ABSTRACT

Ecofascism—the union of fascist ideas and ecological notions—is a rising global issue. Ecofascism in the online sphere often encompasses imaginaries of utopia, love and nostalgia in concert with militarism and violence. This article examines cuteness as a strategic tool used to arouse culturally deemed “positive” emotions like joy, love and pleasure. The study draws on findings from an affective-discursive analysis of visual propaganda in the form of ecofascist memes. The analysis shows that cuteness softens fascist ideology and remasculinises and humanises fascism. Cuteness as a rhetorical tool lessens the needs for ideological defence, since cute signifiers condense structures of meaning into binaries of good and evil. Hence, the article argues that cuteness is a powerful affective political communication strategy that serves to reproduce masculine dominance by mobilising gendered and racialised imaginaries of nature, protection, empathy and belonging.

Introduction

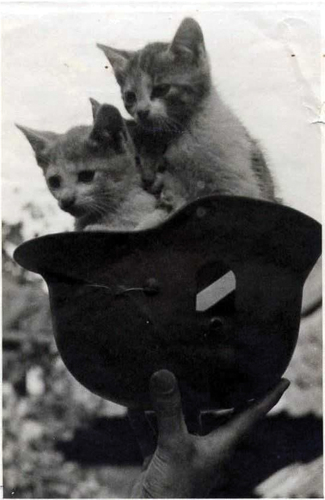

In spring 2020, my first year as a doctoral candidate in Örebro, Sweden, I stumbled upon a familiar sticker on a light post. Although small and scratched, the motif was clear: The Moomin cartoon character Snufkin was situated in a flowery meadow under a hovering Black sun, an esoteric Nazi symbol. By then I had been trawling fascist social media and become acquainted with images that represented the ecological proclivities of fascist ideology. In these “ecofascist” spaces, I found images that mixed elements of the cute and innocent with militarist and fascist symbols. The images depicted masked men cradling tiny kittens, posing with fluffy bunnies, or Hitler hand-feeding deer in a lush garden. Among the “cute” imaginaries were also collages of the Moomin cartoon, a now world-famous family of pale, round trolls who live in the idyllic Moomin valley, constituting a familiar feature of Nordic childhood culture. In far-right memes online, and on Swedish streets, however, the Moomins were featured with racist and violent signs.

This article examines what strategic work cuteness as a positive affect performs, i.e., how cuteness arouses and manipulates culturally deemed “positive” emotions like joy, love and pleasure through the use of cute signifiers. The article studies memes found on “ecofascist” social media Telegram channels. Memes have become central modes of far-right media communication as intervisual “bite-sized nuggets of political ideology and culture” that are easily consumed and shared on social media (Julia DeCook Citation2018, 485). The aim is to understand how positive visual communication attracts its readers and invites them into affective experiences, and positive affect is here investigated in the form of cuteness. The study answers to the following research question: How is cuteness used as an affective communication strategy in ecofascist propaganda, and what may the intended messages and receptions be? Ecofascism is a subform of fascism that combines fascist ideas with notions of ecological balance, and is here understood as a spectre of ideas, mostly presented in far-right social media realms, which may inspire reactionary politics and violence (Kristy Campion Citation2021; Brian Hughes, Dave Jones and Amarnath Amarasingam Citation2022; Balša Lubarda Citation2020). I examine the workings of positive affect in the representation, ideology, and communication of ecofascism. The memes in question are analysed as semiotic objects of multimodal communication (Gunther Kress and Theo Van Leeuwen Citation2001; Eemeli Hakoköngäs, Otto Halmesvaara and Inari Sakki Citation2020) that forms subjects affectively via gendered and racialised imaginaries.

Positive affect has long been a common rhetorical tool in fascist propaganda. Ideas of love and harmony in the nation and the family has structured historical fascism around a utopian myth of a homogeneous, happy people. Moreover, positive emotionality can be understood as a way of concealing dominance. Iris Marion Young (Citation2003) theorised the connections between violence and love, arguing that the framing of violence as protection contributes to upholding a gendered hierarchy. In this masculinist protection logic, those seeking to legitimise their right to protect must appear as kind and loving, but also as capable of exerting power and violence in order to protect a feminised nation or land. Fascists usually construct themselves as masculine protectors of a feminised nation or land which is considered vulnerable, open to invasion, or even penetration (Sara Ahmed Citation2014; Rachel Bailey Jones Citation2011). Hence, to justify (eco)fascism’s separatism and border protection, the trope of the loving nationalist protector against outside aggression is upheld.

Literature on affect within the political discourses of the far right has mostly assessed how commonly deemed “negative” and masculinised emotions like hate and fear circulate in white supremacist movements (Kathleen M Blee Citation2018; Michael S Kimmel Citation2013; Nitzan Shoshan Citation2016). Researching positive affect in ecofascist communication is important because infusing fascist messages with uplifting emotions is part of a strategy to mainstream and soften fascism and make its messages attractive to a wide audience. Moreover, ecofascism is constructed by an “emotionally powerful character” (Hughes, Jones, and Amarasingam Citation2022, 3) of romanticist imaginaries, which should be deconstructed in order to understand and counter its pull. Ecofascism undermines democracy and places the solution to natural and social crises on the racialised other, as well as refusing climate science and the transnational cooperation that is sorely needed to ensure climate justice (Daniel Lindvall, Kjell Vowles and Martin Hultman Citation2020; Cassidy Thomas and Elhom Gosink Citation2021). Therefore, its textual manifestations and its discursive tendencies must be separated from the environmentalist discourse on a whole.

The article is divided into a background section on positive affect and ecofascism; a theoretical-methodological section on discourse and cuteness, including an introduction of the memes. The findings and results are presented in an empirical section where I interpret the memes and discuss the emotional appeal of cuteness through assuming different affective subject positions. Finally, a discussion of cuteness in ecofascist propaganda follows, where I argue that appealing to cuteness is a powerful affective political communication strategy that serves to a) epitomise a racialised and sexualised masculinist protector logic; b) “brand” a Nordic (eco)fascism, c) signify authenticity, morality and virtuousness; and d) racialise and weaponise empathy.

Positive affect and ecofascism

Fascism’s emotional dimensions is important to analyse because of its strong affective drive. Robert O Paxton (Citation2005) argues that instead of a consistent and articulated philosophy, “mobilising passions” shape fascist action. Similarly, Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas (Citation2020, 6) argue that fascism is defined by “ideological energies” rather than institutions, and emphasise the aesthetic allure of fascist propaganda. These accounts are inspired by Roger Griffin’s (Citation1995) idealist definition of fascism as a radical authoritarian and totalitarian ultra-nationalism where an imagined rebirth of the nation is thought to purify and revitalise the people and the land. It is within a “cultural rebellion” against modernity that fascism mobilises its affective drives to purge the people and the land of “corrupt,” decadent and degenerate qualities found in liberal calls for equality and social justice (Bernhard Forchtner and Christoffer Kølvraa Citation2017; Zeev Sternhell Citation1995).

