ABSTRACT

Sexual health policies explicitly aim to encourage young people to take responsibility for their sexuality to prevent adverse outcomes such as unintended pregnancies, STIs and sexual assault. In Europe and North America, ‘choice’ has become a central concept in sexual and reproductive health policy making. However, the concept of choice is not unproblematic, not least because the cultural emphasis on individual responsibility obscures structural limitations and inequalities, and mutual responsibility between partners. Moreover, studies on the life stories of young people show how agency is forged and expressed within a social context and is manifested through responsiveness to others. This raises the question of how we can conceptualise sexual agency in a way that includes this sociality. How can we rethink sexual agency beyond autonomy? This article explores these issues using data from four separate research projects that shared the aim of exploring young people’s sexual agency in different areas. Drawing on findings from these studies, it advances a multicomponent model of sexual agency that connects individual choice to the social, moral and narrative context which young people navigate.

Introduction

Much effort in the field of sexual health promotion is aimed at empowering young people to make ‘healthy’ choices, such as having safe sex, being assertive about their boundaries, and asking for consent (Mastro and Zimmer-Gembeck Citation2015; Ortiz and Shafer Citation2017; Schaalma Herman et al. Citation2004; Stanley et al. Citation2017). Sexual health policies in the Global North are however strongly influenced by neoliberal ideology, which conceptualises individuals as rational, entrepreneurial actors whose moral authority is determined by their capacity for autonomy and self-care (Brown Citation2003). Although this particular discourse promotes the value of individual freedom and choice, it also demands actors to be in control and responsible at all times (Bay-Cheng Citation2015). Sexual health policies informed by this discourse explicitly aim to help young people to take responsibility and control their sexuality in order to prevent adverse outcomes such as unintended pregnancy, STIs or sexual assault (Bay-Cheng Citation2015).

More generally, in the Western social context, ‘choice’ has become a central organising concept in the constitution of modern identity: ‘it is a key requirement of contemporary self-identity that we are good choice-makers’ (Harris and Dobson Citation2015, 148). In sexual health policy making, the concept of individual choice is manifest in the emphasis on the right to choose (Plummer Citation2003). This is a discourse of individual entitlement: the focus is on the individual ‘choosing’ subject (Richardson Citation2017). However, as a researcher who has conducted interviews with numerous young people concerning their sexual life histories, I have observed that respondents express few straightforward, ‘autonomous’ choices. Instead, they often describe social motivations for having sex or refraining from it and put emphasis on the importance of not damaging their social status among peers, or the expectations of their family and partners. This raises the question of how best we can conceptualise sexual agency in a way that includes this sociality, and how can we rethink sexual agency beyond a focus on autonomy?

This paper aims to develops a new theory of the sexual agency of young people. Drawing on findings from four separate research projects conducted with Dutch young people in the Netherlands, it advances a multicomponent model to broaden our view of young people’s negotiations of sexual agency. Each of the four studies drawn upon included a rich cultural diversity of participants. Their varying and intersecting cultural backgrounds contributed to a better understanding of how different sexual cultures interact, and offer possibilities for analysing both differences and commonalities in discourses and practices. The characteristics of contemporary Dutch society, including attitudes and ideologies concerning gender, sexuality and migration, rights and obligations, and sexual health policies, influence the broader social landscape young people have to navigate. In analysing how young people negotiate their identities, their stories and their practices, different components of sexual agency become visible. In a parallel paper (Cense Citation2018), I explore future directions for meaningful sexuality education, following up on the four components of sexual agency presented in this paper. Together these two papers aim to provide a Dutch response to Bell’s (Citation2012, 294) recommendation that understanding the different forms of sexual agency exhibited by young people will support the development of sexual health programmes informed by ‘the grounded realities of young people’s sexual lives’.

Sexual agency

Most definitions of sexual agency put emphasis on the control of the individual over her or his own body. Jackson (Citation1996), for example, defines sexual agency in terms of the right and ability to define and control your own sexuality, free from coercion and exploitation. Other scholars emphasise the role of sexuality and the body in developing sexual identity, or becoming a sexual subject. Bryant and Schofield (Citation2007), for example, state that it is through sexual practice that the sexual subject is brought into being: ‘Far from a passive surface upon which sexual scripts are inscribed, the body in sexual action is itself a dynamic force in generating sexual subjectivities’ (321). Tolman (Citation2012) adds that the body generates knowledge about context as well: ‘By embodied desire, we designate sexual and pleasurable feelings in and of the body that constitute a form of knowledge about the self, one’s relationships and one’s cultural contexts or social worlds’.

