ABSTRACT

Recently in Sex Education authors have raised concern with regards to Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in resource-poor countries as part of Western European development aid policy. It has been argued that the agency-focused and rights-based nature of ‘northern’ sexuality education puts too much responsibility on young people’s shoulders and disregards their insecurity and shame, as well as local culture more generally. By promoting a rights-based approach to CSE in countries in the South, European development organisations would risk being insensitive to local collective concerns, networks, sensitivities and affects, not least those based in religion. In addition to concerns related to CSE content, concern has been expressed about the unequal relationships between stakeholders from the global north versus the global south in the shaping of youth sexuality education. The issues raised are important and call for further elaboration and discussion, which is what we intend to initiate here. The viewpoints we present relate, among others, to the balance between structure and agency focused perspectives in CSE; the multiplicity of needs with regard to sexual agency; the precariousness of international partnerships; ongoing national and international controversies over sexual rights; and the absolute necessity for multicomponent approaches and careful community building as part of CSE implementation and scale-up.

Introduction

Several papers dealing with the implementation of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in resource-poor countries have been published in this journal over the past couple of years (e.g. Flink et al. Citation2017; Mukoro Citation2017; Rijsdijk et al. Citation2013; Steinhart et al. Citation2013; Svanemyr, Baig, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2015b; Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016). Most recently, Roodsaz (Citation2018) raised a number of critical issues on CSE programmes as part of Western European development aid policy. She focused specifically upon the implementation of the The World Starts With Me (WSWM) programme by Rutgers (a leading Dutch NGO in the area of SRHR) in Bangladesh. In part, the article built on an earlier report (Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016) of lessons learned in ten years implementation of the same CSE programme by that same NGO. The issues raised are important and beseech further elaboration and discussion, which is what we intend to initiate here.

Roodsaz begins by expressing serious worry about the agency-focused and rights-based nature of much ‘northern’ based sexuality education. She draws on a number of other authors (e.g. Lamb Citation2010; Rasmussen Citation2012) in asserting that these perspectives place too much responsibility on young people’s shoulders. They may be particularly ill-suited in southern settings, she argues. Roodsaz also maintains that, by adopting a logic marked by agency, subjectivity and autonomy, young people’s insecurity, uncertainty and shame as well as local religious and spiritual cultures are often disregarded. Overall, a ‘middle-class-oriented’, ‘secular’, rights- and health based Western European approach with its focus on the individual, is said to be insensitive to the broader field of local kinship and power relations, and the role of local collective concerns, networks, sensitivities and affects, not least those based in religion.

Roodsaz is also wary of unequal relationships between stakeholders from the global north versus the global south in the shaping of adolescent sexuality education. Interviews with seven stakeholders in Bangladesh provided the author with evidence that the idea of sexual rights was ‘often’ seen as culturally insensitive. ‘We claim rights only to make the donors happy, especially when they are from the Netherlands’, one of the interviewees declared (Roodsaz Citation2018: 116). There was evidence of frustration, annoyance and resistance to a rights-based approach among those spoken to. Informants claimed that sensitive topics such as sexual diversity, gender norms and child marriage are difficult to discuss in the context of Bangladesh. By promoting a rights-based approach to CSE in countries in the south, European development organisations and NGO representatives risk being culturally insensitive by seeking to advantage ‘the dominant, the transnational’ over ‘the particular’, Roodsaz argues. Her criticism (implicitly) attests to fears of possible cultural imperialism in the context of development cooperation. Her article strongly condemns the downplay of local modes of sexuality knowledge and politics and provides a strong plea for equal collaboration between parties, a collaboration in which Western donors must, primarily, play a facilitative role in the service of a conversation between important local stakeholders and, most importantly, young people themselves.

To a degree, the trepidations brought forward by Roodsaz are well-known to European NGOs working in countries in ‘the south’. They also partly overlap with problems identified (as well as ways forward suggested) by Vanwesenbeeck et al. (Citation2016) a couple of years ago. Indeed, a rights-based approach is central to much of the European development strategies in the area of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR), most certainly those employed by the Netherlands. Youth rights, participation and agency, as well as gender equality, power relations and social norms, are crucial to ‘the comprehensive’ in comprehensive sexuality education (cfr. Hague, Miedema, and Le Mat Citation2017; UNESCO Citation2016, Citation2018; UNFPA Citation2010, Citation2015). However, it is also clear that concepts such as ‘rights’, ‘agency’ and ‘empowerment’, or ‘comprehensive’ for that matter, may be differently defined for different groups, in different settings and by different actors. They are no static, homogeneous concepts, but are always subject to mutual tuning, diversification and modification over time and place. Below, we present some considerations that we believe to be relevant within this context.

The structure-agency debate

The question whether behaviour is principally determined by social structures or by the individual as a free agent, also known as the structure-agency debate, is a longstanding issue in the social and political sciences. The sexual agency of girls has been one domain in which the dilemma has been heavily disputed (e.g. Lamb and Peterson Citation2012; Murnen and Smolak Citation2012; Peterson Citation2010; Tolman Citation2012). Sexual empowerment and girls’ agency have been buzz-words in (and criticisms of) sexuality education since feminist analyses stressed women’s sexual gate-keepers’ role and their limited opportunities to develop authentic sexual subjectivity (e.g. Fine and McClelland Citation2006). In the wider development literature, (girls’) sexual empowerment has been explicitly linked to (their) overall (social, political, economic) empowerment (e.g. DFID Citation2012; Hawkins, Cornwall, and Lewin Citation2011).

