ABSTRACT

Peer education is a widely used strategy in sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR) programmes for young people, yet measurement of its effectiveness often focuses on a narrow set of outcomes. This qualitative study explored how peer education was integrated into the Get Up, Speak Out for Youth Rights! (GUSO) programme in Kisumu and Siaya Counties, Kenya and the contribution it made to measured and unmeasured outcomes. Findings indicate that whilst peer educators were a central part of the GUSO theory of change, the intentionality of design varied between partners and sites, and their contributions were formally measured only in relation to two of five outcome areas. In addition to their contributions to these measured outcomes, the study found that peer educators also contributed to a range of other, unmeasured outcomes related to community support and mobilisation; gender norms; and economic empowerment. Findings show that peer educators may contribute to many unmeasured – and sometimes unexpected – outcomes that go beyond traditional measurement of their contributions. These merit further exploration in the literature and in programming. Programme developers are encouraged to be more intentional in the design and measurement of peer education, ensuring that the breadth of its contribution to programming are recognised.

Introduction

Globally, peer education is a widely-used programmatic intervention for the advancement of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) among young people.Footnote1 Behind its prolific use is the underlying assumption that young people are more likely to accept and take action on information provided by a peer (Siddiqui et al. Citation2020). Despite great diversity in the design, implementation and quality of peer education interventions, commonly-used measurements of its effectiveness focus primarily on its contribution to a small set of outcomes related to SRHR knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. Moreover, measuring the direct contribution of peer education is notoriously challenging in the context of multicomponent programming, given that peer educators may work within and across various programme elements to create synergies (Billowitz et al. Citation2020). These and other challenges in measuring effectiveness have led to a questioning of whether peer education actually works (Chandra-Mouli, Lane, and Wong Citation2015).

This study was commissioned by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), together with the Kenya SRHR Alliance members, and Rutgers. There were two phases to the work. Phase 1, which included a literature review and in-depth interviews with peer educators and implementing organisations internationally aimed to identify future research priorities for the sector in relation to peer education; one such research priority being to better understand the contributions of peer education to multicomponent SRHR programming (Billowitz et al. Citation2020). This became the focus for Phase 2 of the study, the findings of which are the subject of this paper. This element of work explored the measured and unmeasured contributions of peer education to the Get Up, Speak Out for youth Rights! (GUSO) programme in Kenya. The following research questions guided the study, as well as the analysis and presentation of findings.

How was peer education integrated into the GUSO programme’s design?

How were peer education’s contributions measured?

How did peer education contribute to the GUSO programme’s outcome areas?

How did peer education contribute to other outcomes?

Background

Youth peer education is an umbrella term used to refer to a multitude of actions and interventions through which young people reach other young people with information, education and services. It is used both as a way to facilitate better health and rights outcomes for young people, as well as a way of empowering young people to take action within their peer groups and communities. More often than not within SRHR interventions, peer education forms part of a multi-component programme – meaning that it is one of several components employed to achieve the programme’s desired result[s]. It may be utilised alongside or built into inter alia SRH service provision, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE), community mobilisation, and/or advocacy (Billowitz et al. Citation2020).

Regardless of the specific programmatic design, existing evidence points to the importance of intentionality in the implementation of peer education. To date, most studies conducted on peer education’s effectiveness have not examined quality of peer recruitment, training and support, and compensation nor whether those activities were suitable to achieve a programme’s intended outcomes (Billowitz et al. Citation2020).

Historically, much SRHR programming has focused on effecting chang in the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of programme participants. The contribution of peer education is often measured solely or primarily in relation to these outcomes, and the evidence of effectiveness in this regard is mixed (see Tolli Citation2012; Siddiqui et al. Citation2020; Billowitz et al. Citation2020). In contrast, evidence from implementers and peer educators themselves illustrates that there is much greater depth and breadth to peer educators’ contributions than is currently documented (Billowitz et al. Citation2020). Grey literature from a variety of implementing organisations illustrates that outcomes can and have been achieved by peer education in relation to other factors, including strengthened social networks for young people, safe spaces for young women/girls, and gender equality. These outcomes often go unmeasured and unreported on in the peer reviewed literature (Billowitz et al. Citation2020).

Methodology

Design

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study that explored the contributions of peer education to the GUSO programme in Kenya. The study used in-depth interviews with (adult) project stakeholders and peer educators and focus group discussions with participants of peer education activities. Additionally, a desk review of GUSO programme documents was conducted.

