ABSTRACT

In Myanmar, large diverse indigenous ethnicities exist, and, as a result, public schools consist of a multicultural and multilingual student population. Despite this, the education system proffers and embeds Myanmar’s dominant ideologies relating to culture, language and religion within all aspects of schooling. Students from minority backgrounds often struggle to gain legitimacy and build capital in a system that does not acknowledge diversity. Drawing upon Bourdieu’s concepts of social reproduction, field and capital, this study examines how multiculturalism and multilingualism are positioned within Myanmar’s education policies and how Myanmar’s school leaders and teachers reflect and respond to the needs of students from minority backgrounds within the complex political and educational setting. This qualitative case study captured the perspectives of five participants: two school leaders and three teachers. The findings reveal that students from minority backgrounds experience religious-based inequalities, cultural exclusion, and indifference towards their language backgrounds in public school settings.

Introduction

Due to increased migration caused by political, economic, and social issues, societies have become more culturally, linguistically, religiously, and ethnically diverse worldwide (Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Buckingham Citation2019; Gao, Lai, and Halse Citation2019). For instance, societies in the United States, Australia, and Europe are increasingly multicultural (Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Dubbeld et al. Citation2019; Torres and Tarozzi Citation2020). While the Western world has experienced increased cultural and linguistic diversity due to globalisation and increasing migration (Dubbeld et al. Citation2019), cultural diversity looks different in other countries (Anui and Arphattananon Citation2021). For example, Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand and Myanmar, are culturally and ethnically diverse because they are ‘home’ to numerous indigenous ethnic minorities (158). In Myanmar, there are eight major ethnic nationalities and more than 100 ethnolinguistic groups. The Myanmar regime identified 135 groups as national races despite disagreement with this controversial number among many ethnic communities (Clarke, Myint, and Siwa Citation2019).

Previous research has indicated that students from minority backgrounds are more likely to experience academic difficulties and develop social, emotional, and behavioural problems at school (Gubi and Joel Citation2015). Students from ethnocultural and linguistic minority groups, in particular, often encounter more educational challenges and behaviour problems than their peers (Gubi and Joel Citation2015; Skiba et al. Citation2011). Many scholars argue that there is a need to create caring and supportive classroom climates for ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse students because these students often encounter challenges on a daily basis in schools (Albeg and Castro-Olivo Citation2014; Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Due and Riggs Citation2016). Therefore, it becomes critical for schools to build more inclusive environments for every student, regardless of their background, to learn and feel safe within the classroom. As a result, teachers and school leaders play a crucial role in ensuring that students from diverse backgrounds receive quality learning experiences in schools.

Objectives of the study

This study investigated how school leaders and teachers create equal educational opportunities for ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse students in Myanmar public schools within their complex political and educational setting. It also interrogates how students from diverse backgrounds are positioned within the Myanmar education system and sought to answer the following research question: How do school leaders and teachers in Myanmar public schools understand and respond to the needs of students from diverse backgrounds?

To answer this question, Bourdieu’s concepts of social reproduction, field and capital were used to theorise the system of Myanmar’s colonial society and how its structures influence the educational opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds. The structure of this paper is as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework of the study, followed by the national context of Myanmar and the research design. Then the findings are then reported under three sub-headings: religious diversity, cultural diversity and linguistic diversity. This section is followed by the discussion and conclusion, including implications and directions for future research.

Theoretical framework

This study drew on Bourdieu’s concepts of social reproduction, field and capital to explore how students from minority backgrounds are positioned within the Myanmar education system. Over 45 years ago, Bourdieu, Pierre, and Passeron (Citation1977) found that education systems inculcated and reproduced dominant social norms through a process of social reproduction. Despite Bourdieu being known for his analysis of social and economic inequalities in a European context and without any specific interrogation of how race and/or ethnicity were used as mechanisms of exclusion (Rodríguez, Boatcă, and Costa Citation2016), his earlier work attempted to critique colonialisation, viewing it as a racialised form of domination (Go Citation2013). While Bourdieu’s concepts of social reproduction, field and capital were initially developed and applied in a European context, we argue that his early research work in Algeria laid the foundation for his ideas relating to social and economic inequalities (Bourdieu Citation1961; Go Citation2013) and contribute to understanding the structures and logics of colonialisation. Bourdieu (Citation1961) viewed colonialism as a system or structure of racial domination which was legitimised by dominant actors (e.g., colonisers) and reproduced in social practices within the field. He wrote that there was ‘a rationalisation of the existing state of affairs so as to make it appear to be a lawfully instituted power’ (133). In the case of French Algeria, there was systematic suppression of Algerians (e.g., the colonised), enacted by French policies yet legitimised by ‘the logical coherence of the [colonial] system’ (Bourdieu Citation1961, 146, quoted in; Go Citation2013).

Furthering this notion that the logical coherence of a social structure – such as a colonial system – legitimises certain social norms and/or practices. Apple (Citation1992) contends that certain knowledges are socially legitimised in schools, with no curriculum being neutral. Like Apple (Citation1992), many scholars have raised concerns that dominant ideologies (e.g., relating to ethnicity, social class, religion and monolingualism) can be socially reproduced within and through school curriculum and school and teacher practices, resulting in inequalities (Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Barnes, Amina, and Cardona-Escobar Citation2021; Bishop Citation2014; Knoblauch and Brannon Citation1993). Many have argued that colonialisation has led to the privileging of Western modes of knowledge over non-Western modes, acting as a form of racialised domination (e.g., see Said Citation1978; Spivak Citation1988; Stein and Andreotti Citation2016). The privileging of particular knowledges reveals how dominant ideologies and knowledges come to be offered within the education system. Thus, we explored how dominant knowledges and practices are privileged and socially reproduced in the context of Myanmar public schools and argue that, in order to decolonise particular knowledges and practices, we need to provide opportunities to not only identify but capitalise on differences (Hassan Citation2022). By encouraging a process of reflexivity among school leaders and teachers, we examined how students from minority backgrounds were positioned within the Myanmar education system and how school leaders and teachers responded to their needs.

