ABSTRACT

With critical pedagogy (CP), teachers and students are empowered to disrupt the dominant ideological structures that tend to dehumanise people and impose oppressive historical consciousness upon them as historical subjects. Inspired by CP, over the last three decades critical language pedagogies have been conceptualised to promote social justice and counter privileged ideologies. This study examined university teachers’ pedagogical engagement with students’ local multilingual resources and epistemologies in the Remedial English classes at Pakistani universities. The study made use of theoretical insights such as coloniality, raciolinguistic perspectives and critical scholarship on multilingualism. Findings suggest that some teachers maintained the linguistic and epistemic hierarchy that favoured English, American/British accent, Anglo-western literature and culture, while other created multilingual and epistemic spaces where students’ local languages, nativized English varieties, culture and values could find a place. Furthermore, the Remedial English course perpetuated a gap between word and world by ignoring students’ contemporary concerns, such as discursive (values, culture) as well as material (unemployment, corruption, human rights, environmental degradation, etc.) factors. Some teachers’ use of bottom-up agency to counter foreign literature and a monoglossic model of instruction suggests how some teachers with a critical pedagogical attitude can empower their students to reclaim their historical and social roots.

Introduction

As English remains an official language and a medium of instruction in many postcolonial countries (see Kubota Citation2018; Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022), it maintains linguistic and epistemic hierarchies often shaped by national, colonial, and neoliberal ideologies. Consequently, these postcolonial societies remain largely ideologically interpellated spaces. Critical language pedagogy is discussed by several language scholars as a pedagogy with ‘attitude’ (Pennycook Citation2001), a way of doing and teaching (Canagarajah Citation2005), a discourse of liberation and hope (Akbari Citation2008), and as teaching for social justice (Crookes Citation2022) as it helps undo ‘ideological interpellation’ (Althusser Citation1971) and liberates teachers and learners from affective and social scars experienced in classrooms and outside as a result of colonial history and neocolonial educational discourses and language ideologies. As Pennycook (Citation2021, 44) explains, critical language pedagogy (CLP) in the contemporary era should promote language learning for social change, support students’ culture and voices, promote critical language awareness, and impart critical perspectives on multilingualism and decolonisation. In other words, critical language pedagogy in the present time should challenge coloniality by encouraging teachers and learners to promote their local languages and epistemologies in academic settings, which requires them to develop their linguistic and epistemological sensibilities.

Taking these perspectives into account, the present study explores the language ideologies, practices and epistemic struggles of university English language teachers at Pakistani universities. As a postcolonial country, Pakistan is highly diverse in terms of its ethnic, linguistic, and religious composition. English is the official language of the country. Many view it as a passport to social and economic mobility, a symbol of intelligence, and a means to achieve high social standing (Channa Citation2017; Rahman Citation2005). Currently, it is used as a medium of instruction in higher education institutions as mandated by Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission (HEC) (Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022). Scholars have, however, criticised the English-led monoglossic model of instruction and advocated additive bilingualism/multilingualism (Mahboob Citation2020; Mustafa Citation2011) and translanguaging (Syed Citation2022) to comply with the heteroglossic classroom realities. Also, they have expressed concerns over mono-epistemic classes characterised by colonial curriculum content (Manan and Tul-Kubra Citation2022; Shah Citation2021). Against this backdrop, the present study explored how teachers engage with English language students and the course contents at Pakistani universities by using critical language pedagogy as a framework characterised by coloniality (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007) and raciolinguistic perspective (Flores and Rosa Citation2015) as well as growing critical scholarship on multilingualism (Kubota Citation2016; Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022; May Citation2014). These theoretical lenses help us gain insights into pedagogy from the perspectives of compliance (Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022), social justice (Crookes Citation2022), and decolonial performativity (Pennycook Citation2000). This study intended to achieve two goals:

It sought to understand English language teachers’ language ideologies and practices when teaching students from diverse linguistic backgrounds in the classroom.

It attempted to understand the epistemic struggles that students engaged in while studying English at the university level and the way teachers engaged with those struggles.

In what follows, we first provide an overview of critical pedagogy (CP) and its use in English Language teaching (ELT), followed by theoretical insights. Next, we discuss our methodology, including context, participant information, interview process, and analysis. The study concludes by suggesting ways in which monolingual and monocultural ELT classes can counter dominant language ideologies and epistemes.

Critical Pedagogy (CP), language classes and ELT

Critical pedagogy (CP) as we understand it today is originally credited to Paulo Freire. According to Kincheloe (Citation2008), all work in critical pedagogy after him must reference his work. Freire (Citation2005, 44) characterised critical pedagogy as the humanistic and historical task of oppressed people – liberating themselves and their oppressors. In his view, education has long suffered from ‘narrative sickness’, and it has been used for propaganda, manipulation, and ideological interests (68). Teachers often achieve this by using ‘method’ to silence learners in the classroom. This led him to advocate co-intentional education. As he argued:

teachers and students (leadership and people) co-intent on reality, are both subjects, not only in the tasks of unveiling that reality, and thereby coming to know it critically, but the task of re-creating knowledge … through reflection and action … as permanent re-creators (Freire Citation2005, 69).

The teacher-student relationship in this model is based on conscientization, which refers to identifying social, political, and economic contradictions and taking action to counter them (Freire Citation2005, 109). Consequently, teachers and students are required to engage in a praxis – reflection and action. In addition, this allows teachers and students to co-create knowledge, liberating humans from oppressive historical consciousness. There is no unified way of doing critical pedagogy, so it is conceptualised and practiced differently. However, all scholars agree that it must achieve its end goals: social justice, democracy, and humanisation. Historically, critical pedagogy traces its roots to the Frankfurt School, founded in 1923 by neo-Marxist thinkers – Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Erich Fromm, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Leo Lowenthal, and Jürgen Habermas. The Marxist intellectual tradition runs deep in Paulo Freire’s early pedagogical work. As a result, Marxist pedagogies, such as CP, analyse group dominance and subordination, class and culture, power distribution, control of knowledge and language, and how dominant groups exert social control through schools (Apple Citation1979; Giroux Citation1983; Kincheloe Citation2008; Pennycook Citation2021).

