ABSTRACT

Gender bias in teaching materials may influence students’ development and contribute to social inequalities. This study investigates possible gender bias in a newly published English textbook series in Vietnam. Holding gender as a social construct, the research uses a multimodal critical approach to examine language and ideological systems. The results show despite some effort for gender equity, the making of textbooks in today’s Vietnam is still affected by patriarchal Confucian values. Males inhabit bigger verbal space and have more social properties. Females are portrayed as less independent; their choices are more limited, and with less resources. Textbook author interviews show the writing was influenced by conscious and unconscious bias, but they agreed gender equality is important, although male domination beliefs still seem to be deeply ingrained in the society. The study raises questions on challenging the status quo and creating a new cultural narrative for women’s rights recognition and enactment.

Introduction

Textbooks are materials of authority – the ideas, values, and perspectives embedded in textbooks are influential considering their potential large audience. Blumberg (Citation2008, 345) argues that gender bias in textbooks is an ‘important, near-universal, remarkably uniform, and quite persistent but virtually invisible obstacle on the road to gender equality in education – an obstacle camouflaged by taken-for-granted stereotypes about gender roles’. Investigating what certain kinds of language, persons and actions are being promoted or missing may reveal different discourses (ideas about the world) that factor in social practices (e.g. actions, processes, and rules) (Ledin and Machin Citation2018).

This research examines gender representation in English textbooks in contemporary Vietnam, trying to dismantle possible biases, subtle and sophisticated as they might be. Adopting social-cultural theories which suggest that gender is socially constructed, the study uses critical discourse analysis and investigates the ideology/discourse recognisable through its manifestation in linguistic ‘traces’ (Sunderland Citation2004, 7). The study asks questions about our notions of gender, to examine how or when the feminine or masculine is constructed as powerful, to explore genderedness (Jule Citation2018).

The story of gender equality never gets old. Gender is revealed in discourse: femininity (and masculinity) is socially constructed and continuously produced (Scharff Citation2013). Global patterns have shown that women still experience gender-related violence, discrimination in the workplace and public life, and more limited choice of partners and reproductive rights (Lips Citation2014; Mills Citation2012). These issues are largely impacted by cultural forces including societal norms, expectations, and restrictions (Lips Citation2014). In Vietnam, empowering women and girls so that they can reach their full potential has been promoted. However, with centuries of history and culture influenced by Confucianism – the ancient Chinese system of beliefs that emphasises male domination – ensuring girls’ and women’s rights remains a challenge for the country (UNFPA Citation2020).

Recent research conducted in various contexts such as Poland, Turkey, Sweden, Uganda, China, and Japan (Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland Citation2015; Li Citation2016; Carlson and Kanci Citation2017; Namatende-Sakwa Citation2018; Lee Citation2019), reveals a hidden curriculum of gender inequality in textbooks. This study provides empirical findings from contemporary Vietnam – a context still under-researched. In Vietnam, there have been several English textbook investigations but they do not focus on gender (e.g. Dang and Seals Citation2018; Nguyen, Marlina, and Cao Citation2020). The current study also provides perspectives from textbook authors, an angle not yet widely explored in prior research.

Using a critical multimodal analysis of both texts and their visual supports (Ledin and Machin Citation2018), the research explores how gender is represented in textbooks. Is there one group portrayed as the powerful one while the others are rendered invisible in the background or even missing? Is the portrayal of the roles, attributes, and behaviour of a group assigned with particular sets of characteristics? Examining these interwoven aspects – stereotyping, invisibility and imbalance/selectivity, helps raise important questions of power, prejudice, and inequality (Sadker and Zittleman Citation2007).

The textbooks analysed are a newly published English textbook series for lower secondary education (grades 6–9, students aged 11–15). The production of the new textbooks is among the measures within the ongoing National Foreign Languages Project (NFL Project), Ministry of Education and Training (MoET) (2008–2020, extended 2020–2025) to reform the country’s foreign languages education, mainly through curriculum revision; textbook development; teacher assessment, education and training; and facilities procurement.

Vietnam’s English textbooks

Textbooks in Vietnam, as in some other countries, e.g. Turkey and Indonesia, serve as the main instructional materials, mandated by the government. Therefore, until recently, ‘textbooks’ in public schools in Vietnam means a single and compulsory national textbook series produced by the Ministry,Footnote1 and school teaching is centrally planned via provincial Departments of Education and Training.

As part of the NFL Project, in 2012, a revised English curriculum for lower secondary education with content guidelines for each grade of 6, 7, 8, and 9, was approved (Decision 01/QD-BGDDT, MoET). Gender equality is not explicitly mentioned in the curriculum; however, in the content suggested for grade 9, under the theme ‘Visions of the Future’, there is a topic called Changing roles in society. The topic is elaborated as ‘Talking about male and female roles in domestic life’, and ‘Negotiating male and female roles in future domestic life’ (ibid., 30).

The textbooks for lower secondary education within the NFL Project were jointly produced during 2012–2016 by the Vietnam Education Publishing House and Pearson, written by a team of local English language professionals, male and female, including professors, teacher educators, school teachers, and language specialists from different parts of Vietnam, in collaboration with international reviewers and editors from Pearson. One of the researchers of this current study is a member of the writing team.

The textbook writing was based on the curriculum guidelines. Each Unit’s topic and its linguistic content were selected from the suggestions. The units were then written by individual authors, and sent to Pearson editors for several rounds of review and revision.

The series was piloted during 2012 in 30 provinces in Vietnam, with 88 schools, 184 classes, and 9,099 students (Hoang Citation2018). Since then, the series has been used by millions of students and teachers in public schools under the NFL Project in cities and provinces throughout Vietnam.

Gender as a social construct

From birth onwards we are repeatedly forced to respond to gendered norms and to act according to our gendered roles. These are ingrained in cultural, social, political and psychic life: we are gendered in and through repeated performance – we perform gender (Butler Citation1990). Gender is produced as performative effects of power: ‘[t]here is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very “expressions” that are said to be its results’ (Butler Citation1990, 25). Performances of femininity (and masculinity) do not refer to intentional enactments, but are done continuously, and through that, produce femininity (Scharff Citation2013). Gender can be constructed, produced, represented, and indexed (Sunderland Citation2004, 22, italics in original).

