ABSTRACT

At a time when UK schools are experiencing backlash for ensuring their LGBT+ colleagues and students are included, this article examines the ways in which schools create and uphold cisgender heterosexuality as the dominant narrative. The article presents the findings from four participants who took part in a photo elicitation study to represent their experiences as LGBT+ secondary school teachers in England. The photos and interviews reveal the myriad ways in which cisgender heteronormativity is produced in schools. The data also provides vital examples of how this dominant discourse is beginning to be challenged, and where small everyday acts can successfully disrupt the production of heteronormativity.

Introduction

In December 2023, the UK government released draft, non-statutory guidance to support schools in England to meet the needs of transgender and gender questioning students. The much delayed ‘Gender Questioning Students’ guidance (Department for Education Citation2023) attracted significant criticism, with the suggestion that following the guidance could lead to educational institutions acting unlawfully (White Citation2024). The guidance describes having a gender identity different to birth sex as ‘gender identity ideology’ and as a ‘contested belief’, eschewing definitions of gender used by the World Health Organisation (Citation2024), the National Health Service (Citation2024), and until recently, the UK government itself (ONS Citation2019).

At a time when schools are experiencing backlash for ensuring their LGBT+ colleagues and students are included, this article explores the ways in which schools create and uphold cisgender heterosexuality as the dominant discourse. Gender ideology and indoctrination about different sexualities are charges that have been levied against many schools who have taken steps to ensure LGBT+ inclusion, yet for decades, schools have both implicitly and explicitly ‘taught’ cisgender heterosexuality, without a similar charge or claim. As Mackay (Citation2024) argues, trans and gender questioning people are being blamed for making gender visible.

Gender ideology is real, but it wasn’t invented by trans men or trans women, and it doesn’t just apply to trans or transgender people. The real gender ideology is the binary sex and gender system that requires all of us to be either male-masculine-heterosexual or female-feminine-heterosexual; and which attaches harsh penalties to those who deviate from this script. (Mackay Citation2024)

Cisgender heteronormativity is a social construct, that despite its discursive power, operates silently unless challenged. The existing literature positions schools as stubbornly heteronormative environments (Page and Peacock Citation2013; DePalma and Atkinson Citation2006; Gray Citation2013; Braun Citation2011), where LGBT+ inclusion sits as a source of tension, threatening to disrupt these hidden norms. In previous articles (Brett Citation2022; Citation2024), the experiences of LGBT+ teachers were explored as they negotiated their visibility within these spaces. This article engages with the experiences of these teachers to analyse the systems and structures that construct and maintain cisgender heteronormativity as the dominant discourse within schools. It presents a selected case study from a larger study, in which LGBT+ teachers took photos to represent the spaces in their school where they felt the most and least safe. The significance of these photos was then later discussed in one-to-one interviews which revealed the myriad ways in which cisgender heteronormativity is produced.

By exploring the experiences of four LGBT+ teachers, this article aims to make the invisible, visible, generating important discussion about the ways in which schools are produced as cisgender heteronormative spaces, and crucially, how this production can be disrupted.

Context

It is hard to think of a time when school teachers have been so simultaneously enabled yet discouraged to make LGBT+ inclusion a priority within schools. The year 2003 saw the repeal of Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act in England; which for 15 years sought to prevent local authorities from the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, creating state sanctioned homophobia, discrimination, and moral panic. Despite its repeal, ambiguity and fear exist to this day, with many teachers unsure about what they can or cannot address in the classroom (Lee Citation2019). While the restrictions Section 28 enforced were widely misunderstood, the fear created by the legislation augmented the view that heterosexuality was the only appropriate sexuality that could be visible in schools. Over time, this transformed behaviour towards an expected social norm (Edwards, Brown, and Smith Citation2016), in which LGBT+ teachers self-policed their behaviours for fear as being read as LGBT+ by students or colleagues.

By legal contrast, there has never been a better time for LGBT+ inclusion. Schools in England are now held to account through Ofsted and The Equality Act (Government Equalities Office Citation2010), and through Department for Education statutory guidance updates to Relationships and Sex Education (Citation2019) and Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE) (Citation2021). Despite the legal duty that teachers have in ensuring the safety and inclusion of their LGBT+ young people, media discourse and wider cultural narratives work to produce a form of doublespeak. Protests about LGBT+ curricula in primary schools (Parveen Citation2019), and government officials, including the Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, purposefully using discriminatory and transphobic rhetoric to whip up fear (Leeson Citation2023), leaves teachers apprehensive and uncertain about what their professional duties are.

Scholars have examined the ways that schools are often experienced as cisgender heteronormative environments in which sexuality is not an appropriate topic for discussion (DePalma and Atkinson Citation2006; Braun Citation2011; Gray Citation2013; Lundin Citation2016), positioning LGBT+ subjects as a source of tension that threaten to reveal or disrupt these norms. This article not only contributes to existing discourse with an underused methodological approach, but it also examines how these tensions can be beneficial in disrupting the cisgender heteronormativity that is prevalent in most schools.