Agency is strongly connected to power relations between people. Lois McNay (Citation2000, 16) defines agency as ‘the capacity to manage actively the often discontinuous, overlapping or conflicting relations of power’. A slightly different perspective is offered by Saba Mahmood (Citation2001, 210), who argues that individual agency should not be seen as ‘the undominated self that existed prior to operations of power’, but as the product of these operations of power. She proposes understanding agency ‘not simply as a synonym for resistance to relations of domination, but as a capacity for action that specific relations of subordination create and enable’. Translating Mahmood’s approach to agency to the domain of sexuality would situate sexual agency not only in the longing for sexual freedom and the striving for sexual rights, but also in gaining strength or developing navigating skills while enduring unequal sexual relationships or leading a double life. Quỳnh Phạm (Citation2013) adds to this work by introducing the concept of bonded agency. She raises the question of what we understand by the self and emphasises that social relationships should not be construed as external factors that either constrain or enable agency, but instead as constitutive of agency and its expression. This mirrors the concept of the individual as an ‘embedded self’ expressed by Muslim feminists in the study by Baukje Prins (Citation2006). Stephen Bell (Citation2012, 284) also emphasises the social navigation process in his definition of sexual agency as: ‘processes where young people become sexually active and the strategies, actions and negotiations involved in maintaining relationships and navigating broader social expectations’. Sexual agency is therefore closely connected to the concept of strategic negotiation, or the processes through which people situate themselves, their families and their sexual and reproductive choices in a larger social context (Barcelos and Gubrium Citation2014). These negotiations move beyond individual interpretations of social reality to a deeper recognition of how social norms, policies, and relationships shape what people think about their (sexual) selves (Schalet Citation2010). Schalet draws attention to the process of storytelling by which young people develop and express narrative agency, which may be defined as the capacity to `weave out of those narratives and fragments of narratives a life story that makes sense for the individual selves´ (Benhabib Citation1999, 344).

Agency is also connected to power relations at a macro level, i.e. to morality and to broader structural inequalities (Bay-Cheng Citation2015; Bettie Citation2003; Lamb Citation1997). Laina Bay-Cheng (Citation2015) argues that young women are now not only accountable to the gendered moralism of the virgin-slut construct, but also must adhere to neoliberal ideas of individual liberty and responsibility. To prove that they are ‘free agents’, young women have to claim that their sexual choices (whether activity or abstinence) and the consequences of these choices (for good or for bad) are their own responsibility. Structural inequalities such as classism and racism, however, obstruct the possibility of claiming sexual agency (Armstrong et al. Citation2014; Attwood, Citation2007). As a result, the ‘effective presentation of one’s sexual self is not simply a matter of individual skill: some girls are bolstered or shielded by race and class privilege while others must ceaselessly work against racist and classist stereotypes of hyper sexuality and irresponsibility’ (Bay-Cheng Citation2015, 285). In a similar vein, Tolman, Anderson, and Belmonte (Citation2015, 303) argue that Black, Latina, Asian and poor or working class girls’ sexuality is ‘always already presumed to be the (failed) embodiment of adolescent girls’ sexuality and thus not eligible to make any choices at all’.

Summarising, sexual agency is connected to different concepts of the self, being autonomous or bonded, being in control of one’s body or becoming a subject through the body. Relationships play a crucial role in creating possibilities and constraints for individuals when it comes to developing sexual agency. Sexual agency can be viewed as the strategic negotiations of an individual to situate oneself and one’s choices in a social context, maintain relationships and make sense of experiences. These strategic negotiations take place in a broader social and cultural context which imposes constraints on the agency of all people; however, due to structural inequalities some people experience more constraints than others.

Social context – the Netherlands

The social and political context governs the options, choices and resources that are available to young people, as well as the conditions under which people can make choices (Carmody and Ovenden Citation2013; Plummer Citation1995; Shannahan Citation2009). Key components of this social and political context include cultural beliefs and customs; policies, rights and rules, such as LGBT rights and laws on abortion; the educational system; social and gender norms; and family roles and expectations. The Netherlands is characterised by a fairly liberal climate regarding sexually active youth (Brugman, Caron, and Rademakers Citation2010; Schalet Citation2010). Although the Netherlands is seen as a progressive country in the area of LGBT rights and gender equality, heteronormativity and the sexual double standard regarding behaviour of women and men still prevail (Emmerink et al. Citation2015; Van Lisdonk, Nencel, and Keuzenkamp Citation2017). In addition, young people have to navigate multiple normative spaces at home, at school and among peers, both on and offline. Religious and ethnic cultural groups in the Netherlands espouse divergent discourses on sexuality (Cense Citation2014; Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2017; Ganzevoort, van der Laan, and Olsman Citation2011), and different notions of young people’s sexual agency coexist, in line with these differing secular and religious beliefs. The Netherlands is in fact home to many different ‘sexual cultures’: discernible assemblages of meanings, conceptualisations and practices about sex, which are held, shared, lived, communicated, negotiated and even contested within a community (Mukoro Citation2017). In contemporary public debate, religious and cultural Otherness is often presented as incompatible with the values of the Dutch secular societal order (Buitelaar Citation2010; Mepschen and Duyvendak Citation2012). Ideas about sexual freedom, sexual diversity and gender equality advanced by politicians and the media, serve to promote the superiority of Western civilisation and often frame migrants from Muslim-majority countries as outsiders and a threat to ‘Western values’. Such public debate affects the intimate and sexual negotiations of young people, especially young people of migrant background.

The research projects

This paper draws on findings from four separate qualitative studies conducted among different groups of young people, exploring how they exercised agency and negotiated the meaning of their sexual identities, desires and practices in a context of changing discourses on sexuality and gender roles. shows the focus of the four studies and the characteristics of each separate research group.

Table 1. Characteristics of the four studies.