Concerning gender and power hierarchies, language and its intentions have been widely selected by social scientists as an analytical approach. Examining language critically in light of power relations thus enables us to go deeper, past the surface of everyday experience: tensions, contradictions or conflicts that otherwise may go unnoticed or seen as unproblematic reveal how power relations function (Jule Citation2018).

Studies conducted around the world have provided examples of gender representation in textbooks. Generally, they reflect discourses of ideologies, stereotypes, bias, and norms that still disadvantage women (e.g. Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland Citation2015; Li Citation2016; Carlson and Kanci Citation2017; Namatende-Sakwa Citation2018; Lee Citation2019). In Poland, men are represented in powerful positions while women are within the stereotypically feminine domain of appearance (Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland Citation2015). Similarly, in Uganda, women are constructed as obsessed with physical appearance; they are emotional, and dependant on men, who are the providers; these gender productions are rooted in traditional patriarchal beliefs of an agricultural economy (Namatende-Sakwa Citation2018). In contemporary Japan, where men are the breadwinners and women are expected to stay at home, textbooks reflect this ideology: men occupy more social roles, while women’s achievements are almost invisible (Lee Citation2019). Comparing textbook illustrations in China in different periods, Li (Citation2016) concluded that despite the government’s efforts at eliminating gender disparities, Confucian values were still present in the materials: Women continue to be portrayed as inferior to men. In Turkey, with a culture of ‘enemies’ and ‘defence’ that shapes masculinity around the concept of the ‘warrior-protector’, men are portrayed as the protector, while women are the object to be protected; women’s foremost role is being mothers even if they have some other social roles (Carlson and Kanci Citation2017). Similar findings were found in Sweden – a context often known for gender equality: women are absent as active subjects of the story; they can strive to realise their goals, but through the work of men (Carlson and Kanci Citation2017).

Indeed, stereotyping, invisibility and imbalance/selectivity are among the biases that possibly emerge in instructional materials (Sadker and Zittleman Citation2007). Stereotyping is the association of certain, often rigid, roles, traits, and behaviours with a particular group, and thus it may lead to an incorrect image of that group’s capabilities. Invisibility and imbalance/selectivity occur when a group is underrepresented or even excluded, which implies they do not have as much value and importance as other groups (Sadker and Zittleman Citation2007).

In the present study, the intertwined concepts of stereotyping, invisibility and selectivity/imbalance are discussed as themes to highlight different facets of gender depictions in the books. Is there a dominance of a particular group (e.g. girls vs. boys, women vs. men)? How are they presented? Is the portrayal of the roles, attributes, and behaviour of a gender group assigned with particular sets of characteristics? To what extent might this have been influenced by stereotyped norms and values?

The study approaches gender equality as the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men, and girls and boys (United Nations Citationn.d.). Gender inclusiveness is thus a democratic participation of individuals and groups in the society, in recognition of each particular group’s distinctive features, strengths, and capabilities, regardless of their sex. With this inclusive viewpoint, during the analysis, a non-gender specific perspective to feminist textual analysis (Mills Citation2012, 93) was adopted: the texts (and their visual supports) were scrutinised without a prior assumption that they simply portray women in a sexist, oppressive manner.

Vietnam: Confucianism and gender discourses

The distinctiveness of Vietnamese culture (in relation to Chinese culture) has been discussed by Vietnamese scholars (e.g. Mai Citation2014) reflecting attempts to reclaim a Vietnamese historical identity. Indeed, Vietnam was under China’s control for over one thousand years (111 BCE – 938 CE), and this has undoubtedly had lasting impacts, especially on people’s ways of thinking. Confucianism remains an ideology influential on social hierarchy and order, including family relationships.

Confucian countries (e.g. China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, Singapore) have lower gender equality (Grosse Citation2015). Vietnamese Confucian ideals of ‘men superior, women inferior’ hold that being a male is valued more than being a female. Men are the backbone at home and in society, and are associated with noble qualities and virtues such as ‘nhân’, ‘lễ’, ‘nghĩa’, ‘trí’, ‘tín’ (kindness, decorum, uprightness, wisdom, and trustworthiness). Meanwhile, women are seen from a functional perspective: they should have ‘công’, ‘dung’, ‘ngôn’, ‘hạnh’, which means they need to skilfully take care of housework, maintain a tasteful look, have manners, and practise loyalty. Men are perceived as being more intellectually and physically capable, while women’s life accomplishments are judged by their marriage. Men occupy public space while women’s ‘sphere’ remains the home. Even at home, the woman seldom has her voice heard: she is expected to obey her father, her husband, and then her son. Having a son is perceived to be better, as the son has the mission of family linage – passing down the family name, known as the logic of ‘patrilineality’ (Gupta et al. Citation2003). The son will be the one who preserves the family heritage and takes care of the parents, while the daughter will be married away (to serve her in-laws), so sons often receive more investment (e.g. in education). In this sense, girl babies are born, but they somehow do not exist, as seen in this saying, ‘You have one child if it is a son, but you do not have any child even if you have ten daughters’ (Nhất nam viết hữu, thập nữ viết vô).

During the 1960s until late 1980s, state-socialist ideologies influenced the national political agenda, this including advocating equal gender participation. This ideal has indeed helped increase women’s presence in economic and political domains. Vietnam is currently among the top 10 gender-equal countries in the Asia-Pacific region with regard to health, education, economic participation and political empowerment opportunities (World Economic Forum Citation2018). However, the present picture is still influenced by a narrative that depicts women as devotedly serving, and even sacrificing for, others. Promoting an ideal of the Vietnamese women who skilfully shoulder all responsibilities and excel in both public and domestic spaces, may at the same time mean existing norms and stereotypes against women are reproduced and reinforced.

According to UN Women, gender equality is yet to be achieved in Vietnam: women’s lower income, violence against women, domestic work burdens, and workplace discrimination against women remain (Hanoitimes Citation2020). The latest State of the World Population Report 2020 (UNFPA Citation2020) states that in Vietnam 40,800 girls could have been born every year, according to natural sex ratios at birth, but were not, because of biased pre-natal sex selection. Vietnam is currently among the countries with the highest rate of sex ratio imbalance at birth (in 2019, the rate was 111.5 boys per 100 girls), the main cause of which is ‘son preference’, rooted in Confucian values (VnExpress Citation2020). Confucianism is still a predominant ideology that disadvantages women in terms of gender attitudes (Grosse Citation2015), sex ratios, literacy rates, school enrolment rates, and years of schooling (Vu and Yamada Citation2020).

