ABSTRACT

Fertility information is an important component of comprehensive sexuality education, but the extent to which adolescents are taught or informed about fertility is unknown in Australia. This study examined knowledge of fertility using an anonymous, online survey of > 2,600 adolescents aged 15–18 across Australia. Respondents represented diverse backgrounds, including sexuality and gender diversity (>60% identifying other than heterosexual, 17% gender identity other than man/woman). Average knowledge of fertility was significantly poorer compared to average knowledge of reproductive and sexual health content linked to the national curriculum (p < .001). Linear regression and LASSO variable selection modelling identified significant, but small associations between some sociodemographic factors and knowledge about fertility or overall reproductive and sexual health. Over 80% of respondents considered their sexual health education insufficient, which was associated with poorer knowledge on all outcomes measured in linear regression models. These findings suggest that including fertility content explicitly within the Australian national curriculum will likely increase adolescent understanding of fertility. The strong participation of the adolescent LGBTQ+ community in the survey demonstrates their interest in contributing to reproductive and sexual health education reform. Inclusivity, particularly of sexuality and gender should be a key consideration in reproductive and sexual health education delivery in Australia.

Introduction

Comprehensive Sexuality Education seeks to provide children and adolescents with accurate and developmentally appropriate knowledge. It also aims to foster positive values, such as respect for human rights, gender equality and diversity, as well as attitudes and skills that promote safe, healthy and positive relationships (Herat et al. Citation2018). This kind of education is of the utmost significance since it enables children and adolescents to reflect upon societal norms, cultural values and traditional beliefs, thereby enhancing their understanding and management of interactions with peers, parents, teachers, other adults and the wider community (Herat et al. Citation2018).

There is an urgent need to expand reproductive and sexual health education in Australia (Marson Citation2022; Mitchell et al. Citation2011). Also known as relationships and sexuality education, or sexual health education, reproductive and sexual health education aims to cover a range of biological and psychosocial aspects. However, the topic of fertility is often omitted from Australian sexual health education due to a historic focus on prevention of pregnancy as opposed to overall reproductive and sexual health and wellbeing. Regarding biological aspects, a critical discourse analysis of versions seven and eight of the Australian Curriculum (at the time of writing it is now approaching its ninth iteration) identified that even though it was considered important, the word ‘reproduction’ did not appear in any of the content descriptions for specific learning criteria (Ezer et al. Citation2019). The national curriculum’s positioning as a framework and set of guidelines means there is a lack of prescribed content, which may lead to the exclusion of critical concepts (including fertility) perceived as controversial or difficult to teach. Teacher lack of confidence and individual and state level school policy (Walker et al. Citation2021) also affect what is included.

The United Nations International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education assists the development of evidence-based educational programmes, and fertility features prominently in Concept 6 – which concerns the human body and development (UNESCO, UN Women, UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA and UNAIDS Citation2018). The only current evidence for fertility-related content taught in schools comes from Australia’s National Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) Strategy (Australian Government Department of Health, Citation2018) which seeks to prioritise education about problems caused by STIs, including infertility. Most definitions of reproductive and sexual health encompass far more than the absence of disease but stress the importance of physical, mental and social wellbeing matters relating to the reproductive systems, functions and processes (Fernandes and Junnarkar Citation2019; World Health Organization Citation2006). It is important for adolescents and young people to encounter information beyond the infertility caused by STIs, if we are to consider fertility and optimal reproductive health part of comprehensive sexuality education.

Infertility globally has been estimated to affect 1 in 6 couples of reproductive age (Boivin et al. Citation2007; Cui Citation2010). There are many behavioural, or otherwise modifiable factors that lead to infertility which can be complicated by a lack of understanding about when to seek treatment or support for reproductive system issues (Rossi, Abusief, and Missmer Citation2014; Sharma et al. Citation2013; Herbert, Lucke, and Dobson Citation2009). The International Reproductive Health Education Collaboration posits that education about fertility and reproductive health is critical during adolescence to support informed decision-making and prevent unwanted childlessness (Harper et al. Citation2021). The Reproductive Health Education Collaboration has recently supported the implementation of fertility education in UK secondary schools in 2019 (Department for Education Citation2019). Adolescents have a unique set of needs relating to fertility as part of reproductive and sexual health programmes and interventions, including information, services and counselling around fertility, and subfertility (reviewed in Engel et al. Citation2019). This information and service provision is critical to promoting reproductive health and wellbeing in this life-stage and beyond.