The first study took place in 2010 among young Dutch women and men, aged 16 to 21, from a diversity of ethnic backgrounds. The study aimed to understand the strategic negotiation of sexual boundaries in intimate relationships (Cense, Bay-Cheng, and Van Dijk Citation2018). The second study took place in 2012 among ethnic minority youth (aged 12 to 22) in the Netherlands and aimed to explore the sexual discourses they used and the way they negotiated their choices and identities within these discourses (Cense Citation2014). The third study, conducted in 2013, involved young bicultural gay, lesbian and bisexual youth, aged 21 to 30, and explored their agency in navigating their identities (Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2017). The fourth study took place in 2015 and focused on teenage pregnancy. It explored how young women aged 17 to 25, confronted with an unintended pregnancy, positioned themselves within different discourses and how they exercised narrative agency (Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2018).

Although the four studies focused on different subjects and involved different groups of young people, they all shared the goal of learning more about the way young people negotiate their choices as (sexual) agents and about the strategies used to deal with conflicting discourses and social norms. Understanding the way in which gender, sexual, cultural and religious minorities navigate sexual discourses is particularly valuable in reflecting on young people’s agency, as the messages of the dominant culture and the sexuality education that is shaped by this culture (e.g. the stress given to free choice and autonomous decision making), will often not fit with their lived realities.

This article focuses on young people aged 16 to 30. One of the above studies included younger participants (aged 12 to 22), but for the current article the experiences of those aged 16 and older are most relevant. This is the group that fully encounters the challenge of negotiating their sexual identities, practices and stories within particular socio-cultural and relational environments. In Dutch society, young people from the age of 16 and above are seen as sexual subjects, capable of making choices and having sexual agency, whereas children below 16 are not. However, this view of adolescents as sexual subjects is not shared by every Dutch citizen, as suggested above. For the purpose of the analysis presented here, the frictions between the different social worlds that young people have to navigate provide valuable insights into the agentic strategies adopted.

Each of the studies focused on was conducted within a social-constructionist framework and used a life history approach to look at meanings of sexuality in the context of young people’s lives. Life histories are an effective method for eliciting details about subjective experience (Plummer Citation2001). Narratives of personal experience are the stories that people tell that allow them to make sense of events, create order, contain emotions and establish connection with others, particularly when describing difficult times in their lives (Mann et al. Citation2015). Young people are capable of constructing their own life stories, grounded in ‘historically evolving communities of memory, structured through class, age, race, gender and sexual preference’ (Plummer Citation1995, 23). In telling stories, people are not completely free to make up their own account, they must always draw on culturally and historically available narratives (Plummer Citation1995). Indeed, an interview can be seen as an occasion for more systematic reflection and storytelling about the world (Plummer Citation1995).

During the interviews conducted as part of the first, the second and the fourth study, participants were invited to draw their ‘lifeline’, with their age on the horizontal axis and the ‘level of happiness’ vertically. Lifeline development of this kind is a narrative technique for marking and validating life events as a starting point to explore the meaning of experiences. In the third study, participants were invited to draw an ´identity circle´ and include all the different identities the participant felt connected with, as a starting point for exploring the meaning of each identity and possible conflicts between different identities.

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed, coded and analysed using an inductive thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), a thematic narrative analytical technique that focuses on the kinds of stories produced in the data (Riessman Citation1993). We looked for normative discourses that were present in the stories, how participants navigated these discourses and the meaning they gave to their experiences of relationships and sexuality, their sexual identities and desires. In this paper I aim to develop a theory of sexual agency. I will illustrate the theory using excerpts from interviews in the four studies. The excerpts were chosen because they exemplify phenomena that were shared by many participants in each study.

Four components of sexual agency

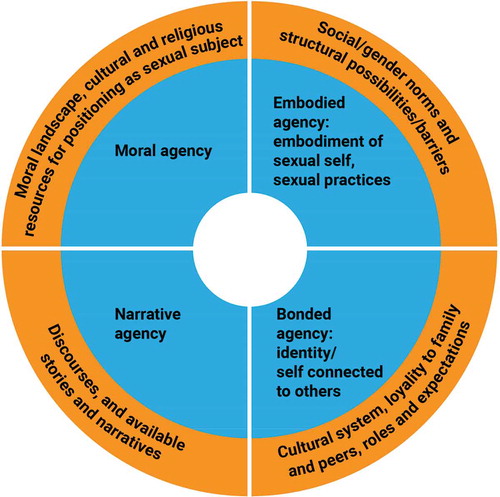

Drawing on this fieldwork and the conceptualisations offered by scholars such as Bell (Citation2012), Phạm (Citation2013), Benhabib (Citation1999), and Tolman, Bowman, and Fahs (Citation2014), I advance a definition of sexual agency that includes four different, interrelated components: (1) embodied agency; (2) bonded agency; (3) narrative agency, and (4) moral agency. Below, each of these four components is explored, using the narratives provided by young people. Each component has its own link to the broader social context (see ), and the interaction between the different components of agency and the social context is crucial to understanding the strategic negotiations engaged with by young people.

Negotiating subjectivity in a normative landscape: embodied agency

The first type of sexual agency I distinguish is embodied agency, or the processes whereby young people engage in sexual practices and develop sexual subjectivities and position themselves in relation to the concepts of sexual identity, desire and practice made available to them by the context and culture in which they live.