In addition to employing the concept of social reproduction to interrogate which key ideologies were dominant within education, Bourdieu’s concepts of field and capital were useful for interrogating how students from minority backgrounds were positioned within the education system. Bourdieu (Citation1990) argued that social contexts, or fields, such as schools, educational institutions, and workplaces, consist of a system of structured power relationships where social actors must possess capital, viewed as a source of advantage, to be legitimised within a particular social context (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of capital is based on three components of capital: economic, cultural, and social. However, for this paper, we focus primarily on cultural capital. Cultural capital refers to objectified, embodied and institutionalised wealth in the form of cultural goods (e.g., values, skills and knowledge). The education system, in many ways, is viewed as a conduit for intellectual and educational ‘wealth’ (Barnes Citation2021).

Bourdieu (Citation1991) acknowledges that language is one such form of capital as it provides individuals with access to materials and educational opportunities; a form of cultural capital realised in the light of an individual’s ability to gain the knowledge and skills legitimised by dominant social actors. An individual able to access resources, education, and employment opportunities through their linguistic resources in turn enhance other forms of capital (Barnes, Amina, and Cardona-Escobar Citation2021). Thus, in order to decolonise knowledge in education systems, knowledge needs to be structured in a way that acknowledges and values cultural and linguistic differences (Prah Citation2017). This study, therefore, examined how dominant ideologies are promoted in schools in Myanmar and how school leaders and teachers understood and responded to students’ cultural and linguistic differences.

National contexts: Myanmar

Myanmar, also known as Burma, is a country in Southeast Asia. It is one of the least developed countries on the list of United Nations, has a population of about 54 million and is a heterogeneous linguistic country with multi-ethnic nationalities. Myanmar consists of more than a hundred ethnolinguistic groups with their distinctive languages, cultures, and historical backgrounds (United Nations Citation2022; World Population Review Citation2022). According to the 2008 Myanmar constitution (Myanmar Constitution, 2008, article 450), the official or national language is Burmese, mentioned as the Myanmar language, which is the language of the majority ethnic group, ‘Bamar’. In other words, ‘Myanmar’ refers to the country’s name and the language of the majority ethnic group.

Myanmar has been under military rule for about six decades since gaining independence from the UK in 1948. Since Burma achieved independence from British rule, the campaign of ‘Burmanisation’, or colonising indigenous minorities’ cultures and languages with the domination of the majority’s (Bamar/Burmese) culture, language and religion, has been implemented, neglecting the richness of cultural and ethnic diversity within the country (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021). Therefore, for decolonising Bumanisation, since the 1960s, ethnic minorities have been fighting against the militarised government to preserve their autonomy, identity, cultures, and languages (Lall and South Citation2014; South and Lall Citation2016; Walton Citation2013). The military regime held a so-called ‘general election’ in 2010, and a military-backed semi-democratic government was elected and came into power. Since then, Myanmar was considered to be in the process of reform following a decades-long military regime to a democratic nation until there was another military coup on the first of February in 2021.

Myanmar’s education system

After the first military coup in 1962, the Myanmar education system was characterised by the so-called ‘Burmese Way to Socialism’ education (Lwin Citation2019, 275). Before 1962, Myanmar’s education was recognised as one of the best in Southeast Asia (Hayden and Martin Citation2013). However, mismanagement and low budget allocations for education, few opportunities for professional development, using education as a political proxy, and more than 50 years of civil war and armed conflicts between majority and minority indigenous ethnic groups resulted in Myanmar’s education system becoming poor quality (Hayden and Martin Citation2013; Lall and South Citation2014; South and Lall Citation2016).

The ‘Burmanisation’ and ‘Bamarcentric’ approach has been employed in all aspects of society, including education (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021, 159), despite the population’s ethnic and linguistic diversity. Burmese is the only medium of instruction in education, although ethnic and linguistic diversity is one of Myanmar’s ‘distinctive features’ (Lall and South Citation2014, 485). Burmese is also taught as a compulsory subject like English and Mathematics at all levels of Education, from primary to higher education and across most courses. Education has been used as the political tool for ‘Burmanisation’, promoting the use of monolingualism and monoculturalism at every level of education (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021). In addition, the education system has been highly centralised, and the majority’s political and social dominance is one of the critical factors in the conflict and tension among different ethnicities (Hayden and Martin Citation2013). To cope with the regime’s ‘Burmanisation’ agenda, ethnic minority groups have sought to preserve their language and culture by demanding the incorporation of their language, cultures, and histories in education (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021; Walton Citation2013).

Myanmar’s education system is a Kindergarten (KG) +12 structure: primary education starts from kindergarten through year 6 (Grades 1 to 6), lower secondary for four years (Grades 7 to Grade 10), and two years of upper secondary (Grade 11 and 12). While government public schools are the leading education providers across Myanmar, there are other schools that operate outside the government public school systems, such as schools managed by the education department of the ethnic armed organisations (EAOs)Footnote1 in their controlled areas, schools operated by religious institutions (e.g., monastery-based schools and church-based schools) and schools run by civil societies. These non-government schools, including monastery-based schools run by ethnic minority communities, mostly use students’ mother tongue as the language of instruction in the classroom (Lwin Citation2019).

