ABSTRACT

Migration has resulted in increasing teacher diversity in the teaching workforce in many countries. Yet, the prevailing perception in the receiving countries regarding who the teachers are and how they should be and act has made the professional transition challenging for immigrant teachers who do not fit into this frame. This study examines how immigrant teachers construct their belongingness to their receiving schools. Using a qualitative inductive approach, this paper reports on the experiences of 10 teachers who migrated from Asia to teach in Australia. Findings revealed that teachers’ sense of belonging occurred on a continuum and was co-constructed by their professional identity, vulnerability, and intercultural perspectives. We conclude by presenting the theoretical model developed from data in this study, its implications, and recommendations.

Introduction

Increasing and diversified global migration movements have resulted in schools with large, diverse student populations and, consequently, the proliferation of research and policies to serve the needs of diverse learners. However, what is less apparent and hence has received less attention is the growing diversity of the teaching workforce in many countries. Reports have documented the increasing teacher diversity and migration trend in recent decades (European Union Citation2015). Fuelled by teacher shortages in some developed countries and motivated by political and socio-economic reasons, teachers have moved away from their home countries to flee war and oppression and to seek better employment opportunities and standards of living in another country. Yet, past research has highlighted the significant challenges and differential treatment of immigrant teachers in their receiving countries (Ennerberg and Economou Citation2022; Yang Citation2022; Yip Citation2023).

A key challenge lies in overcoming the institutional and structural barriers that affect immigrant teachers’ employment opportunities in their receiving countries (Ennerberg and Economou Citation2022; Käck Citation2020; Roy and Lavery Citation2017) due to prevailing perceptions in the receiving countries regarding ‘how a teacher should be, act, and understand their work and place in the society’ (Sachs Citation2001, 15). Krause, Proyer and Kremsner (Citation2023) claimed that the expectations of specific desired ‘background and habitus and pedagogical ideas and work of a teacher’ (1) of the receiving countries have made the professional transition significantly more challenging for the immigrant teachers who did not fit into this frame. In some countries, local pre-service teachers who have yet to graduate from the initial teacher education program and have not attained teacher registration are recruited to address teacher shortages, while trained immigrant teachers are excluded from the profession (Krause, Proyer, and Kremsner Citation2023; Nigar, Kostogriz, and Janfada Citation2022; Victoria Institute of Teaching Citation2022). This paradoxical strategy calls into question a need to challenge the underlying assumption that only locally trained teachers with the desired habitus and localised knowledge are competent to teach our children (Krause, Proyer, and Kremsner Citation2023). On the other hand, teacher diversity offers a potential solution to address the evolving needs of diverse learners in many of our classrooms. Not only do they help to address the teacher shortages in many immigrant-receiving countries, but immigrant teachers have also been shown to offer better understanding and support and act as positive role models for migrant and minority students (Radhouane, Akkari, and Macchiavello Citation2022). They also help to heighten students’ intercultural awareness and sensitivity, defined as ‘the ability to discriminate and experience relevant cultural differences’ (Hammer, Bennett, and Wiseman Citation2003, 422). While some local teachers have been shown to operate in the ethnocentrism stages of defence and denial in Bennett’s (Citation2017) ‘Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity’ (Yuen Citation2010), those with bicultural and multicultural experience, such as those with migrant background, are more likely to implement culturally relevant pedagogy (Seidl Citation2007).

Past research has provided evidence of discrimination and marginalisation of immigrant teachers (Ennerberg and Economou Citation2022; Virta Citation2015). Some studies have also documented that issues of intercultural communication and ethnocentric worldviews of students adversely influence the teaching evaluation of immigrant teachers (Abayadeera, Mihret, and Dulige Citation2018). To integrate into the local teaching community, immigrant teachers have attempted to change their beliefs and values (Bense Citation2014; Reid Citation2014), pedagogical practices (Caravatti et al. Citation2014; Reid Citation2014), expectations of students’ behaviour (Jhagroo Citation2016; Miller Citation2018), and how they interact with students and their parents (Janusch Citation2015) to assimilate into the culture and discourse of teaching in their new teaching context. A recurrent theme in these studies is immigrant teachers’ feelings of ‘otherness’ and ‘outsiderness’ (McDevitt Citation2018; Rabadi-Raol Citation2020; Tarisayi Citation2023; Yip Citation2021) – feeling lonely, isolated and not fitting in and a general sense of not belonging to their new environment. While these have been identified as critical emotions related to immigrant teacher settlement and professional transition, their full complexity is rarely analysed. How immigrant teachers’ emotions of belongingness shape their professional transition remains unclear.

Against the backdrop of migration, in which social and cultural movements across national boundaries become commonplace, and the growing social dynamics of the teaching profession, this study examines how immigrant teachers construct their belongingness in their new teaching context. We argue in this study that understanding how immigrant teachers construct their belongingness to their receiving school is essential, not only for their smooth professional transition but also to ensure a committed teacher workforce to address the needs of diverse learners in the receiving society. This research contributes to understanding the emotional dimension of immigrant teachers’ professional transition, particularly the emotion of belongingness. This study also situates itself within inclusive education. In a school where inclusive education is practised, not only the students but also teachers from diverse backgrounds need to have a strong sense of belonging built on mutual respect and inclusion.