The life stories of young people show how they develop their subjectivity and their sense of self by engaging in sexual practices, comparing themselves to others and evaluating their experiences in relation to the concepts they are offered. Reflecting on their sexual practices, young people may embrace or distance themselves from social norms and dominant stories. One of the subjects much debated among peers is that of sexual debut. Shirley (Surinamese-Dutch, 18) reflected:

Everyone had already done it and they said to me, it is so wonderful, believe me. But it wasn’t so great at all. I was a little numb, to be honest. And I was afraid because it went so fast. I wanted to take it easy.

Shirley’s account showed that her disappointment in her sexual debut was connected to her embodied experience, but even more to the expectations the stories of her peers raised. Often the stories young people told about their sexual experiences reflected social norms and expectations. Rarely did young people highlight the physical aspects of their experiences, more often they reflected on its emotional and social aspects. This may reflect the impact of a discourse that discourages viewing sexuality (especially female sexuality) as a bodily experience (Gavey Citation2005; Holland et al. Citation1998). It may also indicate how young people want to distance their experiences from the sexualised mass media culture around them, and reclaim them selves as emotionally valuable and special. As Leroy (Surinamese-Dutch, 16) stated: ‘I was in love. I felt very positive about my first [experience of] intercourse. Because I had felt so many feelings. It was not just sex’. However, the accounts of young people also illuminate that the evaluation of sexual encounters is not always limited to the actual experience with another person but is also heavily influenced by the way others perceived what happened – or did not happen. As Jason (White Dutch, 21) explained:

There were people around me who said, have you done her yet, you know, have you got laid yet? And I said, “yes, of course I’ve got laid, of course”. So, you start talking tough, but you haven’t done anything. And then you have to act, because otherwise you get the reputation of a guy who is all talk and no action.

Like Jason, many other young people described the gendered social norms that scripted their behaviour. While young men were presumed to be exclusively focused on their own desires and on one objective (sex), young women had to balance multiple obligations and objectives. The study on sexual boundaries and sexual coercion (Cense, Bay-Cheng, and Van Dijk Citation2018) showed a clear link between gendered social norms and the negotiations of sexual boundaries. Many young women indica feeling responsible for setting boundaries but also for maintaining a good relationship. Other women drew on discourses of autonomy and framed their behaviour in terms of self-control and self-determination. They actively used these ideals of personal liberty and free choice to reject gendered moralist sanctions, echoing Bay-Cheng’s (Citation2015) findings of how young women have to prove that they are ‘free agents’ by claiming agency over their sexual choices. Sexually abstinent women used this claim to agentic self-determination as well, but to rebut condescending depictions of themselves as mindlessly obedient. Miryam (Moroccan- Dutch, 17), for example, said, ‘Virginity is just an honour. It’s just an honour for yourself’. Unlike young women, whose primary challenge is to stake their claim to being sexual agents, young men’s sexual agency is taken for granted. The deviations from traditional gendered sexual norms among the young men consisted mainly of prioritising reciprocity during sexual interactions with their partners. Seen through this lens, it is apparent that embodied agency is infused with social norms and gender prescriptions.

Young people’s life stories also illuminate how sexual experiences constitute self-knowledge and knowledge about the social context – through the body itself. After her first and rather disappointing one-night stand, Chantal (White Dutch, 17) knew: ‘I have found out that one night stands are not the thing for me. I just need sex with love.’ A clear account of the way the body generates knowledge was given by Rachel (White Dutch, 24, pregnant at 18), who was struggling to position herself anew after terminating an unintended pregnancy:

I will never forget how it felt to be pregnant. The people in the clinic did not respond to that. They just checked if I wanted the abortion. But who really wants an abortion? I knew it had to happen, but somewhere, deep down, I felt I had to protect something. That it did not make sense to get rid of it. It was in a way like the experience of unwanted sex with my first boyfriend. It was both intrusive and not my initiative. It was the same feeling that I had no choice. It just had to happen. I was not in control. But I blamed myself for that, for not being in control. I thought it was entirely my fault. But now I feel I couldn’t have acted differently, not then, not in that context.

Negotiating social roles and expectations: bonded agency

The second type of agency I distinguish in young people’s lifestories is that of bonded agency: in the form of strategies, actions and negotiations involved in maintaining relationships and navigating broader social expectations. Talking about their experiences and the choices they made, many young people described the manoeuvres they undertook to guarantee social support. Their stories illuminate their awareness of the impact of their actions on their families. Yildiz (Turkish-Dutch, 18) expressed how she felt she had to follow the rules of her mother as she could not bear to disappoint her. She expressed how the pressure to give in to the expectations had grown.

My mother feels life is about getting married and having children; having a career is not important for girls. But nowadays life is different; a woman can have her dreams too. But well … my nieces got married and of course I start wondering whether I should marry too. If you hear it all the time at home, it gets to you. I really feel I have to marry soon, or she will stop seeing me as a good daughter. My mother herself married at a young age. She wants me to follow the same path, which means marrying a good man who can look after me and who shares our religion.

Yildiz’s account clearly reveals the clash between a multitude of personal desires (not hurting her parents, being a good daughter, having her parents close by, and having dreams of her own) and interpersonal dynamics (nieces who get married, pressure from her mother). Although minority ethnic youth more openly stressed the importance of their parents’ expectations in the studies, White Dutch youth also indicated how they wanted to meet the expectations of their parents. Annet (19): ‘I wouldn’t want to disappoint my parents, I would really find it awful to have to announce out of the blue that I was pregnant’. Young people described the reciprocity of bonded agency between themselves and their parents. As Layla (Moroccan-Dutch, 19) put it,

I have more freedom than my Moroccan peers, even girls that are older than me. Sometimes they react like “are you allowed to do that?”. Yes, I am. I think my parents trust me, and because of that I will do my best not to harm that trust.

