ABSTRACT

The quality of sex education varies. In England from 2020, the government attempted to improve provision by making lessons a statutory requirement. We assessed implementation in 25 secondary schools in 2022–23, framed by May’s general theory of implementation. This identifies processes of sense-making, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring, influenced by an intervention’s capability, stakeholder potential (individual and collective commitment), and institutional capacity (norms, and material and cognitive resources). Interview data from staff leading relationships and sex education (RSE) were coded thematically informed by May’s concepts. Those leading implementation ‘made sense’ of statutory guidance, finding it relevant and clear. ‘Cognitive participation’ among participants was strong, promoted by individual support for RSE but undermined by social norms prioritising academic attainment, limited skills among non-specialist teachers, and lack of ‘collective commitment’ among some staff and students. ‘Collective action’ varied across schools, influenced by availability of material resources and specialist staff. Schools undertook internal the ‘reflexive monitoring’ of provision, supported by school leaders’ awareness work would be assessed by government inspectors. On its own, statutory status is likely insufficient to achieve a step-change in RSE implementation. Other forms of support may be needed including training and offering support to more specialist teachers.

Introduction

In this paper, we examine the implementation of relationships and sex education (RSE) which recently became a statutory requirement in English secondary schools. Despite a 70% reduction in under-18 conceptions in the last 20 years, the UK has the highest rate of teenage births in western Europe and teenagers are the age-group at highest risk of unplanned pregnancy (World Bank Citation2023). Age of sexual debut has been decreasing since the mid-twentieth century (Lewis et al. Citation2017), with most young people reporting non-competent first sex,Footnote1 posing a risk for adverse sexual health (Palmer et al. Citation2017). Violence in adolescent dating relationships and sexual harassment at school is reported to be widespread in England, Scotland and Wales (Ofsted Citation2021).

Evidence from UK randomised trials has suggested that good quality RSE can contribute to delayed sexual debut among girls, improved contraception and fewer teenage births (Stephenson et al. Citation2008, Citation2004; Lohan et al. Citation2022). However, research indicates that RSE provision varies in coverage and quality (Waling et al. Citation2020; Cheedalla, Moreau, and Burke Citation2020). Some form of sex education has long been compulsory in England and Wales but only regarding biological aspects such as puberty, reproduction, HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI). Schools have also been free to teach broader aspects, such as healthy relationships and consent, but parents could withdraw their children (Pilcher Citation2007). The Labour government of 1997–2010 provided non-statutory guidance on RSE and planned to make it statutory but left office before relevant legislation could be passed (Social Exclusion Unit Citation1999).

From September 2020, the Conservative government aimed to improve coverage and quality of RSE in England by making it a statutory requirement for all schools to teach relationships, sex and health education (RSHE) (Department for Education Citation2019). All secondary schools must teach about sex and relationships, and all primary schools must teach RSHE tailored to the age and maturity of students. Parents can withdraw their children from certain elements of sex (but not relationships) education, but children may opt-in against their parents’ wishes three terms before they turn 16. Schools have some flexibility in their approach, with guidance to ensure content meets the needs of pupils and local communities, including faith perspectives. All schools must have a written RSE policy about which they must consult parents. For secondary schools, the policy should define RSE, describe content, delivery, monitoring and evaluation, and parents’ right to withdraw their children. Schools must challenge sexism, misogyny, homophobia and gender stereotypes, and sexual harassment and violence. Schools must ensure RSE is appropriate for all students, including those with special educational needs and disabilities, and those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. Secondary schools are required to teach a broad curriculum including biological and social aspects, topics such as sexual abuse, harassment, female genital mutilation, coercive control and online/pornography harms, sharing and viewing indecent images of children, and communicating and seeking consent. There is no specification concerning how much lesson time should be allocated. The English national school inspectorate (Ofsted) must examine RSHE as part of its inspections.

The government offered £6 million for training and support in England (Department for Education Citation2020). Teaching materials are not prescribed but guidance provides advice on choosing these. Online training has been made available. However, as of September 2023, £3.2 million of the budget remained unspent (Long Citation2023). Studies suggest around half of teachers who teach RSE do not feel confident delivering RSE (Sex Education Forum Citation2022a).

We aimed to examine implementation of statutory RSE in English secondary schools. Studies of RSE implementation have not previously examined how a central policy directive can affect local implementation, instead examining delivery within trials of sexual health interventions (Strange et al. Citation2006; Buston et al. Citation2002) or in the absence of policy change (Rose et al. Citation2018; Hulme Chambers et al. Citation2017). Making RSE statutory and offering resources may be insufficient to ensure that it is implemented well. Implementation may be hindered by limited school capacity and resources, competing demands, limited timetable space and lack of belief in the value of the policy (Herlitz et al. Citation2020), or inconsistent staffing, poor communication, limited teacher confidence, comfort and skills in teaching sex education, and parental resistance (Buston et al. Citation2002; Strange et al. Citation2006).