Theoretical background: belongingness

The construct of belongingness has been widely studied across disciplines. Levett-Jones et al. (Citation2009) describe belongingness as an experience that evolves in response to the degree to which an individual feels (a) secure, accepted, included, valued and respected by a defined group, (b) connected with or integral to the group and (c) that their (…) personal values are in harmony with those of the group (154). It is a subjective and dynamic feeling of social connectedness to a particular social group or organisation (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995; Hagerty and Patusky Citation1995; Halse Citation2018; Hurtado and Carter Citation1997), and involves a reciprocal relationship with the desired group that is built on shared experiences, beliefs, or personal characteristics (Mahar, Cobigo, and Stuart Citation2012).

Studies have shown that people who experience belongingness perform better mentally and physically (Li and Jiang Citation2018; Pesonen et al. Citation2016), while the feeling of not belonging can lead to feelings of distress, loneliness and anxiety (Carvallo and Gabriel Citation2006; Mellor et al. Citation2008; H. Pesonen et al. Citation2016). While most people have an inherent need to belong (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995), the extent of this need is specific to the individual (Kelly Citation2001; Sedgwick and Yonge Citation2008) and context-dependent (Caxaj and Berman Citation2010). As a dynamic phenomenon shaped by the interaction between environmental and personal factors, the construct of belongingness is particularly complex in the context of migration when new migrants disrupt existing norms and re-establish their sense of belonging to a new environment (Gamsakhurdia Citation2019; Halse Citation2018; Mahar, Cobigo, and Stuart Citation2012).

Research indicates that immigrants’ sense of belonging to the receiving society directly affects their well-being and satisfaction (Amit and Bar-Lev Citation2014). Those who perceive a higher level of belongingness to their host country feel more attached to the host society, are more proactive in forming meaningful relationships with people (De Jong Gierveld, Van der Pas, and Keating Citation2015), and feel safer and more comfortable in the host countries (Albert Citation2021; Juang et al. Citation2018). As such, belongingness is regularly used to indicate successful migrant integration (OECD/EU Citation2018).

Teachers’ belongingness to the workplace

Within the school context, belongingness has been chiefly studied from the students’ perspectives (e.g., Allen et al. Citation2018; OECD Citation2015; Pesonen Citation2016; Zengilowski et al. Citation2023). A high sense of belonging among students has been linked to improved learning outcomes and overall student well-being. In contrast, research exploring teachers’ belongingness in the school is limited in number. In these studies, teachers’ sense of belonging has been linked to motivation at work (Osterman Citation2000), improved co-teaching relationships (Pesonen et al. Citation2020) and overall well-being (Nislin and Pesonen Citation2018; Skaalvik and Skaalvik Citation2011).

As Pesonen, Rytivaara et al. (Citation2020) found, teachers’ workplace belonging is contingent on their relationships with colleagues, the school climate, and leadership. Teachers who enjoy respectful and trusting relationships with colleagues feel valued and accepted (Goodenow Citation1993; Hagerty et al. Citation1992) and support each other professionally (Rytivaara and Kershner Citation2012). This enhances their belongingness to the school and job satisfaction. On the other hand, negative relationships at work can cause emotional exhaustion and negatively affect job satisfaction (Skaalvik and Skaalvik Citation2011). Similarly, Bjorklund, Warstadt and Daly (Citation2021) found belongingness, relational trust, and self-efficacy positively associated with well-being. Teachers experience a stronger sense of belonging if their values align with the school’s (Skaalvik and Skaalvik Citation2011) and when they feel respected by students (Goodenow Citation1993). A positive school climate and perceived organisational support are critical to teachers’ sense of belonging (Kachchhap and Horo Citation2021). Likewise, teachers who received cognitive and emotional support from their school principals have reported an increased sense of belonging, job satisfaction and commitment, and well-being (Berkovich and Eyal Citation2018). Teachers who are happy in their school and who feel valued and connected to the school community are more likely to maintain a positive attitude towards teaching and create a supportive learning environment that encourages collaborative work and appreciates individual differences, thus promoting belongingness among students (Juutinen Citation2018; Pesonen Citation2016).

A handful of the limited studies on teacher belongingness have examined immigrant teachers’ sense of belonging to their schools. The few studies highlighted significant challenges immigrant teachers experience in navigating their positionalities and sense of non-belonging when teaching citizenship education (Kim Citation2021) and the tension around establishing their identity and belonging at the professional and societal levels (Savski and Comprendio Citation2022). This study seeks to advance the research in this area.

Methodology

Participants

Following the necessary ethics approval from the authors’ institution, invitations were sent to practising teachers who had undergone teacher training, received teaching qualifications, and worked as teachers in Asia regions before migrating to Australia to participate in this study. Participants were recruited online through professional networking groups for teachers, such as the Modern Language Teachers’ Association of Victoria. provides an overview of the participants’ characteristics.

Table 1. Summary of participants and their characteristics.