Young people showed creativity in combining elements of different social worlds, for instance by adhering to religious rules while at the same time claiming gender equality as fundamental aspect of their religion. In so doing, they exercised bonded agency in such a way that they could navigate the expectations of different people in different places. Layla for instance adopted several elements of the religion and culture of her parents, but not all:

My headscarf is my own choice; my sisters don’t wear it, only one of them. So, it is about what I want. My parents asked, ‘Do you really want [to do] it? Then you have to go for it’. To be quite honest, I do not attach much value to culture, but I do value religion. Culture is about traditional things. I feel like, ‘What does that have to do with me?’

Connectedness to different sexual cultures can enable young people to navigate a course between hegemonic and minority cultural norms by granting access to diverse perspectives to draw upon and react against.

Being attracted to people of the same sex constitutes a major challenge for young people with migrant backgrounds, requiring them to navigate the cultural norms of family loyalty and a taboo on homosexuality on the one hand while living as a member of a minority ethnic group in the Netherlands on the other. As a result, their sexual identities and modes of sexual expression do not only affect their own social position but also their parents’. Fidan, a Turkish-Dutch woman (29) who was an advocate for LGBT rights stated: ‘I am very conscious that by giving an interview on television it is not just me coming out of the closet, but my whole family’.

Several participants used subtle strategies simultaneously to show loyalty and explore their own sexuality, by keeping their sexuality hidden from their family. Sometimes moving from a village to a town or migration to the Netherlands itself was part of such a subtle strategy. The broader social context and the positioning as a cultural minority also demands creative strategies on the part of young people who need to negotiate their bondedness both to their cultural community and to the wider Dutch society. The account of Mubashir, a Dutch Pakistani gay man (29) clearly showed how such intersecting inequalities work out:

For myself it was not a problem to be attracted to boys. No. But it was… so to speak quite inconvenient for my family. So I felt, why me? I am having a hard time being a minority already, Pakistani, Muslim, I don’t want to be a triple minority. (..) Look, I may consider myself super Dutch, but other people always see [me as] a coloured guy.

Participants in the study of young bicultural gay, lesbian and bisexual youth (Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2017) described how they navigated the different contexts of their cultural community and Dutch society by rejecting a Dutch ‘out and proud’ approach and embracing instead the more subtle treatment of homosexuality within their own community. As Usha (Surinamese-Dutch, 29) stated:

I think it’s pretty Dutch to go fight for your rights. I actually find it a very good thing that you do have a bit of that grey area. We don’t need to raise the rainbow flag to show what we really are.

By distancing herself from the ‘Dutch way’, Usha claimed that her way of embodying a non-heterosexual identity did not harm her cultural identity.

Negotiating a story of one’s own: narrative agency

The third component is that of narrative agency or the capacity to weave a life story that makes sense to the individual self. Narrative agency consists of the accounts young people give of themselves and others about their choices and their lives. In the research studies focused on here, young people constructed their own life stories, grounded in ‘historically evolving communities of memory, structured through class, age, race, gender and sexual preference’ (Plummer Citation1995, 23). The concept of ‘storyscape’Footnote1 offers a useful lens with which to analyse the stories young people can draw on. Young people are immersed in multiple storyscapes, defined by different and often contrasting audiences. Within these storyscapes, young people have to negotiate their own story. Especially when their story is not a mainstream account, it may take narrative power and creativity to legitimate the choices displayed within it. Amuun (Somalian-Dutch, 25) described how her story evolved when her self-acceptance grew:

We grow up in a ‘we-culture’. It’s all about family. If you take a decision you have to put the interest of the family first. In the Netherlands it is the other way round; children have to think for themselves, choose for themselves. But with us, you will be called egoistic, spoiled, westernised. I have this struggle myself. Family means a lot to me. You have to learn to think for yourself. When you start coming out, you feel your sexuality is the world. You think, I’m gay and that’s it. After a while, when you have accepted yourself, you may see that your sexuality is just part of who you are.

In the study of teenage pregnancies (Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2018), the narrative agency of young women was complicated by the existence of dominant negative accounts of teenage pregnancy in terms of victimhood, failure, irresponsible behaviour and guilt. However, the momentum of teenage pregnancy also offered agentic possibilities to young women to take up a new stance towards their parents and boyfriends. Deborah (25, White Dutch, first pregnant at 18) had given birth at 18 because there were no other options imaginable in her Christian family. However, when she unintentionally became pregnant again, there were other stories available:

I immediately felt, ‘how am I going to confront my parents with this? I do not want to experience all this again.’ I was busy with my education and I really felt, ‘I can’t handle this.’ So although my boyfriend did not agree, I had an abortion. My parents still do not know. They would find it horrible if they ever found out. My boyfriend and I had a lot of conflicts over it, but well, in the end it was me who had to choose as it was in my body. It was a hard decision to make, as I am a Christian myself. I was afraid I would regret it later. But when I look back now, I feel sorry but I also feel it was the right thing to do for me then.