Criticism of a focus on concepts such as sexual empowerment, agency, authenticity or sexual choice has a lot to do with the structural limitations put on their use. What do these concepts mean when girls’ sexuality is overdetermined by heteronormative ideologies, traditional gender stereotypes and a never ceasing stream of sexist media messages, not to mention macho pornographic imagery? How can girls’ sexual agency ever be authentic in a societal and structural context that so forcefully undermines it? Any claim to girls’ agency must be a mark of false consciousness, the argument goes. And what do sexual empowerment and agency mean for boys under the prevailing (hetero)sexual system? Surely not the same as for girls? Sexual agency is a complex, multidimensional concept, with different dimensions being (non)available for different groups. When a concept is so volatile, critics wonder if it is useful at all (Gavey Citation2012).

The attention given to sexual agency has also been criticised as echoing a neoliberal ideology in its highlighting of individual mastery. Being agentic has become very much the norm. Implicit to this is the unjust assumption that all persons can be equally agentic. Besides, it results in passing off responsibility for any consequences to the individual which, in turn, contributes to self-blame (Bay-Cheng Citation2015; Fahs and McClelland Citation2016; Gavey Citation2012). It must be stressed that (sexual) agency is not equally available to all girls, or to all groups for that matter. Structural conditions create limitations for all in terms of agency, but they limit (ideologically, socially and/or economically) disadvantaged groups especially strongly. Girls are relatively under-privileged in this respect, as are members of gender and sexual minorities. Nevertheless, differences also exist among girls, among boys, among gender and sexual minorities, and among different sociocultural groups with respect to opportunities to employ sexual agency, assertiveness and initiative. Structural inequalities and barriers to sexual health among young people in the global north are surely not to be neglected, as has been shown in the Netherlands (e.g. Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2017; Emmerink et al. Citation2017; De Graaf, Vanwesenbeeck, and Meijer Citation2015) as well as for the USA (e.g. Bay-Cheng Citation2015).

However, the argument of limited opportunity is relatively pressing when young people’s, and especially gender and sexual minorities’ sexuality in the global south is at stake. A multitude of environmental conditions and socio-economic barriers substantially disadvantage young people in resource-poor settings over young people in high-income countries in terms of sexual health and agency. Some conditions mentioned relatively often in the literature are, for instance, dire poverty, social marginalisation, family responsibilities and a lack of access to (secondary) education, and the persistent lack of access to sexual services and supplies (see, for example, Blum and Boyden Citation2018; UNESCO Citation2016, Citation2018; Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016). Girls who have initially benefitted from educational programmes supporting sexual agency and empowerment may, on the rebound, be met with violent backlash from family and community members, particularly when they attempt to apply skills like communication, negotiation, or leadership outside of the safe spaces provided by a programme (cfr. Kwauk and Braga Citation2017). More than once in this journal, has sexuality education that focuses predominantly on individual agency, been characterised as overly optimistic in light of the social structures determining young people’s sexuality (e.g. Lesko Citation2010), not least when they live in the global South. Roodsaz (Citation2018) rightfully raises concern that sexuality education, when unidimensionally and indiscriminately aiming for individual agency, puts an overly high demand on young people in countries such as Bangladesh.

The challenge lies in the balance

For sexuality education, the challenge lies always in finding the right balance. This is true, first, in relation to the balance between proper attention to young people’s (sexual) agency as well as to the structural barriers to its employment. Yes, structure and culture do influence young people’s (sexual) agency, but young people also have the opportunity to change those structures. In general, (sexual) health is increasingly conceptualised in a positive and dynamic way as the capacity to manage oneself in the light of environmental challenges (e.g. Huber et al. Citation2011; WHO Citation2017). The need not only to empower young people sexually but also to actively support them as advocates for change, has often been voiced (e.g. Haberland and Rogow Citation2015; Kwauk and Braga Citation2017). Some argue that, by allowing only a limited number of sexual knowledge building practices, (Dutch) CSE programmes are not as empowering as they claim to be (Naezer, Rommes, and Jansen Citation2017). But the CSE programmes implemented by Rutgers and its partners, do seek to strengthen young people’s empowerment and voice and, indeed, there is evidence that they succeed in doing so (Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016).

A second matter of balance is that attention to sexual agency, assertiveness or control needs to be well-adjusted to specific contexts, needs and possibilities. Young people benefit from enhanced agency when it helps them deal with the concrete environmental circumstances they have to navigate. Specifically for rural Bangladesh, Cash et al. (Citation2001) have put out a plea to ‘tell them their own stories’ to legitimise sexual and reproductive health education. Also in Bangladesh, van Reeuwijk and Nahar (Citation2013) and Nahar, van Reeuwijk, and Reis (Citation2013) found that restricting interactions and friendships between boys and girls, led boys in turn to express their feelings and masculinity through ‘eve-teasing’ and sexual harassment, while girls had few options to cope with this harassment. The authors argue that explicitly addressing this practice in combination with a sex-positive, rights-based approach towards young people’s sexuality can help boys and girls to recognise, express and respect wishes and boundaries. To do so, a basic understanding of their own rights and respecting the rights of others is key, as well as critical reflection on gender norms (van Reeuwijk and Nahar Citation2013). Agency may take many different forms, depending on the structural conditions it can or must be employed in. CSE always needs to find a balance in properly tuning agency promotion to divergent and (group) specific (local) agency needs. Under prevailing (hetero)sexual systems and double standards, the different agency needs and possibilities of boys and girls are evident. Likewise, sexual and gender minority youth may have different needs. In addressing agency and empowerment, gender, in all its diversity, must therefore be emphasised as part of sexuality education, alongside other contextual disparities (e.g. Fitzpatrick Citation2018; Haberland Citation2015; Kagesten et al. Citation2016).