Data collection

Following informed consent, participants were invited to two interviews with author 1. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, and the semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded. The first interview focused on understanding participants’ backgrounds, and the second interview delved into participants’ stories to understand the complexity of their professional transition experiences. The interviews were guided by Seidman’s (Citation2006) interview protocol. Participants were encouraged to talk about ‘concrete details of their lived experience’ and ‘to reflect on the meaning of their experiences’ (Seidman Citation2006, 18) in relation to their professional transition. My initial contact with the participants to brief them on the project, the two interviews and the subsequent follow-up with participants for clarification of the transcripts allowed for prolonged engagement (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985) which helped to build rapport; I noticed participants being more trusting and forthcoming in the second interview.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and returned to participants for checking. In Vivo coding, where participants’ spoken words were coded, helped capture participants’ raw emotions and increased validity and reliability (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014). The resultant codes were then clustered into conceptual categories such as ‘social position of teachers’, ‘perceived teaching competence’, and ‘ethnocentric view’. The themes were generated following repeated reading of the transcripts and codes (Saldaña Citation2016). Pseudonyms were used to ensure anonymity when reporting the results and remove other identifying factors.

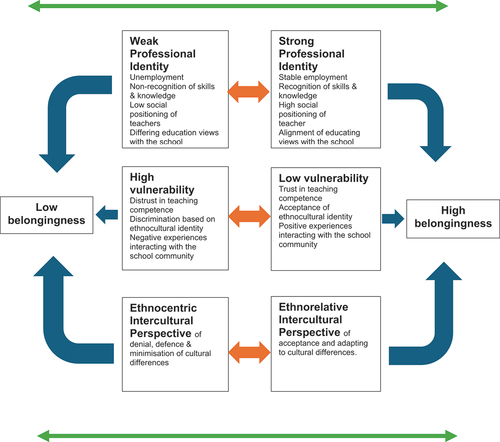

I understood that my researcher positionality could affect how I interpreted the data. To ensure trustworthiness and minimise my influence on the data, I took an introspective reflexive stance. I wrote memos recording actions, ideas, and feelings throughout the data collection and analysis processes, considering how my previous experience might influence my interpretation of the data. The memoing process raised my sensitivity to my prior assumptions, biases, and attitudes, which I made a concerted effort to put aside to minimise the influence on the data. The memos also documented emerging themes and potential biases. This helped to guard against assumptions and increase the credibility and reliability of the findings (Charmaz Citation2014). Analysis of the data revealed that the belongingness of the ten immigrant teachers in this study was predominately contributed by three constructs: (1) professional identity, (2) vulnerability, and (3) intercultural perspective. Each construct was further supported by its constituent elements. The three constructs worked in tandem to either support or undermine immigrant teachers’ belongingness to their school community. The contributing constructs to immigrant teachers’ belongingness and the constituent elements that support these constructs are discussed in the next section and summarised in .

Table 2. Key constructs and elements contributing to immigrant teachers’ belongingness.

Professional identity

The data in this study suggested that participants’ professional identity was critical in constructing their belongingness to the school community. The construct of professional identity was further unpacked into four elements: (1) employment status, (2) skills and knowledge, (3) perceived social position of teachers, and (4) beliefs and attitudes towards teaching and learning. Participants’ professional identity was affirmed when they were offered ‘longer-term employment’ (Renuka), when they were ‘valued by the school for their skills and knowledge’ (Kai Meng), when they were ‘respected by students, and parents look up to them for advice’ (Marilyn), and when their ‘views on education’ (Ansuha) and ‘expectations of the teachers’ role’ (Nara) were similar to that of the school.

By contrast, their professional identity was challenged when they lacked stable employment and considered themselves to be ‘just a replacement teacher’ (Angela) or when they had to ‘move from school to school every few months to search for jobs’ (Anusha). This professional identity was also compromised when they experienced a loss of teacher authority (Michiko and Nara) and were not respected by students and parents (Marilyn and Renuka). The situation was exacerbated when the receiving school failed to recognise their teaching experience in their home countries (Rehvinder), when they perceived that their ‘principal [was] not confident of their ability to teach well’ (Michiko), and when they needed to ‘relearn and make significant adjustments in their pedagogical practices to fit in’ (Michiko).

To fit in with their new school, participants reported making several changes. For example, Anusha spoke about ‘altering her views and beliefs towards education’, Angela and Kai Meng said that they ‘adjusted to new ways of teaching’, Marilyn and Janice shared that they ‘learnt to communicate with students slightly differently’, and Kate spoke about ‘adjusting to new norms and expectations in her school’. Participants believed these changes would facilitate them gaining acceptance as legitimate members of the school community and not be perceived as outsiders. This desire to be accepted into the school community was articulated by Janice in her interview:

The people in my school here are very relational. If you have not penetrated their circle, they will not include you. In the morning, I will go into the staffroom early just to mingle, make small talk and build relationships; I want to learn what they talk about regarding teaching, learning, and their students. I want to be involved and be part of their conversation.

The influence of broader policy and social-cultural context, and the personal and professional elements in teachers’ actions, emotions, and practices on their professional identity has been widely documented (Day and Kington Citation2008; Flores and Day Citation2006; Rodgers and Scott Citation2008; Zembylas Citation2004). As a fluid, dynamic, and evolving construct, teachers’ professional identity is constantly shaped by their interaction with the teaching context (Beijaard, Meijer, and Verloop Citation2004; Beltman et al. Citation2015). The data in this study provides evidence of this in the context of the changing teaching environment experienced by immigrant teachers.

This idea of individuals shifting their professional identity in the interest of fitting in and being accepted into a new environment is articulated by Hagerty and Patusky (Citation1995). The authors claimed that for individuals to feel they belong to an environment, they need to experience being valued and needed, perceive that their characteristics meet the expectations of the new environment and that their beliefs and values are in harmony with those of the group (Levett-Jones et al. Citation2009). Our data provide evidence that participants’ professional identity shift is motivated by their desire to belong to their new school community.