Ecofascism is not a new phenomenon (Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier Citation2011), but has recently received increased scholarly and public attention due to several terrorist perpetrators listing ecofascism as their ideological motif. Evidently, the looming ecological breakdown fuels fascism’s usual bourgeon in times of crisis (Andreas Malm and The Zetkin Collective Citation2021). While ecofascism is a global phenomenon, the paper focuses on the Nordic context. Contemporary Nordic ecofascism largely emanates from the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM), which accentuates the “holistic” and biologistic ideological tenets of Nazism (Maria Darwish Citation2021). Moreover, several ecofascist incidents have been linked to Sweden, amongst them a 2019 mink farm fire and planned abortion clinic bombing (Anton Kasurinen Citation2020). Ecofascism as an online culture seems to be run by young, militant men who discard the older generations of the NRM and seek more extreme and aesthetic movements (Daniel Poohl Citation2021). (Eco)Fascism is highly masculinised, often tapping into narratives of “gendered nationalism,” where female members are charged with reproductive responsibilities, while the men offer masculinist protection because “the security, bodily integrity, and rights of women perceived as belonging to the political community are seen as threatened by the ‘ … brown, uncivilised male newcomer … ’” (Annika Bergman Rosamond and Daria Davitti Citation2022, 8; see also George L Mosse Citation1998). Drawing on Nazism’s Blood and Soil-complex, ecofascism links “the native people” of a given area to the “land” by appealing to sociobiological “natural laws” that structure social and natural relations. Hence, a Blood and Soil-informed, “rooted” and gendered nationalism aiming to secure white racial predominance is at the core of ecofascist sentiments.

Earlier research shows how mainstreaming of the far-right often figures through cultural expressions (Forchtner and Kølvraa Citation2017; Cynthia Miller-Idriss Citation2017). Mainstreaming of fascism is here understood as the act of softening discourse to appeal to a wider audience (Katy Brown, Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter Citation2021). For instance, Nordic Nazis have replaced WWII imagery with pagan signs and Viking iconography to make the ideology palatable (Christoffer Kølvraa Citation2019). Tying into a global context of fascist mainstreaming efforts, research demonstrates the efforts of making Nordic far-right extremism positive and accessible for women and families (Tina Askanius Citation2021b). By use of irony and layers of coded messaging, far-right memes frequently appropriate and recontextualise cartoons, for instance the now global Pepe the Frog, mixing these with national socialist messages (Tina Askanius Citation2021a).

Fascism also mobilises “the natural” as a dedramatizing and sentimental rhetorical means. In Forchtner and Kölvraa’s analysis of German extreme right social media, nature-based imagery offered “ambiguous depiction[s] of an ‘affective’ experience or intensity,” inviting the observer to “a spiritual retreat” into the timeless realms of nature (Forchtner and Kølvraa Citation2017, 271–72). Similarly, Gustav Westberg and Henning Årman (Citation2019) demonstrate how ideals about living “a natural life” and outdoor lifestyle aesthetics emerge as expressions of a “natural” and “healthy” masculinised embodiment of Nordic national socialism, stilled against a “sick,” feminised Semitic and degenerate modernity. Moreover, research shows how online ecofascist propaganda draw on nature imaginaries in combination with national socialist messages featuring attractive white women, and/or references to Western civilisatory origins (Hughes, Jones, and Amarasingam Citation2022; Lisa Kaati, Katie Cohen, Björn Pelzer, Johan Fernquist and Hannah Pollack Sarnecki Citation2020). However, previous research lacks an assessment of the “dimension of reception” of the propaganda (Forchtner and Kølvraa Citation2017, 263). In taking an affective-discursive methodological point of departure in a multimodal analysis of visual ecofascist propaganda, I attempt to understand what kind of emotions this material may provoke in different contexts, and further, the “social work” that these emotions perform. The concept of cuteness occupies both affective and aesthetic realms and is related to the Japanese Kawaii culture (Joshua Paul Dale, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony P. McIntyre, and Diane Negr Citation2016, 35; Ingeborg Hasselgren Citation2020). As an affect, cute properties usually trigger a physical and emotional response. As an aesthetic, cuteness can be manipulated strategically for a variety of purposes: artistic, but also commercial and political. While cuteness is a feminised aesthetic, it is fundamentally ambiguous (Sianne Ngai Citation2015), and ideologically malleable. Hence, cuteness can inspire a range of affects depending on the context of the cute object. Cats are established as the ultimate internet cute signifiers, and has been weaponised by Nordic Nazism’s memes of heiling kittens (Askanius Citation2021a), by ISIS’ humorous and subversive use of cats (Matt Cornell Citation2016), and by the Ukrainian Azov battalion’s posing with kittens as an “effort to rehumanise” themselves (Graham Macklin Citation2022). However, little, if anything, has at the time of writing been published on the use of cuteness in ecofascist propaganda.

Cuteness intermingles with the innocence and vulnerability of childhood. In war propaganda, children often represent morality, nostalgia, and simplicity. In white supremacist logics, longing for a simpler, imagined past can be conveyed through imaginaries of childhood (see Maria Brock and Tina Askanius Citation2023). Moreover, children in propaganda functions as a call for protection (Michele J Shover Citation1975; Johanna Sköld and Ingrid Söderlind Citation2018; Margaret Peacock Citation2009). A rhetoric that promises to fight for children is also an implicit call to make an investment in the future (Lee Edelman Citation2004). Innocence as an ethical category works to create a “space of epistemic or experiential purity,” all the while producing a “constituent outside for the impure” (see Miriam Ticktin Citation2020, 202). This means that imageries used to represent innocence, such as children, can be strategically used as a rationalising force for war (Shover Citation1975, 482) and for attacking “the other.” In this paper, I investigate how cuteness is mobilised to appeal to the same vulnerability, innocence, and protection that is present in propaganda using children and childhood imaginaries.

Method, theory and data

Affect and multimodal discourse

In the discourse analytical approach, affect is understood as a relational concept that implies the formation of collective subjectivities through discourse (Margaret Wetherell Citation2012). Hence, I focus on the social work of emotions; how they are “accomplished, circulated and semiotically materialised in affective-discursive practices” (Gustav Westberg Citation2021a, 24). Emotions are understood as “embodied meaning-making practices within social and cultural discourses” (Salla Tuomola and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2022, 4), and I see the concepts of affect and emotions as fundamentally the same (Sara Ahmed Citation2010). To assess the social work of emotions in fascist propaganda, I employed tools from multimodal critical discourse studies (MCDS) (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2001). Multimodal discourse is defined as the socially constructed systems of knowledge that signify and organise aspects of reality using multiple modes of communication (Gustav Westberg Citation2021b, 21; Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2001, 4). MCDS has been acknowledged for its potential to analyse affective meaning making (Tommaso M Milani and John E Richardson Citation2021; Wetherell Citation2012).