Third, CSE programmes as well as young people themselves, need to find a balance in dealing with a cultural context that is, always, characterised by pluralism and diversity in the first place. There is never ‘just one culture’. Youth (sub)cultures may often differ from dominant cultural frames. There is always a degree of agency in young people’s dealing with different (possibly conflicting) ideologies and cultures, even in agency-constraining settings such as Bangladesh. As shown by van Reeuwijk and Nahar (Citation2013), young people in Bangladesh, as elsewhere, do not just accept and follow adult norms and messages about sexuality, but actively construe, navigating between what is being expected of them and what they want, need and feel themselves. This same study revealed young peoples’ sexual agency in that most of the unmarried adolescents created ways to actively express their curiosity about sexuality and looked for ways to experience romance, eroticism and pleasure despite religious prohibition and fear of social stigma and punishment.

Roodsaz (Citation2018) contrasts local ideologies with agency-focused CSE values. However, we are, instead, inclined to stress that it is one of the central aims of CSE to support young people in navigating the conflicting norms and messages that are, invariably, already present within a society. The same point has recently been made by Mukoro (Citation2017), who illustrates the multiplicity of (conflicting) ideologies, needs and practices in Nigeria, not least in relation to gender and sexuality. As Mukoro (Citation2017) shows, it is important for students to learn about these differences. Rather than teaching through a curriculum that attempts to resolve these tensions for learners, students are better prepared for the real world if they are introduced to conflict and given the competence to live, navigate and thrive within it. Mukoro (Citation2017) makes a plea for sexuality education that helps to cultivate and develop what we might call sex cultural intelligence. Sex cultural intelligent people realise, among others, that one always operates within a culture or some subsets of culture. They are able to keep an open mind about other sex cultures, and are able to critically engage in their own and others’ sexual cultures without being too easily influenced.

Critical reflection on (cultural, religious, societal) values regarding sexuality is promoted (UNESCO Citation2018) and broadly acknowledged as one of CSE’s primary learning objectives. In essence, there is a central role here for the ‘Socratic method’: a dialectical method involving discussion to discover beliefs, assumptions and arguments and eliminating contradictions so as to come to more general and shared solutions to value conflicts. The capacity for critical self-examination and critical thinking about one’s own culture and traditions also lies at the core of Nussbaum’s (Citation1997) argument for cultivating humanity and Sen and Nussbaum’s capability approach to human development (Nussbaum Citation2011). This approach is widely used in theories of social justice and accounts of development ethics, and inspired the creation of the UN’s Human Development Index (Robeyns Citation2016).

In sum, in balancing agency and structure it is key to understand that agents (re)produce structures and therefore have the opportunity to change them. Moreover, addressing agency in CSE includes equipping young people with the ability to critically reflect on and thereby navigate existing structures.

International partnerships are precarious

Last but certainly not least, an equitable power balance needs to be created between partners and stakeholders in international collaboration, in CSE or any other area. Overall, as noted by Roodsaz and others, partnerships in development aid are precarious. Colonial histories, strong versus weak positions in the global economy, and the (assumed) unidirectional nature of funding streams hamper the establishment of an equitable power balance between international partners. Interpersonal relations in technical cooperation, work style and life style issues are significant topics within this context. Imperialist tendencies and (northern) countries wishing to impose their values on other (southern) ones, are well-known phenomena in international cooperation. Clearly, such relations have been met with criticism, for instance in anti- or postcolonial scholarship, and ethical debate about development aid has grown and diversified (Gasper Citation1999). How best can we deal with the clash of values that may present itself between countries and stakeholders in a variety of areas? Gradually over the years, the human rights framework has become the standard for ethical relations in this respect, as well as in development cooperation more broadly (OHCHR Citation2006). There are two main rationales for the adoption of a human rights-based approach: (a) the intrinsic rationale, acknowledging that a human rights-based approach is the right thing to do, morally or legally; and (b) the instrumental rationale, recognising that a human rights-based approach leads to better and more sustainable human development outcomes. In practice, the reason for pursuing a human rights-based approach is usually a blend of these two.

In international cooperative work on CSE, a human rights based approach needs to be employed both with respect to programme content as well as the implementation process. For one thing, a proper balance needs to be found between northern and southern stakeholders in defining and tuning concepts such as ‘empowerment’, ‘rights’ and ‘agency’ (for girls as well as boys), or ‘comprehensiveness’ in the first place. In our experience, collaborative tuning with local stakeholders is one of the most crucial aspects of the implementation of sexuality education in the context of development cooperation (cf. Vanwesenbeeck Citation2016). This tuning definitely includes attention to religion. In Pakistan, for example, religious scholars have been involved in adapting the sexual education curriculum (called ‘life skills education’ locally), resulting in the inclusion of quotations from the Quran to support the manual (Chandra-Mouli et al. Citation2018). And in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia, Rutgers’ educational programme has, among others, been implemented in madrassa’s or religious schools.

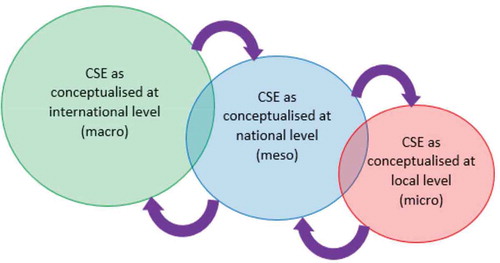

A thorough review of the international literature by Hague, Miedema, and Le Mat (Citation2017) on CSE related implementation processes shows, that approaches to CSE appear to vary at macro, meso, and micro levels and shape the varied understandings and delivery of CSE as a result. These variations are bound to change over time. Hague, Miedema, and Le Mat (Citation2017) express hope that, rather than the still all too prevalent top-down approach to guidance of CSE, a circular learning process (see ) will gradually prevail that will increasingly create understanding and consensus among different sets of actors and across varying contexts as to what CSE should, at a minimum, encompass. Clearly, the question of sexual rights will have to be key priority in these processes.

