ABSTRACT

In Britain, ‘super-diverse’ communities, where children navigate multiple cultural repertoires, are increasingly prevalent. However, Reception teachers are pressured to ensure children, aged four and five, conform to a narrow conception of ‘school-readiness’. Research demonstrates children in multicultural contexts construct a ‘third space’, bridging their home and school discourses. This research shows how opportunities for third space creation are inherently tied to the nature of physical space, and its concomitant social expectations. It is argued that complexity in super-diverse communities can be harnessed and embraced, rather than reduced. Data presented were drawn from a year-long collaborative ethnographic study of children in a Reception class in the north of England. Children co-created cartoons, collaborating with the researcher in interpreting the data. Significantly, findings indicate that teachers can incorporate the third space as an alternative lens through which to understand and meet the challenges of teaching a linguistically and culturally diverse student cohort.

Introduction

In Britain, ‘super-diverse’ communities, such as the site of this research, are becoming increasingly prevalent (Vertovec Citation2006) with this trend continuing since the 1990s (Vertovec Citation2013). The term ‘super-diversity’ means the ‘diversification of diversity’ (Vertovec Citation2013) encapsulating the dynamic interplay of variables that characterise the make-up of a community, such as channel(s) of migration, legal status, human capital (e.g., level of education, access to employment, transnational connections, level of civil integration), and responses by local authorities, services providers and local residents (De Bock Citation2015; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011; Vertovec Citation2007). The existence of super-diversity is well established, however, ‘understanding the implications of this remains topical and relevant’ (Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015, 6). With this in mind, the aim of this paper is to add to the existing body of knowledge on the pedagogical implications of super-diversity, by looking at how children in a super-diverse, Early Childhood Education (ECE) setting engage with the learning of new topics by creating a ‘third space’ to connect home and school discourses. According to Soja, ‘Thirdspace [note the difference in spelling] is a meeting point, a hybrid place, where one can move beyond the existing borders …’ (Citation2009, 56).

The aim of this paper is, therefore, to demonstrate how different spaces, and the socially produced rules that govern them, have a profound impact on the potential for the creation of a third space. Finally, this paper will present the case for a ‘third space pedagogy’ in which teachers can harness children’s creativity in the third space and use it as a pedagogical approach.

The data presented in this paper is drawn from a twelve-month investigation of the communicative practices of young children in a super-diverse Reception class in a school in England through their transition into Year One. The aim of the broader project was to explore how the intersections between different socio-cultural contexts contributed to children’s multimodal communicative practices in a super-diverse environment, however the findings and discussion in this paper relate to a subsidiary question within the broader aim: What is the relationship between the cultural-institutional contexts of communication and the resources children draw upon to communicate in a super-diverse environment?

The context: early childhood education in England

In England, The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) is the Department for Education’s guidance that ‘sets standards for the learning, development and care of your child from birth to 5 years old’ (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2017). When children reach the age of five, they must attend compulsory schooling in Year One and follow the National Curriculum. The academic year immediately prior to Year One is known as ‘Reception’. Most children in England, aged four to five, go to Reception in a primary school, even though it is not compulsory. During their year in Reception the children are, in many ways, treated as pupils. For example, typically they will wear the school’s uniform; they will have lunch in the dinner hall with other year groups and play in the same playground. Pedagogical approaches in Reception support children’s learning through a mixture of play-based exploratory activities and a more formal, teacher-led model, as this paper will demonstrate.

The EYFS sets out a number of Early Learning Goals that children need to meet in order to achieve a ‘Good Level of Development’ (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2020). In recent years, ECE has been under increasing pressure from the government’s school inspection arm, the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) to make children ‘school ready’. Roberts-Holmes (Citation2019) explains that the concept of ‘school readiness’ sets out performance standards against which children in Reception classes can be measured in order to asses if they are ‘ready’ for Year One. However, one result of this school readiness agenda is that it pressurises Reception teachers to focus on preparing children for school, rather than the year being a separate entity – with appropriate aims – in its own right (Moss Citation2012; Kay Citation2018; Roberts-Holmes Citation2019). Furthermore, the EYFS constructs what is ‘normal’ and children who deviate from the developmental expectations are perceived to be ‘abnormal, pathological and in need of intervention’ (Prout Citation2005, 50).

Another outcome of the goal-oriented approach to Reception provision is the impact of school readiness on play. It is widely accepted that play is the cornerstone of learning and development in early childhood (Wood Citation2010), however in the UK, policy frameworks such as the EYFS create versions of play that align with performance goals (Wood Citation2015), rather than play for its own sake. This is revealed in OFSTED’s publications, for example Teaching and Play in the Early Years: A Balancing Act? (2015) draws play into the discourse of goals, outcomes and standards (Wood Citation2019). Similarly, Bold Beginnings (2017) prioritises reception year’s role in preparing children for learning, with a strong emphasis on direct teaching (Kay Citation2018).

The following section argues that these issues in contemporary policy can be addressed by paying attention to communication from a sociocultural perspective and third space theory.

Literature review

Communication and sociocultural theory

According to sociocultural theory, all forms of communication, such as spoken language, are mediating tools. Vygotsky (Citation1978) employed the notion of ‘mediation’ to explain how people are active agents with the capacity to choose tools and control how they are used, rather than a deterministic stimulus-response model of human behaviour. The use of tools permits people to transfer ‘psychological operation to higher and qualitatively new forms’ and ‘to control their behaviour from the outside’ (Vygotsky Citation1978, 49, emphasis is original). This explanation emphasises an individual’s agency to control their development, but also concedes that the mediating tools available to a person are influenced by their sociocultural context (Daniels Citation2016). These ideas are reinforced by Rogoff (Citation1995) who underlines the dynamism of learning and development, where cognition is not simply a collection of static entities transmitted from one person to the other. Rather, Rogoff argues that learning is active and comes about through participation in cultural practices, which in turn shape the practices for the next person to learn. Furthermore, ‘communication presumes intersubjectivity’ (Rogoff Citation1990, 67), a mutual understanding of an activity which is dynamic, context-related and develops as a result of interactions (Matusov Citation1996; Garte Citation2016). In this way, individual development, social interaction and cultural activity are interrelated and cannot be separated (Rogoff Citation1990).