I used Westberg’s (Citation2021a) framework for analysing affect as a multimodal practice (see Westberg Citation2021b; Anders Björkvall, Sara Van Meerbergen and Gustav Westberg Citation2020 for empirical examples), focusing on the concepts subject formation and strategic perspectivation. Investigating the subject formation of affective communication involves analysing how discourses invite the reader into specific affective subject positions. The semiotic invitation to an emotion works depending on whether the subject recognises and reconciles with the representational perspective (Westberg Citation2021a, 24). Strategic perspectivation is an interpretative technique that allowed me to engage with the affective subject positions offered by the discourses, and further to approach the memes from different subject positions. Hence, I approached the propaganda by assuming an engaged perspective; i.e., reading with the representation as a proponent, versus an estranged perspective, i.e., reading against the representations as an opponent (Westberg Citation2021a; see also Hilary Janks Citation2009). I added what I called a betwixt perspective to capture ambivalent readings from the position of an unaware or curious subject. The affordance of visual semiotics lets images communicate values without signifying distinctive meanings, which enabled an analysis of how the memes can convey ambiguous messages embedded in ideology and culture (Westberg Citation2021a). The assessment of the affects is limited to my interpretation. However, the method is contended to achieve “interpretative validity” in contemplating “how subject formation is accomplished in relation to the social and the collective” (Westberg Citation2021a, 25).

Material discussion

The data presented in this article is a part of a larger sample of images downloaded from ecofascist channels on the social media platform Telegram. Telegram has become increasingly used by the far right after a series of bans by Facebook and Twitter in 2019 (Aleksandra Urman and Stefan Katz Citation2020). Ecofascist channels serves as “‘content-banks’ for niche content that can be shared & socialised within the broader far-right ecosystem on Telegram” (Hughes, Jones, and Amarasingam Citation2022, 7; see also Jakob Guhl and Jakob Davey Citation2020). The Telegram channels are open, while administrators post images and text that subscribers may share, download and react to. The channel content is a mixture of text and visual artefacts: memes, photographs and animations depicting striking landscapes, utopian scenery, and historical references to glorified pasts of militancy and European heritage, some featuring slogans like “Nature is fascist” or “Feed your soul with positive content”. A report on ecofascist Telegram classified a large part of the images under the theme Utopia, illustrating how uplifting imaginaries take considerable space in ecofascist propaganda (Kaati et al. Citation2020). Reflecting the motley of ideological imaginaries, one finds references to Nazism, Odinism and forms of esotericism. When humans are depicted, images often depict male soldiers or “attractive” women donning traditional garb posing in natural landscape. Among this assorted environment, I found recurring references to cuteness.

My dataset consists of around 100 images collected from October 2020 to October 2021,Footnote1 primarily from open Telegram channels with “ecofascism” in their title or otherwise related to ecofascist symbolism through titles that signal affinity to far-right ecology.Footnote2 The selection criteria were that the images were posted or reposted in “ecofascist” channels and depicted nature-related imagery and/or animals. Far-right Telegram is a volatile space, and groups disappear, change names, and migrate to other platforms as Telegram have increasingly tightened their content policies. Although one cannot know who or where the forum participants are, I link several accounts to Sweden as the administrators frequently post references to Swedish culture, society, and geography. Out of my dataset, I identified several images containing elements that could be culturally classified as cute, such as cartoons, children, and animals like kittens, rabbits, and dogs. There are also charismatic animals that hold specific cultural meanings in Western nationalist projects such as owls, wolves and bears (Sam Moore and Alex Roberts Citation2022). For this article I selected five examples from the animal-human category and focus on one in which Adolf Hitler handfeeds deer. This selection exemplifies the first strategic way of using cuteness; Making the menacing cute, in where something brutal, i.e., a soldier, is softened by adding something endearing, i.e., a kitten.

In the ecofascist channels, I saw few reposts of typical far-right cartoons like Pepe the Frog, while finding several Moomin memes. Many of these were shared through other ecofascist channels or now defunct channels dedicated to Moomin memes. Most of the memes display either Moomin himself, hailing or carrying a racist flag, or the character Snufkin, a philosophical lone wanderer who thrives best in the wild. For this article, I selected five examples, and focus on one of Snufkin and the Black sun. The selection exemplifies the second strategic way of using cuteness; Making the cute menacing, in where something familiar, i.e., a cartoon, is recontextualised by adding fascist iconography, i.e., a swastika. As will become clear, I selected the Moomin cartoons as representative of ecofascist memes because the naïve romanticism of the Moomin universe lends itself to ecofascist imaginaries, and because they evoke a cuteness response as constituting cultural icons in Nordic childhood memorabilia. Additionally, Hitler and Snufkin share a cultural iconicity (Erica Boven and Marieke Winkler Citation2021) as signifiers of respectively evil and cosiness. In the memes, the original significance of what they represent is renegotiated.

Findings and discussion

Making the menacing cute: strong men and sweet animals

The sample below () represents typical examples of cuteness in ecofascist propaganda. Militant or masked men carry small animals or perform some compassionate act: cradling cats in their arms or in a helmet, holding a piglet, and petting a fox.

Figure 4. Telegram, April 2021. The original copyright belongs to the Great war Primary Documents Archive [http://www.gwpda.org]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 4. Telegram, April 2021. The original copyright belongs to the Great war Primary Documents Archive [http://www.gwpda.org]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/b005c5e0-8cf8-407a-bfb8-6fb1488d7ea4/rfms_a_2313006_f0004_b.gif)

Variations of these motifs have been posted on ecofascist Telegram. Representations of far-right and fascist masculinity usually centre on militancy, virility and physical prowess (Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Petö Citation2017; Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland Citation2022; George Mosse Citation1998). The example images demonstrate how traditional masculine qualities like strength, protection and capability are exhibited in tandem with usually feminised qualities like care and kindness. Moreover, the men’s faces are concealed, ensuring anonymity, but also outsourcing “the affective labour” to the animals in question (Cornell Citation2016). In his comment on the jihadists and their “ISIS-cats,” Cornell (Citation2016) notes that “by transferring the anthropomorphic qualities associated with cats back to the masked militant, the animal paradoxically humanises the man.” This softening and humanisation of militant masculinity constitute significant strategic moves in (eco)fascist propaganda.

A black-and-white photograph of Adolf Hitler () feeding deer was chosen as the main example for two reasons. First, I have seen it frequently in the reviewed ecofascist spaces. Second, Hitler’s iconic status as “embodying evil” (Stefan Hirt Citation2019) makes the affective workings of the image particularly salient, illuminating the plethora of contrasts in ecofascist imaginaries. The key symbols are Hitler himself and two deer, a doe and a fawn.Footnote3

Figure 5. Telegram, April 2021. The original copyright belongs to Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek [http://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/NIYT5DE2NZQHVSRLIQC2QNXX5KPU6PBS]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 5. Telegram, April 2021. The original copyright belongs to Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek [http://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/NIYT5DE2NZQHVSRLIQC2QNXX5KPU6PBS]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/750b1055-8c37-4142-954c-eda2d7d22b4c/rfms_a_2313006_f0005_oc.jpg)

Hitler’s display of affection towards innocent beings softens his authoritative persona. A part of this softening is accomplished due to the power imbalance between human and animal—the deer are subject to Man’s lethal power. Deer, however, also symbolise tenderness, purity, beauty, and femininity in European cultural tropes, accentuating their status as symbols of cuteness. Hitler was claimed to have deep respect for animals and nature. National Socialist circles often use the reiterated notion that Hitler was a vegetarian, as a sign of his kindness. A prominent NRM figure claimed in a podcast (Nordisk Radio, dir Citation2019) that:

Hitler himself liked to visit the cinema […] rumour has it that he always looked away when an animal on the screen were attacked, when the movie showed hurt animals. His company had to tell him when the scene ended, he could not watch it. […] This is the good side of Hitler that has survived all denigration.