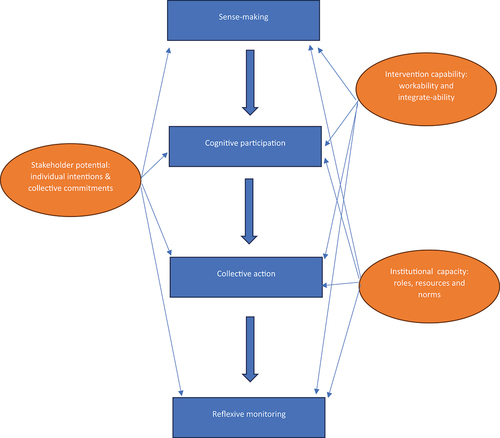

Unlike many previous analyses of RSE implementation, our research was guided by a theoretical framework. The general theory of implementation (May Citation2013) is a sociological framework for understanding generalisable social processes through which complex health interventions are enacted and the factors influencing these. It proposes that such interventions are enacted through processes of ‘sense-making’, ‘cognitive participation’, ‘collective action’ and ‘reflexive monitoring’ () with each being the necessary precursor to the next. ‘Sense-making’ involves providers coming to understand a possible intervention. ‘cognitive participation’ involves providers committing to delivery. ‘collective action’ involves collaboration to enact implementation. ‘reflexive monitoring’ involves formal/informal assessment of the success of implementation and what further actions are needed, which can inform iterations of implementation.

The general theory of implementation suggests these processes may be influenced by: intervention ‘capability’ (whether it is workable and can be integrated within a social system); local ‘capacity’ (whether material and cognitive resources, and social roles and norms are present to support implementation); and potential (whether providers hold supportive individual intentions and collective commitments to implementation).

Informed by this theory, we aimed to examine: how well school leadsFootnote2 report statutory RSE has been implemented across English secondary schools; whether processes of sense-making, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring occur; and how intervention capability and local capacity, and potential affect the extent of implementation?

Materials and methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with school staff leading RSE, RSHE or ‘personal, social, health and economic’ (PSHE) education, within which lessons RSE is often delivered, in 25 secondary schools (for students aged 11–16 years) participating in the usual-practice control arm of a trial of a multi-component, sexual-health intervention delivered over the 2022/23 and 2023/24 school years. Schools in the control arm continued with their existing plans to implement statutory RSE without additional support other than a £500 compensation for the workload arising from participation in the research. Full details of the overall study are reported elsewhere (Ponsford et al. Citation2021).

The trial aimed to recruit a representative sample of secondary schools from southern/central England in terms of school type, GCSE attainment and local Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI). Eligible schools were of any school type (including private schools) excluding pupil referral units and schools for students with special educational needs and disabilities; and with a ‘requires improvement’ or higher national school inspectorate ratings. Schools were recruited via email and phone calls with interested schools, and head-teachers signed a form giving their consent for the school to be involved. After baseline surveys with year-8 students (aged 12/13) conducted between November 2021 and March 2022, schools were randomly allocated to intervention/control arms by the LSHTM clinical trials unit (CTU), stratified by school-level GCSE attainment and local deprivation.

Interviews with PSHE or RSHE leads in control schools were conducted by telephone or online during the 2022–23 school year. These provided informed consent for interviews. Interviews followed guides featuring key topics and probes (Online supplementary materials), exploring RSE provision, informed by the School Health Research Network school health questionnaire (Murphy et al. Citation2018).

Interviews were transcribed from audio-recordings and anonymised. Each participant was allocated an identity code to protect anonymity. Transcripts were coded inductively and thematically by the first author (RP) based on and initial open and in-vivo coding, as well as deductively informed by concepts in the interview guide and the research questions. All transcripts were reviewed and five (20%) chosen randomly for double-coding by RM. There was strong inter-rater similarity. Preliminary codes were then refined through team discussion. Axial coding then identified inter-relationships between open and in vivo codes, and data were organised into higher-order and sub-themes informed by the general theory of implementation (May Citation2013). Memos explained emerging themes and interpretations, and were reviewed and revised into a final framework involving all team members (Charmaz Citation2014). This study was approved by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (ref: 26411).

Results

Schools involved were broadly representative of mainstream schools in England () although they tended to be larger that average, with higher Ofsted ratings, more girls-only schools and no boys-only schools, and fewer students entitled to free school meals or having English as an additional language.

Table 1. Comparison of study schools and English schools.

We interviewed 25 participants responsible for RSE. Six participants’ roles focused solely on RSE and other aspects of PSHE, while the remainder had additional teaching or leadership responsibilities ().

Table 2. Participants and delivery.