Study sites and partners

The study was conducted in Kisumu and Siaya Counties in Kenya. Baseline, midline and endline programme evaluations had beenconducted in Siaya County; owing to this, this largely rural county was selected as a study site for this assessment. Kisumu County, a city county, was also chosen because of its proximity to Siaya and to provide useful contrast.

Three of project’s implementing partners (Anglican Development Services [ADS-Nyanza], Kisumu Medical Trust [KMET] and Tropical Institute of Community Health and Development [TICH]) worked in Kisumu and Siaya Counties. They had a number of peer educators who were still active in their respective communities at the time of this study, in December 2020 and early January 2021. As part of GUSO, ADS-Nyanza and TICH peer educators provided SRH information and education to young people with linkage to services in Kisumu and Siaya Counties, respectively. KMET peer educators provided information alongside SRH services in both counties. Our study was, however, conducted towards the end of the GUSO programme after almost a year of a drastically reduced level of programme implementation due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Study populations

The study included three study populations: peer educators aged 18–24 years; peer education participants aged 18–24 years; and adult stakeholders involved in the GUSO programme including programme managers, county health officials and health professionals. All participants were purposively sampled and interviewed. A total of 24 (12 female and 12 male) peer educators were interviewed. Of these, 16 provided SRH information and education while 8 were based at health facilities providing support for SRH services. Additionally, 14 interviews were conducted with adult stakeholders in the two study sites (seven from each study site). A total of 4 FGDs with 28 young programme participants (20 female and 8 male) were also conducted (two each in each of the two study sites), one with participants who had received SRH information and education, and the other with those who had received SRH services (see ). In total, 66 respondents participated in the study.

Table 1. Study participants’ details.

The study recruited peer educators who were actively engaged in peer education activities in 2019 and who had solid knowledge and experience of the GUSO programme. Additionally, participants had to be reachable on a mobile phone during the day. GUSO programme stakeholders shared their perceptions of the contributions of peer education to the programme and the wider communities within which they worked. At community level, young male and female programme participants active in the year preceding the study were selected to participate infocus group discussions.

Desk review

A desk review primarily focused on the GUSO programme documents from the five years of its implementation. The documents were sourced from the Kenya SRH Alliance and the GUSO consortium. Programme annual reports, log frames, proposals, evaluation reports and other relevant documents covering the five years of GUSO implementation were reviewed. Analysis focused on extracting information relevant to the research questions, including information relevant to peer educators’ contributions to GUSO outcome areas and other, unmeasured outcomes.

Data collection

Open ended and semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus group discussion guides were developed with additional probes. The questions were structured in two sections: 1) peer education’s contribution to the programme’s outcome areas; 2) peer education’s contribution to other, unanticipated and/or unmeasured results. Interviews with peer educators and focus group discussions with participants were conducted in person by one of the authors not involved with implementation of the GUSO programme. Interviews with adult stakeholders were conducted via Zoom by HE, KW and MB. Comprehensive notes were taken during all the interviews and cleaned by the authors after the interviews. Each interview and/or discussion lasted between 50 minutes and 90 minutes.

Study ethics

The study received ethical approval (AMREF-ESRC P896-2020) from AMREF’s Ethics and Scientific Review committee before the commencement of data collection activities. Study participants received information about the study before providing oral and/or written consent. Following the interviews and discussions, each participant and FGD was given a unique code used during analysis to ensure anonymity and reduce bias. Identifying information about each participant was kept in a separate ‘key file.’

Data analysis

Based on the data collected, inductive theme identification was done to generate codes, and an analytical framework was created in Excel. Three of the authors (KW, MB, HE) undertook a thematic analysis following a six step process advocated by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). An initial sample of interviews was analysed by each author, after which the original code list was amended. Through discussion and consensus building, the authors iteratively refined the themes together with the remaining authors to arrive at those reported here.

