ABSTRACT

The research programme on transformative agency by double stimulation within cultural-historical activity theory is a resource for responding to pressing societal needs of our time. The peculiarity of this programme lies in the ambition to develop a rigorous approach to grasping processes of collective transformative agency and generating viable pedagogical instruments to support them. The metaphor of warping is useful for this endeavour. In this article the metaphor is applied to three empirical examples to show how collectives generate transformative agency, how the process evolves or flounders, and how it can be supported. The first example stems from a waiting experiment originally described by Vygotsky as a prototypical example of this type of agency. The second and third examples stem from data collected in a study on eradicating homelessness in Finland. The article discusses the implications of this approach for research and practice.

Introduction

In response to pressing current societal needs, scholarship in the learning sciences needs to engage with studies of agency understood as collective strivings towards the common good (Blanchet-Cohen and Reilly Citation2017; Boyte and Finders Citation2016). Coordinated efforts at counteracting poverty and homelessness are examples of these kinds of endeavours. Among a variety of approaches to agency (e.g., Archer Citation2003; Bandura Citation1989; Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998), the programme on transformative agency (TA) within cultural-historical activity theory is distinctive (Sannino Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Sannino, Engeström, and Lemos Citation2016) in that it is a resource for actually responding to pressing societal needs. The peculiarity of this programme lies in the ambition to develop a rigorous approach to grasp processes of collective formations of TA and to generate viable pedagogical instruments to support them.

Findings from recent studies point at double stimulation as a core principle for understanding and fostering this type of agency (e.g., Barma, Lacasse, and Massé-Morneau Citation2015; Engeström, Kajamaa, and Nummijoki Citation2015; Haapasaari and Kerosuo Citation2015; Hopwood and Gottschalk Citation2017; Lund and Eriksen Citation2016; Nuttall, Thomas, and Henderson Citation2018). With the help of the metaphor of warping, or anchoring forward, applied to three empirical examples, this article illustrates how collectives accomplish change amidst uncertainty, how transformative agency by double stimulation (TADS) emerges, how it can gain consequential momentum, what might obstruct this process, and what pedagogical means may be mobilised to support it.

The article begins with a brief overview of the literature on agency and of the specific contribution of TADS theory. It points at different conceptions of anchoring and moves to a detailed description of agency formation by means of warping. Three subsequent empirical sections make use of the warping metaphor to show how collectives initiate this type of agency, how the process evolves or flounders, and how it can be supported. Example 1 stems from a ‘waiting experiment’ following a procedure originally described by Vygotsky Citation([1931] 1997) as a prototypical instance of TADS. Examples 2 and 3 stem from data collected in a study on eradicating homelessness in Finland. The article ends with concluding remarks on the implications of this approach for research and practice.

Approaches to agency and the contribution of the warping metaphor

A central topic in the learning sciences, agency has been heavily influenced by psychological (e.g., Bandura Citation1989) and sociological (e.g., Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998) theorising. When ‘exogenous’ conceptualisations transfer somewhat uncritically to complex contexts of learning and development, they run the risk of remaining disconnected from the processual dynamics inherent to these contexts. Dominant psychological and sociological conceptualisations of agency typically offer categorisations of different types of agency, remaining silent or unclear about the process of emergence and development of agency. Understandings of agency as an inherent quality residing within the individual, or as an outcome of a vaguely defined interplay between individuals and their social contexts, are insufficient to respond to today’s pressing societal needs.

The challenges of equity and social justice require multi-agency initiatives across sectoral and hierarchical boundaries, and the mobilisation of the whole society with its organisations and neighbourhoods. If scholarship on agency in the learning sciences wants to become relevant to such challenges, it must adopt an agenda of theorising TA which fulfils three requirements: 1) it informs concretely lived change processes and deliberate efforts at accomplishing transformations of tangible activities; 2) it adopts a dialectical rationale which affords thinking in terms of processes and relations rather than in terms of static and abstract categorisations; 3) it lends itself to the actual fostering of TA and contributes to the creation of conditions to concretely enact agency.

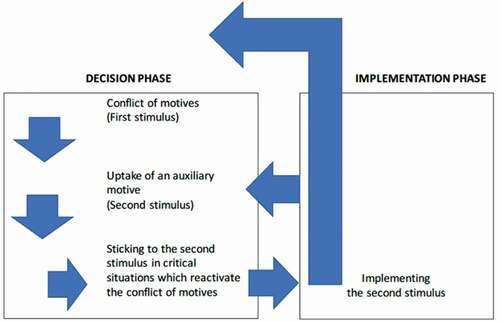

Vygotsky’s principle of double stimulation (Citation[1931] 1997; Sannino Citation2015b), expanded by means of the metaphor of warping, is a powerful candidate for such an agenda. TADS is a process by which individuals or collectives can intentionally break out of conflicts of motives and change their circumstances by forming auxiliary motives (also called second stimuli) and implementing them systematically ().

A problematic situation triggers a paralysing conflict of motives (also called first stimulus). In trying to cope with the problem, learners turn to artefacts (or second stimuli) and decide to rely on them when instances of the problematic situation reoccur. Each new instance of the problematic situation is cognitively and emotionally critical in that it reactivates the conflicting motives. When the learner actually puts into use the second stimulus, this implementation helps the learner to gain control of and transform the problematic situation into one that is understandable and manageable. Repeated implementation of the second stimulus strengthens the learner’s understanding of the problem and capacity to take further actions. As a result, both the problematic situation and the learner are transformed.

Double stimulation makes it possible to trace the unfolding of TA (several papers in this Special Issue take this up as a key analytical focus: Grant, this issue, within a Change Laboratory; Chawla-Duggan et al, this issue, in relation to using video to take children’s perspectives; Hopwood and Gottschalk, this issue, in professional support provided to parents; and Hopwood et al, this issue, in the context of professional education in healthcare). Furthermore, the principle allows expanding the notion of agency from inner psychological properties towards external artefacts that may become second stimuli and trigger transformative actions. Double stimulation is also one of the key principles on which the formative intervention method of the Change Laboratory (CL) relies (Sannino, Engeström, and Lemos Citation2016). With the CL, research in the learning sciences can serve as a catalyst for participatory analyses and design leading to or supporting change processes. The type of learning pursued with CL- i.e., expansive learning (Engeström Citation[1987] 2015)- entails the development of new visions and collective long-term engagement. This type of learning goes hand in hand with TADS, which is both a core process and outcome of expansive learning.

In double stimulation, the second stimulus is an artefact that serves as a fixed point or stable platform for transformative action. In Vygotsky’s Citation([1931] 1997) description of the waiting experiment, a subject was torn between the motive of remaining in the experiment room where nothing was happening and the motive of moving on with her life. She used the clock as a second stimulus, saying to herself ‘when the clock strikes two, I will leave,’ and then breaking out of the paralysing conflict between motives and actually leaving when the clock struck two.

A wide range of artefacts may be used as second stimuli depending on the problem situation and available resources. Literature on TADS lists a good number of them (e.g., Sannino and Laitinen Citation2015; Sannino Citation2016; Hopwood and Gottschalk Citation2017; Grant, this issue, and Hopwood and Gottschalk, this issue, extend this work). They can be for instance material things (a clock, a calendar, a cup of coffee, a string tied around a finger …) or discursive entities (a discussion on a specific topic, a set of questions, a song …). What makes these artefacts second stimuli is that the learner deliberately takes them up as auxiliary motives to face the conflict of motives triggered by the problem situation.