Materials and methods

Gender content in textbooks has been studied following a wide range of methods – content analysis, narrative method, visual study, critical linguistic analysis, frequency counts, and corpus-based study (e.g. Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland Citation2015; Li Citation2016; Namatende-Sakwa Citation2018; Lee Citation2019). Besides its contribution exploring the topic in contemporary Vietnam as a rather under-researched setting, regarding methodology, the current study provides findings using a systematic multimodal critical qualitative analysis, combined with quantitative analyses. Also, interviews with the textbook authors offered insights into the writing process, a dimension remaining largely underexplored.

To address the research questions (examining gender representation from a power dynamic perspective, by exploring possible bias regarding the three interwoven aspects – stereotyping, invisibility and imbalance/selectivity), the study adopts a critical perspective. Critical qualitative research seeks discursive understandings about social structures, power relationships, and challenges existing conditions with questions of positionality, representation, and the production of situated knowledge (Bhavnani, Chua, and Collins Citation2014). A multimodality view of text was chosen: Both text and images were considered as forms of communication that carry social meanings, and by looking closely at specific instances and asking what exactly is being communicated, and how it is communicated, the values and ideas being either foregrounded or backgrounded can be revealed (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 10, italics in original).

The data include four English textbooks (Student Book) of four levels of grades 6, 7, 8, and 9 (Hoang et al. Citation2017), and an interview with three textbook authors. Each textbook consists of 12 units and four review lessons. A unit is structured into seven sections: Getting Started, A Closer Look 1, A Closer Look 2, Communication, Skills 1 (Reading and Speaking), Skills 2 (Listening and Writing), and Looking Back and Project.

Getting Started was purposefully selected as unit of analysis, since it is designed to have higher impacts on teaching and learning compared to other sections. Getting Started occupies the largest space and content in each Unit, serving as the cover story that sets the ground for both the theme and language teaching points for the whole Unit. The section is presented as a conversation (of approximately 120–250 words, depending on levels) and its subsequent tasks. The conversation text alone is attractively designed as spreading over one or two pages with large graphic illustrations. Teachers are encouraged to use the illustration as an effective tool (e.g. to facilitate comprehension, generate ideas, support learning strategies, and increase motivation) (Teacher Book).

Altogether, the 48 Getting Started conversations and their accompanying illustrations from the four books create a multimodal pool of data of 48 units of analysis. All 48 units were analysed separately by each researcher, following a protocol comprising aspects of conversation analysis (e.g. Coates Citation2004): a) amount of contribution, b) the topics discussed, c) portrayal of roles (females and males), and d) speech acts/transactivity (e.g. as an information-provider or an information seeker/receiver). Findings from the textual analyses were corroborated with the accompanying illustrations. The results were then gathered and discussed by both researchers.

The study draws largely on qualitative analysis, while quantitative information was used as a supplementary source for interpretation, and was discussed in connection with qualitative data. Character contribution in each conversation was triangulated from different sources: appearance of male and female characters, their participation in the conversation (same-sex or mixed), and turn-taking. Emerging patterns were accordingly interpreted into themes, discussed within the broader gender-related social cultural discourse of Vietnam. Each gender’s contribution (or lack thereof) in certain topics, the way they talk, and the depiction of their roles and characteristics reveal not only their participation and identities in verbal discussions, but also their participation, identities, and voices in the society in general.

The study chose not to focus on intersectionality aspects, including race (Vietnamese characters vs. foreigner characters), and age – and thus status (children characters vs. adult characters), nor did it look specifically into the interaction between same-sex speakers.

To complement the textbook analysis, a group interview was conducted with three authors of the series. The interview was an informal conversation where the authors were informed about the research and their consent was sought. Two of them were female and one male. All of them had considerable experience as language experts, researchers, and/or educational specialists, and had been working extensively with the writing and production of textbooks. In the interview, the authors were asked about how they had considered gender issues in writing the textbooks, how they thought gender equality should be defined, and how possible it might be to bring gender equality into the textbooks and the classroom.

Ethical considerations

As one of the researchers is also one of the textbook co-authors, extra reflexivity was considered. The researcher’s familiarity with the series writing processes facilitated the sense-making of the data, including data from the author interview because they were relatable to the researcher. Meanwhile, factors that may lead to conflicts of interest were identified in order to be mitigated: the relationship between the researcher and her subject of inquiry (the researcher investigating and/or critiquing her own co-products), between the researcher’s different professional roles (researcher vs. textbook writer), and between the researcher as a member of the writing team and the team itself.

Throughout the study, the researcher and her co-researcher, who is not involved in the textbook writing, ensured that the data were dealt with in fairness and with research ethics. All the contents from the textbooks, including the Units written by the researcher herself, were treated purely as research data. The data were analysed systematically following the protocol, and they were examined according to the research aims, questions, and theoretical framework, independent from factors that may lead to possible conflicts of interest earlier identified.

Results and discussion

Space taking: who is present? Who does the talking?

The 48 Getting Started conversations revolve around 23 children (10 girls and 13 boys), and 13 adults (9 women and 4 men) (), making 19 female and 17 male characters. Nevertheless, how much verbal space is taken up by each gender may not be reflected in these figures, because it depends on the frequency of their appearance in the conversations.

Table 1. Characters presented (in order of appearance).

In terms of characters’ presence in the talking, of the 48 conversations, 29 (60.4%) are mixed (both genders), 15 (31.3%) are same-sex, male, and 4 (8.3%) are same-sex, female (). In two books (English 6 and English 8), there is no female same-sex conversation. That 60.4% of the conversations involves both genders seems to be a positive indicator of gender equality. However, of the remaining 39.6%, same-sex conversations between females happen less than those between males. This means the overall presence of females (68.7%) in all conversations is less than that of males (91.7%). This finding is supported by a count of appearance of child characters (protagonists), with boys significantly surpassing girls (72 vs. 40, ).

Table 2. Gender participation in conversations.

Table 3. Children characters’ (protagonists’) appearance.

Not only are males more prominently present, they also dominate the conversations, as shown from the number of turns and turn lengths (). Males’ turns outnumber females’ turns almost two to one (423 turns – or 63.8%, versus 240 turns – or 36.2%). Regarding turn lengths, males spoke 5,172 words (63.1%), and females 3,026 words (36.9%).

Table 4. Turn-taking and turn-lengths (words).

Power hierarchies: Who can talk about what? And how do things get said?