Hitler is often discussed in Nazi discourse as the uttermost example of the “Aryan race.” This construction of Hitler speaks of a gentle man that does not tolerate harm towards innocent beings—a paradoxical claim, given what is known about the Third Reich. Kindness towards the innocent and defenceless is a classic feature of male heroism. In his capacity as an authoritarian leader, a benevolent patriarch and a saviour of the white race, Hitler is here presented as a heroic figure; powerful, but also compassionate.

Mythological ideas about the Aryans’ compassionate potential are connected to the Blood and Soil-complex and reiterated in the esoteric parts of fascism (Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke Citation2002). The “Aryan” is presented as the most caring and empathic of all human races, bestowing a divine connection to the natural world, imparted in a “heroic spirituality” of Indo-Aryan heritage (Goodrick-Clarke Citation2002, 60; Julius Evola Citation1995; Savitri Devi Citation1959). Moreover, a NRM podcast host echoes this perennial Nazi belief when discussing ritual slaughter, claiming that “many foreigners do not feel empathy towards animals. (…) [I]t is, you know, instinctual for the Aryan to care for animals if you compare to other cultures around the world” (Nordisk Radio, dir. Citation2017). These instincts allude to a “natural” capability for kindness that are specifically granted white people. Hence, in ecofascist discourse, the image is not only read as a historical document conveying Hitler’s loving character. It also perpetuates the interpretation of whiteness as an inherent capability to care for animals. Cuteness here is not simply the image of the deer, but the deer’s implications: The animal’s tenderness is reflected onto Hitler and humanises him. In Making the menacing cute, the construction of Hitler as a capable leader works best alongside the construction of him as compassionate. Thus, the meme functions as a strategy to present Hitler, and consequently fascism, as good, and communicate a belief in the natural compassion, and thereby the virtuousness, of whiteness.

The potential affective responses to the Hitler meme depend on the reader’s familiarity with Hitler himself. The targeted reader, the proponent, is harbouring (burgeoning) fascist sympathies. In an engaged reading of the meme, this position invites emotional responses within the spectrum of tenderness, trust, and reverence. The feeling of tenderness is a cuteness-response toward the deer, and particularly toward the fawn eating out of Hitler’s hand. The deers’ innocence, beauty and vulnerability may trigger feelings of affection and care. Hitler’s crouching position also invites a sympathetic emotional response. The reader is invited into a backstage glimpse of Hitler’s personal life, a private moment showing his “true spirit” of loving compassion. The deer trust Hitler enough to come close. This trust transposes onto Hitler, inviting the proponent to trust him as well. Moreover, the archival style of the image evokes feelings of nostalgia (Gunther Kress and Theo Van Leeuwen Citation2002, 356), and possibly reverence for an idealised fascist past under Hitler as benevolent patriarch.

From an estranged reading, i.e., an opponent´s position, the meme inspires unease and provocation. A disinclined recipient of fascist propaganda may be confused and shocked by the attempt to epitomise Hitler, known as the embodiment of evil, as a symbol of compassion. The combination of the cute and the evil creates a disturbing affective dissonance (Linda Åhäll Citation2018) that inspires deep discomfort.

The betwixt reading refers to the subject who does not recognise Hitler by first glance, or at all, or in any way experiences ambivalence or indifference towards the photo and may be called the unaware/curious position. This depiction may simply look like a moment of contact between a man and wild animals, thus evoking engaged feelings of tenderness and care. Such an ambivalent reading of the photo may convey an image of Hitler as loving and kind. This rhetorical trick hides the atrocities he architected, and consequently benefits the agendas of those wishing to render Nazism as a viable ideological and political option.

Making the cute menacing: fascist moomin cartoons

The sample below () illustrates how the Moomin cartoons are represented in ecofascist social media. One meme depicts a hailing Moomin, while he in the next carries a tiki torch and a camouflage jacket, which became far-right symbols of after the 2017 Unite the Right-rally in the US. Another meme shows the cartoon characters on their “way to the synagogue,” holding bloody weapons. A more cryptic fascist reference appears where the Moomin valley is portrayed below a pagan symbol used by the Finnish branch of the NRM.

Figure 6. Telegram October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 6. Telegram October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/f59477c6-dff1-433b-a390-92526882dca7/rfms_a_2313006_f0006_oc.jpg)

Figure 7. Telegram, October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 7. Telegram, October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/a9b4bd26-b124-4217-b22f-526e472238dd/rfms_a_2313006_f0007_oc.jpg)

Figure 8. Telegram, November 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 8. Telegram, November 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/72bff1df-2a1c-4f56-b20a-96eebdb1b554/rfms_a_2313006_f0008_oc.jpg)

Figure 9. Telegram, October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 9. Telegram, October 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/cc972933-d540-468b-a7a6-70d58828690d/rfms_a_2313006_f0009_oc.jpg)

These images mix childhood imaginaries of familiarity and innocence with hateful messages of racism, violence and anti-Semitism. This transgressive combination is especially provoking considering that the creator of the Moomins, Tove Jansson, was an unyielding anti-fascist activist during WWII and would most likely abhor this use of her art.

The Snufkin meme () was selected as the main example for three reasons. First, this is the Moomin meme I have seen most circulated in online ecofascist spaces, and the only one I have seen outside of the online sphere. Second, Snufkin carries symbolic meaning in the ecofascist discourse due to his character as a wandering, free spirit. Third, the Black sun depicted in the image is a frequent symbol in ecofascist propaganda (Kaati et al. Citation2020). The meme underscores ecofascism’s esoteric implications of a mystical race-based connection to nature.

Figure 10. Telegram, December 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.