Vulnerability

Participants’ sense of vulnerability is salient in the process of their adjustment, which may influence the construction of their sense of belongingness to the schools. Data indicated that participants’ vulnerability was made up from three elements: (1) others’ perception of their teaching competence, (2) others’ response to their ethnocultural identity, and (3) their interaction with the school community. For example, Michiko, an immigrant maths teacher from Japan, reported feeling vulnerable when she saw that her principal was not confident in her ability to teach maths even though she had taught the subject for several years in her home country. Similarly, Rehvinder was made to feel vulnerable by her department head:

She did not want to give me the advanced English class because I wasn’t white. This is despite me teaching English and English literature for the last 20 years. It just showed that they did not trust my English!

Besides not trusting her English teaching competence, Rehvinder’s quote hinted that her ethnocultural identity might also have influenced the decision. Renuka, a teacher from Bangladesh, felt that because of her looks, she was in a more vulnerable position compared to her white immigrant teacher colleagues: ‘I am tested by local white parents all the time! But my colleague from Chile, also an immigrant teacher like me, has a much easier life. She didn’t get such treatment from students’ parents’.

The data in this study further revealed participants’ sense of vulnerability in their interactions with their school community. Several reported feeling fearful and intimidated when confronted with disrespectful students (Anusha, Kate, Marilyn, and Michiko), anxious when challenged by students’ parents (Michiko and Renuka), worried about being watched by their principals (Angela and Kate) and distressed when excluded by colleagues (Angela and Janice).

This aspect of the data is consistent with research that shows that teachers experience vulnerability when they encounter negative emotions in their interactions with people in the school (Zembylas Citation2004). Lasky (Citation2005) observed that vulnerability is influenced by the interaction between individual attributes and one’s external context. Teacher vulnerability refers to how teachers experience their interactions with other people in the school community and is said to encompass not only emotions but also their perception and interpretation of the experience (Kelchtermans Citation1996). While a feeling of vulnerability is generally the result of unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge about the norms and expectations of the new teaching context (Hargreaves Citation1998), the data show that the immigrant teachers’ sense of vulnerability was compounded when their teaching competence was questioned, when they were rejected based on their ethnocultural identity, and when they experienced negative emotions when interacting with people in the school community.

Participants such as Rehvinder and Michiko perceived their teaching competence undermined when they were not deployed to teach in their subject expertise. Renuka perceived that she was ‘tested’ and placed ‘under a bit of a microscope’ by her students’ parents because of her visible ethnocultural characteristics, in this case, her non-white appearance. Michiko perceived that she was ‘the target of complaints among parents’ because her accent was different.

The data illustrated that the participants felt appreciated and valued for their teaching competence when their ethnocultural identity was accepted, and when they were respected by students and trusted by students’ parents, their belongingness to the school community increased. Similarly, the assignment of an important task (e.g., Kai Meng was deployed as the maths teacher for a senior class) or appointment to a position of responsibility (e.g., Marilyn was appointed as a mentor teacher, and Kate and Michiko were appointed as department heads) made participants feel needed, trusted, and important, and therefore decreased their feeling of vulnerability and enhanced their sense of belonging.

The data show that vulnerability is a core emotion that defines participants’ feelings of belonging and not belonging (Wright Citation2015). It corroborates previous studies’ findings that feeling respected or receiving respect satisfies individuals’ core needs for belonging (Huo, Binning, and Molina Citation2010). It also attests to Bollen and Hoyle’s (Citation1990) argument that a sense of belonging is made up of both cognitive and affective elements, meaning that as well as the shared experiences and characteristics, an individual’s feelings that arise from interaction with the members of the group constitute an essential aspect of belonging.

Intercultural perspective

Participants’ intercultural perspectives, particularly how they reacted to cultural differences, was another prominent construct that shaped their belongingness. This study revealed that participants exhibit a range of responses towards cultural differences. For example, Kate was eager to be seen and treated similarly to her Anglo-Australian colleagues and, as such, was seen to deny her Asian identity:

It generally drives me nuts when people see me walking down the corridor and going ‘ni hao’ (translated into ‘how are you?’, a common greeting in Chinese). I always ignore them and pretend not to understand. Our mode of communication is in English, and that’s that. I generally forget that I am an Asian in my school. (Kate)

Some more recent immigrant teachers appeared to be defensive of their home countries’ teaching practices, perceiving them as superior and subconsciously engaged in stereotyping and ‘us vs them’ discourse. For example, Rehvinder found it appalling that some teachers in her school went into a class without a lesson plan and concluded that ‘teachers here were lazy and unprofessional’, and Nara complained that her students were ‘not as disciplined and polite as [her] students back home’. These participants developed a positive view of their cultural group and held a negative stereotype of their host country’s culture as they perceived that the education system, students, and teachers in their home country to be better.

However, as participants live longer in their receiving countries, many shift towards a more ethnorelative stance and are more accepting of cultural differences. Anusha said, ‘You don’t have to be Australian-centric and Asian-centric. The world is out there; there is no right or wrong. We just look at issues differently’. Anusha’s statements demonstrated her more ethnorelative view of accepting cultural differences.