One of the narrative challenges for young women lies in negotiating stories of subordination of women, female vulnerability, and dependency as well as stories of responsibility and individual agency. Another constraining factor is the taboo and silencing of sexuality, which disempowers young women in their relationships. The life stories of pregnant teenagers show that the individualistic concept of reproductive choice does not adequately engage with the complex and contextualised way in which young women negotiate the meaning of their pregnancy amidst the limitations of the available stories.

Negotiating the right choice: moral agency

The fourth component I distinguish in the data is one of moral agency or the reflection upon and positioning of oneself within moral frameworks. This moral positioning is connected to feeling responsible for not hurting or bringing shame on others such as their family. As Canan (Turkish-Dutch, 19) in the study of minority ethnic youth put it:

When you are in love, you like each other and you want to touch each other. But it is not allowed, so you feel very bad about yourself. In my family, it is emphasised again and again, be aware, watch yourself, and think about your honour and the community and the shame. So, I just cannot be intimate with somebody.

In strategic negotiations of the meaning of teenage pregnancy and the decision-making around it, young women also had to navigate the opinions of their family and (boy)friends, and the social discourses that problematise teenage pregnancy, abortion and teenage motherhood. Participants’ narratives drew on different concepts of responsibility for their decision-making, whether they took the path of continuing or terminating the pregnancy. In their reflections on making the right choice, three moral discourses could be distinguished: the conviction that children are a gift (and therefore abortion is immoral); the belief that children have the right to grow up in good conditions (and therefore parenthood is in some cases immoral); and the idea that one must be able to look after oneself before becoming a parent. Sometimes the moral judgment whether a choice was the right choice changed over time, because circumstances changed. This was the case for Robijn (White Dutch, 19) who, had an abortion at the age of 17):

I was thinking for half a year, ‘what did I do?’ I was thinking how old the child would have been, if I had kept it. But now I think, well, I finished my exams. And our relationship broke up. It would not have worked. I can see that now. And I am glad to know that now, looking back, it was the right thing to do.

However, some women also expressed resistance to the responsibility deriving from liberal agentic ideals and sought out other moral standards. They included Tessa (Surinamese-Dutch, 21), who stated:

You can never control your own life. You can put some effort into getting it the way you want it, but you cannot determine it. I don’t feel that would be right either. Everything happens for a reason. Like the twins: I first had an abortion and then I became pregnant again and got twins. That is just… not a coincidence….

Discussion

In this paper, I have outlined a multicomponent model for sexual agency that connects individual choices to the social, cultural, moral and narrative contexts that young people have to navigate. In the process of exploring their sexual identities, desires and relationships, young people are guided by and confronted with social, gendered norms and available stories. However, their bodily experiences generate knowledge as well, echoing Tolman’s (Citation2012) findings that the body constitutes a form of knowledge about the self, one’s relationships and one’s social world.

The life stories of the young people whose accounts are presented here show how sexual agency is forged and expressed within context and is manifested through individuals’ responsiveness to others. The connectedness of young people to families, friends and communities (bonded agency) interacts with the processes whereby they develop sexual subjectivities and position themselves in relation to concepts of sexual identity, desire and practices (embodied agency). Moreover, young people’s accounts also reveal how they navigate different normative landscapes while developing their sexual selves and engaging in sexual practices, and how they develop moral and narrative agency within these processes.

The four different components of sexual agency described here are intertwined and deeply influence each other. Young people develop a life story by reflecting on their embodied experiences and the perceived ‘reality’ around them. The opposite process, by which young people become involved in sexual practices and turn a narrative into a behavioural, embodied reality, is equally important. Moral agency is closely linked to the experienced connectedness to others, but also to the stories young people can construct about their choices and to their practices, their embodied agency.

Developing one’s sexual self, including the four components of sexual agency, within diverse social, cultural, narrative and moral landscapes is challenging for all young people, but not to the same extent for everyone. The road is bumpier for young people deviating from cultural ‘normalcy’, for instance by being non-heterosexual, gender fluid or transgender, or by not conforming to the cultural ideas of being a ‘good girl’ or a ‘real man’. Running into trouble, by having an unintended pregnancy or by experiencing sexual victimisation, may also cause major friction in claiming embodied, bonded, narrative and moral agency. On the other hand, as the study of teenage pregnancy (Cense and Ganzevoort Citation2018) showed, experiencing obstacles and troubles may also be a turning point in one’s life, leading to the taking up of another social position and a strengthening of the agentic power of young people. This resonates with Mahmood’s argument that agency can be understood as a capacity for action that specific relations of subordination enable and create.

Limitations

Some limitations of the research studies drawn upon here are worth noting. As each of the studies was conducted with Dutch Youth, the theory deriving from them is located in the sociocultural context of the Netherlands. To explore the value of the model in other sociocultural settings, it needs to be compared to the life stories and strategies of young people living in countries with different ideologies regarding gender and youth sexuality, and in other cultural climates. However, the diverse ethnic/cultural backgrounds of the participants in the four studies do reflect the multitude of ways in which young people mediate and embody different aspects of the cultures they inhabit. Moreover, the sexual diversity of the young people involved in the studies contributed to the quality of the analysis, as life stories from a variety of perspectives were included. On balance, therefore, the model may be applicable to other countries and areas with culturally diverse populations.