Significantly, the political context is the key contributing factor in the Myanmar education sector because education reform in Myanmar began when the semi-democracy government came into power in 2011. For instance, according to Article 44 of the National Education Law (2014), implementing the local curriculum is one result of education reform. Although it is stated that implementing the local curriculum promotes multiculturalism and social cohesion (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021), Lwin (Citation2019) reported that the curriculum produced by the central government alone has failed to meet the local needs of the students from ethnic minority regions, and due to the system in which teachers’ appointment, promotion and transfer are decided by the central government, teachers working in ethnic minority areas often fail to understand the language and culture of the local students.

Research design

Participants

The participants in this study were two principals and three teachers with between 5 and 12 years of teaching and leadership experience in government public schools in Myanmar. All five participants reported having experience teaching students from minority backgrounds in both primary and secondary classrooms. Four participants were Buddhists, and one participant was Christian. According to the 2014 Myanmar census, Buddhism is the dominant religion, with 87.9% of the total population identifying as Buddhist and the remaining 12.1% identifying as Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Animist, or ‘other’. All the participants had joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) since the coup of February 2021. The CDM was joined by public servants from different government ministries who refused to return to work as long as the military remained in power. CDM also referred to citizens’ acts of boycotting military-related businesses. All members of the CDM were expelled by the coup government due to their participation in the CDM. Following the approval of the institution’s ethics committee, participants were recruited through the professional network of Author 1 in Myanmar. provides the demographic profile of the participants in the study. Participants’ self-identified demographics, such as name, gender, ethnicity, and religion, were collected at the beginning of each interview. The authors offered participants the opportunity to self-identify rather than limiting the options and providing available choices. Additionally, before conducting the interview, Author 1 informed them that they have the right to refuse to answer any questions they felt invaded their privacy since, as Clark et al. (Citation2021) state, providing informed consent does not mean participants entirely abolish their right to privacy. For ethical reasons, pseudonyms were used throughout.

Table 1. Participants demographic profiles.

Data collection

Author 1 conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with the participants via Zoom. Each interview lasted between 30 and 40 minutes. As the participants experienced interrupted power supply and limited internet connection due to restrictions made by the military regime, utmost care was taken to ensure that the interview was conducted at a time that was convenient for the participants. In the first part of the interview, the participants’ demographic profiles, including their educational and professional background, such as education, experience, and position, were asked for. Then, the participants were asked about their multicultural perspectives of the diversity of students in their schools and their career experiences of how they respond to the needs of students from diverse backgrounds. For example, as a teacher/principal/vice-principal, how do you view the diversity of students in your school? What do you do as a teacher/principal/vice-principal to teach/support students from diverse backgrounds in the school setting? The interviews were audio-recorded, and the files were encrypted and stored in a password-protected device. Before the interviews, research ethics were approved by the research ethics committee in the university where Author 1 studied.

Data analysis: thematic analysis

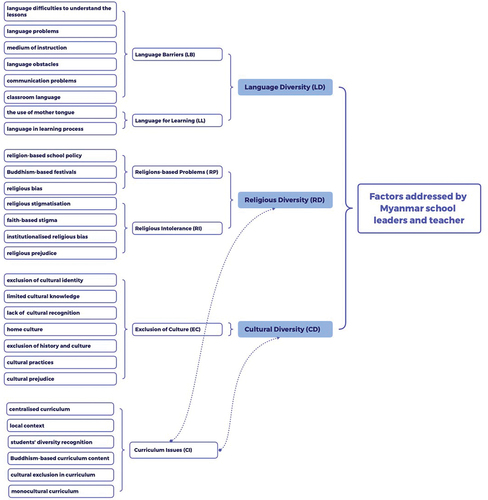

After transcribing the interview data, these were analysed by Author 1 using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This involved applying the six stages of the process: familiarisation with the data, generating initial coding, identifying themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, and evidencing themes. First, Author 1 read the transcript several times to familiarise herself with the data. Notes were taken before beginning the more formal coding process. Next, initial codes (n = 28) (see ) were manually generated across the entire data set by identifying potential repeated patterns (themes) with full and equal attention given to each data segment. The initial codes were then combined and clustered into six themes. These six themes were further grouped to form three overarching themes: (1) language diversity, (2) religious diversity, and (3) cultural diversity. Finally, the authors related the analysis to the research question and identified the three factors that were addressed by the Myanmar school leaders and teachers. This process is illustrated in .

This research was guided by the four criteria for trustworthiness proposed by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985): credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. This was done by choosing informants from different regions and states across Myanmar for credibility; providing sufficient information about the context and data collection for transferability; depicting the detailed processes within the study for dependability and including in-depth methodological descriptions to ensure that the findings are the results of the experiences and perspectives of the informants and the triangulation of data sources for confirmability.

Limitations

In this study, there are some limitations. The first relates to the small sample size. As the findings are based on the participants’ perspectives and experiences, the finding may not be generalised to represent a wider group and context. Second, due to the limited time and the political crisis in Myanmar, the diversity of the participants, such as the age group, gender, educational background, positions, and school location, were not underscored during the recruitment. Third, the position of Author 1 from her minority background may influence the data interpretations. Finally, this study does not reflect the correlation between joining CDM and their multicultural perspectives. Future research is encouraged to discuss these issues more comprehensively.

Findings

The findings revealed how school leaders and teachers in Myanmar public schools understood and respond to the needs of students from diverse backgrounds. This study reports three factors underlining (1) religious diversity (2) cultural diversity (3) linguistic diversity.