Participants’ response to cultural differences can be understood through Bennett’s (Citation2017) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), which describes migrants’ intercultural perspectives along a continuum from ethnocentric views (denial, defence and minimisation) to ethnorelative views (acceptance, adaptation and integration). While Bennett’s model assumes a transitional and unidirectional movement in which individuals move from ethnocentric to ethnorelative as they become more interculturally sensitive, this study found that the process is more complex, shaped by participants’ day-to-day interactions with people around them – a parametric depending on the factors they interacted with. We noted that Bennett’s model did not consider how different factors may influence an individual’s intercultural sensitivity and competence, including the participants’ personality, motivation to migrate, and prior intercultural experience. Angela was a case in point; her sense of inferiority towards the ‘whites’ may have prevented her from taking the defensive stance evident in other participants. In fact, she was full of praise for the host culture. Bennett (Citation2004) calls this a sense of reversal, which holds the host country’s culture in higher esteem than native culture based on stereotypical knowledge. In this case, Angela’s stereotypical view was that the ‘whites’ were better and more eloquent than Asians.

The data generated from this study revealed that participants’ intercultural perspectives influenced the negotiation of their new teaching context and their desire and attitude towards cultivating belongingness. In this study, participants who maintained ethnocentric views of denial, defence and minimisation tended to experience more obstacles in establishing belongingness to their school community, while those who embraced a more ethnorelative stance of accepting and adapting to cultural differences appeared to have a stronger sense of belonging to their school community.

Discussion and conclusion

This study examined how immigrant teachers construct their belongingness to their school community. In particular, this study iedntifies the sense of belonging held by immigrant teachers from diverse backgrounds as an indispensable element of inclusive education. Findings from the study suggest that immigrant teachers’ belongingness occurs on a continuum and is shaped by their professional identity, emotions of vulnerability, and intercultural perspective, as shown in . It shows that immigrant teachers’ belongingness is co-constructed by their professional identity, vulnerability, and intercultural perspectives, and that each of these constructs is further supported by their constituent elements. The data further suggest that a weak professional identity, high vulnerability, and an ethnocentric intercultural perspective undermine immigrant teachers’ belongingness to their school community, whilst a strong professional identity, low vulnerability, and an ethnorelative intercultural perspective support immigrant teachers’ construction of belongingness. Each construct is further supported by the constituent elements that strengthen or weaken it.

Figure 1. The teacher belongingness model illustrating circumstances that undermine and support immigrant teachers’ construction of belongingness.

The data in this study suggest that a weak professional identity results from unemployment, non-recognition of immigrant teachers’ previous skills and knowledge, low social positioning of teachers, and differing education views with the school. A high level of vulnerability is caused by distrust in immigrant teachers’ teaching competence, experiences of discrimination and negative experiences when interacting with school community members. An ethnocentric view is manifested in the form of denial, defence, and minimisation of cultural differences. A combination of weak professional identity, high vulnerability and an ethnocentric intercultural perspective undermines immigrant teachers’ belongingness to their school community. On the other hand, a strong professional identity is contributed by stable employment, the recognition of skills and knowledge, a perceived high social positioning of teachers, and an alignment of education views with the school. Low vulnerability is associated with high trust in teaching competence, acceptance of ethnocultural identity, and positive experiences of interacting with people in the school community. These elements, coupled with an ethnorelative view of accepting and adapting to cultural differences, support immigrant teachers’ belongingness to their school community. Moreover, we observed that the constructs of professional identity, vulnerability and ethnocultural perspective are not binary. Instead, they occur on a continuum where individuals can possess a professional identity of varying strength, experience different degrees of vulnerability, and exhibit various behaviours on the DMIS. Likewise, the degree of belongingness also occurs on a continuum where an individual can experience varying degrees of belongingness.

The theoretical model, developed from the data in this study, contributes to the literature on the diversity of the teaching workforce by looking at it from the perspective of immigrant teacher belongingness and identifying the possible elements that contribute to their belongingness. While past studies primarily highlight the issues and challenges immigrant teachers face without providing an in-depth theoretical understanding of the constructs that contribute to the experience, the current study has conceptualised this experience in the context of belongingness and found that immigrant teachers’ belongingness to their school community is a complex and multifaceted construct that involves the interactions of their professional identity, the emotion of vulnerability, and intercultural perspective. Each of these constructs is further supported by specific elements (e.g., professional identity is supported by employment status, skills and knowledge, social status of teachers, etc.) as illustrated in . A change in any of the elements has a ripple effect on the construct, which then affects teacher belongingness.

At the national level, this theory could improve the teaching force’s quality. Increasing interest in the qualities that immigrant teachers can offer to their host societies means that countries are looking at how they can tap into the latent strength of immigrant teachers to improve the overall capacity of the teaching workforce. In Australia, Asian immigrant teachers offer a pool of readily available resources to drive the national imperative of engaging Asia and broadening and deepening Australian understanding of Asian cultures and languages. Understanding the constructs that shape immigrant teachers’ belongingness helps inform strategies and programs related to the recruitment, retention, and development of immigrant teachers. These could include programs to upskill and support immigrant teachers to learn about the Australian Curriculum and the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, as well as carefully constructed induction programs that introduce immigrant teachers to Australia’s Indigenous heritage and culture and their relevance to the local teaching context. These could help immigrant teachers transition more smoothly into their roles as teachers in Australian schools.