Most schools timetabled RSE lessons, while a few used drop-down days (when a year-group comes off normal timetable to study a topic) and/or morning registration/tutor-group time. Almost all had a fortnightly or more frequent delivery of RSHE, PSHE or the subject area within which RSE was taught for at least some year-groups. A few had more lessons for students in years 7–9 (age 11–14 years) than 10–11 (age 14–16 years). Some delivered much of their curriculum via form-tutors and some used staff with spaces in their timetables. A few used staff selected for their interest or experience. In one school, the PSHE lead taught all lessons and one school primarily used external providers. Most schools supplemented in-house delivery with provision by external specialists, such as sexual health charities or local sexual health nurses. In all but one school, teaching materials were developed by RSE leads, drawing on existing resources. A few schools adapted ready-made curricula from a single source for some year-groups. Training for staff delivering lessons was most commonly provided in-house by PSHE leads.

Below, we describe the processes of RSE implementation and factors affecting this, structured around themes aligning with the constructs of the general theory of implementation (indicated in italics). Square brackets indicate participant number.

Sense-making

The introduction of statutory RSE for secondary schools generally made sense to staff in terms of their own values, individual intentions and collective commitments towards teaching RSE. Statutory status was seen as something that ‘should have come in a long time ago’ according to one teacher whose primary role was RSHE lead [5].

In terms of intervention workability, participants generally found the Government guidance easy to understand, the content reflecting what they considered relevant for their students:

‘Looking at … what they want us to deliver, I thought “one, it was right for the right key stages and two, I actually think it’s all relevant stuff for the kids who are in front of us”’. (RSHE not primary role [3])

Some saw limitations in terms of intervention capability, of the guidance, in that requirements could have been summarised more concisely. One participant described their difficulty understanding the policy:

I think everything always when it comes to policies … , there’s just so much writing with all of these policies that what we need is the simplification and we need something that is clear and fast. And yeah, without all the explanations and I think something that is truncated a bit more. (RSHE not primary role [6])

Other material resources, sourced from reputable organisations, could facilitate sense-making. Some participants reported using guidance from other organisations with expertise in the topic to help understand the guidance:

‘The thing that helped me initially was the PSHE Association [charity] … the things that they’ve got there and the resources and things that were on there’. (RSHE not primary role [13])

As part of sense-making, most participants mapped existing provision against the guidance, which was thus used to review and augment, rather than overhaul, provision:

‘I think it was just, it was the process of actually going through and going ‘Right, okay this is what our current position is, and this is kind of matching, or this needs tweaking, or we need to add this in’. So, it kind of gave us a framework to really think about our provision. (RSHE not primary role [21])

Cognitive participation

Facilitators of staff cognitive participation

Participants demonstrated strong cognitive participation to deliver statutory RSE. Most expressed positive individual intentions to implement the new guidance, describing how they valued comprehensive RSE and the benefits it could bring to students:

‘I think it’s important for the students to have that knowledge so they can make safe and sensible choices for themselves’. (RSHE not primary role [1])

Participants suggested the guidance had been taken seriously by senior school leaders and had increased collective commitment within the school for delivery. As one participant explained:

‘It’s helped to kind of raise the profile and actually make all members of the school community realise how important it is. And that definitely helped with getting more people on board in the school community’. [21]

Some described how RSE had come to be viewed by senior leadership teams (SLT) as a subject that would now be assessed by school inspectors, with consequences for school assessment:

‘[SLT] recognise that the school can fail if we don’t do it properly. So, it’s more that they sort of recognise that the importance of it … in a strategic way, rather than … on a human level’. [1]

In many schools, participants identified a role for RSE in contributing towards promoting students’ mental wellbeing and social skills. Student needs in these areas had become more obvious as schools re-opened after the COVID-19 pandemic. This tended to increase staff’s collective commitment to RSE:

But I think obviously particularly … during and after the issue that we had with regards to kind of the Coronavirus and mental health, and I think that actually that kind of recognition of actual mental health is important, has begun to drive schools to take kind of more, a better approach towards relationships and sex education. Which I think is really, really important. [5]

Barriers to staff cognitive participation

Other factors could erode cognitive participation. For example, one participant reported that, post-pandemic, meeting academic attainment targets had been prioritised and RSHE deprioritised. This was in a context of finite school capacity and a widespread social norm among school leaders that attainment should take priority:

‘Academic subjects took precedence over RSE. And therefore, I wasn’t hugely supported last year. But that wasn’t anybody’s fault, it was just there wasn’t time’. [6]

A few participants reported that a social norm of viewing RSE as a ‘lesser’ subject persisted among some colleagues, reducing their potential for implementing RSE:

‘I think we’ve still got a slight battle with some fellow curricular leaders in getting them to see it as, how important it actually is … We’re winning, but we’ve still got a few minds to kind of take on that route’ (RSHE not primary role [11])

Participants reported that such norms were sometimes apparent among staff selected to teach RSE alongside their regular teaching roles but lacking the individual intentions to commit to doing so. One lead whose school was asking teachers with gaps in their timetable to deliver RSE, described the following scenario.