This growing popularity of Marxist-based critical pedagogical approaches prompted a burgeoning body of scholarship in applied linguistics to examine how language and language learning are related to power, subordination, and social control (Canagarajah Citation2005; Crookes Citation2022). This resulted from the critical space the field of applied linguistics/TESOL/ELT called for in the late 1970s led by the ‘social turn’. Consequently, the use of CP was seen as a critical approach to literacy and pedagogy that exposed underlying power imbalances, social injustices, and inequalities, and how it could be used to empower teachers and learners (Akbari Citation2008; Crookes Citation2022; Pennycook Citation2021). Akbari (Citation2008) defines critical language pedagogy (CLP henceforth) as a discourse of liberation and hope. In such discourses, teachers are expected to transform students’ lives by acknowledging local culture, L1 as a resource, real-world concerns, and awareness of marginalised groups. According to Crookes (Citation2022), critical language pedagogy (CLP) is a value-laden project that favours social justice. CLP can be implemented to whatever extent, and by whatever means, by teachers to address the real-world conflicts to reclaim social justice.

Arguably, critical language pedagogy takes on different forms to engage with power imbalances and inequalities. This is why some scholars suggest critical language educators must determine the most effective way to implement a project of possibility for language learners (Norton and Toohey Citation2004). Taking into account Canagarajah’s (Citation2005) and Norton and Toohey’s (Citation2004) stance that critical language pedagogy should be contextually relevant to grasp power in pedagogy, we envision CP as a situated critical project in the South to investigate linguistic and epistemic hegemonies as well as the real-world concerns. In postcolonial societies like Pakistan, colonialism is deeply rooted in educational spaces promoting English and its discourses underpinned by Anglo-Western norms (Manan and Tul-Kubra Citation2022; Shah and Pathan Citation2016). As Sucerquia (Citation2020) argues, critical language teachers must bear in mind that language education has been a site of colonisation. Given these historical influences, Thiong’o (Citation2012, 82) suggests a structural change: the rise of departments dedicated to world literature and balancing national and global approaches, methods, and experiences. Pennycook (Citation2000) describes such action as decolonial performativity which helps teachers move from being passive technicians (Kumaravadivelu Citation2012b) to critical pedagogues. Thus, CP in language classes allows teachers and students to be critically reflexive and resist local and global ideologies operating in classrooms.

Theoretical underpinnings

Our use of CP in this paper is characterised by both the Southern and Northern theoretical stances – coloniality (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007) and a raciolinguistic perspective (Flores and Rosa Citation2015; Rosa and Flores Citation2017) – to unravel deeply rooted colonial relations in English language teaching practices in Pakistan that contribute to the formation of racialised subjects. Coloniality is defined as long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism and continue to colonise, not only the practices of the colonised, but also their imaginations (Quijano Citation2007). These colonial relations in linguistic practices and imaginations can be explained from a raciolinguistic perspective that examines how language and race have been co-naturalised across various nation-states and colonial contexts over time (Rosa and Flores Citation2017). Consequently, these raciolinguistic scholars tend to underscore the colonial distinction between whiteness and non-whiteness in language ideologies and step towards deconstructing the discourses of appropriateness, standardised linguistic practices as sets of objective linguistic forms often perceived as being appropriate for academic settings (Flores and Rosa Citation2015). Conversely, they point out the formation of racialised language ideologies that marginalise the language practices of subaltern populations (see also Flores Citation2013) and engage them in appropriate linguistic practices. As viewed from a raciolinguistic perspective, ‘white gaze’ associated with speaking and listening subjects reinforces language deficit ideologies where idealised/standardised (Anglo-American) varieties are considered ‘the standard norm’ and linguistic practices of racialised speaking and listening subjects are viewed as ‘deviations’ (Flores and Rosa Citation2015; Sultana Citation2023; Syed Citation2024). A growing number of scholars have recently attempted to trace coloniality and raciolinguistic ideologies in ELT teaching, curriculum, and policy discourses globally including Pakistan (Kubota Citation2023; Manan et al. Citation2023; Sah Citation2024; Shah and Syed Citationforthcoming; Syed Citation2024). In his recent study, Syed, (Citation2024 analysed how educational policy discourses in Pakistan tend to reinforce the notion of deficient speakers in English MOI policy and language proficiency tests in Pakistan by adhering to the monoglossic language ideologies.

In addition, we also draw insights from the critical scholarship on multilingualism (Kubota Citation2016; Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022; May Citation2014) which holds how multilingual speakers follow distinct trajectories. People who are multilingual have experienced a variety of linguistic situations in their lives, resulting in a rich and dynamic linguistic trajectory. Multilingual learners are affected by these trajectories as they learn and use diverse languages in class (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2020; Douglas Fir Group Citation2016). Moreover, multilingual learners have their own epistemic experiences that they bring to the class. However, scholars have cautioned about the celebratory view of multilingualism (see e.g., McNamara Citation2011) by suggesting that it tends to support the atomistic view (Cenoz Citation2013) which regards languages, language varieties, and language use as autonomous entities with clear linguistic boundaries. Instead, they propose a holistic approach that takes into account multilingual speakers’ hybrid, fluid and dynamic use of linguistic and semiotic repertoire (García and Sylvan Citation2011; Kubota Citation2016; Syed Citation2022). Moreover, these scholars also argue how a celebratory view of multilingualism obscures the bigger issues of our times (e.g., neoliberalism and its effects) (Kubota Citation2016) and further link multilingualism with capitalist political economy (Block Citation2017; Simpson and O’Regan Citation2018). Consequently, language scholars working within a poststructuralist and political economy perspective view multilingualism critically as sustaining structural inequalities not only through the commodification of languages (Block Citation2017; Kubota Citation2016; Simpson and O’Regan Citation2018) but also multilingualism itself (Duchêne Citation2009).

In this paper, we consider multilingualism as a critical response to monoglossic instruction and language deficit ideologies (Sah Citation2024; Syed Citation2024) permeating English Remedial Classes in Pakistan by taking into account students’ whole linguistic as well as epistemic repertoires characterised by their diverse ethno-linguistic identities. As such, we view ‘language’ and ‘episteme’ as co-occurring categories in classroom setting. Taken together, these theoretical lenses provide insights to understand pedagogy in terms of compliance (Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022), decolonial performativity (Manan et al. Citation2023; Pennycook Citation2000) and social justice (Crookes Citation2022) in the light of colonial historical processes and raciolinguistic ideologies.