The representation of males and females was approached quantitatively above. This section provides an in-depth analysis of their portrayals and participation from a qualitative perspective. Overall, stereotyping, invisibility, and selectivity/imbalance bias could be detected in the textbooks.

The upper-room sitting mat?

As mentioned earlier, a slightly larger share of the conversations (60.4%) involves both genders. This reflects a general attempt to level the playing field. However, an overall exploration suggests that boys/men still predominate in most areas. As presented earlier, males take much bigger talk space than females, in terms of participation, turn-taking, and turn-length. This means they talk about any topics under the sun. The topics are also deemed more important, problematic, and more socially influential. In particular, the 15 conversations in which only boys/men are present (same-sex conversations) cover science-technology, space, and the future (English 6 – Unit 10, coded as 6–10; English 6 – Unit 12, coded as 6–12; 9–10), travelling (8–2; 8–5; 8–8; 9–2), leisure time (6–7; 7–4; 8–10), keeping fit (7–2), the past (8–6; 9–4), and social issues such as economy, education, overpopulation and natural disasters (7–12; 8–9). In comparison, the 4 conversations that feature female characters only (8.3%) are about the past (7–6), travelling (9–5), how one goes to school (7–7), and choosing school subjects (and future career paths) (9–12). Overall, boys/men dominate both the space and the content of the conversations, while girls’/women’s involvement is limited.

The findings can be related to the Confucianism-influenced belief that women are intellectually inferior to men – they do not have the capability required to discuss important issues, and thus should be ‘sitting on the lower-room sitting mat’. Men should be sitting on ‘the upper-room sitting mat’ – they are eligible to talk about things that women cannot.

Occupational roles: Territories fenced?

There are 13 adult characters in the four textbooks, and often they are not the protagonists. However, examining their occupational roles reveals their participation in social realms, and this may implicitly impact how learners see their own possibilities in the future. Of the nine women, three are depicted as mothers; the remaining six work as a TV/radio talk show host (3), a school teacher (2), and a museum guide (1). The numbers for occupational roles are quite small; however, scrutinising them still offers some gender insights. The four men are introduced as Dr. (2) (in natural sciences and technology) and a school teacher (1), and a father (1). The three school teachers are seen in social sciences lessons (festivals, customs and traditions, and English), and two of them are female. The museum guide was seen at the Museum of Ethnology. As such, women are still depicted mostly in stereotyped ‘feminine’ professions (school teacher in social sciences, guide). In contrast, although men have started to ‘break the barrier’ to ‘women’ occupational spaces (as seen with the school teacher who teaches English), regarding STEM – science, technology, engineering, mathematics, men still dominate: both of the jobs in technology and natural sciences belong to men. Men also enjoy a higher professional status: there are two mentions of the title ‘Doctor’, and in both, the title is possessed by men. The zero presence of females in these particular displays might reinforce the existing mindset that STEM is men’s territory, while women’s space is within ‘soft’ disciplines. More importantly, that the textbooks fail to include women regarding further education possibilities and qualifications (with the highest degree possible of a PhD) reflects the (still) common belief in the Vietnamese society that women cannot, and should not, pursue higher education, especially post-graduate education. Li (Citation2016) also finds that in textbooks in China, men are more often seen holding powerful and prestigious occupations than women, which is related to Confucian values.

Domestic roles: Where is the father?

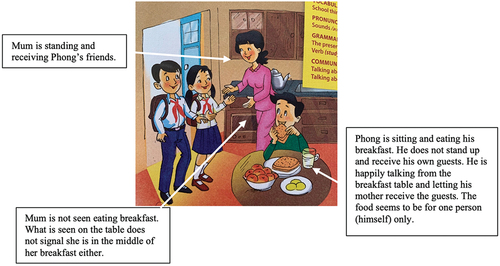

In the 48 Getting Started conversations, the mother appears four times (6–1; 7–5; 7–6; 9–7), while the father only once (9–4). All the mothers are in the home setting: three in the kitchen (6–1; 7–5; 9–7), and one in the living room (7–6). They all play the role of the main caretaker. In 6–1, the illustration shows Phong’s mother in the kitchen with a kettle on the stove (). She is standing and receiving Phong’s friends, while Phong himself is sitting at the table eating breakfast.

As such, when parents are introduced, in most cases it is the mother and the mother is depicted as the main caretaker. There is little information that may suggest that the mother can also be imagined in a different light (for example, their professional lives, their own hobbies and interests, etc.).

In contrast, the father is given a brief appearance – in only one conversation (9–4). During the time when all the housekeeping and childcare happen, the father is completely absent. In another story (9–11), although the information about her family situation is not clear, Mai mentions this absence, ‘I don’t see much of my dad, but I love every moment I spend with him’. The father’s child caring was mentioned only in passing, and only in three conversations – the characters say they receive advice from their parents (9–3), and from their father (9–5; 9–12). In the only conversation featuring the father (9–4), he is not seen in a home setting doing housework; rather, he is ‘preserving the past’ by giving his son (Nguyen) a kite, passing on family traditions and heritage to him. Also, his concerns (preserving heritage) seem to have a more noble meaning; they do not revolve around cooking, shopping, or packing – things typically reserved only for women.

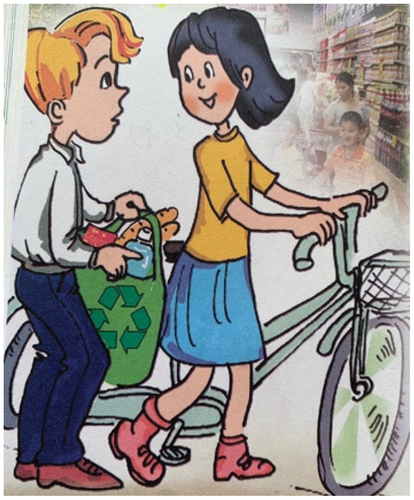

When it comes to children doing housework, the picture, however, seems to be brighter, with two conversations including boys shopping for groceries, and cooking (6–11; 9–7). In 6–11, Nick runs into Mi at a supermarket, illustrated by Nick holding a shopping bag full of stuff – a sight still rarely seen among men and boys in Vietnam ().

Nevertheless, in both 6–11 and 7–7, boys are introduced together with girls. In other kitchen scenes in the books (6–1; 7–5), boys do almost no chores – their mothers do that for them.