‘[There could be] an English teacher, who is really, really passionate about you know doing their best on this and then there might be a History teacher, who does not care, whose priority is delivering the history’. (RSHE primary role [12])

Teachers whose main subject was not RSE sometimes prioritised their own subject because this gained them recognition and career progression. The potential of non-specialist teachers could also be undermined if they were uncomfortable with the subject matter or lacked the cognitive resources to teach it:

Now and again, you get a member of staff who says, ‘I’m not trained in this’. And I fully understand, because you know it’s hard, if you’re a 21-year-old teacher just starting in the profession and you’re teaching sex ed to a bunch of year 11s. You are not trained for that, you’re just not. (RSHE not primary role [24])

Topics such as pornography, sexual violence and consent were seen as more complex to teach than topics such as contraception and STIs. Hence, the teaching of these topics was associated with the least cognitive participation among less-experienced staff.

Staff training could overcome some of these barriers, but schools often struggled to deliver this because of lack of time and competing priorities. Teachers sometimes prioritised continuing professional development (CPD) in their main subject areas:

I suppose where it becomes more problematic is that kind of, looking at the CPD sort of time budget, like how much time can I have with my 40 tutors, to train them. So they [the school] are a bit more training-focused on teaching and learning in general subject areas, rather than this area. (RSHE not primary role [15])

Student cognitive participation

Participants generally reported strong student engagement in RSE lessons. Some identified a misalignment between, on the one hand, teaching topics such as consent, sexual harassment and gender stereotypes and, on the other, the collective commitments of some male students’ hostile to some of the inclusivity and liberal values within RSE:

It’s been more than a handful [of boys] who have sort of said, [sighs] you know ‘It’s all diversity, it’s all inclusivity, it’s all feminism, it’s all anti this, anti that’. And I just, you just wonder how much um, I imagine the students most likely to complain about having to do more of this, are probably the ones that might have some interesting opinions that might need challenging. But I do think there is a balance. Even if you absolutely need to promote and challenge from one side, you know that this is by no stretch all boys. And it’s quite important to try and strike that balance I think. (RSHE not primary role [20])

While this teacher recognised the need to challenge such views, they also recognised the need to ‘strike a balance’ so that ‘all boys’ were not positioned as problematic and potentially alienated by the teaching on such topics. Some teachers described how such views reflected misogyny emerging among some young boys, which schools were struggling to counter:

‘What we are trying to tackle is, there is, I think within schools there is a kind of growing sort of … all of this kind of misogyny that’s kind of coming out in a way that possibly it hasn’t done for a few years really. We have kind of gone backwards a little bit I think. So it’s about, it’s trying to tackle this culture of rape jokes and those sorts of things, which I think occur in every school now … but obviously wherever young people are, which is in schools and we need to take it very seriously’. [1]

Teachers saw RSE as a way to challenge such misogyny, which appeared to increase their cognitive participation for implementation.

Collective action

Internal facilitators

In all schools, key staff were in place whose social role was to co-ordinate collective action to implement statutory RSE. However, the time and status afforded to these roles varied, with only six leads having this as their main responsibility (). These leads usually worked with a group of teachers whose social roles involved delivering RSE lessons in addition to their other teaching.

How statutory RSE delivery was organised depended on available material and cognitive resources. What resources (such as timetabled hours, staff training etc.) were deployed depended on wider school social norms about priorities, what other demands schools faced, and the individual intentions and collective commitments of school leaders. Where these sources of potential were strong, this could increase allocation of resources, usually in the form of increased teaching time. One participant described how the new statutory guidance functioned as a ‘bargaining tool’ to get their head-teacher and school governors to support implementing timetabled RSE lessons [3], an example of the new policy exhibiting capability in supporting implementation. However, this was not the case for all participants, some of whom wished the guidance was more prescriptive about lesson time so they could leverage the necessary school resources:

‘I just feel like the word “guidance” is a little bit weak… I feel like, my battle last year and the last couple of years is actually getting the time on the curriculum to actually get what is needed to be done. They’ve given us this kind of guidance on what needs to be done. However, depending on your head-teacher and how your school runs, is whether or not you are going to be given time to implement all of that. So, I’d like to see more kind of, like a bit more of a rigid approach to, every year-group should be having this amount of hours a week, do you know what I mean?’ (RSHE primary role [7])

Non-specialist teachers lacking the potential and/or cognitive resources to teach RSE well were described as being one of ‘the biggest problems’ that those leading RSE faced [12]. However, in schools which used form-tutors to deliver RSE, these staff-members could play an important social role because of their knowledge of and commitment to their students.