Sexual rights are controversial

As is clear from Roodsaz’ study and many others, sexual rights and sensitive topics such as same-sex sexual relationships and abortion have always been controversial, both in sex education and beyond. Even today, societal and political ambivalence and resistance are high, not least in traditional societies such as the USA and many developing countries. It is crucial therefore to acknowledge the political dimension of sexual rights (cf. Bijlmakers, de Haas, and Peters Citation2018). At UN gatherings, the matter of sexual rights is nearly always cause for heated debate. At the level of CSE delivery, resistance towards sexual rights and connected sensitive topics results in educators often skipping these subjects, teachers not adhering to programme fidelity, and content being transformed to better align with competing values (e.g. Flink et al. Citation2017; Rijsdijk et al. Citation2013; Sidze et al. Citation2017; Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016). Often, as in Roodsaz’ study, stakeholders narrow down the concept of sexual rights to the right to (reproductive) health and health care services.

However understandable, such adaptations detract from programme effectiveness. Programmes that do not emphasise gender, power and rights have been shown to have less likelihood of reducing rates of sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies (Haberland and Rogow Citation2015). There is evidence that a well designed rights-based approach in CSE programmes can lead to short-term positive effects on knowledge and attitudes, increased communication with parents about sex and relationships, and greater self-efficacy to manage risky situations. Longer-term significant positive effects have also been found for psychosocial and some behavioural outcomes (Rohrbach et al. Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2016). Beyond this, young people have a fundamental interest in learning about their sexual rights. Without close attention to human and sexual rights, truly empowering and inclusive sexual and public health cannot be achieved in the first place. The desirability of CSE being firmly grounded in internationally accepted human rights, not least the right to access appropriate health-related information, is now widely acknowledged by relevant international bodies such as UNFPA (Citation2010, Citation2015), UNESCO (Citation2018) and the European Expert Group on Sexuality Education (Citation2016).

But what exactly does a rights-based approach in CSE entail? According to Berglas, Constantine, and Ozer (Citation2014), it can be defined as the intersection of four main dimensions. First, it is rooted in the principle that young people have sexual rights, such as access to information and services and self-determination. Second, a rights-based approach goes beyond health-oriented goals such as reducing unintended pregnancies and STIs, to aim for empowerment. Third, it implies the adoption of a broad curriculum, including attention to gender norms, violence, individual rights and responsibilities in relationships, sexual orientation, sexual expression and pleasure. Finally, a participatory teaching approach aims to engage young people in critical thinking. As such, a rights-based approach includes and goes well beyond the health-based approach. Moreover, a rights-based approach requires attention be given to sensitive topics as abortion, sexual diversity and pleasure. The curriculum in Bangladesh, for example, spends ample time on issues such as gender, violence, responsibility and critical thinking.

Again, however, a balance needs to be found, in this case between health and rights perspectives in sexuality education. Specifically for Bangladesh, an approach focusing only on health has been said to be ineffective in that it principally problematises young people’s sexual behaviour (Nahar, van Reeuwijk, and Reis Citation2013; van Reeuwijk and Nahar Citation2013). van Reeuwijk and Nahar (Citation2013) argue that, also in Bangladesh, a rights-based and sex-positive approach that goes beyond a health-based approach will better help young people to make sense of the multiplicity of messages they encounter and reduce unnecessary feelings of guilt and anxiety. Moreover, they argue that only a deep rooted respect for young peoples’ sexual rights may lead to outcomes such as empowerment and a reduction of gender inequality, sexual violence, shame, fear and insecurity, discrimination and stigma.

However, when resistance to sexual rights is strong, it is not always necessary to make a rights-based approach explicit in CSE materials, as implicit framing and language can be useful tools to make the content contextually appropriate and acceptable. Moreover, by building trust over time, an expansion of content to become progressively more rights-based is feasible (Nasserzadeh and Pejman Citation2017). It is important, therefore, that educators, including parents and the wider community are supported in discussing, advocating, acknowledging and respecting young people’s sexual rights. Controversy over sexual rights is one of the main reasons why the promotion of sexual and reproductive health demands multiple strategies be used at the same time. Therefore, NGOs such as Rutgers are, when offered the opportunity, increasingly and wholeheartedly dedicated to not limiting themselves to the delivery of CSE alone.

Not by CSE alone

The need for multicomponent approaches (bringing together actions to improve individual empowerment, strengthen the health system and create a more SRHR supportive environment) has been apparent for some time (e.g. Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Caceres Citation2011; Fitzpatrick Citation2018; UNESCO Citation2018; Vanwesenbeeck Citation2011). It was felt particularly deeply when the response to HIV shifted from an emergency to a longer-term response (cf. Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Caceres Citation2011), and when it became clear that a change from HIV prevention focusing on the individual to a more comprehensive strategy modifying social conditions was central to success in tackling the epidemic. A social/structural approach was called for which addresses the key drivers of HIV vulnerability that affect the ability of individuals to protect themselves and others against HIV. Multicomponent approaches are more sustainable than single-component interventions because they also achieve change in social and cultural factors. They are more synergetic because they address both demand and supply in relation to the uptake of health services. They target different groups and are therefore more diverse in their reach. Moreover, the use of a variety of methods and strategies offers a better chance of reaching a variety of groups with different needs and circumstances.