Overall, considering all the household scenes, females are always associated with domestic roles, while males, especially the fathers, are almost absent. This reflects the stereotype believing men’s space is in the society, and that of women is in the kitchen, taking care of the family: Reproductive responsibilities and care- and house-work are seen as obvious duties of women, which resonates with other research (Carlson and Kanci Citation2017; Lee Citation2019).

Who is the expert/ambassador?

The transactivity analysis suggests that males are portrayed more often as an expert/ambassador – one who provides information about a country, a culture, a city/place of interest, and a subject area (most notably in 6–5; 6–6; 6–9; 6–11; 6–12; 7–3; 7–5; 7–6; 7–10; 8–2; 8–5; 8–6; 8–11; 9–2; 9–4; 9–5; 9–7). The ’ambassadors’ show their knowledge of the topic by answering questions, explaining, informing, or educating others.

Meanwhile, females have fewer opportunities for this representative role. In 7–3 (Community service), one girl and one boy are invited to a talk show to tell about their volunteer work, and the presence of both genders in this celebration, is important since it reflects their voice, involvement, and impact on a larger social scale. Apart from that, females act as the expert/ambassador in five stories (6–5; 7–6; 7–10; 9–5; 9–7), being the information-providers. In two of these stories it is girls who are dominant in STEM topics (6–5: geography; 7–10: energy).

Males, by contrast, are depicted as the source of expert knowledge and information in 11 (of 17) stories. For example, in 6–6, Phong is on an international talk show telling about Vietnamese New Year’s traditions; in 8–2, 8–5, and 8–6 Nguyen and Duong explain about Vietnamese legends, traditions, crafts, and festivals. Even though females participate in discussions on science and technology, the area is dominated by males. Of the 16 characters in the 6 conversations on technology (6–10; 6–12; 7–11; 8–11; 8–12; 9–10), 12 characters are males. Girls seem to act as equal interlocutors in only two conversations (7–11; 8–12). In their research, Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland (Citation2015) also found that while both men and women are depicted as expert in some areas, overall, women still occupy a symbolically feminine sphere (e.g. shopping, magazines, fashion).

Males are also the ambassador even of a generation (9–4). The earlier analysis of Nguyen’s and his father’s conversation (9–4) shows that men are excluded from doing housework, but it also reveals their special status representing generations, and family continuation.

This is a present for you, son.

A kite! How cool! Thank you, dad.

I made it for you, just like your grandfather used to make one for me.

Is it a family tradition?

Yes, for generations.

, Unit 4)

Even if it is not clear from the context if Nguyen’s father is the only child of his grandfather, or Nguyen is his father’s only child, it is obvious that only men are in focus. Nguyen’s family tradition of making kites down generations seems to be reserved for men only (Nguyen’s grandfather, Nguyen’s father, Nguyen), while the women of the family are completely invisible. The ambassadors of the past and of the future – who have the noble mission to keep the legacy alive, are men. Nguyen and his father’s story proves the logic of ‘patrilineality’ – men have the noble mission of passing down the family name, while women are excluded from the picture.

Who has the savoir-vivre?

A recurrent image of the boy characters constructed in the books is of a (world) traveller. Boys are present in 13/15 conversations that involve travelling, 9 of which are between boys only, or mixed but with boys as the protagonists. Meanwhile, girls are underrepresented on these fronts. Boys are depicted as curious, keen travellers who have the chance to go to different places in Vietnam (6–4; 7–1; 8–2; 8–5; 8–7; 9–1). They also visit countries around the world, from Brazil, France, to Singapore, Japan, and Australia, just to name a few (6–9; 7–12; 8–5; 8–8; 9–2; 9–8; 9–10). If there is someone cherishing the dream of travelling, it is a boy (6–5; 7–1; 9–10). Girls, conversely, appear in only four as doing, or have been doing, some travelling (7–6; 8–7; 9–1; 9–5). It is also remarkable that girls’ travelling is much less far-reaching: they only travel within Vietnam: two cities (7–6; 9–1; 9–5), and a village (8–7; 9–1).

Not only are boys projected in the books as travellers who go far, they are also those who enjoy a rich life full of different activities. Boys’ interests and leisure pursuits spread over a wide range of options (besides travelling): television programmes (6–7), sports and games (6–8; 7–12; 9–3), painting (6–10), robots (6–12), nature (6–10; 9–8), art galleries and concerts (7–4), dogs (6–3; 8–1), climbing mountains (7–1), museums (8–3; 9–10), science clubs (8–11), learning new languages and cultures (8–1; 8–8; 9–1), cinema and films (7–8; 8–10; 8–12), and space and collecting rocks as hobbies (9–10).

By contrast, girls’ pastime are mentioned with less frequency and also in a more limited range of choices (besides travelling): sports and motion (6–8; 7–7), cinema and films (7–8; 8–10; 8–12), museums (9–5), craftwork (8–1; 9–1), collecting dolls and glass bottles (7–1), and science clubs (8–11). It is striking that girls are absent from many settings of pastime, leisure and entertainment. Instead, they are projected as more hardworking – (e.g. in 6.2, girls work on school projects during the evening; in 9.3, Mai stays up late studying for exams).

In addition, the portrayal of girls’ and boys’ interests and hobbies seems to noticeably reflect stereotypes. Although girls appear in several scenes involving sports and motion (6–8; 7–7; 9–3), boys are depicted as sport lovers. Boys do judo, karate, football, table tennis, badminton, cycling, swimming, while girls are only mentioned as doing cycling and badminton. In 6–8, even if Mai (girl) likes going to the gym, she admires Duy (boy) for being fit, and she actually tells him ‘I’m not good at many sports’. This stereotyped association between males and sports in textbooks has also been noted in earlier research, for example, in Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland (Citation2015).

More ‘manly’ interests such as mountain climbing, space, robots all belong to boys, while more ‘girly’ ones such as crafts and dolls belong to girls. In 7–1 (My hobbies) especially, some quite strong remarks about gender norms can be found.

Nick [talking to Elena who collects dolls and Mi who collects glass bottles]: I don’t know why girls collect things. It’s a piece of cake.

Do you have a difficult hobby, Nick?

Yes, I enjoy mountain climbing.

(English 7, Unit 1)

What Nick says, though in a joking tone, shows stereotyped thoughts about what counts as ‘real’ hobbies (e.g. his own hobby of mountain climbing). What girls do (collecting) is easy ‘(piece of cake’), which boys do not do. His comments reveal gender expectations and restrictions for both girls and boys.