While resources such as time and budget for training were limited, many participants described informal training or other actions to support RSE teaching. These staff briefings; shadowing the work of more experienced teachers; and ad hoc conversations [6]. School leads led development of material resources to support colleagues. Participants described this as a way of reducing the burden on hard-pressed colleagues and enhancing the consistency and quality of teaching. Some school leads provided lesson plans and slides, which were sufficient to allow non-specialists to deliver an adequate lesson and helped make colleagues feel ‘very secure’ according to teachers whose primary roles were not those of the RSHE lead [8,10].

External resources

Most leads drew on various external material resources to construct lessons aligning with the new guidance, often tailoring them to local needs. While participants reported the availability of resources had increased since the introduction of the new guidance, some struggled with the time and skill required to search for and assess the quality of these. Leads generally favoured materials created or accredited by what they considered reputable organisations (such as the PSHE Association or local authorities). This reduced the time that would have been needed to create bespoke materials:

But what I do like about the resources like the [local authority] and all of them actually, they always say”, Fulfils the statutory requirements”. So that makes it easy for me, to go ‘Oh, I don’t have to delve too deep, because it’s there, it’s proven, someone more academic than me has put the detail in it’. [24]

External providers were used by some schools as additional capacity, particularly to address topics, such as pornography and sexual violence, which participants perceived to be challenging and often beyond the cognitive resources possessed by non-specialist teachers:

So, you can do it, if you’re careful in the way you approach it. I am not, for example, going to have teachers teaching porn, you know pornography. I think that is too much for an unspecialised teacher to handle. So, we’ve got external speakers who are experienced in what they do. [8]

External experts were seen as particularly appropriate for addressing the ‘growing misogyny’ discussed above. Some leads used targeted interventions to address this concern:

‘So, we’ve identified a group of young men in year 10 and young men in year 11 … And they’re still being really overtly sexist, misogynistic and threatening towards young women. So, we’ve been working with, the charity, to basically to pull together a bit of a programme of intervention, where they look at toxic masculinity and what it means to be a successful man and all of those kind of things’. [10]

External experts were seen by some participants to possess the cognitive resources to be more engaging and credible to students than teachers.

Few schools consulted actively with parents, with most providing information on their new RSE policy and plans via their usual communication channels. Participants reported that communications had been limited by school staffing capacity and low parent/carer turnout at events. Some leads were keen to develop parent engagement further, seeing this as a way to build support for RSE and encourage conversations at home.

Reflexive monitoring

As part of their RSE policy, schools must specify how provision will be monitored and evaluated. Participants were acutely aware that their provision and how it was reviewed could be assessed by the national school inspectorate (Ofsted). In some cases, school leads said that this had led to increased internal reflexive monitoring by senior leaders to ensure that their statutory duty ‘was being done’ as described by one teacher whose primary role was not RSHE [15].

Beyond this, given their specific social roles within their schools and individual intentions to deliver good RSE, most leads were pursuing various forms of reflexive monitoring. This often involved seeking student or teacher feedback about student engagement and any challenges to delivery. While some schools surveyed students, feedback was more usually gathered through student councils, student feedback sessions and short evaluations at the end of RSE lessons. One participant described monitoring the impact of their RSHE on behaviour in school via their safeguarding system:

The main way that we’ve decided to try and track that is through the number of incidents that are in specific categories. Because our feeling is, you know, if the education is having an impact, then their behaviour around that thing will change. So, we would use kind of our safeguarding tracking system to measure that. [10]

Participants generally demonstrated positive individual intentions towards student voice and were willing to listen and respond to student feedback. One participant described how they had made efforts to improve the inclusivity of teaching materials following a student survey:

The pupils who did respond to the surveys … were quite negative about what they had been taught before in some of the topics that they’d covered, and they hadn’t been given enough information. There wasn’t enough diversity in the curriculum. We had some of our LGBTQ sort of pupils who were like ‘Well, we don’t really look at sort of, we just look at heterosexual sex, do you know what I mean?’ … So that is something that we did quite a bit of work on. (RSHE primary role [7])

Another described increasing provision for post-16 students based on feedback regarding learning gaps due to pandemic closures.

Actually, the reason we’ve got two lessons for our year 12s and 13s, our post 16s this year, is because they said ‘Actually, do you know what? Due to COVID, we’ve missed out, we want more of that education’. So, we’ve actually listened to that and we’ve amended the planning, we’ve amended the timetable and they now have their additional lessons to catch up on what they originally had missed. (RSHE not primary role [16])

In some schools, student feedback had led them to make more concerted efforts within RSE to tackle sexual harassment and misogyny. Furthermore, as indicated above, some leads reflected on how they could modify provision (including through the use of external providers) to better address these challenging issues.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

RSE implementation varied across schools even after being made statutory. While most schools timetabled lessons, many used form-tutors or teachers selected based on gaps in their timetable. Training and support were mostly in-house and informal. This resonates with a 2021 poll of English young people aged 16–17 years which found around one third reported that their RSE had been good/very good, with lower ratings among girls (Sex Education Forum Citation2022b).