There is an overall paucity of data on Australian adolescent knowledge and/or awareness about fertility. The 7th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health identified that approximately 42% of the 6,830 students surveyed correctly identified that Chlamydia can lead to infertility (Power et al. Citation2022). Earlier research for the 5th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health examined student recognition of eight factors influencing fertility. It identified that at least half of all respondents could identify six of the eight factors (Heywood et al. Citation2016). However, national studies of fertility knowledge demonstrate that even though the Australian public can enumerate the factors influencing fertility, it consistently underestimates the extent of their impact on fertility while overestimating the ability to overcome fertility issues through assisted reproductive technologies (Ford et al. Citation2020; Hammarberg et al. Citation2017, Citation2013).

Against this background, the aim of this study was to examine the knowledge that adolescents and young people in Australia have about fertility (including infertility risk factors and prevalence), in comparison to other reproductive and sexual health topics taught in schools. Data were collected by means of an anonymous, online, cross-sectional survey which sought to investigate the relationship between a range of sociodemographic factors and relevant forms of knowledge. A secondary aim was to investigate possible demographic contributions to the uncertainty present in responses in the survey. The findings of this study should provide a better understanding of the gaps in adolescent reproductive and sexual health knowledge and may be used to inform efforts to include fertility in future forms of education.

Methods

Study participation

This study was approved by the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Administration (Protocol H-2020–0302). Respondents aged 15–18, living in Australia, provided active, informed consent. Respondents were excluded if they skipped a question relating to age and if they incorrectly answered items assessing their consent to participate (as per Mackenzie et al. Citation2020). In this study, respondents were eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the former criteria and responded to at least one of the knowledge items.

Survey design

An anonymous, online survey was used to capture knowledge about sexual health and fertility. QuestionPro (QuestionPro Citation2023) was used to host the survey (details of which are available from the corresponding author on request). All respondents provided information regarding sociodemographic factors aligned to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) standards for country of birth, language spoken at home other than English, English language proficiency, gender, and sexuality. Respondents were asked to report their age and future parenting intentions. Finally, respondents were asked a question to assess whether their sexual health educational experiences were sufficient: ‘was your school able to answer all the questions you had or have about sexual health?’. Respondents also completed 13 knowledge based multiple-choice items about reproductive and sexual health. Importantly, all the knowledge items were accompanied by an option to select ‘unsure’ to reduce forced guessing and skipping.

Knowledge items were grouped into three categories, content aligned to the Australian National curriculum (5 items), content not within the curriculum that explicitly related to fertility and infertility (5 items), and other reproductive and sexual health-related items that were not explicitly within either of the former categories (3 items). The number of the questions was chosen to make the survey engaging so as to minimise dropout, while collecting information on areas not yet assessed for members of this cohort.

For fertility-related items, we chose to adopt question composition and formats similar to those used in other fertility awareness studies (Bunting, Tsibulsky, and Boivin Citation2012; Wojcieszek and Thompson Citation2013; Hammarberg et al. Citation2013; Ford et al. Citation2020) and which may serve to contextualise the findings of the study in the wider literature.

Sampling and data collection

Data were collected in two recruitment periods totalling 4 weeks (in May and October 2022). Recruitment took place via advertisements on social media (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, USA) using targeted advertising to reach the intended audience (young people aged 15–18 based in Australia). This was the sole recruitment measure, and the link to the survey was made available through advertisements on Facebook and Instagram. Respondents who completed the survey could enter a prize draw for an AUD 75 e-gift card.

On close, survey responses were recoded following the removal of excluded or ineligible respondents. Respondent location was determined by postcode and recoded into latitude and longitude using a publicly available dataset (Proctor Citation2022). The remoteness of postcodes was determined by the University of Sydney’s ARIA (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia) (Glover and Tennant Citation2003) lookup tool. In the case that two ARIA classes were present for a given postcode, the ARIA codes (which fall within a range of 0 to 4), were given a .5 class to indicate inclusion in both classes.

Knowledge question items were recoded into binary and trinary format. Binary format coded a correct response as 1, and incorrect or unsure responses as 0 for each item. Missing values were left blank and are shown in descriptive data where relevant. Trinary format involved a classification of correct, incorrect, or unsure for each knowledge item. Three outcome measures were defined to summarise participants knowledge, namely, the overall score across the 13 knowledge items (range = 0–13), the score for fertility knowledge items only (range = 0–5), and the count of ‘unsure’ response across all items (range = 0–13). Dichotomised versions of most sociodemographic characteristics were also generated for use in modelling. Considering the fact that the English proficiency variable received only ‘very well’ and ‘well’ responses, it was dichotomised. In tables reporting data on variables with many possible options (e.g country of birth, language other than English spoken at home, gender, sexuality), only classes representing ≥ 1% are displayed, all others are grouped together as ‘other’ for simplicity in visualisation.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were performed in RStudio (version 2022.12.0 + 353), Skipped question responses were classified as missing. Frequencies of missing data are reported in the relevant sections. Statistical significance was set at 5%. Frequencies and proportions were calculated for all demographics measures. Summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, range) were calculated for all outcome scores. Outcome scores were plotted (using histograms using the ggplot2 package) and skewness was calculated (using the moments package).