At the school level, translating this theory into action means paying attention to nurturing immigrant teachers’ sense of belongingness to the school. School leaders can play a fundamental role in engendering a positive work environment built on trust, respect, and recognition, which helps strengthen immigrant teachers’ professional identities and resilience and reduces their sense of vulnerability. Within the school, an understanding of this theory could ignite conversations on immigrant teachers and the broader issue of school culture, policies, and practices, all of which could lead to a more inclusive workplace culture and an overall positive school climate.

The theory developed in this study would open opportunities for future research in teacher professional transition. We acknowledge that the findings in this study are contextual and based on a small sample size of 10 Asian immigrant teachers in Australia. A larger data set could potentially bring out more generalisable conclusions. Future studies that focus on the professional transition experiences of teachers in specific regions and educational settings could add valuable new perspectives to the findings. We also note that our participants come from different regions in Asia that are socially and culturally diverse and are teaching in highly diverse and heterogeneous contexts in Australia. Hence, the participants’ experiences cannot be generalised for all Asian immigrant teachers in Australia. Despite these limitations, the findings are compelling and provide a valuable understanding of immigrant teachers’ belongingness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abayadeera, N., D. G. Mihret, and J. H. Dulige. 2018. “Teaching Effectiveness of Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers in Business Disciplines: Intercultural Communication Apprehension and Ethnocentrism.” Accounting Education 27 (2): 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2017.1414616.

- Albert, C. 2021. “The Labor Market Impact of Immigration: Job Creation versus Job Competition.” American Economic Journal Macroeconomics 13 (1): 35–78. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20190042.

- Allen, K., M. L. Kern, D. Vella-Brodrick, J. Hattie, and L. Waters. 2018. “What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 30 (1): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8.

- Amit, K., and S. Bar-Lev. 2014. “Immigrants’ Sense of Belonging to the Host Country: The Role of Life Satisfaction, Language Proficiency, and Religious Motives.” Social Indicators Research 124 (3): 947–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0823-3.

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments As a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117 (3): 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Beijaard, D., P. C. Meijer, and N. Verloop. 2004. “Reconsidering Research on teachers’ Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (2): 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

- Beltman, S., C. Glass, J. Dinham, B. Chalk, and B. Nguyen. 2015. “Drawing Identity: Beginning Pre-Service teachers’ Professional Identities.” Issues in Educational Research 25 (3): 225–245.

- Bennett, M. 2004. “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” In Toward Multiculturalism: A Reader in Multicultural Education, 2nd ed., edited by, J. Wurzel, 62–77. Intercultural Resource.

- Bennett, M. 2017. “Development Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In The International Encyclopaedia of Intercultural Communication, edited by Y. Kim, 1–10. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0182.

- Bense, K. 2014. ““Languages aren’t As Important here”: German Migrant teachers’ Experiences in Australian Language Classes.” The Australian Educational Researcher 41 (4): 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0143-2.

- Berkovich, I., and O. Eyal. 2018. “Principals’ Emotional Support and teachers’ Emotional Reframing: The Mediating Role of principals’ Supportive Communication Strategies.” Psychology in the Schools 55 (7): 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22130.

- Bjorklund, P., Jr., M. F. Warstadt, and A. J. Daly. 2021. “Finding Satisfaction in Belonging: Preservice Teacher Subjective Well-Being and Its Relationship to Belonging, Trust, and Self-Efficacy.” Frontiers in Education 6:6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.639435.

- Bollen, K. A., and R. H. Hoyle. 1990. “Perceived Cohesion: A Conceptual and Empirical Examination.” Social Forces 69 (2): 479–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579670.

- Caravatti, M. L., S. McLeod Lederer, A. Lupico, and N. van Meter. 2014. “Getting Teacher Migration and Mobility Right.” Education International. https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/25652:getting-teacher-migration-and-mobility-right.

- Carvallo, M., and S. Gabriel. 2006. “No Man Is an Island: The Need to Belong and Dismissing Avoidant Attachment Style.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32 (5): 697–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205285451.

- Caxaj, C. S., and H. Berman. 2010. “Belonging among newcomer youths.” Advances in Nursing Science 33 (4): 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ans.0b013e3181fb2f0f.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Day, C., and A. Kington. 2008. “Identity, Well-Being and Effectiveness: The Emotional Contexts of Teaching.” Pedagogy Culture & Society 16 (1): 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360701877743.

- De Jong Gierveld, J., S. Van der Pas, and N. Keating. 2015. “Loneliness of Older Immigrant Groups in Canada: Effects of Ethnic-Cultural Background.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 30 (3): 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-015-9265-x.

- Ennerberg, E., and C. Economou. 2022. “Career Adaptability Among Migrant Teachers Re-Entering the Labour Market: A Life Course Perspective.” Vocations and Learning 15 (2): 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-022-09290-y.

- European Union. 2015. “Study on the Diversity within the Teaching Profession with Particular Focus on Migrant And/Or Minority Background.” https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/ec-study-diversity-teaching-profession_en.

- Flores, M. A., and C. Day. 2006. “Contexts Which Shape and Reshape New teachers’ Identities: A Multi-Perspective Study.” Teaching & Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research & Studies 22 (2): 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002.

- Gamsakhurdia, V. L. 2019. “Proculturation: Self-Reconstruction by Making ‘Fusion cocktails’ of Alien and Familiar Meanings.” Culture and Psychology 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067x19829020.