The present study

Context

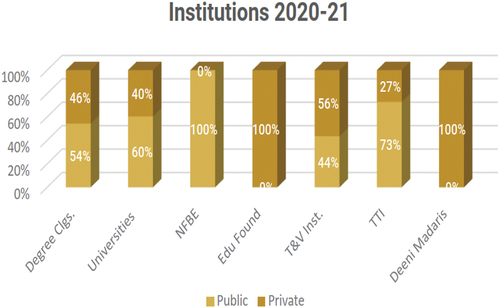

This qualitative study was conducted in Sindh, Pakistan’s second largest province. There are 202 universities and degree-awarding institutions in Pakistan, which include both public and private institutions. Out of these universities, 122 universities (60%) lie in the public domain (see ). Public universities require all students to take a ‘Remedial English’ course in their first and second years. The course aims to improve the students’ English language proficiency (both productive and receptive). Some universities, however, prefer to call the course ‘Functional English’ rather than ‘Remedial English’. With this change in title, their course outlines and choice of teaching resources vary. For example, the universities in Sindh that follow Remedial English (the focus of our study), often use prescribed coursebooks such as ‘English for undergraduates’ (Howe, Kirkpatrick, and Kirpatric Citation2014), ‘Oxford Practice Grammar’ (Eastwood Citation1992) and the British Council’s ‘English for Academic Purposes’. However, the universities that prefer to teach Functional English use course outlines adopted from the national curriculum mandated by HEC, Pakistan. These universities allow teachers to develop their own teaching resources.

Figure 1. Universities and degree awarding institutions in Pakistan (Pakistan Education Statistics 2021, 15).

It is worth mentioning that immediately after Pakistan’s independence in 1947, foreign publishers and organisations such as Oxford University Press (OUP) and the British Council established offices in the country. OUP opened a branch in Pakistan in 1952, with its head office in Karachi (the capital city of Sindh province) it produces books, not only for general audiences, but also for school and university students (Raza Citation2013). In addition, the British Council as a professional organisation dedicated to promoting English as a global tradeable commodity entered the Pakistani linguistic and cultural market in 1948 as a trusted partner with the goal of offering opportunities to the country’s young entrepreneurs, policy makers, and academics. Besides conducting high-stakes tests such as IELTS, the organisation also works closely with the Pakistani government on English medium education. As an example, the British Council launched the ‘Punjab Education and English Language Initiative’ (PEELI) project in 2013 in collaboration with the Punjab government in order to enhance teacher effectiveness by assessing teachers’ English language proficiency and to decide whether the government of Pakistan would be able to successfully implement its English as medium of instruction policy in schools. The council is criticised for its monolingual bias in its treatment of English language proficiency, teaching of English, testing, and the development of its courses (see Syed Citation2024). However, the British Council holds a strong position in the country in terms of providing teaching materials, assessing proficiency tests, and offering training to English teachers. The university courses that teachers in our study engage are produced by the OUP and the British Council.

Data and the participants

We collected data from five public universities in Sindh province that offer a Remedial English course to students in Social Sciences, Humanities, Natural Sciences, and Information Technology. Two teachers from each university participated in semi-structured interviews (see ). Semi-structured interviews allow participants space for extended conversations in which they can interpret, in their own words, their opinions, beliefs and understandings about the world around them (Silverman Citation2017) as well as providing researchers with deeper understanding of the participants’ perspective on the issue being studied (Bryman Citation2016). The choice of semi-structured interviews was made for two reasons in our study: a) we wanted to learn how English language teachers engage with students and course content in linguistically and epistemologically diverse classrooms at Pakistani universities, b) considering our intellectual commitment within critical language pedagogy (CLP) from a decolonial and raciolinguistic perspective, our interaction with the teachers was valuable for eliciting their critical insights. Scholars have noted how researchers’ reflexivity and positionality play an important role in qualitative research in shaping knowledge (Braun and Clark Citation2019; Knott et al. Citation2022). The interview questions were developed following literature on critical language pedagogy, examining teachers’ multilingual practices, linguistic beliefs, classroom language use, views on course content, and engagement with the content and students based on students’ linguistic and epistemic diversity.

Table 1. Participants’ biographical information.

The study followed ethical protocols, including participants’ written consent before data collection. In the consent form, participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity related to their identities. Our study has thus used pseudonyms to refer to participant responses and kept their universities’ names confidential. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, and each interview lasted 20–30 minutes. Participants were required to have at least three years of classroom experience as we believe such teachers can reflect more comprehensively on their practices.

Interviews were recorded. We conducted interviews using our multilingual repertoire (English, Sindh, and Urdu) for two reasons. First, it enabled the participants to code-switch to their local languages when desired. The second reason was that, as part of critical language pedagogy, our research should not be influenced by monoglossic ideologies centred around English as the privileged language.

Data analysis

Data was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA). A reflexive TA emphasises the importance of the researcher’s subjectivity as an analytic resource, and their reflexive engagement with theory, data and interpretation. The analysis followed the six stages of reflexive TA conceptualised by Braun and Clark (Citation2019). These include 1) data familiarisation and writing notes 2) systematic data coding 3) generating initial themes from coded and collected data 4) developing and reviewing themes 5) refining, defining and naming themes and 6) writing the report. Based on our contextual positionalities as Pakistani university teachers and researchers, we developed themes shaped by theoretical stances such as coloniality, raciolinguistic ideologies and social justice perspectives that characterised our critical pedagogical work. Braun and Clark (Citation2019) indicate that themes don’t emerge passively. In our research, reflexive TA helped us develop themes relevant to our objectives, like ‘teachers as postcolonial passive technicians’ and ‘teachers as decolonial performative agents’. These themes were combined into one heading, followed by ‘students’ unattended real-world concerns’.

Findings

Teachers as postcolonial passive technicians or decolonial performative agents?

University English classes in Pakistan are dominated by monoglossic language ideologies influenced by top-down language policy discourse. This policy discourse is, according to Syed (Citation2022), based on a deficit perspective in which students are viewed as struggling learners in need of support in overcoming their linguistic deficiencies, and their language practices are seen as deviations from what is deemed ‘correct’ or ‘standard’ language. Consequently, most teachers in Pakistan practice what Manan et al. (Citation2022) call a ‘pedagogy of compliance and compromise’, explaining how teachers’ language choices are affected by both official policy and external factors. The following excerpts in our data illustrate how some teachers were influenced by language regimes that affirm the hegemony of English in their classes while being complicit in the monoglossic model of language instruction.