Programme design

Theory of change

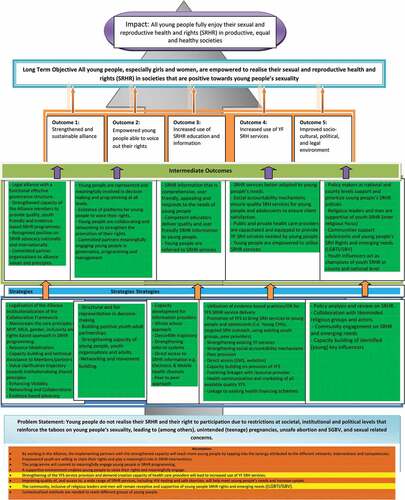

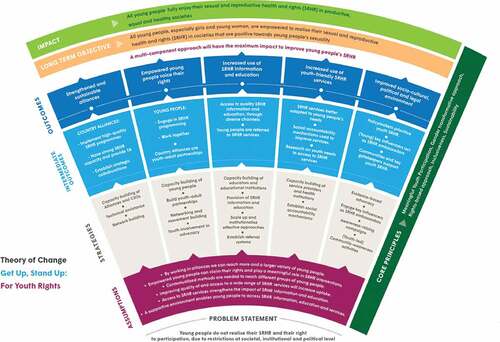

The GUSO programmeFootnote2 was a five-year (2016–2020) multi-component youth SRHR programme funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and managed by the GUSO ConsortiumFootnote3 in seven countries.Footnote4 The long-term objective of the programme was for ‘all young people, especially girls and young women, to be empowered to realise their SRHR in societies that are positive towards their sexuality’ whilst impact was articulated as: ‘all young people fully enjoy their sexual and reproductive health and rights in productive, equal and healthy societies’ (GUSO Kenya Citation2021).

In Kenya, the programme was implemented in six counties in partnership with ten membersFootnote5 of the Kenya SRHR Alliance.Footnote6 The Kenya GUSO Programme’s theory of change identified five outcomes related to 1) strengthened and sustainable alliance; 2) empowered young people able to voice out their rights; 3) increased use of SRHR education and information; 4) increased use of youth friendly sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services and 5) improved socio-cultural, political and legal environment (see ).

Measurement framework

One of the GUSO programme’s core assumptions was that young people, including peer educators, can play an integral role across all areas of multi-component SRHR programming. Despite this, the GUSO programme’s documentation revealed that peer educators’ roles and responsibilities – and related measurements of their contributions – focused almost entirely on two of the five outcome areas: the increased use of SRHR education/information (outcome area 3) and increased use of SRH services by young people (outcome area 4).

With regards to measurement, output indicators provided the basis for ongoing data collection and reporting by all implementing partners in relation to outcome areas 3 and 4. The indicators used did not identify the unique contributions of peer educators to either of these outcome areas, making it challenging to get a clear picture of their collective contribution to the programme. shows the output indicators and related results.

Table 2. Output indicators for outcome areas 3 and 4Footnote10.

The outcome indicators (see ) were measured only at baseline (2017), midline (2018) and endline (2020). Baseline and endline evaluations were undertaken via a mixed methods study undertaken by the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) of the Netherlands using qualitative research methods in the intervention areas and surveys in both the control and intervention areas. Midline assessment included a systematic mapping of stakeholders in both the intervention and the control areas alongside a Qualitative Impact Assessment (QUIP) in Siaya district (GUSO Citation2018).

Table 3. Outcome indicators for GUSO outcome areas 3 and 4.

Findings

Peer educators – recruitment and support

Recruitment

Two types of peer educators were recruited to the GUSO programme: those who were based in their communities, including schools, whose primary role was to provide SRH information and education to other young people; and youth peer providersFootnote7 who were based in participating health facilities and supported young people’s access to health services.

Recruitment methods varied, with some peer educators being recruited through community leaders, such as chiefs, friends, family or community health workers because they showed one or more desired qualities, including friendliness, leadership skills and/or specific technological abilities. Other peer educators said they thought that they were recruited because they were struggling with issues pertinent to the programme, such as teenage pregnancy or drug use, whilst yet others responded to advertisements. Some participated in an interview process while others did not.

How we recruited was [different] at different levels. Because the peer provider model was new, we wanted to leverage a platform that we had. So, we did engage community focal persons who engaged their community health extension workers to help in recruitment. We were able to have peers - or boys and girls - who were from the geographical surroundings of facilities. We had a pool, and we interviewed some. They understood what kind of volunteer work they got into. We reviewed the pool based on: whether just visiting or full time for at least 1 year; whether they wanted to venture into SRH volunteership [most of them had SRH as a new concept]; and for those who were minors, below 18, we had to ask if their guardians were comfortable. (GUSO staff member, Kisumu)

Gender was only taken into consideration insofar as an equal number of girls and boys were recruited as peer educators. Recruitment could therefore be described as gender aware, based on the premise that gender would be important in influencing young people’s receptivity to information and outreach: ‘They were looking for gender equality so that females could talk to females and males to males.’ (Peer educator, Siaya)

Training and support

The amount and content of training and support provided to peer educators varied widely. Twenty-two of the 24 peer educators reported receiving training to some degree; most of the training was geared towards preparing them to provide SRH information, education and/or services to other young people. However, peer educators reported varying training duration, from three days to five weeks. All peer educators reported receiving support in terms of supervision and technical updates during their work.