Religious diversity: an opportunity or a symbol of inequality?

The findings revealed that the participating teachers acknowledged the dominance and positionality of Buddhist religious ideals and practices embedded within the curriculum and everyday school practices. While Buddhism is a historically dominant religion in Myanmar, it was the omission and silencing of any other religions, particularly those reflecting the minority groups in Myanmar, that was noted.

Only Buddhism-related content is seen in textbooks. (Win, school leader)

There is no content about minority [religions] but only Buddhism in the curriculum. Students have to learn solely about Buddhism and thus have little knowledge about other religions. (Phyu, teacher)

These two responders similarly reported the dominance of a single, dominant religion and a lack of acknowledgement of Myanmar’s existing religious diversity. This lack of acknowledgement led Phyu to argue that it could lead to inequalities in the classroom as students with knowledge of the dominant religion would be advantaged. Phyu, for example, explained that ‘this kind of partiality benefited the students from that religious background [those who identified as being Buddhist]’. Despite having a prescribed curriculum and textbooks, Phyu also stated that to address the embedded partiality towards Buddhist students, teachers needed to ‘learn about students’ religions and cultures’ because they had little understanding of other faiths. Teachers, themselves, were products of social reproduction, having little understanding ‘about other religions [that] are not included in the curriculum’.

In addition to Buddhism’s dominant position within the curriculum and textbooks, the participants also revealed that Buddhist religious practices were part of everyday classroom practices in Myanmar, despite the existence of minority students.

The policymakers instruct students to recite the Buddhist prayer when the school starts the day at 9:00 am every morning […] according to the policies and guidelines developed by the Ministry … So, these policies have a negative impact on students from other religions because they are forced to do so [to participate in these religious practices] (Saw, teacher)

When students arrive at school, they must first salute the national flag. Then, students have to recite Buddhist prayers to start the school day (Win, school leader)

Due to the national education policy, students must recite the prayer at school regardless of their religious beliefs. The everyday practices in schools force students from minority groups to conform to practices that do not reflect their beliefs or values.

In response, many of the participating teachers felt it was unjust not to acknowledge that students may follow other religions. Some of the teachers encouraged students from minority backgrounds to pray in their religions and told them that participation in religious ceremonies was optional:

During that time [when students recite Buddhist prayers], what I do for students from other religions is encourage them to pray in the religion they believe in. (Win, school leader)

Before, for instance, a fixed amount of money was collected from every student as an individual contribution to the ‘Ka Htein’ robe offering festival at the monastery. […] Later, I let students participate in this kind of religious festival as an optional. (Zau, teacher)

While national policies have attempted to socially reproduce the religious practices of the majority within the everyday classroom, some participants attempted to utilise this as an opportunity to teach religious diversity to their students. Such an example was Zau, a secondary school teacher in an ethnic minority region where 85% of his students and himself are Christian. Zau still found value in understanding and celebrating Buddhist festivals as part of the school culture:

Most of them [students] are KachinFootnote2 and Christian. In the school culture, we celebrate the ‘Ka Htein’ Festival, a culture of the Buddhism and Bamar ethnic people. (Zau, teacher)

While Zau is a Christian, teaching in a school representing one of Myanmar’s minority groups, he still encouraged the celebration of non-Christian religious festivals as a school cultural event. While celebrating and acknowledging that a range of religions was allowed in his school, he recognised that this was not reflected in other schools in Myanmar. Like Phyu and Win, Zau believed that teachers should learn about different religions’ practices so they can explain different practices to the students in fair and meaningful ways.

As a result of the marginalisation of other religions in the curriculum, textbook and everyday classroom practices, this study found that students from minority groups were discriminated against.

While doing the school activities, some students from the main religion [Buddhism] probably have less respect for students from minority groups. […] For instance, some students discriminate against Muslim students because of their faith at school. […] Some students do not have respect for diversity and differences. (Phyu, teacher)

Similarly, Win reflected on his own student experiences, remembering how some parents segregated their children from classmates from different religious backgrounds. Win mentioned that some parents used racial slurs, such as ‘Kalar’, to mock or insult people of Indian origin or Muslim background. He explained how parents taught their children not to connect closely with students from other minority religions:

[…] When they sent their children to school, they wanted them to sit in the first rows. Then, they told them to stay away from ‘Kalar’. (Win, school leader)

Phyu and Saw also recognised that students in their classrooms held negative attitudes towards other religions. Saw perceived that students’ negative perspectives towards religious diversity would have been ‘trained and taught by parents’ at home. Phyu further stated that some Buddhist students did not consider other religions as the religions of Myanmar since there were more pagodas and monasteries in their surroundings. Although four out of the five participants were Buddhists, all participants recognised the prejudice and unequal treatment in their school community towards minority students from different religious backgrounds.

The participants attempted to tackle these stigmas and the evident discrimination among students by building social cohesion among their students. The participants tried a range of strategies including one-on-one conversations with students and encouraging students to work together. For example, Phyu said that the teacher or principal had to provide one-on-one consultation privately and discipline them not to mock or insult and discriminate against students from other faiths.

Since they have to work in a group of 4 or 5, they have to discuss in a group to get the answer. They cannot ignore their peers from other backgrounds. (Win, school leader)

This study found that while Buddhist values, knowledge and practices were embedded in the Myanmar curriculum, textbooks and everyday school practices, teachers were actively responding to the marginalisation of other religions and addressing discrimination in their classrooms.