I prefer to use English language in classes for communication and teaching purpose. It is because as an English language teacher, it is better to communicate in English so that students can also learn and communicate in class. It is important for students to develop interest in learning and speaking English as a language. (Saif)

I use English most of the time I am in class. The obvious reason is to practice targeted language in order to improve the language proficiency among students. (Hira)

There is already a growing concern that our students lack English proficiency required for the job market. Therefore, I give them more exposure to English in my classes. (Sajjad)

Teachers’ preference for English in classes is shaped by the institutional policy as highlighted by the participants e.g., ‘since English is the medium of instruction, I mostly use English language’ (Rahman), ‘it is a requirement of my job’ (Sawera), as well as social factors, such as success in the job market (Rabia), getting good salaries (Saleem) and attracting employers as potential candidates (Shahid). These factors – institutional monoglossic policies and social impetus – taken together shape the monolingual teaching approach as practiced by teachers in Pakistan (see e.g., Syed Citation2024). This monolingual teaching practice and the dominance of English in the field of ELT/TESOL can be understood in the context of several discourses, including linguistic imperialism, globalisation, neoliberalism, and historical processes that underpin it (see Holborow Citation1999; O’Regan Citation2021; Phillipson Citation1992). O’Regan (Citation2021, 7) describes English as a ‘free rider’ on global capital, which means English and capital go hand in hand in a neoliberal empire. In postcolonial societies such as Pakistan, these global discourses in addition to the colonial history of the country account for the spread of English and enforcement of monoglossic teaching approach. As a result, teachers are influenced by these discourses that shape their pedagogy and characterise their teaching beliefs involving ELT. Viewed from a raciolinguistic perspective, it reflects the construction of raciolinguistic subject positions among teachers, as colonial relations continue to influence the social order in the postcolonial era by framing racialised subjects’ (i.e., learners’) language practices as inadequate to navigate in the global economy (Rosa and Flores Citation2017). These discourses, however, can be better illustrated by the following excerpts which explain how teachers view English in terms of a symbolic capital (Bourdieu Citation1991) embodied through its idealisation of standard accent and American/British variety of English as taught in recommended English textbooks and practiced in classes.

We usually use the textbook produced by international publisher, and that follows standard variety of English. We follow language textbooks written by Oxford University Press and British Council. (Hira)

I try my best to speak in Standard English and also teach my students rules of standard variety. I think our local varieties are not acceptable in institutions or in job market. (Faiz)

As a teacher, I try to use American English, but students’ language practices are mostly influenced by local accents. The reason to use American English is to maintain the standard of English accent. (Saif)

I prefer American English which is a bit easier than British English specifically in terms of speaking. To teach ELT classes in Pakistan, American English should be preferred. (Rabia)

In these excerpts, English teachers express a high regard for standard English, specifically American English. They appear to maintain the normative monolingual order where the concept of the ‘native speaker’ still holds sway. The tendency towards American English and accent results from American political, cultural and economic influence in Pakistan. Because of this, teachers idealise Standard English, specifically American English. It is also evident in how the American English language programs over the past two decades have invaded social and educational spaces in Pakistan over the past two decades, administered by the Regional English Language Office (RELO), which is part of the US Embassy in Pakistan. The programs not only provide training to teachers, but also offer on-site as well as online English language courses to Pakistani learners (see, e.g., Shah, Pardesi, and Memon Citation2024). These programs also run at the universities, and teachers actively participate in training programs and take part in pedagogical activities. These developments could be partly responsible for idealising standard accents, specifically American English, while the colonial history of the country as an ex-British colony may account for the prestige accorded to the standard variety of British English. According to Flores and Rosa (Citation2015), the notions of ‘standard language’, ‘academic language’ and ‘discourses of appropriateness’ in which they are embedded need to be conceptualised as racialised ideological perceptions rather than objective linguistic categories. Teachers’ own racialised subjectivities influenced by colonial histories and discourses in English classes appear to reproduce and reinforce raciolinguistic ideologies in English classes as illustrated in the above excerpts.

Pennycook (Citation1998) argues that some of the key ideologies of English language teaching are derived from colonial cultural constructions that can be identified through colonial notions of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’. Rosa and Flores (Citation2017) also argue that raciolinguistic ideologies create racialised Others as a result of the colonial linguistic practices and discourses. Accordingly, teachers’ use of Standard English reinforces the Self/Other binary where teachers’ racialised speaking/listening subject positions are constituted through their engagement with idealised linguistic practices of whiteness (e.g., discourses of standard language). Consequently, the linguistic practices of the subaltern populations, English learners in a Pakistani context in this case, are interpreted as deviant (Flores Citation2013; Flores and Rosa Citation2015). Teachers’ constitution of the racialised Other as a subject position – nonnative speakers of English – stands in contradiction with growing debates in World Englishes (Kachru Citation1985) and English as a Lingua Franca (Jenkins Citation2009; O’Regan Citation2015). Arguably, these beliefs, as reflected in teachers’ responses, are not asocial, but rather are a direct result of societal strains and impetus from private organisations that constrain teachers to stick to the so-called standard varieties and accents as shown in the following excerpt.

Society’s imagining of the ‘standard’ and ‘Englishman’ and the pressure from the private corporations to use English in Pakistan can be explained what Rojo and Del Percio (Citation2020) call ‘neoliberal governmentality’. However, in the context of Pakistan it needs to be combined with the coloniality (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007) that is deeply entrenched in the social fabric of society. In recent times the neoliberal global order has concentrated on all aspects of human life, including society, corporations, civil society, and individuals. The colonial-neoliberal nexus accounts for how people are interpellated as postcolonial subjects lacking in epistemic struggles to counter the social hegemonies, including the hegemony of English. Collective colonial consciousness of people and the demands of the corporate organisations in a way contribute to maintaining the linguistic hierarchies in Pakistan in addition to the top-down policy measures (Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022). Within the linguistic hierarchy and monolingual ideological biases, English is seen in relation to Englishman reflecting the fact that ‘Englishman’ has not left the indigenous worlds yet. The following excerpts further illustrate how this phenomenon is deeply entrenched in academic spaces in Pakistan,

I try to sound like native English speaker, because I know as a teacher my English accent is highly appreciated by students and other people in the university. (Saif)

My colleagues at the departments where I teach Remedial English course often expect me to speak good English and speak like Americans or Britishers. They say, we [not having English as a major] can also speak English, but the difference that you should reflect in your language is your refined and polished accent. So of course, I do practice my accent and learn correct pronunciation most of the times. (Rabia)

These institutional and societal pressures and aspirations are an index of monolingual fallacies (Phillipson Citation1992), and teachers appear to be passive postcolonial technicians with a primary function of merely transmitting and channelling the flow of information from one end of the educational spectrum (i.e., experts) to the other (i.e., learners), without altering the content of the information significantly (Kumaravadivelu Citation2012a, 8). Due to these monolingual biases, the idealisation of standard English, and monolingual teaching approaches, these teachers pay little attention to the paradigmatic shift that is characterised by the ‘Multilingual Turn’ (May Citation2014), translanguaging pedagogy (Garcia and Wei Citation2014), pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2020) and how racialised subject positions are constituted through ELT (Rosa and Flores Citation2017). As a result, critical language pedagogy for such teachers was a far-fetched dream as further shown through the following excerpts.