Visibility, performativity and disruption

Heteronormativity is a social construct designed to privilege and uphold cisgender heterosexuality. As Lundin (Citation2016) describes it, heterosexual teachers can talk about a partner without being held to account for talking about sexuality, whereas in the same situation, an LGBT+ teacher is at risk of being understood as talking inappropriately about sex. This dilemma places LGBT+ teachers in a double-bind, where in each situation they must decide whether to conceal their identity and uphold the systems that restrict them, or to be open and potentially experience forms of hyper-visibility or discrimination (Patai Citation1992; Pallotta-Chiarolli Citation2010; Brett Citation2022). This dilemma highlights the discursive ways in which heteronormativity operates, both powerfully and silently.

Patai (Citation1992) argues that minority groups can either remain silent and invisible, contributing to existing norms, or choosing to attract surplus visibility. Surplus visibility refers to the attention, warranted or not, that a member of a minority group attracts. This visibility can then create a shift in public perception and the individual may be perceived to accurately represent the entire minority group, providing an unjustified level of responsibility. When considering LGBT+ as the minority group, heteronormativity provides the framework that highlights the surplus visibility. As a social construct, heteronormativity is one that is continuously produced and reproduced through the consent of those upholding it. Both Butler’s (Citation2006) and Atkinson and DePalma’s (Citation2009) work highlights the ways in which norms are produced and upheld, allowing us to also conceptualise how they can therefore be disrupted and challenged.

Butler’s (Citation2006) theory of performativity offers a theoretical framework that can be used to conceptualise how norms are produced and held in place. Central to the concept of gender performativity is the notion that gender is not biologically assigned, nor is it something static, inherent, or essential, but rather it is constructed through performativity. Butler identifies gender at something that one ‘does’ rather than what one ‘is’, and this ‘doing’ is influenced by myriad factors. Butler also acknowledges that expectations of gender and sexuality are built upon the binary categories of sex.

The cultural matrix through which gender identity has become intelligible requires that certain kinds of ‘identities’ cannot ‘exist’ - that is, those in which gender does not follow from sex and those in which the practices of desire do not ‘follow’ from either sex or gender. (Butler Citation2006, 24)

This quote captures the cultural expectations that people are not only cisgender and heterosexual, but that they are expected to ‘perform’ masculinity or femininity in ‘traditional’ ways. The cultural messaging received in schools, whether formally through aspects such as dress codes or gendered lessons, or through the hidden curriculum, means that expectations of gender and sexuality are pervasive but seemingly invisible, often leading to self-policing by individuals who feel they do not fit within these binary expectations. However, those who are unable or unwilling to adhere to the ‘stylised repetition of acts’ that constitute the abiding gender order (Butler Citation2006, 162) and sexuality, threaten to disrupt the fragile norms that hold cisgender heteronormativity in place. In these moments, when the repeated acts required to constitute heteronormativity are challenged, it is possible to see how hegemony can be destabilised. Butler describes how the occasional ‘discontinuity of acts’ can reveal how fragile and socially constructed understandings of gender are, allowing for possibilities of ‘gender transformation’.

The abiding gendered self will then be shown to be structured by repeated acts that seek to approximate the ideal of a substantial ground of identity, but which, in their occasional discontinuity, reveal the temporal and contingent groundlessness of this “ground.” The possibilities of gender transformation are to be found precisely in the arbitrary relation between such acts, in the possibility of a failure to repeat, a deformity, or a parodic repetition. (Butler Citation2006, 162)

It is useful here to briefly engage with critiques of Butler’s work, particularly by transgender scholars, who argue that Butler’s concept of performativity is reductionist in its focus on language and the things that gender is not, rather than the ‘realness and inalienability of identity’ (Stryker and Whittle Citation2013, 183). Butler also recognises the limitations of their original discussion of gender performativity (Citation2024), and in revisiting their work, considers the value of identity categories in providing stability and the chance to lead a ‘liveable life’ (Butler Citation2004). Butler’s concept of performativity is employed in this article, therefore, less as a critique of how sexuality and gender are individually experienced, but as an analytical tool with which to examine how hegemonic expectations of cisgender heterosexuality are produced and enacted in schools, and how in moments of ‘occasional discontinuity’, these categories can be expanded or disrupted to ensure the inclusion of LGBT+ people.

Atkinson and DePalma (Citation2009) have explored the idea of a ‘discontinuity of acts’ in disrupting heteronormativity, highlighting the importance of ‘unintelligible genders and sexualities creating crucial moments of degrounding’ (p.21), explaining that these opportunities are crucial to disrupting the continuation of norms and ‘disorganising the consent’ that is required to keep them as the dominant narrative. In these moments it is revealed, as Mackay (Citation2024) states, that ‘gender ideology’ is all around us, creating a crucial yet brief opportunity in which to question accepted norms.

How can names, the fabric of clothes, or the porcelain of toilets possibly have a biological sex? The fact is that all children should be “gender questioning” and this is the natural state of children – it is something to be encouraged. If only adults could unlearn the lessons of gender ourselves, rather than subjecting our children to it. (Mackay Citation2024)

Atkinson and DePalma further argue that these opportunities are fleeting, where ‘sedimented meaning’ in the form of existing beliefs and understanding, can quickly reorganise the consent required for norms to continue, as explored later.