Cultural diversity

All five participants reported the exclusion of cultural diversity in all aspects of education. These included the centralised curriculum, textbooks, school policies and national education policies. Indigenous ethnic minority students do not have opportunities to learn their culture and identity at school since the curriculum does not incorporate knowledge about minority groups, such as their history and cultural heritage, nor does it include their perspectives. This is illustrated in Saw’s remarks:

We can clearly see the domination of Bamar ethnic in the curriculum. For example, in the History subject, they include only about the Myanmar [Bamar] Kings such as Bayint Naung, Kyan Sit Tar, A Laung Min TaYar [Names of the Bamar Kings] but no representation of other ethnicities’ historical information. Actually, it must be included. (Saw, teacher)

Saw continued to highlight that the curriculum did not include historically significant rulers of other ethnic groups, such as Saw Bwar, a ruler from the ‘Shan’ ethnic group, or kings and queens from the ‘Mon’ and ‘Rakhine’ ethnic groups. The finding shows that the Myanmar curriculum excludes the cultural and local contents of non-dominant ethnicities and is regarded as an indoctrination tool.

Another participant, Zau also explained how the subject of history was politicised by changing the number of national ethnic groups or ‘taingyintha’ (the concept of national races of Myanmar) identified by the government in the History curriculum:

I can see the differences in history before and now. As a student, we learned that there were eight main ethnic groups in Myanmar. But now, we must teach the students that there are 135 ethnic groups or taingyintha in Myanmar. This is quite difficult for us [teachers]. (Zau, teacher)

Despite the disagreement with this controversial classification of ethnicities, this politicising concept is embedded in the textbooks and curriculum. Classifying ethnic categories into the list of 135 national races or taingyintha was profoundly opposed by many non-Bamar communities because the ethnic groups are incorrectly identified and subdivided, and the definition of ‘taingyintha’ or national races is inconsistent and complex (Cheesman Citation2017; Clarke, Myint, and Siwa Citation2019). Furthermore, increasing number of categories and fragmenting ethnic minority groups results in each of the minority groups having less representation in terms of politics, culture and population at both state and national levels. This also allows the majority group to maintain and advance its dominance over the minorities (Clarke, Myint, and Siwa Citation2019; Ferguson Citation2015). While the dominant ideologies are socially reproduced within the curriculum and textbooks, students from minority backgrounds do not have the opportunity to learn and maintain accurate understandings of their cultural and racial identities through day-to-day learning in classrooms.

Similarly, Tin revealed the challenges facing teachers while teaching students from different ethnic and religious backgrounds with the same centralised curriculum.

Since the curriculum is written by the central government, the contents do not reflect the local context of students’ regions and cultures. Sometimes, it is difficult for students to understand. Therefore, teachers need to compare the content of the national curriculum to what they can relate to in their cultural and regional context. (Tin)

Moreover, Saw argued that some schools and teachers do not allow students to practise their cultural habits at school. Saw reported that Gurkha (an ethnic group with Nepali ancestry) students were not allowed to display their culture of colouring hands and nails or putting a red paste made of rice (called tika) on their forehead in his school. In fact, Gurkha girls have a cultural practice of colouring their hands with ‘Dan’, known as Mehendi, a temporary tattoo during Hindu festivals and celebrations.

The Gurkha girls are prohibited from using ‘Dan’ at school. […] Gurkha girls are not allowed to come to school with ‘San’ rice on their foreheads. Teachers gave holidays officially and told them not to go to school when they were with ‘Dan’ or ‘San’. (Saw)

Saw argued that teachers did not respect students’ home cultures. When asked why these students were prohibited from following their home cultures, Saw replied that the ban sometimes comes ‘from the school’ and sometimes ‘from the teachers’:

I don’t know the reason. Maybe, teachers do not want other students to imitate or follow other students’ cultures. Or they just don’t want those students to be mocked or insulted by other students. (Saw, teacher)

Saw’s observations reveal that teachers’ actions in the classroom have direct impacts on how the classroom is perceived to be culturally inclusive. Like Saw, Zau also observed cultural exclusion, but he noticed such exclusions within national education policies. He felt that, although teachers wanted to be culturally responsive, particularly in his school where indigenous Kachin ethnicities mostly resided, they were often forced to adopt the majority’s culture solely due to the national policies of the Ministry or the Government. As an example, students in his school were forced to participate in a competition which reflected the dominant culture. This event is known as ‘So-Ka-Yay-Thi’ (in English: Sing-Dance-Compose-Play), in which students from public schools country-wide must compete in singing Burmese songs, composing Burmese songs, playing traditional Burmese instruments and performing Burmese traditional dances. This competition promotes the cultures of the majority Bamar ethnic group and is embedded within the national education policy. Notably, this event does not represent other cultures or ethnic minorities and requires students from diverse backgrounds to adapt and conform.

As a teacher from Kachin state, I think this cultural competition, ‘So-Ka-Yay-Thi’, is a hindrance for us. Since the higher-ups instruct it, we need to do this in our school. Even if we are to organise the cultural competition in Kachin state, the cultural event should be replaced with the cultural dance and traditional songs that indigenous ethnic students are familiar with. (Zau, teacher)

Zau’s comments highlight the disregard for cultural diversity at the school level as well as at the national level. This study revealed that students from cultural minority groups are more likely to experience educational and social difficulties when their cultures are unheeded in national curriculum and policies, school practices and textbook content.