I give students the natural environment for learning English. I believe that foreign language cannot be taught out of environment. So, I show them English movies. I encourage them to read English native writers. I tell them to read newspapers in English. This will help them improve their English. (Faiz)

I teach English through communicative language teaching method where I encourage my students to use only English in different academic, professional and social situations. I help them with correct grammar and suitable words and phrases for these situations. (Hira)

The excerpts reveal how English language teachers adhere to dominant pedagogical norms that place a heavy emphasis on grammatical accuracy and practice language (English) in a native-like environment that reinforces the native speaker fallacy. The idealisation of Eurocentric methods in ELT and native-like environments results from the reification of the white listening subject resulting in deficit language ideologies as well as exclusion of the students’ multilingual repertoire from classroom settings (Rosa and Flores Citation2017; Sah Citation2024). Contrary to the colonial conformity and pedagogy of compliance as shown in the above excerpts, our data also show references to the dissenting voices that created a space for celebration of local multilingualism and epistemic diversity at the university while countering colonial and raciolinguistic subject positions as formed in the English language classes. This multilingual space was used effectively by teachers in their classes and was referred to as celebratory multilingualism (Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022). According to one respondent,

I know the background of my students. They have struggled to reach the university. I can’t force them to speak only in English. I allow them to use their local languages instead of relying fully on English. I just want their participation in my classes, because of language I cannot judge their intelligence. I can’t taunt them for using their native languages. I myself switch to local languages, Urdu and Sindhi to make my students understand the content. (Saleem)

Some teachers resisted traditional linguistic hierarchies in Pakistan that privilege English in education by using linguistic diversity as a resource to support heteroglossic classroom realities. This runs contrary to the monolingual teaching approach that reinforces monolingual fallacies and biases due to institutional policies and societal expectations. This enables teachers to create multilingual/translingual spaces in the classrooms that utilise students’ multilingual repertoire as a resource for meaning making and thinking beyond guilty multilingualism (Cummins et al. Citation2010; Manan, Channa, and Haidar Citation2022) or what Syed (Citation2022) calls ‘guilty translingualism’. Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2020) consider such an approach to be a step towards pedagogical translanguaging which considers students’ multiple languages not just as bounded entities, but also as a means of drawing on their full linguistic repertoire. As a result, some of the teachers we interviewed explicitly stated the importance of using local languages in classes: ‘I love my language’ (Fouzia), ‘language barriers must be avoided’ (Hira), ‘we use Urdu and other local languages in addition to English as a lingua franca’ (Saif). Teachers appeared to practice critical language pedagogy by empowering their students in classrooms by supporting languages and involving them in linguistic decisions in this process. This is illustrated in the following excerpt:

Teachers’ consideration for their students’ diverse linguistic choices reflects their critical and decolonial reflexivity, which Kubota (Citation2023) considers essential to transforming societies. According to language scholars, decolonisation requires teachers to play an important role as reflective scholars (Phyak and De Costa Citation2021) and postcolonial performative agents (Pennycook Citation2000) capable of challenging the hegemonic imposition of English by demonstrating critical language awareness. Teachers viewed students’ multilingual resources as vital since they embody ‘local taste and culture’ (Rahman), ‘rootedness’ (Saleem), and ‘comfort’ (Sawera). Our data further reveals teachers’ dissenting voices in their comments on standard and local varieties and course content, as shown in the following excerpts. These dissenting voices point to the teachers’ practice of critical language pedagogy in classes at Pakistani universities.

My class has freedom to practice whatever variety they develop naturally in real environment. I do not overtly correct students’ pronunciation of words until their pronunciation deviate to the extent that it alters meaning of the word or makes it incomprehensible. (Saleem)

I prefer to speak Pakistani accent of English and encourage my students to do the same because at first, they should be able to speak and gain confidence. I take language use to be more important than the standards. (Hira)

Content mostly refers to English world. It is mostly western civilisation. We teach literature and culture which does not belong to us. Our own literature, cultural values and legacy are kept in the storeroom of false national spirit. I am worried our youth particularly students are trapped between foreign culture and false national imagery. Their regional literature, history and wisdom are neglected. (Shahid)

When I see anything biased related to gender, religion or race in textbook content, I make sure to have an open discussion and introduce other point of view as well. I make sure that my students add their voices to the discussion and their opinions are very much appreciated. (Faiza)

Teachers’ contestation of standard English and/or accent and teaching of foreign cultures and construction of national imagery that excludes regional literature in textbooks all point to the fact that classes were conflicting sites of meaning where teachers were not at the mercy of power (e.g., institutional policies). Language classes, according to Canagarajah (Citation1999), are relatively autonomous places where power is negotiated in order to find alternative arrangements. Within the classroom, teachers and students are able to question, negotiate, and resist power on a micro level. The teachers’ agency and resistance in this case is evident in their efforts to counter epistemic alienation taking place through propagation of foreign culture and construction of false national imagery as well as linguistic ideologies that underpin the idealisation of the so-called ‘native’. In Pakistan, the export of foreign culture in educational spaces is under criticism by several scholars (see, for example, Rahman Citation2005). However, teachers seem to be aware of these hegemonic agenda at local and global levels and do not overlook the ideological temptations in Pakistani context. By combining moral sensibility and social awareness, they are able to resist the colonial tendencies manifested in English teaching that strip the students of their multilingual repertoire and local funds of knowledge (Canagarajah Citation1999; Maldonado-Torres Citation2007). The following section discusses how teachers respond to students’ real-world problems as faced by the students in the present-day Pakistan.

Perpetuating a gap between the word and the world: students’ unattended real-world concerns in language classes

Critical language pedagogy refers to the teaching of a language for social justice (Crookes Citation2022). It is intrinsically political with a particular emphasis on the inclusion of marginalised groups. As such, it provides a ‘discourse of hope’ while connecting classroom pedagogy to real-world concerns (Akbari Citation2008). In Pakistan, however, the teaching of English in Remedial English classes lacks such hope since textbooks embody content that teachers suggest is anaesthetised to be neutral on social, religious, and political grounds. Gray (Citation2001) used an acronym PARSNIP, which stands for politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, -isms, and pornography, for the controversial topics (which are mainly the real-world issues and to be primarily discussed in language classrooms). These real-world controversial topics are, however, excluded from classroom discourse, limiting English language classrooms to neutral subjects such as travel, shopping, and food. As illustrated by the following excerpts in our data, teachers expressed how their teaching was restricted in terms of content that prohibited topics related to religion and politics in English language classrooms.