Methodology

The methodology employed in this study was designed to understand the lived experiences of LGBT+ teachers within the cisgender heteronormative structure of schools. As the types of experience the research was aiming to explore can often be transitory or short-lived, a photo elicitation method was used in an attempt to capture ‘validity, depth, richness, and new insights’ (Glaw et al. Citation2017). As Allen (Citation2011) describes it, visual methodologies have the potential to capture the embodied and material manifestations of sexuality and gender which can be difficult to articulate and uncover through more traditional methods such as written or talk-based.

This article presents a selected case study based on a larger study with LGBT+ secondary school teachers, sharing the findings of four participants: John, Charlotte, Chris, and Rohan. The participants have been chosen as the focus for this paper as their experiences reveal rich insights into both the ways that normativity is constructed, and offer powerful examples of the ways it can be challenged. They also present a variety of experiences from within the LGBT+ community (gay, lesbian, bisexual, and gender non-conforming). Although the sample discussed in this article does not include trans and non-binary teachers, the initialism ‘LGBT+’ is used throughout to recognise the challenges that non-cis-heterosexual teachers often experience in schools. The initialism is not used in an attempt to subsume or conflate lived experiences of gender, sex and sexuality under the same heading to present a uniform experience of LGBT+ people.

Participants were recruited through a combination of volunteer and snowball sampling using social media. Ethical approval for the study was granted by Nottingham Trent University’s Ethics Committee and participants gave informed consent to take part in the research, understanding they could withdraw at any time. Participants’ photos and transcripts were anonymised and shared with them for approval before being included in the findings.

Participants took photos in their schools to represent the spaces in which they felt the most and least safe or visible and shared these prior to the interview for them to be printed. Participants did not need to seek permission from their school before taking the photos to prevent the need to potentially out themselves. Photos did not contain students or signifiers that could identify the school to mitigate the need for consent. The photos were then discussed in one-to-one interviews which were recorded and fully transcribed. The transcribed interviews were then thematically coded and analysed using NVivo to identify key ideas, with heteronormativity being the most prominent theme.

From my position as a teacher, but not a teacher in the participants’ schools, I possessed elements of both insider and outsider status. Being a teacher of over 10 years helped create a mutual respect between myself and the participants. Even though I did not have a direct understanding of how their school operated, I could empathise and understand the pressures and expectations they faced as a teacher. This helped to build rapport, provide legitimacy and a greater understanding of their experiences (Adler and Adler Citation1987). With some participants there was the benefit of a shared identity, language, and experience (Asselin Citation2003), but there was also the risk of conflating experiences of a broad range of sexual and gender identities. While my experience having a marginalised sexual identity provided opportunities for empathetic understanding, as Stryker (Citation2008) argues, these experiences would be very different from those of a trans person (or even lesbian or bisexual person). She argues the importance of empathy not being used as understanding of participants’ lived experiences, where interpretability and presumptions are made in place of asking for further clarifications or justification of a viewpoint. More detail about the methodology is available in other writing (Brett Citation2021; Citation2022).

Findings

The photo elicitation method revealed the small and nuanced ways in which cisgender heteronormativity is upheld within schools. Many of the examples shared were time and contextually specific, where the photos provided invaluable windows to revisit specific moments in time. Many participants described their experience of the research as emancipatory as it allowed them to describe and give a name to an important or difficult experience for the first time. The following four accounts have been chosen as a focus as they highlight the discursive ways in which heterosexual hegemony is upheld, as well as revealing exciting examples of the ways these norms can be challenged and disrupted.

John

John was a 24-year-old, gay, Religious Education (RE) teacher who spoke with great clarity about his wish to present greater visibility for LGBT+ identities in his school, yet the difficulty he found in separating the personal and the professional. He had only been at his school for three years and in that time had inadvertently become responsible for the LGBT+ charity Stonewall School Award and felt a lot of pressure to be the ‘ambassador’ for LGBT+ inclusion within the school. He had clearly become known for this role, illustrated by a story he shared of a Sixth Form student showing round a group of potential students. After seeing him, the student had said to the group ‘that’s Mr so and so, he’s in charge of the gays and the lesbians’. John generally did not mind the surplus visibility (Patai Citation1992) his challenge to the heteronorm attracted, but at times felt compromised when having to teach LGBT+ topics in RE.

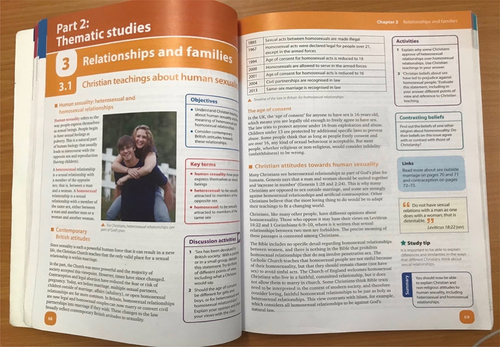

John shared a photo of a GCSE RE textbook () to illustrate how he simultaneously looked forward to, and worried about, covering the topic of ‘Christian teachings about human sexuality’ with his ‘rowdy’ year 10 groups. These lessons were an opportunity to challenge the views of his students and disorganise the consent that held heteronormativity tightly in place; however, John found it personally difficult when students made comments that were not LGBT+ inclusive. As he explained: ‘it’s hard standing there, listening to some viewpoint as if trying to be professional … and not like, take it personally’.