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to quantify the effects of each demographic factor on participants’ sexual health and fertility knowledge via the three outcome scores. For the variables country of birth, language, gender and sexuality, ANOVA was only performed for categories with > 1% frequency, in addition to the binary version of the variable. Levene’s test was used to assess homogeneity of variance, and Q-Q plots for normality. Welch’s ANOVAs were used when there was significant evidence of variance heterogeneity. Due to the large sample size, normality was assumed (Kwak and Kim Citation2017), except in the case of classes with < 30 observations – here, the Q-Q plots were assessed. A student’s t-test was used to compare mean score in curriculum-aligned and fertility-aligned knowledge items.

A multivariable linear regression model was run for each of the three outcome measures, with all the statistically significant demographic factors identified in the ANOVA modelling used as predictors. Complete case analysis was used (only records with complete data used), model summary statistics were computed (degrees of freedom, F-value, adjusted R-squared, and p-values), with regression coefficients (β), standard errors, and t-/p-values reported.

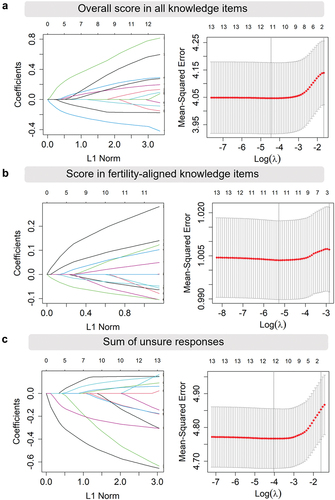

The LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) (Tibshirani Citation1996) procedure was performed using the glmnet package (Friedman, Hastie, and Tibshirani Citation2010) as an alternative to identify significant predictors of each outcome measure. A model was run for each of the three outcome measures, with each of the demographics entered as potential predictors. Variable coefficients were plotted against the shrinkage parameter (lambda). The optimal lambda was determined via k-fold cross validation. The cross-validation curves were plotted with the number of non-zero coefficients and the standard deviation. The optimal model was selected as the most regularised model such that the cross-validated error is within one standard error of the minimum.

Results

Survey participation

A total of 4,362 respondents began the survey, and 59.7% (2,602) of those that responded satisfied inclusion criteria for analysis. Reasons for exclusion were: not responding to the age question (n = 73), incorrectly responding to items judging consent (n = 412), or not responding to any knowledge items (n = 283). 992 respondents exited the survey before they completed the consent items on their second and final attempt.

Respondent sociodemographic information and parenting intentions

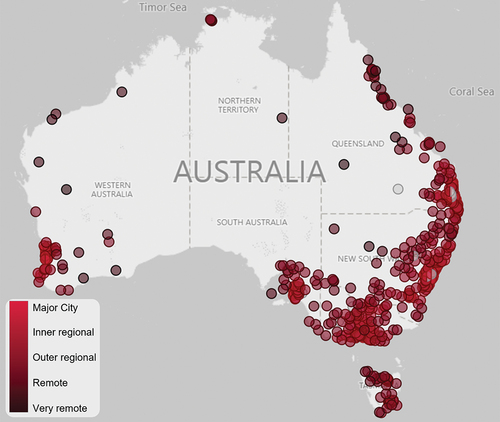

Respondent sociodemographic data are displayed in . Young people aged 15 to 18 years were eligible for inclusion in the survey, yet only about 5% of respondents were 18 years old, with the majority being aged 17 (~39%). Most respondents resided in a major city (49.4%), but with representation from all categories of remoteness in the ARIA index, and representation from all states and territories in Australia (). Respondents came from diverse cultural backgrounds, with 8.5% being born outside of Australia (with about half of those born overseas in non-English speaking countries), 10.3% speaking a language other than English at home, and 5.9% identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. There was also strong LGBTQ+ representation; with 17.3% of respondents identifying outside of the gender binary (i.e. other than man or woman), 20.4% reporting that their gender was different to their assigned sex at birth (gender incongruence), and > 60% reporting a sexuality other than heterosexuality (sexuality diversity). Respondents could self-report their preferred terms for gender and sexuality, and lists responses that represented at least 1% of the respondent cohort, with the remaining responses categorised as ‘other’.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

Figure 1. Respondent remoteness and geographical distribution. Postcode data was used to generate a geographical map of respondent location. Colour indicates the remoteness level according to the Accessibility/remoteness Index of Australia, with major city classification in the lightest shade, through to very remote in the darkest. Data based on n = 2507 respondents whose ARIA classification was able to be determined.