Linguistic diversity

The participants stated how they perceived and addressed linguistic diversity in the monolingual classroom. The findings revealed that ethnic minority students must navigate their learning in a mono-lingual, Burmese-only classroom. The participants viewed language as a barrier for linguistic minority students. Despite language diversity existing within schools, Myanmar’s education policy grouped students into two broad categories: Students with Burmese as their first language or those with non-Burmese languages. All five participants highlighted the linguistic challenges facing non-Burmese students, given that Burmese was the medium of instruction within the classroom.Tin, a school leader, reflected on his experience of teaching non-Burmese-speaking students at school. As both a teacher and school leader, who speaks Burmese as a mother tongue, he struggled with communicating with non-Burmese-speaking students. He attempted to address this problem by teaching them the Burmese language and learning their language. Phyu also argued that when non-Burmese students learnt the Burmese language, they had better academic achievement in school. In contrast to Tin and Phyu, Saw addressed language problems by using students’ mother tongues. He explained how he encountered the language problems facing students from non-Burmese-speaking backgrounds.

[…] When students did not understand and could not write in Burmese, I told them to answer the questions in their mother tongues, such as ‘Shan’ or ‘Pa-Oh’. (Saw, teacher)

He requested other local teachers to translate the answers. He tried to understand what they had written and ensured their responses were relevant to the question.

They answered well in their mother tongues. Yes, that matters. Although I didn’t understand their language, the local teachers helped us. (Saw, teacher)

Saw accepted the use of mother tongue in his classroom and believed that classroom language should not limit students’ learning capability. In the case of Zau, he and 90% of the students speak the same language, the Kachin language. However, he revealed that they used Burmese for teaching, but they talked in Kachin during the breaks since students do not understand and speak well in Burmese. Zau perceived that teaching solely in the Burmese language was acceptable only because Burmese is the official language of Myanmar. Despite using Burmese for teaching, he still recognised that language was a barrier to their learning.

In my opinion, 10% of students [Burmese speaking students] do not have language difficulties, but the rest, more than 80% or 90% of the students, have or may have difficulties in class because they do not and cannot speak Burmese. (Zau, teacher)

Zau’s case illustrated that students’ learning is influenced by language ability. Despite the push to teach students the Burmese language, the participants still recognised the value of students’ mother tongues and felt that it could be better used to promote students’ educational achievements. The findings revealed that mono-lingual education policies and practices create barriers to learning among students from linguistic minority backgrounds.

Discussion

The findings of this paper reflect a process of social reproduction in which education systems inculcate and reproduce dominant social norms through a process of social reproduction (Bourdieu, Pierre, and Passeron Citation1977). The knowledges and practices of the Burmese are recognised and prioritised over those of ethnic minorities, revealing a form of racialised domination (Go Citation2013). According to the findings, the domination of a single religion, culture and language is inculcated in the Myanmar education systems and socially reproduced in curriculum, school practices, and policies. The participating teachers recognised the social reproduction of dominant ideologies relating to religion and cultures through both curriculum and school practices. For example, in textbooks and curricula, only the ethnic majority’s religion-related content and cultural and historical knowledge are embedded. There is little or no information about other religions and cultural ethnicities in the school curriculum, resulting in students from minority backgrounds having no or little opportunity to learn and maintain their cultural and racial identity at school. In addition, it is evident from the findings here and previous research (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021; Lwin Citation2019) that national policies and school policies have socially reproduced dominant religious and cultural practices through day-to-day classroom practices and classrooms. Such findings also resonate with colonial approaches which rationalise the social reproduction of dominant ideologies as ‘lawfully instituted power’ (Bourdieu Citation1961, 133). While the privileging of Western knowledges over non-Western knowledges was part of the logic and effect of colonialisation (e.g., see Said Citation1978; Spivak Citation1988; Stein and Andreotti Citation2016), Myanmar now reproduces its own form of racial domination. Seemingly a response to colonialism, Myanmar imposes its own nationalist dominance, with the privileging of a dominant religion, culture and language (e.g., the colonisers) over those representing other religions, cultures and languages (the colonised).

By privileging one religion, culture and language, the findings also indicate that, in public schools, Myanmar’s education system does not grant all social actors the opportunity to gain legitimacy through equal opportunities for cultural capital building. Given that social contexts consist of a structured power relationship where social actors must possess capital (Bourdieu, Pierre, and Passeron Citation1977), it is significantly more challenging for students from ethnic minority groups to build their cultural capital and identity than those from majority backgrounds when their religions, cultures and languages are disregarded and ignored in the education system and policies (Anui and Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021; Lwin Citation2019). For instance, an indifference to the language diversity within Myanmar schools has resulted in the recognition of only two linguistic groups: dominant Burmese language-speaking students and non-Burmese-speaking students. Not only does this reflect the lack of recognition of the different language backgrounds among ‘non-Burmese-speaking students’, but it also highlights how their language ability is positioned at a deficit. Rather than celebrating students’ multilingualism, it highlights their lack of Burmese speaking skills. The role of students’ mother tongue in learning is not understood in schools and the inequalities between Burmese and non-Burmese speakers are not realised in their academic achievement. As a result, while education systems should be conduits for intellectual and educational wealth (Barnes, Amina, and Cardona-Escobar Citation2021), ethnic minorities often struggle with this ‘wealth’ due to the dominance of one national religion, culture and language. This study reveals that the Myanmar education system does not provide students from minority backgrounds with the opportunities that would allow them to possess intellectual and educational ‘wealth’, but creates numerous opportunities for their religions, cultures and languages to become invisible and hidden.