I remember, it was probably one of the worst lessons I’ve done, I did it with year 10 last year, and I remember the whole lesson got massively derailed because one of the kids was like ‘Oh yeah, I don’t mind gay people, just why do they keep shoving it down our throats … they try and teach kids about gay sex in primary schools’ and all of that. I kept on telling them ‘No, that’s wrong, that’s not what they’re teaching’.

This example exposes the persistent problematic views that still exist about LGBT+ people. It also demonstrates how quickly discrimination can reveal itself through a brief disruptive schism; it is hard nowadays to imagine other forms of prejudice being expressed as freely in a classroom without objection from peers. The student’s aggressive outburst placed John in a situation he then felt unequipped to deal with, where both his personal and professional identity were challenged. Many participants spoke of similar struggles navigating situations where the boundaries between personal and professional began to blur, often citing a lack of training in how to deal with the issue. John’s responsibility as a teacher was to address the topic of homosexual relationships, but he also felt a personal responsibility to address and strongly challenge the beliefs of his students. However, the comments made by students reinscribed the heteronorms of the school, making it problematic when students later asked if he were gay.

Two further heteronormative themes are evident in John’s experience. First, homosexuality is acceptable (‘I don’t mind gay people’), so long as it is not included within mainstream or public spheres, or is suitability marginal within them (‘just why do they keep shoving it down our throats’). The second theme suggests that teaching children about LGBT+ lives is inappropriate in school settings because it is deemed ‘adult content’ (‘they try and teach kids about gay sex in primary schools’). The student’s strong beliefs quickly reinscribe heterosexuality as the hierarchical norm, rendering John vulnerable and disempowered to discuss the topic further for fear of becoming the face of the student’s discrimination. As Atkinson and DePalma (Citation2009) argue, ‘recuperation by dominant discourse comes all too easily, while reinscription requires not only momentary subversion, but persistence’ (p. 23). John’s disruption to the heteronorm had not only revealed the previously hidden views of some of his students, but it also bled into the wider public sphere as a parent complained the next day.

And so, the next day, apparently a parent came … and like was saying that I … that their child’s RS [religious studies] teacher was like teaching about gay stuff.

The irate parent complaining about the teaching of ‘gay stuff’ was addressed by a member of the school leadership team who had shown the parent the textbook and lesson content, explaining the aggressive way the parent had acted when entering the school was not appropriate. After having a clearer understanding about what had happened in the lesson, the parent apologised for how they had behaved. The parent’s initial frenzied response to their child being taught about homosexuality demonstrates a hysteria that there are aspects of LGBT+ lives the parent did not want their child to know about. It also supports the view expressed by the student, that in some way pupils were being indoctrinated through this teaching (a view that would never be levied against comparable discussions of heterosexuality). Although John felt supported by the school leadership team in how they handled the parent, as Formby (Citation2013) argues, there needs to be a greater focus on the heteronormative structures that act as catalysts for these types of response, rather than dealing with individual acts, with little relationship to the processes or social structures that create them. John’s momentary subversion was not met by leaders with the necessary persistence to challenge heteronormativity, and as such, the dominant discourse quickly recovered.

Charlotte

Charlotte was a 41-year-old, lesbian, music teacher who described herself as not entirely cisgender. Charlotte felt she did not experience or perform femininity in traditional or expected ways, which examined through Butler’s later critique of gender performativity (Citation2004), highlights the stress that people who cannot, or choose not to, present gender congruence may experience. Charlotte shared many examples in her school where the ‘various degrees of stability for a liveable life’ (Butler Citation2004, 8) were absent.

Charlotte shared a photo () representing a conversation she had had with a colleague with whom she was sharing cover duties for a member of staff who had been off having a knee operation. The colleague was telling Charlotte the reason she had told the students about why the member of staff was off.

She said that she had been telling all of his students that he was off work because he was transitioning, and when he returned, he was no longer going to be called Mister Steve- [surname], but he was now going to be called Mrs Stevie- [surname]. It was a great big joke, telling all of his students that he was transitioning, and he wasn’t having the knee surgery at all, and she just thought it was hilarious and perfectly acceptable thing to joke about in a school … and I felt paralysed by that. I was furious, I was shocked, I was angry.