We may think of the second stimulus as an anchor. Anchors are commonly understood as stabilising devices to prevent a vessel from moving. However, not all anchors have this function. Beside the heavy-weight anchors, there are also kedge anchors serving the purpose of ‘warping,’ that is, pulling the anchor once it has settled on the ground, for moving the vessel away from a problem area.

Traditional anchoring by stabilising devices can be characterised as ‘anchoring backward.’ This type of anchoring relies on background knowledge and relatively stable representations utilised for explaining problem situations and for acting in such situations. Concepts of anchoring in the works of Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974), Moscovici (Citation1983) and Marková (Citation2000) are examples of anchoring backward. Anchoring forward, in contrast, consists of stepping into the unknown. The notion of material anchors in Hutchins (Citation2005) partly conveys this notion of forward-oriented anchors. Forward anchoring involves the formation of novel representations emerging through personal sense-making, social interaction and experimentation embedded in the materiality of a problem situation (see also Hopwood and Gottschalk, this issue). Second stimuli understood as forward-oriented kedge anchors are instrumental in the elaboration of new meaning which may be stabilised to the point of supporting transformative actions in problem situations for which there are no known solutions.

Warping doesn’t only consist of a forward movement. This would be inconceivable in turbulent waters. Also, an activity undergoing transformation naturally brings to the surface the cultural-historical heritage that defines what the activity in question actually is for those who inhabit it and are used to the consolidated ways of carrying it out. Warping therefore tendentially suggests a movement forward but nevertheless cannot exclude backward influence and episodes.

A successfully implemented second stimulus in TADS may be understood as a warping anchor that hits the ground and allows the vessel to move forward. Actions of throwing the kedge anchor are made in the attempt to find suitable ground. These are search actions. Only when the kedge is hooked to the ground does the crew regain control of the situation allowing them to pull the vessel out of harm’s way. These are taking-over actions: the vessel is still in the troubled area, but the crew are able to manoeuvre it. Breaking-out actions occur when the vessel is moved away from the problem area.

Example 1: warping in the waiting experiment

Vygotsky Citation([1931] 1997) used the waiting experiment as a paradigmatic example of TADS. In his description, a person is escorted to a room and is told that the experiment will start soon, but the experimenter does not return. My research group carried out the experiment with 25 individuals and 30 collectives of three to four participants. The data consist of videotaped and transcribed waiting experiments followed by stimulated-recall interviews with the participants, also recorded and transcribed.

The data analysis results are reported elsewhere (e.g., Sannino and Laitinen Citation2015; Sannino Citation2016). Here, I focus on the case of one collective as an example of how the metaphor of warping helps elucidating TADS beyond the simplified model in .

The collective in the example had three participants (M1, N2, N3) who were taking part in an intensive university course. The course had already run for two weeks and was still ongoing when they agreed to volunteer to be part of an experiment. When the three participants came to the room designated for the experiment, the other participants in the course went to the cafeteria in the same building to have coffee with one of the course instructors.

Immediately after entering the room the participants started searching for material support in the environment with both their gaze and explicit statements: the one-way mirror window, the cameras on the ceiling, the room temperature, the side glass door and the main door. The discourse of the participants increasingly conveyed considerations for performing specific actions linked with the material arrangements in the room, e.g., ‘Can we watch through this or they watch us?’ (N3-14); ‘We can start to speak (about) a problem with this research’ (M1-23).

Statements like these fulfil the characteristics of warping search actions. None of these search actions, however, ‘hit the ground,’ as the other participants did not build on them. This changed when N3 asked a question concerning the course which both the other participants responded to by providing lengthy answers ().

Grounds for arguing that N3’s question served as a warping anchor (or second stimulus) that hit the ground may be found in the preceding speaking turns by the other participants:

Do you want to wait or you’d like to do something else? (N2 tilts her head towards the window by the door – the direction where the other course participants were in the cafeteria with an instructor) (N2-43)

I don’t know what we can do … You know we Germans just sit and wait until somebody says (M1-44)

We could do something more meaningful, like go for coffee – we can leave a note on the door saying ‘Annalisa, we are in the cafeteria’ (N2-45)

N2-43 explicitly voiced a conflict of motives, between waiting and doing something else, the latter motive with a visible reference to ‘leaving’ conveyed by means of the movement of the head. N2-43 was in itself a search action undertaken to test the preconditions ‘on the ground’ for the anchor to find traction. The response by M1-44 indicated that for him it was OK to wait. The conflict of motives voiced by N2 appeared therefore as not much of a concern for M1. In other words, the search action in N2-43 did not ‘hit the ground.’ Yet, N2 did not give up and initiated another search action, related to and reinforcing the one in speaking turn 43. This interaction between M1 and N2 created suitable conditions for N3 to initiate her own search action in speaking turn 46, to transform the situation into something meaningful for her and possibly for the others. Against the background of the exchange between N2 and M1, N3-46 was an anchor (or second stimulus) which served the function of an auxiliary motive in response to the conflicting motives voiced by N2-43.

The transcript also offers evidence that, from the formulation of N3’s question on, the participants gained control of the situation for a period of time: 66 speaking turns were used by the three participants to discuss a concept of the course, out of the total number of 142 speaking turns taken during the entire stay in the room. In the stimulated recall interview one of the participants referred to this discussion on the course contents as the reason that kept them in the room.

The discussion about the course offered a momentary (but not a final) means to respond to the conflict of motives voiced in N2-43 and 45. In the stimulated recall interview, N2 actually acknowledged that it took long time before her idea of leaving the room was taken up by the three participants. Nine negotiation exchanges, covering between 2 and 16 speaking turns each, took place before the three participants took action to leave the room, eventually breaking out together.

When the conversation about the course came to a close, N2 returned to her original search for action: ‘Ok, anything else to discuss or otherwise we could go for coffee?’ (N2-91). Once more, N2’s initiative did not ‘hit the ground,’ as the other two participants did not seem keen to leave. As a response, N2-94 indicated that the discussion about the course was no longer enough to keep her there and, in the absence of some other meaningful topics for discussion, she was minded to join the rest of the course participants and the instructor in the cafeteria.

The conclusion of the course discussion in the experiment room was, however, a critical moment in the TADS process. In , this is the moment when the conflict of motives is reactivated and the second stimulus may or may not be implemented. N2 encountered reluctance on the part of the other participants to write the note (second stimulus) she had suggested previously would allow them to leave the room.

Twenty one additional speaking turns on the topic of the course followed N2-94. When this further exchange on the course came to an end, N2 resumed her search action, ‘throwing the kedge again’ in speaking turn 116 when she suggested once more writing and leaving a note for the experimenter: ‘Right … Could I convince you to leave the room and we leave a note to Annalisa in case’ (N2-116).