![Figure 10. Telegram, December 2020. The original copyright of the moomin prints belongs to Moomin Characters Oy Ltd [https://www.moomin.com]. Permission to reproduce.](/cms/asset/13a787f1-97c9-43d8-a40d-e2e13aecc7eb/rfms_a_2313006_f0010_oc.jpg)

Snufkin and the Black sun comprise the central symbols of the image. Snufkin is standing in a flower meadow while a black solar wheel hovers above him in a burning red sky. The original drawing (Tove Jansson Citation2000) differs significantly from its replica: A yellow circle on a white background signifies the sun on a blue sky. Snufkin is originally clad in green but matches the Black sun wheel in the edited version, where the tricolour of red, black and white is read in reference to the flag that was used in the Third Reich. The Black sun is associated with the occult strands of Nazism and is even taken to represent “the mystical source of energy capable of regenerating the Aryan race” (Goodrick-Clarke Citation2002, 3–4). After WWII, the swastika has functioned “as an almost universal symbol of unredeemable evil” (William J. T Mitchell Citation2005, 129), and the Black sun has been popularised as substitute symbol (Goodrick-Clarke Citation2002, 3–4). Hence, the more enigmatic Black sun conveys Nazism with less stigmatisation than does the swastika, addressing an initiated reader, and circumventing its preceding bad reputation.

The meme is rife with contrasts. The flowers, the flute play and Snufkin’s shut eyes exudes peace and meditative simplicity. But Snufkin’s tranquillity is somewhat misplaced under the burning sky and a blazing sun wheel. The disparities between the warm and the brutal, the calm and the energising, the stability of nature and the crisis of the lit sky constitute a powerful visceral contrast serving to strengthen the affective appeal of the meme. The Moomins are well suited to constitute a specific ideological meaning in ecofascist discourse. They lead simple lives in their pastoral valley and can be used through connotations to the children’s cartoon to represent naïve nature romanticism in ecofascist imaginaries. The Moomins signify childhood, wholesomeness, and comfort, but also the familiarity of the heterosexual nuclear family with defined gender roles. Particularly Snufkin has obtained status as an ecofascist symbol: An ascetic, tranquil wanderer, living comfortably in nature’s solitude. Hence, these connotations infuse the Black sun with romantic values and associations from the Moomin universe. Likewise, the Snufkin character is recontextualised as a fascist figure.

Snufkin represents an ambivalent masculine figure in the ecofascist discourse. The role of a free wanderer is traditionally assigned to men, and similarly, Snufkin signifies a wise and wistful vagabond. Freedom in an ecofascist discourse means freedom from the decadence and impurities of modern industrialised and multicultural society, and from unwelcome aliens. Snufkin’s credibility as a masculine ecofascist symbol lies primarily in that he embodies such a free and independent wanderer in tune with nature. Inhabiting deep and esoteric qualities, he knows the mysteries of the vastness beyond the horizon: “Our” heritage and where “we” come from. Hence, he is also one to identify with in meditation and silence, perhaps even in bad times. A Swedish online gamer community associated with the fringe phenomenon Nordbol, a name of the mythical Nordic-Germanic lands as epitomised in esoteric fascism, often refers to Snufkin. In a podcast associated with this group of (seemingly only) men, they candidly discuss vulnerability and lack of human connection. As a contemplative, receptive figure, Snufkin can represent a masculinity to identify with in ecofascist discourse.

Due to its intervisual references, this Snufkin meme is best understood in the context of historical and contemporary Nazism. Its symbols and colours signify vitalism, emphasising the esoteric components of Nazism, and consequently ecofascism. The stark contrast between the warm, childish, and naïve versus the brutal, separatist and hateful constitutes an effective means of communication. Snufkin serves to communicate contradictory masculine ideals that can be related to nature and naturalness: unbound freedom outside from society, symbiosis, contemplation, and vulnerability.

The potential affective response to the Snufkin meme depends on the subject’s familiarity with Nazism, the Moomins and the “Nordic culture.” An engaged reading invites an emotional response within the spectrum of joy, nostalgia, and auspiciousness. The proponent may experience a humorous response to the transgressive mixture. As the Black sun signals something organic and esoteric, it conveys a sense of “magnetic etherealism;” a calling back to a romanticised Third Reich, but also to a numinous and fierce Norse past. The Black sun as a mystical source of energy in combination with the utopian Moomin imaginaries imprints the meme with ethereal and sublime qualities. The glaring contrasts of the idyllic and the dramatic ignites feelings of momentousness at a critical time, perhaps calling to protect the familiar and precious, embodied in Snufkin’s canonical figure. Thus, the combination of symbols invites the engaged reader into a mystical and fateful reality.

Additionally, the Snufkin figure inspires a cuteness-response, prompting warm and cosy emotions connected to tradition and childhood. The meme combines two nationalist discourses: an extreme national socialism steeped in a Blood and Soil-creed, and the banal nationalism (Michael Billig Citation1995) of patriotic pride by representing the Moomins as a canonised component of the Nordic cultural heritage. Both discourses inspire joy, nostalgia, and auspiciousness by delivering a promise of returning to a time of more natural simplicity. Snufkin is a figure to protect as a cultural symbol of peace, nature, stability, and familiarity, and to identify with as a free wanderer.

For the opponent, the meme may inspire fear and provocation, and possibly horrification at the use of Jansson’s legacy. A reluctant recipient of fascist propaganda, perhaps spotting the sticker on the street, may be frightened and shocked because the genocidal ideology that Nazism represents is conveyed through the broadly culturally cherished Moomin characters.

The curious or unaware subject might not know the meaning of either the Black sun or the Moomins or is otherwise experiencing ambivalence. Since the Black sun is a less discernible and stigmatised far-right symbol than the swastika, it might go unnoticed or be dedramatised by the other semiotic resources. The mere image of Snufkin under a decorative sun wheel has a general aesthetic appeal and evokes a cuteness-response that may overrule the effect of the other semiotic resources. The cuteness-response can take form as feelings of appreciation, familiarity, and enjoyment. Its emotional appeal therefore makes the meme accessible to those who are tinkering on the margins of fascist ideology and are at risk of being pulled deeper into fascism. The meme is also made accessible to those who are not aware of the meanings of the Black sun symbols—which might be anyone, but especially children and young people.

The strategic work of cuteness as a positive affect

The representations of militant masculinity in these images exemplify what Young’s (Citation2003) logic of the masculinist protector who balances love and violence to legitimise masculinist rule. Depictions of military men interacting with figures of innocence, as menacing made cute, maintain the idea of a strong protector capable of making hard decisions and exerting violence onto enemy targets when needed. This protectionism hinges on a gendered, sexualised and racialised potency. In ecofascist propaganda, the protector is constructed partly by cute and consequently feminised signifiers, but the intermingling with cuteness functions without “diminishing the social power or erotic capital of masculinity” (Dale et al. Citation2016, 14). Likewise, cuteness softens Hitler’s authoritative capacities as a leader without making him impotent. The propaganda thus reinscribes fascism’s eroticization of male dominance by drawing on the nationalist discourse of a feminised nation and nature under the “natural” protection of white masculinity. Moreover, the logic of the masculinist nationalist protector is itself a positive affective force inciting good feelings of trust and safety, even though these feelings are founded on fear of threat. The use of positive affect to this end enables a covert dissemination of violent signifiers under the guise of goodness and naturalness.