Charlotte said, ‘I desperately wanted to scream at her that for goodness’ sake you can’t say that, it’s not even a joke’. Not only did the colleague’s comments reinscribe cisgender norms but, more troublingly, a role model had given permission to a class of students to make fun of gender variance. Teachers are seen by students as an extension or proxy for the school itself, and so in making a joke of the issue of transition, the teacher had contributed to a school culture in which gender transitioning was not to be taken seriously, with laughter as an appropriate response. The teacher had signalled to students, as Butler (Citation2004) theorises, that those who do not fit into fixed gender binaries are unintelligible and can thus can be dehumanised. Much like John’s earlier example, the teacher’s comment demonstrates a limit to tolerance and acceptance, invalidating those who exist outside of the strict binary of male and female, reducing the idea of transgender or gender non-conforming people ‘in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one’ (Goffman Citation2009, 3).

The UK’s National LGBT Survey (Government Equalities Office Citation2018) reported that 9% of negative or LGBT-phobic incidents in schools were committed by teaching staff. Charlotte’s example provides context to what these incidents may look like. In an environment with greater visibility for trans and gender non-conformity, a comment like this may have been less impactful, or in contrast, highlighted it for its inappropriateness. However, with no counterview, incidents like this contribute to the constant maintenance (Atkinson and DePalma Citation2009) that cisgender heteronormativity requires.

Charlotte’s school appeared to be one of the least inclusive in the study, highlighted by how many stories of this nature she was able to present. She shared another picture of the Head Teacher’s office (). Charlotte took this photo to demonstrate her unease around leadership; she explained an incident with the former Head Teacher who had hastily bought a card for her on the last day of term before she got married to her wife.

And on the front of that card, that we received in that staff end of term gathering, the front of the card said, ‘congratulations on your wedding’ and the graphic at the back said ‘Mr and Mrs’ … it’s just so unbelievably thoughtless and insensitive, and just downright stupid. That’s just someone who just didn’t give a flying monkey … and because of those experiences I had with my previous Head Teacher, I am just now cautious, all the time, in any conversation with senior leadership, I’m just always cautious … and that’s not a healthy thing to be.

The incident not only reminded Charlotte of the heteronormative expectation for marriage to be between a man and a woman, but also Charlotte’s colleagues, who the Head Teacher had presented the card in front of. The incident was no doubt a careless mistake, but from the perspective of Charlotte, it was another example of heterosexual hegemony preventing her from leading a liveable life (Butler Citation2006).

Both John and Charlotte’s stories provide small insights into the repeated daily messages that are subtly communicated within schools so as to uphold cisgender and heterosexual norms. The subtext to many of these messages reveal attitudes that still exist towards LGBT+ people, that are clearly not being tackled through schools’ basic commitments to the Equality Act (Government Equalities Office Citation2010). These examples demonstrate the need for a critical awareness to be developed among all staff to identify and challenge the unhelpful or dangerous views that hold normative expectations in place. In contrast, the following two stories demonstrate ways in which critical awareness can be developed in students and colleagues to create moments of disruption and degrounding.

Chris

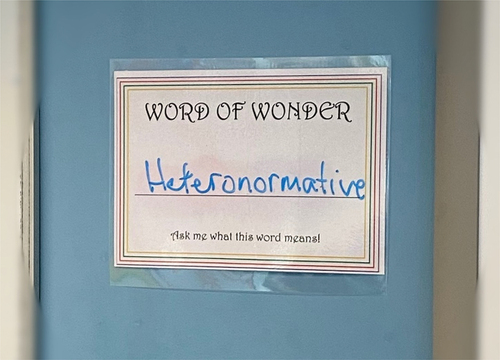

Chris was a 23-year-old, bisexual, English teacher in his first year of teaching, who described the power of naming and discussing socially constructed ideas. His school had a weekly ‘Word of Wonder’ which was displayed in classrooms as a focus for discussion ().

I think discussing heteronormativity is really interesting, because it’s such kind of almost a factual thing that everyone is assumed to be straight and the world is kind of heteronormative …

I think it really forces the kids to kind of self-reflect and reflect on their environments, and kids are so kind of malleable and easily impressionable. I think this, you know, let’s discuss this word and discuss what heteronormativity is and how, you know, presumably, how it can be combatted, I think is really, really good.

The Word of Wonder display literally invited students to ask the teacher what this word meant, creating multiple, powerful opportunities to disorganise heteronormativity’s consent. The signs facilitated a way for all members of the school to reflect on and discuss this concept, rather than leaving it up to LGBT+ teachers. The display also provided an opportunity for staff to critically reflect on the ‘consent’ they provide in upholding hegemonic norms. Chris reflected on the effectiveness of this handwritten sign, comparing it to posters from Stonewall’s well known ‘some people are gay, get over it!’ campaign. Chris suggested that posters have limited impact after a while, as they stop being seen and do not encourage discussion of the topic, supporting Ferfolja’s (Citation2007) view that without appropriate context, posters and displays can often be tokenistic. With the teacher being the one to not only write the word, but encourage conversation of it, students got to see a role model engage with the topic and provide the ‘real voices’ required to challenge heteronormative institutions and present equal citizenship (Plummer Citation2001). This approach empowered both students and teachers, and provided a moment of degrounding, in which assumptions of heteronormativity could be temporarily questioned, discussed, and challenged. Through these conversations, teachers were able to develop their students’ critical awareness, introducing the concept of a socially constructed reality, one in which they were all agents with the ability to enact change. In discussing the concept and implications of heteronormativity, as Pellegrini (Citation1992) argues, the students were then able to think outside of their previous understandings, restricted by language.