In terms of communication, communicative resources are not simply static elements that exist objectively, but rather, people control the words, style, register or code of what they are saying, according to their intentions (Gumperz and Cook-Gumperz Citation2005). In a similar approach to Rogoff’s notion of dynamic learning and development, Bakhtin (Citation1975) holds that: ‘Prior to this moment of appropriation, the word does not exist in a neutral, impersonal language …, but rather exists in other people’s mouths, in other people’s contexts, serving other people’s intentions; it’s from there that anyone must take the word and make it one’s own’ (Bakhtin Citation1975, 293–4).

Thus, a particular communication is inextricably linked to the context of that communication; however, the notion of context has two facets. The first is the communities of practice to which the communicator belongs. The home, the family, peer groups, the local community, popular culture and digital communities, and the school are all examples of communities of practice where a child accumulates ‘cognitive and cultural resources’ (Moll et al. Citation1992). Thus a child will draw on these funds of knowledge to make sense of novel situations and choose how to act, or what mediating tools to use in a particular situation (Gonzalez, Moll, and Amanti Citation2005).

The second important facet of ‘context’ is the immediate context in which communication occurs. There is a dialectical relationship between social and spatial structures, meaning that ‘social practices produce space just as space produces social practices’ (Jones et al. Citation2016, 1129–1130; Soja Citation1989). The existence of different spaces within educational settings has attracted the attention of researchers who are interested in understanding how the structure and physical layout of a school impact upon children’s experiences and behaviour. Such studies draw attention to how indoor spaces, such as classrooms and dinner halls, are associated with high levels of surveillance and control (Gallagher Citation2010; Giddens Citation1984; Kernan and Devine Citation2010; Pike Citation2008). Researchers have observed the ways in which children’s lives and their communicative practices are profoundly shaped by the characteristics of the particular spaces they occupy (Gallagher Citation2010; Kraftl, Horton, and Tucker Citation2012). While many studies demonstrate how children regulate their own behaviour according to the immediate context, it is important to note that such research has also revealed ways in which children resist the rules and boundaries imposed by spaces (Corsaro Citation1988; Fashanu, Wood, and Payne Citation2019; Pike Citation2008).

The following section continues this notion of resistance to conformity by exploring the concept of the third space.

Third space theory

Throughout the collection of data underpinning this research, it was clear that children were frequently operating in the ‘third space’ – a fluid, flexible, multi-layered territory that bridges different communities of practice. The concept of the third space originates from the work of Lefebvre (Citation1991) who argued that, beyond the physical features of the space and the planners’ intended use of the space, a space is lived, experienced, changed and appropriated by its inhabitants. Bhabha (Citation1994) applies the concept of ‘third space’ to the liminal spaces in which members of diverse communities collaborate, leading to transformative interactions. Bhabha (Citation1994) names this process ‘hybridity’ and he speaks of the necessity to ‘focus on the moments or processes that are produced in the articulation of cultural differences. These “in-between” spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood-singular or communal- that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself’ (Bhabha Citation1994, 2).

Subsequently, the concept of third space has been successfully used to explore the intersections and disconnections between discourses in the home and community, as well as those of official institutions, such as schools. For example, Moje et al. (Citation2004) demonstrate how the funds of knowledge which Latino students amass from participating in activities at home shape their engagement with school discourses in the United States of America. Similarly, Levy (Citation2008) demonstrates how young children’s constructions of themselves as readers are formed from their integration of home and school experiences. In a similar vein, Yahya and Wood (Citation2017) show that the third space is a place where children from diverse backgrounds can bridge home and school contexts to make sense of the differences between the various communities of practice to which they belong, and thus for young children, play is an important vehicle for third space creation (Yahya and Wood Citation2017).

Importantly, a key feature of the third space is that individuals interact in ways that maintain their identities and resist forces of homogenisation in hierarchical organisations. This can be seen in Wilson’s (Citation2000) study, which revealed how prisoners chose to remain ‘maladapted’ to the institutional discourse of the prison. In doing so, they retained aspects of their own identities, and their outside lives. Similarly, Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda (Citation1999), who highlighted how communication in the official spaces of the class was in line with the sanctioned, legitimate curriculum. However, they also demonstrated that communication in unofficial spaces was characterised by ‘counterscript’ language practices which explored the tensions between the students’ personal experiences and the expectations of their school.

A final, and most important aspect of the third space, is that it is more than just a sum of its parts, rather ‘it is a place for transformation and creativity and it helps to illustrate the newness of what is created’ (Waterhouse et al. Citation2009, 6). This has been demonstrated by Cole (Citation1998) who explores ‘hybrid subcultures’ in which ‘new forms of activity are created that “re-mediate” social rules, the division of labour, and the way in which artefacts are created and used’ (Citation1998, 303).

The following () summarises the key characteristics of ‘third space’.

Table 1. Characteristics of the ‘third space’.

Previous research has established these features of the third space, as summarised in the table above. The findings presented below illustrate how children use the third space creatively to navigate the dissonances between home and school cultural discourses.

Methodology

This article draws on data that was gathered in responses to the following research question:

What is the relationship between the cultural-institutional contexts of communication and the resources children draw upon to communicate in a super-diverse environment?