Gradually, multiple approaches have come to been implemented in the area of SRHR promotion (e.g. Chandra-Mouli et al. Citation2015; Denno, Hoopes, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2015; Fonner et al. Citation2014; Kesterton and Cabral de Mello Citation2010; Svanemyr et al. Citation2015a; Svanemyr, Baig, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2015b; UNESCO Citation2018; Vanwesenbeeck Citation2014). Svanemyr, Baig, and Chandra-Mouli (Citation2015b), for example, have argued for an ‘ecological framework’ to creating enabling environments at the individual level (empower girls, create safe spaces), at the relationship level (build parental support, peer support networks), at the community level (engage men and boys, transform gender and other social norms), and at the broad societal level (promote laws and policies that protect and promote human rights). A 20-year ICPD progress report by Chandra-Mouli et al. (Citation2015) shows that sexuality education is most impactful when school-based programmes are complemented by community elements, including condom distribution, building awareness and support, increasing demand for SRH education and services among youth, addressing gender inequalities, providing training for health providers, and involving parents, teachers and other community gatekeepers such as religious leaders. The authors argue for ‘SRH intervention packages’ to improve CSE’s effectiveness. There is also heightened awareness that sexuality educators need proper facilitation, training and support, both within and outside schools to deliver sexuality education in an effective, enabling and inclusive way (e.g. Vanwesenbeeck et al. Citation2016; WHO & BZgA, Citation2017). There is a strong need to link school-based education with non-school-based youth-friendly health services and also with social marketing and franchising (Kesterton and Cabral de Mello Citation2010).

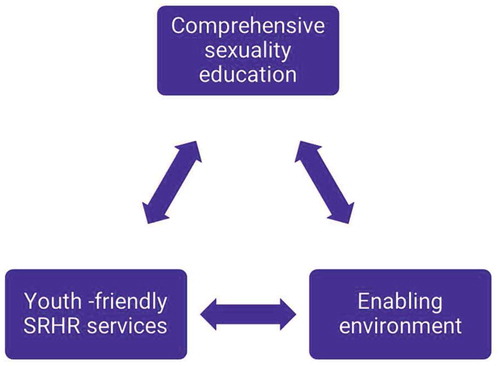

From our experience in a high income country like the Netherlands with its relatively favourable SRHR situation, we have learned that we have got to where we are now by unrelentingly addressing the social drivers of SRHR at multiple levels. As an international NGO, Rutgers has taken this experience to its programming in other countries as well. We work, for instance, from the ecological principle that at least three crucial conditions have to be met for adequate SRHR to take root: the widespread implementation of high quality comprehensive sexuality education; low-threshold access to youth friendly sexual health services and supplies; and an overall enabling, supportive sociocultural environment (see ). Each one of these three drivers is crucial, but on their own each of them is insufficient to establish desired change.

Using such a philosophy, a diverse palette of strategies may be employed to build a supportive, enabling use for school-based CSE. A relatively recent strategy to create a support system for school-based CSE is the employment of a so-called Whole School Approach for Sexuality Education (WSA for SE) (Rutgers Citation2016; see also Vanwesenbeeck Citation2016). Pilot evaluations of this approach in Western Kenya and Eastern Uganda are beginning to show positive results (Flink, Schaapveld, and Page Citation2018). For instance, links with nearby SRH service providers have been newly established and have increased young people’s access to SRHR information. School environments have become significantly safer and the percentage of pupils who feel completely or mostly secure at school has risen. The level of student participation and decision-making in schools has increased with students taking part in strategic decision making about the school’s code of conduct, and peer educators have been trained and coached as extra-curricular SRHR educators. Parental involvement has also increased substantially and parents are increasingly interested and supportive. And schools themselves have taken important steps in creating ownership and future sustainability in terms gaining the (financial) support of parents, community and political stakeholders. In addition, a WSA for SE has successfully advanced the development of a teacher supportive infrastructure. WSA for SE schools were shown to have developed a number of techniques to increase teacher motivation, such as teacher teams to improve collaboration and mentorship. Moreover, teachers have reported changes in their own beliefs, attitudes and knowledge regarding the teaching of sensitive topics such as contraception, abortion and sexual diversity, which they had previously skipped. Teachers also reported the increased use of and confidence in participatory teaching methods (see Flink, Schaapveld, and Page Citation2018).

Tactful, careful community building

In general, there is a huge need for community building to strengthen positive attitudes towards sexuality education in general and to sexual rights specifically. This has been shown to be possible and fruitful, also in sex conservative settings, provided it is implemented with tact and care (e.g. Chandra-Mouli et al. Citation2018; Denno, Hoopes, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2015). In Uganda, Save the Children’s Gender Roles, Equity and Transformation (GREAT) project successfully has used a Community Action Cycle to engage communities and create support for adolescent SRHR and more gender equitable norms (Institute for Reproductive Health Citation2016). In Pakistan, NGO Rutgers Pakistan has been successful in advancing support for sexuality education with careful implementation of a number of key strategies that included sensitising and engaging key stakeholders, including religious groups, schools, health and education government officials, parents and young people themselves; tactfully designing and framing the curricula with careful consideration of context and sensitive topics; institutionalising programmes within the school system; showcasing school programmes to increase transparency; and engaging the media to enhance and build positive public perceptions (Chandra-Mouli et al. Citation2018; Svanemyr et al. Citation2015a; Svanemyr, Baig, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2015b).

In Bangladesh, BRAC university has been successful in creating a public space and dialogue on sexuality and rights in a likewise challenging environment (Rashid et al. Citation2011). BRAC set out on a community building project that had a particular interest in bridging international and local understandings of sexual and reproductive rights. Over a four-year period, a series of learning and capacity building activities has been organised consisting of training workshops, meetings, conferences and dialogues. These brought together different combinations of stakeholders – members of sexual minorities, academics, service providers, advocacy organisations, media and policy makers. This process contributed to developing more effective advocacy strategies through challenging representations of sexuality and rights in the public domain. Gradually, these efforts gave visibility to hidden or stigmatised sexuality and rights issues through interim outcomes that have created important steps towards changing attitudes and policies. These interim outcomes included creating safe spaces for sexual minorities to meet and strategise, the development of learning materials for university students, and engagement with legal rights groups on issues of sexual rights. As BRAC’s work has shown, a careful, step-by-step process can raise public debate on sexuality and rights and make issues such as discrimination more visible to policy makers and other key stakeholders, even in a context such as Bangladesh. Moreover, the project has shown that, in a challenging context such as Bangladesh, respect for sexual rights is important, desired and attainable.