Chris described another situation, where a discontinuity of acts allowed for a positive and disruptive conversation about gender in the classroom. Chris explained how on a non-uniform day, a male student had taken the opportunity to dress in a ‘gender-fluid’ way, interrupting the repeated gendered acts the school uniform usually provided. Chris explained how when a classmate had asked the student ‘why do you wear those kinds of clothes?’, that it had opened a conversation to the class that the teacher facilitated, where they explored their understandings of gender and gendered expectations. As Atkinson and DePalma (Citation2009) argue, these moments of degrounding are crucial in disrupting the continuations of norms and disorganising the consent that is required to keep them as the dominant narrative. By facilitating the conversation that had been allowed to emerge due to a non-uniform day, the teacher had created a moment of disruption in which concepts of gender and gender performativity could be explored and challenged. However, the ‘sedimented meaning’ may have quickly reinstated the status quo once the students had left the room or were back in school uniform the next day, highlighting the importance of a persistent and whole school approach.

Like toilets, uniform offer a physical, tangible aspect of school that enforces binary ideas of gender and communicates that these are not to be mixed or transgressed. Uniform policies force both teachers and students to enact a form of gender that they be uncomfortable with, while simultaneously upholding the binary norms that may constrain them.

Rohan

Rohan was a 33-year-old, gay, Asian, Science teacher who worked in a boys’ school. Rohan acutely felt the normalised expectations of hegemonic masculinity and was able to simultaneously uphold yet subvert many of these views within his classroom to create crucial moments of degrounding. Rohan’s school was all boys for ages 11–16 (the Sixth Form was mixed), and he described the pressure on students to fit the stereotype of a ‘tough guy’. He felt the expectation of being a ‘tough guy’ affected the respect male teachers were able to receive.

Rohan had moved to his current school with the clear intention of being a visible gay, Asian role model. He recognised the importance of adhering to existing social norms to gain acceptance; this then put him in a position of authority in which to challenge and disrupt these. Rohan explained that he thought it was ‘easier’ to be a male teacher and that male teachers had immediate access to respect that female teachers did not. He also explained the immediate credibility he thought you gained as a male teacher was likely to be eroded by the more ‘stereotypically gay’ you were. This supports Connell’s (Citation2015) view that it is the embodiment and performance of masculinity that provides the immediate access to acceptance.

So, I think in general, male teachers probably have an easier time, simply because of the male privilege that we get, but I think that it does go away the more stereotypical you are, I think whether … the more you fall into the stereotype … stereotypical behaviour and presentation, the harder it is for you, I think.

The heterosexual norm that permeates most educational spaces makes all teachers appear heterosexual, unless there are obvious clues indicating that this is not the case (Reimers Citation2020). Rohan was quite traditional in his gender performativity, and as such, there were not any ‘clues’ that he was not heterosexual. Rohan was therefore able to use the acceptance of his students to make visible an embodied gay role model that challenged their stereotypical expectations; one that aligned with a body that students assumed as heterosexual. Rohan shared a picture of his classroom (), explaining it is where he felt most comfortable to be visible as a gay teacher with students. It was a space he was fully in control of due to the clear structure provided by seating plans, knowledge of the students and school systems. I asked Rohan what reactions he gets when he comes out to groups in this classroom.

Well I think what usually will happen is they … initially when whenever they find out, I think they have a bit of a shock and obviously all the stereotypes that are in their head at that time they’re kind of thinking about those, but I think the longer I teach them, the more they realise it’s just such a non-part of my overall persona, um, as in like it’s just such a non, non-issue when it comes to me being a teacher, that they then … you know, I feel like initially they might have reservations, because obviously if they have never met somebody or haven’t had somebody in their family who’s gay etc., then they are not going to, they’re not necessarily going to want to … well they just have no kind of concept of what a gay person’s like, they just have an idea, what they’ve heard and constructed through media and through other people, so when they are actually confronted with that, I think initially they might, they might have a sense of weirdness, but I think the longer I teach them, they’re just like ‘alright, this is just literally just a teacher’.

Rohan’s detailed description of coming out highlights the radical shift that took place in students’ perceptions, as their pre-conceived ideas of a gay person collided with the embodied role model stood before them. Rohan’s visibility created a transformative moment in which he simultaneously revealed and challenged the invisible heteronorms of the school. The initial revelation of Rohan’s sexuality to his students produced surplus visibility (Patai Citation1992) and, as he described it, a ‘weirdness’. Rohan coming out brought the topic of sexuality, and therefore sex, into the classroom. This created an uneasiness between the personal and professional, in which he the person had become the focus, rather than the learning that would normally be taking place.