Another limitation derives from the fact that interviews are always social interactions between an interviewer and a participant during which some stories can be told while others are not possible. As the dominant cultural logic celebrates choice and autonomy, it is more favourable to telling of stories in which the narrator has some form of control, rather than the expression of victimisation and powerlessness. On the other hand, the ‘outsider’ position of the interviewer may have encouraged participants to share stories they did not dare to reveal to family members or friends. In addition, the interviewer may have probed for stories by asking questions, the participant has not reflected on before. Although not all stories were able to be told, analysis of the four different studies revealed a number of repeated themes in the narratives provided by young people.

Concluding comments

The analysis of sexual agency offered in this paper – as a complex and subtle process of navigation between competing expectations, discourses and cultural influences – should have consequences for sexuality education. A sole focus on autonomy, assertiveness and making one’s own free choices does not suffice, as it does not recognise and match the realities of young people. Too great a cultural emphasis on individual responsibility obscures the mutual responsibility between partners, and the impact of structural limitations and inequalities. The concept of choice is itself problematic. Although young people may mobilise narratives of choice and personal autonomy to articulate and make sense of their actions after the event (Harris and Dobson Citation2015), and may even argue that each individual is solely responsible for his or her own wellbeing (Lamb and Randazzo Citation2016), this does not mean that they are entirely responsible for what happens in their lives, or that they all have the required power, possibilities and positions to make ‘free’ choices. The challenge for sexuality educators is to move beyond the restrictive paradigms offered by individual responsibility to acknowledge young peoples’ ongoing negotiations of social expectations, boundaries and bondedness. This acknowledgment forms the point of departure for the development of new forms of sexuality education that question social norms, promotes critical awareness and support young people in their journey along the bumpy road to developing their gendered and sexual selves (Cense Citationin press).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. A ‘storyscape’ comprises the surrounding landscape of interconnected stories with which we inevitably interact (Ganzevoort Citation2017).

References

- Armstrong, E. A., L. T. Hamilton, E. M. Armstrong, and J. Lotus Seeley. 2014. “‘Good Girls’: Gender, Social Class, and Slut Discourse on Campus.” Social Psychology Quarterly 77: 100–122.

- Attwood, F. 2007. “Sluts and Riot Grrrls: Female Identity and Sexual Agency.” Journal of Gender Studies 16 (3): 233–247.

- Barcelos, C. A., and A. C. Gubrium. 2014. “Reproducing Stories: Strategic Narratives of Teen Pregnancy and Motherhood.” Social Problems 61 (3): 466–481.

- Bay-Cheng, L. Y. 2015. “The Agency Line: A Neoliberal Metric for Appraising Young Women’s Sexuality.” Sex Roles 73: 279–291.

- Bell, S. A. 2012. “Young People and Sexual Agency in Rural Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 14 (3): 283–296.

- Benhabib, S. 1999. “Sexual Difference and Collective Identities: The New Global Constellation.” Signs 24 (2): 335‐361.

- Bettie, J. 2003. Women without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3:: 77–101.

- Brown, W. 2003. “Neo-Liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy.” Theory and Event 7: 1–19.

- Brugman, M., S. L. Caron, and J. Rademakers. 2010. “Emerging Adolescent Sexuality: A Comparison of American and Dutch College Women’s Experiences.” International Journal of Sexual Health 22 (1): 32–46.

- Bryant, J., and T. Schofield. 2007. “Feminine Sexual Subjectivities: Bodies, Agency and Life History.” Sexualities 10 (3): 321–340.

- Buitelaar, M. 2010. “Muslim Women´S Narratives on Religious Identification in a Polarizing Dutch Society.” In Muslim Societies and the Challenge of Secularization: An Interdisciplinary Approach, edited by G. Marranci, 165–184. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Carmody, M., and G. Ovenden. 2013. “Putting Ethical Sex into Practice: Sexual Negotiation, Gender and Citizenship in the Lives of Young Women and Men.” Journal of Youth Studies 16: 792–807.

- Cense, M. 2014. “Sexual Discourses and Strategies among Minority Ethnic Youth in the Netherlands.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16: 835–849.

- Cense, M. 2018. “Navigating a Bumpy Road. Developing Sexuality Education that Supports Young People’s Sexual Agency.” Sex Education. doi:10.1082/14681811.2018/1537910.

- Cense, M., L. Y. Bay-Cheng, andL. Van Dijk. 2018. “‘Do I Score Points if I Say No?’ Negotiating Sexual Boundaries in a Changing Normative Landscape.” Journal of Gender-Based Violence 2 (2): 277–291.

- Cense, M., and R. R. Ganzevoort. 2017. “Navigating Identities: Subtle and Public Agency of Bicultural Gay Youth.” Journal of Homosexuality 64: 654–670.

- Cense, M., and R. R. Ganzevoort. 2018. “The Storyscapes of Teenage Pregnancy. On Morality, Embodiment, and Narrative Agency.” Journal of Youth Studies. doi:10.1080/13676261.2018.1526373.

- Emmerink, P. M. J., I. Vanwesenbeeck, R. J. J. M. van den Eijnden, and T. T. Bogt. 2015. “Psychosexual Correlates of Sexual Double Standard Endorsement in Adolescent Sexuality.” Journal of Sex Research 53: 286–297.

- Ganzevoort, R. R. 2017. “Naviguer dans les récits. Négociation des histoires canoniques dans la construction de l’identité religieuse.” In Récit de soi et narrativité dans la construction de l’identité religieuse, edited by P.-Y. Brandt, P. Jesus, and P. Roman, 45–62. Paris: Éditions des archives contemporaines.