Respondents were asked if they intended on becoming parents someday (60.7% said yes), and at what age they would like to start a family. Of those that wanted to become parents, about 60% indicated that between 25 and 30 years was the age at which they would like to have their first child, followed by 18–24 years (23.5%), then 31–36 years (14.4%). Finally, respondents were asked a question relating to the sufficiency of their reproductive and sexual health education. Overwhelmingly, the majority of respondents selected ‘no’ for this item (2,084 adolescents or 80.1% of cohort).

Knowledge of reproductive and sexual health

To assess knowledge of fertility and sexual health, respondents were asked to respond to 13 multiple choice questions (including seven true/false). Responses to the 13 knowledge items are shown in together with the number and proportion of correct and incorrect responses, with the ratio of these plotted as a progress bar/status indicator in the final column. The knowledge item with highest proportion of correct responses was within the fertility-aligned knowledge items. Over 90% of participants responded correctly to the item ‘at a certain time in the menstrual cycle, it is much easier to become pregnant’. The highest proportion of incorrect responses was to a curriculum-aligned item concerning contraceptive effectiveness (57.5% incorrect), to which respondents more frequently selected the male condom as the best option to prevent pregnancy over a contraceptive implant. The ‘unsure’ option for the knowledge items was well-subscribed among respondents. The item with the highest proportion of unsure responses was an item about the leading cause of infertility in Australia (49.3% unsure).

Table 2. Proportion of correct, incorrect and unsure responses to 13 sexual health knowledge items.

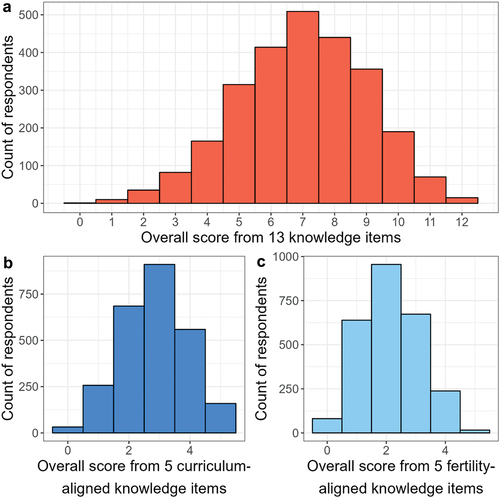

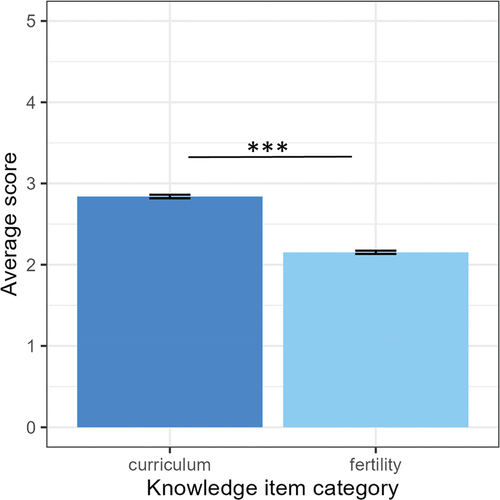

The cumulative overall score for the knowledge items was approximately normally distributed, with a slight left skew (skewness= −0.12). No respondents scored all 13 knowledge items correctly. The mean number of correct responses was 6.99 (SD = 2.04). In comparison, the distributions for the cumulative scores for the curriculum aligned items () and fertility-aligned items () were also slightly skewed yet in opposite directions (curriculum-aligned skew= −0.07, fertility-aligned skew = 0.18). The average score for the curriculum aligned items (2.84 correct out of 5 correct) was significantly higher for respondents than their score on the fertility-aligned items (2.2 correct; Welch’s t = 23.5, degrees of freedom = 5169.9, p < .001, 95% CI of mean difference [0.63, 0.75]) as seen in . This suggests that knowledge about fertility-related matters was poorer than knowledge about reproductive and sexual health content taught in high schools.

Figure 2. Distribution of sexual health knowledge score among adolescent respondents. Respondents responded to a 13-item sexual health knowledge assessment, and their (a) overall score is plotted as a distribution of the frequency of each score. Two subsets of question-item topics that are presented showing (b) the distribution of respondent scores on five items aligned to the Australian curriculum, and (c) the distribution of respondent scores on five items relating to fertility. Data derive from n = 2602 respondents; respondents who selected ‘unsure’ were regarded as incorrect.

