ABSTRACT

Situated in the curriculum space created by the recent enhancements to First Nations content is the opportunity for teachers to better connect with First Nations perspectives. Using constructivist theory methodology and drawing on two studies, a small qualitative school-based study of teachers who teach in the early years of schooling, and a large-scale study of professional development across two Australian states, the paper explores teachers’ preparedness to teach First Nations content. The tenets of critical literacy frame the discussion and are positioned as reflective tools that can be used to support the ‘settler teacher’ in self-reflection. Audio-recorded transcripts of planning sessions, a teacher survey, comments from feedback forms and researcher memos form the data sets. Findings from the study necessitate discursive practices for the development of teacher knowledge, dispositions, and confidence, and highlight the imperative for teacher critical self-reflection.

Introduction

The majority of Australian teachers who engage with the curriculum requirements around Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures are settler teachers. The purposeful adoption of the term settler teachers is used in this paper, to describe teachers from non-Indigenous backgrounds, whilst simultaneously refuting the colonial idea of Australia as Terra Nullius. Using the term recognises that the occupation of land, colonial massacres, the sovereignty claim of early settlers, assimilation supported by government policy, have resulted in a continuing legacy of harm to First Nations People. Moreover, the term confronts those of us from settler backgrounds, to acknowledge our link to invasion and oppression, and consider our positionality. Furthermore, reflecting on the notion of settler teacher can be a step towards decolonisation in education, involving the elevation of First Nations ways of knowing, being and doing, obstructing narratives of deficit, and promoting First Nations agency.

I came to this research, as a white, first-generation settler, whose European parents came to Australia, after the second World War. I recognise that the privileges I enjoy on Wurundjeri Country are embroiled with hidden stories of displacement, assimilation, violence, inequity and racism. These cause ongoing anguish. As an outsider, I cannot ever truly understand the trauma generated by colonialism, but I look towards education as an ameliorating force for truth-telling, critical reflection and reconciliation. It is in the spirit of acknowledgement and appreciation that this research took place.

There is evidence to show that Australian teachers lack the knowledge and confidence to teach First Nations curriculum responsibilities (Baynes Citation2016; Bishop, Vass, and Thomson Citation2019; Buxton Citation2017; Lowe, Moodie, and Weuffen Citation2021), but there is little current evidence that highlights the processes teachers engage with when planning for First Nations teaching, nor the problems or possibilities teachers face. Understanding the processes teachers engage with when planning to teach First Nations content can highlight where opportunities for knowledge and confidence development may lie. Moreover, there is a dearth of studies that contextualises the teaching of First Nations content in the early years of primary school. This research brings together data from two wider studies, shining the spotlight on early years teachers, as they consider, plan for and teach First Nations content. The synthesis of data from the two wider studies aims to address the question:

What processes, problems and possibilities do early years teachers face when planning for and teaching First Nations content?

Theoretical framework: the tenets of critical literacy

Critical literacy is situated in the broader field of critical pedagogy which draws attention to the ways power and knowledge are produced. Although there is no universally accepted definition of critical literacy (Freebody Citation2017; Luke Citation2012), tenets common to the scholarship of critical literacy can help its conceptualisation. These include power, knowledge, perspectives and truth (Giroux Citation2011; McLaren Citation2007) and can be used to consider First Nations curriculum content. These tenets relate to First Nations histories, but also offer hope for a positive positioning of First Nations content, that recognises the ongoing trauma caused by a colonialised past and works towards a reconciled future.

Power

Considering the juncture between literacy and power is fundamental when enacting critical literacy (Luke Citation2012). Power imbalance between dominant western knowledge and First Nation knowledge is reflected in the curriculum (Desmarchelier Citation2020). Power relations of inequity exist when sociocultural, linguistic and cultural diversity is underrepresented, discourses of deficit take place, or when teachers ignore the colonial legacy of dispossession, trauma and racism experienced by First Nations people (Abawi et al. Citation2019). Prioritising First Nations perspectives can subvert the current power imbalance.

Knowledge

There are profound benefits and complex challenges when including Indigenous knowledges in education (Desmarchelier Citation2020). Knowledge can be developed about First Nations people and also from First Nations people (Townsend-Cross Citation2018). Textual representation of First Nations voices can help to develop affective knowledge, such as empathy, and open new spaces for reflection and strengthen critical pedagogy (Zembylas Citation2018). The richness of First Nations knowledge can be represented through story, song and cultural artefacts (Desmarchelier Citation2020). However, when addressing knowledge, the recognition of ‘difficult knowledge’ is imperative (Britzman Citation2000). Australia’s ‘difficult knowledge’ involves historical violence, racism and oppression, that continues to impact First Nation people today. MacNaughton (Citation2005) argues that early childhood is a time for young children to consider notions of power and equity.

Perspectives

Ideologies, points of view, and social relations can be examined through the use of critical literacy practices. Such practices involve identifying diverse and multiple ‘voices’ in texts, searching for dominant and silenced voices and examining whose interests are served (Luke Citation2000). The ‘voices’ in the text present configurations of power, which is a central theme when examining multiple viewpoints (Luke Citation2000; McLaren Citation2007). Examining different perspectives places the engagement of texts within a wider set of discursive practices, which shape world views (Locke Citation2015). When the perspectives of groups that traditionally have been excluded from the dominant discourse of schooling are included, a step towards a justice-orientated education is taken (Giroux Citation1993). Historically, the Australian Curriculum has had shallow inclusion of First Nations perspectives and ignored the cultural diversity of First Nations people (Townsend-Cross Citation2004).

Truth

Curriculum, with its focus on knowledge, should be based in truth. Bedford and Walls (Citation2020) identify recent shifts in thinking that prioritise truth-telling. Drawing on the tenets of critical literacy may support teachers to focus on this new priority. Truth is sought through the examination of power relationships, understanding that knowledge is never neutral but organised by perspectives (Desmarchelier Citation2020). Australia’s truth can only be considered when black and white history are seen as shared and reflected upon critically (Shay and Wickes Citation2017).

The need for criticality

The current political climate in Australia holds contested views about First Nations history and experience, rendering the teaching of First Nations a political act (Bedford and Walls Citation2020). The scholarship of critical literacy is comfortable with the political notion of teaching and the subjectivity of curriculum (Freire Citation1970; Giroux Citation2011). The tenets of critical literacy can help to critique ideologies, investigate how social dominance is produced and interrogate dominant narratives (Freire Citation1970; Giroux Citation2011; McLaren Citation2007). These may offer teachers starting points for reflection, to understand the sociopolitical aspects they will teach and work towards transformative action in the classroom (Freire Citation1970).