Rohan’s description of initial ‘weirdness’ can be read as moment in which a disorganisation of consent was created (Atkinson and DePalma Citation2009). It can be further analysed through Butler’s lens of performativity to examine why the ‘sedimented meaning’ was unable to fully reorganise the consent required to uphold heteronormativity. Rohan’s repeated ‘performances’ as a gay man had gradually reshaped his students’ perceptions and understandings of sexuality, to the point where he was seen as ‘just another teacher’. However, it could be further argued that acceptance of Rohan’s sexual identity was dependent on his compliance to performing hegemonic masculinity; it is possible that Rohan’s sexuality was only intelligible to students within a cisnormative framework that expected congruent gender performativity.

Rohan described coming out in ways such as discussing his partner which, if he were heterosexual, would not be considered discussion of sexuality or sex. Patai’s (Citation1992) description of surplus visibility is of value in understanding Rohan’s experience. It suggests a marginalised person’s identity is often extrapolated from ‘part to whole’ where they are seen to represent an entire minority group. Rohan appeared to have reduced the size of this metaphorical spotlight by not only discussing his sexuality and challenging students’ misconceptions, but also ensuring it was presented as only one part of his identity. Rohan was able to present a form of powerful visibility (Brett Citation2022) where his students’ understandings of masculinity were gently challenged and expanded.

Limitations and opportunities

Due to the article length, only a small number of LGBT+ voices have been included within this paper. Naturally, these voices do not represent the entirety of the LGBT+ initialism or community, nor do they represent a broad range of intersectional identities. However, the narratives do reveal useful examples of the ways in which cisgender heteronormativity is produced, experienced, and even challenged. The findings from the research contribute to the existing literature that positions schools as sites of entrenched heteronormativity (Page and Peacock Citation2013; DePalma and Atkinson Citation2006; Gray Citation2013; Braun Citation2011). The research also offers a new perspective to the academic field about how heteronormativity can be successfully destabilised. The article further highlights the value of visual methodologies as a tool that can empower participants and allow others to see through the eyes of minority groups to develop empathy and critical awareness. Photo elicitation should not just be a research method used by academics; with the right ethical consideration and application, it is a powerful tool that school leaders can use to challenge norms and approach LGBT+ inclusion in a meaningful way. As Atkinson and DePalma Argue (Citation2009), teachers should be constantly searching for these [new] opportunities and for moments of degrounding (p. 23).

Conclusion

This article began by discussing Mackay’s (Citation2024) critique that contrary to the UK government’s claim, gender ideology is all around us, and that recent high profile transgender discourse has, for many, uncomfortably revealed gender and sexuality as social constructs. The stories of John, Charlotte, Chris and Rohan have been used to explore examples of the systems, cultures and structures that hold heteronormativity in place. LGBT+ inclusion often sits as a source of tension within schools, threatening to reveal the consent required to uphold a dominant cisgender heterosexual narrative. Through naming and examining the ways in which this hegemony is upheld, we reveal that the ‘normalcy’ these practices are couched in is often anything but normal.

If schools can be accused of ‘pandering’ to trans pupils (Swinford Citation2022) by allowing them to use a gender-neutral toilet or use their preferred pronouns, then the same level of scrutiny needs to be applied to schools that make their students use gendered toilets, wear a gendered uniform, or follow a curriculum with majority cisgender heterosexual representation. Through questioning these practices, we reveal the instability with which norms are held in place, creating vital moments of degrounding in which the consent required to uphold their dominance is disrupted (Atkinson and DePalma Citation2009). Although fleeting, these moments provide exciting and important opportunities for us to call into question the practices that produce cisgender heternormativity and expose immutable norms as both socially constructed and fragile.

Acknowledgments

A thank you goes to the participants who so generously shared their time and experiences for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data this paper is based on are accessible here: https://www.proquest.com/openview/c446d6c2b390810bff540cc8184aa131/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

References

- Adler, P. A., and P. Adler. 1987. Membership Roles in Field Research. Vol 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Allen, L. 2011. “‘Picture This’: Using Photo-Methods in Research on Sexualities and Schooling.” Qualitative Research 11 (5): 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111413224.

- Asselin, M. E. 2003. “Insider Research: Issues to Consider When Doing Qualitative Research in Your Own Setting.” Journal for Nurses in Professional Development 19 (2): 99–103.

- Atkinson, E., and R. DePalma. 2009. “Un‐Believing the Matrix: Queering Consensual Heteronormativity.” Gender and Education 21 (1): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213149.

- Braun, A. 2011 2. “‘Walking Yourself around as a Teacher’: Gender and Embodiment in Student Teachers’ Working Lives.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (2): 275–291.https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.547311.

- Brett, A. 2021. Changing the Narrative: A Photo Elicitation Study of LGBT Secondary School Teachers in England. United Kingdom: Nottingham Trent University.

- Brett, A. 2022. “Under the Spotlight: Exploring the Challenges and Opportunities of Being a Visible LGBT+ Teacher.” Sex Education 24 (1): 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2143344.

- Brett, A. 2024. “Space, Surveillance, and Stress: A Lefebvrian Analysis of Heteronormative Spatial Production in Schools, Using a Photo Elicitation Method with LGBT+ Teachers.” Sex Education 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2296473.

- Butler, J. 2004. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2006. Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2024. Who’s Afraid of Gender? Totonto, ON: Knopf.