We don’t have freedom of speech. We’ve serious threats from political parties if we speak on social issues, religion and political corruption. Sectarianism is spreading in institutions, nationalism is growing. Totally biased. Some critical teachers at university level discuss these sensitive issues but with sweetest gestures. (Sajjad)

As a teacher, I am often very careful about talking about real issues that our students face. For example, it is always very difficult to speak in the favour of minorities in classes. As a teacher, you are judged if you support a narrative that supports minorities. It is because students come from diverse backgrounds. Some of them are very conversative. (Shahid)

The above excerpts identify a number of issues prevalent in Pakistani society, including sectarianism, nationalism, minority issues and threats from the political parties. According to Ayres (Citation2009) and Khan (Citation2022), the country has been confronted with several ethno-nationalist movements since its inception. Religious, ethnic, and political groups within the country are often at odds with each other. Accordingly, students in Pakistan experience different kind of problems, including for example, injustice and discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, or faith in academia as well as in society. These issues, however, are not covered in the course materials and the teaching discourse. There are some teachers who deem political, cultural, and religious topics to be of great importance for their students, yet they find it difficult to discuss these subjects in the classroom. As a result, they provide students with the opportunity to discuss these issues outside of the classroom. This was highlighted by some of the interviewees, e.g., ‘ … it is difficult to discuss these topics inside the class. But some students are in our circle, I ask them to discuss such sensitive issues in private’ (Saleem). And some participants showed how they converted these debates into take-home tasks so as to avoid conflict in the classroom. For example, one participant remarked,

I assign such crucial topics as students’ assignments, role-plays and project-based presentations to address students’ real-life concerns. (Faiza)

Despite the participants’ views that the textbooks recommended for Remedial English classes provided insufficient content in terms of real-life concerns, some of the teachers still came up with their own strategies for making the teaching-learning process interesting and contextually relevant. This can be seen in the following excerpts:

The textbooks are mostly theoretical and have nothing to do with the practical lives of the students. The students lose the interest when the content is not applicable to the life. In this case, I take help from the other resources to make things interesting.

These real-life issues are missing in our textbooks, and as a teacher, I feel teachers must play their role in finding a way to make connections between what is written in the textbooks and what really exists in reality.

Yes! learning lessons from the mistakes of other nations give us idea not to repeat those mistakes in our time. I had been teaching fiction topics to my students in Remedial English classes in 2022, and we used to discuss 19th century status and gender problems through writings of Jane Austen.

This excerpt illustrates how students’ material, social, and economic realities were rarely addressed in remedial English classes. Pakistan is experiencing a rise in youth unemployment, corruption, economic deprivation, injustice in the academic and social spheres, and an environmental crisis. According to teachers, these issues are not formally integrated into course content. As a result, most teachers continue to teach the recommended content. Learning critical literacy may help learners become familiar with the real world in this context. As Edelsky and Johnson (Citation2004) note, critical literacy is not only about examining the text but, more specifically about learners’ ‘real-life realities’ and raising voices against social injustice by understanding the role of language and power. Sadly, the situation is opposite in English classrooms at Pakistani universities. We asked ‘How do students engage themselves to discuss their real-life issues and concerns in classes? Are they allowed to add their voice to teaching materials selected for them to learn English?’. According to one participant, students’ voices were generally unheard, for example: ‘Most often, they are silenced and unheard’ (Shahid). It is the teacher’s responsibility to make space for students to raise concerns and issues in such a scenario. Accordingly, an English classroom in Pakistani universities represents what Freire (Citation2005) calls a ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’, which must liberate learners from dehumanising pedagogical practices. Edge (Citation2013) points out that critical language pedagogy is determined by values such as ‘liberty’, ‘community’ and ‘equality’ that an English language teacher should incorporate while teaching in an English language classroom. These values are of core importance for creating democracy in classroom (Crookes Citation2022). Moreover, some critical subjects such as tolerance, awareness of mental health and career counselling are found to be missing from English classroom discourse. See, for example, the following excerpt.

There is dire need to discuss career counselling, political awareness, mental health, and everyday life problems with students. Unfortunately, these important areas are never the topic of discussion at university level. For mental health awareness, Pakistan lags way behind in understanding the importance of mental health and its effects on a person’s life, for most people it is not a thing that exists (Faiz)

Teachers characterised class spaces as lacking in what students may need in their life and are facing, such as mental well-being, career counselling and political awareness. Several scholars have emphasised the importance of considering well-being in language classes as a result of the affective turn in ELT (see for example, Sulis et al. Citation2023) These are real-life concerns for both the teacher and the taught and must be discussed inside the classroom, whether it is linguistic discourses related to power and politics (Canagarajah Citation1993), social and religious debates (Crookes Citation2022) or a learner’s own culture (Akbari Citation2008). All of these concerns must be addressed in order for students to develop their own real-life imaginations.

Concluding remarks

Our study investigated teachers’ engagement with students’ multilingual and epistemic repertoires in public sector universities in Pakistan using a critical language pedagogical framework. Findings suggest that teachers’ responses were marked by both a pedagogy of compliance and a pedagogy of hope, as evidenced by how they reinforced officially mandated language ideologies and course contents, and also by how they resisted them. Some teachers maintained the linguistic and epistemic hierarchy that favoured English, an American/British accent, and Anglo-Western literature and culture, while others created multilingual and epistemic spaces where students’ local languages, nativized English varieties, culture and values could find a place. We believe that critical language pedagogy as a project to foster social justice (Crookes Citation2022) and discourse of hope (Akbari Citation2008) can provide teachers with opportunities to challenge not only officially mandated discourses that reinforce local and global ideological structures but also to negotiate diverse identities and connect word with world as emphasised in the Freirean tradition. Our study considered only interview data. As a result, the study’s findings cannot be generalised due to its methodological limitations. Considering this, we suggest a more nuanced characterisation of critical language pedagogy (CLP) in ELT classes through critical ethnography. This would enable us to gain a better understanding of colonial and racial power relations, and how students and teachers negotiate their local epistemic realities. Teachers’ auto-ethnographic narratives can also provide insights into how they confront linguistic and epistemological inequalities that contribute to social and economic imbalances. Another consideration in this line of research can be the analysis of policy documents.