The Australian curriculum

In the early part of 2022, eleven years after its initial release, a new version of the Australian Curriculum F − 10, Version 9 was released. Changes to the curriculum included an enhanced focus on First Nations content. This latest version of the curriculum retains the aim of ‘setting out expectations for what all young Australians should be taught regardless of where they live’ (ACARA Citation2023). Version 9 focuses on ‘deepening students’ understandings of First Nations Australian histories and cultures, the impact on – and perspectives of – First Nations Australians of the arrival of British settlers as well as their contribution to the building of modern Australia’ (ACARA Citation2023). Deepening First Nations content aligns with the vision for Australian education, as expressed in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration (Council of Australian Governments Education Council Citation2019), which calls for all students to learn about the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and addresses the goal of positive outcomes for all young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. Additionally, the curriculum enhancements speak to the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, first introduced in 2011, which require teachers to possess knowledge regarding, understanding of, and respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures (AISTL Citation2023).

The organization of the Australian curriculum: english

The architecture of the Australian Curriculum is tri dimensional. It includes the learning areas, which can be described as subjects or disciplines, for example, English, Mathematics, Science etc.; the general capabilities, which are broad skills and abilities developed across the learning areas; and three cross curriculum priorities, which have content embedded across the learning areas. The cross-curriculum priorities include sustainability, Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures. The learning areas, general capabilities and cross-curriculum priorities come together to create the content knowledge and skills aimed to meet Australian educational goals. In the learning area of English, references to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures are found in the content descriptors. Country/Place, Cultures and People are the main three organising concepts that frame the First Nations content. Reference to First Nations local knowledge is made salient. In English, First Nations content is linked to textual practices.

First nations content and the Australian curriculum: a welcomed inclusion or further colonization?

The curriculum enhancements to First Nations content are supported by professional bodies that hold interest in the field of English, such as the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE), the Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA), the Australian Literacy Educators Association (ALEA) and the Australian Association for the Teaching of English (AATE). These organisations advocate for the inclusion of First Nations content as evidenced by their position papers, research interests, and curriculum resources. Respect, truth-telling and reconciliation are embedded in the documents of these organisations, positioning First Nations content as an integral part of the teaching of English.

Scholars who write in the field of curriculum present some affordances that can arise when First Nations content and perspectives are included. For example, Parkinson and Jones (Citation2019) suggests that the curriculum can allow for the inclusion of local First Nation knowledge, histories and cultures, and can hold the opportunities for connections to be made to the backgrounds and cultures of all students. Carter (Citation2022) argues that the strengthening of First Nations content is a means for teachers to create a basis for meaningful dialogue through which students develop understandings to respectfully engage with histories, stories and cultures. Henderson (Citation2020) suggests that the English curriculum can support students to develop understandings through storytelling traditions of language use in different contexts and ameliorate the past exclusion of First Nations in education.

In contrast, many scholars critique and caution against the present inclusion of First Nations content (Bishop, Vass, and Thomson Citation2019). They see the content and the way it has been conceptualised as continuing colonial forces. For example, Harrison et al. (Citation2019) demonstrate how what counts as knowledge in the Australian Curriculum contrasts significantly to what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People consider to be knowledge. Weuffen and Willis (Citation2023) agree and present a disconnect between the curriculum, with its roots in western understandings of empirical knowledge, and discipline-based content which determines what will be included and excluded, and authentic integration of Indigenous perspectives. They suggest that the inclusion of First Nations perspectives, within the dominant western onto-epistemologies in curricula are a way of keeping the dominant western narrative, while appeasing the United Nations’ call for culturally responsive and respectful citizenship. Lowe, et al. (Citation2021) agree that the curriculum reflects western dominance, suggesting that the curriculum inclusions are a means of controlling content, pedagogic strategies and policy direction. Thus, colonial power is reinforced and there is diminished focus on systemic barriers to equitable outcomes for First Nations students such as racism, monolingual instruction, standardised testing, and schools’ disengagement with First Nations families. Lowe, et al. (Citation2021) question the purpose of First Nations curriculum inclusion, arguing that it acts to reconcile settler guilt, rather than acting as a means of decolonisation, obscuring First Nations learners and lacking the coherent narrative that supports Indigenous world views (Morrison et al. Citation2019). Parkinson and Jones (Citation2019) extend this idea, observing a lack of coherence in First Nations content, which results in silencing First Nations discourse.

Teachers are left to negotiate these opposing views, as they manage curriculum obligations. They need to find ways to encompass what is valued as positive – inclusion, prioritisation of First Nations voices, truth-telling and reconciliation, whilst working to invalidate the negative – pushing back on western epistemological dominance and resisting colonial forces. Interrogating the curriculum, to ask what and whose knowledge is represented, consider representation as power and ask whose truth is portrayed could be a starting point for teachers. Additionally, pedagogies that are culturally responsive, anti-deficit and incorporate First Nations ontologies, epistemologies and axiologies are needed (Guenther et al. Citation2023).

Curriculum interrogation and finding transformative pedagogies that go beyond learning content to developing social consciousness (Freire Citation1970) may be supported by drawing on the tenets of critical literacy. To date, the history of critical literacy in Australia has ignored First Nations knowledge and ways of knowing (Alford et al. Citation2022), but with foci on transformation and reflection, critical literacy may offer teachers a way to enact curriculum in ways that promote First Nations ways of knowing and being.

Working with the principles of critical literacy involves reflection (Freire Citation1970). Phillips and Archer-Lean (Citation2019) call for educators to reflect in a particular way, by recognising their standpoint. This involves acknowledging privilege, engaging empathetically and authentically reflecting. Their research on standpoint brings together critical literacy and First Nations perspectives.

Who teaches first nations content?

First Nations people engaging students with First Nations content is generally accepted as optimal (Bedford and Walls Citation2020; Dowling Citation2022; Henderson Citation2020). Dowling (Citation2022) argues that First Nations perspectives must come from First Nations voices and are best sourced from oral stories, where lived experience of First Nations people can be heard. Unfortunately, this is often not possible. Recent data from the Australian Council of Deans of Education (ACDE Citation2018) shows that approximately 2% of teachers, and 3.2% of the Australian population identify as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin (ABS Citation2020). Although this data does not consider the number of First Nations educators who work in education support roles, it does suggest that First Nations teachers are underrepresented in Australian education. These statistics show that most teachers teaching First Nations curriculum content are settler teachers. The term settler stems from the field of settler colonial studies (see the writing of Australian scholar Patrick Wolfe Citation1999), which extends the understanding of settlement from a group of people coming from one place to live in another, to settlement as invasion and occupancy with the intent of replacing the existing society with the new. Defining settlement in this way is conducive to seeing it as an ongoing process, rather than an event of the past.

