as through it, women are made stronger so that they can better look after themselves (Angela McRobbie Citation2020, 39). Resilience is certainly a kind of common sense in contemporary digital spaces, where the vocabularies and affective dimensions related to resilience are utilized almost automatically (see ibid., 49).

What are your favourite ways to prevent burn out? .

Resilience manifests in different ways in #womenswellness data. What is always required, however, is emotional labor and active mental work, trying to feel the feelings you are not yet feeling:

Some of my favorite ways of getting motivated are ![]()

1 Telling myself this workout is to get stronger ![]() #strongoverskinny

#strongoverskinny

2 Picturing how I will FEEL AFTER I workout #energized #proud #accomplished […]

4 & last I will look in the mirror & tell myself “Look girlfriend no one else can show up for yourself but YOU so let’s do this!” #selfloveadvocate

One of these desired mindsets in #womenswellness is gratitude. Gratitude is considered an effective technology in tricking oneself into feeling good: being thankful conjures up positive thoughts in order to suppress negative emotions. Gratitude requires a high amount of emotional competence, since especially in the face of difficulties, people are urged to focus on the things they are grateful for, as to feel better is to be better (Sara Ahmed Citation2010, 8), and thus more resilient and more productive:

Happy and healthy—the version of me I’m working hardest to be! ![]()

An emphasis on gratitude urges people to be more adaptable and more positive (Gill and Orgad Citation2018) and to steer clear of any inappropriate feeling. The emotional ambivalence of #womenswellness is apparent here, since emphasizing gratitude works counter to the feeling rules that establish negative emotions as valid and more authentic than positive ones. Shame, failure, or anger is useful in this intimate public due to authenticity and relatability, whereas techniques of resilience—like gratitude—are useful for managing life and coping with, for example, the coronavirus pandemic, “growing pains,” and feeling overwhelmed in day-to-day life, as one fitness coach and dietitian instructs:

Let’s start this week with an “attitude of gratitude”!

Five things I’m thankful for today ![]()

Feeling kind

In #womenswellness discourse that follows the contemporary popular feminist zeitgeist, a “feministic” tone is often present, as gendered intimate publics centered on wellness value “focusing on how you feel rather than focusing on how you look” (see Toffoletti and Thorpe Citation2020, 3). A focus on feeling promotes emotion as the desirable mode of feminine self-expression and places authenticity and intimacy at the center of discourse (ibid., 3, 11).

There is an interesting difference in strategies of resilience in #womenswellness compared to resilience observed in previous studies of postfeminist or popular feminist media texts. Surpassing the usual imperative to “be confident” (e.g., Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad Citation2015, 2017) and alongside the requirement to “be grateful,” the wellness intimate public of Instagram focuses on techniques that emphasize kindness and sympathy as affective responses to situations that require resilience. This kindness is not directed toward others in a traditional fashion equating femininity with care work and accommodating other people, but toward the self. In wellness contexts, this generates a feeling rule of not requiring too much of oneself and being compassionate toward oneself, as these two Instagram coaches proclaim:

Remember, you have been criticizing yourself for years and it hasn’t worked. Try approving of yourself and see what happens. […]Yesterday I shared some habitual ways of being that commonly indicate the need for a little self-care. Today I want to share a few ways in which you can show yourself kindness.

Each time you do something for yourself, say “thank you” or “well done.” Make yourself a nice meal? Thanks (your name) Drink enough water? Well done … Go to bed a bit earlier? Well done … Respond rather than react? You get the gist.

Kindness towards oneself is portrayed as an opposite to “toxic” cultural expectations and it draws from distinctively feminist discourse. Speaking to oneself in a kind and forgiving manner could be categorized as an all-encompassing affective practice that colors the emotional tone and the technologies of the self favored in #womenswellness data.

Popular feminism itself can be categorized as “kind” rather than “angry.” Banet-Weiser (Citation2018, 14, 15) argues that popular feminism challenges the traditional stereotypical representation of angry and man-hating feminists by expressing feminist critique in a friendly, “cool,” and safe way that does not alienate any consumer groups. As far as affective tones go, #womenswellness does not entirely fit Banet-Weiser’s remark on popular feminism not encasing anger since, despite the emphasis on kindness, the discourse does work with and through anger—even if this anger is diluted in tone (see section 4.4). For example, in connection with “protecting one’s boundaries,” kindness toward the self is justified through some form of aggression toward the world that tries to break these boundaries:

![]() Say “NO” more!

Say “NO” more!