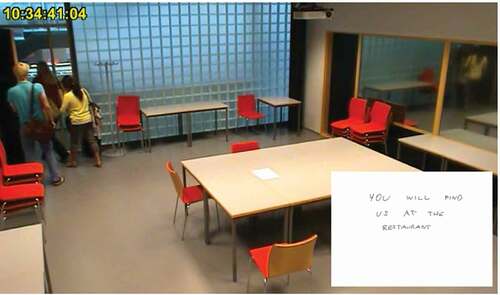

This time M1 seemed to align with N2’s initiative and the group started to jointly prepare to ‘throw the kedge’ towards leaving the room. Despite N2’s perseverance with the suggestions for leaving the room after writing a note, at this point she appeared keen to attenuate the rupture this leaving might represent: ‘if she really wanted to come here, we can be found upstairs’ (N2-118), ‘Now we can ask further questions’ (N2-120). These statements can be interpreted as indications that even N2 was concerned about the experiment, besides being adamant to leave, making it clear that aspects of the original conflict of motive were still present for her. It can therefore be argued that the note itself () they now started writing for the experimenter was yet another anchor (second stimulus) in response to the original conflict of motives triggered by the waiting experiment.

The writing of the note was a collaboration between M1 and N2, although there were forceful initiatives from N2 to dismantle the last of M1’s hesitations. The most blatant of these initiatives was that N2 made M1 write the note she had been so adamantly suggesting (). These initiatives from N2 are further evidence of how difficult the adoption and implementation of a second stimulus can be, even for a most determined person.

M1-121 asked if they were going to actually leave a note, to which N2 responded by sliding a notepad and a pen in front of him, starting to dictate the text of the note (N2 122: ‘Annalisa, we are in the cafeteria … ’). A couple of additional hesitations were expressed by M1 when he tore apart the first draft of the note and started a new one, and when he hesitated at the use of the word ‘bar’ (M1 127). Again, N2 promptly responded suggesting what to write and why (128). As soon as M1 completed the writing of the note he got up and placed it in the centre of the table, followed by N2 who also stood up.

During the writing of the note, N3 had limited herself to listening and looking at what was being written on the notepad. She eventually joined the two others, picking up her bag from the side table, but what she said soon afterwards was indicative of her position in this collective process of transformation: ‘Do you know if this is the experiment?’ (N3-133) and ‘So the experiment has finished?’ (N3-135). N3’s concern seemed to be with the nature and fate of the experiment, while at the same time she was gathering her belongings and moving towards the door to leave with the others. Wanting to comply with the experiment set up by the experimenter, whatever this experiment might have been, and wanting to leave the room seemed still to act as two conflicting motives for N3.

Despite the differences among the three participants, all of them left the room at the same time ().

The written note was adopted by the participants as a second stimulus supporting movement forward. Leaving the room happened practically right away after the note was completed and left on the table for the experimenter. The two subsequent second stimuli (the question in N2-43 and the written note) created a momentum which literally ‘pulled them out’ of the room. Only 35 seconds passed between the completion of the note and the leaving of the room, including the time the participants collected their belongings. This prompt occurrence of the implementation step is in line with the original description by Vygotsky of TADS, according to which, after a laborious decision phase the transformative action may take place as if automatically in the implementation phase.

Example 2: warping in Finnish Housing First work with residents

Work with poverty and homelessness resembles rescuing the neediest in the society in the middle of a storm in the open sea during which too often clients fall out of the reach of the services they badly need. To navigate such rough seas, kedge anchors and warping are essential.

In an interview a senior supervisor in a housing unit described what she defined ‘foundational work’ with the residents in terms that echo TADS.

There is no other way. The client must be put in a situation in which she herself sets her own goals and makes commitments. This must be accomplished every time. An example is a client of ours who uses drugs. There were frequent visits with outsiders coming to the unit during the night. Following those night visits which were brief and difficult to monitor made me suspect that selling (of drugs) might be happening. We organized a negotiation which was attended not only by the client and myself, but also the social workers and other people who were involved in the case and treatment of this client. In this negotiation we reached an agreement with this client that for one month there will not be a single night visit. This was where we wanted to draw the boundary and we drew the boundary together … and the client actually kept the agreement. You could consider that this is interfering with the client’s self-determination. However, the other alternative would have meant immediate eviction. … In complex situations or crisis situations, the only alternative we have is to ask the client: ‘Do you want to continue living here? And, if so, what kind of goals do you set so that you can actually continue living here? We have these rules. What are you willing to do so that you can continue living here?’ We cannot dictate these goals to the client. That would be completely futile. It must come from the client him- or herself. We sit as long as it takes until this (agreement) is established. (Sannino Citation2018, 390)

Setting up a negotiation after serious incidents is the way practitioners in housing units proceed to initiate TA. The negotiation meeting bears some important similarities with the waiting experiment in that it is a setting in which the conflict of motives is brought to focus. In the case of the excerpt above, the motive of continuing to have an apartment clashed with the motive of continuing to receive night visits. The commitment of the resident to have no visits for one month, to which the involved parties in the negotiation meeting agreed, was the kedge that ‘hit the ground’ as the resident actually honoured the commitment.

This ‘foundational work’ is at the core of Finnish Housing First (FHF) (Pleace et al. Citation2016; Y-Foundation Citation2017) and has played a key role in the progress made in this country towards eradicating homelessness. As the head of services (HS) in a housing unit put it, ‘The most important thing is to get the will of the resident expressed. Many of the residents always answer “I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know,” so to get even just a little bit of the resident’s own will expressed is of utmost importance.’

However, if this foundational work remains confined within the walls of the units, it runs the risk of exposure to influence from different directions in society which can make the kedge lose traction. This is why housing units invest a lot of effort in reaching out to outside actors, with a particular emphasis on the immediate neighbourhood.

For instance once during my work shift I received a call from the shopkeeper saying ‘there is this guy here completely drunk who is drinking alcohol straight from the bottle and eating food straight from the shelf. What am I supposed to do?’ So I came (to the shop). Then we made an agreement with the shopkeeper that he makes an estimate of how much the client had consumed and put the charges on his account. And the client was also in agreement that this will be put on his account. (Sannino Citation2018, 391)

Similar to the negotiation meetings within the units, reaching out to the neighbours is also a way in which frontline practitioners attempt to bring the conflict of motives into focus and therefore to mobilise TADS. In the case of the excerpt above, the motive to ‘facilitate the clients taking charge of their lives’ clashed with the motive of wanting a peaceful neighbourhood without disturbances caused by the unit’s residents. The agreement with the shopkeeper of having the costs of the consumed alcohol and food put on the resident’s account was a kedge that ‘hit the ground’ as the resident agreed to pay his dues.

Besides incidents such as the two discussed above, work and life in housing units are primarily focused on helping the residents to take charge of their lives on very basic issues such as paying the rent, washing themselves, cleaning the apartment, and taking steps towards independent living. The following case reported by a housing counsellor describes how warping applies to mobilising TADS when the focus in on these basic issues.

We were cleaning together the home of one of the residents. I had never seen such a home. The first time I entered I could stay there merely 15 minutes, although I wore a respiration filter. The biowaste smelled so strongly, there were remnants of food, and stuff nearly from the floor to the ceiling. So we cleaned together several times. I said that you cannot live like this, you deserve better, this is not a life of a human being. He agreed, but he said that he cannot clean when he is sober. He has to take amphetamine to be able to clean. We discussed this many times, each time a bit more thoroughly. One day he suddenly said, ‘It’s nice to clean when I’m sober, I get much more done when I’m sober.’ He then looked at the apartment and said, ‘This is a terrible pit, I cannot live like this, this is not a life of human dignity.’ And this came from himself that day. This was a moment I experienced as a success.