I was trained for one week and two days additional training as a peer provider at the facility by the facility in-charge. I have also been trained on monitoring and evaluation, youth friendly services and meaningful youth participation. I was trained by KMET on ASRH, community health messaging, and referrals. HIV, STIs, drugs and substance abuse, alcohol abuse, referral channels, and comprehensive abortion care. I am supervised by the facility in charge at the facility and by the project officer when we go for outreach. I have received refresher training on the same topics and additionally COVID 19, including how it has affected referrals that young people seek from the community. (Peer educator, Kisumu)

[We received training for] five weeks [on] how to control HIV/AIDS/ contraceptives/use of condoms and setting personal goals. (Peer educator, Siaya)

The topics covered in training also varied widely, with contraception and HIV prevention being the most commonly cited; menstrual hygiene, gender-based violence, and substance abuse and other topics were mentioned by a few peer educators. Many described being trained in how to conduct outreach work, speak to other young people effectively, and provide referrals to SRH services. All the peer providers and some community-based peer educators also received training in service provision – primarily counselling on issues such as contraception and pregnancy, HIV testing and counselling, and mental health.

Just over half of all the peer educators mentioned receiving refresher training or content related ‘updates’ throughout the time with the programme. Most peer educators described receiving a significant amount of supervision and support from the organisation with which they worked, including monthly meetings with supervisors in some cases. Those working in health facilities were most likely to mention supportive supervision.

Compensation

Compensation of peer educators varied widely. Some reported receiving only travel cost reimbursement, while others received monthly stipends. Some peer educators reported that they received incentives such as t-shirts, caps, notepads and/or pens. In the case of one programme partner, peer educators had been recruited through a separate programme that paid their school fees, and this caused a degree of confusion as to whether their peer education activities were a required activity to continue receiving that benefit. Finally, several stakeholders recognised the importance of compensation of some kind for peer educators to continue to motivate them and ensure their participation:

Motivating peer providers is very important as they are the lifeline of the programme at the community level. They help reach many youths. (Nurse, Siaya)

Peer educator contributions

When asked whether GUSO measurements adequately captured peer educators’ contributions to the programme, no study participants answered affirmatively and many recognised gaps in how peer education was measured. Among other things, study participants wished that there had been data to illustrate peer educators’ contributions to decreasing unsafe abortion; the creation of SRHR related social media content; changes in cultural beliefs; reductions in school dropouts; ensuring commodity availability and avoiding stockouts; reductions in teenage pregnancy; and reductions in parent-child conflict, amongst others.

Access to information and education

Monitoring data reveals that over 7,600 people were trained to provide SRHR education and information to young people in Kenya; however, it is not known how many of these were peer educators (GUSO Kenya Citation2021). Peer educators were trained to provide information and education through a variety of channels, including one-to-one, informal interactions and more formal group sessions in school and at community events.

Every peer educator interviewed stressed the importance of sharing information with other young people, with many seeing this as the most important part of their role. Importantly, peer educators expanded on the reach and content of what they provided, going above and beyond their prescribed roles and responsibilities. For example, many described taking on personal responsibilities for the well-being of young people in their communities. Being seen as a role model and mentor in the community was a badge of honour. Other young people as well as parents and community leaders asked them for advice outside of their ‘working hours’ (FGD4) – tasks that likely went undocumented through the formal reporting channels. Programme participants described being given ‘guidance’ by peer educators to help make informed decisions about life matters (FGD4).

In schools we do group talks based on the ages. We address emerging issues based on questions raised. We form health groups within the schools and the students select a leader of the health group whom we reach [out to] for any updates, especially requirements for more health talks. (Peer educator, Kisumu)

The content of the information provided by peer educators went beyond the SRHR topics included in their training. Much of it could be described as general life coaching or counselling on relationships with parents; teenage behaviour; peer pressure; drug use; friendships; life goals; education and more. One peer educator shared:

I have spoken with teenage mothers on how to take care of themselves, how to relate in community and to their parents to reduce conflicts, addressing issues of unsafe abortion, problems of drug and substance abuse and avoiding bad company.’ (Peer educator, Siaya)

Informing young people about available SRH services was another part of peer educators’ role. Many said that making referrals and/or escorting young people to health facilities was of crucial importance to ensuring that they are able to act on the SRH information received. One peer educator described the linking role that she played between information, services and enabling environment as follows:

‘I help provide a conducive environment for youth to be able to access services. I provide a link for the youth who are referred to the facility and I give basic counselling before services uptake. I provide referrals [and] escorts for young people for health services at the facility’ (Peer educator, Siaya).