The dissonance between the cute signs’ genealogical symbolism and the fascist discourse that they are presented within makes the memes affectively striking. A Nordic “structure of feelings” (Raymond Williams Citation1966) connects nostalgia and familiarity to the Moomins, which is why misrepresentation of the cartoons likely elicits feelings of abjection for the estranged spectator. Fear and shock may be desired affective responses to far-right communication in where offending liberals and “normies” is a vital part of the rhetoric (Angela Nagle Citation2017)—hence, an estranged reading is not necessarily an undesired response to fascist propaganda. I argue that these memes are posted on ecofascist Telegram in veneration of a Nordic symbolic world. This means that the memes connect cognitively and affectively to the symbolic meaning of the Moomins in Nordic culture. As shown above, the affective qualities of the Moomin universe lend themselves to an ecofascist imaginary. Accordingly, appropriation of familiar Nordic culture imaginaries like the Moomins functions to “brand” Nordic (eco)fascism.

Cuteness is a condensed signifier for a binary Manichean logic, representing what is good versus bad. As feminised aesthetics, like the colour pink, transfers associations of kindness, peace and softness onto its setting (Fanny Ambjörnsson Citation2021), so does elements of cuteness influence its overall context. Drawing on cuteness represses other signifiers, meaning that cuteness, or positive affect in general, is a rhetorical tool that lessens the need for ideological defence. The more soft, happy, and uplifting a stance appears, the less it must defend its ideological underpinnings. Hitler’s “special bond” with animals signifies compassion and kindness towards the innocent, and the innocence lends itself to Hitler and consequently compromises his status as a symbol of evil. Similarly, since the start of the 2014 Russian occupation of Crimea, Vladimir Putin is often portrayed alongside animals in propaganda, his supporters claiming that the animals can instinctually “sense his goodness” (Chris, Alcock, dir Citation2015). The idea that animals can read someone’s moral character functions as a signifier for authenticity: Someone who is loved by animals must be trustworthy and genuine. Furthermore, authoritarian leaders often pose with children to demonstrate their benevolent and fatherly leadership of the nation, a propagandic strategy in personality cults to associate the leader with the goodness and innocence of childhood (Jan Plamper Citation2012; Michael H Kater Citation2006; John P Pittman Citation2017). This manoeuvre can be paralleled in fascist propaganda by invoking the childhood nostalgia of cartoons like the Moomins. Such appropriation adds a layer of transgressive humour in Making the cute menacing but can be read as a similar solicitation of innocence and familiarity. Hence, cuteness may function as a highly efficient propagandist tool to signify authenticity, morals and virtuousness.

Treatment of animals has been a significant point of Western othering processes (Per-Anders Svärd Citation2015), and cuteness contributes to discursive processes of othering through racialised conceptions of empathy. In ecofascist discourse, white people harbour unique empathic capacities due to a natural, instinctual heritage, and this seemingly biological competence is expressed by National Socialist organisation (see Devi Citation1959). “They don’t feel the way we feel about animals,” exclaims an NRM podcast show host: “ … many foreigners don’t feel empathy towards animals,” meaning that “there’s less empathy towards humans” (Radio Nordfront Citation2017, 01:58:00). The “others” are represented as biologically and culturally impeded with limited empathic abilities in comparison to the white, compassionate self. Hence, cuteness in the form of propaganda depicting tender moments between masculinist protectors and innocent animals is used to weaponise empathy as a tool for othering and racialization. This process reinforces an orientalist binary of the compassionate Self and the callous Other. The use of cuteness helps form a fascist subjectivity as inherently close to nature in emotional capacities. But this logic places men as stewards and protectors of nature rather than as nature. Thus, the fascist’s task as a masculinist protector is to defend those who are identified with nature: women, animals, and nature itself.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates how cuteness as an affective communication strategy serves to gender and racialise ideas about protection, empathy, morality, and nature in fascist discourse, as well as culturally brand Nordic ecofascism. I found that the propaganda incites various emotions that perform certain social work for fascism depending on the reader’s perspective. For the opponent, the transgressive mix of the cute and the brutal inspires fear and shock. The diffusing effect of the cute symbolism may be experienced as an infringement on the innocent and familiar. In addition to filling the role as an “insulted normie,” the affective dissonance provoked by the memes might create a reactive response by inciting emotions like anger and resolve, aligning the reader with an anti-fascist position.

The proponent is invited into a simplified Manichean reality in where fascism provides the solution for societal and natural problems. The cuteness propaganda may be understood to communicate that fascism is inherently moral, loving, and natural, and therefore trustworthy as a legitimate political option. As a flattening rhetorical means, cuteness and childhood imaginaries support a discursive horizon where the good is easily separated from the bad. Consequently, the proponent is called to join “the good side.”

The study shows how a masculinist protector logic, aiming to defend vulnerable and feminised objects, is represented through enticing visual imaginaries. The ecofascist discourse offers the proponent a protector position in this crucial time of natural and social emergency. In the security paradigm that characterises the modern western world, masculine superiority flows “from the willingness to risk and sacrifice for the sake of others” (Young Citation2003, 9). Cuteness presented alongside militarism serves as a rhetorical strategy in making the protector a legitimate dominator by accentuating the act of sacrifice itself, and by offering an affective representation of what the protector shall sacrifices himself for: innocence and righteousness. The ecofascist discourse invites the proponent to defend nature, women, whiteness, tradition, culture, and the future itself from infringement. This call offers meaning and potency in a time where especially men experience loss of historical socio-economical privileges. Hence, the study expands the understanding of how contemporary political (extremist) discourse offers the possibility of remasculinisation.

Finally, the unaware/curious position may contribute to bypass and thereby legitimise fascism. The ambiguous potential of the propaganda presented here has significant implications for youth and those at the margins of fascist culture. Knowledge about WWII may dwindle in the Nordic societies as those who still remember it pass away, and the “post-shame” society (Ruth Wodak Citation2019) is challenging historical accounts of the war and the holocaust. Attempts to destabilise historical facts and dedramatise fascist symbols is part of the discursive battle post-WWII. This development is especially dangerous for young people, who have a weaker temporal connection to the war and the Nazi occupations than previous generations, and who might be more attracted to transgressive culture expressions. General affective ambiguity toward fascist ideas and symbols are therefore perilous because it risks relativizing its brutal heritage. Even feelings of indifference are hazardous when encountering fascist propaganda, because of the lacking confrontational stance that ensues toward violent content and historical atrocities. Propaganda that mixes political messages with childhood culture not only appeals to youth, but it also appropriates the “affective values” of childhood imaginaries. Appealing to cute symbols can aid the mainstreaming of fascist ideology by infusing it with playful, familiar and accessible symbolism. That this propaganda especially targets younger generations with its affective pull, alluring aesthetics and violent appeal should therefore be taken utmost seriously by those concerned with the future.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Darwish

Maria Darwish is a PhD Candidate in Gender Studies at Örebro University, Sweden, investigating the relationship between ecofascism, affect and nature. Her PhD project examines how affect is channelled through ‘positive’ emotions to structure gender, race and human-nonhuman relations within ecofascist thought, and how this production of meaning serves to mainstream ecofascism and construct a Nordic national socialist and ecofascist narrative.