The world currently faces serious problems of inequality, social injustice, discrimination, unemployment, corruption, and political instability. The role of an English teacher therefore should not be viewed as one of a passive technician, but rather as a social change agent. Teachers have a responsibility to denaturalise concepts and conceptual fields (Kumaravadivelu Citation2016) imposed by raciolinguistic structures that encourage linguistic hierarchies centred on English. Canagarajah (Citation2024) rightly argues that, rather than focusing solely on grammatical or discourse norms, language teaching should emphasise the importance of educating students to become aware of the diverse semiotic resources that mediate grammars, ideologies that frame their use within various contexts, and strategies to renegotiate their footing to ensure more inclusive communication. As he argues, our courses should prepare students for the changing repertoire they will face in global communication. The student must be prepared to be a lifelong learner in the manner of language socialisation. As part of critical language pedagogy, teachers must exploit their agency to make the most of indigenous authentic resources from different regions of the country encompassing different languages and cultures (Syed Citation2024). In this way, teachers can engage students in conversations about indigenous local epistemological traditions as well as creatively use English with their multilingual repertoires to discuss a wide range of topics and genres (Syed Citation2022). In addition, several scholars suggest that teachers should engage in political activism beyond classroom language activism to promote linguistic, economic, and political justice (Alim Citation2010; Phyak Citation2021). Incorporating these critical stances into language pedagogies can enable teachers to empower students to understand, reflect, and address issues that marginalise and alienate them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akbari, R. 2008. “Transforming Lives: Introducing Critical Pedagogy into ELT Classrooms.” ELT journal 62 (3): 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn025.

- Alim, H. 2010. “Critical Language Awareness.” In Sociolinguistics and Language Education, edited by N. Hornberger and S. McKay, 205–231. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847692849-010.

- Althusser, L. 1971. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation).” https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm.

- Apple, M. W. 1979. Ideology and Curriculum. 4th ed. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Ayres, A. 2009. Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Block, D. 2017. “Political Economy in Applied Linguistics Research.” Language Teaching 50 (1): 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444816000288.

- Bori, P. 2018. Language Textbooks in the Era of Neoliberalism. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Polity.

- Braun, V., and V. Clark. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford university press.

- Canagarajah, S. 1993. “Critical Ethnography of a Sri Lankan Classroom: Ambiguities in Student Opposition to Reproduction Through ESOL.” TESOL Quarterly 27 (4): 601–626. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587398.

- Canagarajah, S. 1999. Resisting Linguistic Imperialism in English Teaching. London: Oxford University Press.

- Canagarajah, S. 2005. “Critical Pedagogy in L2 Learning and Teaching.” In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Research, edited by S. E. Hinkel, 931–949. New York: Mahwah NJ Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Canagarajah, S. 2024. “Diversifying ‘English’ at the Decolonial Turn.” TESOL Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3306.

- Cenoz, J. 2013. ‘’Defining multilingualism.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33:3–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719051300007X.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2020. “Teaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging.” World Englishes 39 (2): 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12462.

- Channa, L. A. 2017. “English in Pakistani Public Education: Past, Present, and Future.” Language Problems and Language Planning 41 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.41.1.01cha.

- Crookes, G. V. 2022. “Critical Language Pedagogy.” Language Teaching 55 (1): 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444820000609.

- Cummins, J., M. Early, L. Leoni, and S. Stille. 2010. “It Really Comes Down to the Teachers, I think’: Pedagogies of Choice in Multilingual Classrooms.” In Identity Texts: The Collaborative Creation of Power in Multilingual Schools, edited by J. Cummins and M. Early, 153–164. London: Institute of Education Press.

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. “A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (S1): 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12301.

- Duchêne, A. 2009. “Marketing, Management and Performance: Multilingualism As a Commodity in a Tourism Call Center.” Language Policy 8 (1): 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-008-9115-6.

- Eastwood, J. 1992. Oxford Practice Grammar with Answers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edelsky, C., and K. Johnson. 2004. “Critical Whole Language Practice in Time and Place.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: An International Journal 1 (3): 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427595cils0103_1.

- Edge, J. 2013. “Build it and They Will Come: Realizing Values in ESOL Teacher Education.” In Second Language Teacher Education: International Perspectives, edited by D. J. Tedick, 181–197. New York: Routledge.

- Flores, N. 2013. “Silencing the Subaltern: Nation-State/colonial Governmentality and Bilingual Education in the United States.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 10 (4): 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2013.846210.

- Flores, N., and J. Rosa. 2015. “Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education.” Harvard Educational Review 85 (2): 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149.

- Freire, P. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London/New York: Continuum.

- García, O., and C. E. Sylvan. 2011. “Pedagogies and Practices in Multilingual Classrooms: Singularities in Pluralities.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01208.x.

- Garcia, O., and L. Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. England: Springer.

- Giroux, H. 1983. “Ideology and Agency in the Process of Schooling.” Journal of Education 165 (1): 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748316500104.

- Gray, J. 2001. “The Global Coursebook in English Language Teaching.” In Globalization and Language Teaching, edited by D. Block and D. Cameron, 151–167. London: Routledge.

- Holborow, M. 1999. The Politics of English: A Marxist View of Language. London: SAGE.

- Howe, D. H., T. A. Kirkpatrick, and K. L. Kirpatric. 2014. English for Undergraduates. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Jenkins, J. 2009. “English as a Lingua Franca: Interpretations and Attitudes.” World Englishes 28 (2): 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2009.01582.x.

- Kachru, B. B. 1985. The Alchemy of English: The Spread, Functions and Models of Non-Native Englishes. Oxford: Pergamon.

- Khan, R. 2022. “Between Independence and Autonomy: The Changing Landscape of Ethno-Nationalist Movements in Pakistan.” Nationalities Papers 50 (4): 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.65.

- Kincheloe, J. L. 2008. Critical Pedagogy Primer. Vol. 1. New York: Peter Lang.

- Knott, E., A. H. Rao, K. Summers, and C. Teeger. 2022. “Interviews in the Social Sciences.” Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2 (73): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6.

- Kubota, R. 2016. “The Multi/Plural Turn, Postcolonial Theory, and Neoliberal Multiculturalism: Complicities and Implications for Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics 37 (4): 474–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu045.

- Kubota, R. 2018. “Unpacking Research and Practice in World Englishes and Second Language Acquisition.” World Englishes 37 (1): 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12305.

- Kubota, R. 2023. “Linking Research to Transforming the Real World: Critical Language Studies for the Next 20 Years.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 20 (1): 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2022.2159826.