Monitoring data indicated that over 615,000 young people were reached with information or education during the five years of the programme, although data on the percentage of these reached by peer educators is not available.

SRH service utilisation and quality assurance

Peer educators helped increasing the utilisation of youth-friendly SRH servicesFootnote8 through community outreach, awareness raising and referrals for young people as well as by directly providing services to young people. They also monitored service quality and participated in formal and informal quality assurance processes.

During community outreach, peer educators’ efforts were focused heavily on raising awareness of the availability of SRH services for young people as well as how youth-friendly the services were. This was needed in order to overcome preconceived ideas amongst young people about the SRH services: ‘The youth used to have a mentality that some nurses were bad … We connect the youth to the health providers who have changed their attitudes towards youth and become more supportive. Youth now feel free to come and get health services at the facility.’ (Peer educator, Siaya)

Some peer educators, such as those working with KMET, were trained as peer providers and were able to provide contraceptive and counselling services to young people themselves. Others simply referred young people to the youth-friendly services in their area. Yet others personally escorted young people to the services, ensuring they knew where to go. Furthermore, many peer educators participated in HIV testing and cervical cancer screening drives in their communities, ensuring the inclusion and participation of young people.

With respect to quality assurance, peer educators provided feedback from young people to service providers that allowed improvements and adjustments to be made . At the health facility level, peer educators were the ‘eyes and ears’ of young people, with many indicating that they made ‘regular visits’ to check on the quality of services provided to young people: ‘We ask about services which are not being provided to the youth and communicate the same to TICH which comes to help and improve the quality and range of services offered’ (Peer educator, Siaya). Another peer educator in Siaya described how he regularly asked health facilities’ staff members how they were providing services to young people, ensuring that they were making use of the dedicated youth room. Two other peer educators mentioned encouraging health providers to be friendly, maintain confidentiality and use polite language when speaking to young people (Siaya). Yet others helped clinics become more ‘attractive’ to youth by planting trees and designating corners or rooms specifically for young people, to make them feel comfortable.

Monitoring data for the GUSO programme reveal that over 3 million direct and indirect SRH services were provided to young people during the five year implementation period across Kenya (GUSO Kenya Citation2021). As with information and education, figures that isolate peer educators’ contributions are not available. The endline evaluation of the GUSO programme in Kenya showed increases in young people’s utilisation of the following services in the implementation areas: male circumcision, child protection, STI testing, counselling for sexual violence, and voluntary counselling and testing for HIV (Kok et al. Citation2021).

Community support

One of the five GUSO outcome areas was ‘improved socio-cultural, political and legal environment’ (for SRHR). The programme did not measure peer educators’ contributions in relation to this outcome. However, this study found that peer educators worked to increase the support and involvement of important stakeholder groups and, as a result, were able to share their ideas more freely.

In particular, peer education increased community support for youth SRHR and support for the provision of SRH information, education and services for young people, as well as collaboration between different community actors, such as parents, churches, teachers, police officers, paralegal workers, school administrators, health management committees, local provincial administration and parents. Whilst some actors were resistant to the GUSO programme at first, they eventually changed their minds:

‘Some churches didn’t allow [SRH education], but through our efforts, now they are giving us that platform, that is a great achievement’ (GUSO staff member, Kisumu).

As a result of greater acceptance from their communities, peer educators gained access to platforms through which they could highlight issues of importance to them, including adolescent sexuality; teenage pregnancy; unsafe abortion; return to schools for pregnant girls and young mothers; drug use; justice for survivors of sexual violence; and reduction in child marriage. New spaces opened up for young people to voice their concerns, including policy-making forums and new decision-making opportunities within the GUSO implementing partners (Peer educator, Siaya).

Parents and the community were initially not very supportive of the programme, but now having seen the positive changes in behaviours of youth in the community, they are supportive. Issues of drug abuse used to cause a lot of dropout and idle youth in the community but this has changed … (Peer educator, Kisumu)

We speak during public meetings, and we have gained acceptance and conduct dialogue on issues that were previously difficult to discuss such as adolescent sexualilty and teenage pregnancies. (Peer educator, Siaya)

Peer educators tackled sensitive issues, increasing openness to discussion amongst stakeholders in the community and gaining support for engaging with such concerns. One adult stakeholder shared the following: ‘Unlike in the past, peer educators are able to address sensitive topics in the community such as teenage pregnancy and unsafe abortion’ (Local government representative, Siaya).

Organisational and programmatic strengthening

Strengthening the Kenya SRHR Alliance was the first outcome area of the GUSO programme in Kenya. However, peer educators’ contribution to this element of work was not measured. Our study findings highlight how peer educators not only brought enhanced visibility to implementing organisations but, also, taught them what being accountable to young people meant in practice.