Notes

1. Due to my PhD project timeline.

2. The different groups have anywhere between 2000–7800 subscribers each at the time of writing.

3. Similar images depicting Hitler with animals also circulate in ecofascist spaces. This 1934 photo is originally from a series depicting Hitler’s time in his vacation home, and is reprinted as a postcard, including the German caption “The leader as an animal friend” (Digitale Bibliothek Deutsche Citation2022).

References

- Åhäll, Linda. 2018. “Affect as Methodology: Feminism and the Politics of Emotion.” International Political Sociology 12 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1093/ips/olx024.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. “The Promise of Happiness.”

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nf edn. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Alcock, Chris, dir. 2015. ‘Far Right and Proud’. Reggie Yates’ Extreme Russia. UK: BBC.

- Ambjörnsson, Fanny. 2021. Rosa: Den Farliga Färgen. Stockholm: Ordfront.

- Askanius, Tina. 2021a. “On Frogs, Monkeys, and Execution Memes: Exploring the Humor-Hate Nexus at the Intersection of Neo-Nazi and Alt-Right Movements in Sweden.” New Media 19 (2): 147–165. doi:10.1177/1527476420982234.

- Askanius, Tina. 2021b. “Women in the Nordic Resistance Movement and Their Online Media Practices: Between Internalised Misogyny and Embedded Feminism.” Feminist Media Studies 22 (7, April): 1763–1780. doi:10.1080/14680777.2021.1916772.

- Biehl, Janet, and Peter Staudenmaier. 2011. Ecofascism Revisited: Lessons from the German Experience. Porsgrunn: New Compass Press.

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. 1st ed. London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Björkvall, Anders, Sara Van Meerbergen, and Gustav Westberg. 2020. “Feeling Safe While Being Surveilled: The Spatial Semiotics of Affect at International Airports.” Social Semiotics 33 (1, July): 209–231. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1790801.

- Blee, Kathleen M. 2018. Understanding Racist Activism. London: Routledge.

- Boven, Erica, and Marieke Winkler, eds. 2021. The Construction and Dynamics of Cultural IconsVol. 12. Heritage and Memory Studies. Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.1515/9789048550838.

- Brock, Maria, and Tina Askanius. 2023. “Raping Turtles and Kidnapping Children: Fantasmatic Logics of Scandinavia in Russian and German Anti-Gender Discourse.” Nordic Journal of Media Studies 5 (1): 95–114. doi:10.2478/njms-2023-0006.

- Brown, Katy, Aurelien Mondon, and Aaron Winter. 2021. “The Far Right, the Mainstream and Mainstreaming: Towards a Heuristic Framework.” Journal of Political Ideologies 19 (2): 162–179. doi:10.1080/13569317.2021.1949829.

- Campion, Kristy. 2021. “Defining Ecofascism: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Interpretations in the Extreme Right.” Terrorism and Political Violence (0): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09546553.2021.1987895.

- Cornell, Matt. 2016. ‘Feral Memes’. The New Inquiry, November 8, 2016. https://thenewinquiry.com/feral-memes/.

- Dale, Joshua Paul, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony P. McIntyre, and Diane Negra , eds. 2016. The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness. 1st edn. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315658520.

- Darwish, Maria. 2021. “Nature, Masculinities, Care, and the Far-Right.” In Men, Masculinities, and Earth: Contending with the (M)anthropocene, edited by Martin Hultman and Paul Pulé, 183–203. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-54486-7.

- DeCook, Julia. 2018. “Memes and Symbolic Violence: #proudboys and the Use of Memes for Propaganda and the Construction of Collective Identity.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (4): 485–504. doi:10.1080/17439884.2018.1544149.

- Deutsche, Digitale Bibliothek. 2022. “Adolf Hitler als Tierfreund, 1934.” Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek 2022. http://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/NIYT5DE2NZQHVSRLIQC2QNXX5KPU6PBS.

- Devi, Savitri. 1959. Impeachment of Man. USA: Noontide Press.

- Edelman, Lee. 2004. “No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive.” In Series Q. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Eley, Geoff, and Julia Adeney Thomas, eds. 2020. Visualizing Fascism: The Twentieth-Century Rise of the Global Right. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Evola, Julius. 1995. Revolt Against the Modern World. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Revolt-Against-the-Modern-World/Julius-Evola/9780892815067.

- Forchtner, Bernhard, and Christoffer Kølvraa. 2017. “Extreme Right Images of Radical Authenticity: Multimodal Aesthetics of History, Nature, and Gender Roles in Social Media.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 4 (3): 252–281. doi:10.1080/23254823.2017.1322910.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 2002. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press.

- Griffin, Roger. 1995. Fascism, 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guhl, Jakob, and Jakob Davey. 2020. A Safe Space to Hate: White Supremacist Mobilisation on Telegram. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/a-safe-space-to-hate-white-supremacist-mobilisation-on-telegram/.

- Hakoköngäs, Eemeli, Otto Halmesvaara, and Inari Sakki. 2020. “Persuasion Through Bitter Humor: Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Rhetoric in Internet Memes of Two Far-Right Groups in Finland.” Social Media + Society 6 (2): 11. doi:10.1177/2056305120921575.

- Hasselgren, Ingeborg. 2020. ‘Cute Affectivism: Radical Uses of the Cuteness Affect among Activists and Artists’. Doctoral thesis (PhD), University of Sussex.

- Hirt, Stefan. 2019. Adolf Hitler in American Culture: National Identity and the Totalitarian Other. Brill Schöningh. https://brill.com/display/title/51315.

- Hughes, Brian, Dave Jones, and Amarnath Amarasingam. 2022. “Ecofascism: An Examination of the Far-Right/ecology Nexus in the Online Space.” Terrorism and Political Violence (0): 1–27. doi:10.1080/09546553.2022.2069932.

- Janks, Hilary. 2009. Literacy and Power. 1st edn. New York: Routledge.

- Jansson, Tove. 2000. Stora Muminboken. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

- Jones, Rachel Bailey. 2011. Postcolonial Representations of Women: Critical Issues for Education. 2011th edn. Dordrecht The Netherlands ; New York: Springer.

- Kaati, Lisa, Katie Cohen, Björn Pelzer, Johan Fernquist, and Hannah Pollack Sarnecki. 2020. “‘Ekofascism: En studie av propaganda i digitala miljöer’. Analys av våldsbejakande extremism FOI Memo 7441.” Totalförsvarets forskningsinstitut.

- Kasurinen, Anton. 2020. “Mordbrand misstänks ha koppling till ekofascism.” Expo se 2020. https://expo.se/2020/04/misstankt-hogerextremism-bakom-mordbrand.

- Kater, Michael H. 2006. Hitler Youth. Annotated ed. Cambridge, Mass. London: Harvard University Press.

- Kimmel, Michael S. 2013. Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era. New York: Nation Books.