Who dares to dream?

The books give opportunities for both girls and boys to imagine and plan their futures. Four (of eight) Getting Started conversations in Visions of the future theme happen between both genders (7–11, 8–11, 8–12, 9–11). Nonetheless, boys still have more voice in this respect. Of the remaining four conversations, which are same-sex, three are between boys (6–10; 6–12; 9–10), and only one between girls (9–12). Boys are also more assertive in expressing ambitions, dreams, and aspirations. They specify what they would like to do in the future (6–5, 6–10, 7–1, 9–10). In 6–5, Phuc says, ‘I want to visit Ayres Rock one day’, and in 7–1, Nick claims, ‘In the future, I’ll climb mountains in other countries too’.

The girls’ only conversation about the future, (9–12), however, is quite notable. Veronica and Nhi talk about their future school subjects. Not only are they knowledgeable about the topic (explaining how different school systems work), they also seem to be confident about their choices over their schooling, higher education, and future career paths. Moreover, STEM is explicitly mentioned as providing opportunities for girls.

Nevertheless, overall, girls show less independence, and have fewer resources for being independent than boys. In the books, boys not only dream high, but they also assert ways to actually realise their dreams. Even something as far away as outer space seems not too distant (e.g. in 9–10). In 8–8, Phong attends a summer camp in Singapore; and in 9–2, Duong visits Sydney and asks about the universities there. Meanwhile, girls do not have these resources – they are simply absent from these conversations. In other words, agency is taken away from girls (Carlson and Kanci Citation2017).

Roles changing?

As mentioned earlier, the textbook writing followed the curriculum guidelines, and the Getting Started in Unit 11, English 9, the very last book of the series, deals with the topic of changing roles in society. The story is set as a talk show (Beyond 2030 forum) with three students (Phong, Nguyen – boys, and Mai – girl) being invited to share their visions of the future. The first half of the conversation is about roles in society in general, and towards the second half of the conversation, the discussion on gender roles begins:

…

Fascinating. How else do you see the future, Nguyen?

Well, I think the role of fathers will drastically change.

Oh yes? In what way?

The modern father will not necessarily be the breadwinner of the family. He may be externally employed or he may stay at home to take care of his children.

And do the housework?

Yes. It’s work, paid or not, isn’t it?

Absolutely. The benefit will be that children will see their fathers more often and have a closer relationship with them. I don’t see much of my dad, but I love every moment I spend with him.

(English 9, Unit 11)

There are many good things about this first, and only, conversation, where gender roles are discussed explicitly. Those speaking up (Nguyen, Mai) are students/teenagers (rather than parents/adults), who, to the learners of the textbooks, may become role-models. The discussion (father’s changing roles) is initiated by a boy (Nguyen), and then contributed to by both genders (Nguyen and Mai). Expressing their views about how fathers’ roles will change, or should be changed in the future, also means the speakers highlight at the same time the social norms towards men/fathers that exist in the present (men are expected to be the breadwinner and not to stay at home taking care of children and doing housework). When Nguyen says, ‘Well, I think the role of fathers will drastically change’, and that ‘The modern father will … ’, he is also implying the current image expected of fathers is far from the future visions that they are talking about; but that image is not ‘modern’, and needs to be changed.

While the conversation tackles important issues of gender roles and succeeds in encouraging breaking gender stereotypes, it seems, however, to have failed to depict the struggles that mothers are having. The conversation focuses on father’s roles and fights for father’s rights, which is needed. However, this ultimate concentration on the father’s rights protection can also mean the mother’s contributions and rights are downplayed. The absence of the mother from the discussion may also send a message that their roles are unimportant. Nguyen’s statement, ‘The modern father will not necessarily be the breadwinner of the family’ is supposedly meant to lessen the financial responsibility burden on men, but it, paradoxically, implies at present, women contribute little to the family’s economy – a fact which is questionable. More importantly, the implication that women are, and are expected to be, dependent financially, may also mean they should have less authority in the family. Also, that the father’s contributions to domestic duties such as childcare and housework (in the future – which has not even happened yet) should be recognised and celebrated is foregrounded, whereas the fact that it is the mother who is doing all the duties (now, in the present) is not mentioned. This in fact may raise a question about how women’s contributions are undervalued, and even imply a double standard: women’s doing housework is taken for granted, while if the work is done by men, it is advocated as paid work. Failing to focus on the struggles that women are facing now, and failing to acknowledge women’s roles, might have adverse impacts on women’s liberation and empowerment.

Textbook authors’ insights

During the writing process, gender was not a focus. Author 2 seldom paid attention to this issue at first, and it ‘came as natural’ when designing an exercise with 5 sentences, she would use the subject he four times, and she only once. Author 3, meanwhile, said she was somewhat aware of how he and she was decided, but he or she was ‘a habit, a natural act’. For example, the author chose she to go with cook, but he to go with play sports.

I often use he rather than she as the subject who does strong actions – ones that need being done with a lot of strength, energy or navvy work. (Author 3)

Authors attributed this unconscious habit to being rooted in Vietnamese culture, which ‘always sees females as the weaker sex and one of their main responsibilities is cooking for the family’. However, they said although they were still affected by this, their awareness of gender had increased during the writing process. During the later phase, as the team looked at some instances in some units where Pearson editors suggested, for example, replacing the images of some famous men by those of women, Author 2 started to consider gender issues. She now tried to use roughly the same numbers of he and she, and male characters and female characters. Similar to Author 2, Author 3 became more self-observant, letting more female characters take part in sports or do the work traditionally done only by men.

Regarding their own definition of gender equality, Author 3 said it means equal opportunities for everyone in the society, ‘but how each person makes use of those opportunities greatly depends on their characteristics, preferences, and their living and learning environment’. Author 2 agreed with Author 3:

Gender equality means both sexes have same rights and responsibilities. If there are certain jobs, fields, in certain times and places, they should be given to those of more capability or those who will thrive in those conditions, regardless they are male or female. (Author 2)

In discussing whether conveying the concept of gender equality to students is possible, Author 3 stated that lower secondary school students, and even primary school students, can be made aware of gender equality in an indirect way.