When it is not possible to call on First Nations teachers or community members to support teaching, teachers turn to curriculum resources or texts by First Nations authors. In recent times there has been a proliferation of curriculum resources about First Nations content, and teaching resources developed by First Nations authors or developed by First Nations authors in collaboration with non-Indigenous authors. These have been well received by teachers (Weuffen and Willis Citation2023). However, as Lowe et al. (Citation2021) point out, this material is often presented by teachers who have ‘barely more knowledge of Indigenous issues than their students’ (76), resulting in the masking of Australia’s difficult past and ignoring perpetual issues of racism and inequity.

Teachers’ lack of knowledge about First Nations perspectives has been recognised (Bishop, Vass, and Thomson Citation2019; Buxton Citation2017; Lowe, Moodie, and Weuffen Citation2021) and furthers the potential for First Nation curriculum content to be addressed superficially. Lack of knowledge may lead inherent biases to be left unexamined (Shirodkar Citation2019). Furthermore, teachers have reported concerns about causing offence (Baynes Citation2016) and lack confidence negotiating areas of cultural sensitivity and teaching sensitive issues (Bishop et al. Citation2019). Britzman (Citation1998) presented the term ‘difficult knowledge’ to describe lived dilemmas, that is, living with knowledge that is confronting and painful to tolerate, and can be present in both curriculum and pedagogy. Australia’s difficult knowledge is recognised in the ‘Review Consultation Paper on the Cross-Curriculum Priority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures’ (ACARA Citation2021) which called out the lack of truth-telling about the experiences of First Nations People since the arrival of Europeans. Britzman (Citation1998) suggests that encounters with difficult knowledge should be more than witnessing it (118), it should be effective and transformative. Advocates for truth-telling urge Australians to go beyond recognising events of the past, and through truth-telling, use the wrongs of the past to act on the ongoing damage, which involves focusing on justice, sovereignty, and recognising the past’s affect on the present (Bedford and Walls Citation2020). Lack of knowledge and confidence, difficult knowledge along with the contentious placement of First Nations content as a cross-curricula priority (Salter and Maxwell Citation2016) call for sophisticated understandings to teach First Nations content.

It stands to reason that professional learning is important and without appropriate professional learning, teachers will avoid teaching First Nations content (Buxton Citation2017; Morrison et al. Citation2019). Yet, Morrison et al. (Citation2019) note that Australian teachers lack access to high quality professional learning related to First Nations, and many teachers who do participate in professional learning report that it has made little impact on their practice. Impactful professional learning is relevant, collaborative and supports teachers to reflect on, question and improve practice (Gonski et al. Citation2018). Professional learning should result in raised social consciousness and transformative practices.

Caution recommended around how teachers engage with first nations content

Henderson (Citation2020) warns that the inclusion of First Nations content in the curriculum does not provide an assurance that Indigenous perspectives will be understood or valued. Several scholars caution that shallow address of First Nations content results in tokenism, which can further a colonial narrative (Anderson, Yip, and Diamond Citation2022; Carter Citation2022; Dowling Citation2022). Assimilating First Nations values into the curriculum (Harrison et al. Citation2019), hiding truth-telling (Bedford and Walls Citation2020), deprioritizing First Nations knowledge (Bishop, Vass, and Thomson Citation2019; Moodie, Vass, and Lowe Citation2021) or treating it as ‘add ons’ which do not impact upon ‘real’ learning (Salter and Maxwell Citation2016), creating simplistic binaries or not taking into account local cultures are examples of tokenism (Frazer and Yunkaporta Citation2021).

A collegial approach to critical literacy may be a way of avoiding tokenism. Recent research has highlighted that when teachers collegially plan for and implement critical literacy practices, including naming oppressive social conditions, deconstructing power relations and redesigning curriculum to be more critical and reflective of lived realities, they are involving themselves in critical literate practices (Crawford-Garretta et al. Citation2020). Comber (Citation2015) argues that such teachers put power, equity and justice at the centre of their practice. Therefore, it can be inferred that intersecting critical literacy practices with First Nations perspectives, with a deliberate focus on the tenets of power, knowledge, truth and perspectives has the potential to mitigate tokenism. Critical literacy practices that recognise First Nations contributions help to develop empathy through truth-telling, carefully selected content and meaningful access to texts (Essop Citation2017; Zembylas Citation2018), which draws on First Nations authors who explore a wide range of stories, themes, characters and narratives, in different social, cultural and political contexts (Carter Citation2022).

The research

The studies and the participants

The research data comes from two separate studies. A synthesis of the data analysis and findings from both studies provides insights into the thinking of early years teachers, revealing the processes, problems and possibilities faced as they plan, teach and learn about First Nations perspectives.

1. The first constructivist grounded theory study used was contextualized in three early years classrooms, at one Catholic school in Melbourne. Five classroom teachers and 75 students who were in their first or second year of primary school participated in the study. This paper focuses on data obtained from the teachers. The school is largely multicultural, with more than half of the students speaking a language other than English, with Hindi, Tagalog and Mandarin the most commonly spoken home languages. All teachers were born in Australia, two teachers held Eastern European ancestry, two British and one held Asian ancestry. Only one Year 5 student, from the 237 students, identified as First Nations.

This study investigated the role critical literacy might play in the early years classroom. The teachers, working with curriculum content, selected Indigenous perspectives as their focus for critical engagement. None of the five teachers had previous experience teaching First Nations content from a critical literacy viewpoint. Only one teacher had participated in professional learning (a one-hour webinar) about First Nations content.

2. The second study was a large mixed methods case study that investigated the literacy professional learning of early years teachers (teachers of students in their first three years of schooling). This study involved 489 teachers working in Catholic schools, from two Australian capital cities, Melbourne (69 participants) and Brisbane (420 participants). The participants in this study engaged in seven days of professional learning about literacy in the early years of schooling. Approximately, one hour on one of the seven days was dedicated to a lecture style address, which introduced teachers to picture books by First Nations authors. Some of these texts represented traditional First Nations stories, some included First Nations characters, some presented biographies or autobiographies of First Nations people and some presented substantive topics. Substantive topics included racism, debates about Australia Day (which marks the 1788 raising of the British flag) and the Stolen Generations.

Using prompts that traversed the principles of critical literacy, such as power and multiple perspectives, the teachers were encouraged to think about the difficult knowledge represented in some of the texts. Time was given for collegial discussions and teachers debated the appropriateness of the texts for young students. The teachers were presented with the notion of the settler teacher and asked to consider if and how the curriculum might be addressed differently if taught by settler teachers or First Nations teachers and if taught to First Nations children, non-Indigenous children or both First Nations and non-Indigenous children. The teachers’ reflections were not formally captured, although many teachers chose to share some of their thinking when feedback was sought about the professional learning. The teachers’ feedback created a data set. Additionally, the teachers were asked to complete a four-question survey. The survey was administered electronically, conducted in real time during the professional learning and presented on a large screen to the teachers, so that they were able to see the group’s collective responses. The questions asked teachers if their school had made the teaching of First Nations perspectives a priority; the degree to which they felt supported through professional development; their confidence in teaching First Nations perspectives and the degree to which they believed they meaningfully engaged with First Nations content. The participants’ involvement with this data served as a prompt for further discussions.

The relationship between the two studies

Codes from the first study revealed several themes, including teacher knowledge, acknowledgement of ‘settler teacher’, confidence and critical engagement with texts. These themes, which emerged in the small first study, could be further examined through the second large-scale study, which included over 400 participants. Survey data and feedback from the second study provided an ‘at-a-glance’ view of teachers’ knowledge, confidence and engagement with First Nations texts. This study demonstrated the applicability of the emerged themes and helped to develop more comprehensive insights.

Methodology

As the research involved humanistic aspects and presentation of the human world through the perspectives of individuals, qualitative analysis was conducted (Denzin and Giardina Citation2015). The ‘desired knowledge’ (Gough Citation2002) for this research was produced from ‘findings arrived from real-world settings where the “phenomenon of interest unfold naturally”’ (Patton Citation2002, 39). The real-world settings were the teachers’ planning sessions and off-site professional learning settings, where teachers went about the core business of their work. The ‘desired knowledge’ involved the interpretation and description of individuals’ talk and action, as participants responded to one another, shared thinking, engaged in activities, participated in a survey to reflect on their practice or offered comments on anonymous feedback forms.

Constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2014) was selected as the methodology for creating the systematic way of working (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2015). Charmaz’s positioning of constructivist grounded theory differs from previous conceptualisations of grounded theory, with coding a main point of divergence. Charmaz holds a flexible view on coding, which insists on being open to emerging categories through a process involving:

initial coding

focused coding

theoretical coding

theory construction

Constructivist grounded theory, as presented by Charmaz (Citation2014) provided the following affordances:

Placing participants’ contributions as central to the research: From the onset, participants’ data gives voice to the research. The participants were all teachers. Australian academic, Peter Freebody (Citation2016) advised that the teachers should add their voice to research, stating, ‘There are things that teachers know that researchers don’t know’. Coding of the data is guided by the idea of patterns of behaviour or processes, which link the meaning constructed by the researcher, through the development of theoretical understandings to the participants.

Participating in constant comparison: A key feature of constructivist grounded theory is the drawing out of commonalities, which is useful as the research questions called for the examination of practices. This process is inductive, comparative, emergent and open-ended. It involves the constant comparison of data to other data and to the codes constructed through the analytical process.

Flexible guidelines: Formulaic prescriptions are avoided. Research begins with the data and constructivist grounded theorists can pursue hunches by ‘following up on interesting data in whatever way they desire’ (Charmaz Citation2014, 3). Data can serve as a starting point for further data collection. Data from the first study inspired the data collection from the second study, to provide insights about the findings on a wider scale.

Memo writing: The process of memo writing during and after data collection supported analysis starting alongside data collection. Additionally, memo writing ensures researcher reflection, encouraging openness to emerging themes. Charmaz (Citation2014) states, ‘the theory depends on the researcher’s views; it does not and cannot stand alone’ (239). Memo writing brings the researcher closer to the data.

Theory building rather than testing: Urquhart (Citation2013) notes the strong focus on ‘theory building rather than theory testing’ (10). Findings emerged from the data, rather than through the testing of a theory.

Integrity of analysis: Inherent in the methodology is reflexivity, which is desired above neutrality (Charmaz Citation2014). A constant process of reflexivity was embarked upon, involving self-questioning. Each code, be it theoretical, focused or initial can be traced back to the original data from which it emerged, ensuring the methodology was robust and transparent.

Data sources

From the school-based study involving five teachers from three early years classrooms, the following data sources were collected.

Four one-hour planning meetings audio-recorded, transcribed and coded.

Researcher memos written during and after each observed session added to the data through the process of constant comparison and coding.

From the study involving teachers and leaders and literacy professional development, two data sources were collected.

A four question online survey, using the online data gathering tool, ‘Poll Everywhere’, which involved responses given on a 3-point Likert scale. This survey was administered during the professional learning, in the session before the content around First Nations texts was delivered. 489 participants responded to the survey.

Responses from participants written on anonymous feedback forms asking about participants key learning. Many participants chose to reference First Nations in their comments, although no specific questions were asked about this content.

The research process

Constructivist grounded theory methodology begins with the immediate coding of the data. This process of analysis helps to theorise the processes involved rather than simply providing description (Urquhart Citation2013). Small categories of data are labelled, which help to categorise, summarise and account for each piece of data. The reduction of data to small fragments is an essential part of constructivist grounded theory and is completed through line by line and word by word coding.

The audio-recorded transcriptions, interviews, planning documents and researcher memos resulted in 210 constructed codes. These included codes constructed from the data involving the students, which are not included in this paper. Most of codes were expressed as gerunds, which resulted from interrogating the data by asking ‘what is happening?’ and then to move beyond simple description ‘how is it happening and why?’. In vivo codes were used where possible, across all levels of coding, as these helped to build an understanding of participants’ thinking. In vivo codes preserve the participants’ meanings, as they use the participants’ own words (Urquhart Citation2013). These codes provide authenticity and closely connect the participants to the data (Charmaz Citation2014).

Following the initial data coding and constant comparison of the codes, similarities and differences were noted. This resulted in the creation of new codes, or focused codes. The creation of focused codes brings the researcher further into the data, whilst moving more into conceptual thinking. Twenty-three focused codes were developed. Focused codes were created using gerunds and where possible in vivo codes were used to keep the participants’ voices close to the data. Initially, the codes were created without consideration given to the research questions, but then examined again in light of the research questions. The intensive memo writing that accompanied the creation of the focused codes was also used to help match the codes to the research questions. Focused codes were grouped and regrouped to identify the themes, patterns and concepts which formed the theoretical understandings.

Data coding and analysis

Data set: transcription of teacher planning sessions

Data from the teachers’ planning sessions highlighted the importance of dialogic encounters for teachers to enact critical practice. A sample of the coding of this data is shown in .

Table 1. Initial and focused codes.

Collegial planning – teacher knowledge and confidence building

Collegial planning played a significant role in identifying the socio-political aspects of teaching First Nations content and provided the space for teachers to work critically. The teachers’ need to act with sensitivity was evident. They recognised that First Nations content involved difficult histories and was contentious. ‘Difficult knowledge’ was often assumed, for example, through reference to the Stolen Generations without explicit naming of the events. Critical literacy practices involve naming the issue, problematising and renaming (Freire Citation1970). The main issue named involved the appropriateness of ‘Difficult knowledge’ for young children, a point debated by the teachers, with the conclusion that young children should be supported to understand some of Australia’s difficult history. First Nations displacement, racism and the Stolen Generations were the issues the teachers felt their students should know about and these were seen as topics for future teaching. A consensus was reached to teach about the historical meeting of settler John Batman with the First Nations people who lived in the area we now call Melbourne, the Wurundjeri people. Once this decision was made, the issue of First Nations displacement became more prominent.

The tenets of critical literacy were embedded in the teachers’ discussions. Discussions about displacement referenced issues of power. The teachers used online library resources to ensure factual accuracy, developing their own knowledge and demonstrating their commitment to truth. They were aware of different perspectives involved in the history they were preparing to present to their young students and used these to problematise the meeting between the Wurundjeri people and John Batman. Pedagogic decisions included student involvement in dialogue and drama which created opportunities for students to ‘rename’ the issues of displacement and racism by offering counter narratives.

Planning discussions, although useful for teacher collaboration and for the development of shared understandings, missed areas of importance. Moodie and Patrick (Citation2017) argue that sovereignty has significant relevance for First Nations people but is often forgotten or avoided by settlers. Similarly, reference to reconciliation, which is a curriculum goal and a broader societal goal (see First Nations National Constitutional Convention and Central Land Council, Australia, Citation2017. ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’) was seldom mentioned by teachers. As Moodie and Patrick (Citation2017) point out, avoidance of the areas of significance to First Nations People, such as sovereignty, politics and history can create an essentialization of First Nations people that reduce them to cultural artefacts. This later point was one the teachers explicitly wanted to avoid, as their goal was to teach First Nations perspectives with more depth and richness than they had taught before.

Teachers shared their inexperience in teaching First Nations content and lamented the lack of professional development in the field. The lack of expertise in the group inspired the collective goal of developing professional knowledge, and the shared planning helped to improve the teachers’ confidence. Lack of knowledge and confidence has been identified in previous research (Booth and Allen Citation2017; Buxton Citation2017; Moodie and Patrick Citation2017; Salter and Maxwell Citation2016).

Data set teacher survey

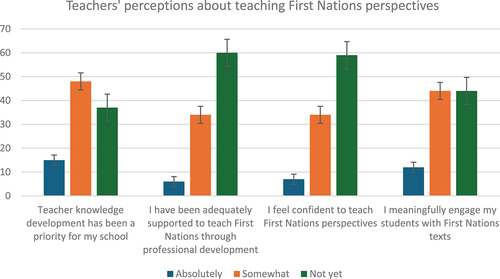

Data from the second study included a short survey conducted in real time during teacher professional learning. These results aligned with the findings from the first study and from previous research (see Booth and Allen Citation2017; Buxton Citation2017; Moodie and Patrick Citation2017; Salter and Maxwell Citation2016) that demonstrate low levels of teacher knowledge, confidence and support in teaching First Nations content. See .

Approximately half of the participants reported that teacher knowledge had been ‘somewhat’ of a school priority and nearly 40% reported it had not yet been a priority. This result is surprising given that Indigenous perspectives is a cross-curricula priority and has been since the conception of the Australian Curriculum more than a decade ago. Additionally, 60% of teachers reported that they did not feel they had been adequately supported through professional learning to teach First Nations perspectives, revealing a need for support.

The perceived lack of support for professional development and the lack of prioritisation of First Nations perspectives may be linked to the teachers’ level of confidence and their ability to meaningfully engage their students with First Nations literature. 59% of teachers stated they are not yet confident to teach First Nations content and 44% of teachers did not think they were yet able to teach First Nations texts meaningfully.

This data suggests a correlation between teachers’ knowledge, confidence and professional learning to teachers’ perceptions of the way they meaningfully engage their students with First Nations texts. Additionally, this data reveals the need for targeted professional learning about First Nations perspectives for Melbourne and Brisbane Catholic education teachers.

Data set: teacher feedback forms following professional learning

Other data from the second study included participants’ feedback forms, following the professional learning. The forms asked participants to comment on content they found relevant and their key take-away messages.

Early years teachers’ positive attitudes to teaching first nations perspectives through texts

65% of the participants referenced the one-hour lecture style input that discussed how teachers may engage young children with texts by First Nations authors and how Indigenous perspectives can be addressed in the early years classrooms. Nearly all of the comments were positive, reflecting interest in the area of First Nations content and expressing appreciation that time was allocated for discussion. Many comments indicated the teachers’ desire to include more First Nations content, particularly texts written by First Nations authors and signalled the importance of First Nations texts in the teaching of literacy.

Really enjoyed learning about Indigenous perspectives. Very thought provoking and really good discussion on my table.

The focus on Indigenous perspectives challenged my thinking and lead to great discussion.

I want to incorporate Indigenous authors.

Indigenous perspectives has become an area for my own professional knowledge.

Providing books and resources to use for Indigenous perspectives was good.

Finding about where the author is from.

The importance of teaching Indigenous perspectives and giving it the time and respects that it needs.

First Nations books need to be integrated into literacy.

Indigenous texts are a must when sharing rich stories.

I want to incorporate Indigenous voice into more learnings.

The content about First Nations really stimulated my thinking about how I can teach.

Need to respectfully read First Nation authors to teach about First Nations Cultures and People.

I will use First Nations texts.

Like the data from the planning sessions in the first study, this data demonstrates the teachers’ aspirations to respectfully engage with First Nations perspectives.

Engaging (or not) with difficult knowledge

The notion of the settler teacher was referenced by 2% of the participants. One comment signalled the need for settler teachers to take responsibility and address First Nations issues.

Settler teachers need to step up with Indigenous issues.

Another comment was declarative, with the participant stating their settler status.

I am a settler teacher!

Some comments signalled the need for further learning and thinking. For example

Indigenous perspectives are difficult to teach when not feeling confident.

Who is a settler teacher?

I have to educate myself about Australian history.

Always be mindful of your own positionality and bias.

How do I acknowledge Australian history in a respectful way that acknowledges First Nation perspectives and those of the early settler?

Even though truth-telling and difficult knowledge were presented in the lecture-style content delivery and participants were introduced to picture books that could be used to address difficult knowledge with young children, no participant referenced difficult knowledge. This may suggest that when First Nations children’s literature is presented to early teachers, they may find it more favourable to focus on positive aspects such as cultural diversity or the aesthetics of the text, rather than on difficult knowledge. The teachers in the first study did not begin discussions with children’s literature, but with history and more readily referenced difficult knowledge.

Data set: researcher memos

Research memos were taken during both studies, and in line with constructivist grounded theory were coded and became research data. Some examples of memos are listed below.

Seeking depth

Teachers are ready to launch into something meaty. They know that students can be involved in literacy that goes beyond decoding.

Teachers’ willingness to teach First Nations content from critical perspectives was evident. ‘Something meaty’ represents issues of substance, such as discrimination, which traditionally had not been part of what teachers taught to early years students.

Mara is committed to working with the themes of visible respect, as a means of addressing discrimination. There was quite a bit of talk around how this theme and other themes (the teachers called ‘big issues’) would be made accessible to students. Often the term ‘looking through the eyes of others’ was used.

The tenets of critical literacy were often embedded in the teachers’ ways of working. Mara’s comment in the memo above demonstrates the importance of viewing issues through multiple perspectives. In contrast, the memo below illustrates that at times, the teachers were lacking criticality. This was particularly so when they attempted to divorce themselves from the events of the past, reducing First Nations perspectives to content.

I didn’t pull children off the banks. Burden of the forefathers. I’m not responsible. There is obvious tension here, at the adult level – wanting to recognise difficult knowledge, but not wanting to be linked to it personally.

Researcher memos highlighted how the teachers established themselves as teachers of First Nations content, but the process was not an easy one, with some biases remaining unexamined.

Discussion

Teachers’ ways of working reveal the processes necessary for engagement with First Nations content. In turn, problems or challenges emerged and possibilities for better future engagement unfolded.

Engaging in professional dialogue

Collegial discursive practices can positively impact professional learning, with teachers’ planning sessions as valuable sites for professional dialogue. Although the main aim of planning is a practical one, that is, to organise what will be taught and how, discussions allowing teachers to share ideas, table difficulties or confusions and ask questions can have a positive effect on knowledge, confidence and dispositions. Additionally, dialogue during planning sessions has the potential to raise teachers’ levels of social consciousness. For example, when discussing the meeting between the Wurundjeri people and colonists, different perspectives were considered, power inequity was raised, and cultural knowledge discussed.

School structures supported teacher discourse. Time was allocated for weekly collaboration, teachers worked within a culture of shared responsibility for student outcomes, and evaluation of units of work was common practice. Furthermore, teachers maintained high-quality collegial relationships. However, despite the degree of perceived comfort and trust, there was little evidence of teachers challenging bias. For example, comments to abolish settler guilt were left unexamined. Similarly, failing to address comments about ‘taking on the burdens of the forefathers’ and ‘not feeling guilty’ positioned First Nations content as a problem of the past. Unlike the discursive practices of the planning sessions, where the tenets of critical literacy emerged organically from the teachers’ discussion, the teachers involved in professional learning were led by the facilitators to focus on issues of power, knowledge, perspectives and truth. Raising social consciousness was planned for through a sequence of lecture presentations, facilitated discussion and exploration of First Nation texts. With this group of teachers, a greater degree of self-examination and reflection was noted. Firstly, many teachers indicated the desire to further their understandings, some named settler discomfort and challenge, and many demonstrated that they valued the time to discuss their challenged thinking with their colleagues. Professional dialogue is problematic if biases are not challenged and holds the potential to reinforce stereotypes. Exploring standpoint presents a possibility, as noted in the teachers’ feedback sheets. Although confronting for some teachers, this process was seen as transformative, and increased teachers’ enthusiasm to learn and teach about First Nation perspectives.

The need for raising critical consciousness suggests that planning for the teaching of First Nations perspectives cannot be approached by settler teachers in the same way as other curricula. Critical reflection to address biases and recognise settler privilege must be an ongoing process and followed with transformative action.

Facing substantive issues head on

Truth-telling is now recognised in the curriculum, so difficult knowledge can no longer be ignored. Violent conflict, land acquisition, eugenics, the Stolen Generations, racism, exploitation, and injustice which had experienced curriculum exclusion (Stone Citation2020) are substantive topics to address. As well as historical content, topics that hold divided community opinions around contemporary issues, such as sovereignty and reconciliation may present as ‘difficult knowledge’. ‘How do we go beyond teaching the Rainbow Serpent?’ asked a teacher during a planning session, indicating an awareness of Indigenous perspectives as more than sharing cultural stories. Moving beyond the safe space of culture and stories, enters the realm of substantive topics. If not named, explicitly addressed and reflected upon, the danger arises of perpetuating the ‘cultural gap’ (Hogarth Citation2022), ignoring or creating a shallow representation of First Nations knowledge, histories, Peoples and cultures.

Implications for professional dialogue

Discursive practices, both initiated by teachers and facilitated in formal professional learning settings, have the potential to challenge teachers’ thinking, develop knowledge, create positive dispositions and inspire teaching. However, without a clear process for reflection, the degree to which teachers can deeply reflect on First Nations perspectives, identify (and perhaps challenge) their standpoint, consider substantive issues as adults and think about how these might be introduced to young children is left to chance and open to tokenism. Using a critical lens can help to move beyond just presenting aspects of culture involves engaging with issues of power, discrimination and colonialism (Morrison et al. Citation2019).

A suggested framework for reflection

Reflection promotes transformative learning (Freire Citation1970). A set of questions developed from the teachers’ dialogue and framed by the tenets of critical literacy has been framed for reflection. The questions can be used by individuals or as discussion prompts and are designed to help move beyond First Nations curriculum content, to the realm of substantive topics.

Power

What is the social issue? This could be a problem, issue, area that has not been explored or one that needs to be challenged.

What opportunities are there to hear First Nations voices?

Knowledge

How is the content important to First Nations individuals, groups and all Australians?

What First Nations knowledge can I learn from? Including, local knowledge of Country.

Why is this topic relevant for my students?

Perspectives

What is my current thinking about the content?

How does being a settler affect my thinking?

What areas of controversy or social sensitivity exist? How might I address these with colleagues or students?

Truths

What are my biases and how will they affect how or what I teach?

Where can I seek more information?

Such a framework creates a starting point but cannot be considered sufficient, as it does not include First Nations voices. It has to be recognised that First Nations Peoples will determine what knowledge is important, what knowledge should be shared, what representations should be made, and what relationships can be built. Teachers should look to their education departments, communities and local First Nations leaders, for guidance in how they can best listen to First Nations voices. The framework needs to be considered within the context of First Nations representation and with genuine desire to see, listen and respond to First Nations People. The process for including these aspects to the framework will need to be contextually specific and the ultimate priority.

Limitations

A major limitation of this research is its lack of First Nations representation. The study involved a settler researcher investigating the thinking and practice of settler teachers. Incorporating First Nations representation at all stages of the research would have made the research more robust and perhaps illuminated areas missed. Additionally, the way the teachers engaged through dialogue may not reflect their true thinking or experience, but rather reflect how they wanted to be seen by their colleagues. Finally, as the data collected during the teachers’ planning occurred in real-time and was valuable for understanding the process of planning to teach First Nations perspectives, it did not allow opportunities to investigate in depth the teachers’ ideas or meanings behind their contributions.

Conclusion

Teaching First Nations perspectives requires sophisticated understandings that go beyond knowing content. It involves recognising the ongoing effects of colonialism and addressing overt and hidden racism and discrimination. It involves facing difficult knowledge. Teachers are in the privileged position to educate society and therefore hold responsibility for ensuring students learn about the Country, Peoples and land on which they live. To do so teachers also need to be learners, with ears open to First Nations voices and hearts open to relationship building. Previous scholarship recognises the complexities and warns about reducing history, cultures and people to curriculum content descriptors. This research shone the spotlight on early years Catholic teachers, across two Australian states, who collectively expressed aspirations to meaningfully teach First Nations perspectives but lacked confidence and knowledge. Some of these teachers recognised their ‘settler’ status and made personal commitments to deepen their understandings. Others hold unexamined biases. Discursive practices were highlighted in this research as supportive to developing knowledge, dispositions and confidence. However, without the support of a framework for discussion and opportunities made to hear First Nations voices, engagement with discursive practices may not target the areas necessary for transformation. The research reported in this paper centred on planning and professional learning. Pedagogy, practice and the degree of classroom transformation need to be investigated further to obtain fulsome understandings. Furthermore, a unit of work or attendance at a professional learning is not enough, individual teachers, schools and education systems need to look for better ways of engagement with local First Nations people and leaders, act against racism and discrimination, listen to First Nations voices about what is most important to them and powerfully engage their students through authentic relationships. Early years settler teachers who are ready to meaningfully address First Nations perspectives can draw on the tenets of critical literacy, as starting points. In doing so, they confront their standpoint on difficult knowledge and make decisions about the appropriateness of substantive issues for their young students. As a teacher stated: ‘Settler teachers need to step up with Indigenous issues’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abawi, L. A., M. Fanshawe, K. Gilbey, C. Andersen, and C. Rogers. 2019. “Celebrating Diversity: Focusing on Inclusion.” In Opening Eyes Onto Inclusion and Diversity, edited by S. Carter. Toowoomba: University of Southern Queensland.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2020. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Census. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people-census/latest-release.

- ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). 2021. “Cross-Curriculum Priorities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures: Consultation – Introductory Information and Organising Ideas.” Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/7137/ccp_atsi_histories_and_cultures_consultation.pdf.

- ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). 2023. Aboriginal Histories and Cultures Cross Curriculum Priority, Australian Curriculum Version 9.0. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/cross-curriculum-priorities/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-histories-and-cultures?organising-idea=0.

- ACDE (Australian Council of Deans of Education). 2018. ACDE Analysis of 2016 Census Statistics of Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Teachers and Students. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.acde.edu.au/acde-analysis-of-2016-census-statistics-of-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-teachers-and-students/.

- Alford, J., L. van Leent, L. Downes, and A. Woods. 2022. “Critical Literacies in Australia.” In The Handbook of Critical Literacies, edited by J. Z. Pandya, R. A. Mora, J. H. Alford, N. A. Golden, and R. S. De Roock, 125–132. New York: Routlege.

- Anderson, P. J., S. Y. Yip, and Z. M. Diamond. 2022. “Getting Schools Ready for Indigenous Academic Achievement: A Meta-Synthesis of the Issues and Challenges in Australian Schools.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 32 (4): 1152–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2021.2025142.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. 2023. Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Accessed March 2. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards.

- Baynes, R. 2016. “Teachers’ Attitudes to Including Indigenous Knowledges in the Australian Science Curriculum.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 45 (1): 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.29.

- Bedford, A., and V. Walls. 2020. “Teaching As Truth-Telling: A Demythologizing Pedagogy for the Australian Frontier Wars.” The Agora 55 (1): 47–55. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/aeipt.227426.

- Bishop, M., G. Vass, and K. Thomson. 2019. Decolonising Schooling Practices Through Relationality and Reciprocity: Embedding Local Aboriginal Perspectives in the Classroom. Accessed December 27, 2019. 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1704844.

- Booth, S., and B. Allen. 2017. “More Than the Curriculum: Teaching for Reconciliation in Western Australia.” International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education 8 (2): 3123–3130. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2017.0420.

- Britzman, D. 1998. Lost Subjects, Contested Objects: Towards a Psychoanalytic Inquiry of Learning. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Britzman, D. 2000. “Teacher Education in the Confusion of Our Times.” Journal of Teacher Education 51 (3): 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003007.

- Buxton, L. 2017. “Ditching Deficit Thinking: Changing to a Culture of High Expectations.” Issues in Educational Research 27 (2): 198–214. http://www.iier.org.au/iier27/buxton.pdf.

- Carter, J. 2022. “Stories That Matter: Engaging Students for a Complex World Through the English Curriculum.” Curriculum Perspectives 42 (2): 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-022-00174-8.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Comber, B. 2015. “Critical Literacy and Social Justice.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 58 (5): 362–367. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/74883/.

- Council of Australian Governments Education Council. 2019. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Carlton South, Victoria: Education Services Australia.

- Crawford-Garretta, K., R. Damon, D. R. Carbajal, A. Short, K. Simpson, and E. Meyer. 2020. “Teaching Out Loud: Critical Literacy, Intergenerational Professional Development, and Educational Transformation in a Teacher Inquiry Community.” The New Educator 16 (4): 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2020.1785601.

- Denzin, N. K., and M. D. Giardina, Eds. 2015. Qualitative Inquiry, Past, Present and Future: A Critical Reader. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

- Desmarchelier, R. 2020. “Indigenous Knowledges and Science Education: Complexities, Considerations and Praxis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Critical Pedagogies, edited by S. R. Steinberg and B. Down, 642–657. Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing.

- Dowling, C. 2022. “Educating the Heart: A Journey into Teaching First Nations Human Rights in Australia.” In Activating Cultural and Social Change: The Pedagogies of Human Rights, edited by B. Offord, C. Fleay, L. Hartley, Y. Gelaw Woldeyes, and D. Chan, 183–196. New York: Routledge.

- Essop, A. 2017. “Decolonisation Debate Is a Chance to Rethink the Role of Universities.” The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/decolonisation-debate-is-a-chance-to-rethink-the-role-of-universities-63840.

- First Nations National Constitutional Convention and Central Land Council (Australia), issuing body. 2017. Uluru: Statement from the Heart. https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/.

- Frazer, B., and T. Yunkaporta. 2021. “Wik Pedagogies: Adapting Oral Culture Processes for Print-Based Learning Contexts.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 50 (1): 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.24.

- Freebody, P. 2016. Keynote Presentation Literacy: What Works and Why? NSW Institute for Educational Research in Association with UNSW School of Education [Videorecording]. Accessed November 15th, 2016. http://www.etraining.net.au/literacy/keynote-1.

- Freebody, P. 2017. “Critical-Literacy Education: “The Supremely Educational Event.” In Literacies and Language Education. Encyclopaedia of Language and Education, edited by B. Street and S. May, 3rd ed. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02252-9_9.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

- Giroux, H. A. 1993. “Literacy and the Politics of Difference.” In Critical Literacy: Politics, Praxis, and the Postmodern, edited by C. Lankshear and P. L. McLaren, 367–378. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Giroux, H. A. 2011. On Critical Pedagogy. New York, NY: Continuum.

- Gonski, D., T. Arcus, K. Boston, V. Gould, W. Johnson, L. O’Brien, and M. Roberts. 2018. Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Gough, N. 2002. “Blank Spots, Blind Spots, and Methodological Questions in Postgraduate Research.” Invited keynote address to the Postgraduate Research Conference, Australia, October 4th – 6th, 2012.

- Guenther, J., L. I. Rigney, S. Osborne, K. Lowe, N. Moodie, and K. Trimmer. 2023. “The Foundations Required for First Nations Education in Australia.” In Assessing the Evidence in Indigenous Education Research: Postcolonial Studies in Education, edited by N. Moodie, K. Lowe, and R. Dixon. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14306-9_14.

- Harrison, N., C. Tennent, G. Vass, J. Guenther, K. Lowe, and N. Moodie. 2019. “Curriculum and Learning in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education: A Systematic Review.” The Australian Educational Researcher 46 (2): 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00311-9.

- Henderson, D. 2020. “Cross-Curriculum Priorities in the Australian Curriculum: Stirring the Passions and a Work in Progress?” Curriculum Perspectives 40 (2): 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-020-00121-5.

- Hogarth, M. 2022. “An Analysis of Education academics’ Attitudes and Preconceptions About Indigenous Knowledges in Initial Teacher Education.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 51 (2). https://doi.org/10.55146/ajie.v51i2.41.

- Locke, T. 2015. “Paradigms of English.” In Masterclass in English Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning, edited by S. Brindley and B. Marshall, 16–28. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Lowe, K., N. Moodie, and S. Weuffen. 2021. “Refusing Reconciliation in Indigenous Curriculum.” In Curriculum Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing World. Curriculum Studies Worldwide, edited by B. Green, P. Roberts, and M. Brennan. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61667-0_5.

- Luke, A. 2000. “Critical Literacy in Australia: A Matter of Context and Standpoint.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 43 (5): 448–461.

- Luke, A. 2012. “Critical Literacy: Foundational Notes.” Theory into Practice 51 (1): 4–11. ISSN: 0040-5841, 1543-0421. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2012.636324.

- MacNaughton, G. 2005. Doing Foucault in Early Childhood: Applying Post Structural Ideas. New York: Routledge.

- McLaren, P. 2007. Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy. Boston: Pearson Education.

- Merriam, S. B., and E. J. Tisdell. 2015. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Moodie, N., and R. Patrick. 2017. “Settler Grammars and the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45 (5): 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1331202.

- Moodie, N., G. Vass, and K. Lowe. 2021. “The Aboriginal Voices Project: Findings and Reflections.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 49 (1): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1863335.

- Morrison, A., L. I. Rigney, R. Hattam, and A. Diplock. 2019. Toward an Australian Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

- Parkinson, C., and T. Jones. 2019. “Aboriginal people’s Aspirations and the Australian Curriculum: A Critical Analysis.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 18 (1): 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-018-9228-4.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Phillips, S., and C. Archer-Lean. 2019. “Decolonising the Reading of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Writing: Reflection As Transformative Practice.” Higher Education Research and Development 38 (1): 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1539956.

- Salter, P., and J. Maxwell. 2016. “The Inherent Vulnerability of the Australian Curriculum’s Cross-Curriculum Priorities.” Critical Studies in Education 57 (3): 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.1070363.

- Shay, M., and J. Wickes. 2017. “Aboriginal Identity in Education Settings: Privileging Our Stories as a Way of Deconstructing the Past and Re-Imagining the Future.” The Australian Educational Researcher 44 (1): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0232-0.

- Shirodkar, S. 2019. “Bias Against Indigenous Australians: Implicit Association Test Results for Australia.” Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 22 (3–4): 3–34.

- Stone, S. 2020. Australia’s History Is Complex and Confronting, and Needs to Be Known, and Owned, Now. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2020/06/11/1380653/australias-history-is-complex-and-confronting-and-needs-to-be-known-and-owned-now.

- Townsend-Cross, M. 2004. “Indigenous Australian Perspectives in Early Childhood Education.” Australian Journal of Early Childhood 29 (4): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910402900402.

- Townsend-Cross, M. 2018. Difficult Knowledge and Uncomfortable Pedagogies: Student Perceptions and Experiences of Teaching and Learning in Critical Indigenous Australian Studies. University of Technology Sydney. https://www.academia.edu/36810610/Difficult_Knowledge_and_Uncomfortable_Pedagogies_student_perceptions_and_experiences_of_teaching_and_learning_in_Critical_Indigenous_Australian_Studies.

- Urquhart, C. 2013. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE.

- Weuffen, S., and K. Willis. 2023. “The Fallacy of Cultural Inclusion in Mainstream Educational Discourses.” In Inclusion, Equity, Diversity, and Social Justice in Education. Sustainable Development Goals Series, edited by S. Weuffen, J. Burke, M. Plunkett, A. Goriss-Hunter, and S. Emmett. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5008-7_7.

- Wolfe, P. 1999. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London & New York: Cassel.

- Zembylas, M. 2018. “Reinventing Critical Pedagogy As Decolonizing Pedagogy: The Education of Empathy.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, & Cultural Studies 40 (5): 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1570794.