May’s general theory of implementation was useful for understanding the processes by which schools implemented statutory RSE and factors influencing implementation (Herlitz et al. Citation2020). In terms of sense-making, the new guidance appeared coherent, and its introduction was generally something they could support. It was regarded as having the capability to be workable and be integrated within different models of delivery.

In addition to RSE leads being obliged to commit to RSE delivery as part of their social role, their cognitive participation was bolstered by their own potential in the form of individual intentions about delivering comprehensive RSE, as well as by the collective commitment of their colleagues (including senior leaders). The latter was strengthened by Ofsted incorporating how schools implemented the guidance into its assessments. Cognitive participation was undermined where there were norms about the primacy of academic attainment over RSE and where school capacity and material resources were stretched post-pandemic. There was limited individual intention, collective commitment and in some cases cognitive resources (such as confidence and skill) for delivery among some non-specialist staff, which could undermine cognitive participation. Among some boys, cognitive participation was undermined by lack of collective commitment to some of the inclusive and liberal values typical of RSE, a finding of some previous studies of adolescent gender-based-violence prevention (Fox, Hale, and Gadd Citation2014).

In terms of collective action, RSE leads played a critical social role in driving the implementation of the statutory guidance. Collective action to implement RSE varied across schools however. Some schools could mobilise additional material resources and social roles in the form of training and external specialist providers to support RSE implementation, helped by increased collective commitment among school leaders following the introduction of the guidance. In other schools, RSE leads struggled to get what they felt was the necessary support and these participants often reported that clearer guidance about how much RSE should be timetabled would have been useful. Having a team of specialist or trained teachers who had volunteered to teach RSE in timetabled lessons was often cited as the ideal model of delivery. However, in schools which used form-tutors, these could be seen as having strong individual potential, and cognitive resources in the form of long-term knowledge of and commitment to their students, which made them well placed to contribute to collective action to deliver RSE.

In terms of reflexive monitoring, schools were aware that RSE would be assessed by Ofsted, which meant that internal monitoring of the subject had increased to ensure requirements were being met. RSE leads sought and valued student feedback and were concerned to improve provision for students. They engaged in a range of data-gathering and appraisal activities. Many were particularly focused on engaging boys and using RSE to challenge misogyny in schools. The latter has been widely discussed in the literature (Ruane-McAteer et al. Citation2020; Flood Citation2011; Jewkes, Flood, and Lang Citation2015). It may be that many girls are dissatisfied that RSE is insufficiently comprehensive while some boys find RSE alienating. Given evidence of widespread sexual harassment and misogyny in schools (NASUWT Citation2022), schools have been guided to address this not only though RSE but via whole-school actions (Ofsted Citation2021).

Limitations

All schools had signed up to take part in a trial of an RSE intervention, which could indicate that they had a particular commitment to RSE and/or they recognised that their current provision was insufficient. Interviewees could not always provide a comprehensive description of RSE provision in terms of each lesson for each year-group, but could give a clear overview of the processes involved and the factors that affected these. Our research examined provision during the 2022–3 school year; qualitative longitudinal research might provide a fuller description of intervention processes over a longer time period. Although the wider study included interviews with students, this analysis drew on interviews with staff only, so our findings about student processes are speculative and will be examined in subsequent analyses. Our data supported the processes and influential factors described in the general theory of implementation, but our qualitative analyses were not designed to test which constructs were most critical to implementation.

Implications for policy and practice

This analysis illustrates the value of applying a sociological lens to understanding the enactment of complex interventions such as RSE as social processes, and how this involves the interaction between individual agency and broader institutional and policy structures. Our findings suggest that simply making RSE a statutory requirement was insufficient to achieve comprehensive and specialist-delivered provision, despite this being accompanied by additional funding (albeit not fully spent) and training material. Our findings contrast with studies of the implementation of England’s 1999 Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (Social Exclusion Unit Citation1999). This was well implemented and achieved significant reductions in the rate of teenage pregnancy. This was attributed to the intensive support that was put in place, such as the provision of ring-fenced funding to localities, the setting up of local Teenage Pregnancy Partnership Boards to enable local joined-up action, the employment of local coordination staff to drive change, and the entral monitoring of performance targets (Hadley, Ingham, and Chandra-Mouli Citation2016). RSE may not require a precisely similar set of arrangements but other additional support is likely essential. This might include initial teacher training to produce more specialist RSE teachers; clearer guidance on the amount of timetabled lessons that RSE requires; quality assurance standards for external providers of RSE; and ring-fenced funding for each school for staff training and external providers where necessary for some topics.