- Kumaravadivelu, B. 2012a. “Individual Identity, Cultural Globalization, and Teaching English As an International Language.” In Principles and Practices for Teaching English As an International Language, edited by L. Alsagoff, S. L. McKay, G. Hu, and W. A. Renandya, 9–27. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kumaravadivelu, B. 2012b. Language Teacher Education for a Global Society. New York: Routledge.

- Kumaravedivelu. 2016. “The Decolonial Option in English Teaching: Can the Subaltern Act?” TESOL Quarterly 50 (1): 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.202.

- Mahboob, A. 2020. “Has English Medium Instruction Failed in Pakistan?” In Functional Variations in English, edited by R. A. Giri, A. Sharma, and J. D’Angelo, 261–276. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. 2007. “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 240–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548.

- Manan, S. A. 2021. “‘English Is Like a Credit card’: The Workings of Neoliberal Governmentality in English Learning in Pakistan.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45 (4): 987–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1931251.

- Manan, S. A., L. A. Channa, and S. Haidar. 2022. “Celebratory or Guilty Multilingualism? English Medium Instruction Challenges, Pedagogical Choices, and Teacher Agency in Pakistan.” Teaching in Higher Education 27 (4): 530–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2045932.

- Manan, S. A., M. A. Tajik, A. Hajar, and M. Amin. 2023. “From Colonial Celebration to Postcolonial Performativity: ‘Guilty multilingualism’ and ‘Performative agency’ in the English Medium Instruction (EMI) Context.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2023.2242989.

- Manan, S. A., and K. Tul-Kubra. 2022. “Reclaiming the Indigenous Knowledge (S): English Curriculum Through ‘Decoloniality’ Lens.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 17 (1): 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2022.2085731.

- May, S. 2014. “Disciplinary Divides, Knowledge Construction, and the Multilingual Turn.” In The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and Bilingual Education, edited by S. May, 7–31. New York: Routledge.

- McNamara, T. 2011. “Multilingualism in Education: A Poststructuralist Critique.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01205.x.

- Mustafa, Z. 2011. The Tyranny of Language in Education: The Problem and Its Solution. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Norton, B., and K. Toohey, Eds. 2004. Critical Pedagogies and Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Regan, J. P. 2015. “On Anti-Intellectualism, Cultism, and One-Sided Thinking. O’Regan Replies.” Applied Linguistics 36 (1): 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu049.

- O’Regan, J. P. 2021. Global English and Political Economy. London: Routledge.

- Pennycook, A. 1998. English and the Discourses of Colonialism. London, England: Routledge.

- Pennycook, A. 2000. “English, Politics, Ideology: From Colonial Celebration to Postcolonial Performativity.” In Ideology, Politics, and Language Policies: Focus on English, edited by T. Ricento, 107–119. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/impact.6.09pen.

- Pennycook, A. 2001. Critical Applied Linguistics: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge.

- Pennycook, A. 2021. Critical Applied Linguistics: A Critical Re-Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Phillipson, R. 1992. Linguistic Imperialism. London, England: Oxford University Press.

- Phyak, P. 2021. “Epistemicide, Deficit Language Ideology, and (de)coloniality in Language Education Policy.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2021 (267–268): 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2020-0104.

- Phyak, P., and P. I. De Costa. 2021. “Decolonial Struggles in Indigenous Language Education in Neoliberal Times: Identities, Ideologies, and Activism.” Journal of Language, Identity and Education 20 (5): 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1957683.

- Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

- Rahman, T. 2005. “Language Policy, Multilingualism and Language Vitality in Pakistan.” In Lesser-Known Languages of South Asia – Status and Policies, Case Studies and Applications of Information Technology, edited by A. Saxena and L. Borin, 73–106. Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110197785.1.73.

- Raza, A. 2013. “Pakistan.” In The History of Oxford University Press: Volume III: 1896 to 1970, edited by W. R. Louis, 673–691. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Rojo, L. M., and A. Del Percio, Eds. 2020. Language and Neoliberal Governmentality. London: Routledge.

- Rosa, J., and N. Flores. 2017. “Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective.” Language in Society 46 (5): 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000562.

- Sah, P. K. 2024. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Reproduction of Language Ideologies in English-Medium Instruction Programs in Nepal.” International Journal of Bilingualism 13670069241236701. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069241236701.

- Shah, W. A. 2021. “Decolonizing English Language Pedagogy: A Study of Cultural Aspects in English Language Coursebooks and Teachers’ Reflections in Pakistan.” Kieli, koulutus ja yhteiskunta 12 (6). https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-joulukuu-2021/decolonizing-english-language-pedagogy-a-study-of-cultural-aspects-in-english-language-coursebooks-and-teachers-reflections-in-pakistan.

- Shah, W. A., H. Y. Pardesi, and T. Memon. 2024. “Neoliberalizing Subjects Through Global ELT Programs.” TESOL Quarterly 58 (2): 693–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3242.

- Shah, S. W. A., and H. Pathan. 2016. “Representation of Western Culture in O’level English Language Textbooks.” ELF Annual Research Journal 18: 23–42.

- Shah, W. A., and H. Syed. Forthcoming. “On the Ontological Return of the damné: Tracing Coloniality in English Language Curriculum and Pedagogy in Postcolonial Pakistan.” Curriculum Inquiry.

- Silverman, D. 2017. “How Was it for You? The Interview Society and the Irresistible Rise of the (Poorly Analyzed) Interview.” Qualitative Research 17 (2): 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116668231.

- Simpson, W., and J. P. O’Regan. 2018. “Fetishism and the Language Commodity: A Materialist Critique.” Language Sciences 70:155–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2018.05.009.

- Sucerquia, E. P. A. 2020. “Critical Pedagogy and L2 Education in the Global South.” L2 Journal 12 (1): 21–33. https://doi.org/10.5070/L212246621.

- Sulis, G., A. Mairitsch, S. Babic, S. Mercer, and P. Resnik. 2023. “ELT teachers’ Agency for Wellbeing.” ELT Journal 78 (2): 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad050.

- Sultana, S. 2023. “Indigenous Ethnic Languages in Bangladesh: Paradoxes of the Multilingual Ecology.” Ethnicities 23 (5): 680–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211021520.

- Syed, H. 2022. “‘I Make My students’ Assignments Bleed with Red circles’: An Autoethnography of Translanguaging in Higher Education in Pakistan.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 42:119–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719052100012X.

- Syed, H. 2024. “Unraveling the Deficit Ideologies in ELT Education in Pakistan: A Decolonial Perspective.” TESOL Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.828.

- Thiong’o, N. W. 2012. Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing. New York: Columbia University Press.