How long did this change process last?

Well, it is still going on, it needs support so that he doesn’t fall back to the old way. But it did take several weeks of cleaning together.

When did the moment of success occur for you and him?

We had met certainly ten times, before the initiative came from him.

The many discussions between the resident and the housing counsellor established a space in which the resident’s conflict of motives could be brought into the open: the motive of living ‘a life of human being’ clashing with the motive of taking amphetamine. The discussions, ‘each time a bit more thoroughly,’ led the resident to agree on the unsustainable condition of his living without being able to clean his apartment. Several weeks of cleaning together with the housing counsellor served as the kedge; the practitioner used every opportunity to engage in this joint task with the resident (‘It did take several weeks of cleaning together’ and ‘We had met certainly ten times, before the initiative came from him’). Again, the metaphor of the kedge seems to grasp something essential in these numerous attempts at ‘hitting the ground’ and helping the residents to move forward. The housing counsellor was actually explicit about the anchoring function of these several joint cleaning sessions: ‘it needs support so that he doesn’t fall back to the old way.’

This case echoes N2’s numerous attempts to leave the room made in the waiting experiment. The professionals in this field are often in a position similar to N2’s. As a night shift worker put it, ‘changes are often quite small in the residents’ behaviour … It is important to accept incompleteness in this work … It is also that things tend to take their own place and time and if something has not succeeded seven times, one cannot say that it would not succeed the eighth time.’ This case points to the transformative power of warping focused on basic issues of ordinary life. Reaching control over the condition of his apartment with the help of discussions and cleaning sessions with the housing counsellor led this resident to realise the need to stay sober in order to be able ‘to live a life of human dignity.’ In other words, gaining control over this basic living issue means taking a step forward to address broader and more severe problems in the lives of these residents.

Against the background of the existing literature on agency, it might be tempting to claim that the cleaning case is primarily about a very agentive practitioner who was able to mobilise if not ‘give’ agency to this resident. However, TADS warping is far from being limited to individual characteristics or initiatives. The service agreement between the city and the NGO which owns and operates the housing unit requires that the apartments are kept clean. The residents have primary responsibility for cleaning their apartments, but, if really needed, it can be done with staff or, by a staff member as a last resort. The work described by the housing counsellor is therefore situated within this broader system of activity.

The work carried out in the unit to ensure that the apartments are cleaned entails, for instance, regular assessments of cleanliness by employees and the resident, and related discussions and decisions about the date by which the condition of the apartment will be improved. The agreement is meant to fix concretely what is done, how often, and by whom. This negotiated way of working has only recently been implemented in the unit in question. Earlier, the unit imposed strict requirements involving penalties. As a consequence, HS explained, the staff office regularly had on the wall ‘a long list of residents who could not have visitors as a punishment mainly for having not cleaned their apartments properly.’

The broader activity in which the excerpt on cleaning situates indicates that the resident’s TADS was at the same time TADS for the organisation and its workers. Faced with the evidence of long list of punished residents, the unit had to find a way to honour their commitment with the city. Most importantly, the leaders of the NGO in charge of the unit felt that the unit’s control culture, exemplified by the forbidden visits, was not fulfiling its primary role to support the residents in making steps towards independent living. In other words, the operant conditioning methods previously in place in the unit did not work to allow the residents to start taking responsibility for their ways of living. The NGO became increasingly concerned about the wellbeing of the residents, to the point that it initiated a major organisational transformation that literally turned the unit around.

The youth housing unit is a building with six floors and 91 apartments owned by a prominent NGO. Six years after the unit was created, and during which time the control culture was consolidated, the NGO decided to radically transform the unit by changing its formal administrative organisation, the workers’ job descriptions and divisions of labour, and the service space. The director was replaced with two heads of service who were given the mandate to lead the transformation. They had a shared critical view of existing rigid structures focused on punishment and control which they wanted to eliminate.

The original arrangement of the service space was emblematic of the control culture in the unit. The residents were only allowed to enter through the backdoor. This entrance opened into a very small space with an information desk from which the employees used to control the residents’ movements from behind a plexiglass screen and with the help of cameras and monitors. If the residents needed to approach the workers, they had to do so from behind the screen. The NGO’s service director characterised this space as ‘hurtful, inhuman … and absurd.’ This was a very unpleasant service space for the residents, too. It represented a strict separation and a power relationship between the workers and the residents. Yet for many workers this service space with its dividing plexiglass represented safety.

Less than three months after the arrival of the two heads of service, the information desk was closed and, step by step, a common ‘aula’ started functioning. With this new arrangement the residents entered the building through the main door which gave access to a large entrance hall, or lobby that had been converted to a community space used as a living room for residents and staff with a big table, sofas, television and newspapers.

The majority of the staff strongly resisted this transformation. Tacit power structures among the personnel came to the surface preventing those in favour of the change from adopting an open stance. The unit had a history of transformation attempts which failed because of staff resistance. The heads of service responded to the resistance and inofficial power cliques by systematically engaging in open discussions and by mobilising collective decision-making with the staff. For months the two leaders became targets of staff resistance, anger and shouting; numerous sick leaves and resignations followed. One HS described the reaction of the personnel:

The staff were terrified at the beginning. They were afraid that they will die. They were dealing with rather heavy emotions. … I led many team sessions with the workers in the empty aula, not yet open to residents and discussed ‘how do we act here with the clients?’ ‘where do we sit?’ ‘what will happen here?’ We were practising sitting there … This lasted many, many weeks and there were moments when I started doubting that we could push it through. (HS2, interview)

When staff members were initially struggling to be in the same space with the residents without the plexiglass separation, one HS decided to spend time in the aula casually interacting with residents while eating her oatmeal. Her behaviour opened the possibility that other staff members, torn between the conflicting motives of sticking to the old control culture and the new way of working, might one day decide to meet a resident they were afraid of by asking if they wanted to have a cup of coffee in the aula. Step by step the practitioner might discover new professional capabilities and qualities in the resident. The seemingly insignificant bowl of oatmeal or cup of coffee becomes the kedge that hits the ground.

One of the housing counsellors explained the impact of this reorganisation of space:

I have noticed, although I have been here such a short time, that the clients have experienced a change. We are human beings to them; before we were faceless staff members … Now when we spend more time together in the aula, they notice things about us like ‘you look tired.’ Also, it is easier to take up issues with them and bad behavior has diminished. It is easier to shout at a person behind the glass than to a person with whom you clean and have coffee daily. These are big changes. (Employee, six months after the aula opened)

The guidelines for work in the aula were co-written with the personnel and HS1 kept updating them on a daily basis with suggestions from the staff. The document read ‘Instructions to be updated. Not final,’ and each update was printed and made available to everybody. Six months after the opening of the aula these instructions had transformed; they were much less detailed, and primarily emphasised that the staff had the power to take decisions and organise the work in the aula. Also the name of the document had changed to ‘Instructions for incoming gig workers,’ indicating that the regular staff no longer needed the document to operate in the aula.