Despite the systematic issues in how diversity is positioned within school policies and practices, some teachers and school leaders are attempting to respond to the needs of ethnic minorities and minimise inequalities at the school level. This challenging venture is pursued within an education system based on the ideologies of the majority group reproduced in school curricula and policies. While teaching practices in Myanmar tend to be authoritarian (Cheesman Citation2003; Hardman et al. Citation2016), the participants of this study attempted to create a space to recognise the linguistic and cultural capital that the students already possess (Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022). The participants could only influence their classrooms and/or schools but made autonomous pedagogical decisions to maintain and increase students’ cultural capital (Bourdieu, Pierre, and Passeron Citation1977). The participants recognised that ethnic minority groups were discriminated against and addressed inequalities by allowing them to freely practice their religions and utilise their mother tongues in the classroom. While the participants acknowledged the structured and institutionalised social reproduction of the dominant group, they challenged these norms in small but significant ways.

There is a considerable risk that the students from minority backgrounds in Myanmar are learning to actively devalue their cultural capital. Simultaneously, there are teachers and school leaders who are attempting to negotiate with the system by creating spaces where students are recognised and celebrated in light of their existing capital. Such an approach is how knowledge and education can become decolonised (Hassan Citation2022; Prah Citation2017). The decolonisation of education begins with school leaders’ and teachers’ awareness and concern about the quality of learning of each student rather than compliance towards a system with power and seeming logical coherence. For instance, some teachers have little understanding of other faiths that are not prescribed in the curriculum because teachers, themselves, are products of social reproduction. In other words, the current system in Myanmar does not guarantee fair treatment for minorities and it depends on the choice of each teacher (Saito, Takasawa, and Tsukui Citation2022).

Conclusion

This study intended to examine how Myanmar school leaders and teachers understood and addressed the needs of students from diverse backgrounds in multicultural classrooms within the complex education system that promotes monolingualism and monoculturalism at every level of education. The key findings revealed that students from minority backgrounds struggled to gain legitimacy and build capital in an education system that does not acknowledge diversity, multiculturalism and multilingualism. In addition, while dominant ideologies in terms of ethnicity, religion and monolingualism are socially reproduced within and through curriculum and school and teacher practices in day-to-day learning, this results in inequalities among students (Apple Citation1992, Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Barnes Citation2021; Bishop Citation2014; Knoblauch and Brannon Citation1993). It is evident from this study that students from minority backgrounds need a more supportive and caring classroom as they need to cope with daily challenges in schools (Albeg and Castro-Olivo Citation2014; Amina, Barnes, and Saito Citation2022; Due and Riggs Citation2016). Despite the education system and policy embedding Myanmar’s dominant ideologies relating to culture, language and religion within all aspects of schooling, this study found that there were some teachers and school leaders who acknowledged the structured and institutionalised social reproduction of the dominant groups and were actively attempting to respond to the needs of ethnic minorities and minimise inequalities in small but meaningful ways at the school level.

Implications

This study contributes to the growing discussion around multicultural education and indigenous education in Myanmar. The findings of this study reveal that students from minority backgrounds struggle to maintain their social and cultural capital within the Myanmar education system. Therefore, it is imperative that policymakers acknowledge cultural, religious and linguistic diversity and develop more culturally responsive and inclusive education policies. Mother tongue-based education should be implemented particularly in ethnic minority regions. This study suggests a need to prepare and train both pre-service and in-service teachers for multicultural classrooms because their awareness and understanding towards diversity play a vital role in how they respond to students from minority groups and minimise the inequalities at school. The findings suggest that there are some teachers who have little understanding of other cultures and religions because the curriculum and textbooks do not incorporate the content and information of the minority groups. Therefore, this study proposes well-designed institutional-level professional development programmes to increase teachers’ awareness and understanding of diversity and multiculturalism. Additionally, this study further recommends that multicultural education professional development programmes are included in school policy and action plans to maximise the effectiveness of the training (Arphattananon and Anui Citation2021).

Future research directions

This study captured the perspectives and experiences of five participants, consisting of two school leaders and three teachers. Therefore, more comprehensive studies with a larger sample size are recommended to conduct in the future. Drawing on the work of Rosa and Flores (Citation2017), further investigation employing a Raciolinguistic framework is encouraged to investigate the historical and contemporary co-naturalisation of language and race in Myanmar. Since this study recommends embedding multicultural education in Myanmar teacher education, future research should explore its long-term effectiveness within a system that does not acknowledge diversity and promotes monolingualism and monoculturalism at every level of education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. EAOs are ethnic armed resistance groups against the Myanmar government for political autonomy and self-determination in their respective states and regions where they constitute the majority of the population. See (The Asia Foundation Citation2017, 14). https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ContestedAreasMyanmarReport.pdf for EAOs’ map.

2. Kachin is one of the major ethnic nationalities in Myanmar.

References

- Albeg, L. J., and S. M. Castro-Olivo. 2014. “The Relationship Between Mental Health, Acculturative Stress, and Academic Performance in a Latino Middle School Sample.” Contemporary School Psychology 18 (3): 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-014-0010-1.

- Amina, F., M. M. Barnes, and E. Saito. 2022. “Belonging in Australian Primary Schools: How Students from Refugee Backgrounds Gain Membership.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2026367.

- Anui, andArphattananon, T. 2021. “Ethnic Content Integration and Local Curriculum in Myanmar.” Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 14 (2): 155–172. https://doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-0060.

- Apple, M. W. 1992. “The Text and Cultural Politics.” Educational Researcher 21 (7): 4–19. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X021007004.

- Barnes, M. 2021. “Creating ‘Advantageous’ Spaces for Migrant and Refugee Youth in Regional Areas: A Local Approach.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42 (3): 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1709415.