It is important to note, however, that challenging contexts can be found everywhere and are certainly not limited to the global South. As a number of recent publications in this journal demonstrate, community building to enhance attitudes towards sexuality education is as important in (parts of) countries such as the USA (e.g. Secor-Turner et al. Citation2017), Australia (Ferfolja and Ullman Citation2017) and Ireland (Wilentz Citation2016). In the Netherlands, relentless advocacy has brought about continued success. In addition to community building at a national level, the usefulness of regional cooperation at the level of continents has also been illustrated, for instance for Latin America (Steinhart et al. Citation2013; also see UNFPA Citation2015).

Community building is a prerequisite to the proper contextualisation of CSE programmes, i.e. the process of adoption and adaptation of a programme in and to a certain context. There may be evidence that sexuality programmes may be successfully transported from one setting to another and still have a positive impact on knowledge, attitudes or behaviours (Fonner et al. Citation2014; Kirby, Obasi, and Laris Citation2006; UNESCO Citation2018). However, in the light of applicability and effectiveness as well as local ownership and sustainability, it is preferable that they be tailored to local needs in culturally sensitive ways. As shown by Roodsaz (Citation2018) for Rutgers’ The World Starts With Me programme in Bangladesh, cultural sensitivity remains to be a challenge, especially when aspects deemed essential (such as a rights-based perspective) are not supported by local stakeholders’ norms and practices. The statement made by one of Roodsaz’ interviewees that, ‘we claim rights only to make the donors happy, especially when they are from the Netherlands’, suggests that the adoption process of CSE in Bangladesh has (or had at the time) not been fully complete. In fact, contextualisation is never complete. It is an ongoing practice. Roodsaz’ interviewee may have been relatively new to the process. Staff turnover, policy change and global developments make it necessary constantly to renew and intensify efforts. In addition, some people may simply be more open to the concept of sexual rights than others. There is also reason to believe that the adoption of new cultural values is more difficult when adherence to traditional values is relatively strong (Villar and Concha Citation2012). Because of this, respect for sexual rights may always remain patchy, with proponents and adversaries entangled in eternal battles and/or with support for some rights being relatively strong (e.g. the right to information) but not so for others (e.g. same-sex sexuality or abortion rights). To a certain extent, international programming in development aid contexts is always a matter of subtle manoeuvring, balancing and compromise. Cultural sensitivity is a tough job never done and discussion about it should remain on the agenda. Roodsaz (Citation2018) was right once again to ring the alarm. Her article resonates well with the suggestion by Chandra-Mouli and colleagues (Citation2018) of the need to share experiences on (local) resistance to sexuality education and try and develop a toolbox of strategies for community uptake. There is no alternative to ‘simply’ keeping up the pace and holding strong.

Two final observations are worth making on international cooperation and movement building. First, given cultural multiplicity and the diversity of local organisations and stakeholders in every setting, we urge international NGO professionals to find local allies with whom they share perspectives. From a shared perspective, collaboration is less stressful, civil society strengthening is more likely to take root, and progress is easier to attain. Additionally, it may be strategically wise to connect to parties such as local decision-makers, whose views are not necessarily the same as your own but who are in a position to structurally advance the SRHR agenda. Second, many knowledge gaps remain about the complex processes involved in CSE implementation and SRHR promotion more generally. There is a pressing need therefore for further research on effective mechanisms, reach and impact as well as design, delivery, advocacy and community building. Implementation research in its diverse forms is a key component to add to our much needed multiple approach. For at the end of the day, SRHR does not thrive by CSE alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Auerbach, J. D., J. O. Parkhurst, and C. F. Caceres. 2011. “Addressing Social Drivers of HIV/AIDS for the Long-Term Response: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations.” Global Public Health 6 (Suppl 3): S293–309.

- Bay-Cheng, L. Y. 2015. “The Agency Line: A Neoliberal Metric for Appraising Young Women’s Sexuality.” Sex Roles 73 (7–8): 279–291.

- Berglas, N. F., N. A. Constantine, and E. J. Ozer. 2014. “A Rights-Based Approach to Sexuality Education: Conceptualization, Clarification and Challenges.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 46 (2): 63–72.

- Bijlmakers, L., B. de Haas, and A. Peters. 2018. “The Political Dimension of Sexual Rights. : Commentary on the Paper by Chandra-Mouli Et Al.: A Never-Before Opportunity to Strengthen Investment and Action on Adolescent Contraception, and What We Must Do to Make Full Use of It.” Reproductive Health 15 (1): 18.

- Blum, R., and J. Boyden. 2018. “Understand the Lives of Youth in Low-Income Countries.” Nature 554 (7693): 435–437.

- Cash, K., S. I. Khan, H. Nasreen, A. Bhuiya, S. Chowdhury, and A. M. R. Chowdhury. 2001. “Telling Them Their Own Stories: Legitimizing Sexual and Reproductive Health Education in Rural Bangladesh.” Sex Education 1 (1): 43–57.

- Cense, M., and R. R. Ganzevoort. 2017. “Navigating Identities: Subtle and Public Agency of Bicultural Gay Youth.” Journal of Homosexuality 64 (5): 654–670.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., M. Plesons, S. Hadi, Q. Baig, and I. Lang. 2018. “Building Support for Adolescent Sexuality and Reproductive Health Education and Responding to Resistance in Conservative Contexts: Cases from Pakistan.” Global Health Science and Practice 6 (1): 128–136.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., J. Svanemyr, A. Amin, H. Fogstad, L. Say, F. Girard, and M. Temmerman. 2015. “Twenty Years after International Conference on Population and Development: Where are We with Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights?” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (1 Suppl): S1–6.