Figure 3. Average score differs between curriculum-aligned and fertility-aligned question items. Respondents responded to a 13-item sexual health knowledge assessment, and their average score in the subset of five items aligned to the Australian curriculum (dark blue), and the five items relating to fertility (light blue). Data come from n = 2602 respondents; respondents who selected ‘unsure’ were regarded as incorrect. Statistical difference determined by t-test, *** denotes p < .001.

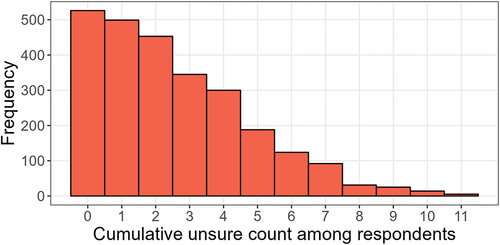

The distribution of the cumulative number of unsure responses is shown in and follows a skewed right distribution (skewness = 0.92), with a mean of 2.6. The maximum number of unsure responses selected for individual respondents was 11 (n = 5), and the minimum number of unsure responses was zero (n = 1,025).

Figure 4. Distribution of unsure responses for knowledge items. Respondents responded to a 13-item sexual health knowledge assessment, which included an ‘unsure’ response. The distribution of respondents’ sum of unsure responses across the 13 knowledge items is shown. Data come from n = 2602 respondents.

Factors associated with reproductive and sexual health knowledge

Age, gender (binary classification), gender incongruence, sexuality (categorical and binary classification), aspire to parenthood, remoteness (binary classification) and English language proficiency were found to be significantly associated with outcome measure 1 (overall score across the 13 knowledge items) in the one-way ANOVA analysis (). The magnitude of these effects was generally small however (<6% shift from the mean score).

Table 3. Summary of one-way analysis of variance.

English spoken at home (binary classification), gender (categorical and binary classification), gender incongruence, sexuality (categorical and binary classification), aspire to parenthood and English proficiency were all found to be significantly associated with outcome measure 2 (score across fertility-aligned items) in the one-way ANOVA analysis. The effect magnitude was generally small, with differences in mean scores between predictor levels ranging from 2 to 4%.

Finally, age, gender (binary and categorical classification), gender incongruence, sexuality (binary and categorical classification), aspire to parenthood and English proficiency were significantly associated with outcome measure 3 (count of ‘unsure’ response across all 13 items) in the one-way ANOVA analysis. Small effect magnitudes were once again observed, with mean differences ranging from 2.3 to 5.3% amongst predictor levels.

All sociodemographic variables that were statistically significant in the ANOVA procedures were entered with the variable measuring reproductive and sexual health education sufficiency, as predictors in multiple linear regression models. Any observation with missing data was omitted, which left 2,089 remaining observations, a loss of approximately 20% of data. Parameter estimates for each of these models are presented in , with summaries of the models in . Six of the eight predictors entered into the model had a significant influence on the outcome of overall knowledge score, yet the effect sizes on the outcome were very small, as evidenced by the coefficient β < 1.The predictors with a minor positive influence on overall score were respondent age of 18, living in a major city, English language proficiency (‘very well’), the belief that their reproductive and sexual education was sufficient, and wanting children someday. There was one predictor with a minor negative influence on overall score in the knowledge items: namely, when the respondent’s gender was incongruent with sex.

Table 4. Linear regression model parameters and coefficients.

Table 5. Linear regression model summary.

Of the seven predictors entered into the model, English language proficiency, and reproductive and sexual health education sufficiency were found to be statistically significant (with a very small effect size). All other predictors were not associated with a change on score of fertility-aligned items (). For respondents who spoke English ‘very well’, their fertility knowledge score was predicted to increase by 0.3, and those who believed their reproductive and sexual health education was sufficient it was predicted to increase by 0.1. Finally, respondent age of 18, whether they wanted children someday, and reproductive and sexual health education sufficiency all had statistically significant negative, (albeit very small) effects on the number of unsure responses in the multiple linear regression. This indicated that respondents below the age of 18, those who reported that their reproductive and sexual health education was not sufficient, and those who were either unsure or had decided against children in the future showed an increase in unsure responses to the knowledge items.

Consistent with the linear regression models, the LASSO procedures showed the demographic variables demonstrated a limited influence on each outcome. In the optimal model of the overall score on knowledge items (lambda = 0.19; SE = 0.12; ), the score in fertility-aligned question items (lambda = 0.06; SE = 0.03; ), and the sum of unsure responses (lambda = 0.24; SE = 0.14; ), all coefficients were shrunk to zero. This implies that that the sociodemographic characteristics had no significant effect on predicting any of the three outcome measures of interest.