- Kølvraa, Christoffer. 2019. “Embodying “The Nordic Race: Imaginaries of Viking Heritage in the Online Communications of the Nordic Resistance Movement.” Patterns of Prejudice 53 (3): 270–284. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2019.1592304.

- Köttig, Michaela, Renate Bitzan, and Andrea Petö, eds. 2017. Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. 1st edn. Gender and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. http://gen.lib.rus.ec/book/index.php?md5=810eac924aadecc0cba0f20f0a0886ff

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London : New York: Arnold ; Oxford University Press.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2002. “Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour.” Visual Communication 1 (3): 343–368. doi:10.1177/147035720200100306.

- Lindvall, Daniel, Kjell Vowles, and Martin Hultman. 2020. Upphettning: demokratin i klimatkrisens tid. Stockholm: Fri tanke.

- Lubarda, Balša. 2020. “Beyond Ecofascism? Far-Right Ecologism (FRE) as a Framework for Future Inquiries.” Environmental Values 29 (6): 713–732. doi:10.3197/096327120X15752810323922.

- Macklin, Graham. 2022. “The Extreme Right, Climate Change and Terrorism.” Terrorism and Political Violence (0): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09546553.2022.2069928.

- Malm, Andreas, and The Zetkin Collective. 2021. White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism. London; New York: Verso Books.

- Milani, Tommaso M., and John E. Richardson. 2021. “Discourse and Affect.” Social Semiotics 31 (5): 671–676. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1810553.

- Miller-Idriss, Cynthia. 2017. “The Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialization and Far Right Youth Culture in Germany.” Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mitchell, William J. T. 2005. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moore, Sam, and Alex Roberts. 2022. The Rise of Ecofascism: Climate Change and the Far Right. 1st edn. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Mosse, George L. 1998. The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nagle, Angela. 2017. Kill All Normies: The Online Culture Wars from Tumblr and 4chan to the Alt-Right and Trump. Winchester, UK ; Washington, USA: Zero Books.

- Ngai, Sianne. 2015. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Reprint ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: Harvard University Press.

- Nordisk Radio, dir. 2019. Ledarperspektiv #33: Nationalsocialism – Den Sant Gröna Politiken. Miljörörelsens Ursprung Och Djurrättsaktivism’. https://nordiskradio.se/?avsnitt=ledarperspektiv-33-nationalsocialism-den-sant-grona-politiken-miljororelsens-ursprung-och-djurrattsaktivism.

- Paxton, Robert O. 2005. The Anatomy of Fascism. Reprint ed. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Peacock, Margaret. 2009. “Broadcasting Benevolence: Images of the Child in American, Soviet and NLF Propaganda in Vietnam, 1964–1973.” The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 3 (January): 15–38. doi:10.1353/hcy.0.0083.

- Pittman, John P. 2017. “Thoughts on the “Cult of Personality” in Communist History.” Science & Society 81 (4): 533–548. doi:10.1521/siso.2017.81.4.533.

- Plamper, Jan. 2012. The Stalin Cult: A Study in the Alchemy of Power. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- Poohl, Daniel. 2021. “Ny högerextrem grupp infiltrerad - ledarna från Sverige.” Expo se 2021. https://expo.se/2021/03/ny-h%C3%B6gerextrem-grupp-infiltrerad-ledarna-fr%C3%A5n-sverige.

- Nordisk Radio, dir. 2017. “Nordic Frontier #10: Presenting the New Green Party.” https://peertube.se/w/gW4QXYyhuG8YGY2ReL4y6t.

- Roose, Joshua M., Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano, and Simon Copland. 2022. Masculinity and Violent Extremism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rosamond, Annika Bergman, and Daria Davitti. 2022. “Gender, Climate Breakdown and Resistance: The Future of Human Rights in the Shadow of Authoritarianism.” Nordic Journal of Human Rights (0): 1–20. doi:10.1080/18918131.2022.2072075.

- Shoshan, Nitzan. 2016. The Management of Hate: Nation, Affect, and the Governance of Right-Wing Extremism in Germany. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Shover, Michele J. 1975. “Roles and Images of Women in World War I Propaganda.” Politics & Society 5 (4): 469–486. doi:10.1177/003232927500500404.

- Sköld, Johanna, and Ingrid Söderlind. 2018. “Agentic Subjects and Objects of Political Propaganda: Swedish Media Representations of Children in the Mobilization for Supporting Finland During World War II.” The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 11 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1353/hcy.2018.0002.

- Sternhell, Zeev. 1995. The Birth of Fascist Ideology. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691044866/the-birth-of-fascist-ideology.

- Svärd, Per-Anders. 2015. Problem Animals : A Critical Genealogy of Animal Cruelty and Animal Welfare in Swedish Politics 1844-1944 - Per-Anders Svärd - Häftad (9789176492345) | Adlibris Bokhandel. Stockholm University. https://www.adlibris.com/se/bok/problem-animals-a-critical-genealogy-of-animal-cruelty-and-animal-welfare-in-swedish-politics-1844-1944-9789176492345.

- Thomas, Cassidy, and Elhom Gosink. 2021. “At the Intersection of Eco-Crises, Eco-Anxiety, and Political Turbulence: A Primer on Twenty-First Century Ecofascism.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 20 (1–2): 30–54. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341581.

- Ticktin, Miriam. 2020. “Innocence: Shaping the Concept and Practice of Humanity.” In Humanitarianism and Human Rights: A World of Differences?, edited by Michael N. Barnett, 185–202. Human Rights in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108872485.010.

- Tuomola, Salla, and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. 2022. “Emotion Mobilisation Through the Imagery of People in Finnish-Language Right-Wing Alternative Media.” Digital Journalism 11 (1, April): 61–79. doi:10.1080/21670811.2022.2061551.

- Urman, Aleksandra, and Stefan Katz. 2020. “What They Do in the Shadows: Examining the Far-Right Networks on Telegram.” Information, Communication & Society 25 (7, August): 904–923. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946.

- Westberg, Gustav. 2021a. “Affect as a Multimodal Practice.” Multimodality & Society 1 (1): 20–38. doi:10.1177/2634979521992734.

- Westberg, Gustav. 2021b. “Affective Rebirth: Discursive Gateways to Contemporary National Socialism.” Discourse & Society 32 (2): 214–230. doi:10.1177/0957926520970380.

- Westberg, Gustav, and Henning Årman. 2019. “Common Sense as Extremism: The Multi-Semiotics of Contemporary National Socialism.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (5): 549–568. doi:10.1080/17405904.2019.1624183.

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2012. Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding. Los Angeles ; London: SAGE.

- Williams, Raymond. 1966. Culture and Society : 1780-1950. New York: Doubleday.

- Wodak, Ruth. 2019. “Entering the “Post-Shame Era”: The Rise of Illiberal Democracy, Populism and Neo-Authoritarianism in EUrope.” Global Discourse 9 (1): 195–213. doi:10.1332/204378919X15470487645420.

- Young, Iris Marion. 2003. “The Logic of Masculinist Protection: Reflections on the Current Security State.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 29 (1): 1. doi:10.1086/375708.