Some of the best POWERMOVES there are.Having standards.Holding boundaries.

The ambivalence of this cultural sphere is evident in its stance toward kindness, “likeability,” and anger, as there is symbolic value to be gained from both accommodation and aggression in popular feminist media. What is clear, however, is that the intimate public of #womenswellness feels ethical (see Kanai Citation2019), whether or not feminist ethics are actually abided by in reality.

We are all working towards treating our bodies with kindness and it is a PROCESS.

Beyond #womenswellness, perfect bodies are being “revealed” as inauthentic, and stretch marks, loose skin, and cellulite are exhibited in an almost fetishistic manner on Instagram in particular (see Toffoletti and Thorpe Citation2020). Imperfection connects with both visual and visceral aspects of social media as well as with the “ethical” or kind affective registers that are crucial in guiding the flows of emotion in #womenswellness.

According to McRobbie, the imperfect as a part of the “new age of feminism” offers some scope for criticism of the ideals of perfection, but within carefully demarcated boundaries (McRobbie Citation2020, 36). The focus on imperfections legitimates the presence of feminism in this discourse more than focusing on perfection ever could. However, the failures associated with imperfection are drawn with tight lines around those terrains of experience where flaws can be entertained, and the imperfect warrants further new forms of self-care and self-love—new ways in which the self can be governed in a gendered neoliberal culture (ibid., 36, 40). Through this, celebrating imperfections appears almost as a complementary discourse to perfection, creating affective intensities needed in the maintenance of feminine intimate publics.

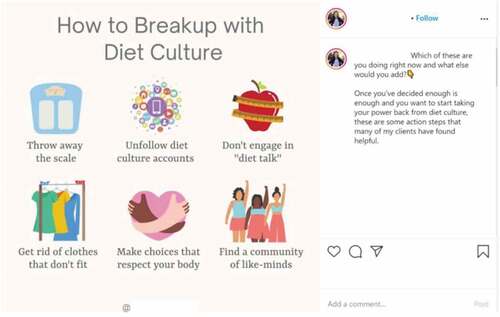

Feeling empowered and ready to take down diet culture

The drive to empower oneself and other women is remarkable in Instagram’s wellness culture, and emphasizing empowerment is intensely present in the feeling rules of this space. Unlike in feminist activism (where empowerment might be gained through advocating for minority rights, for example), empowerment in #womenswellness is self-empowerment: the goal is to reach both self-improvement and self-acceptance (“I’m learning to accept myself as I can”), no matter what you were “taught” to think about yourself and your (diet-related) failures. The word “empower” appears frequently in tags associated with women’s wellness content (#empowerher, #womenempoweringwomen), illustrating its catch-word-like status.

According to Banet-Weiser (Citation2018, 17, 21), emphasis on empowerment is not hindered by the fact that there is often little specification as to what we want to empower women to do. Popular feminist discourse restructures the politics of feminism to focus on the individual woman and urges that woman to just be empowered (ibid.). Even though “empowerment” points at the imbalanced power relations between men and women and tells women to “take back the power,” the call to empowerment often subscribes to normative femininity where aggression is mostly inner-directed (Angela McRobbie Citation2015):

I desire this to be a brand that not only creates beautiful products to support you, but also educates, informs, empowers and ultimately connects you to activating your most powerful, balanced, and aligned self every single day.

Empowerment is a matter of feeling and of believing: an affective-discursive configuration that governs women to hone in on the right kind of—resilient—mindset. Empowerment requires yet again substantial emotional competence, teaching women to “make up” the feeling they hope to feel, but do not. In #womenswellness, pursuing empowerment is upwards-striving and optimistic: exerting oneself to reach something that guarantees feeling “in control.” Empowerment is perhaps the all-encompassing goal that best sustains “cruel optimism” (Berlant Citation2011) in this public, as the good life is within our reach if we just learn to let go of the mindsets holding us back. Although perhaps, the optimistic-ness of this cruel optimism is, in the discursive universe analyzed here, lessened by a newfound suspicion that there is something else, in addition to ourselves, that stands between us and the good life, and that confidence alone might not get us there no matter how hard we try to be empowered.

One of the most prevalent targets for specific affective responses, in the data, is diet culture. Despite its ambivalence, diet culture talk in #womenswellness appears somewhat countercultural, as its declarations focus on the anti-feminist reality of weight loss in Western culture. Invoking diet culture as an object of frustration seems to give this digital space a surface on which to reflect feelings brought on by gender inequality.