Though the research was focused upon children’s communication, the third space became a prominent theme as it is a vehicle for children to communicate in ways that deviate from the expected conventions within the school setting. This question was explored from an interpretivist stance, accepting that we interpret our perceptions of the world through a dynamic meaning system that is continually negotiated with others through a socially and culturally situated framework of meanings (Hughes Citation2001). Thus, the researcher recognised ‘children as the primary source of knowledge about their own views and experiences’ (Alderson Citation2008, 287) and the research was designed to enable the perspectives of the participants to be heard.

Participants and data generation

The research took place over a period of twelve months, beginning at the start of the summer term and ending at the end of the following spring term in an inner-city school that is located in the Northern part of England. The researcher spent an average of two days a week with one class and followed the children as they moved from Reception into Year One. The thirty participants, aged four and five in Reception, then five and six in Year One, were all members of this class for some or all of the study. The school was chosen because of the super-diversity of the children not only in the class that was studied in depth, but throughout the school.

For example, the thirty children in this study came from, or had close familial ties to, fifteen different nations, and whose members migrated to the United Kingdom through five different channels: study, work, European Union membership, family connections or asylum seekers and who spoke fourteen languages other than English.

The bulk of the data was generated from ethnographic observations, where the researcher spent a sustained period of time immersed in the class’s everyday experiences, observing, listening and asking questions of its members (Bryman Citation2012). In this respect, it is important to note that a guiding approach underpinning the research project was to position children as competent and capable individuals, who are experts on their own lives (Alderson Citation2008). Thus, in order to listen to the children’s perspectives, the researcher adopted elements of Campbell and Lassiter (Citation2014) ‘collaborative ethnography’ that emphasises the process of deliberate collaboration with the participants. To achieve this, the researcher’s written observations were translated into simple cartoons, using the children’s self-portraits to transform the text into a format that was accessible for 4-6-year olds as children become ‘fluent’ in drawing from an early age (Anning Citation2004). Visual modes of communication, such as cartoons, also provide opportunities for ‘a rich, multilayered and mediated form of communication’ (Christensen and James Citation2008, 160). Though the process of creating cartoons was time-consuming, the benefits of were worth the effort as, importantly, the cartoons stimulated enlightening conversations around the content of each observation and led the researcher to gain deeper, more nuanced insights into the events depicted (Lundy, McEvoy, and Byrne Citation2011).

In terms of ethics, the project paid close attention to both ‘procedural ethics’ and ‘ethics in practice’ (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004). With regards to the former, the researcher obtained informed consent from the parents and carers of the participants. Two parents did not consent to their children’s involvement and as a result their children were not included in the study. The researcher also asked the children for their personal consent. This was important as the project was focussed on listening to the children’s perspectives on events, conversations, etc., and therefore it would have been hypocritical not to do so (Graham, Powell, and Taylor Citation2015).

Furthermore, in order to protect the children’s identities, participants were invited to choose their own pseudonyms (which led to some interesting choices, such as ‘Darth Vader’!) and to draw their own self-portraits. In terms of ‘ethics in practice’, the researcher viewed consent not as one single act preceding data collection, but as an ongoing and sometimes fluctuating negotiation between the researcher and the participants (Bourke and Loveridge Citation2014). As such, the researcher continually paid attention to signs that indicated a child’s discomfort, even if it was a small gesture such as putting their hand up to shield their activity from view. In such instances, the researcher respected the child’s wishes, and did not record their actions.

Data analysis

The data was analysed using an interpretivist framework, drawing on aspects of constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2006) and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The two theories are essentially compatible (albeit with some procedural differences), therefore the researcher selected and blended elements of each process to create a coherent method of data analysis, guided by the principle of ‘fitness for purpose’ (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011). The resultant large volume of qualitative data gathered was organised into themes through an iterative process of memo writing, coding, developing ‘centrally organising concepts’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), further data collection and the refinement of the themes. The broader research project’s aim was to investigate the intersections between different socio-cultural contexts and how these contribute to children’s multimodal communicative practices in a super-diverse environment. Three broad themes were constructed in relation to this overarching aim of the project: content of communication; communicative resources and contexts of communication. The following data relates to the latter of these themes.

Findings

Within the significant breadth and volume of data captured, the subsequent analysis revealed a spectrum of spaces in the school, ranging the most formal: ‘sitting on the carpet in silence’, to the most informal: ‘free play in the playground’. The data revealed that the diversity, complexity and creativeness of the children’s interactions increased as spaces provided them with more choice, flexibility and opportunity to initiate their own actions. This is depicted in the following () graph albeit it is not asserted that the relationship between the two variables is linear.

It also became apparent that the greater the scope for child-led activities, the more complex their interactions became and, crucially, the more frequently and deeply children operated in the ‘third space’. The following examples are taken from the different spaces in reception classroom as they can be compared directly, given that they occurred in the same room.

On the carpet

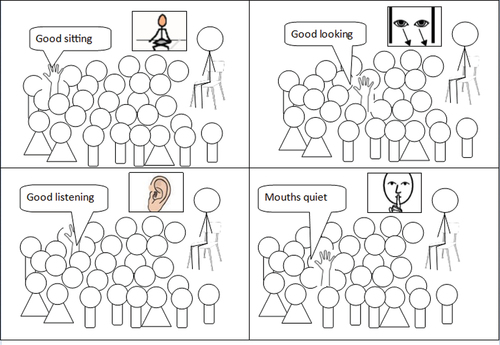

At the front of the reception classroom was ‘the carpet’, a space for all the children to sit and look either at the teacher, who sat on a chair at the front of the carpet area, or the interactive whiteboard behind the teacher. Almost all lessons began with ‘input’ on the carpet, where the children sat and listened to the teacher who introduced the lesson’s topic. Behaviour on the carpet was governed by the ‘fantastic four rules’ that were reinforced daily, as the following vignette () depicts.