- Connell, C. 2015. School’s Out; Gay and Lesbian Teachers in the Classroom. 1st ed. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- DePalma, R., and E. Atkinson. 2006. “The Sound of Silence: Talking about Sexual Orientation and Schooling.” Sex Education 6 (4): 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810600981848.

- Department for Education. 2019. Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. London: Department of Education.

- Department for Education. 2021. “Keeping Children Safe in Education 2022. Statutory Guidance for Schools and Colleges.” https://consult.education.gov.uk/safeguarding-in-schools-team/kcsie-proposed-revisions-2022/supporting_documents/KCSIE%202022%20for%20consultation%20110122.pdf.

- Department for Education. 2023. Gender Questioning Children: Non-Statutory Guidance for Schools and Colleges in England. London: Department for Education.

- Edwards, L. L., D. H. K. Brown, and L. Smith. 2016. “‘We are Getting There Slowly’: Lesbian Teacher Experiences in the Post-Section 28 Environment.” Sport, Education and Society 21 (3): 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.935317.

- Ferfolja, T. 2007. “Schooling Cultures: Institutionalizing Heteronormativity and Heterosexism.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 11 (2): 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110500296596.

- Formby, E. 2013. “Understanding and Responding to Homophobia and Bullying: Contrasting Staff and Young People’s Views within Community Settings in England.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 10 (4): 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0135-4.

- Glaw, X., K. Inder, A. Kable, and M. Hazelton. 2017. “Visual Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Autophotography and Photo Elicitation Applied to Mental Health Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1609406917748215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917748215.

- Goffman, E. 2009. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Government Equalities Office. 2010. Equality Act 2010: Guidance. London: Government Equalities Office.

- Government Equalities Office. 2018. “National LGBT Survey: Research Report.” London: Government Equalities Office.

- Gray, E. M. 2013. “Coming Out as a Lesbian, Gay or Bisexual Teacher: Negotiating Private and Professional Worlds.” Sex Education 13 (6): 702–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2013.807789.

- Lee, C. 2019. “Fifteen Years On: The Legacy of Section 28 for LGBT+ Teachers in English Schools.” Sex Education 19 (6): 675–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1585800.

- Leeson, L. 2023. “Rishi Sunak: A Man Is A Man and A Woman Is A Woman - That’s Just Common Sense.” The Independent, 5 October. https://www.independent.co.uk/tv/news/rishi-sunak-man-is-a-man-speech-transgender-b2424372.html.

- Lundin, M. 2016. “Homo- And Bisexual Teachers’ Ways of Relating to the Heteronorm.” International Journal of Educational Research 75 (75):67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.11.005.

- Mackay, F. 2024. “‘Gender Ideology’ Is All around Us – But It’s Not What the Tories Say It Is.” The Guardian, 19 January. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/19/gender-ideology-tories-ministers-schools-conservative.

- National Health Service. 2024. “Gender Identity - NHS Digital.” https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-collections-and-data-sets/data-sets/mental-health-services-data-set/submit-data/data-quality-of-protected-characteristics-and-other-vulnerable-groups/gender-identity.

- ONS. 2019. “What Is the Difference between Sex and Gender?” https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/whatisthedifferencebetweensexandgender.

- Page, A. D., and J. R. Peacock. 2013. “Negotiating Identities in a Heteronormative Context.” Journal of Homosexuality 60 (4). https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.724632.

- Pallotta-Chiarolli, M. 2010. Border Sexualities, Border Families in Schools. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Parveen, N. 2019. “School Defends LGBT Lessons after Religious Parents Complain.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/jan/31/school-defends-lgbt-lessons-after-religious-parents-complain.

- Patai, D. 1992. “Minority Status and the Stigma of “Surplus Visibility”.” The Education Digest 57 (5): 35–37.

- Pellegrini, A. 1992. “S (H) Ifting the Terms of hetero/sexism: Gender, Power, Homophobias.” In Homophobia: How We All Pay the Price, edited by W. J. Blumenfed, 39–56. Boston: MA, Beacon Press.

- Plummer, K. 2001. “The Square of Intimate Citizenship: Some Preliminary Proposals.” Citizenship Studies 5 (3): 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020120085225.

- Reimers, E. 2020. “Disruptions of Desexualized Heteronormativity – Queer Identification(S) as Pedagogical Resources.” Teaching Education 31 (1): 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2019.1708891.

- Stryker, S. 2008. “Transgender History, Homonormativity, and Disciplinarity.” Radical History Review, (100): 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2007-026.

- Stryker, S., and S. Whittle. 2013. The Transgender Studies Reader. New York: Routledge.

- Swinford, S. 2022. Teachers Should Not Pander to Trans Pupils, Says Suella Braverman. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/teachers-should-not-pander-to-trans-pupils-says-suella-braverman-2qfgj70rv.

- White, M. 2024. A Commentary on Department for Education Draft Guidance. https://translucent.org.uk/a-commentary-on-department-for-education-draft-guidance/.

- World Health Organisation. 2024. “Health Topics - Gender.” World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1.