While RSE should be provided in all schools because students have a right to learn about sexual health and healthy relationships, there is a need to develop a stronger evidence base for which approaches to RSE are most effective. We suggest that future evaluations should assess whether interventions promote the sexual competence and wellbeing of all young people (Palmer et al. Citation2017; Mitchell et al. Citation2021) rather than merely preventing specific outcomes, such as unplanned pregnancies and STIs, which even the best forms of RSE may contribute to but are unlikely to achieve by themselves (Walsh et al. Citation2015; DiCenso et al. Citation2002; Oringanje, Meremikwu, and Eko Citation2009; Shepherd et al. Citation2010; Rodriguez-Castro Citation2021; Vaina and Perdikaris Citation2022; Goldfarb and Lieberman Citation2021; Lohan and Lopez Gomez Citation2023).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff interviewed for sharing their views and sparing their time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Competent first sex has been defined as the use of contraception, autonomy of decision making, judging the timing to be right, and partners’ equal willingness (Palmer et al. Citation2017).

2. A school lead is a person responsible for leading RSE in a school.

References

- Buston, K., D. Wight, G. Hart, and S. Scott. 2002. “Implementation of a Teacher-Delivered Sex Education Programme: Obstacles and Facilitating Factors.” Health Education Research 17 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1093/her/17.1.59

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE.

- Cheedalla, A., C. Moreau, and A. E. Burke. 2020. “Sex Education and Contraceptive Use of Adolescent and Young Adult Females in the United States: An Analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth 2011–2017.” Contraception 20 (2): 100048.

- Department for Education. 2019. Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education: Statutory Guidance on Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2020. Plan Your Relationships, Sex and Health Curriculum. London: Department for Education.

- DiCenso, A., G. Guyatt, A. Willan, and L. Griffith. 2002. “Interventions to Reduce Unintended Pregnancies Among Adolescents: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials.” The British Medical Journal 324: 1426–1434.

- Flood, M. 2011. “Involving Men in Efforts to End Violence Against Women.” Men and Masculinities 14 (3): 358–377.

- Fox, C., L. R. Hale, and D. Gadd. 2014. “Domestic Abuse Prevention Education: Listening to the Views of Young People.” Sex Education 14 (1): 28–41.

- Goldfarb, E. S., and L. D. Lieberman. 2021. “Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education.” Journal of Adolescent Health 68 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036

- Hadley, A., R. Ingham, and V. Chandra-Mouli. 2016. “Implementing the United Kingdom’s ten-Year Teenage Pregnancy Strategy for England (1999-2010): How Was This Done and What Did it Achieve?” Reproductive Health 13 (1): 139.

- Herlitz, L., H. MacIntyre, T. Osborn, and C. Bonell. 2020. “The Sustainability of Public Health Interventions in Schools: A Systematic Review.” Implementation Science 15 (1): 4.

- Hulme Chambers, A., J. Tomnay, S. Clune, and S. Roberts. 2017. “Sexuality Education Delivery in Australian Regional Secondary Schools: A Qualitative Case Study.” Health Education Journal 76 (4): 467–478.

- Jewkes, R., M. Flood, and J. Lang. 2015. “From Work with Men and Boys to Changes of Social Norms and Reduction of Inequities in Gender Relations: A Conceptual Shift in Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls.” Lancet 385 (9977): 1580–1589.

- Lewis, R., C. Tanton, C. H. Mercer, K. R. Mitchell, M. Palmer, W. Macdowall, and K. Wellings. 2017. “Heterosexual Practices Among Young People in Britain: Evidence from Three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles.” Journal of Adolescent Health 61 (6): 694–702.

- Lohan, M., A. Brennan-Wilson, R. Hunter, A. Gabrio, L. McDaid, H. Young, R. French, et al. 2022. “Effects of Gender-Transformative Relationships and Sexuality Education to Reduce Adolescent Pregnancy (The JACK Trial): A Cluster-Randomised Trial.” Lancet Public Health March 7 (7): e626–e637.

- Lohan, M., and A. Lopez Gomez. 2023. Comprehensive Sex Education an Overview of the International Systematic Review Evidence. Paris: UNESCO Digital Library.

- Long, R. 2023. Relationships and Sex Education in Schools (England). London: House of Commons Library.

- May, C. 2013. “Towards a General Theory of Implementation.” Implementation Science 8: 18.

- Mitchell, K. R., R. Lewis, L. F. O’Sullivan, and J. D. Fortenberry. 2021. “What Is Sexual Wellbeing and Why Does it Matter for Public Health?” The Lancet Public Health 6 (8): E608–E613.