Figure 5. Lasso variable selection coefficients by L1 Norm. In left-most plots, curves correspond to a variable (numbered), showing the path against the L1 Norm as lambda varies in the inverse direction. The top axis indicates the degrees of freedom, or number of non-zero coefficients excluding the intercept. The right-most represent the cross-validation curves for given lambda values. Bars indicate upper and lower intervals as a function of the standard deviation. The dotted vertical lines indicate the model corresponding to the minimum MSE (leftmost line), and the model with the largest value of lambda for which the MSE is not above one standard error from the minimum (rightmost line, model chosen for this study). (a) variable selection and cross validation for modelling overall score in the knowledge items, (b) variable selection for modelling score in fertility-aligned items, and (c) variable selection for modelling sum of unsure responses.

Discussion

This study was the first of its kind to examine fertility and reproductive and sexual health knowledge among > 2,600 Australian young people from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds. Overall, our key findings show that knowledge about fertility was poor, and lower than reproductive and sexual health concepts included in the Australian national curriculum. We sought to examine the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on knowledge about fertility and reproductive health and found only a weak association between these factors and knowledge about fertility and reproductive and sexual health generally. This study provides new evidence of the gaps in fertility knowledge of adolescents in Australia and presents an opportunity for growing this knowledge by enshrining it into the national curriculum.

Study respondents were representative of diverse demographics including sexuality and gender

The survey captured adolescents from a range of geographical locations, across every Australian state and territory. Respondents represented a diversity of sexuality and gender, and cultural backgrounds. While the cohort in this study cannot be considered an unbiased representative sample due to our recruitment methods, new insights can be highlighted from our findings in relation to the diverse demographics of our respondents.

Characteristics of the cohort that were not representative of national data include our strong representation from adolescents in the LGBTQ+ community In this study, over half of respondents identified beyond heterosexuality and the gender binary, yet, the ABS published in 2020 that a small proportion (6.1%) of young Australians aged 15–24 reported sexuality other than heterosexual (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2020). It has also been estimated that transgender people make up approximately 1% of the population, a figure expected to be greater in young people but the extent to which is unknown (Marina Carman et al. Citation2020). The LGBTQ+ representation in this study presents a unique strength of the findings, as people of diverse genders and sexualities are understudied in fertility knowledge research. There is therefore a need for more education on sexuality and gender diversity relating to fertility and pathways to parenthood for young people. The sexuality and gender representation in this study may have been a consequence of the targeting of our recruitment copy which was a call-to-action for feedback on reproductive and sexual health education (as other elements of this project sought written and verbal feedback). Overwhelmingly > 95% of adolescents believe reproductive and sexual health education is important (Power et al. Citation2022), making this approach to recruitment likely to inspire participation. Additionally, young people of diverse genders and sexualities often feel that sex education is ‘neither inclusive nor useful’ to them (Shannon Citation2022), and that the curriculum lacks diversity regarding sexuality and gender (Waling et al. Citation2020), adding extra motivations for this subset of the adolescent population to engage with our research materials.

Key interpretations and limitations of this study on reproductive and sexual health knowledge

The findings of this study may also be explained by reproductive-health related focus of our knowledge assessment items, rather than the broad spectrum of social topics also within reproductive and sexual health education such as relationships and sexuality. Limited research has been conducted in Australia on this subject, outside of STI-related risks to reproductive health in the National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health, finding that knowledge on this has increased since the late 1990s but has declined a little in the past decade (most recent, Power et al. (Citation2022). One critical limitation of study is that the knowledge assessment only contained five questions explicitly related to fertility, and because of this may not accurately reflect the extent of fertility knowledge of respondents. Further work should be conducted to validate and extend these findings with a broader assessment of fertility knowledge. International evidence of adolescents’ fertility knowledge to date has mostly involved qualitative research, and reveals overall poor confidence in their knowledge about fertility (Boivin et al. Citation2019), and some incomplete and incorrect knowledge about risk factors for infertility (Bodin et al. Citation2023; Ekstrand Ragnar et al. Citation2018). This research contributes a novel, quantitative assessment of knowledge about fertility in adolescents in the Australian context.