Adult stakeholders interviewed credited peer educators with bringing greater visibility to the work of their organisations, making them more credible and known about for their ability to reach youth. Programme participants agreed, with one group saying that there were ‘more partnerships with the community’ as a result of peer educators’ innovative activities [FGD3]. Several peer educators noticed a shift in how supportive organisations were for youth, with one commenting: ‘[The partner organisation] has become more supportive of youth’ (Peer educator, Kisumu). According to one peer educator, implementing GUSO partners saw ‘an increase in youth participation in [their] programme activities and in the community’ (Peer educator, Siaya).

Apart from strengthening organisations, peer educators were recognised as strengthening the GUSO programme as a whole. Peer educators were seen, and saw themselves, as links between various components of the programme, including services, information/outreach, advocacy, youth participation, advocacy and monitoring and evaluation. At the county level, a government stakeholder noted the importance of linkages created with peer educators:

‘We were constantly ensuring, for every meeting at county level, [that] youth peer providers were there to represent the programme – at stakeholder meetings, county meetings that needed young people’s voices’ (GUSO staff member, Kisumu).

Another stakeholder observed that peer education not only expanded the reach of the programme within communities but, also, provided a way to sustain efforts beyond the life of the programme:

[Peer educators] contributed to more sustainable programming. Use of youth in provision of information and linkage to services at the community has a lasting impact on the youth themselves and community at large. They provided extra human resources that TICH could not afford, to reach all the areas within the project time. Using community own resource persons is more sustainable for programs. We are now more focused in supporting youth to take leadership in programming and to better understand the dynamics in youth programming. (GUSO staff member, Siaya)

Gender norm transformation

Study participants reported many examples of changes in gender norms brought about by peer education. These included greater value being placed on girls’ education, including for pregnant girls and young mothers; greater acceptance of girls desiring relationships; positive views of girls who do not follow traditional gender roles; encouragement for the sharing of responsibilities between boys and girls; and community mobilisation to encourage reporting and prosecution in cases of sexual violence.

It is true, it has changed a lot. Before, ladies and girls were regarded like people who were not meaningful in society …. Get married and that’s just our life, and now we are very concerned with girls’ education, a lady who is empowered …. can have strong health and life. (GUSO staff member, Kisumu)

More girl[s are] empowered to say no (to unwanted sexual advances). The belief that a girl should be [a] housewife has changed. They too can get jobs and work. Before, girl children could not speak out with parent[s] on SRH, but now they are free to talk …. Sharing ideas in the community was difficult but through GUSO we are free to express ourselves. (Peer educator, Siaya)

Study participants mentioned change in relation to the reporting of sexual violence in their communities. One peer educator explained: ‘I think it is a bit easier now to get community support for arrests of defilements {perpetrators} especially among relatives.’ [PE10] Young programme participants also mentioned how peer educators were working with chiefs and village headmen to ensure that sexual violence cases were reported to the police; the latter spoke of knowing the steps to follow in the case of rape and how to speak out as a result of interacting with GUSO peer educators (FGD1). One peer educator also mentioned working with county level officials to develop a new sexual and gender-based violence policy (Peer educator, Kisumu).

Youth economic empowerment

By working together, peer educators found unity of purpose, leveraging the network created as an opportunity to create economic opportunities for themselves and other young people. Peer educators in Siaya and Kisumu Countiesd formed small groups called chamas that evolved into community welfare services, saving schemes and business groups. Some chamas initiated enterprises that made and sold baked food, sanitary towels and jewellery, whilst others started grocery and tree seedling planting businesses. Two peer educators explained how they had been able to establish their businesses using the allowances they received as peer educators. To ensure viability, one stakeholder described how ‘peer educators [had] engaged local politicians and secured sponsorship for income generating activities such as setting up a small gasoline station’ (GUSO staff member, Siaya).

The ripple effects of this entrepreneurship were evident at various levels of the community. Peer educators engaged other young people in these economic endeavours, thus expanding their collective economic power. During one focus group discussion, a participant commented how by ‘making necklaces, sanitary towels and small grocery business, youth are becoming more independent and charting their own future’ [FGD1]. Peer educators also reported an increased ability to support their families, including paying for their own or siblings’ school fees, accumulating savings, enhancing their social status, and gaining recognition for being role models.

Confidence, life goals and employability

Study findings suggest increased self-confidence amongst both programme participants and peer educators as a result of their participation in the GUSO programme. This in turn contributed to changes in life goals and aspirations as well as job opportunities.