This cultural space holds a shared investment in overturning the culturally endorsed assumption that (thin) bodies can be read as evidence of health, happiness, worthiness, and responsibility (see Donaghue and Clemitshaw Citation2012). This feminist manner of argumentation aims at bringing to light elements of contemporary culture that restrict women’s prospects for self-actualization and self-love. “Diet culture” is criticized because it relies on beating oneself up for not having enough self-discipline:

We’ve been so brainwashed, it’s basically hard-wired in us to think that we just don’t have enough “self-discipline” to “lose the weight,” “get to the gym,” “get healthy.” […]

Forget all the diet culture buzzwords and the fear and shame they create. Shift your mindset to simply showing your body and mind some love and respect.

But, as in the excerpt above, the only way for women to break free from the culture of dieting is by themselves: by “shifting the mindset” they are currently “trapped in,” by starting to “empower their minds,” by becoming “the leaders of their own lives,” by deciding “enough is enough,” or, as is often the case, by “clicking the link on the bio” and applying for a wellness influencer’s group program (often aiming at some kind of weight loss or body modification).

Finding peace in one’s body is possible even in a toxic culture that valorizes thinness and fitness above all else. How? Through ever more elaborate techniques of self-governing that are aimed at, first and foremost, exercising control over feelings:

![]() How many hours are you spending counting the calories in your food, stressing about what to eat, nitpicking at your body in the mirror and dreaming of a smaller/thinner/more toned body?Now imagine a life where you are content with what your current body [is] and you weren’t trying to change it. […]

How many hours are you spending counting the calories in your food, stressing about what to eat, nitpicking at your body in the mirror and dreaming of a smaller/thinner/more toned body?Now imagine a life where you are content with what your current body [is] and you weren’t trying to change it. […]

How would you feel? How would it affect your mood?

Even though contemporary culture is to blame for our problems and insecurities, in neoliberal feminist fashion, resolving this issue comes from within. According to Catherine Rottenberg (Citation2014), neoliberal feminism is concerned with instating a feminist subject who manifests self-responsibility and does not demand anything from the society. In the popular feminist affective discourse of #womenswellness, the psychic regulation entangled with gendered culture is simultaneously both rejected and complied with. Diet culture talk is noteworthy in how complex and counteracting the different feeling rules (stemming from both postfeminist confidence culture and popular feminist counterculture) appear: appropriate emotion tiptoes on the edge between up-beat positivity and inert frustration and disappointment, as the feeling subject seems unsure of whether to keep striving or to settle for what one already has. There seems to be, perhaps, a stoic quality in the ideal resilient woman: reach for something better but do not be too disappointed if (and when) you fail .

Conclusion

This analysis investigated the affective practices in Instagram’s #womenswellness digital intimate public. The aim was to ascertain what feelings were most visible in the data and if these feelings corresponded with popular feminist sensibilities. By focusing on wellness in connection with food, the analysis hoped to grasp the affective, healthist, and diet-related aspects of the #womenswellness discourse.

The analysis concluded that feeling is the essential fuel that enables the #womenwellness intimate public to operate. The affective entanglement produced through performative confession (often relating to failures) circles around “seemingly solvable but never resolved issues” (Kanai Citation2019, 55), as these issues—such as failing to be happy, grateful, or kind to oneself—enable this space to exist in the first place. What is remarkable here is how the legitimate emotions, behaviors, or subject formations present in this wellness content of 2020 do not necessarily follow the gendered discourse previously observed in analyses on postfeminist media (see Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020).

Confessing negative feelings in order to swiftly “deal with” them with the help of confidence technologies (such as “power poses,” brand-related confidence ambassadors, or insisting that “confidence is the new sexy,” see Gill and Orgad Citation2015) seems to have been partly replaced by the encouragement of public expressions of vulnerability and thus appreciation of affective authenticity. The emphasis put on resilience in previous studies (e.g., Gill and Orgad Citation2018; McRobbie Citation2020), however, has bearing in connection with #womenswellness as well; what is different is whether this resilience manifests through “being confident” and “bouncing back” or through accepting personal flaws and making the effort of being consciously “kind” to oneself. Thus, “resilience” seems to be highly resilient in itself, and changes shape in contemporary neoliberal culture with the beat of emerging and reclining cultural sensibilities. The shift apparent here is the partial displacement of post-feminism with a highly visible and popular feminism that gravitates toward played-up feminist-ness of “protecting one’s boundaries” and saying no to diet culture. Even if the rules of feeling in contemporary feminine culture may change, what remains constant is the rigorous self-governing needed to survive a woman in neoliberal culture.