The structure of communication that occurred on the carpet typically followed a question and answer format that was controlled by the teacher, as demonstrated by the following example () taken from the summer term in Reception.

In this episode, the teacher posed a question and anticipated a range of responses. Ali and Elsa then broke into a spontaneous conversation, discussing whether or not mud and grass are halal. Their responses were beyond the scope of expected, acceptable answers with the result that the teacher asked them to stop calling out, and the lesson swiftly moved on.

On the carpet: discussion

Throughout the data collection, lessons on the carpet exemplified ‘Assembly-Line Instruction’ (Rogoff Citation2014, 70), where the teacher controlled all aspects of the children’s behaviour:

Their physical posture was controlled as they were ordered where and how to sit.

Their cognition was restricted, as they were instructed what to think about.

Their communication was constrained, as they had to raise their hand and be granted permission to speak.

Their contributions were acknowledged or dismissed by the teacher, depending on their perceived relevance.

In the above vignette, the teacher began by asking the children questions to which she already knew the answer. Their interaction followed a ‘question-answer-further question’ model which Rogoff, Mejia-Arauz, and Correa-Chavez (Citation2015) call ‘known answer quizzing’. The vast majority of communication on the carpet throughout all of the data collection followed this format which, according to Rogoff, Mejia-Arauz, and Correa-Chavez (Citation2015), is the dominant didactic method in Western classrooms.

The rigid format of the interaction, compounded by having to raise a hand to speak, prohibited the children from entering into a fluid, exploratory questioning of the topic. For example, in the above vignette, Ali raised an interesting question about mud and grass being halal which indicated that he was integrating his knowledge and understanding of the world with the concepts being taught in this current lesson. Similar to the students in Moje et al.’s (Citation2004) study, Ali created a third space to bridge funds of knowledge acquired at home in order to engage with the current topic he was learning at school. Elsa latched on to Ali’s exploration of the concept of ‘halal’ and drew on her understanding to challenge Ali’s conjecture that mud and grass are not halal. However, the teacher did not perceive Ali and Elsa’s discussion to be relevant, so the unfurling third space was then immediately quashed. It is possible that, while sat on the carpet, the children were internally connecting their funds of knowledge to the topic, however the opportunity to fully explore such connections was stunted given that the ‘majority of [third space]’s practices are interactive in nature’ (Wilson Citation2000, 61) whereas carpet-based teaching is designed to minimise interactions.

In summary, sitting on the carpet and obeying the ‘fantastic four rules’ afforded the teacher maximum surveillance and control over the children. The resultant interactions were stilted and turn-based between the teacher and the child she selected to speak next. The content of the children’s contributions had to fall within a narrow scope of expected responses, otherwise they were disregarded. This vignette highlights the social-spatial dialectic (Soja Citation1989) and depicts a well-researched phenomenon, namely that formal spaces produce strict controls over communication (Gallagher Citation2010; Giddens Citation1984; Kernan and Devine Citation2010; Pike Citation2008) and inhibit third space creation (Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda Citation1999).

The following two vignettes, emanating from the research and their accompanying discussions, highlight moments of connection in the third spaces that come about in different physical locations thereby underlining the relationship between space and the social practices.

At the tables

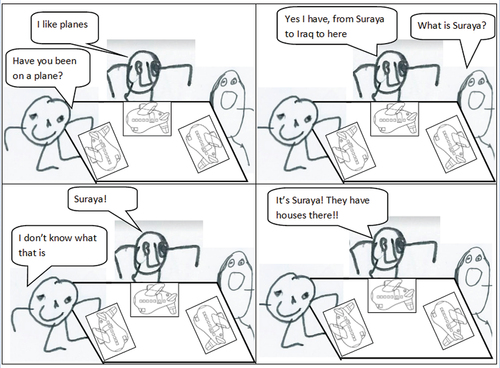

After a short ‘input’ on the carpet to introduce the topic, the children were then put into groups to complete set activities at different areas around the classroom. The children in the following vignette () had been set the task of colouring in aeroplanes.

In this vignette, Arman Ali and Roger, both from Pakistani backgrounds, are sitting with Issa, a refugee from Iraq who had come to England less than six months before. As the children draw, Issa recalls his recent journey on a plane from his home town, Suraya. As the conversation develops, Arman Ali and Roger say they do not know what Suraya is, which prompts Issa to give more detail.

At the tables: discussion

To recall, when the children were sat on the carpet, any contributions that fell beyond the scope of the immediate task were deemed inappropriate and dismissed immediately. By contrast, when children worked at the tables, they were allowed to speak to each other, quietly. The difference in expectations of acceptable behaviour in each of the spaces meant that conversations that would have been prohibited on the carpet were allowed at the tables. This highlights the importance of looking at spatial factors and recognising their profound impact on the social activity that a space produces (Jones et al. Citation2016).

The children’s conversations during set activities at the tables often began with the topic at hand, then meandered away from this, as they shared anecdotes about experiences they had engaged in with their families, communities or even in other countries. The recounting of out-of-school events, inspired by the topics they were learning, were commonplace and demonstrate how children bring their funds of knowledge into conversations surrounding the activity they were attempting to complete (Moje et al. Citation2004; Moll and González Citation1994). Making these connections served to bridge home and school discourses, helping them to develop a deeper understanding of new concepts by embedding them in previous experiences. In this instance, a static, two-dimensional picture of an aeroplane stimulated Issa to recall being on a plane and that a plane is a vehicle that transported him from his home town in Iraq all the way to Sheffield.