For programme participants, changes were shaped by participation in activities such as sport and drama, which enhanced their self-esteem, as well as enhanced awareness of their own health and rights (FGD1). One group of participants observed that after engaging with peer educators, they were better equipped to deal with peer pressure (FGD1).

Many peer educators also experienced increases in confidence. Factors that contributed to this included training, volunteer experience, being seen as role models, and public speaking engagements.

I was green at recruitment but with training received, and experience gained, I have been capacity built and am now able to teach and provide information to the youth. It has boosted my role at the facility, and I now hope to be a doctor one day. (Peer educator, Siaya)

Changes were also witnessed in peer educators’ employability beyond their own communities. One stakeholder described how some GUSO peer educators transitioned to take up more responsibilities including jobs elsewhere in Kenya:

For me, the peer educators I worked with are now running programmes. I was in a conference with one of my peer educators, and the way she was articulating issues made me feel that the peer educators, if empowered and mentored, can deliver. … I have been able to witness peer educators [running] programmes. They are in full-time employment. One works with M-TIBAFootnote9; one is a county commissioner; and another one (works) with Family Health Options Kenya. There is one in Nairobi with an organisation. [Peer education] has been providing them with a platform that puts them on a career path. (GUSO staff member, Kisumu)

Discussion

As stated at the outset, peer education has traditionally been measured in relation to its effectiveness in changing SRH knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. In relation to these outcomes, the international peer reviewed literature reports mixed results (Tolli Citation2012; Michielsen et al. Citation2012; Chandra-Mouli, Lane, and Wong Citation2015; Siddiqui et al. Citation2020), although these understandings have, arguably, been shaped from a narrow vantage point. Few programmes have documented their design and even fewer have considered how design may have affected outcomes. Across the literature, both peer reviewed and grey, it is not uncommon for peer education studies of high quality to be assessed together with lower quality, more haphazard forms of programming. It is, therefore, no surprise that the existing literature presents mixed results of peer education’s effectiveness.

This study’s findings indicate that what was formally measured by the GUSO programme and its evaluation was the tip of the iceberg when it comes to peer educators’ contributions. Whilst some achievements, such as youth economic empowerment, may not have been intended or expected by the programme designers, others such as enhancing community support for SRHR and strengthened partner organisations, may have been expected – and even assumed – to flow from peer educators’ involvement in the programme. However, without a suitable measurement framework and data to evidence such contributions, peer educators were not recognised for these ‘invisible’ roles.

Of special note is the interlocking role that peer educators played in the GUSO programme – admittedly, a difficult contribution to measure. They worked with adult community members to increase acceptance of young people’s rights, ensuring that the programme could operate. They made sure that young people knew about their SRHR and, then, linked them to services that ensured their health and well-being, sometimes accompanying them to those services. They monitored SRH service provision to ensure its responsiveness to young people’s needs and informed service providers when it was lacking. And, they did their best to keep implementing partners accountable, ensuring youth voices were heard in relevant decision-making spaces. In all their roles, peer educators were enablers – of access, quality and accountability, even social norm change – and ensured the overall health of the GUSO programme.

Limitations

In its last year of implementation, the GUSO programme faced high rates of peer educator attrition resulting from the impact of COVID-19 restrictions and the impending closure of the programme in November 2020. Data collection for this study was conducted after the official close of the programme; this limited the cohort from which the study sample was selected. This limitation was mitigated by selecting two sample sites that allowed for some contrast and variability within similar settings. Nevertheless, study findings could have been affected by recall bias. This was mitigated through carefully designed qualitative tools that allowed for probing. Additionally, the selection of study participants prioritised those who were still active at close of the programme, which was approximately one month before the study commenced.

Conclusion

Reading the findings of this study together with those of the aforementioned papers, a simple conclusion emerges: the way that peer education is expected to contribute to programming must change and, along with that, the way its effectiveness is measured. Despite the prolific use of peer education globally, the frameworks used to measure its effectiveness continue to focus on a narrow set of outcomes. Findings from this study provide an illustration of how peer educators’ contributions to multicomponent SRHR programmes often exceed the envisioned roles and outcomes related to their work. The authors are not proposing that each and every SRHR programme measures any and all potential outcomes of peer education. Rather, what is encouraged is a recognition of the breadth of peer educators’ potential contributions; intentionality in the design of multi-component programmes that include peer education; innovation in the selection of indicators used to monitor and evaluate youth SRHR programmes; and, in general, a higher value placed on peer education that is commensurate with their measured and unmeasured contributions to programming.