Conclusions

This study has provided evidence to support a positive association between overall knowledge of reproductive and sexual health topics and whether the topic was a component of the national curriculum. Therefore, it is critical that we consider the case for implementing fertility concepts as part of the curriculum in Australia. Careful tailoring of fertility information for adolescents in relation to the relevance, attitudes and reception is an important consideration when planning future implementation. Based on the findings of this study, it is important to emphasise the need for inclusivity and consistency in delivery of the sexuality education curriculum. We support and encourage the collaboration of researchers, policymakers and educators to implement an evidence-based, consistent, and inclusive approach towards comprehensive sexuality education that covers content on fertility education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the young people who contributed to this research as participants and Chelsea Green for developing the recruitment material and advertising the survey online. We thank the advisory group that aided the interpretation of the findings and developed a dissemination plan for this work. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the organisations that supported the programme of research from which this work was generated; Joanna Anagnostou from YourFertility and Catherine Kirby from Sexual Health Victoria. The authors also acknowledge the statistical support and revisions provided by Dominic Cavenagh, professional statistician in the University of Newcastle’s Centre for Women’s Health Research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Quantitative data from the survey is available upon request from the corresponding author. The list of survey question items is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. “General Social Survey: Summary Results, Australia.” ABS. Canberra, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/general-social-survey-summary-results-australia/2019.

- Australian Government Department of Health. 2018. Fourth National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2018–2022. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Bodin, M., L. Plantin, L. Schmidt, S. Ziebe, and E. Elmerstig. 2023. “The Pros and Cons of fertility Awareness and Information: A Generational, Swedish Perspective.” Human Fertility 26 (2): 1–10.

- Boivin, J., L. Bunting, J. A. Collins, and K. G. Nygren. 2007. “International Estimates of Infertility Prevalence and Treatment-Seeking: Potential Need and Demand for Infertility Medical Care.” Human Reproduction 22 (6): 1506–1512. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem046.

- Boivin, J., A. Sandhu, K. Brian, and C. Harrison. 2019. “Fertility-Related Knowledge and Perceptions of Fertility Education Among Adolescents and Emerging Adults: A Qualitative Study.” Human Fertility 22 (4): 291–299. doi:10.1080/14647273.2018.1486514.

- Bunting, L., I. Tsibulsky, and J. Boivin. 2012. “Fertility Knowledge and Beliefs About Fertility Treatment: Findings from the International Fertility Decision-Making Study.” Human Reproduction 28 (2): 385–397. doi:10.1093/humrep/des402.

- Carman, M., C. Farrugia, A. Bourne, J. Power, and S. Rosenberg 2020. “Research Matters: How Many People are LGBTIQ?” Rainbow Health Victoria (La Trobe University). https://www.rainbowhealthvic.org.au/media/pages/research-resources/research-matters-how-many-people-are-lgbtiq/4170611962-1612761890/researchmatters-numbers-lgbtiq.pdf.

- Cui, W. 2010. “Mother or Nothing: The Agony of Infertility.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88 (12): 881/. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.011210.

- Department for Education. 2019. “Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education Guidance.” https://www.gov.uk/national-curriculumUnitedKingdomGovernment.

- Ekstrand Ragnar, M., M. Grandahl, J. Stern, and M. Mattebo. 2018. “Important but Far Away: Adolescents’ Beliefs, Awareness and Experiences of Fertility and Preconception Health.” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 23 (4): 265–273. doi:10.1080/13625187.2018.1481942.

- Engel, D., M. Claire, M. Paul, S. Chalasani, L. Gonsalves, D. A. Ross, V. Chandra-Mouli, et al. 2019. “A Package of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Interventions—What Does It Mean for Adolescents?” Journal of Adolescent Health 65 (6): S41–S50. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.014.

- Ezer, P., T. Jones, C. Fisher, and J. Power. 2019. “A Critical Discourse Analysis of Sexuality Education in the Australian Curriculum.” Sex Education 19 (5): 551–567. doi:10.1080/14681811.2018.1553709.

- Fernandes, D., and M. Junnarkar. 2019. “Comprehensive Sex Education: Holistic Approach to Biological, Psychological and Social Development of Adolescents.” International Journal of School Health 6 (2): 1–4. doi:10.5812/intjsh.63959.

- Ford, E. A., S. D. Roman, E. A. McLaughlin, E. L. Beckett, and J. M. Sutherland. 2020. “The Association Between Reproductive Health Smartphone Applications and Fertility Knowledge of Australian Women.” BMC Women’s Health 20 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-00912-y.

- Friedman, J. H., T. Hastie, and R. Tibshirani. 2010. “Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent.” Journal of Statistical Software 33 (1): 1–22. doi:10.18637/jss.v033.i01.

- Glover, J. D., and S. K. Tennant. 2003. “Remote Areas Statistical Geography in Australia: Notes on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA+ Version).” Public Health Information Development Unit, the University of Adelaide. https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/45471/1/hdl_45471.pdf

- Hammarberg, K., T. Setter, R. J. Norman, C. A. Holden, J. Michelmore, and L. Johnson. 2013. “Knowledge About Factors That Influence Fertility Among Australians of Reproductive Age: A Population-Based Survey.” Fertility and Sterility 99 (2): 502–507. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.10.031.