- Goodenow, C. 1993. “The Psychological Sense of School Membership Among Adolescents: Scale Development and Educational Correlates.” Psychology in the Schools 30 (1): 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79:AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X.

- Hagerty, B. M. K., J. Lynch-Sauer, K. L. Patusky, M. Bouwsema, and P. Collier. 1992. “Sense of Belonging: A Vital Mental Health Concept.” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6 (3): 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9417(92)90028-h.

- Hagerty, B. M., and K. Patusky. 1995. “Developing a Measure of Sense of Belonging.” Nursing Research 44 (1): 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199501000-00003.

- Halse, C. 2018. “Theories and Theorising of Belonging.” Interrogating Belonging for Young People in Schools 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75217-4_1.

- Hammer, M., M. Bennett, and R. Wiseman. 2003. “Measuring Intercultural Sensitivity: The Intercultural Development Inventory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 27 (4): 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(03)00032-4.

- Hargreaves, A. 1998. “The Emotional Practice of Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 14 (8): 835–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0.

- Huo, Y. J., K. R. Binning, and L. E. Molina. 2010. “Testing an Integrative Model of Respect: Implications for Social Engagement and Well-Being.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36 (2): 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209356787.

- Hurtado, S., and D. F. Carter. 1997. “Effects of College Transition and Perceptions of the Campus Racial Climate on Latino College students’ Sense of Belonging.” Sociology of Education 70 (4): 324. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673270.

- Janusch, S. 2015. “Voices unheard: Stories of immigrant teachers in Alberta.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 16 (2): 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0338-4.

- Jhagroo, J. R. 2016. ““You Expect Them to Listen!”: Immigrant Teachers’ Reflections on Their Lived Experiences.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (9): 48–57. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n9.3.

- Juang, L., J. Simpson, R. M. Lee, A. Rothman, P. F. Titzmann, M. Schachner, L. Korn, D. Heinemeier, and C. Betsch. 2018. “Using an Attachment Framework to Understand Adaptation and Resilience Among Immigrant and Refugee Youth.” American Psychologist 73 (6): 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000286.

- Juutinen, J. 2018. “Inside or outside? Small stories about the politics of belonging in preschools.” Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. http://jultika.oulu.fi/Record/isbn978-952-62-1881-6.

- Kachchhap, S. L., and W. Horo. 2021. “Factors Influencing School teachers’ Sense of Belonging: An Empirical Evidence.” International Journal of Instruction 14 (4): 775–790. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14444a.

- Käck, A. 2020. “Swedish Teacher Education and Migrant Teachers.” Intercultural Education 31 (2): 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2019.1702329.

- Kelchtermans, G. 1996. “Teacher Vulnerability: Understanding Its Moral and Political Roots.” Cambridge Journal of Education 26 (3): 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764960260302.

- Kelly, K. M. 2001. “Individual Differences in Reactions to Rejection.” In Interpersonal Rejection, edited by M. R. Leary, 291–315, Oxford University Press.

- Kim, Y. 2021. “Imagining and Teaching Citizenship As Non-Citizens: Migrant Social Studies teachers’ Positionalities and Citizenship Education in Turbulent Times.” Theory and Research in Social Education 49 (2): 176–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2021.1885543.

- Krause, S., M. Proyer, and G. Kremsner. 2023. The Making of Teachers in the Age of Migration. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Lasky, S. 2005. “A Sociocultural Approach to Understanding Teacher Identity, Agency and Professional Vulnerability in a Context of Secondary School Reform.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (8): 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003.

- Levett-Jones, T., J. Lathlean, I. Higgins, and M. McMillan. 2009. “Development and Psychometric Testing of the Belongingness Scale-Clinical Placement Experience: An International Comparative Study.” Collegian 16 (3): 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2009.04.004.

- Li, C., and S. Jiang. 2018. “Social Exclusion, Sense of School Belonging and Mental Health of Migrant Children in China: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis.” Children and Youth Services Review 89:6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.017.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage.

- Mahar, A. L., V. Cobigo, and H. Stuart. 2012. “Conceptualizing belonging.” Disability and Rehabilitation 35 (12): 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.717584.

- McDevitt, S. E. 2018. Border Lives: Exploring the Experiences of Immigrant Teachers Teaching and Caring for Young Immigrant Children and Families. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Mellor, D., M. Stokes, L. Firth, Y. Hayashi, and R. Cummins. 2008. “Need for Belonging, Relationship Satisfaction, Loneliness, and Life Satisfaction.” Personality and Individual Differences 45 (3): 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Sage.

- Miller, P. W. 2018. “Overseas Trained Teachers (OTTs) in England: Surviving or Thriving? Management in Education.” Management in Education 32 (4): 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020618795201.

- Nigar, N., A. Kostogriz, and M. Janfada. July 28, 2022. “Desperate and Despondent: The Truth About the Way We Treat Immigrant Teachers.” EduResearch Matters. https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=13838.

- Nislin, M., and H. Pesonen. 2018. “Associations of Self-Perceived Competence, Well-Being and Sense of Belonging Among Pre- and In-Service Teachers Encountering Children with Diverse Needs.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 34 (4): 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1533093.

- OECD. 2015. “Students’ Sense of Belonging at School and Their Relations with Teachers.” PISA 2015 Results Students’ Well-Being 3:117–131.