As a platform, Instagram excels in weaving intimacy and authenticity to consumer practice, making it the quintessential space for therapeutic (consumer) culture. Studying affect in Instagram’s wellness content makes visible how contemporary configurations of feminism suffuse with more life-stylistic and consumerist spaces, altering the existing modes of subject formation and cultural tides of “legitimate” emotion. The #womenswellness space is certainly sparse in legitimately “resistant voices,” but if popular feminism could be categorized as being guided by cultural norms and as a complex formation where not necessarily all the forms of oppression are contested (see Anu Harju and Annamari Huovinen Citation2015), then these affective practices might have countercultural potential that affects understandings of gender in our society in a precisely popular manner.

The adoption of a popular feminist discourse might be the first step towards a more inclusive cultural field that does not rest solely on normative notions of worthiness or acceptability. Per #womenswellness data, wellness culture that has previously targeted mostly white and middle-class women (see O’Neill Citation2020; Tiusanen Citation2021) seems to have expanded its reach to “all women,” regardless of ethnicity, social status, body size or physical ability or disability. Thus, in (and as part of) the process of battling gender inequality, popular feminist discourse of wellness welcomes all of us to surrender ourselves to bodily, mental, and emotional forms of self-governing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kaisa Tiusanen

Kaisa Tiusanen is a doctoral researcher at Tampere University, Finland. Her main research interest is the critical study of cultural discourses circulating in food-related, mediated contexts.

Notes

1. In total, 24 separate posts have been quoted here.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke UP.

- Baker, Stephanie, and Michael Walsh. 2018. “‘Good Morning Fitfam’: Top Posts, Hashtags and Gender Display on Instagram.” New Media & Society 20 (12): 4553–4570. doi:10.1177/1461444818777514.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered. Durham: Duke UP.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2020. “Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation.” Feminist Theory 21 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1177/1464700119842555.

- Berg, Anna, N. Christian von Scheve, Yasemin Ural, and Robert Walter-Jochum. 2019. “Reading for Affect.” In Analyzing Affective Societies, edited by Antje Kahle, 45–62. London: Routledge.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2008. Female Complaint. Durham: Duke UP.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke UP.

- Berryman, Rachel, and Misha Kavka. 2018. “Crying on YouTube: Vlogs, Self-Exposure and the Productivity of Negative Affect.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 24 (1): 85–98. doi:10.1177/1354856517736981.

- Blei, Daniela. 2017. “The False Promises of Wellness Culture.” JSTOR Daily. Accessed 5 July 2021. https://daily.jstor.org/the-false-promises-of-wellness-culture/

- Boler, Megan, and Elizabeth Davis. 2018. “The Affective Politics of the ‘Post-Truth’ Era: Feeling Rules and Networked Subjectivity.” Emotion, Space and Society 27: 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2018.03.002.

- Braun, Virginia, and Sophie Carruthers. 2020. “Working at Self and Wellness: A Critical Analysis of Vegan Vlogs.” In Digital Food Cultures, edited by Deborah Lupton and Zeena Feldman, 82–96. London: Routledge.

- Cinquegrani, Chelsea, and David H. K. Brown. 2018. “‘Wellness’ Lifts Us Above the Food Chaos’: A Narrative Exploration of the Experiences and Conceptualisations of Orthorexia Nervosa Through Online Social Media Forums.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (5): 585–603. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2018.1464501.

- Collingsworth, Jean. 2014. “The Self-Help Book in the Therapeutic Ontosphere: A Postmodern Paradox.” Culture Unbound 6 (4): 755–771. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525.146755.

- Conor, Bridget. 2021. “‘How Goopy are You?’ Women, Goop and Cosmic Wellness.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 24 (6): 1261–1281. doi:10.1177/13675494211055735.

- Donaghue, Ngaire, and Anne Clemitshaw. 2012. “‘I’m Totally Smart and a Feminist … and Yet I Want to Be a Waif’. Exploring Ambivalence Towards the Thin Ideal Within the Fat Acceptance Movement.” Women’s Studies International Forum 35 (6): 415–425. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2012.07.005.