- Ganzevoort, R. R., M. van der Laan, and E. Olsman. 2011. “Growing up Gay and Religious. Conflict, Dialogue, and Religious Identity Strategies.” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 14: 209–222.

- Gavey, N. 2005. Just Sex? the Cultural Scaffolding of Rape. London: Routledge.

- Harris, A., and A. S. Dobson. 2015. “Theorizing Agency in Postgirlpower Times.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 29 (2): 145–156.

- Holland, J., C. Zanoglu, S. Sharpe, and R. Thomson. 1998. The Male in the Head: Young People, Heterosexuality and Power. London: Tufnell Press.

- Jackson, S. 1996. “Sexual Skirmishes and Feminist Factions: Twenty-Five Years of Debate on Women and Sexuality.” In Feminism and Sexuality a Reader, edited by S. Jackson and S. Scott, 1–31. Edinburgh Edinburgh University Press.

- Lamb, S. 1997. “Sex Education as Moral Education: Teaching for Pleasure, about Fantasy, and against Abuse.” Journal of Moral Education 26 (3): 301–315.

- Lamb, S., and R. Randazzo. 2016. “An Examination of the Effectiveness of a Sexual Ethics Curriculum.” Journal of Moral Education 45 (1): 16–30.

- Lisdonk, J. V., L. Nencel, and S. Keuzenkamp. 2017. “Labeling Same-Sex Sexuality in a Tolerant Society that Values Normality: The Dutch Case.” Journal of Homosexuality 65 (13): 1892–1915.

- Mahmood, S. 2001. “Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent: Some Reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival.” Cultural Anthropology 16 (2): 202–236.

- Mann, E. S., V. Cardona, and C. A. Gómez. 2015. “Beyond the Discourse of Reproductive Choice: Narratives of Pregnancy Resolution among Latina/o Teenage Parents.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (9): 1090–1104.

- Mastro, S., and M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck. 2015. “Let’s Talk Openly about Sex: Sexual Communication, Self-Esteem and Efficacy as Correlates of Sexual Well-Being.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 12 (5): 579–598.

- McNay, L. 2000. Gender and Agency: Reconfiguring the Subject in Feminist and Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Mepschen, P., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2012. “European Sexual Nationalisms: The Culturalization of Citizenship and the Sexual Politics of Belonging and Exclusion.” Perspectives on Europe 42 (1): 70–76.

- Mukoro, J. 2017. “The Need for Culturally Sensitive Sexuality Education in a Pluralised Nigeria: But Which Kind?” Sex Education 17 (5): 498–511.

- Ortiz, R., and A. Shafer. 2017. “Define Your Line: Evaluating a Peer-To-Peer Sexual Consent Education Campaign to Improve Sexual Consent Understanding among Undergraduate Students.” Journal of Adolescent Health 60 (2): 106.

- Phạm, Q. N. 2013. “Enduring Bonds: Politics and Life outside Freedom as Autonomy.” Alternatives 38: 29–48.

- Plummer, K. 1995. Telling Sexual Stories. London: Routledge.

- Plummer, K. 2001. Documents of Life 2: An Invitation to Critical Humanism. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Plummer, K. 2003. Intimate Citizenship: Private Decisions and Public Dialogues. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Prins, B. 2006. “Mothers and Muslima’s, Sisters and Sojourners: The Contested Boundaries of Feminist Citizenship.” In Handbook of Gender and Women’s Studies, edited by K. Davis, M. Evans, and J. Lorber, 234–250. London: SAGE.

- Richardson, D. 2017. “Rethinking Sexual Citizenship.” Sociology 51 (2): 208–224.

- Riessman, C. 1993. Narrative Analysis. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Schaalma H. P., C. Abraham, M. R. Gillmore, and G. Kok. 2004. “Sex Education As Health Promotion: What Does It Take?” Archives of Sexual Behavior 33 (3): 259–269.

- Schalet, A. 2010. “Sexual Subjectivity Revisited: The Significance of Relationships in Dutch and American Girls’ Experiences of Sexuality.” Gender and Society 24 (3): 304–329.

- Shannahan, D. S. 2009. “Sexual Ethics, Marriage, and Sexual Autonomy: The Landscapes for Muslimat and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Muslims.” Contemporary Islam 3: 59–78.

- Stanley, N., J. Ellis, N. Farrelly, S. Hollinghurst, S. Bailey, and S. Downe. 2017. “‘What Matters to Someone Who Matters to Me’: Using Media Campaigns with Young People to Prevent Interpersonal Violence and Abuse.” Health Expectations 20 (4): 648–654.

- Tolman, D. L. 2012. “Female Adolescents, Sexual Empowerment and Desire: A Missing Discourse of Gender Inequity.” Sex Roles 66: 746–757.

- Tolman, D. L., C. P. Bowman, and B. Fahs. 2014. “Sexuality and Embodiment.” In Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology, edited by D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. Pfaus, and M. Ward, 759–804. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books.

- Tolman, D. L., S. M. Anderson, and K. Belmonte. 2015. “Mobilizing Metaphor: Considering Complexities, Contradictions, and Contexts in Adolescent Girls’ and Young Women’s Sexual Agency.” Sex Roles 73: 298–310.