- OECD/EU. 2018. Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2018: Settling In. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/Main-Indicators-of-Immigrant-Integration.pdf.

- Osterman, K. F. 2000. “Students’ Need for Belonging in the School Community.” Review of Educational Research 70 (3): 323–367. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003323.

- Pesonen, H. 2016. Sense of Belonging for Students with Intensive Special Education Needs: An Exploration of students’ Belonging and teachers’ Role in Implementing Support. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Pesonen, H., E. Kontu, M. Saarinen, and R. Pirttimaa. 2016. “Conceptions Associated with Sense of Belonging in Different School Placements for Finnish Pupils with Special Education Needs.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 31 (1): 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1087138.

- Pesonen, H. V., A. Rytivaara, I. Palmu, and A. Wallim. 2020. “Teachers’ Stories on Sense of Belonging in Co-Teaching Relationship.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 65 (3): 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1705902.

- Rabadi-Raol, A. 2020. ‘But What if You Just Listened to the Experience of an Immigrant teacher?’: Learning from Immigrant/Transnational Teachers of Color in Early Childhood Teacher Education. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Radhouane, M., A. Akkari, and C. G. Macchiavello. 2022. “Understanding Social Justice Commitment and Pedagogical Advantage of Teachers with a Migrant Background in Switzerland: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Multicultural Education 16 (2): 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-10-2021-0192.

- Reid, C. S. 2014. Global Teachers, Australian Perspectives: Goodbye Mr Chips. Springer.

- Rodgers, C., and K. Scott. 2008. “The Development of the Personal Self and Professional Identity in Learning to Teach.” In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: Enduring Questions and Changing Contexts, edited by M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, and K. E. Demers, 732–755, Routledge.

- Roy, S., and S. Lavery. 2017. “Experiences of Overseas Trained Teachers Seeking a Public School Position in Western Australia and South Australia.” Issues in Educational Research 27 (4): 720.

- Rytivaara, A., and R. Kershner. 2012. “Co-Teaching As a Context for teachers’ Professional Learning and Joint Knowledge Construction.” Teaching and Teacher Education 28 (7): 999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.006.

- Sachs, J. 2001. “Teacher Professional Identity: Competing Discourses, Competing Outcomes.” Journal of Education Policy 16 (2): 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930116819.

- Saldaña, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. Sage.

- Savski, K., and L. J. V. Comprendio. 2022. “Identity and Belonging Among Racialised Migrant Teachers of English in Thailand.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2046010.

- Sedgwick, M. G., and O. Yonge. 2008. “‘We’re it’, ‘We’re a team’, ‘We’re family’ Means a Sense of Belonging.” Rural and Remote Health 8 (3): 1021–1033. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH1021.

- Seidl, B. 2007. “Working with Communities to Explore and Personalize Culturally Relevant Pedagogies: Push, Double Images, and Raced Talk.” Journal of Teacher Education 58 (2): 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106297845.

- Seidman, I. 2006. Interviewing As Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. 3rd ed. Teachers College Press.

- Skaalvik, E., and S. Skaalvik. 2011. “Teacher Job Satisfaction and Motivation to Leave the Teaching Profession: Relations with School Context, Feeling of Belonging, and Emotional Exhaustion.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (6): 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001.

- Tarisayi, K. 2023. “The Colleague-Outsider Conundrum: The Case of Zimbabwean Migrant Teachers in South African Classrooms.” In The Making of Teachers in the Age of Migration: Critical Perspectives on the Politics of Education for Refugees, Immigrants and Minorities, edited by S. Krause, M. Proyer, and G. Kremsner, 133–148, Bloomsbury Academic.

- Victoria Institute of Teaching. August, 2022. Permission to Teach. https://www.vit.vic.edu.au/register/categories/ptt.

- Virta, A. 2015. “‘In the Middle of a Pedagogical triangle’—Native-language Support Teachers Constructing Their Identity in a New Context.” Teaching and Teacher Education 46:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.11.003.

- Wright, S. 2015. “More-Than-Human, Emergent Belongings: A Weak Theory Approach.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (4): 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514537132.

- Yang, P. 2022. “Differentiated Inclusion, Muted Diversification: Immigrant teachers’ Settlement and Professional Experiences in Singapore As a Case of ‘Middling’ migrants’ Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (7): 1711–1728. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1769469.

- Yip, S. Y. 2021. “Optimising the professional adaptation of Asian Australian immigrant teachers.” Unpublished PhD Thesis, Monash University. https://doi.org/10.26180/16550571.v1.

- Yip, S. Y. 2023. “Immigrant teachers’ Experience of Professional Vulnerability.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 51 (3): 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2023.2174075.

- Yuen, C. Y. M. 2010. “Dimensions of Diversity: Challenges to Secondary School Teachers with Implications for Intercultural Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.009.

- Zembylas, M. 2004. “Emotion Metaphors and Emotional Labour in Science Teaching.” Science Education 88 (3): 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10116.

- Zengilowski, A., J. Lee, R. E. Gaines, H. Park, E. Choi, and D. L. Schallert. 2023. “The Collective Classroom ‘We’: The Role of students’ Sense of Belonging on Their Affective, Cognitive, and Discourse Experiences of Online and Face-To-Face Discussions.” Linguistics and Education 73:101142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101142.