- Murphy, S., H. Littlecott, G. Hewitt, S. MacDonald, J. Roberts, J. Bishop, C. Roberts, et al. 2018. “A Transdisciplinary Complex Adaptive Systems (T-CAS) Approach to Developing a National School-Based Culture of Prevention for Health Improvement: The School Health Research Network (SHRN) in Wales.” Prevention Science. doi:10.1007/s11121-018-0969-3

- NASUWT. 2022. Poll on Sexism and Sexual Harassment in Schools. London: NASUWT.

- Ofsted. 2021. Review of Sexual Abuse in Schools and Colleges. London: Ofsted.

- Oringanje, C., M. M. Meremikwu, and H. Eko. 2009. “Interventions for Preventing Unintended Pregnancies Among Adolescents.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD005215.

- Palmer, M. J., L. Clarke, G. B. Ploubidis, H. Mercer, L. J. Gibson, A. M. Johnson, A. J. Copas, and K. Wellings. 2017. “Is “Sexual competence” at First Heterosexual Intercourse Associated with Subsequent Sexual Health Status?” Journal of Sex Research 54: 91–104.

- Pilcher, J. 2007. “School Sex Education: Policy and Practice in England 1870 to 2000.” Sex Education 5 (2): 153–170.

- Ponsford, R., R. Meiksin, E. Allen, G. J. Melendez-Torres, G. J. Morris, C. Mercer, R. Campbell, et al. 2021. “The Positive Choices Trial: Study Protocol for a Phase-III RCT Trial of a Whole-School Social-Marketing Intervention to Promote Sexual Health and Reduce Health Inequalities.” Trials 22 (1): 818.

- Rodriguez-Castro, Y. 2021. “Sex Education in the Spotlight: What Is Working? Systematic Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2555.

- Rose, I. D., L. Boyce, C. Crittenden Murray, C. A. Lesesne, L. E. Szucs, C. N. Rasberry, T. Parker, and G. Roberts. 2018. “Key Factors Influencing Comfort in Delivering and Receiving Sexual Health Education: Middle School Student and Teacher Perspectives.” American Journal of Sex Education 14 (4): 466–489.

- Ruane-McAteer, E., K. Gillespie, A. Amin, A. Aventin, M. Robinson, J. Hanratty, R. Khosla, and M. Lohan. 2020. “Gender-Transformative Programming with Men and Boys to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies.” BMJ Global Health 5 (10): e002997.

- Sex Education Forum. 2022a. Relationships and Sex Education: The Evidence. London: Sex Education Forum.

- Sex Education Forum. 2022b. Young People’s RSE Poll 2021. London: Sex Education Forum.

- Shepherd, J., J. Kavanagh, J. Picot, K. Cooper, A. Harden, E. Barnett-Page, J. Jones, et al. 2010. “The Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Behavioural Interventions for the Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Young People Aged 13 to 19: A Systematic Review and Economic Evaluation.” Health Technol Assess Monographs 14 (7): 1–206.

- Social Exclusion Unit. 1999. Teenage Pregnancy. London: Cabinet Office.

- Stephenson, J. M., V. Strange, S. Forrest, A. Oakley, A. Copas, E. Allen, A. Babiker, et al. 2004. “Pupil-Led Sex Education in England (RIPPLE Study): Cluster-Randomised Intervention Trial.” Lancet 364 (9431): 338–346.

- Stephenson, J., V. Strange, E. Allen, A. Copas, A. Johnson, C. Bonell, A. Babiker, A. Oakley, and RIPPLE Study Team. 2008. “The Long-Term Effects of a Peer-Led Sex Education Programme (RIPPLE): A Cluster Randomised Trial in Schools in England.” PLOS Medicine 5 (11): e224.

- Strange, V., E. Allen, A. Oakley, J. Stephenson, C. Bonell, and A. Johnson. 2006. “Integrating Process with Outcome Data in a Randomised Controlled Trial of Sex Education.” Evaluation 12 (3): 330–353.

- Vaina, A., and P. Perdikaris. 2022. “School-Based Sex Education Among Adolescents Worldwide: Interventions for the Prevention of STIs and Unintended Pregnancies.” British Journal of Child Health 3: 229–242.

- Waling, A., R. Bellamy, P. Ezer, L. Kerr, J. Lucke, and C. Fisher. 2020. “‘It’s Kinda Bad, honestly’: Australian students’ Experiences of Relationships and Sexuality Education.” Health Education Research 35 (6): 538–552.

- Walsh, K., K. Zwi, S. Woolfenden, and A. Shlonsky. 2015. “School‐Based Education Programmes for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004380.pub3

- World Bank. 2023. Adolescent Fertility Rate (Births per 1,000 Women Ages 15-19). Washington, DC: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT