ABSTRACT

A diverse array of families navigate society in current times, yet despite increasing visibility of this diversity within schooling contexts, notions of family as nuclear continue to be (re)produced in these spaces. While this has implications for all children and their families, for gender and sexuality diverse parented families, this state of affairs can create specific challenges. In this article, I draw on conceptualisations of binaries and interpellation to theoretically unpack how family is constructed in schools through ‘mum/dad’ or ‘parent one/parent two’ binaries. The analysis presented provides insights into the normative (re)production of family which has potential to impact on gender and sexuality diverse families and their sense of belonging in schools. In deconstructing ways in which binaries work to (re)produce families in educational contexts, implicit norms are exposed. This provides a critical opening for rethinking ways in which families are constructed through language, discourse, and practice.

Introduction

While family is a pervasive and powerful term central to our culture, it ‘represents a highly unstable and contradictory space’ (Robinson and Jones-Diaz Citation2016, 67). Despite this, the nuclear family comprising biological mum, dad and children, is often represented as the ideal and ‘natural’ formation. This static representation of family fails to recognise that the nuclear family is just one of many forms that have existed throughout history and in modernity (Aries Citation1960; Donzelot Citation1980). Discourses which (re)produce the nuclear family as the only ‘normal’ family structure oppress representations of the diversity of family structures which have always existed. In other words, there is, and always has been, many ways of ‘doing’ family.

Reflective of broader society, school communities are made up of a diverse range of families. However, nuclear constructions of family continue to be highly evident within schools (Carlile and Paechter Citation2018; Mann and Jones Citation2022; Taylor Citation2009). Normative constructions of family are unsurprising given that schools are spaces in which heterosexuality and fixed, binary notions of gender tend to be reinforced as normal (DePalma and Atkinson Citation2010; DePalma and Jennett Citation2010; Ferfolja and Ullman Citation2020; Ullman and Ferfolja Citation2015). These constructions draw on cisheteronormativity, that is, an invisible yet pervasive belief system that centres, naturalises and normalises heterosexuality and notions of rigid male/female genders that align with one’s sex recorded at birth. Choices made within educational spaces in relation to resources, programmes and policies communicate ideas about what family means in these contexts (Cloughessy and Waniganayake Citation2014). As such, schools and educators can inadvertently legitimise, privilege and include particular family representations, and marginalise, silence and render others invisible through the everyday practices of schooling. For gender and sexuality diverse (GSD) parented families, the normalisation of mum-dad nuclear families can lead to experiences of invisibility with regards to their family structure (Jeffries Citation2021).

This is not to suggest that educators take intentional steps to Other GSD parented families or indeed the families of any of the children in their classes. The assumption made in this paper is that teachers are working to be inclusive of all the children in their classes across many dimensions. Teachers work within institutions and the systems-based discourses of homogeneity constrain their practices, just as they may limit the visibility of GSD families. Despite this, and despite how well-intentioned individual teachers may be, GSD-parented families are still left to traverse experiences where their family structures are challenged and where they can seem to be invisible (Jeffries Citation2021). The point of this paper is to shine a light onto the everyday practices of school and schooling that achieve these ends, and not to critique individual teachers, schools or families.

There are numerous ways that schooling and schools may perpetuate nuclear family norms and have difficulties recognising GSD-parented families. For instance, Mother’s Day and Father’s Day are sometimes handled by schools and/or educators in ways that perpetuate cisheteronormativity, such as when children of same-sex parents are not freely able to make a card for each parent, or there are policies in place that do not allow them to purchase more than one gift from school-based stalls (Carlile and Paechter Citation2018; Goldberg Citation2014). Practices such as these can lead to feelings of marginalisation for GSD-parented children and families. Similarly, language choices within school-to-home communication can also render GSD-parented families invisible, including when cisheteronormative phrases like ‘mums and dads’ are used to represent the special adults in children’s lives (Goldberg Citation2014; Gunn and Surtees Citation2011). As well, language and practices can invisibilise or silence the legitimacy of certain families when they are never mentioned or considered as a family type within the everyday language and practices of the school (Cloughessy, Waniganayake, and Blatterer Citation2019). As microcosms of society, schools and schooling can thus be implicated in the (re)production of cisheteronormative discourses of family.

Although there is an acknowledgement in research and many policies of the importance of inclusive family practices (see Mann and Jones Citation2022 for a useful breakdown of policies within the Australian context), data collected as a part of this project show that cisheteronormative (re)productions of family continue to be evident in educational settings. This is not reflective of a lack of desire on the part of educators to create welcoming spaces of belonging for all families; indeed, the literature tells us that teachers want to work in ways that are inclusive and socially just (Keddie and Ollis Citation2019; Niesche and Keddie Citation2016). Rather, I argue that invisibility and silence around GSD families are an effect of discourse. Here, I draw on Foucault’s Citation([1969] 2002 conception of discourse as a ‘way of speaking’ (135), with a view that ‘discourse does ideological work, constitutes society and culture, is situated and historical, and relates to/mediates power’ (Jones Citation2013, 11). By this way of thinking, the discourses circulating within schools are dually influenced by society and culture, while also being generative.

While there is existing research unpacking family discourses in education contexts which draw on theories of heteronormativity (see, for example, Carlile and Paechter Citation2018; Gunn Citation2011; Skattebol and Ferfolja Citation2007), this paper expands on this body of work by employing the theoretical concepts of binaries (Butler Citation2007[1990]; Sedgwick Citation2008 [1990]; Yoshino Citation2000) and interpellation (Butler Citation1997a; Citation1997b; Citation2007[1990]; Citation2011 [1993]) to analyse and deconstruct how normative family discourses are (re)produced in schools through language and practice. I examine the use of mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries to consider how each works as a unified whole to suppress or erase diverse forms of family. I take the position that binary thinking influences the performative (re)production of normative notions of family. Deconstructing ways in which binary discourses influence family normativity in schools is important because despite increasing family diversity, and a growing awareness of the importance of schools as spaces of belonging for all families, normative discourses continue to shape the ways in which families are seen and understood in these contexts. Until these binaries are disrupted, families will continue to be perceived through a discursive lens that can create invisibility around diversity. As a result, my goal in this paper is to unpack normative constructions of family using this binary framing to provide schools, pre-service and in-service educators, and policy makers with new ways to think about the construction of families. Such shifts have the potential to interrupt normative discourses of family and expand experiences of recognition and belonging for GSD-parented families in schooling spaces.

Methodology

Data analysed for this paper were collected as part of a larger research project which examined the enablements and constraints experienced by GSD parents in navigating their children’s school/s. This project was approved by the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 1700000209). Data were collected across seven semi-structured, conversational interviews with 12 GSD parents whose children attended primary schools in a metropolitan city in Australia. The children of these families attended public schools, except for one family, whose children had attended an independent Christian school and had recently shifted to a public high school as the youngest child moved out of primary grades. Interviews ranged from 50 minutes to 3 hours and were conducted using an active interview approach (Holstein and Gubrium Citation1995) which acknowledges the co-constructed nature of interview data. Four interviews were undertaken with couples, two with one parent, and one couple was interviewed separately. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Drawing on a poststructural approach to narrative inquiry (Blumenreich Citation2004; Jeffries Citation2021), data were analysed using dialogic/performance narrative analysis (Riessman Citation2008). As a form of narrative analysis, this approach does not view personal stories as emerging from a deep, innermost part of the self. Rather, narratives are viewed as being both received and composed in multiple contexts, including institutional, historical and discursive (Riessman Citation2008). A queer theoretical lens was brought to the analysis, drawing on numerous tenets of queer theory, including binaries, cisheteronormativity and performativity. In the analysis, I examined ways in which power functions within schools in relation to GSD-parented families. The analysis involved a multi-step process which included transcription, reflective thinking and writing, creation of a narrative table and coding of categories. The project drew on an inclusive view of the term ‘parents’ to include parents, caregivers, and kinship family members as possible interviewees.

In this paper, I draw on narratives from interviews across the dataset relating to the production of family through language and practices. It became evident during analysis that many narratives reflected the construction of family in primary schools as nuclear, that is, families with a mother, father, and children. There were some counter narratives to this construction, such as instances where language such as parent one/parent two were centred. Binaries became a dominant lens for analysis to understand how discourses worked to position families in schools. As many narratives referred to language and naming of parents, Butler’s conception of interpellation was also used as an integral part of the analysis. Before moving on to analyse the data, in what follows, I provide an overview of relevant theoretical aspects of binaries and interpellation underpinning the analysis presented later in this paper.

Power working through binaries

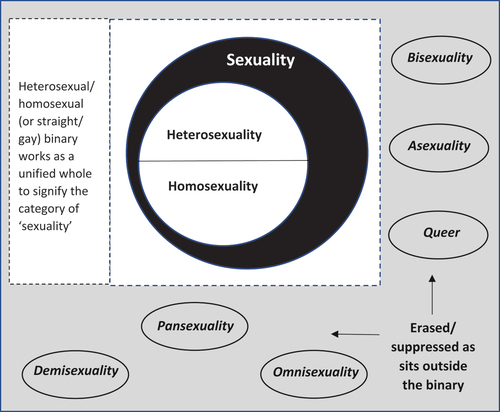

Binaries are a common organiser in Western society which structure thinking and experiences (Seidman Citation1997), and although binaries can appear as natural, they are constructed (Butler Citation2007 [1990]). These dualisms work hierarchically, positioning two categories in opposition to one another, with an understanding of each term occurring in relation to the other (Sedgwick Citation2008 [1990]). In this way, one half of the binary is heroed and the other is positioned as its subordinate Other (Sedgwick Citation2008 [1990]). Binaries function to reward the ‘superior’ category with rights and privileges. For example, as shown in , the heterosexual/homosexual binary positions heterosexuality as normal and natural, and homosexuality is constructed in relation as abnormal, unnatural, and Other. While heterosexuality has been rewarded with rights and privileges over time, homosexuality has been punished and/or disciplined – in essence denied rights. The deconstruction of binary oppositional categories is useful as it can expose and decentre binaries and unequal power relations, potentially creating shifts in hierarchies.

Figure 1. Hierarchised structuring of the heterosexual/homosexual binary. I have drawn on Sedgwick’s (Citation2008 [1990]) work to create a visual representation of this concept.

![Figure 1. Hierarchised structuring of the heterosexual/homosexual binary. I have drawn on Sedgwick’s (Citation2008 [1990]) work to create a visual representation of this concept.](/cms/asset/efc579fc-95e5-498e-ba15-26fe4b8b5b80/rpcs_a_2362421_f0001_b.gif)

Oppositional binaries do further work beyond this hierarchical positioning of the individual categories contained within them. Such dualisms function as a unified whole to erase or suppress other categories which exist outside the binary. Yoshino (Citation2000), for example, argues that the heterosexual/homosexual binary serves to reify sexuality in this dualised form, thereby erasing and suppressing the existence of sexualities outside this binary. While Yoshino focuses solely on the erasure of ‘bisexuality’ in their work (a reflection of discourse at the time), demonstrates that viewing sexuality through a ‘gay/straight’ lens erases a range of sexualities including asexuality, pansexuality, demisexuality, omnisexuality and queer.

Figure 2. The binary working as a unified whole to erase/suppress categories of sexuality. This figure has been created to illustrate and build on Yoshino’s (Citation2000) conceptualisation of the heterosexual/homosexual binary working as a unified whole to erase/suppress sexualities outside of this dualism.

Also, reflecting this idea of the binary working as a unified whole to suppress or erase is Butler’s (Citation2007 [1990]) analysis of the binary system of male/female sexes within medical discourses. Butler explains that intersex bodies can be seen as requiring medical intervention to make them ‘normal’ – in other words, to make them into what society has constructed as natural. Here, the male/female binary acts as a unified whole to erase and suppress intersex bodies which exist outside the normalised male/female binary. A male/female gender binary works in the same way to erase and suppress the many ways of ‘doing’ gender outside this dualism (such as non-binary, genderqueer, demigender, pangender, brotherboy, sistergirl, two-spirit, and so on). Such erasure serves to (re)produce the male/female gender binary, reifying this dualised form as natural and normal. In each of the examples above, power operates by foreclosing the possibility of ways of being and doing outside of the binary.

In this paper, I extend ideas which draw on this concept (of the binary working as a unified whole to suppress and erase that which exists outside the binary) to think through the construction of family within schooling contexts. Narratives collected within the study reflected that schools often rely on binary constructions of family in their day-to-day work, such as mum/dad and parent one/parent two constructions. Drawing on narrative data collected as a part of the larger study to think through these constructions theoretically provides an opportunity to examine ways in which binary discourses work to position families and, in turn, interrupt normative notions of family produced within schooling contexts.

Production of the family through interpellation

This paper also draws on Butler’s (Citation1997a,Citation1997b, Citation2007 [1990]; Citation2011 [1993]) theorisations of interpellation in considering the ways in which families are hailed in schools through language. Language is an important consideration in examining the production of family in schools, particularly as it is bound up with recognition. Butler (Citation2007 [1990]) argues that ‘abstractly considered, language refers to an open system of signs by which intelligibility is insistently created and contested’ (198). What Butler (Citation2007 [1990]) means here is that language is implicated in the process of recognition and intelligibility, and this process is not fixed or static. An example of interpellation is the proclamation common in the lead-up to and at the birth of a new child, such as ‘It’s a boy!’ (Butler Citation1997a, 49). Such utterances interpellate the child into discourse, assigning a gender and producing the child as a particular gendered being (Citation2007 [1993]). This interpellation is reiterative, repetitively producing the subject throughout one’s life.

In theorising about language, Butler (Citation1997a, Citation1997b) draws in part on Althusser’s (Citation2001 [1971]) concept of interpellation which relates to the discursive constitution of the subject through address, that is, through being hailed in accordance with prevailing norms of recognition (Butler Citation1997a). However, whereas Althusser’s theorisation involves a subject who turns and recognises themselves when hailed by an authoritative voice, Butler (Citation1997a) contests the assertion that the subject must accept the call for interpellation to take place. Rather, they claim that a subject does not need to turn when it is hailed or named nor accept the call, in order to be discursively produced as a social subject through the interpellation. The subject may refuse the call, standing in critical relation to it, yet still be constrained by the call. This is because interpellation does not describe reality, rather it attempts to establish reality, producing and reifying the subject in particular ways through reiteration over time (Butler Citation2011 [1993]). This can be seen, for instance, in conservative discourses of family often used during same-sex marriage debates where notions of ‘real’ and ideal families have been reiteratively produced as being headed by a biological mother and a father and same-sex parenting structures as damaging and dangerous to children (Jeffries Citation2021). Despite contestations, same-sex parented families are constrained by these normative interpellations of what constitutes family. Further, the names that a subject is not called are also constitutive (Butler Citation1997a). For instance, a parent who does not use mum/dad labels (such as is common with non-binary or agender parents) may be interpellated as ‘mum’ or ‘dad’ because of normative assumptions, despite not identifying in this way. In this process, they are not called by their name, not recognised, and as such become an impossibility. This is something my own family has experienced regularly, with my partner (parent name: ‘Moddy’) regularly being called ‘dad’. Similarly, whereas there are extensive children’s books with mum/dad characters, there are not books about ‘Moddies’ and so in many ways our family does not exist. As Butler (Citation1997a) states, ‘the possibilities for linguistic life are both inaugurated and foreclosed through the name’ (41).

I now move on to discuss the data in relation to constructions of binaries to represent family within schools and schooling. In this section, I discuss the mum/dad binary, followed by the parent one/parent two binary and, finally, shifting beyond binaries to recognise diverse families.

Construction of families through binaries: Language and practices

Considered through the lens of Butler’s (Citation2007 [1990]) theory of performativity, notions of ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ families are produced through repeated speech and bodily acts. Analysis of narrative data showed that the mum/dad binary was very evident within the primary schooling context, thereby constructing and representing families repetitively through a normative nuclear family lens. This occurred, despite the diversity of families navigating these contexts. Reports of the use of a non-gendered two parent model (parent one/parent two) in schools also occurred in the data. There were limited examples provided by participants of schools engaging families outside of binary constructions, demonstrating that heteronormative and homonormative family discourses were prevalent. Each of these discursive constructions is discussed (below) theoretically by considering the (re)production of family normativity through language and practice. In the analysis, I examine ways in which binaries work to construct families in particular forms resulting in the (re)production of normative discourses of family. Deconstructing how these discourses work to position families in normative ways provides a critical opening to interrupt these binaries and create spaces of greater recognition and belonging for diverse families in schools.

The Mum/Dad binary: producing families as nuclear

Across the data, the positioning of families using a mum/dad binary lens in language and practice was raised by participants. Several stories were shared about the use of mum/dad and mother/father language to interpellate families in primary school contexts, including through forms and permission slips and everyday language. Such language fails to recognise the diversity of families navigating schools. For instance, Mia and Sam recounted that in the first week of Grade One their child (Ava) brought home a folder labelled ‘Mum/Dad Notes’. Finding the folder in Ava’s schoolbag was upsetting for the couple as the label did not reflect their same-sex parented family structure. Mia and Sam shared that this event led them to intervene. They approached the teacher to share about their family and discuss their concerns about the folder. Recognising that it was early in the school year, they explained to the teacher at the meeting that ‘Ava would talk about having two mums and [that] it [was] really important to normalise that experience’, sharing that ‘families come in all shapes and sizes’. When the couple raised the issue of the folder language not representing their family, the teacher responded that she had placed the slash between the words ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’ (i.e., ‘Mum/Dad’) to recognise family diversity, in that, if a child’s parents were separated, the folder would be labelled appropriately no matter which parent the child was staying with on that night. This demonstrates that the teacher was actually cognizant of diverse family types and had taken steps to attempt to be inclusive. However, the change of language that she made still resulted in a situation where the school language was representative of a nuclear family form, albeit a once nuclear but now separated or dually located family. The couple suggested to the teacher that perhaps she could call the folder ‘parents’ folder’ or ‘notes home’ to reflect family diversity, something the teacher appeared to be open to during the discussion.

The narrative told by Mia and Sam about the Mum/Dad Notes folder is representative of an attempt to hail families within a schooling context using a nuclear lens. It is clear from this story that there was an attempt by the teacher to label families in a way that acknowledges family diversity, however the dominance of normative discourses which position all parents as opposite-sexed is evident in the use of mum/dad language. In other words, mum/dad labelling is an effect of discourse. The teacher is not the originator of this language, rather the language represents a performative (re)production of existing nuclear discourses of which the origin point can never be known (Butler Citation1997a). The interpellation misses its mark as, in Mia and Sam’s case, it does not describe the family which it attempts to hail – even if the intent was to be representative of diverse families. Butler (Citation1997a) warns that ‘the performative effort of naming can only attempt to bring its addressee into being: there is always the risk of a certain misrecognition’ [formatting as per original] (95). In this case, Mia and Sam’s family was misrecognised in the folder’s address and normative notions of family as nuclear were (re)produced through its label.

The label on the folder reflects the mum/dad binary working as a unified whole, producing families as nuclear and foreclosing the possibility of other forms of family. In using the nuclear mum/dad binary to interpellate ‘family’, the label on the folder worked to suppress diverse forms of family existing outside of the mum/dad binary. With this in mind, Mia and Sam’s same-sex parented family was erased as an effect of the labelling, rendering their family invisible and unintelligible. Similarly, in narratives shared by several same-sex families regarding forms and permission slips which used mum/dad or mother/father language, the mum/dad binary worked to erase and suppress family diversity. The interpellation of families using the mum/dad binary erases many diverse family forms, including polyamorous parented families, sole-parent families, step/blended families, families with grandparents as caregivers, foster families, families with gender diverse parents (such as non-binary/agender), extended families, and so on.

While the above narrative focuses on interpellation of families through language, the mum/dad binary was also evident in stories about practices within schooling contexts. For instance, one couple shared that, in their child’s first year of school, a ‘big, big extravaganza event’ was organised for Father’s Day, involving ‘days and days’ of preparation and excitement for the children. However, there appeared to be little consideration that some children might not have a dad; rather, it was ‘just assumed that everyone had a dad’. In an attempt to find a solution, the two-mum family decided to bring a male family friend to the Father’s Day event. However, it was a difficult experience for their child, who became uncomfortable and disengaged in a situation where she was surrounded by children celebrating this big event with their dads. The couple shared about the impact on their family:

We were really upset after that … at having been put in that situation … It was the first time I ever felt like she was made to feel different. All of the rest of the time I feel like she’s just one of the crowd and no one really notices anything and no one’s treated her differently. But that was the first time I thought, ‘No, this is really affecting her now’.

In this example, families were viewed through a mum/dad binary lens, with a resulting assumption that every child had a dad. Such an approach reflects an idea that all children have a mum and a dad, overlooking the diversity of family structures and situations evident within schools and contributing to the (re)production of the nuclear family as ‘normal’ and ‘natural’. Practices such as this not only invisibilise same-sex parented families but also a range of family structures that do not fit the binary, including those where parents may not identify with a gendered parenting label (such as is the case with many non-binary parents). Finally, the participant’s comments about their child being ‘made to feel different’ demonstrates that practices which draw on a mum/dad binary view of family can have significant impacts for children of diverse families and reinforces the importance of comprehending families beyond a binary lens.

Assumptions that each child has just one mum is another effect of the mum/dad binary working as a unified whole to represent ‘family’. Same-sex parents Claire and Raeven, for instance, shared a narrative about their young child, Reef, in relation to his teacher asking if his ‘mum’ would be coming to parent/teacher night. While not an unusual question to ask a child, Reef was unable to answer because he did not have just one mum; he had two. For Claire, the teacher’s question was positive and meaningful as she reported that it signalled to her that no one had forewarned the teacher about their family structure and therefore her family was viewed as no big deal. This is interesting, but for this paper what is noteworthy is that this narrative also reflects the interpellation of families through the mum/dad binary, with an assumption that all children have just one mum. Through this lens, the social reality of Claire and Raeven’s family was erased, leaving their child not knowing how to answer a question that positioned his family normatively. This idea of only having one mum was also evident in stories shared about attempts to identify the ‘real’ mum in a two-mum family – through questions about hair colour, who carried the child during pregnancy and even direct questions about who the ‘real’ mother was. These questions draw on the mum/dad binary in ways which reflect Western notions of kinship relating to blood/biology. Moreover, in this line of questioning, a hierarchical binary is created between the ‘biological’ mum and the ‘other’ mum. This is a way in which power reinforces notions of the nuclear through a hierarchical binary, (re)producing the ‘biological’ mum as the real mother and the ‘non-biological’ mother as the subordinate Other – the unreal. As the mum/dad binary positions families as having just one mum, it voids the family as it exists, working to suppress recognition of both mums as ‘real mothers’.

Narratives of gendered practices which drew on the mum/dad binary were also evident within the data. As an example, practices reflecting gendered notions of parenting using a binary lens were also evident in classroom Mother’s Day activities such as nail painting, hand massages, and cupcake-making, as well as Father’s Day activities of paper plane throwing, woodwork, and barbecuing. A request by a school tennis coach for a child to ‘go home and get your dad to hit a ball with you’ reflects an idea that all children have a dad, as well as similar gendered ideas about parenting. Unbeknownst to the coach in this situation, the child had two mums and no dad. While it is not likely that the coach would or maybe even should have knowledge of the family in that detail – that is not the point being made here. It is that in the unknowing state, this coach fell into the essentialised and romanticised notions of nuclear families and gendered roles within those expected families. These gendered ideas are reflective of Butler’s (Citation2007 [1990]) conception of the heterosexual matrix, a cultural frame which produces particular performances of sex, gender, sexual practice, and desire as natural and intelligible, while rendering others as incoherent and unintelligible (208). Through these stereotypically gendered practices, binaries of mum/dad and ‘feminine/masculine’ combine to contribute to the continued production of the heterosexual matrix in schools, (re)producing notions of natural and authentic expressions of ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ and foreclosing the possibility of multiple ways of doing gender.

The mum/dad binary was also (re)produced in gendered ways through conceptualisations of gendered roles in families. For instance, one two-mum family reported that their school introduced ‘Dads’ Coffee Hour’ before the start of the school-day because a weekly mid-morning parent catch-up was attended ‘predominantly by female parents’:

So they decided to hold these Dad’s Coffee Hours before work so if you’re a female parent you can turn up at 10 o’clock to a coffee session and you can meet the community liaison officer who is a parent who works two days a week and has no power in the school, [but] if you’re a male parent you can turn up at 7.30 in the morning and have coffee with the principal and have a direct link straight into the school and have influence that way … but they don’t get that most of the women at the school are working and would probably go to a 7.30 coffee over a 10 o’clock coffee because they can’t make it … there’s no sense of working parents or like no inclusive language whatsoever.

The decision to introduce a gendered parents’ coffee hour not only gave dads a direct link with the Principal who holds the most power in the school, a link that female parents were unable to access, but this setup also overlooked that not all families have dads and that many women also engage in paid work and may not be able to attend the 10 o’clock session. As such, a nuclear family with a stay-at-home mum becomes the expected, the centralised ideal. Such decisions draw on historical (bourgeoise) male/female binary discourses of fathers as workers/earners and mothers as homemakers and has the effect of further perpetuating patriarchal power structures. Further, such practices do not take into account that there are parents who may not identify with the male/female binary, such as those who identify as non-binary, agender and genderqueer, and therefore may not identify as ‘mum’ or ‘dad’. This narrative demonstrates the importance of moving beyond mum/dad and male/female binaries in order to create equitable spaces for all families as well as gender and sexuality diverse families.

An effect of the production of families through a mum/dad binary lens, both in structure and in relation to gendered roles, is that families sitting outside this structure can be viewed through a lens of loss. For instance, Jade shared that her children’s family structure (two mums, no dad) had been conflated several times with children who had lost their fathers. She explained about some of her experiences in talking to teachers about Father’s Day, noting that she requests her children have free art-time during any in-class Father’s Day activities (such as when the class is making cards or Father’s Day craft):

So we’ll try to talk to them about Father’s Day and they’ll say, ‘Yeah we have a kid in the class whose Dad died, we get it’. And we’re like no, you just explained that you don’t get it at all. For our kids, there is no grief around that, there’s nothing missing, there’s no gap. There’s no ‘it’s Father’s Day and I need to cry’. There’s no emotion around it. Give them free art time, they’re good to go.

This lens of loss draws on the mum/dad binary as a unified whole to signify family – as the family that we should all want and aspire to. This reflects notions that an intact family must have a mum and a dad and those without a dad are perceived as ‘missing’ a required component. This narrative shows the importance of viewing families outside of a mum/dad binary lens to ensure all families are viewed as whole.

The generative nature of discourse is important to consider when thinking about the mum/dad binary in schools, particularly as children may view families through this binary lens. Several parents spoke of the importance of ensuring that family diversity was talked about and represented within classrooms so that their children feel a sense of belonging and recognition. Within the data, there were several narratives which showed, for instance, that children with same-sex parents may sometimes find themselves having to field questions from other children about why their family does not fit dominant social norms. For instance, one parent shared that when they moved to a new school where there were no other same-sex parents, their child Harper was asked several times by classmates about her family structure, with some apparent confusion about her having two mums and no dad. Harper did not know how to answer these complex questions, and so she responded by telling her classmates that she had a brother and sister living in another state, as well as a dad who had died. In other words, she made up family members to make her family structure fit the normative notions of family (re)produced by her peers. Schools are in a unique position to assist young people to understand that there are a range of diverse families in society. By engaging with language and practices that interrupt the (re)production of normative discourses, there is an opportunity for young people to rethink these discursive norms and help to create spaces of belonging and recognition for children of GSD-parented families, as well as other diverse families. In what follows, I shift beyond the mum/dad binary to consider attempts at greater recognition within schooling contexts drawing on a parent one/parent two binary.

One plus one equals two: producing families through a non-gendered parent one/parent two binary

While many of the narratives shared by participants reflected mum/dad binary constructions of family within schooling contexts, there were also some examples of a non-gendered two parent approach. For instance, Timothy offered a narrative in which there was a shift away from mum/dad to a non-gendered production of family as two-parented. An important background to this story is that Timothy gave birth to his children, at the time identifying as cisgender female. This meant that their family reflected a cisheteronormative mum/dad structure for the early part of his children’s lives. Timothy later transitioned to male when two of his children were attending primary school. He explained that when he transitioned gender, his children ‘not only [had] a parent who was transgender but from the point of view of other people progressively more and more they [had] two dads’. As often occurs in primary school classes, a list containing parent contact details was shared amongst families. Timothy explained that this list had been created by a parent in the class and had previously utilised mum/dad language. However, the language had since shifted to using parent one/parent two. Timothy described this shift as ‘very nice’ and ‘very affirming’, suggesting that in moving away from mum/dad binary language to parent one/parent two (in which families are interpellated as having two parents of non-specific gender), there was a sense of visibility and intelligibility in this form of labelling as it was inclusive of Timothy’s family structure. In contrast to using the mum/dad binary, when hailing parents as parent one/parent two, same-sex parented families and other two-parented forms of family were no longer erased.

The change from mum/dad to parent one/parent two labelling reflects an attempt to move recognition of family structure beyond a heteronormative framing. Hailing families in this way, however, meant the structure continued in binary form and consequently, while there appears to be some gain here, this representation of families is constraining as it only recognises a two-parented structure. Such a change demonstrates how interruptions to heteronormativity can manifest in shifts towards homonormativity (Neary Citation2017). Duggan (Citation2003) describes homonormativity as ‘a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormativity assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them’ (179), privileging GSD people whose lives reflect dominant cultural, racial, class, gender, and relationship norms. Although the interpellation of ‘family’ through the parent one/parent two binary recognises two-parent same-sex families and other two-parent family forms, this binary works as a unified whole to erase a range of structures that do not fit a two-parent model. These include sole-parent families, step and blended forms, those with grandparents as caregivers, families where people beyond the nucleus are recognised as having important caregiving roles, polyamorous parented families, and other diverse family constellations. Thus, the parent one/parent two binary creates a gateway for heteronormativity and homonormativity to function.

Constituting families as two-parented in schooling practices can create inequities for families who do not reflect this structure. Emily and Alexa, for instance, talked of their experiences with systems that construct families as two-parented, specifically with regard to contact points. The same-sex couple parented Elijah and Finn together in a step-parenting situation where Emily shared custody of the children with her ex-husband and the children lived between the two houses. In reflecting on the ways in which schooling systems had positioned their family (which had more than two parenting figures), they shared that at the children’s primary and later, secondary schools, only two people were able to be listed in data systems as contact points. They explained that there were:

The production of families within systems as two-parented is based on Western, nuclear discourses of family. Such structures overlook families that value more than two persons as parent or carers in a child’s life. In this case, family members beyond those who are listed as ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ parents within data management systems are not privy to information that will assist them in supporting the child, unless it is passed on by one of the two listed parents. While some schools may find work arounds to systems such as this, Alexa and Emily’s story demonstrates how systems can create challenges for families when they are viewed through a parent one/parent two lens. Further, the couple’s experience is reflective of research (see, for instance, Carlile and Paechter Citation2018) that demonstrates schools can be inclusive of GSD families comprising just two parents living in one household with their children (homonormative), to the detriment of those who do not fit this model.

Also, important to consider with regard to the parent one/parent two model (such as occurs within primary parent/secondary parent labelling), is that a hierarchy of parent figures is created. This is reflective of Sedgwick’s (Citation2018 [1990]) work on binaries in which she argues that two oppositional categories are positioned unequally in a hierarchy, with one category being rewarded with greater rights and privileges. The experience shared by Alexa and Emily clearly shows their understanding that the primary parent is rewarded by the system with provision of information that the secondary parent does not receive. However, this system also has the potential to exacerbate family labour already unequally undertaken by women in heteronormative family structures. In this case, for instance, Emily is listed as primary parent and her ex-husband as secondary, leaving Emily with significant labour in relation to managing information and the children’s school lives.

Alexa and Emily also reported that this foundation belief of all children having two parents meant that the school only allowed two parents to attend parent-teacher interviews (and offered just one interview for each family), thus erasing and suppressing families that existed beyond a two-parent structure. As there were no options except for two people to attend the one interview, Alexa was unable to attend and was therefore denied the opportunity to be a part of critical discussions and left to be ‘unknowing’ of issues related to the children. Such structures overlook families that value more than two persons as parents or carers in a child’s life, which can be the case in step and blended families, as well as families of a range of cultural backgrounds. The construction of a family through a two-parent lens likely draws on the assumption that a biologically connected mother and father are interested in the child – not three adults or more – and further foregrounds Western biological discourses of family. This idea fails to recognise there are many ways of ‘doing’ family. Alexa and Emily noted that once Elijah started attending secondary school, they were offered multiple meetings so that all parents and caregivers could connect with teachers about their children. This, they reported, provided an example of moving beyond the two-parented notion of family.

When schools shift outside the bounds of thinking about families and parenting through such binaries, some of the burden of recognition is removed from parents. Alexa commented on the systemic constraints they had experienced, offering her thoughts about what she would prefer to see happen in schools so that the burden of recognition is not placed on the shoulders of those to whom recognition is denied:

Here, Alexa reflects on many of the ways that the construction of families as two-parented can create constraints for diverse families. While it is worth noting that the experiences of step-parents who come into already established binary parenting structures may differ in some ways to families in which multiple co-parents come together in a myriad of other ways, Alexa’s words demonstrate the importance of systems and practices catering to the reality of family diversity. In other words, if schools can step outside of mum/dad and parent one/parent two binary constructions of family and consider that families are much more diverse than these binaries represent, there may be opportunities to recognise and meet the needs of a wider range of families.

Beyond binaries: recognising diverse families

While a good deal of the narratives found within the data framed families as being nuclear, and parents as biologically opposite sexed, there were some instances where parents narrated experiences that resisted these framings. In fact, only one set of parents, Willow and Angie, spoke about schools being proactive in relation to approaching families about naming practices in an attempt to recognise diversity. As such, there was little evidence of language practices that sit outside binary constructions of family. Willow shared about her experience as a same-sex parent:

I have been asked … what does Lucas call us at school you know by the teacher or by you know the [head] teacher and that sort of thing so they’re very yeah they wanna get it right … I do think it’s quite funny because a couple of the kids now call me Mama Willow because that’s what Lucas calls me so that’s actually what a lot of the kids call me.

In this example, the couple were not interpellated through the mum/dad binary, thereby creating visibility around their family structure. It is not uncommon for GSD-parented families to take up naming practices which operate outside of the mum/dad binary. As such, approaching families about their naming practices reflects recognition of diverse family forms. Willow noted that some of Lucas’ classmates also used inclusive language normalised within the school, calling her Mama Willow. The interruption to the production of families as nuclear enabled new language norms to be established. This reflects Butler’s (Citation2005) assertion that norms change, that ‘the normative horizon within which I see the other, or, indeed, within which the other sees and listens and knows and recognises is … subject to a critical opening’ (24). For Butler, this shift occurs through a desire to recognise the other, a desire which compels a willingness to stand in critical relation to norms when such norms are troubled. Within these critical openings, it is possible to step beyond mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries, opening possibilities for recognition of GSD-parented families in schooling contexts.

While there were limited examples in the data of practices in which schools and educators moved beyond binary constructions of family, this paper is focused on how educators can and do achieve this inclusive approach. Usually, the narratives shared included details of relatively simple practices. As examples, educators approaching parents about their opinions before Mother’s Day or Father’s Day, using language such as ‘parents and caregivers’ in letters and, as noted above, providing multiple opportunities for parents and caregivers to attend parent teacher interviews. In sharing their stories, some participants provided other ideas of how binaries could be interrupted, such as celebrating Family Day (instead of Mother’s and Father’s Day), ensuring forms use more suitable language, and teachers using language and resources in the classroom that reflects family diversity. Most importantly, it was clear that in interrupting the binaries that can position families as mum/dad or parent one/parent two, it is imperative that schools recognise diverse families as heterogeneous with differing needs and preferences.

Conclusions

Even though schools are made up of diverse families, the data in this study show that families continue to be constructed in cisheteronormative ways through language and practice in education contexts. That these discourses continue to operate, despite increasing family diversity, demonstrate their endurance and the importance of deconstructing and interrupting normative family discourses. This normativity impacts a range of families in schooling contexts because it means that not all families are seen, understood, or valued, equally. Morley and Leyton (Citation2023) say it is important to ‘notice, challenge, and, whenever possible work to dismantle heteronormativity’ in education’ (185). While their focus is on higher education, this call to action is equally important in primary school and early education settings, particularly given the silences around gender and sexuality diversity in these spaces (Ullman and Ferfolja Citation2015).

This paper has drawn on theoretical concepts taken from Butler (Citation2007 [1990]), Sedgwick (Citation2008 [1990]) and Yoshino (Citation2000), to unpack the ways in which binaries work through language and practices within school contexts to produce only particular forms of family as recognisable. There are many ways of doing family, and given that interpellation forms part of subjection, deconstructing the use of mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries and how they work as a unified whole to represent family has been important in considering the ways in which binaries work performatively to (re)produce ideas about family within schooling contexts. In drawing on the mum/dad binary, families in schools are produced as having a mum and a dad, and as comprising of just one mum and one dad. Further, the mum/dad binary can be (re)produced in gendered ways, constructing mothers as ‘feminine’ and fathers as ‘masculine’. Through the mum/dad binary, families who do not reflect this family structure can be viewed through a lens of loss. Productions of family through the mum/dad binary fail to recognise the diversity of families that exist in Australian society and schools. Although the non-gendered parent one/parent two binary label challenges traditional nuclear constructions of family, this two-parented view continues to place boundaries around what is considered to be a recognisable and intelligible form of family. Like the mum/dad binary, the parent one/parent two binary can also work as a unified whole to erase and/or suppress family diversity within schooling contexts. Further, the parent one/parent two binary creates a hierarchy of parent figures.

In engaging parents and families, it is important that schools recognise the diversity of families that may operate within their bounds. When families are produced through binary lenses of mum/dad and parent one/parent two, families are produced in particular, normative ways that may impact on recognition and a sense of belonging for a wide range of families, including GSD-parented families. Within existing literature, practices in schools such as issuing school forms with mother/father fields, activities such as family trees, and Mother’s Day and Father’s Day celebrations can be problematic for GSD-parented families as they are not recognised because of their family diversity (Cloughessy and Waniganayake Citation2014; Goldberg Citation2014; Kosciw and Diaz Citation2008). The analysis in this paper foregrounds that normative discourses of family are performatively (re)produced through the reiteration of binaries in schools, even though the reality of doing family is much more diverse.

Schools and teachers are uniquely positioned to interrupt cisheteronormativities and binaries in education spaces, and there are many ways to ensure that diverse families are recognised and valued. For instance, schools can ensure that forms, communications with the school community, systems, and policies are inclusive of diverse family structures, genders, and sexualities. Similarly, teachers can ensure that learning activities, resources (such as books, posters, and other learning materials), verbal/written language, and communication with families are reflective of a wide range of family types and ways of ‘doing’ family. Events that are organised around a particular gender or family relationship can be rethought and reconstructed in new ways that are considerate of family diversity. Furthermore, moving beyond assumptions about family structures, roles, and naming practices also provides an essential foundation for assisting schools to become more inclusive of diverse families. Each of these approaches provides a beginning point to ensure that young people in diverse families feel included and that they belong, as well supports an awareness of family diversity for all young people.

There is no one-size-fits-all map to creating socially-just, inclusive schooling spaces for GSD-parented families. Communication with GSD parents and caregivers to learn about each family and their needs is, therefore, an essential foundation of this work. Further, some approaches to inclusion can create a space in which invisibility makes way for hypervisibility, where families might shift from a sense of being unseen to feeling like they stand out, and uncomfortably so (see Skattebol and Ferfolja Citation2007 for a useful example). For these reasons, perhaps one of the most important strategies for schools and teachers is to engage in professional learning about gender and sexuality diversity, family diversity, intersectionality, and anti-bias approaches, to ensure that the daily work of schools is underpinned by critical knowledge and understanding of the impacts of normativities on minoritised groups. Such learning also removes some of the labour that GSD parents are often required to undertake to help create safer school spaces for their families.

Although it is possible to shift beyond binary thinking, normative discourses are pervasive, and mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries can continue to attempt to hail families within schools who do not fit this structure. This can create challenges for schools and families. Understanding the ways in which mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries work to discursively produce ‘family’ provides a critical opening for schools to consider how they might interrupt these binaries to allow for greater recognition of family diversity as they engage with parents and families within their contexts. Given that mum/dad and parent one/parent two binaries erase and suppress diverse forms of family, thinking beyond these binaries to consider families as they exist in their diverse forms is important to creating spaces of welcome and belonging for all families.

Acknowledgements

I pay my respects to the First Nations peoples on whose lands I have conducted this research, the Turrbal and Yugara peoples. I pay my respects to their Elders, past, present, and emerging, as well as their lores, customs, and creation spirits. I acknowledge the Turrbal and Yugara peoples as the first educators, researchers, and storytellers of this place.

This article draws on work from my doctoral thesis. I would like to acknowledge my supervisors Dr Lyndal O’Gorman and Professor Annette Woods for their vital support and feedback. I also acknowledge the support I have received from Associate Professor Lisa van Leent and Dr Naomi Barnes in talking through various aspects of the paper in its development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Althusser, L., and F. Jameson. [1971] 2001. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: (Notes Towards an Investigation).” In Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, edited by B. Brewster, 85–126. New York: Monthly Review Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qgh9v.9.

- Aries, P. 1960. Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life. London, UK: Pimlico.

- Blumenreich, M. 2004. “Avoiding the Pitfalls of ‘Conventional’ Narrative Research: Using Poststructural Theory to Guide the Creation of Narratives of Children with HIV.” Qualitative Research 4 (1): 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104041108.

- Butler, J. [1990] 2007. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Butler, J. [1993] 2011. Bodies That Matter. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1997a. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1997b. The Psychic Life of Power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Butler, J. 2005. Giving an Account of Oneself. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Carlile, A., and C. Paechter. 2018. LGBTQI Parented Families and Schools: Visibility Representation and Pride. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cloughessy, K., and M. Waniganayake. 2014. “Early Childhood Educators Working with Children Who Have Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Parents: What Does the Literature Tell Us?” Early Child Development and Care 184 (8): 1267–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.862529.

- Cloughessy, K., M. Waniganayake, and H. Blatterer. 2019. “The Good and the Bad: Lesbian Parents’ Experiences of Australian Early Childhood Settings and Their Suggestions for Working Effectively with Families.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 33 (3): 446–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1607786.

- DePalma, R., and E. Atkinson. 2010. “The Nature of Institutional Heteronormativity in Primary Schools and Practice-Based Responses.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1669–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.018.

- DePalma, R., and M. Jennett. 2010. “Homophobia, Transphobia and Culture: Deconstructing Heteronormativity in English Primary Schools.” Intercultural Education 21 (1): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980903491858.

- Donzelot, J. R. 1980. The Policing of Families: Welfare versus the State. Translated by R. Hurley. London, UK: Hutchinson.

- Duggan, L. 2003. The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Ferfolja, T., and J. Ullman. 2020. Gender and Sexuality Diversity in a Culture of Limitation: Student and Teacher Experiences in Schools. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. [1969] 2002. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. Abingdon. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge Classics.

- Goldberg, A. E. 2014. “Lesbian, Gay, and Heterosexual Adoptive Parents Experiences in Preschool Environments.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29 (4): 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.07.008.

- Gunn, A. C. 2011. “Even if You Say it Three Ways, it Still Doesn’t Mean it’s True: The Pervasiveness of Heteronormativity in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 9 (3): 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X11398567.

- Gunn, A. C., and N. Surtees. 2011. “Matching Parents’ Efforts: How Teachers Can Resist Heteronormativity in Early Education Settings.” Early Childhood Folio 15 (1): 27–31. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0154.

- Holstein, J. A., and J. F. Gubrium. 1995. The Active Interview. Vol. 37. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Jeffries, M. 2021. Experiences of gender and sexuality diverse parents in primary schools. PhD thesis. Queensland University of Technology, https://eprints.qut.edu.au/208076/.

- Jones, T. 2013. Understanding Education Policy: The ‘Four Education Orientations’ Framework. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Keddie, A., and D. Ollis. 2019. “Teaching for Gender Justice: Free to Be Me?” The Australian Educational Researcher 46 (3): 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00301-x.

- Kosciw, J. G., and E. M. Diaz. 2008. Involved, Invisible, Ignored: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Parents and Their Children in Our Nation’s K-12 Schools. New York, NY: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). http://www.glsen.org/learn/research/national/report-iii.

- Mann, T., and T. Jones. 2022. Including LGBTQ Parented Families in Schools: Research to Inform Policy and Practice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Morley, L., and D. Leyton. 2023. Queering Higher Education: Troubling Norms in the Global Knowledge Economy. Routledge.

- Neary, A. 2017. “Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual teachers’ Ambivalent Relations with Parents and Students While Entering into a Civil Partnership.” Irish Educational Studies 36 (1): 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2017.1289702.

- Niesche, R., and A. Keddie. 2016. Leadership, Ethics and Schooling for Social Justice. Oxon, New York: Routledge.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Robinson, K. H., and C. Jones-Diaz. 2016. Diversity and Difference in Childhood: Issues for Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. London, UK: Open University Press.

- Sedgwick, E. K. [1990] 2008. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Seidman, S. 1997. Difference Troubles: Queering Social Theory and Sexual Politics. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Skattebol, J., and T. Ferfolja. 2007. “Voices from an Enclave: Lesbian Mothers’ Experiences of Child Care.” Australian Journal of Early Childhood 32 (1): 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910703200103.

- Taylor, Y. 2009. Lesbian and Gay Parenting: Securing Social and Educational Capital. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ullman, J., and T. Ferfolja. 2015. “Bureaucratic Constructions of Sexual Diversity: ‘Sensitive’, ‘Controversial’ and Silencing.” Teaching Education 26 (2): 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2014.959487.

- Yoshino, K. 2000. “The Epistemic Contract of Bisexual Erasure.” Stanford Law Review 52 (2): 353–461. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229482.