Six months after the aula had opened, the personnel were making progress while still being uncertain about the extent to which they could exert their agency in the collective making of the unit.

They are still uncertain about what they can do at their own discretion because this had been a culture in which they had to ask permission for everything …. It is very important that both the visitors and the residents learn that everyone who is on duty has the power to make decisions. … They decide and they have the power. This is still something that they need to practice, that they have the power. The funny thing is that when I am not there everything is taken care of, but when I am here they turn to me. … In a recent Wednesday meeting we were discussing if a resident should be terminated. There were lots of different points of view and good arguments and the staff member whose personal resident this client was, her opinion counted very much. For the first time in my experience in this unit the staff unanimously decided not to terminate but just to give a serious warning. We could have ended up in a great disagreement. Typically in the past I had to make a decision because the staff could not reach a consensus. (HS1, interview)

Example 3: warping with the Change Laboratory in a supported youth housing unit

In a meeting with my research team, a former Senior Advisor of the Finnish Ministry of Environment mentioned a youth housing unit, referring to it as one of the most challenging in the country. This is the unit discussed in Example 2. The unit is in a well-off, politically conservative and centrally located neighbourhood and had frequently received negative press ever since its opening in 2012. Its clientele was considered the hardest to find housing for, due to criminal records, debts, substance abuse and mental health problems. The unit was staffed 24/7.

The research team contacted the unit to express its interest in collaboration with the help of the CL. HS1 described the demanding transformation process presented in Example 2. At this point the aula had been open for less than three months. Two months after this first contact, the research team was invited to visit the unit and present the CL idea during a staff meeting also attended by the NGO service director and HS1. The metaphor of a moving train emerged in the discussion, indicating the shift the transformation process was undergoing.

I have indeed opposed.

But you are now on the train (all laugh). You are on the train and not a single time you have put your foot in front of the wheels.

I am in the rear wagon! I am thinking whether I should pull the emergency break or not.

Some of us jump in and some of us will jump out.

And some are half way in (laughs)!

I have been working so many hours that I feel I am only half way in.

(Meeting fieldnotes)

The unit was still experiencing resistance as the reference by Employee 3 (E3) to ‘jumping out’ demonstrates. In fact, in the months that followed, further positions became vacant in the unit, including the position of E1 in the excerpt above. In the train metaphor the reference by E2 and E4 to being ‘half way in’ the moving train indicated a strong sense of uncertainty and risk.

Preliminary fieldwork for the CL started soon after the research team received a formal agreement from the unit to proceed, and lasted approximately two months. This fieldwork consisted of planning meetings with the NGO’s service director and HS, interviews with current and past personnel, and with current and past residents. Six CL sessions (CL1-6) followed every second week for three months. All sessions were attended by at least one of the unit’s heads of service and the NGO’s service director also eagerly participated in most of the sessions.

CL1 was attended by five practitioners. During this session, the researchers shared excerpts on problems and achievements from the interviews and these were interpreted collectively by the participants. In some of these excerpts safety was portrayed as a problem, while in others it was an achievement. This mismatch between the interviewees’ views on safety was indicative of the conflict of motives that was brought into the open in CL. Some of the employees explained in the sessions that although they themselves did not experience fear, they understood the fear of colleagues, due to the fact that they were accustomed to a way of working which established a safe boundary between them and the residents. In the discussion of safety that followed, the participants offered arguments that challenged the representation of the residents as a source of danger for the personnel.

The fact is that the one who shouts loudest is the one who is the most fearful. All the situations of shouting, or situations where someone is with a weapon, when one has spoken calmly, looked the person into the eyes and met the person – the weapon has been put down, the situation has been relaxed. Nobody has attacked. (E5)

And now I have observed that the residents defend us to a surprising extent. (E6)

When some resident is in an aggravated mood in the aula, other residents have now started to catch it and ask, ‘What’s wrong, tell us.’ (E5)

Also, the representation of the new space as a danger zone was contested by two employees who pointed to the multiple doors and exits ready to be used in case of threats. The need for cameras in the new space expressed by some was also heavily questioned by others as an instrument of control pertinent to the tasks of police but not to the staff tasks of a supported housing unit.

This discussion on the cameras led to a point when the participants concluded that the need for cameras was an indication of the need for control among the workers. This discussion crystallised the core conflict of motives in the unit between the old culture of control which meant that both employees and residents ‘followed the rules to the letter’ (E5) and the emerging culture of ‘trust,’ ‘flexibility’ and ‘discretion.’ The following statements by three employees towards the end of CL1 spell out that at this point the unit was seeking a way to collectively grasp the direction of the ongoing transformation. These statements represent search actions to move forward and away from the troubled area the transformation had generated in the unit.

Many people are very uncertain about where this is going. (E7)

It creates a heavy burden on us. We have to kind of prove that we are competent. (E6)

We have no ready-made model to build our activity on. We just do it. … And still we need to stand behind our own way of working and say ‘this is good’. (E6)

CL2 had a total of eight participants, three more than CL1. CL2 focused on reconstructing why and how the transformation had taken place and what had changed in the unit during the past year. Clips from the preceding session and from the interviews were shown and discussed. The participants returned to the big role fear played in the way personnel related to the transformation process.

HS recalled that two employees who had brought clients inside the information area were accused by colleagues of causing danger to others. It became apparent that this fear was facilitated by the top-down division of labour previously in place in the unit, which differentiated the tasks of the housing counsellors (‘the lowest caste’) from the tasks of the service counsellors (in charge of social welfare matters).

These two job descriptions corresponded to two ranks, the lowest being the one closest to the residents. The transformation process eliminated these ranks and required that all employees work collaboratively, on an equal footing and close to the residents, while also attending to administrative tasks. Since, for some employees these strict boundaries meant safety, their dismantlement generated insecurity and outright fear. To return to the metaphor of warping, these staff members felt as in the middle of a storm in the open sea.

The discussion also revealed that there had been a shift in the unit in recent years towards stricter safety measures concerning, for instance, the access to the residents’ homes. One employee told that he had received feedback from others that he could not go into a resident’s apartment by himself because of the risk to his safety. HS recalled an exchange she witnessed when an employee asked another employee to keep an eye on her through video surveillance all the time during her visit to a resident’s home.

Through this discussion on fear, the participants brought the residents to the centre of the CL deliberation. Before the transformation, the residents appeared to the personnel to be a distant and abstract entity. The NGO’s service director stated that the activity in the unit had been guided by ‘fear of the unknown, without even having facts about what was actually feared.’ A recently employed staff member pointed out that ‘a substance abuser does not stop smelling until it is your own child.’ To this employee, who had been himself a resident in a similar unit in the past, the old space arrangement in the unit appeared as if the personnel had no experience of people who might act under the effect of alcohol and drugs. In other words, the reinforcement over the years of strict boundaries and division of labour had strengthened the unit’s alienation from the residents’ lives.

The year of the transformation process in the unit was then represented with the help of a history wall, collectively constructed by the participants and the research team ().

Figure 5. Staff of the unit and a research team member (third from the right) constructing the history wall during CL2.

The history wall aimed at representing month by month what had happened and how it was experienced by the employees. At the end of CL2, the history wall was left in the unit and the researchers encouraged the staff to work on it further, to create a collective memory among the personnel by adding photographs and other documents that would tell about what it was like to live through the change. The history wall served as an extension of the CL sessions, bringing into the open the contradictions of the transformation process as they were experienced by the staff.

CL3 took place nine months after the opening of the aula, and the unit was still undergoing great changes and actively hiring new personnel. Contrary to the research team’s expectations, the session was attended by 12 practitioners, including a night shift worker. Furthermore, the history wall had been enriched with many photos and notes, and space was added for the next two months. The history wall had been moved from the meeting room to the entrance corridor where all personnel and visitors would easily have access to it. In the search actions the unit was initiating by means of the CL, the history wall was one kedge anchor that hit the ground.

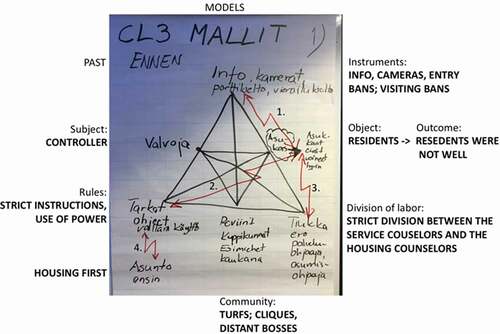

CL3 focused on modelling the work activity of the unit in the past with the help of an empty template of the triangular model of the activity system (Engeström [Citation1987] 2015, 63) drawn on a flipchart. The research team aimed at shifting from discussing the employees’ personal experiences to analysing the systemic relations within the unit. Each element of the activity system in the template was opened up step-by-step, showing videoclips from CL2 and from the interviews, and the participants were invited to name it. The agreed-upon names were written on the template on the flipchart ().

Figure 6. The triangular model of the activity system for the analysis of the past filled during CL3 – the elements of the activity system and translations from Finnish of the names given to the elements (bold, all caps) added to the photograph.

After naming the activity system elements, the participants were asked where in the model (within or between which components) they saw significant points that had created pressures for change and somehow rocked the system. The lightning-shaped arrows in represent these points. They illustrate that the past activity in the unit emphasised rules, instruments and a division of labour which turned out to be dysfunctional to respond to the residents’ needs. They enabled the residency of the tenants, but they did not allow the flexibility and support that would make it possible for young people to build skills for independent living.

Strict rules with the instruments in use were found to give rise to unforeseeable consequences for the lives of the residents (the object of activity), marked as contradictions with numbers 1 and 2 in . Strict actions such as visiting bans may have been taken for instance in order to help a resident avoid expulsion. E9 remarked, however, that such a ban was also applied to residents’ companions and therefore could interfere profoundly with the residents’ lives. This contradiction between the instruments and the residents is marked with number 1 in .

E4 explained that she was informed about safety measures during the orientation period after she was hired at the unit. Although she agreed on the importance of safety, she found that the way it was presented during the orientation was exaggerated. She therefore began working the way she had been working elsewhere, trying to take a resident’s point of view. This meant bending the rules and soon she got feedback that her way of working was not appropriate. She felt there was a continuous contradiction there. The strict division of labour did not support the well-being of the residents as it caused delays for instance in the filling of forms for social benefits. These contradictions are marked with numbers 2 and 3 in . The conflict of motives experienced by the employees became progressively apparent during the CL. This was a conflict between strict boundaries as safety measures and the residents’ wellbeing. The conflict of motives derived from systemic contradictions that had been consolidating over the years in the unit.

According to the NGO’s service director, the nationwide Housing First quality recommendations were in place in the unit, in the sense that ‘the autonomy of a resident was respected extensively. For instance, if a resident said, “I do not want to talk to you anymore”, he or she has been left alone. … A different kind of interpretation of the residents’ autonomy requires, however, taking a lengthy effort.’ This contradiction is marked with number 4 in .

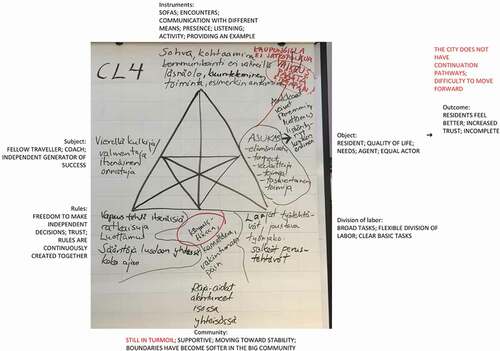

CL4 was attended by 11 practitioners, including four newly hired workers. The focus of this session was the modelling of the present activity of the unit and its ‘sore points,’ as well as the identification of the direction of future development of the activity. As a bridge to the preceding session, the research team had prepared a clip from the modelling of the past activity system and a slide displaying the jointly constructed model and its contradictions. At the end of CL3 each participant had received an A4 template with an empty triangle of the activity system to be filled by naming the elements corresponding to the current activity of the unit. In session 4, a model of the current activity system was collectively constructed by filling the template on a flipchart ().

Figure 7. A triangular model of the present activity system, filled during CL4 – elements of the activity system (regular italic) and translation from Finnish of the names given to the elements (bold, all caps) added to the photograph.

The residents and their lives and needs were named as the object of the current activity. A staff member who had just returned to the unit as a new employee told that, compared to the past, the residents now seemed to be treated as equals and were listened to by the employees. Furthermore, a staff trainee who used to be a resident herself in the early years of the unit told that that she felt that she was closer to residents and the residents were closer to the employees than in the past.

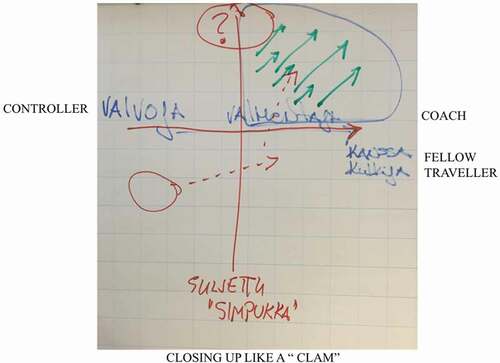

The subject of the activity was defined as ‘fellow traveller’, referring to the employee as a companion who walks along with the resident as long as the resident needs them. The notion of coach was used hand-in-hand with this. Both notions emphasise that the employee is not above the resident. The residents can make mistakes, have their say, to learn what they want, and make decisions. HS pointed out that this coaching ethos applied to the whole unit in such a way that anyone can fail, including the employees and the management, without running the risk of being judged and trusting that success will take place next time. E5 added: ‘It is like an expansion of perspective, expansion of experiences and of the range of action’. Within this perspective, the employee is an actor who has a mandate to generate successful initiatives independently.

Several core instruments were named in the template as shown in . E10 pointed out different means of communication, as for instance when he makes music with a resident and suddenly the resident begins to talk about other things such as his goal to drink alcohol only moderately. Different forms of communicating – music, painting graffiti in the yards, going to movies etc. – were therefore added to the template as instruments. Getting together with the residents, being present, listening to and providing examples were also added as instruments.

Figure 8. Four-field constructed during CL4 to chart the direction of change in the unit – translations from Finnish (bold, all caps) added.

As CL4 took place, the community was still under development and several participants pointed this out. Several new permanent employees had been hired, but they had yet to create a community (E11), and balance would be reached when all recruits were in place (E10). This was identified as one of the sore points of the current activity, marked with a circle at the bottom of . It became clear, however, that the unit had already started operating with an organic division of labour without strict and hierarchical boundaries between job descriptions: ‘Everyone does what they see best.’ (E5)

The participants agreed that, as outcome of the present activity, the well-being of the residents had improved. Trust had increased and this had lowered the threshold for the residents to turn to the employees with their needs and views (E5). This outcome was characterised as incomplete as some felt that many needs and requirements might be expressed at the same time (E6), some saw this as a side effect of tight resources (E5), or as the very nature of the activity of the unit (HS1). The incompleteness of the outcome was also seen to stem from a lack of continuation pathways in the municipality for residents who would be ready to move to independent living outside the unit after rehabilitation (E5). This was identified as yet another sore point of the current activity, also marked with a circle on the top of . HS crystallised this sore point: ‘We cannot make a telephone call that now we have a resident that would be ready to go forward. They do not say, “okay we begin to organise;” they say she or he is in the queue.’ (HS1)

After completing the analysis of the current activity, CL4 continued with the identification of the direction of future development of the activity with the help of a progressively constructed four-field representation ().

A long horizontal arrow without text was drawn on the flipchart with the left-hand end representing the past and the right-hand end representing the future. Participants were asked to name the way of working in the unit before the transformation process and the desirable way of working in the future. The points on this line of development were named and written down on the flipchart by one of the participants (E5).

A vertical arrow was then added on the flipchart, to form a four-field. Again, the text was added as result of discussion. As development is never linear, this vertical arrow allowed taking into consideration alternative directions and areas of possibilities. A video clip with an excerpt from an interview with the NGO’s service director was shown in which she pointed out the risk that the unit would ‘close up like a clam’ and isolate itself without productive interactions with the outside world. The vertical direction of change was identified as starting from this risk of enclosure heavily experienced by the unit, for instance due to the stigma associated with the residents. The vertical direction in extends to a direction which was later, in CL5, defined as ‘open catalyst’ (‘avoin vaikuttaja’ in Finnish). The notion of ‘open catalyst’ indicates that the staff and the residents will take deliberate steps to open up and influence relations outside the unit. The circle and the dotted arrow moving from left to right and slightly upward indicate the direction of development the unit was seen to be taking.

On the basis of this twofold direction of development, operating as fellow traveller and acting outwards, the research team asked the participants to start thinking about what would be the most important and promising pilot projects or spearheads (marked with several arrows in a row in the upper right field in ) for strengthening this defined direction – these would be discussed in the next CL session. This request to the participants was welcomed by HS1 who explained that these tasks aligned with the unit’s scheduled development day. This was an indication of a further movement forward in TADS in the CL. The four-field, constructed on the basis of the analyses of the past and present activity of the unit, was a kedge that started hitting the ground in session 4 and, as it will become clear in the following, continued doing so in CL5 and 6.

CL5 was attended by 13 staff, including a new employee who had just joined the unit. For this session the research team had prepared slides with the model of the current activity and its sore points and the four-field model produced in session 4. These slides were complemented with videoclips from session 4 in which participants named the elements of the triangular model and pointed at sore points in the activity. Also clips illustrating how the four-field came about in session 4 were presented. In session 5 the future end point of the vertical outward dimension was defined by the participants as ‘open catalyst.’ As the NGO’s service director stated:

We should go into the society. Not to give fine speeches but to increase the society’s understanding. We, our clients, could go to some fairs and present something. They are visible human beings, they are real people, just like everyone else … Because of this clientele, we easily become isolated here, and this isolation transfers from the residents to the staff, and to the management.

The session focused primarily on concretising the model and preparing for implementation. During the session the participants identified spearhead projects to take tangible steps towards the twofold future direction. 15 spearhead projects were discussed, named and recorded on a flipchart, with named employees taking responsibility and elements for an action and documentation plan for each project. Examples of these spearhead projects included the creation of a football team with staff and resident players to compete with other teams in the area; putting together a band to perform gigs; building a community kitchen open also to outsiders.

CL6 was attended by 13 employees. This session focused on preparing the first steps for the identified spearhead projects by planning signposts for their implementation. The session started with a brief overview by the research team of the progress made through the CL with slides and clips showing the models that were created and a list of the 15 projects. Then the spearhead plans in progress were presented for the majority of the projects by the participants, confirming the name of the spearhead, the key people involved, the timeline, and the most important events or situations to be documented for each project. HS made it clear during the session that all the projects would have carefully prepared plans and scripts for documentation. The research team shared the idea that, by means of these plans and documentation, all staff would know about the progress of all the spearheads which, together, would form a concrete perspective for the entire unit.

The plan for the community kitchen serves as an example. The employees responsible for this project aimed to produce a meal once a week for 70 people at the cost of 0,56 EUR per portion. Seven residents could be working in the kitchen at the same time with the initial support of two employees and later on only one employee. The participation of the residents was planned for every phase, from shopping to cleaning the kitchen and the dining area after the meal. Also the plan included the use of leftovers; for instance, leftover oatmeal would be would be used for making bread rolls. It was planned that the raw materials would come primarily through the usual donations to the unit, but also from negotiations with local shopkeepers. The kitchen stove was to be quickly delivered and the first meal arranged soon after that.

Employee 11 came up with the idea that the unit could suggest to the shopkeepers that, in exchange of donations of food, a resident from the unit could come and sweep the street in front of the shop. The NGO’s service director added that the residents be less likely to steal from a shop that donated food to their unit. E10 said that several shops had joined in the plan and that a meeting between the employee and the shopkeepers was scheduled to take place the following month. He added that one shopkeeper had suggested that some employees and residents could join him for a fishing trip and that some residents could come for two hours to work on bottle return.

At the end of CL6 the research team explained the follow-up sessions and gave framed pictures of the models created in the CLs to the unit’s heads of services to put them on the wall. Also the team reminded the participants that all the videos of the CL sessions were made available for employees to see if they had missed any of them. In fact, the team had noticed that often, when we arrived for the CL sessions, the meeting room was occupied by several new and old workers who were watching the previous CL session on video.

Discussion and concluding remarks

This article has argued that TA should be understood as a process, not merely as a capacity or property. The process view requires data and analysis that trace the process step by step, often over considerable periods of time (see Grant, this issue, for example). Furthermore, the process view requires an effort to model the mechanism that puts the process in movement and brings it forward (Vayda, McCay, and Eghenter Citation1991). This article suggests warping double stimulation as such a mechanism.

The three examples are all instances in which the search actions of throwing kedge anchors to find suitable ground were initiated. However, only when the kedge is hooked to the ground – that is, when the collective actually uses the second stimulus – does the crew gain control of the problem situation and become able to pull the vessel out of the stall. Such search actions may lead to taking-over actions and breaking-out actions.

In both the experiment and the work with clients in supported housing units, the participants turned to material means (the kedge anchor or second stimulus) to search for a suitable ground for gaining control over the problem situation and for breaking away from the troubled area. In Example 1, the suggestion by one participant to jointly write a note to be left on the table opened up a way for the two other participants to legitimise exiting the conflict of motives. In Example 2, practitioners working in housing units reported conflicts of motives which were overcome by means of agreements.

The demands set by a problem situation and conflict of motives may lead learners to combine multiple second stimuli in series. This is the case in Example 1 in which two second stimuli were progressively adopted and put into use: the question from one of the participants and then the written note. This is an aspect TADS which requires further investigation. However, it is clear that some problem situations require breaking out of established habitual or conventional patterns and acquiring new ones. For this, stand-alone cycles of double stimulation are insufficient and repeated implementations are necessary (Grant, this issue; Hopwood and Gottschalk, this issue; and Nuttall, this issue, also make this point). This was the case in Example 2 where multiple reiterations eventually led the client to clean his apartment without amphetamine.

The examples show how a collective can constructively break out of constraining and conflictual situations by means of anchoring forward movements, stepping into the unknown with constantly negotiated exploratory actions and artefacts. These anchors are instrumental for collectives amidst uncertainty creating new meaning which may be momentarily stabilised to further support TA. This type of movement can also be systematically supported by CL formative interventions, as shown in Example 3. The following excerpt from the end of CL1 crystallises the anchoring function the CL.

E11: To accomplish change, we need a bit more than just wanting it. Wanting it is not enough, we need also to establish support points here and there …

NGO service director: But wanting it takes you quite far. If you don’t have that, it won’t …

E11: Well, it is a big part of it, but we need much more. (CL1)

E11’s notion of ‘support points’ corresponds to potential kedge anchors such as the graphic models of . E11’s insistence that ‘wanting it is not enough’ makes it clear that support means are needed as something to build on. And his expression ‘here and there’ indicates that a complex collective change effort needs a variety of potential kedges or second stimuli materially distributed in space and time.

Examples 2 and 3 indicate that in a configuration of nested dynamics, individuals, collectives and organisations feed one another and this way strengthen the transformative movement forward. The specific connotation of the warping metaphor highlights the peculiarity of TADS as navigating treacherous waters. Gaining a momentum in such conditions requires distributed and multi-layered strength built one step at time to make the overall process robust.

The examples indicate that TA cannot be disconnected from the longitudinal processes of constantly developing activities and related expansive learning. Space does not allow elaboration on these aspects here. However, each of the examples shows how the very trigger of TADS – the conflict of motives – is rooted in historically evolving contradictions in activities. In Examples 2 and 3, TADS was embedded in and constitutive of long-term processes of expansive learning.

TADS and expansive learning do not easily fit the logic of temporally fixed projects. In Examples 2 and 3 the transformation started as an in-house ‘intravention’ (Sannino, Engeström, and Lemos Citation2016) before the CL entered the picture. It is also clear that the process will go on without a predefined end point. This presents the challenge of building sustainable researcher-practitioner partnerships that follow and support TADS dynamics in practice over the long term.

Example 1 presents another methodological challenge, namely that of intensity of detailed analysis of critical events. TADS emerged to a large extent in subtle and mundane steps of warping that can easily be overlooked. Identifying such steps and putting them under the magnifying glasses of fine-grained analysis of discourse and action is necessary (Goodwin Citation2018). Meeting these two methodological challenges will enhance both the practical societal impact and the scientific rigour of research on agency.

Acknowledgments

I thank the reviewers of the manuscript for their insightful comments and suggestions. I am particularly grateful to the participants in the experiment and to the practitioners in the CL for their time and collaboration. The data in Example 1 were collected in collaboration with Anne Laitinen. The data in Examples 2 and 3 were collected in collaboration with the RESET research team members Hannele Kerosuo and Yrjö Engeström.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of this research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Archer, M. S. 2003. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bandura, A. 1989. “Human Agency in Social-cognitive Theory.” American Psychologist 44 (9): 1175–1184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175.

- Barma, S., M. Lacasse, and J. Massé-Morneau. 2015. “Engaging Discussion about Climate Change in a Quebec Secondary School.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 4: 28–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.004.

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., and R. C. Reilly. 2017. “Immigrant Children Promoting Environmental Care.” Environmental Education Research 23 (4): 553–572. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1153046.

- Boyte, H. C., and M. J. Finders. 2016. “A Liberation of Powers.” Educational Theory 66 (1–2): 127–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12158.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What Is Agency?” The American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/231294.

- Engeström, Y. [1987] 2015. Learning by Expanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y.[1987] 2015. Learning by Expanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Engeström, Y., A. Kajamaa, and J. Nummijoki. 2015. “Double Stimulation in Everyday Work.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 4: 48–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.005.

- Goodwin, C. 2018. Co-operative Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haapasaari, A., and H. Kerosuo. 2015. “Transformative agency.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 4: 37–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.006.

- Hopwood, N., and B. Gottschalk. 2017. “Double Stimulation ‘In the Wild’.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 13: 23–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.01.003.

- Hutchins, E. 2005. “Material Anchors for Conceptual Blends.” Journal of Pragmatics 37 (10): 1555–1577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2004.06.008.

- Lund, A., and T. M. Eriksen. 2016. “Teacher Education as Transformation.” Acta Didactica Norge 10 (2): 53–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.2483.

- Marková, I. 2000. “Amedee or How to Get Rid of It.” Culture and Psychology 6: 419–460.

- Moscovici, S. 1983. “The Phenomenon of Social Representations.” In Social Representations, edited by R. Farr and S. Moscovici, 21–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nuttall, J., L. Thomas, and L. Henderson. 2018. “Formative Interventions in Leadership Development in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 16 (1): 80–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X16664555.

- Pleace, N., M. Knutagård, R. Granfelt, and D. Culhane. 2016. “The Strategic Response to Homelessness in Finland.” In Exploring Effective Systems Responses to Homelessness, edited by N. Nichols and C. Doberstein, 425–441. Toronto: Homeless Hub Press.

- Sannino, A. 2015a. “The Emergence of Transformative Agency and Double Stimulation.” Learning, Culture, and Social Interaction 4: 1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.001.

- Sannino, A. 2015b. “The Principle of Double Stimulation.” Learning, Culture, and Social Interaction 6: 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.01.001.

- Sannino, A. 2016. “Double Stimulation in the Waiting Experiment with Collectives.” Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science 50 (1): 142–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9324-4.

- Sannino, A. (2018). Counteracting the stigma of homelessness: The Finnish Housing First strategy as educational work.” Educação, 41 (3): 385–392 doi:https://doi.org/10.15448/1981-2582.2018.3

- Sannino, A., and A. Laitinen. 2015. “Double Stimulation in the Waiting Experiment.” Learning, Culture, and Social Interaction 4: 4–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.002.

- Sannino, A., Y. Engeström, and M. Lemos. 2016. “Formative Interventions for Expansive Learning and Transformative Agency.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 25 (4): 599–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty.” Science 185 (4157): 1124–1131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124.

- Vayda, A. P., B. J. McCay, and C. Eghenter. 1991. “Concepts of Process in Social Science Explanations.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 21 (3): 318–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/004839319102100302.

- Vygotsky, L. S. [1931] 1997. “The History of Development of Higher Mental Functions.” In The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, edited by R. W. Rieber, 207–219. Vol. 4. New York: Plenum.

- Y-Foundation. 2017. A Home of Your Own. Keuruu: Otava.