Data availability

Qualitative data are available on a private, password-protected Google drive folder accessible only to the authors of this study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to the SRHR Alliance in Kenya and partners implementing the GUSO programme for their assistance in identifying and organise study participants.

Disclosure statement

IPPF contracted The Torchlight Collective to undertake this study, and authors 1-3 were contracted through the Collective as freelance consultants experienced in qualitative research on SRHR. At the outset of the study, authors 4-5 were employed by the SRHR Alliance Kenya; author 6 was employed by Rutgers; and author 7 was employed by IPPF. Authors 4-7 were involved in the implementation of the GUSO programme at either the national level (4-5) or at the global level in all implementing countries (6-7). Given that the GUSO programme - and thus funding for their staff positions - came to an end during the course of this study, authors 4, 5 and 7 are no longer in employment at these same institutions.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. People aged 10 to 24.

3. IPPF, Dance4life, Choice for Youth and Sexuality, Rutgers, Simavi and Aidsfonds.

4. Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Pakistan and Uganda.

5. Anglican Development Services [ADS] Nyanza, Ambassadors for Youth and Adolescents Reproductive Health Programmes [AYARHEP], Centre for the Study of Adolescence [CSA], Family Health Options Kenya [FHOK], Tropical Institute of Community Health Development [TICH], Kisumu Medical Education Trust [KMET], Nairobits Trust, Network for Adolescence and Youth of Africa [NAYA], Support Activities in Poverty Eradication and Health [SAIPEH] and Women Fighting AIDS in Kenya [WOFAK].

6. Nairobi, Kisumu, Siaya, Homabay, Kakamega and Bungoma.

8. ‘SRH services’ here refer to clinical/health services available from implementing partners, including: counselling, contraceptives, comprehensive abortion care, HIV and AIDS, STIs, obstetrics, gynaecology, urology and referrals.

9. M-TIBA is a leading health financing technology platform for consumers, insurers, healthcare providers, and governments.

10. GUSO Kenya (Citation2021).

11. SRHR education refers to provision of comprehensive sexuality education using a structured curriculum.

12. SRHR information referred only to information that was ‘personalised’ and provided through direct (online or face to face) interaction. It did not include information provided in mass through large gatherings or online platforms, which was monitored separately.

13. ‘Direct services’ were provided to young people directly by one of the Kenya SRHR Alliance’s GUSO implementing partners and covered covered counselling, contraceptives, comprehensive abortion care, HIV and AIDS, STIs, obstetrics, gynaecology, urology and referrals.

14. ‘Indirect services’ were those provided by public clinics or private providers that were not members of the Kenya SRHR Alliance but who benefitted from the Alliance’s training, mentorship and resources.

References

- Billowitz, M., H. Evelia, L. Menard-Freeman, and K. Watson. 2020. “Asking the Right Questions: Existing Evidence and the Research Agenda for Youth Peer Education in SRH Programming.” https://www.getupspeakout.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/GUSO-Asking%20the%20Right%20Questions.pdf

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., C. Lane, and S. Wong. 2015. “What Does Not Work in Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Review of Evidence on Interventions Commonly Accepted as Best Practices.” Global Health: Science and Practice 3 (3): 333–340.

- GUSO. 2018. “GUSO Midterm Evaluation.” https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/GUSO%20Midterm%20Evaluation%20report_FINAL_24July2018.pdf

- GUSO Kenya. 2021. GUSO Kenya Monitoring - Aggregate Figures 2016–2020. Kenya: SRHR Alliance, Kenya.

- Kok, M., T. Kakal, P. Godia, and J. Olenja. 2021. “Get up Speak Out! End-line Report Kenya.” Amsterdam: KIT Royal Tropical Institute. https://www.getupspeakout.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/GUSO%20Kenya%20Endline%20Report%20Feb%202021%20%28Final%29.pdf

- Michielsen, K., R. Beauclair, W. Delva, K. Roelens, R. Van Rossem, and M. Temmerman. 2012. “Effectiveness of a Peer-led HIV Prevention Intervention in Secondary Schools in Rwanda: Results from a Non-randomised Controlled Trial”. BMC Public Health 12:729. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-729

- Siddiqui, M., I. Kataria, K. Watson, and V. C. Mouli. 2020. “A Systematic Review of the Evidence on Peer Education Programmes for Promoting the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young People in India.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28: 1. doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494.

- Tolli, M. V. 2012. “Effectiveness of Peer Education Interventions for HIV Prevention, Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention and Sexual Health Promotion for Young People: A Systematic Review of European Studies.” Health Education Research 27 (5): 904–913.