- Hammarberg, K., R. Zosel, C. Comoy, S. Robertson, C. Holden, M. Deeks, and L. Johnson. 2017. “Fertility-Related Knowledge and Information-Seeking Behaviour Among People of Reproductive Age: A Qualitative Study.” Human Fertility 20 (2): 88–95. doi:10.1080/14647273.2016.1245447.

- Harper, J. C., K. Hammarberg, M. Simopoulou, E. Koert, J. Pedro, N. Massin, A. Fincham, A. Balen, and International Fertility Education Initiative. 2021. “The International Fertility Education Initiative: Research and Action to Improve Fertility Awareness.” Human Reproduction Open 2021(4). doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab031.

- Herat, J., M. Plesons, C. Castle, J. Babb, and V. Chandra-Mouli. 2018. “The Revised International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education-A Powerful Tool at an Important Crossroads for Sexuality Education.” Reproductive Health 15 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0629-x.

- Herbert, D. L., J. C. Lucke, and A. J. Dobson. 2009. “Infertility, Medical Advice and Treatment with Fertility Hormones And/Or in vitro Fertilisation: A Population Perspective from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health.” Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33 (4): 358–364. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00408.x.

- Heywood, W., M. K. Pitts, K. Patrick, and A. Mitchell. 2016. “Fertility Knowledge and Intentions to Have Children in a National Study of Australian Secondary School Students.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40 (5): 462–467. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12562.

- Kwak, S. G., and J. H. Kim. 2017. “Central Limit Theorem: The Cornerstone of Modern Statistics.” Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 70 (2): 144–156. doi:10.4097/kjae.2017.70.2.144.

- Mackenzie, E., N. Berger, K. Holmes, and M. Walker. 2020. “Online Educational Research with Middle Adolescent Populations: Ethical Considerations and Recommendations.” Research Ethics 17 (2): 217–227. doi:10.1177/1747016120963160.

- Marson, K. 2022. Legitimate Sexpectations: The Power of Sex-Ed. Melbourne, Australia: Scribe Publications.

- Mitchell, A., A. Smith, M. Carman, M. Schlichthorst, J. Walsh, and M. Pitts 2011. “Sexuality Education in Australia in 2011.” ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 81, Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Power, J., S. Kauer, C. Fisher, R. Chapman-Bellamy, and A. Bourne. 2022. The 7th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2021. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Proctor, M. 2022. “Download Free Database of Australian Postcodes.” Accessed 11 12 2022. https://www.matthewproctor.com/australian_postcodes

- QuestionPro. 2023. https://www.questionpro.com/

- Rossi, B. V., M. Abusief, and S. A. Missmer. 2014. “Modifiable Risk Factors and Infertility: What are the Connections?” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 10 (4): 220–231. doi:10.1177/1559827614558020.

- Shannon, B. 2022. “Hetero-And Cisnormativity in Contemporary Sex Education.” In Sex (Uality) Education for Trans and Gender Diverse Youth in Australia, edited by Y. Taylor, 59–79. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92446-1_4.

- Sharma, R., R. Kelly, J. Biedenharn, M. Fedor, and A. Agarwal. 2013. “Lifestyle Factors and Reproductive Health: Taking Control of Your Fertility.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 11 (1): 66. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-11-66.

- Tibshirani, R. 1996. “Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 58 (1): 267–288. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x.

- UNESCO, UN Women, UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA, and UNAIDS. 2018. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach. Paris: UNESCO.

- Waling, A., R. Bellamy, P. Ezer, L. Kerr, J. Lucke, and C. Fisher. 2020. “‘It’s Kinda Bad, honestly’: Australian students’ Experiences of Relationships and Sexuality Education.” Health Education Research 35 (6): 538–552. doi:10.1093/her/cyaa032.

- Walker, R., S. Drakeley, R. Welch, D. Leahy, and J. Boyle. 2021. “Teachers’ Perspectives of Sexual and Reproductive Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies.” Sex Education 21 (6): 627–644. doi:10.1080/14681811.2020.1843013.

- Wojcieszek, A. M., and R. Thompson. 2013. “Conceiving of Change: A Brief Intervention Increases Young adults’ Knowledge of Fertility and the Effectiveness of in vitro Fertilization.” Fertility and Sterility 100 (2): 523–529. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.050.

- World Health Organisation. 2006. “Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health, 28-31 January 2002.” Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.cesas.lu/perch/resources/whodefiningsexualhealth.pdf.