- De Graaf, H., I. Vanwesenbeeck, and S. Meijer. 2015. “Educational Differences in Adolescents’ Sexual Health: A Pervasive Phenomenon in A National Dutch Sample.” The Journal of Sex Research 52 (7): 747–757.

- Denno, D. M., A. J. Hoopes, and V. Chandra-Mouli. 2015. “Effective Strategies to Provide Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Services and to Increase Demand and Community Support.” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (1 Suppl): S22–41.

- DFID. 2012. Empowerment: A Journey Not A Destination. Pathways Synthesis Report. Brighton: Pathways of Women’s Empowerment Research Programme Consortium.

- Emmerink, P. M., R. J. Van den Eijnden, T. F. Ter Bogt, and I. Vanwesenbeeck. 2017. “The Impact of Personal Gender-Typicality and Partner Gender-Traditionality on Taking Sexual Initiative: Investigating a Social Tuning Hypothesis.” Frontiers in Psycholology 8: 107. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00107.

- European Expert Group on Sexuality Education. 2016. “Sexuality Education – What Is It?” Sex Education 16 (4): 427–431.

- Fahs, B., and S. I. McClelland. 2016. “When Sex and Power Collide: An Argument for Critical Sexuality Studies.” The Journal of Sex Research 53 (4–5): 392–416.

- Ferfolja, T., and J. Ullman. 2017. “Gender and Sexuality in Education and Health: Voices Advocating for Equity and Social Justice.” Sex Education 17 (3): 235–241.

- Fine, M., and S. McClelland. 2006. “Sexuality Education and Desire: Still Missing after All These Years.” Harvard Educational Review 76 (3): 297–338.

- Fitzpatrick, K. 2018. “Sexuality Education in New Zealand: A Policy for Social Justice?” Sex Education. doi:10.1080/14681811.2018.1446824.

- Flink, I., A. Schaapveld, and A. Page. 2018. The Whole School Approach for Sexuality Education. Pilot Study Results from Kenya and Uganda. Utrecht: Rutgers.

- Flink, I. J. E., S. M. O. Mbaye, S. R. B. Diouf, S. Baumgartner, and P. Okur. 2017. “Collaboration between a Child Telephone Helpline and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Organisations in Senegal: Lessons Learned.” Sex Education 18 (1): 32–46.

- Fonner, V. A., K. S. Armstrong, C. E. Kennedy, K. R. O’Reilly, and M. D. Sweat. 2014. “School Based Sex Education and HIV Prevention in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS One 9 (3): e89692.

- Gasper, D. 1999. “Ethics and the Conduct of International Development Aid: Charity and Obligation.” Forum for Development Studies 26 (1): 23–57.

- Gavey, N. 2012. “Beyond ‘Empowerment’? Sexuality in a Sexist World.” Sex Roles 66 (11–12): 718–724.

- Haberland, N., and D. Rogow. 2015. “Sexuality Education: Emerging Trends in Evidence and Practice.” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (1 Suppl): S15–21.

- Haberland, N. A. 2015. “The Case for Addressing Gender and Power in Sexuality and HIV Education: A Comprehensive Review of Evaluation Studies.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 41 (1): 31–42.

- Hague, F., E. A. J. Miedema, and M. L. J. Le Mat. 2017. Understanding the ‘Comprehensive’ in Comprehensive Sexuality Education. A Literature Review. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

- Hawkins, K., A. Cornwall, and T. Lewin. 2011. Sexuality and Empowerment: An Intimate Connection. Pathways Policy Paper. Brighton: Pathways of Women’s Empowerment Research Programme Consortium.

- Huber, M., J. A. Knottnerus, L. Green, H. van der Horst, A. R. Jadad, D. Kromhout, B. Leonard, et al. 2011. “How Should We Define Health?” British Medical Journal 343: d4163.

- Institute for Reproductive Health. 2016. GREAT Project How-To Guide. GREAT’s Approach to Improving Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Reducing Gender-Based Violence. Washington: Georgetown University. http://irh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/GREAT_Project_How-to-Guide.pdf.

- Kagesten A., S. Gibbs, R.W. Blum, C. Moreau, V. Chandra-Mouli, A. Herbert 2016. “Understanding Factors that Shape Gender Attitudes in Early Adolescence Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review.” PLoS One 11 (6): e0157805.

- Kesterton, A. J., and M. Cabral de Mello. 2010. “Generating Demand and Community Support for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services for Young People: A Review of the Literature and Programs.” Reproductive Health 7: 25.

- Kirby, D., A. Obasi, and B. A. Laris. 2006. “The Effectiveness of Sex Education and HIV Education Interventions in Schools in Developing Countries.” World Health Organisation Technical Report Series 938: 103–150; discussion 317–41.

- Kwauk, C., and A. Braga. 2017. Translating Competencies to Empowered Action. A Framework for Linking Girls’ Life Skills Education to Social Change. Washington D.C: Brookings.

- Lamb, S. 2010. “Feminist Ideals for A Healthy Female Adolescent Sexuality: A Critique.” Sex Roles 62 (5): 294–306.

- Lamb, S., and Z. D. Peterson. 2012. “Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Empowerment: Two Feminists Explore the Concept.” Sex Roles 66 (11–12): 703–712.

- Lesko, N. 2010. “Feeling Abstinent? Feeling Comprehensive? Touching the Affects of Sexuality Curricula.” Sex Education 10 (3): 281–297.

- Mukoro, J. 2017. “The Need for Culturally Sensitive Sexuality Education in a Pluralised Nigeria: But Which Kind?” Sex Education 17 (5): 498–511.

- Murnen, S. K., and L. Smolak. 2012. “Social Considerations Related to Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Empowerment: A Response to Lamb and Peterson.” Sex Roles 66 (11–12): 725–735.

- Naezer, M., E. Rommes, and W. Jansen. 2017. “Empowerment through Sex Education? Rethinking Paradoxical Policies.” Sex Education 17 (6): 712–728.