- Barnes, M., F. Amina, and D. Cardona-Escobar. 2021. “Developing capital and a sense of belonging among newly arrived migrants and refugees in Australian schools: a review of literature (El desarrollo de capital y del sentido de pertenencia entre los migrantes y refugiados recién llegados en las escuelas australianas: una revisión de la literatura.” Culture and Education 33 (4): 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2021.1973221.

- Bishop, E. 2014. “Critical Literacy: Bringing Theory to Praxis.” Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 30 (1): 52–63.

- Bourdieu, P. 1961. The Algerians. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. translated by R. Nice. Polity Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503621749.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, J., J. Pierre, and C. Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. J. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buckingham, L. 2019. “Migration and Ethnic Diversity Reflected in the Linguistic Landscape of Costa Rica’s Central Valley.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (9): 759–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1557666.

- Burke, A., N. Williams, P. Barron, K. Jolliffe, and T. Carr. 2017. ”The Contested Areas of Myanmar: Subnational Conflict, Aid, and Development”. San Fransisco: The Asia Foundation.

- Cheesman, N. 2003. “School, State, and Sangha in Burma.” Comparative Education 39 (1): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060302565.

- Cheesman, N. 2017. “How in Myanmar ‘National Races’ Came to Surpass Citizenship and Exclude Rohingya.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 47 (3): 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1297476.

- Clarke, S. L., S. A. S. Myint, and Z. Y. Siwa. 2019. Re-Examining Ethnic Identity in Myanmar. Siem Reap: Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies.

- Clark, T., L. Foster, L. Sloan, and A. Bryman. 2021. Bryman’s Social Research Methods. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dubbeld, A., N. de Hoog, P. den Brok, and M. de Laat. 2019. “Teachers’ Multicultural Attitudes and Perceptions of School Policy and School Climate in Relation to Burnout.” Intercultural Education 30 (6): 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2018.1538042.

- Due, C., and D. W. Riggs. 2016. “Care for Children with Migrant or Refugee Backgrounds in the School Context.” Children Australia 41 (3): 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2016.24.

- Ferguson, J. M. 2015. “Who’s Counting?: Ethnicity, Belonging, and the National Census in Burma/Myanmar.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 171 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-17101022.

- Gao, F., C. Lai, and C. Halse. 2019. “Belonging Beyond the Deficit Label: The Experiences of ‘Non-Chinese Speaking’ Minority Students in Hong Kong.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (3): 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1497042.

- Go, J. 2013. “Decolonizing Bourdieu: Colonial and Postcolonial Theory in Pierre Bourdieu’s Early Work.” Sociological Theory 31 (1): 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113477082.

- Gubi, A. A., and O. Joel. 2015. “Impact of the Common Core on Social-Emotional Learning Initiatives with Diverse Students.” Contemporary School Psychology 19 (2): 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0045-y.

- Hardman, F., C. Stoff, W. Aung, and L. Elliott. 2016. “Developing Pedagogical Practices in Myanmar Primary Schools: Possibilities and Constraints.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 36 (sup1): 98–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2014.906387.

- Hassan, S. L. 2022. “Reducing the Colonial Footprint Through Tutorials: A South African Perspective on the Decolonisation of Education.” South African Journal of Higher Education 36 (5). https://doi.org/10.20853/36-5-4325.

- Hayden, M., and R. Martin. 2013. “Recovery of the Education System in Myanmar.” Journal of International and Comparative Education 2 (2): 47–57. https://doi.org/10.14425/00.50.28.

- Knoblauch, C. H., and L. Brannon. 1993. Critical Teaching and the Idea of Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

- Lall, M., and A. South. 2014. “Comparing Models of Non-State Ethnic Education in Myanmar: The Mon and Karen National Education Regimes.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 44 (2): 298–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.823534.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications.

- Lwin, T. 2019. “Global Justice, National Education and Local Realities in Myanmar: A Civil Society Perspective.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (2): 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09595-z.

- Prah, K. K. 2017. “The Centrality of the Language Question in the Decolonization of Education in Africa.” Alternation Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa 24 (2): 215–225. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2017/v24n2a11.

- Rodríguez, E. G., M. Boatcă, and S. Costa. 2016. Decolonizing European Sociology: Transdisciplinary Approaches. New York: Routledge.

- Rosa, J., and N. Flores. 2017. “Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective.” Language in Society 46 (5): 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000562.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Penguin Books.

- Saito, E., N. Takasawa, and A. Tsukui. 2022. “Transition of Schooling Education in Myanmar: A Comparative Institutional Analysis.” Globalisation, Societies & Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2063814.

- Skiba, R. J., R. H. Horner, C. G. Chung, M. K. Rausch, S. L. May, and T. Tobin. 2011. “Race is Not Neutral: A National Investigation of African American and Latino Disproportionality in School Discipline.” School Psychology Review 40 (1): 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087730.

- South, A., and M. Lall. 2016. “Language, Education, and the Peace Process in Myanmar.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 38 (1): 128–153. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs38-1f.

- Spivak, G. C. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, 24–28. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Stein, S., and V. D. O. Andreotti. 2016. “Decolonization and Higher Education.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by R. Peters, 1–6. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_479-1.

- Torres, C. A., and M. Tarozzi. 2020. “Multiculturalism in the World System: Towards a Social Justice Model of Inter/Multicultural Education.” Globalisation, Societies & Education 18 (1): 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1690729.

- United Nation. 2022. List of Least Developed countries. Accessed November 24. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/ldc_list.pdf

- Walton, M. J. 2013. “The ‘Wages of Burman-Ness:’ Ethnicity and Burman Privilege in Contemporary Myanmar.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2012.730892.

- World Population Review. 2022. Myanmar Population. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/myanmar-population