The vignette takes an interesting turn when Roger asks what Suraya is and Arman Ali confirms he does not know either. At this point, Issa becomes agitated and passionately defends his claims about Suraya being a town with houses. By linking the current task to thoughts about his past, Issa is maintaining his identity (Gee Citation1990), and becomes defensive when Arman Ali says he doesn’t know what Suraya is. This indicates the personal significance of the town where he grew up, and his reluctance to give up that part of his identity, despite living in a new place (Wilson Citation2000). Above all, Issa’s agitation reveals a seed of resistance to those who query the legitimacy of his out-of-school experiences, beyond Sheffield and his current circumstances (Gee Citation1990).

Analysing this, and many similar exchanges that occurred throughout the year of data collection, through a third space lens reveals that even though the children were physically sat at the tables in the Reception classroom, they simultaneously occupied an additional layer, the third space, as evidenced by their frequent bringing of out-of-school experiences into conversations within the in-school practices as a means of making sense of unfamiliar concepts (Moje et al. Citation2004; Moll and González Citation1994), to maintain their identities (Gee Citation1990; Wilson Citation2000), and to resist losing aspects of their individual selves (Gee Citation1990; Lefebvre Citation1991).

Indoor choosing areas

The second vignette presented in this article took place in the role play area. This was one of the ten areas available for children during ‘choosing time’. During this part of the timetable, the children could choose where they wanted to be, who they want to be with and what they wanted to do. The indoor choosing areas had some rules based on safety concerns – for example they were not allowed to wrestle or play Power Rangers. The indoor choosing areas were the spaces with the least restriction and control, and the child-initiated play that occurred in these spaces frequently yielded rich moments of third space creation.

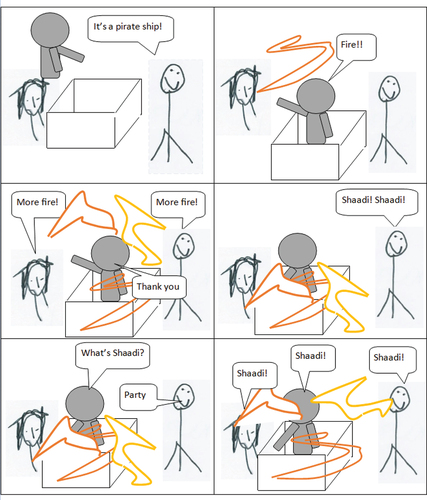

The following vignette () documents an episode of play that took place between Ali, a refugee from Iraq who had recently arrived from Poland after seeking asylum there for two years; Ebo, whose father was from Pakistan but with whom he no longer had contact so Ebo only spoke English; and Naan, a boy from Pakistan who moved to Sheffield the year before the research was undertaken.

In this vignette, the children’s play begins with turning a box into a pirate ship. As they collaborate with each other, their play progresses and they build on one another’s ideas a combining these in new and complex ways (Broadhead Citation2004). Ebo throws a piece of orange material at Ali,Footnote1 the ship’s pirate. Ali shouts ‘fire’ and tries to sail away, which triggers Naan and Ebo throw more ‘fire’ at Ali. Naan then begins to shout ‘shaadi! Shaadi!’. Ali asks what ‘shaadi’ means, to which Naan responds ‘party’, then all three children began to shout ‘shaadi’ as they continue to throw coloured material in the air. A few days later, Ebo and Ali were observed in the outside area, without Naan. They were throwing coloured material in the air and shouting ‘shaadi!’. Interestingly, the word ‘shaadi’ actually means ‘wedding’, rather than ‘party’ specifically, but here the word ‘shaadi’ had taken on a new meaning- to throw coloured material.

Indoor choosing areas: discussion

In this vignette, the children are in the role play area where they can choose which resources to engage with and what the goal of their activity is. When the children were in the indoor choosing areas, they were able to move their bodies freely and decide what they wanted to communicate about. This contrasts with both sitting on the carpet where all aspects of the interactions were controlled by the teacher, and with sitting at tables where their physical bodies remaining seated but they had freedom in their interactions. The resultant play is complex, blending fragments of different themes – pirates, fire, and weddings – into a hybrid space (Bhabha Citation1994; Soja Citation2009). Ali convincingly plays the part of a pirate, drawing on funds of knowledge acquired from popular culture (Marsh and Millard Citation2006). He reproduces actions, behaviours and values associated with a pirate, fusing his knowledge of pirates with new possibilities that might allow him to take on a different identity, and the acceptable social rules of this role (Hedges, Cullen, and Jordan Citation2011). Ebo instigates throwing the materials and shouting fire. By re-appropriating the resources, Ebo transforms the environment and develops the objectives of their play (Cole Citation1998; Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda Citation1999; Wilson Citation2000). The word ‘shaadi’ is introduced by Naan who draws on his funds of knowledge in the Pakistani community, and his multilingual repertoire, relating coloured materials to the concept of a wedding, or a ‘party’ (Moll et al. Citation1992). Once the concept of a party has been introduced, the play theme evolves yet again, culminating in a third space that is collaborative and stretches beyond the individual children: it is a cognition that exists ‘beyond the skull’ (Rogoff Citation2003, 271). The themes of children’s play are mutually understood through their collaboration and multimodal communication, evidencing intersubjectivity in the third space. In this respect, the metaphor of a ‘bridge’ has been used to describe the third space between an individual’s home and school discourses (Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda Citation1999; Moje et al. Citation2004; Yahya and Wood Citation2017). The findings in this study extend previous research that likens the third place to a bridge (singular) by clearly demonstrate that the third space is more akin to a network of multiple bridges that operate on multiple levels simultaneously, such as cultural discourses, linguistic resources and play scripts. In addition, the singular bridge metaphor does not sufficiently capture the nature of third space as a nexus between different people’s experiences. Therefore, in lieu of a ‘bridge’, a more appropriate metaphor for the third space might be an intersubjective ‘spaghetti junction’ with multiple entrances, exits, levels and connections.

In the indoor choosing areas, the children could engage in play that did not have a fixed objective, for an extended period of time. It is important to note that it is not only the spatial features of a context, but also the temporal that impacts upon the activities that occur. The extended time period during which indoor choosing took place meant that play could develop and build momentum (Broadhead Citation2004). Lengthy sessions, combined with the absence of rules permits the play to take on a life of its own during which, embodying what Rogoff (Citation2003) calls ‘guided participation’, the children rarely gave each other direct instructions. Instead, they tended to observe each other and respond to the shifting play theme by adjusting their activities organically as their play ebbs and flows.

Thus, the children create a third space that is more than just a sum of these different parts: it is transformative in nature (Cole Citation1998; Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda Citation1999; Moje et al. Citation2004; Waterhouse et al. Citation2009). The children transform the strips of material that morph from being fire to being streamers at a party. The children also name the action of throwing the material up in the air ‘shaadi’, giving this word a new meaning that differs from its standard definition. As such, the third space not only offers the opportunity for children to ascribe new purposes to the physical objects that surround them, they are also actively transforming communicative resources. This point is important, as if demonstrates how mediating tools, such as spoken language, are influenced by sociocultural contexts on the one hand (Daniels Citation2016); but on the other hand, it also shows how communicative resources are not static entities that exist objectively (Bakhtin Citation1975; Gumperz and Cook-Gumperz Citation2005). In this example of Vygotky’s notion of ‘mediation’ (Citation1978), the children use a word that was influenced by Naan’s experiences in his community, but, importantly, the children are active agents in that they repurpose the word and give it new meaning, demonstrating the dynamicity of language (Bakhtin Citation1975) and creativity in the third space (Cole Citation1998; Gutiérrez, Baquedano-Lopez, and Tejeda Citation1999).

The children’s engagement in play is significant in this vignette, as it is widely understood that role play allows children to experiment with different situations and develop a repertoire of responses that can then be employed in subsequent, similar situations (Wood Citation2013). The findings are consistent with Yahya and Wood (Citation2017) who theorised play as a third space that enabled multicultural children to bridge home and school discourses. Play affords children an abundance of modes of communication – verbal and multimodal, and the opportunity to test out different styles, registers and codes. As third space practices are interactive in nature (Wilson Citation2000), the more modes of communication that are available, the more intense and transformative the third space becomes. During play, the children’s freedom to choose enables the creation of a third space that consolidates their prior experiences that are brought into conversation with their peers and opens up possibilities for transformative practices that extend their understandings of the world beyond the ‘here and now’.

Conclusion: towards a third space pedagogy

This article has presented the case that playful communicative interactions in the third space yield complex scenarios in which children fuse knowledge from out of school contexts with new concepts, deepening their understanding and supporting their learning. Play facilitates such third space production, generating opportunities for exploration, creativity and transformation that, in turn, catalyse children’s development. It is, therefore, proposed that teachers and practitioners could, and arguably should, incorporate the third space into their pedagogical strategies to enhance children’s learning and development: A third space pedagogy.

Such a third space pedagogy would be particularly beneficial in super-diverse communities, where it would be virtually impossible to implement one uniform pedagogical approach that is consistent in equity, whilst including the funds of knowledge that each child has amassed from a myriad of backgrounds across the globe. To recall, a super-diverse community is a mosaic of people, and each individual’s lived experience is influenced by multiple, intersecting variables. In the face of such complexity, policy makers have the tendency to steer towards ‘reduction’, following the rhetoric that in order to manage such multiplicity, it must be simplified (Mayblin Citation2019). In England, the Early Years Statutory Framework (EYFS) has early learning goals that set out what is expected of a child at each age. In doing so, the EYFS creates a uniform prototype of ‘typically developing child’ (Lenz Taguchi Citation2010; MacNaughton Citation2005). This position is reinforced by OFSTED’s guidance for EYFS teachers. For example, in a critical analysis of Teaching and Play (Ofsted Citation2015) Wood (Citation2019) argues that the guidance strips play of the complexities, uncertainties and diversities present in ECE communities. While a reductive approach to play is problematic, it is a particularly inadequate model to apply in a community of children who are linguistically, ethnically and culturally diverse and who have experienced such different pathways in life (Ang Citation2010).

A third space pedagogy is the opposite of complexity reduction, and respects children’s funds of knowledge in super-diverse communities. However, developing a third space pedagogy would require the teachers to let the children initiate and drive their own activities. The rhetoric of ECE policy makers tends to favour a reductive pedagogical approach in which learning trajectories are planned. While the researcher acknowledges that teachers are active agents who bring their own experience and perspectives to the implementation of policy, it is also recognised that teachers find themselves under increasing pressure to conform to this rigid pedagogical model. However, giving children choice and control over the goals and outcomes of their play would mean shedding this narrow orientation in favour of an integrated approach that blends teacher-led activity with a an appreciation of the spontaneity and uncertainty that comes about through play.

To recall, the data presented in this article relates to the research question:

What is the relationship between the cultural-institutional contexts of communication and the resources children draw upon to communicate in a super-diverse environment?

This paper has made the case that the cultural-institutional contexts, such as sitting on the carpet or ‘choosing’ indoors, and their concomitant rules and expectations, directly impact opportunities for third space creation. The researcher fully recognises that asking children to ‘do good learning’ by sitting still on the carpet and listening to the teacher, even at the age of four, is entrenched in current ECE policy in England. However, it is argued that providing free space, free time and the freedom to choose should be purposefully integrated into pedagogy in order for deeply complex third space interactions to occur. Broadening policy discourse to incorporate the third space as a pedagogical lens would enable teachers to then play close attention to children’s play episodes, so as to recognise, appreciate and develop the transformative ideas that children create in the third space.

Teachers are instrumental in enabling third space creation and maintenance, as they control the availability of open-ended play opportunities and the amount of time children can engage in child-led activities. Thus, it would be beneficial for teachers to engage with the conceptual framework of a third space pedagogy during initial teacher training and to be given the opportunity to observe and reflect on the affordances of the third space during placements and as part of their continued professional development. That said, further research would be helpful in establishing different roles and strategies that teachers could adopt in order to facilitate third space creation and maintenance. In this study, the third space was created when teachers were absent as their presence tended to interrupt the children’s momentum and inhibit third space creation. It would be interesting for further investigation to be carried out with teachers who understood the third space to see how they could encourage and extend it.

Given that the study took place with one particular cohort in one inner-city school in England, the researcher does not claim that the findings from this study are representative of the experiences of all four- and five-year olds in similarly super-diverse communities. The project would, therefore, need to be replicated in different locations in England and internationally in order to build up large body of evidence to confirm the conclusions of this study.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Prof. Elizabeth Wood for her suggestions and comments on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Ali left the school shortly after the research began, and did not have the opportunity to draw a self-portrait.

References

- Alderson, P. 2008. “Children as Researchers: Participation Rights and Research Methods.” In Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices, edited by P. Christensen and A. James, 276–290. New York: Routledge.

- Ang, L. 2010. “Critical Perspectives on Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood: Building an Inclusive Curriculum and Provision.” Early Years: An International Research Journal 30 (1): 41–52.

- Anning, A. 2004. Making Sense of Children’s Drawings. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1975. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays Translated by M. Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bourke, R., and J. Loveridge. 2014. “Exploring Informed Consent and Dissent through Children’s Participation in Educational Research.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 37 (2): 151–165.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Broadhead, P. 2004. Early Years Play and Learning. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, E., and L. E. Lassiter. 2014. Doing Ethnography Today: Theories, Methods, Exercises. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

- Christensen, P., and A. James, Eds. 2008. Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

- Cole, M. 1998. “Can Cultural Psychology Helps Us Think About Diversity?” Mind, Culture and Activity 5 (4): 291–304.

- Corsaro, W. A. 1988. “Peer Culture in the Preschool.” Theory into Practice 27 (1): 19–24.

- Daniels, H. 2016. Vygotsky and Pedagogy. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- De Bock, J. 2015. “Not All the Same after All? Superdiversity as a Lens for the Study of past Migrations.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 583–595.

- Department for Education (DfE). 2017. “Statutory Framework for Early Years Foundation Stage.” Retrieved from: https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/files/2017/03/EYFS_STATUTORY_FRAMEWORK_2017.pdf

- Department for Education (DfE). 2020. “Early Years Foundation Stage Profile.” Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/942421/EYFSP_Handbook_2021.pdf

- Fashanu, C., E. Wood, and M. Payne. 2019. “Multilingual Communication under the Radar: How Multilingual Children Challenge the Dominant Monolingual Discourse in a Super-Diverse, Early Years Educational Setting in England.” English in Education 54 (1): 93–112.

- Gallagher, M. 2010. “Are Schools Panoptic?” Surveillance & Society 7 (3–4): 262–272.

- Garte, R. 2016. “A Sociocultural, Activity-based Account of Preschooler Intersubjectivity.” Culture and Psychology 22 (2): 254–275.

- Gee, J. P. 1990. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses, Critical Perspectives on Literacy and Education. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gonzalez, N., L. Moll, and C. Amanti. 2005. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Graham, A., M. Powell, and N. Taylor. 2015. “Ethical Research Involving Children: Encouraging Reflexive Engagement in Research with Children and Young People.” Children and Society 29: 331–343.

- Guillemin, M., and L. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity, and ‘Ethically Important Moments’ in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280.

- Gumperz, J. J., and J. Cook-Gumperz. 2005. “Language Standardization and the Complexities of Communicative Practice.” In Complexities: Beyond Nature and Nurture, edited by S. Mackinnon and S. Silverman, 268–288. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gutiérrez, K., P. Baquedano-Lopez, and C. Tejeda. 1999. “Rethinking Diversity: Hybridity and Hybrid Language Practices in the Third Space.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 6: 286–303.

- Hedges, H., J. Cullen, and B. Jordan. 2011. “Early Years Curriculum: Funds of Knowledge as a Conceptual Framework for Children’s Interests.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 43 (2): 185–205.

- Hicks, D. 1995. “Discourse, learning and teaching.” Review of Research in Education, 21(1), 49–95

- Hicks, D. 1996. “Contextual inquiries: A discourse-oriented study of classroom learning”. In Discourse, learning and schooling, edited by D. Hicks, 104–144. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Hughes, P. 2001. “Paradigms, Methods and Knowledge.” In Doing Early Childhood Research: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice, edited by G. MacNaughton, S. A. Rolfe, and I. Siraj-Blatchford, 31–55. Crow’s Nest (NSW): Allen & Unwin.

- Jones, S., J. J. Thiel, D. Dávila, E. Pittard, J. F. Woglom, X. Zhou, T. Brown, and M. Snow. 2016. “Childhood Geographies and Spatial Justice: Making Sense of Place and Space-Making as Political Acts in Education.” American Educational Research Journal 53 (4): 1126–1158.

- Kay, L. 2018. “‘Bold Beginnings and the Rhetoric of School Readiness’.” Forum 60 (3): 327–336.

- Kernan, N., and D. Devine. 2010. “Being Confined Within? Constructions of the Good Childhood and Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings in Ireland.” Children and Society 24: 371–385.

- Kraftl, P., J. Horton, and F. Tucker. 2012. “Editors’ Introduction: Critical Geographies of Childhood and Youth.” In Critical Geographies of Childhood and Youth: Contemporary Policy and Practice, edited by P. Kraftl, J. Horton, and F. Tucker, 1–26. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. 2010. “Rethinking Pedagogical Practices in Early Childhood Education: A Multidimensional Approach to Learning and Inclusion.” In Contemporary Perspectives on Early Childhood Education, edited by N. Yelland, 14–32. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Levy, R. 2008. “‘Third Spaces’ are Interesting Places: Applying ‘Third Space Theory’ to Nursery-aged Children’s Constructions of Themselves as Readers.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 8 (1): 43–66.

- Lundy, L., L. McEvoy, and B. Byrne. 2011. “Working with Young Children as Co-Researchers: An Approach Informed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Early Education and Development 22 (5): 714–736.

- MacNaughton, G. 2005. Doing Foucault in Early Childhood Studies: Applying Poststructural Ideas. London: Routledge.

- Marsh, J., and E. Millard. 2006. Popular Literacies, Childhood and Schooling. London: Routledge.

- Matusov, E. 1996. “Intersubjectivity without Agreement.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 3: 25–45.

- Mayblin, L. 2019. “Imagining Asylum, Governing Asylum Seekers: Complexity Reduction and Policy Making in the UK Home Office.” Migration Studies 7 (1): 1–20.

- Meer, F., and S. Vertovec. 2015. “Comparing Super-Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 541–555.

- Moje, E. B., K. M. Ciechanowski, K. Kramer, L. Ellis, R. Carrillo, and T. Collazo. 2004. “Working toward Third Space in Content are a Literacy: An Examination of Every Day Funds of Knowledge and Discouse.” Reading Research Quarterly 39 (1): 38–70.

- Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 31 (2): 132–141.

- Moll, L. C., and N. González. 1994. “Lessons from the Research with Language Minority Children.” Journal of Reading Behavior 26 (4): 439–455.

- Moss, P. 2012. Early Childhood and Compulsory Education: Reconceptualising the Relationship. London: Routledge.

- Ofsted. 2015. “Teaching and Play in the Early Years – A Balancing Act?.” July, No. 150085. www.Ofsted.gov.uk

- Ofsted. 2017. “Bold Beginnings – The Reception Curriculum in a Sample of Good and Outstanding Primary Schools.” November, No 170045. www.Ofsted.gov.uk

- Pike, J. 2008. “Foucault, Space and Primary School Dining Rooms.” Children’s Geographies 6 (4): 413–422.

- Prout, A. 2005. The Future of Childhood. Oxon: Routledge Falmer.

- Roberts-Holmes, G. 2019. “School Readiness, Governance and Early Years Ability Grouping.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 00 (0): 1–10.

- Rogoff, B. 1990. Apprenticeship in Thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 1995. “Observing Sociocultural Activity on Three Planes: Participatory Appropriate, Guided Participation, and Apprenticeship.” In Sociocultural Studies of Mind, edited by J. Wertsh, P. Rio, and A. Alvarez, 139–164. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 2014. “Learning by Observing and Pitching into Family and Community Endeavors: An Orientation.” Human Development 57 (2–3): 69–81.

- Rogoff, B., R. Mejia-Arauz, and M. Correa-Chavez. 2015. “Chapter One - A Cultural Paradigm - Learning by Observing and Pitching.” Advances in Child Development and Behaviour 49: 1–22.

- Sepulveda, L., S. Syrett, and F. Lyon. 2011. “Population Superdiversity and New Migrant Enterprise: The Case of London.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 23 (7–8): 469–497.

- Soja, E. W. 1989. Post-Modern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. London: Verso.

- Soja, E. W. 2009. “Thirdspace: Towards a New Consciousness of Space and Spatiality.” In Communicating in the Third Space, edited by K. Ikas and G. Wagner, 49–61. London: Routledge.

- Vertovec, S. 2006. “The Emergence of Super-Diversity in Britain.” Centre on Migration, Policy and Society Working paper 25. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-2006-025-Vertovec_Super-Diversity_Britain.pdf

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Vertovec, S. 2013. Reading ‘Super-diversity’. Max Planck Institute for Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity. https://www.mmg.mpg.de/38383/blog-vertovec-super-diversity.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Waterhouse, J., C. McLaughlin, R. McLellan, and B. Morgan. 2009. Communities of Enquiry as a Third Space: Exploring Theory and Practice, presented at British Education Research Association 2009 Annual Conference, University of Manchester. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/974e/8e14632f6ccfdda97ce002883cd9300c277b.pdf?_ga=2.125922504.452381175.1585684695–1250428687.1585684695

- Wilson, A. 2000. “There Is No Escape from Third-Space Theory: Borderland Discourse and the In-Between Literacies of Prison.” In Situated Literacies: Reading and Writing in Context, edited by D. Barton, M. Hamilton, and R. Ivanovic, 51–66. London: Routledge.

- Wood, E. 2010. “Developing Integrated Pedagogical Approaches to Play and Learning.” In Play and Learning in the Early Years, edited by P. Broadhead, J. Howard, and E. Wood, 9–26. London: Sage.

- Wood, E. 2013. Play, Learning and the Childhood Curriculum. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Wood, E. 2015. “The Capture of Play within Policy Discourses: A Critical Analysis of the UK Frameworks for Early Childhood Education.” In International Perspectives on Children’s Play, edited by J. L. Roopnarine, M. Patte, J. E. Johnson, and D. Kuschner, 187–198. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Wood, E. 2019. “Unbalanced and Unbalancing Acts in the Early Years Foundation Stage: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Policy-led Evidence on Teaching and Play from the Office for Standards in Education in England (Ofsted).” Education 47 (7): 784–795.

- Yahya, R., and E. Wood. 2017. “Play as Third Space between Home and School: Bridging Cultural Discourses.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 15 (3): 305–322.