For example, we can include female football teams besides male football teams in the text. Although children may not be fully aware of what gender equality means, by looking at the pictures and reading the texts or sentences in which females are presented in important positions, they will gradually realise that if one has talent and determination, they can be in high positions, regardless of their sex. (Author 3)

Author 2, while agreeing with Author 3, was concerned whether teachers would see subtle gender messages and convey them to students, because most usually try to cover language skills and other explicit contents. Author 1 agreed with Author 2, adding the textbook authors had to prioritise the topics’ content, vocabulary, grammar, and culture, rather than gender issues. However, if it appeared there were too many male turns in one dialogue, or items with only or almost all male characters, then this would be considered problematic and revisions would be made for a more balanced gender representation.

All three authors, while acknowledging the needs for incorporating gender content in English textbooks, thought the textbooks may not be the only main factor influencing students’ thinking. Author 2 said breaking gender norms in the textbooks should happen gradually so students ‘will not be shocked and resist to change’. Author 3 talked about teachers’ role, saying when using textbooks, teachers should also notice and highlight other content, for example, intercultural aspects. The authors suggested raising gender awareness through clearer notes in Teacher Books, and in teacher training workshops. Textbook authors themselves, they added, also need to pay closer attention to gender bias during the writing process.

The interview indicates that gender was not a priority during the textbook writing. External factors (having to juggle with other textbook content priorities) and internal factors (authors’ own conscious and unconscious gender biases) explain the lack of gender manifestations in the textbooks. The authors’ approach to introducing gender into the textbooks was still largely geared towards a mechanical, quantitative presence of men and women (e.g. number of female vs. male characters, number of turns), rather than a critical, qualitative perspective that focuses on possible power hierarchies (e.g. gendered attributes, roles, and behaviour). Also, gender was mostly seen as a subject area separate from other elements (topic, vocabulary, grammar, and even culture), rather than practices constructed via everyday social interaction and embedded in ideologies. More subtle and sophisticated manifestations of gender bias seem to go unrecognised or are considered normal. In other words, how women are presented was not considerably taken into account (Namatende-Sakwa Citation2018). Nevertheless, the input from Pearson editors, even if it was emergent rather than systematic, acted as an awareness-raising trigger for the authors, facilitating their efforts in introducing gender equality in the books. The interview also reveals the prevalence of patriarchal values in contemporary Vietnamese society at large, as seen in authors’ concerns about how teachers and students would react to any changes.

Conclusion and implications

The findings have provided insights into how gender is produced by language and discourse (Sunderland Citation2004) in contemporary Vietnam. The books’ depiction of gender, despite encouraging signals regarding gender equality, is still affected by gender norms and bias ingrained in Confucianism ideology, amid a general gendered discourse that disadvantages women seen elsewhere in the world. Both girls and boys are present in private and public realms, and most notably, girls start to appear in more STEM conversations. However, boys and men still predominate across different aspects of ‘being present’. They occupy larger verbal space and play more dominant conversational roles. Males are selected to be the expert (e.g. sports, science, cultures, family legacy). They are curious and ambitious; they enjoy abundant life opportunities, aim high, and dare to dream. Although boys start to be seen more doing some housework, it is mostly mothers and girls who are associated with caretaking and other domestic duties, while the father is largely absent from this sphere. Overall, females are less visible. Women’s societal contribution and professional success, and even their roles and voices in the family, are not sufficiently recognised and included. The depiction of girls still mirrors stereotypes: Not only are girls expected to be in certain ways (e.g. having girly, easy hobbies), they are depicted as less capable and independent; their choices are more limited, and they receive less development resources than boys. The interview with the authors suggests that the writing was influenced by both conscious and unconscious bias.

The findings echo what earlier research has revealed: there has been some progress towards gender equality in textbooks, but overall it remains insufficient. For example, Lee (Citation2019) found that, in textbooks in Japan there was use of gender-neutral language and an equal distribution of female and male speakers; but overall, women were underrepresented; and stereotyping was prevalent. Pakuła, Pawelczyk, and Sunderland (Citation2015, 56) describe the findings in their Polish context study as ‘patchy’: some books showed evident progress in portraying men and women as equal, but others were still influenced by stereotypes.

Gender biases, both conscious and unconscious, against girls and women in instructional materials has implications for girls’ empowerment and advancement, especially in a context with patriarchal traditions such as Vietnam. Meanwhile, bias against boys and men deprive them of their rights (for example, to learn life skills such as cooking; and to practice fatherhood). The existence of bias may all negatively influence students’ affective and cognitive development (Lee Citation2019) and contribute to social inequalities (Kereszty Citation2009). When presented in instructional materials, these biases can lead learners to form or reinforce limited views of particular gender groups, which can lead to stereotyped expectations and even discrimination.

However, the study also suggests that it is not impossible to challenge the status quo. The findings provide particular content in the books where a level playing field starts being constructed, for both females and males. The study shows even though gender perceptions may be grounded in long-lasting cultural ideologies, with awareness raising input, and if some gender equality basics already exist, perceptions can be changed and then translated into actions. As stated by the authors, their ideas of gender equality became clearer especially later in the writing process. The Getting Started in Unit 11, English 9, ‘Changing roles in society’, though still containing some limitations (as shown earlier), can still be regarded as a watershed in attempts to reimagine gender roles in some textbooks.

Awareness-raising and attitude-changing have been identified as essential in tackling gender-based issues (e.g. Chowdhury et al. Citation2018). The findings of this study can be used to inform the production, not only of the textbooks explored here, but also other textbook series. For the textbooks analysed, as part of the process of publishing coursebooks (Tomlinson and Masuhara Citation2018), a review of the completed series and a post-use evaluation could be conducted by the writing team and the publisher. Gender bias needs to be recognised, identified, and reacted to, both in terms of texts and images. Given the influential roles of textbooks, authors may even consider subverting ideologies (Butler Citation1990) not only by reflecting the status quo, but also advocating for what could be for gender equality in Vietnam, especially if changing norms might be perceived as challenging. Gender content can also be included in higher level policy including curriculum and educational regulations. In this case, that gender roles was suggested in the curriculum is one important step closer to gender equality, but gender could also be embraced throughout the teaching topics (and hence instructional materials). Gender mainstreaming (Lombardo Citation2013) – informing all public policies so they counter gender bias in society, can also be enabled. Gender thematic training could be provided to actors including textbook writers, producers, teachers, and administrators. The role of teachers in addressing the gender challenges needs to be recognised and supported too. Both awareness-raising and pedagogical tools in working with gender could be provided so that teachers not only detect possible gender biases in textbooks, but also enact their agency in using textbook mandates to invite students to the gender equality discussion and realisation.