- Dunn, Halbert. 1959. “High-Level Wellness for Man and Society.” American Journal of Public Health 49 (6): 786–792. doi:10.2105/ajph.49.6.786.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007. “Postfeminist Media Culture. Elements of Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166. doi:10.1177/1367549407075898.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Shani Orgad. 2015. “The Confidence Cult(ure).” Australian Feminist Studies 30 (86): 324–344. doi:10.1080/08164649.2016.1148001.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Shani Orgad. 2018. “The Amazing Bounce-Backable Woman: Resilience and the Psychological Turn in Neoliberalism.” Sociological Research Online 23 (2): 477–495. doi:10.1177/1360780418769673.

- Global Wellness Institute. 2018. “Global Wellness Economy Monitor.” Accessed 14 June 2020. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/2018-global-wellness-economy-monitor/

- Hanganu-Bresch, Cristina. 2019. “Orthorexia: Eating Right in the Context of Healthism.” Medical Humanities 46 (3): 311–322. doi:10.1136/medhum-2019-011681.

- Harju, Anu, and Annamari Huovinen. 2015. “Fashionably Voluptuous: Normative Femininity and Resistant Performative Tactics in Fatshion Blogs.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (15–16): 1602–1625. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2015.1066837.

- Harris, Anita. 2003. Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Routledge.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 19832012. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Illouz, Eva. 2007. Cold Intimacies. The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Illouz, Eva. 2008. Saving the Modern Soul. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Islam, Nazrul. 2014. “New Age Orientalism: Ayurvedic ‘Wellness and Spa Culture’.” Health Sociology Review 21 (2): 220–231. doi:10.5172/hesr.2012.21.2.220.

- Kanai, Akane. 2019. Gender and Relatability in Digital Culture: Managing Affect, Intimacy and Value. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Koivunen, Anu, Katariina Kyrölä, and Ingrid Ryberg, eds. 2019. The Power of Vulnerability. Mobilising Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti- Racist Media Cultures. Manchester: Manchester UP.

- Laestadius, Linnea. 2017. ”Instagram.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Hasse, 573–592. London: Sage.

- Leaver, Tama, Tim Highfield, and Crystal Abidin. 2020. Instagram. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lehto, Mari. 2020. “Bad is the New Good: Negotiating Bad Motherhood in Finnish Mommy Blogs.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (5): 657–671. doi:10.1080/14680777.2019.1642224.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism. London: Sage.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2015. “Notes on the Perfect. Competitive Femininity in Neoliberal Times.” Australian Feminist Studies 30 (83): 3–20. doi:10.1080/08164649.2015.1011485.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2020. Feminism and the Politics of ‘Resilience’: Essays on Gender, Media and the End of Welfare. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- O’Neill, Rachel. 2020. “Pursuing ‘Wellness’: Considerations for Media Studies.” Television & New Media 21 (6): 628–634. doi:10.1177/1527476420919703.

- Reade, Josie. 2021. “Keeping It Raw on the ‘Gram: Authenticity, Relatability and Digital Intimacy in Fitness Cultures on Instagram.” New Media and Society 23 (3): 535–553. doi:10.1177/1461444819891699.

- Rottenberg, Catherine. 2014. “The Rise of Neoliberal Feminism.” Cultural Studies 28 (3): 418–437. doi:10.1080/09502386.2013.857361.

- Savolainen, Laura, Justus Uitermark, and John D. Boy. 2020. “Filtering Feminisms: Emergent Feminist Visibilities on Instagram.” New Media & Society 1–23. doi:10.1177/1461444820960074.

- Scharff, Christina. 2016. “The Psychic Life of Neoliberalism: Mapping the Contours of Entrepreneurial Subjectivity.” Theory, Culture & Society 33 (6): 107–122. doi:10.1177/0263276415590164.

- Seigworth, Melissa, and Gregory Gregg, eds. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader, 1–28. Durham: Duke UP.

- Statista. 2021. “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of April 2021.” Accessed 7 July 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

- Télessy, István G. 2019. ”Nutraceuticals.” In The Role of Functional Food Security in Global Health, edited by Ram B. Singh, Ronald Ross Watson, and Toru Takahashi, 409–421. London: Academic Press.

- Tiusanen, Kaisa. 2021. “Fulfilling the Self Through Food in Wellness Blogs: Governing the Healthy Subject.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 24 (6): 1382–1400. doi:10.1177/13675494211055734.

- Toffoletti, Kim, and Holly Thorpe. 2020. “Bodies, Gender, and Digital Affect in Fitspiration Media.” Feminist Media Studies 21 (5): 822–839. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1713841.

- Townsend, Leanne, and Claire Wallace. 2016. Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. University of Aberdeen. https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2012. Affect and Emotion. A New Social Science Understanding. London: Sage.