- Nahar, P., M. van Reeuwijk, and R. Reis. 2013. “Contextualising Sexual Harassment of Adolescent Girls in Bangladesh.” Reproductive Health Matters 21 (41): 78–86.

- Nasserzadeh, S., and A. Pejman. 2017. Sexuality Education Wheel of Context: A Guide for Sexuality Educators, Advocates and Researchers. United States.

- Nussbaum, M. 1997. Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education. Cambridge. Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating Capabilities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- OHCHR (Office Of The United Nations High Commissioner For Human Rights). 2006. Frequently Asked Questions on a Human Rights-Based Approach to Development Cooperation. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

- Peterson, Z. D. 2010. “What Is Sexual Empowerment? A Multidimensional and Process-Oriented Approach to Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Empowerment.” Sex Roles 62 (5–6): 307–313.

- Rashid, S. F., H. Standing, M. Mohiuddin, and F. M. Ahmed. 2011. “Creating a Public Space and Dialogue on Sexuality and Rights: A Case Study from Bangladesh.” Health Research Policy and Systems 9 (Suppl 1): S12.

- Rasmussen, M. L. 2012. “Pleasure/Desire, Sexularism and Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 12 (4): 469–481.

- Rijsdijk, E. L., R. Lie, A. E. R. Bos, J. N. Leerlooijer, and G. Kok. 2013. “Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Implications for Comprehensive Sex Education among Young People in Uganda.” Sex Education 13 (4): 409–422.

- Robeyns, I. 2016. “The Capability Approach.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Winter 2016, edited by E. N. Zalta. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/capability-approach/

- Rohrbach, L. A., N. F. Berglas, P. Jerman, F. Angulo-Olaiz, C. P. Chou, and N. A. Constantine. 2015. “A Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum for Adolescents: 1-Year Outcomes from A Cluster-Randomized Trial.” Journal of Adolescent Health 57 (4): 399–406.

- Roodsaz, R. 2018. “Probing the Politics of Comprehensive Sexuality Education: ‘Universality’ versus ‘Cultural Sensitivity’: A Dutch–Bangladeshi Collaboration on Adolescent Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 18 (1): 107–121.

- Rutgers. 2016. We All Benefit. An Introduction to the Whole School Approach for Sexuality Education. Utrecht: Rutgers. https://www.rutgers.international/what-we-do/comprehensive-sexuality-education/whole-school-approach-sexuality-education-step-step.

- Secor-Turner, M., B. A. Randall, K. Christensen, A. Jacobson, and M. L. Meléndez. 2017. “Implementing Community-Based Comprehensive Sexuality Education with High-Risk Youth in a Conservative Environment: Lessons Learned.” Sex Education 17 (5): 544–554.

- Sidze, E. M., M. Stillman, S. Keogh, S. Mulupi, C. P. Egesa, E. Leong, M. Mutua, W. Muga, A. Bankole, and C. O. Izugbara. 2017. From Paper to Practice: Sexuality Education Policies and Their Implementation in Kenya. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

- Steinhart, K., A. von Kaenel, S. Cerruti, P. Chequer, R. Gomes, C. Herlt, and O. Horstick. 2013. “International Networking for Sexuality Education: A Politically Sensitive Subject.” Sex Education 13 (6): 630–643.

- Svanemyr, J., A. Amin, O. J. Robles, and M. E. Greene. 2015a. “Creating an Enabling Environment for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Framework and Promising Approaches.” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (1 Suppl): S7–14.

- Svanemyr, J., Q. Baig, and V. Chandra-Mouli. 2015b. “Scaling up of Life Skills Based Education in Pakistan: A Case Study.” Sex Education 15 (3): 249–262.

- Tolman, D. L. 2012. “Female Adolescents, Sexual Empowerment and Desire: A Missing Discourse of Gender Inequity.” Sex Roles 66 (11–12): 746–757.

- UNESCO. 2016. Review of the Evidence on Sexuality Education. Report to Inform the Update of the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. Paper prepared by Paul Montgomery and Wendy Knerr, University of Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Intervention. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2018. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education - an Evidence-Informed Approach. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNFPA. 2010. Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Advancing Human Rights, Gender Equality and Improved Sexual and Reproductive Health. New York: UNFPA.

- UNFPA. 2015. Emerging Evidence, Lessons and Practice in Comprehensive Sexuality Education. A Global Review. Paris: UNESCO.

- van Reeuwijk, M., and P. Nahar. 2013. “The Importance of a Positive Approach to Sexuality in Sexual Health Programmes for Unmarried Adolescents in Bangladesh.” Reproductive Health Matters 21 (41): 69–77.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I. 2011. “High Roads and Low Roads in HIV/AIDS Programming: High Time for a Change of Itinerary.” Critical Public Health 21: 289–296.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I. 2014. “An Ecological Perspective on Sex-Ed Evaluation Research.” Paper presented at Sharenet International Expert Meeting on CSE, The Hague, October 16, 2014.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I., J. Westeneng, T. de Boer, J. Reinders, and R. van Zorge. 2016. “Lessons Learned from a Decade Implementing Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Resource Poor Settings: The World Starts with Me.” Sex Education 16 (5): 471–486.

- Villar, M. E., and M. Concha. 2012. “Sex Education and Cultural Values: Experiences and Attitudes of Latina Immigrant Women.” Sex Education 12 (5): 545–554.

- WHO. 2017. Sexual Health and Its Linkages to Reproductive Health: An Operational Approach. Geneva: WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA. 2017. Training Matters: A Framework for Core Competencies of Sexuality Educators. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA).

- Wilentz, G. 2016. “The Importance of European Standards and a Human Rights-Based Approach in Strengthening the Implementation of Sexuality Education in Ireland.” Sex Education 16 (4): 439–445.