Notes on this article

This article is developed from the following report: Mai Trang Vu & Pham Thi Thanh Thuy (2020). Gender bias in English textbooks in Vietnam: Textbook representations, teacher perspectives, and classroom practices. Project report Grant No HJ-127EE-17, National Geographic Society. http://www.diva-portal.org

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on the earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The revised Vietnamese Education Law (June 2019) stipulates that schools can from now on choose their own textbooks series within the national curriculum, provided that the series has been approved by the Ministry of Education and Training and the Provincial People's Committee.

References

- Bhavnani, K., P. Chua, and D. Collins. 2014. “Critical Approaches to Qualitative Research.” In Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by P. Leavy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blumberg, R. L. 2008. “The Invisible Obstacle to Educational Equality: Gender Bias in Textbooks.” Prospects 38 (3): 345–361. doi:10.1007/s11125-009-9086-1.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge.

- Carlson, M., and T. Kanci. 2017. “The Nationalised and Gendered Citizen in a Global World–Examples from Textbooks, Policy and Steering Documents in Turkey and Sweden.” Gender and Education 29 (3): 313–331. doi:10.1080/09540253.2016.1143917.

- Chowdhury, I., H. Johnson, A. Mannava, and E. Perova. 2018. “Gender Gap in Earnings in Vietnam: Why Do Vietnamese Women Work in Lower Paid Occupations?”. Policy Research Working Paper, No. 8433. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Coates, J. 2004. Women, Men and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language. 3rd ed. Harlow: Longman.

- Dang, T. C. T., and C. Seals. 2018. “An Evaluation of Primary English Textbooks in Vietnam: A Sociolinguistic Perspective.” TESOL Journal 9 (1): 93–113. doi:10.1002/tesj.309.

- Decision 01/QD-BGDDT, Ministry of Education and Training. 2012. English Language Curriculum for Lower Secondary Education (Pilot). Hanoi: Ministry of Education and Training.

- Grosse, I. 2015. “Gender Values in Vietnam – Between Confucianism, Communism, and Modernization.” Asian Journal of Peacebuilding 3 (2): 253–272. doi:10.18588/201511.000045.

- Gupta, M., J. Zhenghua, L. Bohua, X. Zhenming, W. Chung, and B. Hwa-Ok. 2003. “Why Is Son Preference so Persistent in East and South Asia? A Cross-country Study of China, India and the Republic of Korea.” Journal of Development Studies 40 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1080/00220380412331293807.

- Hanoitimes. September 21, 2020. “Vietnam Advances Greatly in Gender Equality, but Remains Far from Full Equality: UN Women.” Retrieved from http://hanoitimes.vn/vietnam-advances-greatly-in-gender-equality-but-remains-far-from-full-equality-un-women-314263.html

- Hoang, V. V. 2018. “MoET’s Three Pilot English Language Communicational Curricula for Schools in Vietnam: Rationale, Design and Implementation.” VNU Journal of Foreign Studies 34 (2): 1-25.

- Hoang, V. V., T. C. Do, K. D. Le, C. N. Phan, M. T. Vu, Q. T. Luong, Q. T. Nguyen, Q. K. Luu, and D. Kaye. 2017. Tieng Anh 6, 7, 8, 9. Hanoi: Vietnam Education Publishing House and Pearson.

- Jule, A. 2018. Speaking Up: Understanding Language and Gender. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kereszty, O. 2009. “Gender in Textbooks.” Practice and Theory in Systems of Education 4 (2): 1–7.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis: From Theory to Practice. London: Sage.

- Lee, J. 2019. “In the Pursuit of a Gender-Equal Society: Do Japanese EFL Textbooks Play a Role?” Journal of Gender Studies 28 (2): 204–217. doi:10.1080/09589236.2018.1423956.

- Li, X. 2016. “Holding up Half the Sky? The Continuity and Change of Visual Gender Representation in Elementary Language Textbooks in Post-Mao China.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 22 (4): 477–496. doi:10.1080/12259276.2016.1242945.

- Lips, H. M. 2014. Gender: The Basics. London: Routledge.

- Lombardo, E. 2013. “Gender Mainstreaming.” In Gender: The Key Concepts, edited by M. Evans and C. H. Williams. London: Routledge, pp 112-117.

- Mai, T. 2014. Đi Tìm Tổ Tiên Việt (In Search of the Vietnamese Ancestry). Hanoi: Vietnam Culture Studies Publisher.

- Mills, S. 2012. Gender Matters: Feminist Linguistic Analysis. London: Equinox.

- Namatende-Sakwa, L. 2018. “The Construction of Gender in Ugandan English Textbooks: A Focus on Gendered Discourses.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 26 (4): 609–629.

- Nguyen, T. T. M., R. Marlina, and T. H. P. Cao. 2020. “How Well Do ELT Textbooks Prepare Students to Use English in Global Contexts? An Evaluation of the Vietnamese English Textbooks from an English as an International Language (EIL) Perspective.” In Asian Englishes, 1–17.

- Pakuła, Ł., J. Pawelczyk, and J. Sunderland. 2015. Gender and Sexuality in English Language Education: Focus on Poland. London: British Council.

- Sadker, D. M., and K. Zittleman. 2007. Gender in the Classroom: Foundations, Skills, Methods, and Strategies across the Curriculum. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Scharff, C. 2013. “Femininities.” In Gender: The Key Concepts, edited by M. Evans and C. H. Williams, 59–64. London: Routledge.

- Sunderland, J. 2004. Gendered Discourses. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tomlinson, B., and H. Masuhara. 2018. The Complete Guide to the Theory and Practice of Materials Development for Language Learning. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- UNFPA. 2020. “State of World Population 2020.” Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA_PUB_2020_EN_State_of_World_Population.pdf

- United Nations n.d. “Gender Equality.” viewed February 18 2021, https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/gender-equality/

- VnExpress. December 19, 2020. “Vietnam to Have 1.5 Million More Men than Women by 2034.” Retrieved from https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-to-have-1-5-million-more-men-than-women-by-2034-4208486.html

- Vu, T. M., and H. Yamada. 2020. “The Legacy of Confucianism in Gender Inequality in Vietnam”. MPRA Paper No. 101487. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/101487/

- World Economic Forum. 2018. “Global Gender Gap Report 2018.” Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf